1. Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence has quickly become a groundbreaking technology, transforming creative fields by allowing the fast and flexible creation of visual, textual, and spatial content [

1]. Within design areas, AI opens up fresh possibilities for inspiration, automation, and experimentation, helping to broaden creative options while cutting down on labor-intensive manual tasks [

2].

In architecture, AI tools are increasingly influential during the initial stages of concept development and visualization [

3]. These platforms enable architects to turn abstract ideas into visual forms, often bridging the gap between imagination and tangible design [

4]. Recent research has shown the potential of these technologies in crafting innovative façade concepts, experimenting with spatial layouts, and offering rapid alternatives for early sketches [

5]. Still, incorporating AI into architectural workflows is largely experimental, with performance varying widely depending on the platform and the prompt’s complexity [

6].

Although interest is growing, much of the current research focuses on the capabilities of single AI systems, with few studies offering a broad comparison across multiple platforms [

7]. Additionally, there has been limited exploration of how different AI systems handle the same complex architectural prompt, and how this impacts the coherence of the design, the realism of materials, and the stylistic fidelity of the results [

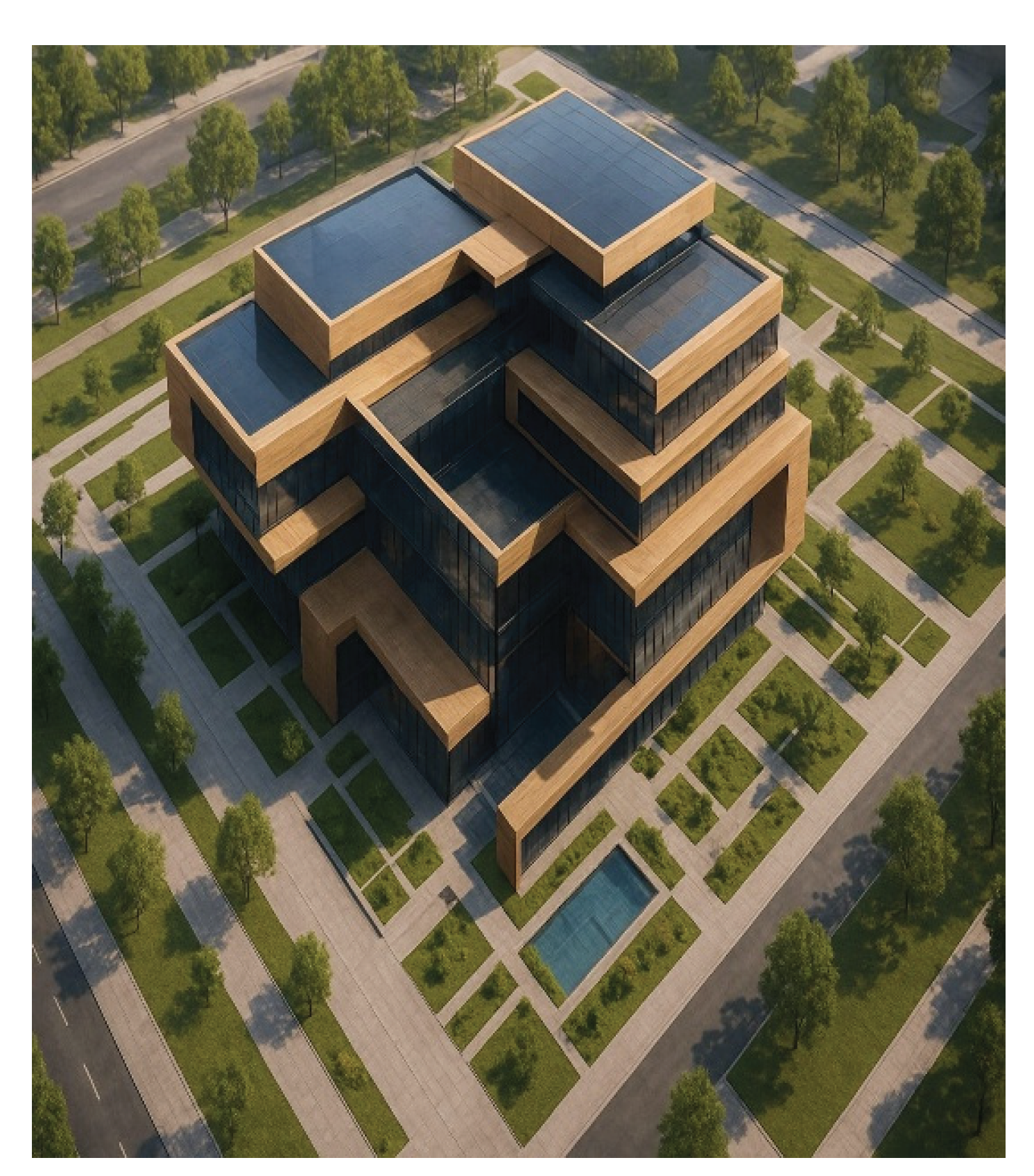

8]. This study aims to fill that gap by applying one consistent prompt to ten generative AI platforms, using the baseline image provided in

Figure 1 as a reference [

9].

The goals of this study are threefold: first, to assess and compare the results from multiple AI systems under the same design conditions; second, to examine their strengths and weaknesses in producing architectural visuals that reflect the style of Jean Nouvel; and third, to offer guidance on how architects might effectively integrate these technologies into design exploration, with an eye toward future sustainable and safe architectural applications [

10].

2. Methodology

Structured experiment to examine how various generative AI platforms interpret and visualize a complex architectural prompt [

11].

The chosen prompt (see Appendix A) depicted the transformation of stacked wooden sticks into a contemporary administrative headquarters located in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital, reflecting the design style of Jean Nouvel [

12].

An initial reference image (previously shown in

Figure 1) established the intended visual direction [

13].

The analysis compared ten different platforms: Gemini 2.5 Flash Image (Nano Banana), Gamni, Lookx, Leonardo.A, Stable Diffusion Online / SD Web Playgrounds, BlueWillow, ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion Web, Playground AI, and Hugging Face Space [

14].

Each platform was instructed to generate images solely based on the given prompt, without allowing any extra modifications or iterative improvements [

15].

The number of images produced varied according to each platform’s default setting: Gemini and Gamni each provided one image, Lookx generated two, Leonardo.A and Stable Diffusion Online each produced four, while BlueWillow, ChatGPT, Playground AI, and Hugging Face Space each created one, and Stable Diffusion Web contributed two [

16].

All resulting images were systematically organized for further analysis [

17].

To compare the outputs, a framework was developed focusing on five key aspects: architectural coherence, adherence to Jean Nouvel’s style, material realism, spatial layout, and overall visual quality [

18].

These criteria were assessed qualitatively, with cross-checks performed to maintain fairness in the evaluation [

19].

For transparency,

Table 1 presents an overview of the experimental setup, detailing the platforms tested, the quantity of images generated, and the evaluation criteria applied [

20].

3. Results

The results from the ten platforms showed notable variation in both how faithfully they reflected the original concept and their interpretation of the architectural prompt. Some platforms closely matched the intended design, while others produced images that diverged significantly from the architectural vision [

21].

Leonardo.A and Stable Diffusion Online / SD Web Playgrounds delivered the most impressive results, exhibiting strong realism, consistent stylistic elements, and authentic material representation. Their images clearly conveyed spatial structure and included evident influences from Jean Nouvel’s geometric abstraction (Representative examples from these

Figure 4.

Stable Diffusion Online.

Figure 4.

Stable Diffusion Online.

Figure 5.

Stable Diffusion Online.

Figure 5.

Stable Diffusion Online.

On the other hand, platforms like Lookx and Hugging Face Space had difficulty capturing the core architectural idea. Their outputs often appeared overly abstract, resulting in distorted forms and unclear material details (Examples illustrating these challenges are shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) [

23].

Gemini 2.5 Flash Image (Nano Banana) and Gamni produced visually appealing images quickly, though their architectural accuracy was inconsistent, often favoring style over precise spatial arrangement (Selected images are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) [

24].

The images from BlueWillow and ChatGPT tended to feature more generic building shapes and did not fully represent the concept of stacked wooden sticks. While their results were visually consistent, they missed the unique stylistic characteristics typical of Jean Nouvel’s work (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 display these examples) [

25].

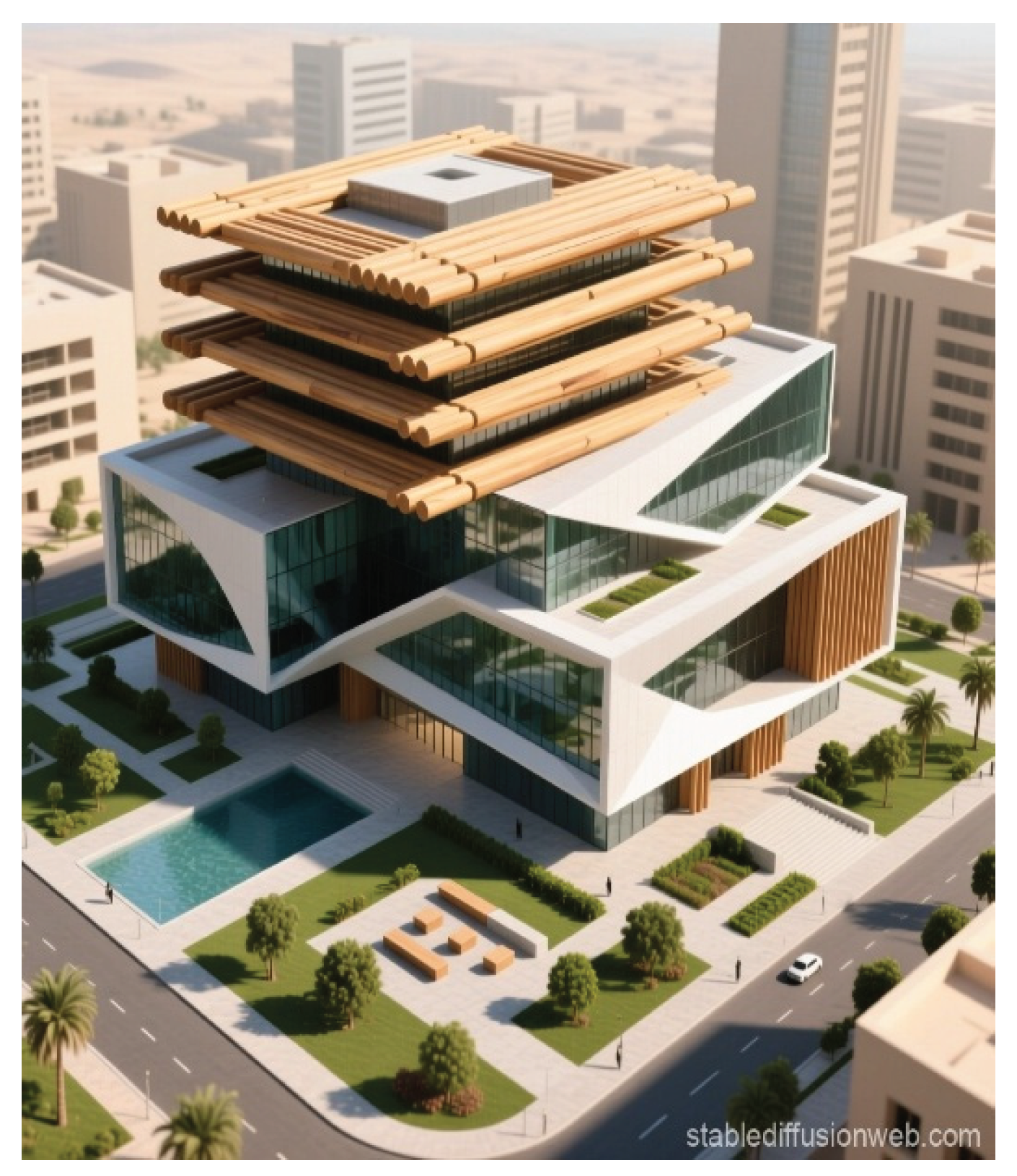

Stable Diffusion Web and Playground AI generated clear and rapid images; however, their interpretations simplified the architectural intent, leaning toward traditional massing rather than inventive, abstract geometry (Refer to

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 for samples from these platforms) [

26].

In summary, the comparative evaluation revealed a wide range of results, spanning from detailed and faithful renderings by Leonardo.A and Stable Diffusion Online to more abstract and fragmented representations from Lookx and Hugging Face Space, with other platforms producing outcomes that fell between these extremes [

27].

Table 2.

.

| Platform |

No. of Images |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

| Leonardo.A |

4 |

High realism, strong material detail, Jean Nouvel style clear |

Minor abstraction issues |

| Stable Diffusion Online |

4 |

Consistent, spatial clarity, photorealistic |

Slight simplification in details |

| Lookx |

2 |

Fast generation |

Overly abstract, distorted geometry |

| Hugging Face Space |

1 |

Quick processing |

Results unclear, low architectural fidelity |

| Gemini 2.5 Flash (Nano Banana) |

1 |

Appealing visuals, fast |

Weak spatial arrangement |

| Gemini |

1 |

Visually attractive |

Inconsistent architectural logic |

| BlueWillow |

1 |

Generic but neat visuals |

Missed concept, limited abstraction |

| ChatGPT |

1 |

Clear imagery |

Too generic, lacked Jean Nouvel style |

| Stable Diffusion We |

2 |

Clear, rapid output |

Too generic, lacked Jean Nouvel style |

| Playground AI |

1 |

Very fast |

Traditional forms, lacked abstraction |

4. Discussion

The comparison of results offers several key takeaways about the use of generative AI in architectural design processes. Firstly, although certain platforms closely followed the original prompt, the differences between platforms indicate that the outcomes are influenced just as much by the unique algorithms of each system as by the prompt itself. This points to a fundamental challenge: architects cannot fully control or foresee the visual results, even when working with the same input [

28].

Secondly, platforms like Leonardo.A and Stable Diffusion Online stood out for their ability to blend photorealistic detail with coherent spatial arrangements. Yet, even these more advanced tools sometimes struggled to maintain accurate material representation and consistent proportions, highlighting the ongoing need for human oversight and refinement of AI-generated images [

29].

Thirdly, tools such as Lookx and Hugging Face Space illustrate the potential pitfalls of using less developed or limited AI platforms. Their outputs often stray so far from architectural reasoning that they contribute little to the design exploration process. This emphasizes how crucial it is to choose the right platform based on the particular stage of design and its intended purpose [

30].

More broadly, generative AI seems best suited to serve as a catalyst for ideas rather than a replacement for architects. It enables fast and varied visualizations that can spark creativity but does not replace expert judgment in essential aspects like technical viability, structural soundness, or sustainable design integration [

31].

The study also highlighted a gap in the existing research, as quantitative benchmarks are largely absent. Future work should move beyond qualitative reviews and incorporate measurable factors—such as rendering speed, image resolution, and feedback from users—to build more robust and objective comparisons [

32].

Lastly, the study’s scope was limited by using just one prompt and excluding iterative refinement, which many architects would normally apply. While these choices ensured fairness in comparison, they mean the findings reflect only one perspective on how AI tools might perform in real design workflows [

33].

5. Recommendations

Based on practical experiments across several generative AI platforms, the findings suggest that while AI offers significant potential in architectural visualization, it should be used as a supportive tool rather than a replacement for architects.

The role of the architect remains essential in making informed design decisions, evaluating spatial logic, and ensuring technical and cultural relevance—tasks that AI platforms alone cannot achieve.

Architects are encouraged to use generative AI primarily for idea generation and rapid visualization, while relying on professional expertise to refine, evaluate, and translate these ideas into realistic and buildable designs.

Future research and practice should focus on combining AI-generated outputs with iterative design processes, where architects critically adjust and adapt AI suggestions instead of accepting them as final solutions.

It is also recommended that further studies adopt quantitative benchmarks (e.g., rendering speed, resolution quality, user evaluation) to complement qualitative assessments and provide a more holistic comparison of generative AI tools.

6. Conclusion

This research assessed ten generative AI platforms using a single architectural prompt to examine their capacity to generate coherent, stylistically accurate, and visually engaging conceptual designs. The findings indicated that some platforms, like Leonardo.A and Stable Diffusion Online, successfully combined realism with abstraction, while others were less consistent or effective in producing meaningful architectural imagery [

34]. The main takeaway is that generative AI shows great potential as a complementary tool in the early phases of architectural design, but it cannot replace the expertise of professional designers [

35]. Architects need to carefully evaluate AI-generated visuals, applying their technical understanding, design judgment, and practical considerations to interpret these outputs properly [

36]. Looking ahead, further studies should expand the investigation by using a variety of prompts, incorporating iterative design refinements, and employing quantitative evaluation techniques [37]. Additionally, connecting AI-generated designs to practical architectural challenges—such as sustainable building systems, radiation protection, and secure spatial layouts in sensitive areas—could highlight the practical value of these technologies in modern architectural practice [38].

References

- American Institute of Architects (AIA) (2017) Document B101™–2017: Standard form of agreement between owner and architect. AIA National.

- Arsanjani, A. (2024) ‘The GenAI reference architecture. Medium. Available at: https://dr-arsanjani.medium.com/the-genai-reference-architecture-605929ab6b5a (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- Brunel University Library (2025) Referencing generative AI. Available at: https://libguides.brunel.ac.uk/citation/gen-ai (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- Brown, T.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Brown University Library (2023) Citation and attribution for generative AI. Available at: https://libguides.brown.edu/citation/ai (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- Goodfellow, I.; et al. Generative adversarial networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google (2023) Gemini: Release notes and version history. Google AI Blog.

- Ho, J.; et al. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Hugging Face (2023) Transformers for architectural design. Available at: https://huggingface.co (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- IBM (2023) What is artificial intelligence? Available at: https://www.ibm.com/topics/artificial-intelligence (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- Isola, P.; et al. (2017) ‘Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1125–1134.

- Jang, S. , Roh, H. and Lee, G. Generative AI in architectural design: Application, data, and evaluation methods. Automation in Construction 2025, 165, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P. and Welling, M. (2013) ‘Auto-encoding variational Bayes. arXiv:1312.6114.

- Kocaballi, A.B.; et al. Personalization in AI-based health interventions. Journal of Medical Systems 2019, 43, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. and Davenport, T. The environmental impact of data centers and AI. Nature Climate Change 2023, 13, 512–515. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, V.; et al. (2021) ‘Prompt-based learning for natural language processing. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Intelligent Systems, pp. 112–125.

- McCarthy, J. (2007) What is artificial intelligence? Stanford University.

- Microsoft (2023) Copilot: AI-powered design assistance. Microsoft Azure AI Services.

- Midjourney (2023) Midjourney version updates. Available at: https://midjourney.com (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- NVIDIA (2023) GPU-accelerated AI for architectural design. NVIDIA Developer Blog.

- OpenAI (2023) ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. Available at: https://chat.openai.com/chat (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- OpenAI (2023) ChatGPT release notes. Available at: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- Purdue University Libraries (2023) How to cite AI-generated content. Available at: https://guides.lib.purdue.edu/cite-ai (Accessed: 16 September 2025). ).

- Radford, A.; et al. (2021) ‘Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 8748–8763.

- Ram, A.; et al. Advances in conversational AI: Transfer learning and reinforcement learning. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2020, 68, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; et al. (2022) ‘High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 10684–10695.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) (2024) AI in architecture: A report on adoption and impact. RIBA Publications.

- Ryan-Mosley, T. The rise of AI-generated propaganda. MIT Technology Review 2023, 126, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn, N.; et al. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 8634–8647. [Google Scholar]

- Stability AI (2023) Stable Diffusion: Technical report. Available at: https://stability.ai (Accessed: 16 September 2025).

- Strubell, E.; et al. (2019) ‘Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in NLP. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 3645–3650.

- Stuart, J. and Norvig, P. (2021) Artificial intelligence: A modern approach. 4th edn. Pearson.

- Tegmark, M. (2017) Life 3.0: Being human in the age of artificial intelligence. New York: Knopf.

- Wei, J.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; et al. (2023) ‘Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. arXiv:2305.10601.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. (2023) ‘Outline-of-thought: Structured prompting for hierarchical text generation. Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 7895–7907.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).