Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

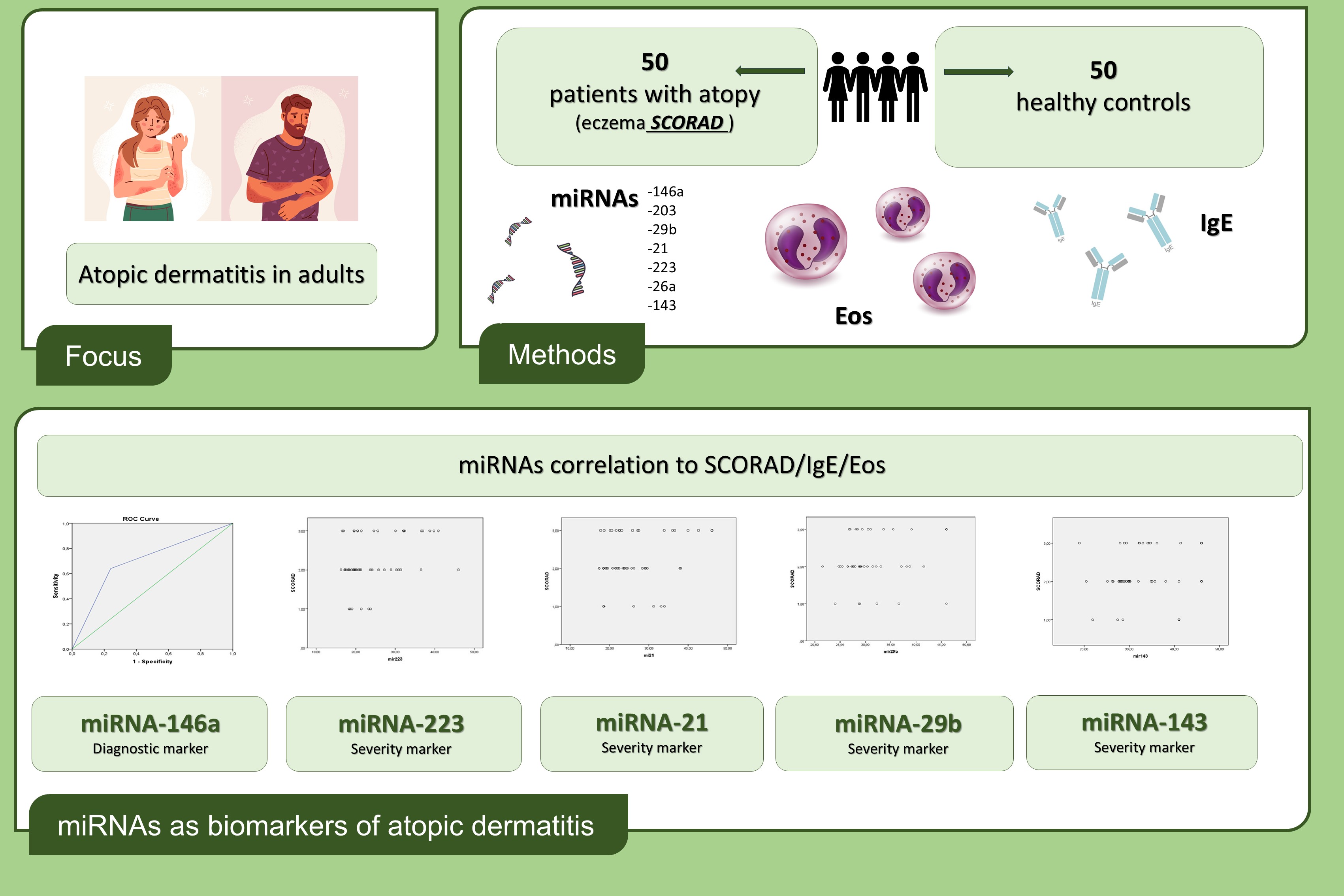

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

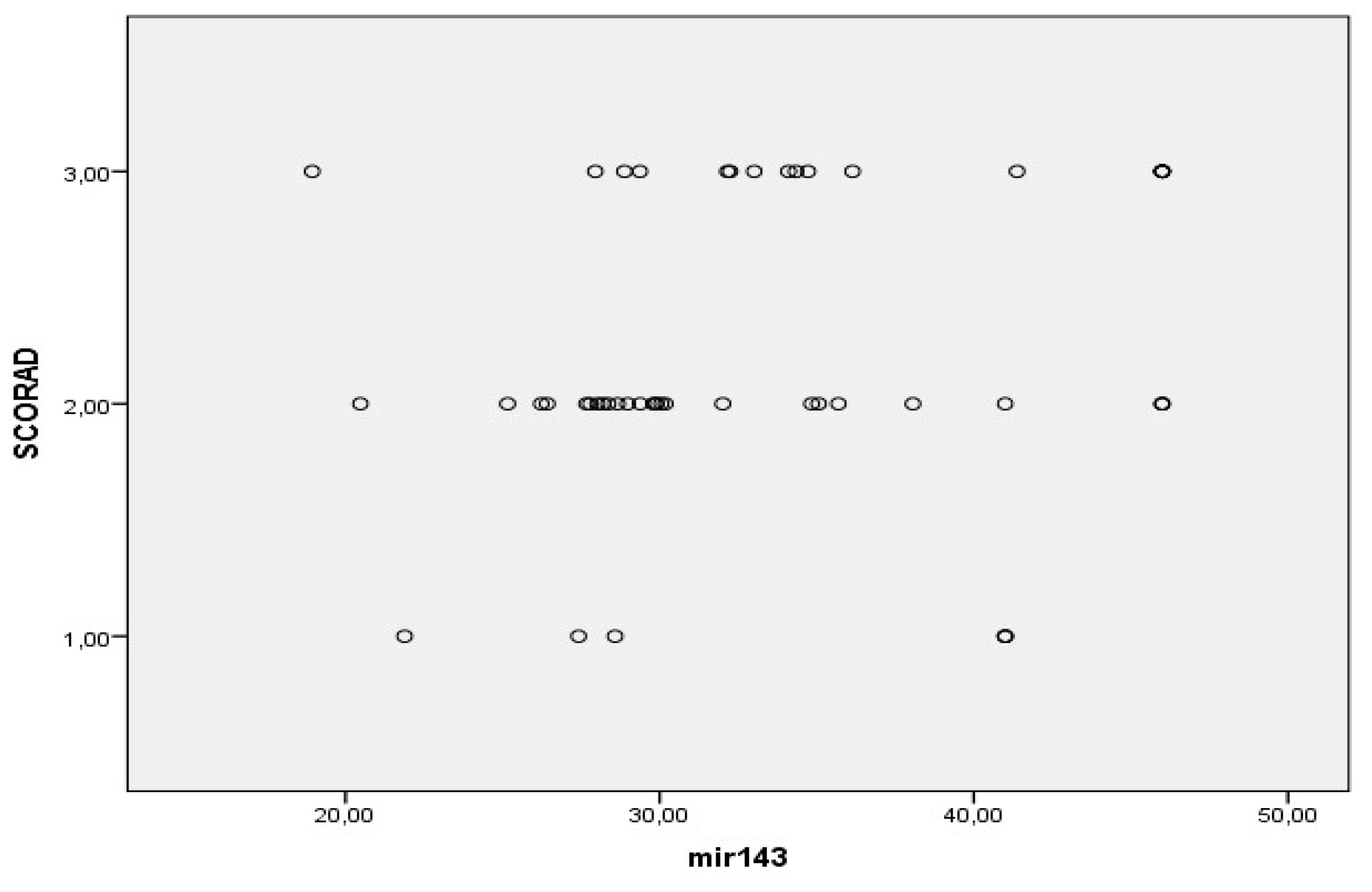

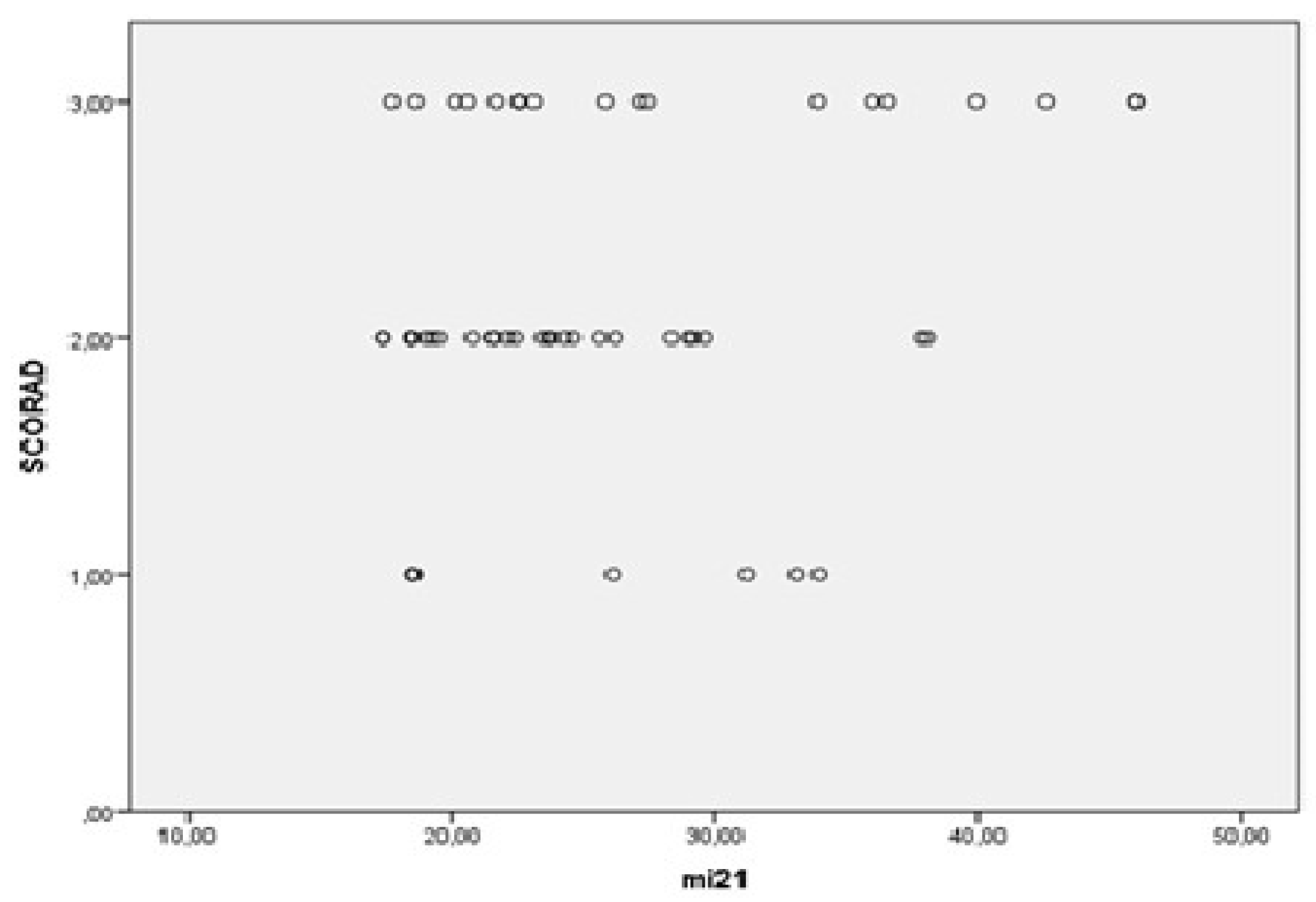

3. Results

3.1. Patient Dataset

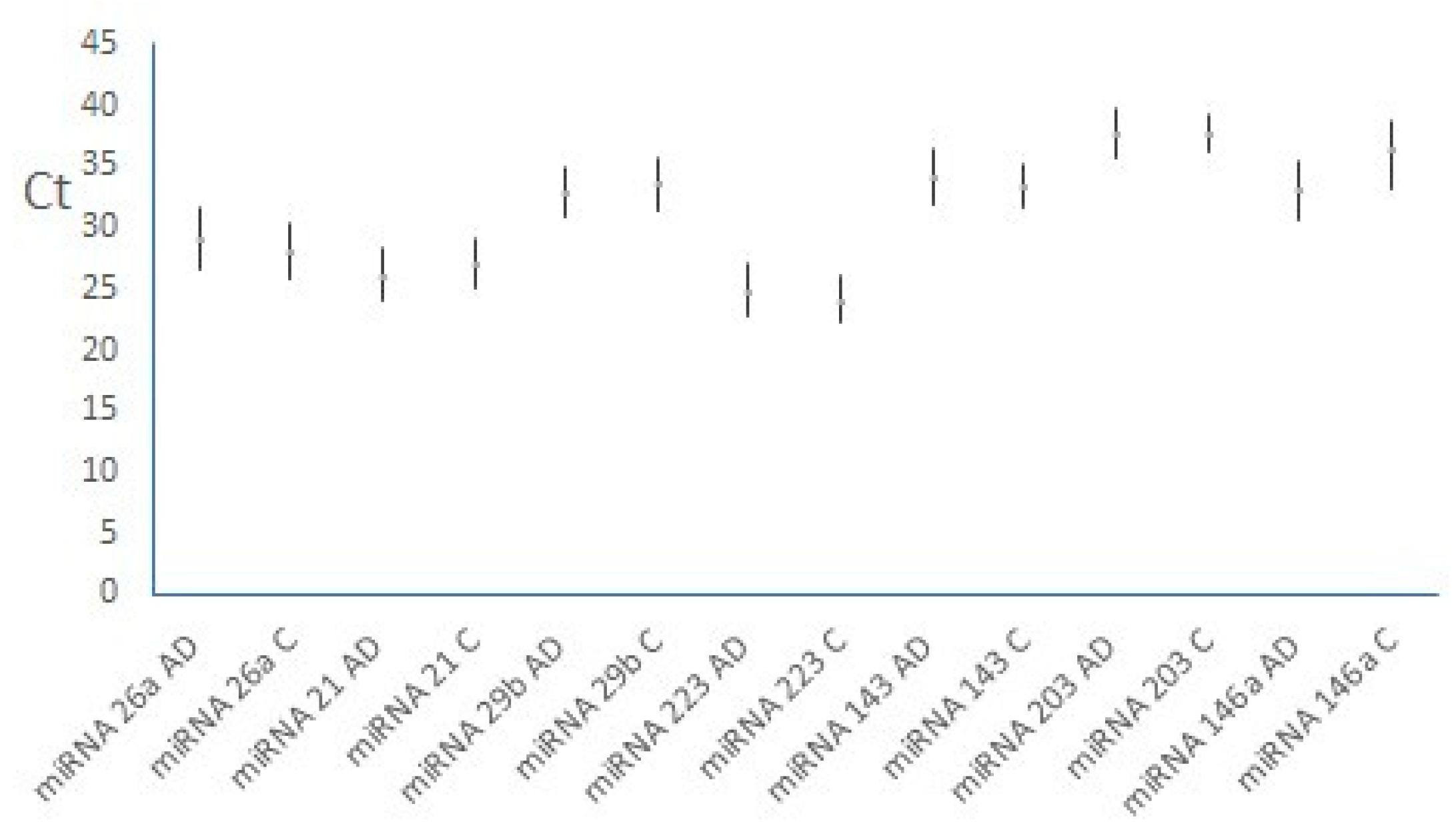

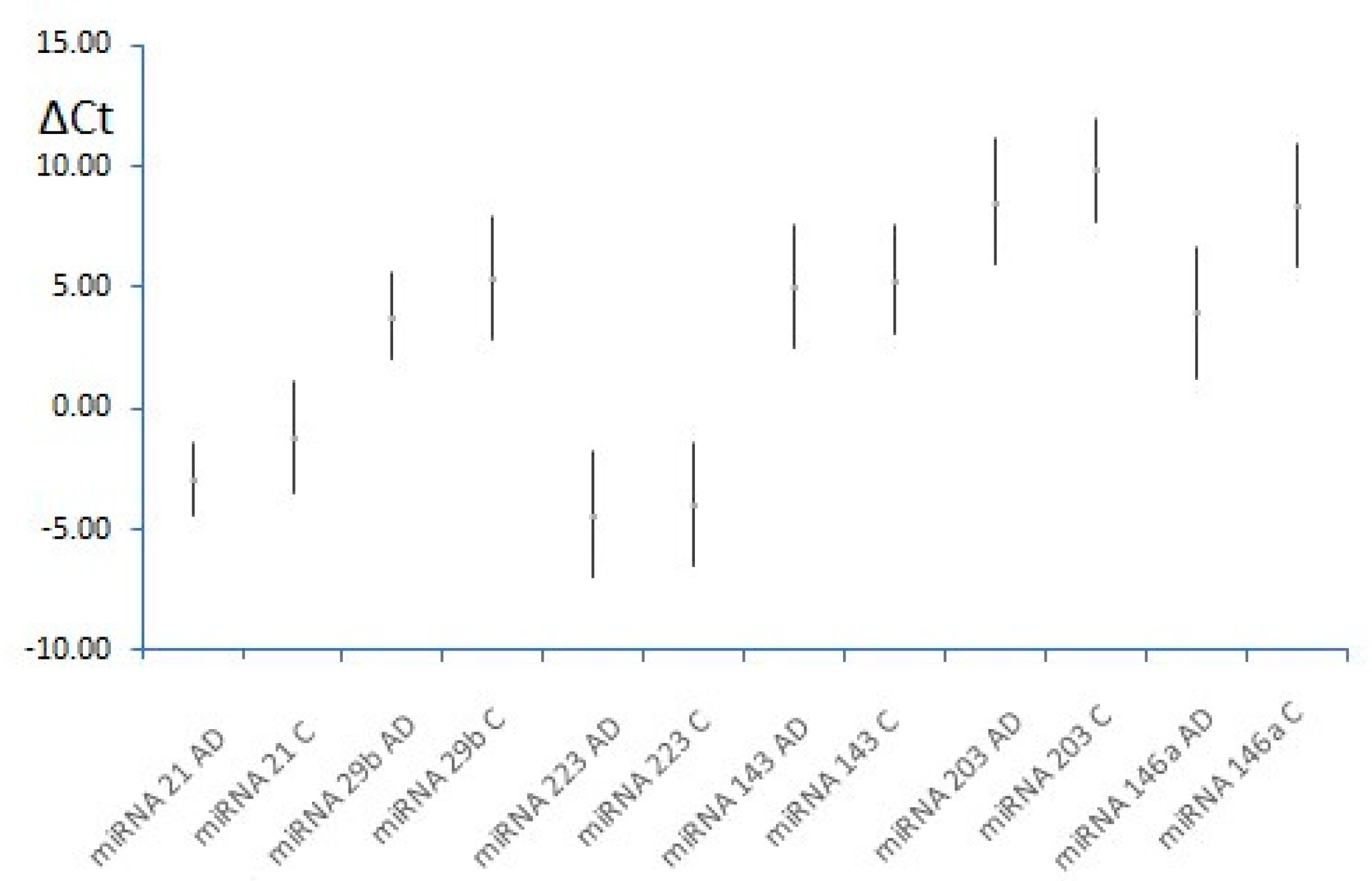

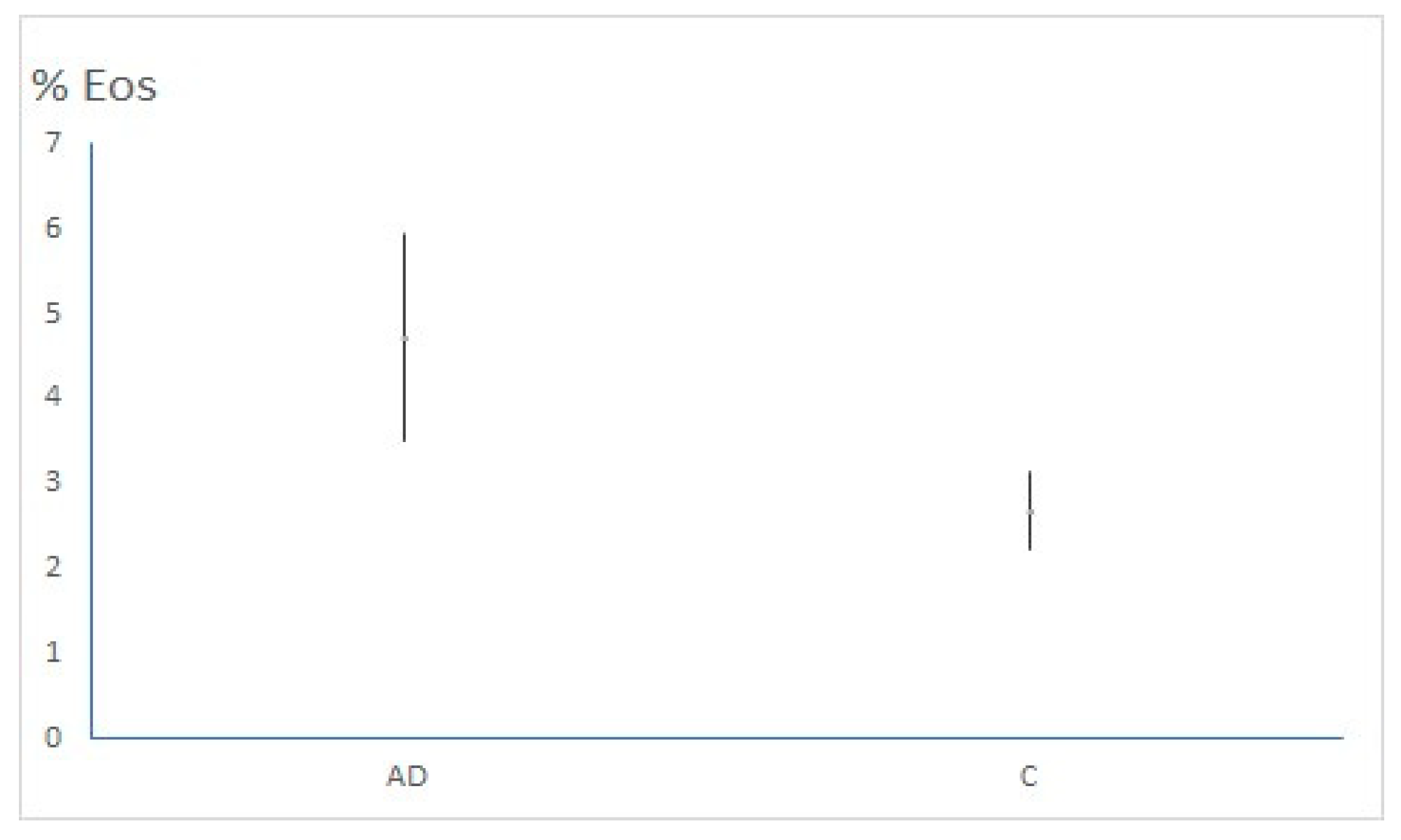

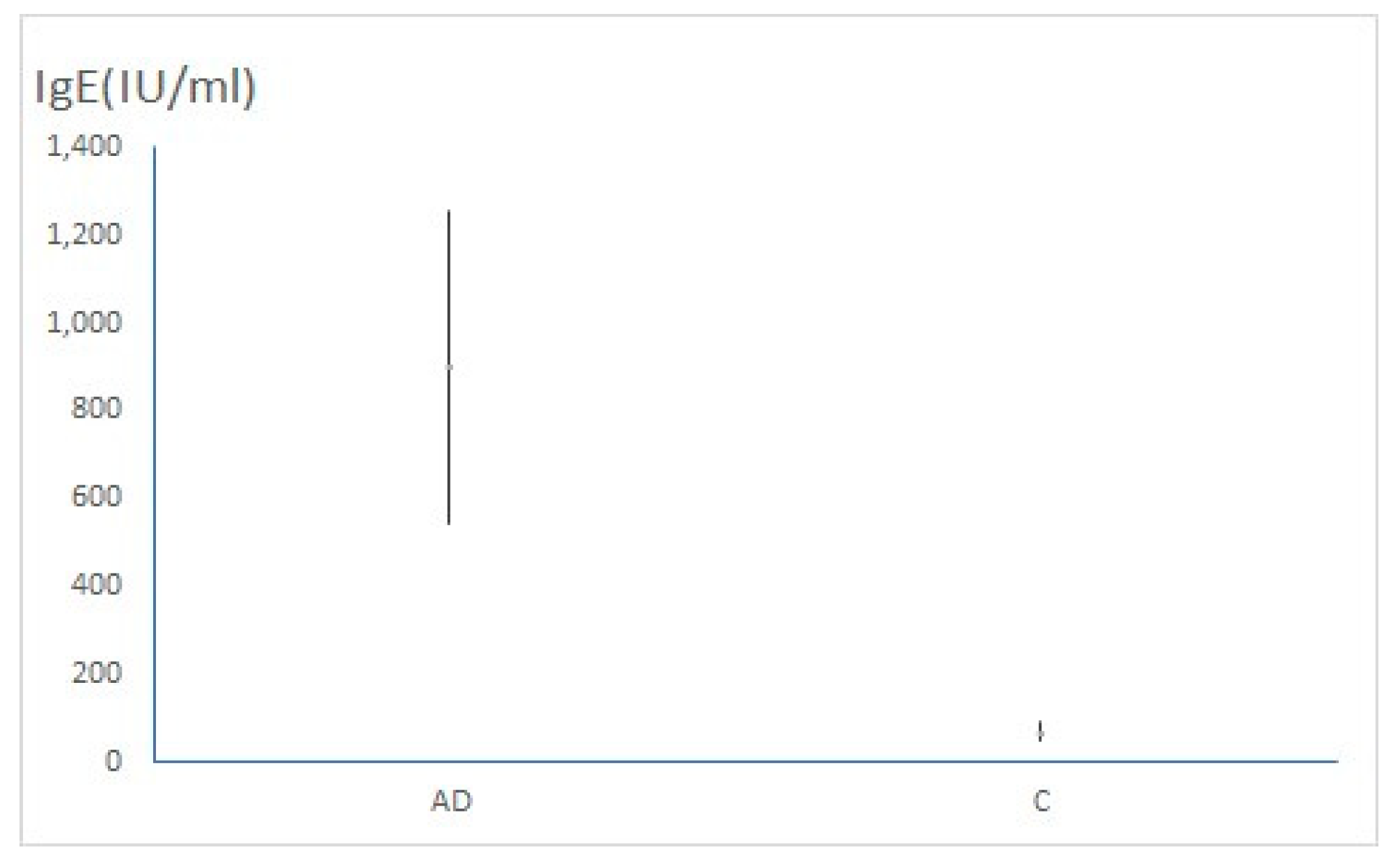

3.2. MiRNAs, Serum IgE Levels and Eosinophils in the Experimental - AD and Control Group – C

4. Discussion

4.1. Atopic Dermatitis

4.3. Therapeutic Potential of miRNAs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Specjalski K, Jassem E. MicroRNAs: Potential Biomarkers and Targets of Therapy in Allergic Diseases? Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2019 Aug;67(4):213-23. Epub 2019 May 28.

- Lugović-Mihić L, Meštrović-Štefekov J, Potočnjak I, Cindrić T, Ilić I, Lovrić I, et al. Atopic Dermatitis: Disease Features, Therapeutic Options, and a Multidisciplinary Approach. Life. 2023; 13(6):1419. [CrossRef]

- Lobefaro F, Gualdi G, Di Nuzzo S, Amerio P. Atopic Dermatitis: Clinical Aspects and Unmet Needs. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(11):2927. [CrossRef]

- Plewig G, French L, Ruzicka T, Kaufmann R, Hertl M, editors. Braun-Falcos Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2022.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, editors. Dermatology. 4thed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2018.

- Raimondo A, Lembo S. Atopic Dermatitis: Epidemiology and Clinical Phenotypes. Dermatol Pract Concept [Internet]. 2021 Oct. 29 [cited 2025 Mar. 17];:e2021146. Available from: https://dpcj.org/index.php/dpc/article/view/dermatol-pract-concept-articleid-dp1104a146.

- Thyssen JP, Halling AS, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI. Comorbidities of atopic dermatitis-what does the evidence say? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 May;151(5):1155-1162. Epub 2023 Jan 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidner J, Bartel S, Kılıç A, Zissler UM, Renz H, Schwarze J, et al. Spotlight on microRNAs in allergy and asthma. Allergy. 2021 Jun;76(6):1661-78. Epub 2020 Nov 20.

- Mrkić Kobal I, Plavec D, Vlašić Lončarić Ž, Jerković I, Turkalj M. Atopic March or Atopic Multimorbidity-Overview of Current Research. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 Dec 22;60(1):21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tham EH, Leung DY. Mechanisms by Which Atopic Dermatitis Predisposes to Food Allergy and the Atopic March. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2019 Jan;11(1):4-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yaneva M, Darlenski R. The link between atopic dermatitis and asthma- immunological imbalance and beyond. Asthma Res Pract. 2021 Dec 15;7(1):16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Las Vecillas L, Quirce S. The Multiple Trajectories of the Allergic March. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2024 Apr 12;34(2):75-84. Epub 2023 Dec 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin L, Leung DY. Genetic and epigenetic studies of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016 Oct 19;12:52. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hernández-Rodríguez RT, Amezcua-Guerra LM. The potential role of microRNAs as biomarkers in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020 Nov;24(22):11804-11809. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao L, Chau C, Bao J, Tsoukas MM, Chan LS. IL-4 dysregulates microRNAs involved in inflammation, angiogenesis and apoptosis in epidermal keratinocytes. Microbiol Immunol. 2018 Nov;62(11):732-736. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadali Z. Th9 Cells as a New Player in Inflammatory Skin Disorders. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019 Apr 1;18(2):120-130. PMID: 31066248.

- Pescitelli L, Rosi E, Ricceri F, Pimpinelli N, Prignano F. Novel Therapeutic Approaches and Targets for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2021;22(1):73-84. [CrossRef]

- Khosrojerdi M, Azad FJ, Yadegari Y, Ahanchian H, Azimian A. The role of microRNAs in atopic dermatitis. Noncoding RNA Res. 2024 May 28;9(4):1033-39.

- Tsuji G, Yamamura K, Kawamura K, Kido-Nakahara M, Ito T, Nakahara T. Novel Therapeutic Targets for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Biomedicines. 2023 Apr 27;11(5):1303. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gatmaitan JG, Lee JH. Challenges and Future Trends in Atopic Dermatitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(14):11380. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka A, Nomura T, Rerknimitr P, Seidel JA, Honda T, Kabashima K. The interplay between genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Rev. 2017 Jul;278(1):246-262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng L, Li M, Gao Z, Ren H, Chen J, Liu X, et al. Possible role of hsa-miR-194-5p, via regulation of HS3ST2, in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis in children. Eur J Dermatol. 2019 Dec 1;29(6):603-13.

- Schmidt AD, de Guzman Strong C. Current understanding of epigenetics in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2021 Aug;30(8):1150-5.

- Lee YS, Han SB, Ham HJ, Park JH, Lee JS, Hwang DY, et al. IL-32γ suppressed atopic dermatitis through inhibition of miR-205 expression via inactivation of nuclear factor-kappa B. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Jul;146(1):156-68. Epub 2020 Jan 10.

- Rebane A, Runnel T, Aab A, Maslovskaja J, Rückert B, Zimmermann M, et al. MicroRNA-146a alleviates chronic skin inflammation in atopic dermatitis through suppression of innate immune responses in keratinocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Oct;134(4):836-47.e11. Epub 2014 Jul 2.

- Yan F, Meng W, Ye S, Zhang X, Mo X, Liu J, et al. MicroRNA 146a as a potential regulator involved in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Mol Med Rep. 2019 Nov;20(5):4645-53. Epub 2019 Sep 20.

- Gu C, Li Y, Wu J, Xu J. IFN-γ-induced microRNA-29b up-regulation contributes tokeratinocyte apoptosis in atopic dermatitis through inhibiting Bcl2L2. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017 Sep 1;10(9):10117-26.

- Sonkoly E, Janson P, Majuri ML, Savinko T, Fyhrquist N, Eidsmo L, et al. MiR-155 is overexpressed in patients with atopic dermatitis and modulates T-cell proliferative responses by targeting cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Sep;126(3):581-9.e1-20. Epub 2010 Jul 31.

- Bergallo M, Accorinti M, Galliano I, Coppo P, Montanari P, Quaglino P, et al. Expression of miRNA 155, FOXP3 and ROR gamma, in children with moderate and severe atopic dermatitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Apr;155(2):168-72.

- Ma L, Xue HB, Wang F, Shu CM, Zhang JH. MicroRNA-155 may be involved in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis by modulating the differentiation and function of T helper type 17 (Th17) cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015 Jul;181(1):142-9. Epub 2015 May 25.

- Chen XF, Zhang LJ, Zhang J, Dou X, Shao Y, Jia XJ, et al. MiR-151a is involved in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis by regulating interleukin-12 receptor β2. Exp Dermatol. 2018 Apr;27(4):427-32. Epub 2017 Apr 11.

- Acevedo N, Benfeitas R, Katayama S, Bruhn S, Andersson A, Wikberg G, et al. Epigenetic alterations in skin homing CD4+CLA+ T cells of atopic dermatitis patients. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 22;10(1):18020. [CrossRef]

- Moltrasio C, Romagnuolo M, Marzano AV. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Epidermal Differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 28;23(9):4874. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Livshits G, Kalinkovich A. Resolution of Chronic Inflammation, Restoration of Epigenetic Disturbances and Correction of Dysbiosis as an Adjunctive Approach to the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Cells. 2024 Nov 18;13(22):1899. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, AY. The Role of MicroRNAs in Epidermal Barrier. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Aug 12;21(16):5781. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang Z, Zeng B, Wang C, Wang H, Huang P, Pan Y. MicroRNA-124 alleviates chronic skin inflammation in atopic eczema via suppressing innate immune responses in keratinocytes. Cell Immunol. 2017 Sep;319:53-60. Epub 2017 Aug 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng YP, Nguyen GH, Jin HZ. MicroRNA-143 inhibits IL-13-induced dysregulation of the epidermal barrier-related proteins in skin keratinocytes via targeting to IL-13Rα1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016 May;416(1-2):63-70. Epub 2016 Apr 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Li XQ, Sahbaie P, Shi XY, Li WW, Liang DY, et al. miR-203 regulates nociceptive sensitization after incision by controlling phospholipase A2 activating protein expression. Anesthesiology. 2012 Sep;117(3):626-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng Q, Yao X, Fang S, Sun Y, Liu L, Li C, et al. Mast cell-mediated microRNA functioning in immune regulation and disease pathophysiology. Clin Exp Med. 2025 Jan 15;25(1):38. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Domingo S, Solé C, Moliné T, Ferrer B, Cortés-Hernández J. MicroRNAs in Several Cutaneous Autoimmune Diseases: Psoriasis, Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus and Atopic Dermatitis. Cells. 2020 Dec 10;9(12):2656.

- Yu X, Wang M, Li L, Zhang L, Chan MTV, Wu WKK. MicroRNAs in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. J Cell Mol Med. 2020 Jun;24(11):5966-72. Epub 2020 Apr 30.

- Rożalski M, Rudnicka L, Samochocki Z. MiRNA in atopic dermatitis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016 Jun;33(3):157-62. Epub 2016 Jun 17.

- Dopytalska K, Czaplicka A, Szymańska E, Walecka I. The Essential Role of microRNAs in Inflammatory and Autoimmune Skin Diseases-A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 23;24(11):9130.

- Brancaccio R, Murdaca G, Casella R, Loverre T, Bonzano L, Nettis E, et al. miRNAs' Cross-Involvement in Skin Allergies: A New Horizon for the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Therapy of Atopic Dermatitis, Allergic Contact Dermatitis and Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Biomedicines. 2023 Apr 24;11(5):1266.

- Dissanayake E, Inoue Y. MicroRNAs in Allergic Disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016 Sep;16(9):67. [CrossRef]

- Rebane A. microRNA and Allergy. In: Gaetano S, editor. microRNA: Medical Evidence: From Molecular Biology to Clinical Practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015.

- Rebane A, Akdis CA. MicroRNAs in allergy and asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014 Apr;14(4):424.

- Chen L, Zhong JL. MicroRNA and heme oxygenase-1 in allergic disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020 Mar;80:106132. Epub 2020 Jan 22.

- Lu TX, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018 Apr;141(4):1202-07. Epub 2017 Oct 23.

- Ruksha TG, Komina AV, Palkina NV. MicroRNA in skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;27(4):343-352. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannucci C, Casciaro M, Minciullo PL, Calapai G, Navarra M, Gangemi S. Involvement of microRNAs in skin disorders: A literature review. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017 Jan 1;38(1):9-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonkoly E, Wei T, Janson PC, Sääf A, Lundeberg L, Tengvall-Linder M, et al. MicroRNAs: novel regulators involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis? PLoS One. 2007 Jul 11;2(7):e610. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Løvendorf MB, Skov L. miRNAs in inflammatory skin diseases and their clinical implications. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015 Apr;11(4):467-77. Epub 2015 Feb 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker D, de Bruin-Weller M, Drylewicz J, van Wijk F, Thijs J. Biomarkers in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 May;151(5):1163-1168. Epub 2023 Feb 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastraftsi S, Vrioni G, Bakakis M, Nicolaidou E, Rigopoulos D, Stratigos AJ, et al. Atopic Dermatitis: Striving for Reliable Biomarkers. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 9;11(16):4639. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nousbeck J, McAleer MA, Hurault G, Kenny E, Harte K, Kezic S, et al. MicroRNA analysis of childhood atopic dermatitis reveals a role for miR-451a. Br J Dermatol. 2021 Mar;184(3):514-23. [CrossRef]

- Lv Y, Qi R, Xu J, Di Z, Zheng H, Huo W, et al. Profiling of serum and urinary microRNAs in children with atopic dermatitis. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 22;9(12):e115448. [CrossRef]

- Lu TX, Rothenberg ME. Diagnostic, functional, and therapeutic roles of microRNA in allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Jul;132(1):3-13; quiz 14. Epub 2013 Jun 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yasuike R, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Nakamura N, Masuda K, Katoh N. Plasma miR223 is a possible biomarker for diagnosing patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2021 Jan;70(1):153-155. Epub 2020 Sep 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdaca G, Tonacci A, Negrini S, Greco M, Borro M, Puppo F, et al. Effects of AntagomiRs on Different Lung Diseases in Human, Cellular, and Animal Models. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 13;20(16):3938. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang SC, Alalaiwe A, Lin ZC, Lin YC, Aljuffali IA, Fang JY. Anti-Inflammatory microRNAs for Treating Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Biomolecules. 2022 Aug 3;12(8):1072. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rullo VE, Segato A, Kirsh A, Sole D. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of two scoring systems. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2008 Jul-Aug;36(4):205-11.

- Ricci G, Dondi A, Patrizi A. Useful tools for the management of atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(5):287-300.

- Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186(1):23-31. [CrossRef]

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb;70(2):338-51. Epub 2013 Nov 27.

- Kortekaas Krohn I, Badloe FMS, Herrmann N, Maintz L, De Vriese S, Ring J, et al. Immunoglobulin E autoantibodies in atopic dermatitis associate with Type-2 comorbidities and the atopic march. Allergy. 2023 Dec;78(12):3178-92. Epub 2023 Jul 24.

- Vaneckova J, Bukač J. The severity of atopic dermatitis and the.

- relation to the level of total IgE, onset of atopic dermatitis and family history about atopy. Food Agric. Immunol. 2016 May; 27(5):1-8.

- Furue M, Chiba T, Tsuji G, Ulzii D, Kido-Nakahara M, Nakahara T, et al. Atopic dermatitis: immune deviation, barrier dysfunction, IgE autoreactivity and new therapies. Allergol Int. 2017 Jul;66(3):398-403. Epub 2017 Jan 2.

- Simon D, Braathen LR, Simon HU. Eosinophils and atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2004 Jun;59(6):561-70.

- Timis TL, Orasan RI. Understanding psoriasis: Role of miRNAs. Biomed Rep. 2018 Nov;9(5):367-374. Epub 2018 Sep 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hermann H, Runnel T, Aab A, Baurecht H, Rodriguez E, Magilnick N, et al. miR-146b Probably Assists miRNA-146a in the Suppression of Keratinocyte Proliferation and Inflammatory Responses in Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2017 Sep;137(9):1945-1954. Epub 2017 Jun 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guinea-Viniegra J, Jiménez M, Schonthaler HB, Navarro R, Delgado Y, Concha-Garzón MJ, et al. Targeting miR-21 to treat psoriasis. Sci Transl Med. 2014 Feb 26;6(225):225re1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichihara A, Wang Z, Jinnin M, Izuno Y, Shimozono N, Yamane K, et al. Upregulation of miR-18a-5p contributes to epidermal necrolysis in severe drug eruptions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Apr;133(4):1065-74. Epub 2013 Nov 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon W, Kim EJ, Park Y, Kim S, Park YK, Yoo Y. Bacterially Delivered miRNA-Mediated Toll-like Receptor 8 Gene Silencing for Combined Therapy in a Murine Model of Atopic Dermatitis: Therapeutic Effect of miRTLR8 in AD. Microorganisms. 2021 Aug 12;9(8):1715. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carreras-Badosa G, Runnel T, Plaas M, Kärner J, Rückert B, et al. microRNA-146a is linked to the production of IgE in mice but not in atopic dermatitis patients. Allergy. 2018 Dec;73(12):2400-3. Epub 2018 Aug 21.

- Li F, Huang Y, Huang YY, Kuang YS, Wei YJ, Xiang L, et al. MicroRNA-146a promotes IgE class switch in B cells via upregulating 14-3-3σ expression. Mol Immunol. 2017 Dec;92:180-189. Epub 2017 Nov 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava A, Nikamo P, Lohcharoenkal W, Li D, Meisgen F, Xu Landén N, et al. MicroRNA-146a suppresses IL-17-mediated skin inflammation and is genetically associated with psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 Feb;139(2):550-561. Epub 2016 Aug 24. [CrossRef]

- Gilyazova I, Asadullina D, Kagirova E, Sikka R, Mustafin A, Ivanova E, et al. MiRNA-146a-A Key Player in Immunity and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Aug 14;24(16):12767. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang Y, Yin X, Yi J, Peng X. MiR-146a overexpression effectively improves experimental allergic conjunctivitis through regulating CD4+CD25-T cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 Oct;94:937-943. Epub 2017 Aug 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou J, Lu Y, Wu W, Feng Y. HMSC-Derived Exosome Inhibited Th2 Cell Differentiation via Regulating miR-146a-5p/SERPINB2 Pathway. J Immunol Res. 2021 May 14;2021:6696525. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shefler I, Salamon P, Mekori YA. MicroRNA Involvement in Allergic and Non-Allergic Mast Cell Activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Apr 30;20(9):2145. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo X, Han M, Liu J, Wang Y, Luo X, Zheng J, et al. Epithelial cell-derived micro RNA-146a generates interleukin-10-producing monocytes to inhibit nasal allergy. Sci Rep. 2015 Nov 3;5:15937. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu J, Xu Z, Yu J, Zang X, Jiang S, Xu S, et al. MiR-146a-5p engineered hucMSC-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate Dermatophagoides farinae-induced allergic airway epithelial cell inflammation. Front Immunol. 2024 Sep 19;15:1443166. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bélanger É, Laprise C. Could the Epigenetics of Eosinophils in Asthma and Allergy Solve Parts of the Puzzle? Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug 19;22(16):8921. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rodrigo-Muñoz JM, Cañas JA, Sastre B, Rego N, Greif G, Rial M, et al. Asthma diagnosis using integrated analysis of eosinophil microRNAs. Allergy. 2019 Mar;74(3):507-517. Epub 2018 Oct 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger É, Madore AM, Boucher-Lafleur AM, Simon MM, Kwan T, Pastinen T, et al. Eosinophil microRNAs Play a Regulatory Role in Allergic Diseases Included in the Atopic March. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Nov 27;21(23):9011. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allantaz F, Cheng DT, Bergauer T, Ravindran P, Rossier MF, Ebeling M, et al. Expression profiling of human immune cell subsets identifies miRNA-mRNA regulatory relationships correlated with cell type specific expression. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29979. Epub 2012 Jan 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weidner J, Ekerljung L, Malmhäll C, Miron N, Rådinger M. Circulating microRNAs correlate to clinical parameters in individuals with allergic and non-allergic asthma. Respir Res. 2020 May 7;21(1):107. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu TX, Lim EJ, Besse JA, Itskovich S, Plassard AJ, Fulkerson PC, et al. MiR-223 deficiency increases eosinophil progenitor proliferation. J Immunol. 2013 Feb 15;190(4):1576-82. Epub 2013 Jan 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu TX, Lim EJ, Itskovich S, Besse JA, Plassard AJ, Mingler MK, et al. Targeted ablation of miR-21 decreases murine eosinophil progenitor cell growth. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59397. Epub 2013 Mar 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lyu B, Wei Z, Jiang L, Ma C, Yang G, Han S. MicroRNA-146a negatively regulates IL-33 in activated group 2 innate lymphoid cells by inhibiting IRAK1 and TRAF6. Genes Immun. 2020 Jan;21(1):37-44. Epub 2019 Aug 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang SB, Zhang HY, Wang C, He BX, Liu XQ, Meng XC, et al. Small extracellular vesicles derived from human mesenchymal stromal cells prevent group 2 innate lymphoid cell-dominant allergic airway inflammation through delivery of miR-146a-5p. J Extracell Vesicles. 2020 Feb 10;9(1):1723260. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang J, Cui Z, Liu L, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. MiR-146a mimic attenuates murine allergic rhinitis by downregulating TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway. Immunotherapy. 2019 Sep;11(13):1095-1105. Epub 2019 Jul 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li A, Li Y, Zhang X, Zhang C, Li T, Zhang J, et al. The human milk oligosaccharide 2'-fucosyllactose attenuates β-lactoglobulin-induced food allergy through the miR-146a-mediated toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway. J Dairy Sci. 2021 Oct;104(10):10473-10484. Epub 2021 Jul 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Lu X, Ma C, Ma L, Han S. Combination of TLR agonist and miR146a mimics attenuates ovalbumin-induced asthma. Mol Med. 2020 Jun 29;26(1):65. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun W, Sheng Y, Chen J, Xu D, Gu Y. Down-Regulation of miR-146a Expression Induces Allergic Conjunctivitis in Mice by Increasing TSLP Level. Med Sci Monit. 2015 Jul 11;21:2000-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guo H, Zhang Y, Liao Z, Zhan W, Wang Y, Peng Y, et al. MiR-146a upregulates FOXP3 and suppresses inflammation by targeting HIPK3/STAT3 in allergic conjunctivitis. Ann Transl Med. 2022 Mar;10(6):344. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kılıç A, Santolini M, Nakano T, Schiller M, Teranishi M, Gellert P, et al. A systems immunology approach identifies the collective impact of 5 miRs in Th2 inflammation. JCI Insight. 2018 Jun 7;3(11):e97503. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guidi R, Wedeles CJ, Wilson MS. ncRNAs in Type-2 Immunity. Noncoding RNA. 2020 Mar 6;6(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Panganiban RP, Wang Y, Howrylak J, Chinchilli VM, Craig TJ, August A, et al. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers in patients with allergic rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 May;137(5):1423-32. Epub 2016 Mar 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma R, Tiwari A, McGeachie MJ. Recent miRNA Research in Asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2022 Dec;22(12):231-258. Epub 2022 Dec 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hammad Mahmoud Hammad R, Hamed DHED, Eldosoky MAER, Ahmad AAES, Osman HM, Abd Elgalil HM, et al. Plasma microRNA-21, microRNA-146a and IL-13 expression in asthmatic children. Innate Immun. 2018 Apr;24(3):171-179. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo X, Hong H, Tang J, Wu X, Lin Z, Ma R, et al. Increased Expression of miR-146a in Children With Allergic Rhinitis After Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016 Mar;8(2):132-40. Epub 2015 Oct 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu TX, Sherrill JD, Wen T, Plassard AJ, Besse JA, Abonia JP, et al. MicroRNA signature in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, reversibility with glucocorticoids, and assessment as disease biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Apr;129(4):1064-75.e9. Epub 2012 Mar 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leal B, Carvalho C, Ferreira AM, Nogueira M, Brás S, Silva BM, et al. Serum Levels of miR-146a in Patients with Psoriasis. Mol Diagn Ther. 2021 Jul;25(4):475-485. Epub 2021 May 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarswamy R, Volkmann I, Thum T. Regulation and function of miRNA-21 in health and disease. RNA Biol. 2011 Sep-Oct;8(5):706-13. Epub 2011 Jul 7.

- Silvia Lima RQD, Vasconcelos CFM, Gomes JPA, Bezerra de Menezes EDS, de Oliveira Silva B, Montenegro C, et al. miRNA-21, an oncomiR that regulates cell proliferation, migration, invasion and therapy response in lung cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2024 Nov;263:155601. Epub 2024 Oct 3.

- Jayawardena E, Medzikovic L, Ruffenach G, Eghbali M. Role of miRNA-1 and miRNA-21 in Acute Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Their Potential as Therapeutic Strategy. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 28;23(3):1512.

- Lu TX, Munitz A, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA-21 is up-regulated in allergic airway inflammation and regulates IL-12p35 expression. J Immunol. 2009 Apr 15;182(8):4994-5002.

- Simpson MR, Brede G, Johansen J, Johnsen R, Storrø O, Sætrom P, et al. Human Breast Milk miRNA, Maternal Probiotic Supplementation and Atopic Dermatitis in Offspring. PLoS One. 2015 Dec 14;10(12):e0143496.

- Yu S, Zhang R, Zhu C, Cheng J, Wang H, Wu J. MicroRNA-143 downregulates interleukin-13 receptor alpha1 in human mast cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2013 Aug 19;14(8):16958-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia QN, Zeng YP. Rapamycin blocks the IL-13-induced deficiency of Epidermal Barrier Related Proteins via upregulation of miR-143 in HaCaT Keratinocytes. Int J Med Sci. 2020 Jul 25;17(14):2087-94.

- Zu Y, Chen XF, Li Q, Zhang ST. CYT387, a Novel JAK2 Inhibitor, Suppresses IL-13-Induced Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction Via miR-143 Targeting IL-13Rα1 and STAT3. Biochem Genet. 2021 Apr;59(2):531-46. Epub 2020 Nov 15.

- Løvendorf MB, Zibert JR, Gyldenløve M, Røpke MA, Skov L. MicroRNA-223 and miR-143 are important systemic biomarkers for disease activity in psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2014 Aug;75(2):133-9. Epub 2014 May 21.

- Yasuike R, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Nakamura N, Masuda K, Katoh N. Plasma miR223 is a possible biomarker for diagnosing patients with severe atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2021 Jan;70(1):153-5. Epub 2020 Sep 1.

- Jia HZ, Liu SL, Zou YF, Chen XF, Yu L, Wan J, et al. MicroRNA-223 is involved in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis by affecting histamine-N-methyltransferase. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2018 Feb 28;64(3):103-7.

- Ralfkiaer U, Lindahl LM, Litman T, Gjerdrum LM, Ahler CB, Gniadecki R, et al. MicroRNA expression in early mycosis fungoides is distinctly different from atopic dermatitis and advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Anticancer Res. 2014 Dec;34(12):7207-17. Erratum in: Anticancer Res. 2015 Feb;35(2):1219.

- Li C, Li Y, Lu Y, Niu Z, Zhao H, Peng Y, et al. miR-26 family and its target genes in tumorigenesis and development. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021 Jan;157:103124. Epub 2020 Oct 20.

- Dandare A, Khan MJ, Naeem A, Liaquat A. Clinical relevance of circulating non-coding RNAs in metabolic diseases: Emphasis on obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome. Genes Dis. 2022 Jun 3;10(6):2393-413.

- Kärner J, Wawrzyniak M, Tankov S, Runnel T, Aints A, Kisand K, et al. Increased microRNA-323-3p in IL-22/IL-17-producing T cells and asthma: a role in the regulation of the TGF-β pathway and IL-22 production. Allergy. 2017 Jan;72(1):55-65. Epub 2016 Apr 29.

| Variable | AD patients | Healthy controls | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 50 | 50 | / |

| Gender Male (n, (%)) Female (n, (%)) |

14 (28) 36 (72) |

15 (30) 35 (70) |

0.83 |

| Age, years (average ± 95%CI) | 32.62 (29.22 – 36.02) | 36.4 (33.39 – 39.41) | 0.09 |

| Early onset in childhood (n, (%)) | 8 (16) | / | / |

| Disease duration (year) (average ±95%CI) | 7.22 (4.34 - 10.09) | / | / |

| < 1y (n, (%)) | 13 (26) | / | / |

| > 1-5y (n, (%)) | 20 (40) | / | / |

| > 5-10y (n, (%)) | 5 (10) | / | / |

| > 10y (n, (%)) | 12 (24) | / | / |

| SCORAD 0-24 Mild AD (n, (%)) 25-50 Moderate AD (n, (%)) 51-103 Severe AD (n, (%)) |

6 (12) 26 (52) 18 (36) |

/ / / |

/ |

| Total IgE (IU/ml) (average ± 95%CI) | 899.8 (544.45 – 1255.15) | 69.76 (47.53 – 91.99) | p< 0.001 |

| Eos (%) (average ± 95%CI) | 4.73 (3.51 – 5.96) | 2.68 (2.22 – 3.14) | p= 0.002 |

| Comorbidities AR, yes (n, (%)) As, yes (n, (%)) FA, yes (n, (%)) |

27 (54) 7 (14) 5 (1) |

/ / / |

/ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).