1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

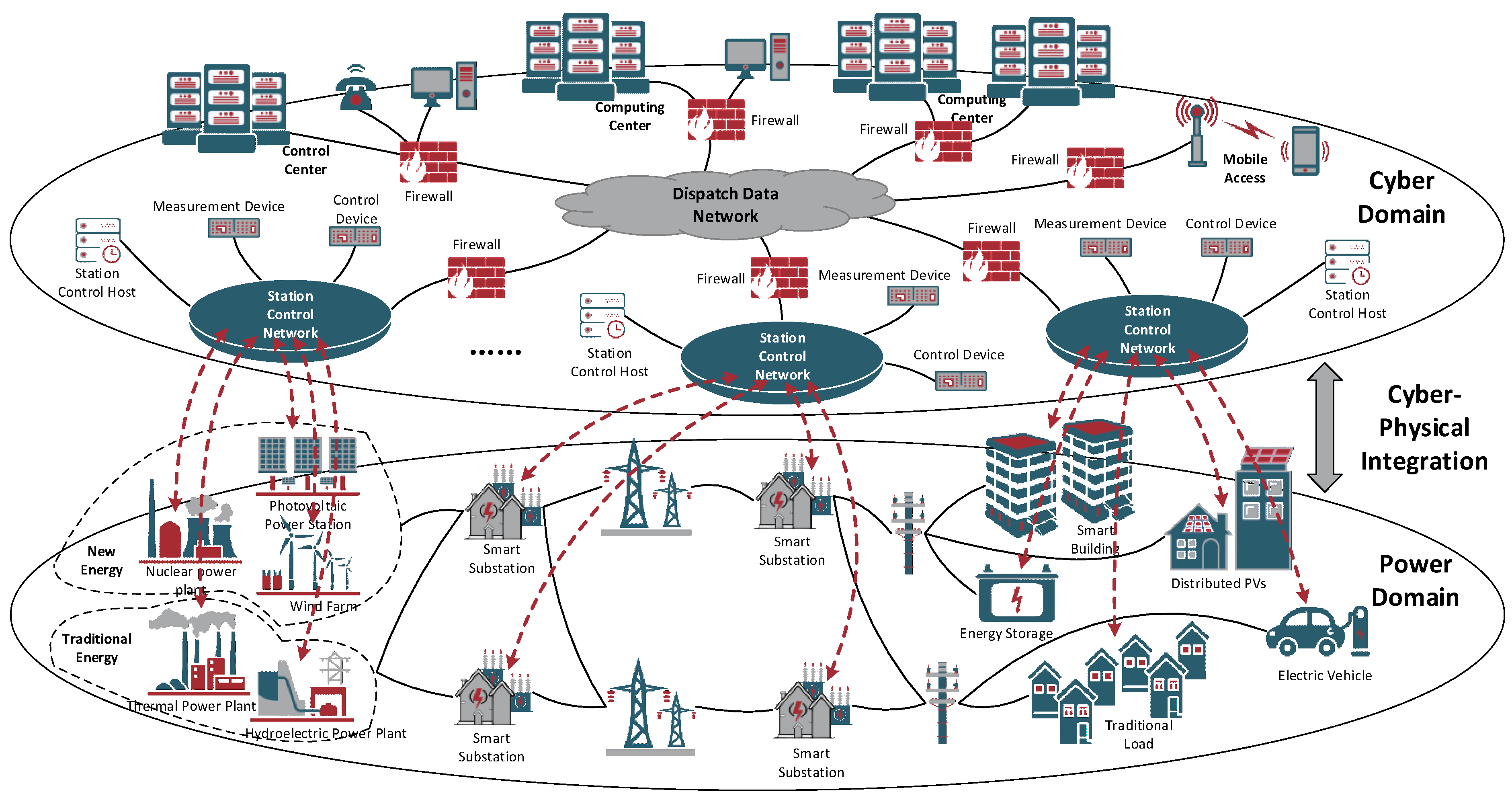

The digital transformation of electrical infrastructures is rapidly reshaping modern power systems into Power Cyber-Physical Systems (Power CPSs)—interconnected networks of physical assets, communication protocols, and intelligent control modules [

1,

2,

3], as shown in

Figure 1 [

4]. This transformation unlocks opportunities for optimization, fault detection, and real-time control, but also introduces new vulnerabilities in terms of data privacy, adversarial attack surfaces, and systemic trust [

5].

Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a promising paradigm to enable collaborative intelligence among power system stakeholders—such as transmission operators, distribution networks, microgrids [

6,

7], and electric vehicle (EV) aggregators [

8,

9]—without sharing raw data [

10,

11,

12]. By training models locally and aggregating updates, FL complies with data sovereignty regulations and privacy mandates, which makes it particularly attractive for privacy-sensitive domains such as Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) [

13] and EV charging infrastructures [

14,

15].

Yet, direct adoption of FL in Power CPSs faces critical

trust barriers. Although privacy-preserving by design, FL is inherently vulnerable to malicious participants, model poisoning, free-rider behaviors, and the lack of interpretability. These weaknesses are unacceptable in safety-critical systems, where resilience, accountability, and ethical deployment are non-negotiable [

16]. Traditional metrics such as accuracy and convergence fail to capture the full requirements of trustworthy operation in power grids.

To bridge this gap, the paradigm of Trustworthy Federated Learning (TFL) has emerged [

17,

18]. Unlike conventional FL approaches that focus primarily on privacy, TFL expands the scope to encompass five interdependent pillars: robustness against adversarial manipulation [

19]; fairness in performance across heterogeneous clients; explainability to ensure transparent and interpretable decisions [

20]; accountability via auditable and secure learning workflows; and resilience to maintain operation under disruptions such as communication delays or client dropouts [

21,

22]. Together, these dimensions form the foundation of a trustworthy federated framework tailored to the high-stakes environment of power system operations.

Despite increasing attention, the literature remains fragmented. Most works address isolated technical aspects—such as secure aggregation or differential privacy—while lacking a unified view of trust as a multi-dimensional system requirement in Power CPSs. This review responds to that gap by integrating existing research, introducing a holistic trust framework, and mapping architectural paradigms to the specific challenges of Power CPSs.

1.2. Contributions of this Review

This review advances the understanding of Trustworthy Federated Learning (TFL) in Power CPSs through three key contributions:

Multi-Dimensional Trust Framework: We propose a holistic trust perspective that extends beyond privacy to encompass security, resilience, and explainability, while also addressing fairness and accountability. Unlike conventional FL surveys, this framework positions trust not as a single technical requirement but as a cross-cutting operational principle essential for heterogeneous and safety-critical CPS environments.

Architecture–Trust–Application Mapping: We establish a structured mapping that links federated learning architectures—horizontal, vertical, cross-silo, cross-device, zero-trust, personalized, and digital twin–enhanced—to their corresponding trust characteristics and practical applications in power systems, such as load forecasting, intrusion detection, EV coordination, and microgrid management. This integration clarifies deployment trade-offs and highlights research gaps.

Threat–Defense–Gap Synthesis: We deliver the first Power CPS–specific synthesis that systematically maps adversarial threats (e.g., poisoning, backdoors, Sybil, Byzantine, and false data injection) to evolving defenses (robust aggregation, differential privacy, secure multi-party computation, blockchain, and zero-trust validation). By identifying both strengths and open gaps, we provide a critical agenda for developing adaptive, hybrid, and resilient defense frameworks.

2. Foundations of TFL in Power CPS

2.1. Overview of Federated Learning in Power CPSs Context

A power CPS typically comprises three tightly coupled layers—cyber, integration, and physical—highlighting the interplay between data, control, and energy flows. This layered architecture provides the foundation for understanding how FL can be embedded within power system operations. FL is a decentralized paradigm in which multiple clients—such as substations, renewable energy assets [

23,

24], or EV charging clusters—collaboratively train a global model while keeping their raw data local [

25,

26,

27]. This inherently aligns with data locality, privacy mandates, and the heterogeneous nature of power infrastructure systems [

28].

In FL for Power CPSs, the overarching goal is to collaboratively train a global model by leveraging distributed data from multiple entities such as substations, renewable plants, and EV clusters, without centralizing sensitive measurements. Physically, this formulation reflects the idea that each client contributes to the system-wide intelligence based on its own operational data, while preserving local privacy and autonomy. The global optimization objective can be expressed as:

where

w denotes the global model parameter vector of dimension

d, which is jointly optimized across all participating clients. The total number of clients is

N, representing distributed entities such as power plants, substations, or EV aggregators. Each client

i is assigned a weight

, typically normalized according to the size of its local dataset

. The function

corresponds to the local objective defined on client

i, expressed as the expected loss

over a training sample

drawn from

. Collectively, these definitions capture how the global model integrates heterogeneous data contributions from diverse CPS components while preserving local autonomy.

To operationalize the global optimization in federated learning, each client performs local stochastic gradient descent (SGD) updates before communicating with the central server. This process reflects the physical setting of Power CPSs, where substations, renewable assets, or EV fleets independently process their data and only share model updates rather than raw measurements. The global model is then aggregated from these local updates, ensuring both efficiency and privacy. Formally, the procedure is described as:

Here, denotes the local model parameters of client i at communication round t and local iteration k, while represents the global model at the beginning of round t. Each local update is computed using a learning rate and a sampled data point from the local dataset. After K local steps, the final local model is sent to the server. The central server aggregates the participating clients by a weighted average, where the weights are proportional to the local dataset sizes . This formulation embodies the FedAvg algorithm, which balances global consistency with local autonomy, making it well-suited for heterogeneous and distributed Power CPS environments.

In Power CPSs, FL facilitates distributed intelligence by supporting both cross-silo and cross-device collaborations [

29,

30]. In cross-silo settings, FL enables coordinated model training among regional transmission system operators or different divisions within a utility, while in cross-device scenarios, it allows edge devices—such as smart meters, phasor measurement units (PMUs) [

31], and DER controllers—to collaboratively learn without exposing raw data [

32,

33]. These modes fit the distributed and autonomous nature of power grids. However, canonical FL formulations overlook domain-specific requirements such as safety, reliability, and adversarial threat models. Hence, embedding trustworthiness into FL becomes indispensable [

34].

2.3. Dimensions of Trust in Federated Learning

Trust in FL is multi-dimensional and interdependent, particularly in mission-critical CPS environments [

35,

36]. To establish a foundational understanding of what constitutes trust in Federated Learning for Power CPSs,

Table 1 delineates the key dimensions of trustworthiness, highlighting their relevance and critical roles in secure and equitable collaborative intelligence.

Each dimension demands domain-aware implementation, often involving new protocols or architectural layers. For instance, privacy may require differential privacy tailored to grid signals, while robustness might require Byzantine-resilient aggregation in environments with variable network latency and node dropout [

37,

38].

2.4. Architectural Paradigms of TFL in Power Systems

To categorize the deployment strategies of Federated Learning tailored to different operational contexts in power systems,

Table 2 presents various FL architectures and their corresponding applications within Power CPSs environments. The increasing complexity of hybrid AC/DC grids and their multi-objective optimization requirements further highlight the need for federated approaches that can accommodate heterogeneous architectures while ensuring privacy and resilience [

39].

While

Table 2 outlines the taxonomy of federated learning architectures, it remains unclear how these architectures map to specific trust characteristics and application domains in Power CPS.

Table 3 bridges this gap by linking representative architectures with their inherent trust dimensions, typical application scenarios, and their strengths and limitations. This mapping highlights not only the diversity of architectural designs but also the practical trade-offs in deploying FL within energy-critical infrastructures.

As illustrated in

Table 3, no single FL architecture can simultaneously guarantee privacy, resilience, fairness, and explainability under the heterogeneous and real-time conditions of Power CPS. This observation underscores the necessity for hybrid or adaptive frameworks that integrate multiple trust dimensions, potentially combining zero-trust mechanisms, digital twin validation, and personalized modeling.

2.5. Trust-Aware Protocol Stack in Power CPSs

This paper proposes a layered abstraction to embed trust into FL deployments for Power CPSs:

Data Layer: Includes privacy-preserving encodings, differential privacy, and local perturbations to protect raw measurements.

Communication Layer: Supports secure multiparty computation, homomorphic encryption, and secure aggregation to ensure confidentiality and integrity.

Aggregation Layer: Implements robust federated averaging with trust weighting, anomaly scoring, and client reputation systems.

Model Layer: Enhances interpretability through explainable AI (XAI), ensures robustness via adversarial training and validation.

Governance Layer: Auditing, rollback mechanisms, incentive-compatible participation, and regulatory compliance modules.

This modular design allows plug-and-play of trust primitives suited to different operational scenarios, offering a foundation for dynamic, secure, and accountable learning in real-time power system environments [

40,

41,

42].

2.5. Why Trustworthiness Is Essential in Power CPSs

Unlike commercial or consumer applications, Power CPSs operate under hard constraints on reliability, availability, and safety [

43,

44]. Model failures can trigger wide-area blackouts or market distortions. Trustworthiness is not optional—it is a functional requirement embedded in:

Grid Protection: Preventing false triggers from poisoned models affecting relay settings or fault classification.

System Restoration: Ensuring reliable decision-making under contingency or disaster recovery conditions.

Operational Markets: Avoiding bias in price forecasts or demand-response coordination.

Human Oversight: Empowering grid operators with confidence in automated recommendations or anomaly alerts.

3. Emerging Threat Landscape in Federated Power CPSs

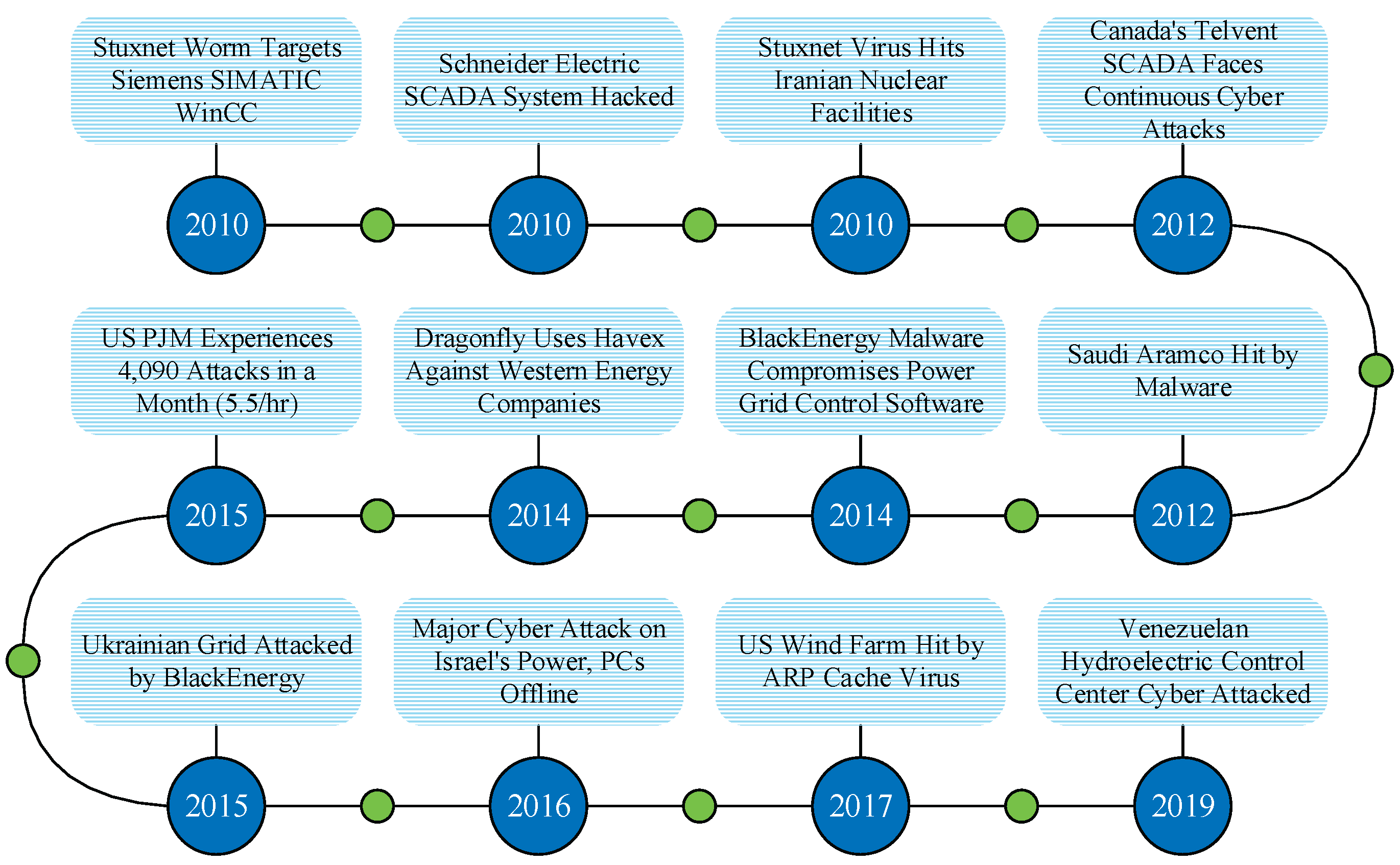

While FL offers structural privacy benefits, its deployment in power CPSs introduces a new class of system-level threats [

45]. These threats exploit both the distributed nature of FL and the criticality of power infrastructure, demanding a systematic rethinking of defense assumptions. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the past decade has witnessed several major cyber incidents targeting power grids worldwide, from the Stuxnet worm in 2010 to recent ransomware attacks on energy companies in 2022 [

4,

46,

47]. These real-world events highlight the increasing sophistication and frequency of cyber threats, reinforcing the urgent need for a trustworthy federated learning paradigm tailored to the unique requirements of power CPSs.

3.1. Adversarial Attacks on FL Models

Power CPSs face an expanded adversarial surface under the FL paradigm, primarily due to the potential presence of malicious or compromised clients in collaborative training [

48]. One critical threat is model poisoning, where adversaries inject biased gradients to skew the global model—for instance, manipulating forecasting models to underestimate peak loads and thereby jeopardizing operational stability [

49,

50,

51]. Another concern is backdoor attacks, wherein attackers implant hidden triggers that cause erroneous behavior only under specific conditions, such as phase angle inputs mimicking false fault signatures [

52]. Despite FL’s decentralization, gradient inversion attacks can still extract sensitive information from shared updates; adversaries may reconstruct load profiles, grid topologies, or event timelines from gradient data. Additionally, free-riding and lazy update behaviors—where certain clients either contribute nothing or provide low-quality updates—can silently degrade model quality and undermine trust in the aggregation process, especially in the absence of effective participation validation mechanisms [

53,

54,

55].

3.2. Cross-Layer CPS-Specific Threats

Federated Learning in Power CPSs operates beyond the confines of model training—it is deeply intertwined with physical devices, grid operational dynamics, and human-in-the-loop decision processes [

56,

57,

58]. This tight coupling exposes the system to cross-domain exploits, wherein adversaries may manipulate external data sources such as weather or transportation streams integrated into multimodal FL pipelines, thereby indirectly influencing energy dispatch or DER control actions [

59,

60]. Moreover, False Data Injection (FDI) via FL presents a growing threat: adversaries may compromise local sensors or edge devices, feeding manipulated inputs into FL-based anomaly detection or state estimation models, which can mislead system responses at scale [

61,

62,

63]. Equally concerning are control loop exploits, where a compromised FL-enabled control agent—such as one managing voltage/frequency in microgrids—can initiate destabilizing actions that propagate through the system, particularly in scenarios relying on minimal human intervention and real-time closed-loop control [

64,

65].

3.3. Threats Unique to Federated Architectures

To expose the diverse and evolving threat landscape that undermines the reliability of Federated Learning in power infrastructures,

Table 4 summarizes key attack types that target clients, models, and communication in Power CPS.

These threats exploit the lack of centralized validation, temporal inconsistency, and heterogeneity inherent to power grids and federated learning [

66,

67].

3.4. Case Study: Threat Simulation in FL-Based Load Forecasting

To illustrate the potential vulnerabilities of FL in Power CPS, consider a federated load forecasting framework deployed across a regional grid involving multiple DER operators [

68]. In this setting, an adversary controlling a subset of clients—say, three compromised DER nodes—can strategically execute a three-step model poisoning attack. First, the attacker injects manipulated gradients into the local model updates, deliberately skewing the global forecasting model to underestimate demand during peak load periods [

69,

70]. Second, to avoid detection by conventional anomaly detection or robust aggregation methods, the attacker mimics benign gradient noise patterns derived from historical training data, thereby camouflaging malicious updates [

71]. Finally, the compromised forecast leads to insufficient dispatch commands from the central energy management system, resulting in frequency instability and potential cascading failures across the power grid [

72,

73,

74]. This example underscores the need for trust-aware defenses that go beyond privacy and consider adaptive robustness and adversarial behavior modeling in federated environments. This scenario shows how FL-specific attacks, when contextualized within Power CPS operations, can amplify physical risks far beyond typical AI domains.

3.5. Summary and Key Insights

Federated Learning in Power CPSs introduces a unique set of vulnerabilities not typically encountered in centralized machine learning frameworks [

75,

76,

77]. These include challenges in inter-client trustworthiness, communication reliability, and dynamic aggregation integrity, especially under adversarial or resource-constrained conditions [

78]. The attack surface in FL deployments is inherently multi-dimensional, spanning cyber (e.g., model poisoning, gradient leakage), physical (e.g., control loop manipulation), and organizational (e.g., insider threats across utilities) layers. These complexities necessitate multi-layered threat models that account for both digital and operational interdependencies [

79,

80]. Furthermore, the safety-critical nature of power systems, coupled with non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data and human-AI decision-making interfaces, amplifies the difficulty of ensuring robust and trustworthy federated learning. Addressing these challenges is pivotal for the reliable integration of FL into real-world Power CPS applications [

81,

82,

83].

The next section will explore how current defense mechanisms—particularly in federated learning—perform in the face of these emerging threats and what limitations must be addressed. Yet, despite the diversity of proposed countermeasures, most existing studies either isolate cyber or physical aspects, lack scalability under non-IID conditions, or fail to capture human-in-the-loop uncertainties. This fragmentation underscores the pressing need for integrated defense strategies that can simultaneously ensure robustness, explainability, and operational feasibility in Power CPS deployments.

4. Defense Mechanisms: State of the Art and Limitations

In response to the evolving threat landscape outlined in

Section 3, a variety of defense mechanisms have been proposed within the FL community. However, their adaptation and effectiveness in Power CPSs remain constrained by operational, architectural, and physical-system-level factors. This section categorizes these defense strategies and critically analyzes their applicability and limitations.

4.1. Robust Aggregation Strategies

To mitigate the impact of model poisoning attacks, robust aggregation mechanisms have been introduced as alternatives to the conventional weighted average used in FedAvg. A widely adopted approach is the geometric median aggregation, formulated as:

where denotes the local update from client i, and is the set of participating clients at round t. Unlike simple averaging, this operator seeks an update vector that minimizes the total Euclidean distance to all local updates, thereby reducing the influence of outliers or malicious clients. Such robust aggregation is particularly relevant in power CPSs, where adversarial manipulation of even a few clients could compromise the safety and reliability of system-wide operations.

Robust aggregation mechanisms are essential in TFL to mitigate the impact of poisoned, anomalous, or strategically manipulated updates during the model aggregation phase [

84,

85,

86]. Traditional federated averaging becomes unreliable in adversarial settings, prompting the use of robust statistical techniques such as median and trimmed mean, which aim to suppress outliers by considering central tendencies rather than full distributions. Krum and Multi-Krum algorithms improve resilience by selecting client updates closest to the geometric center of the majority cluster, under the assumption that most participants behave honestly. More adaptive approaches introduce trust-aware dynamic weighting, where client contributions are scaled based on their historical reliability, anomaly scores, or similarity to consensus trends. However, applying these strategies to Power CPSs introduces unique challenges [

87]. First, the non-IID nature of grid data—influenced by regional demand profiles, DER variability, and market operations—can cause legitimate updates to appear as outliers, thereby reducing accuracy if overly filtered. Second, the assumption of an honest majority may not hold in sparsely connected or cross-organizational settings where client populations are small or loosely monitored. Third, current schemes often lack situational awareness, ignoring contextual factors such as DER criticality or grid emergency states, which are vital for ensuring reliability in safety-critical applications. Hence, robust aggregation in Power CPSs demands more than statistical filtering—it requires integration with domain knowledge and context-sensitive trust calibration [

88,

89,

90].

4.2. Differential Privacy and Gradient Masking

Differential Privacy (DP) is a cornerstone technique in FL for safeguarding sensitive client data during model updates [

91,

92,

93]. By injecting mathematically bounded noise into shared gradients or parameters, DP guarantees that an individual client's data contribution remains indistinguishable within a defined privacy budget, typically denoted as (

ε,).

By clipping each local gradient and injecting calibrated Gaussian noise, DP ensures that the contribution of any individual client remains indistinguishable, even in adversarial settings. This mechanism is formally expressed as:

where is the local gradient of client i, C is the clipping threshold, and controls the privacy–utility trade-off through noise variance.

In the context of Power CPSs, local DP mechanisms perturb gradients at the client level before transmission, offering stronger privacy at the cost of greater noise [

94,

95]. Conversely, global DP strategies apply noise after aggregation, reducing the distortion but requiring trust in the aggregator. Gradient masking complements these approaches by obfuscating update directions, further impeding data reconstruction attempts [

96]. Despite their theoretical robustness, these methods face substantial limitations in power systems. First, the privacy–utility trade-off is particularly acute in real-time applications—such as short-term forecasting or frequency regulation—where even minor performance degradation may have cascading operational impacts [

97]. Second, noise-induced instability can impair convergence and control fidelity, especially in volatile environments with high DER penetration, such as solar PV-dominated microgrids [

98]. Third, DP mechanisms treat all features equally, lacking semantic awareness of grid variables—introducing noise to frequency or protection-related signals could disproportionately compromise system reliability [

99,

100]. As such, deploying DP in Power CPS demands task-specific calibration, utility-aware noise shaping, and integration with domain constraints to ensure both privacy and operational viability.

4.3. Fairness and Heterogeneity in Federated Learning

Beyond privacy and robustness, another critical dimension of trustworthy federated learning in Power CPSs is fairness. In heterogeneous power networks, clients such as regional substations, microgrids, and EV clusters may have vastly different data distributions and computational capabilities. If fairness is not explicitly enforced, global models can become biased toward data-rich or dominant clients, leaving others underrepresented and degrading overall reliability. To address this issue, fairness can be formulated as a variance-regularized optimization problem:

where the first term ensures standard empirical risk minimization across clients, while the second penalizes disparities in local losses. Here, serves as a trade-off coefficient that balances global accuracy with cross-client equity.

While fairness seeks to balance performance across all clients, it is equally important to recognize that heterogeneity in Power CPSs may require personalized solutions. Different regions or assets—such as renewable plants, substations, and EV fleets—often operate under distinct load profiles, environmental conditions, and data distributions. A single global model may thus fail to capture these localized patterns. To accommodate such diversity, personalization is introduced by coupling local objectives with a shared global reference model:

Here, denotes the personalized model parameters for client i, while represents the shared global model. The regularization term ensures that local models remain anchored to the global knowledge base, while still allowing them to adapt to their specific data distributions.

4.4. Personalization for Heterogeneous Clients

While fairness regularization seeks to balance performance across clients, federated learning in Power CPSs must also account for the fact that different clients may require individualized models due to highly heterogeneous environments. For example, renewable plants operate under different weather conditions, while substations or EV clusters experience distinct load patterns. A single global model may therefore fail to capture these diverse local characteristics. To address this limitation, personalization is introduced by coupling local objectives with a global reference model:

In this formulation, denotes the personalized model parameters of client i, while represents the shared global model. The term is the local objective function of client i, and the quadratic penalty term ensures that local models remain sufficiently aligned with the global model. The parameter controls the trade-off between local adaptation and global consistency, while denotes the normalized weight of each client.

4.5. Byzantine-Resilient Algorithms

Byzantine-resilient FL algorithms are explicitly designed to withstand arbitrary, untrustworthy, or malicious behavior from a fraction of participating clients—referred to as Byzantine faults [

101,

102,

103]. In the context of Power CPSs, such resilience is vital due to the potential for compromised edge nodes or adversarial insiders. Algorithms like Bulyan employ a two-tier strategy combining robust client selection and trimmed aggregation to ensure that malicious updates are excluded from the final model. Zeno++ takes a validation-based approach, filtering updates based on their contribution to decreasing a surrogate loss function, thereby suppressing harmful gradients. Robust Stochastic Aggregation (RSA) further mitigates poisoning by introducing a regularization term that penalizes large deviations from the global model, promoting coherence across distributed updates [

104,

105]. Despite their theoretical robustness, these methods face several practical limitations in power system environments. First, their computational and communication overhead can be prohibitive for low-power or bandwidth-constrained edge devices such as smart meters, PMUs, or DER controllers [

106,

107,

108]. Second, some schemes may over-filter non-IID but legitimate updates, a common occurrence in power systems due to geographic, temporal, or operational diversity, thereby impairing accuracy in forecasting or control [

109]. Third, many Byzantine-resilient strategies rely on synchronous update rounds, which conflicts with the inherently asynchronous and event-driven nature of distributed grid assets [

110,

111]. Addressing these limitations calls for lightweight, adaptive, and grid-aware Byzantine mitigation strategies tailored to the unique constraints and dynamics of Power CPSs.

4.6. Adversarial Training and Certification

Adversarial training is a proactive defense technique that enhances the robustness of federated models by exposing them to deliberately crafted perturbations during the training process [

112,

113]. In the context of FL for Power CPSs, this method helps prepare models against worst-case perturbations or adversarial manipulations that could arise from compromised clients or noisy sensor environments. Typical implementations include the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) [

114,

115] and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD) [

116], which are used to generate adversarial examples at the client level, effectively simulating malicious behavior during model updates. More recent developments also explore certified defenses, which aim to offer formal robustness guarantees under norm-bounded perturbations, ensuring that model predictions remain unchanged within a specific threat radius [

117].

However, the practical application of adversarial training in Power CPSs faces multiple challenges. First, the lack of interpretability in adversarial perturbations limits operator trust and makes it difficult to integrate such defenses into human-in-the-loop control workflows or regulatory auditing pipelines [

118]. Second, most certified defense frameworks are built upon fixed and simplistic threat assumptions, rendering them ineffective against the adaptive, co-evolving attack patterns characteristic of real-world power systems—where attackers may exploit time-varying conditions or cross-domain data fusion (e.g., weather plus grid data) [

119]. Third, adversarial training inherently requires extended convergence time and additional computational resources, which contradicts the real-time constraints of critical tasks such as frequency regulation, fault detection, and DER coordination [

120]. To make adversarial defenses viable in Power CPSs, future work must prioritize lightweight, explainable, and dynamically adaptable training frameworks that align with both physical grid constraints and operational trust requirements.

4.7. Blockchain and Secure Multiparty Computation

Blockchain and Secure Multiparty Computation (SMPC) have emerged as promising techniques for enhancing trust in FL by providing verifiable, tamper-resistant computation and preserving confidentiality of model updates [

121,

122,

123]. In the context of Power CPSs, these technologies are often employed to address critical concerns around update integrity, auditability, and secure collaboration among heterogeneous entities. Blockchain frameworks, particularly permissioned blockchains, can be used to log FL-related metadata such as model versions, update timestamps, and authenticated client identities, forming a transparent audit trail that supports accountability and regulatory compliance [

124]. Simultaneously, SMPC protocols enable multiple clients to collaboratively train models without ever revealing their raw gradients or local data, using cryptographic primitives such as secret sharing or homomorphic encryption to ensure privacy-preserving aggregation [

125,

126].

Despite these strengths, integrating blockchain and SMPC into Power CPS FL workflows faces substantial practical barriers. Firstly, latency overheads introduced by blockchain consensus algorithms or SMPC encryption schemes can delay model convergence and compromise real-time control or dispatch decisions, which are often time-critical in power systems. Secondly, high computational and energy costs make these methods ill-suited for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices, such as smart inverters or smart meters, which are prevalent in DER settings [

127]. Finally, while permissioned blockchains improve efficiency compared to public chains, they may introduce a single point of failure or trust bottleneck—particularly if the validating authority is compromised or experiences downtime. These limitations suggest that while blockchain and SMPC offer strong theoretical guarantees, their successful application in Power CPS requires lightweight, grid-aware variants and hybrid architectures that can balance trust enforcement with operational responsiveness [

128,

129].

4.8. Summary Table of Defense Strategies

To address the multifaceted security and reliability risks in federated deployments,

Table 5 presents key defense strategies and critically evaluates their strengths and specific limitations within the operational constraints of Power CPSs.

While

Table 4 and

Table 5 have separately outlined major threats and corresponding defense strategies in federated learning, a direct mapping is necessary to reveal the extent to which current solutions address the unique requirements of Power CPS.

Table 6 provides an integrated perspective by linking representative threats with their defense mechanisms, evaluating their effectiveness, and highlighting remaining gaps. This comparative view not only clarifies the coverage of existing approaches but also exposes unresolved challenges that should drive future research efforts.

As shown in

Table 6, although several mechanisms—such as robust aggregation, differential privacy, and Byzantine-resilient learning—mitigate certain attack vectors, critical gaps remain in scalability, explainability, and adaptability to non-IID and real-time conditions of Power CPS. These limitations underscore the necessity for hybrid frameworks that combine algorithmic robustness with system-level resilience and policy-driven governance.

4.9. Key Takeaways

The defense strategies surveyed in this section reveal a fundamental mismatch between general-purpose FL robustness methods and the unique demands of Power CPSs. Most existing techniques—ranging from robust aggregation to adversarial training and secure computation—were primarily designed for generic, cloud-based FL environments [

130]. As such, they often neglect the real-time operational constraints, system heterogeneity, and safety-critical nature inherent to power systems [

131]. For instance, defenses that assume synchronized client participation or tolerate slow convergence may be unacceptable in grid control applications, where even minor delays can destabilize voltage, frequency, or load balance.

To close this gap, future research must move toward domain-adaptive defense designs that are explicitly tailored to grid contexts. These designs should account for heterogeneous DER behaviors, temporal volatility (e.g., solar ramp rates), and communication limitations, while also supporting human interpretability and intervention [

132,

133]. Importantly, the effectiveness of defenses in Power CPS should be measured not solely by improvements in model accuracy or convergence, but by their impact on physical system safety and resilience—such as the ability to maintain frequency stability, avoid blackouts, or prevent cascading failures under attack. In this light, FL defense becomes not just a machine learning challenge, but a cross-disciplinary effort involving control theory, grid operations, and adversarial modeling [

134,

135,

136].

In the next section, we turn to emerging architectures and paradigms that aim to embed trustworthiness directly into FL frameworks for Power CPSs. Yet, in the absence of unified benchmarks, standardized evaluation metrics, and realistic testbeds spanning both cyber and physical layers, research progress risks remaining fragmented and hard to translate into practical deployment. Addressing this gap requires community-driven efforts that integrate algorithmic advances with system-level validation under real-world grid conditions.

5. Architectures and Design Paradigms for Trustworthy FL in Power CPSs

As discussed in

Section 4, the limitations of conventional FL defense mechanisms underscore the necessity for architectural innovations tailored to the unique constraints of Power CPSs. This section explores emerging architectural designs and paradigms that embed trustworthiness, scalability, and resilience into FL workflows—from foundational trust mechanisms to human-in-the-loop and simulation-integrated systems.

5.1. Zero-Trust Federated Learning Frameworks

The Zero-Trust Federated Learning (ZTFL) paradigm introduces a transformative shift in how participants interact within FL ecosystems, especially in safety-critical environments like Power CPSs [

137,

138]. Departing from traditional FL assumptions—where clients and aggregators are implicitly trusted—ZTFL adopts the “never trust, always verify” doctrine, assuming that any participant can be compromised and must be continuously validated [

139].

Key architectural features include:

Identity Verification: Before any training session, clients must present verifiable cryptographic credentials or participate in decentralized identity frameworks (e.g., blockchain-based identity proofs). This ensures that only authorized grid entities, such as substations or DER controllers, participate in model updates.

Dynamic Trust Scoring: Trust is no longer binary or static. ZTFL dynamically adjusts trust levels based on behavioral analytics—such as update consistency, anomaly detection, and participation history—often integrated with

reputation systems or anomaly scoring algorithms. These scores directly influence model aggregation weights or access privileges [

140].

Policy Enforcement Points (PEPs): Instead of relying on historical reputation or organizational affiliation, PEPs act as

real-time gatekeepers, enforcing fine-grained rules on data usage, update frequency, and contribution thresholds for each training round. This ensures

per-session accountability, preventing misuse even from previously trusted entities [

141,

142].

Relevance to Power CPSs:

In the power grid domain, ZTFL holds particular significance due to the

increasingly decentralized and multi-stakeholder nature of modern energy systems [

143,

144,

145]. For instance:

It prevents insider threats, where compromised DER vendors, third-party service providers, or even internal operator terminals may inject malicious updates under assumed trust.

It enables fine-grained access control, crucial when coordinating learning across mixed criticality assets (e.g., between high-voltage substations and low-impact residential microgrids).

Through cryptographic audit trails and trust enforcement, ZTFL also supports regulatory compliance and post-incident forensics, aligning with critical infrastructure governance policies such as NERC CIP or IEC 62351.

Overall, Zero-Trust FL introduces a proactive trust infrastructure that aligns with both the cybersecurity requirements and operational demands of modern power systems, making it a foundational pillar in the evolution of trustworthy AI-enabled grid intelligence.

5.2. Personalized Federated Learning (PFL)

PFL challenges the foundational assumption of conventional FL—that a single global model is optimal for all participants. This assumption often breaks down in Power CPSs, where client nodes such as substations, microgrids, EV charging stations, or DER controllers operate under vastly different physical conditions, grid topologies, and control objectives [

146,

147,

148]. PFL seeks to balance shared learning with local specialization, enabling each client to benefit from global knowledge while maintaining model fidelity to its own operational context [

149].

Key methodological approaches in PFL include meta-learning, clustering, and multi-task optimization. Meta-learning methods such as FedMeta or Reptile aim to learn a global initialization that can be quickly adapted to each client’s local data through fine-tuning, which is especially valuable in power systems requiring rapid retraining under dynamic conditions like weather changes or shifting load profiles [

150,

151]. Clustered FL organizes clients into groups based on data similarity, operational roles, or geographic proximity—such as microgrids in the same climate zone or feeders with comparable load characteristics—enabling localized yet collaborative learning [

152]. Meanwhile, multi-task FL acknowledges that clients may face different but related objectives, for instance, one optimizing renewable generation forecasting while another ensures voltage control; such models share generalizable features while tailoring solutions to task-specific goals [

154,

155].

5.3. Explainable Federated Learning

XFL aims to embed transparency into the federated learning process, ensuring that both training dynamics and model outputs are understandable to human operators, auditors, and regulators [

156]. Key techniques include model attribution methods such as SHAP, LIME, or gradient-based explanations, which help quantify the influence of specific features on predictions, thereby demystifying black-box behaviors. Audit trails and decision logs capture the sequence of model updates and the rationale behind aggregation outcomes, supporting traceability and accountability. Additionally, operator-facing dashboards deliver intuitive visualizations of model behavior, anomalies, and confidence levels, empowering grid operators to make informed and trustworthy decisions in real time [

157,

158].

In the context of Power CPS, explainable federated learning enhances human-AI collaboration by enabling grid operators to investigate, interpret, or override suspicious outcomes, especially during critical operations. It supports regulatory compliance with emerging AI governance frameworks such as the EU AI Act, where transparency and accountability are mandated. Furthermore, explainability plays a vital role in incident forensics, allowing post-event analysis to trace adversarial manipulations or system faults back to specific model decisions or client contributions [

159].

5.4. Digital Twin-Augmented FL Architectures

Digital twin–augmented federated learning integrates high-fidelity simulations of power system components into the FL training and validation pipeline, enabling risk-free experimentation and enhanced model generalization [

160,

161,

162]. Through sim-to-real transfer, digital twins generate synthetic data under rare or hazardous conditions—such as line faults or cyber intrusions—to strengthen FL robustness. Real-time synchronization ensures that these twin models dynamically update based on live telemetry, supporting continuous model refinement. Moreover, cross-scale co-simulation bridges SCADA-level grid behavior with edge-level FL agents, ensuring consistency between system-wide operations and local control intelligence in Power CPS environments [

163].

In the context of Power CPS, digital twin–augmented federated learning offers several key advantages: it enables risk-free pre-training of FL models prior to deployment, ensuring safety in critical grid applications; it supports resilience testing by simulating synthetic attacks or control anomalies, helping identify vulnerabilities before real-world impact; and it facilitates coordinated defense simulation, allowing joint training of distributed agents such as EV charging nodes, WAMS units, and substation controllers within a unified and realistic virtual environment [

164,

165,

166].

5.5. Human-in-the-Loop Federated Defense

Human-in-the-loop FL integrates expert oversight into automated decision loops, ensuring safety and adaptability without compromising scalability. This approach enables active querying, where FL models identify uncertain or high-impact predictions and defer to human judgment; supports collaborative labeling, leveraging operator insights to refine datasets and improve model quality over time; and allows dynamic role adjustment, modulating the degree of human involvement based on grid stress levels or detected cyber threats—thus promoting resilient and accountable AI-driven operations in Power CPS [

167,

168].

In Power CPSs, human-in-the-loop federated learning plays a critical role in preventing automation bias in high-stakes control scenarios by enabling operators to scrutinize and override model decisions when necessary. It also reduces false positives in intrusion detection by blending statistical outputs with human intuition and domain expertise. Over time, this collaborative interaction supports trust calibration, allowing operators to gradually build confidence in AI-driven processes, thereby fostering safer, more transparent, and more resilient grid operations [

169].

5.6. Comparative Table: Architectural Paradigms

To strengthen trust across the lifecycle of federated learning in critical infrastructure,

Table 7 outlines emerging architectural paradigms that enhance explainability, adaptability, and operational safety in Power CPS applications.

5.7. Summary and Design Principles

Across the surveyed emerging architectures, several unifying principles crystallize for the effective design of trustworthy federated learning systems in Power CPSs. First, modular trust anchors are essential—verifications of identity, behavior, and outcomes should be independently enforced across system layers to avoid single points of failure. Second, hybrid autonomy is key, requiring a careful and dynamic balance between automated FL processes and human operator oversight, particularly in safety-critical grid applications. Third, simulation-real coupling must be embedded into continuous FL workflows, allowing digital twins to simulate edge cases and validate models prior to deployment. Lastly, interpretability-by-design mandates that explainability mechanisms be integrated into the architecture from the outset, rather than appended as afterthoughts, to support human-AI collaboration and regulatory accountability [

170,

171,

172]. In the next section, we move from architectural innovations to practical

use cases, detailing how these paradigms are applied in real-world power systems and what lessons have emerged.

6. Real-World Applications and Lessons Learned

While the prior sections focused on conceptual foundations and architectural innovations, this section grounds the discussion in real-world deployments and operational insights. By reviewing representative applications of trustworthy FL in CPSs, we extract key lessons on feasibility, effectiveness, and open bottlenecks.

6.1. Privacy-Preserving Load and Renewable Forecasting

Accurate forecasting of load demand and renewable generation, particularly wind and photovoltaic power, is fundamental for reliable scheduling and secure operation of modern power grids [

173,

174]. Grid operators and DER owners collaboratively train time-series forecasting models—such as for wind power generation or residential load patterns—without exchanging raw consumption or generation data. This is typically achieved using federated learning frameworks based on LSTM or Transformer architectures, enhanced with differential privacy and PFL techniques. A representative deployment comes from a multi-utility pilot within the EU Horizon 2020 edge computing project, where participants maintained approximately 95% forecasting accuracy while preserving data locality. This not only ensured operational effectiveness but also alleviated compliance challenges with GDPR and other privacy regulations [

175,

176].

Personalization strategies that account for regional heterogeneity—such as varying climatic conditions or load profiles [

177,

178]—substantially enhance model utility and local adaptability. Additionally, implementing communication sparsity techniques, such as event-triggered updates or periodic aggregation, effectively reduces communication overhead while preserving forecasting accuracy, making FL more feasible for real-world Power CPS deployments.

6.2. Collaborative Intrusion Detection for Power CPSs

SCADA systems, substations, and microgrids collaboratively detect cyber-attacks—such as FDIAs and Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS)—by training anomaly detection models in a federated manner. This approach leverages federated autoencoders and graph neural networks (GNNs) enhanced with adversarial training defenses to counter model poisoning [

179,

180]. A simulated cross-regional testbed using WADI and ICS-AD datasets, involving multiple data owners, demonstrated a 23% improvement in attack detection rates compared to isolated models and showed strong resilience against poisoning attacks.

Trust-aware aggregation methods such as Krum and Median are crucial for mitigating the impact of malicious client contributions in federated training. Additionally, incorporating model explainability techniques—such as SHAP values or saliency maps—not only enhances operator confidence but also accelerates incident response by making anomalies and model decisions more transparent [

181,

182].

6.3. FL for EV Charging and V2G Coordination

EV aggregators coordinate charging profiles and provide grid support services—such as frequency regulation—through federated learning without disclosing user-specific behaviors. The approach leverages reinforcement learning–enhanced FL (FedRL) with personalized policies tailored to each fleet. In a regional deployment, EV clusters participated in demand response using a distributed learning controller [

183,

184,

185]. This setup led to an 18% improvement in peak shaving and a 12% reduction in operational costs, all while preserving user privacy.

Key lessons from this use case highlight that trust calibration—through transparent operations and well-designed participation incentives—is crucial for sustaining aggregator engagement, while personalized federated learning policies are necessary to prevent negative transfer across heterogeneous EV clusters, such as those in urban versus rural settings [

186,

187].

6.4. Federated Voltage and Frequency Control in Microgrids

Ensuring stable voltage and frequency in microgrids has emerged as a focal research area, driven by increasing renewable integration and decentralized operation [

188,

189,

190]. Microgrid agents (e.g., inverters, storage systems) collaboratively learn distributed control policies using actor-critic federated learning with simulation pre-training and asynchronous real-time updates, achieving a significant reduction in costs and CO2 emissions [

191,

192].

Bridging the simulation-to-reality gap demands integration of digital twins and robust pretraining, while incorporating local grid codes into FL loss functions is essential to ensure regulatory compliance and stable control behavior in real-world deployments.

6.5. Federated State Estimation in Power Grids

A representative application of trustworthy federated learning in Power CPSs is state estimation (SE), which plays a central role in monitoring and control. In practice, measurement data from SCADA systems or PMUs are often geographically distributed and sensitive, making them well-suited for federated settings. By enabling collaborative training across substations or regions without exposing raw data, TFL can provide accurate and privacy-preserving estimates of system states. The state estimation problem can be formulated as:

Here, denotes the measurement vector, is the measurement matrix, and represents the true system state to be estimated. The term accounts for measurement noise, while is the state estimator parameterized by the federated model w. The client weights ensure that contributions from different regions or assets are properly balanced. This formulation highlights how TFL can be concretely embedded into CPS operations, bridging abstract trust dimensions with real-world power system applications.

State estimation underpins monitoring and control in power grids but is highly vulnerable to False Data Injection (FDI) attacks [

193,

194,

195]. Traditional centralized SE aggregates raw SCADA and PMU data at control centers, raising privacy and scalability concerns [

196,

197,

198,

199]. FL enables collaborative SE across substations or regional operators without sharing raw data, while TFL strengthens resilience against compromised nodes through Byzantine-resilient aggregation, explainability, and digital twin–based validation.

Recent studies show that federated SE can achieve accuracy comparable to centralized methods while preserving data locality and reducing communication overhead [

200,

201]. Key challenges remain in handling non-IID measurement distributions, synchronization under delays, and embedding observability constraints into FL objectives, but TFL-based SE offers a path toward secure and privacy-preserving grid monitoring [

202,

203].

6.6. Substation Automation and Federated Lifelong Learning

Substation intelligent electronic devices adaptively enhance fault classification and control actions over time using federated lifelong learning (FedLL), which incorporates elastic weight consolidation and replay buffers. A field-tested deployment in industrial substations with legacy devices achieved sustained fault detection accuracy exceeding 90% over 12 months, while effectively avoiding catastrophic forgetting [

204,

205,

206].

Substation intelligent electronic devices adaptively enhance fault classification and control actions over time using FedLL, which incorporates elastic weight consolidation and replay buffers. A field-tested deployment in industrial substations with legacy devices achieved sustained fault detection accuracy exceeding 90% over 12 months, while effectively avoiding catastrophic forgetting [

207,

208,

209,

210]. These results demonstrate that lifelong learning enables models to continuously adapt to aging equipment and evolving fault signatures, while also highlighting the necessity of secure update channels and robust device authentication mechanisms in low-trust substation environments to ensure the integrity and reliability of deployed models [

211,

212,

213].

6.7. Summary Table: Use Case Comparison

To illustrate how TFL can be applied across critical power system tasks,

Table 8 presents representative use cases, highlighting the specific FL techniques, trust-enhancing features, and their operational impacts in Power CPSs. These cases cover a broad spectrum ranging from forecasting and intrusion detection to real-time control and fault management, thereby reflecting the versatility of TFL in addressing both data-driven prediction and safety-critical operation. By juxtaposing different application domains, the comparison emphasizes how trust mechanisms such as privacy preservation, robustness, explainability, and continual learning can be selectively integrated to meet domain-specific requirements. Moreover, the table underscores that while individual tasks benefit from targeted TFL adaptations, the overarching trend points toward building a cohesive, trustworthy learning ecosystem that balances accuracy, resilience, and compliance in modern power grids.

While

Table 8 provides an overview of representative application cases, it does not explicitly connect performance outcomes with trust-enhancing features.

Table 9 addresses this gap by linking key application domains with specific FL techniques, performance metrics, and the trust dimensions they strengthen. This mapping highlights both the potential benefits and the practical limitations of applying federated learning in diverse Power CPS tasks.

As seen in

Table 9, different application domains emphasize distinct trust features—privacy in forecasting, robustness in intrusion detection, explainability in substation automation—yet none achieve a comprehensive trust guarantee. This fragmentation reveals the need for unified frameworks that balance accuracy, efficiency, and multi-dimensional trust in real-world power systems.

6.7. Insights and Cross-Cutting Observations

Insights from both real-world and simulated deployments reveal several recurring themes that underpin the successful application of Trustworthy Federated Learning in Power CPSs [

214,

215,

216]. First, context-aware trust mechanisms—such as personalized federated learning and explainability—are essential not only for achieving high technical performance but also for gaining user acceptance and operational trust. Second, resilience testing through digital twins and hybrid architectures enables risk-free validation under rare or extreme conditions, thus enhancing the robustness of deployments. Third, providing trust incentives—including transparency, privacy guarantees, and local control over models—plays a pivotal role in sustaining long-term stakeholder engagement, especially in collaborative ecosystems [

217]. Lastly, in multi-party settings involving diverse actors such as regional utilities and third-party vendors, adopting a zero-trust assumption is imperative to mitigate insider threats and enforce rigorous verification throughout the learning lifecycle [

218,

219,

220].

7. Research Challenges and Future Directions

To operationalize trustworthy FL in CPSs, researchers and practitioners must address a range of open challenges spanning theory, system design, human factors, and policy. This section categorizes these challenges and proposes future research directions across four key dimensions: technical robustness, human-centered trust, system integration, and governance frameworks.

7.1. Technical Robustness and Adversarial Resilience

A core challenge in deploying federated learning within Power CPS lies in ensuring robustness against a wide spectrum of adversarial threats [

221,

222]. Byzantine vulnerabilities continue to pose significant risks in multi-party federated settings, where malicious participants may inject poisoned updates or manipulate aggregation processes to compromise global model integrity. Despite the use of differential privacy, gradient leakage attacks remain a concern—particularly in time-series applications—where adversaries can partially reconstruct sensitive operational data from shared updates. Moreover, adaptive adversaries can dynamically evolve their attack strategies over time, exploiting phenomena such as model drift and overfitting to bypass static defenses, further undermining the reliability and security of FL-based systems in critical power infrastructures.

To overcome these threats, future efforts should focus on designing provably robust aggregation mechanisms that can maintain model integrity even when over 30% of participating clients behave maliciously—a critical threshold for resilience in untrusted environments [

223]. Furthermore, adopting adversarial co-training paradigms, where defensive strategies evolve in tandem with adaptive attack behaviors within a game-theoretic framework, offers a promising pathway to preemptively mitigate sophisticated threat patterns. Equally important is the advancement of differential privacy techniques that are not only mathematically rigorous but also context-aware—specifically tailored to the spatiotemporal dependencies and graph-structured data inherent in energy systems—to ensure both privacy protection and task relevance in federated Power CPS applications.

7.2. Human-Centered Trust and Explainability

Building trust in federated learning systems for Power CPSs extends beyond technical robustness—it critically depends on human interpretability and operational alignment. One major challenge lies in the inherent opacity of black-box FL models, particularly those trained across decentralized and non-transparent participants, which diminishes operator confidence and limits practical deployment in safety-critical environments. Moreover, discrepancies between model-generated recommendations and human expert judgments can lead to decision conflicts, especially in protection systems or emergency control scenarios where accountability and real-time responsiveness are essential. Compounding these issues is the absence of standardized trust metrics tailored to the unique demands of power grid operations, making it difficult to quantify or benchmark the trustworthiness of FL deployments across heterogeneous stakeholders [

224].

To address these limitations, future research should focus on designing human-in-the-loop federated learning pipelines that integrate visual analytics, interactive model exploration, and operator override mechanisms, thereby embedding human judgment into the FL decision-making loop. Establishing formalized trust scoring systems—grounded in explainability, calibration accuracy, update integrity, and the degree of user control—will also be essential for quantifying and communicating the trustworthiness of FL models in operational contexts. In parallel, advancing sociotechnical interface research is needed to bridge the gap between human cognitive models and AI-driven reasoning, ensuring that FL systems not only perform accurately but also align with the expectations, workflows, and mental models of power system operators [

225].

7.3. Scalable System Integration and Digital Twin Coupling

Despite its promise, the large-scale deployment of federated learning in Power CPS is constrained by several integration challenges. First, embedding FL capabilities into edge devices—such as remote sensors, substations, and DER controllers—remains difficult due to limited computational resources, energy constraints, and intermittent connectivity, all of which undermine training stability and model synchronization. Second, the absence of standardized middleware for orchestrating FL workflows across heterogeneous infrastructures—including SCADA systems, Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI), and Distributed Energy Resource Management Systems (DERMS)—creates interoperability bottlenecks and limits scalability. Finally, validating FL models under realistic operating conditions is hampered by the persistent sim-to-real gap and the lack of co-simulation environments that can replicate the complex dynamics of physical power systems in conjunction with federated AI behavior [

226].

To overcome these barriers, future research should prioritize the development of energy-efficient federated learning protocols tailored to edge environments—leveraging techniques such as quantized model updates, asynchronous training, and sparse representations to reduce computational and communication overhead. In parallel, the creation of digital twin–augmented FL platforms will be vital for enabling closed-loop validation, “what-if” scenario analysis, and dynamic co-simulation across both cyber and physical layers of power systems. Furthermore, advancing FL-as-a-service infrastructures that support cross-vendor compatibility and modular integration with existing utility platforms will accelerate scalable adoption and facilitate seamless orchestration of federated intelligence across diverse energy assets and stakeholders [

227].

7.4. Policy, Regulation, and Multi-Stakeholder Governance

The deployment of federated learning in Power CPSs also confronts significant governance and regulatory challenges that go beyond technical implementation. Current cybersecurity and data protection frameworks—such as NERC CIP in North America and GDPR in Europe—provide limited guidance on the roles, responsibilities, and liabilities associated with decentralized AI systems, leaving critical gaps in compliance and risk attribution. Moreover, trust asymmetry among stakeholders—particularly between private technology vendors, public utilities, and regulatory bodies—undermines collaborative data federation efforts, often stalling progress due to concerns over data misuse, competitive exposure, or unclear governance authority. Compounding these issues is the lack of well-defined auditing and accountability mechanisms for FL-driven decisions, especially in high-stakes scenarios such as system blackouts or operational misjudgments, where tracing causality across distributed and opaque model updates remains a major hurdle [

228].

Addressing these governance challenges requires the establishment of auditable federated learning compliance frameworks that align not only with existing cybersecurity and data protection regulations but also with emerging energy justice principles, ensuring equitable access, transparency, and accountability. Promoting multi-tenant governance architectures—with clearly defined participation rules, traceable data provenance, and predefined fallback mechanisms—will be essential to enable trustworthy collaboration across utilities, vendors, regulators, and consumers. Additionally, fostering international cooperation through the development of cross-border federated testbeds and standardized trust certification schemes can help harmonize regulatory approaches, support interoperability, and accelerate the global adoption of trustworthy FL in critical energy infrastructures [

229,

230].

7.5. Summary Table: Key Gaps and Proposed Directions

To outline the current limitations and research frontiers in deploying TFL in real-world power systems, Table 7 summarizes key challenge categories, existing gaps, and proposed research directions to advance the field.

Table 7.

Open Challenges and Future Directions for TFL in Power CPSs.

Table 7.

Open Challenges and Future Directions for TFL in Power CPSs.

| Category |

Key Gaps |

Proposed Directions |

| Adversarial Robustness |

Lack of provable defense against poisoning and inference attacks |

Game-theoretic defenses, resilient aggregation, and contextual DP |

| Human-Centric Trust |

Poor explainability and operator alignment |

Visualized FL interfaces, trust metrics, and override mechanisms |

| System Integration |

Sim-to-real gap; constrained devices; lack of orchestration tools |

Digital twin–based validation, FL-as-a-service platforms, efficient edge protocols |

| Governance and Policy |

Ambiguous compliance rules; stakeholder mistrust; no audit trail |

Trust governance frameworks, multi-tenant traceability, cross-border standardization |

8. Conclusion

This review provides a holistic framework for federated learning (FL) in power cyber-physical systems, emphasizing trust dimensions of security, resilience, and explainability. Unlike prior surveys focused mainly on privacy or generic FL, it systematically maps threats to defenses, links architectures to trust features, and contextualizes them in real-world power system applications.

For researchers, the review highlights the need for hybrid approaches that combine robust aggregation, zero-trust validation, digital twin verification, and human-in-the-loop calibration. For practitioners, it underscores the trade-offs among accuracy, latency, and robustness in applications such as intrusion detection, EV coordination, and microgrid optimization. For policymakers, it calls for governance frameworks and auditing standards to guide responsible adoption. Trustworthy FL must evolve into adaptive frameworks that withstand adversarial dynamics, integrate heterogeneous resources, and align with regulatory and ethical principles. Positioned this way, FL becomes not just an algorithmic tool but a cornerstone for secure, resilient, and explainable intelligence in next-generation power systems. These contributions—multi-dimensional trust framework, architecture–trust–application mapping, and threat–defense–gap synthesis—jointly provide a roadmap for advancing trustworthy FL in Power CPS.

References

- Tariq, A.; Serhani, M.A.; Sallabi, F.; et al. Trustworthy federated learning: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.11537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, D.; Luo, J.; et al. A survey of trustworthy federated learning: Issues, solutions, and challenges. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 15, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.M.S.; Celdrán, A.H.; Xie, N.; et al. Federatedtrust: A solution for trustworthy federated learning. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 152, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, R.; Yu, H.; Faltings, B.; et al. Trustworthy Federated Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; et al. Trustworthy federated learning: privacy, security, and beyond. Knowledge and Information Systems 2025, 67, 2321–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, J.; et al. Physical informed-inspired deep reinforcement learning based bi-level programming for microgrid scheduling. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2025, 61, 1488–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; et al. Collaborative optimization of multi-microgrids system with shared energy storage based on multi-agent stochastic game and reinforcement learning. Energy 2023, 280, 128182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Yang, Z.; et al. Coordinating flexible demand response and renewable uncertainties for scheduling of community integrated energy systems with an electric vehicle charging station: A bi-level approach. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2021, 12, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Probabilistic charging power forecast of EVCS: Reinforcement learning assisted deep learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2022, 8, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Consul, P.; Jabbari, A.; et al. Asynchronous Federated Learning Based Energy Scheduling for Microgrid-Enabled MEC Network. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, V.; Sampath, L.P.M.I.; Singh, S.; et al. Blockchain-based decentralized frequency control of microgrids using federated learning fractional-order recurrent neural network. IEEE transactions on smart grid 2023, 15, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, S.; et al. Federated multiagent deep reinforcement learning approach via physics-informed reward for multimicrogrid energy management. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 35, 5902–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wu, Y.; Yesha, Y. Decentralized condition monitoring for distributed wind systems: A federated learning-based approach to enhance SCADA data privacy[C]//Energy Sustainability. American Society of Mechanical Engineers 2024, 87899: V001T01A010.

- Shang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; et al. Explainable spatiotemporal multi-task learning for electric vehicle charging demand prediction. Applied Energy 2025, 384, 125460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, Y.; et al. Safe-AutoSAC: AutoML-enhanced safe deep reinforcement learning for integrated energy system scheduling with multi-channel informer forecasting and electric vehicle demand response. Applied Energy 2025, 399, 126468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Trustworthy federated learning against malicious attacks in web 3.0. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2024, 11, 3969–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbi, O.; Arisdakessian, S.; Guizani, M.; et al. Enhancing mutual trustworthiness in federated learning for data-rich smart cities. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barroso, N.; García-Márquez, M.; Luzón, M.; et al. Challenges of Trustworthy Federated Learning: What's Done, Current Trends and Remaining Work. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.15796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Fang, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. FedCov: enhanced trustworthy federated learning for machine RUL prediction with continuous-to-discrete conversion. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, X.; Yu, H.; et al. Fedprok: Trustworthy federated class-incremental learning via prototypical feature knowledge transfer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024; pp. 4205–4214. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.M.; Xiang, Y.; Uddin, M.P.; et al. Trustworthy and fair federated learning via reputation-based consensus and adaptive incentives. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Jin, J.; et al. Secure federated learning for cloud-fog automation: Vulnerabilities, challenges, solutions, and future directions. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2025, 21, 3528–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jin, Y.; Yan, Y.; et al. FL-OTCSEnc: Towards secure federated learning with deep compressed sensing. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 291, 111534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Oh, K.; Lee, Y.; et al. Overview of fair federated learning for fairness and privacy preservation. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 128568. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, J.; et al. Distributed adaptive formation tracking control of mobile robots with event-triggered communication and denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2022, 70, 4077–4087. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Qu, Z.; et al. Method for Extracting Patterns of Coordinated Network Attacks on Electric Power CPS Based on Temporal–Topological Correlation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 57260–57272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Dong, C.; et al. Feddrl: Trustworthy federated learning model fusion method based on staged reinforcement learning. Computing and Informatics 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Liang, J. Security control of multiagent systems under denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2020, 52, 4323–4333. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, X.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Review of active defense methods against power cps false data injection attacks from the multiple spatiotemporal perspective. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 11235–11248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, M.; Rao, V. Fusion of multirate measurements for nonlinear dynamic state estimation of the power systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2017, 10, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; et al. PMU measurements-based short-term voltage stability assessment of power systems via deep transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Chung, C.Y.; Kamwa, I. A fast state estimator for systems including limited number of PMUs. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 4329–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, M.A.P.; Karna, N.B.A.; Alief, R.N.; et al. PureFed: An Efficient Collaborative and Trustworthy Federated Learning Framework Based on Blockchain Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 82413–82426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Qu, N.; et al. Survivability Evaluation Method for Cascading Failure of Electric Cyber Physical System Considering Load Optimal Allocation. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2019, 2019, 2817586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daole, M.; Ducange, P.; Marcelloni, F.; et al. Trustworthy AI in heterogeneous settings: federated learning of explainable classifiers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE); IEEE, 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Celdran, A.H.; Feng, C.; Sanchez, P.M.S.; et al. Assessing the sustainability and trustworthiness of federated learning models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.20435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, M.K.; Pathirana, P.N.; Wijayasundara, M.; et al. Federated learning for cyber physical systems: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2025. [Google Scholar]

- War, M.R.; Singh, Y.; Sheikh, Z.A.; et al. Review on the Use of Federated Learning Models for the Security of Cyber-Physical Systems. Scalable Computing: Practice and Experience 2025, 26, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; et al. A multi-objective optimal power flow approach considering economy and environmental factors for hybrid AC/DC grids incorporating VSC-HVDC. Power System Technology 2016, 40, 2661–2667. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Ding, H.; Zhao, S.; et al. Practical and robust federated learning with highly scalable regression training. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 35, 13801–13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.; Budhiraja, I.; Chaudhary, R.; et al. FLBCPS: Federated learning based secured computation offloading in blockchain-assisted cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/ACM 15th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC); IEEE, 2022; pp. 412–417. [Google Scholar]

- Pene, P.; Musa, A.A.; Musa, U.; et al. Edge intelligence in smart energy CPS. In Edge Intelligence in Cyber-Physical Systems; Academic Press, 2025; pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- Difrina, S.; Ramkumar, M.P.; Selvan, G.S.R.E. Trust Based Federated Learning for Privacy-preserving in Connected Smart Communities. In Proceedings of the 2025 Second International Conference on Cognitive Robotics and Intelligent Systems (ICC-ROBINS); IEEE, 2025; pp. 409–418. [Google Scholar]