Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

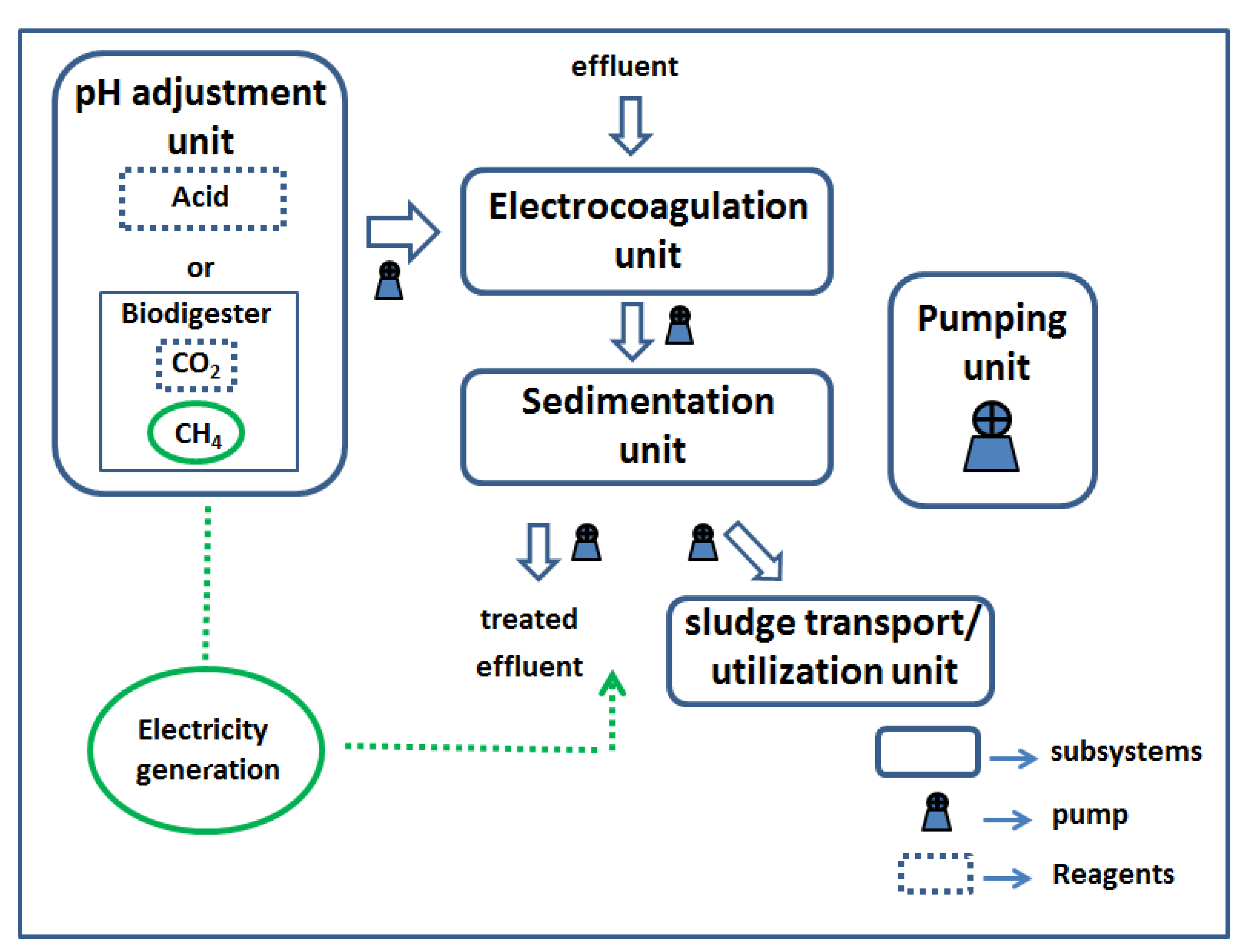

Description of system and conditions

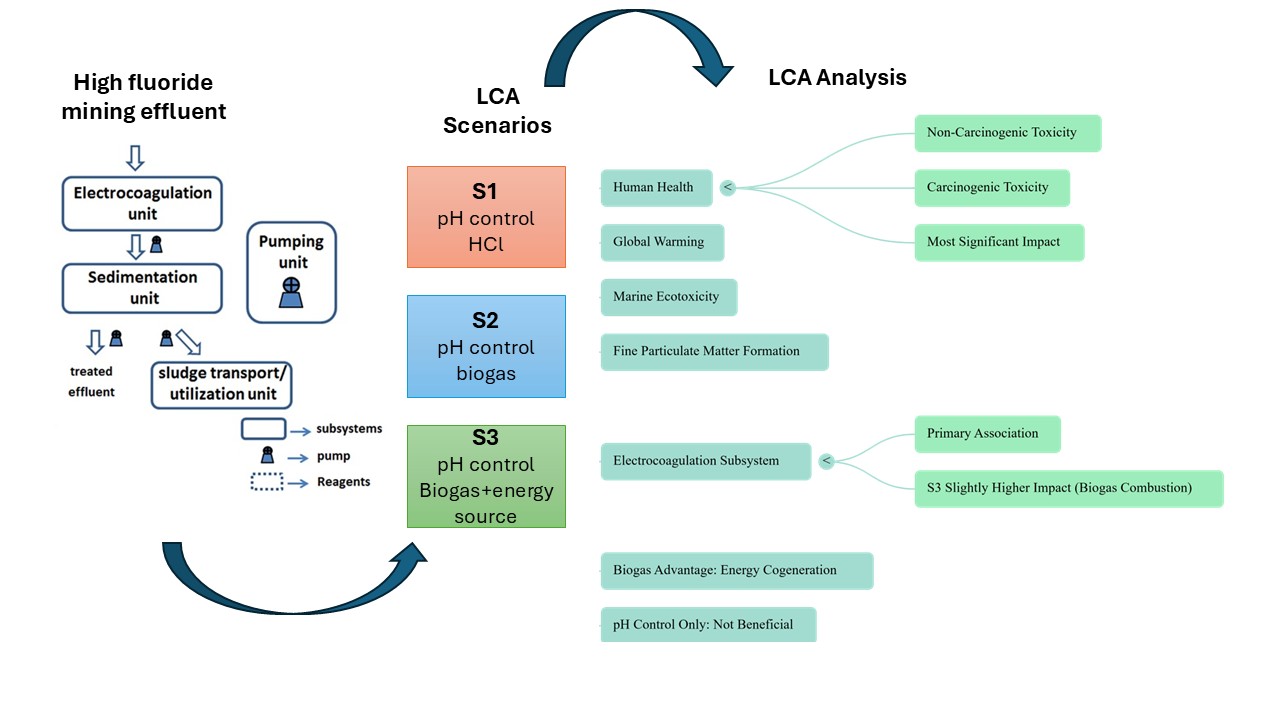

2.1. LCA methodology

2.2. Goal and scope of the study

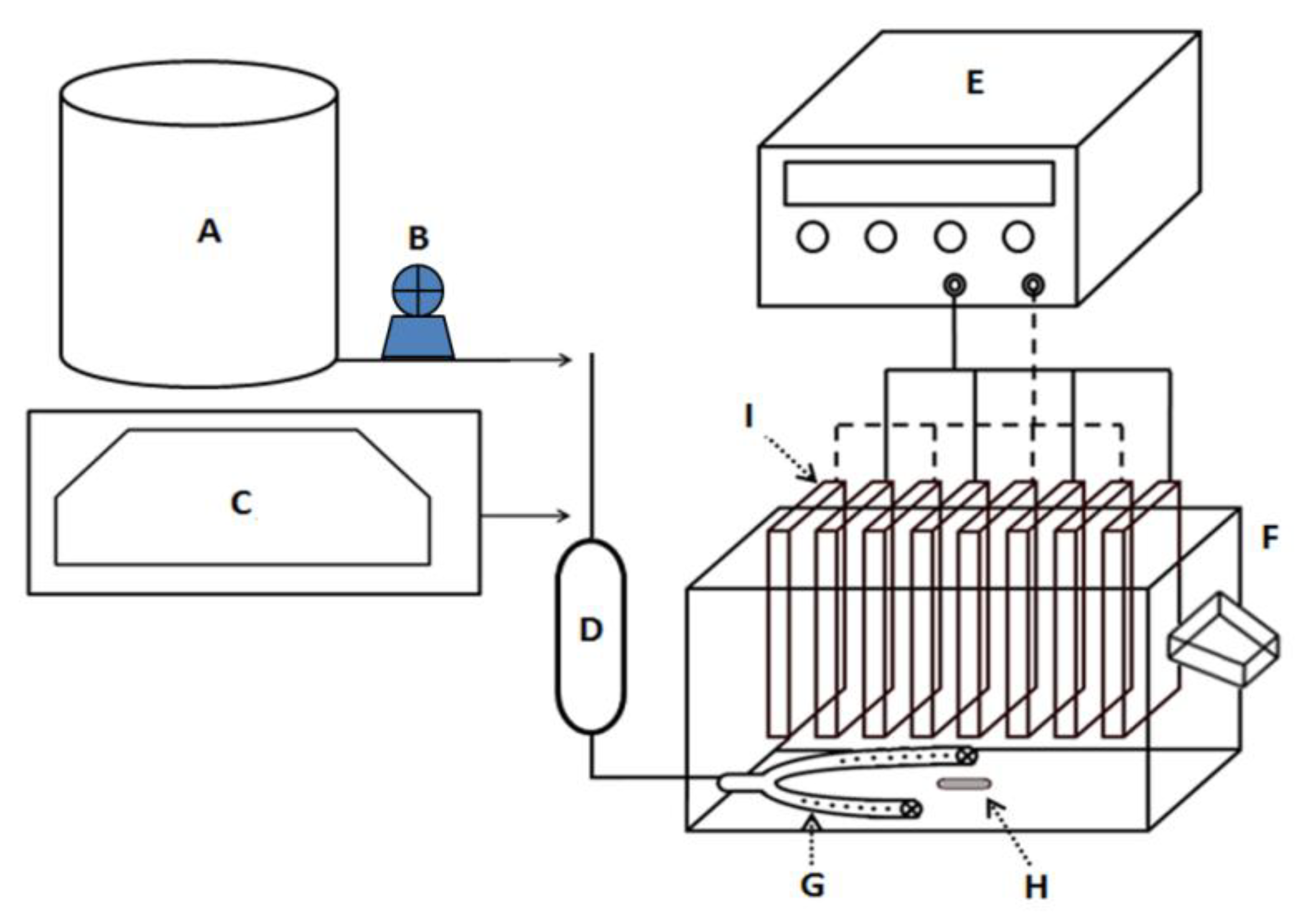

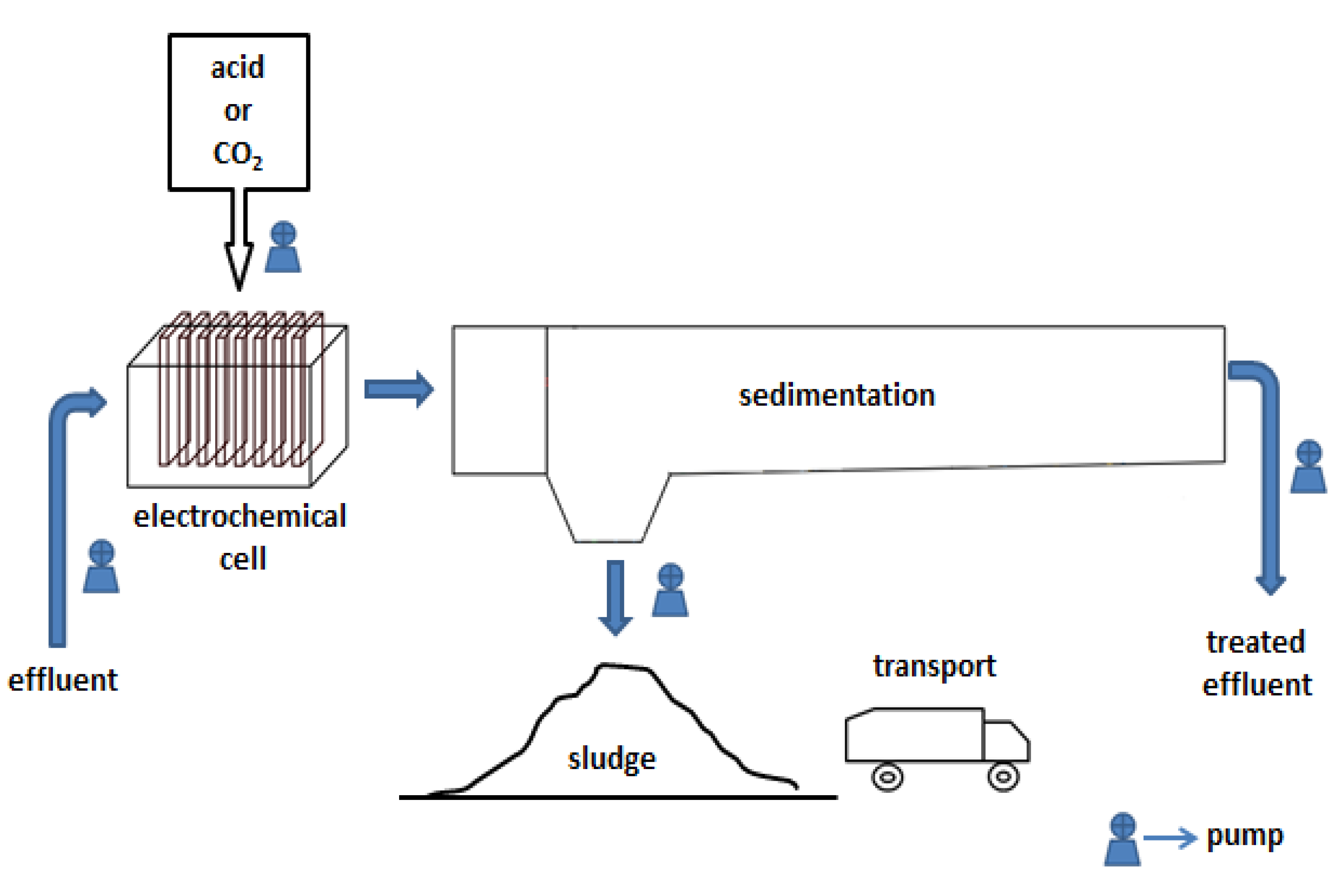

2.4. Electrocoagulation

2.5. Sedimentation unit

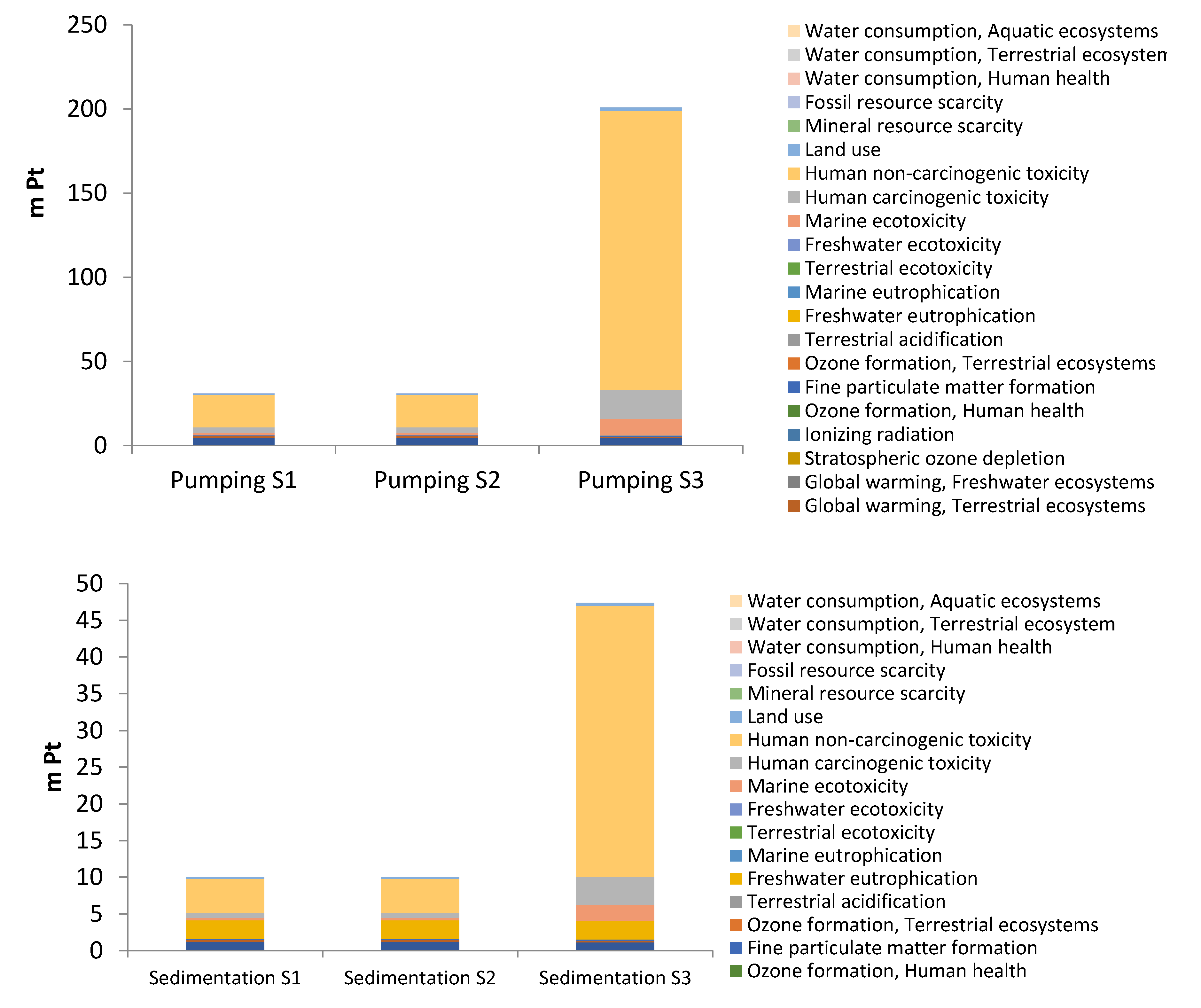

2.7. Pumping unit

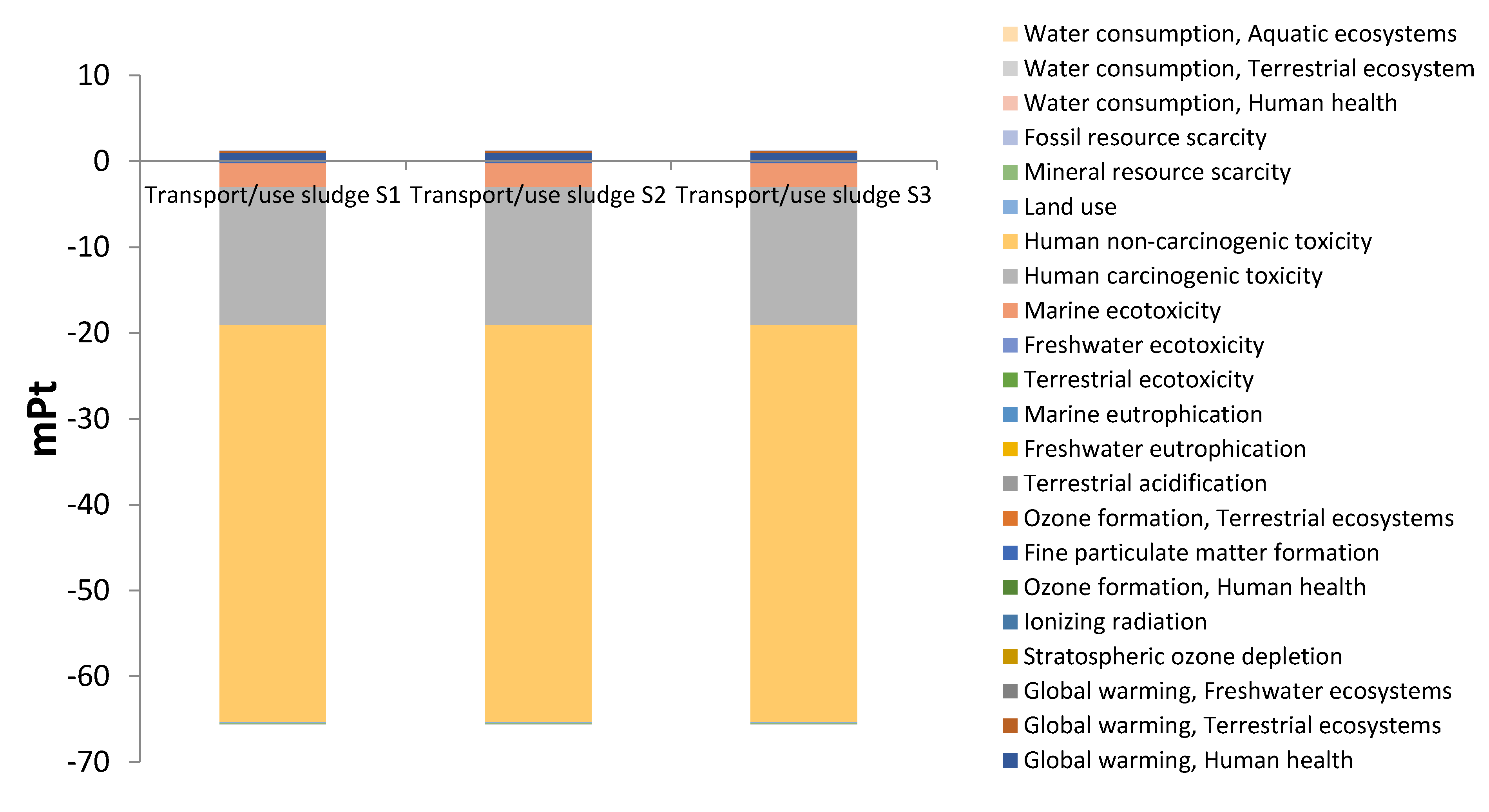

2.8. Transport and use of sludge

2.9. System constraints and uncertainties

Results and Discussion

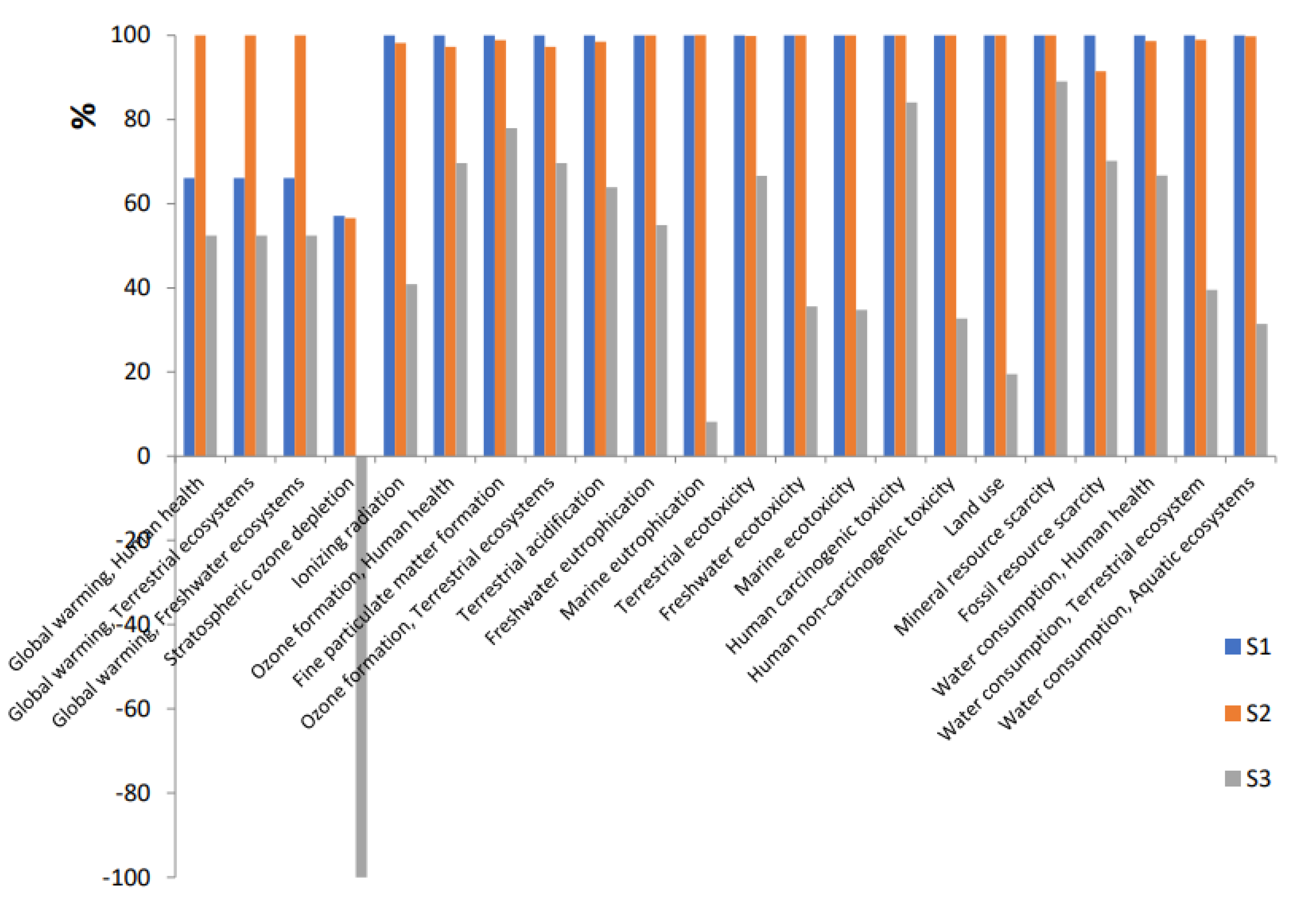

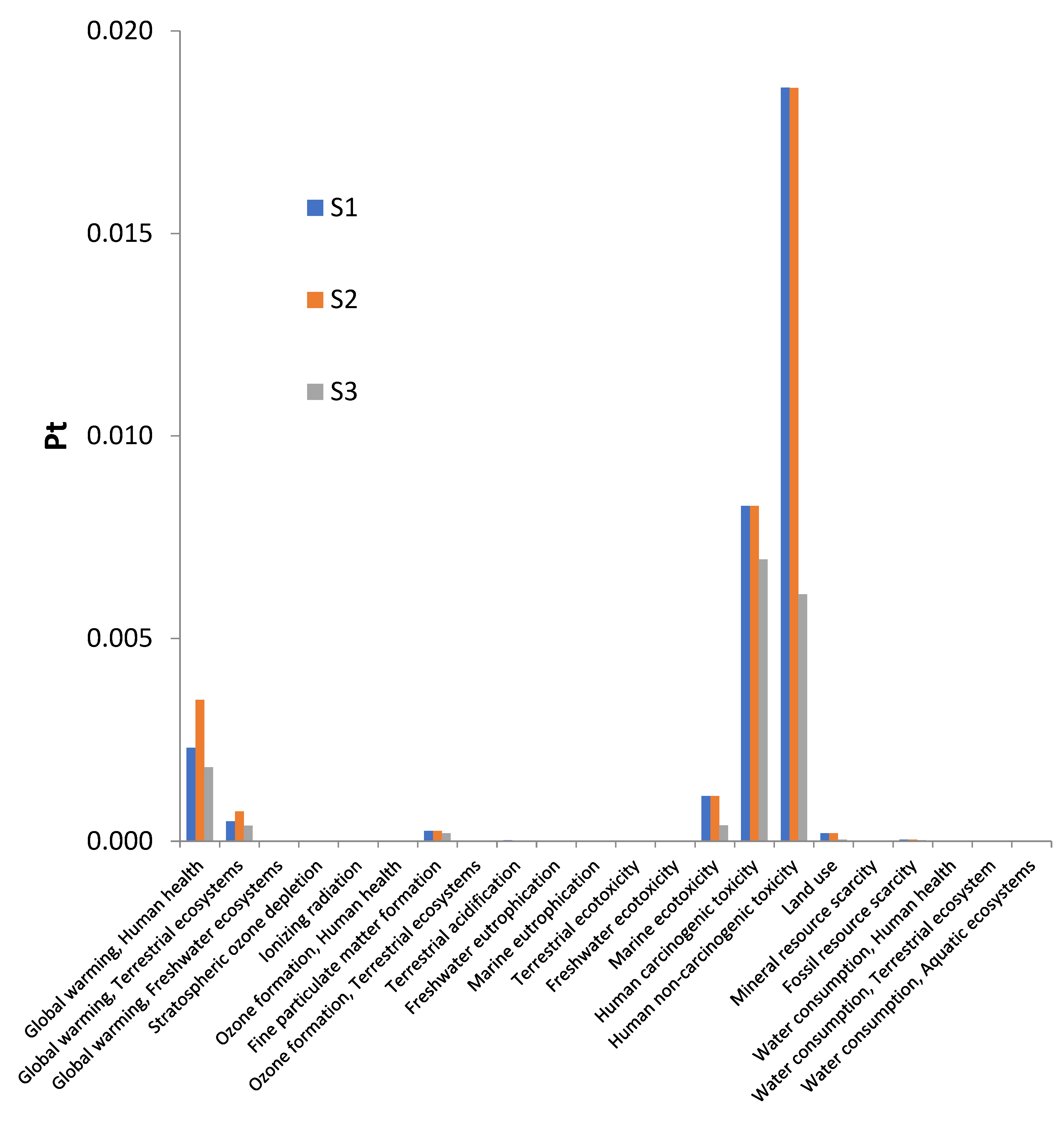

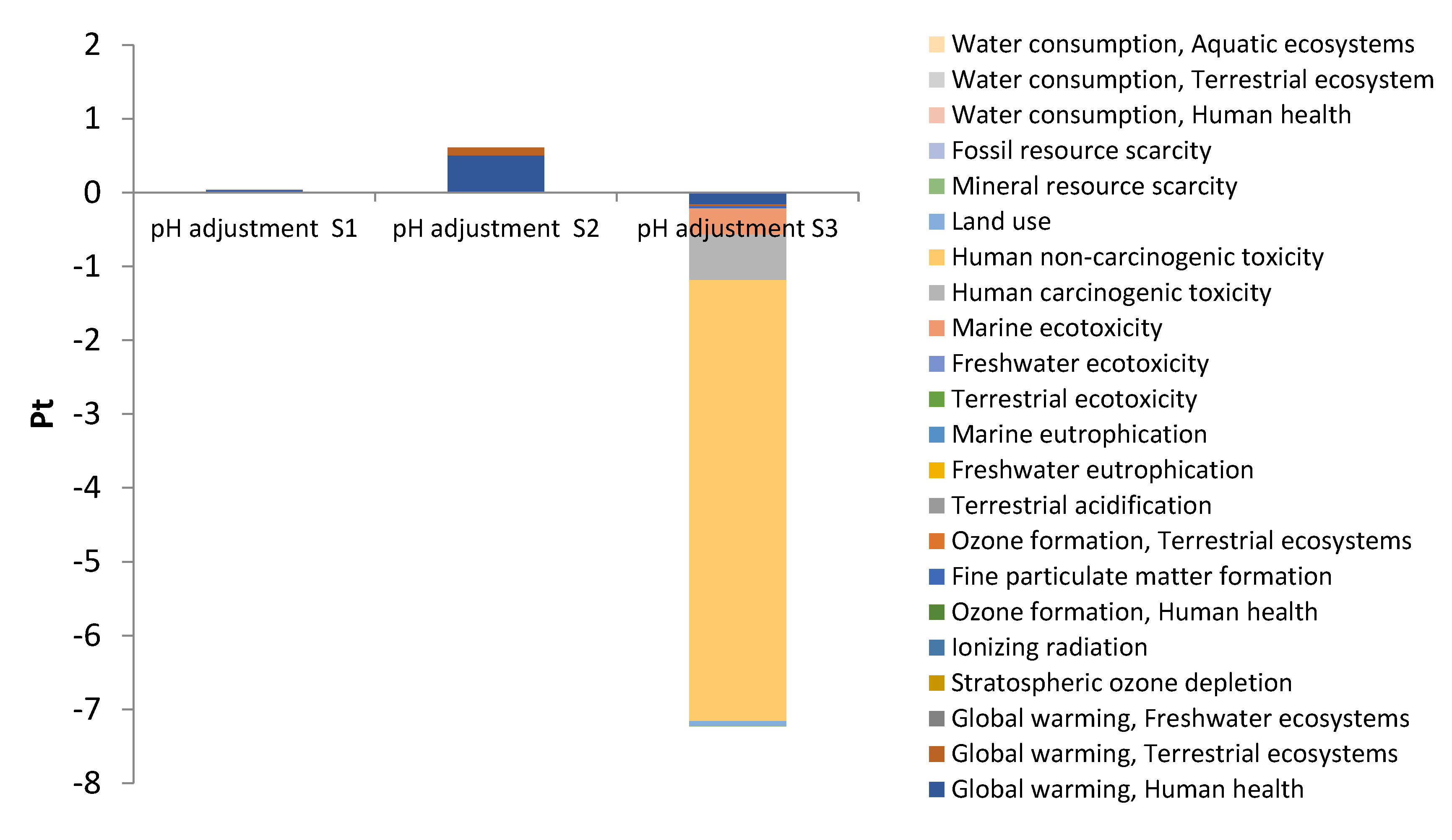

3.1. Environmental impacts assessed by scenario

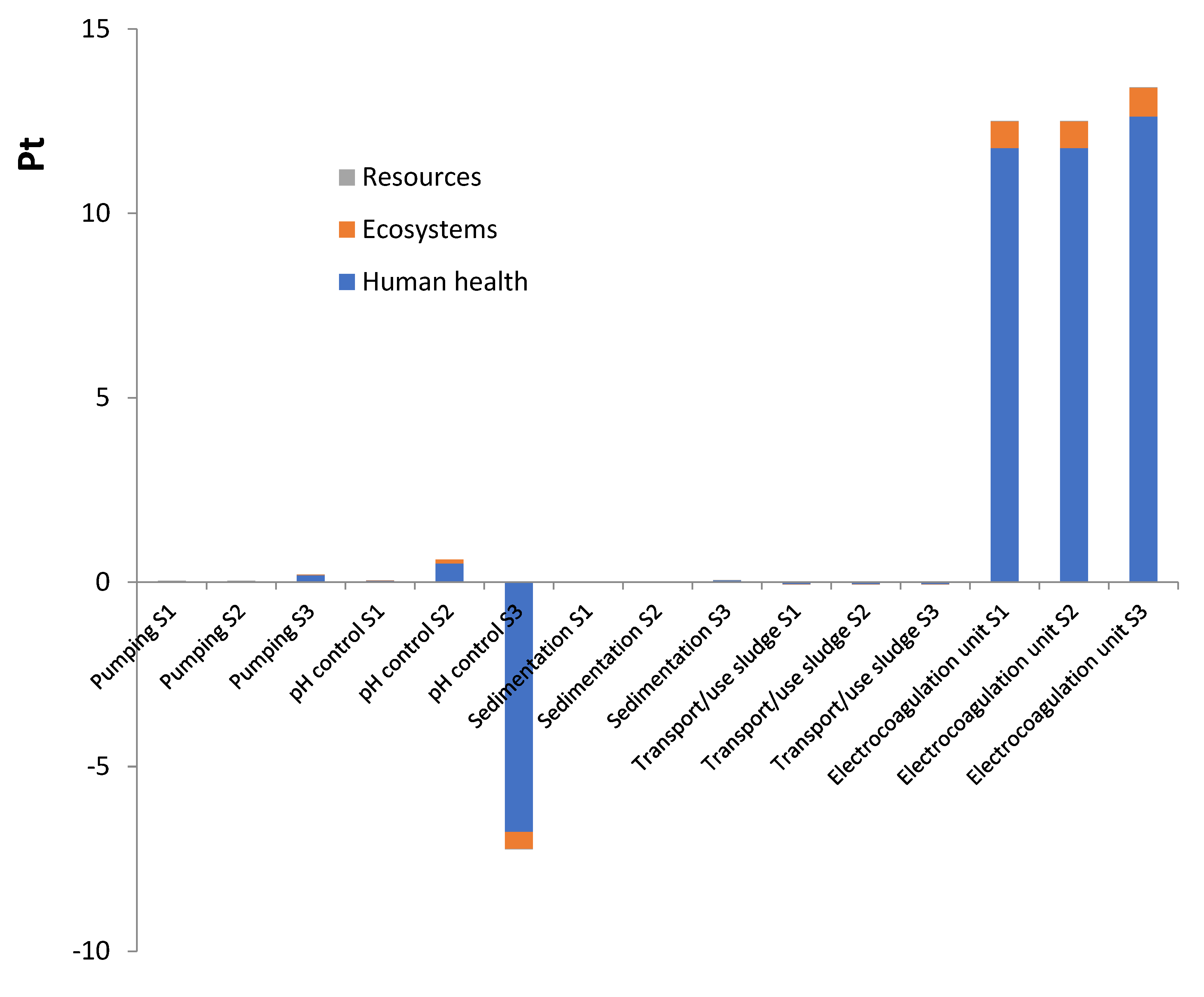

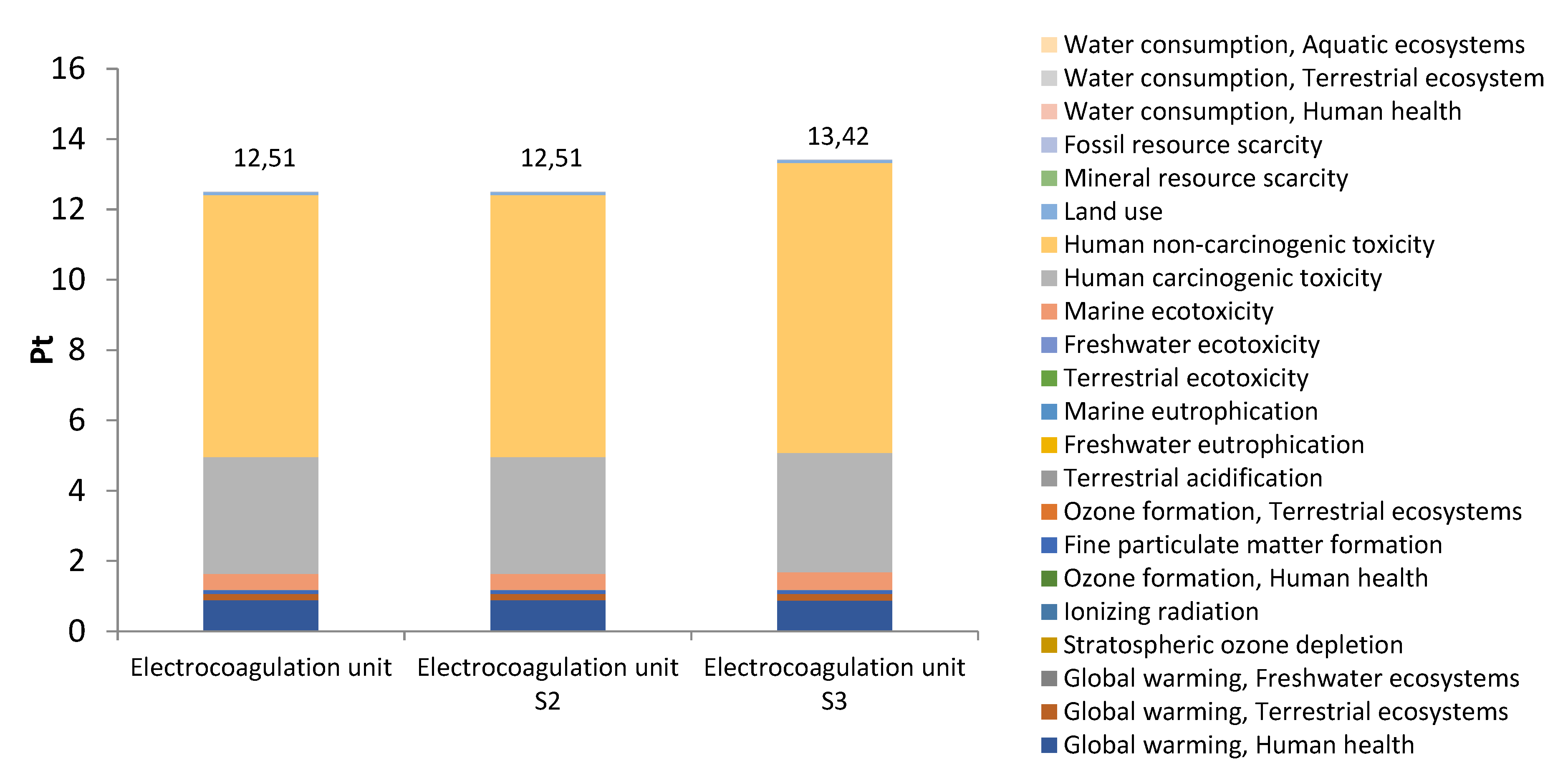

3.2. Environmental impacts by subsystems

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Santhi, V.M.; Periasamy, D.; Perumal, M.; Sekar, P.M.; Varatharajan, V.; Aravind, D.; Senthilkumar, K.; Kumaran, S.T.; Ali, S.; Sankar, S.; Vijayakumar, N.; Boominathan, C.; Krishnan, R.S. The global challenge of fluoride contamination: A comprehensive review of removal processes and implications for human health and ecosystems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Singh, R.; Arfin, T.; Neeti, K. Fluoride contamination, consequences and removal techniques in water: A review. Environmental Science: Advances 2022, 1, 620–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, E.J.; Wang, Y. A limestone reactor for fluoride removal from wastewaters. Environmental Science & Technology 2000, 34, 3247–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luna, M.D.G.; Warmadewanthi; Liu, J. C. Combined treatment of polishing wastewater and fluoride-containing wastewater from a semiconductor manufacturer. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2009, 347, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.C.; Huang, H.-C.; Chen, L.J. Treatment of semiconductor wastewater by dissolved air flotation. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2002, 128, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouiche, N.; Ghaffour, N.; Aoudj, S.; Hecini, M.; Ouslimane, T. Fluoride removal from photovoltaic wastewater by aluminium electrocoagulation and characteristics of products. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2009, 17, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeddine, A.; Bedoui, A.; Hannachi, A.; Bensalah, N. Removal of fluoride from aluminum fluoride manufacturing wastewater by precipitation and adsorption processes. Desalination and Water Treatment 2015, 54, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibikamal, V.; Torabian, A.; Janpoor, F.; Hoshyaripour, G. Fluoride removal from industrial wastewater using electrocoagulation and its adsorption kinetics. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 179, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyoda, A.; Taira, T. A new method for treating fluorine wastewater to reduce sludge and running costs. IEEE Transactions on Semiconductor Manufacturing 2000, 13, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.T.C. Fluoride in water: A UK perspective. Journal of Fluorine Chemistry 2005, 126, 1448–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, S.S.; Bersillon, J.-L.; Gopal, K. Removal of fluoride from drinking water by adsorption onto alum impregnated activated alumina. Separation and Purification Technology 2006, 50, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Liu, J.; He, W.; Xia, T.; He, P.; Chen, X.; Yang, K.; Wang, A. Dose–effect relationship between drinking water fluoride levels and damage to liver and kidney functions in children. Environmental Research 2007, 103, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Verma, P.K.; Sood, S.; Singh, M.; Verma, D. Impact of chronic sodium fluoride toxicity on antioxidant capacity, biochemical parameters, and histomorphology in cardiac, hepatic, and renal tissues of Wistar rats. Biological Trace Element Research 2022, 200, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, J.; Sun, W.; Shah, K.J. Review of fluoride removal technology from wastewater environment. Desalination and Water Treatment 2023, 299, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameri, N.; Yeddou, A.R.; Lounici, H.; Belhocine, D.; Grib, H.; Bariou, B. Defluoridation of septentrional Sahara water of North Africa by electrocoagulation process using bipolar aluminium electrodes. Water Research 1998, 32, 1604–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, A.; Nava, J.L.; Coreño, O.; Rodríguez, I.; Gutiérrez, S. Arsenic and fluoride removal from groundwater by electrocoagulation using a continuous filter press reactor. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 2113–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drondina, R.V.; Drako, I.V. Electrochemical technology of fluorine removal from underground and waste waters. Journal of Hazardous Materials 1994, 37, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-L.; Dluhy, R. Electrochemical generation of aluminum sorbent for fluoride adsorption. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2002, 94, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Chen, X.; Gao, P.; Chen, G. Electrochemical removal of fluoride ions from industrial wastewater. Chemical Engineering Science 2003, 58, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamjomeh, M.M.; Sivakumar, M. An empirical model for defluoridation by batch monopolar electrocoagulation/flotation (ECF) process. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2006, 131, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhao, H.; Ni, J. Fluoride distribution in electrocoagulation defluoridation process. Separation and Purification Technology 2007, 56, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcan Un, U.; Koparal, A.S.; Ogutveren, U.B. Fluoride removal from water and wastewater with a batch cylindrical electrode using electrocoagulation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2013, 223, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M.A.; Fuentes, R.; Nava, J.L.; Rodríguez, I. Fluoride removal from drinking water by electrocoagulation in a continuous filter press reactor coupled to a flocculator and clarifier. Separation and Purification Technology 2014, 134, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetilmezsoy, K.; Dehghani, M.H.; Saeedi, R.; Dalvand, A.; Heibati, B.; Askari, M.; Alimohammadi, M.; McKay, G. Elimination of natural organic matter by electrocoagulation using bipolar and monopolar arrangements of iron and aluminum electrodes. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 14, 2125–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.K.; Sharma, C.; Garg, U.K. Electrocoagulation: Promising technology for removal of fluoride from drinking water—A review. Biological Forum 2016, 8, 248–254. Available online: http://www.researchtrend.net (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- Nigri, E.; Santos, A.; Rocha, S. Electrocoagulation associated with CO₂ mineralization applied to fluoride removal from mining industry wastewater. Desalination and Water Treatment 2021, 209, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, A.R.A.; Mutiara, S.; Saputera, N. Advances in carbon control technologies for flue gas: A step towards sustainable industrial CO₂ capture. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2024, 123, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiron, J.; Normann, F.; Kristoferson, L.; Strömberg, L.; Gardarsdóttir, S.Ö.; Johnsson, F. Enhancement of CO₂ absorption in water through pH control and carbonic anhydrase—A technical assessment. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2019, 58, 14275–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkneh, A.A. Biogas impurities: Environmental and health implications, removal technologies and future perspectives. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangarnokolaei, R.; Rahmanian, N.; Ramezani, M.; Khataee, A. Environmental performance of electrocoagulation and ozonation for wastewater treatment: A life cycle assessment approach. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 287, 112345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.; Singh, P.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, S. Life cycle assessment of electrocoagulation processes: Energy consumption and global warming potential. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 408, 137137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J. Performance of aluminum electrodes in electrocoagulation for removal of heavy metals and phosphorus. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 139876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Zin, R.M. Electrocoagulation for wastewater treatment: Influence of electrode material and process parameters. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2018, 10, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, W.; Ye, Q.; Hou, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, P. Life cycle assessment of advanced wastewater treatment processes: Involving 126 pharmaceuticals and personal care products in life cycle inventory. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 238, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO. ISO 14040:2006. Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework, 2nd ed.; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Pell, R.; Tijsseling, L.; Palmer, L.W.; Glass, H.J.; Yan, X.; Wall, F.; Zeng, X.; Li, J. Environmental optimisation of mine scheduling through life cycle assessment integration. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2019, 142, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Eckelman, M.J.; Onnis Hayden, A.; Gu, A.Z. Comparative life cycle assessment of advanced wastewater treatment processes for removal of chemicals of emerging concern. Environmental Science & Technology 2018, 52, 11346–11358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opher, T.; Friedler, E. Comparative LCA of decentralized wastewater treatment alternatives for non-potable urban reuse. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 182, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellet, L.; Molinos-Senante, M. Efficiency assessment of wastewater treatment plants: A data envelopment analysis approach integrating technical, economic, and environmental issues. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 167, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corominas, L.; Foley, J.; Guest, J.S.; Hospido, A.; Larsen, H.F.; Morera, S.; Shaw, A. Life cycle assessment applied to wastewater treatment: State of the art. Water Research 2013, 47, 5480–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H.; Mondal, P. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of the arsenic and fluoride removal from groundwater through adsorption and electrocoagulation: A comparative study. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, L.S.; Goyal, H.; Mondal, P. Simultaneous removal of arsenic and fluoride from synthetic solution through continuous electrocoagulation: Operating cost and sludge utilization. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2019, 7, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, A.Y. Integration of electrocoagulation and solar energy for sustainable wastewater treatment: A thermodynamic and life cycle assessment study. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2025, 197, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Joshi, H. Utilization of electrocoagulation treated spent wash sludge in making building blocks. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2016, 13, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaniemi, K.; Tuomikoski, S.; Lassi, U. Electrocoagulation sludge valorization—A review. Resources 2021, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, R.; Liu, Y. Reuse of hazardous calcium fluoride sludge in ceramic products. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2013, 260, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.E.; Boncukcuoğlu, R.; Kocakerim, M.; Karakaş, İ.H. Waste utilization: The removal of textile dye (Bomaplex Red CR L) from aqueous solution on sludge waste from electrocoagulation as adsorbent. Desalination 2011, 277, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Gómez, C.; Rivera Huerta, M.L.; Almazán García, F.; Martín Domínguez, A.; Romero Soto, I.C.; Burboa Charis, V.A.; Gortáres Moroyoqui, P. Electrocoagulated metal hydroxide sludge for fluoride and arsenic removal in aqueous solution: Characterization, kinetic, and equilibrium studies. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2016, 227, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, A.K.; Samanta, A.N.; Ray, S. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solutions using calcined metal hydroxides sludge waste generated from electrocoagulation. Separation and Purification Technology 2006, 52, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, J.J.; Mena, V.F.; Betancor Abreu, A.; Rodríguez Raposo, R.; Izquierdo, J.; Souto, R.M. Use of alumina sludge arising from an electrocoagulation process as functional mesoporous microcapsules for active corrosion protection of aluminum. Progress in Organic Coatings 2021, 151, 106044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO 14044:2006. Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Bonton, A.; Bouchard, C.; Barbeau, B.; Jedrzejak, S. Comparative life cycle assessment of water treatment plants. Desalination 2012, 284, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; de Schryver, A.; Struijs, J.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe 2008: A Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method Which Comprises Harmonised Category Indicators at the Midpoint and the Endpoint Level; Report I: Characterisation; Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2009; Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/en/life-cycle-assessment-lca/recipe (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Zepon Tarpani, R.R.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts of advanced wastewater treatment techniques for removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs). Journal of Environmental Management 2018, 215, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhate, P.H.; Moradiya, K.K.; Patil, H.G.; Marathe, K.V.; Yadav, G.D. Case study on sustainability of textile wastewater treatment plant based on life cycle assessment approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 245, 118929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, M.; Rosenbaum, R.K.; Olsen, S.I. Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Carliell-Marquet, C.; Kansal, A. Energy pattern analysis of a wastewater treatment plant. Applied Water Science 2012, 2, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAMA. Resolução 430 (2011). Available online: http://www.suape.pe.gov.br/images/publicacoes/CONAMA_n.430.2011.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cashman, S.; Gaglione, A.; Mosley, J.; Weiss, L.; Hawkins, T.; Ashbolt, N.; Cashdollar, J.; Xue, X.; Ma, C.; Arden, S. Environmental and cost life cycle assessment of disinfection options for municipal drinking water treatment. Report; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2014. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_report.cfm?dirEntryId=298570 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Dalpaz, R. Avaliação energética do biogás com diferentes percentuais de metano na produção de energia térmica e elétrica; Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Vale do Taquari—Univates, Lajeado, Brazil, 2019. Available online: http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UVAT_1ab6a3b372faa4d5ed630f6c2515c049 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

| Scenario | Reagent | Function |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | HCl | pH control |

| S2 | CO2 from biogas | pH control |

| S3 | CO2 from biogas | pH control and energy source |

| In scenarios S1, S2 and S3, the generated sludge was used to manufacture building bricks. | ||

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 7.8 |

| Conductivity (µS.cm-1) | 6056.0 |

| Fluoride (mg.L-1) | 134.0 |

| Calcium (mg.L-1) | 4.4 |

| Sodium (mg.L-1) | 632.0 |

| Aluminum (mg.L-1) | <5.0* |

| Chloride (mg.L-1) | 1424.0 |

| Sulfate (mg.L-1) | 69.0 |

| Alkalinity carbonates and hydroxides (mg.L-1) | 0.0 |

| Alkalinity bicarbonates (mg.L-1) | 660.0 |

| Total phosphorus (mg.L-1) | 8.0 |

| COD (mgO2.L-1) | 106.0 |

| * Detection limit of the adopted analysis |

| Scenario | Input | Quantity | SimaPro® data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1, S2, S3 | Polyethylene (kg) | 2.4948E-4 | Polyethylene high density granulates (PE-HD), production mix, at plant RER | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Polyethylene molding (kg) | 2.4948E-4 | Injection molding (CA-QC) injection molding - APOS, S |

|

| S1, S2, S3 | Aluminum plate (kg) | 2.52 | Aluminum, cast alloy GLO market for APOS, S |

|

| S1, S2 | Electricity (kWh) | 2.25 | Electricity, low voltage (BR- south-eastern grid) market for electricity, low voltage APOS, S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kWh) | 2.25 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

| Functional unit: 1m3 of effluent; lifetime 25 years. | ||||

| Scenario | Input | Quantity | SimaPro® data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedimentation tank structure | S1, S2, S3 | Steel (kg) | 8.8E-4 | Iron and steel, production mix/US |

| S1, S2, S3 | HDPE (kg) | 5.8E-6 | Polyethylene high density granulates (PE-HD), production mix, at plant RER | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Concrete (m3) | 1.0E-5 | Concrete, normal (BR) market for concrete, normal - APOS, S | |

| Motor | S1, S2, S3 | Steel (kg) | 2.4E-8 | Iron and steel, production mix/US |

| S1, S2, S3 | Steel (kg) | 6.0E-9 | Iron and steel, production mix/US | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Cast iron (kg) | 1.8E-7 | Cast iron (GLO) market for - APOS S | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Aluminum (kg) | 5.4E-9 | Aluminum alloy, AlLi (GLO) market for - APOS, S | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Cooper (kg) | 4.6E-9 | Copper sheet, technology mix, consumption mix, at plant, 0.6mm thickness EU-15 S | |

| S1, S2 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.092 | Electricity, low voltage (BR- south-eastern grid) market for electricity, low voltage APOS, S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.092 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

| Functional unit: 1m3 of effluent; Lifetime of sedimentation tank: 100 years; Motor lifetime: 25 years. APOS (Allocation at the point of substitution) | ||||

| Scenario | Input | Output | Quantity | SimaPro® data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1, S2, S3 | Polyethylene (g) | 0.044074 | Polyethylene high density granulates (PE-HD), production mix, at plant RER | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Polyethylene molding (g) |

0.044074 | Injection molding (CA-QC) injection molding - APOS, S |

|

| S1 | HCl (L) | 2.627 | Hydrochloric acid, Mannheim process (30% HCl), at plant/RER Mass | |

| S2, S3 | Biogas (L) | 5.3966 | Biogas, from grass (CH) biogas production from grass – APOS S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kwh) | *15.04857 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

| Functional unit: 1m3 of effluent; lifetime: 25 years. *Excess energy in the process | ||||

| Scenario | Input | Quantity | SimaPro® data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pickup pump | S1, S2, S3 | Cast iron (kg) | 2.4E-5 | Cast iron (GLO) market for – APOS, S |

| S1, S2, S3 | Stainless steel (kg) | 2.2E-6 | Steel, stainless 304, flat rolled coil/kg/RNA | |

| S1, S2 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.203 | Electricity, low voltage (BR- south-eastern grid) market for electricity, low voltage APOS, S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.203 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

| Acid or biogas injection pump | S1, S2, S3 | Cast iron (kg) | 1.3E-7 | Cast iron (GLO) market for – APOS, S |

| S1, S2, S3 | Stainless steel (kg) | 9.1E-8 | Steel, stainless 304, flat rolled coil/kg/RNA |

|

| S1, S2 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.0156 | Electricity, low voltage (BR- south-eastern grid) market for electricity, low voltage APOS, S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.0156 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

| Sludge pump | S1, S2, S3 | Cast iron (kg) | 2.8E-7 | Cast iron (GLO) market for – APOS, S |

| S1, S2, S3 | Stainless steel (kg) | 1.9E-7 | Steel, stainless 304, flat rolled coil/kg/RNA |

|

| S1, S2 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.0165 | Electricity, low voltage (BR- south-eastern grid) market for electricity, low voltage APOS, S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.0165 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

| Treated effluent pump | S1, S2, S3 | Cast iron (kg) | 2.4E-5 | Cast iron (GLO) market for – APOS, S |

| S1, S2, S3 | Stainless steel (kg) | 2.2E-6 | Steel, stainless 304, flat rolled coil/kg/RNA |

|

| S1, S2 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.183 | Electricity, low voltage (BR- south-eastern grid) market for electricity, low voltage APOS, S | |

| S3 | Electricity (kWh) | 0.183 | Electricity, low voltage (CH) biogas, burned in micro gas turbine 100kWe - APOS, S | |

|

Pipe line |

S1, S2, S3 | PVC pipeline (m) |

3.0983E-5 | PVC pipe E |

| Functional unit: 1m3 of effluent; pumps lifetime: 25 years; pipes lifetime: 100 years (30m; 100mm). | ||||

| Scenario | Input | Output | Quantity | SimaPro® data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1, S2, S3 | Transport (t.km) | 0.360045 | Transport, truck 10-20t, EURO5, 80%LF, empty return/GLO Mass | |

| S1, S2, S3 | Sludge (kg) | 7.41 | Clay (RoW) market for clay - APOS.U | |

| Functional unit: 1m3 of effluent; distance 40.5km; t.km – tons.km | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).