Submitted:

15 September 2025

Posted:

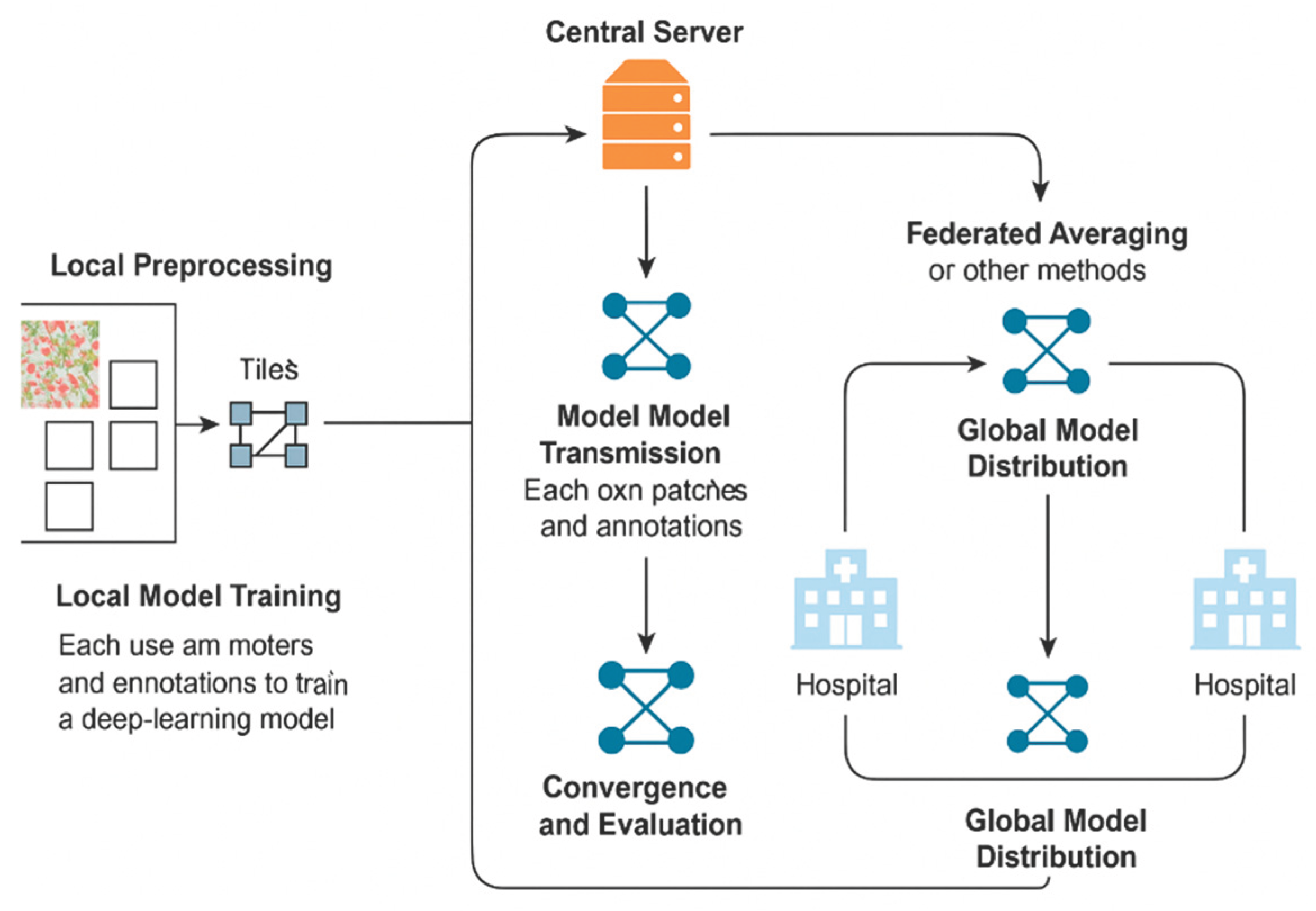

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Opportunities and Challenges in Digital Pathology

3. Federated Learning in Healthcare

4. Federated Learning in Digital Pathology

5. Case Studies and Recent Advances

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madabhushi A, Lee G. Image analysis and machine learning in digital pathology: Challenges and opportunities. Med Image Anal. 2016;33:170–175. [CrossRef]

- Echle A, Rindtorff NT, Brinker TJ, et al. Deep learning in cancer pathology: a new generation of clinical biomarkers. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(4):686–696. [CrossRef]

- Kaissis GA, Makowski MR, Rückert D, Braren RF. Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nat Mach Intell. 2020;2(6):305–311. [CrossRef]

- Campanella G, Hanna MG, Geneslaw L, et al. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat Med. 2019;25(8):1301–1309. [CrossRef]

- McMahan B, Moore E, Ramage D, et al. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In: Proc. AISTATS. 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.05629.

- Li T, Sahu AK, Talwalkar A, Smith V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2020;37(3):50–60. [CrossRef]

- Sheller MJ, Edwards B, Reina GA, et al. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12598. [CrossRef]

- Lu MY, Chen TY, Williamson DF, et al. Federated learning for computational pathology on gigapixel whole slide images. Med Image Anal. 2022;76:102298. [CrossRef]

- Andreux M, du Terrail JP, Beguier C, et al. Federated survival analysis with discrete-time Cox models. In: NeurIPS 2020 Workshop on Machine Learning for Health (ML4H). https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.08997.

- Warnat-Herresthal S, Schultze H, Shastry KL, et al. Swarm Learning for decentralized and confidential clinical machine learning. Nature. 2021;594(7862):265–270. [CrossRef]

- Pantanowitz L, Sharma A, Carter AB, et al. Twenty years of digital pathology: An overview of the road traveled, what is on the horizon, and the emerging role of artificial intelligence. J Pathol Inform. 2020;11:46. [CrossRef]

- Niazi MKK, Parwani AV, Gurcan MN. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):e253–e261. [CrossRef]

- Coudray N, Ocampo PS, Sakellaropoulos T, et al. Classification and mutation prediction from non–small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1559–1567. [CrossRef]

- Lu MY, Williamson DFK, Chen TY, et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature. 2021;594(7861):106–110. [CrossRef]

- Kather JN, Krisam J, Charoentong P, et al. Predicting survival from colorectal cancer histology slides using deep learning: A retrospective multicenter study. PLoS Med. 2019;16(1):e1002730. [CrossRef]

- Baxi V, Edwards R, Montalto M, Saha S. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence in translational medicine and clinical practice. Mod Pathol. 2022;35:23–32. [CrossRef]

- Aeffner F, Zarella MD, Buchbinder N, et al. Introduction to digital image analysis in whole-slide imaging: A white paper from the Digital Pathology Association. J Pathol Inform. 2019;10:9. [CrossRef]

- Stack EC, Wang C, Roman KA, Hoyt CC. Multiplexed immunohistochemistry, imaging, and quantitation: A review, with an assessment of Tyramide signal amplification, multispectral imaging and multiplex analysis. Methods. 2014;70(1):46–58. [CrossRef]

- Bandi P, Geessink O, Manson Q, et al. From detection of individual metastases to classification of lymph node status at the patient level: The CAMELYON17 challenge. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38(2):550–560. [CrossRef]

- Litjens G, Kooi T, Bejnordi BE, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2017;42:60–88. [CrossRef]

- Steiner DF, MacDonald R, Liu Y, et al. Impact of deep learning assistance on the histopathologic review of lymph nodes for metastatic breast cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(12):1636–1646. [CrossRef]

- Courtiol P, Maussion C, Moarii M, et al. Deep learning-based classification of mesothelioma improves prediction of patient outcome. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1519–1525. [CrossRef]

- Chen RJ, Lu MY, Wang J, et al. Pathomic fusion: An integrated framework for fusing histopathology and genomic features for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39(4):802–813. [CrossRef]

- Howard FM, Dolezal J, Kochanny S, et al. The impact of site-specific digital histology signatures on deep learning model accuracy and bias. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4423. [CrossRef]

- Stathonikos N, Veta M, Huisman A, van Diest PJ. Going fully digital: Perspective of a Dutch academic pathology lab. J Pathol Inform. 2013;4:15. [CrossRef]

- De Fauw J, Ledsam JR, Romera-Paredes B, et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat Med. 2018;24(9):1342–1350. [CrossRef]

- DICOM Working Group 26. Supplement 145: Whole Slide Microscopic Image IOD and SOP Classes. National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). 2010. https://www.dicomstandard.org.

- Abels E, Pantanowitz L, Aeffner F, et al. Computational pathology definitions, best practices, and recommendations for regulatory guidance: A white paper from the Digital Pathology Association. J Pathol. 2019;249(3):286–294. [CrossRef]

- Bauer TW, Slaw RJ. Validating whole-slide imaging for diagnostic purposes in pathology: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(2):171–179. [CrossRef]

- Fraggetta F, L’Imperio V, Ameisen D, et al. Best practice recommendations for the implementation of a digital pathology workflow. Virchows Arch. 2021;479(4):581–590. [CrossRef]

- Rieke N, Hancox J, Li W, et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:119. [CrossRef]

- Kaissis GA, Ziller A, Passerat-Palmbach J, et al. End-to-end privacy-preserving deep learning on multi-institutional medical imaging. Nat Mach Intell. 2021;3:473–484. [CrossRef]

- McMahan HB, Moore E, Ramage D, Hampson S, y Arcas BA. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. AISTATS. 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.05629.

- Kairouz P, McMahan HB, Avent B, et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found Trends Mach Learn. 2021;14(1):1–210. [CrossRef]

- Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen T, Tong Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM TIST. 2019;10(2):12. [CrossRef]

- Sheller MJ, Reina GA, Edwards B, Martin J, Bakas S. Multi-institutional deep learning modeling without sharing patient data: A feasibility study on brain tumor segmentation. Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries. Springer, 2019. 2019.

- Pati S, Rieke N, Bakas S, et al. Federated learning enables big data for rare cancer boundary detection. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7340. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Glicksberg BS, Su C, et al. Federated learning for healthcare informatics. J Biomed Inform. 2021;115:103676. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Weng CH, Maleki S, et al. Federated learning in mammography classification: A case study. Med Phys. 2023;50(2):934–947. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Chen PC, Krause J, Peng L. How to read articles that use machine learning: Users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2019;322(18):1806–1816. [CrossRef]

- Lee H, Tajmir S, Lee J, et al. Fully automated deep learning system for bone age assessment. J Digit Imaging. 2017;30(4):427–441. [CrossRef]

- Brisimi TS, Chen R, Mela T, et al. Federated learning of predictive models from federated electronic health records. Int J Med Inform. 2018;112:59–67. [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Xu Y, Yu K, et al. Personalized cross-silo federated learning on non-IID data. AAAI. 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.03797.

- Zhao Y, Li M, Lai L, et al. Federated learning with non-IID data. arXiv preprint. 2018. https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.00582.

- Dayan I, Roth HR, Zhong A, et al. Federated learning for predicting clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1735–1743. 1735. [CrossRef]

- Hitaj B, Ateniese G, Pérez-Cruz F. Deep models under the GAN: Information leakage from collaborative deep learning. Proc. ACM CCS. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Jiang M, Zhang X, et al. FedBN: Federated learning on non-IID features via local batch normalization. ICLR. 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.07623.

- Kisakol, Batuhan, et al. “High-resolution spatial proteomics characterizes colorectal cancer consensus molecular subtypes.” Cancer Research 85.8_Supplement_1 (2025): 161-161.

- Azimi, Mohammadreza, et al. “Spatial effects of infiltrating T cells on neighbouring cancer cells and prognosis in stage III CRC patients.” The Journal of Pathology 264.2 (2024): 148-159.

- Duggan, William P., et al. “Spatial transcriptomic analysis reveals local effects of intratumoral fusobacterial infection on DNA damage and immune signaling in rectal cancer.” Gut Microbes 16.1 (2024): 2350149.

- Aeffner F, et al. Introduction to digital image analysis in whole-slide imaging. J Pathol Inform. 2019;10:9.

- Bandi P, et al. From detection of metastases to classification: CAMELYON17. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38(2):550–560.

- Komura D, Ishikawa S. Machine learning methods for histopathological image analysis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2018;16:34–42.

- Litjens G, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2017;42:60–88.

- Veta M, et al. Predicting breast cancer outcome using histopathology images: challenges and progress. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2021;18:100271.

- Kairouz P, et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found Trends Mach Learn. 2021;14(1):1–210.

- Zhao Y, et al. Federated learning with non-IID data. arXiv. 2018. https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.00582.

- Janowczyk A, Madabhushi A. Deep learning for digital pathology image analysis: A comprehensive tutorial. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2016;55:60–72.

- Lu MY, et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature. 2021;594:106–110.

- Bonawitz K, et al. Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. Proc. CCS. 2017.

- Li T, et al. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. MLSys. 2020.

- Karim MR, et al. FedProx: A federated optimization algorithm. arXiv. 2018. https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.06127.

- Andreux M, et al. Federated survival analysis with discrete-time Cox models. arXiv. 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.08997.

- Beutel D, et al. Flower: A friendly federated learning framework. arXiv. 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.14390.

- NVIDIA Clara Train SDK. https://developer.nvidia.com/clara.

- TensorFlow Federated. https://www.tensorflow.org/federated.

- Warnat-Herresthal S, et al. Swarm learning for decentralized and confidential clinical ML. Nature. 2021;594(7862):265–270.

- MLCommons. MedPerf Benchmarking Platform. https://medperf.org.

- u Y, et al. Federated unsupervised representation learning. NeurIPS. 2020.

- Sattler F, Müller K-R, Samek W. Clustered federated learning: Model-agnostic personalization. arXiv. 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.06165.

- Haggenmüller, Sarah, et al. “Federated Learning for Decentralized Artificial Intelligence in Melanoma Diagnostics.” JAMA Dermatology 160.3 (2024): 303.

- Shukla, Shubhi, et al. “Federated learning with differential privacy for breast cancer diagnosis enabling secure data sharing and model integrity.” Scientific Reports 15.1 (2025): 13061.

- Ciobotaru, Alexandru, et al. “Deep Learning and Federated Learning in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis: A Systematic Review.” IEEE Access (2025).

- Bechar, Amine, et al. “Federated and transfer learning for cancer detection based on image analysis.” Neural Computing and Applications (2025): 1-46.

- Gupta, Chhaya, et al. “Applying YOLOv6 as an ensemble federated learning framework to classify breast cancer pathology images.” Scientific Reports 15.1 (2025): 3769.

- Usharani, C., and A. Selvapandian. “FedLRes: enhancing lung cancer detection using federated learning with convolution neural network (ResNet50).” Neural Computing and Applications (2025): 1-12.

- Saha, Chamak, et al. “Lung-AttNet: An Attention Mechanism based CNN Architecture for Lung Cancer Detection with Federated Learning.” IEEE Access (2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).