I. Introduction

In the context of the rapid development of digital healthcare, electronic health records have become a core foundation of medical services, clinical decision-making, and health management. With the explosive growth of medical data in volume and dimension, traditional centralized data analysis has revealed significant problems such as high risks of privacy leakage, barriers to data sharing, and difficulties in cross-institutional collaboration[

1]. In particular, when highly sensitive personal health information is involved, centralized storage and processing face strict legal compliance challenges and may cause a crisis of public trust. Therefore, achieving efficient and intelligent analysis of electronic health records and scientific prediction of potential health risks while ensuring data privacy and security has become a central problem in medical artificial intelligence[

2].

Federated learning provides a breakthrough solution to this challenge [

3,

4,

5]. Unlike traditional data aggregation, federated learning allows each medical institution to train models locally. It then achieves cross-institutional optimization through secure aggregation of parameters or gradients [

6,

7,

8,

9]. This decentralized framework reduces the risk of privacy leakage and improves model generalization without accessing raw data. For electronic health records, federated learning not only solves the long-standing problem of data silos but also enables the integration of heterogeneous health data distributed across regions and medical systems at the algorithmic level. This mechanism creates conditions for cross-institutional knowledge sharing and the development of generalizable risk prediction models [

10], driving healthcare intelligence toward larger scale and higher reliability[

11].

At the same time, the complexity of electronic health records raises higher demands for risk prediction modeling. The data include structured diagnostic information, unstructured clinical text, multimodal imaging, and time-series physiological monitoring. These data are high-dimensional, noisy, and dynamic. Without effective modeling methods, improper feature selection and inadequate pattern capture may occur, reducing accuracy and stability[

12]. In this context, the federated learning framework shows unique advantages. It can integrate feature patterns from different data sources through distributed collaborative learning and achieve cross-domain knowledge transfer through algorithmic optimization [

13]. This supports scientific approaches for early disease warning, chronic disease management, and emergency risk control, while also creating new pathways for precision medicine and public health governance[

14].

From a macro perspective, research on federated learning for electronic health record analysis and risk prediction has important social value. First, it aligns with international trends in medical data governance, enabling intelligent use of medical resources while ensuring compliance with privacy protection regulations. Second, it helps remove barriers between regions and institutions, promoting balanced medical service development and allowing smaller or remote institutions to share expertise from large hospitals. Third, it provides more sensitive tools for public health monitoring, allowing potential threats to be detected and addressed at the population level in advance, which reduces pressure on medical systems and lowers social costs. These contributions are significant not only in academic research but also in medical practice and social governance.

In conclusion, the introduction of federated learning into electronic health record analysis and health risk prediction provides an innovative approach to the challenges of data privacy and sharing. It also creates opportunities for deeper value extraction from complex medical data. This research direction stands at the frontier of medical artificial intelligence, combining technological innovation with social responsibility. It addresses the challenges of the big data era in healthcare while responding to the goals of national health strategies. By exploring federated learning-driven intelligent analysis, it is possible to restructure the medical data value chain and promote the transformation of healthcare services from experience-driven to data-driven and from passive reaction to proactive prediction, thereby improving human health and well-being at a broader level.

III. Method

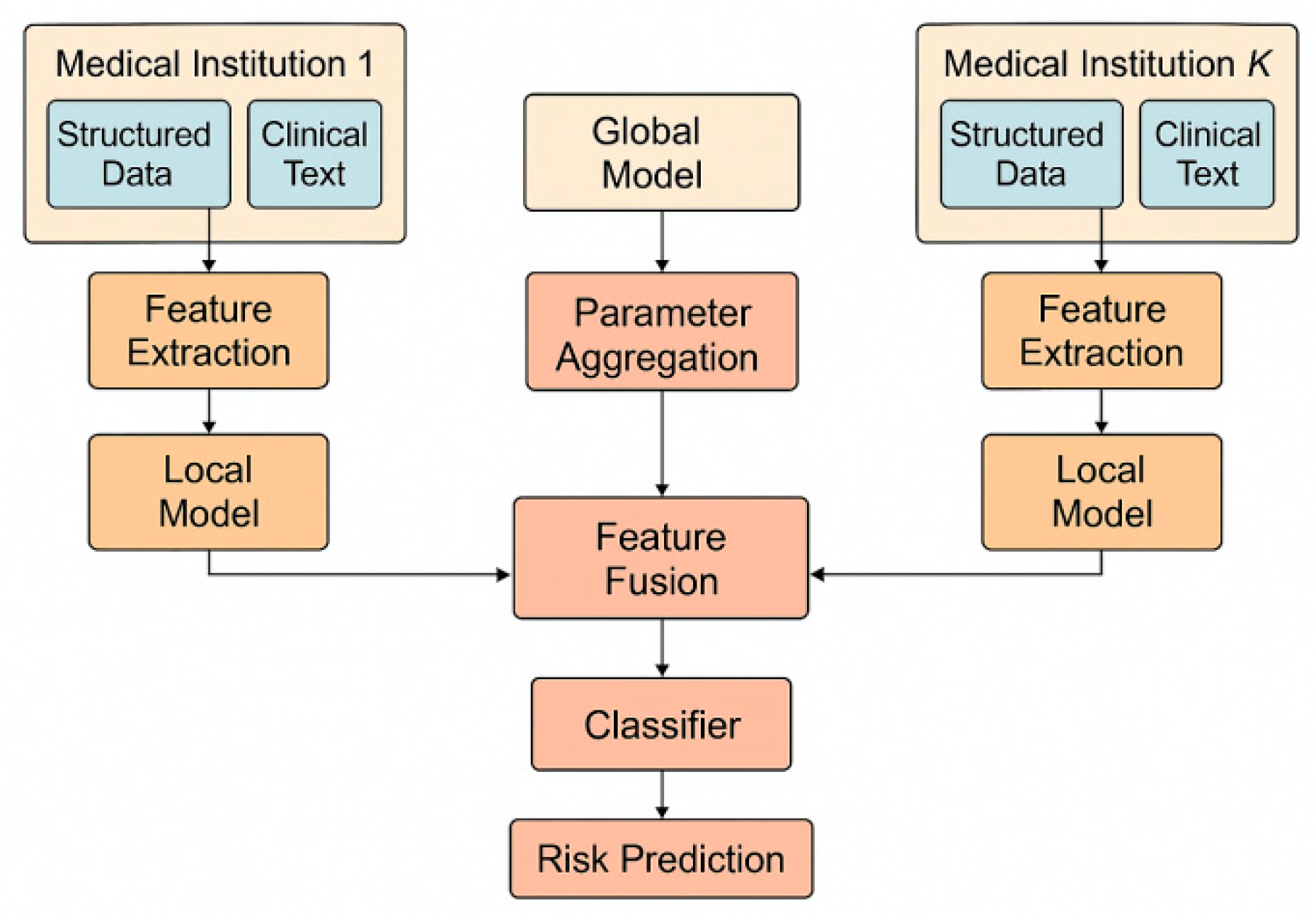

The methodological framework of this study is based on the overall idea of federated learning, which aims to achieve intelligent analysis and health risk prediction while protecting the privacy of electronic health records. The model architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

First, assume that K medical institutions are participating in the modeling, the data distribution of each institution is recorded as

, and its sample size is

. The global goal is to minimize the weighted empirical risk, and its optimization goal can be expressed as:

Here, represents the local objective function of the kth institution. In this way, the contribution of different institutions to the global optimization is proportional to their sample size, thus ensuring the fairness and effectiveness of training.

In each iteration, the kth mechanism performs gradient descent locally, and its update formula is:

Among them,

is the learning rate, and

is the gradient of the current model on the local data. Subsequently, the server side performs a weighted average of the parameter updates uploaded by each organization to obtain the iterative update result of the global model:

This parameter aggregation method effectively avoids the centralized transmission of original data and ensures the protection of data privacy.

To address the multimodal nature of electronic health records, this method applies a feature fusion mechanism within the model architecture. Deep learning and NLP techniques are used to extract and represent information from both structured records and free-text clinical notes, supporting unified summarization and data structuring[

18]. Uncertainty quantification and risk-aware modeling are integrated into the fusion layer to enhance both the reliability and interpretability of risk predictions[

19]. Dynamic prompt fusion approaches are employed to flexibly align and incorporate different data modalities, allowing the system to adapt to complex, heterogeneous EHR datasets[

20]. The model further utilizes multimodal integration strategies to jointly learn from physiological measurements, clinical data, and imaging, thereby improving the comprehensiveness and accuracy of health risk prediction[

21].Assuming that the input multimodal feature vector consists of structured data

, clinical text representation

, and time series signal

, the overall feature embedding can be modeled as:

Here, represents the feature encoding functions of different modalities, and represents the feature concatenation or fusion operation. Through this mechanism, the model can simultaneously capture the structural information, semantic features, and dynamic change patterns of different modalities, providing a more comprehensive representation for risk prediction.

In the risk prediction output stage, this study designed a probabilistic modeling method, inputting the fusion feature h into the classifier and calculating the prediction probability through the Softmax function:

Among them, W and b are learnable parameters and

represent the predicted distribution of risk categories. To achieve effective training, the loss function adopts the cross-entropy form:

where C is the number of categories,

is the one-hot encoding of the true label, and

is the predicted probability. This optimization objective, combined with the update mechanism of federated learning, enables the model to have efficient and robust prediction capabilities while protecting privacy.

IV. Experimental Results

A. Dataset

This study uses MIMIC-IV as the sole data source. The dataset is a rigorously de-identified electronic health record that covers years of inpatient and intensive care scenarios. It contains structured visit and diagnosis codes, laboratory tests and medication records, vital sign time series, and unstructured clinical text such as admission notes and discharge summaries. The multimodal features, long time span, and large sample size make it well-suited for health risk prediction research and cross-modal modeling. All data were generated in real clinical environments, preserving the temporal sequence and heterogeneity of medical processes. Before public release, compliance de-identification was completed, making the dataset suitable for methodological research under privacy constraints.

To align with the study objectives, in-hospital mortality was chosen as the prediction label, and input features were constructed from information available during hospitalization. The study population mainly included adult patients. First hospital admissions or first ICU stays were prioritized to reduce bias from repeated admissions. Samples with very high missingness or abnormal timestamps were excluded. Structured numerical features were normalized after unit unification and outlier truncation. Time-series features were aggregated by fixed windows, with missing masks retained to explicitly indicate data sparsity. Diagnosis and procedure codes were mapped to unified levels. Clinical text was normalized, tokenized, and transformed into sparse or dense representations to allow joint modeling with numerical modalities.

Considering data distribution differences under federated learning, samples were partitioned by care unit type, clinical department, or time slice to simulate cross-institutional heterogeneity and population variation. The split ensured that the same patient did not appear across clients or across different dataset partitions, avoiding information leakage. A 70%/10%/20% train-validation-test split was applied at the patient level, with temporal order preserved to approximate real-world deployment. Data usage followed public access protocols and ethical compliance requirements. All research was conducted only on de-identified data. Processing workflows emphasized reproducibility and portability, enabling reuse and extension to other compliant clinical data sources.

B. Experimental Results

This paper also gives the comparative experimental results, as shown in

Table 1.

From the results in

Table 1, it can be seen that different models show clear differences in the alignment robustness benchmark. The traditional method, DeepMPM, reports relatively low values across the four metrics, with Recall only reaching 0.819. This indicates that the method misses some potential risk patterns and has limitations in capturing complex features of electronic health records. In contrast, Metapred and Scehr achieve better overall performance. This suggests that with more advanced modeling mechanisms, the models improve their ability to integrate multi-source data and extract features.

Looking further, Health-atm outperforms the previous methods on all four metrics. Its ACC reaches 0.888, while Precision and Recall rise to 0.873 and 0.869, respectively. This shows that the method balances accuracy and recall, demonstrating stronger robustness in handling heterogeneous medical data. It maintains good generalization across different samples. However, despite outperforming other compared methods, it still has limitations in capturing deep semantic associations and complex temporal features.

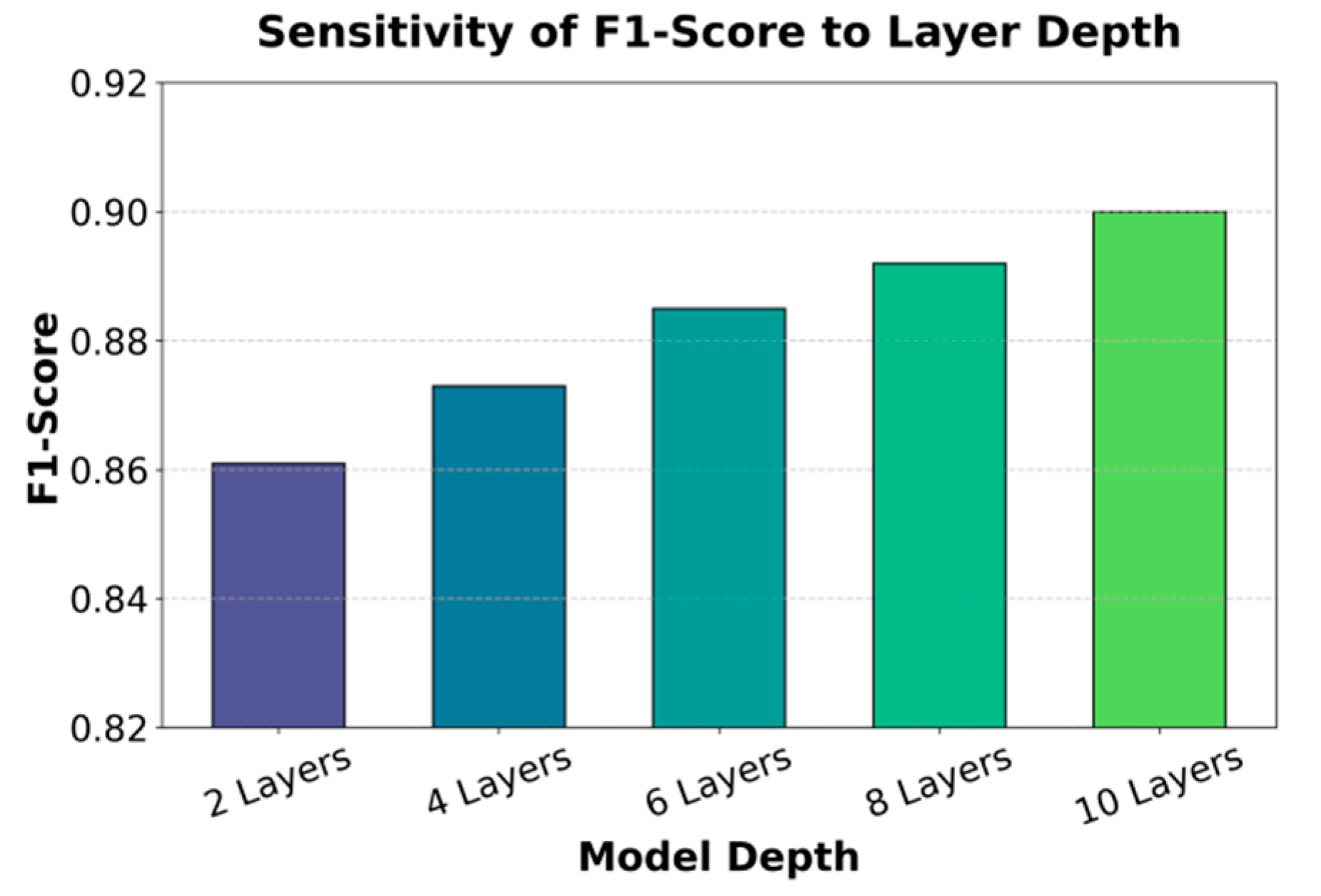

The proposed method achieves the highest values across all metrics. ACC reaches 0.917, while Precision, Recall, and F1-Score are 0.903, 0.897, and 0.900, respectively, all significantly higher than the comparison models. These results show that the federated learning-driven framework can effectively integrate multimodal electronic health record features while preserving data privacy. It improves robustness and predictive accuracy across different scenarios. In particular, the improvement in Recall indicates that the method reduces missed detections of risk patterns and enhances the ability to capture high-risk individuals. Overall, the experimental results confirm the advantages of the proposed method on the alignment robustness task. It not only surpasses existing methods in overall performance but also maintains balanced improvements across all metrics. This outcome aligns well with the research objectives and highlights the practical value of the method in medical data analysis and health risk prediction. By enabling high-precision prediction under privacy protection, the framework provides strong technical support for the intelligent use of electronic health records and lays an important foundation for future clinical decision support and public health management. This paper also presents an experiment on the sensitivity of the number of layers to the F1-Score, and the experimental results are shown in

Figure 2.

From the results in

Figure 2, it can be seen that increasing the number of layers has a significant positive effect on F1-Score. At shallow depths (2 layers and 4 layers), the F1-Score values are 0.861 and 0.873, respectively, which remain relatively low. This indicates that with shallow structures, the model has a limited ability to capture complex features of electronic health records. It struggles to fully integrate semantic and temporal information across modalities, leading to weaker performance in health risk prediction. When the number of layers increases to 6, the F1-Score improves to 0.885, showing a clear performance gain. This stage of improvement suggests that deeper architectures allow the model to better capture nonlinear relationships between cross-modal features, thereby enhancing its discriminative power in risk prediction tasks. The result verifies that moderate increases in depth can strengthen the model's representational ability and generalization.

With further increases to 8 and 10 layers, the F1-Score reaches 0.892 and 0.900, respectively. This provides additional evidence of the advantage of deeper structures in modeling complex medical data. At 10 layers, the model achieves its highest F1-Score, showing that greater depth can effectively reduce information loss in alignment and feature fusion. This makes the model more robust in capturing potential health risk patterns.Overall, the experimental results demonstrate a strong correlation between the number of layers and performance improvement. A moderate increase in depth brings clear benefits. However, excessive depth may cause higher computational costs and a risk of overfitting. Therefore, when designing a federated learning framework for electronic health record analysis, it is necessary to balance performance gains with efficiency. This ensures robust and reliable risk prediction while maintaining privacy protection.

V. Conclusions

This study focuses on federated learning-driven intelligent analysis and health risk prediction of electronic health records, aiming to address the challenges of privacy protection and data silos under traditional centralized modeling. By introducing decentralized collaborative optimization and multimodal feature fusion strategies, the proposed framework achieves effective representation and health risk identification of complex medical data while ensuring data security. The study not only provides a feasible path for the development of medical artificial intelligence but also responds to the dual needs of intelligent processing and privacy compliance in the era of big data. The results clearly show that in the context of electronic health records, federated learning demonstrates robust modeling capacity and good generalization in multi-institution collaboration. By avoiding centralized transmission of raw data, the framework effectively reduces the risk of privacy leakage while ensuring the reliability and scalability of predictive models. This outcome has practical significance for promoting efficient use of medical data. It helps overcome barriers to data sharing across institutions and enhances the practical value of risk prediction in clinical decision-making and patient management.

More importantly, this study not only proposes innovative technical solutions but also highlights broad application prospects. By improving robustness and accuracy in health risk prediction tasks, the framework provides stronger support for early disease intervention, chronic disease management, and population health monitoring. At the same time, its support for cross-institutional collaboration makes it possible for regions with limited medical resources to access intelligent analytical tools. This contributes to promoting healthcare equity and improving public health outcomes.

VI. Future Work

Looking ahead, federated learning-driven intelligent analysis and health risk prediction of electronic health records still have broad development space. On the technical side, more efficient communication mechanisms, more flexible personalized modeling methods, and stronger privacy protection strategies can be further explored to adapt to large-scale heterogeneous environments. On the application side, with the continuous expansion of electronic health record sources and multimodal features, this framework has the potential to integrate deeply with smart healthcare, precision medicine, and public health management. It will promote the transformation of healthcare services from experience-driven to data-driven and from passive response to proactive prediction, providing long-term and sustained support for human health and well-being worldwide.

References

- W. Pan, T. Yang, J. Li, et al., "An adaptive federated learning framework for clinical risk prediction with electronic health records from multiple hospitals," Patterns, vol. 5, no. 1, 100939, 2024.

- H. Zhu, J. Sun, Y. Chen, et al., "FedWeight: mitigating covariate shift of federated learning on electronic health records data through patients re-weighting," npj Digital Medicine, vol. 8, no. 1, 286, 2025.

- S. Wang, S. Han, Z. Cheng, M. Wang and Y. Li, "Federated fine-tuning of large language models with privacy preservation and cross-domain semantic alignment," 2025.

- Z. Xue, "Dynamic structured gating for parameter-efficient alignment of large pretrained models," Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 3, 2024.

- L. Lian, "Semantic and factual alignment for trustworthy large language model outputs," Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 9, 2024.

- Y. Zou, "Federated distillation with structural perturbation for robust fine-tuning of LLMs," Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 3, no. 4, 2024.

- H. Liu, "Structural regularization and bias mitigation in low-rank fine-tuning of LLMs," Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 3, no. 2, 2023.

- M. Gong, Y. Deng, N. Qi, Y. Zou, Z. Xue and Y. Zi, "Structure-learnable adapter fine-tuning for parameter-efficient large language models," arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.03057, 2025. arXiv:2509.03057, 2025.

- R. Wang, Y. Chen, M. Liu, G. Liu, B. Zhu and W. Zhang, "Efficient large language model fine-tuning with joint structural pruning and parameter sharing," 2025.

- X. Yan, W. Wang, M. Xiao, Y. Li, and M. Gao, "Survival prediction across diverse cancer types using neural networks", Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications, pp. 134-138, 2024.

- N. Tahir, A. Khan, S. Ahmed, et al., "Federated learning-based model for predicting mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis," Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 27, e65708, 2025.

- R. Hao, X. Hu, J. Zheng, C. Peng and J. Lin, "Fusion of local and global context in large language models for text classification," 2025.

- X. Yan, J. Du, X. Li, X. Wang, X. Sun, P. Li and H. Zheng, “A Hierarchical Feature Fusion and Dynamic Collaboration Framework for Robust Small Target Detection,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 123456–123467, 2025.

- S. Rajendran, R. Gupta, P. Thomas, et al., "Data heterogeneity in federated learning with electronic health records: case studies of risk prediction for acute kidney injury and sepsis diseases in critical care," PLOS Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 3, e0000117, 2023.

- Jaladanki, J. Xu, et al., "Federated learning of electronic health records to improve mortality prediction in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: machine learning approach," JMIR Medical Informatics, vol. 9, no. 1, e24207, 2021.

- K. Meduri, A. Shah, S. Banerjee, et al., "Leveraging federated learning for privacy-preserving analysis of multi-institutional electronic health records in rare disease research," Journal of Economy and Technology, vol. 3, pp. 177-189, 2025.

- Y. Park, H. Choi, S. Kim, et al., "Federated learning model for predicting major postoperative complications," arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.06641, 2024. arXiv:2404.06641, 2024.

- N. Qi, "Deep learning and NLP methods for unified summarization and structuring of electronic medical records," Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods, vol. 4, no. 3, 2024.

- S. Pan and D. Wu, "Trustworthy summarization via uncertainty quantification and risk awareness in large language models," 2025.

- X. Hu, Y. Kang, G. Yao, T. Kang, M. Wang and H. Liu, "Dynamic prompt fusion for multi-task and cross-domain adaptation in LLMs," arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.18113, 2025. arXiv:2509.18113, 2025.

- Q. Wang, X. Zhang and X. Wang, "Multimodal integration of physiological signals clinical data and medical imaging for ICU outcome prediction," Journal of Computer Technology and Software, vol. 4, no. 8, 2025.

- X. Yang, Q. Liu, M. Zhou, et al., "Personalized federated learning with hierarchical reweighting for multi-center clinical prediction," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 242, 109015, 2025.

- X. S. Zhang, F. Tang, H. H. Dodge, et al., "Metapred: Meta-learning for clinical risk prediction with limited patient electronic health records," Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, pp. 2487-2495, 2019.

- Wang, "SCEHR: Supervised contrastive learning for clinical risk prediction using electronic health records," Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, 2021, pp. 857, 2021.

- T. Ma, C. Xiao and F. Wang, "Health-atm: A deep architecture for multifaceted patient health record representation and risk prediction," Proceedings of the 2018 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, pp. 261-269, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).