1. Introduction

Global supply chains are becoming increasingly complex, spanning diverse regions, affected by new regulations and digitalized technological infrastructures. This diversity leads to fragmented digital platforms and significant inefficiencies in tracking, verifying, and ensuring the integrity of goods and transactions. Diversified sectors, including telecoms, manufacturing, trade, health, and agriculture, have a high potential for improving their existing processes when Blockchain technologies are applied to their critical use cases that require extensive tracking. The use of Blockchain solutions in these sectors has emerged as an up-and-coming solution, offering traceability, transparency, immutability, and decentralized trust. There have been numerous pilot projects, such as [

1], where governments aim to digitalize existing processes, including trade, to enhance traceability with enhanced security, trust, and reduce end-to-end execution times. The authors in [

2] posit that blockchain technology presents an opportunity to enhance economic collaboration and stimulate economic growth within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. They additionally critique the strategic frameworks employed by various nations in deploying blockchain solutions aimed at transitioning towards digitalized economies. Current implementations predominantly operate as isolated entities, lacking standardized mechanisms to facilitate secure data exchange across organizations and ecosystems. The deployment of these projects using singular blockchain systems without interoperability hampers the realization of blockchain’s potential in critical sectors, such as end-to-end supply chain management across different sectoral use cases, thereby perpetuating inefficiencies that blockchain was initially intended to resolve. As supply-chain tracking is critical for many sectors mentioned previously, the efforts to design and implement an interoperability solution that allows connections of multiple blockchains to each other become a critical research area.

For effective, seamless, and secure tracking of the supply chain in the mentioned sectors, the need for interoperability solutions between different independent parties that serve these sectors becomes a critical requirement for blockchain adoption. However, existing approaches, such as the direct integration of two blockchains, have significant shortcomings. Direct connections between blockchains introduce governance complexity and scalability limits, while another option, called centralized hub-based models, compromises decentralization and trust. These limitations prevent supply-chain networks from achieving the desired levels of visibility, accountability, and efficiency.

To address this gap, this paper introduces Interside, a decentralized side-by-side interoperability framework specifically designed for permissioned blockchains, such as Hyperledger Fabric [

3]. Unlike hub-based or direct-connection solutions, Interside preserves the autonomy of individual networks while enabling secure, verifiable, and auditable cross-chain interactions. The framework is designed to strike a balance between architectural soundness, strong security guarantees, and acceptable performance, offering a scalable pathway for global blockchain-enabled supply chains.

1.1. Problem Statement and Motivation

Permissioned blockchains [

4] offer robust security and trust mechanisms for their registered users. Blockchains in general provide features such as transparency, immutability, and decentralized trust within isolated networks, which do not necessarily address the challenge of limited interoperability among permissioned blockchain networks within global supply chains that span multiple sectors. Without right interoperability solution, permissioned blockchains still lack the support for secure and standardized data exchange across diverse organizational ecosystems utilizing their own blockchain solutions. This shortcoming hampers the achievement of end-to-end visibility and accountability, thereby necessitating organizations to operate in silos despite the adoption of blockchain technologies. Consequently, blockchain networks underpinning globally distributed processes encounter inefficiencies, redundant verification procedures, and increased vulnerabilities in cross-border transactions. This project is motivated by the need for a decentralized interoperability framework that overcomes these limitations. The proposed approach must preserve the autonomy and governance of individual blockchain networks while enabling secure, scalable, and auditable cross-chain interactions. By addressing this gap, the research aims to unlock the full potential of blockchain in global supply chain use cases, delivering visibility, accountability, and efficiency across complex supply chain ecosystems.

1.2. Research Questions & Hypothesis

Building on the motivation to search for an ideal interoperability solution for permissioned blockchains, our study is guided by three core research questions:

RQ1 (Architectural Design): How can a standardized interoperability architecture for permissioned blockchains be designed to overcome the limitations of isolated supply chain systems, while preserving decentralization and governance autonomy of each network?

RQ2 (Security): How can the proposed architecture mitigate the security risks associated with direct interoperabilitysuch as reliance on multiple SDKs, exposure of consensus proofs, and multi-ledger identity managementwhile ensuring trustworthy cross-chain data exchange?

RQ3 (Performance): To what extent can the proposed architecture achieve comparable performance to direct interoperability approaches, while avoiding the bottlenecks of centralized hub-based and direct integrated solutions?

From these research questions, we derive the following hypotheses:

H1 (Architecture): A standardized interoperability architecture for permissioned blockchains can be designed to connect multiple independent supply chain networks while preserving decentralization, governance autonomy, and privacy of each participant, unlike direct or hub-based approaches.

H2 (Security): By isolating interoperability into a dedicated architectural layer and relying on cryptographic anchors, the proposed architecture reduces the attack surface and mitigates security risks such as identity compromise, replay attacks, or central hub failures.

H3 (Performance): The proposed architecture can achieve comparable transaction performance to direct interoperability while avoiding the limitations of centralized hub models, thereby maintaining acceptable efficiency as the number of participants increases.

1.4. Structure of the Manuscript

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows.

Section 2 (Background) introduces the fundamentals of permissionless and permissioned blockchains, followed by an outline of interoperability requirements and use cases in global supply chains.

Section 3 (Related Works) reviews prior research on blockchain interoperability, including dimensions of interoperability, architectural approaches to cross-chain communication, and sector-specific frameworks, before identifying key research gaps that motivate the Interside framework.

Section 4 (Methodology) details the research design, provides an overview of the proposed architecture, and explains the evaluation approach, data models, smart contract roles, and transaction flows underpinning Interside.

Section 5 (Results and Discussion) presents the comparative evaluation results, validates the framework against the stated hypotheses, and discusses implications for supply chain adoption, study limitations, and directions for future research. Finally,

Section 6 (Conclusion) summarizes the contributions of this study and highlights opportunities for advancing blockchain interoperability in permissioned ecosystems.

2. Background

When selecting an interoperability solution for supply chain management and comprehensive end-to-end tracking, it is imperative to first understand the various types of blockchain technologies involved and their compatibility with the chosen interoperability framework. In general, there are two blockchain types:

Permissionless

Permissioned

Permissionless blockchains are primarily utilized in cryptocurrency applications and do not necessitate stringent privacy and trust requirements, thereby allowing widespread user participation and access to services. Conversely, permissioned blockchains require elevated levels of security, privacy, and trust mechanisms, as access is restricted to users who join by invitation and under predefined conditions. These permissioned blockchains are often regarded as private networks, predominantly employed across various industry sectors where privacy and rigorous access controls are required. Before delving into the details of the interoperability requirements, it is essential to understand the compliance of existing blockchain types and their technical coverage needs to ensure the proper usage of blockchain types in the target interoperability solution. This approach will enable the selection of the appropriate blockchain type that aligns with the target interoperability architecture for supply chain use cases.

2.1. Interoperability Requirements in Supply Chain

Global supply chains involve multiple stakeholders, including suppliers, manufacturers, logistics providers, financial institutions, and regulators, each using different digital platforms, standards, and governance rules. This requires a thorough consideration of permissioned blockchains that enable multi-party, multi-user transactions with private handling. This diversity, created by multiple stakeholders, creates significant challenges in achieving transparency, traceability, and trust throughout the entire supply chain stakeholders. While blockchain technologies offer immutability and decentralized trust within single networks, the lack of interoperability between different blockchains prevents the smooth and verified exchange of data among stakeholders.

According to Kshetri [

5], the successful adoption of blockchain in supply chains depends on developing interoperability standards that allow networks to exchange data without compromising autonomy or security. Hardjono [

6] emphasizes that interoperability must address not only the technical aspects of cross-chain communication but also governance, scalability, and trust management. Belchior et al. [

7] further highlight that without common standards, organizations risk replicating silos on a distributed ledger, undermining the efficiency gains blockchain was meant to deliver. Moreover, achieving blockchain interoperability in supply chains necessitates addressing key issues, such as data fragmentation, regulatory compliance (e.g., customs regulations or trade laws), and ensuring reliable provenance across multiple participants and jurisdictions. Identifying the supply-chain use cases that most require blockchain interoperability is therefore essential for designing suitable solutions.

2.2. Blockchain Interoperability Use Cases in Supply Chain

Supply chains, much like telecommunications, are heavily regulated, especially in customs clearance and financial transactions that involve critical requirements for security, scalability, and trust. Interoperability enables decentralized decision-making across multiple actors, improving efficiency and reducing disputes. Below are the predominant supply-chain applications where blockchain interoperability is essential.

2.2.1. Provenance and Traceability

A key challenge within global supply chains involves ensuring the authenticity of products, accurately tracking their origins, and validating certifications across diverse jurisdictions. For instance, sectors such as food safety, pharmaceuticals, and luxury goods necessitate verifiable evidence of provenance (Kshetri [

5]). Blockchain interoperability enables secure data exchange among independent networks, including raw material suppliers, manufacturers, and logistics providers, regarding certifications, inspections, and handling conditions. In the absence of interoperability, stakeholders are compelled to duplicate verification efforts, thereby reducing efficiency and increasing the risk of fraud. A decentralized interoperability framework enables different blockchain networks to share validated provenance data while maintaining their autonomy, thereby ensuring comprehensive end-to-end traceability (Belchior et al. [

7]). The provenance and traceability of parts and goods can be applied to various sectors, including telecommunications, manufacturing, and energy.

2.2.2. Trade Finance and Customs Clearance

Another critical aspect of blockchain interoperability entails the integration of financial services such as banking institutions, insurance firms, and fintech providers with logistics and customs networks. Traditional trade finance processes are often characterized by their sluggishness, labor-intensive nature, and susceptibility to disputes. The implementation of interoperable blockchain systems has the capacity to streamline these processes by enabling financial institutions to access verified order and shipment data directly from supply chain networks (Hardjono, [

6]). Likewise, customs authorities can authenticate documentation, including invoices and certificates of origin, and perform compliance verification across borders without reliance on manual reconciliation. Such interoperability possesses the potential to significantly reduce delays, diminish instances of fraud, and enhance adherence to international trade regulations (Belchior et al., [

7]).

2.2.3. Logistics and Delivery Coordination

Efficient logistics management requires real-time coordination between producers, freight carriers, port operators, and last-mile delivery providers. Today, this coordination is hindered by fragmented IT systems and limited visibility into data. By leveraging interoperable blockchain frameworks, logistics actors can exchange verified delivery records, shipment statuses, and route optimizations without relying on centralized intermediaries. This ensures faster decision-making, reduces disputes over liability, and improves overall efficiency in global trade flows (Kshetri [

5]; Belchior et al. [

7]).

2.3. Supply Chain in Telecommunication

Blockchain interoperability also presents significant opportunities in the telecom supply chain by addressing challenges related to provenance, logistics, and cross-operator coordination. Interoperable blockchains can secure the provenance of devices and components by linking records from manufacturers, logistics providers, and operators, thereby reducing counterfeit risks in network infrastructure. In multi-operator environments, particularly those with shared 5G infrastructure, interoperability enables the transparent reconciliation of usage data and cost-sharing, eliminating the need for centralized brokers. Roaming and settlement processes also benefit, as interoperable permissioned blockchains between international operators support real-time exchange of authenticated records, reducing settlement delays and fraud. In [

8,

9], various use cases are discussed for enhancing supply chain functions through the use of blockchain interoperability required for telecoms. Within logistics, interoperability provides end-to-end visibility by connecting customs, equipment manufacturers, and telecom operators, ensuring auditable supply flows for towers, fiber cables, and antennas. Service-level agreements (SLAs) in Network-as-a-Service models are further strengthened when monitoring data across different actors’ blockchains can be cross-verified, thereby minimizing disputes. Finally, in the broader context of smart cities and IoT(Internet of Things) ecosystems, telecom blockchains can interoperate with those in adjacent sectors to enable the secure and trusted exchange of sensor and service data. Collectively, these use cases underscore the importance of interoperability as a crucial enabler of efficiency, transparency, and trust in modern telecom supply chains.

3. Related Works

Research on blockchain interoperability has experienced significant growth in recent years, resulting in the development of various frameworks, taxonomies, and experimental implementations. A comprehensive review of these contributions is imperative to contextualize this research within the broader academic discourse and to identify the existing gaps that underpin the proposed framework.

This section, commencing with an examination of current research on interoperability within supply chain applications, emphasizes practical integration aspects, such as blockchain-to-enterprise system connections and intra-chain decentralized application (dApp) [

10] interoperability. Subsequently, it analyzes how architectural trade-offs inherent in different blockchain designsincluding permissionless and permissioned systemsaffect interoperability requirements. Building upon this foundation, the section further reviews definitions and dimensions of interoperability, technical architectures facilitating cross-chain communication, and the challenges specific to permissioned blockchain environments.

Finally, sector-specific use cases, security and governance trade-offs, and comparative evaluations of existing frameworks are discussed. These related works collectively underscore the limitations of current approaches and provide the rationale for the design of the Interside interoperability framework proposed in this paper.

3.1. Practical Interoperability Dimensions in Supply Chains

Most research into blockchain use cases in supply chains has focused on deploying a single blockchain network and enabling interoperability with internal enterprise applications through dApps. Ren et al. [

11] describe three main approaches to blockchain interoperability: interoperability between a blockchain and external systems, interoperability between dApps operating on the same blockchain, and interoperability between independent blockchains. The first two approaches have dominated supply-chain projects to date. For example, many studies examine the integration of blockchain with enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems or IoT platforms to enhance traceability and data sharing, while others demonstrate intra-chain dApp interoperability for provenance and auditing purposes. Authors in [

12] discuss integration strategies of ERP with blockchain for managing Supply Networks. They mention that supply chain networks are newly and frequently being named as supply networks, which have a potential benefit for multi-party collaboration when blockchain and smart contracts are deployed. Mabrook et al. [

13] extend this perspective by surveying blockchain interoperability specifically in supply chains, classifying seven distinct approaches: isolated, network, structural, semantic, specification, platform, and organizational interoperability. Their findings indicate that structural and semantic interoperability are relatively well covered in ERP/IoT integration and provenance applications, whereas platform- and organizational-level interoperability, especially across independent blockchains, remain underexplored.

3.2. System Design Considerations and Trade-Offs for Interoperability

In [

14], the authors provide a comprehensive survey that compares permissionless and permissioned networks through the lens of the CAP (Consistency, Availability, Partition tolerance) theorem [

15]. According to their findings, permissionless networks prioritize availability and partition tolerance. Bitcoin [

16], recognized as the first-ever permissionless cryptocurrency network, operates as a distributed consensus platform utilizing the proof of work (PoW) [

17] consensus protocol to validate transactions. In this framework, Bitcoin initiates transactions and incorporates them into blocks without employing complex logic. Consequently, this results in Bitcoin being a non-Turing complete solution due to the absence of a loop mechanism [

18]. In contrast, permissioned blockchain networks like Hyperledger leverage Smart Contracts [

19] can execute custom processes on a blockchain distributed ledger (DLT) and ensure finalization of these transactions, thus achieving Turing completeness. These networks can implement a more sophisticated consensus mechanism that involves multiple steps, facilitated by various modules working together to reach the final consensus. Therefore, permissioned networks tend to prioritize consistency over availability, which is specifically characteristic of permissionless networks. In [

20], even the authors propose a new architectural framework to redefine CAP for blockchain as Consensus achievement (C), Autonomy (A), and entropic Performance (P). In [

20], the proposed framework concentrates on a single blockchain with distributed nodes. This shows that a blockchain solution chosen by a supply chain not only needs a Turing-complete requirement, but also needs to fulfill such a new approach for the CAP theorem offered for blockchain. A candidate interoperability solution that connects two or more blockchains shall not endanger these basic requirements for consensus achievement, autonomy, and entropic performance, thus providing a Turing-complete process. A singular blockchain for trade network [

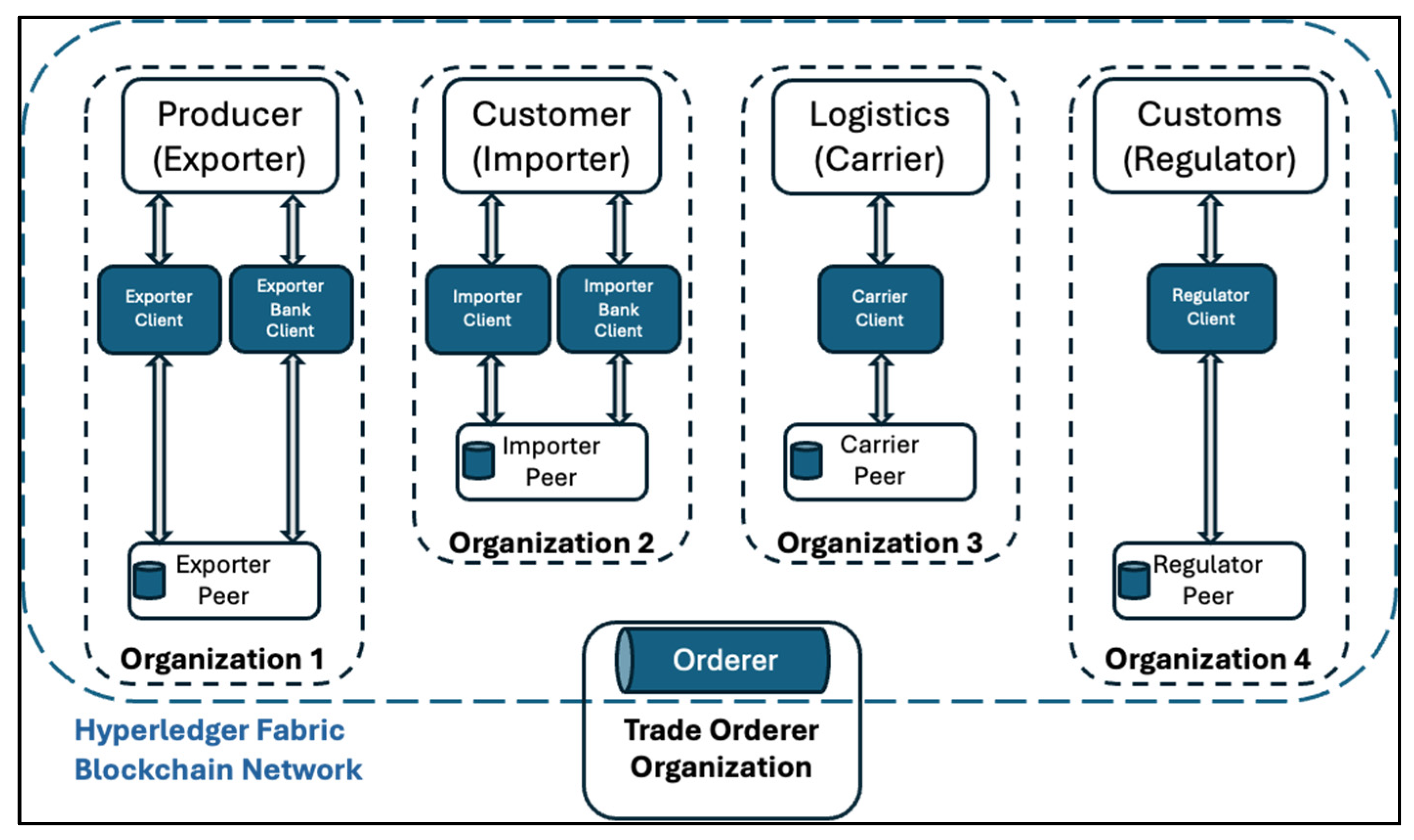

21] built using Hyperledger Fabric is illustrated in

Figure 1. This approach shows integration of all access rights, trust anchors, and Turing-complete smart contract processes into one single platform. Such an architectural approach using a singular blockchain network compromises the autonomy of each involved party (producer, customer, logistics, customs, etc) and enables a super administrator right to a party, a person, or an organization to overrule the whole network. Therefore, each party must comply with the specifications deployed and applied by the ruling authority. This approch clearly contradicts with the decentralized feature of blockchain.

3.3. Definitions and Dimensions of Blockchain Interoperability

As a deployment of a singular blockchain introduces significant disadvantages, the dimension for an interoperability needs to be further discussed. For this study, the platform and organizational dimensions highlighted by Mabrook et al. are particularly significant. Platform-level interoperability refers to the ability of heterogeneous blockchains (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric, Ethereum [

22], Corda [

23]) to exchange data without requiring a shared consensus mechanism. In contrast, organizational interoperability ensures that independent networks can collaborate without compromising their autonomy in governance. In this sense, using a singular blockchain to deploy such a supply chain network is not a viable option. For deploying a final interoperability architecture, the platform and organizational dimensions covered by Mabrook et al. are critical for supply-chain ecosystems where suppliers, producers, logistics providers, customs authorities, and financial institutions must remain self-governed yet interlinked.

3.4. Technical Architectures for Cross-Chain Communication

The technical architecture of blockchain interoperability defines how independent blockchain systems interact to share data, verify events, or execute cross-chain transactions. Various models have been proposed in the literature and industry implementations, each differing in terms of decentralization, scalability, trust assumptions, and coupling between participating networks. The three predominant architectures for cross-chain communication are: direct (point-to-point), hub-based, (often called intermediary), and middleware-based approaches.

3.4.1. Direct Integration (Point-to-Point Bridges)

Direct integration involves creating custom connections between two blockchain networks using bridge contracts, relayers, oracles [

24], or APIs. Each bridge handles data formatting, event detection, and message relaying in a bespoke manner. While direct connections can be high-performance and tailored to specific use cases, they are inherently non-scalable, each new blockchain added to the network requires n(n−1)/2 connections for full interoperability.

These architectures also expose security risks such as replay attacks [

25], consensus manipulation [

26], and double spending [

27,

28], particularly when cross-chain validation relies on off-chain relayers. Governance becomes complex, as both chains must agree on shared protocols, identity mapping, and data validation rules, often requiring manual trust establishment between participants.

3.4.2. Hub-and-Spoke Models/Intermediaries

Hub-based models centralize interoperability through a single coordination layer, often referred to as an interoperability hub, router, or backbone. All participating blockchains connect to this hub, which mediates message passing, state synchronization, and data translation. This design significantly simplifies the addition of new blockchains and reduces redundant connections, offering high connectivity with minimal configuration overhead.

Notable examples include Cosmos IBC [

29,

30,

31], Polkadot’s Relay Chain [

32], and Hyperledger Cactus’s [

33] pluggable interfaces. However, these models often re-centralize trust and introduce a single point of failure (spof), potentially violating the decentralized ethos of blockchain. Additionally, they may struggle with heterogeneous permission models, especially when permissioned and permissionless blockchains coexist within the same ecosystem.

3.4.3. Middleware and Protocol-Based Interoperability

Middleware-based solutions abstract cross-chain logic into dedicated interoperability layers that sit above existing blockchains. These platforms offer standard APIs, protocol adapters, and governance isolation mechanisms to enable message passing without exposing internal consensus or identity structures. Middleware can also manage asynchronous communication, version control, and policy enforcement across chains.

Examples include Hyperledger Cactus, Quant’s Overledger [

34], and LayerZero [

35]. These solutions excel in protocol modularity and governance decoupling; however, they often introduce additional latency, resource overhead, and complexity during deployment, particularly in high-throughput environments such as supply chains.

In summary, existing cross-chain architectures present a spectrum of trade-offs. Direct bridges offer performance at the cost of scalability and security. Hub-based systems simplify integration but reduce decentralization. Middleware strikes a balance but introduces technical complexity and potential bottlenecks. These limitations reinforce the need for a decentralized, policy-aware, and auditable solution like Interside, which isolates interoperability into a secure, side-by-side layer without compromising governance or scalability.

3.5. Supply Chain-Specific Interoperability Frameworks

Blockchain’s application in supply chains has evolved from proof-of-concept pilots to production-grade systems in logistics, trade finance, and regulatory compliance. However, many of these implementations remain fragmented, relying on isolated blockchains or siloed applications that cannot interoperate with other networks. As a result, platform-level and organizational-level interoperability challenges persist particularly in environments where multiple independent stakeholders (e.g., manufacturers, customs agencies, financial institutions) must collaborate without ceding governance control. Early efforts in blockchain-enabled supply chains typically involved integrating a single permissioned blockchain platform (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric) with internal enterprise systems, such as ERP or IoT platforms. These efforts focused primarily on semantic and structural interoperability, ensuring that data formats and process flows were compatible. However, platform-level interoperability, where entirely different blockchain infrastructures must exchange data securely, remains underdeveloped. Several studies (e.g., Belchior et al., 2021; Kshetri, 2025) highlight that organizational interoperability, the ability for independently governed networks to collaborate without pre-shared consensus or identity management is a fundamental requirement in supply chains. For example:

In trade finance, banks and customs agencies need access to validated shipment records without participating in the same blockchain network.

In provenance tracking, logistics firms, producers, and inspectors may each maintain separate blockchain systems yet must ensure end-to-end data continuity.

In regulatory audits, agencies require verifiable and immutable access to transaction histories, even if the networks involved do not expose internal consensus protocols.

Frameworks such as TradeLens [

36,

37] and We.Trade [

38] attempted to address these issues through semi-centralized architectures but have faced criticism for relying too heavily on trusted intermediaries or shared consortium governance, which limits scalability and generalizability.

This analysis highlights an ongoing disparity between current frameworks and the intricate multi-actor landscape inherent in global trade. It underscores that no single platform or entity possesses the authority to unilaterally dictate integration terms. These findings emphasize the critical need for genuinely decentralized interoperability solutions, specifically designed to accommodate the permissioned and multi-jurisdictional characteristics of supply chains.

3.6. Security, Governance, and Performance Trade-Offs

The design of any blockchain interoperability framework involves a careful balancing of security, governance, and performance. These three dimensions often exist in tension, and optimizing for one may compromise the others.

3.6.1. Security

Security concerns in blockchain interoperability primarily stem from:

Cross-chain replay attacks

Message spoofing

State inconsistency between ledgers

Identity compromise across ledgers

Direct bridges between chains are especially vulnerable, as they may require exposing consensus proofs, handling multiple SDKs, and sharing sensitive identity attributes across networks. In permissioned environments, where strict access control is enforced, such exposure is often unacceptable. Moreover, the absence of a standardized cryptographic anchoring mechanism introduces ambiguity in transaction finality across chains. Direct integration often exposes both integrated networks’ access policies, trust anchors and cryptographic proofs to each other for the execution of smart contracts.

3.6.2. Governance

Centralized or consortium-based hub models streamline interoperability by implementing a standardized governance framework. Nonetheless, these models frequently contravene fundamental blockchain principles such as decentralization and autonomous operation. In the context of supply chains, it is imperative that stakeholders including governmental agencies, logistics companies, and financial institutions maintain full authority over their ledger governance, particularly regarding legal and compliance considerations. Consequently, interoperability architectures must be devised to avoid compromising local policies, membership criteria, or consensus mechanisms. Conversely, in direct models, while both networks typically preserve their autonomy, the vulnerability introduced by the exposure of security components, as discussed in section 3.6.1, undermines this autonomy.

3.6.3. Performance

Performance trade-offs include:

While direct bridges offer low latency for specific use cases, they scale poorly as more networks are added. On the other hand, middleware solutions that abstract interoperability often introduce additional overhead. A poorly designed interoperability layer can become a bottleneck, especially when cross-chain validation is computationally intensive. Recent studies such as [

39] emphasize the need for architectures that modularize cross-chain interactions, isolate security domains, and maintain asynchronous communication to preserve both performance and resilience. Performance was a known issue for blockchain networks since the launch of Bitcoin. Ethereum was introduced to improve the limitations of Bitcoin, such as performance and Turing completeness. Finally, Solana [

39] was introduced to provide a significant performance improvement for permissionless networks as Ethereum’s improvements on performance were limited. In this respect performance will continue to stay as an important topic and need to be addressed in a candidate interoperability by considering integrated blockchain networks. Hyperledger Fabric has a proven performance results based on [

40,

41]. This lead this study to choose Hyperledger Fabric as a strong candidate.

All these constraints inform the design goals of the proposed Interside framework, which aims to achieve:

Security through cryptographic anchoring and verification

Governance autonomy via side-by-side integration without shared consensus

Performance efficiency through minimal coupling and asynchronous communication

3.7. Gaps in Current Research and Motivation for Interside

Despite significant progress in the design and evaluation of blockchain interoperability frameworks, existing solutions remain largely inadequate for the needs of permissioned blockchain ecosystems in global supply chains. Most prior research has focused on direct bridges or centralized hubs that facilitate cross-chain communication but fail to fully address the unique challenges posed by regulated, multi-organizational environments.

First, direct point-to-point integrations often assume a homogeneous governance environment and require tight coupling between blockchains, introducing severe scalability and governance overhead. These models also increase the attack surface, as each new connection introduces custom SDKs, message handlers, and cross-ledger validations that must be maintained securely.

Second, hub-and-spoke models, while reducing implementation complexity, often re-centralize trust, which undermines the very decentralization principles that blockchain technology aims to uphold. By introducing a central coordination entity, these solutions oppose the need for network autonomy, especially in supply chains where each participant (e.g., customs authorities, logistics firms, banks) must maintain full control over their own data and governance processes.

Third, middleware-based interoperability solutions are often created for public blockchains and lack essential access control and identity management features needed by permissioned networks. Additionally, most academic and commercial implementations overlook diverse consensus mechanisms, non-standard transaction models, and jurisdictional privacy requirements typical in cross-border trade environments. These gaps point to the need for a new class of interoperability framework that:

Preserves the autonomy and governance independence of each network.

Ensures cryptographic verifiability and auditable communication.

Scales horizontally without requiring centralized intermediaries.

Aligns with blockchain-specific system constraints such as Turing completeness, CAP trade-offs, and regulated permissioning.

To meet these requirements, this study introduces Interside, a new side-by-side interoperability framework specifically designed for permissioned blockchain systems. Interside allows secure, decentralized cross-chain interactions without relying on centralized trust anchors or shared consensus mechanisms. The side-by-side architecture was chosen based on the comparison approach shown in [

8], which can be considered a preliminary study. The approach in [

8] analyzes different blockchain interoperability solutions for telecom interoperability and concludes that the side-by-side architecture has the greatest potential. By abstracting interoperability into a dedicated architectural layer, the framework offers a flexible, performance-conscious, and auditable pathway for interconnecting heterogeneous supply chain networks. The design of Interside directly responds to the limitations identified in current literature and aims to fill the gap between academic models and real-world, production-grade interoperability demands in regulated industries. The following methodology section elaborates on the design and implementation of this approach.

4. Methodology

This study adopts a design science research methodology to develop and evaluate a side-by-side interoperability framework, Interside, for supply chains. The methodology follows a three-phase process: (i) problem identification and requirement analysis, (ii) framework design and implementation, and (iii) evaluation through architectural validation and performance assessment. This structured approach ensures that the framework is both theoretically grounded and practically applicable within homogeneous and heterogeneous supply-chain environments.

4.1. Research Design

The research design is guided by insights from the related works (

Section 3), which highlighted the scarcity of interoperability solutions at the platform and organizational levels. These gaps informed the central research questions (RQ1–RQ3) and hypotheses (H1–H3) introduced in

Section 1.2. Specifically, the literature emphasized the need for architectures that preserve governance autonomy (H1), mitigate security risks in cross-chain communication (H2), and maintain comparable performance without centralization bottlenecks (H3).

To address these objectives, this study employs a design science research methodology, structured into three phases:

Problem identification and requirement analysis, where interoperability challenges from the literature are translated into architectural requirements.

Framework design and implementation, involving conceptual modeling and prototype development in Hyperledger Fabric and using Weaver [

40] architecture to operationalize the Interside architecture.

Evaluation through architectural validation and performance testing, where the proposed solution is benchmarked against direct and hub-based models using qualitative and quantitative methods.

This structured approach ensures that the Interside framework is both theoretically grounded in prior research and empirically validated for practical deployment in heterogeneous, multi-stakeholder supply chain ecosystems.

4.2. Architecture Overview

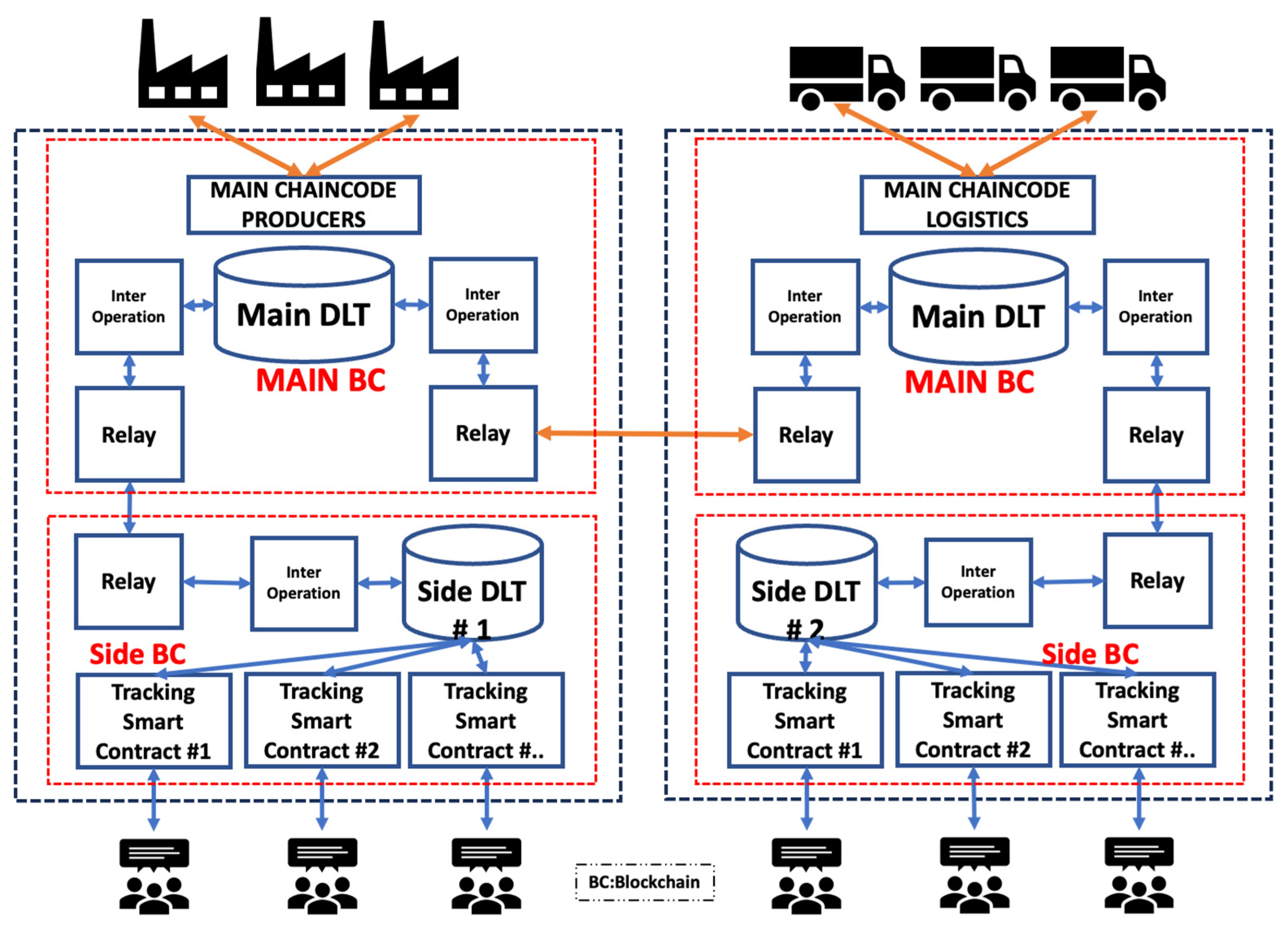

The Interside framework utilizes the Weaver architecture to establish a decentralized, side-by-side interoperability framework that integrates multiple permissioned blockchains without reliance on centralized hubs. Its design incorporates interoperability chaincode modules, cryptographic anchors, and relay components to enable secure data exchange. Each participating network maintains its own consensus mechanisms, membership service provider (MSP), and governance structures, thereby ensuring operational autonomy. The interoperability layer orchestrates cross-chain requests and responses, enforces access controls, and ensures auditability through signed proofs and transaction logs. In

Figure 2, the proposed interoperability architecture is illustrated. The interoperation code is triggered by events from the main chaincode (executed by producers, logistics, etc), which converts data from the distributed ledger technology (DLT) structure into a simplified data format. At this level, isolation of the autonomous network is achieved. The interoperation mechanism is only an event listener. This interoperation mechanism transmits the data to the relay component, which subsequently communicates with the relay component of the target blockchain (BC) network. Both the relay and interoperation components are part of the Weaver solution. The main chaincode of each network is adapted to support both interoperability functions and auxiliary BC layers. The side BCs enable end-to-end traceability within the supply chain process. When the main chaincode in the primary BC executes a data transfer between independent blockchains, the same chain code starts another process in the relay integrated to the side blockchain. This process transfers the same or a limited portion of the data to the side chain, facilitating access to tracking information. This approach ensures that the main chain remains autonomous, with tracking data accessible solely through the side chain by end users with permissioned access rights.

4.3. Evaluation Approach

To evaluate the framework, the study applies both qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitatively, the architecture is benchmarked against design requirements derived from the literature (security, scalability, governance autonomy). Quantitatively, a preliminary performance testing is conducted in a simulated multi-network supply-chain environment, measuring transaction throughput compared to direct interoperability and Interside. These evaluation results provide evidence on whether the proposed framework achieves comparable efficiency while offering stronger decentralization and security guarantees.

4.4. Data Models

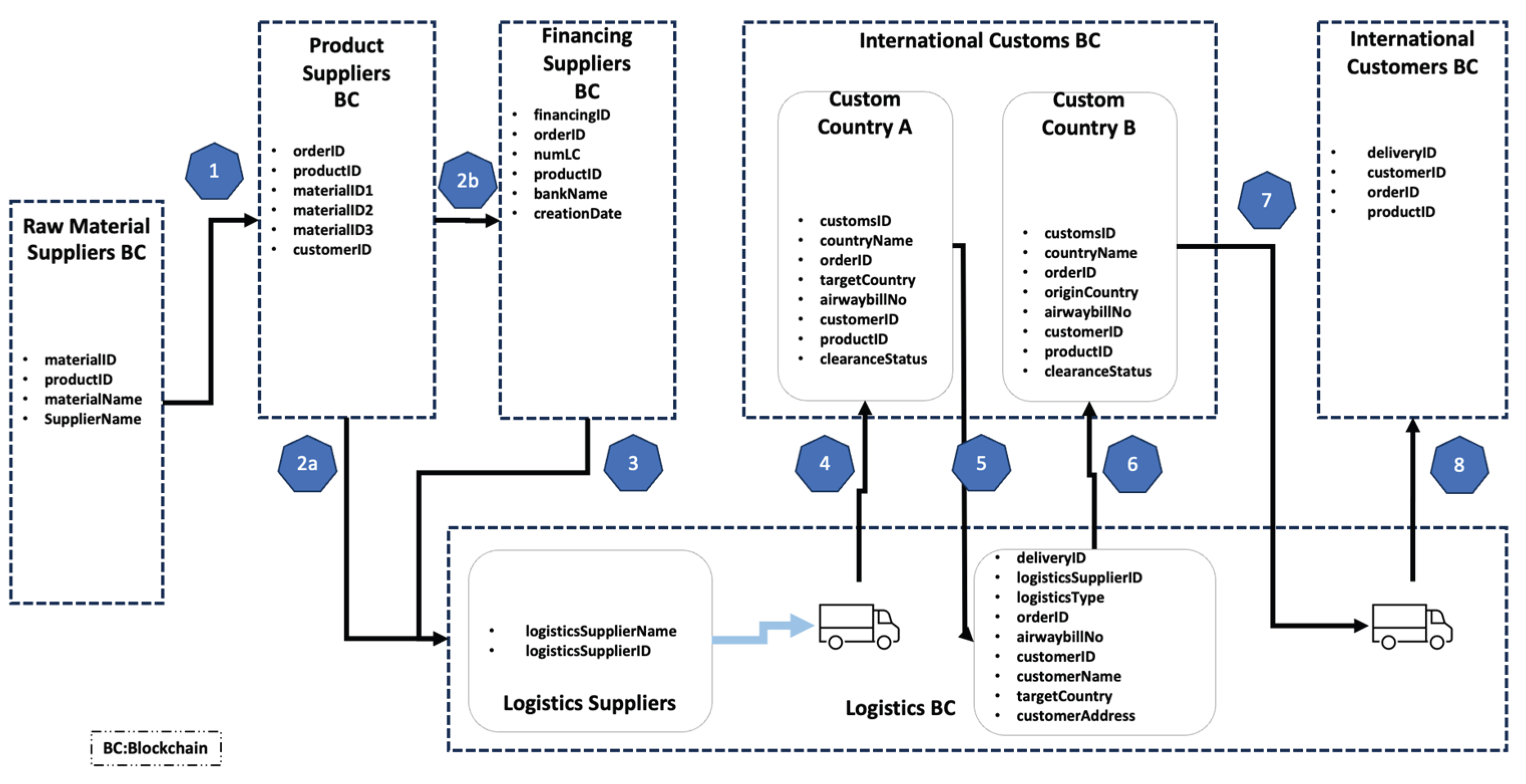

Each supply-chain entity, such as raw material suppliers, producers, logistics providers, financial institutions, and customs authorities, maintains its own blockchain network with dedicated data models. Core records include orders, products, shipments, and certifications, each enriched with metadata such as Order ID, Product ID, Delivery ID, Customs ID, Quantity, Timestamp, and provenance information. Interoperability transactions are represented as signed claims, which encapsulate proofs of authenticity and origin before being shared across networks. By standardizing data structures in this way, the framework ensures that cross-chain communication remains semantically consistent while allowing each network to retain local schema extensions. The

Figure 3 illustrates the overall data model that can be deployed in a traditional supply chain process for international trade. This data model can be adapted to other supply chain models in different sectors. The process is numbered as a pre-proposed model and can be adapted to different use cases by using unique id concept based on the transaction flow.

Each network owns a unique ID, such as orderID, deliveryID, that is transferred as simple data from one network to another. Once these unique IDs are created, they are trackable through side BCs.

4.5. Smart Contract Roles

The interoperability layer relies on two categories of smart contracts deployed across the networks:

Together, these smart contracts enforce decentralized access control, provenance validation, and selective disclosure policies, ensuring that only authorized data is exchanged while maintaining privacy and compliance.

4.6. Cross-Chain Transaction Flow

The end-to-end interoperability process follows a structured transaction flow. A request is initiated in one network (e.g., a producer requests the delivery status of raw materials) via a side blockchain using available side-chain smart contracts. Finally, the Transaction Viewer Contract enables stakeholders, such as banks or regulators, to inspect the verified data. This workflow ensures one-directional yet auditable information exchange, reflecting the operational needs of supply-chain ecosystems while preserving network autonomy. Having described the data structures, smart contract roles, and transaction workflows that underpin the Interside framework, it is now necessary to position the solution against existing interoperability approaches. While direct bridges, hub-based systems, and middleware frameworks such as Hyperledger Cactus each address interoperability to some extent, they exhibit different limitations in terms of scalability, governance autonomy, and security. The following section presents a comparative evaluation of the results of these architectures, highlighting how Interside advances beyond prior models in meeting the requirements identified in this research.

4.7. Comparative Evaluation of Interoperability Architectures

To benchmark the proposed Interside framework against existing interoperability solutions, a structured evaluation framework was defined. This framework identifies twelve criteria particularly relevant to permissioned blockchain ecosystems and supply chain interoperability: decentralization architecture, interoperability mechanism, network decoupling, trust assumptions, cross-chain integration, smart contract roles, security identity separation, advanced security, advanced policy management, auditability, production readiness, and performance. Two representative approaches were selected for comparison: Direct interoperability models (e.g., point-to-point bridges) and Hyperledger Cactus, a pluggable middleware framework. In

Section 5, the results of this comparative analysis are presented, highlighting how Interside addresses the limitations identified in prior works while balancing decentralization, security, and efficiency.

4.7.1. Decentralization Architecture

Decentralization is a crucial approach for many sectors where autonomy and sovereignty are essential. Especially in sectors such as healthcare [

44], the sovereignty of critical data is crucial. The planned interoperability solution aims to preserve the integrity of the decentralized blockchain architecture while avoiding the introduction of any centralized components. The addition of intermediary or broker modules would shift the system toward centralization, creating a single point of failure when an intermediary is not accessible.

4.7.2. Interoperation Mechanism

The interoperation mechanism pertains to the foundational architecture and methodologies employed to enable communication across blockchain networks. This mechanism encompasses various attributes, including its synchronous versus asynchronous operation, whether it is conducted on-chain or off-chain, and whether it is event-driven or manually triggered. Direct Fabric SDK-based [

45] integration using a dApp necessitates manual reading and writing operations executed by an application interfacing with two distinct networks. Hyperledger Weaver implements an intent-based model that is complemented by cryptographic proofs and relay services. In contrast, Hyperledger Cactus offers pluggable connectors and APIs, which facilitate broader compatibility with diverse Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLTs). The extent to which the mechanism is standardized and modular significantly influences its scalability and adaptability. Various interoperability techniques as stated in [

46] offer different mechanisms that need to be aligned and confirmed with the expected requirements. [

46] discusses three different techniques for interoperability: chain-based, dApp-based, and bridge-based. The interoperation mechanism for each of these options needs to be carefully considered and confirmed with the final requirements.

4.7.3. Network Decoupling

This illustrates the degree of interconnection between two or more blockchain networks during interoperation. In tightly coupled systems, networks possess knowledge of each other’s schemas, identities, and runtime states, which constrains flexibility. Conversely, loosely coupled networks, as exemplified by Weaver or Cactus, abstract these interactions through protocols or plugins. This abstraction diminishes the integration burden and facilitates independent operation.

4.7.4. Trust Assumptions

Trust is a vital factor for sectors like finance, healthcare, and government that heavily rely on operational processes and applications involving sensitive and private data. For the case of decentralized finance (DeFi) [

47], this becomes even more critical when blockchain solutions are deployed. If flawed or weak trust assumptions are adopted by the underlying solutions, security and privacy risks may emerge. Any process or application designed for critical tasks must implement strong trust mechanisms. This concept relates to the implicit expectations each network has regarding the other during their interaction. Direct approaches often assume complete trust in the accuracy of the other party’s information, while systems like Weaver and Cactus actively verify cross-network data using cryptographic assertions or validator attestations. Generally, systems that operate under minimal trust assumptions exhibit a higher level of security.

4.7.5. Cross-Chain Integration

The cross-chain integration delineates the existence of a dedicated service responsible for facilitating message transmission between various networks. Interside incorporates a relay that actively monitors events and submits verification proofs to designated target networks. Similarly, Cactus employs connectors or registries that serve as relays. In instances of direct integration, this relay function is often absent, thereby imposing greater obligations on the application layer. The implementation of relays enhances the decoupling of components and fosters reactive interoperability.

4.7.6. Smart Contract Roles

The regulations governing smart contracts, commonly referred to as chain-code, elucidate their function within interoperability contexts. In scenarios involving direct integration, these contracts frequently lack awareness of cross-chain logic. Smart contracts are crucial for Turing-complete processes; however, they should not be used directly for final interoperability layer that interfaces with target blockchains. Solutions as [

48] uses smart contracts as the main mechanism to achieve interoperability. Such direct smart contract-based integrations carry potential risks. The Interside framework necessitates that chaincode shall be utilized to validate proofs, manage state transitions, and enforce access controls. Conversely, Cactus may depend less on smart contracts, delegating logic to plugin connectors, although the integration of smart contracts can enhance the overall trust framework. Increased on-chain engagement significantly improves auditability and transparency.

4.7.7. Security Identity Separation

This separation delineates the distinction between identities employed for interoperability such as relays, validators, or service agents and application-level user identities, both in logical and cryptographic terms. The separation of identities is essential for maintaining minimal privileges and establishing clear delineations between operational and user contexts, thereby mitigating risks in intricate environments.

4.7.8. Advanced Security

Transport Layer Security (TLS) [

49] facilitates encrypted communication, whereas Certificate Authorities (CAs) authenticate the identities of entities. In the context of interoperability, it is crucial that both TLS and CA mechanisms are upheld across blockchain boundaries, rather than being confined to a singular network. Systems such as Weaver and Cactus effectively integrate these protocols at both interoperability and network levels, thereby supporting mutual TLS and the use of trusted root certificates.

4.7.9. Advanced Policy Management

Many sectors, such as healthcare [

50], require enhanced policy management due to the criticality of the data processed in blockchain network-based solutions. An advanced interoperability system must adequately facilitate the lifecycle management of keys and certificates, which includes revocation in the event of key compromise and rotation for regular maintenance and security hygiene. This can be considered as an advanced policy enforcement and automation of interoperability transaction execution process. Traditional Fabric SDK methods frequently demonstrate deficiencies in automating these processes. In contrast, Interside utilizes Management Service Provider (MSP) revocation lists, while Cactus incorporates modular security components that can enforce the policy of key rotation.

4.7.10. Auditability

Many blockchain solutions are built as auditable solutions [

51,

52]. This is also a critical requirement for blockchain interoperability. Auditability refers to the extent to which actions undertaken during interoperability can be traced, verified, and replayed. This encompasses signed messages, logs, state changes invoked by chaincode, and events related to proof verification. Solutions such as Weaver, which utilizes signed view proofs, and Cactus, which incorporates validator attestations, offer inherent audit trails. Conversely, manual methods seldom provide such capabilities.

4.7.11. Production Readiness

This option assesses whether a system is mature enough for deployment in real-world environments. Indicators include test coverage, version stability, production use cases, documentation quality, and active maintenance. Direct SDKs are stable but limited in functionality. Weaver is research-grade but progressing. Cactus is modular, under active development, and already deployed in some enterprise trials.

4.7.12. Performance

This option evaluates the latency, throughput, and overhead associated with interoperation logic. Systems that employ cryptographic proofs or multi-step verification processes may exhibit reduced speeds but enhanced security. Furthermore, performance is contingent upon factors such as orchestration design, message queuing, and relay throughput. Direct SDK integrations provide expedited pathways; however, they may compromise safety. Interside and Cactus enhance event-driven, secure interoperability within reasonable parameters. Existing literature, such as [

53], shows degrading performance results when complex Hyperledger architectures using multiple organizations and peers are deployed.

The comparative analysis of existing interoperability approaches highlights a persistent gap: no current solution simultaneously achieves scalability, governance autonomy, strong security guarantees, and production readiness for permissioned blockchain networks in global supply chains. While direct and hub-based models offer certain performance or integration benefits, they introduce unacceptable trade-offs in decentralization and trust. Middleware approaches, though flexible, often struggle with latency and governance heterogeneity. These findings reinforce the need for a decentralized, side-by-side interoperability framework. Building on this gap, Interside architectural framework is demonstrated in this section which holds strong foundation for the ideal interoperability solution for supply chain. The comparative results are illustrated in section 5 and the results are discussed to prove the viability of the offered architecture.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the evaluation of the proposed Interside framework, with a focus on its performance relative to existing interoperability approaches. The discussion is structured around the evaluation framework introduced in

Section 4.7, which considers decentralization, security, governance autonomy, and performance trade-offs as key criteria. Results are first reported through a comparative analysis of Interside, Direct interoperability models, and Hyperledger Cactus. The section then explores how Interside addresses the identified research hypotheses (H1–H3), followed by a discussion of implications for supply-chain adoption, limitations of the current study, and directions for future research.

5.1. Comparative Results

The comparison and evaluation results of interoperability solutions are displayed in

Table 1. Based on the requirements and essential feature set, researchers can identify the most suitable solution for specific use cases in their related sectors.

The results illustrate the architectural advantages of Interside across nearly in all critical dimensions:

Decentralization & Trust Assumptions: Interside enforces side-by-side execution, eliminating centralized coordination and preserving full network autonomy, unlike Cactus and direct bridges that rely on centralized hubs or trusted middleware layers.

Security Features: Interside offers strong identity separation, advanced policy enforcement, and cryptographic auditing, which are vital in multi-jurisdictional supply chain contexts where compliance and access control are mandatory. Interside built on Hyperledger already proves to be as strong platform for security [

54]

Network Decoupling: Interside is designed to enable interoperation between independently governed permissioned networks without forcing consensus homogenization or identity sharing.

Smart Contract Integration: Interside allows each blockchain to retain its own smart contract logic, enabling localized decision-making while still participating in cross-chain transactions.

Performance: The only trade-off appears in throughput performance, where direct bridges are faster in isolated use cases. However, this comes at the cost of security, auditability, and scalability, which are non-negotiable in regulated supply chain environments. Interside built on Hyperledger Fabric provides further scalability improvement by customer designs such as [

55] when it is required

5.2. Preliminary Performance Results

The preliminary performance evaluations were carried out on a single macOS computer with minimal network latency. The Relay and Interop components of both networks in the Interside solution significantly impact the total processing time for the read process. Conversely, update/insert latency is around 10-20% compared to the direct method, which requires multiple access policy checks with deployed network artifacts. The read latency is around four hundred times, which seems a significant performance issue. The side-by-side architecture includes two additional components: interoperation and relay, which add extra processing delays to the transaction processing. Both components do not interact with distributed ledger and serve only functional roles. Therefore, their impact on performance is recognized, but does not introduce significant delays. It is clear that direct integration results in significantly better performance compared to a side-by-side architecture. The increased number of layers in the side-by-side approach, especially within Hyperledger Fabric, requires an approval process to ensure secure transaction processing. Notably, for read operations, a performance gap of over four hundred times was observed between direct integration and side-by-side architecture. The extra layers introduced by side-by-side seem to be the main reason for these substantial differences. A deeper performance tests need to be carried out on a distributed and complex architecture with multiple servers and nodes to be able to make a stronger conclusion.

5.3. Implications for Supply Chain Adoption

The comparative evaluation highlights that blockchain interoperability frameworks must be assessed not only on performance but also on their capacity to preserve decentralization, enforce governance autonomy, and guarantee auditable security. For global supply chains, these attributes are more decisive than raw transaction throughput.

In practice, the findings suggest that Interside is well-suited to sectors where multiple stakeholders operate under independent governance but require trusted, cross-border data exchange. For example, in trade finance, Interside allows banks and customs authorities to validate shipment data without relying on a centralized hub. In provenance and traceability, logistics providers, manufacturers, and regulators can share signed proofs of product origin while retaining control over their local ledgers. In telecom supply chains, where equipment vendors, network operators, and regulators must collaborate across jurisdictions, Interside’s policy-aware interoperability ensures that sensitive infrastructure data is shared selectively and verifiably.

These implications underline the importance of side-by-side interoperability as a pathway to industry adoption, distinguishing Interside from failed consortium models such as we.trade, which struggled with centralization, limited scalability, and adoption barriers.

5.4. Limitations of the Study

While the evaluation demonstrates promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the comparative assessment was conducted in Hyperledger Fabric testbed environments, which may not fully reflect the scalability challenges of global-scale deployments. Second, the analysis was restricted to two baseline interoperability approaches (Direct and Cactus); including Layer-0 frameworks such as Cosmos IBC, Polkadot XCMP, or LayerZero would provide a broader comparative perspective. Third, performance evaluation was limited to simulated supply chain scenarios; real-world case studies with industry partners would strengthen the generalizability of the findings. Finally, although Interside emphasizes auditability and policy enforcement, the framework’s usability and governance processes in large consortia remain to be tested in practice.

5.5. Future Research Directions

Building on these limitations, several avenues for future research are identified. One promising direction is the

integration of Interside with Layer-0 interoperability protocols (e.g., Cosmos, Polkadot, Avalanche [

56], LayerZero) to explore hybrid approaches that combine side-by-side autonomy with high-throughput messaging protocols. Another area is the

performance optimization of interoperability flows, particularly in high-volume supply chain networks, such as those in telecom or cross-border trade, where latency and throughput remain critical. Furthermore, research should investigate

legal and regulatory alignment, assessing how frameworks like Interside can comply with emerging digital trade standards and data sovereignty laws. Finally, extending the evaluation to

multi-domain ecosystems such as telecom, energy, and healthcare will demonstrate the generalizability of the side-by-side approach beyond supply chains.

Together, the results, validation, and implications emphasize that interoperability in permissioned blockchains cannot be reduced to technical performance alone. By prioritizing decentralization, governance autonomy, and auditability, the Interside framework responds to the shortcomings of prior models and provides a viable pathway for enterprise adoption. Future work will expand its scalability, cross-domain applicability, and regulatory compliance, ensuring its readiness for production-grade deployment in global supply chain ecosystems.

5.2. Contribution to the Research Space

This study makes the following contributions to research on blockchain interoperability in supply chains:

Problem Identification: Provides a systematic analysis of existing interoperability approaches (direct, hub-based, middleware) and highlights their limitations in permissioned blockchain supply chains, particularly regarding decentralization, governance autonomy, and scalability.

Framework Design: Introduces Interside, a novel side-by-side interoperability framework that enables secure and auditable cross-chain communication while preserving the autonomy and governance of each blockchain network.

Technical Implementation: Demonstrates the feasibility of Interside through conceptual modeling and prototyping in Hyperledger Fabric, defining explicit smart contract roles, data models, and transaction flows for interoperability.

Comparative Evaluation: Benchmarks Interside against direct integration and Hyperledger Cactus across twelve criteria, showing superior performance in decentralization, governance, security, and auditability, with acceptable trade-offs in transaction throughput

Practical Implications: Provides actionable insights for adopting interoperability in real-world supply chains, including logistics, trade finance, and telecom.

6. Conclusions

Global supply chains are increasingly dependent on blockchain technologies to improve transparency, provenance, and trust within distributed ecosystems. However, as emphasized in this study, the lack of effective interoperability among permissioned blockchains compromises these objectives by maintaining data silos, causing governance conflicts, and reducing operational efficiency. Existing interoperability strategies whether through direct point-to-point connections, hub-based coordination, or middleware solutions—offer limited effectiveness and often entail trade-offs related to scalability, decentralization, and trustworthiness. To mitigate these limitations, this study presents Interside, a decentralized interoperability framework tailored explicitly for permissioned blockchains. Distinct from hub-based or direct models, Interside maintains governance autonomy while facilitating secure, auditable, and policy-compliant cross-chain communication. The framework was developed employing a design science methodology and empirically validated through comparative analysis against representative models such as direct bridges and Hyperledger Cactus. The findings substantiate that Interside provides a high degree of decentralization, governance autonomy, and security assurances, coupled with auditability and production readiness that align with supply-chain operational requirements. Although its performance is comparatively lower than that observed in direct integration approaches, it remains within acceptable thresholds for enterprise application contexts, thereby corroborating the research hypotheses (H1–H3). These outcomes emphasize the overarching principle that, within regulated multi-stakeholder environments, governance and trust considerations predominate over raw throughput metrics. Practically, the adoption of frameworks such as Interside has significant implications for logistics coordination, trade finance, telecommunications, and regulatory compliance, where autonomous actors must interoperate without compromising control or exposing sensitive data. This study advances the current state of research on blockchain interoperability by demonstrating a viable, scalable alternative to centralized or consortium-bound models. Future research should focus on extending this work by integrating Interside with emerging Layer-0 protocols, optimizing performance for high-volume deployment scenarios, and validating adoption through industry pilot programs. Addressing these challenges may position Interside as a fundamental component of next-generation blockchain-enabled supply chain systems, thereby enhancing operational efficiency and systemic resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.; methodology, S.B. and S.G.; software, S.B.; validation, S.B; formal analysis, S.B. and S.G.; investigation, S.B.; resources, S.B and S.G.; data curation, S.B.; writingoriginal draft preparation, S.B.; writingreview and editing, S.B. and S.G. .; visualization, S.B.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- HyperLedger (2022). “Case Study: Dubai’s Digital Silk Road modernizes trade with HyperLedger Fabric”. Available at: https://www.hyperledger.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/02/Hyperledger_CaseStudy_Avanz_Printable_022221.

- Grossman, M. (2022). Blockchain in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA): opportunities for regional integration and economic growth. Journal of International Business and Management, 5(5), 01-19.

- Hyperledger Fabric. Available online: https://www.hyperledger.org/projects/fabric (accessed on 26 October 2018).

- Polge, J., Robert, J., & Le Traon, Y. (2021). Permissioned blockchain frameworks in the industry: A comparison. Ict Express, 7(2), 229-233. [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. (2025). Blockchain Standardization in Practice: Contrasting European Union and US Approaches. Computer, 58(07), 100-108. [CrossRef]

- Hardjono, T., & Smith, N. (2021). Sok: Exploring blockchain interoperability. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2021/537. https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/537.

- Belchior, R., Vasconcelos, A., Guerreiro, S., & Correia, M. (2021). A survey on blockchain interoperability: Past, present, and future trends. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(8), 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, S., Gören, S., & Serif, T. (2025, March). Blockchain Interoperability for Future Telecoms. In Telecom (Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 20). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Minz, S. S., Mikkilineni, R., & Dewangan, S. (2023). Transformation of the Telecom Industry as a Result of Blockchain Technology in India. In Building Secure Business Models Through Blockchain Technology: Tactics, Methods, Limitations, and Performance (pp. 66-87). IGI Global.

- Raval, S. Decentralized Applications: Harnessing ’s Blockchain Technology; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2016.

- Ren, K.; Ho, N.-M.; Loghin, D.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Ooi, B.C.; Ta, Q.-T.; Zhu, F. Interoperability in Blockchain: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 12750–12769. [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, G. A., & İleri, O. (2025). A Comparative Analysis of Blockchain-Smart Contracts-ERP Integration Strategies for Supply Network (SN) Collaboration. IEEE Access.

- Al-Rakhami, M., & Al-Mashari, M. (2022). Interoperability approaches of blockchain technology for supply chain systems. Business process management journal, 28(5/6), 1251-1276. [CrossRef]

- Ren K, Ho NM, Loghin D, Nguyen TT, Ooi BC, Ta QT, Zhu F. Interoperability in blockchain: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2023 May 11;35(12):12750-69. [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, A. G., & Glavas, E. (2025). The New CAP Theorem on Blockchain Consensus Systems. Future Internet, 17(4), 157. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, E. (2010, July). A certain freedom: thoughts on the CAP theorem. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGACT-SIGOPS symposium on Principles of distributed computing (pp. 335-335).

- Nakamoto S. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. 2008. [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://assets.pubpub.org/d8wct41f/31611263538139.pdf.

- Sriman B, Ganesh Kumar S, Shamili P. Blockchain technology: Consensus protocol proof of work and proof of stake. In Intelligent Computing and Applications: Proceedings of ICICA 2019 2020 Sep 30 (pp. 395-406). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Turing, A. (2004). Intelligent machinery (1948). B. Jack Copeland, 395.

- Buterin V. A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. White paper. 2014;3(37):2–1.

- Baset SA, Desrosiers L, Gaur N, Novotny P, O’Dowd A, Ramakrishna V. Hands-on blockchain with Hyperledger: building decentralized applications with Hyperledger Fabric and composer. Packt Publishing Ltd.; 2018 Jun 21.

- Buterin, V. Ethereum white paper. GitHub Repos. 2013, 1, 22–23.

- R3 Corda. Available online: https://r3.com/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Ezzat, S.K.; Saleh, Y.N.M.; Abdel-Hamid, A.A. Blockchain oracles: State-of-the-art and research directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 67551–67572. [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, P., Li, D., & Gebraeel, N. (2021). Blockchain-based decentralized replay attack detection for large-scale power systems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, 52(8), 4727-4739. [CrossRef]

- Putz, B., & Pernul, G. (2020, November). Detecting blockchain security threats. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain) (pp. 313-320). IEEE.

- Kumar, A., Sah, B. K., Mehrotra, T., & Rajput, G. K. (2023, April). A review on double spending problem in blockchain. In 2023 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Sustainable Engineering Solutions (CISES) (pp. 881-889). IEEE.

- Kumar, A., Sah, B. K., Mehrotra, T., & Rajput, G. K. (2023, April). A review on double spending problem in blockchain. In 2023 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Sustainable Engineering Solutions (CISES) (pp. 881-889). IEEE.

- Cosmos. Cosmos Network; [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://cosmos.

- Cosmos. Cosmos whitepaper. Cosmos Network; [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://wikibitimg.fx994.com/attach/2020/12/16623142020/WBE16623142020_55300.

- Cosmos IBC Protocol. Cosmos Network; [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://github.com/cosmos/ibc/raw/old/papers/2020-05/build/paper.

- Wood, G. Polkadot: Vision for a heterogeneous multi-chain framework. White Pap. 2016, 21, 4662.

- Montgomery, H.; Borne-Pons, H.; Hamilton, J.; Bowman, M.; Somogyvari, P.; Fujimoto, S.; Belchior, R. Hyperledger Cactus Whitepaper. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/hyperledger/cactus/blob/main/whitepaper/whitepaper.md (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Verdian, G.; Tasca, P.; Paterson, C.; Mondelli, G. Quant overledger whitepaper. Release V0 2018, 1, 31.

- Rohrer, E., & Tschorsch, F. (2021, October). Blockchain layer zero: Characterizing the bitcoin network through measurements, models, and simulations. In 2021 IEEE 46th Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN) (pp. 9-16). IEEE.

- Ahmed, W. A., & Rios, A. (2022). Digitalization of the international shipping and maritime logistics industry: a case study of TradeLens. In The digital supply chain (pp. 309-323). Elsevier.

- Jovanovic, M., Kostić, N., Sebastian, I. M., & Sedej, T. (2022). Managing a blockchain-based platform ecosystem for industry-wide adoption: The case of TradeLens. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 184, 121981. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, D. (2023). Transforming trade finance via blockchain: The We. Trade platform. In Blockchain in supply chain digital transformation (pp. 74-93). CRC Press.

- Yakovenko A. Solana: A new architecture for a high performance blockchain v0. 8.13.2018. [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://coincode-live.github.io/static/whitepaper/source001/10608577.pdf.

- 74. Foschini L, Gavagna A, Martuscelli G, Montanari R. Hyperledger fabric blockchain: Chaincode performance analysis. InICC 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC) 2020 Jun 7 (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- 75. Shalaby S, Abdellatif AA, Al-Ali A, Mohamed A, Erbad A, Guizani M. Performance evaluation of hyperledger fabric. In2020 IEEE international conference on informatics, IoT, and enabling technologies (ICIoT) 2020 Feb 2 (pp. 608-613). IEEE.

- Xu, M., Guo, Y., Liu, C., Hu, Q., Yu, D., Xiong, Z., ... & Cheng, X. (2024). Exploring blockchain technology through a modular lens: A survey. ACM computing surveys, 56(9), 1-39. [CrossRef]

- Weaver https://hyperledger-cacti.github.io/cacti/weaver/introduction/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Said HE, Al Barghuthi NB, Badi SM, Hashim F, Girija S. Developing a Decentralized Blockchain Framework with Hyperledger and NFTs for Secure and Transparent Patient Health Records. InThe International Conference on Innovations in Computing Research 2024 Aug 1 (pp. 478-489). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Hyperledger Fabric SDKs. Hyperledger Foundation; [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/en/release-2.2/fabric-sdks.html.

- Wang G, Wang Q, Chen S. Exploring blockchains interoperability: A systematic survey. ACM Computing Surveys. 2023 Jul 13;55(13s):1-38. [CrossRef]

- Bodo B, De Filippi P. Trust in context: the impact of regulation on blockchain and DeFi. Regulation & Governance. 2024 Oct 6.

- Zala K, Modi V, Giri D, Acharya B, Mallik S, Qin H. Unlocking blockchain interconnectivity: Smart contract-driven cross-chain communication. IEEE Access. 2023 Jul 18;11:75365-80. [CrossRef]

- Kareem Y, Djenouri D, Ghadafi E. A Survey on Emerging Blockchain Technology Platforms for Securing the Internet of Things. Future Internet. 2024 Aug 8;16(8):285. [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar S, Karforma S, Bose R, Roy S, Djebali S, Bhattacharyya D. Enhancing identity and access management using hyperledger fabric and oauth 2.0: A block-chain-based approach for security and scalability for healthcare industry. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems. 2024 Jan 1;4:49-67. [CrossRef]

- Kalapaaking AP, Khalil I, Yi X, Lam KY, Huang GB, Wang N. Auditable and verifiable federated learning based on blockchain-enabled decentralization. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems. 2024 Jun 14;36(1):102-15. [CrossRef]

- Can O, Dag T, Kantarcioglu M. A blockchain based hybrid architecture for auditable consent management. IEEE Access. 2024 Jul 19. [CrossRef]

- Foschini L, Gavagna A, Martuscelli G, Montanari R. Hyperledger fabric blockchain: Chaincode performance analysis. InICC 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC) 2020 Jun 7 (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Sutradhar S, Karforma S, Bose R, Roy S, Djebali S, Bhattacharyya D. Enhancing identity and access management using hyperledger fabric and oauth 2.0: A block-chain-based approach for security and scalability for healthcare industry. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems. 2024 Jan 1;4:49-67. [CrossRef]

- Gorenflo C, Lee S, Golab L, Keshav S. FastFabric: Scaling hyperledger fabric to 20 000 transactions per second. International Journal of Network Management. 2020 Sep;30(5):e2099. [CrossRef]

- Tanana, D. (2019, June). Avalanche blockchain protocol for distributed computing security. In 2019 IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom) (pp. 1-3). IEEE.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).