1. Introduction

Liver fibrosis is a major pathological outcome of chronic liver injury, defined by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition that gradually replaces functional liver parenchyma and compromises organ function (Henderson et al., 2020). It arises from multiple etiologies including viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and the increasingly prevalent non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) all of which converge on sustained oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling (Lin et al., 2022). These insults perpetuate hepatocellular damage, stimulate immune cell recruitment, and trigger hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation, the central driver of fibrogenesis.

Globally, viral hepatitis B and C remain dominant contributors to liver fibrosis, where chronic immune activation exacerbates hepatocellular injury and perpetuates HSC stimulation (Balakrishnan & Rehm, 2024). In parallel, the surge in obesity and metabolic syndrome has positioned NAFLD as an emerging global driver, particularly in Western and developing nations. NAFLD is mechanistically tied to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and lipotoxicity, which amplify oxidative stress and apoptosis in hepatocytes, reinforcing the fibrotic cascade (El-Kassas et al., 2022).

These pathogenic drivers expose the liver to recurrent cycles of inflammation, apoptosis, and regeneration, which collectively accelerate fibrotic remodeling. This process is orchestrated through dynamic interactions among hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and particularly HSCs—the principal effector cells of fibrosis (Hammerich & Tacke, 2023). Normally quiescent and vitamin A–storing, HSCs adopt a myofibroblast-like phenotype upon injury, characterized by proliferation, migration, and secretion of fibrillar collagens (types I and III) that progressively remodel hepatic architecture (Chao et al., 2024).

The expansion of activated HSC populations accelerates ECM accumulation, leading to septa formation, lobular distortion, and progressive hepatic dysfunction (Wijayasiri et al., 2022). Activated HSCs also secrete pro-fibrotic mediators including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which not only sustain their own activation but also recruit macrophages and other immune cells, thereby reinforcing a pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic microenvironment (Tsuchida & Friedman, 2017).

Given this central role, fibrosis regression fundamentally depends on restraining HSC activation and restoring their apoptotic clearance. Indeed, induction of apoptosis in activated HSCs facilitates ECM degradation and structural remodeling, offering a potential avenue for fibrosis reversal (Hernandez-Gea & Friedman, 2011). Accordingly, the regulation of HSC activation–apoptosis balance has become a cornerstone of antifibrotic research.

Contemporary antifibrotic strategies have largely concentrated on modulating TGF-β signaling or oxidative stress to influence HSC apoptosis, yet no approved therapy effectively halts or reverses fibrosis. This therapeutic gap underscores the need for novel, mechanism-based targets. Recent evidence implicates the RNA-binding protein EWSR1 as a previously unrecognized regulator of fibrotic signaling, although its precise molecular roles remain to be fully defined.

This review aims to consolidate current knowledge on the emerging role of EWSR1 in HSC biology and liver fibrosis. Specifically, we explore how EWSR1 intersects with TGF-β signaling and oxidative stress responses to modulate HSC apoptosis and activation. We critically analyze its potential as a therapeutic target, highlight unresolved mechanistic questions, and outline avenues for future research. By synthesizing this evidence, the review positions EWSR1 as a novel molecular node in fibrogenesis with translational potential for antifibrotic therapy.

2. HSCs in Fibrosis

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are mesenchymal cells residing in the space of Disse, where they normally function as vitamin A reservoirs. In response to chronic liver injury, HSCs transdifferentiate into myofibroblast-like cells, acquiring proliferative and profibrotic properties that establish them as the central drivers of fibrosis (Friedman, 2008).

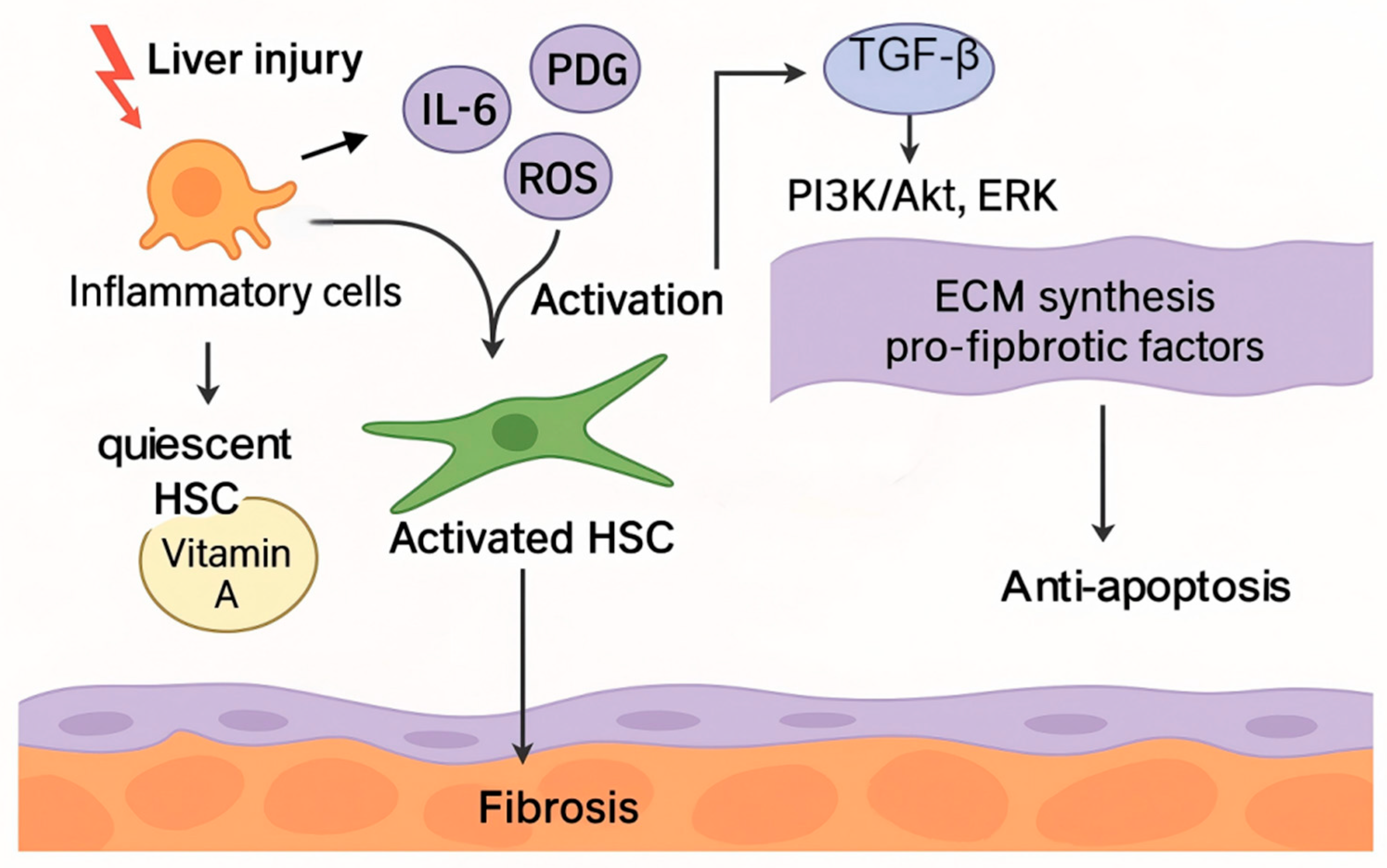

After liver injury, pro-inflammatory cytokines are released by inflammatory cells (such as TGF-β, PDGF, and IL-6), along with ROS, work together to induce HSCs activation. Activated HSCs undergo a series of significant phenotypic changes, including proliferation, migration, and the synthesis and secretion of large amounts of ECM proteins and pro-fibrotic factors (Tsuchida & Friedman, 2017). These characteristics make HSCs an irreversible driving force in the fibrosis process.

The phenotypic transition of activated HSCs typically involves several key molecules and signaling pathways. The TGF-β signaling pathway is one of the primary drivers of HSCs activation, upregulated during liver injury. It activates downstream fibrosis-related genes through SMAD family proteins, promoting ECM synthesis (Yang et al., 2021). Additionally, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) activates the PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling pathways via its receptor, further promoting HSCs proliferation and migration (Chen et al., 2022). The interplay of these signaling pathways not only facilitates HSCs activation but also contributes to the formation of a fibrotic microenvironment, exacerbating liver injury and fibrosis progression.

The activation of HSCs is an irreversible process. Once the activated state is established, HSCs self-sustain and produce large amounts of pro-fibrotic factors, creating a persistent fibrotic microenvironment in the liver. This environment is rich in ECM proteins, cytokines, and chemokines, continuously recruiting immune cells and other fibroblasts, forming a complex cell-cell interaction network that makes liver fibrosis difficult to reverse (Cai et al., 2020).

Additionally, HSCs secrete various tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (such as TIMP-1), which hinder ECM degradation and further exacerbate fibrotic deposition (Parola & Pinzani, 2019). This persistent microenvironment, enriched with ECM proteins, cytokines, and TIMPs, stabilizes fibrosis and makes it difficult to reverse (

Figure 1). This fibrotic microenvironment has a profound impact on the normal structure and function of liver tissue. The excessive accumulation of ECM not only increases liver stiffness but also disrupts the lobular architecture, impairing blood flow and nutrient distribution, ultimately leading to progressive liver function decline (Zhao et al., 2023).

Recent studies have shown that inducing HSCs apoptosis is a key strategy for reversing fibrosis. If activated HSCs are not cleared or reverted, they will continue to secrete fibrotic proteins, exacerbating fibrosis. Therefore, promoting HSCs apoptosis can slow down or partially reverse the fibrotic process. For example, certain anti-fibrotic drugs alleviate fibrosis by activating apoptotic pathways in HSCs or inhibiting their proliferation (Hernandez-Gea & Friedman, 2011).

In the process of fibrosis reversal, the clearance of activated HSCs promotes ECM degradation and the remodeling of fibrotic structures. Some studies have found that inducing HSCs apoptosis by specifically regulating apoptotic signaling pathways, such as Fas/FasL, p53, and Bcl-2/Bax, can help alleviate fibrosis symptoms (Jung & Yim, 2017). However, the regulatory mechanisms of HSCs apoptosis are highly complex and influenced by multiple signaling pathways, making the identification of effective and precise therapeutic targets a key focus of ongoing research.

Due to the central role of HSCs in liver fibrosis, regulating their activation and apoptosis has become a key strategy for anti-fibrotic therapy. Although current anti-fibrotic drugs have yet to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes, targeting HSCs provides new directions for drug development (Roehlen et al., 2020). Recently, attention has shifted toward RNA-binding proteins as novel regulators of HSC fate. In particular, EWSR1 has emerged as a potential molecular link between TGF-β signaling, oxidative stress, and apoptosis resistance in HSCs. Although mechanistic details are still unfolding, preliminary evidence supports its candidacy as a promising antifibrotic target (Bao et al., 2023).

3. Role of the TGF-β Signaling Pathway in Liver Fibrosis

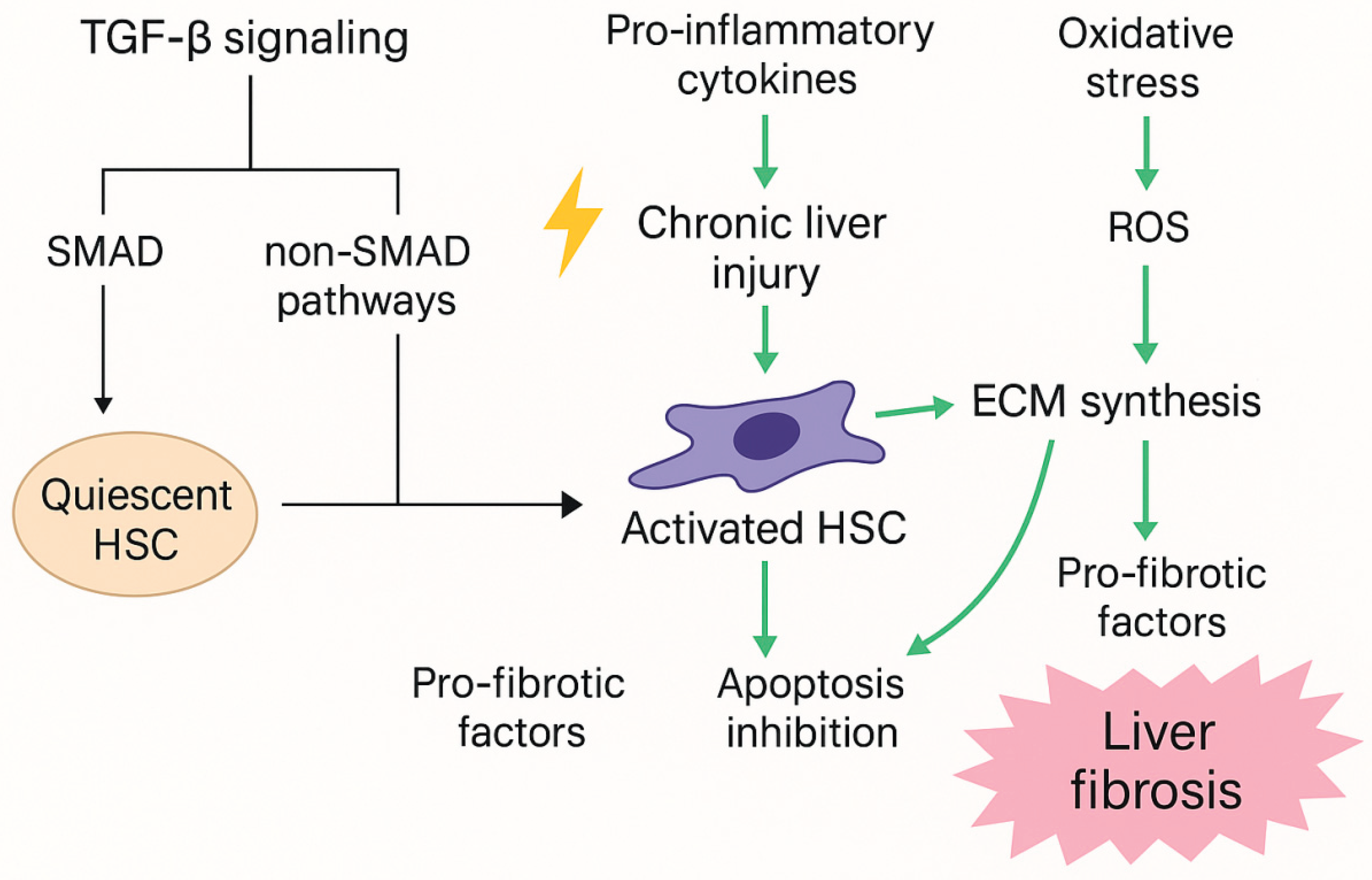

The TGF-β signaling pathway is one of the key pathways regulating liver fibrosis progression. By activating downstream SMAD family proteins and other non-SMAD pathways, TGF-β drives HSCs activation, ECM synthesis, and fibrosis progression. TGF-β not only plays a central role in HSCs activation but also acts as a key regulator in maintaining and advancing the fibrotic microenvironment (Meng et al., 2016).

As a multifunctional cytokine, TGF-β is secreted at increased levels in liver-injured tissues and serves as a major driver of HSC activation. Upon binding to its cell membrane receptors, TGF-β triggers a receptor-type protein kinase phosphorylation cascade, leading to the activation of intracellular SMAD proteins (primarily SMAD2 and SMAD3). These activated SMAD proteins form a complex that translocates into the nucleus to regulate the expression of fibrosis-related genes (Xu et al., 2016). In HSCs, the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway upregulates a series of profibrotic genes, such as collagen, fibronectin, and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (e.g., TIMP-1), thereby promoting ECM accumulation and fibrosis formation (Tzavlaki & Moustakas, 2020).

In addition to the SMAD pathway, TGF-β also exerts its effects through non-SMAD signaling. For instance, TGF-β can activate pathways such as MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and Rho GTPases, which promote HSCs proliferation, migration, and resistance to apoptosis. These non-SMAD pathways exhibit crucial synergistic effects under different cellular and microenvironmental stimuli, endowing TGF-β signaling with high plasticity and adaptability (Zhang, 2009).

During liver fibrosis progression, persistent TGF-β activation drives HSCs proliferation and phenotypic transformation. Activated HSCs exhibit a high level of synthetic activity, producing large amounts of ECM proteins, cytokines, and chemokines. These secreted factors not only sustain HSCs activation but also recruit and activate other cell types, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, creating a highly profibrotic microenvironment (Chun Hao Ong, 2021).

TGF-β signaling in HSCs is not limited to gene expression regulation; it also significantly inhibits apoptosis. Activated HSCs, through TGF-β signaling, upregulate the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 while downregulating the pro-apoptotic factor Bax, thereby reducing their apoptotic tendency (Ong et al., 2021). The anti-apoptotic nature of HSCs further exacerbates fibrosis progression, making it difficult to reverse (Hernandez-Gea & Friedman, 2011).

Within the fibrotic microenvironment, TGF-β not only directly acts on HSCs but also maintains fibrosis progression through interactions with other cell types. For example, TGF-β promotes the polarization of macrophages toward the M2 phenotype, enhancing their profibrotic effects and exacerbating HSCs activation. Additionally, TGF-β induces endothelial and fibroblast transdifferentiation, facilitating angiogenesis and fibrotic tissue remodeling (Dhar et al., 2020). The interplay between TGF-β and these cell types further reinforces the persistence and irreversibility of the fibrotic microenvironment.

During liver injury, TGF-β and oxidative stress often act together to amplify the fibrotic response. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by oxidative stress not only cause direct hepatocyte damage but also increase TGF-β expression and activity, thereby amplifying its signaling pathway effects (Yang et al., 2016). Studies have shown that ROS can enhance TGF-β/SMAD pathway profibrotic effects by oxidatively modifying SMAD3, increasing its binding affinity to TGF-β receptors (Udomsinprasert et al., 2021).

Moreover, TGF-β downregulates antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase, exposing liver tissue to higher oxidative stress levels and further promoting HSCs activation. This interaction between TGF-β and ROS forms a positive feedback loop that accelerates fibrosis progression and renders it more irreversible (Luangmonkong et al., 2018). This reciprocal reinforcement between oxidative stress and TGF-β signaling forms a vicious cycle that accelerates fibrosis (

Figure 2).

Given the central role of TGF-β signaling in liver fibrosis, it has become a primary target for antifibrotic therapy. However, due to TGF-β’s pleiotropic effects and widespread expression in multiple organs, direct inhibition may lead to adverse effects such as immunosuppression and cancer. Consequently, researchers are exploring targeted interventions downstream of TGF-β, such as SMAD3 or non-SMAD pathways, to reduce side effects and improve therapeutic specificity (Zhao et al., 2023).

In recent years, the RNA-binding protein EWSR1 has been found to potentially influence the regulation of the TGF-β signaling pathway. EWSR1 not only modulates TGF-β transcriptional processes but may also participate in oxidative stress regulation, thereby exerting potential antifibrotic effects in fibrosis progression (Yang et al., 2022). This discovery provides a new research direction for antifibrotic therapy, suggesting that modulating EWSR1 to indirectly influence TGF-β signaling may be a promising therapeutic strategy.

4. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Liver Fibrosis

Oxidative stress refers to cellular damage caused when the production of ROS exceeds the cell’s antioxidant defense capacity. In the liver, oxidative stress is not only a critical trigger for liver fibrosis but also interacts with multiple signaling pathways to exacerbate fibrosis progression. ROS contribute to fibrosis through various mechanisms, including inducing inflammatory responses, damaging hepatocytes, and activating HSCs (Allameh et al., 2023).

Under normal conditions, ROS act as signaling molecules regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism. However, in chronic liver injury caused by factors such as alcohol, viral infections, or fat accumulation, ROS production increases significantly, leading to elevated oxidative stress levels. ROS, including superoxide anion (O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), can directly damage hepatocytes by oxidizing lipids, proteins, and DNA, thus triggering inflammation and cell death (Sánchez-Valle et al., 2012).

During liver fibrosis, oxidative stress affects HSCs activation and proliferation through multiple pathways. For instance, ROS activate the MAPK signaling pathway, including ERK, JNK, and p38, promoting HSCs activation and migration (Ramos-Tovar & Muriel, 2020). Oxidative stress also upregulates TGF-β expression and enhances its signaling activity, accelerating the formation of pro-fibrotic HSCs phenotypes (Luangmonkong et al., 2018).

In the early stages of fibrosis, oxidative stress promotes HSCs activation both directly and indirectly. ROS can directly activate HSCs through oxidative protein modifications or indirectly by regulating the expression of various cytokines. For example, oxidative stress activates NF-κB, leading to increased expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TGF-β (Ramos-Tovar & Muriel, 2020). These factors collectively contribute to the transition of HSCs from a quiescent to an activated state.

Additionally, ROS and the TGF-β signaling pathway act synergistically to exacerbate HSCs activation. Studies have shown that ROS oxidatively modify SMAD3, enhancing its binding to TGF-β receptors and amplifying the pro-fibrotic effects of the TGF-β/SMAD pathway. This interaction not only promotes HSC activation but also increases ECM synthesis, accelerating fibrosis progression (Said et al., 2018).

During fibrosis progression, oxidative stress contributes to the formation of a pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic microenvironment, leading to significant structural changes in liver tissue. Accumulated ROS not only activate HSCs but also stimulate Kupffer cells, liver endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, inducing them to secrete additional pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors. This positive feedback loop further stabilizes and sustains the fibrotic microenvironment, making fibrosis difficult to reverse (Zhao et al., 2023).

Oxidative stress also disrupts the balance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs), affecting ECM degradation and accumulation (Duarte et al., 2015). Under oxidative stress conditions, MMP activity decreases while TIMP-1 expression increases, inhibiting ECM degradation and promoting the persistence of the fibrotic microenvironment. This imbalance leads to continuous ECM deposition in the liver, ultimately rendering fibrosis irreversible.

In addition to promoting HSCs activation, oxidative stress also affects their apoptosis (Luangmonkong et al., 2018). The apoptosis of HSCs is essential for fibrosis regression; however, oxidative stress upregulates anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 while downregulating pro-apoptotic factors such as Bax, thereby inhibiting HSCs apoptosis (Elswefy et al., 2016). This inhibition allows activated HSCs to persist, maintaining their pro-fibrotic phenotype.

Given the crucial role of oxidative stress in liver fibrosis, regulating oxidative stress levels has emerged as a potential antifibrotic strategy. Antioxidants can mitigate liver damage by scavenging ROS or enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity. For example, clinical and experimental studies have demonstrated the antifibrotic effects of antioxidants such as vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (Rodriguez et al., 2019).

Recently, the RNA-binding protein EWSR1 has been implicated as a modulator of redox homeostasis in fibrosis. By influencing HSC proliferation, apoptosis, and ROS metabolism, EWSR1 shapes oxidative stress responses. Inhibition of EWSR1 has been reported to reduce ROS levels and attenuate TGF-β signaling, positioning it as a promising antifibrotic target (Bao et al., 2023). The interplay between TGF-β, ROS, and HSC activation is summarized in

Table 1, which highlights their synergistic contribution to fibrosis progression.

.

5. Molecular Function of EWSR1 and Its Fibrosis Regulatory Potential

5.1. Structure and Biological Function of EWSR1

EWSR1, a key member of the RNA-binding protein family, plays a significant role in Ewing’s sarcoma through gene rearrangement. It participates in various cellular processes, including transcriptional regulation, RNA processing, transport, and cellular stress responses, highlighting its multifunctional importance in maintaining cellular homeostasis (Junghee Lee, 2019).

The functional structure of EWSR1 consists of an N-terminal glycine-rich region and a C-terminal poly(guanine) region. The C-terminal region is characterized by an RRM, a zinc finger (ZnF) domain, arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG)-rich domains, and a nuclear localization signal (NLS), which collectively enable EWSR1 to interact with DNA, RNA, and proteins. These structural domains allow EWSR1 to regulate gene expression at multiple levels. Specifically, the RGG-rich domains facilitate DNA binding, enhancing EWSR1’s transcriptional activity and promoting the expression of target genes (Hassoun, 2023). The N-terminal glycine-rich region of EWSR1 provides a robust platform for molecular interactions, enabling it to function as a scaffold for assembling complexes with diverse transcription factors and RNA-binding proteins. This structural feature is essential for coordinating multiple cellular processes through dynamic protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions. The RRM of EWSR1 allows it to specifically bind to target RNA sequences, enabling its participation in key processes such as mRNA splicing, transport, and degradation.

The central molecular role of EWSR1 lies in transcriptional regulation. It can act directly as a transcriptional activator to stimulate gene expression or form multi-protein complexes with transcription factors to modulate promoter activity. For example, EWSR1 interacts with its FET family counterparts, FUS and TAF15, to regulate transcriptional programs (Schöpf et al., 2024; Thomsen et al., 2013). These complexes facilitate the recruitment of RNA polymerase II to promoter regions, thereby enhancing gene transcription. In addition, EWSR1 contributes to chromatin remodelling, modulating chromatin accessibility and enabling transcription factors to more effectively engage with DNA.

EWSR1 acts as a multifunctional protein with essential roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and adapting to physiological demands. Through interactions with transcription factors and other RNA-binding proteins, EWSR1 regulates gene expression and coordinates various cellular processes. Its abnormal expressions or mutations are closely linked not only to tumor development but also to the regulation of fibrosis, immune responses, and cellular stress adaptation, highlighting its broad significance in cellular biology. Studies have shown that in cardiac fibrosis, EWSR1 can bind to the mechanosensitive protein VGLL3 (Horii et al., 2023), inhibiting the expression of miR-29b. MiR-29b is a microRNA that targets collagen mRNA, and its downregulation leads to increased collagen production, a key characteristic of fibrotic tissue. Although this study focuses on cardiac fibrosis, the shared mechanisms of fibrosis across different tissues suggest that EWSR1 may have a similar regulatory role in liver fibrosis. Moreover, EWSR1 has been shown to regulate non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs and miRNAs), which play crucial roles in the pathological process of fibrosis. A study revealed (Pan et al., 2022) that in glioma, EWSR1 can induce the expression of the circular RNA circNEIL3, which promotes tumor cell proliferation and survival by stabilizing the IGF2BP3 protein. Although this study focuses on tumors, it highlights the important role of EWSR1 in the regulation of non-coding RNAs, a function that may similarly influence cell proliferation, survival, and ECM synthesis during fibrosis.

In conclusion, EWSR1, as a multifunctional RNA/DNA-binding protein, precisely regulates gene transcription, RNA binding, and post-transcriptional processing through its various domains. Additionally, EWSR1 may influence the expression of genes associated with ECM production and cell activation by modulating non-coding RNAs, thereby regulating the progression of fibrosis. Further exploration of the functions of different EWSR1 domains and their alterations under pathological conditions will help uncover its specific mechanisms in fibrosis and other diseases, providing a theoretical basis for developing targeted therapeutic strategies against EWSR1. These findings underscore the role of EWSR1 in transcriptional regulation and RNA metabolism, with its key molecular mechanisms summarized in

Table 2.

5.1.1. EWSR1 in Transcriptional Regulation

The role of EWSR1 in transcriptional regulation primarily lies in its interactions with transcription factors and RNA polymerase II (Rajan et al., 2023).

EWSR1 plays a critical role as a chromatin remodeling factor in gene expression regulation, primarily through interactions with transcription factors and RNA polymerase II, modulating the transcriptional activity of specific genes. EWSR1 can directly bind to the activation domains of transcription factors, enhancing their transcriptional activity. For example, in Ewing sarcoma, it forms complexes with the transcriptional co-activators p300 and CBP (Wachtel et al., 2024), collaboratively promoting the expression of target genes. This interaction facilitates the acetylation of histones H3 and H4, leading to a relaxation of chromatin structure and increasing the accessibility of transcription factors and RNA polymerase II to DNA, thereby activating the expression of pro-tumor genes. Additionally, EWSR1 can regulate the open state of chromatin through chromatin remodeling complexes and histone acetyltransferases, thereby activating specific gene transcription during processes such as cell differentiation and stress response. This multi-layered regulatory mechanism underscores the crucial role of EWSR1 in gene expression regulation.

In addition, EWSR1 also acts as a co-activator in transcriptional regulation, interacting with RNA polymerase II and the TATA-binding protein (TBP) to facilitate the assembly of the transcription initiation complex (Hassoun, 2023), ensuring an efficient start to transcription. In this process, EWSR1 collaborates with TBP and the transcription initiation complex (such as TFIID complex) to enhance the stability of the transcription initiation machinery, assisting RNA polymerase II in accurately locating the promoter regions of target genes and stabilizing its binding. This ensures effective initiation of transcription. This mechanism is essential for regulating the expression of fibrosis-related genes, especially under cellular stress conditions, where it helps maintain or modulate the overexpression of these genes. This multi-layered transcriptional regulatory function highlights the critical role of EWSR1 in gene expression and the maintenance of cellular functions.

Meanwhile, the N terminus of EWSR 1 acts as a co-activator to regulate the activity of the promoter after binding with other transcriptional regulatory proteins. EWSR1 participates in the promoter regulation of various genes, particularly those involved in growth factors, cell cycle regulators, and inflammatory mediators. For example, EWSR1 influences cell proliferation and differentiation by regulating the target genes of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Danieau et al., 2019). Under stress conditions, EWSR1 interacts with SMAD3, a key transfuction molecule of TGF-β signaling pathway (Yang et al., 2022), which is likely closely related to the activation of HSCs during fibrosis. By regulating the expression of TGF-β and other pro-fibrotic factors, EWSR1 could serve as a key target for controlling liver fibrosis.

5.1.2. EWSR1 in Non-Coding RNA Regulation

EWSR1’s role in transcriptional regulation also extends to the expression and processing of non-coding RNAs(ncRNAs). Research has shown that EWSR1 can influence the expression of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) (Hassoun, 2023), and it regulates gene expression through interactions with these non-coding RNAs. These lncRNAs play crucial roles in cell development and stress responses, and their dysregulated expression is closely associated with cancer and fibrosis. Moreover, EWSR1’s interaction with miRNA precursors suggests it may participate in the processing of specific miRNAs, potentially affecting their maturation and regulatory functions. Through these mechanisms, EWSR1 exerts a broad influence on gene expression, impacting both physiological and pathological processes.

As an RNA-binding protein, EWSR1 plays a crucial role in the regulation of lncRNA expression, stability, and functionality. lncRNAs are essential regulators of cell differentiation, proliferation, and signal transduction pathways, and EWSR1 can interact with specific lncRNAs, influencing their cellular localization, degradation, and interaction with other proteins. Research has shown (Yamada et al., 2022) that in the intestinal epithelial cells of naked mole-rats, even in the absence of FUS, the expression of EWSR1 and TAF15 can partially compensate for the loss of FUS function. This compensatory effect indicates that EWSR1 and TAF15 share functional similarities with FUS, enabling them to interact with NEAT1_2 and support the formation of Paraspeckles. Additionally, the study speculates that FET family proteins might interact with MALAT1, participating in mRNA splicing and post-transcriptional processing, which are critical cellular processes. These findings highlight the significant role of EWSR1 in the lncRNA regulatory network and suggest its extensive influence on gene expression and cellular function maintenance.

EWSR1 plays a crucial regulatory role in the biogenesis and stability of circRNA. CircRNA, a non-coding RNA with a closed-loop structure, is primarily formed through back-splicing of precursor mRNA. EWSR1 can bind to specific circRNAs, modulating their splicing process and influencing their intracellular localization and distribution. Furthermore, EWSR1 serves as an essential component of circRNA-protein complexes, participating in the regulation of cellular processes such as proliferation, anti-apoptosis, and stress responses. Research has shown (Pan et al., 2022) that EWSR1 regulates the expression of circNEIL3, which stabilizes the IGF2BP3 protein, activates downstream signaling pathways, and promotes cell proliferation and survival. A similar mechanism might exist in the context of fibrosis, where EWSR1 could regulate anti-apoptotic signals in HSCs, maintaining their activated state and contributing to the progression of fibrosis. These findings highlight the multifaceted role of EWSR1 in circRNA regulation, offering new insights into its molecular mechanisms in fibrosis.

EWSR1 participates in the post-transcriptional regulation and stabilization of microRNAs (miRNAs) through direct binding. As a class of small non-coding RNAs, miRNAs primarily regulate gene expression by binding to specific mRNAs, either inhibiting protein translation or accelerating mRNA degradation. EWSR1 can influence the expression and function of specific miRNAs, thereby modulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and fibrosis-related gene expression.

In cardiac fibrosis, studies have shown (Horii et al., 2023) that EWSR1 interacts with VGLL3 to suppress the expression of miR-29b. miR-29b is a critical anti-fibrotic miRNA that targets and degrades collagen mRNA, thereby reducing ECM synthesis. When EWSR1 inhibits miR-29b, collagen production increases, exacerbating fibrosis. This regulatory mechanism may also exist in liver fibrosis, where EWSR1 could modulate miR-29b expression to maintain the pro-fibrotic state of HSCs.

As an essential component of the gene expression regulatory network, ncRNAs play a significant role in various pathological processes, including fibrosis, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders.

In fibrosis, lncRNAs regulate HSCs activation, apoptosis, and abnormal ECM synthesis through interactions with proteins, DNA, or other RNAs. Researchers have discovered (Zhang et al., 2020) that lncRNA MALAT1 can interact with Smad proteins, SETD2, and PPM1A, forming a complex that regulates the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. This promotes the sustained activation of HSCs and enhances the expression of fibrosis-related genes. Such interactions impact the expression of genes associated with liver fibrosis. Additionally, miRNAs also play a crucial regulatory role in fibrosis. Studies have shown (Xie et al., 2021) that miR-29b expression is downregulated in fibrotic tissues, leading to increased synthesis of type I and type III collagen, exacerbating ECM accumulation. Furthermore, research indicates (Wang et al., 2023) that CircPSD3 overexpression significantly reduces α-SMA expression at both mRNA and protein levels, while simultaneously inhibiting HSCs proliferation and activation.

In tumors, ncRNAs also play a significant role. lncRNA HOTAIR is highly expressed in breast cancer and liver cancer (Pei et al., 2023; Qian et al., 2023). It promotes tumor cell proliferation and metastasis by remodeling chromatin structure and suppressing the expression of tumor suppressor genes. In cardiovascular diseases, previous studies have reported (Liao et al., 2016) that lncRNA MIAT is upregulated in myocardial infarction patients, promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis and exacerbating cardiac injury. In neurodegenerative diseases, non-coding RNAs also play a role in disease progression. lncRNA TUG1 is abnormally expressed in neurodeg (Wu et al., 2013).

Although the pathological mechanisms of fibrosis, tumors, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases differ, the regulatory roles of ncRNAs in these conditions exhibit similarities. ncRNAs participate in the onset and progression of diseases by influencing cell proliferation, apoptosis, inflammatory responses, and ECM synthesis. Additionally, ncRNAs can serve as biomarkers for disease diagnosis, staging, and prognosis assessment, or as therapeutic targets to improve disease outcomes through specific regulation of their expression.

5.2. EWSR1 and Its Interaction with TGF-β Signaling

EWSR1, as an RNA-binding protein, is widely distributed across various tissues and plays a critical role in cell proliferation, differentiation, RNA metabolism, and DNA damage repair. TGF-β, a multifunctional cytokine expressed in almost all cells, participates in numerous cellular biological processes through its signaling pathways, including the regulation of cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, ECM production, and fibrosis. The interaction between EWSR1 and TGF-β signaling remains incompletely understood. However, from the perspectives of molecular mechanisms, pathway regulation, and disease relevance, there appears to be a complex and significant relationship between the two.

EWSR1 may influence multiple critical nodes of TGF-β signaling through its RNA-binding ability and protein interactions. The classical TGF-β signaling pathway operates via the Smad-dependent route, in which TGF-β receptors activate R-Smads (Smad2/3), allowing them to form complexes with Co-Smad (Smad4) and translocate to the nucleus to regulate target gene expression. EWSR1 may regulate the expression levels or translational efficiency of Smad mRNA by binding to it. Additionally, EWSR1 might directly interact with Smad proteins, thereby modulating the TGF-β signaling pathway and participating in the regulation of liver fibrosis. Beyond the classical pathway, TGF-β can also activate various signaling pathways through Smad-independent routes, such as MAPK, PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT, and Rho-GTPase. Non-classical TGF-β pathways regulate diverse cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival, broadening the scope of TGF-β signaling in disease progression (Deng et al., 2024). EWSR1 may influence these non-Smad pathways by modulating the expression of PI3K/Akt-related proteins, thereby enhancing cellular migration and promoting anti-apoptotic effects (Mo et al., 2023).

Research has shown that the EWSR1-FLI1 fusion protein disrupts the TGF-β signaling pathway by suppressing the transcription of the TGF-βRII. This suppression reduces cellular sensitivity to TGF-β, thereby promoting tumorigenesis. Mechanistically, EWSR1-FLI1 binds directly to the TGF-βRII promoter, inhibiting its transcriptional activity and impairing downstream TGF-β signaling. This loss of TGF-β signaling is considered a critical step in the progression of Ewing sarcoma (Hahm et al., 1999).

There is a new research that shows that EWSR1 plays a significant role in hepatic fibrosis by influencing fibrogenic gene expression and the activation of HSCs. The study showed that (Bao et al., 2023), Overexpression of EWSR1 in LX-2 cells (a human hepatic stellate cell line) enhanced the mRNA and protein levels of fibrosis markers such as collagen type I alpha 1 chain(COL1A1), α-SMA, and TGF-β1. Conversely, knockdown of EWSR1 reduced the expression of these markers, indicating its pivotal role in hepatic fibrogenesis. The study also demonstrates that EWSR1 was found to regulate connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a downstream target of TGF-β1, which plays a critical role in extracellular matrix production and fibrosis progression. EWSR1’s modulation of TGF-β signaling was associated with the stabilization of specific mRNAs through interactions with microRNA pathways.These findings suggest that EWSR1 not only promotes liver fibrosis by regulating TGF-β-mediated pathways but also provides a potential avenue for therapeutic intervention through the development of inhibitors targeting its function.

In fibrotic diseases, TGF-β is the core driver of fibrosis, and its hyperactivation leads to an abnormal accumulation of collagen and the extracellular matrix. In the progression of fibrosis, the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of SMAD3 are important steps in TGF-β signaling, directly promoting the expression of fibrosis genes (such as COL1A1 and FN 1). EWSR 1 was found to regulate the HSCs activation process in the liver fibrosis model, and promoted fiber deposition by stabilizing the mRNA expression of genes downstream of TGF-β. EWSR1 can interact with SMAD3, suggesting its potential involvement in regulating the TGF-β signaling pathway through its RNA-binding and transcriptional regulatory functions. This interaction implies that EWSR1 may modulate the expression and activity of key transcription factors like SMAD3, thereby influencing TGF-β signaling. Through this regulatory role, EWSR1 could participate in the initiation and progression of liver fibrosis.

5.3. Relationship Between EWSR1 and Oxidative Stress

5.3.1. Role of EWSR1 in Stress-Granule Formation

EWSR1 plays a key role in the formation and regulation of stress granules (SGs). These granules are dynamic ribonucleoprotein complexes rapidly assembled by cells in response to environmental stressors such as oxidative stress, heat shock, viral infections, or toxic damage. They primarily consist of untranslated mRNA, RNA-binding proteins, non-RNA-binding proteins, and translation factors (Wang et al., 2020). By temporarily suppressing the translation of specific mRNAs and storing them, stress granules reduce the cell’s metabolic burden, enabling it to better adapt to adverse conditions. In this process, EWSR1 not only participates in the assembly of stress granules but also plays a crucial regulatory role, ensuring cellular homeostasis and enhancing survival under stress.

Under stress conditions, EWSR1, an RNA-binding protein, relocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it actively participates in SGs formation. Utilizing its RRM, EWSR1 binds directly to untranslated mRNA and interacts with other RNA-binding proteins (Omar, 2024), including TIA-1, G3BP1, and FUS, assembling into large ribonucleoprotein complexes essential for SG stability and function. EWSR1 interacts not only with mRNA but also with dissociated translation factors, such as eIF4G and eIF3 (Wang et al., 2020), disrupting their role in translation initiation. This interaction allows SGs to suppress global protein synthesis, conserving cellular energy, preventing the accumulation of misfolded proteins, and enhancing the cell’s ability to cope with stress. Additionally, SGs temporarily store specific mRNAs, which can be rapidly re-released for translation once the stress subsides, facilitating efficient recovery and cellular repair

During the stress response, the large molecular complexes formed by EWSR1 and RNA-binding proteins are essential for the assembly of stress granules. Acting as a scaffold molecule, EWSR1 facilitates the aggregation of RNA-protein complexes.

The low-complexity domain (LCD) of EWSR1 plays a critical role in its scaffolding function, particularly in the formation of SGs. This domain mediates liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) (Molliex et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2024), a key mechanism for the rapid assembly of membraneless organelles. Through LLPS, EWSR1 facilitates the quick aggregation of untranslated mRNA and associated proteins, forming dynamic stress granule structures. This phase separation property allows SGs to assemble rapidly under stress conditions and disassemble efficiently once the stress is relieved, ensuring a seamless transition between cellular states and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

The scaffolding function of EWSR1 not only facilitates the stable assembly of SGs but also orchestrates the orderly recruitment of proteins and mRNA molecules, finely regulating the composition and function of SGs. This organized assembly and regulation ensure that SGs can rapidly respond to cellular stress and efficiently disassemble once the stress is relieved, maintaining cellular homeostasis. However, when EWSR1 undergoes genetic mutations or abnormal localization, it may lead to aberrant aggregation or delayed disassembly of SGs, impairing the cell’s ability to adapt to environmental stress and potentially contributing to pathological conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases, fibrosis, and cancer.

In neurodegenerative diseases, such as ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), abnormal aggregation of EWSR1 with proteins like FUS leads to the persistent presence of SGs, disrupting normal neuronal function (Masi et al., 2022). EWSR1 dysfunction is also associated with fibrosis and cancer. In the context of liver fibrosis, excessive formation of SGs may enhance HSCs resistance to oxidative stress, allowing them to survive in adverse environments and promote the accumulation of ECM, further exacerbating fibrosis.

5.3.2. Regulation of EWSR1 by Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress plays a critical role in regulating EWSR1, serving as an essential mechanism for cellular adaptation to injury and stress. EWSR1 is involved in key processes such as RNA metabolism, transcriptional regulation, and SGs formation. As oxidative stress drives profibrotic and proinflammatory responses, it can significantly influence EWSR1’s expression, subcellular localization, and functional activity. These regulatory effects are closely linked to the progression of various diseases, including liver fibrosis, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer.

Under oxidative stress, elevated intracellular ROS trigger a series of molecular and cellular alterations, significantly impacting EWSR1’s function. ROS can influence EWSR1 at multiple levels, including its transcriptional expression, nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution, and its role in the assembly and disassembly of SGs. Through post-translational modifications, oxidative stress can fine-tune EWSR1’s involvement in RNA transcription and splicing, contributing to cellular stress responses and repair mechanisms.

Oxidative stress can activate multiple cellular signaling pathways, including NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, and MAPK (Averill-Bates, 2024), which in turn modulate the expression and activity of EWSR1 to enhance cellular stress responses. ROS can upregulate EWSR1 expression or promote its activation, thereby strengthening its transcriptional regulatory capacity and influencing stress-related gene expression. Additionally, oxidative stress-induced epigenetic modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation (Angelopoulou et al., 2023), can alter EWSR1’s transcriptional activity and its interactions with other proteins, further fine-tuning its role in cellular stress defense mechanisms.

Oxidative stress significantly alters the intracellular distribution of EWSR1. Under normal conditions, EWSR1 primarily resides in the nucleus, where it regulates gene transcription and RNA processing (Zhang et al., 2024). However, in response to oxidative stress, EWSR1 relocates to the cytoplasm and actively participates in SGs assembly. This relocation helps cells reduce metabolic demands by temporarily inhibiting the translation of specific mRNAs while safeguarding essential RNA molecules from degradation. Stress granule formation is a vital adaptive mechanism for managing oxidative stress, and EWSR1 plays a central role in this process. By interacting with key RNA-binding proteins such as TIA-1 and G3BP1, EWSR1 facilitates the aggregation of RNA-protein complexes, supporting the efficient assembly and stability of stress granuless (Baradaran-Heravi et al., 2020). These granules dissolve rapidly after stress relief, restoring normal RNA metabolism. However, EWSR1 function may be inhibited or disrupted under conditions of persistent or excessive oxidative stress. For example, stress granules may fail to dissolve properly, resulting in long-term RNA accumulation and translational repression. This phenomenon is particularly prominent in certain diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases (such as ALS) and chronic inflammatory diseases. Abnormal localization of EWSR1 can disrupt cell cycle regulation and proliferation signaling pathways, potentially triggering uncontrolled cell growth and contributing to tumor initiation and progression.

The regulation of EWSR1 by oxidative stress may also affect the development of liver fibrosis through an interaction with TGF-β signaling. In the fibrotic microenvironment, ROS can not only promote the expression of TGF-β signaling, but may also participate in the expression of liver fibrosis-related genes, possibly through the regulation of EWSR1. The sustained activation of HSCs depends on the positive feedback loop of oxidative stress and TGF-β signaling, and the altered function of EWSR1 may exacerbate the maintenance of this feedback loop and further worsen liver fibrosis.

EWSR1 may also directly influence HSC survival by regulating apoptosis-related genes. In the fibrotic environment, HSCs exhibit significant anti-apoptotic capability, primarily regulated by the Bcl-2 protein family, where the balance between anti-apoptotic proteins (such as Bcl-2) and pro-apoptotic proteins (such as Bax) is crucial. If EWSR1 can downregulate Bcl-2 expression while upregulating Bax levels, it may disrupt the anti-apoptotic state of HSCs and trigger mitochondria-mediated apoptotic signaling. Additionally, EWSR1 may affect HSC anti-apoptotic capacity by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT pathway. PI3K/AKT is a key pro-survival signaling pathway in HSCs, promoting the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins and suppressing pro-apoptotic factors to ensure long-term HSC survival. Investigating whether EWSR1 inhibition can weaken this signaling pathway and consequently promote HSC apoptosis is another important research direction.

To verify whether EWSR1 affects HSC apoptosis by regulating ROS production or the antioxidant system, experimental studies using both cellular and animal models are required. By knocking down EWSR1 or treating cells with its inhibitor, changes in ROS levels, as well as the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes in HSCs, can be assessed to elucidate its role in oxidative stress. Meanwhile, evaluating the expression of apoptosis-related genes (such as Bcl-2, Bax, and Caspase-3), combined with apoptosis rate analysis, will further clarify the regulatory role of EWSR1 in HSC apoptosis. Together, these studies establish EWSR1 as a pivotal regulator of fibrotic signaling pathways, as outlined in

Table 3.

5.4. The Potential Role of EWSR 1 in Fibrosis

As an RNA-binding protein, EWSR1 plays a key role in gene expression, RNA splicing, and cellular stress responses. RBPs are a class of proteins that regulate various RNA processes, including generation, splicing, maturation, transport, translation, and degradation, by recognizing specific RNA sequences or structural elements. Serving as essential mediators in post-transcriptional regulation, RBPs bridge the gap between gene transcription and functional protein translation. The specificity and efficiency of RNA binding by RBPs depend on their RNA-binding domains (RBDs). These domains include the RRM, which utilizes α-helices and β-sheets to directly interact with RNA; the zinc-finger domain, stabilized by zinc ions to facilitate RNA binding; the double-stranded RNA-binding domain (dsRBD), specialized for binding double-stranded RNA; and DEAD-box helicase domains, which are involved in RNA metabolism through their helicase activity. Additionally, many RBPs possess multifunctional domains, allowing them to interact simultaneously with RNA and proteins, enabling their integration into larger protein complexes and participation in diverse cellular regulatory networks.

Abnormal expressions of RBPs are closely linked to the progression of various diseases. Research indicates that RBMS3, an RBP, is significantly upregulated in activated HSCs and liver fibrosis. RBMS3 binds to specific sites in the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) of Prx1 mRNA, enhancing its stability and promoting increased protein synthesis. Since Prx1 transactivates the collagen α1 (I) promoter, this interaction further promotes the pro-fibrotic phenotype of HSCs, contributing to the progression of liver fibrosis (Fritz & Stefanovic, 2007). Additionally, other research has demonstrated that the RBP ELAVL1/HuR can regulate ferroptosis in HSCs by activating ferritinophagy, which may induce HSCs apoptosis and alleviate liver fibrosis (Zhang et al., 2018). The study indicates that upon exposure to ferroptosis-inducing compounds, the expression of ELAVL1 protein significantly increases, achieved through the inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Knockdown of ELAVL1 using siRNA leads to resistance to ferroptosis, while ELAVL1 plasmids promote classical ferroptotic events. Additionally, the study observed upregulated ELAVL1 expression, ferritinophagy activation, and ferroptosis induction in primary HSCs collected from liver tissues of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Studies have also found that RBPs are regulated by lncRNAs. Jun-Cheng Wu et al. discovered that Linc-SCRG1 accelerates liver fibrosis by reducing the RNA-binding protein Tristetraprolin (TTP) (Wu et al., 2019). In activated LX2 cells, overexpression of TTP leads to the downregulation of linc-SCRG1 while degrading its downstream target genes, such as MMP-2 and TNF-α. Moreover, the abnormal expression or dysfunction of RBPs is also closely associated with the development of cancer. RBPs influence diverse cancer-associated cellular phenotypes, such as proliferation, apoptosis, senescence, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis, contributing to the initiation and development of tumors, as well as clinical prognosis. Studies have found that members of the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding (CPEB) family are evolutionarily conserved RBPs that are critical regulators of mRNA transport and translation and are implicated in cancer genesis and progression (Wang et al., 2022). In neurodegenerative diseases, RBPs such as TDP-43 and FUS exhibit dysfunction in ALS and FTD, leading to RNA metabolic disorders and toxic RNA-protein aggregates (De Conti et al., 2017). In cardiovascular diseases, RBPs play roles in cardiac fibrosis and myocardial hypertrophy. For example, Quaking (QKI) influences the degree of fibrosis by regulating the activation of cardiac fibroblasts (Chothani et al., 2019). In metabolic diseases, RBPs affect insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism abnormalities by regulating mRNA related to the insulin signaling pathway (Salem et al., 2019).

Research on the relationship between EWSR1 and liver fibrosis is currently limited. TGF-β/SMAD signaling is a core driver of HSCs activation, activated TGF-β initiates the SMAD-dependent pathway by binding to TGF-β RII and promotes the expression of downstream fibrotic genes, including type I and III collagen (COL1A1 and COL3A1) and FN1. In addition, TGF-β further enhanced the pro-fibrotic phenotype of HSCs and increased its proliferation through non-SMAD pathways (such as PI3K/AKT, MAPK, etc.), increasing its proliferation, migration, and anti-apoptotic capacity. EWSR1 might be able to interfere with critical nodes of these pathways, thereby contributing to the progression of liver fibrosis.

In terms of the molecular mechanisms, the RNA binding and transcriptional regulatory functions of EWSR1 make it possible to influence the activity of TGF- β/SMAD signaling through multiple pathways. EWSR1 may directly regulate the expression or stability of key molecules in the TGF- β signaling pathway. Studies have shown that EWSR1 can fuse with SMAD3, with such alterations being associated with fibroblastic tumors. SMAD3 is a critical signal transducer in the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway, which regulates extracellular matrix synthesis in fibroblasts. This suggests a potential connection between EWSR1 and the TGF-β signaling pathway, indicating that EWSR1 may contribute to the progression of liver fibrosis through its involvement in this pathway (Foot et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022). Yunyang Bao et al (Bao et al., 2023). were the first to reveal EWSR1’s role in HSCs activation and liver fibrosis. Their study demonstrated that the compound 6K binds to EWSR1, inhibiting HSCs function and downstream fibrosis-related gene expression, thereby slowing liver fibrosis progression. While EWSR1 has been extensively studied as an anti-tumor target, this research marks its first identification as a potential therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. This discovery offers valuable insights for developing innovative anti-fibrotic treatment strategies.

EWSR1 has been shown to regulate the expression of multiple apoptosis-related genes, including the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 and the pro-apoptotic factor Bax (Heisey et al., 2019). Inhibiting EWSR1 may reduce Bcl-2 expression while increasing Bax activity, thereby disrupting the apoptotic balance in HSCs. Additionally, EWSR1 inhibition could lower the activity of TGF-β-induced anti-apoptotic pathways, such as PI3K/AKT, further sensitizing HSCs to apoptotic signals. This combined effect may ultimately promote HSCs apoptosis and help limit the progression of liver fibrosis.

EWSR1 may influence TGF-β signal transduction by modulating the expression of negative feedback regulators like SMAD7. As an endogenous inhibitor of the TGF-β pathway, SMAD7 competitively binds to TGF-βRI, blocking the phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 and thereby inhibiting downstream signaling. If EWSR1 suppression leads to increased SMAD7 expression, it could effectively reduce TGF-β-induced HSCs activation, offering a potential mechanism for controlling liver fibrosis progression.

Furthermore, EWSR1 inhibition may also impact non-SMAD signaling pathways. Studies suggest that EWSR1 may play an indirect role in regulating PI3K/AKT signaling (Mo et al., 2023). The PI3K/AKT pathway not only interacts with the TGF-β pathway but also directly contributes to the proliferation and anti-apoptotic state of HSCs. Inhibiting EWSR1 might reduce AKT activity, thereby decreasing the anti-apoptotic capacity of HSCs. Combined with the attenuation of TGF-β/SMAD signaling, HSCs may undergo further apoptosis. Additionally, the activity of MAPK pathways (such as ERK, JNK, and p38) could also be affected by EWSR1 inhibition, further reducing the migratory and pro-fibrotic abilities of HSCs.

Although theoretically, the inhibition of EWSR1 might suppress HSCs activation or induce apoptosis by interfering with the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway, this hypothesis requires experimental validation. On the one hand, it is necessary to clarify the specific regulatory effects of EWSR1 on key molecules of the TGF-β signaling pathway in the fibrotic microenvironment. On the other hand, the comprehensive impact of EWSR1 inhibition on HSCs activation and apoptosis needs to be studied using both in vitro and in vivo models. Anyway, the inhibition of EWSR1 may interfere with the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway through multiple mechanisms, thereby suppressing HSCs activation or promoting apoptosis. This potential regulatory role offers a new perspective for exploring EWSR1 as a therapeutic target for anti-fibrotic treatment. However, further in-depth research is needed to elucidate its precise molecular mechanisms and the feasibility of therapeutic applications.

6. Conclusions

EWSR1 may act as a pivotal regulator in HSCs by modulating TGF-β signaling, oxidative stress responses, and apoptosis. Its interactions at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels are associated with regulation of fibrogenic gene expression, stress granule formation, and cell survival, thereby contributing to the initiation and progression of liver fibrosis. Targeting EWSR1 may provide a promising therapeutic approach for mitigating liver fibrogenesis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. J. A. Oxidative stress in liver pathophysiology and disease. 2023, 12(9), 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Pyrgelis, E.-S.; Ahire, C.; Suman, P.; Mishra, A.; Piperi, C. Functional implications of protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) in neurodegenerative diseases. Biology 2023, 12(9), 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antar, S. A.; Ashour, N. A.; Marawan, M. E.; Al-Karmalawy, A. A. Fibrosis: types, effects, markers, mechanisms for disease progression, and its relation with oxidative stress, immunity, and inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(4), 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill-Bates, D. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling. Review. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2024, 1871(2), 119573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, M.; Rehm, J. A public health perspective on mitigating the global burden of chronic liver disease. Hepatology 2024, 79(2), 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Niu, T.; Zhu, J.; Mei, Y.; Shi, Y.; Meng, R.; Wang, Y. Evolution and Discovery of Matrine Derivatives as a New Class of Anti-Hepatic Fibrosis Agents Targeting Ewing Sarcoma Breakpoint Region 1 (EWSR1). Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 66(12), 7969–7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran-Heravi, Y.; Van Broeckhoven, C.; van der Zee, J. Stress granule mediated protein aggregation and underlying gene defects in the FTD-ALS spectrum. Neurobiology of Disease 2020, 134, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, B.; He, Q.; Weng, Q. Intercellular crosstalk of hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis: New insights into therapy. Pharmacol Res 2020, 155, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, G.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, Y. A screening study of high-risk groups for liver fibrosis in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1), 23714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhong, H.; Zhuo, X.; Jia, C.; Wan, Y. Mitofusin-2 Restrains Hepatic Stellate Cells’ Proliferation via PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway and Inhibits Liver Fibrosis in Rats. J Healthc Eng 2022, 2022, 6731335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chothani, S.; Schäfer, S.; Adami, E.; Viswanathan, S.; Widjaja, A. A.; Langley, S. R.; Jian Pua, C. Widespread translational control of fibrosis in the human heart by RNA-binding proteins. Circulation 2019, 140(11), 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun Hao Ong, C. L. T.; Hanis Hazeera Harith; Nazmi Firdaus; Daud Ahmad Israf. TGF-β-induced fibrosis: A review on the underlying mechanism and potential therapeutic strategies, 2021.

- Danieau, G.; Morice, S.; Rédini, F.; Verrecchia, F.; Brounais-Le Royer, B. New insights about the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in primary bone tumors and their microenvironment: a promising target to develop therapeutic strategies? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20(15), 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Conti, L.; Baralle, M.; Buratti, E. Neurodegeneration and RNA-binding proteins. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA; 2017; Volume 8, 2, p. e1394. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2024, 9(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, B.; Meyer, C.; Dooley, S.; Meindl-Beinker, N. TGF-β in hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis—updated 2019. Cells 2019, 8(11), 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, D.; Baglieri, J.; Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D. A. Mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its role in liver cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2020, 245(2), 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.; Baber, J.; Fujii, T.; Coito, A. J. J. M. B. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. 2015, 44, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassas, M.; Cabezas, J.; Coz, P. I.; Zheng, M. H.; Arab, J. P.; Awad, A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Current Global Burden. Semin Liver Dis 2022, 42(3), 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elswefy, S. E. S.; Abdallah, F. R.; Atteia, H. H.; Wahba, A. S.; Hasan, R. A. J. I. j. o. e. p. Inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis cascade implications in bisphenol A-induced liver fibrosis in male rats. 2016, 97(5), 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foot, O.; Hallin, M.; Jones, R. L.; Sumathi, V. P.; Thway, K. EWSR1-SMAD3-Positive fibroblastic tumor. International Journal of Surgical Pathology 2021, 29(2), 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S. L. J. P. r. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. 2008, 88(1), 125–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, D.; Stefanovic, B. RNA-binding protein RBMS3 is expressed in activated hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis and increases expression of transcription factor Prx1. Journal of molecular biology 2007, 371(3), 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Askari, A.; Shoorei, H.; Seify, M.; Koohestanidehaghi, Y.; Hussen, B. M.; Samsami, M. Antioxidant therapy against TGF-β/SMAD pathway involved in organ fibrosis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2024, 28(2), e18052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahm, K.-B.; Cho, K.; Lee, C.; Im, Y.-H.; Chang, J.; Choi, S.-G.; Kim, S.-J. Repression of the gene encoding the TGF-β type II receptor is a major target of the EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. Nature genetics 1999, 23(2), 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Hepatic inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 2023, 20(10), 633–646. [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun, Z. E. O. A Novel Role of EWSR1 Protein in RNA Translation Regulation. Doctoral dissertation, Universite de Liege (Belgium)), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Heisey, D. A.; Lochmann, T. L.; Floros, K. V.; Coon, C. M.; Powell, K. M.; Jacob, S.; Maves, Y. K. The ewing family of tumors relies on BCL-2 and BCL-XL to escape PARP inhibitor toxicity. Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 25(5), 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, N. C.; Rieder, F.; Wynn, T. A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 2020, 587(7835), 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gea, V.; Friedman, S. L. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annual review of pathology: mechanisms of disease 2011, 6(1), 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horii, Y.; Matsuda, S.; Toyota, C.; Morinaga, T.; Nakaya, T.; Tsuchiya, S.; Kasai, K. VGLL3 is a mechanosensitive protein that promotes cardiac fibrosis through liquid–liquid phase separation. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y. K.; Yim, H. J. J. T. K. j. o. i. m. Reversal of liver cirrhosis: current evidence and expectations. 2017, 32(2), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junghee Lee, P. T. N.; Hyun Soo Shim; Seung Jae Hyeon; Hyeonjoo Im; Mi-Hyun Choi; Sooyoung Chung; Neil W. Kowall; Sean Bong Lee; Hoon Ryu. EWSR1, a multifunctional protein, regulates cellular function and aging via genetic and epigenetic pathways. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2019, 1865(7), 1938–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; He, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. LncRNA MIAT: myocardial infarction associated and more. Gene 2016, 578(2), 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M. H.; Li, H. Q.; Zhu, L.; Su, H. Y.; Peng, L. S.; Wang, C. Y.; Wang, Y. Liver Fibrosis in the Natural Course of Chronic Hepatitis B Viral Infection: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2022, 67(6), 2608–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangmonkong, T.; Suriguga, S.; Mutsaers, H. A.; Groothuis, G. M.; Olinga, P.; Boersema, M. Targeting oxidative stress for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology 2018, 175, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Attanzio, A.; Racchi, M.; Wolozin, B.; Borella, S.; Biundo, F.; Buoso, E. Proteostasis deregulation in neurodegeneration and its link with stress granules: focus on the scaffold and ribosomal protein RACK1. Cells 2022, 11(16), 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-m.; Nikolic-Paterson, D. J.; Lan, H. Y. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2016, 12(6), 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Tan, K.; Dong, Y.; Lu, W.; Liu, F.; Mei, Y.; Ye, Y. Therapeutic targeting the oncogenic driver EWSR1:: FLI1 in Ewing sarcoma through inhibition of the FACT complex. Oncogene 2023, 42(1), 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molliex, A.; Temirov, J.; Lee, J.; Coughlin, M.; Kanagaraj, A. P.; Kim, H. J.; Taylor, J. P. Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell 2015, 163(1), 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, K. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Perturbations Caused by Oncogenic Fusion Events. Doctoral dissertation, (Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, C. H.; Tham, C. L.; Harith, H. H.; Firdaus, N.; Israf, D. A. TGF-β-induced fibrosis: A review on the underlying mechanism and potential therapeutic strategies. European journal of pharmacology 2021, 911, 174510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Zhao, R.; Li, B.; Qi, Y.; Qiu, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, M. EWSR1-induced circNEIL3 promotes glioma progression and exosome-mediated macrophage immunosuppressive polarization via stabilizing IGF2BP3. Molecular cancer 2022, 21(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, M.; Pinzani, M. J. M. a. o. m. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues. 2019, 65, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Zhao, L.; Ding, Y.; Su, Z.; Li, D.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, W. JMJD6–BRD4 complex stimulates lncRNA HOTAIR transcription by binding to the promoter region of HOTAIR and induces radioresistance in liver cancer stem cells. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21(1), 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, B. LncRNA HOTAIR as a ceRNA is related to breast cancer risk and prognosis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2023, 200(3), 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S. S.; Ebegboni, V. J.; Pichling, P.; Ludwig, K. R.; Jones, T. L.; Chari, R.; Caplen, N. J. EWSR1’s visual modalities are defined by its association with nucleic acids and RNA polymerase II. bioRxiv: the preprint server for biology 2023, 09(16), 553246. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Tovar, E.; Muriel, P. Molecular mechanisms that link oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver. Antioxidants 2020, 9(12), 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, L.; Bui, S.; Beuschel, R.; Ellis, E.; Liberti, E.; Chhina, M.; Grant, G. J. M. M. Curcumin induced oxidative stress attenuation by N-acetylcysteine co-treatment: a fibroblast and epithelial cell in-vitro study in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 2019, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehlen, N.; Crouchet, E.; Baumert, T. F. Liver Fibrosis: Mechanistic Concepts and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 9(4), 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, M. M.; Azab, S. S.; Saeed, N. M.; El-Demerdash, E. J. A. o. H. Antifibrotic mechanism of pinocembrin: impact on oxidative stress, inflammation and TGF-β/Smad inhibition in rats. 2018, 17(2), 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, E. S.; Vonberg, A. D.; Borra, V. J.; Gill, R. K.; Nakamura, T. RNAs and RNA-binding proteins in immuno-metabolic homeostasis and diseases. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2019, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Valle, V.; C Chavez-Tapia, N.; Uribe, M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Role of oxidative stress and molecular changes in liver fibrosis: a review. Current medicinal chemistry 2012, 19(28), 4850–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöpf, J.; Uhrig, S.; Heilig, C. E.; Lee, K.-S.; Walther, T.; Carazzato, A.; Hartmann, M. Multi-omic and functional analysis for classification and treatment of sarcomas with FUS-TFCP2 or EWSR1-TFCP2 fusions. Nature Communications 2024, 15(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Young, C. D.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.-J. J. B. Transforming growth factor-β signaling in fibrotic diseases and cancer-associated fibroblasts. 2020, 10(12), 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svineng, G.; Ravuri, C.; Rikardsen, O.; Huseby, N.-E.; Winberg, J.-O. J. C. t. r. The role of reactive oxygen species in integrin and matrix metalloproteinase expression and function. 2008, 49(3-4), 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, C.; Grundevik, P.; Elias, P.; Ståhlberg, A.; Åman, P. A conserved N-terminal motif is required for complex formation between FUS, EWSR1, TAF15 and their oncogenic fusion proteins. The FASEB Journal 2013, 27(12), 4965–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, T.; Friedman, S. L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 2017, 14(7), 397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Tzavlaki, K.; Moustakas, A. TGF-β Signaling. Biomolecules 2020, 10(3), 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsinprasert, W.; Sobhonslidsuk, A.; Jittikoon, J.; Honsawek, S.; Chaikledkaew, U. J. E. o. o. t. t. Cellular senescence in liver fibrosis: Implications for age-related chronic liver diseases. 2021, 25(9), 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachtel, M.; Surdez, D.; Grünewald, T. G.; Schäfer, B. W. Functional Classification of Fusion Proteins in Sarcoma. Cancers 2024, 16(7), 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, J.; Fan, S.; Jin, Z.; Huang, C. Targeting stress granules: A novel therapeutic strategy for human diseases. Pharmacological research 2020, 161, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tong, J.; Li, Y.; Qiu, X.; Chen, A.; Chang, C.; Yu, G. Overview of CircRNAs Roles and Mechanisms in Liver Fibrosis. Biomolecules 2023, 13(6), 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, H.-T. RNA-binding proteins and cancer metastasis. Seminars in cancer biology; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayasiri, P.; Astbury, S.; Kaye, P.; Oakley, F.; Alexander, G. J.; Kendall, T. J.; Aravinthan, A. D. Role of Hepatocyte Senescence in the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Liver Fibrosis Progression. Cells 2022, 11(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-C.; Luo, S.-Z.; Liu, T.; Lu, L.-G.; Xu, M.-Y. linc-SCRG1 accelerates liver fibrosis by decreasing RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin. The FASEB Journal 2019, 33(2), 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zuo, X.; Deng, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Ji, A. Roles of long noncoding RNAs in brain development, functional diversification and neurodegenerative diseases. Brain research bulletin 2013, 97, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Lai, Y.; Tang, S. LncRNA-SNHG7/miR-29b/DNMT3A axis affects activation, autophagy and proliferation of hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis. Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology 2021, 45(2), 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L. TGF-β/SMAD pathway and its regulation in hepatic fibrosis. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 2016, 64(3), 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, A.; Toya, H.; Tanahashi, M.; Kurihara, M.; Mito, M.; Iwasaki, S.; Kawamura, Y. Species-specific formation of paraspeckles in intestinal epithelium revealed by characterization of NEAT1 in naked mole-rat. RNA 2022, 28(8), 1128–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J. H.; Kim, S. C.; Kim, K. M.; Jang, C. H.; Cho, S. S.; Kim, S. J.; Ki, S. H. Isorhamnetin attenuates liver fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β/Smad signaling and relieving oxidative stress. European journal of pharmacology 2016, 783, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.-L.; Chang, W.-T.; Hong, M.-Y.; Hung, K.-C.; Chuang, C.-C. J. P. O. Prevention of TGF-β-induced early liver fibrosis by a maleic acid derivative anti-oxidant through suppression of ROS, inflammation and hepatic stellate cells activation. 2017, 12(4), e0174008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Fan, L.; Yin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, H. EWSR1:: SMAD3-rearranged fibroblastic tumor: A case with twice recurrence and literature review. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 1017310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Gu, P.; medicine, t. Rebalancing TGF-β/Smad7 signaling via Compound kushen injection in hepatic stellate cells protects against liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis. 2021, 11(7), e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, C.; Song, K.; Chen, W.; Ungerleider, N.; Yao, L.; Wu, T. The long-noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates TGF-β/Smad signaling through formation of a lncRNA-protein complex with Smads, SETD2 and PPM1A in hepatic cells. PLoS One 2020, 15(1), e0228160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Huang, Y. Liquid–liquid phase separation in diseases. MedComm 2024, 5(7), e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. E. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-β signaling. Cell research 2009, 19(1), 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Wang, L.; Ding, H.; Shao, J.; Chen, A.; Zheng, S. Activation of ferritinophagy is required for the RNA-binding protein ELAVL1/HuR to regulate ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Autophagy 2018, 14(12), 2083–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Bai, D.; Qi, L.; Cao, W.; Du, J.; Gu, C.; Lu, N. The flavonoid GL-V9 alleviates liver fibrosis by triggering senescence by regulating the transcription factor GATA4 in activated hepatic stellate cells. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180(8), 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).