1. Introduction

Autonomous laboratories represent a significant development in modern materials science. These systems integrate machine learning, robotic synthesis, and in situ characterization to create closed-loop research environments. By combining active learning algorithms with multilevel datasets from quantum-mechanical simulations to high-throughput flow experiments, they establish real-time theory-experiment frameworks capable of guiding complex nanofabrication processes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The field addresses fundamental challenges in traditional materials discovery [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Conventional approaches often involve slow, sequential experimentation with high resource consumption and limited exploration of complex parameter spaces. The interpretation of high-dimensional data from advanced characterization techniques presents additional difficulties [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Data fragmentation across proprietary formats and incompatible systems further hinders scientific progress and reproducibility [

23].

AI-driven platforms significantly reduce material and energy requirements while enabling precise engineering of nanostructures with tailored functionalities. They facilitate research directions previously considered impractical, particularly for metastable phases [

19] and reactions with narrow processing windows. These systems automate the entire research cycle from hypothesis generation and experimental design to execution and analysis, enabling autonomous selection of subsequent experiments without human intervention [

1,

8,

10].

This review examines the current state of self-driving laboratories through several key aspects. We analyze architectural principles and algorithmic strategies, including Bayesian optimization [

8,

16], reinforcement learning, and generative models for inverse design [

20,

22]. Particular attention is given to automated methods for processing scientific literature [

12,

21]. We evaluate demonstrated capabilities across diverse material systems, covering perovskite nanostructures for optoelectronics [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], drug delivery nanoparticles [

34], and quantum dots with controlled emission profiles [

7,

15]. The assessment includes performance benchmarking and comparative analysis of different platforms.

Critical examination addresses persistent challenges such as data standardization issues [

23], limited data availability in unexplored chemical domains, model interpretability needs for high-stakes applications [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], and cybersecurity concerns [

25]. The discussion extends to future development pathways including accessible virtual laboratories [

29], multi-agent architectures [

3], and integration with industrial-scale manufacturing [

26]. Recent advances through platforms like A-Lab [

11,

12], AlphaFlow [

8], and Rainbow [

30] demonstrate the transition from proof-of-concept demonstrations to functional research systems. These developments highlight the potential for rapid progression from initial hypotheses to practical implementations. The following sections provide detailed analysis of these advancements, current limitations, and future directions for autonomous materials discovery.

3. Advances in Autonomous Laboratory Architectures

Over the past decade, artificial intelligence has shifted from a supporting instrument for data analysis to a primary engine of progress in materials science and nanotechnology when paired with autonomous laboratories [

1,

2,

3,

4], a transition reflected in SDLs that assemble robotic synthesis modules, versatile in situ characterization systems, and machine learning algorithms spanning generative models, Bayesian optimization, and reinforcement learning [

5,

6,

7]. A key advantage of these platforms is the closed-loop workflow that enables automated hypothesis generation, experimental design, synthesis, data acquisition and analysis, and the selection of the next experiment without human intervention [

8,

9,

10], which shortens research cycles while improving reproducibility and overall data quality. A representative case is the A-Lab platform at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which achieved the first fully autonomous solid-state synthesis of inorganic compounds [

11] by combining large-scale literature mining with outputs from density functional theory to plan synthesis steps, operate robotic dispensers and furnaces, and analyze powder diffraction data in real time using machine learning models [

12,

13,

14]; this integration allows discovery of previously unknown phases within days rather than weeks or months and has already been applied to the synthesis of complex oxides with promising thermoelectric performance [

12].

Progress in SDLs increasingly relies on the incorporation of flow chemistry, since flow reactors offer continuous control over composition and conditions, expand operational flexibility, and markedly increase the density of experimental data [

7,

8,

14]. Work by Delgado-Licona and colleagues [

15] showed that dynamic flow conditions in autonomous quantum dot synthesis expanded the volume of usable data by more than an order of magnitude and enabled rapid identification of conditions that deliver targeted size distributions and spectral properties, while the AlphaFlow platform integrates microfluidic channels with Bayesian optimization and active learning to support multistep reactions with precise parameter control at each stage [

16].

Advances in SDLs also depend on the deep integration of in situ and in operando methods, since machine learning control of X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and absorption spectroscopy can target the most informative spectral or angular regions, thereby reducing total experiment time and instrument load [

17,

18], and since the real-time theory-experiment loop implemented by Liang and co-authors [

19] updates reaction parameters directly from synthesis outcomes without human intervention, a capability that is particularly important for metastable nanophases and reactions with narrow parameter ranges. Interest in generative models for inverse design continues to grow because researchers can specify target properties such as band gap or absorption coefficient and then evaluate structures proposed by the model as likely to meet those targets, as demonstrated by the Generative Toolkit for Scientific Discovery (GT4SD), an extensible open-source library for organic materials design with experimental validation [

20], by a comprehensive perspective on foundational modeling that spans property prediction to molecular generation [

21], and by MatterGen, a diffusion-based generative framework for inorganic materials that led to synthesis of a generated structure with properties within 20 percent of the target [

22].

Despite rapid progress, several obstacles continue to limit broader adoption, with the absence of widely accepted standards for data visualization and exchange ranking among the most consequential because laboratories often maintain incompatible formats that complicate the integration of simulators, robotic systems, and AI modules; for example, XRD data stored in a proprietary format may require manual conversion before any machine learning agent in another laboratory can read it, which introduces delays and potential errors. The MGI workshop report [

23] therefore calls for standardized data formats and APIs and for digital infrastructure that ensures interoperability across platforms. A further limitation arises from the scarcity of large training datasets for emerging material systems, which pushes machine learning into data-poor regimes and constrains predictive power in unexplored chemical spaces, while explainability remains a concern because decisions without transparent rationales face barriers in domains demanding strict validation such as pharmaceuticals or nuclear energy [

24]. Cybersecurity risks add another layer of difficulty because SDLs are networked and thus exposed to disruption and data breaches, including threats to intellectual property [

25,

26,

27,

28], and these issues are intertwined since the lack of data standards makes explainability and robust cybersecurity more difficult to achieve.

To address these challenges, researchers are turning to new paradigms that aim to make SDLs more scalable, interoperable, and economically feasible. One promising direction is the emergence of so-called “frugal twins,” simplified digital replicas of laboratory environments that allow researchers to pre-optimize synthesis pathways and experimental workflows in a virtual setting before committing resources to costly robotic experiments. These lightweight digital twins, which can be implemented in cloud infrastructures, have been shown to accelerate design-make-test cycles while simultaneously lowering entry barriers for institutions with limited access to advanced robotics, thus making autonomous experimentation more democratized [

2,

4,

26]. However, because frugal twins rely on simplified digital models, the predictive reliability and robustness of such surrogates still require further validation before broad adoption [

2,

4]. Importantly, the concept of frugal twins extends beyond mere cost reduction, where they create opportunities for running large sets of “what-if” experiments in silico, using machine learning surrogates and coarse-grained models to filter out suboptimal conditions before physical testing begins. In recent demonstrations, frugal twins were coupled to cloud laboratories, enabling dozens of geographically dispersed research groups to replicate identical experiments with minimal variation (

Figure 1), effectively building a distributed ecosystem of SDLs working on harmonized protocols [

29].

Such integration of digital twins and real-time experimentation not only facilitates reproducibility but also strengthens the long-term goal of open science, where data and methods can be seamlessly shared and verified across laboratories worldwide. The ability to replicate conditions virtually also helps address issues of safety and sustainability: potentially hazardous chemical routes can first be evaluated computationally, reducing unnecessary exposure to toxic reagents, while simultaneously optimizing the use of scarce or expensive precursors. These features position frugal twins as indispensable in the democratization and scaling of autonomous materials discovery, bridging the gap between theory-driven modeling and real laboratory practice.

The issue of scalability is also being addressed through the design of multi-robot self-driving laboratories, among which the Rainbow platform represents a representative example. Rainbow is distinguished by its modular and parallelized architecture, integrating multiple robotic arms, liquid handling modules, and photonic characterization systems, all coordinated by a central machine learning controller [

5,

6,

7,

10]. Unlike earlier single-arm SDLs that performed sequential optimization, Rainbow can execute combinatorial parameter sweeps in parallel, thereby exploring much larger regions of chemical space in the same timeframe. Its implementation of real-time photoluminescence (PL) monitoring allows the system to detect and respond to subtle changes in perovskite nanocrystal emission profiles, thereby guiding the optimization process with both speed and accuracy. Benchmarking studies revealed that Rainbow identified optimal perovskite nanocrystal compositions in a fraction of the time needed by conventional SDLs, with significantly reduced experimental noise [

10,

30]. This demonstrates Rainbow’s high-throughput discovery potential and serves as a proof-of-concept for the next generation of autonomous laboratories where parallelization, adaptability, and modularity are standard features (

Figure 2).

A close examination of Rainbow’s performance metrics shows that error bars in measured photoluminescence quantum yields narrowed with successive closed-loop iterations, indicating an intrinsic capacity for self-correction and noise suppression. The figure illustrates a substantial reduction in variance across parallel reactors as the system converges toward optimal synthesis conditions, underscoring the robustness of multi-robotic workflows for reproducible nanomaterial discovery. In addition, Rainbow’s architecture points to the feasibility of scaling SDLs toward industrially relevant throughputs, where hundreds of compositions could be synthesized and characterized per day, feeding into machine learning models that progressively refine their predictive accuracy. This represents a concrete step toward bridging laboratory-scale demonstrations and pilot-scale manufacturing, a longstanding challenge in translational materials research.

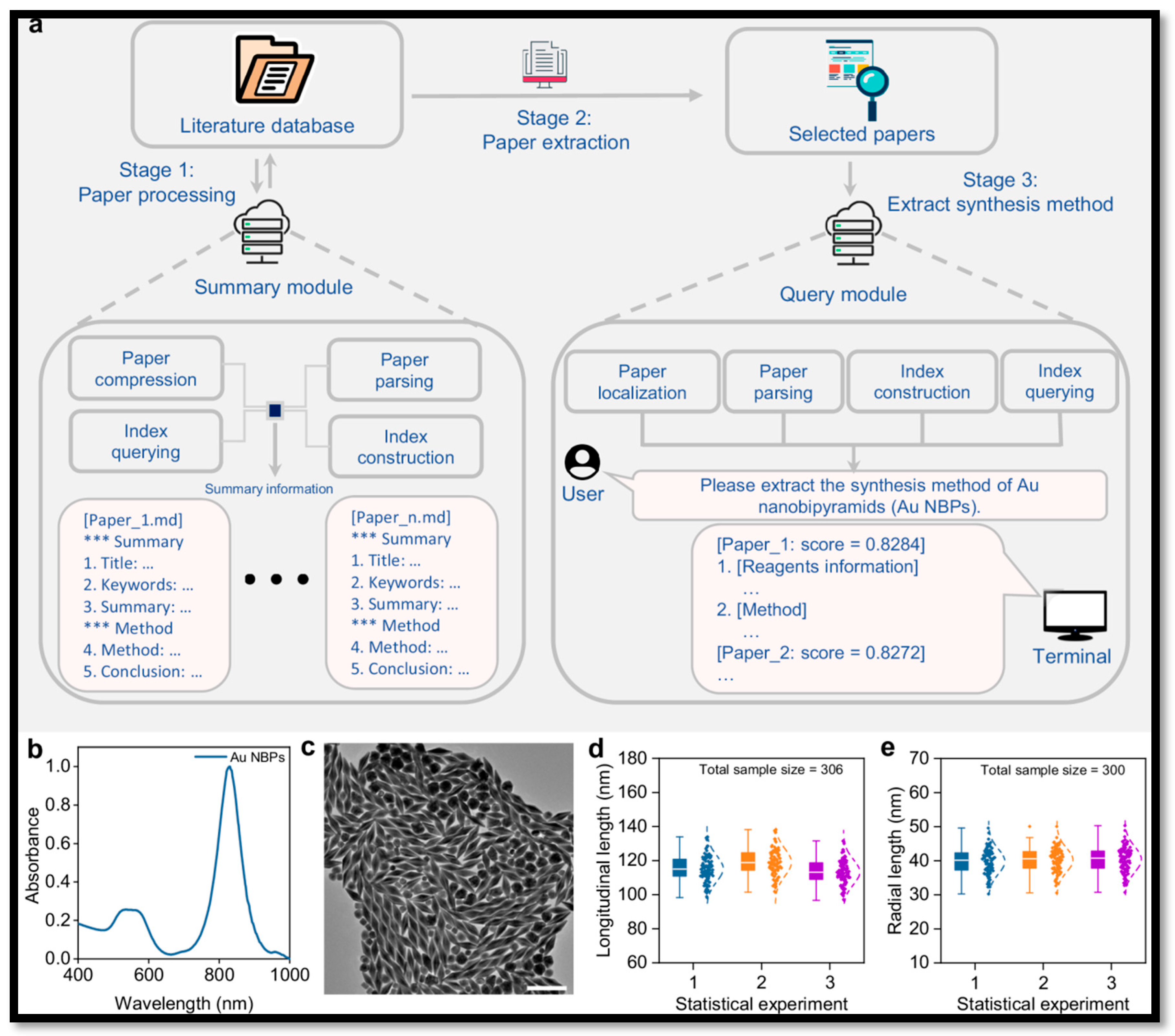

Another critical advancement is the integration of natural language processing and algorithmic planning frameworks with autonomous laboratories. A recent study introduced a platform that combines automated literature analysis with the A* path-finding algorithm for the synthesis of gold nanorods (Au-NRs). The system was capable of scanning thousands of synthesis protocols in the literature, extracting relevant parameters, and building a knowledge base that guided robotic synthesis experiments [

12,

20,

21,

31]. By employing A* as the optimization engine, the platform systematically refined experimental parameters such as surfactant concentration, temperature profiles, and seed-to-precursor ratios. Notably, the system achieved highly reproducible nanorod synthesis with fine-tuned aspect ratios (

Figure 3), resulting in sharp UV–vis absorption bands with linewidths narrowed below 3 nm after a few optimization cycles [

31]. This example illustrates an ongoing shift and SDLs are no longer isolated automation platforms but increasingly incorporate text-processing algorithms as knowledge modules that bridge scientific literature and laboratory practice. In doing so, they reduce the information bottleneck between human knowledge and robotic action, effectively converting text-based knowledge into actionable experimental instructions. The implications of this development are significant, as it opens the possibility of automated “literature-to-lab” pipelines where AI continuously digests the scientific corpus, identifies promising synthesis strategies, and validates them experimentally with minimal human intervention [

20,

21]. This ability to learn from both structured datasets and unstructured textual information has the potential to become a cornerstone of next-generation SDLs.

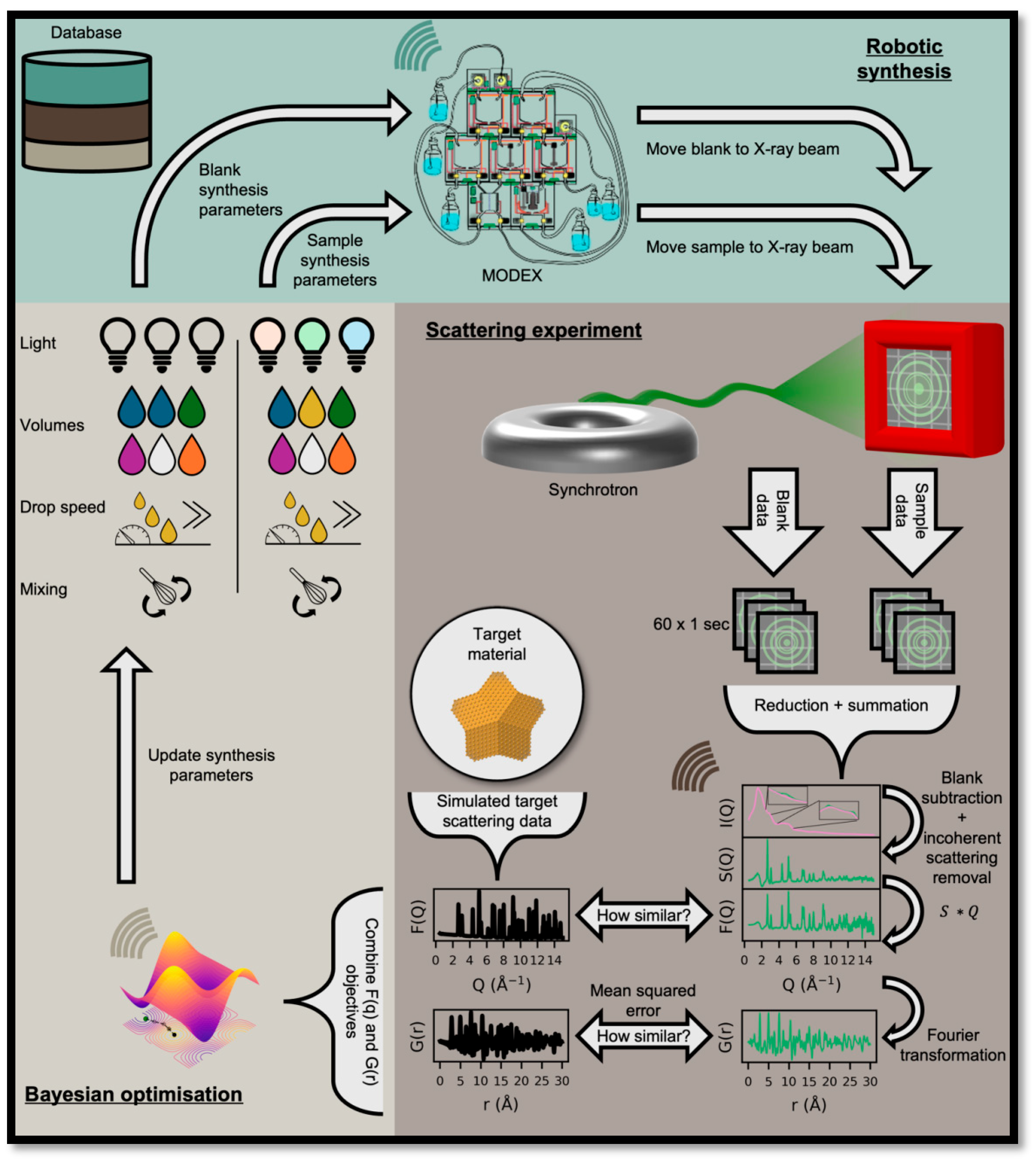

In parallel, structural characterization is evolving through approaches such as ScatterLab, which leverages total scattering and pair distribution function (PDF) data as direct input for inverse design loops [

17,

18,

19]. Traditionally, structure determination in materials science has been limited by the need for predefined structural models, but ScatterLab bypasses this constraint by using machine learning to map experimental scattering data directly onto atomic configurations. In recent demonstrations, the system autonomously guided the synthesis of gold nanoparticles with desired structural motifs, selecting reaction pathways that maximized agreement between in situ scattering signals and target PDF features. The graphical representation (

Figure 4) illustrates how iterative refinement of synthesis parameters rapidly converged toward the correct structural arrangement, even in the absence of human-supplied crystallographic models [

17,

18,

19,

32]. This capability is particularly significant for nanostructures and metastable phases where structural disorder obscures conventional diffraction patterns. By integrating scattering data into closed-loop experimentation, ScatterLab demonstrates the potential of SDLs to not only optimize macroscopic properties such as band gaps or catalytic activity but also directly engineer atomic-level arrangements in real time. The interpretation of the figure reveals that as the feedback loop progresses, misfit values between experimental and simulated PDFs decline sharply, providing a quantitative metric of convergence and improving transparency in discovery efficiency.

Complementary to these technological advances, multi-agent architectures such as MAPPS (Materials Agent unifying Planning, Physics, and Scientists) highlight the growing importance of modular AI ecosystems in autonomous experimentation [

3,

16,

24]. MAPPS unifies planning agents, physics-based simulators, and human-in-the-loop feedback modules into a coherent framework, thereby achieving resilience against errors and improving novelty in material proposals. Benchmarking against earlier LLM-based platforms showed that MAPPS improved stability of closed-loop experiments by a factor of five, while also expanding the diversity of candidate materials considered. Unlike single-agent models that often gravitate toward local optima, MAPPS encourages exploration of broader design spaces, mitigating the risks of premature convergence. The system has been demonstrated in case studies involving battery electrolytes and optoelectronic polymers, where the combination of simulation-driven priors and experimental validation led to the identification of previously untested but synthetically accessible candidates. Such multi-agent frameworks could represent a future pathway for SDL design, where a network of specialized AI agents collaborates with robotic hardware and human scientists to deliver balanced, interpretable, and reproducible discoveries.

To synthesize these developments, comparative analyses have begun to map the rapidly diversifying SDL ecosystem. A tabular summary of recent platforms contrasts Rainbow, GPT+A*, ScatterLab, AlphaFlow, and frugal twins in terms of architectural principles, targeted material systems, and demonstrated performance (

Table 1). From this comparison, two trends emerge clearly: first, SDLs are moving toward ever-greater levels of integration, combining robotic modules, real-time characterization, and cognitive engines in a single workflow; second, reproducibility and interpretability are becoming as important as speed and throughput, reflecting the community’s recognition that scientific trust depends on transparent and verifiable decision-making processes. The analysis presented in this review directly reflects these emerging trends. The discussion of Rainbow’s architecture highlights the potential of parallelization, the GPT+A* schematics illustrate the fusion of literature and laboratory, ScatterLab’s convergence trajectories exemplify atomic-level structural control, and frugal twin frameworks emphasize the democratization and accessibility of autonomous experimentation. Taken together, these cases demonstrate that the evolution of SDLs is no longer determined by hardware or algorithms in isolation but by the holistic integration of digital infrastructure, robotic capability, AI cognition, and human oversight. This synthesis points toward a future in which autonomous discovery becomes not only faster but also more collaborative, interpretable, and impactful for the broader scientific enterprise.

In summary, the evolution of SDLs is advancing along two primary tracks: first, toward greater hardware integration and parallelization to drastically increase experimental throughput, and second, toward deeper cognitive capabilities that incorporate prior knowledge and reason across complex constraints. Platforms like Rainbow and multi-agent architectures such as MAPPS exemplify these trends, highlighting a shift from isolated automation to holistic, AI-driven discovery systems. However, truly autonomous discovery will remain elusive until the field satisfactorily addresses the intertwined fundamental challenges of data standardization, model explainability, and robust cybersecurity. Overcoming these hurdles is essential to transition from proof-of-concept demonstrations to reliable, scalable, and democratized SDLs that can fully bridge the gap between laboratory-scale innovation and industrial-scale manufacturing.

4. Conclusions

The development of self-driving laboratories represents an important step in the evolution of materials science, transitioning from traditional, sequential experimentation to autonomous, AI-driven discovery. This review has outlined the rapid evolution of SDLs, highlighting key architectural innovations such as the multi-robot parallelization exemplified by Rainbow [

30], the integration of flow chemistry and Bayesian optimization in platforms like AlphaFlow [

8], and the cognitive capabilities introduced by LLM-based literature mining and algorithmic planning [

12,

21,

31]. Despite significant progress, the path toward fully autonomous discovery faces several interconnected challenges. The absence of standardized data formats and protocols continues to hinder interoperability and reproducibility [

23]. The "black box" nature of complex AI models requires advances in explainable AI (XAI) to build trust and facilitate adoption in high-stakes applications such as pharmaceuticals [

24]. Additionally, cybersecurity risks present growing concerns as these networked systems become more prevalent [

25]. Looking forward, the convergence of several technological trends points toward a transformative future for materials research. The development of "frugal twins" and cloud-based laboratories promises to democratize access to autonomous experimentation [

29], while multi-agent architectures like MAPPS enhance robustness, exploration, and collaboration between AI and human scientists [

3]. The ultimate goal remains the creation of end-to-end digital pipelines that seamlessly integrate basic discovery, prototyping, and scale-up manufacturing [

26].

In the next five to ten years, SDLs are expected to develop toward fully functional digital twins of laboratories and production lines, capable of modeling and optimizing not only synthesis processes but also industrial manufacturing [

26]. This integration would combine basic discovery, prototyping, and large-scale production into a single automated pipeline. Current work already demonstrates adaptation of SDLs for quantum electronics, nanophotonics, and nanomedicine, including autonomous optimization of defects in diamond nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers, design of negative refractive index metamaterials, and development of nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery with programmable pharmacokinetics [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. These developments bring us closer to autonomous platforms that can generate ideas, design experiments, interpret results, and even prepare draft patent documentation with minimal human supervision.

The widespread adoption of self-driving laboratories promises not only to accelerate materials discovery but also to change established research practice, fostering a more data-driven, reproducible, and collaborative research ecosystem. By enabling efficient exploration of vast chemical spaces, these systems could help address pressing global challenges related to energy, healthcare, and sustainability through rapid development of advanced functional materials. Ultimately, overcoming the challenges of data standardization, explainability, and cybersecurity will be crucial to fully realizing this transformative potential and bridging the gap between laboratory-scale innovation and industrial-scale manufacturing.