1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The world’s population aged 60 years and older is expected to more than double by 2050 to 2.1 billion, with significant repercussions for public health, economic output, and workforce participation [

1,

2]. The promotion of continued workforce participation among older adults has become a key policy focus in several countries, aiming to mitigate pension costs, address workforce shortages, and reduce social isolation among this demographic.

Concurrently, the rise of remote and flexible work arrangements, intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, has transformed the organization and delivery of work across sectors. Although remote work offers potential benefits for older adults, such as autonomy, reduced physical strain, and the ability to manage health and caregiving responsibilities better, it also presents unique challenges. Digital exclusion, ergonomic limitations, reduced social interaction, and age-related discrimination may hinder older workers’ ability to thrive in virtual environments [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Despite these emerging dynamics, the intersection of remote work and aging remains underexplored, particularly in terms of workforce participation, well-being, and equity outcomes for adults aged 45 years and older.

Telecommuting is increasingly recognized as a determinant of health that affects physical activity, concentration, perceived psychological stress levels, and the likelihood of social participation [

7,

8]. These are fundamental tools, such as the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, which highlights the importance of supportive environments, building personal capacity, and reshaping services to favor the establishment of healthy environments in all areas [

9]. In older age, telecommuting can either enhance or compromise functional capacity depending on how it is implemented and practiced.

Furthermore, the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing framework emphasizes the need for age-inclusive policies to enhance both quality and length of life through environments that promote continued autonomy and engagement [

10]. This highlights the need to examine the compatibility of remote work arrangements with health promotion principles in later life.

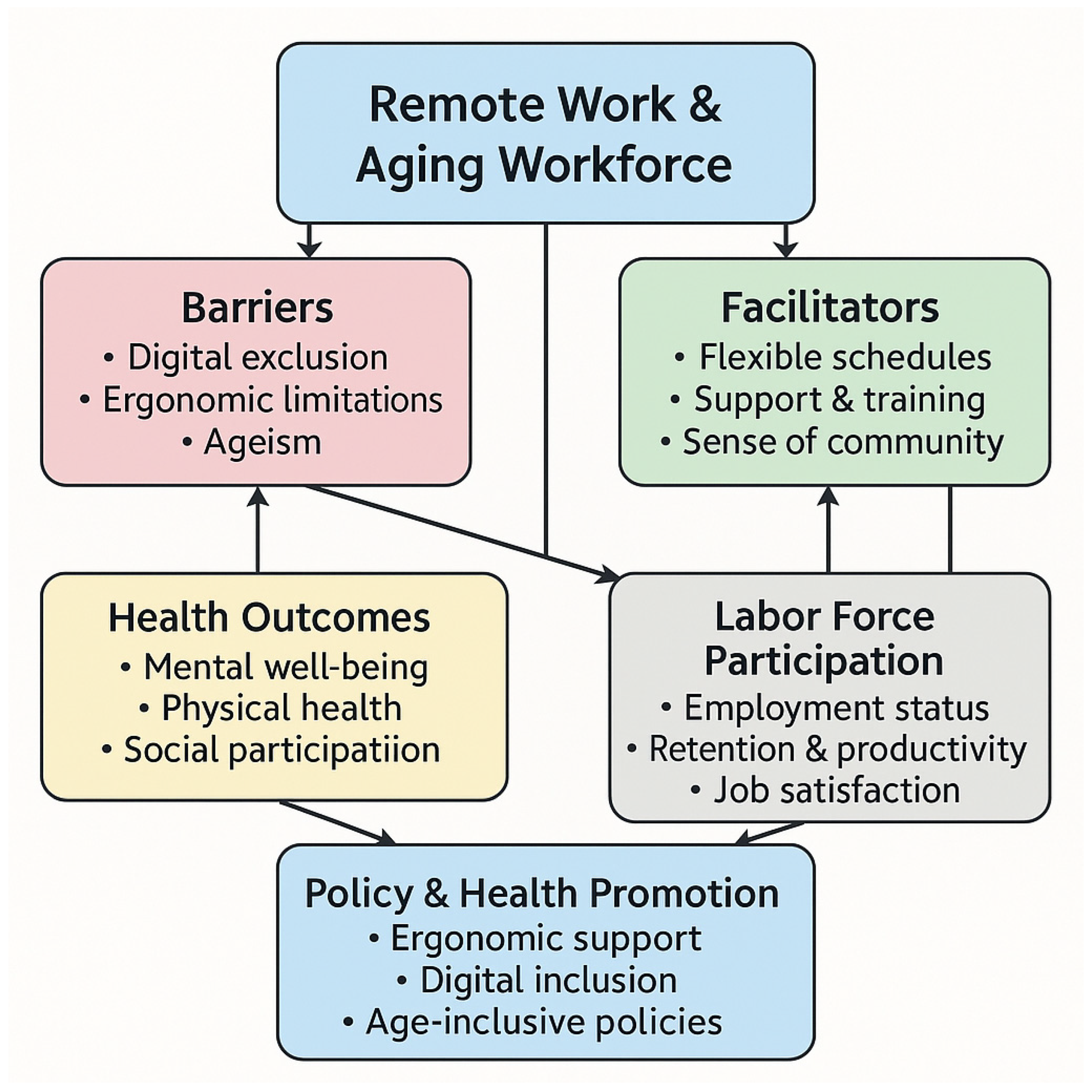

The conceptual framework in

Figure 1 illustrates the intersection of remote and hybrid work with aging, which impacts both health status and workforce participation. Remote work environments can create barriers, such as digital exclusion, ergonomic issues, and ageism, as well as facilitators, including adaptable schedules, supportive training, and social connectedness. These factors shape the mental, physical, and social health of older workers and their ongoing employment status. This framework highlights that policy intervention and health promotion can reduce barriers and enhance facilitators of healthy aging and continued workforce participation.

1.2. Rationale and Research Objectives

Although some studies have examined the experiences of older workers with teleworking, there is no consolidated evidence mapping the scope, barriers, and facilitators of remote working in this population. Inconsistent definitions, diverse national contexts, and sectoral variations further complicate the landscape.

To address this gap, the current scoping review aims to systematically map and synthesize interdisciplinary evidence on the relationship between remote work and labor force participation among adults aged 45 years and older. Specifically, it seeks the following.

Identifying barriers to and facilitators of remote work that influence older adults’ employment decisions and well-being.

Explore health promotion implications of remote work in the context of aging.

Inform policy and workplace interventions that support diverse, flexible, and inclusive labor markets.

This review is situated at the intersection of public health, labor economics, and gerontology, offering novel insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers committed to promoting healthy aging through equitable workforce participation.

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the methodological framework outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis [

11] and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

12]. This review also builds on advancements in the scoping review methodology, as described by Levac et al. [

13].

A comprehensive and reproducible search strategy was developed in collaboration with Marie T. Ascher, MS, MPH, Lillian Hetrick Huber Endowed Director, Phillip Capozzi, M.D. Library, and New York Medical College. She also provided technical support in setting up the Covidence and optimizing searches across seven databases.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The review followed the population–concept–context (PCC) framework, which is recommended for scoping reviews [

11].

Population: Adults aged 45 years and older. This age cutoff reflects the onset of midlife transitions and aligns with prior research on labor and aging, which emphasizes the importance of extended workforce participation.

Concept: Remote, hybrid, or flexible work arrangements (including telework, telecommuting, work from home, and virtual work).

Context: All countries, employment sectors, job types, and income settings.

Inclusion Criteria:

Studies published between January 2000 and May 2025.

Peer-reviewed or gray literature (e.g., reports, dissertations).

Any study design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods).

Studies reporting on labor force participation, employment outcomes, job satisfaction, well-being, health status, and workplace inclusion.

Exclusion Criteria:

Studies that do not report age-specific data or specify remote/flexible work contexts.

2.2. Search Strategy

Studies published between 2000 and 2025. This extended timeframe was chosen because of the limited availability of studies specifically addressing remote work among older adults, particularly in the early years of digital labor market transformations.

Seven major academic databases were searched:

MEDLINE (Ovid)

EMBASE

Scopus

CINAHL (EBSCOHost)

AgeLine (EBSCOHost)

PsycINFO (EBSCOHost)

EconLit

Searches combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), Emtree, and keyword terms related to aging, older workers, remote work, flexible work arrangements, and labor participation (see Appendix A for full strategies).

Boolean operators (AND, OR), truncation (*), and proximity operators (e.g., adj, NEAR, PRE/W) were used to enhance sensitivity.

The language used in this study is restricted to English. The search was supplemented by citation chaining and limited searches of the gray literature.

Search results:

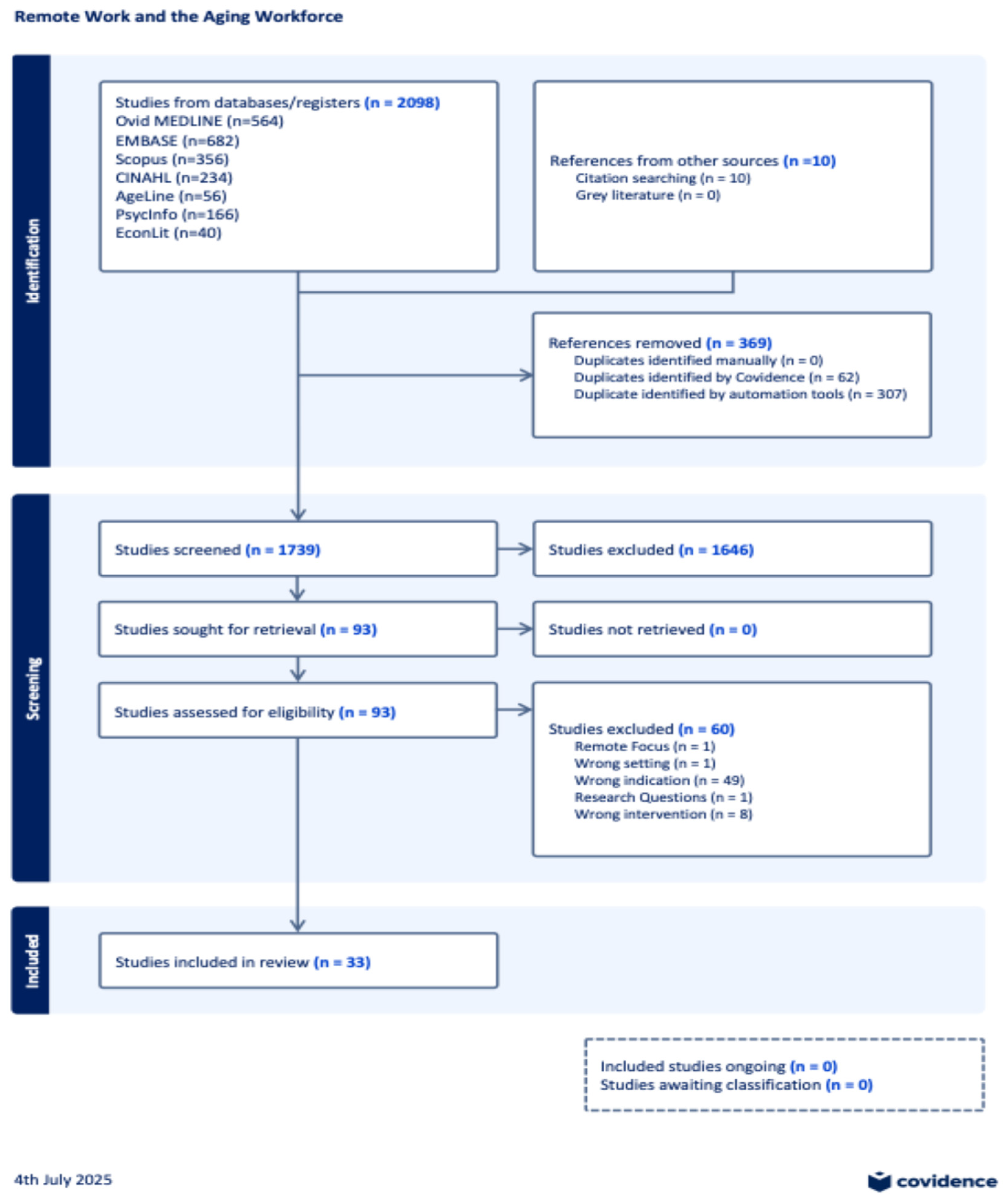

A comprehensive literature search yielded 2,108 records, including 2,098 from electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL, AgeLine, PsycINFO, and EconLit) and 10 from other sources identified through citation searching. After removing 369 duplicates identified through automation tools (n = 307) and Covidence software (n = 62), 1,739 unique records were screened at the title and abstract levels. Of these, 1,646 were excluded based on relevance, leaving 93 articles for the full-text assessment. Following eligibility screening, 60 full-text studies were excluded owing to incorrect indications (n = 45), intervention (n = 8), setting (n = 1), population focus (n = 1), or research question mismatch (n = 1). Ultimately, 33 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final review. The selection process is summarized in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (

Figure 2).

2.3. Study Selection Process

A three-step screening process was performed using Covidence:

Title and Abstract Screening: Three reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts.

Full-Text Review: Articles selected for full-text review were assessed for eligibility based on predefined criteria.

Discrepancy Resolution: Disagreements were resolved through discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer.

Reviewer Agreement and Discrepancies

In the Covidence screening and selection procedures, studies were reviewed independently by at least two reviewers. Discrepancies were identified in 116 of the 1,739 records during the title and abstract screening stage, representing approximately 6.7%. In the full-text review stage, 12 of 93 articles (12.9%) required discussion to reach a consensus. All disagreements were resolved through reviewer deliberation and, when an initial agreement was not reached, by consensus or referral to a third reviewer. These results indicate a high level of consensus, which enhances the reliability and transparency of the reviews.

2.4. Data Extraction and Charting

A standardized data charting form (Appendices B and C) was developed to extract the following variables systematically.

Bibliographic details (author, year, country)

Study design and method

Participant characteristics (age range, gender, job type)

Remote work arrangement (telework, hybrid, flexible, etc.)

Health or labor outcomes (e.g., well-being, inclusion, job satisfaction, retirement intentions)

Identified barriers and facilitators

Policy or practice implications

Data were extracted independently by multiple reviewers to ensure consistency and minimize bias (

Table 1). Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequency and percentage of thematic mentions) were calculated using

Stata 18 to quantify the presence of key themes across the included studies (

Figure 3).

2.5. Data Synthesis

The synthesis used a descriptive and thematic approach:

Quantitative summary: The studies were summarized according to year, country, sector, design, and type of remote work.

-

Thematic analysis: Key themes were derived related to:

- ○

Barriers (e.g., digital exclusion, ageism, ergonomic risks)

- ○

Facilitators (e.g., autonomy, training support, flexibility)

- ○

Health promotion outcomes (e.g., mental health, well-being, and social participation)

Themes were organized in alignment with health promotion frameworks such as the

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion [

9], which guided the interpretation of findings in terms of enabling environments, personal skills development, and supportive policies.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 2,108 records were identified through a systematic search of seven academic databases, followed by a citation chaining process. A total of 369 duplicates were excluded (automatically and by Covidence), and 1,739 records were shortlisted based on the title and abstract. A total of 1,646 records were excluded, and 93 articles were shortlisted for the full-text assessment. Finally, 33 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The selection process is presented in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (

Figure 2).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

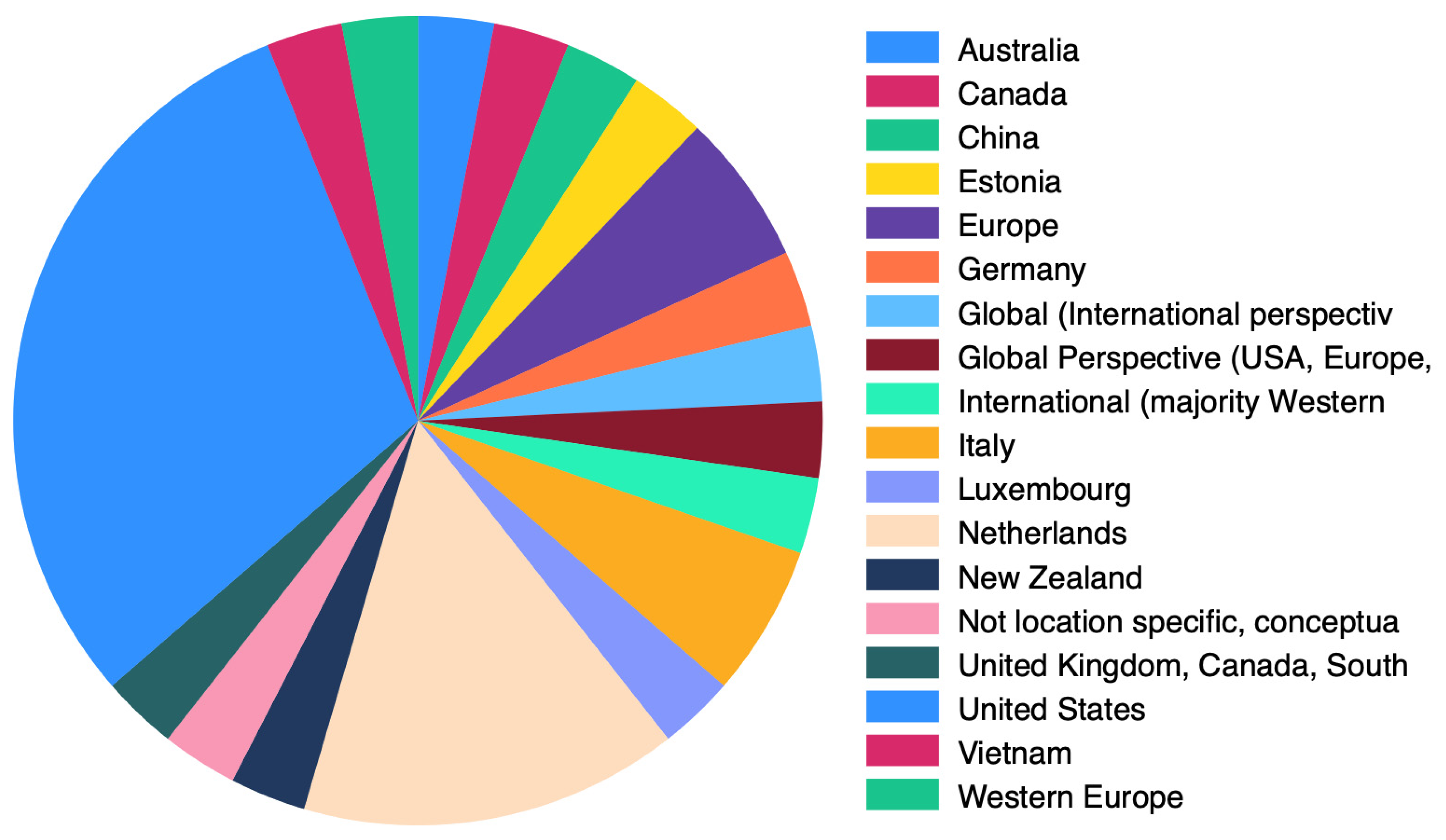

These 33 studies spanned different geographies and methodologies. The majority of participants were from high-income countries, with the majority originating from European or Australian countries (see

Figure 3 for a pie chart of the study locations). The method split was:

Among the 33 included studies, the methodological approaches were as follows:

Quantitative research: 15 studies

Qualitative research: 11 studies

Mixed-methods research: 3 studies

Conceptual or policy reviews: 3 studies

Systematic review: 1 study

This methodological diversity reflects a balanced representation of empirical, theoretical, and policy-oriented perspectives on remote work and aging.

The population samples primarily comprised individuals aged 45 years and above, with subgroups including caregivers, teaching and healthcare professionals, government servants, and geographic distribution of studies (

Figure 3). The remote work arrangements explored included fully remote, hybrid, and flexible options.

Figure 3: A pie chart illustrating the geographic distribution of study locations was generated using

Stata 18.

3.3. Theme Coverage Across Studies

The coder coded studies for four major thematic areas: facilitators, barriers, policy implications, and health and labor outcomes. Text-based records were coded, and any incidence of descriptive data in the theme column was treated as a mention. The blank rows were assumed to indicate a lack of thematic discourse.

Table 2 presents a quantitative summary.

Table 2: This table shows the percentage of studies (out of 33) that addressed each central theme. Barriers and facilitators were the most reported, followed closely by outcomes and policy implications.

Interpretation:

Barriers and facilitators were the most consistently prominent themes, appearing in more than 90% of studies. This suggests a strong orientation toward identifying the structure and individual-level challenges and enablers in remote work for older adults. While the results and policymaking implications were also quite common (approximately 85% of the studies), a small proportion of studies were conceptual or theoretical in nature and did not include actionable results or policy implications.

3.4. Barriers

Barriers to remote and flexible work among older adults are multifaceted. Digital exclusion and technological strain were the most cited obstacles, particularly among those with lower digital literacy or cognitive resilience [

16,

17]. Ageist stereotypes and one-size-fits-all HR practices often lead to the underutilization of older workers’ strengths and capacities [

18].

Additional barriers include high job demands, inadequate managerial support, and insufficient ergonomic infrastructure at home [

19,

20]. Limited perceived flexibility, especially among women and caregivers, is also notable [

21].

Below is a cross-study comparison (

Table 2) that summarizes the major barriers and facilitators reported across the 33 included studies. Each category was derived by grouping similar themes from the extraction data; the “Number of studies” column indicates how many studies mentioned each category (out of 33).

Table 3.

Barriers to Remote Work Among Older Adults.

Table 3.

Barriers to Remote Work Among Older Adults.

| Barrier Category |

Number of Studies (n = 33) |

Key Description |

| Digital exclusion/tech fatigue |

14 |

Limited digital skills, lack of access to devices or reliable internet, and ICT-related strain hamper participation. |

| Ageism/employer bias |

8 |

Stereotypes that older workers are less adaptable and lack technology skills, combined with a lack of age-friendly HR practices and support, contribute to this issue. |

| Health limitations / cognitive strain |

8 |

Poor health, chronic conditions, or age-related cognitive decline reduce the capacity to work remotely. |

| Ergonomic / home-work challenges |

2 |

Inadequate home workstations cause physical discomfort or musculoskeletal issues. |

| Organisational culture/role clarity |

3 |

High job demands, unclear roles, limited social support, and unsupportive work cultures can undermine the success of remote work. |

| Regulatory / policy barriers |

6 |

Legal or pension constraints hinder the adoption of phased retirement and formal telework, primarily due to the lack of national legislation or social insurance coverage for telework. |

Table 2: The most frequently reported barrier was digital exclusion, reflecting inadequate access to technology and skills among older adults. Ageism and employer bias were also common, indicating persistent stereotypes about older workers’ adaptability and a lack of supportive HR practices. Health limitations and cognitive strain, along with structural and policy constraints, further restricted older workers’ ability to engage in remote work.

3.5. Facilitators

Facilitators that enhance older adults’ participation in remote and flexible work include schedule autonomy and individualized work arrangements, such as “i-deals” [

14,

18]. Structured digital training programs, cognitive skill-building tools, and age-friendly technology interfaces have significantly improved usability and confidence among older workers [

15,

22,

23].

Psychosocial factors such as autonomy, organizational trust, and intergenerational knowledge sharing are also critical. Studies have emphasized that these factors enhance satisfaction and performance, particularly in remote settings with clear role expectations and access to mentorship [

19,

24,

25,

26].

Below is a cross-study comparison (

Table 4) that summarizes the major barriers and facilitators reported across the 33 included studies. Each category was derived by grouping similar themes from the extraction data; the “Number of studies” column indicates how many studies mentioned each category (out of 33).

Table 4: The most common facilitators were flexible scheduling and a strong sense of community at work, both of which enable older workers to balance personal needs with professional demands. Digital up-skilling programmes and personalized job arrangements (I-deals) help older adults overcome technology barriers and maintain engagement [

18]. Supportive organizational and policy environments, including phased retirement options, ergonomic adjustments, and inclusive leadership, also promote healthy and sustained participation in remote work.

3.6. Health Promotion-Relevant Findings

Remote work has a mixed effect on health, both positively and negatively, depending on the context. These benefits include reduced commuting stress and improved work satisfaction and mental health, particularly in situations with high autonomy and flexibility. However, social isolation, technostress, and screen fatigue have been observed in the absence of suitable digital support or social interactions among aging workers.

These findings are congruent with the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, which emphasizes the importance of creating conducive environments and promoting equity in skills and work design.

3.7. Labor Force Participation Impacts

Flexible and remote work arrangements were associated with delayed retirement, gradual withdrawal from full-time employment, and increased part-time participation among older workers. This study underpinned the following:

Flexible formats enhanced retention in highly knowledge-intensive and care-based professions.

Workers with chronic illness appreciate phased retirements and part-time employment.

High-income neighborhoods and public-sector institutions provided more flexible telework environments.

However, disparities have emerged for informally employed workers, particularly those in non-rural or internetless home-based settings, highlighting a significant gap in digital equity.

3.8. Policy and Practice Implications

Thematic analysis revealed strong consensus regarding the need for multi-level interventions:

Employer-Level: Inclusive HR practices, training, support for ergonomics, and flexible leadership models.

Policy-Level: Digital infrastructure investment, anti-ageism legislation, flexible retirement options, and expansion of social protection for teleworking.

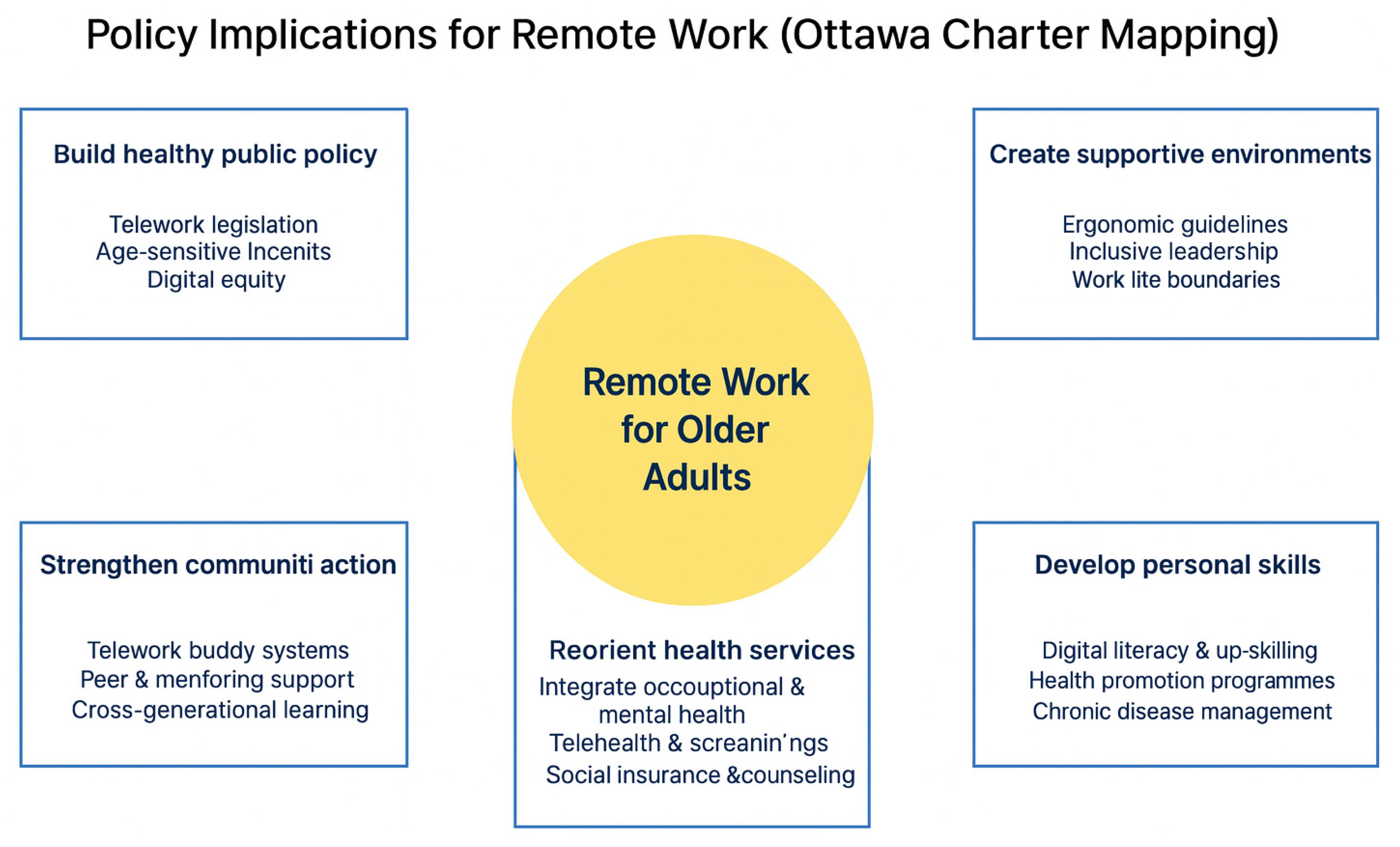

These strategies encompassed the five areas of action outlined in the Ottawa Charter (

Figure 3).

Figure 4. Policy Implications for Remote Work (Ottawa Charter Mapping). 4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

The scoping review revealed the dual nature of remote work as both an exclusionary barrier and an inclusionary enabler of workforce participation and health in older individuals. Telecommuting enables continued workforce participation by providing a more flexible and less physically demanding work environment. These relationships are beneficial for older workers with chronic illnesses, impairments, or care obligations [

14,

19,

24,

47]. Second, remote work institutionalizes exclusion by encouraging an information divide, weak support systems, and institutionalized ageism [

16,

17,

22,

30,

48].

Organizational readiness, technical infrastructure support, and a supportive work environment have been identified as definitive predictors of or against work-from-home arrangements, which either aid or tax ageing workers. The availability of individualized agreements (i-deals), technological and physical support, and age-inclusive HR practices makes a difference [

18,

23,

39,

45]. These findings suggest that the value of work-from-home arrangements depends on the support systems and the environmental infrastructure in place.

Apart from documenting the enablers and challenges, this review incorporates evidence in the following ways, which sheds light on the current debates about aging and post-pandemic labor markets. Remote work is not a coping mechanism but a transformative force. It can increase the labor supply, reduce healthcare costs, and preserve economic productivity. Older workers have stability, experience, and mentoring in increasingly fluid labor markets. It benefits GDP growth, reduces the pension burden, and promotes intergenerational equity in the labor force.

4.2. Health Promotion Implications

The evidence base aligns with the fundamentals of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, particularly in terms of developing a supportive environment, enabling individual skill building, and achieving health equity [

9]. Flexible telework reduces stress-provoking factors such as commuting, allows for autonomy, and promotes mental health [

19,

24,

27]. However, it is poorly managed in the workplace and exacerbates psychosocial stress, social isolation, and cognitive overload [

29,

30,

41].

The effect of teleworking on healthy aging depends on several factors. It can extend work lifespan, prevent early retirement, and promote inclusion when proper digital connectivity, safety ergonomics, and facilitating policies are in place. Such inferences align with the WHO’s Programme of the Decade of Healthy Ageing, which highlights the importance of enabling aged and elderly individuals to lead healthy and fulfilling lives through the support provided by systems [

2,

48].

Additionally, the combination of work ability and chronic diseases is particularly relevant. Unfavorable work, insufficient organizational support, and mental distress hurt work engagement and well-being in later life [

47]. Thus, health promotion planning should appropriately consider such occupational determinants.

4.3. Policy and Practice Relevance

Such outcomes require integrated frameworks that bridge the relationships between the work environment, occupational health promotion, productivity, and well-being. Life-course perspectives should inform such frameworks because older workers are not a homogeneous group, and individual pathways matter [

14,

38,

49,

50]. Policies must also be fair in nature, not excluding older workers in the informal economy, particularly in rural and poor sectors.

At the organizational level, ICT-enabled onboarding, mentoring, leadership through participation, and individualized work arrangements have been effective in aiding aging workers [

18,

23,

34,

40]. To eliminate constraints and create enabling environments at the policy level, reform of employment laws and ICT infrastructure is necessary [

42,

45,

46].

Italy provided a classic example: the OECD report highlighted the fragmented character of the disability evaluation systems, rendering them ineffective and leaving massive categories of intended beneficiaries unaddressed. Complementing the assessment of functions such as the WHODAS can promote inclusion and justice [

49]. The generalization of policy reforms based on functions is also postulated by the experience of this pilot study, which aims to promote sustainable employment and remote work for individuals with disabilities or age-related limitations. Digitalization presents opportunities and challenges for aged workers. On one level, it opens up the possibility of teleworking and flexible work arrangements outside the office, thereby prolonging working life. On another level, it presents demands in the form of ICT literacy, mental adaptability, and continuing support, and many older individuals will not be able to respond without such special interventions [

22,

28,

51]. When this happens, the risk increases that technology functions as a barrier rather than a facilitator of workforce inclusion.

Exclusion from the cyber world and limited access to IT are common challenges faced by older workers in teleworking situations. They are also often paired with age discrimination in organizations and mental burnout, specifically among IT professionals who experience chronic diseases [

52,

53].

In comparison, prominent enablers for long-term engagement in remote work were:

Adaptive scheduling and phased work retirements that account for individual capacity.

Vocational upskilling courses designed for senior learners.

Inclusive organizational cultures that embrace mentorship and support.

A strong sense of community and autonomy in remote environments [

54].

Based on this synthesis, several concrete policy recommendations emerge:

Employers and governments should prioritize digital inclusion by providing older workers with access to training, ergonomic tools, and reliable internet.

Anti-ageism efforts should be integrated into recruitment, promotion, and job-retention strategies.

Pension and retirement policies should evolve to accommodate remote, part-time, or hybrid work arrangements, without penalizing the income or benefits of older workers.

Employers should tailor job design and working conditions to support the physical and mental health of aging workers.

These results collectively underscore the need for integrated planning, whereby technological development and inclusive design align, and the longevity of the workforce is fostered rather than hindered by technological advancements.

4.4. Research Gaps

Significant research gaps were also identified. First, longitudinal studies on the long-term impact of working from home on the health and labor force participation of older individuals have not yet been conducted. Second, most studies are concentrated in Western high-income contexts; the experiences of older workers in the informal economies of low- and middle-income countries are not yet adequately represented [

15,

36]. Third, many studies have relied on indirect health outcomes, such as work engagement or satisfaction, rather than real health outcomes. This limits causal inferences and attenuates the links to models that promote health.

Furthermore, very few studies have been published regarding how intersectional characteristics such as gender, disability, and rurality affect older individuals’ work at a distance. Based on this literature review, we recommend the following for future research.

Utilize longitudinal and mixed-method designs to explore causality.

Expand regional coverage of low- and middle-income countries and informal employment sectors.

Examine the intersectionality of age with gender, race, disability, and rurality.

Examine how remote work can be effectively applied across various occupational and policy settings.

These steps will strengthen the evidence base and make remote work policies and practices more inclusive and equitable.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

The addition of research post-2000 allows for a more comprehensive literature on older workers and telecommuting/home work. Although the larger timespan expands the coverage of the review detrimentally by introducing variability by definition and compromising appropriateness for context due to changing technologies and work patterns, in the review’s favor are its broad reach, interdisciplinary methodology, and diligent approach grounded in the JBI and PRISMA-ScR protocols [

11,

12,

13]. It combines both the conceptual and empirical literature, providing a comprehensive overview of the implications of teleworking for older workers across various domains. However, this research was restricted in several ways. Following scoping methodological guidance, no individual study quality appraisal was performed; however, this restricted the possibility of determining the strength of evidence. The study design and heterogeneity of the populations render comparisons problematic. In addition, several studies did not directly assess health outcomes but instead inferred associations through work-related intermediaries.

5. Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the importance of redefining flexible work at a distance as a long-term strategy for promoting healthy, inclusive, and productive aging in the workplace. Analyzing the findings of 33 studies from high-income and global contexts, this review shows that flexible and remote work arrangements are auspicious for increasing workforce participation among older workers. These arrangements enhance autonomy, reduce physical stress, and promote work-life balance, which are particularly important for aging workers who manage chronic illnesses or caregiving responsibilities.

However, these benefits are not automatic. Without conscious investment in digital infrastructure, age-friendly technologies, and workplace strategies for aging workforces, remote work can solidify exclusion, deepen digitally led divisions, and widen inequities, particularly for low-digitally capable workers, informal or non-contract workers, or those subjected to overlapping disadvantages such as disability, rurality, or low wages.

This report highlights that teleworking is not a neutral phenomenon. The environment around them mediates the health and engagement of older workers, including access to technology, work-life balance at the workplace, leadership mindset, and overall policy climates. Ageist beliefs, insufficient investments in training opportunities, inflexible benefits, and pension arrangements continue to be significant hurdles. Therefore, employers and policymakers need to take proactive measures that benefit teleworking rather than exacerbating the existing differences.

Specific initiatives include providing specialist digital literacy training, subsidizing equipment or connectivity, updating workplace policies to combat age discrimination, and accommodating differentiated requirements. Policymakers can also address reforms in pension arrangements, employment protection, and social care provision, which now act as disincentives for flexible later-life work.

From an economic perspective, enabling older citizens to remain in the workforce in remote or hybrid formats makes the workforce more resilient, reduces healthcare burden, and creates a deep pool of experience and expertise. Enabling such inclusion benefits national productivity and aligns with the public health agenda under the WHO Decade of Healthy Aging and Ottawa Charter. This review also revealed significant gaps in the literature. The long-term employment and health effects of remote work on older workers necessitate immediate longitudinal research. Low- and middle-income countries, informal economies, and understudied populations also require more evidence, such as studies that utilize intersectional strategies to explore how gender, disability, and place shape outcomes.

Briefly, teleworking holds transformative potential for aging populations only if it is planned and regulated by fair, evidence-based, and equity-oriented strategies. For employers, policy developers, and researchers alike, this is a responsibility and opportunity to reimagine the future in a way that fosters dignity, health, and economic security across the life course.

Plain Language Summary

Helping Older Adults Thrive in Remote Work

Why was this review conducted? An increasing number of older adults continue to remain in the workforce, and remote work has become more prevalent, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. Working from home can help older individuals stay employed longer by offering flexible schedules and less commuting time. However, this can also be challenging if someone lacks the necessary digital skills or tools or faces unfair treatment due to their age.

What did we look at?

We reviewed research from the past 25 years (2000–2025) to understand how remote and flexible work affects people aged 45 and above. We wanted to learn what makes remote work easier or harder for them and how policies and workplace support can help.

What did we find?

Remote work has both advantages and disadvantages for older workers.

Good things:

Flexible hours make it easier to balance work and life

Avoiding lengthy commutes can lower stress

Some older adults feel more independent when working remotely

Challenges:

Not everyone has the digital skills or equipment they need

Poor home office setups can lead to health issues

Some workplaces may not be welcoming to older workers

We also found that programs such as digital training, improved work tools, and supportive policies (e.g., phased retirement or mentoring) can be beneficial.

Why is this important?

As the population ages, older adults can continue working if they choose to support both economic productivity and healthy ageing. Remote work options help maintain independence, reduce pension strain, and harness valuable experience.

Making remote work more accessible and supportive for older people helps everyone, boosts the economy, promotes health, and supports fairness.

This summary is intended to help the general public, older adults, and non-expert readers understand the key findings and importance of the study.

Access Information:

Registration Type: Open-Ended Registration

Date Registered: September 13, 2025

Publication DOI: Not applicable at this stage

Additional Note:

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. All supplementary files and documentation related to this scoping review have been archived and made openly accessible via the Open Science Framework (OSF).

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, K.A.K. and M.G.; methodology, T.K. and M.S.; validation, K.A., T.K., and M.G.; formal analysis, M.S. and T.K.; investigation, M.S., T.K., and K.A.; data curation, K.A., M.S., and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.; writing—review and editing, M.G., K.A.K., T.K., and M.S.; visualization, M.S. and A.M.; supervision, K.A.K. and M.G.; project administration, K.A.; Funding Acquisition, M.G. and K.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Kola Adegoke, Temitope Kayode, and Mallika Singh contributed equally and shared first authorship. Michael Gusmano, PhD; Kenneth A. Knapp, PhD; and Abbie Montgomery contributed equally to this work.

Funding

No external funding was received for the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and no new data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Written Informed Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing was not performed in this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marie T. Ascher, MS, MPH, and Lillian Hetrick Huber, Endowed Director at the Phillip Capozzi, M.D. Library, for her expert assistance in developing the literature search strategy. We also thank Rosa O. Rodriguez, a DrPH student at New York Medical College, for her thoughtful review and constructive suggestions, which helped improve the quality and clarity of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement

The Authors have no affiliation with or financial involvement in any institution or body that may have a financial interest in the topics or materials presented in this manuscript.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd-2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Eurofound; International Labour Office. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2017/working-anytime-anywhere-the-effects-on-the-world-of-work (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19; 2021. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2021/living-working-and-covid-19-update-april-2021-mental-health-and-trust-decline (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Seifert, A.; Cotten, S.R.; Xie, B. A double burden of exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e99–e103. [CrossRef]

- Van der Lippe, T.; Lippényi, Z. Co-workers working from home and individual and team performance. New Technol. Work Employ. 2020, 35, 60–79. [CrossRef]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, L.; Butakhieo, N. The impact of working from home during COVID-19 on work and life domains: an exploratory study on Hong Kong. Policy Des. Pract. 2021, 4, 59–76. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ottawa-charter-for-health-promotion (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Keating, N. A research framework for the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030). Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 775–787. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: 2020; pp. 406–451. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, K.G.; Hershbein, B.; Houseman, S.N. Contract work at older ages. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2021, 20, 426–447. [CrossRef]

- Andreassi, S.; Monaco, S.; Salvatore, S.; et al. To Work or Not to Work, That Is the Question: The Psychological Impact of the First COVID-19 Lockdown. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1754. [CrossRef]

- Arvola, R.; Tint, P.; Kristjuhan, Ü.; Siirak, V. Impact of telework on the perceived work environment of older workers. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2017, 64, 199–214. [CrossRef]

- Beekman, E.M.; van Hooff, M.M.L.; Adiasto, K.; et al. IS THIS (TELE)WORKING? Work 2025, 80, 295–313. [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; Jansen, P.G.W. Idiosyncratic deals for older workers. In Aging Workers and the Employee-Employer Relationship; Bal, P.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 129–144. [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, I.; Ferrara, B.; Pansini, M.; Benevene, P. Job Satisfaction and Perceived Structural Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6205. [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Sharit, J. Aging and Work: Issues and Implications in a Changing Landscape; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 1–320.

- Damman, M.; Henkens, K. Gender differences in workplace flexibility among older workers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 915–921. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A.; Cotten, S.R.; Xie, B. A double burden of exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e99–e103. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, K. Future work skills for older workers. Gerontechnology 2024, 23, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Dropkin, J.; Moline, J.; Kim, H.; Gold, JE Blended work as a bridge between employment and retirement. New Solut. 2021, 30, 270–282. [CrossRef]

- Fechter, C. Health and flexible working arrangements in Germany. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 53, 334–339. [CrossRef]

- Francis-Levin, J.; et al. Experiences and contexts of remote work across age groups. Opp: Work, Leisure & Social Participation 2023. [CrossRef]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.K.L.; Gardiner, E. Supporting older workers to work: A systematic review. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1318–1335. [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, S.; Parent-Lamarche, A. Teleworkers’ job performance and age. J. Organ. Eff. 2023, 10, 293–311. [CrossRef]

- Hauret, L.; Martin, L.; Poussing, N. Teleworkers’ digital up-skilling. Inf. Soc. 2024, 40, 215–231. [CrossRef]

- Koreshi, S.Y.; Alpass, F. Flexible work arrangements among older caregivers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1045–1055. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.W. Phased Retirement and Workplace Flexibility. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 638, 68–85. [CrossRef]

- Patrickson, M. Teleworking: potential employment for older workers? Int. J. Manpow. 2002, 23, 704–715. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chaudhuri, S.; Johnson, K.R. Engaging new hires in remote environments. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.Y.; Ginn, M.; Meares, W.L.; Hatcher, W. Telework in the U.S. federal government. Public Adm. Q. 2024, 48, 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Trieu, T.P.; Sukontamarn, P. COVID-19 and employment of older workers in Vietnam. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, S.; Retzlaff, L.; Hommelhoff, S.; Schmitt, A. Age-related differences in the use of boundary management tactics when teleworking: Implications for productivity and work-life balance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 1330–1352. [CrossRef]

- Oude Mulders, J.; Henkens, K.; van Dalen, H.P. How Do Employers Respond to Aging Workforce? In Trends in Aging and Work; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Pandemic-Induced Telework Divide in Federal Workforce. Public Pers. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; et al. Flexible work arrangements and health. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 40–58. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xie, H. Intelligent tech use & health of older teleworkers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Spoladore, D.; Trombetta, A. Ambient Assisted Working for Aging Workforce. Electronics 2023, 12, 101. [CrossRef]

- Foster-Thompson, L.; Mayhorn, C.B. Aging Workers and Technology. In The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging; Hedge, J.W., Borman, W.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [CrossRef]

- The Gerontologist. Health-related limitations and flexible work. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 450–459. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, J. Successful aging at work in digital workplaces. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 1475–1501. [CrossRef]

- Wissemann, M.; Pit, S.; Serafin, P.; Gebhardt, H. Strategic Guidance and Technological Solutions for Human Resources Management to Sustain an Aging Workforce: Review of International Standards, Research, and Use Cases. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 9, e27250. [CrossRef]

- Koolhaas, W.; van der Klink, J.J.; de Boer, M.R.; Groothoff, J.W.; Brouwer, S. Chronic health conditions and work ability in the ageing workforce: the impact of work conditions, psychosocial factors and perceived health. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2014, 87, 433–443. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: A practical guide; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/future-of-work/publications/WCMS_751232/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- OECD. Disability, Work and Inclusion in Italy: Better Assessment for Better Support; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Komp-Leukkunen, K. A Life-Course Perspective on Older Workers in Workplaces Undergoing Transformative Digitalization. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1413–1418. [CrossRef]

- Piroșcă, G.I.; Șerban-Oprescu, G.L.; Badea, L.; Stanef-Puică, M.-R.; Valdebenito, C.R. Digitalization and Labor Market—A Perspective within the Framework of Pandemic Crisis. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2843–2857. [CrossRef]

- Money, A.; et al. Barriers to and Facilitators of Older People’s Engagement With Web-Based Services: Qualitative Study of Adults Aged >75 Years. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e46522. [CrossRef]

- Sharit, J.; Czaja, S.J.; Hernandez, M.A.; Nair, S.N. The Employability of Older Workers as Teleworkers: An Appraisal of Issues and an Empirical Study. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2009, 19, 457–477. [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. The rise in remote work since the pandemic and its impact on productivity. Beyond the Numbers 2024, 13, 1–4. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-13/remote-work-productivity.htm (accessed on 15 August 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).