1. Introduction

Silvopastoral systems integrate trees, forage and livestock on the same land for mutual benefit [

1]. Their investigation and optimization are challenged by the numerous interlinked, concurrent and cause-effective processes and feedbacks [

1,

2,

3]. In outdoor pig production on forage pasture, rather low nitrogen (N) digestion utilisation efficiency (NUE) of 10-44% [

4] against high N input in feed creates large surplus of soil nitrate from manure deposited unevenly and non-randomly [

5,

6]. This creates N “hotspots” since the pigs’ rooting and trampling behaviour destroys the pasture [

6] which would have otherwise utilized the soil nitrate. As a result, high soil nitrate leaching has been reported, easily exceeding 200 kg N ha

−1 in a year [

7]. Field methods describing N flows and nitrate leaching to study, monitor and optimize such systems are precise but costly and time consuming, while the added value of remote sensing remains elusive.

Large-scale and freely available satellite data from, e.g., MODIS, Landsat or Sentinel missions have been suggested as useful for large-scale assessments [

2,

8,

9,

10], but are unable to contribute directly and accurately to following the N dynamics of silvopastoral systems, mostly due to their coarse spatial resolution. For analyses of high spatio-temporal scales, UAV data are more useful. For instance, de Lima et al. [

11] used multispectral UAV imaging with a high cartographic scale to derive vegetation indices and predict aboveground biomass for rice intercropped with exotic grass in Brazil by linear regression models. While no animals were involved to potentially confound the spectral signal, their study showed the advantages of employing UAV-based multispectral images to map at high detail the spatial and temporal distribution of mixed-biomass complex systems. Chen et al. [

12] estimated Leaf Area Index (LAI) from UAV multispectral images of wheat fields in Australia to suggest unsupervised (very little input from human) and plot-scale crop phenotyping. Their study linked the LAI estimates with process-based (radiative transfer) modelling for a rapid, accurate and non-destructive phenotyping of growth rate. Process-based models provide a balance between system complexity, model parameterization, and project budget as they can simulate many processes in the system based on physical principles.

Previous studies have shown improved prediction of aboveground traits such as crop yield by integrating UAV-based estimates of not only LAI, but also leaf N concentration or plant height, with process-based model, e.g., SWAP [

13], AquaCrop [

14], DSSAT [

15], WOFOST [

16], SAFY [

17], and RiceGrow [

18]. Assessment of nitrate leaching from agricultural soils aided by remote sensing and model are much sparser as the process is belowground and also the models require parameterization beyond crop to simulate realistically the evapotranspiration and soil water transport needed to estimate nitrate leaching. An earlier study suggested integration of not only LAI estimated by remote sensing data, but also soil physical and hydraulic variables estimated by geostatistics and feeding the Daisy process-based model as a plausible approach to not only reveal complex and dynamic patters of water transport phenomena and nitrate leaching, but also handle uncertainties in space and time for further research and decision making [

19]. Manevski et al. [

20] used Daisy to simulate the spatial distribution of nitrate leaching in silvopastoral systems with poultry and willows using largely approximated LAI distribution and not considering soil spatial heterogeneity. Nitrate leaching is known to have leptokurtic distribution (thicker tails) with extreme data values (outliers or high variability) compared to a normal distribution due to the high spatio-temporal variability of both soil nitrate and water contents [

20,

21]. Schuster et al. [

22] integrated digital methods involving tractor-mounted multispectral sensor, satellite data from Sentinel-2, with the PROMET model and georeferenced measurements of subsoil nitrate stocks to reveal explicit spatial variability for large croplands in Germany. These patterns might easily be complicated by trees which utilise soil nitrate and have shown potential to reduce nitrate leaching in arable cropping [

3,

23], and outdoor pig and poultry farms [

20,

24]. Especially before the leaching season peaks, rapidly growing and pruned trees might absorb nitrate from the deeper soil layers, which was not the case for grass [

25]. From an agro-engineering perspective, positioning resources – hut, feed trough – influences the animal behaviour on where they distribute manure, with tendency for more even distribution in tree area if available [

25]. Up to the authors’ knowledge, no studies have been conducted to investigate the role of affordable and simple remote sensing in quantifying explicit spatio-temporal distribution of nitrate leaching in complex silvopastoral systems.

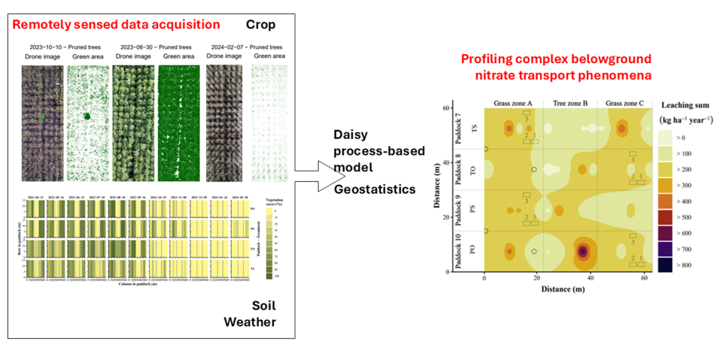

The main aim of this study was twofold, to firstly integrate remote sensing and process-based model for simulating the water balance of pasture paddocks on sandy soils with outdoor pigs distributed in different resource position and tree treatments and secondly, quantify the spatio-temporal distribution of nitrate leaching in the paddocks. The specific objectives were to 1) delineate LAI dynamics based on UAV true-colour imagery, 2) integrate the LAI dynamics to parameterize the Daisy model and simulate the paddocks’ water balance, 3) estimate nitrate leaching by the percolation-weighted method using the simulated percolation and the measured nitrate concentrations, 4) statistically analyse the spatial and the temporal variability of nitrate leaching data within paddocks and between treatments and 5) calculate paddock N mass balances consisting of inputs and outputs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Setup and Farm Data

Field experiment was conducted on a commercial farm with sandy soil in Denmark on four paddocks, each measuring 63×15 m and each hosting one lactating sow and its piglets at a time. The middle zone of each paddock– a third of the total area– contained poplar trees hybrid O.P.42,

P. maximowiczii ×

P. trichocarpa planted in 2011 at 2-3 m spacing (1,900 trees ha

−1;

Figure 1). In April 2022, the trees were either cut to 2 m height, with the resulting biomass chipped and the wood chips placed on the soil surface beneath the trees (hereafter denoted as pruned, P) or left uncut (i.e., tall, T), with each treatment occupying two paddocks. The rest of the paddock area was planted with spring barley with undersown grass-clover (year 1) followed by three batches of sows in 2023-2024 (year 2) (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix A). The historical management on this farm followed a crop rotation with sows every second year, alternating with spring barley undersown with grass-clover. In the year before measurements, four batches were managed: in the first two, huts and feed were placed on opposite sides of the trees; in the last two, both were on the same side

For the experiment, grass-clover grew during the winter 2022-2023 before sows of the crossbreed Nordic Landrace x Yorkshire (TN70 by Topigs Norsvin) were introduced to the paddocks in three batches, starting from mid-April, late July and early November in 2023, respectively and stayed in the paddocks for 11 weeks, one week prior to farrowing and ten weeks during lactation (

Figure 2). Within this period, resource position treatment was introduced, i.e., feed and hut positioned either on the same (S) or opposite side (O). Farm data needed for N balance calculation included eliminated and weaned piglets (number and weight), feed amount (by feeding curve for sows), feed ingredients and straw usage. Piglet’s feed consumption could not be determined on paddock level since they were moving between paddocks. Yields of barley grain and straw were estimated from previous farm records.

2.2. Remote Sensing Data Collection and Analyses

Remote sensing field campaigns with UAV were conducted on four occasions in 2023 and six occasions in 2024. The UAV was

DJI Mini 3 Pro with 46 Megapixels camera flown over the paddocks to collect true colour (RGB) images from the entire field containing the paddocks. The RGB images after each flight were downloaded on a local PC. For each date and pruning regime, one image was chosen and cropped to show the tree area only. To retain the area covered by green leaves only, a semi-physical analysis was conducted by converting the RGB values of the photos to hue saturation value (HSV) and applying thresholds. These thresholds were found by comparing colour values of green leaf area and of other areas typically branches and surrounding soil, which were chosen manually using GIMP-GNU Image Manipulation Software (v2.10.38). These initially chosen thresholds were applied to three photos representing different seasons and were varied to visually assess the fit. The discriminated green leaves pixels were used to obtain canopy cover (CC;

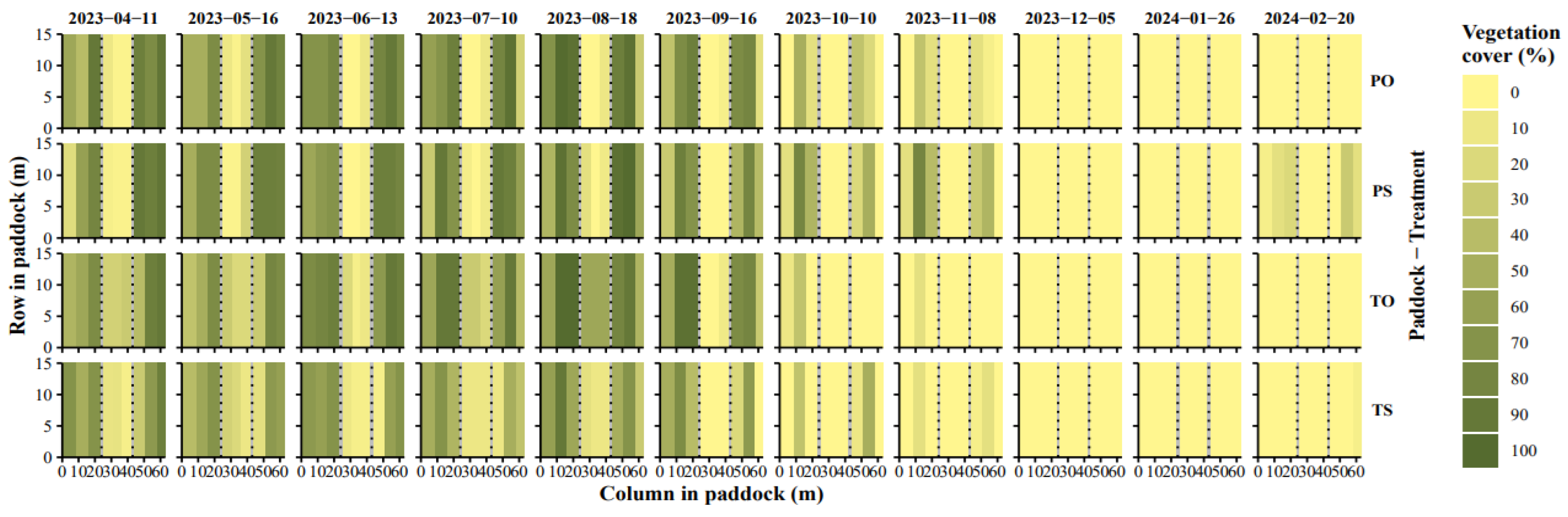

Figure 3).

From April 2023 and once a month, the soil surface condition in the paddocks was assessed visually for the subzones (

Figure 1) by estimating the area fraction of soil rooted either deep (> 10 cm) or shallow (< 10 cm), of bare soil or of soil with vegetation cover, including cultivated grass, clover or weed [

26]. Since images were available from April 2023 to April 2024 only, CC was assumed the same in 2022 with 20 % reduction for pruned trees to mimic pruning in April 2022. The CC was used to determine LAI using the Beer’s law:

, with canopy extinction coefficient (

k) of 0.5 [

27,

28].

2.3. Soil Water Sampling and Water Balance Modelling

In each paddock, 51 ceramic suction cups were installed in April 2022 at 1 m depth (

Figure 1). The aim was to cover as much as feasible the spatial variation of soil nitrate destined for leaching. The sampling interval was two weeks (

Figure 2). Soil water samples were collected from November 2022 before pig introduction in spring 2023 by applying a negative pressure of about 70 kPa usually 1-3 days before sampling. Due to economic reasons, the three samples of each row had to be pooled, before the nitrate concentrations were determined colorimetrically (Best, 1976) using a Technicon Auto Analyzer. If a cup was malfunctioning, collected water from the remaining cups was used. This left 17 data points per paddock (i.e., 68 data points for the entire study field with four paddocks) on soil nitrate.

The water balance at each location with measured soil nitrate in each paddock was modelled with the Daisy model version 5.92; [

29]. It is a one-dimensional, deterministic and detailed process-based model describing water/energy flows in the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum. In brief, the water fluxes considered include precipitation (gain), irrigation, if any (gain), evapotranspiration (loss) as well as surface run-off, if any (loss), as surface fluxes as well as deep percolation (i.e., drainage; loss) and capillary rise (gain) as soil fluxes. Water input used for wallowing, a behavior critical for thermoregulation, sunburn, skin care, and overall comfort of pigs, was not included as it was limited in space and not quantified. The dynamics of soil water, and thus the drainage, are modelled by a numerical solution of the Richard’s equation. Reference evapotranspiration is calculated according to the FAO Penman-Monteith equation [

30]. Further details can be found in Hansen et al. [

29].

The model was run from 1 April 2022 to 1 April 2024 with the required inputs of daily weather data and information on soil, plant and field management. Weather data included daily precipitation (mm), air temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), wind speed (m s

−1), and global radiation (MJ m

−2) obtained from the national grid database of the Danish Meteorological Institute. Precipitation was corrected for uncertainties caused by evaporation, wind and wetted surfaces [

31]. Vapour pressure was calculated from relative humidity and air temperature according to FAO standards [

32].

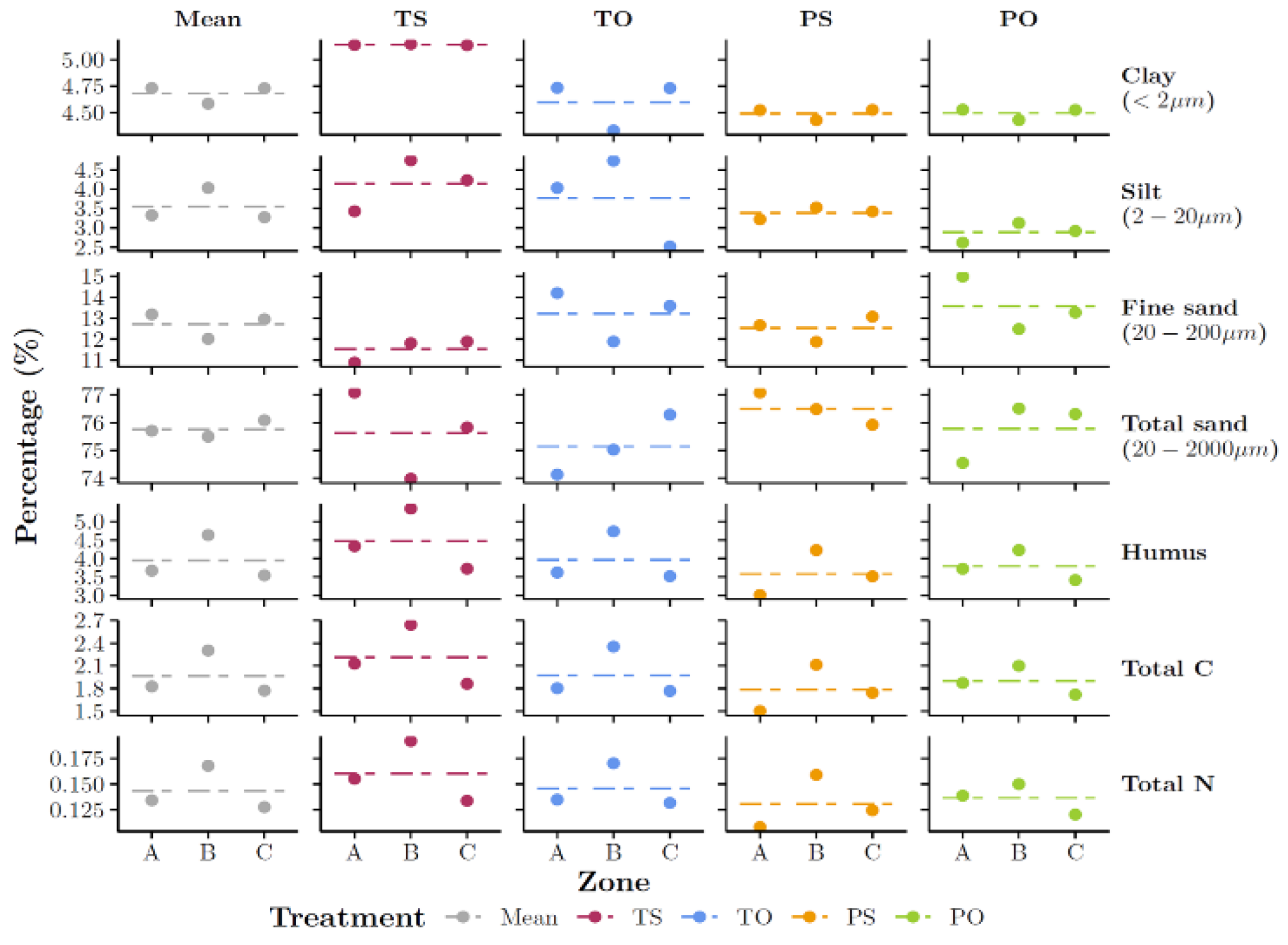

For the soil parameterization, soil texture and organic matter (OM) content were derived from topsoil (0-20 cm) samples, and for the subsoil (20-100 cm;

Figure A2 in

Appendix A), values for 30-100 cm soil were obtained from 3D map of the soil texture of Denmark at 10 m resolution [

33]. Soil texture and OM content over the whole experimental area were markedly similar, depicting high degree of homogeneity. Clay, silt, sand and OM contents were, respectively, 4.7, 6.2, 85.2 and 3.9 %, C/N ratio of 13.7, bulk density of 1.41 g cm

-3, for the topsoil, and corresponding values for the subsoil of 6.4, 3.7, 89.4, 0.5, 13 and 1.43. The soil hydraulics were described by Brookes and Corey inverse model having topsoil values for saturated hydraulic conductivity and soil water of 10.1 cm h

-1 and 35%, and soil moisture at field capacity and wilting point of 18 and 9%, respectively, whereas values for the subsoil were 10.6 cm h

-1, 37.1 %, 21 % and 3.7 %. Soil surface evaporation factor in Daisy (

EpFac) was reduced by 35 % in the paddocks with pruned trees compared to the tall trees to account for mulching with wood chips conserving soil water content and reducing soil evaporation [

34,

35].

For plant information, the “permanent” vegetation module described by Boegh et al. [

36] was used to simulate the poplar zone with plant height set to 5.3 and 18.3 m for pruned and tall trees, respectively. The LAI of the poplars determined from the UAV imagery for pruned and tall trees was given as an input to Daisy. For the grass zone, the management of the crop was specified with historical data on sowing, ploughing, seed bed preparation and harvest of the previously grown spring barley; LAI of the grass-clover grazed by the sows was estimated as a start value of 2 in April based on literature [

37,

38] multiplied by the observed fraction of vegetation cover. Simulations were set for each pruning treatment in the tree zone and each vegetation cover observation subzone in the grass zone. This degree of detail was chosen to account for the high variation in vegetation cover.

2.4. Nitrate Leaching Calculation

The measured soil nitrate concentrations at each pooled location and the respective modelled daily percolation were combined to determine daily leaching values according to an improved trapezoidal rule method by Lord and Shepherd [

39], i.e., instead of assuming measured concentrations to represent the average flux concentrations, the concentrations were interpolated and weighted by the simulated daily percolation [

20,

40]. The obtained daily nitrate leaching was accumulated to yearly sums from 1 April to March 31 for years 2022-2023 (year 1) and 2023-2024 (year 2).

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Nitrogen Balances

The annual nitrate leaching data based on 68 observations across all four paddocks were spatially interpolated for each year by ordinary kriging (prediction and variogram) using the krige function from gstat R package on a 1×1 m grid. The results were used to show the spatial variation in nitrate leaching and calculate average leaching for each zone in each paddock and year, and for each paddock. The effects of treatment and zone on annual nitrate leaching were analysed with in a generalized linear mixed model. For effect of zones and treatments in time, the daily leaching was analysed with a generalized additive model (GAM) with smooth functions to link predictor variables to the response variable. Here, different group levels were fitted with varying functions.

For each paddock, surface N balance for years 1 and 2 was calculated as the difference between inputs and outputs [

20,

24,

41]. Inputs were feed for sows and piglets, sow weight loss, straw for bedding, seeds for barley and grass-clover fixation by clover and atmospheric deposition [

24]. Outputs were produced piglets, harvested barley grains and straw. An overview of the used data and factors is shown in

Table A1 in

Appendix A. Soil N balance was calculated at higher detail i.e., for treatment by subtracting from the surface balance the sum of N outflows from the 1m soil column, i.e., leaching, ammonia volatilization and denitrification; the flat soil surface ensured no N losses via surface runoff.

3. Results

3.1. Weather and Canopy Characteristics

The two study years were similar to the 10-year average values, with slightly lower precipitation in year 1 (

Table A2 in

Appendix A). The water balance of the study period was deemed to represent the climatic normal. Poplar LAI values estimated from the UAV imagery – and given as input to the Daisy model – varied seasonally and this was depicted well by the data (

Figure 4), with the highest values of 9.2 and 7.7 in tall and pruned trees, respectively. In the grass zone, LAI decreased in autumn 2023 whereafter it remained low. Grass-clover CC visual assessments for year 2 (April 2023 to April 2024) supported the grass zone LAI by showing high CC before and during paddocks animal occupation for the summer months before decreasing sharply in late autumn (

Figure A3 in

Appendix A).

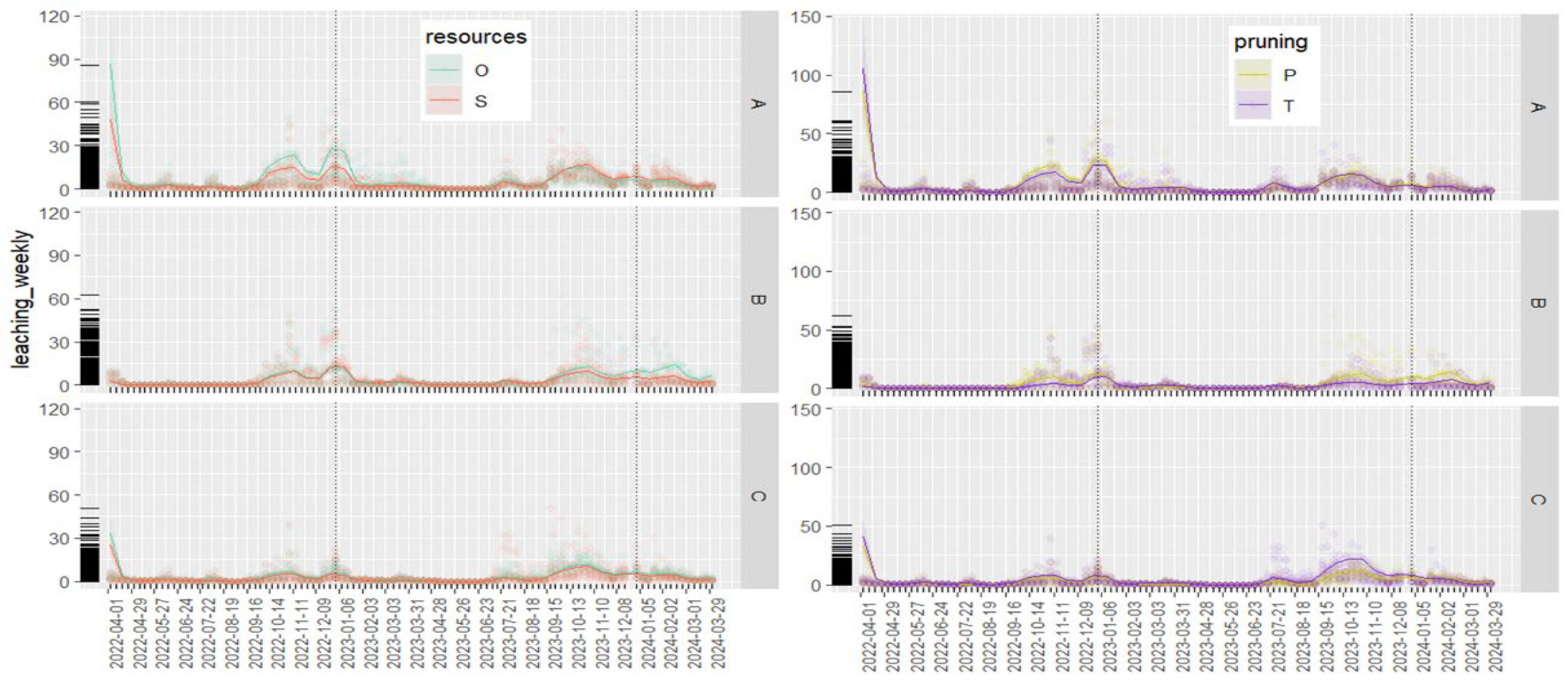

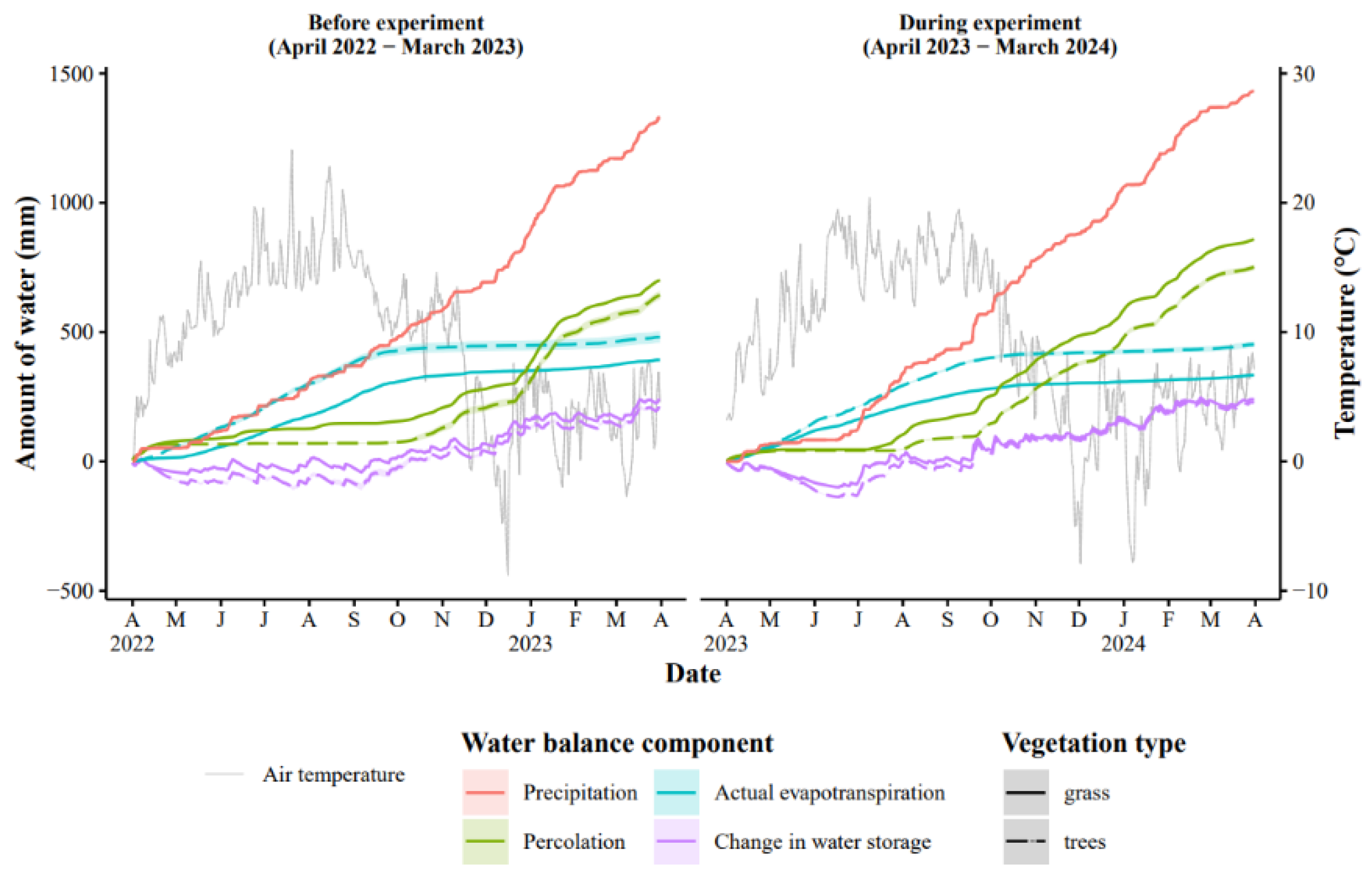

3.2. Simulated Water Balance for the Experimental Paddocks

The hydrological years 2022/23 (year 1) and 2023/24 (year 2) were comparable in air temperature and precipitation, slightly wetter in year 2 compared to year 1 (

Figure 5). As a result, the Daisy model showed more delayed percolation season in the winter of year 1, before the pigs were introduced in the paddocks, compared to year 2 when percolation was more gradual and overall higher. Percolation was lower in the tree zone, 643 and 751 mm in years 1 and 2, respectively, compared to the grass zone, i.e., 701 and 859 mm. Simulated actual evapotranspiration was on average 22 % higher for the poplars than the grass. The change in water storage was 234 mm on average across years and vegetation zones. These water balance components provide information on the transport factor for nitrate leaching.

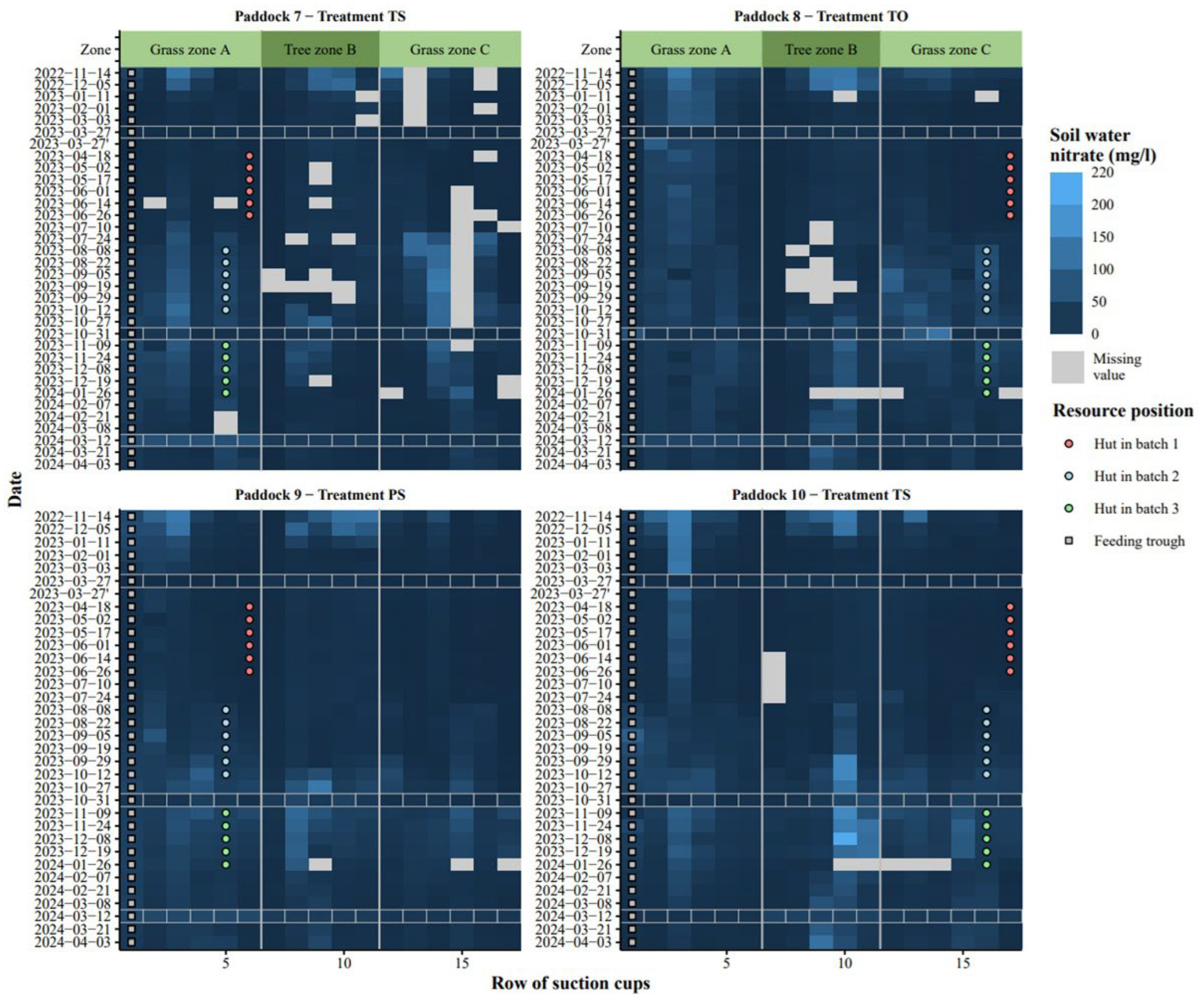

3.3. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Soil Nitrate

The measured soil nitrate concentrations varied markedly from 0.1 to 158 mg l

-1 (

Figure 6). Their lower quartile, median and upper quartile were 7.2, 14.01 and 28.8 mg l

−1, respectively, with few occasions above 100 mg l

−1. Shown spatio-temporarily, their dynamics clearly showed peaks, i.e., hot spots in autumn and winter, and this was more evident in the grass compared to the tree zone, except for the S treatment where high soil nitrate concentrations were measured in the tree zone in autumn-winter of 2024.

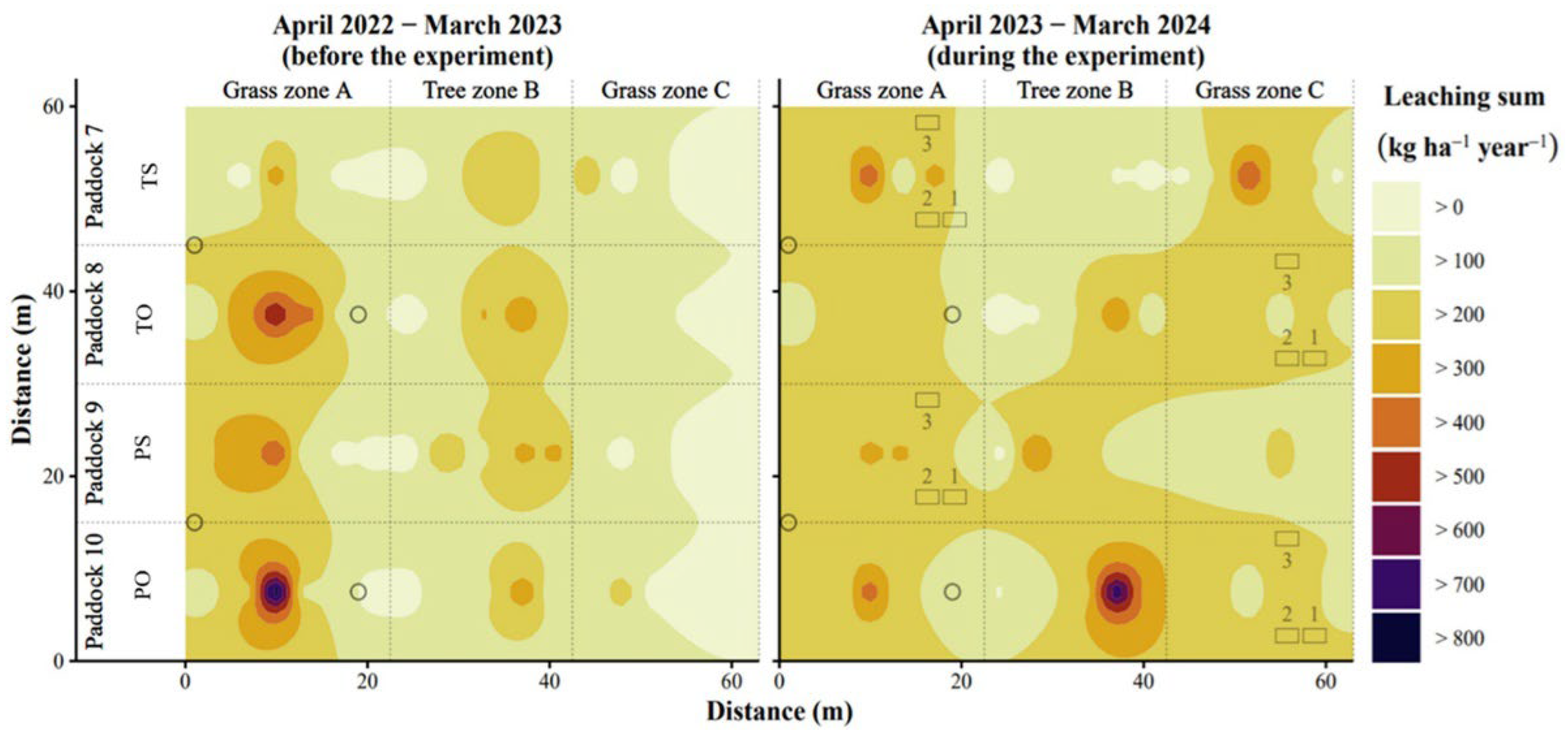

3.4. Spatio-Temporal Maps of Nitrate Leaching

Spatio-temporal delineation (kriging) of nitrate leaching depicted the observed soil nitrate, and ranged similarly between the two years, i.e., 9 to 860 kg N ha

-1 in year 1, and 7 to 779 kg N ha

-1 in year 2 (

Figure 7). On average from these results, nitrate leaching was higher in year 2 (206-242 kg N ha

-1) during paddocks animal occupation than in year 1 (144-194 kg N ha

-1) representing crop husbandry. Paddock averages in year 2 were highest for the PO (242 kg N ha

-1). This was contrary to expectations for O treatment to depict, on average, lower nitrate leaching compared to the S treatment.

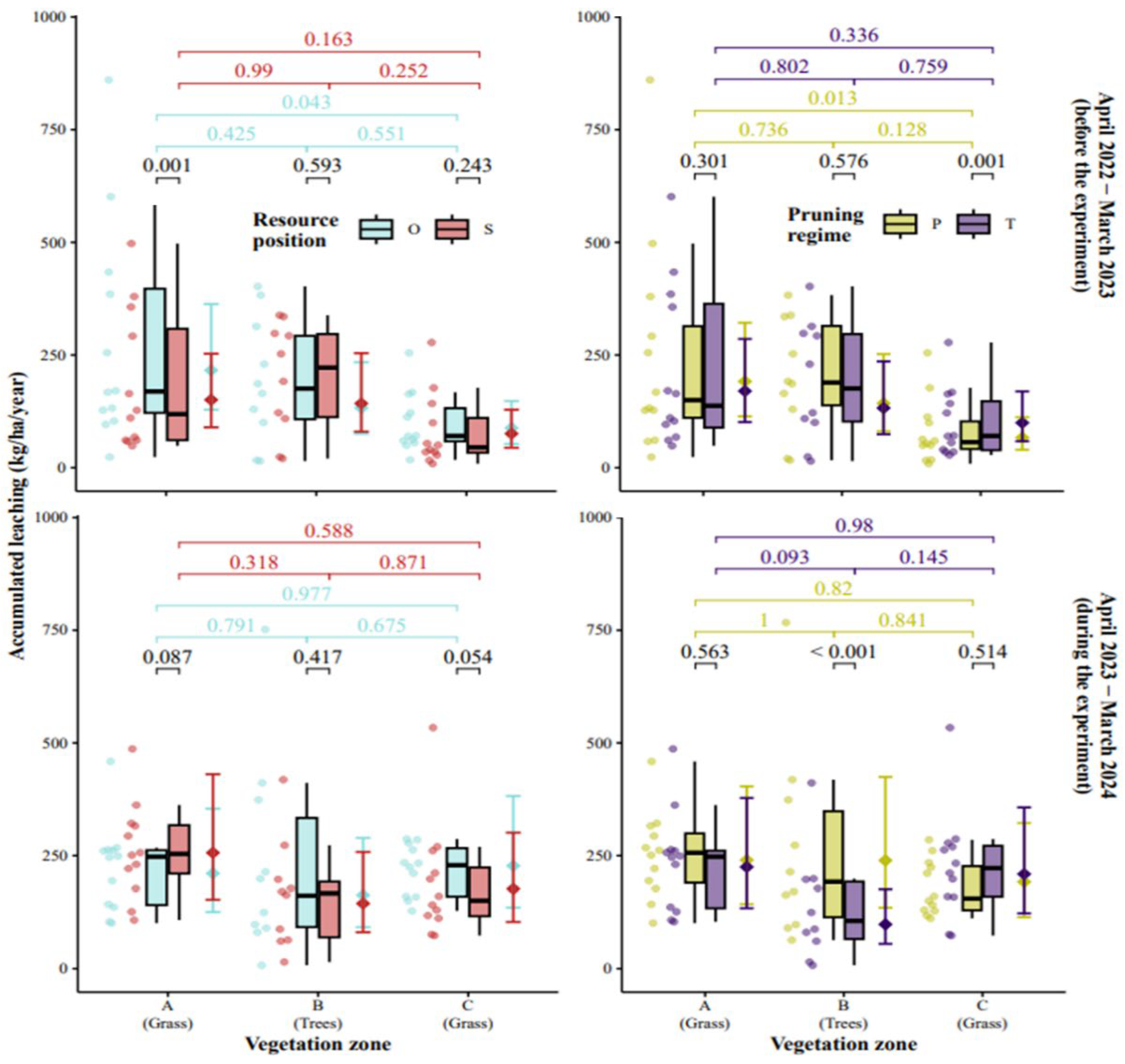

Also, according to the GLM, the effect of zones depended on the two treatment factors and the observation year as well (

Table A3 in

Appendix A). Model estimated accumulated leaching averaged for the paddocks in year 2 (the year with pig occupation) were higher with pruned trees (234 kg N ha

-1) than tall trees (177 kg N ha

-1) and slightly higher with hut on opposite (200 kg N ha

-1) than on the same side (192 kg N ha

-1). For year 1 (the year with crop husbandry), the values were 15-20% lower compared to year 2 (results not shown). The statistical comparison for each zone in each paddock revealed a significant increase in average annual nitrate leaching in the tree zone of pruned trees (P) compared to tall trees (T) in both years (

Figure 8). This could indicate pruning to reduce the soil nitrate uptake by the poplar trees but also caused by differences in pig behaviour not studied here. The only significant difference between resource position treatments appeared in the year with crop husbandry (year 1) with higher leaching in O compared to S in grass zone A. This result is not readily explained as all four paddocks had undergone identical management in the years leading up to pig occupation in year 2. In the year with pig occupation (year 2), in the grass zone A, the average annual leaching tended (P=0.087) to be higher when the hut was placed on the same side as feed (S) instead of the opposite side (O). In contrary, in the grass zone C, the average annual leaching tended (P=0.054) to be higher in O compared to S. When analysing leaching at higher temporal resolution with the GAM, weekly nitrate leaching data revealed comparable dynamics between the treatments in year 1 when the magnitude was larger in O compared to S, in the grass zone having the feed and water, (

Figure A4 in

Appendix A). The effect of tree management was less evident on the weekly soil nitrate leaching, but values in the tree zone were clearly larger for P compared to T in the leaching season 2023-2024.

3.5. Nitrogen Mass Balance for the Experimental Paddocks

The surface N balances is shown in

Table 1- it refers for the entire area occupied by the four paddocks since the input mass flows of N did not differ between paddocks. Annual differences were, however, present and in year 1 (before the experiment), barley production with grass-clover atmospheric N fixation was the largest input and harvested grains as the main output, leaving about -45 kg N ha

-1 surplus at the soil surface. In year 2 (the year with sows), feed contributed 86 % to the total input of 640 kg N ha

-1, and output of 404 kg N ha

-1 was by weaned piglets, resulting in a surface surplus of 235 kg N ha

-1. Nitrate leaching was the largest mass flow contributing to the soil N balance, although direct N emissions from animal manure compared to crop residues were also substantial (

Table 2). In year 1, the soil N balance was similar between all treatments, whereas in year 2, it was favourable (closer to zero) for the paddocks with unmanaged (T) compared to pruned trees (P), whereas differences by resource position had little effect.

4. Discussion

4.1. Remote Sensing Support of High Resolution Spatio-Temporal Modelling of Nitrate Leaching

An added value of optical remote sensing is to depict explicitly the spatial variability to support modelling of soil water transport related phenomena such as nitrate leaching. In silvopastoral systems with N hot spots, such knowledge provides opportunity to design and implement tools for distribution of the hotspot into larger variability to reduce the hotspot magnitude. Weather is well-known dataset to obtain from remote sensing via temperature, radiation and anemometer sensors. For studies at high spatial scales in the order of meters, such as this study, it is fair to assume homogeneous weather distribution over the field occupied with paddocks 0.4 ha, i.e., about 2 ha in total housing 16 paddocks (

Figure 1). For larger areas with tree hedges or undulated rolling terrains, weather inputs depicting variability to feed models like Daisy are invaluable, otherwise, large errors would propagate and sum up in the simulated water balance and nitrate leaching [

42].

Noteworthy is the micrometeorology between pruned and tall poplar trees, which might differ in relation to more surface exposed to radiation under pruned conditions [

43], which in turn would increase evapotranspiration and lower percolation. However, studies show that this effect is temporary and pruned trees eventually dissipate less energy due to the smaller total leaf area [

44], which in the context of this study fits to the observation of increased nitrate leaching.

Table 2.

Annual soil nitrogen balances (kg N ha-1 year-1) for four paddocks (total area ca. 0.4 ha) with about a third covered by poplar trees. Year 1 (April 2022-March 2023) with barley undersown grass-clover, year 2 (April 2023-March 2024) pasture for 12 sows supplied in three subsequent batches. Trees were either pruned (P) with woodchips mulch or unmanaged (tall, T) and resources (feed, hut) placed either on same (S) or opposite side (O) with trees in between. Nitrate leaching was obtained from generalized linear model; equal letters indicate non-significant difference within the year (confidence level p = 0.05).

Table 2.

Annual soil nitrogen balances (kg N ha-1 year-1) for four paddocks (total area ca. 0.4 ha) with about a third covered by poplar trees. Year 1 (April 2022-March 2023) with barley undersown grass-clover, year 2 (April 2023-March 2024) pasture for 12 sows supplied in three subsequent batches. Trees were either pruned (P) with woodchips mulch or unmanaged (tall, T) and resources (feed, hut) placed either on same (S) or opposite side (O) with trees in between. Nitrate leaching was obtained from generalized linear model; equal letters indicate non-significant difference within the year (confidence level p = 0.05).

| Mass flow |

Year 1-barley |

Year 2-sows |

Average year |

P

O |

P

S |

T

O |

T

S |

P

O |

P

S |

T

O |

T

S |

P

O |

P

S |

T

O |

T

S |

| Surface N balance (Table 1) |

- 45 |

375 |

160 |

| |

Direct emission of ammonia (NH3) volatilization |

2 |

53 |

27 |

| Indirect emission by denitrification |

10 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

23 |

23 |

15 |

15 |

16 |

16 |

9 |

9 |

| - manure |

- |

13 |

7 |

| - grass-clover residues |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| - woodchips |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

8 |

8 |

- |

- |

| - poplar leaves |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| - nitrate leaching |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Actual nitrate leaching |

122ᵃᵇ |

122ᵃᵇ |

152ᵃ |

113ᵇ |

231ᵃ |

214ᵃᵇ |

170ᵇ |

163ᵇ |

168ᵃ |

162ᵃᵇ |

161ᵃᵇ |

136ᵇ |

| Total mass outflows |

134 |

134 |

156 |

117 |

314 |

297 |

245 |

238 |

215 |

209 |

201 |

176 |

| Soil N balance |

- 179 |

- 179 |

- 201 |

- 162 |

51 |

68 |

120 |

127 |

- 120 |

- 114 |

- 106 |

- 81 |

| % total losses from products†

|

150 |

150 |

187 |

139 |

60 |

77 |

129 |

136 |

78 |

75 |

75 |

63 |

The spatial variability of the soil properties such as clay content is another potential role of remote, i.e., proximal sensing to aid nitrate leaching spatio-temporal depiction [

3]. In time, these properties do not vary significantly. However, they are a major determinant of percolation and nitrate leaching in agricultural fields, especially clay content and bulk density [

3,

22,

42]. The soil physical properties used in this study turned to be homogeneous across the paddocks, based on the best available data at 10 m spatial resolution. Otherwise, soil physical properties must be included in geostatistical modelling of nitrate leaching from heterogeneous soils and increasing data from proximal sensing make these data available [

45,

46].

Aboveground traits are the most common in remotely sensing aided process-based modelling. Values of LAI are among the input parameters to models describing crop growth and thus water balance. Such LAI estimation techniques perform well for early growth stages but tend to produce high error during the reproductive stage due to canopy closure. Canopy cover is thus a convenient way as it is fraction of leaf covering a unit of land area. In this study LAI was conveniently estimated from CC using the Beer-Lambert Law (

Figure 4), with a

k value of 0.5 common across many plants irrespective of canopy architecture. Although

k can vary depending on growth stage, it is not notably different than k-value of 0.56-0.59 reported for plants in shrubland and broadleaf forests category [

28]. Hence, the approach shows a simple, reliable and efficient method adding value of UAV-based remote sensing for modelling belowground processes. In Daisy, part of precipitation (and overhead irrigation, e.g., sprinkler irrigation, if given) reaching the top of the crop is intercepted by the crop canopy, which acts as an interception storage. The direct water throughfall is assumed to be a function of LAI and the water intercepted by the canopy may be evaporated, stored or flow to the ground as canopy spill off. Therefore, LAI plays a notable role in correct simulation of evapotranspiration and percolation used to estimate nitrate leaching (

Figure 4,

Figure A1). With increasing computational power and machine-learning based retrieval of parameters [

12,

47,

48], LAI data fed to process based model offers excellent opportunity for high precision mapping of soil nitrate leaching.

4.2. Nitrate Leaching Remains Problem for Silvopastoral Agroecosystems Under Humid Climates

As in previous agro-environmental studies in temperate climates, considerable soil nitrate leaching was found in this study at annual and seasonal scales (

Figure 8,

Figure A2). Soil nitrate-N concentrations in the soil water were frequently above 20 mg l

−1. Nitrate concentrations as high as 200 mg l

−1 have also been reported by Manevski et al. [

24] at a hotspot close to the hut. In the present study, a concentration this high occurred only once when one out of the three pooled suction cups did not collect water due to freezing. In the tree zone of PO treatment, high concentrations above 140 mg l

−1 were also sampled at several occasions (

Figure 6) and similar response have been reported earlier [

24]. Leaching was similar to other farrowing paddocks with poplar trees (ca. 170 kg N ha

−1, Manevski et al. [

49]) and farrowing paddocks without trees (126–276 kg N ha

−1 in Eriksen et al. [

6]).

Earlier studies hypothesized that poplar trees reduce nitrate leaching, where leaching was indeed lower in the tree zone compared to grass [

24]. However, it has also been reported that fertilization rates beyond 50 kg N ha

−1 exceeded the N retention of younger poplar trees (7 years old) in Florida [

50]. Additionally, an effect of wood chips immobilizing mineral N was expected. Instead, nitrate leaching across paddocks and within the tree zone was the lowest in treatments with tall trees, whereas pruned trees with wood chips beneath showed peaks in soil nitrate, and hence, nitrate leaching (

Figure 5,

Figure A3). Soil mineral N showed high values (March 2023, before pigs; October 2023, after 2nd batch); March 2024, after 3rd batch; data not shown), hence, it is likely nitrate leaching to have reduced soil mineral N before soil sampling, or the leaching was caused by continuous mineralisation and less by excretion by pigs. Altogether, it indicated that wood chips could not immobilize mineral N in the current study, but added organic N being mineralised. Additionally, pigs have been shown to root the soil with wood chips already at a young age. This aerates the soil and thus provides necessary oxygen for nitrification. Soil moisture seemed to be higher in soil with wood chips [

51], which would be another factor promoting the mineralisation of organic N [

52]. High leaching under pruned trees might also be caused by less developed root systems due to intensified investment in above-ground biomass, although this would also increase N demand. Pruned trees were infected with rust at 90 % of their leaves in September 2023, which must have slowed their development. It is important to emphasise that soil water was sampled at a depth of 1 m, but roots of some poplar species can be as deep as 2.5 m, especially on sandy soils [

53] and might uptake nitrate before it is leached to deeper layers. Thus, no clear conclusion on the leaching leaving the system can be drawn. Noteworthy is the legacy effects of outdoor pig activity even on sandy soils. The experimental paddock area has a long history with outdoor pigs in varying paddock designs, but always with the feed located in grass zone A. This might be a contributing reason for the high leaching hotspots seen in year 1 (grass zone A,

Figure 7).

4.3. Profiling Nitrogen with Empirical Data, Remote Sensing and Process-Based Model

Previous studies involved soil N data and remote sensing data to map soil N balance using machine learning, e.g., random forest [

54,

55]. Studies seldomly employ process-based models to quantify soil N balance, especially in silvopasture context. The presence of livestock could promote nitrate leaching and ammonia volatilization (Table 3) as grazing provides urine returns [

56]. López-Díaz, Benítez [

57] showed similar profiles of soil nitrate for grazed (low stocking rate of 3 sheep ha

−1) and mowed trees in silvopastoral systems with walnut and pasture in Spain. Thus, efficient control of the risk of nitrate leaching could be tested in other studies involving sheep instead of pigs and tree species other than poplar or willow, but evergreen.

Nitrate leaching was the dominant factor in the soil N balance in terms of magnitude, as also shown in other studies [

20,

24,

25,

58] and this remains a problem for all agricultural systems receiving N from feed or fertilizer in wet climates with surplus percolation. Annual nitrate leaching was even high in the year without pig occupation. This might be linked to the sows occupying the paddocks the year before the first observation year (2021/2022). Evaluation of agronomic and engineering methods is needed to be studied during animal husbandry over several years.

Spatial variability in N inputs from fertilizer or feed, and outputs from harvest in agricultural systems could be determined using sensor and satellite supported methods [

59,

60]. The annual surface N balances were substantial in the year with animal husbandry (year 2; > 200 kg N ha

−1;

Table 1). Such situation has also been reported by other studies under comparable pedo-climatic and agronomic conditions [

24]. Of the different treatments investigated, tree management had the strongest impact with unmanaged trees showing soil N balances close to 0, as opposed to pruned trees showing highly negative soil N balances (

Table 2). Therefore, the findings suggest that avoiding poplar pruning before inclusion of pigs in silvopastoral systems under temperate wet climate could be a beneficial management strategy. However, given the complex nitrogen dynamics in outdoor pig systems and site-specific factors, further studies are needed to confirm these effects.

5. Conclusions

This study showed how affordable and simple remote sensing with UAV providing true-colour data for LAI estimation can be integrated into detailed process-based modelling to support the depiction of explicit spatio-temporal patterns of nitrate leaching from the subsoil. The study was conducted in silvopastoral settings, which are among the most complex and hence the principles should be applicable and tested across other agroecosystems. From an agronomic perspective, the study also revealed that tree management influences spatial and temporal patterns of nitrate leaching in outdoor pig systems. Unmanaged poplar trees showed lower leaching compared to trees harvested and mulched with wood chips, especially during the leaching season in autumn and winter. Placing resources on opposite sides should redistribute soil mineral N but do not necessarily reduce nitrate leaching, when total surface balance is excessive. Hence, silvopastoral designs should carefully consider optimising the uptake potential of tree vegetation and the use of wood chip mulch in addition to pig behaviour when aiming to mitigate nutrient losses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.K.; methodology, K.M., M.U. and M.M.; software, M.U. and K.M.; validation, U.J. and A.G.K.; formal analysis, M.U.; investigation, K.M., M.U., M.M., U.J., A.G.K.; resources and data curation, A.G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and M.U.; writing—review and editing, M.U., U.J., A.G.K.; visualization, M.U., M.M. and K.M.; project administration, KM and A.G.K.; supervision, funding acquisition, A.G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Green Development and Demonstration Program (GUDP) in Denmark and the Organic Research, Development, and Demonstration Program (Organic RDD6), coordinated by International Centre for Research in Organic Food Systems (grant number 34009-20-1701) through the project ‘Outdoor sows in novel concepts to benefit the environment’ (OUTFIT).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study and the raw data supporting the conclusions are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Maarit Mäenpää, Søren U. Larsen, Martin Jensen, Kristine V. Riis and Line D. Jensen at Aarhus University for data collection and interpretations, and the organic pig producer for hosting the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are often used in this manuscript:

| LAI |

Leaf Area Index |

| O |

Resources (feed and hut) on opposite side, see Figure 1

|

| N |

Nitrogen |

| P |

Poplar trees pruned (cut to 2 m height from soil surface) |

| S |

Resources (feed and hut) on the same side, see Figure 1

|

| T |

Poplar trees tall, not pruned |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle + RGB and HSV |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Mass flows, nitrogen (N) contents and emission factors used for estimation of the N mass balance from the organic pig farm in Denmark.

Table A1.

Mass flows, nitrogen (N) contents and emission factors used for estimation of the N mass balance from the organic pig farm in Denmark.

| Input |

Unit year−1

|

Amount |

Reference |

| Feed, sow |

kg sow−1

|

735 |

Farm data |

| Feed, piglets |

kg sow−1

|

276 |

Farm data |

| Straw for bedding |

kg sow−1

|

167 |

Farm data |

| Atmospheric deposition |

kg N ha−1

|

11 |

[61]; Modelled average for land in Denmark |

| N fixation |

kg N ha−1

|

30 |

[58]; Grazed grass-clover |

| Grass seeds |

kg N ha−1

|

1 |

[62]; Grass-clover pasture for pigs |

| Spring barley seeds |

kg ha−1

|

210 |

Farm data |

| Output |

|

|

|

| Weaned piglets |

sow−1

|

13.2 |

Farm data |

| Dead piglets |

sow−1

|

1.3 |

Farm data |

| Disappeared piglets |

sow−1

|

3.1 |

Farm data |

| Sow weight loss |

kg sow−1

|

40 |

[7] |

| Barley grain yield |

kg ha−1

|

4000 |

Farm data |

| Barley straw |

kg ha−1

|

2800 |

Farm data |

| Dry matter content |

|

|

|

| Feed, sows |

% kg |

86 |

Farm data |

| Feed, piglets |

% kg |

86 |

Farm data |

| Barley grains |

% kg |

87.1 |

[63] |

| Barley straw |

% kg |

90.9 |

[64] |

| Poplar wood chips |

% kg |

44 |

[65] |

| Poplar leaves |

% kg |

91 |

[66] |

| Nitrogen content |

|

|

|

| Protein |

% kg CP kg N−1

|

16 |

[67] |

| Feed, sows |

% kg CP kg DM−1

|

15.8 |

Farm data |

| Feed, piglets |

% kg CP kg DM−1

|

18.4 |

Farm data |

| Growth, sow |

% kg |

2.2 |

[67] |

| Growth, piglets |

% kg |

2.8 |

[67] |

| Barley grains |

% kg CP kg DM−1

|

11.8 |

[63] |

| Barley straw |

% kg CP kg DM−1

|

3.8 |

[64] |

| Poplar bark |

% kg N kg DM−1

|

2.03 |

[68]; Mean of P.nigra and P.tremula

|

| Poplar wood |

% kg N kg DM−1

|

1.16 |

[68]; Mean of P.nigra and P.tremula

|

| Poplar leaves |

% kg N kg DM−1

|

2.4 |

[66] |

| Crop residues |

|

|

|

| Grass-clover littering |

kg N ha−1

|

14 |

[49] |

| Crop residues, grass clover |

kg N ha−1

|

87 |

[69]; unfertilized mix of white clover and ryegrass, stubbles + root |

| Crop residues, spring barley |

Mg ha−1

|

6.71 |

Spring feed barley residue biomass in USA, Idaho |

| Poplar leaf littering |

kg ha−1

|

3280 |

[66] |

| Wood chip amount |

kg ha−1

|

105600 |

Farm data |

| Wood chip bark share |

% kg |

16.2 |

[68]; Mean of P.nigra and P.tremula

|

| Wood chip wood share |

% kg |

83.8 |

[68] |

| Emission factors |

|

|

|

| Ammonia volatilization, from manure on pasture |

% kg N in deposited N |

5 |

[70] |

| Ammonia volatilization, grass |

% kg N in feed N |

13 |

[6]; Assuming even distribution of urine and faeces |

| Ammonia volatilization, tree |

% kg N in excreted N |

7 |

[71]; Growing pigs; assuming even distribution of urine and faeces |

| Ammonia volatilization, crop |

kg N ha−1

|

2 |

Albrektsen (2021); assumed |

| Ammonia volatilization, grass |

kg N ha−1

|

3 |

[70] |

| Denitrification, N2O, from manure on pasture |

% kg N in excreted N |

1.5 |

IPCC (2006) |

| Denitrification, N2O, from crop residues |

% kg N in crop residues |

1 |

IPCC (2006) |

| Denitrification, from nitrate leaching |

% kg N leached |

0.5 |

IPCC (2006); Tier-2 emissions during leaching to groundwater + transport to water courses (transport to sea not included) |

| NOx |

% kg N in excreted N |

4 |

EMEP (2019) |

| Excreted N |

= feed − pig + grass-clover uptake by sow |

estimated |

[49] |

| Uptake of grass-clover |

kg N ha−1

|

23 |

[49]; 500 kg ha−1 grass clover dry matter, with 45% carbon (C), and C/N ratio of 10, which equates to 23 kg N ha−1

|

| Poplar leaf littering |

kg N ha−1

|

71.6 |

Estimated |

Table A2.

Annual precipitation, as measured and corrected, mean annual temperature and annual global radiation in the 10-years average and in the two years of interest from April to March each.

Table A2.

Annual precipitation, as measured and corrected, mean annual temperature and annual global radiation in the 10-years average and in the two years of interest from April to March each.

| Year |

Precipitation (mm) |

Precipitation, corrected to soil surface (Allerup) (mm) |

Temperature (°C) |

Global radiation (W m-2) |

| Average 2014-2023 |

1 302 |

1 587 |

9.0 |

43 393 |

| Year 1 (2022/23) |

1 086 |

1 330 |

9.1 |

44 412 |

| Year 2 (2023/24) |

1 176 |

1 431 |

9.0 |

43 609 |

Table A3.

Random effects of rows in the paddocks on annual nitrate leaching for both years.

Table A3.

Random effects of rows in the paddocks on annual nitrate leaching for both years.

| Zone |

Row |

Response |

Zone |

Row |

Response |

Zone |

Row |

Response |

| A |

1 |

172.7 |

B |

7 |

33.5 |

C |

12 |

242.1 |

| 2 |

216.5 |

|

8 |

224.2 |

|

13 |

268.0 |

| 3 |

435.6 |

|

9 |

274.5 |

|

14 |

261.9 |

| 4 |

202.6 |

|

10 |

440.4 |

|

15 |

160.7 |

| 5 |

145.0 |

|

11 |

235.0 |

|

16 |

161.6 |

| 6 |

82.8 |

|

|

|

|

17 |

89.4 |

Figure A1.

Photos of tree zone in treatment with pruned trees in winter 2022 (left), spring 2023 (centre) and aerial view of the study field with the paddocks having either pruned or not pruned (tall) trees (right).

Figure A1.

Photos of tree zone in treatment with pruned trees in winter 2022 (left), spring 2023 (centre) and aerial view of the study field with the paddocks having either pruned or not pruned (tall) trees (right).

Figure A2.

Soil particle size, humus (% volume), total carbon (C) and total nitrogen (N) (%, mg kg

-1) in topsoil (0-20 cm) in three vegetation zones (grass-clover, A, poplar trees, B, and grass-clover, C;

Figure 1) pooled for four treatments (poplar trees pruned (P) or unpruned (tall, T) with resources located on opposite (O) or same (S) sides). Soil sampled on 27 March 2023. Data from Ullfors [

51].

Figure A2.

Soil particle size, humus (% volume), total carbon (C) and total nitrogen (N) (%, mg kg

-1) in topsoil (0-20 cm) in three vegetation zones (grass-clover, A, poplar trees, B, and grass-clover, C;

Figure 1) pooled for four treatments (poplar trees pruned (P) or unpruned (tall, T) with resources located on opposite (O) or same (S) sides). Soil sampled on 27 March 2023. Data from Ullfors [

51].

Figure A3.

Development of vegetation cover derived from visual assessment.6.

Figure A3.

Development of vegetation cover derived from visual assessment.6.

Figure A4.

Weekly (accumulated over a week)) nitrate leaching at 1 m soil depth for different vegetation zones in paddocks with trees either tall (not pruned, T) or pruned (P) and hut (boxes with indication of batch no.) placed either on the same (S) or on opposite sides (O) of trees. Thick marks on y-axis show the distribution of the raw data used in this analysis.

Figure A4.

Weekly (accumulated over a week)) nitrate leaching at 1 m soil depth for different vegetation zones in paddocks with trees either tall (not pruned, T) or pruned (P) and hut (boxes with indication of batch no.) placed either on the same (S) or on opposite sides (O) of trees. Thick marks on y-axis show the distribution of the raw data used in this analysis.

References

- Poudel, S., G. Pent, and J. Fike, Silvopastures: Benefits, Past Efforts, Challenges, and Future Prospects in the United States. Agronomy, 2024. 14(7): p. 1369. [CrossRef]

- Kuchler, P.C., et al., Monitoring Complex Integrated Crop–Livestock Systems at Regional Scale in Brazil: A Big Earth Observation Data Approach. Remote Sensing, 2022. 14(7): p. 1648. [CrossRef]

- Rivest, D. and M.-O. Martin-Guay, Nitrogen leaching and soil nutrient supply vary spatially within a temperate tree-based intercropping system. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 2024. 128(2): p. 217–231. [CrossRef]

- Shurson, G.C. and B.J. Kerr, Challenges and opportunities for improving nitrogen utilization efficiency for more sustainable pork production. Frontiers in Animal Science, 2023. Volume 4 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- Salomon, E., et al., Outdoor pig fattening at two Swedish organic farms—Spatial and temporal load of nutrients and potential environmental impact. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2007. 121(4): p. 407–418. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J., S.O. Petersen, and S.G. Sommer, The fate of nitrogen in outdoor pig production. Agronomie, 2002. 22(7-8): p. 863–867. [CrossRef]

- Kongsted, A.G., et al., Miljøpåvirkning fra udendørs hold af grise – Del 2. DCA - Nationalt Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug. https://pure.au.dk/portal/da/publications/miljøpåvirkning-fra-udendørs-hold-af-grise-del-2. 2020.

- Werner, J.P.S., et al., Mapping Integrated Crop–Livestock Systems Using Fused Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope Time Series and Deep Learning. Remote Sensing, 2024. 16(8): p. 1421. [CrossRef]

- Feng, W., et al., Simulation of spatial and temporal variation of nitrate leaching in the vadose zone of alluvial regions on a large regional scale. Science of The Total Environment, 2024. 916: p. 170114. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., et al., Integrating UAV and satellite LAI data into a modified DSSAT-rapeseed model to improve yield predictions. Field Crops Research, 2025. 327: p. 109883. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, G.S.A., et al., Carbon estimation in an integrated crop-livestock system with imaging sensors aboard unmanned aerial platforms. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 2022. 28: p. 100867.

- Chen, Q., et al., Unsupervised Plot-Scale LAI Phenotyping via UAV-Based Imaging, Modelling, and Machine Learning. Plant Phenomics, 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D., et al., Improvement of sugarcane yield estimation by assimilating UAV-derived plant height observations. European Journal of Agronomy, 2020. 121: p. 126159. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., et al., Bayesian calibration of AquaCrop model for winter wheat by assimilating UAV multi-spectral images. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2019. 167: p. 105052. [CrossRef]

- Ge, H., et al., Estimating rice yield by assimilating UAV-derived plant nitrogen concentration into the DSSAT model: Evaluation at different assimilation time windows. Field Crops Research, 2022. 288: p. 108705. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., et al., Improving maize yield estimation by assimilating UAV-based LAI into WOFOST model. Field Crops Research, 2024. 315: p. 109477. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X., et al., Assimilation of LAI Derived from UAV Multispectral Data into the SAFY Model to Estimate Maize Yield. Remote Sensing, 2021. 13(6): p. 1094. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z., et al., Research on the rice fertiliser decision-making method based on UAV remote sensing data assimilation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2024. 216: p. 108508. [CrossRef]

- Veihe, A., et al., The power of models in planning: the case of daisygis and nitrate leaching. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 2006. 88(2): p. 215–229. [CrossRef]

- Manevski, K., et al., Nitrate leaching and nitrogen balances for integrated willow-poultry organic systems in Denmark. Agricultural Systems, 2024. 221. [CrossRef]

- Spijker, J., D. Fraters, and A. Vrijhoef, A machine learning based modelling framework to predict nitrate leaching from agricultural soils across the Netherlands. Environmental Research Communications, 2021. 3(4). [CrossRef]

- Schuster, J., et al., Spatial variability of soil properties, nitrogen balance and nitrate leaching using digital methods on heterogeneous arable fields in southern Germany. Precision Agriculture, 2023. 24(2): p. 647–676. [CrossRef]

- Gikas, G.D., V.A. Tsihrintzis, and D. Sykas, Effect of trees on the reduction of nutrient concentrations in the soils of cultivated areas. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 2016. 188(6): p. 327. [CrossRef]

- Manevski, K., et al., Effect of poplar trees on nitrogen and water balance in outdoor pig production - A case study in Denmark. Sci Total Environ, 2019. 646: p. 1448–1458. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M., et al., Elimination behavior and soil mineral nitrogen load in an organic system with lactating sows – comparing pasture-based systems with and without access to poplar (Populus sp.) trees. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 2018. 43(6): p. 639–661. [CrossRef]

- Ullfors, M., et al., Paddock design influences soil inorganic nitrogen distribution in a pasture-based sow system with poplar trees. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems (submitted), 2025.

- Breda, N.J., Ground-based measurements of leaf area index: a review of methods, instruments and current controversies. J Exp Bot, 2003. 54(392): p. 2403–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., et al., A meta-analysis of the canopy light extinction coefficient in terrestrial ecosystems. Front. Earth Sci., 2014. 8(4): p. 599–609. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S., et al., Daisy: Model Use, Calibration, and Validation. Transactions of the Asabe, 2012. 55(4): p. 1315–1333. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G., et al., FAO Penman-Monteith equation. In Crop evapotranspiration - Guidelines for computing crop water requirements - FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. . 1998.

- Allerup, P., H. Madsen, and F. Vejen, A comprehensive model for correcting point precipitation. Nordic Hydrology, 1997. 28(1): p. 1–20.

- Allen, R.G., et al., Meteorological data. In Crop evapotranspiration - Guidelines for computing crop water requirements - FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1998.

- Møller, A.B., Soil map by Danish classification system at 10 m resolution (JB-kort i 10 m opløsning), D. Aarhus University, SEGES, University of Copenhagen, Editor. 2024.

- Van Donk, S.J., et al., Wood chip mulch thickness effects on soil water, soil temperature, weed growth and landscape plant growth. ournal of Applied Horticulture, 2011. 13(2): p. 91–95.

- Zribi, W., et al., Efficiency of inorganic and organic mulching materials for soil evaporation control. Soil and Tillage Research, 2015. 148: p. 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Boegh, E., et al., Remote sensing based evapotranspiration and runoff modeling of agricultural, forest and urban flux sites in Denmark: From field to macro-scale. Journal of Hydrology, 2009. 377(3-4): p. 300–316. [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, A.S., J.A. Withers, and L.G. Toal, The effect of surface height of swards continuously stocked with cattle on herbage production and clover content over four years. Grass and Forage Science, 1995. 50(1): p. 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Korte, C.J., B.R. Watkin, and W. Harris, Use of residual leaf area index and light interception as criteria for spring-grazing management of a ryegrass-dominant pasture. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 1982. 25(3): p. 309–319. [CrossRef]

- Lord, E.I. and M.A. Shepherd, Developments in the use of porous ceramic cups for measuring nitrate leaching. Journal of Soil Science, 2006. 44(3): p. 435–449. [CrossRef]

- Børgesen, C.D., J. Djurhuus, and A. Kyllingsbaek, Estimating the effect of legislation on nitrogen leaching by upscaling field simulations. Ecological Modelling, 2001. 136(1): p. 31–48. [CrossRef]

- Manevski, K., et al., Nitrogen balances of innovative cropping systems for feedstock production to future biorefineries. Sci Total Environ, 2018. 633: p. 372–390. [CrossRef]

- Manevski, K., et al., Modelling agro-environmental variables under data availability limitations and scenario managements in an alluvial region of the North China Plain. Environmental Modelling & Software, 2019. 111: p. 94–107. [CrossRef]

- Bohn Reckziegel, R., et al., Virtual pruning of 3D trees as a tool for managing shading effects in agroforestry systems. Agroforestry Systems, 2022. 96(1): p. 89–104. [CrossRef]

- Comin, S., et al., Effects of severe pruning on the microclimate amelioration capacity and on the physiology of two urban tree species. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2025. 103: p. 128583. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T., et al., Nitrogen-based proximal sensing and data fusion for management zone delineation. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment, 2025. 8(1): p. e70051.

- Oladipupo, R.A., et al., A novel on-line dual sensing system for soil property measurement and mapping. Smart Agricultural Technology, 2024. 9: p. 100640. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., et al., Non-destructive monitoring of maize LAI by fusing UAV spectral and textural features. Front Plant Sci, 2023. 14: p. 1158837. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., et al., Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing for Field-Based Crop Phenotyping: Current Status and Perspectives. Front Plant Sci, 2017. 8: p. 1111. [CrossRef]

- Manevski, K., et al., Effect of poplar trees on nitrogen and water balance in outdoor pig production – A case study in Denmark. Science of The Total Environment, 2019. 646: p. 1448–1458. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H. and S. Jose, Nitrate leaching in cottonwood and loblolly pine biomass plantations along a nitrogen fertilization gradient. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2005. 105(4): p. 615–623. [CrossRef]

- Ullfors, M., The effect of farrowing paddock design on soil nitrogen availability in a sow system with integrated poplar trees (Populus sp.), in Department of Agroecology. 2024, Aarhus University: Foulum. p. 79.

- Guntiñas, M.E., et al., Effects of moisture and temperature on net soil nitrogen mineralization: A laboratory study. European Journal of Soil Biology, 2012. 48: p. 73–80. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2011.07.015.

- Breuer, L., K. Eckhardt, and H.-G. Frede, Plant parameter values for models in temperate climates. Ecological Modelling, 2003. 169(2): p. 237–293. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al., Mapping Soil Available Nitrogen Using Crop-Specific Growth Information and Remote Sensing. Agriculture, 2025. 15(14): p. 1531. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al., Mapping stocks of soil total nitrogen using remote sensing data: A comparison of random forest models with different predictors. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2019. 160: p. 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Ledgard, S., J. Luo, and R. Monaghan, Managing mineral N leaching in grassland systems. CABI, 2011: p. 83–91.

- López-Díaz, M.L., et al., Managing high quality timber plantations as silvopastoral systems: tree growth, soil water dynamics and nitrate leaching risk. New Forests, 2020. 51(6): p. 985–1002. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M., et al., Increased Foraging in Outdoor Organic Pig Production-Modeling Environmental Consequences. Foods, 2015. 4(4): p. 622–644. [CrossRef]

- Futerman, S.I., et al., The potential of remote sensing of cover crops to benefit sustainable and precision fertilization. Science of The Total Environment, 2023. 891: p. 164630. [CrossRef]

- Preza Fontes, G., et al., Combining Environmental Monitoring and Remote Sensing Technologies to Evaluate Cropping System Nitrogen Dynamics at the Field-Scale. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2019. Volume 3 - 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ellermann, T., et al., Atmosfærisk deposition 2022 (Issue 304). http://dce2.au.dk/pub/SR588.pdf. 2024.

- Jakobsen, M., Integrating foraging and agroforestry into organic pig production-environmental and animal benefits. PhD Dissertation. https://agro.au.dk/fileadmin/DJF/Agro/Projekter/pECOSYSTEM/Endelig_afhandling_tryk_Malene_Jakobsen_20111406__002_XKORT.pdf. 2018.

- Heuzé, V., et al. Barley grain. Feedipedia, a Programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. . 2016; Available from: https://feedipedia.org/node/227.

- Heuzé, V., et al. Barley straw. Feedipedia, a Programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. . 2021; Available from: https://www.feedipedia.org/node/60.

- Pecenka, R., H. Lenz, and T. Hering, Options for Optimizing the Drying Process and Reducing Dry Matter Losses in Whole-Tree Storage of Poplar from Short-Rotation Coppices in Germany. Forests, 2020. 11(4): p. 374. [CrossRef]

- Thevathasan, N.V. and A.M. Gordon, Poplar leaf biomass distribution and nitrogen dynamics in a poplar-barley intercropped system in southern Ontario, Canada. Agroforestry Systems, 1997. 37(1): p. 79–90. [CrossRef]

- Tybirk, P., P.T. S., and H. Damgaard, Gødning fra økologiske svin – normtal. Notat nr. 1830. Seges Svineproduktion. 2018.

- Hadrović, S., et al., Biomass Carbon and Nitrogen Content of Softwood Broadleaves in Southwestern Serbia. HortScience, 2022. 57(6): p. 684–685. [CrossRef]

- Hauggaard-Nielsen, H., P. Ambus, and E.S. Jensen, Temporal and spatial distribution of roots and competition for nitrogen in pea-barley intercrops – a field study employing 32P technique. Plant and Soil, 2001. 236(1): p. 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, N.J., et al., A detailed ammonia emission inventory for Denmark. Atmospheric Environment, 2001. 35(11): p. 1959–1968. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, U., et al., Nitrogen distribution as affected by stocking density in a combined production system of energy crops and free-range pigs. Agroforestry Systems, 2018. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Layout of paddocks with different vegetation zones and containing feed (red circles) and water (red squares), and hut (grey boxes with indicated batch number) positioned either on the same (S) or opposite sides (O) with trees in between. The trees were either not pruned (tall, T) or pruned (P). Each paddock was equipped with 51 suction cells (black dots) pooled by three (encirclements) for soil water sampling. Collection boxes are shown as black rectangles. The four examined paddocks were part of a larger experiment on 16 paddocks (right plot) as reported in Ullfors et al. (2025). Layout not to scale.

Figure 1.

Layout of paddocks with different vegetation zones and containing feed (red circles) and water (red squares), and hut (grey boxes with indicated batch number) positioned either on the same (S) or opposite sides (O) with trees in between. The trees were either not pruned (tall, T) or pruned (P). Each paddock was equipped with 51 suction cells (black dots) pooled by three (encirclements) for soil water sampling. Collection boxes are shown as black rectangles. The four examined paddocks were part of a larger experiment on 16 paddocks (right plot) as reported in Ullfors et al. (2025). Layout not to scale.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the time overlap of different data collection and animal husbandry batches.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the time overlap of different data collection and animal husbandry batches.

Figure 3.

Example of threshold determination using GIMP-GNU Image Manipulation Software using the colour values of green leaf area and other image features such as branches and surrounding soil to estimate leaf area index of the poplars in the experimental paddocks.

Figure 3.

Example of threshold determination using GIMP-GNU Image Manipulation Software using the colour values of green leaf area and other image features such as branches and surrounding soil to estimate leaf area index of the poplars in the experimental paddocks.

Figure 4.

Development of Leaf Area Index (LAI) derived from UAV imagery (tree zone, B) and from visual assessment (grass zones, A and C) in the paddocks. Treatments include resources (feed and hut) positioned either on same (S) or opposite sides (O) with trees in between, and trees either not pruned (tall, T) or pruned (P). Shaded areas show standard error of different subzones used for visual assessment.

Figure 4.

Development of Leaf Area Index (LAI) derived from UAV imagery (tree zone, B) and from visual assessment (grass zones, A and C) in the paddocks. Treatments include resources (feed and hut) positioned either on same (S) or opposite sides (O) with trees in between, and trees either not pruned (tall, T) or pruned (P). Shaded areas show standard error of different subzones used for visual assessment.

Figure 5.

Simulated water balance components in both observation years in grass-clover and poplar vegetation with shaded areas representing standard deviation from different zones (see

Figure 1).

Figure 5.

Simulated water balance components in both observation years in grass-clover and poplar vegetation with shaded areas representing standard deviation from different zones (see

Figure 1).

Figure 6.

Spatio-temporal distribution of soil nitrate measured at 1 m depth in experimental paddocks with sows and piglets and their resources (feed and hut) positioned either on same (S) or opposite side (O) with trees in between, and trees were either tall (not pruned, T) or pruned (P). Bright line rectangles depict soil mineral nitrogen sampling (Ullfors et al., 2025).

Figure 6.

Spatio-temporal distribution of soil nitrate measured at 1 m depth in experimental paddocks with sows and piglets and their resources (feed and hut) positioned either on same (S) or opposite side (O) with trees in between, and trees were either tall (not pruned, T) or pruned (P). Bright line rectangles depict soil mineral nitrogen sampling (Ullfors et al., 2025).

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of annual (accumulated) nitrate leaching from 1 m soil depth across paddocks with trees either tall (not pruned, T) or pruned (P) and hut (boxes with indication of batch no.) positioned either on same (S) or opposite side (O) of feed with trees in between.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of annual (accumulated) nitrate leaching from 1 m soil depth across paddocks with trees either tall (not pruned, T) or pruned (P) and hut (boxes with indication of batch no.) positioned either on same (S) or opposite side (O) of feed with trees in between.

Figure 8.

Effect of vegetation zones, pruning (not pruned, T, or pruned, P) and resource (hut, feed) position (on same, S, or opposite sides (O) with trees in between) on annual nitrate leaching from 1 m soil depth. Boxplot midlines show mean, hinges show first and third quartiles, whiskers extend to the most extreme values but not exceeding 1.5 times inter-quartile range. Points on right side of the boxplots show least-square means with error bars being 95 % confidence intervals. P-values for contrasting zones (line colour showing treatment level) or treatments (black lines) are given on top.

Figure 8.

Effect of vegetation zones, pruning (not pruned, T, or pruned, P) and resource (hut, feed) position (on same, S, or opposite sides (O) with trees in between) on annual nitrate leaching from 1 m soil depth. Boxplot midlines show mean, hinges show first and third quartiles, whiskers extend to the most extreme values but not exceeding 1.5 times inter-quartile range. Points on right side of the boxplots show least-square means with error bars being 95 % confidence intervals. P-values for contrasting zones (line colour showing treatment level) or treatments (black lines) are given on top.

Table 1.

Annual surface nitrogen balances (kg N ha-1 year-1) for four paddocks (total area ca. 0.4 ha) with a third covered by poplar trees. Year 1 (April 2022-March 2023) with barley undersown grass-clover, year 2 (April 2023-March 2024) pasture for 12 sows supplied in three subsequent batches.

Table 1.

Annual surface nitrogen balances (kg N ha-1 year-1) for four paddocks (total area ca. 0.4 ha) with a third covered by poplar trees. Year 1 (April 2022-March 2023) with barley undersown grass-clover, year 2 (April 2023-March 2024) pasture for 12 sows supplied in three subsequent batches.

| Mass flow |

Year 1 – barley |

Year 2 – sows |

Average year |

| |

Feed, sow |

- |

480 |

140 |

| |

Feed, piglets |

- |

210 |

100 |

| |

Sow weight loss |

- |

28 |

14 |

| |

Straw |

- |

29 |

15 |

| |

Atm. deposition |

11 |

11 |

11 |

| |

Clover fixation |

20 |

20 |

20 |

| |

Seeds |

5 |

- |

2 |

| Total input |

36 |

778 |

402 |

| |

Weaned piglets |

- |

348 |

174 |

| |

Dead piglets |

- |

15 |

8 |

| |

Disappeared piglets |

- |

41 |

21 |

| |

Harvest barley grain |

66 |

- |

33 |

| |

Harvest barley straw |

15 |

- |

8 |

| Total output |

81 |

404 |

243 |

| Surface N balance |

- 45 |

374 |

160 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).