Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

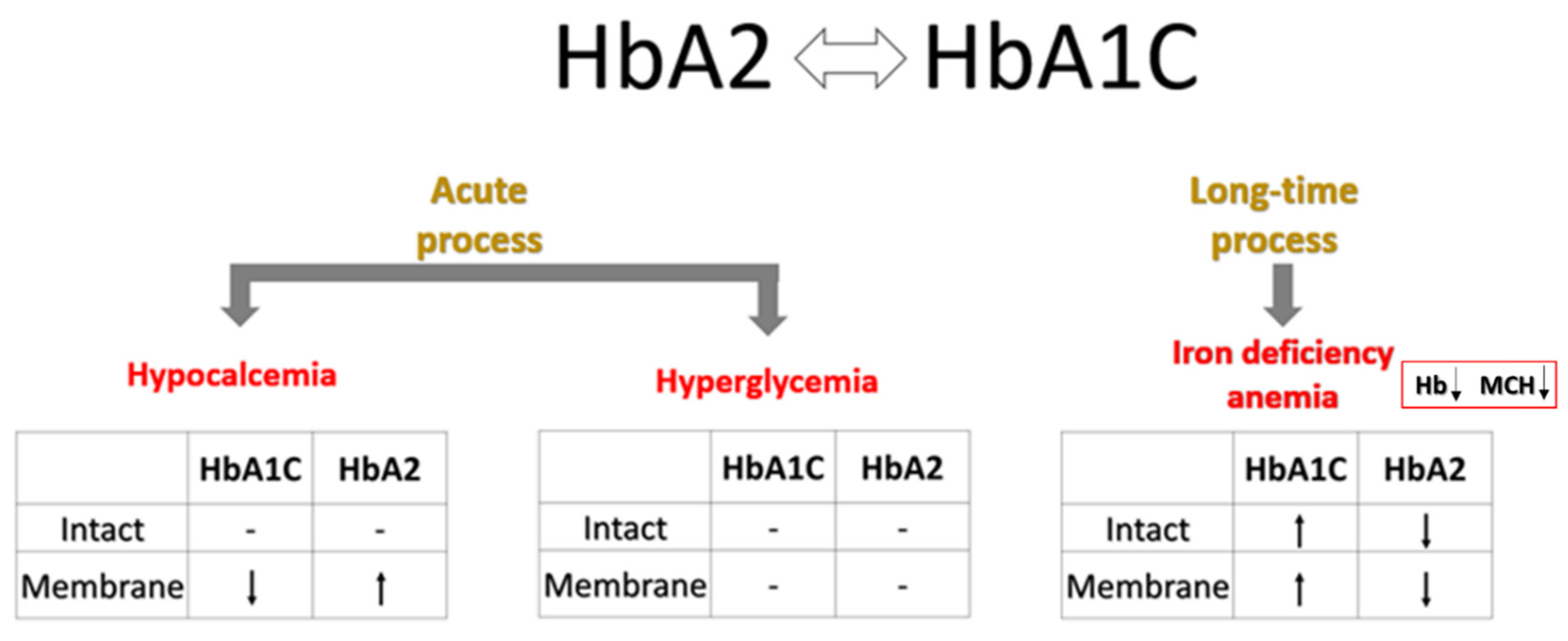

3.1. Heterogeneous Intracellular Distribution of HbA1C and Interference with Other Hb Isoforms

3.2. Possible Involvement of HbA1C in RBC Physiology and Rheology

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Blood Samples

4.2. Buffers and Chemicals

4.3. Hemoglobin Variant Analysis

4.4. RBC Membrane Preparation

4.5. Glucose Consumption, Lactate Release, and Potassium (K+)-Leakage Studies

4.6. Determination of RBC Deformability

4.7. Measurement of Deprotonated Reduced Thiols

4.8. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roden, M.; Shulman, G.I. The Integrative Biology of Type 2 Diabetes. Nature 2019, 576, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Sobel, B.E.; Schneider, D.J. Cardiovascular Complications in Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005, 5, 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Faselis, C.; Katsimardou, A.; Imprialos, K.; Deligkaris, P.; Kallistratos, M.; Dimitriadis, K. Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2020, 18, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Avogaro, A.; Fadini, G.P. Microvascular Complications in Diabetes: A Growing Concern for Cardiologists. Int J Cardiol 2019, 291, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and Molecular Cell Biology of Diabetic Complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [CrossRef]

- Genuth, S.M.; Palmer, J.P.; Nathan, D.M. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. . In Diabetes in America.; Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, et al, Eds.; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US): Bethesda (MD), 2018; Vol. Chapter 1.

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and Regional Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2019 and Projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th Edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2019, 157, 107843. [CrossRef]

- Liddy, A.M.; Grundy, S.; Sreenan, S.; Tormey, W. Impact of Haemoglobin Variants on the Use of Haemoglobin A1c for the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Diabetes: A Contextualised Review. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) 2023, 192, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Raghothama, C.; Rao, P. Degradation of Glycated Hemoglobin. Clinica Chimica Acta 1997, 264, 13–25. [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Kar, M.; Roy, A.; Chakraborti, A.S. Effect of Nonenzymatic Glycation on Functional and Structural Properties of Hemoglobin. Biophys Chem 2005, 113, 289–298. [CrossRef]

- Kar, M.; Chakraborti, A.S. Release of Iron from Haemoglobin--a Possible Source of Free Radicals in Diabetes Mellitus. Indian J Exp Biol 1999, 37, 190–192.

- de Orué Lucana, D.O.; Roscher, M.; Honigmann, A.; Schwarz, J. Iron-Mediated Oxidation Induces Conformational Changes within the Redox-Sensing Protein HbpS. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 28086–28096. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, J.K.; Prakash, M.; Ibrahim, M.S. Relationship between Free Iron and Glycated Hemoglobin in Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes Patients Associated with Complications. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 2008, 23, 67–70. [CrossRef]

- Atamna, H.; Ginsburg, H. Heme Degradation in the Presence of Glutathione. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 24876–24883. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shao, L.; Jiang, M.; Ba, X.; Ma, B.; Zhou, T. Interpretation of HbA1c Lies at the Intersection of Analytical Methodology, Clinical Biochemistry and Hematology (Review). Exp Ther Med 2022, 24, 707. [CrossRef]

- Livshits, L.; Peretz, S.; Bogdanova, A.; Zoabi, H.; Eitam, H.; Barshtein, G.; Galindo, C.; Feldman, Y.; Pajic-Lijakovic, I.; Koren. Ariel; et al. The Impact of Ca2+ on Intracellular of Hemoglobin in Human Erythrocytes. Cells 2023, 12, 2280. [CrossRef]

- Low, P.S.; Allen, D.P.; Zioncheck, T.F.; Chari, P.; Willardson, B.M.; Geahlen, R.L.; Harrison, M.L. Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Band 3 Inhibits Peripheral Protein Binding. J Biol Chem 1987, 262, 4592–4596.

- Harrison, M.L.; Rathinavelu, P.; Arese, P.; Geahlen, R.L.; Low, P.S. Role of Band 3 Tyrosine Phosphorylation in the Regulation of Erythrocyte Glycolysis. J Biol Chem 1991, 266, 4106–4111.

- Passing, R.; Schubert, D. The Binding of Ca 2⊕ to Solubilized Band 3 Protein of the Human Erythrocyte Membrane. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem 1983, 364, 873–878. [CrossRef]

- Makhro, A.; Hänggi, P.; Goede, J.S.; Wang, J.; Brüggemann, A.; Gassmann, M.; Schmugge, M.; Kaestner, L.; Speer, O.; Bogdanova, A. N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptors in Human Erythroid Precursor Cells and in Circulating Red Blood Cells Contribute to the Intracellular Calcium Regulation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2013, 305, C1123–C1138. [CrossRef]

- Makhro, A.; Haider, T.; Wang, J.; Bogdanov, N.; Steffen, P.; Wagner, C.; Meyer, T.; Gassmann, M.; Hecksteden, A.; Kaestner, L.; et al. Comparing the Impact of an Acute Exercise Bout on Plasma Amino Acid Composition, Intraerythrocytic Ca2+ Handling, and Red Cell Function in Athletes and Untrained Subjects. Cell Calcium 2016, 60, 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Puchulu-Campanella, E.; Chu, H.; Anstee, D.J.; Galan, J.A.; Tao, W.A.; Low, P.S. Identification of the Components of a Glycolytic Enzyme Metabolon on the Human Red Blood Cell Membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 848–858. [CrossRef]

- Issaian, A.; Hay, A.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Roberti, D.; Perrotta, S.; Darula, Z.; Redzic, J.; Busch, M.P.; Page, G.P.; Rogers, S.C.; et al. The Interactome of the N-Terminus of Band 3 Regulates Red Blood Cell Metabolism and Storage Quality. Haematologica 2021, 106, 2971–2985. [CrossRef]

- Barshtein, G.; Livshits, L.; Gural, A.; Arbell, D.; Barkan, R.; Pajic-Lijakovic, I.; Yedgar, S. Hemoglobin Binding to the Red Blood Cell (RBC) Membrane Is Associated with Decreased Cell Deformability. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 5814. [CrossRef]

- Walder, J.A.; Chatterjee, R.; Steck, T.L.; Low, P.S.; Musso, G.F.; Kaiser, E.T.; Rogers, P.H.; Arnone, A. The Interaction of Hemoglobin with the Cytoplasmic Domain of Band 3 of the Human Erythrocyte Membrane. J Biol Chem 1984, 259, 10238–10246.

- Castagnola, M.; Messana, I.; Sanna, M.T.; Giardina, B. Oxygen-Linked Modulation of Erythrocyte Metabolism: State of the Art. Blood Transfus 2010, 8 Suppl 3, s53–s58. [CrossRef]

- Standl, E.; Khunti, K.; Hansen, T.B.; Schnell, O. The Global Epidemics of Diabetes in the 21st Century: Current Situation and Perspectives. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019, 26, 7–14. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Nagel, R.L.; Bookchin, R.M.; Roth, E.F.; Tellez-Nagel, I. The Binding of Hemoglobin to Membranes of Normal and Sickle Erythrocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1975, 375, 422–433. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.H.; Rodgers, G.P. HbA2: Biology, Clinical Relevance and a Possible Target for Ameliorating Sickle Cell Disease. Br J Haematol 2015, 170, 781–786. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Prudent, M.; D’alessandro, A. Red Blood Cell Storage Lesion: Causes and Potential Clinical Consequences. Blood Transfus 2019, 17, 27–52. [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Chakrabarty, S.B.; Chakrabarty, A.; Chakrabarti, A. Interaction of Erythroid Spectrin with Hemoglobin Variants: Implications in β-Thalassemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2003, 30, 248–253. [CrossRef]

- Shviro, Y.; Zilber, I.; Shaklai, N. The Interaction of Hemoglobin with Phosphatidylserine Vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1982, 687, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Bucki, R.; Bachelot-Loza, C.; Zachowski, A.; Giraud, F.; Sulpice, J.-C. Calcium Induces Phospholipid Redistribution and Microvesicle Release in Human Erythrocyte Membranes by Independent Pathways. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 15383–15391. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tang, N.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Phillips, L.S.; Smith, R.D.; Metz, T.O. Proteomic Profiling of Nonenzymatically Glycated Proteins in Human Plasma and Erythrocyte Membranes. J Proteome Res 2008, 7, 2025–2032. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Monroe, M.E.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Clauss, T.R.W.; Gritsenko, M.A.; Meng, D.; Petyuk, V.A.; Smith, R.D.; Metz, T.O. Comprehensive Identification of Glycated Peptides and Their Glycation Motifs in Plasma and Erythrocytes of Control and Diabetic Subjects. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 3076–3088. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Low, P.S. Mapping of Glycolytic Enzyme-Binding Sites on Human Erythrocyte Band 3. Biochemical Journal 2006, 400, 143–151. [CrossRef]

- Schuck, P.; Schubert, D. Band 3-hemoglobin Associations The Band 3 Tetramer Is the Oxyhemoglobin Binding Site. FEBS Lett 1991, 293, 81–84. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Breite, A.; Ciraolo, P.; Franco, R.S.; Low, P.S. Characterization of the Deoxyhemoglobin Binding Site on Human Erythrocyte Band 3: Implications for O2 Regulation of Erythrocyte Properties. Blood 2008, 111, 932–938. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; McKenna, M.M.; Krump, N.A.; Zheng, S.; Mendelsohn, L.; Thein, S.L.; Garrett, L.J.; Bodine, D.M.; Low, P.S. Reversible Binding of Hemoglobin to Band 3 Constitutes the Molecular Switch That Mediates O2 Regulation of Erythrocyte Properties. Blood 2016, 128, 2708–2716. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, J.P.; Rietbrock, N. Oxygen Release Kinetics in Healthy Subjects and Diabetic Patients. I: The Role of 2,3-Diphosphoglycerate. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994, 32, 533–535.

- Elsheikh, E.; Aljohani, S.S.; Alshaikhmubarak, M.M.; Alhawl, M.A.; Alsubaie, A.W.; Alsultan, N.; Sharif, A.F.; Ibrahim Ali, S. Implications of Iron Deficiency Anaemia on Glycemic Dynamics in Diabetes Mellitus: A Critical Risk Factor in Cardiovascular Disease. Cureus 2023, 15, e49414. [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, A.; Kouraklis-Symeonidis, A.; Psiroyiannis, A.; Leotsinidis, M.; Kyriazopoulou, V.; Vassilakos, P.; Vagenakis, A.; Zoumbos, N. Inappropriately Low Erythropoietin Response for the Degree of Anemia in Patients with Noninsulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Ann Hematol 2006, 85, 79–85. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, G. Role of Hepcidin in the Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Anemia. Blood Res 2013, 48, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron Metabolism and Iron Disorders Revisited in the Hepcidin Era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, M.; Tutuncu, N.B.; Ertugrul, D.; Tanaci, N.; Guvener, N.D. Effects of Metformin or Rosiglitazone on Serum Concentrations of Homocysteine, Folate, and Vitamin B12 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Complications 2007, 21, 118–123. [CrossRef]

- Sayedali, E.; Yalin, A.E.; Yalin, S. Association between Metformin and Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. World J Diabetes 2023, 14, 585–593. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Thabane, L.; Olier, I.; Li, L.; Ortega-Martorell, S.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Li, G. Relationship between Trajectories of Dietary Iron Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Evidence from a Prospective Cohort Study. Nutr J 2024, 23, 15. [CrossRef]

- Harthoorn-Lasthuizen, E.J.; Lindemans, J.; Langenhuijsen, M.M.A.C. Influence of Iron Deficiency Anaemia on Haemoglobin A 2 Levels: Possible Consequences for ß?Thalassaemia Screening. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999, 59, 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Tyczyńska, M.; Hunek, G.; Kawecka, W.; Brachet, A.; Gędek, M.; Kulczycka, K.; Czarnek, K.; Flieger, J.; Baj, J. Association Between Serum Concentrations of (Certain) Metals and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 7443. [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.; Stern, Z.; Gutman, A.; Naparstek, Y.; Gavin, J.R.; Avioli, L. V. Plasma Calcium and Phosphate Levels in an Adult Noninsulin-Dependent Diabetic Population. Calcif Tissue Int 1986, 39, 316–318. [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Estruch, R.; Bulló, M.; Casas, R.; Díaz-López, A.; Basora, J.; Fitó, M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Increased Serum Calcium Levels and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Individuals at High Cardiovascular Risk. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 3084–3091. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.; Hanley, A.J.; Rewers, M.J.; Haffner, S.M. Calcium and Phosphate Concentrations and Future Development of Type 2 Diabetes: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1366–1374. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, D.; Fonseca, V.; Aude, Y.W.; Lamas, G.A. Chelation Therapy to Prevent Diabetes-Associated Cardiovascular Events. Current Opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and Obesity 2018, 25, 258–266. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Nagengast, A.K.; Knapp, C.; Behrens, B.; Dewey, E.N.; Goodman, A.; Bommiasamy, A.; Schreiber, M. Massive Transfusions and Severe Hypocalcemia: An Opportunity for Monitoring and Supplementation Guidelines. Transfusion (Paris) 2021, 61, S188–S194. [CrossRef]

- Aleem, A.; Al-Momen, A.-K.; Al-Harakati, M.S.; Hassan, A.; Al-Fawaz, I. Hypocalcemia Due to Hypoparathyroidism in β-Thalassemia Major Patients. Ann Saudi Med 2000, 20, 364–366. [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, S.; Vincent, J.-L. Calcium Administration for Cardiovascular Support in Critically Ill Patients: When Is It Indicated? J Intensive Care Med 1995, 10, 91–100. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.J.; Woodhead, J.S.; Hayward, R.D. The Nature of Hypocalcaemia in Acute Pancreatitis. British Journal of Surgery 2005, 65, 216–218. [CrossRef]

- Decaux, G.; Hallemans, R.; Mockel, J.; Naeije, R. Chronic Alcoholism: A Predisposing Factor for Hypocalcemia in Acute Pancreatitis. Digestion 1980, 20, 175–179. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Kong, H.; Ding, W.; Wu, C.; Ji, N.; Huang, M.; Li, T.; Wang, X.; Wen, J.; Wu, W.; et al. Abnormal Coagulation Function of Patients With COVID-19 Is Significantly Related to Hypocalcemia and Severe Inflammation. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 638194-.. [CrossRef]

- Zaloga, G.P.; Chernow, B. The Multifactorial Basis for Hypocalcemia During Sepsis. Ann Intern Med 1987, 107, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, P.N.; Margaritelis, N. V.; Paschalis, V.; Theodorou, A.A.; Vrabas, I.S.; Kyparos, A.; D’Alessandro, A.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Erythrocyte Metabolism. Acta Physiologica 2024, 240, e14081. [CrossRef]

- Montel-Hagen, A.; Kinet, S.; Manel, N.; Mongellaz, C.; Prohaska, R.; Battini, J.-L.; Delaunay, J.; Sitbon, M.; Taylor, N. Erythrocyte Glut1 Triggers Dehydroascorbic Acid Uptake in Mammals Unable to Synthesize Vitamin C. Cell 2008, 132, 1039–1048. [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, A.; DeZutter, J.; Ganguly, A.; Devaskar, S.U. Will the Original Glucose Transporter Isoform Please Stand Up! American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009, 297, E836–E848. [CrossRef]

- Galochkina, T.; Ng Fuk Chong, M.; Challali, L.; Abbar, S.; Etchebest, C. New Insights into GluT1 Mechanics during Glucose Transfer. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 998. [CrossRef]

- Guizouarn, H.; Allegrini, B. Erythroid Glucose Transport in Health and Disease. Pflugers Arch 2020, 472, 1371–1383. [CrossRef]

- Domene, C.; Wiley, B.; Gonzalez-Resines, S.; Naftalin, R.J. Insight into the Mechanism of <scp>d</Scp> -Glucose Accelerated Exchange in GLUT1 from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 928–939. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Yan, L.-J. Protein Modifications as Manifestations of Hyperglycemic Glucotoxicity in Diabetes and Its Complications. Biochem Insights 2016, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.F.; Basu, R.; Wise, S.; Caumo, A.; Cobelli, C.; Rizza, R.A. Normal Glucose-Induced Suppression of Glucose Production but Impaired Stimulation of Glucose Disposal in Type 2 Diabetes: Evidence for a Concentration-Dependent Defect in Uptake. Diabetes 1998, 47, 1735–1747. [CrossRef]

- Porter-Turner, M.M.; Skidmore, J.C.; Khokher, M.A.; Singh, B.M.; Rea, C.A. Relationship between Erythrocyte GLUT1 Function and Membrane Glycation in Type 2 Diabetes. Br J Biomed Sci 2011, 68, 203–207. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Peng, F.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, W.; Feng, H. The Abnormality of Glucose Transporter in the Erythrocyte Membrane of Chinese Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2000, 1466, 306–314. [CrossRef]

- Martins Freire, C.; King, N.R.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Stephenson, D.; Moura, P.L.; Dobbe, J.; Streekstra, G.; D’Alessandro, A.; Toye, A.M.; Satchwell, T.J. Complete Absence of GLUT1 Does Not Impair Human Terminal Erythroid Differentiation. Blood Adv 2024, bloodadvances.2024012743. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.; Fu, X.; An, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. Lactate Metabolism in Human Health and Disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 305. [CrossRef]

- Pattillo, R.E.; Gladden, L.B. Red Blood Cell Lactate Transport in Sickle Disease and Sickle Cell Trait. J Appl Physiol 2005, 99, 822–827. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.A.; Nor El-Din, A.K.A. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Activity and Protein Oxidative Modification in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Biomark 2013, 2013, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Davies, M.J. Protein and Low Molecular Mass Thiols as Targets and Inhibitors of Glycation Reactions. Chem Res Toxicol 2006, 19, 1668–1676. [CrossRef]

- Uceda, A.B.; Mariño, L.; Casasnovas, R.; Adrover, M. An Overview on Glycation: Molecular Mechanisms, Impact on Proteins, Pathogenesis, and Inhibition. Biophys Rev 2024, 16, 189–218. [CrossRef]

- Livshits, L.; Barshtein, G.; Arbell, D.; Gural, A.; Levin, C.; Guizouarn, H. Do We Store Packed Red Blood Cells under “Quasi-Diabetic” Conditions? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 992–992. [CrossRef]

- Kosower, E.M.; Kosower, N.S. [12] Bromobimane Probes for Thiols. In; 1995; pp. 133–148.

- Warkentin, T.; Barr, R.; Ali, M.; Mohandas, N. Recurrent Acute Splenic Sequestration Crisis Due to Interacting Genetic Defects: Hemoglobin SC Disease and Hereditary Spherocytosis. Blood 1990, 75, 266–270. [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, N.; Chasis, J.A. Red Blood Cell Deformability, Membrane Material Properties and Shape: Regulation by Transmembrane, Skeletal and Cytosolic Proteins and Lipids. Semin Hematol 1993, 30, 171–192.

- Parthasarathi, K.; Lipowsky, H.H. Capillary Recruitment in Response to Tissue Hypoxia and Its Dependence on Red Blood Cell Deformability. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1999, 277, H2145–H2157. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, Y.; Chierego, M.; Piagnerelli, M.; Verdant, C.; Dubois, M.-J.; Koch, M.; Creteur, J.; Gullo, A.; Vincent, J.-L.; De Backer, D. Microvascular Response to Red Blood Cell Transfusion in Patients with Severe Sepsis*. Crit Care Med 2007, 35, 1639–1644. [CrossRef]

- Friederichs, E.; Farley, R.A.; Meiselman, H.J. Influence of Calcium Permeabilization and Membrane-attached Hemoglobin on Erythrocyte Deformability. Am J Hematol 1992, 41, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Liang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, L.; Song, H.; et al. Metabolite and Protein Shifts in Mature Erythrocyte under Hypoxia. iScience 2024, 27, 109315. [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.E.; Utterback, N.G.; Puma, J. La Reduced Erythrocyte Deformability in Diabetes. Diabetes 1978, 27, 895–901. [CrossRef]

- Bareford, D.; Jennings, P.E.; Stone, P.C.; Baar, S.; Barnett, A.H.; Stuart, J. Effects of Hyperglycaemia and Sorbitol Accumulation on Erythrocyte Deformability in Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Pathol 1986, 39, 722–727. [CrossRef]

- Fujita; Tsuda; Takeda; Yu; Fujimoto; Kajikawa; Nishimura; Mizuno; Hamamoto; Mukai; et al. Nisoldipine Improves the Impaired Erythrocyte Deformability Correlating with Elevated Intracellular Free Calcium-ion Concentration and Poor Glycaemic Control in NIDDM. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999, 47, 499–506. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.S.; Madsen, J.W.; Rybicki, A.C.; Nagel, R.L. Oxidation of Spectrin and Deformability Defects in Diabetic Erythrocytes. Diabetes 1991, 40, 701–708. [CrossRef]

- Babu, N. Influence of Hypercholesterolemia on Deformability and Shape Parameters of Erythrocytes in Hyperglycemic Subjects. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2009, 41, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Cahn, A.; Livshits, L.; Srulevich, A.; Raz, I.; Yedgar, S.; Barshtein, G. Diabetic Foot Disease Is Associated with Reduced Erythrocyte Deformability. Int Wound J 2016, 13, 500–504. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, L.Z. Hemoglobin A1c Level Higher than 9.05% Causes a Significant Impairment of Erythrocyte Deformability in Diabetes Mellitus. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar) 2018, 14, 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol Rev 2018, 98, 2133–2223. [CrossRef]

- Hamley, S.; Kloosterman, D.; Duthie, T.; Dalla Man, C.; Visentin, R.; Mason, S.A.; Ang, T.; Selathurai, A.; Kaur, G.; Morales-Scholz, M.G.; et al. Mechanisms of Hyperinsulinaemia in Apparently Healthy Non-Obese Young Adults: Role of Insulin Secretion, Clearance and Action and Associations with Plasma Amino Acids. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 2310–2324. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. Hyperinsulinemia and Its Pivotal Role in Aging, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7797. [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.-F.; Aloulou, I.; Varlet-Marie, E. Hemorheological Aspects of the Metabolic Syndrome: Markers of Insulin Resistance, Obesity or Hyperinsulinemia? Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2004, 30, 203–209.

- Farber, P.L.; Dias, A.; Freitas, T.; Pinho, A.C.; Viggiano, D.; Saldanha, C.; Silva-Herdade, A.S. Evaluation of Hemorheological Parameters as Biomarkers of Calcium Metabolism and Insulin Resistance in Postmenopausal Women. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2021, 77, 395–410. [CrossRef]

- Barshtein, G.; Gural, A.; Zelig, O.; Arbell, D.; Yedgar, S. Unit-to-Unit Variability in the Deformability of Red Blood Cells. Transfusion and Apheresis Science 2020, 59, 102876. [CrossRef]

- Barshtein, G.; Rasmusen, T.L.; Zelig, O.; Arbell, D.; Yedgar, S. Inter-donor Variability in Deformability of Red Blood Cells in Blood Units. Transfusion Medicine 2020, 30, 492–496. [CrossRef]

- Barshtein, G.; Pries, A.R.; Goldschmidt, N.; Zukerman, A.; Orbach, A.; Zelig, O.; Arbell, D.; Yedgar, S. Deformability of Transfused Red Blood Cells Is a Potent Determinant of Transfusion-Induced Change in Recipient’s Blood Flow. Microcirculation 2016, 23, 479–486. [CrossRef]

| Reference Ranges | Healthy | Prediabetes | Type 2 (T2) Diabetes | |

| n | 56 | 53 | 56 | |

| Age (years) | 58.3±14.0 | 65.3±11.3 | 62.6±14.3 | |

| M/F | 24/32 | 29/24 | 30/26 | |

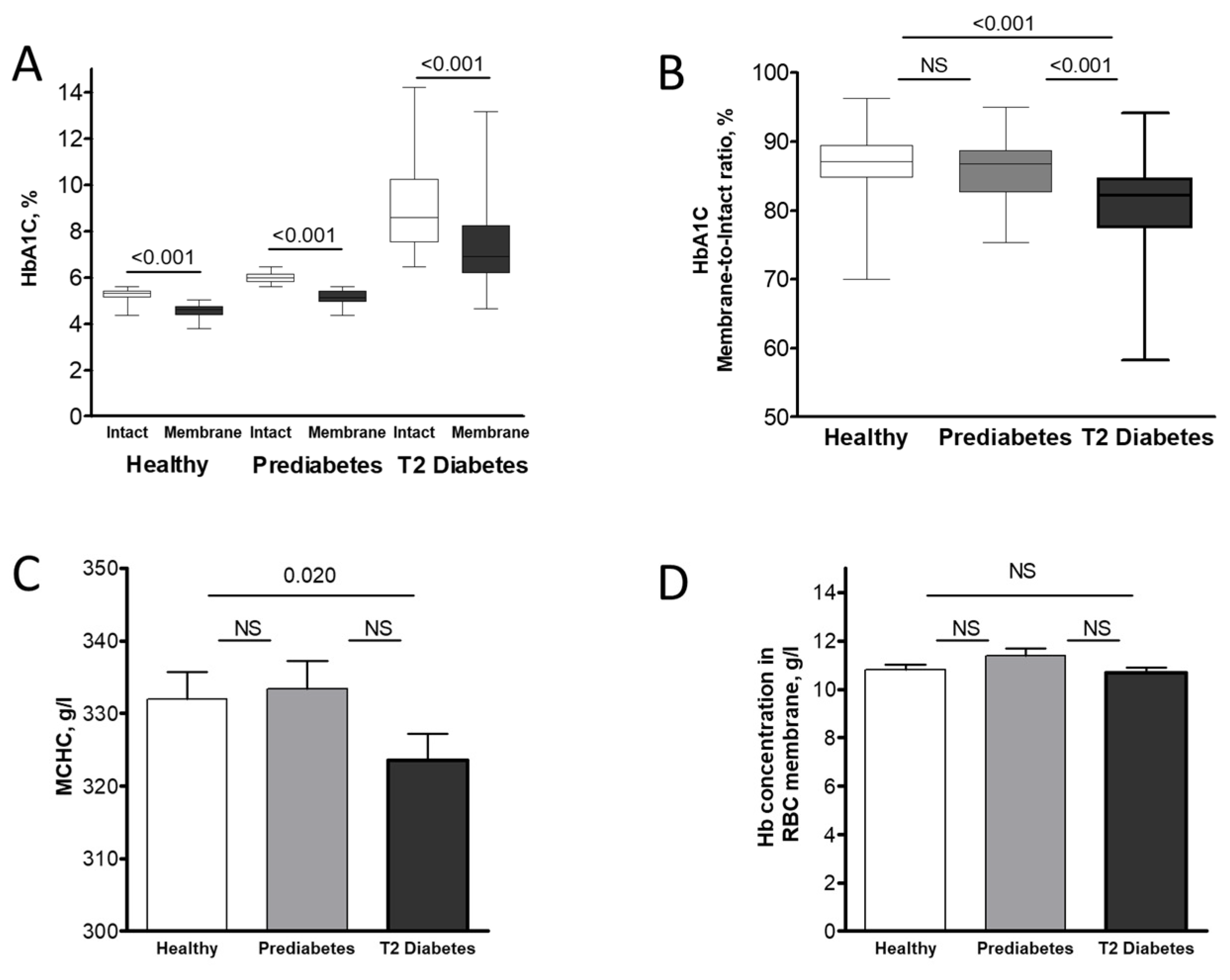

| HbA1C (%) | <5.7 | 5.24±0.26 | 6.01±0.16 | 8.88±1.67 |

| RBC (106/µL) |

Female: 4.0-5.0 Male: 4.5-5.5 |

4.71±0.55 | 4.77±0.51NS | 5.03±0.630.005/0.021 |

| HCT (%) |

Female: 37.0-47.0 Male: 40.0-54.0 |

41.1±4.6 | 41.8±3.8 NS | 42.6±4.9NS/NS |

| Hb (g/dL) |

Female: 12.0-15.0 Male: 14.0-17.0 |

13.6±1.6 | 13.8±1.2 NS | 13.9±1.8 NS/NS |

| MCV (fL) |

Female: 80.0-94.0 Male: 80.0-95.0 |

87.1±8.2 | 88.2±5.8 NS | 84.8±6.6 NS/0.007 |

| MCH (pg) | 27.0-31.0 | 29.0±2.9 | 29.1±2.0 NS | 27.7±2.4 0.008/0.002 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 32.0-35.0 | 33.1±1.3 | 33.0±1.2 NS | 32.5±1.4 0.020/NS |

| RDW (%) | 11.5-14.5 | 13.9±1.7 | 13.9±0.9 NS | 14.3±1.4 NS/0.046 |

| HbF (%) | 0.5-1.3 | 0.41±0.34 | 0.33±0.13 NS | 0.40±0.26 NS/NS |

| HbA2 (%) | 1.5-3.6 | 2.83±0.34 | 2.81±0.32 NS | 2.64±0.35 0.005/0.009 |

| HbA0 (%) | >95.9 | 96.8±0.5 | 96.9±0.3 NS | 97.0±0.5 0.027/NS |

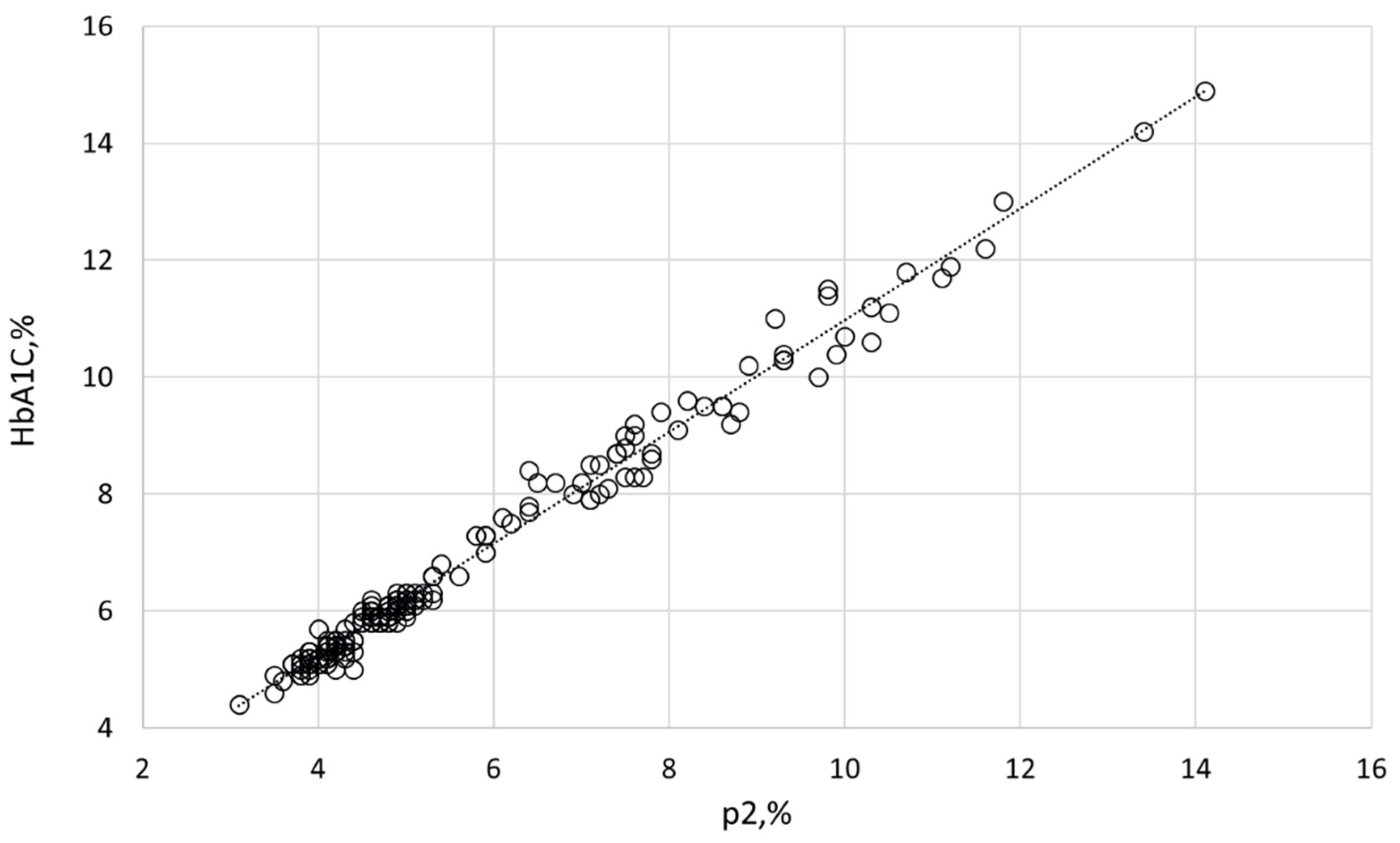

| p2 (related to HbA1C) (%) | <4.5 | 4.06±0.26 | 4.79±0.22<0.001 | 7.92±1.87 <0.001/<0.001 |

|

Healthy (n = 56) |

Prediabetes (n = 53) |

T2 Diabetes (n = 56) |

||||

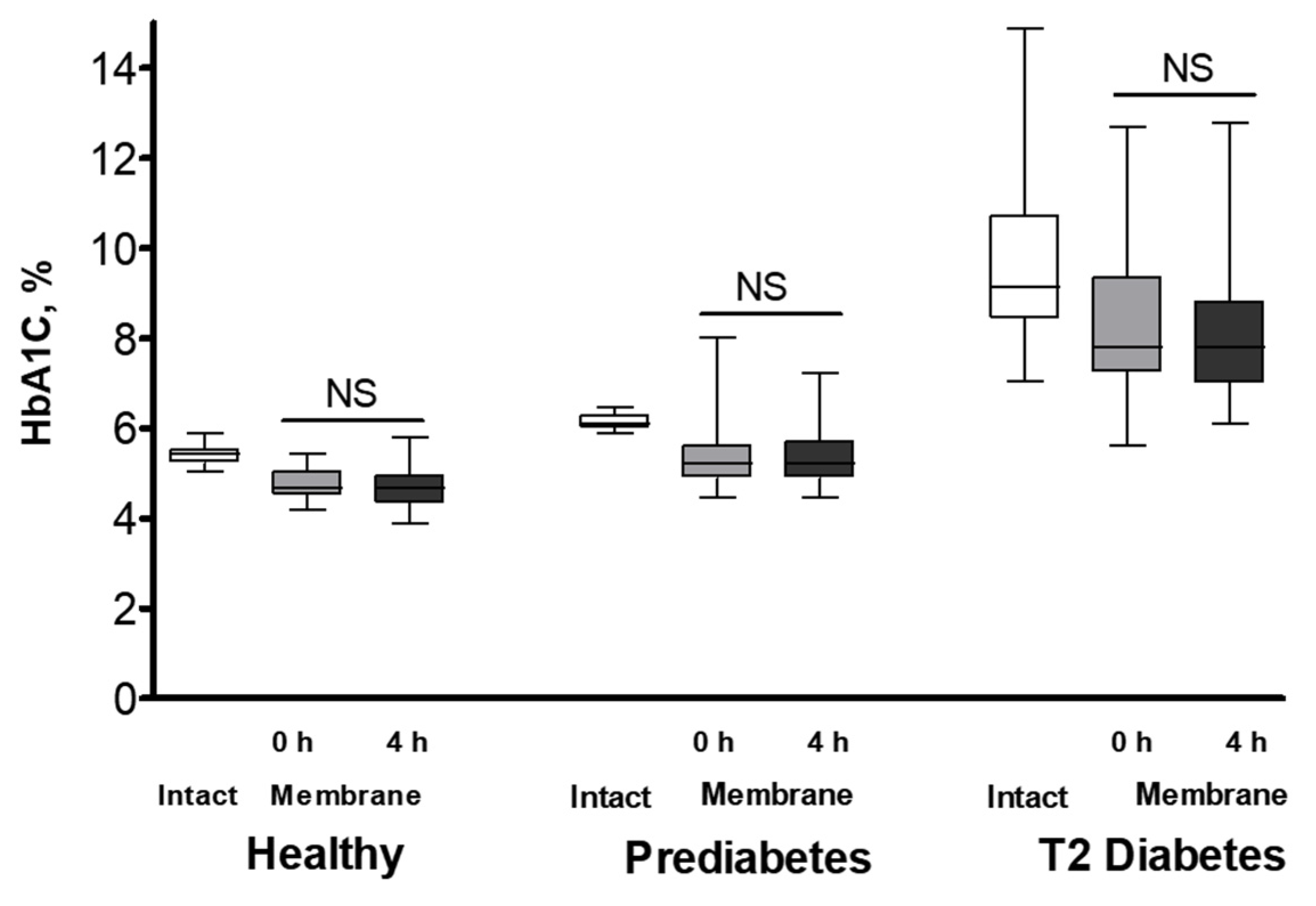

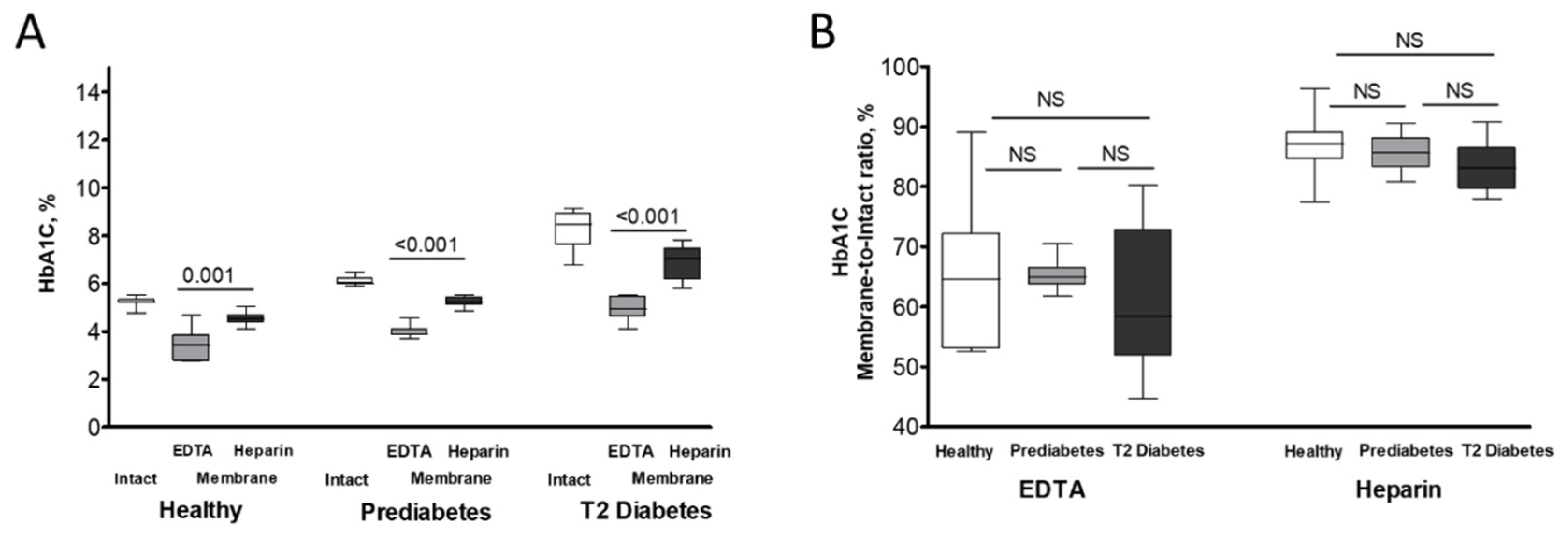

| Intact | Membrane | Intact | Membrane | Intact | Membrane | |

| HbF | 0.30±0.9 | 0.30±0.11 | 0.30±0.04NS | 0.30±0.06NS | 0.30±0.07NS/NS | 0.30±0.08NS/0.043 |

| HbA2 | 2.80±0.09 | 4.50±0.17 | 2.80±0.09NS | 4.30±0.19NS | 2.60±0.090.001/0.003 | 4.20±0.24 NS/NS |

| HbA0 | 96.8±0.1 | 95.2±0.2 | 96.8±0.09NS | 95.4±0.2NS | 97.0±0.10.021/0.049 | 95.2±0.3NS/NS |

| HbA1C | 5.33±0.07 | 4.61±0.08 | 6.00±0.06<0.001 | 5.14±0.08<0.001 | 8.58±0.47<0.001/<0.001 | 6.91±0.43<0.001/<0.001 |

|

Whole Cohort (n = 165) |

Healthy (n = 56) |

Prediabetes (n = 53) |

T2 Diabetes (n = 56) |

|||||

| Intact | Membrane | Intact | Membrane | Intact | Membrane | Intact | Membrane | |

| HbF | 0.013 (NS) |

-0.018 (NS) |

0.146 (NS) |

-0.011 (NS) |

0.107 (NS) |

-0.013 (NS) |

-0.063 (NS) |

-0.186 (NS) |

| HbA2 |

-0.334 (<0.001) |

-0.318 (<0.001) |

-0.263 (NS) |

-0.525 (<0.001) |

0.176 (NS) |

-0.449 (<0.001) |

-0.391 (0.003) |

-0.630 (<0.001) |

| HbA0 |

+0.259 (<0.001) |

+0.281 (<0.001) |

0.082 (NS) |

+0.415 (0.001) |

-0.213 (NS) |

+0.406 (0.003) |

+0.342 (0.010) |

+0.629 (<0.001) |

| Healthy | Prediabetes | T2 Diabetes | ||||

| Intact HbA1C | Membrane HbA1C | Intact HbA1C | Membrane HbA1C | Intact HbA1C | Membrane HbA1C | |

| K+ loss (mM/h per Hb) | - 0.040 +0.043 (NS) (NS) (n=15) |

+0.010 +0.009 (NS) (NS) (n=14) |

-0.037 +0.166 (NS) (NS) (n=14) |

|||

| Glucose consumption (mg/dL per hour per Hb) | +0.083 -0.193 (NS) (NS) (n=15) |

+0.011 -0.561 (NS) (0.037) (n=14) |

-0.222 -0.206 (NS) (NS) (n=14) |

|||

|

Lactate release (mM/h per Hb) |

-0.515 +0.469 (0.049) (NS) (n=15) |

-0.489 -0.034 (NS) (NS) (n=14) |

+0.318 +0.264 (NS) (NS) (n=14) |

|||

| Intact deprotonated reduced thiol (A.U., normalized) |

+0.629 +0.403 (0.012) (NS) (n=15) |

+0.497 +0.252 (NS) (NS) (n=15) |

-0.144 -0.284 (NS) (NS) (n=17) |

|||

| Median elongation rate | +0.013 +0.175 (NS) (NS) (n=9) |

-0.839 -0.256 (0.005) (NS) (n=9) |

-0.345 -0.222 (NS) (NS) (n=9) |

|||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).