1. Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) or scleroderma is a complex autoimmune connective tissue disease caracterized by skin thickening and hardening, leading to fibrosis and vascular abnormalities and immune system dysfunctions. These processes can result in systemic involvement, most frequently affecting the lungs, heart and gastrointestinal system. A second form is represented by localized SSc which generally involves skin and underlying tissues, without systemic organ involvement [

1]. In our days, because SSc is a complex disease which touch multiple organs a multidisciplinary teams is mandatory. This narrative review aims to synthesize the main data from the literature on everything a clinician who comes into contact with such a complex pathology needs to know. Starting from epidemiology and passing through pathophysiology and diagnostic methods, this manuscript also brings to the fore therapeutic methods and the need for collaboration between multiple specializations for a favorable outcome on the prognosis of the patient with SSc. These patients often are hospitalized in internal medicine departments. Collaboration with the rheumatologist, dermatologist, cardiologist, gastroenterologist, family doctor and any other specialization is essential.

Autoimmune pathologies in the rheumatological field such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), SSc have been studied and found to be associated with an increased risk of developing cardiac, supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias. Clinically, these rhythm disorders are often observed and contribute to higher cardiovascular risk and also to patient mortality [

2].

2. Materials and Methods

This paper was designed as a narrative review to highlight and integrate the newest insights into the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of arrhythmias identified in patients with SSc, as well as to analyze the cardiovascular effects of immunomodulatory and biological therapies used in the treatment of this complex autoimmune disease. Literature sources were selected following a structured search in the PubMed and Google Scholar databases, using combinations of relevant terms such as: SSc, cardiac arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, conduction abnormalities, ventricular arrhythmias, myocardial fibrosis, autonomic dysfunction, microvascular ischemia, inflammation, immunosuppressive therapy, biologic agents, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac involvement in SSc. To ensure the timeliness and clinical relevance of the information presented, articles published in the last ten years (2015–2025) were prioritized. A limited number of older sources were also included, selected for their foundational role in shaping clinical guidelines and understanding cardiac involvement in SSc. A total of 115 articles were identified. After applying the exclusion criteria, 98 articles were initially retained. Subsequently, an additional 13 case reports and 10 studies primarily focused on inflammation, without demonstrating a direct causal relationship, were excluded. As a result, a total of 75 articles were ultimately selected for inclusion in this narrative review: 26 cohort studies on arrhythmias in SSc, 44 studies on cardiovascular disease in SSc, and 5 review articles (4 systematic and 1 narrative).

3. Epidemiology of Systemic Sclerosis

In patients with SSc, the prevalence of arrhythmic complications is higher compared to other autoimmune pathologies. The most common arrhythmias described are atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, in a proportion of 20-30% while ventricular arrhythmias are present in up to 67% of patients [

3]. Premature ventricular contractions are also observed, the most frequent being the monomorphic forms. They can appear isolated or less often as bigeminy, trigeminy or couplets. [

2]

Also, sudden cardiac death, a sensitive topic, has been reported in around 21% of patients with SSc, underlining the need for early diagnosis and management of cardiac complications in this group of patients [

4].

4. Pathophysiology of Arrhythmias in Rheumatology Diseases with Focus on Systemic Sclerosis

In SSc, persistent inflammation plays a central role, leading to the development and maintenance of myocardial fibrosis, which is a key factor in arrhythmogenesis. The fibrotic remodeling present in the myocardium can cause diffuse damage, impairing the integrity of the myocardial conduction function and ultimately resulting in arrhythmias [

5]. When fibrosis involves components of the conduction system as the sinoatrial node and the His-Purkinje network, bradyarrhythmias and conduction disturbances may occur [

6]. Another mechanism that sustains arrhythmic risk in SSc is autonomic nervous system dysfunction. In this group of patients, marked rhythm instability has been observed, due to a sympathetic-parasympathetic imbalance facilitates the occurence of arrhythmia [

3]. Clinically, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is a valuable method for detecting myocardial damage in patients with SSc. It is considered an important tool because it provides high-resolution assessment of myocardial fibrosis and identification of arrhythmogenic areas, thus supporting early therapeutic management in these patients [

5].

Histopathological consistently shows replacement of myocardial tissue by fibrosis, these findings has been correlated with the clinical occurence of rhythm disturbances [

7]. At the molecular level, procceses such as collagen synthesis, immune activation, structural remodeling, electrical vulnerability are driven by dysregulated pathways. These mechanisms represent potential therapeutic targets to reduce arrhythmic burden in this high-risk population [

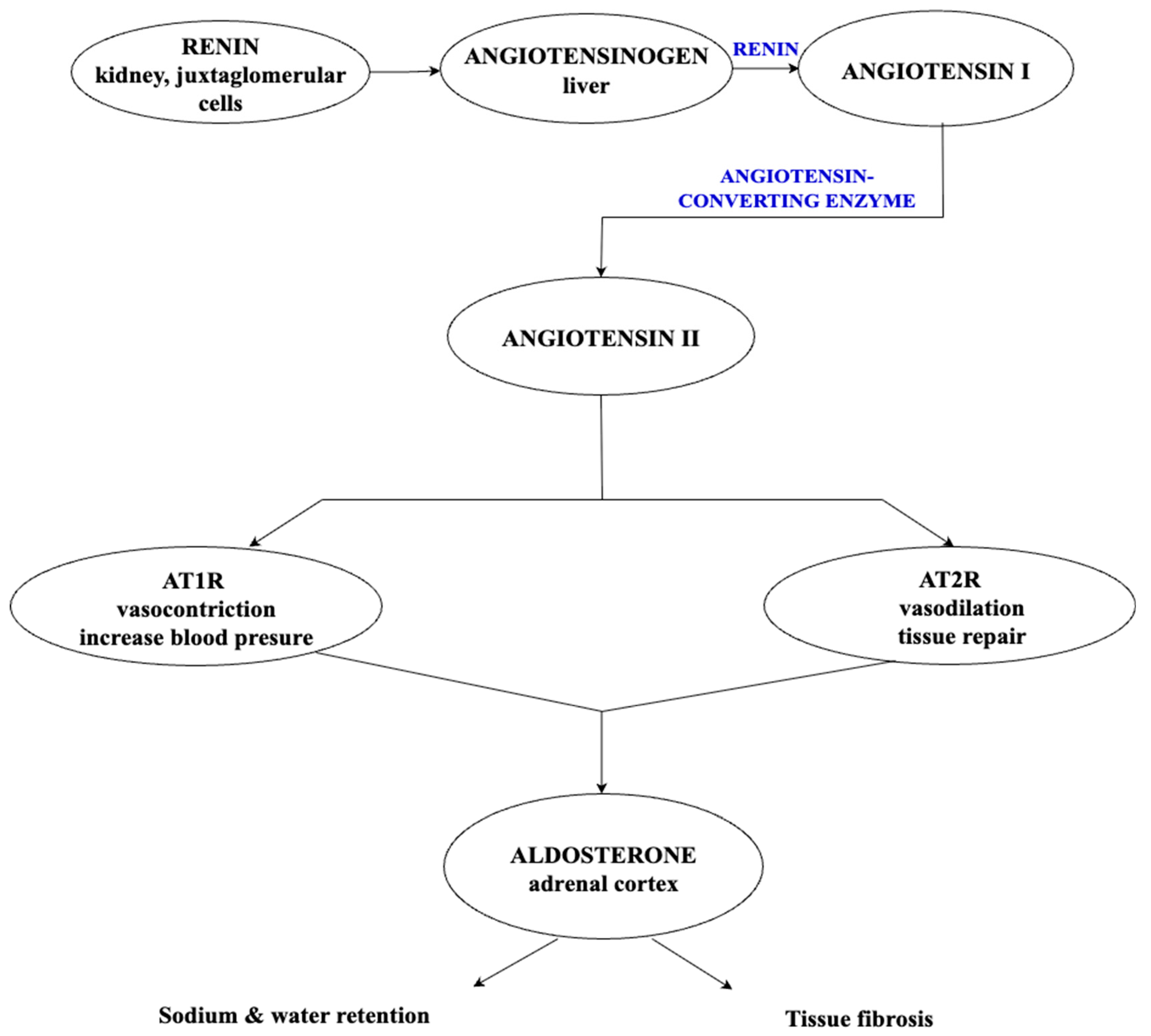

8]. Arrhythmogenicity is determined mainly by the formation of a structural substrate due to the atrial and/or ventricular fibrosis- referred to as atrial and ventricular structural remodeling. Electrical remodeling of the heart also plays a key role. The main mechanisms involved are complex, with evidence suggesting the implication of autonomic nerve system (ANS), renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), endothelial dysfunction, epicardial tissue adiposity or inflammation. The

Figure 1 illustrates the main mechanisms involved in arrhythmogenesis both in general and in SSc, in particular.

4.1. Atrial and Ventricular Remodeling and Arrythmogenicity

SSc is frequently associated with intrinsic cardiac involvement, which is related to both atrial and ventricular remodeling. The origin of these cardiac changes is multifactorial, mainly resulting from progressive myocardial fibrosis, small-vessel vasculopathy, and chronic inflammatory processes. Fibrous tissue replacement together with microvascular ischemia, leads to disruption of normal myocardial architecture and function. The consequences are diastolic dysfunction, impaired contractility, and conduction abnormalities, which may occur even in the absence of cardiovascular symptoms. Atrial remodeling, particularly, predisposes patients to arrhythmias, while ventricular changes may worsen heart failure and reduce cardiac reserve, underlining the clinical importance of early cardiac evaluation in SSc [

9].

In a study involving 74 participants, including 34 patients diagnosed with SSc and 34 healthy control subjects, two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography, an advanced cardiac imaging technique, was used. Compared with conventional echocardiography, two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography can detect subtle ventricular dysfunction that might otherwise go unnoticed [

10]. The results showed significant atrial involvement in the SSc group, with evidence of impaired interatrial conduction due to pathophysiological mechanisms specific to the disease. In addition, tissue Doppler imaging revealed higher systolic pulmonary artery pressure and increased mitral A-wave velocities, along with a lower left ventricular filling flow E/A ratio – these findings suggest early diastolic dysfunction in this patient group [

11].

Impaired right atrial function may also develop as a consequence of increased systolic pulmonary artery pressure, often accompanied by right ventricular hypertrophy. In the context of pulmonary arterial hypertension, right atrial augmentation function becomes especially important, as it plays a key role in maintaining adequate right ventricular filling. Both systolic and diastolic atrial dysfunction can increase mean atrial pressures, potentially leading to pulmonary or systemic venous hypertension [

10,

12].

4.2. Autonomic Nerve System and Arrhythmogenicity

Dysregulation of the ANS occurs frequently and often early in patients with SSc, playing a key role in the development of cardiac arrhythmias, through a sympathetic-parasympathetic imbalance, increasing the risk of sudden cardiac death. Multiple studies have shown that patients with SSc frequently present autonomic dysfunction, often reflected by decreased heart rate variability and abnormal heart rate turbulence. These changes indicate a reduced ability to maintain adequate cardiac regulation, which may precede clinical cardiac symptoms [

13].

In a study involving 45 patients with SSc and 30 healthy controls, significant abnormalities in heart rate turbulence parameters were observed in the SSc group, suggesting early autonomic involvement. Age and the presence of pulmonary hypertension were identified as independent predictors of autonomic dysfunction [

13]. Another study found a relationship between autonomic dysfunction and microvascular damage in SSc. Nailfold videocapillaroscopy demonstrated that patients with severe microvascular abnormalities are more likely to present signs of cardiac autonomic neuropathy [

14].

The sympathetic-parasympathetic imbalance observed in SSc patients plays a central role in arrhythmogenesis. Increased sympathetic drive combined with reduced parasympathetic activity creates a pro-arrhythmic state, favoring the development of various conduction and rhythm disturbance. One study also found a significant positive association between diastolic dysfunction – affecting either the left or right ventricle – and total skin score and the presence of anti-Scl-70 antibodies. In contrast, there was an inverse relationship between diastolic dysfunction and several parameters of heart rate variability, except for the low-frequency/high-frequency ratio (known as LF/HF), which was positively correlated. No significant correlation was ofound between diastolic dysfunction and the presence of anticentromere antibodies. In addition, cardiac rhythm disturbances were documented in a significant proportion of patients with SSc. In a 2010 study involving 30 patients with SSc, 33% of patients presented frequent premature ventricular contractions (≥10/hour) and 7% experienced episodes of supraventricular tachycardia, while in the control group arrhythmias were rarely detected. Moreover, the total premature ventricular contractions burden was considerably higher in patients with SSc compared to healthy controls [

15].

Beyond its direct effects on the myocardium, autonomic dysregulation in SSc impacts multiple organ systems. Among the most frequently affected are gastrointestinal mobility and thermoregulation. In a 2021 cross-sectional study involving 26 patients diagnosed with SSc, a high proportion presented with Raynaud’s phenomenon (80%) and esophageal dysmotility (43%), highlighting the significant systemic impact of autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction [

16]. These findings support the hypothesis that the appearance or exacerbation of Raynaud’s phenomen may represent one of the earliest clinical manifestations of autonomic dysfunction, particularly from a microvascular perpective. Similarly, esophageal motility disorders have been associated with cardiac autonomic neuropathy, suggesting that autonomic involvement may occur early in the disease course, preceding myocardial fibrosis or other internal organ complications [

15].

4.3. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System and Arrhythmogenicity

The renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system plays a central role in maintaining blood pressure and fluid–electrolyte balance. The kidneys represent the main sourse of prorenin, which is converted to renin and secreted by the juxtaglomerular cells in response to reduced renal perfusion, low sodium delivery to the macula densa, β₁-adrenergic stimulation. Then, renin cleaves Angiotensinogen, prodused by the liver, into Angiotensin I (Ang I) which is rapidly comverted into Angiotensin II by angiotensin-converting enzyme. The ACE is predominantly located in the pulmonary and vascular endothelium [

17,

18]. Angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstrictive peptide and exerts its effects mainly via two receptor subtypes: angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT₁R), which predominates in adults and mediates vasoconstriction by increasing intracellular calcium in vascular smooth muscle cells and angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT₂R) which mediates vasodilation and tissue repair through nitric oxide release [

19,

20]. Aldosterone, the terminal effector of the RAAS cascade, promotes sodium retention and contributes to tissue fibrosis by stimulating the synthesis of extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin and type I collagen [

20]. The renin–angiotensin system mechanism is shown in

Figure 2.

In SSc, the pathogenic role of RAAS is amplified by functional autoantibodies against AT₁R adn endothelin receptor type A. These antibodies activate endothelial cells, increasing the production of chemokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, enhancing neutrophil migration and impairing endothelial repair. They also stimulate fibroblasts to produce type I collagen, favoring fibrosis. Experimental studies have shown that transferring these autoantibodies to mice triggers lung inflammation, elevated chemokine levels and histological changes associated with systemic vascular injury [

21,

22].

The clinical evidences shows that RAAS dysregulation is relevant for cardiac manifestations in SSc. In a cohort of 110 patients, approximately 61% exhibited conduction or rhythm disturbances- from premature ventricular contractions to atrioventricular blocks and atrial arrhythmias which were frequently associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension and myocardial fibrosis. These findings support hypothesis that RAAS activation contributes to adverse myocardial remodeling, creating an arrhythmogenic substrate in SSc patients [

23].

4.4. Endothelial Dysfunction and Arrhythmogenicity

Endothelial dysfunction is key in developing large-vessel atherosclerosis. Even early on in SSc, the small blood vessels’ lining shows damage or activation due to factors like immune attacks, infections causing cell death, antibodies targeting the endothelium, and injury from blood flow changes [

24]. Higher endothelin levels—a strong vasoconstrictor made by these cells—make this problem worse. This contributes to blood vessel disease seen in SSc and speeds up atherosclerosis. As a result, patients with SSc have a higher chance of problems like peripheral artery disease, strokes, carotid artery issues, and heart disease [

25].

4.5. Epicardial Tissue Adiposity, Inflammation and Arrhythmogenicity

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) surrounds the heart and coronary vessels, acting like a protective cushion under normal conditions. It helps reduce mechanical stress on the heart and supports blood vessel remodeling. EAT also plays a role in keeping the heart warm by producing heat [

26]. Adipose tissue generally comes in two types : white and brown fat. White fat stores energy in large droplets and has few mitochondria, while brown fat has many small droplets and lots of mitochondria to help produce heat. Although EAT is mainly white fat, it shows some brown and beige fat-like features. It expresses thermogenic genes and releases various inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, interleukins, C-reative protein, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 [

27].

Clinical studies have found that in SSc, having a higher amount of EAT- over 67 grams-is linked to worse left ventricular diastolic function and higher overall mortality over an 8-year period. These findings suggest that excess EAT contributes to both structural and functional changes of the myocardium in SSc [

28]. Atrial fibrillation is the most common heart rhythm disorder seen in clinical practice and is a major cause of ischemic stroke, heart failure, and cardiovascular deaths. It develops because of complex electrophysiological and structural changes within the atria, notably myocardial fibrosis involving multiple mechanisms. Factors that promote atrial fibrillation include adipocyte infiltration, paracrine signaling with pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory effects, oxidative stress, and other interconnected pathways [

29].

4.6. Potential Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Arrhythmogenicity

In SSc the risk of developing arrhythmias is driven by a series of mechanisms involving structural, functional, and electrical abnormalities, many of which are triggered by ongoing inflammation and tissue damage. Several of these risk factors have already been discussed in the previous sections.

Table 1 brings them together for a clear overview as a reminder of their combined role leading to arrhythmogenesis.

The first feature, autonomic dysfunction, caused by an imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, can lead to abnormal rhythms and even sudden cardiac death [

15]. Myocardial fibrosis, driven by chronic inflammation and collagen buildup, makes the heart muscle stiffer, which can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy and heart failure [

30]. Also, some of medications used to treat SSc (corticosteroids, prostacyclin analogues, biologics, etc) can have cardiotoxic or arrythmogenic effects, which highlights the need to weigh their therapeutic benefits against possible cardiovascular risks [

30]. The damage of both micro and macro blood vessels-often linked to coronary artery involvement and endothelial dysfunction-can significantly reduce blood flow to the heart [

31,

32].

At the same time, chronic inflammation, kidney and digestive system involvement, along with side effects from medications, can lead to electrolytes imbalances- making the heart more vulnerable to rhythm disturbances, including torsades de pointes, ventricular tachycardia, or even cardiac arrest. Sadly, these complications are not rare-around 26% of patients with SSc lose their lives due to heart- related causes, most often because of heart failure or severe arrhythmias [

33].

4.7. Effects of Drug Used in the Treatment of Systemic Sclerosis and Cardiac Involvement

Managing SSc is a complex process that requires a complex and personalized approach. Treatment focuses on several key areas: correcting the immune dysregulation, reducing or preventing fibrosis to help preserve tissue and organ function, and improving skin symptoms through both systemic and local treatments, as well as targeting blood vessel abnormalities. Alongside the main aims, it’s also essential to prevent and manage potential complications involving the internal organs—particularly the lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys—while controlling manifestations and improving quality of life. Because SSc may have multisystemic involvement is often required a multidisciplinary team and an individualized treatment plan.

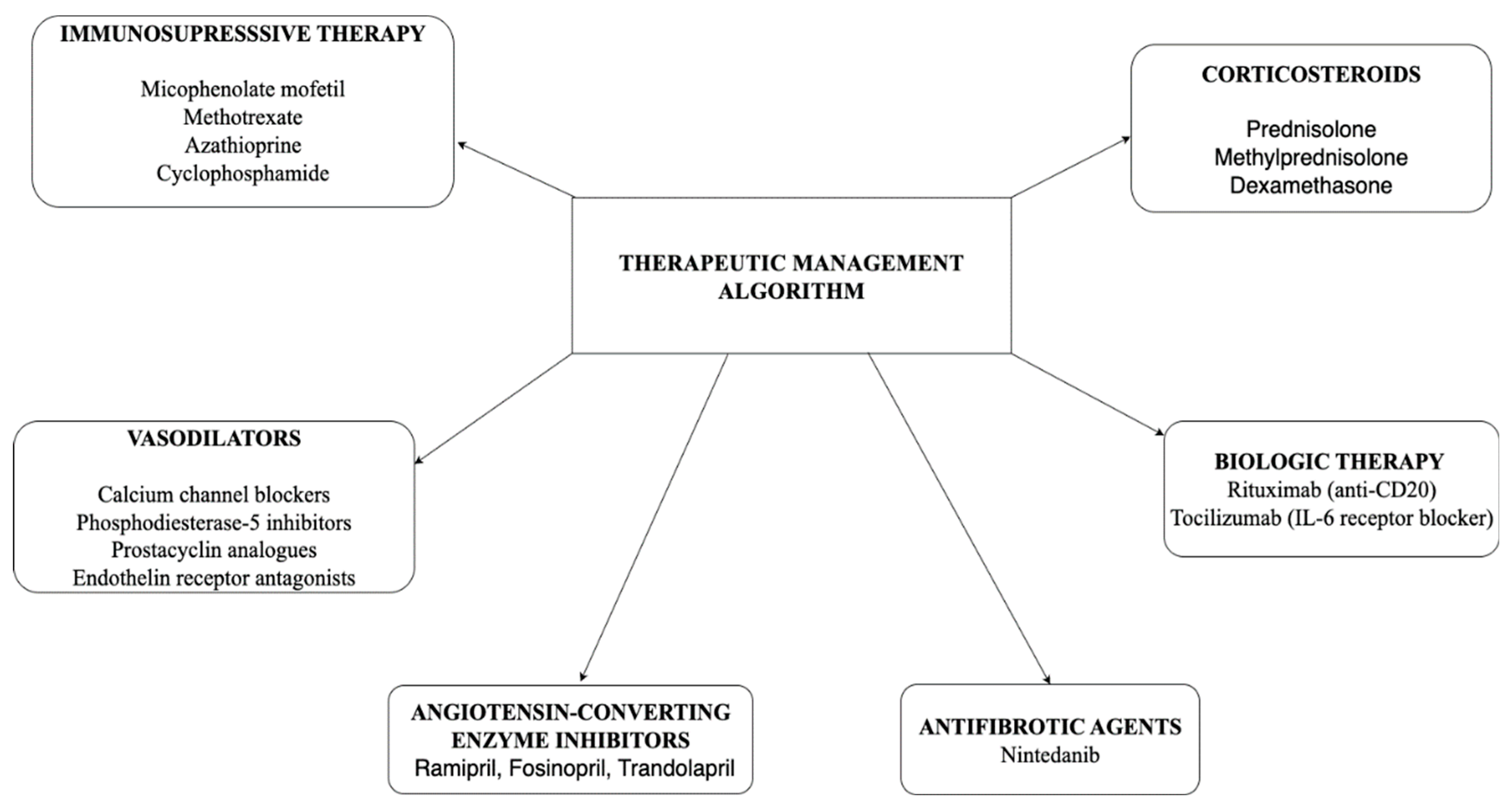

In the

Figure 3 the therapeutic management algorithm in SSc is described, illustrating therapeutic classes such as immunosuppressive medication, vasodilators, antifibrotic agents and targeted biologic therapies. The specific combination and choice of drugs depend on the type of SSc, the severity and pattern of organ involvement. These treatment options will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

4.7.1. Immunosuppresssive Medication

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is a recognized immunosuppressant used in SSc. Its mechanism of action involves inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation by blocking inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme essential for DNA synthesis in T and B cells.

It is currently considered the first-line therapeutic option, particularly in SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD), owing to its demonstrated efficacy and favorable safety profile compared to alternative immunosuppressive agents. Additionally, MMF is appreciated for its potential to stabilize or even improve cutaneous involvement [

34].

Its clinical utility in SSc-ILD has been supported by multiple studies, including a real-world study in 2017 [

35]. The study evaluated 46 patients receiving a reduced dose of 3 g/day and found that, over a 24-month treatment period, pulmonary function parameters remained relatively stable. Moreover, systolic pulmonary artery pressure (RVSP) showed no significant change, and the therapy was generally well tolerated, with minimal adverse effects. Nonetheless, potential arrhythmogenic effects of MMF have also been reported. In a case report involving a 55-year-old patient undergoing MMF therapy, Holter ECG monitoring revealed the presence of both ventricular and atrial ectopic beats, an episode of supraventricular tachycardia, as well as bundle branch blocks [

36].

Methotrexate (MTX) is an antifolate antimetabolite whose mechanism of action involves inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase, resulting in impaired DNA synthesis, as well as suppression of purine and pyrimidine production, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects. In SSc, methotrexate is primarily used in the diffuse cutaneous form, although its impact on skin thickening is generally modest [

37]. As methotrexate is considered an alternative, rather than first-line, treatment in SSc, current evidence regarding its cardiovascular safety remains limited. Nevertheless, it appears to have a favorable safety profile in many patients. However, in isolated reports—such as the case described by Sareena Shah et al. (2022)—methotrexate has been associated with cardiotoxic effects. Documented adverse events have included ventricular arrhythmias, right bundle branch block, and other idiosyncratic rhythm disturbances [

38].

In conclusion, although such cases are rare, they underscore the importance of careful cardiovascular monitoring during methotrexate therapy, as adverse effects—though infrequent—may include significant arrhythmias or, in severe cases, heart failure.

Azathioprine (AZA) is a pro-drug of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) which is converter into thioinosinic acid, leading to inhibit putine synthesis, reducing DNA and RNA production- the final result being the T and B cell supression. AZA is considered a therapeutic alternative for patients with

SSc who do not respond to, or cannot tolerate, other immunosuppressive treatments.A

literature review published in 2025, which included 10 studies, analyzed the effects of azathioprine on both

cutaneous and

pulmonary parameters. The results were generally positive, particularly in patients with

SSc-ILD and also in those who had previously received

cyclophosphamide as part of their initial treatment option [

39].

To date, the effects of

azathioprine on cardiac rhythm disturbances in patients with

SSc have not been clearly defined, as no dedicated studies have addressed this aspect. However, a case report described a 45 years old female patient which presented a severe form of SSc. She developed

low cardiac output syndrome, possibly associated with

myocarditis or a

toxic inflammatory injury to the myocardium during treatment with azathioprine. In this context, the cardiovascular complications were thought to be related to the drug’s toxicity, likely influenced by the complexity of the underlying disease [

40].

Cyclophosphamide (CYC) is an alkylating immunosuppressant that works by cross-linking DNA, leading to the death of rapidly dividing immune cells. In SSc, this mechanism helps reduce inflammation and slow the progression of fibrosis. For many years, cyclophosphamide has been a key treatment in SSc and remains the first-line therapy for SSc-ILD, according to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations. However, due to its significant toxicity compared to MM—and similar efficacy in treating both skin and lung involvement—MM is often preferred as a first-line treatment based on clinical experience and expert opinion [

41]. Although no studies have clearly demonstrated a direct link between cyclophosphamide and arrhythmias specifically in patients with SSc, some of its known general pro-arrhythmic effects include: atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia, premature ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia, and in high-dose can lead to high-grade atrioventricular block, also carrying cardiotoxic effects [

42].

Among current treatment options, mycophenolate mofetil is frequently preferred, primarily due to its more favorable safety profile compared to the known cardiotoxic risks associated with cyclophosphamide. Evidence from prospective cohort studies supports its use, demonstrating improvements in cardiac function and overall clinical outcomes. MMF has shown efficacy both as a first-line therapy in systemic rheumatic conditions like SSc, and as a second-line agent in patients with isolated, virus-negative or autoimmune lymphocytic myocarditis—particularly in those who do not tolerate or respond to azathioprine—regardless of the concurrent glucocorticoid dosage [

30]. The main immunosupressive agents used in SSc, together with their cardiovascular implications, are summarized in

Table 2.

4.7.2. Corticosteroid Therapy

Corticosteroids such as prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone, continue to play a role in managing SSc and other rheumatic conditions, thanks to their well-established anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. They exert their effects by modulating the activity of key immune cells, including macrophages, T cells, and B cells, and by influencing fibroblasts and endothelial cells, both central to the development and progression of the disease. Given their well-documented anti-inflammatory capacity and regulate immune responses, corticosteroids can help control the complex processes that drive persistent inflammation, vascular dysfunction, and fibrosis in SSc. While their use requires careful balancing of benefits and risks, they remain a valuable option in selected clinical settings [

43].

Corticosteroid therapy can have notable effects on cardiovascular function. A 2015 review documented cases of bradycardia occurring after high-dose pulse therapy with prednisolone or its equivalent, specifically at doses exceeding 250 mg per day [

44]. Additionally, a 2013 study highlighted that ventricular arrhythmias—including premature ventricular complexes, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, and sustained ventricular tachycardia—as well as sudden cardiac death, are frequently associated with myocardial fibrosis in patients with SSc. The widespread use of corticosteroids may exacerbate these arrhythmias through metabolic alterations and conduction disturbances such as hypokalemia and hypocalcemia. Moreover, corticosteroid treatment has been linked to an increased risk of atrial arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter [

45]. A recent review published in

Rheumatology Quarterly examined the risk of SSc renal crisis, which is the most feared complication associated with corticosteroid use in SSc. The study demonstrated that administering corticosteroids at doses greater than 15 mg/day for at least six months increases the risk of SSc renal crisis to 36% in patients with

diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) [

46]. The evidence regarding corticosteroid therapy use and the effects on SSc and cardiovascular is presented in

Table 3.

4.7.3. Vasodilators (Calcium Channel Blockers, Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors, Prostacyclin Analogues, Endothelin Receptor Antagonists)

Vasodilators such as calcium channel blockers (eg. nifedipine, amlodipine), phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors ( e.g. sildenafil, tadanafil), prostacyclin analogues (e.g. iloprost) and endothelin receptor antagonists (e.g. bosentan, ambrisentan) are used in SSc to treat vascular complications like Raynaud’s phenomenon, digital ulcers and pulmonary hypertension. Calcium channel blockers are considered first-line treatment for Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers, while phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are considered second-line treatment for digital ulcers, but are also indicated in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. They are contraindicated in unstable angina and recent history of myocardial infarction [

47,

48].

A 2006 study involving 21 patients with SSc, including 17 women, showed that Iloprost exerts cardiovascular effects, such as prolongation of the ventricular refractory period and QTc interval, as well as myocardial ischemia through a ‘coronary steal’ phenomenon [

48]. Thus, it is contraindicated in patients with severe coronary artery disease, a history of thrombotic events, congestive heart failure, or patients known to have severe arrhythmias, all of which may be aggravated by iloprost [

49].

Bosentan has shown encouraging results in patients with SSc, particularly in the management of digital ulcers. A recent retrospective analysis from 2025 involving 727 patients without pulmonary hypertension found that those receiving bosentan for digital ulcers had a lower risk of developing pulmonary hypertension over a two-year period [

50,

51]. Earlier, a 2011 study with 188 patients reported a 30% reduction in the number of new ulcers after 24 weeks of treatment, especially in those with multiple lesions [

52]. Another study involving 77 patients revealed that individuals with elevated endothelin-1, asymmetric dimethylarginine, and VEGF levels were more likely to experience severe microvascular complications, even while on treatment with bosentan [

53].

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, in particular, have minimal negative inotropic effects and are generally well tolerated, with reflex tachycardia and lower limb edema being the most common side effect [

54].

An exploratory analysis published in 2024, which included 1,048 patients with SSc from 42 hospitals across France, reported a decrease in the incidence of diastolic dysfunction and an improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction below 50% after three years of treatment with vasodilators, specifically sildenafil. These findings suggest a potential protective effect of sildenafil on cardiac function in patients with SSc [

55].

The most reported cardiovascular adverse effects associated with these agents include tachycardia, arterial hypotension, palpitations, and episodes of syncope [

49]. Regarding arrhythmogenic risk, some sources suggest that it is minimal; however, recent studies directly addressing this issue are lacking. To date, no conclusive evidence confirms the arrhythmogenic potential of the drug, and the topic remains insufficiently explored in the literature.

Table 4 highlights vasodilator therapies with action on SSc and potential benefits/risks on cardiovascular system.

4.7.4. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (e.g. enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril, fosinorpil, trandolapril, etc) represent the cornerstone of antihypertensive therapy in SSc renal crisis. Treatment should begin as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, or the dosage increased if the patient is already on an ACE inhibitor [

54].

A 2022 meta-analysis including nine studies found that prior use of ACE inhibitors in patients with SSc was associated with an increased risk of developing SSc renal crisis, with a reported risk ratio of 2.05. Furthermore, prognosis was poorer in these patients, with a risk ratio of 1.46, compared to those who began ACE inhibitor therapy at the time of SSc renal crisis diagnosis [

56]. Resistance to these drugs is not uncommon in patients with SSc, making gradual dose escalation necessary, often up to the maximum tolerated dose [

54]. Notably, ACE inhibitors have dramatically improved survival rates in SSc renal crisis,

reducing one-year mortality from 85% to 24%, and five-year mortality from 90% to 35%, underscoring their critical role in management [

57].

The role of ACE inhibitors in SSc, but also the cardiac effects is presented in

Table 5.

4.7.5. Antifibrotic Agents (Nintedanib)

Nintedanib is an antifibrotic agent approved for the treatment of SSc-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD), known to slow the progression of lung function decline. Its efficacy has been supported by several studies, including a 2022 trial comparing two patient groups: 197 in the SENSCIS-ON (continuing treatment) group and 247 in the SENSCIS (newly initiated) group. Over 52 weeks, patients in the SENSCIS-ON group showed a smaller average decline in forced capacity vital (−58.3 ± 15 mL) compared to the SENSCIS group (−44 ± 16.2 mL), highlighting both the effectiveness and sustained benefits of ongoing nintedanib therapy [

58]. Derrick Herman et al. (2024) realized a meta-analysis examining the efficacy of nintedanib as monotherapy compared to its use in combination with mycophenolate in patients with SSc-related ILD. The combination therapy group showed a greater reduction in forced capacity vital decline—79.1 mL less compared to 46.4 mL in the monotherapy group, indicating enhanced treatment efficacy. However, this benefit came with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal side effects in patients receiving both agents [

59].

Regarding the cardiac effects, including the potential for arrhythmias, data from the SCINSCIS trial from 2020 have also been considered. The study evaluated nintedanib versus placebo in SSc-ILD and cardiovascular adverse events were rare and comparable between groups. Notably, no arrhythmias or cardiac failure episodes were reported among those receiving nintedanib, even among patients with pulmonary hypertension at baseline [

60]. A comprehensive safety analysis from the SENSCIS trial, which monitored adverse events over approximately 100 weeks, reported no cases of myocardial infarction among patients receiving nintedanib, compared to four cases in the placebo group. Interestingly, major adverse cardiovascular events were observed less frequently in the nintedanib group [

61]. According to a pivot study published by Kawanama et al. (2023), 20 patients were ultimately included in the final analysis after applying selection criteria. Using CMR, the study observed that nintedanib treatment was linked to a reduction in myocardial inflammation and fibrosis, reflected by a lower extracellular volume. It also showed an improvement in right ventricular function. Together, these results point toward a possible cardioprotective effect of nintedanib, rather than any indication of cardiac toxicity [

62].

The evidence of antifibrotic agents in SSc and their potential effect on cardiovascular system is summarized in

Table 6.

4.7.6. Biologic Therapy

Biologic therapies have become an important pivot in the management of SSc, particularly for patients who do not respond well to conventional immunosuppressive treatments. Among these, rituximab and tocilizumab stand out for their targeted mechanisms and growing clinical use. With more clinical experience and supporting data, both agents are gaining ground as valuable additions to treatment strategies, offering new possibilities for patients with few therapeutic alternatives.

Rituximab, which targets and depletes B cells, has been linked to improvements in skin thickening and lung function. A 2024 cohort study involving 350 patients diagnosed with SSc and primary cardiac involvement evaluated the eficacity of rituximab in addition to standard immunosuppressive treatments. The results showed improvements in cardiac function and a reduction in inflammatory markers. Rituximab was generally well tolerated, without an evident increase in negative reactions relative to standard therapy alone. The authors suggest that rituximab may offer a promising adjunct treatment for patients with SSc-related myocarditis by targeting B-cell-mediated inflammation. However, larger studies are needed to confirm these findings and establish clear treatment protocols [

63].

In a recent cohort study from June 2025, ten patients diagnosed with SSc and primary cardiac involvement, who had not responded to cyclophosphamide treatment, were initiated on rituximab in combination with mycophenolate mofetil. The results showed an improvement in cardiac function and a reduction in fibrosis, suggesting a potentially beneficial cardiovascular effect. Even so, further studies are needed, particularly regarding the arrhythmogenic risk [

64].

Tocilizumab, a blocker of the interleukin-6 receptor, has also shown potential in slowing disease progression and lowering inflammatory activity. A 2022 study aimed at evaluating the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with SSc used data from the EUSTAR registry and included 93 patients treated with tocilizumab compared to 3,180 patients receiving standard therapies. Outcomes were assessed at the cutaneous and pulmonary levels after 12 ± 3 months, using the modified Rodnan skin score and forced vital capacity. The findings showed some improvement in the progression of skin thickening and pulmonary fibrosis, although the results did not reach statistical significance in terms of efficacy. Regarding cardiovascular effects, isolated cases of atrial flutter, heart failure, and sudden death were reported [

65]. Also, in the context of combining tocilizumab with immunosuppressive therapy- in this case cyclophosphamide, a case report published in July 2025 describes the clinical course of a 25-year-old female patient with a severe form of SSc. The dual therapy resulted in clear clinical improvement: cardiac symptoms stabilized, heart function improved, and laboratory markers reflecting inflammation and fibrosis declined, pointing to a positive effect on myocardial involvement. The treatment was well tolerated, and no significant cardiac adverse events, including arrhythmias, were reported [

66].

In conclusion, while rituximab and tocilizumab are already part of current treatment approaches, several other biologic agents remain under clinical investigation. Trials involving abatacept, belimumab, romilkimab, and fresolimumab are in progress to assess their safety profile, therapeutic efficacy, and effects on the immune and fibrotic mechanisms underlying SSc. The results of these studies will help define the place of these therapies in future treatment strategies, to optimize management strategies for this multifaceted disease.

In the

Table 2, the effects of medications in SSc are detailed, addressing both their impact on the underlying disease and on the cardiovascular system.

Table 7 outlines the main biologic agents evaluated in SSc and their potential role in modulating cardiovascular involvement.

6. Diagnostic of Arrhythmias in Systemic Sclerosis

The diagnostic approach to arrhythmias in SSc has envolved considerably, comprising a range of modalities from standard laboratory evaluations to advanced imaging techniques. These tools seek to identify both structural and functional cardiac abnormalities associated with arrhythmogenic risk in this patient group. Cardiac involvement in SSc has been correlated with multiple clinical and immunological factors. These include male sex, the diffuse cutaneous form of SSc (dcSSc), accelerated skin thickening in the context of anti-topoisomerase I antibodies, and the presence of autoantibodies such as anti-Ku, anti-Histone, anti-RNA polymerase III, and anti-U3-RNP. Additional predictors include disease onset after age 65, tendon friction rubs, digital ischemia or ulcers, interstitial lung disease, and coexisting myositis [

67]. Recognition of these markers may assist in identifying patients with a higher probability of developing cardiac complications, making it necessary to close clinical monitoring. In a study analyzing 216 patients with SSc, it was demonstrated that anti-Th/To antibodies were more frequently associated with pericarditis compared to anticentromere antibodies [

68].

At the same time, several tools have been developed to support the early identification of patients with a higher risk of cardiovascular complications. Among the most widely used are scoring systems like the Framingham Risk Score and QRISK3. These models have become especially useful in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, including SSc. By estimating a person’s overall cardiovascular risk, they help guide doctors in making informed decisions about who might benefit from early preventive strategies—ultimately with the goal of reducing the chances of heart-related illness and death [

30].

Regarding biochemical markers of cardiac involvement in the context of autoimmune diseases, such as SSc, BNP and NT-proBNP have proven to be reliable indicators of myocardial dysfunction. In patient cohorts with SSc, elevated NT-proBNP levels have been associated with more severe valvular disease and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction compared to the healthy population. Troponins I and T, particularly high-sensitivity variants, serve as valuable adjunctive biochemical markers for assessing the extent of myocardial involvement. They have demonstrated high accuracy in identifying cardiovascular damage within the context of systemic autoimmune diseases [

69].

Among the standard tools for cardiovascular assessment, ECG remains the most frequently employed and essential method for detecting arrhythmias. Common ECG findings in patients with autoimmune diseases include QT interval prolongation, bundle branch blocks, and ventricular hypertrophy [

30]. The 24-hour Holter ECG monitoring has become one of the most used methods in providing a more comprehensive evaluation of arrhythmic occurrence, particularly in detecting arrhythmias that may go unnoticed during a standard ECG. This method can identify supraventricular arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation, which often necessitates prompt intervention, as well as ventricular arrhythmias, with ventricular extrasystoles being the most frequently encountered. Complementary abnormalities identified through ECG or Holter monitoring may include atrioventricular blocks, right or left bundle branch blocks, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, and nonspecific ST-T wave changes [

45].

A recent study looking at arrhythmia risk in patients with SSc and heart involvement found that sudden cardiac death occurred in a majority of cases. This revealed a striking finding, these individuals face a tenfold higher risk of sudden cardiac death compared to the general population [

70].

Echocardiography remains a cornerstone in the evaluation of cardiovascular involvement in SSc, despite the availability of more advanced imaging techniques. While the underlying pathophysiology involves fibrogenesis and myocardial replacement with fibrotic tissue, studies show that only a small subset of patients with cardiac involvement exhibit a mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (40–49%). A significantly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (<40%) is rare and usually not a direct consequence of autoimmune fibromuscular degeneration alone. It also plays a critical role in identifying pericardial involvement, which is common in SSc [

71]. In patients with SSc, the presence of pericardial effusion often indicate to more advanced or severe heart involvement. It may be associated with conditions like congestive heart failure, pulmonary arterial hypertension, or other forms of pulmonary vascular disease. One of the most serious and potentially life-threatening complications is when pericardial effusion occurs alongside pericarditis and cardiac tamponade- a combination that significantly raises the risk of both illness and death [

71,

72].

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging has become an important supportive tool for echocardiography when a more detailed view of heart structure and function is needed. In patients with SSc, CMR has been able to detect signs of diastolic dysfunction in both ventricles, even in cases where echocardiography appears normal. One of the primary benefits of CMR is its ability to identify late gadolinium enhancement, a reliable indicator of myocardial fibrosis that might otherwise go unnoticed [

73].

In a study of 344 patients with SSc, late gadolinium enhancement was found in about 25% of participants and was significantly connected to both digital ulcers and ventricular arrhythmias. Another recent study focusing on SSc patients with myocarditis highlighted the value of CMR in distinguishing between inflammatory and fibrotic lesions. Even more importantly, it was able to differentiate which of these changes were potentially reversible and which were permanent, an essential distinction for guiding treatment and assessing long-term prognosis [

30].

A more recent valuable imaging tool in the evaluation of cardiac involvement in SSc is positron emission tomography. This technique offers precise analyses into both myocardial metabolism and function. In one study, patients with SSc and Raynaud’s phenomenon were found to have a significantly reduced myocardial flow reserve when examinated by Positron emission tomography. Another innovative study explored the use of positron emission tomography imaging to detect fibroblast activation with the radiotracer [(68 Ga)Ga-FAPI-04]. It found that patients with arrhythmias and elevated NT-proBNP levels showed increased radiotracer uptake, pointing to a possible connection between fibroblast activity, myocardial fibrosis, and a higher risk of arrhythmias [

74,

75].

5. Management of Arrhythmias in Rheumatology Diseases with Focus on Systemic Sclerosis

Taking into consideration the multiple ways that SSc can damage the heart, there is a large terapeutical arsenal that the clinician could take advantage of , but it must be used wisely in order to treat each patological manifestation, no matter whether it is an inflamatory problem, an electrical issue or perhaps cardiac failure.

Beta-blockers can be used, should premature atrial or ventricular ectopic beats manifest in a symptomatic matter or if the amount cuantified in 24h is significant. If myocardial ischaemia is also suspected, it is recommended that beta-blockers are used as a first line of treatment and this aspect should be thorougly taken into consideration noting that coronary atherosclerosis is more frequent and more severe than in the general population. Although this medication has many uses, care should be taken as there is an important risk of exacerbating Raynaud’s phenomenon, as well as digital ulcerations. With this in mind, cardioselective beta-blockers are definetely the preffered option and in cases of heart rates > 70/min, Ivabradine is also an option. In the event that patients develop severe bradycardia with syncope, important atrioventricular blocks (such as high-grade blocks, comple heart blocks etc) and other conduction disturbances, the guidelines recommend pacemaker implantation. Should malignant ventricular arrhytmias appear, an implantable cardioverter defibrillator is required for sudden cardiac death prevention. When arrhtymias such as atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter are objectified on the surface ECG or the Holter monitoring, there is should be no holding back regarding the prescription of anticoagulants and direct oral anticoagulants should be the preferred option [

30,

76].

5.1. Cardiac Complications in Systemic Sclerosis Associated with Arrhythmias

The complications associated with SSc as pericarditis and myocarditis are an important structural substrate for arrhythmias. Optimal therapy of SSc can reduce the occurrence of these cardiac complications, which are associated with a high percentage of supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias. The first line of treatment in patients that develop symptomatic pericarditis, as in many other types of pericarditis, is considered to be NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). This medication proved to be effective in relieving inflammation, however it should be used with caution in the event that patients have or develop upper gastrointestinal problems (for example gastritis), or colchinice may be instead used and even high doses of glucocortocoids. There are cases when the fluid build-up is very significant so pericardial drainage may be needed [

76].

If the patient suffers from symptomatic myocarditis confirmed by CMR, it is well established in the literature that the use of imunosuppressive drugs is needed, as myocardial involvement is common and one of the leading causes of death among SSc patients. Corticotherapy plays a primary role and it can be administered both oraly and intravenous. Drugs such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate, MM represent the pinnacle imunotherapy, used either separately or in combination with GCs. There is still the need for further studies that elaborate the topic, but as of now MMF appears to have the best safety profile and has provided the best theraputical results, making it the most used drug out of its category [

30].

Heart failure could be associated with any arrhythmia because of the high grade level of myocardial fibrosis. Patients with SSc can develop heart failure and conventional treatment should be used as the ESCs guidelines recommend. The 4 pillars of heart failure have been very well cemented by numerous studies and include ACE inhibitors/ARBs (angiotensin II receptor blockers)/ARNI (angiotensin II receptor-neprilysin inhibitor), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sodium glucoso co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and beta-blockers. Although this medication is safe and proved to be efficient in treating HF, there is a minor aspect that should be mentioned – SSc patients that are treated with ACE display a risk for developing SSc renal crisis. ACE are still the first line of treatment in this category, however great caution is needed when there is a high risc of developing SSc renal crisis [

77].

Pulmonary hypertension could be a feared complication in SSc. All patients that develop pulmonary hypertension should be redirected to a specialised pulmonary arterial hypertension center as they require multidisciplinary coordination, having a poor prognosis long term. Thankfully there are therapeutical options that proved to be succesful as well as new treatment options that provided encouraging results in multiple clinical trials, raising the bar in terms of efficiency, safety profile and tolerability Endothelin receptor antagonist Bosentan has been approved for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension and has provided impressive results. It has been considered the pinnacle therapy in this category of pacients and as of recently it has been certified as safe to use for patients that suffer from autoimmune diseases, more specifically connective tissue diseases like SSc. The dosage of 62.5 mg used twice a day is being uptitrated to 125 mg after a month (in the mornings and evenings), however hepatic tolerance and hemoglobin levels are mandatory to be checked. This medication benefits in preventing digital ulcers making it the first line of treatment in SSc-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ambrisentan is also a safe option with the advantage of being prescribed as a single pill daily (5 mg that can be increased up to 10 mg a day). To be noted that it is contraindicated in cases of pulmonary fibrosis and SSc patients do develop interstitial lung disease, requiring caution. Another class of medication used in treating SSc with pulmonary arterial hypertension is phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors Sildenafil and Tadalafil, approved for NYHA II or III functional classes. There are no parameters to be monitored when prescribing this therapy [

78,

79].

6. Prevention of Arrhythmias in Rheumatology Diseases

There are several essential pillars in the prevention of arrhythmias among patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases, particularly SSc. The foremost and perhaps most critical is cardiac screening and risk stratification. If implemented consistently, this approach could potentially alter the disease trajectory and prevent abrupt progression. The main diagnostic methods for identifying potential cardiac involvement in SSc include routine cardiology consultations, standard ECG, and echocardiographic evaluation of both structural and functional cardiac abnormalities. These tools facilitate the early detection and management of arrhythmias associated with SSc.

A prompt and accurate management of the diverse manifestations of cardiac involvement forms the second pillar of prevention. Initiating immunosuppressive therapy to control both inflammation and fibrosis — the pathological hallmarks of SSc — has been shown to reduce the risk of arrhythmia development. Moreover, antifibrotic agents used primarily for pulmonary fibrosis have demonstrated indirect benefits in attenuating myocardial fibrosis, further supporting their role in cardiac protection.

Given that dysfunction in one organ system often leads to secondary involvement of others, effective management of comorbidities is crucial, especially in this patient category. Additionally, careful selection of pharmacological therapies can significantly influence disease outcomes. For instance, the use of beta-blockers must be judicious, as they may exacerbate Raynaud’s phenomenon witch is a frequent complication in SSc.

Lastly, but equally important, is patient education. Informing patients about the potential cardiac symptoms and complications associated with SSc can promote early referral to cardiology specialists and facilitate timely therapeutic intervention and disease monitoring.

7. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Heart team is a well known concept in cardiology next to multidisciplinary team aims to change the prognosis of the patients with complexe cardiac pathologies. The involvement of a multidisciplinary team and interdisciplinary collaboration promote earlier diagnosis of the pathology, correct identification of the severity of cardiac involvement, and personalization of therapeutic methods. All of these can modify the prognosis of the patient with such a complex pathology as SSc.

When it comes to heart rhythm problems in SSc, things are getting better at catching them early. New heart scans like CMR can find tiny scars in the heart muscle before you even notice symptoms. Ultrasound tests and longer heart monitoring help doctors spot irregular heartbeats that might have been missed before.

On the treatment side, doctors aren’t just waiting for problems to show up anymore. They’re trying to slow down or stop the heart damage by using medicines that calm the immune system and reduce scarring. When arrhythmias do happen, common medicines like beta-blockers are still used, but newer treatments and procedures, like catheter ablation, are helping in tougher cases. For some patients, devices like defibrillators can save lives by preventing sudden heart stops.

The future looks hopeful because we’re moving toward diagnosing early and treating them in a way that goes beyond just the symptoms. It’s a team effort formed by rheumatologists, cardiologists, arrhythmologist, pneumologist, dermatologist, gasteroenterologist, nephrologist, togheter with internal medicine, rehabilitation medicine and heart rhythm specialists working to give patients the best care possible. This multidisciplinary team involved in the management and monitoring of patients with SSc must include, also, the nurses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.C., V.U, M.C.D., C.I.M.A. and M.F.; methodology, V.U.; A.O. and D.E.F; validation, V.U., C.I.M.A. and M.F.; formal analysis, D.E.C., M.C.D., S.M.S., G.L.B. and M.M.G; investigation, V.U.; D.E.C. and M.C.D.; resources, D.T.M.; D.M.T. and A.K.; data curation, A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, V.U., P.C.M., A.F.O., M.M.G. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, V.U., M.F., D.E.F., D.M.T., A.K., C.I.M.A., S.M.S. and G.L.B.; visualization, V.U., D.E.C., M.C.D. and M.F.; supervision, A.O., C.I.M.A., and A.K..; project administration, D.E.C., M.C.D., D.M.T., D.E.F. and S.M.S.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSc |

Systemic sclerosis |

| SSc-ILD |

SSc-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease |

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| Ang I |

Angiotensin I |

| Ang II |

Angiotensin II |

| ET-1 |

Endothelin-1 |

| CMR |

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ANS |

Autonomic Nerve System |

| sPAP |

Pulmonary Artery Pressure |

| HRT |

Heart Rate Turbulance |

| RAAS |

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System |

| ACE |

Angiotensin- Converting Enzyme |

| ACE 2 |

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| EAT |

Epicardial Adipose Tissue |

| GCs |

Glucocorticoids |

| MMF |

Mycophenolate mofetil |

| MTX |

Methotrexate |

| AZA |

Azathioprine |

| CYC |

Cyclophosphamide |

| mRSS |

Modified Rodnan Skin Score |

| HF |

Heart Failure |

| AT2R |

Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor |

| RVSP |

Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure |

| dcSSc |

Diffuse Cutaneous SSc |

References

- Careta, M.F.; Romiti, R. Localized Scleroderma: Clinical Spectrum and Therapeutic Update. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2015, 90, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seferović, P.M.; Ristić, A.D.; Maksimović, R.; Simeunović, D.S.; Ristić, G.G.; Radovanović, G.; Seferović, D.; Maisch, B.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Cardiac Arrhythmias and Conduction Disturbances in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006, 45, iv39–iv42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienias, P.; Ciurzyński, M.; Glińska-Wielochowska, M.; Korczak, D.; Kalińska-Bienias, A.; Gliński, W.; Pruszczyk, P. Heart Rate Turbulence Impairment and Ventricular Arrhythmias in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology 2010, 33, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrancianu, C.A.; Gheorghiu, A.M.; Popa, D.E.; Chan, J.S.K.; Satti, D.I.; Lee, Y.H.A.; Hui, J.M.H.; Tse, G.; Ancuta, I.; Ciobanu, A.; et al. Arrhythmias and Conduction Disturbances in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis—A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, A.M. Atrial Fibrillation and Ventricular Arrhythmias. Circulation 2017, 135, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, A.; Meune, C.; Gordon, J.; Chung, L.; Proudman, S.; Assassi, S.; Nikpour, M.; Rodriguez-Reyna, T.S.; Khanna, D.; Lafyatis, R.; et al. Cardiac Arrhythmias and Conduction Defects in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014, 53, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarz, E.; Rudnicka, L.; Samochocki, Z. Sinoatrial Conduction Abnormalities – an Underestimated Cardiac Complication in Women with Systemic Sclerosis. Adv Dermatol Allergol 2021, 38, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.; Costello, B.; Brown, Z.; Hansen, D.; Lindqvist, A.; Stevens, W.; Burns, A.; Prior, D.; Nikpour, M.; La Gerche, A. Myocardial Fibrosis and Arrhythmic Burden in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022, 61, 4497–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.A.; Jeppesen, J.L.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Sam, F.; Gislason, G.H.; Jacobsen, S.; Andersson, C. Cardiovascular Manifestations of Systemic Sclerosis: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Journal of the American Heart Association 2019, 8, e013405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifkazemi, M.; Nazarinia, M.; Arjangzade, A.; Goldust, M.; Hooshanginezhad, Z. Diagnosis of Simultaneous Atrial and Ventricular Mechanical Performance in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Biology 2022, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Right Ventricular and Atrial Functions in Systemic Sclerosis Patients without Pulmonary Hypertension | Herz. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00059-014-4113-2 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Tello, K.; Dalmer, A.; Vanderpool, R.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Naeije, R.; Roller, F.; Seeger, W.; Wiegand, M.; Gall, H.; Richter, M.J. Right Ventricular Function Correlates of Right Atrial Strain in Pulmonary Hypertension: A Combined Cardiac Magnetic Resonance and Conductance Catheter Study. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2020, 318, H156–H164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienias, P.; Ciurzyński, M.; Korczak, D.; Jankowski, K.; Glińska-Wielochowska, M.; Liszewska-Pfejfer, D.; Gliński, W.; Pruszczyk, P. Pulmonary Hypertension in Systemic Sclerosis Determines Cardiac Autonomic Dysfunction Assessed by Heart Rate Turbulence. International Journal of Cardiology 2010, 141, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction Correlates with Microvascular Damage in Systemic Sclerosis Patients - Francesco Masini, Raffaele Galiero, Pia Clara Pafundi, Klodian Gjeloshi, Emanuele Pinotti, Roberta Ferrara, Ciro Romano, Luigi Elio Adinolfi, Ferdinando Carlo Sasso, Giovanna Cuomo, 2021. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23971983211020617 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Autonomic Dysfunction Predicts Early Cardiac Affection in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis - Khaled M. Othman, Naglaa Youssef Assaf, Hanan Mohamed Farouk, Iman M. Aly Hassan, 2010. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.4137/CMAMD.S4940 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Masini, F.; Galiero, R.; Pafundi, P.C.; Gjeloshi, K.; Pinotti, E.; Ferrara, R.; Romano, C.; Adinolfi, L.E.; Sasso, F.C.; Cuomo, G. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction Correlates with Microvascular Damage in Systemic Sclerosis Patients. Journal of Scleroderma and Related Disorders 2021, 6, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Rauf, A.; Khan, H.; Abu-Izneid, T. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone (RAAS): The Ubiquitous System for Homeostasis and Pathologies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 94, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranduca, M.A.; Cosovanu, M.A.; Clim, A.; Pinzariu, A.C.; Filip, N.; Drochioi, I.C.; Vlasceanu, V.I.; Timofte, D.V.; Nemteanu, R.; Plesa, A.; et al. The Renin-Angiotensin System: The Challenge behind Autoimmune Dermatological Diseases. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, C.M.; Groban, L.; Wang, H.; Cheng, C.P.; VonCannon, J.L.; Wright, K.N.; Sun, X.; Ahmad, S. The Angiotensin-(1–12)/Chymase Axis as an Alternate Component of the Tissue Renin Angiotensin System. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2021, 529, 111119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, Y.M.; Noto, N.M.; Speth, R.C. CGP42112: The Full AT2 Receptor Agonist and Its Role in the Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System: No Longer Misunderstood. Clin Sci (Lond) 2022, 136, 1513–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemekasten, G.; Philippe, A.; Näther, M.; Slowinski, T.; Müller, D.N.; Heidecke, H.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Czirják, L.; Lukitsch, I.; Becker, M.; et al. Involvement of Functional Autoantibodies against Vascular Receptors in Systemic Sclerosis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2011, 70, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kill, A.; Tabeling, C.; Undeutsch, R.; Kühl, A.A.; Günther, J.; Radic, M.; Becker, M.O.; Heidecke, H.; Worm, M.; Witzenrath, M.; et al. Autoantibodies to Angiotensin and Endothelin Receptors in Systemic Sclerosis Induce Cellular and Systemic Events Associated with Disease Pathogenesis. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2014, 16, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiducci, S.; Fatini, C.; Rogai, V.; Cinelli, M.; Sticchi, E.; Abbate, R.; Cerinic, M.M. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme in Systemic Sclerosis: From Endothelial Injury to a Genetic Polymorphism. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006, 1069, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinovitch, U.; Shoenfeld, Y. Atherosclerosis and Macrovascular Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis: Myth or Reality. Autoimmunity Reviews 2011, 10, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; Afeltra, A.; Shoenfeld, Y. Is Atherosclerosis Accelerated in Systemic Sclerosis? Novel Insights. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 2014, 26, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, X.; Adhikari, B.K.; Chen, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. The Role of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Management. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukbi, E.; Soghomonian, A.; Sengenès, C.; Ahmed, S.; Ancel, P.; Dutour, A.; Gaborit, B. Browning Epicardial Adipose Tissue: Friend or Foe? Cells 2022, 11, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Butcher, S.C.; Myagmardorj, R.; Liem, S.I.E.; Delgado, V.; Bax, J.J.; De Vries-Bouwstra, J.K.; Marsan, N.A. Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Eur Heart J - Imaging Methods Practice 2023, 1, qyad037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conte, M.; Petraglia, L.; Cabaro, S.; Valerio, V.; Poggio, P.; Pilato, E.; Attena, E.; Russo, V.; Ferro, A.; Formisano, P.; et al. Epicardial Adipose Tissue and Cardiac Arrhythmias: Focus on Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadel, A.; Nadel, M.; Taborska, N.; Stępień, B.; Gajdecki, J.; Brzezińska, O.; Opinc-Rosiak, A.; Makowska, J.; Lewandowska-Polak, A. Heart Involvement in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis—What Have We Learned about It in the Last 5 Years. Rheumatol Int 2024, 44, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, X.; Feng, S.; Wei, S.; Yan, L.; Sun, L. Systemic Sclerosis and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e23009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannarile, F.; Valentini, V.; Mirabelli, G.; Alunno, A.; Terenzi, R.; Luccioli, F.; Gerli, R.; Bartoloni, E. Cardiovascular Disease in Systemic Sclerosis. Ann Transl Med 2015, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherif, N.; Turitto, G. Electrolyte Disorders and Arrhythmogenesis. Cardiol J 2011, 18, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Takada, T.; Aoki, A.; Shima, K.; Kikuchi, T. Advancements in the Treatment of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Sclerosis with the Approval of Mycophenolate Mofetil. Respiratory Investigation 2024, 62, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baqir, M.; Makol, A.; Osborn, T.G.; Bartholmai, B.J.; Ryu, J.H. Mycophenolate Mofetil for Scleroderma-Related Interstitial Lung Disease: A Real World Experience. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0177107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, Z.; Ardestani, V.; Tamartash, Z.; Karimi, E.; Kavosi, H. Arrhythmia as a Possible Complication of Mycophenolate Mofetil in Systemic Sclerosis: A Case Report. Case Reports in Medicine 2025, 2025, 8858671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frech, T.M.; Shanmugam, V.K.; Shah, A.A.; Assassi, S.; Gordon, J.K.; Hant, F.N.; Hinchcliff, M.E.; Steen, V.; Khanna, D.; Kayser, C.; et al. Treatment of Early Diffuse Systemic Sclerosis Skin Disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013, 31, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Haeger-Overstreet, K.; Flynn, B. Methotrexate-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity Requiring Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support: A Case Report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2022, 16, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torun, E.S.; Ertaş, E.; Bayyiğit, A.; Uğurlukişi, B. Effect of Azathioprine on Skin and Lung Parameters in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Literature Review. Medical Research Archives 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Internal Medicine and Rheumatology “Sf. Maria” Hospital, Bucharest, Romania; Oprea, V.D.; Bojinca, V.C.; Department of Internal Medicine and Rheumatology “Sf. Maria” Hospital, Bucharest, Romania; Balosin, G.; Department of Cardiology, “Sf. Maria” Hospital, Bucharest, Romania; Ciofu, R.N.; Department of Plastic Surgery, “Sf. Maria” Hospital, Bucharest, Romania; Ionescu, R.; Department of Internal Medicine and Rheumatology “Sf. Maria” Hospital, Bucharest, Romania Severe Systemic Scleroderma with Multiple Organ Involvement in a 45-Years-Old Patient. Ro J Rheumatol. 2021, 30, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Baron, F.; Singh, R.; Lynch, B. 83. Asymptomatic Cardiac Arrhythmia in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatol Advanc Pract 2018, 2, rky034.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Burkart, T.A. Transient, High-Grade Atrioventricular Block from High-Dose Cyclophosphamide. Tex Heart Inst J 2013, 40, 626–627. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, T.-I.; van Caam, A.; van der Kraan, P.M.; Thurlings, R.M. Therapeutic Options for Systemic Sclerosis: Current and Future Perspectives in Tackling Immune-Mediated Fibrosis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroeder, J.; Evans, C.; Mansell, H. Corticosteroid-Induced Bradycardia. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2015, 148, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, A.; Meune, C.; Gordon, J.; Chung, L.; Proudman, S.; Assassi, S.; Nikpour, M.; Rodriguez-Reyna, T.S.; Khanna, D.; Lafyatis, R.; et al. Cardiac Arrhythmias and Conduction Defects in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014, 53, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdoğan, M.R.; Albayrak, F.; Karataş, A.; Koca, S.S.; Akdoğan, M.R.; Albayrak, F.; Karataş, A.; Koca, S.S. SCLERODERMA RENAL CRISIS. Rheumatology Quarterly 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guédon, A.F.; Carrat, F.; Mouthon, L.; Launay, D.; Chaigne, B.; Pugnet, G.; Lega, J.-C.; Hot, A.; Cottin, V.; Agard, C.; et al. Vasodilator Drugs and Heart-Related Outcomes in Systemic Sclerosis: An Exploratory Analysis. RMD Open 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guideri, F.; Acampa, M.; Rechichi, S.; Capecchi, P.L.; Lazzerini, P.E.; Galeazzi, M.; Auteri, A.; Laghi-Pasini, F. Effects of Acute Administration of Iloprost on the Cardiac Autonomic Nervous System and Ventricular Repolarisation in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006, 65, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournia, V.-K.; Tountas, C.; Protogerou, A.D.; Panopoulos, S.; Mavrogeni, S.; Sfikakis, P.P. Update on Assessment and Management of Primary Cardiac Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2018, 3, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammi, M.R.; Mukherjee, M. Unveiling the Dual Benefits of Bosentan in Systemic Sclerosis: Risk and Relief. The Journal of Rheumatology 2025, 52, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciapaglia, F.; De Angelis, R.; Ferri, C.; Bajocchi, G.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Bruni, C.; Orlandi, M.; Fornaro, M.; Cipolletta, E.; Zanframundo, G.; et al. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Incidence in Patients With Systemic Sclerosis Treated With Bosentan for Digital Ulcers: Evidence From the SPRING-SIR Registry. J Rheumatol 2025, 52, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Denton, C.P.; Furst, D.E.; Mayes, M.D.; Hsu, V.M.; Carpentier, P.; Wigley, F.M.; Black, C.M.; Fessler, B.J.; Merkel, P.A.; et al. Bosentan Treatment of Digital Ulcers Related to Systemic Sclerosis: Results from the RAPIDS-2 Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011, 70, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Teixeira, A.; Oliveira, J.; Almeida, I.; Almeida, R.; Vasconcelos, C. Predictive Value of Vascular Disease Biomarkers for Digital Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis Patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015, 33, S127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac Manifestations in Systemic Sclerosis. Available online: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i9/993.htm (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Guédon, A.F.; Carrat, F.; Mouthon, L.; Launay, D.; Chaigne, B.; Pugnet, G.; Lega, J.-C.; Hot, A.; Cottin, V.; Agard, C.; et al. Vasodilator Drugs and Heart-Related Outcomes in Systemic Sclerosis: An Exploratory Analysis. RMD Open 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; Cao, Y.; Xiang, Q.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Qiang, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z.; Cui, H.; et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Prior to Scleroderma Renal Crisis in Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2022, 47, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheen, M.; Dominati, A.; Olivier, V.; Nasr, S.; De Seigneux, S.; Mekinian, A.; Issa, N.; Haidar, F. Renal Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis. Autoimmunity Reviews 2023, 22, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanore, Y.; Vonk, M.C.; Distler, O.; Azuma, A.; Mayes, M.D.; Gahlemann, M.; James, A.; Kohlbrenner, V.; Alves, M.; Khanna, D.; et al. Continued Treatment with Nintedanib in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Data from SENSCIS-ON. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2022, 81, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, D.; Ghazipura, M.; Barnes, H.; Macrea, M.; Knight, S.L.; Silver, R.M.; Montesi, S.B.; Raghu, G.; Hossain, T. Nintedanib Therapy Alone and Combined with Mycophenolate in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis–Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Annals ATS 2024, 21, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibold, J.R.; Maher, T.M.; Highland, K.B.; Assassi, S.; Azuma, A.; Hummers, L.K.; Costabel, U.; Wangenheim, U. von; Kohlbrenner, V.; Gahlemann, M.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Nintedanib in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Data from the SENSCIS Trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2020, 79, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assassi, S.; Distler, O.; Allanore, Y.; Ogura, T.; Varga, J.; Vettori, S.; Crestani, B.; Voss, F.; Alves, M.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Effect of Nintedanib on Progression of Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease Over 100 Weeks: Data From a Randomized Controlled Trial. ACR Open Rheumatology 2022, 4, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninagawa, K.; Kato, M.; Tsuneta, S.; Ishizaka, S.; Ujiie, H.; Hisada, R.; Kono, M.; Fujieda, Y.; Ito, Y.M.; Atsumi, T. Beneficial Effects of Nintedanib on Cardiomyopathy in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2023, 62, 2550–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.; Tonutti, A.; Motta, F.; Rodolfi, S.; Monti, L.; Catapano, F.; Francone, M.; Selmi, C. Add-on Rituximab for Primary Heart Involvement Associated with Systemic Sclerosis: A Step Forward in the Tailored Treatment of Myocarditis? European Journal of Heart Failure 2025, 27, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjailia, E.-B.; Grasshoff, H.; Schinke, S.; Fourlakis, K.; Jendrek, S.T.; Lamprecht, P.; Riemekasten, G.; Humrich, J.Y. Combination Therapy of Rituximab and Mycophenolate in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis and Primary Cardiac Involvement Refractory to Cyclophosphamide: A Retrospective Exploratory Analysis of 10 Cases. RMD Open 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, S.; Jordan, S.; Elhai, M.; Held, U.; Steigmiller, K.; Bruni, C.; Cacciapaglia, F.; Vettori, S.; Siegert, E.; Rednic, S.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Tocilizumab in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Propensity Score Matched Controlled Observational Study of the EUSTAR Cohort. RMD Open 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.-C.; Ji, J.; Cheng, X.-G.; Shi, R.-G.; Mo, X.-F.; Yang, Z.-Z. Tocilizumab Combined with Cyclophosphamide for the Treatment of Rapidly Progressive Refractory Systemic Sclerosis with Predominant Cardiac Involvement: A Case Report. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissell, L.-A.; Anderson, M.; Burgess, M.; Chakravarty, K.; Coghlan, G.; Dumitru, R.B.; Graham, L.; Ong, V.; Pauling, J.D.; Plein, S.; et al. Consensus Best Practice Pathway of the UK Systemic Sclerosis Study Group: Management of Cardiac Disease in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017, 56, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceribelli, A.; Cavazzana, I.; Franceschini, F.; Airò, P.; Tincani, A.; Cattaneo, R.; Pauley, B.A.; Chan, E.K.L.; Satoh, M. Anti-Th/To Are Common Antinucleolar Autoantibodies in Italian Patients with Scleroderma. The Journal of Rheumatology 2010, 37, 2071–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.J. Paik, D.Y. Choi, M. Mukherjee, S. Hsu, F. Wigley, A.A. Shah, L.K. Hummers. Troponin Elevation Independently Associates with Mortality in Systemic Sclerosis. Available online: https://www.clinexprheumatol.org/abstract.asp?a=17767 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Wong, C.X.; Brown, A.; Lau, D.H.; Chugh, S.S.; Albert, C.M.; Kalman, J.M.; Sanders, P. Epidemiology of Sudden Cardiac Death: Global and Regional Perspectives. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2019, 28, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basyal, B.; Ullah, W.; Derk, C.T. Pericardial Effusions and Cardiac Tamponade in Hospitalized Systemic Sclerosis Patients: Analysis of the National Inpatient Sample. BMC Rheumatology 2023, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Gordon, J.K.; Xu, J.; Kolstad, K.D.; Chung, L.; Steen, V.D.; Bernstein, E.J. ; PHAROS Investigators Prognostic Significance of Pericardial Effusion in Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Pulmonary Hypertension: Analysis from the PHAROS Registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, P.; Ruscitti, P.; Cannizzaro, E.; Berardicurti, O.; Conforti, A.; Di Cesare, A.; Di Cola, I.; Giacomelli, R.; Splendiani, A.; Barile, A.; et al. Unenhanced Cardiac Magnetic Resonance May Improve Detection and Prognostication of an Occult Heart Involvement in Asymptomatic Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]