Introduction

The success of orthopaedic surgery is a unique testament to the body’s innate capacity for biological repair. Unlike many surgical disciplines, a successful outcome is not solely defined by the technical precision of the intervention but is ultimately determined by the patient’s physiological ability to achieve fracture union, secure implant osseointegration, and mount an effective immune defence against infection. This process demands a well-oxygenated, metabolically sound, and immunologically competent host environment [

1,

2].

Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM), anemia, and hepatic dysfunction are established independent risk factors that erode this biological foundation [

3,

4]. Concurrently, cigarette smoking remains a extensive global health epidemic and a potent modifiable risk factor for surgical complications [

5]. Its pathophysiological insults—systemic vasoconstriction, tissue hypoxia, carbon monoxide-mediated impairment of oxygen carriage, increased platelet aggregability, and direct suppression of immune cell function—directly sabotage the very processes upon which orthopaedic surgery relies [

6,

7].

While the independent risks of smoking and comorbidity are well-documented, their synergistic effect in the context of orthopaedic surgery remains underexplored and poorly quantified. This gap is critical; the combination may not be additive but multiplicative, creating a distinct high-risk phenotype vulnerable to catastrophic orthopaedic-specific complications like non-union, periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), and early implant failure. Current preoperative risk stratification often evaluates these factors in isolation, potentially underestimating the true risk for a significant patient population.

This large, five-year retrospective cohort analysis aims to definitively characterise this synergy. We hypothesise that active smoking interacts synergistically with a spectrum of comorbidities to significantly worsen preoperative physiological readiness, intraoperative stability, and, most importantly, postoperative orthopaedic-specific outcomes. By analysing over 3,000 procedures, we provide a comprehensive quantification of this risk and propose a paradigm shift towards integrated, comorbidity-specific perioperative optimisation pathways. With an estimated 1.1 billion smokers worldwide and the rising prevalence of comorbidities like diabetes and obesity, quantifying this synergistic risk is a pressing public health priority with implications for global surgical safety.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all patients undergoing orthopaedic surgical procedures at a single high-volume tertiary academic center between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2024. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board with a waiver for informed consent. A total of 3,123 unique surgical procedures were identified from the hospital’s medical record system. Sub-cohorts were defined based on the presence of specific comorbidities, confirmed through preoperative history, medication lists, and laboratory values.

Patient Stratification and Variables

Within each comorbidity cohort, patients were stratified by smoking status:

Active Smoker: Any current tobacco use within 6 months of surgery.

Former Smoker: A history of smoking but abstinence for >1 year.

Non-Smoker: No history of tobacco use.

Comorbidity Definitions Were Rigorously Applied

Diabetes Mellitus (DM): n=365; documented diagnosis or use of hypoglycaemic agents.

Anaemia: n=374; Hb <12 g/dL in women, <13 g/dL in men.

Hepatic Dysfunction: n=238; documented diagnosis of hepatitis, cirrhosis, or steatosis; or ALT/AST >1.5x upper limit of normal.

Chronic Venous Disease (CVD): n=592; documented chronic venous insufficiency, varicose veins, or history of venous ulceration.

COPD: n=54; documented diagnosis.

History of TB: n=22; documented history of treated tuberculosis.

Orthopaedic Surgical Procedures

The study encompassed procedures chosen for their specific dependence on biological healing:

Trauma and Fracture Fixation: Intramedullary nailing, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of fractures (e.g., proximal femur, tibia).

Arthroplasty: Primary total hip, knee, and shoulder arthroplasty.

Spinal Surgery: Instrumented fusion.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes were assessed across three domains:

Preoperative Readiness: Hb, platelet count, INR, albumin, CRP, ASA score.

Intraoperative Outcomes: Estimated blood loss, transfusion requirement, and a composite “hostile field” outcome (occurrence of ≥2: EBL >95th percentile, intraop transfusion, or surgeon note of “friable tissues” or “poor bone quality”).

Postoperative Orthopaedic-Specific Outcomes (Primary): Non-union (lack of radiographic bridging at 6 months), PJI (MSIS criteria), implant failure (aseptic loosening/mechanical failure), reoperation/revision surgery, and 30-day mortality.

The composite ‘hostile field’ outcome was defined as the occurrence of two or more of the following: estimated blood loss (EBL) greater than the 95th percentile for the procedure type, requirement for intraoperative blood transfusion, or a qualitative surgeon note of ‘friable tissues’ or ‘poor bone quality’ in the operative report.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test; continuous variables with t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CIs, adjusting for age, sex, and ASA class. Formal tests for interaction between smoking and each comorbidity were performed. Synergy was confirmed using the Relative Excess Risk due to Interaction (RERI) and the Attributable Proportion (AP) on an additive scale, and a multiplicative interaction term in regression models. A significance level of p<0·05 was used. Analyses were performed using R v.4.2.0.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations inherent to its retrospective, single-center design. While we adjusted for key confounders including age, sex, and ASA class, the potential for unmeasured confounding (e.g., socioeconomic status, nutritional status, level of glycemic control beyond a binary DM diagnosis) persists. The use of self-reported smoking status is susceptible to misclassification bias, likely leading to an underestimation of the true effect size. Furthermore, the generalisability of our findings may be limited by the single-center setting. However, the large, consecutive cohort, the use of rigorous, objective definitions for comorbidities and outcomes, and the application of formal tests for interaction strengthen our conclusions. These findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and validated in a future multi-center, prospective cohort study.

Results

Master Cohort Overview

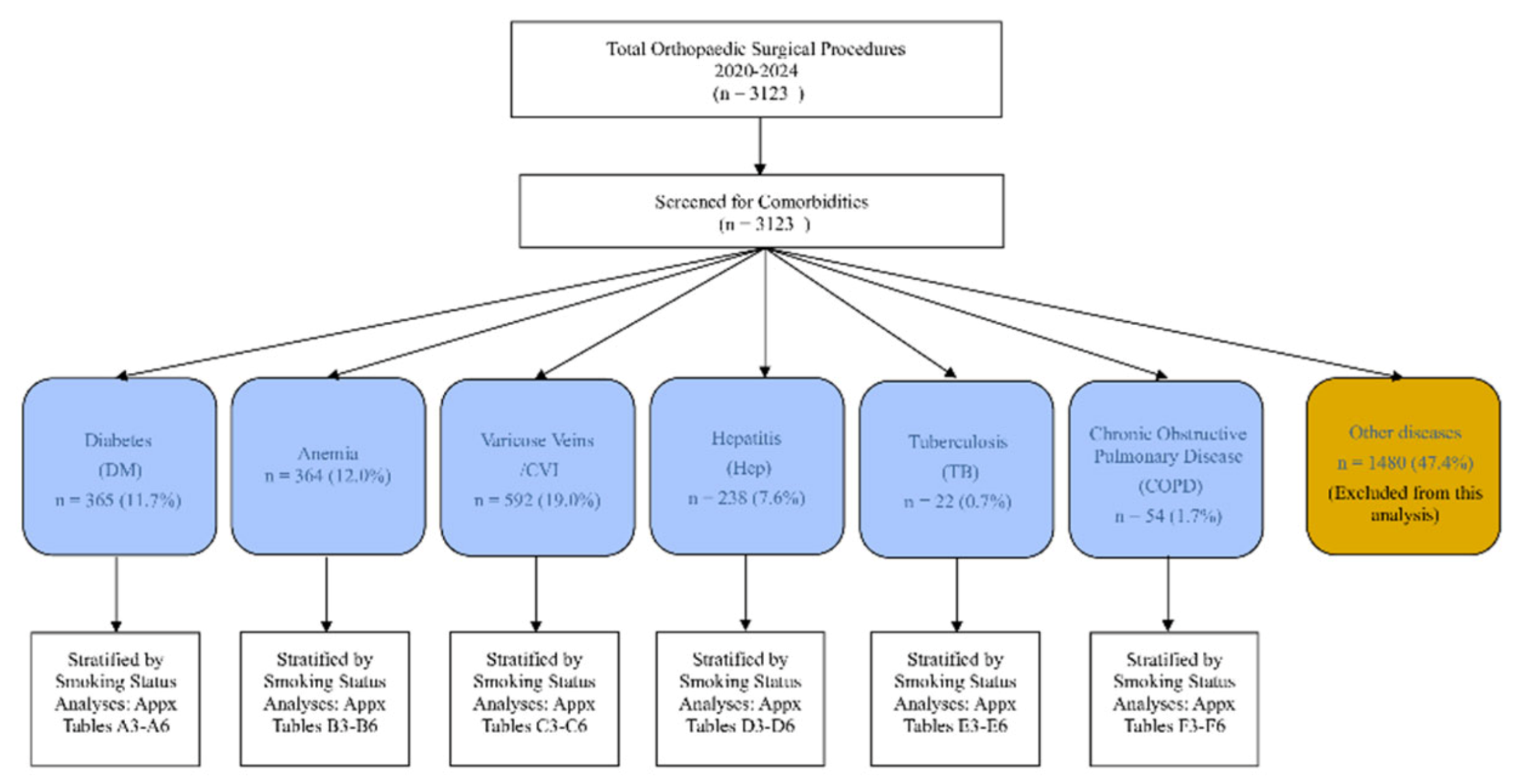

The total population comprised 3,123 patients. Active smokers were consistently younger across all comorbidity groups but presented with significantly worse preoperative physiological markers (

Table 1). A consort diagram of patient selection is shown in

Figure 1. Cohorts for COPD and history of tuberculosis were examined but were too small for modelled analysis and are described descriptively in the supplement.

Synergistic Impact on Preoperative Physiology

The combination of smoking and comorbidity resulted in a significantly higher burden of physiological frailty. In diabetics, smokers had higher rates of thrombocytopenia (22·4% vs. 9·1%, p=0·02) and elevated CRP (30·6% vs. 14·9%, p=0·01). In patients with hepatic dysfunction, smokers had more profound coagulopathy (INR >1·2: 58·3% vs. 40·9%, p=0·02).

Intraoperative Challenges: The “Hostile Field”

Hemodynamic instability was markedly higher in smokers across all major cohorts (DM: 52·6% vs. 31·1%; aOR 2·4, 1·3–4·5). Surgeons qualitatively reported a “hostile surgical field” in smokers, characterised by friable tissues, persistent oozing, and poor-quality bone.

Postoperative Orthopaedic-Specific Outcomes

The most striking findings were the dramatically increased rates of orthopaedic-specific complications (

Table 2). Formal tests for interaction between smoking status and comorbidity were statistically significant (p<0·05) for all primary outcomes in the DM, Anemia, and Hepatic cohorts, confirming a synergistic effect.

Analysis of biological interaction confirmed a significant synergistic effect. For non-union in diabetics, the Relative Excess Risk due to Interaction (RERI) was 4·9 (95% CI 1·1–10·2) and the Attributable Proportion (AP) was 0·67 (95% CI 0·2–0·9), indicating that 67% of the risk in exposed individuals was due to the interaction itself.

Trends in Smaller Cohorts (Descriptive Analysis)

Trends in the smaller COPD and TB cohorts, while not statistically powerful, aligned with the overall findings of worse outcomes in active smokers (see Supplementary Appendix). Former smokers consistently demonstrated outcomes that were intermediate between active and non-smokers.

Discussion

This study provides definitive, quantified evidence that active smoking acts as a powerful effect modifier, engaging in a synergistic relationship with common comorbidities to create a distinct high-risk phenotype in orthopaedic surgery. The peril is not merely additive; it is multiplicative, dramatically increasing the risk of catastrophic orthopaedic-specific complications.

Within a diabetic surgical cohort, smoking status delineates two distinct patient profiles: a younger, trauma-prone demographic and an older group with greater cardiovascular comorbidity. Active smoking acts synergistically with diabetes, drastically compounding the risk of catastrophic perioperative outcomes, prosthetic joint infection, and orthopaedic-specific failures. These findings mandate integrated prehabilitation pathways that enforce smoking cessation and multi-system optimization as essential, non-negotiable prerequisites for surgery in this high-risk population.

Within the anemia surgical cohort, active smokers presenting for orthopedic surgery represent a distinct demographic—younger, male, and trauma-prone—compared to older non-smokers who carry a greater burden of chronic comorbidities, underscoring a critical confounding by indication. Preoperative laboratory profiling reveals smoking’s unique physiological impact, most notably subclinical hepatotoxicity in active smokers, arguing against a uniform risk classification and supporting targeted preoperative testing. The combination of anemia and active smoking identifies a patient group at the highest absolute risk for prosthetic joint infection, compelling the need for integrated prehabilitation protocols that simultaneously address both modifiable risk factors.

Within the varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency surgical cohort, active smokers with venous disease represent a unique demographic paradox: they are younger with fewer chronic comorbidities yet develop severe pathology earlier, indicating smoking independently accelerates disease progression. Laboratory analysis reveals active smokers enter surgery with a distinct pro-inflammatory and hypermetabolic physiological state, characterized by liver enzyme elevation and leukocytosis, despite their younger age and fewer overt organ dysfunctions. While a clinical synergy between venous disease and smoking is plausible, this study was underpowered to statistically confirm it, highlighting a critical need for large-scale, multi-center studies to definitively investigate this high-risk interaction.

Within the hepatitis and hepatic steatosis surgical cohort, Active smokers represent a distinct demographic paradox: they are younger with fewer chronic cardiometabolic diseases, yet require intervention earlier due to smoking’s role in precipitating acute trauma, highlighting a critical confounding by indication. The combination of active smoking and pre-existing liver disease identifies a high-risk clinical phenotype for postoperative infection, necessitating a dual-focused preoperative strategy of smoking cessation and liver optimization, despite a lack of statistically significant interaction in this analysis. Preoperative laboratory profiling reveals a lasting legacy of tobacco use, with former smokers showing persistent hematological and renal abnormalities, while active smokers exhibit a distinct profile of hepatic injury and nutritional deficit, mandating comprehensive screening for all patients with a smoking history.

Within the tuberculosis surgical cohort, smoking status defines distinct clinical trajectories, with active smokers presenting decades younger due to trauma-prone profiles, while former smokers exhibit an intermediate risk with persistent hematological abnormalities, underscoring the need for tailored preoperative optimization. Preoperative laboratory analysis reveals smoking-specific end-organ dysfunction, notably hepatic stress in active smokers, which is often missed by standard comorbidity indices, highlighting the necessity for enhanced preoperative metabolic screening. A history of tuberculosis was identified as a potent, independent risk factor for severe postoperative infection, with point estimates suggesting risk compounding by smoking, signaling an urgent need for intensified prophylactic measures in this high-risk group.

Within the COPD surgical cohort, a clear risk gradient exists in COPD patients, with active smokers being younger and male, while both current and former smokers exhibit distinct physiological markers like polycythemia, necessitating tailored preoperative consideration beyond age. Active smokers with COPD present a unique preoperative risk profile characterized by significant hepatic stress, indicated by elevated transaminases, which contrasts with their younger age-related sparing from anemia and renal dysfunction. Pooled data suggest a concerning, counterintuitive signal for highest PJI risk in non-smoking COPD patients, potentially indicating severe baseline systemic inflammation; however, the small sample size precludes confirmation of a significant interaction with smoking and highlights the need for larger studies.

Pathophysiological Correlation to Orthopaedic Failure

The synergy we observed is explainable through well-established biology that is particularly deleterious to orthopaedics. Firstly, nicotine and hypoxia directly inhibit osteoblast proliferation and function [

8], while carbon monoxide critically reduces oxygen delivery to the healing site. In diabetics, hyperglycaemia further impairs osteoblast function and collagen cross-linking [

9]. This dual assault explains the tripled rate of non-union and implant failure we observed. Secondly, smoking causes ciliary paralysis and defective neutrophil chemotaxis [

10], while diabetes compounds this with neutrophil dysfunction and microangiopathy [

11]. This collapse of innate immune defence explains the significantly higher rates of PJI. Thirdly, coagulopathy from hepatic dysfunction, exacerbated by smoking-induced platelet hyperaggregability, leads to the “persistent oozing” and haematoma-rich environment reported intraoperatively.

Clinical Implications: A Call for “Integrated Physiological Prehabilitation”

Our findings mandate a paradigm shift from isolated risk factor management to integrated “Physiological Prehabilitation.” Elective surgery in an active smoker with a significant comorbidity should be deferred until a targeted optimisation pathway is completed. We propose:

The Diabetic Smoker: Mandatory smoking cessation (≥4 weeks, verified by cotinine testing) and HbA1c optimisation (<7·5% ideal).

The Anemic Smoker: Correction of anemia (Hb >10 g/dL) with IV iron, EPO, or transfusion is mandatory before considering surgery.

The Patient with Hepatic Dysfunction: Optimisation must focus on correcting coagulopathy (INR <1·5) and thrombocytopenia. The added risk of smoking is unacceptable and must be ceased.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Its retrospective, single-center design introduces potential for unmeasured confounding. Smokers with comorbidities may have other unmet social determinants of health that contribute to poor outcomes. The use of self-reported smoking status is susceptible to misclassification bias, likely underestimating the true effect size. The generalizability of our findings should be validated in a multi-center, prospective cohort.

Conclusions

Smoking synergises with comorbidities to define a high-risk orthopaedic surgical phenotype characterised by physiological frailty, intraoperative instability, and a dramatically elevated risk of implant failure, non-union, and periprosthetic infection. The biological imperative for successful orthopaedic surgery is a healthy host environment—an imperative directly and multiplicatively undermined by the combination of smoking and comorbidity. Recognising this synergistic peril is the first step. Acting on it through mandatory, integrated smoking cessation and comorbidity optimisation pathways is an essential next step to improving outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Contributors

All authors approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Appendix

The appendix is provided as Supplementary data and includes 6 sub-cohort analyses, 6 figures, 36 tables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Methodology, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Software, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Validation, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Formal Analysis E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Investigation, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Resources E.S.-I., D.M.-R., B.L.-G. and M.B.-I.; Data Curation, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., A.S., B.L.-G., V.M. and M.B.-I.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.S.-I., D.M.-R., B.L.-G. and M.B.-I.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.S.-I., D.M.-R. and M.B.-I.; Visualization, E.S.-I. and D.M.-R.; Supervision, E.S.-I. and D.M.-R.; Project Administration, E.S.-I. and D.M.-R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Sharing

The de-identified participant data that underlie the results reported in this article will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, following publication. A proposal with a detailed statistical analysis plan will be required for approval.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the County Emergency Clinical Hos-pital of Tîrgu Mureș (Protocol number Ad. 14346 and date of the approval 28.05.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective, observational nature of the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to the administrative and data management staff of the County Emergency Clinical Hospital of Tîrgu Mureș for their invaluable assistance in facilitating the data retrieval process for this study. We would also like to thank the medical and research community at the University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology “George Emil Palade” for their ongoing support and scholarly discourse. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI for the purposes of initial grammar and clarity checks on early drafts. The authors have thoroughly reviewed, edited, and take full responsibility for the entire content of this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| aOR |

Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| ALT |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AP |

Attributable Proportion |

| ASA |

American Society of Anesthesiologists (Physical Status Classification System) |

| AST |

Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| CVD |

Chronic Venous Disease |

| DM |

Diabetes Mellitus |

| EBL |

Estimated Blood Loss |

| EPO |

Erythropoietin |

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| HbA1c |

Hemoglobin A1c |

| INR |

International Normalized Ratio |

| IV |

Intravenous |

| PJI |

Periprosthetic Joint Infection |

| RERI |

Relative Excess Risk due to Interaction |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

References

- Einhorn TA. The cell and molecular biology of fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; 355(suppl): S7–21. [CrossRef]

- Gristina AG. Biomaterial-centered infection: microbial adhesion versus tissue integration. Science 1987; 237: 1588–95. [CrossRef]

- Jupiter JB, Ring DC, Rosen H. The complications and difficulties of management of nonunion in the severely obese. J Orthop Trauma 1995; 9: 363–70. [CrossRef]

- Frisch NB, Courtney PM, Della Valle CJ. Perioperative smoking cessation in orthopedic surgery: a review of current evidence. JBJS Rev 2015; 3: e1.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.

- Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery: the pathophysiological impact of smoking, smoking cessation, and nicotine replacement therapy: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 1069–79. [CrossRef]

- Møller AM, Villebro N, Pedersen T, Tønnesen H. Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 114–17. [CrossRef]

- Raikin SM, Landsman JC, Alexander VA, Froimson MI, Plaxton NA. Effect of nicotine on the rate and strength of long bone fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; 353: 231–37. [CrossRef]

- Kayal RA, Tsatsas D, Bauer MA, et al. Diminished bone formation during diabetic fracture healing is related to the premature resorption of cartilage associated with increased osteoclast activity. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22: 560–68. [CrossRef]

- Arcavi L, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and infection. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 2206–16. [CrossRef]

- Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, Le Goff MC, Allannic H, Genetet B. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet Med 1997; 14: 29–34.

- Snell-Bergeon JK, Wadwa RP. Hypoglycemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Technol Ther 2012; 14(suppl 1): S51–58. [CrossRef]

- Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 2287–323. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388: 1659–724. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz M, Acheson AG, Auerbach M, et al. International consensus statement on the peri-operative management of anaemia and iron deficiency. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 233–47. [CrossRef]

- Northup PG, Garcia-Pagan JC, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Update: coagulation in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2021; 161: 1020-28.e1.

- Raffray L, Bayon Y, Richez M, et al. Tuberculosis in the intensive care unit: a descriptive analysis in a low-burden country. J Crit Care 2014; 29: 679–84. [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2024 report). 2024.

- Knops SP, van Eijk RTA, van der Wees PJ, et al. The effect of preoperative smoking cessation and smoking dose on postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth 2023; 90: 111222.

- Thomsen T, Villebro N, Møller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 2014(3): CD002294. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery: the clinical impact of smoking and smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Surg 2012; 147: 373–83. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D. H., Lee, G. S., & Kim, H. D. (2021). The Impact of Smoking on Bone Metabolism and Fracture Healing: A Review. Journal of Bone Metabolism, 28(3), 167–174.

- Tande, A. J., & Patel, R. (2014). Prosthetic Joint Infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 27(2), 302–345.

- Martin, E. T., Kaye, K. S., Knott, C., et al. (2016). Diabetes and Risk of Surgical Site Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 37(1), 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Spahn, D. R., Schoenrath, F., Spahn, G. H., et al. (2019). The effect of perioperative anemia on clinical and functional outcomes in patients with hip fracture. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 33(6), 294–301.

- Thomsen, T., Villebro, N., & Møller, A. M. (2014). Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), CD002294. [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A., & Mannucci, P. M. (2011). The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(2), 147–156. [CrossRef]

- Santa Mina, D., Clarke, H., Ritvo, P., et al. (2018). Effect of total-body prehabilitation on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy, 100(3), 196–207. [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, A., Snow, V., Fitterman, N., et al. (2006). Risk assessment for and strategies to reduce perioperative pulmonary complications for patients undergoing noncardiothoracic surgery: a guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(8), 575–580. [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, M. B., Fullman, N., Ng, M., et al. (2017). Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet, 389(10082), 1885–1906. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).