Key Summary Points

Why carry out this study?

Severe alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic inflammatory condition with limited non-invasive biomarkers to aid in diagnosis or monitoring.

Current clinical classification does not reliably capture disease mechanisms or therapeutic targets.

Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) may reflect underlying immune and tissue-specific dysregulation in AA and distinguish it from other inflammatory skin diseases.

What did the study ask?

Can specific plasma miRNA signatures differentiate severe AA from atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and vitiligo?

Do these signatures provide insight into underlying disease pathways and potential therapeutic opportunities?

What was learned from the study?

A panel of ten downregulated plasma miRNAs was consistently identified and validated in patients with severe AA.

These miRNA signatures distinguished AA from other inflammatory dermatoses with high accuracy and were enriched in immune-regulatory and epithelial pathways.

Candidate drugs targeting miRNA-regulated pathways were identified, suggesting possible avenues for therapeutic repurposing.

The study supports the diagnostic and mechanistic value of circulating miRNAs in AA, while highlighting the need for future longitudinal and functional validation.

Plain Language Summary

Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disease that causes hair loss, but its biological mechanisms are not fully understood. In this study, we examined small molecules in the blood called microRNAs, which help regulate gene activity, to explore their role in alopecia areata. We analyzed blood samples from people with severe and mild alopecia areata, as well as from individuals with other immune-related skin conditions such as vitiligo, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis, along with healthy individuals. We found that a group of microRNAs was consistently reduced in alopecia areata and could help distinguish it from other skin diseases. These molecules were linked to key immune and tissue-related biological processes, including pathways that are already being targeted by some existing or experimental drugs. Our findings suggest that measuring microRNAs in blood could help diagnose alopecia areata and guide future treatment strategies.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an immunomediated inflammatory skin disease that causes hair loss without scarring, usually appearing as isolated or multiple hairless patches on the scalp [

1]. With a prevalence of 0.5-2%, an estimated 6.6 million individuals in the U.S. and 147 million worldwide are affected [

2,

3]. While mild cases can be managed with topical corticosteroids, approximately 10% of patients progress to more severe forms such as alopecia totalis (total scalp hair loss, AT) or alopecia universalis (loss of all body hair, AU) [

4]. Prior research has indicated systemic inflammatory activity in these severe cases, [

5,

6] and various treatments targeting these severe stages are currently under clinical trial [

7,

8].

Traditional clinical criteria used to assess AA severity include the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) [

9], which quantifies the extent and density of scalp hair loss; the visual Alopecia Areata Investigator Global Assessment (AA-IGA) [

10], based on patient and physician inspections; and the Alopecia Areata Disease Activity Index (ALADIN) [

11], which utilizes a patented panel of skin-expressed genes to monitor disease activity and classify severity. However, these methods have limitations: SALT and AA-IGA primarily provide a current severity stage without predicting disease progression, while ALADIN, though more diagnostic, requires invasive skin biopsies.

Emerging biomarkers of severity [

12,

13,

14], progression [

15], and treatment response [

16,

17] offer a promising alternative. To a lesser extent, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been described emerging with these functions [

18,

19,

20,

21]. miRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs which regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to complementary messenger RNA sequences, often leading to gene silencing. Circulating miRNAs are stable in the bloodstream and can reflect pathophysiological conditions, making them valuable for early diagnosis and monitoring of AA and other diseases [

22].

This study profiles circulating miRNAs in alopecia areata (AA) patients to explore associated biological pathways and molecular underpinnings. By analyzing miRNA expression and pathway interactions, we aim to enhance understanding of AA’s pathophysiology and identify new therapeutic targets, potentially revolutionizing its clinical management with miRNA-based strategies.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included patients over 17 years of age with a clinical diagnosis of AA, excluding those with other immunologically mediated diseases, except Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, provided that the patient was in a state of euthyroidism with or without medication. All patients were required to be treatment-naive for AA, both topically and systemically, or to have undergone a previous washout period. The washout period was two weeks for topical corticosteroids and topical minoxidil, four weeks for intralesional corticosteroids, systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine, and three months or more than five times the half-life of the drug for any biological or JAK inhibitors. The control group consisted of individuals who donated blood without associated inflammatory pathology, matching age and sex with the patient group.

Disease Severity Assessment

The severity of AA was evaluated considering the number of hairless plaques, their extent, and the duration of the disease. The extent of the plaques was quantified using the SALT. Based on these criteria, patients were classified into two groups: a) Mild AA: Patients with plaques covering less than 50% of the affected area and a disease duration of less than one year. b) Severe AA: Patients with a disease duration of more than one year, plaques affecting 50% or more of scalp involvement (SALT score), or exhibiting AT or AU. While this 1-year threshold is not a universally standardized criterion, it was applied here to enrich for patients with long-standing, treatment-refractory disease—an especially relevant group for biomarker discovery.

Positive controls were enrolled into the validation subanalysis based on the following severity definitions and thresholds: severe atopic dermatitis (AD), Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) ≥ 3 and/or Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) ≥ 12; [

23] severe plaque psoriasis (PsO), Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) ≥ 3 and/or Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) > 10;[

24] non-segmental vitiligo, Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI) and/or Vitiligo Extent Score (VES) > 10% [

25]. These standardized scales and indexes ensure consistent and accurate assessment of disease severity across different conditions, facilitating meaningful comparisons and a robust analysis.

Sample Collection

After an 8-hour fasting period, a sample of anticoagulated blood (K2-EDTA 5.4 mg) was collected. Blood was centrifuged at 1,800 g for 10 minutes at room temperature to obtain plasma samples. The upper layer phase containing the plasma was carefully collected and stored at -80 °C for further analysis. A Qiagen commercial kit (miRNeasy serum / plasma kit) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions for miRNA purification. From 200 µL of plasma, miRNA was purified and eluted using 14 µL of RNase-free water. The purified miRNA samples were quantified and stored at -80 °C for future use.

Discovery Phase

In the discovery phase, a cohort of ten patients with AA (5 mild, 5 severe) and ten healthy controls was selected. Reverse transcription of 758 miRNAs per sample was performed using the TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The samples were then analyzed with the TaqMan OpenArray Human MicroRNA Panel, offering a high-throughput platform for comprehensive miRNA profiling.

Validation Phase

Technical Validation

To validate the OpenArray results, real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed on the same samples using the QuantStudio 12K Flex system. Data analysis with Thermo Fisher Connect software confirmed the differential expression of specific miRNAs.

Clinical validation

The validated miRNAs were assessed as circulating biomarkers for disease classification by comparing 30 patients with AA to 30 healthy controls and 30 patients with other immune-mediated skin diseases, ten patients for each group: PsO, severe AD, and non-segmental vitiligo. This analysis aimed to evaluate the specificity and diagnostic potential of the miRNA profile for AA, distinguishing it from other inflammatory skin conditions.

Predictive Model

To develop a predictive model using miRNA expression data, the dataset was split into 70% for training and 30% for testing. A machine learning classifier was trained on the training set, with performance evaluated on the test set using accuracy, AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve), and a confusion matrix. ROC curves were generated for validated miRNAs to assess classification performance, and the top-performing miRNAs were ranked. The best four miRNAs were used to generate ROC curves to distinguish patients with AA from controls, with the top miRNA further analyzed for its potential to differentiate AA from other immune diseases, evaluating its specificity as an AA biomarker.

Biological Insights and Pathway Analysis

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Enrichment analysis of the validated miRNAs was performed using target gene sets across multiple databases, including Gene Ontology (Biological Process and Molecular Function), KEGG pathways, Reactome, and WikiPathways. The analysis, conducted with GeneCodis 4 [

25], applied a hypergeometric distribution and corrected p-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Identification of Drug Targets

Differentially expressed circulating miRNAs in severe AA were cross-referenced with PharmaGKB and LINCS databases to identify potential therapeutic drugs. These databases provide insights into small molecules and their impact on gene expression and pathways, highlighting promising drug candidates for AA treatment based on miRNA-related pathways.

Statistical Analysis

Results of the miRNA expression analysis were obtained in terms of cycle threshold (Ct) values and were subsequently normalized using the formula miRNAnormalized=2−(miRNA−miRNA with the lowest variability). Missing values were estimated at 20% of the minimum expression level. Data underwent quality control and batch corrections. Group differences in miRNA expression were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests (significance p < 0.05), with post hoc comparisons to identify specific group differences. Results were visualized with dendrograms, heatmaps, and miRNA term networks to display relationships between miRNAs and functional terms. Statistical analyses were conducted using R and Python.

Ethics

The project was approved by the Cordoba Provincial Research Ethics Committee, and all patients provided informed consent after reviewing the patient information sheet. Data were anonymized to protect confidentiality, in line with good clinical practice, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Belmont Report. Anonymization followed EU Regulation 2016/679 and Spain’s Organic Law 3/2018 to ensure participant privacy and compliance with data protection standards.

Availability of Data and Reproducibility of Results

Raw data and R scripts used for statistical analysis are available upon reasonable request. Data requests will be reviewed to ensure they comply with ethical and scientific standards.

Results

Population Characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the population in both the Discovery and Validation phases are shown in

Table 1. In the discovery/technical validation phases, there were no significant differences in gender (p = 0.54) or age (p = 0.61) between the AA severe, AA mild-moderate, and control groups. Similarly, the Clinical validation phase with a larger cohort found no significant differences in gender (p = 0.76) or age (p = 0.45) across AA severe, AA mild-moderate, control, vitiligo, AD, and PsO groups. Further details are provided in

Table S1.

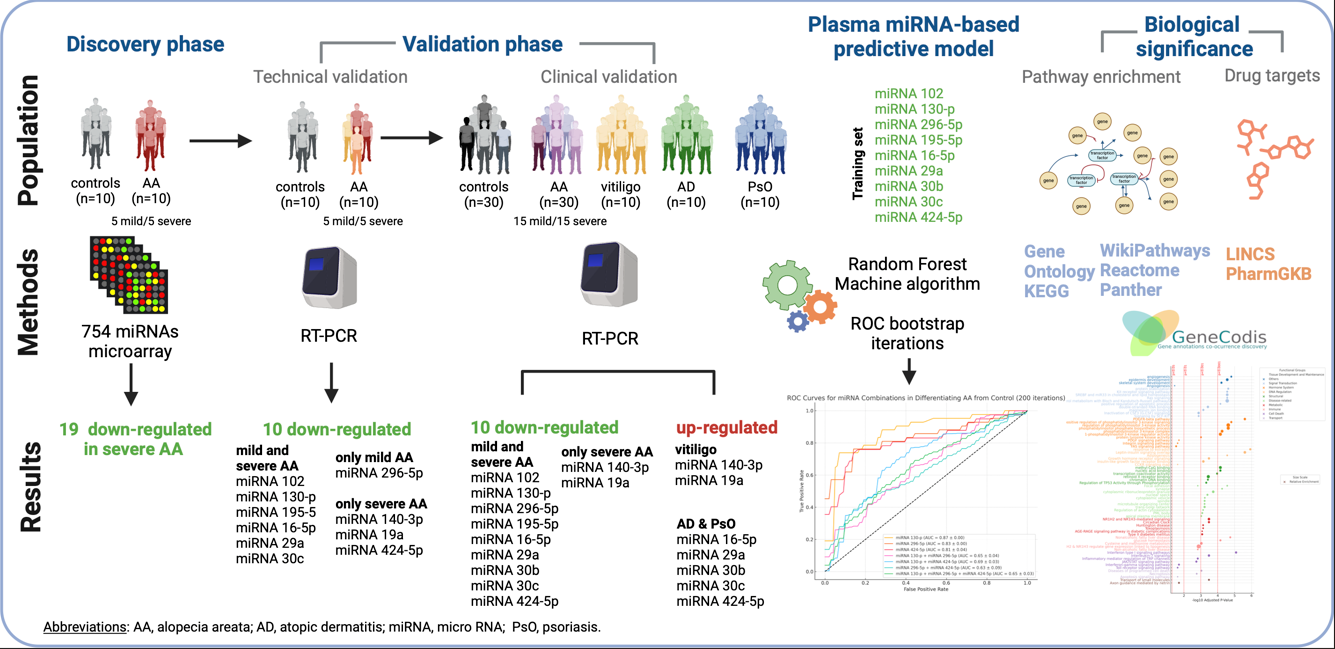

Discovery Phase

In the discovery phase, 19 miRNAs, including miR-16-5p, miR-296-5p, miR-140-3p, miR-29b-3p, and miR-424-5p, were significantly downregulated in severe AA compared to controls, indicating a shared regulatory mechanism in AA pathogenesis (

Figure 1 and

Table 2. Mild cases showed only three differentially expressed miRNAs: two upregulated (miR-495-3p, miR-655-3p) and one downregulated (miR-495-3p), all with lower fold-change values than in severe AA.

Validation Phase

In the v

alidation phase (

Figure 2), we focused on the 19 downregulated miRNAs in severe AA due to their consistent and robust downregulation, providing a clearer molecular profile for validation. Of these, 10 miRNAs were technically validated in both mild and severe AA (e.g., miR-102, miR-130-p, miR-195-5p), while others were specific to mild or severe AA (e.g., miR-296-5p in mild AA, miR-140-3p in severe AA).

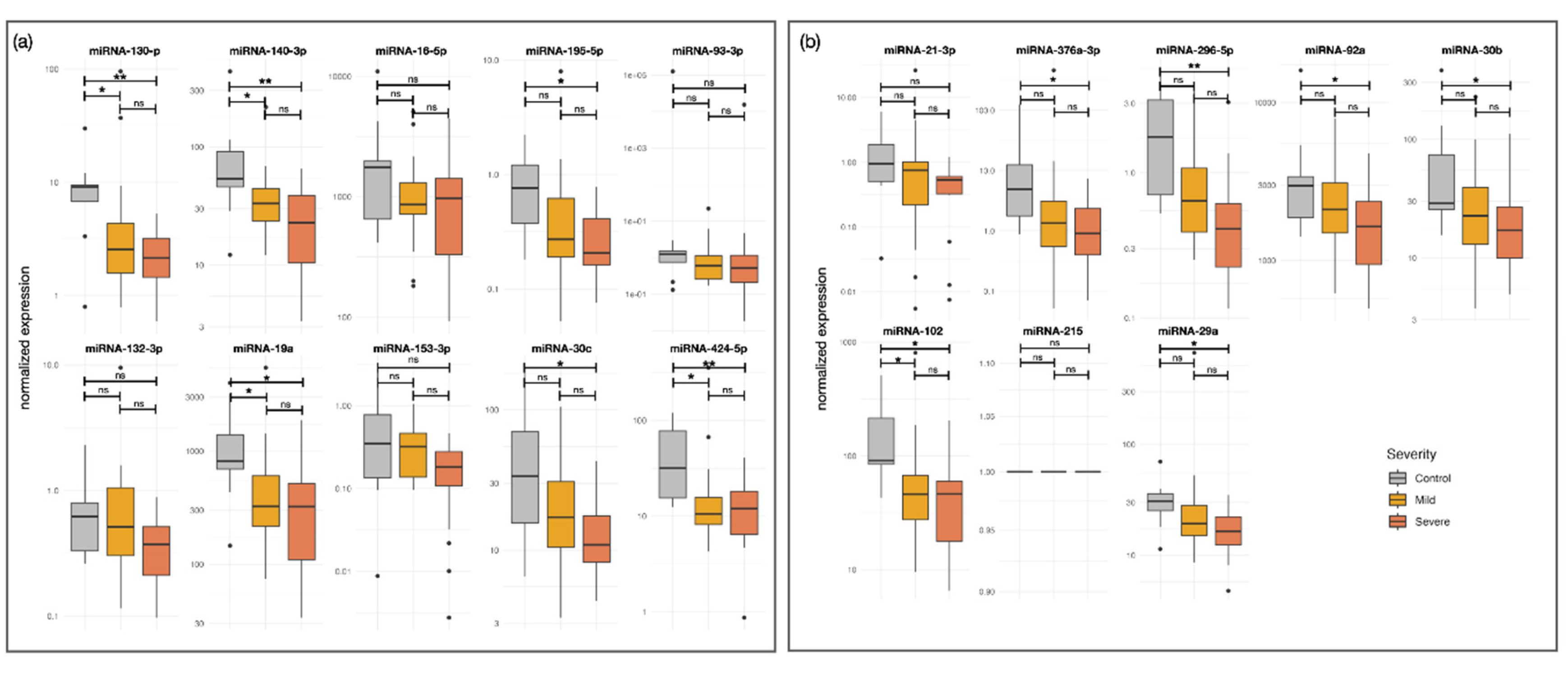

In

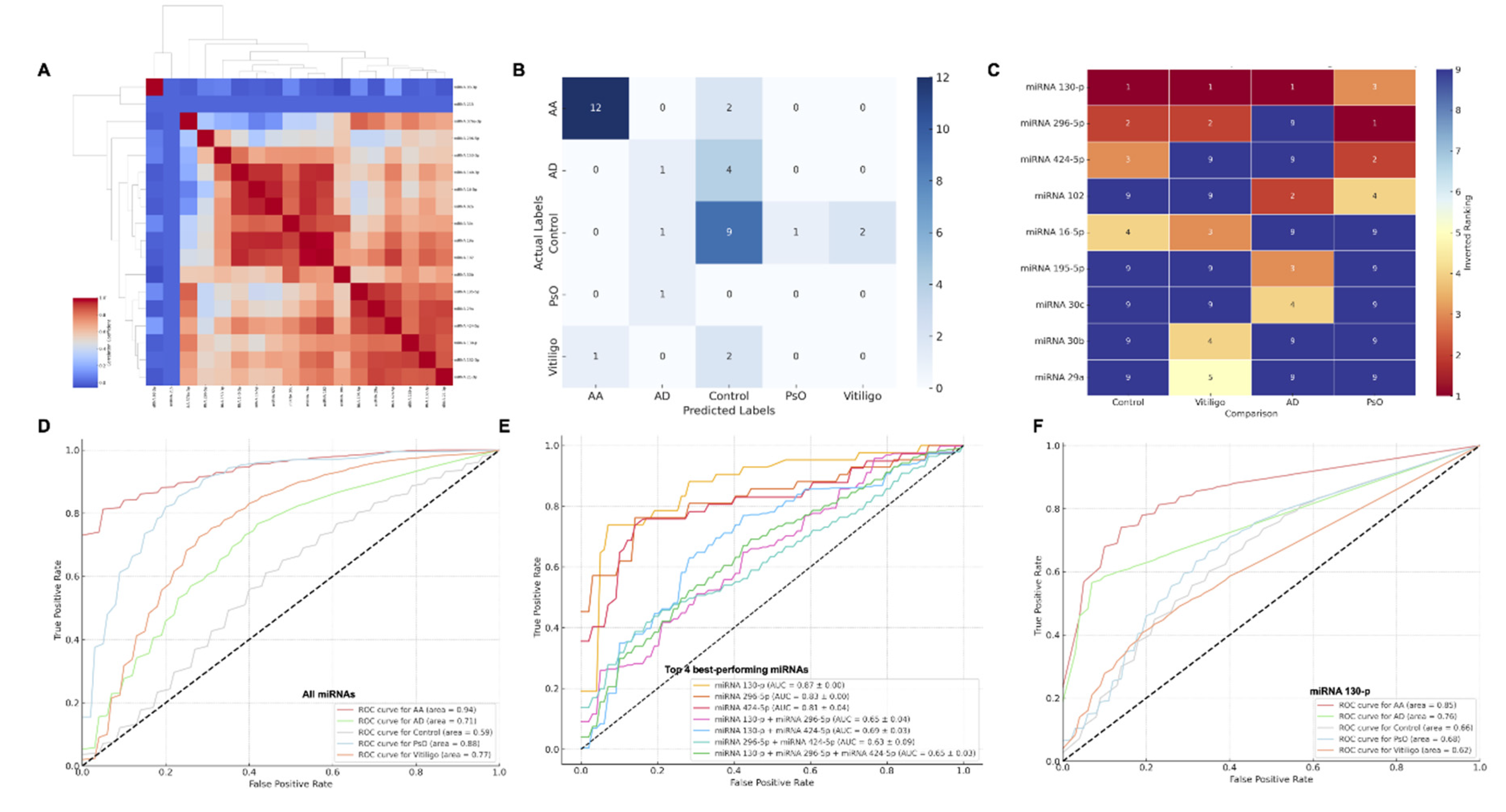

clinical validation (

Figure 3), all tested miRNAs remained significantly downregulated in patients with AA, with some shifting between severity groups. Additionally, certain miRNAs were upregulated in non-segmental vitiligo, AD, and PsO. Co-expression analysis (

Figure 4A) revealed strong correlations among miRNAs, suggesting co-regulation, with unique patterns emerging in severe AA.

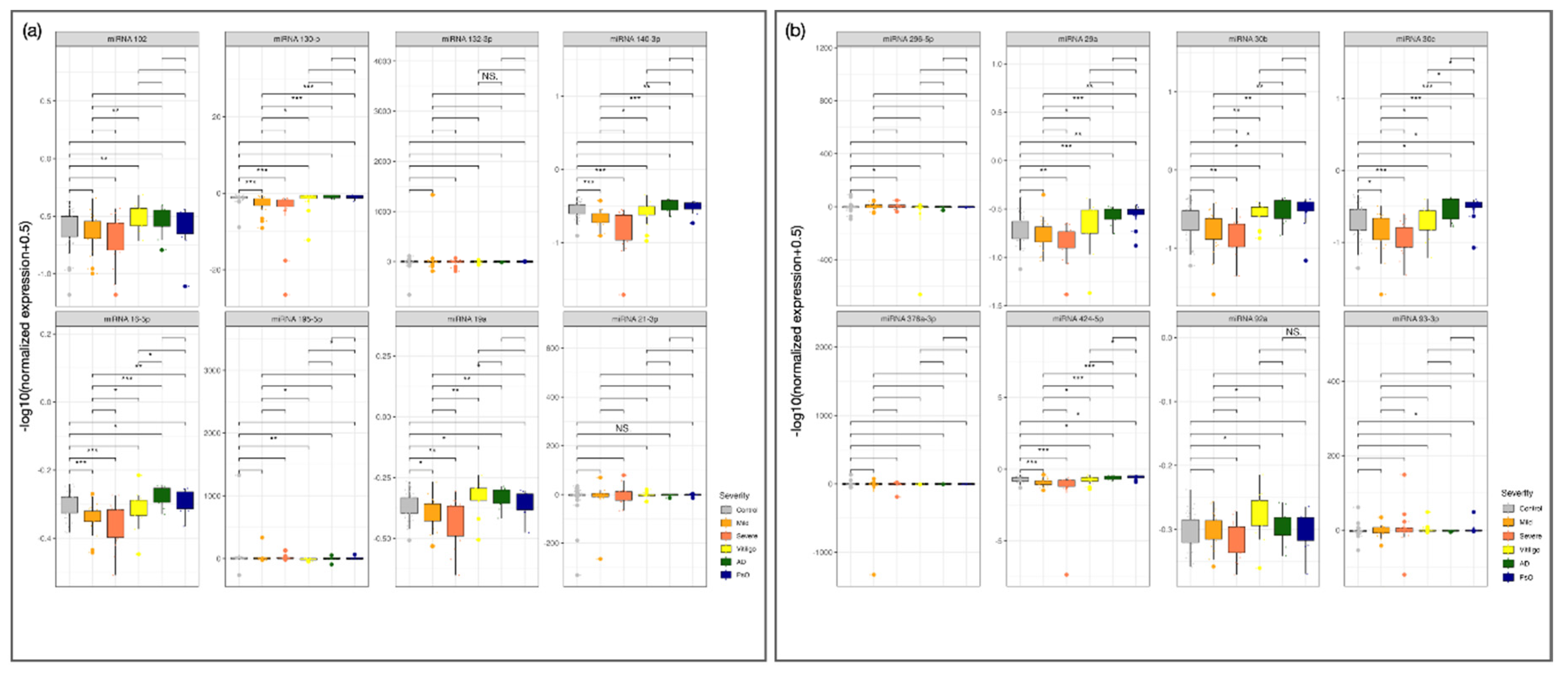

Plasma miRNA-Based Predictive Model

We used logistic regression, ROC curve analysis, and bootstrap iterations to evaluate the performance of 10 validated miRNAs. The model, trained on 70% of the samples and tested on the remaining 30%, showed strong performance for AA, correctly classifying 12 of 14 samples (

Figure 4B).

ROC analysis revealed high discriminatory power for AA (AUC = 0.94) and PsO (AUC = 0.88), moderate for vitiligo (AUC = 0.77), and lower for controls (AUC = 0.59) (

Figure 4D). Testing combinations of top miRNAs (miR-130-p, miR-296-5p, miR-424-5p) did not outperform single miRNAs ((

Figure 4E). miR-130-3p alone (AUC = 0.85) showed strong potential as an AA biomarker ((

Figure 4F).

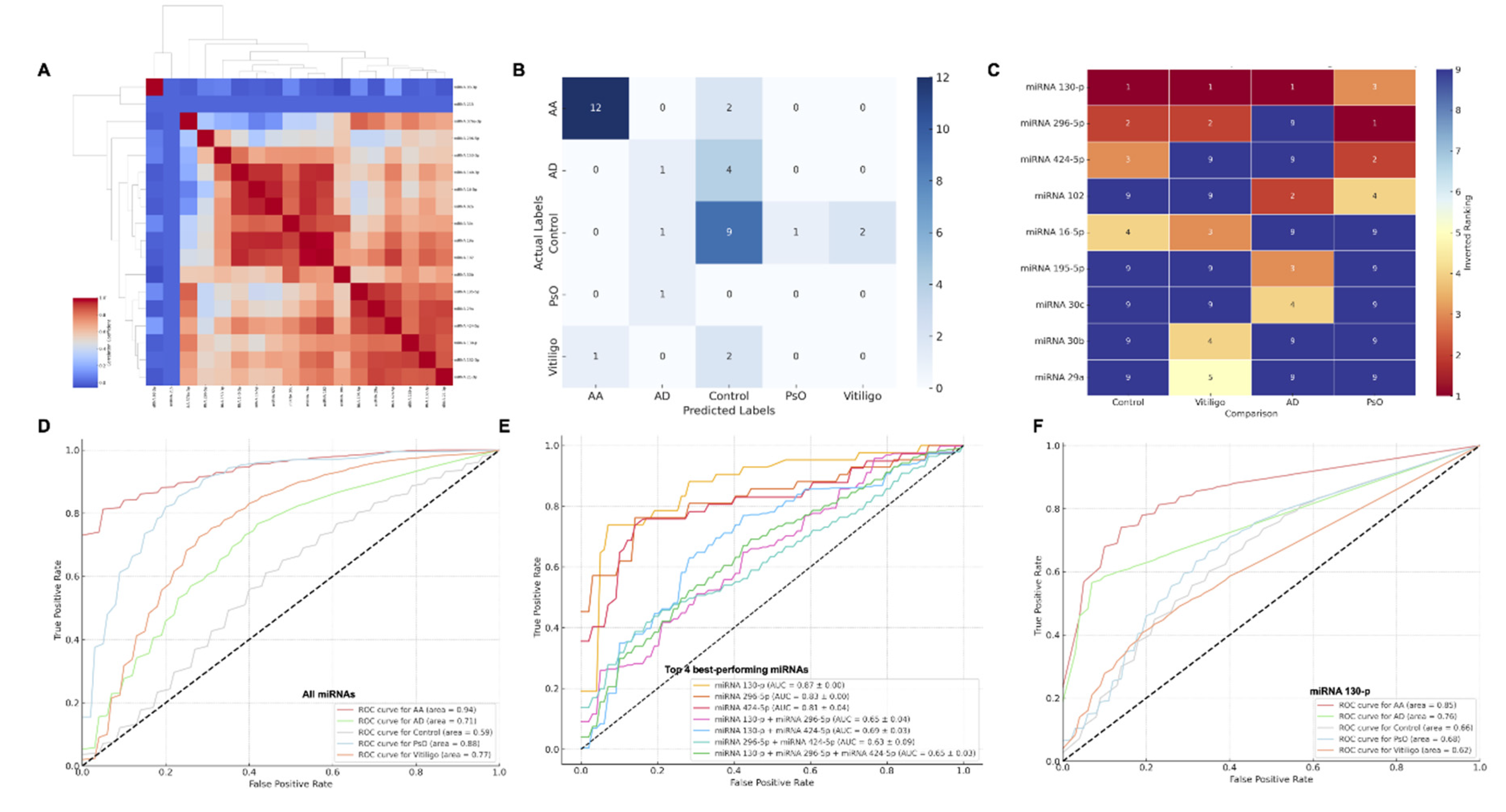

Biological Significance

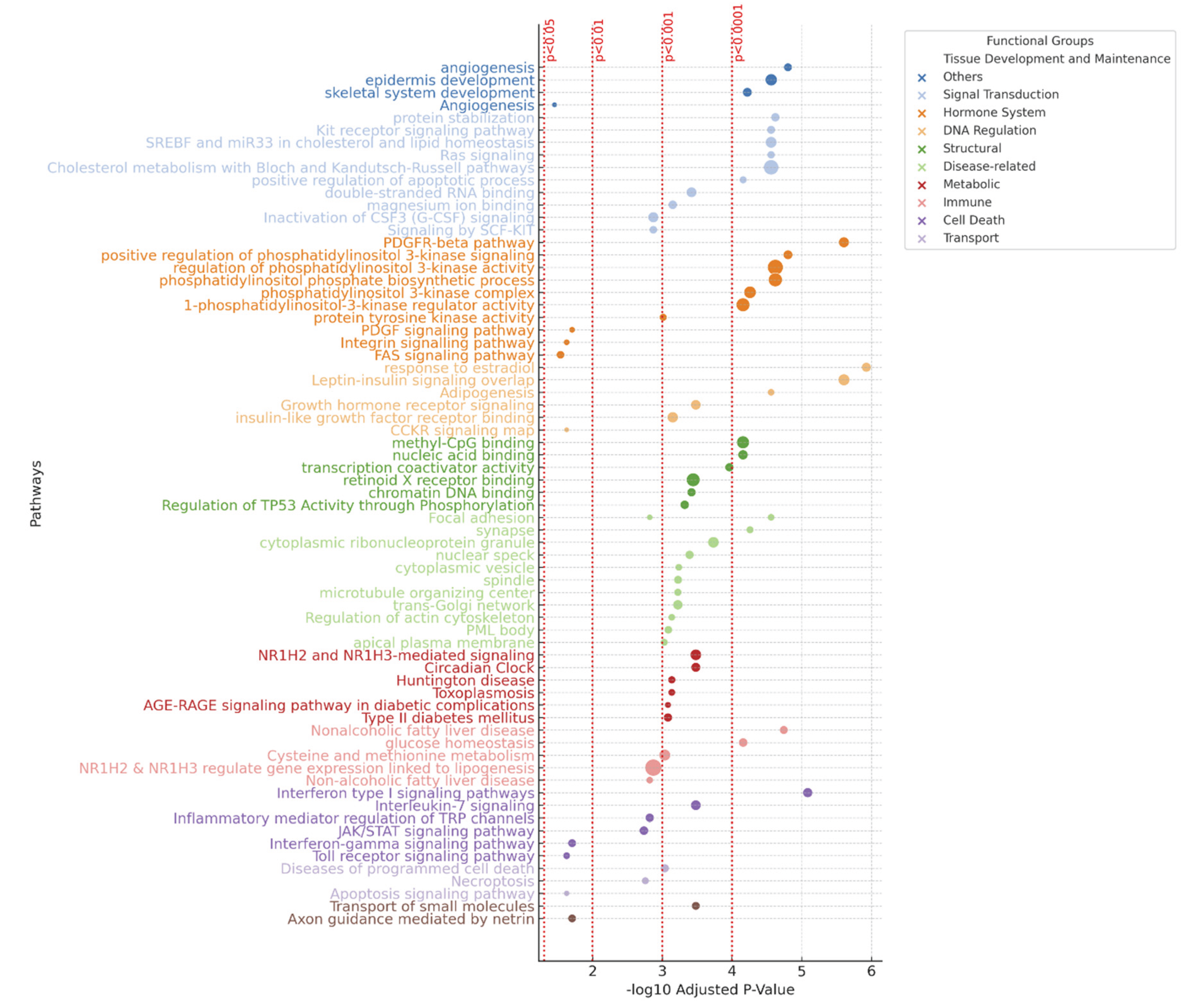

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Following the analysis of 9 validated miRNAs, 2,811 enriched pathways across databases, including Panther, KEGG, WikiPathways, Reactome, and GO. Key immune-related pathways included Interferon-gamma, Toll receptor, JAK/STAT, and TRP channel signaling, highlighting immune dysregulation in AA. Metabolic pathways like Cysteine and methionine metabolism, NAFLD, and lipogenesis also showed enrichment, suggesting metabolic involvement. Signal transduction pathways, including PDGF, MAPK, and Hippo signaling, were enriched, emphasizing their importance in AA. Some pathways, such as Huntington’s disease and Type II diabetes, suggest miRNA dysregulation in AA has broader implications (

Figure 4).

Drug Targets

Drug targets Analysis of miRNA profiles in AA identified 39 potential therapeutic drugs from LINCS and PharmGKB. Of these, 41% were kinase inhibitors, primarily JAK inhibitors, including sunitinib, pazopanib, semaxanib, sorafenib, dovitinib, tivozanib, axitinib, cediranib, orantinib, motesanib, linifanib, danusertib, ENMD-2076, SU-11652, BMS-536924, Tyrphostin-AG-1295, and PP30. Other identified drugs belonged to groups of antioxidants (12.8%; catechin, curcumin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, and rhamnetin), epigenetic regulators (7.7%; azacitidine, zebularine), and antimicrobial agents (15.4%; triclosan, procainamide, pyrazinamide, flucytosine, triclabendazole, methyl norlichexanthone). The remaining 23.1% were substances with toxic effects or in very early stages of development, and thus were not considered a priority. These findings highlight promising drug candidates for targeting miRNA dysregulation in AA.

Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive miRNA plasma profiling in patients with severe AA, offering a multi-phase approach that strengthens the reliability of the findings. By including various immune-mediated skin conditions such as PsO, AD, and non-segemental vitiligo, the study underscores the specificity of the miRNA signature to AA. The use of machine learning models provides a modern approach to classify AA based on miRNA expression, demonstrating strong classification power, especially in distinguishing AA from healthy controls. The identification of potential therapeutic targets, particularly JAK inhibitors, based on dysregulated miRNA pathways, offers actionable insights for AA treatment. Additionally, pathway enrichment analysis links the dysregulated miRNAs to immune-related and metabolic pathways, deepening the understanding of AA’s pathogenesis

Several miRNAs identified in our study have been shown to play key roles in skin physiology, particularly in hair follicle biology and keratinocyte function. For instance,

miR-195-5p,

miR-29a, and

miR-140-5p have been shown to regulate hair follicle development, which suggests that their downregulation in severe AA could disrupt normal hair follicle function. [

27,

28,

29] Moreover,

miR-130b-3p and

miR-93-3p are involved in keratinocyte proliferation and migration, processes essential for maintaining hair follicle integrity and skin barrier function [

30,

31]. Further, miRNAs such as

miR-16-5p,

miR-132-3p,

miR-29b-3p, and

miR-376a-3p have been implicated in wound healing and the transition of epidermal stem cells to mature keratinocytes [

32].

In addition to their role in local inflammation and hair follicle biology, several miRNAs dysregulated in severe AA have been linked to systemic inflammatory diseases. For example,

miR-195-5p,

miR-214-3p, and

miR-16-5p are associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [

33,

34], while

miR-16-5p, miR-19a-3p, miR-132-3p,

miR-140-3p, miR-92a-3p, and

miR-424-5p are linked to autoimmune conditions such as osteoarthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. These connections suggest that miRNA dysregulation in severe AA may not be limited to the skin but may also reflect broader systemic immune dysregulation.

Additionally, several of the dysregulated miRNAs have implicated in cardiovascular disease (miR-16-5p, miR-325, miR-132-3p, miR-140-3p, miR-19a-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-424-5p, miR-92a-3p) [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52], heart failure (miR-30c-5p, miR-424-5p) [

53,

54], acute oronary syndrome (miR-140-3p) [

55], metabolic syndrome (miR-132-3p) [

56], and atherosclerosis (miR-325, miR-30c-5p, miR-424-5p) [

57,

58,

59]. This potential association highlights the importance of monitoring for cardiovascular risk factors in patients with AA, especially those with severe forms of the disease [

60].

Finally, although this study offers a comprehensive miRNA profiling in severe AA, it has certain limitations. The sample size, particularly for patients with other inflammatory skin diseases, is relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the ≥1-year duration criterion for defining severe disease is not universally established and may limit comparability with other cohorts. However, it allowed us to focus on more persistent cases with greater clinical need. The study is also limited by its focus on a single time point, lacking longitudinal data to observe how miRNA profiles change over time or with treatment. There may also be potential confounding factors, such as treatment history and disease duration, which were not fully controlled. Although miRNA expression was validated, functional experiments linking miRNA dysregulation to specific biological outcomes were not performed, limiting causal conclusions. Lastly, while the study highlights miRNA specificity for AA, it remains to be tested whether these miRNAs are dysregulated in other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, potentially affecting their utility as specific biomarkers for AA.

Circulating miRNAs hold promise as non-invasive biomarkers for immune-mediated skin diseases. Although this study focuses on diagnostic discrimination, the potential prognostic applications warrant exploration. Longitudinal studies could determine whether these miRNAs normalize or fluctuate with treatment response, offering insights into disease monitoring or stratification. Additionally, miRNAs involved in immune regulation or hair follicle cycling might serve as dynamic indicators of therapeutic efficacy.

This study represents an exploratory effort to identify and validate circulating miRNA signatures in severe AA. While the results are robust across discovery and validation cohorts, functional validation of target pathways is required to establish mechanistic relevance. Future work should integrate experimental approaches to confirm the roles of these miRNAs in disease pathogenesis.

Future Directions

Building upon these results, future research should focus on longitudinal sampling to evaluate whether circulating miRNA levels vary with disease activity and treatment response. Functional studies are also needed to elucidate the mechanistic roles of these miRNAs in immune dysregulation and follicular biology. Ultimately, such efforts may help transition these molecular signatures from diagnostic tools to actionable biomarkers guiding clinical decisions in AA.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study adds to the growing body of knowledge on systemic miRNA dysregulation in AA, highlighting the importance of both local and systemic factors in the disease’s complex pathogenesis. By identifying specific dysregulated miRNAs in the blood of patients with severe AA, we reveal a broader systemic miRNA dysregulation that extends beyond the skin. These findings offer new insights into the role of miRNAs in AA and open pathways for future therapeutic development. Larger, more diverse studies are needed to confirm these results and assess their broader applicability across AA subtypes.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

No medical writing assistance or editorial support was provided by third parties. The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) exclusively as a programming and visualization support tool (e.g., in R/Python). This tool was not used to generate original scientific content or to draft any part of the manuscript. All content was written by the authors, who assume full responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Juan Ruano. Data curation: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Macarena Aguilar-Luque, Irene Rivera-Ruiz. Formal analysis: José Liñares-Blanco, Pedro Carmona-Saez, Juan Ruano. Funding acquisition: Beatriz Isla-Tejera, Pedro Carmona-Saez, Juan Ruano. Investigation: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Macarena Aguilar-Luque, José Liñares-Blanco. Methodology: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Beatriz Isla-Tejera. Project administration: Carmen Mochón-Jiménez, Irene Rivera-Ruiz, Esmeralda Parra-Peralbo, Juan Ruano. Resources: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Pedro J. Gómez-Arias, Irene Rivera-Ruiz, Miguel Juan-Cencerrado. Software: José Liñares-Blanco, Pedro Carmona-Saez Supervision: Esmeralda Parra-Peralbo, Juan Ruano. Validation: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Juan Ruano. Visualization: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, José Liñares-Blanco, Juan Ruano. Writing—original draft: Jesús Gay-Mimbrera, Macarena Aguilar-Luque. Writing—review and editing: Beatriz Isla-Tejera, Juan Ruano.

Funding

This research was supported exclusively by public funds. Specifically, it received partial funding from Project PI23/01590 (awarded to Juan Ruano), funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-funded by the European Union. J.G.-M. and M.A.-L. received support from the Plan Propio de Investigación at the Instituto Maimónides de Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba (IMIBIC). P.G.-A. received funding from the International Eczema Council 2022 Research Fellowship Program. E.P.-P. was supported by Universidad Europea de Madrid. No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this article. No pharmaceutical company contributed to the study design, data collection or analysis, manuscript writing, or publication decision.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 1983), the Belmont Report, and national and European regulations on clinical research and data protection. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was approved by the Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Córdoba, Spain (approval number HRP-503).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in the supplementary materials. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients with alopecia areata and the healthy and disease control participants for their invaluable contribution to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Juan Ruano is a member of the Editorial Board of Dermatology and Therapy. He was not involved in the peer review or editorial decision-making process for this manuscript. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ho CY, Wu CY, Chen JY, Wu CY. Clinical and genetic aspects of alopecia areata: A cutting edge review. Genes (Basel). 2023;14(7):1362. [CrossRef]

- Jeon JJ, Jung SW, Kim YH, et al. Global, regional, and national epidemiology of alopecia areata: A systematic review and modelling study. Br J Dermatol. Published online February 9, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bewley A, Figueras-Nart I, Zhang J, et al. Patient-reported burden of severe alopecia areata: First results from the multinational alopecia areata unmet need survey. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:751-761. [CrossRef]

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: Current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(4):825-834. [CrossRef]

- Dubin C, Glickman JW, Del Duca E, et al. Scalp and serum profiling of frontal fibrosing alopecia reveals scalp immune and fibrosis dysregulation with no systemic involvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(3):551-562. [CrossRef]

- Glickman JW, Dubin C, Dahabreh D, et al. An integrated scalp and blood biomarker approach suggests the systemic nature of alopecia areata. Allergy. 2021;76(10):3053-3065. [CrossRef]

- Westerkam LL, McShane DB, Nieman EL, Morrell DS. Treatment options for alopecia areata in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. Published online March 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka L, Arenbergerova M, Grimalt R, et al. European expert consensus statement on the systemic treatment of alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38(4):687-694. [CrossRef]

- Olsen EA, Canfield D. SALT II: A new take on the severity of alopecia tool (SALT) for determining percentage scalp hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(6):1268-1270. [CrossRef]

- Wyrwich KW, Kitchen H, Knight S, et al. The alopecia areata investigator global assessment scale: A measure for evaluating clinically meaningful success in clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):702-709. [CrossRef]

- Jabbari A, Cerise JE, Chen JC, et al. Molecular signatures define alopecia areata subtypes and transcriptional biomarkers. EBioMedicine. 2016;7:240-247. [CrossRef]

- Waśkiel-Burnat A, Niemczyk A, Blicharz L, et al. Chemokine C-C motif ligand 7 (CCL7), a biomarker of atherosclerosis, is associated with the severity of alopecia areata: A preliminary study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(22):5418. [CrossRef]

- Stochmal A, Waśkiel-Burnat A, Chrostowska S, et al. Adiponectin as a novel biomarker of disease severity in alopecia areata. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13809. Published 2021 Jul 5. [CrossRef]

- Waśkiel-Burnat A, Niemczyk A, Chmielińska P, et al. Lipocalin-2 and insulin as new biomarkers of alopecia areata. PLoS One. 2022;17(5).

- Published 2022 May 31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang T, Nie Y. Prediction of the risk of alopecia areata progressing to alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis: Biomarker development with bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Dermatology. 2022;238(2):386-396. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulati N, Bonifacio KM, et al. Biomarkers of alopecia areata disease activity and response to corticosteroid treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25(4):282-286. [CrossRef]

- Inui S, Noguchi F, Nakajima T, Itami S. Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine as disease activity and response biomarker in alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2013;40(11):881-885. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa AI, Al-Refaie AM, El-Shimi OS, Fawzy E, Sorour NE. Diagnostic implications of MicroRNAs; 155, 146a, and 203 lesional expression in alopecia areata: A preliminary case-controlled study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(6):2648-2654. [CrossRef]

- Wang EHC, DeStefano GM, Patel AV, et al. Identification of differentially expressed miRNAs in alopecia areata that target immune-regulatory pathways. Genes Immun. 2017;18(2):100-104. [CrossRef]

- Tafazzoli A, Forstner AJ, Broadley D, et al. Genome-wide microRNA analysis implicates miR-30b/d in the etiology of alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(3):549-556. [CrossRef]

- Roso-Mares A, Andújar I, Díaz Corpas T, Sun BK. Non-coding RNAs as skin disease biomarkers, molecular signatures, and therapeutic targets. Hum Genet. Published online August 14, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Wu H, Zhao M, Lu Q. Identifying the differentially expressed microRNAs in autoimmunity: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmunity. 2020;53(3):122-136. [CrossRef]

- Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, et al. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): Assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11-18. [CrossRef]

- Smith CH, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Yiu ZZ, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2017. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(3):628-636. [CrossRef]

- van Geel N, Lommerts J, Bekkenk M, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome measure in vitiligo: The self-assessment vitiligo extent score (SA-VES). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):464-471. [CrossRef]

- Tabas-Madrid D, Nogales-Cadenas R, Pascual-Montano A. GeneCodis4: A meta-tool for the integration of gene set enrichment and pathway analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(W1). [CrossRef]

- Zhu N, Huang K, Liu Y, Zhang H, Lin E, Zeng Y, Li H, Xu Y, Cai B, Yuan Y, Li Y, Lin C. miR-195-5p regulates hair follicle inductivity of dermal papilla cells by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin activation.

- Ge M, Liu C, Li L, et al. miR-29a/b1 inhibits hair follicle stem cell lineage progression by spatiotemporally suppressing WNT and BMP signaling. Cell Rep 2019; 29:2489-2504.e4. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Huang J, Liu Z, et al. miR-140-5p in small extracellular vesicles from human papilla cells stimulates hair growth by promoting proliferation of outer root sheath and hair matrix cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020; 8:593638. [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Zhou S, Cai W, Guo J. The miR-93-3p/ZFP36L1/ZFX axis regulates keratinocyte proliferation and migration during skin wound healing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020; 23:450-63. [CrossRef]

- Li CX, Li HG, Huang LT, et al. H19 lncRNA regulates keratinocyte differentiation by targeting miR-130b-3p. Cell Death Dis 2017; 8. [CrossRef]

- Song Z, Liu D, Peng Y, et al. Differential microRNA expression profile comparison between epidermal stem cells and differentiated keratinocytes. Mol Med Rep 2015; 11:2285-91. [CrossRef]

- Li JA, Wang YD, Wang K, et al. Downregulation of miR-214-3p may contribute to pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis via targeting STAT6. Biomed Res Int 2017; 2017:8524972. [CrossRef]

- Scalavino V, Piccinno E, Bianco G, et al. The increase of miR-195-5p reduces intestinal permeability in ulcerative colitis, modulating tight junctions’ expression. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23:5840. [CrossRef]

- Zhou R, Qiu P, Wang H, et al. Identification of microRNA-16-5p and microRNA-21-5p in feces as potential noninvasive biomarkers for inflammatory bowel disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2021; 13:4634-46. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Liu Z, Guo X, Zhang M. Circ_0128846/miR-140-3p/JAK2 network in osteoarthritis development. Immunol Invest 2022; 51:1529-47. doi:10.1080/08820139.2021.1981930. [CrossRef]

- Xie W, Jiang L, Huang X, et al. Hsa_circ_0004662 accelerates the progression of osteoarthritis via the microRNA-424-5p/VEGFA axis. Curr Mol Med 2024; 24:217-25. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Sun Y, Wan Y, et al. LncRNA NEAT1 promotes proliferation of chondrocytes via downregulation of miR-16-5p in osteoarthritis. J Gene Med 2020; 22. [CrossRef]

- Kim YJ, Yeon Y, Lee WJ, et al. Comparison of microRNA expression in tears of normal subjects and Sjögren syndrome patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019; 60:4889-95. [CrossRef]

- Dunaeva M, Blom J, Thurlings R, Pruijn GJM. Circulating serum miR-223-3p and miR-16-5p as possible biomarkers of early rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 2018; 193:376-85. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Patro PS, Aggarwal A. MicroRNA-132, miR-146a, and miR-155 as potential biomarkers of methotrexate response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2019; 38:877-84. [CrossRef]

- Zu B, Liu L, Wang J, et al. MiR-140-3p inhibits the cell viability and promotes apoptosis of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis through targeting sirtuin 3. J Orthop Surg Res 2021; 16:105. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang W, Chen Y, et al. MicroRNA-19a-3p promotes rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes via targeting SOCS3. J Cell Biochem 2019; 120:11624-32. [CrossRef]

- Tseng CC, Wu LY, Tsai WC, et al. Differential expression profiles of the transcriptome and miRNA interactome in synovial fibroblasts of rheumatoid arthritis revealed by next generation sequencing. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019; 9:98. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Zhang Z, Fu Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of artesunate on atherosclerosis via miR-16-5p and TXNIP regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Ann Transl Med 2021; 9:1558. [CrossRef]

- Pu Y, Zhao Q, Men X, et al. MicroRNA-325 facilitates atherosclerosis progression by mediating the SREBF1/LXR axis via KDM1A. Life Sci 2021; 277:119464. [CrossRef]

- Su Q, Liu Y, Lv XW, et al. LncRNA TUG1 mediates ischemic myocardial injury by targeting miR-132-3p/HDAC3 axis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020; 318. [CrossRef]

- Marques JL, Milagro FI, Mansego ML, et al. Expression of inflammation-related miRNAs in white blood cells from subjects with metabolic syndrome after 8 wk of following a Mediterranean diet-based weight loss program. Nutrition 2016; 32:48-55. [CrossRef]

- Li XD, Yang YJ, Wang LY, et al. Elevated plasma miRNA-122, -140-3p, -720, -2861, and -3149 during early period of acute coronary syndrome are derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One 2017; 12. [CrossRef]

- Chen ZJ, Zhao XS, Fan TP, et al. Glycine improves ischemic stroke through miR-19a-3p/AMPK/GSK-3β/HO-1 pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020; 14:2021-3. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Yang P, Fu D, et al. Allicin protects against myocardial I/R by accelerating angiogenesis via the miR-19a-3p/PI3K/AKT axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2021; 13:22843-55. [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Guo M, Ma G, et al. MicroRNA-30c-5p protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via regulation of Bach1/Nrf2. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2021; 426:115637. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Zhong X, Li J, et al. MicroRNA-30c-5p inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated endothelial cell pyroptosis through FOXO3 down-regulation in atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018; 503:2833-40. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Zhao L, Zhao Y, et al. Circular RNA circ_0029589 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in ox-LDL-stimulated VSMCs by regulating miR-424-5p/IGF2 axis. Vascul Pharmacol 2020; 135:106782. [CrossRef]

- Li XD, Yang YJ, Wang LY, et al. Elevated plasma miRNA-122, -140-3p, -720, -2861, and -3149 during early period of acute coronary syndrome are derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. PLoS One 2017; 12. [CrossRef]

- Marques JL, Milagro FI, Mansego ML, et al. Expression of inflammation-related miRNAs in white blood cells from subjects with metabolic syndrome after 8 weeks of following a Mediterranean diet-based weight loss program. Nutrition 2016; 32:48-55. [CrossRef]

- Pu Y, Zhao Q, Men X, et al. MicroRNA-325 facilitates atherosclerosis progression by mediating the SREBF1/LXR axis via KDM1A. Life Sci 2021; 277:119464. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Zhong X, Li J, et al. MicroRNA-30c-5p inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated endothelial cell pyroptosis through FOXO3 down-regulation in atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018; 503:2833-40. [CrossRef]

- Yu H, Zhao L, Zhao Y, et al. Circular RNA circ_0029589 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in ox-LDL-stimulated VSMCs by regulating miR-424-5p/IGF2 axis. Vascul Pharmacol 2020; 135:106782. [CrossRef]

- George P, Jagun O, Liu Q, et al. Incidence rates of infections, malignancies, thromboembolism, and cardiovascular events in an alopecia areata cohort from a US claims database. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023; 13:1733-46.

Figure 1.

Validation of Down-Regulated miRNAs in Plasma of Patients with Alopecia Areata Compared to Controls. (a) Technical validation of five down-regulated miRNAs (miR-130-p, miR-140-3p, miR-16-5p, miR-195-5p, miR-93-3p) in plasma samples from patients with alopecia areata (AA), compared to controls. (b) Additional validated miRNAs (miR-132-3p, miR-19a, miR-153-3p, miR-30c, miR-424-5p), also down-regulated in AA patients. All samples were obtained from the same individuals included in the discovery phase. Boxplots show normalized expression levels in control individuals (gray), patients with mild AA (yellow), and patients with severe AA (orange). miR-215 was used as the normalizer. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Figure 1.

Validation of Down-Regulated miRNAs in Plasma of Patients with Alopecia Areata Compared to Controls. (a) Technical validation of five down-regulated miRNAs (miR-130-p, miR-140-3p, miR-16-5p, miR-195-5p, miR-93-3p) in plasma samples from patients with alopecia areata (AA), compared to controls. (b) Additional validated miRNAs (miR-132-3p, miR-19a, miR-153-3p, miR-30c, miR-424-5p), also down-regulated in AA patients. All samples were obtained from the same individuals included in the discovery phase. Boxplots show normalized expression levels in control individuals (gray), patients with mild AA (yellow), and patients with severe AA (orange). miR-215 was used as the normalizer. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

Clinical Validation of miRNA Expression in an Independent Cohort of Patients with AA Compared to control Groups and Other Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Skin Diseases. (a) Expression profiles of miR-21-3p, miR-376a-3p, miR-296-5p, miR-92a, and miR-30b in patients with AA (n = 30), healthy controls (n = 30), and disease controls with psoriasis (PsO, n = 10), atopic dermatitis (AD, n = 10), and non-segmental vitiligo (VIT, n = 10). (b) Additional miRNAs (miR-102, miR-215, and miR-29a) tested in the same cohort. Boxplots display log-transformed expression values [–log10(normalized expression + 0.5)]. This analysis aimed to assess the diagnostic specificity of selected miRNAs for AA compared to other inflammatory skin diseases. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

Clinical Validation of miRNA Expression in an Independent Cohort of Patients with AA Compared to control Groups and Other Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Skin Diseases. (a) Expression profiles of miR-21-3p, miR-376a-3p, miR-296-5p, miR-92a, and miR-30b in patients with AA (n = 30), healthy controls (n = 30), and disease controls with psoriasis (PsO, n = 10), atopic dermatitis (AD, n = 10), and non-segmental vitiligo (VIT, n = 10). (b) Additional miRNAs (miR-102, miR-215, and miR-29a) tested in the same cohort. Boxplots display log-transformed expression values [–log10(normalized expression + 0.5)]. This analysis aimed to assess the diagnostic specificity of selected miRNAs for AA compared to other inflammatory skin diseases. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

Figure 3.

Classification Performance of Validated Circulating miRNAs in Alopecia Areata and Other Immune-Mediated Skin Diseases. Panel A: Correlation heatmap displaying the clustering and correlation of the top-ranked differentially expressed miRNAs across Alopecia Areata (AA), Atopic Dermatitis (AD), Psoriasis (PsO), Vitiligo, and control subjects. Panel B: Confusion matrix summarizing the performance of the machine learning model in classifying the study groups based on miRNA expression profiles. Panel C: Heatmap ranking the top miRNAs by their predictive power across the different conditions. The color gradient represents the rank, with red indicating the top-ranked miRNAs for each comparison. Panel D: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve displaying the performance of the machine learning model using all miRNAs in distinguishing AA from other conditions (AUC = 0.94). Panel E: ROC curve comparing the classification performance of the top three miRNAs with the highest diagnostic potential for AA (miR-130p, miR-296-5p, and miR-424-5p) against controls and other conditions. Panel F: ROC curve for miR-130p across AA, AD, PsO, Vitiligo, and control groups, demonstrating its superior classification accuracy (AUC = 0.85 for AA).

Figure 3.

Classification Performance of Validated Circulating miRNAs in Alopecia Areata and Other Immune-Mediated Skin Diseases. Panel A: Correlation heatmap displaying the clustering and correlation of the top-ranked differentially expressed miRNAs across Alopecia Areata (AA), Atopic Dermatitis (AD), Psoriasis (PsO), Vitiligo, and control subjects. Panel B: Confusion matrix summarizing the performance of the machine learning model in classifying the study groups based on miRNA expression profiles. Panel C: Heatmap ranking the top miRNAs by their predictive power across the different conditions. The color gradient represents the rank, with red indicating the top-ranked miRNAs for each comparison. Panel D: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve displaying the performance of the machine learning model using all miRNAs in distinguishing AA from other conditions (AUC = 0.94). Panel E: ROC curve comparing the classification performance of the top three miRNAs with the highest diagnostic potential for AA (miR-130p, miR-296-5p, and miR-424-5p) against controls and other conditions. Panel F: ROC curve for miR-130p across AA, AD, PsO, Vitiligo, and control groups, demonstrating its superior classification accuracy (AUC = 0.85 for AA).

Figure 4.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Dysregulated Circulating miRNAs in Alopecia Areata. This figure presents the top enriched pathways regulated by dysregulated miRNAs in Alopecia Areata (AA) and other immune-mediated skin diseases. Pathways are ranked in descending order of statistical significance and are categorized into functional groups such as tissue development and maintenance, signal transduction, immune response, metabolic processes, and cell death. The x-axis represents the -log10 of the adjusted p-values for each pathway, highlighting their statistical significance. Horizontal dashed red lines indicate different significance thresholds (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Dysregulated Circulating miRNAs in Alopecia Areata. This figure presents the top enriched pathways regulated by dysregulated miRNAs in Alopecia Areata (AA) and other immune-mediated skin diseases. Pathways are ranked in descending order of statistical significance and are categorized into functional groups such as tissue development and maintenance, signal transduction, immune response, metabolic processes, and cell death. The x-axis represents the -log10 of the adjusted p-values for each pathway, highlighting their statistical significance. Horizontal dashed red lines indicate different significance thresholds (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Population in the Discovery and Validation Phases. This table summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population in both the Discovery and Validation phases, along with the p-values for gender and age comparisons between the groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Population in the Discovery and Validation Phases. This table summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population in both the Discovery and Validation phases, along with the p-values for gender and age comparisons between the groups.

| Phase |

Group |

Severity |

n |

Gender (M/F) |

Age(years) |

Pvalue gender(*) |

P value age (**) |

Discovery/Technical Validation

(n=20) |

AA |

Severe |

5 |

1/4 |

44.4 (20-61) |

0.54 |

0.61 |

| |

|

Mild-moderate |

5 |

2/3 |

42.6 (30-64) |

|

|

| |

control |

- |

10 |

5/5 |

36.8 (18-68) |

|

|

Clinical Validation

(n=90) |

AA |

Severe |

15 |

7/8 |

35.9 (23-47) |

0.76 |

0.45 |

| |

|

Mild-moderate |

15 |

6/9 |

46.2 (18-76) |

|

|

| |

control |

- |

30 |

13/17 |

44.8 (18-76) |

|

|

| |

Vitiligo |

- |

10 |

4/6 |

42.8 (16-74) |

|

|

| |

AD |

- |

10 |

7/3 |

44.8 (27-75) |

|

|

| |

PsO |

- |

10 |

7/3 |

47.6 (23-71) |

|

|

Table 2.

Significant Results of Differentially Expressed miRNAs in Severe AA from the Discovery Phase of the Study. In this analysis, a total of 740 probes were evaluated in patients with AA (n=10) compared to healthy controls (n=10) using a microarray platform. Each probe represents a unique identifier for a specific miRNA in the microarray, allowing for the detection of miRNA expression levels. The fold change (FCH) indicates the magnitude of expression change between severe AA cases and healthy controls, with positive values representing upregulation and negative values representing downregulation. The results are sorted by statistical significance (p-value) in descending order.

Table 2.

Significant Results of Differentially Expressed miRNAs in Severe AA from the Discovery Phase of the Study. In this analysis, a total of 740 probes were evaluated in patients with AA (n=10) compared to healthy controls (n=10) using a microarray platform. Each probe represents a unique identifier for a specific miRNA in the microarray, allowing for the detection of miRNA expression levels. The fold change (FCH) indicates the magnitude of expression change between severe AA cases and healthy controls, with positive values representing upregulation and negative values representing downregulation. The results are sorted by statistical significance (p-value) in descending order.

| microRNA |

Probe |

control |

Severe AA |

p values |

FCH |

| miR-195-5p |

477957 |

1.023 |

0.436 |

0.004 |

-0.586 |

| miR-93-3p |

478209 |

1.008 |

0.511 |

0.004 |

-0.496 |

| miR-130b-3p |

477840 |

1.021 |

0.578 |

0.008 |

-0.443 |

| miR-21-3p |

477973 |

1.038 |

0.5 |

0.008 |

-0.537 |

| miR-214-3p |

477974 |

1.073 |

0.4 |

0.008 |

-0.672 |

| miR-101-3p |

477863 |

1.062 |

0.428 |

0.017 |

-0.633 |

| miR-153-3p |

477922 |

1.229 |

0.262 |

0.017 |

-0.967 |

| miR-16-5p |

477860 |

1.05 |

0.457 |

0.017 |

-0.592 |

| miR-296-5p |

477836 |

1.01 |

0.668 |

0.017 |

-0.341 |

| miR-325 |

478025 |

1.169 |

0.345 |

0.017 |

-0.824 |

| miR-132-3p |

477900 |

1.038 |

0.536 |

0.03 |

-0.502 |

| miR-140-3p |

477908 |

1.049 |

0.57 |

0.03 |

-0.479 |

| miR-19a-3p |

479228 |

1.039 |

0.5 |

0.03 |

-0.539 |

| miR-29b-3p |

478369 |

1.026 |

0.568 |

0.03 |

-0.458 |

| miR-30b-5p |

478007 |

1.055 |

0.484 |

0.03 |

-0.571 |

| miR-30c-5p |

478008 |

1.039 |

0.525 |

0.03 |

-0.514 |

| miR-376a-3p |

478240 |

1.037 |

0.517 |

0.03 |

-0.52 |

| miR-424-5p |

478092 |

1.05 |

0.543 |

0.03 |

-0.506 |

| miR-92a-3p |

477827 |

1.067 |

0.469 |

0.03 |

-0.598 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).