1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization’s definition, Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an insidious onset neurodegenerative disease [

1]. The Parkinson’s diagnosis, to date, is made clinically, based on four motor symptoms: bradykinesia, tremor at rest, rigidity, and postural and gait impairment, proposed by the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank [

2]. As well as these symptoms, the disease has non-motor symptoms, with the most common being depression and anxiety, which have a prevalence of 22% and 25-40% respectively. Other non-motor symptoms include gastrointestinal problems such as constipation, decreased sphincter control, sleep disturbances, hyposmia, fatigue, and symptoms related to autonomic dysfunction such as orthostatic hypotension. The presence of these symptoms can cause a decrease in independence in PD patients [

3].

PD is caused by the degeneration of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons, and motor symptoms begin to become evident when between 60-80% of the dopaminergic neurons in the area compacta of the substantia nigra of the midbrain are lost. This loss affects motor, associative, learning, and emotional regions of de basal ganglia, and is reflected in increased prevalence of astrocytes and microglia in these areas [

4].

Gait impairment occurs at all stages of PD and is one of the disease’s most disabling symptoms. Generally, stride length begins decreasing from very early on, and locomotion becomes asymmetrical and begins to slow down. These symptoms tend to be unilateral at first, but become bilateral at moderate stages of the disease, when bradykinesia, freezing of the gait, loss of automaticity, festination and shuffling can also be observed. These symptoms worsen and become less responsive to pharmacological treatment as PD progresses, which leads to an increased risk of patients falling and eventually leading them to require the assistance of a wheelchair or walker [

5,

6]. Kearney (2013) reported that PD-related decreases in gait speed are associated with poorer performance in the maze test, and this with future falls [

7].

In dealing with PD, rehabilitation has been considered a coadjuvant to pharmacological and surgical treatments that can maximize functional abilities, improve quality of life, and minimize complications. Non-conventional strategies including music and dance have been proven to improve postural control and fall risk, as well as interventions that favor social integration [

8]. Exercise-based videogames are a safe, fun, and challenging option for PD patients. These exer-games promote body movement and have become one of the best tools for neurorehabilitation [

9]. This is because patients can perform complex tasks (fast, long movements involving the entire body), and the games stimulate multidirectional movements, weight transfers, a high degree of control, a high number of repetitions, attention, planning, decision making, sustained concentration, reward, motivation and commitment to the task performed [

10].

Dance in conjunction with VR has given positive results in terms of balance, performance of daily activities and decreasing risk of depression, since it provides visual and auditory feedback, and increases active learning, motivation and independence in patients [

11]. Dual tasks have been shown to increase speed when coupled with simple cognitive tasks; so dual motor and cognitive tasks provide cognitive benefits in people with EP and healthy adults [

12]. Therefore, as part of the present work, a neurorehabilitation program using a virtual reality-enhanced dance-based Xbox 360 Kinect video game was created, and its motor effects on PD patients was studied, as well as any effects on gait speed, motor performance and risk of falls.

2. Materials and Methods

Sample

An 8-week pre-experimental study with a simple pre-post design was carried out using a single group that was collected by convenience sampling. Included in the study were 14 patients with the symptoms identified by the Parkinson’s UK Brain Bank and between stages 1 and 4 on the Hoehn and Yahr scale. No patients had been diagnosed with dementia or were suffering alteration of their postural reflexes, and all were able to walk either independently or with help and stand without support for at least 1 minute. To be included in the study, patients had to accept certain standards related to regular attendance and active participation and signed informed consent documents. The patients were evening shift outpatients of the INNNMVS’s Abnormal Movements Clinic in Mexico City. The study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the INNNMVS’s Research and Bioethics Committee. All PD patients were assessed one week before and one week after the neurorehabilitation program by a neurologist (UR), a neuropsychologist (MCH) and a neurological physiotherapist (DD).

Procedure

The treatment was applied over 16 sessions (twice per week over eight weeks) in private sessions in which a single patient was placed in front of the Kinect monitor. The structure of each session was as follows: 1) a warm-up adapted to the patients individual capacity; 2) coordination exercises; which were chosen based on the steps that were observed to be the most difficult for them; 3) a dance intervention of 10 songs with breaks if the patient requested them, 4) stretches, which included the neck (flexion, lateralization, turns), pectorals, latissimus dorsi, hamstrings and gastrocnemius, and with each stretch lasting 30 seconds.

Video game description: Used in the study were a virtual reality program and an XBOX Kinect 360-based video game called Dance Central 3®, developed by Harmonix Music Systems, and released in 2012. The game is based on following a sequence of dance steps, with the user mirroring the on-screen avatar’s sequences. The game has a total of 46 songs, of which 20 from between the 1970s and 2000, all in English, were chosen. Songs were selected based on the researchers’ belief that patients would identify them and that this would improve patient adherence. The skill level of each song was established by the video game.

Scores and stars: The game is based on the correct execution of a sequence of dance steps at a speed that ranges from moderately slow to very fast. The game provides a score and a few stars (maximum 5) at the end of each song. The score is directly related to the number of stars obtained, with a higher score resulting in the participant receiving more stars at the end of the song. The top score available increases as the steps become more precise.

Levels of ability: The game has four difficulty levels: 1) Beginner, 2) Easy, 3) Medium and 4) Hard, and each song has a skill level from 1 to 8, with a higher skill level meaning more complex steps. Individual users advanced through the levels of ability when they reached 3 or more stars in 5 or more songs. (This progression was set by the researcher.)

Songs: All the songs were danced in “acting mode” because this is a single-player mode in which individual participants must mirror the steps of the dance as they are made by the on-screen avatar. Two rounds of 10 songs each with a duration of 1 minute and, 30 seconds each were programmed. In the first round, the skill levels of the songs ranged from 1 to 5, and songs were arranged in order of increasing difficulty. In the second round, skill levels were between 3 and 7, and again the order of songs was set according to their difficulty.

Instruments and Materials

The Timed Up and Go test (TUG): This test is used to measure risk of falls. It is a measure of physical performance that evaluates the ability to stand up from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn around, walk towards the chair, and sit down again, measuring the time in which the activity is performed. A participant’s walking speed is assumed normal if the time is ≤ 10 seconds, but if they take between 11-20 seconds or ≥ 20 seconds, they are deemed to be at a slight risk of falls and a high risk of falls respectively. The test has a reliability index of ICC=0.99 and validity ICC=0.99 [

13,

14].

Tinetti Scale: The Tinetti Scale is used to measure the risk of falls by evaluating the patient’s mobility in two areas: gait and balance. It’s composed of nine balance items and seven gait items. Responses are scored 0 if the patient does not achieve or maintain stability in position changes or has an abnormal gait pattern. A rating of 1 means that the patient achieves changes in position and gait patterns but has postural compensations. Finally, a rating of 2 is given to those who don’t have any difficulties performing the tasks, and whose response is considered normal. Depending on the total score, the risk of falls is determined: >24 points =

minimum, 19-24 points =

risk of falls and <19 points =

high risk of falls [

15]. In PD patients, the test Tinetti has been found to have a sensitivity of around 76% and a validity of 66% [

16]

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Scale, (UPDRS-III) motor part: This measurement is used to evaluate the motor symptoms of PD and includes assessment of spoken language, facial expressions, action and rest tremors, rigidity, hand movements, pronation-supination, leg movements, agility, getting up from a chair, posture, gait, postural stability and bradykinesia. All items have 5 response options: 0 = normal, 1 = mild, 2 = mild-moderate, 3 = moderate, and 4 = severe. The best possible score that indicates that the person is “normal” is 0, the worst possible score to obtain is 56 points, which indicates severe symptoms [

17,

18].

In the UPDRS-III motor part [

19] motor items are grouped creating subgroups of index:

- Axial index: language, getting up from a chair, gait, posture, retropulsion test (postural stability).

- Bradykinesia index: facial expressions, index finger-thumb tapping, hand opening, pronosupination, lower limb agility, bradykinesia.

- Stiffness index: stiffness (neck, upper limbs (MMSS), lower limbs (MMII)).

- Tremor index: rest tremors (MMII, MMSS) and action tremors (MMSS).

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): This is a cognitive screening test. It is made up of eight areas in which orientation and attention, visuospatial skills/ memory, language, abstraction, and executive function are assessed. The maximum score is 30 and the cut-off point for mild cognitive impairment and dementia are 25/ 26 and 17/ 18 respectively. The sensitivity of this test in the Mexican population has been shown as 98% and the specificity as 93% [

20]

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): This is a screening test to rule out depression. It consists of 9 items that assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. According to the scores, the following classification is obtained: a) Major depressive syndrome - those who present 5 or more of the 9 symptoms for more than half the week, b) Negative depressive symptoms - those who do not present the symptoms necessary for diagnosis “more than half the days” in any given period [

21].

The two screening tests were used as a filter for the inclusion of patients in the program.

To record scores obtained in the VR program (scores and stars), a form organized by song section and session number was created, as well as a register of the current level of ability of each participant. At the end of each session, the stars earned in each song were counted, and if 3 or more stars out of 5 were obtained in 5 or more songs, the level of ability was increased in the following session.

Statistical Analysis

For data analysis, version 20 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Statistics) software suite was used. Central tendency and dispersion measures were obtained for numerical data, as well as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

Pretest and posttest data was compared. The distribution of scores was analyzed for each of the outcome variables studied (using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests), as well as the presence of univariate and multivariate atypical cases (through the analysis of patients’ standardized scores in each of the outcome variables and Mahalanobis distance analysis respectively).

For differences between demographic variables, the ANOVA test was used. Student’s t-test was used for the mean difference in continuous variables. In categorical variables, the Chi Square was used, if any had less than 5% response, Fisher’s exact test was used. To verify compliance with the equality of variances between the pretest and posttest, the Levenne test was used.

To evaluate the effect of the experiment, the Student’s t-test was used for groups related to normal distribution. In cases with abnormal distribution, the non-parametric Wilcoxon Z test was used, including probability values. A 95% confidence interval and Cohen’s effect size (Cohen, J. 1992) were used. The cutoff points proposed by Cohen were used: values from 0 to 0.2 for small effect size, values close to 0.5 for medium size, and values close to 0.8 for large effect size [

22].

3. Results

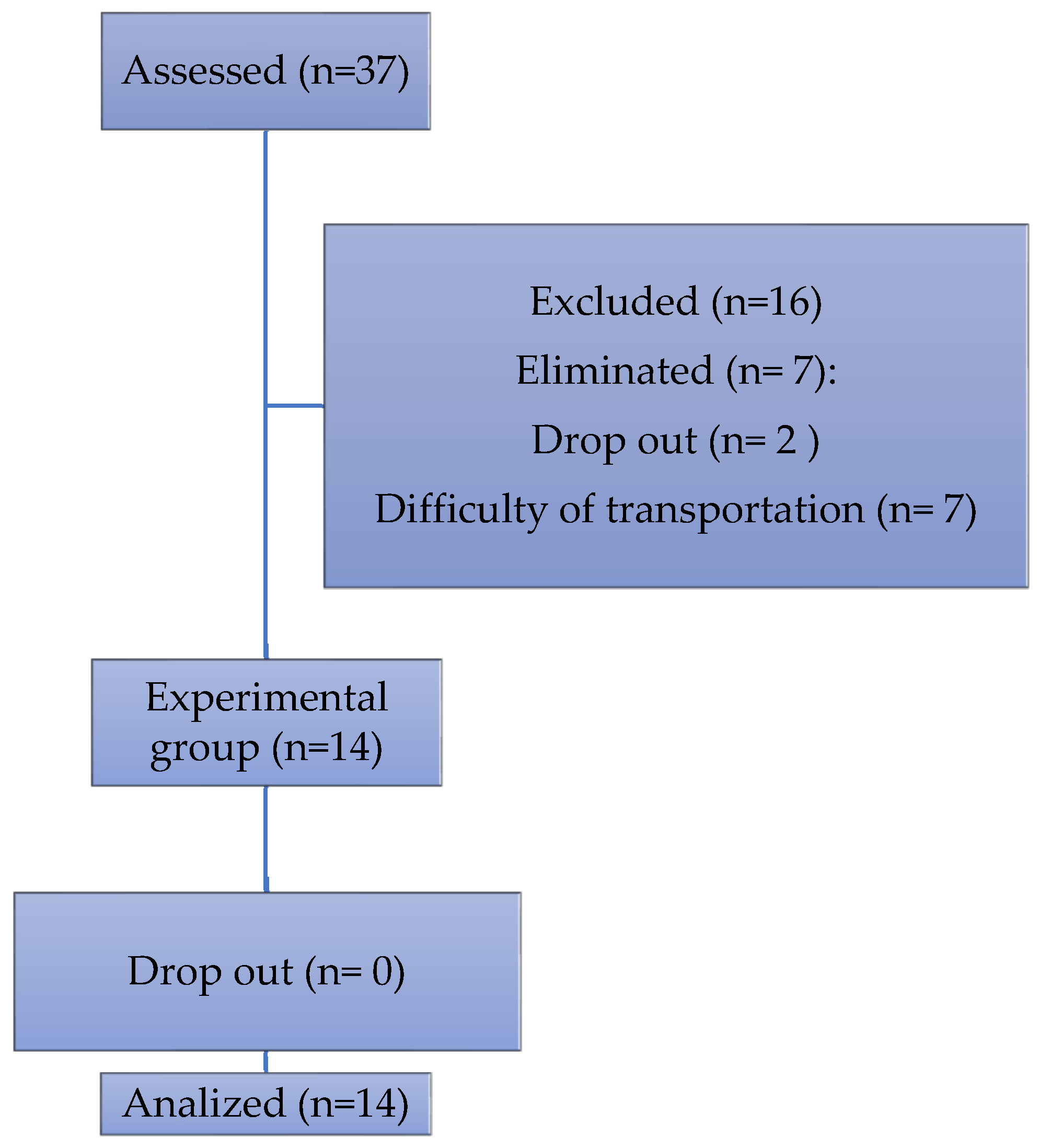

30 patients were invited to participate, of which 14 completed the program (

Figure 1).

The characteristics of the sample group and its clinical data are shown in

Table 1.

Sessions

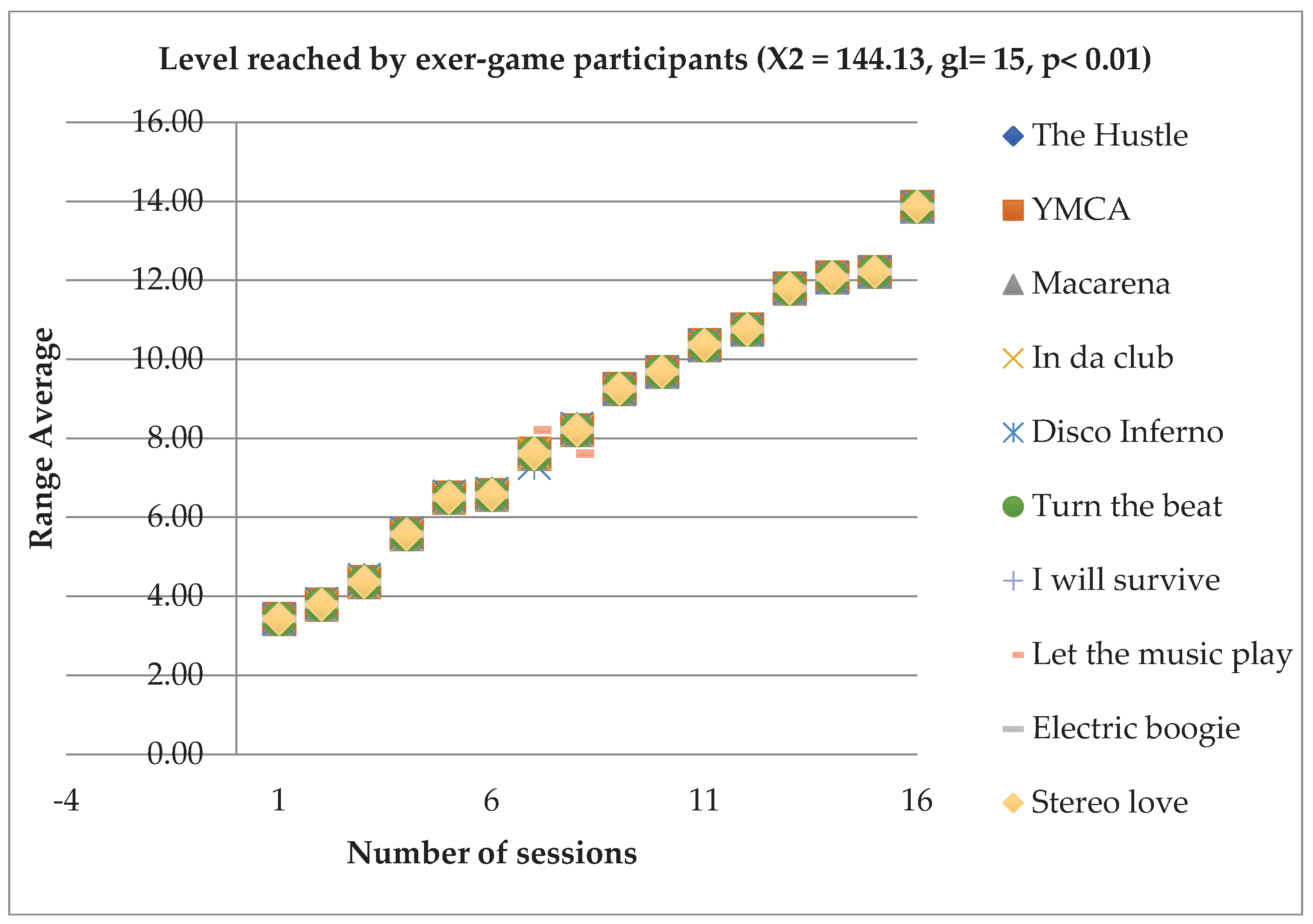

In relation to the level of dance difficulty reached by the patients, an effect of the intervention was observed (X2 = 144.13, gl= 15, p< 0.001). Improvement was seen in all 10 songs and followed a similar learning pattern. However, of the 14 participants only 2 managed to reach the maximum level of ability and 3 managed to reach section 2 of songs with high skill levels, taking them to the penultimate level of ability. All patients managed to advance at least one level of ability throughout the 16 sessions (

Figure 2).

In skill (score obtained or stars reached in each session), only the song “In Da Club” had significant differences (X2 = 32.926, df= 15, p< 0.005).

Gait

When comparing the walking speed using the Wilcoxon test (-2.003; p=0.001), a significant difference was observed between the initial time of the test (13.14 ± 5.3) and the final time (11.21 ± 2.86), indicating an improvement and increase in speed when standing up from a chair, walking 3 meters away, returning and sitting down again (

Table 2).

Regarding the classification of mobility and independence, in the initial evaluation, subjects were categorized into three groups: 2 (14.3%) with independent mobility, 10 (71.4%) mostly independent and 2 (14.3%) with variable mobility. In the post-intervention assessment, it was observed that 5 patients from the mostly independent mobility group moved to independent mobility and 2 patients who were in the group with more variable mobility moved to the mostly independent group.

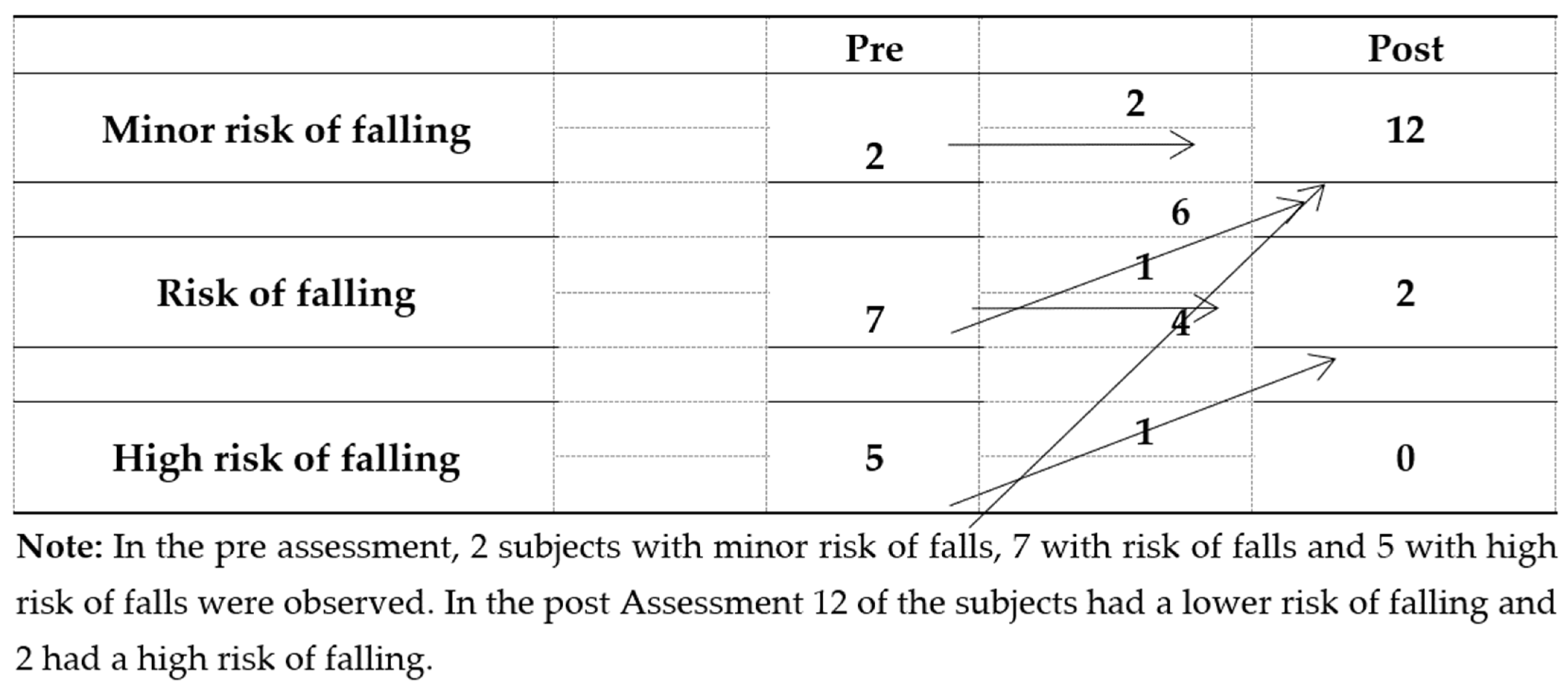

Risk of falls, gait and balance were assessed with the Tinetti scale. The total test score changed from 19.64±4.63 to 26.78±1.89, representing a decreased risk of falls. After treatment 85.7% (12) of the participants had minimal risk of falls, 14.3% (2) had some risk of falling and none were at high risk of falling (

Figure 3).

Similarly, on the UPDRS-III scale, significant differences were found in the final total score, with 85.7% of patients showing a better score post intervention. Significant differences were also shown in the scores of the indices: axial, bradykinesia, rigidity and in the total score of the indices. This means that after the intervention, patients presented improvement in the axial index (voice, getting up from a chair, gait, posture, postural stability), bradykinesia (facial expression, the index-thumb test, opening and closing of the hands, prono-supination, leg lifting and bradykinesia).

4. Discussion

Elena et al., (2021), in his systematic review [

23], found the use of exergaming as a useful therapy for the general improvement of quality of life in PD, but unlike in the present study, she found no differences between groups in terms gait speed, possibly due to the heterogeneity of the studies and the fact that not all of them evaluated this component.

The present study supports the theory that dance as therapy as well as being a safe, accessible, and enjoyable option with good adherence, since it does not compromise patient safety, especially in advanced stages of the disease, is beneficial for improving motor performance, mobility, and balance in PD patients [

24].

In this study, the video game Dance Central was used because it is based on the precise execution of a sequence of steps, which increase in speed and complexity as the level progresses but does not reach the complexity level of steps performed by professional dancers. As Tillmann (2017) points out, the increase in the speed and complexity of the steps is demanding for users because it requires an increasing ability to execute fast movements. In PD patients, he observed improvements in movement, balance, and cognition when using samba as an intervention, with varying levels of step speed and increasing complexity [

25]. In the present study, patients were able to move up through levels of ability, proving that demanding movement patterns can improve both cognitive and motor functions.

De Natale (2016) demonstrates with an 8-week intervention based on tango and increased difficulty of steps that patient gait speed in the TUG and a 6-minute walk increases more significantly compared to after traditional therapy [

26]. An increase in the speed of movement, and a resulting improvement in gait speed was observed in PD patients in the present study, also. A decrease in UPDRS-III scores was also observed in this study and may be due to the multisensory feedback that patients received during the sessions, as well as motor speed and demand, which was related to a decrease in rigidity and bradykinesia.

Van der Kolk (2015) proposes the use of exercise video games in cases of mild-moderate PD, highlighting the importance of the video game as a motivational element when patients receive a reward for the high intensity training required [

27]. In the present case, as well as making greater demands each time, the program gave rewards for advancing through levels (stars), and other motivational stimuli were present among the patients themselves, who motivated the one dancing at the time and congratulated them if they passed a level of ability.

The reduction in limb rigidity (curiously contralateral) may be related to the continuous use of the cross-pattern process, which was found in most of the steps of each song, in addition to constant hand-leg coordination. This result is similar to that reported by Cikajlo et al., (2018) [

28].

Also, in the Tinetti test, a decrease in the risk of falls was observed both in the gait and balance subscales and in the total score. Fu et al. (2015) reported the same finding in their study of 30 healthy older adults using the Kinect Wii board as a rehabilitation tool, proving that training programs based on dance and VR have a negative impact on the risk of falls [

29]

Finally, another benefit of this type of therapy is adherence to rehabilitation programs both at six months [

30] and one year after the first round of treatment [

31]. Although adherence to treatment was not evaluated in the present study, at the end of the intervention, patients requested to continue with the workshop, emphasizing that they had never participated in this type of training before. They reported feelings of recovery and achievements in various skills they had previously given up on, such as performing a turn, a movement many participants indicated they had lost several years ago. Some patients reported that they practiced dancing at home even without the Kinect, helping their motor learning and demonstrating their adherence to the intervention.

5. Conclusions

Virtual reality with dance is an effective potential alternative therapy. It is a safe, low-cost, and interactive option that increased walking speed, reduced the severity of motor symptoms such as neck stiffness, limb stiffness and bradykinesia, improved postural stability in motor performance, and decreased the risk of falls in a group of PD patients. Two sessions of 45 minutes each for 8 weeks was sufficient to observe benefits. In addition to this, despite initial skepticism on the part of doctors about the ability of participants to advance through the levels of ability and handle the increase in complexity, patients were indeed able to advance and improve, with some of them reaching the highest levels of the game, demonstrating their motor learning and the improvement of their reaction times and coordination.

It can be concluded that the therapy used in this study can treat symptoms of PD that are difficult to control and become especially complicated over time as the efficacy of pharmacological treatment decreases. At this time, symptoms can worsen further and incapacitate most PD patients, severely affecting their quality of life and independence. In the same way, this study is a call to continue the use of innovative new technologies and dance in older patients, since it is convenient to find options that encourage patients to carry out their activities independently.

Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Further Research

We consider that the most important limitations of the present study are the small sample size and the absence of a control group that would allow the observed effect to be attributed to the intervention, although we believe that the result is an indeed a result of the intervention. Unfortunately, the baseline and post-intervention tests were performed in a short period of time (three months). It is recommended that future researchers increase the number of evaluations of the program’s effects to at least three in one year, in order to determine if its benefits are maintained in the long term.

This work did not evaluate fear of falls and adherence to treatment, and it would be convenient to include these variables in future research. Also, a good idea would be to offer this type of planned programs aimed at PD patients in rehabilitation institutes and clinics where family members and patients receive training on the disease, and patients are encouraged to exercise without this preventing them from performing their daily activities, to improve motivation among this population.

Something observed at the end of the research period and that may have been decisive for the achievement of its objectives is that, in the waiting room before starting individual interventions, a group that allowed the socialization and integration of patients and their relatives was formed. This was referred to by patients in an informal way at the end of the intervention, with the majority commenting that this socialization had been important to better performance and increased motivation and improved their perceived quality of life. Therefore, a suggestion is to include the study of psychosocial aspects in interventions like this one in the future.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.D. and M.CH.; Methodology, D.D. and U.R.; Software, D.D.; Formal analysis, F.P.; Data curation, F.P. and D.D; Writing—original draft preparation, D.D. and F.P; Writing—review and editing, M.CH. U.R. and D.D.

Funding

This research has not received the specific economic support of public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit entities

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery (MVS, México), grant number 13/18. Date approved 2/01/2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to participation in any study procedures.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the 414 corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their time and effort.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD |

Parkinson Disease |

| RV |

Virtual reality |

| UPDRS-III |

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Scale |

| TUG |

Timed up & go Test |

References

- WHO. Neurological disorders: Public health challenges. World Helath Organization. 2006.

- Kasten, M.; Chade, A.; Tanner, C. M. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2007, 83, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, R. F. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Related Disord. 2016, 22, S119–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zesiewicz, T.A. Parkinson Disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019, 25, 896–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirelman, A.; Bonato, P.; Camicioli, R.; Ellis, T. D.; Giladi, N.; Hamilton, J. L.; Hass, C. J.; Hausdorff, J. M.; Pelonsin, E.; Almeida Q, J. Gait impairments in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso Suárez, T.; Álvarez González, C. R.; Díaz de la Fe, A.; Méndez Alonso, C. M.; Sabater Hernández, H.; Álvarez González, L.M. Gait disorders in Parkinson disease : clinical , physiopathologic and therapeutical features. [Trastornos de la marcha en la Enfermedad de Parkinson : aspectos clínicos , fisiopatológicos y terapéuticos]. RCMFR. 2017, 1, 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, F. C.; Harwood, R. H.; Gladman, J. R. F.; Lincoln, N.; Masud, T. The relationship between executive function and falls and gait abnormalities in older adults: A systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013, 36, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbruzzese, G.; Marchese, R.; Avanzino, L.; Pelosin, E. Rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease: Current outlook and future challenges. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016, 22, S60–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F. C.; Iop, R. D. R.; de Oliveira, L. C.; Boll, A.M.; de Alvarenga, J. G. S.; Gutierres Filho, P. J. B.; de Melo, L. M. A. B.; Xavier, A. J.; da Silva, R. Effects of physical exercise programs on cognitive function in Parkinson’s disease patients: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the last 10 years. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, M. I.; Barnes, D. E.; Ross, J. M.; Lanni, K. E.; Sigvardt, K. A.; Disbrow, E. A. A pilot study to evaluate multi-dimensional effects of dance for people with Parkinson’s disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016, 51, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.Y.; Lee, D. K.; Song, H. S. Effect of virtual reality dance exercise on the balance, activities of daily living, and depressive disorder status of Parkinson ’ s disease patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015, 27(1), 145–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazamy, A. A.; Horne, S. A.; Okun, M. S.; Hass, C. J.; Altmann, L. J. Effects of a Cycling Dual Task on Emotional Word Choice in Parkinson’s Disease. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019, 62, 1951–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla, E.; Valenzuela, J. H.; Escobar, M. Rendimiento en las pruebas “Timed up and go” y “Estación Unipodal” en adultos mayores chilenos entre 60y 89 años. Rev Med Chile 2015, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, J. R.; Stegemoller, E. L. Malaty, I. A.; Okun, M. S.; Marsiske, M.; Hass, C. J. National Parkinson Foundation Quality Improvement Initiative Investigators. Using the Timed Up & Go Test in a Clinical Setting to predict falling in Parkinson’s Disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013, 94, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega Elguézabal, J. F.; Díaz de León González, E.; Barragán Berlanga, A. J.; Méndez Lozano, D. H. A Tinetti score of 24 points or less is a factor associated with falls in geriatric patients. [La escala de Tinetti igual o menor a 24 puntos es un factor asociado a caídas en pacientes geriátricos[. Avances. 2010, 7, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kegelmeyer, D. A.; Kloos, A. D.; Thomas, K. M.; Kostyk, S. K. Reliability and Validity of the Tinetti Mobility Test for Individuals With Parkinson Disease. Phys Ther. 2007, 87, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. R.; Mason, S. L.; Williams-Gray, C. H.; Foltynie, T.; Trotter, M.; Barker, R. A. The factor structure of the UPDRS as an index of disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2011, 1, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Violante, M.; Cervantes-Arriaga, A. The Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): clinical application and research. [La escala unificada de la enfermedad de Parkinson modificada por la Sociedad de Trastornos del Movimiento (MDS-UPDRS): aplicación clínica e investigación]. Arch Neurocien (Mex) 2014, 19, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, M. S.; Hou, J. G.; Collins, R. L.; Protas, E. J. Contribution of Axial Motor Impairment to Physical Inactivity in Parkinson Disease. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016, 95(5), 348–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Navarro, S. G.; Mimenza-Alvarado, A. J.; Palacios-García, A. A.; Samudio-Cruz, A.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. A.; Ávila-Funes, J. A. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for the Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Mexico. [Validez y confiabilidad del MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) para el tamizaje del deterioro cognoscitivo en méxico]. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr (Engl Ed). 2018, 47, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrieta, J.; Aguerrebere, M.; Raviola, G.; Flores, H.; Elliott, P.; Espinosa, A.; Reyes, A.; Ortiz-Panozo, E.; Rodríguez-Gutierrez, E. G.; Mukherjee, J.; Palazuelos, D.; Franke, M. F. Validity and Utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire ( PHQ ) -2 and PHQ-9 for Screening and Diagnosis of Depression in Rural Chiapas, Mexico : A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Psychol. 2017, 73, 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, P.; Demetris, S.; Christina, M.; Marios, P. Differences Between Exergaming Rehabilitation and Conventional Physiotherapy on Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol. 2021, 12, 683385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Barbirato, D.; Araujo, N.; Martins, J.V.; Cavalcanti, J.L.; Santos Tony, M.; Coutinho, E. S.; Laks, J.; Deslandes, A. C. Comparison of strength training, aerobic training, and additional physical therapy as supplementary treatments for Parkinson’s disease: pilot study. Clin Interv Aging 2015, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, A. C.; Andrade, A.; Swarowsky, A.; Guimarães, A. C. A. Brazilian Samba Protocol for Individuals With Parkinson’s Disease: A Clinical Non-Randomized Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017, 6, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Natale, E. R.; Paulus, K. S.; Aiello, E.; Sanna, B.; Manca, A.; Sotgiu, G.; Leali, P. T.; Deriu, F. Dance therapy improves motor and cognitive functions in patients with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 40, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, N. M.; Overeem, S.; de Vries, N. M.; Kessels, R. P.; Donders, R.; Brouwer, M.; Berg, D.; Post, B.; Bloem, B. R. Design of the Park-in-Shape study: A phase II double blind randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of exercise on motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cikajlo, I.; Hukić, A.; Dolinšek, I.; Zajc, D.; Vesel, M.; Krizmanič, T.; Blažica, B.; Biasizzo, A.; Novak, F.; Peterlin Potisk, K. Can telerehabilitation games lead to functional improvement of upper extremities in individuals with Parkinson’s disease? Int J Rehabil Res. 2018, 41, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A. S.; Gao, K. L.; Tung, A. K.; Tsang, W. W.; Kwan, M. M. Effectiveness of Exergaming Training in Reducing Risk and Incidence of Falls in Frail Older Adults With a History of Falls. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2015, 96, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, E. R.; Golden, L.; Duncan, R. P.; Earhart, G. M. A community-based Argentine tango dance program is associated with increased activity participation among individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013, 94, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delextrat, A.; Bateman, J.; Esser, P.; Targen, N.; Dawes, H. The potential benefits of Zumba Gold(®) in people with mild-to-moderate Parkinson’s: Feasibility and effects of dance styles and number of sessions. Complement Ther Med. 2016, 27, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).