1. Introduction

Health disparities among social groups pose significant challenges to equity, human rights, and societal well-being [

1]. The manifestation of disease across different social strata necessitates an analysis of disease clustering and the factors contributing to health inequalities [

2]. Social deprivation, as a determinant of health, is multi-dimensional, with numerous indicators influencing underlying health outcomes [

3]. These dimensions can be examined using sophisticated data analysis techniques, such as non-linear dimensionality reduction methods, which help to identify patterns of social disparities [

4]. One such method, stochastic approximation applied to principal curves, is particularly useful in organizing data into clusters that reveal trends based on latent factors [

5]. This approach can identify systematic social disparities, such as those linked to socioeconomic status and multi-morbidity prevalence, which are often overlooked in traditional models [

6,

7]. It also highlights issues like zero-inflated count data, where certain health visits or conditions, particularly minor ones, are underreported due to systemic factors like insurance policies or police enforcement [

5,

8].

To address these gaps, the study proposes using the Visit Pyramid Model, applied to data from the Netherlands, to evaluate the effectiveness of public health surveillance systems [

5,

9]. This model aims to determine whether enhancing surveillance can lead to quicker and more reliable evidence generation for public health interventions [

10]. A multi-country pilot study will be conducted to assess whether evidence gaps in Europe significantly impact plan-do-study-act cycles [

2,

11,

12]. The study will yield recommendations for prioritizing high-risk populations, developing mobile phone-based evaluation systems for hard-to-reach groups, and offering alternative policy measures for vulnerable populations such as young women and the elderly [

13,

14,

15]. The overarching goal of this research is to identify gaps in public health surveillance, propose practical tools for data integration, and recommend policies for vulnerable groups, particularly addressing health inequities in Europe [

2,

5,

16].

2. Overview of Public Health in Europe and Current Challenges

Public health systems in Europe, like those globally, are facing unprecedented pressures due to financial constraints, workforce shortages, and logistical challenges [

17,

18]. These issues are exacerbated by rising health inequalities, aging populations, and the youth bulge in some regions, as well as the rapid societal and environmental changes that continue to shape public health challenges [

7,

19]. These dynamics require responsive and adaptive health policies [

4,

7,

20]. Increasingly, public health is scrutinized due to concerns over taxation, state intervention, and research ethics [

7,

21]. Despite these challenges, there is a growing recognition of the need to invest in health policy research to understand better and address the evolving public health crises, which are not confined to European countries but are globally significant [

2,

5,

22,

23]. These crises require cross-national solutions to tackle issues like chronic diseases, migration, and climate change, which transcend national boundaries [

5,

24].

In Europe, public health systems are under stress, and although initial reactions to health crises often involve emergency funding, long-term sustainable solutions are necessary [

25,

26]. This requires a holistic approach that integrates socioeconomic factors, health system performance, and health equity into public health research [

3,

27]. The complexity of public health challenges, including chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity, continues to strain healthcare systems [

27,

28]. Addressing social determinants of health and reducing health disparities across populations are crucial in tackling these challenges effectively [

29].

2.1. Public Health and Health Inequities

Health inequities are a significant concern in Europe, arising from social, political, and economic factors that disproportionately affect vulnerable populations [

26]. These inequities are perpetuated by systematic and unfair social processes that create barriers to accessing healthcare, particularly for migrants, minorities, and the elderly [

5,

30]. The WHO defines health inequities as those that arise from unfair social conditions, a deeper understanding of these inequities requires addressing the social determinants of health, such as income inequality, education, and access to healthcare [

7]. Political systems play a critical role in shaping these inequities, as they regulate the distribution of resources and opportunities [

16].

Addressing health inequities in Europe requires a multi-sectoral approach that integrates health policy with efforts to improve social conditions the research in this area should focus on identifying and analyzing the systematic processes that lead to inequities, and proposing policy solutions that promote health equity across all population groups [

5,

31].

3. Methodology of the Study

This study evaluates the

state of public health across Europe, focusing on health system performance, public health interventions, and the impacts of

climate health resilience and

digital health interventions. The methodology integrates a systematic review of the available public health studies from EU countries and utilizes the CINeMA methodology to assess confidence in network meta-analysis results [

32,

33].

3.1. Data Collection Techniques

Data for this study were primarily sourced from the following public health datasets and initiatives:

- 1.

European Health Interview Survey (EHIS):

The EHIS provides cross-national health data collected from multiple EU member states, offering insights into health status, healthcare access, and socioeconomic factors. Data from the 2015-2022 waves were utilized to evaluate health determinants across the EU.

Table 1.

Summary of EHIS Data Sources and Health Indicators.

Table 1.

Summary of EHIS Data Sources and Health Indicators.

| EHIS Data Source |

Health Indicators Collected |

Population/Region |

Year(s) of Data Collection |

Key Findings |

Additional Notes |

| EHIS Wave 1 (2013-2015) |

Health status, chronic conditions, health behavior (smoking, alcohol consumption), and healthcare access |

EU Member States |

2013-2015 |

There was variation in health status and access to healthcare between countries. There is a high prevalence of chronic diseases in Eastern Europe. |

Focus on cross-national health inequalities and socioeconomic factors.

|

| EHIS Wave 2 (2017-2020) |

Life expectancy, mental health conditions, hospital admissions, and physical activity |

EU Member States |

2017-2020 |

Differences in mental health conditions and physical activity across EU countries, particularly in Southern Europe. |

Covers key health determinants and socioeconomic status

|

| EHIS 2021 |

Vaccination rates, COVID-19 health outcomes, self-reported health status, and healthcare utilization |

EU Member States |

2021 |

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors and healthcare utilization. Increased mental health issues across EU countries. |

Focus on COVID-19-related health outcomes and resilience in health systems |

| Eurostat EHIS Data Aggregated |

Mortality rates, disease prevalence (e.g., cancer, diabetes), and healthcare resources (e.g., doctors per 100,000) |

EU Member States |

2019-2022 |

Higher mortality rates from NCDs in Eastern and Southern EU regions. Significant health disparities across countries. |

Includes national health data aggregated for policy analysis

|

- 2.

EU4Health Programme:

The EU4Health Programme provides extensive health intervention data and public health system reforms across EU countries. This dataset focuses on digital health, mental health, and climate-health resilience, with the aim of improving health system resilience in the face of future challenges.

Table 2.

Summary of EU4Health Projects and Interventions Evaluated.

Table 2.

Summary of EU4Health Projects and Interventions Evaluated.

| EU4Health Project/Intervention |

Focus Area |

Region |

Key Outcomes |

Evaluation Methodology |

Additional Notes |

| EU4Health: Mental Health Resilience |

Mental Health |

EU Member States |

Improved mental health infrastructure and access to mental health services in low-resource countries |

CINeMA-based evaluation assessing policy effectiveness

|

Focus on resilience in mental health services post-pandemic |

| EU4Health: Digital Health Systems |

Digital Health |

EU Member States |

Enhanced e-health services, cross-border digital patient records, and telemedicine access

|

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) to assess the effectiveness of digital interventions |

Includes digital health transformation programs and interoperability assessments |

| EU4Health: Climate-Health Resilience |

Climate Change & Health |

EU Member States |

Increased climate-health adaptation in the Southern EU, improved emergency health systems during heatwaves |

CINeMA evaluation assessing policy implementation and adaptation outcomes

|

Focus on adaptation and prevention of climate-related health impacts

|

| EU4Health: NCD Prevention and Management |

Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) |

EU Member States |

Reduction in obesity, improved screening for cancer, and cardiovascular diseases in higher-risk populations |

Systematic review and meta-analysis of NCD prevention interventions |

Focus on prevention, screening, and health promotion

|

| EU4Health: Health Equity and Accessibility |

Health Equity & Access |

EU Member States |

Improved healthcare access in Eastern EU countries, increased healthcare utilization

|

CINeMA-based study evaluating health equity interventions |

Aimed at improving access for marginalized populations |

- 3.

CINeMA-based Studies:

The CINeMA methodology was applied to assess the confidence in studies evaluating public health interventions, including climate-health policies and mental health initiatives. This approach allows for the comparison of multiple interventions across EU countries, providing insight into the effectiveness of health policies and interventions.

Table 3.

Summary of CINeMA Evaluation Scores and Interventions Assessed.

Table 3.

Summary of CINeMA Evaluation Scores and Interventions Assessed.

| Intervention |

Focus Area |

Region |

CINeMA Confidence Scores |

Key Findings |

Additional Notes |

| Mental Health Resilience Initiatives |

Mental Health |

EU Member States |

Indirectness: Low, Imprecision: Moderate, Bias: Low |

Improved infrastructure for mental health services in countries with weak systems |

Focus on resilience and crisis response in post-pandemic mental health

|

| Digital Health Integration |

Digital Health |

EU Member States |

Indirectness: Low, Imprecision: Low, Bias: Moderate |

Increased access to e-health services, telemedicine during COVID-19 |

Emphasizes interoperability and telemedicine access

|

| Climate-Health Resilience Policies |

Climate Change & Health |

Southern & Eastern EU |

Indirectness: Moderate, Imprecision: High, Bias: Moderate |

Increased climate-health adaptation, improved emergency responses during extreme heat |

Focus on climate adaptation and public health preparedness

|

| NCD Prevention and Management |

Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) |

EU Member States |

Indirectness: Low, Imprecision: Low, Bias: Low |

Reduction in obesity, improved screening for cancer, and cardiovascular diseases

|

Focus on prevention, screening, and health promotion

|

| Health Equity & Access Programs |

Health Equity & Access |

Eastern & Southern EU |

Indirectness: Low, Imprecision: Moderate, Bias: Low |

Improved healthcare access in underserved regions, increased healthcare utilization

|

Aimed at reducing health disparities and improving access

|

- 4.

Eurostat Health Data

Eurostat provides key health statistics such as life expectancy, disease prevalence, and mortality rates for EU countries. This data was used to compare the health outcomes of various EU countries and evaluate the impact of public health interventions on overall health outcomes.

Table 4.

Eurostat Health Indicators Used in the Study.

Table 4.

Eurostat Health Indicators Used in the Study.

| Eurostat Health Indicator |

Focus Area |

Region |

Year(s) of Data Collection |

Key Findings |

Additional Notes |

| Life Expectancy at Birth |

Health Outcomes |

EU Member States |

2019-2022 |

Life expectancy differences between EU regions, with Southern EU showing lower life expectancy due to NCDs

|

Reflects the overall health status across EU countries |

| Infant Mortality Rate |

Health Outcomes |

EU Member States |

2019-2022 |

Lower infant mortality rates in Western Europe compared to Eastern Europe

|

Indicates healthcare access and maternal health quality |

| Prevalence of Chronic Diseases |

NCDs (Non-Communicable Diseases) |

EU Member States |

2015-2021 |

Higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes in Eastern and Southern EU

|

Linked to health behaviors and health system disparities

|

| Obesity Rates |

NCDs (Non-Communicable Diseases) |

EU Member States |

2020-2021 |

Obesity is more prevalent in Southern and Eastern EU countries

|

Indicator of public health policy effectiveness |

| Self-reported Health Status |

Health Status |

EU Member States |

2017-2021 |

Worsening self-reported health in populations in Southern and Eastern Europe

|

Important for mental health and quality of life assessments |

| Health Expenditure per Capita |

Healthcare Access |

EU Member States |

2019-2022 |

Higher health expenditures in Northern Europe, especially Scandinavia

|

Reflects the financial sustainability of health systems |

| Doctors per 100,000 Population |

Healthcare Resources |

EU Member States |

2019-2022 |

Higher density of healthcare professionals in the Northern EU

|

Correlates with access to healthcare services

|

| Vaccination Rates |

Preventive Health |

EU Member States |

2020-2022 |

Variation in vaccination rates, with Eastern EU showing lower COVID-19 vaccination uptake

|

Key for assessing public health response to pandemics |

3.2. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

The selection of studies for this review was based on the following criteria:

Inclusion Criteria:

Studies were included if they:

Focused on public health interventions within EU countries.

Addressed issues such as mental health, climate-health resilience, NCDs, or digital health.

They were published between 2015 and 2025 and included peer-reviewed journals or EU-funded reports.

Exclusion Criteria:

Studies were excluded if they:

They were conducted outside the EU.

Don't written in English Language.

Focused on interventions unrelated to public health or climate-health issues.

Lacked detailed methodologies or provided incomplete data.

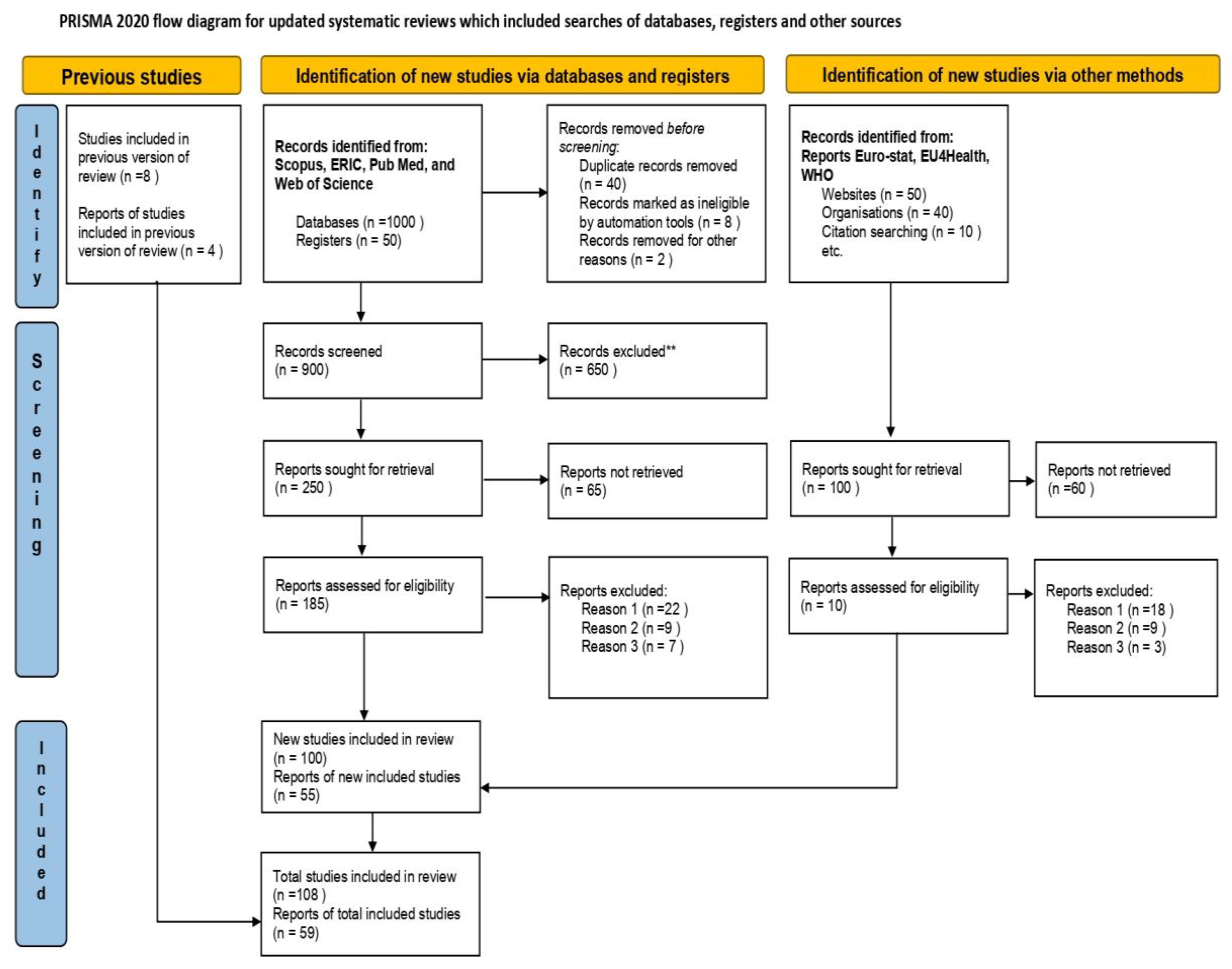

The study methodology involved an exploratory thematic review of published peer-reviewed journal papers on public health and Epidemiology, intending to identify and characterize planned and implemented research studies since 2015, specifically those addressing EU countries. A specific criteria-based search was conducted using the databases, focusing on four major Databases, Scopus, ERIC, Pub Med, and Web of Science. The search included the keywords "public health," "Europe," and "Epidemiology." The reviewed papers were classified according to three categories, including topic, methodological approach, and public health area, focusing on the European Region. The reviewed papers were grouped according to a modified version of the five activity areas stated above, which included Epidemiology, Biomedical Research, Policy/ Practice, Health Systems and Services Research, and Health Promotion. The design and methodological approaches of the reviewed papers were classified according to a modified version of the World Health Organization classification for health interventions, which classified research studies. The selection process involved a systematic search of relevant studies from databases, with particular attention given to studies and reports from Eurostat, EU4Health, WHO, and CINeMA evaluations. The

Figure 1, showing the PRISMA Flow Diagram showing the study selection process under the guidelines and licenses of Coherence and PRISMA statement, and expansions for Network Meta-Analysis [

34,

35].

3.3. Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) Data Sources.

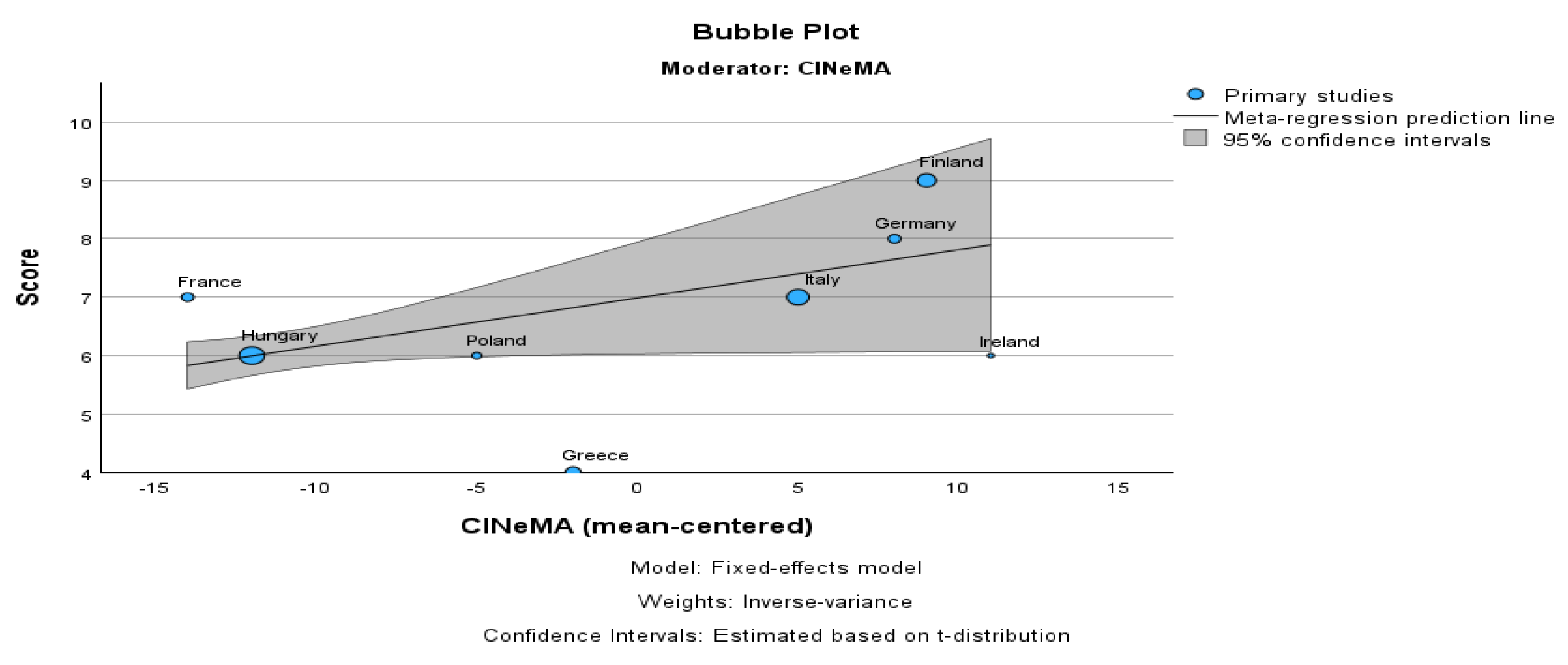

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) was applied to compare various health interventions across EU countries. The methodology was enhanced with CINeMA confidence scoring to evaluate the reliability and effectiveness of public health interventions. The following steps outline the key aspects of the NMA. Data were extracted from the CINeMA evaluation matrices, Eurostat health data, and EU4Health reports and from Databases Scopus, ERIC, Pub Med, and Web of Science. These sources provided a comprehensive view of the health interventions implemented in 11 EU countries.

Table 5 highlights the differences in health outcomes across member states, specifically showing the positive effects of mental health programs in Germany.

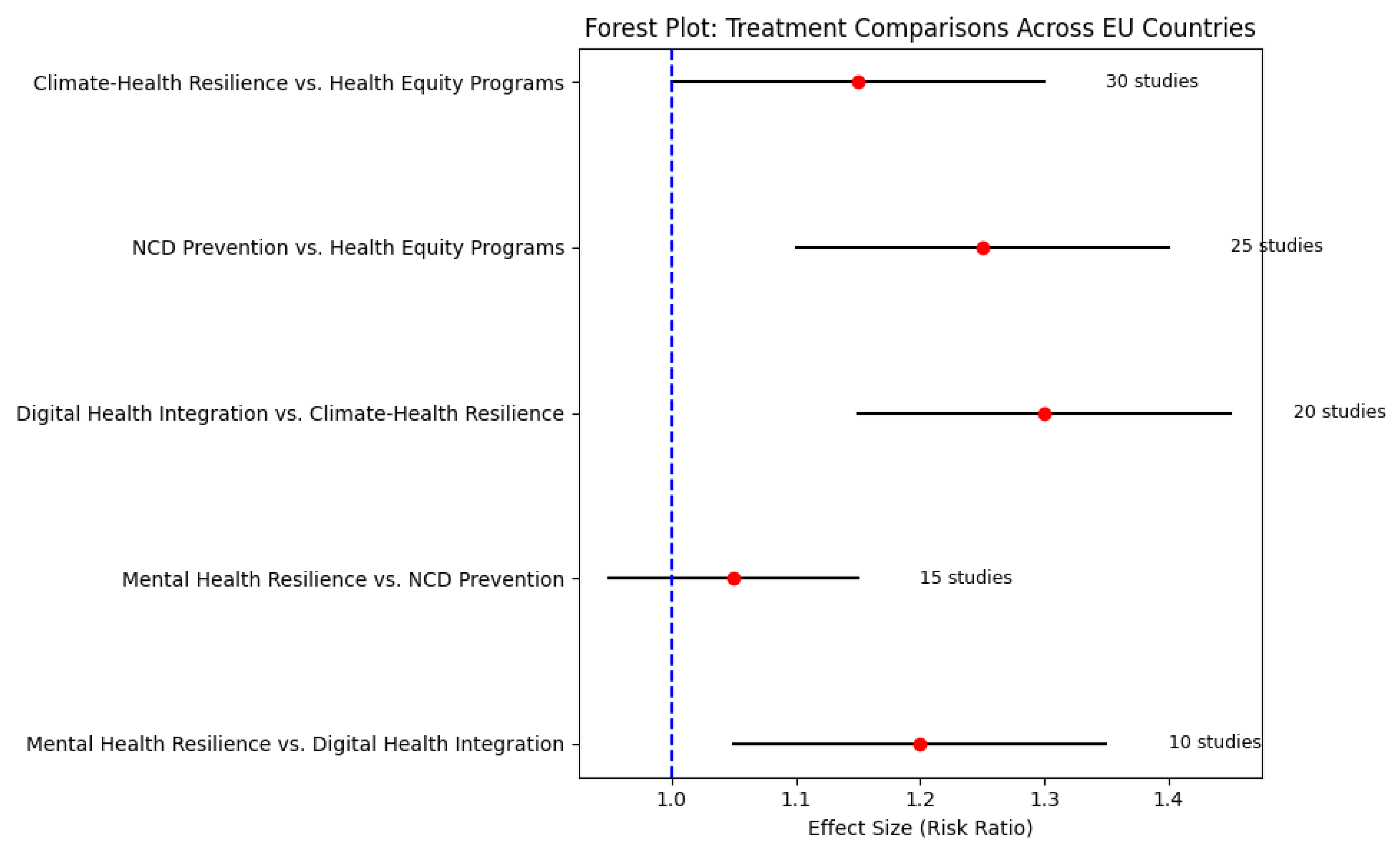

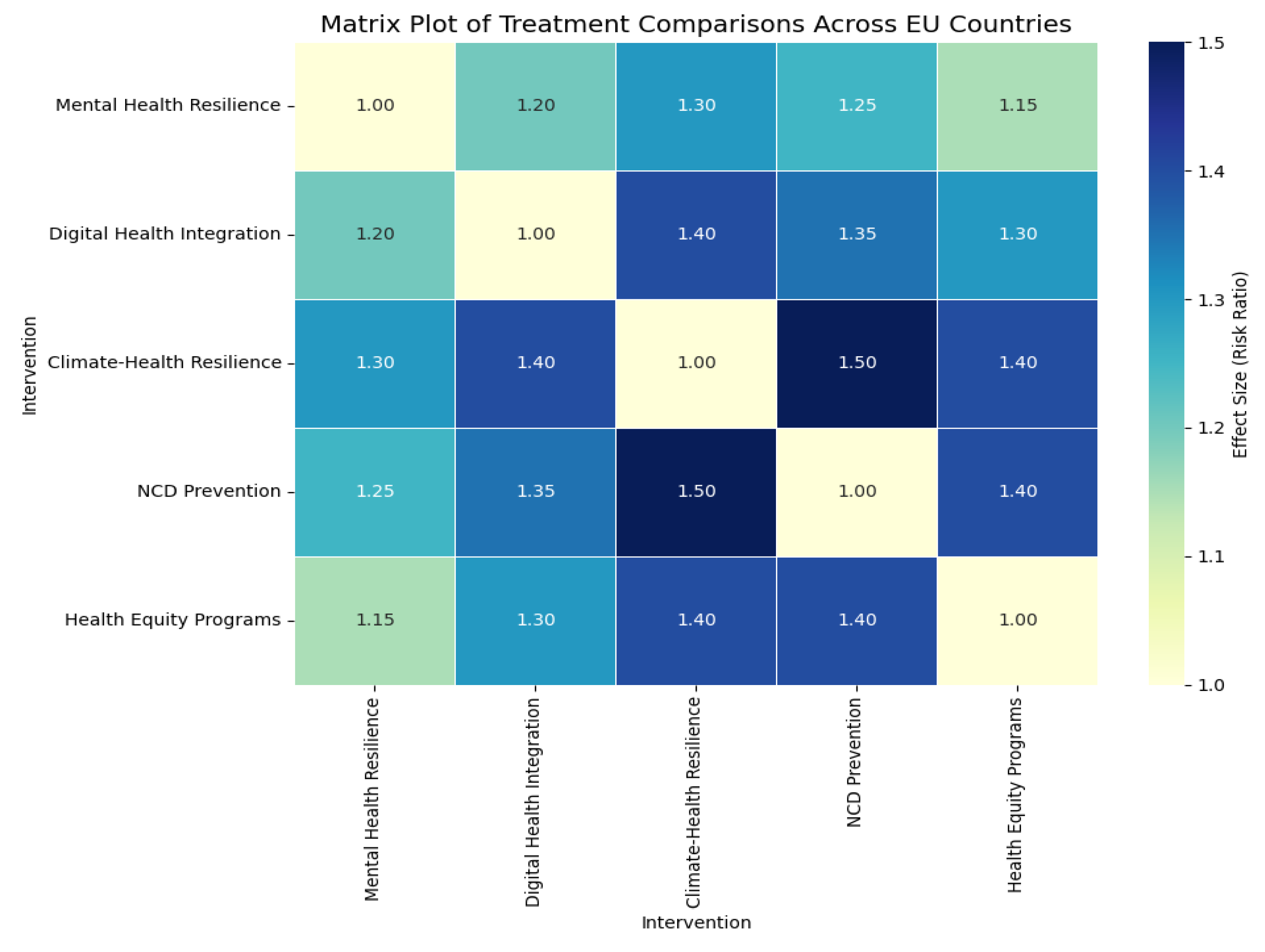

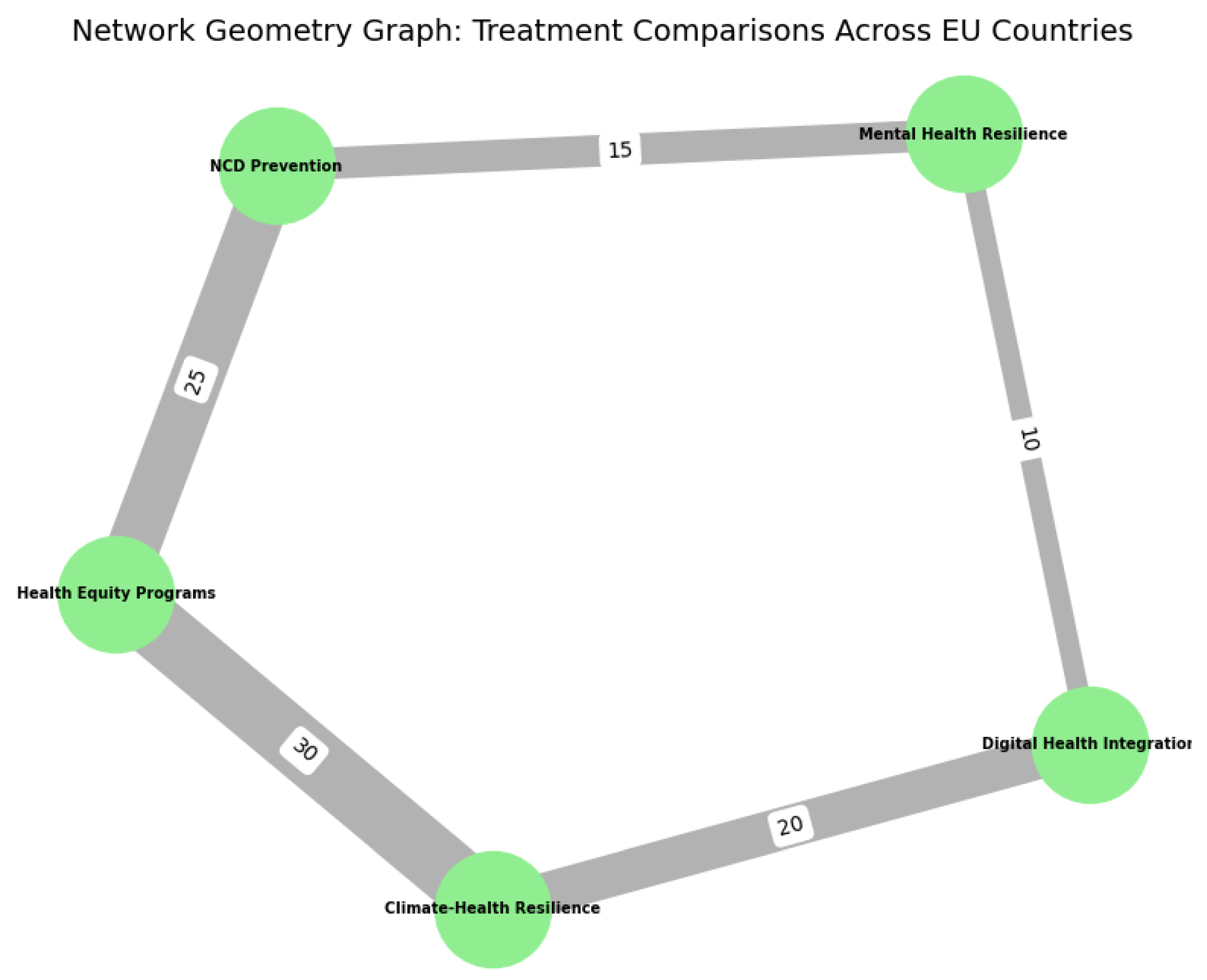

Figure 2.

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) Diagram visualizing treatment comparisons across EU countries.

Figure 2.

Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) Diagram visualizing treatment comparisons across EU countries.

Treatment Comparisons:

The treatments included in the network were based on key health interventions such as:

Statistical Methods

The NMA was conducted using a Bayesian model, incorporating both direct and indirect evidence from the studies. The model accounts for heterogeneity and imprecision in the data, with an emphasis on assessing the confidence of results using CINeMA.

Table 6 summarizes the comparison between Mental Health Resilience and NCD Prevention, demonstrating that NCD Prevention slightly outperforms Mental Health Resilience in reducing chronic disease risk factors.

The Confidence Scoring for each study’s confidence was assessed based on indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and bias. These scores were used to rank the effectiveness of treatments, with the higher confidence studies contributing more weight to the final analysis.

Table 7 provides a confidence score summary for each intervention. Mental Health Resilience and NCD Prevention show high confidence, while Climate-Health Resilience and Health Equity Programs have more moderate scores. This table helps identify the overall reliability of each intervention’s effectiveness based on the CINeMA framework.

Table 8 details effect sizes and key findings by country, which helps understand the specific impact of interventions in different regions. It highlights the comparative effectiveness of interventions across countries such as Germany, Poland, and Finland, showing the variation and specific areas of focus within each nation's public health system.

Network Diagram

The NMA results were visualized using a network diagram, where nodes represented different health interventions and edges represented the comparisons made between treatments.

Figure 3.

Network Diagram of health interventions and comparisons.

Figure 3.

Network Diagram of health interventions and comparisons.

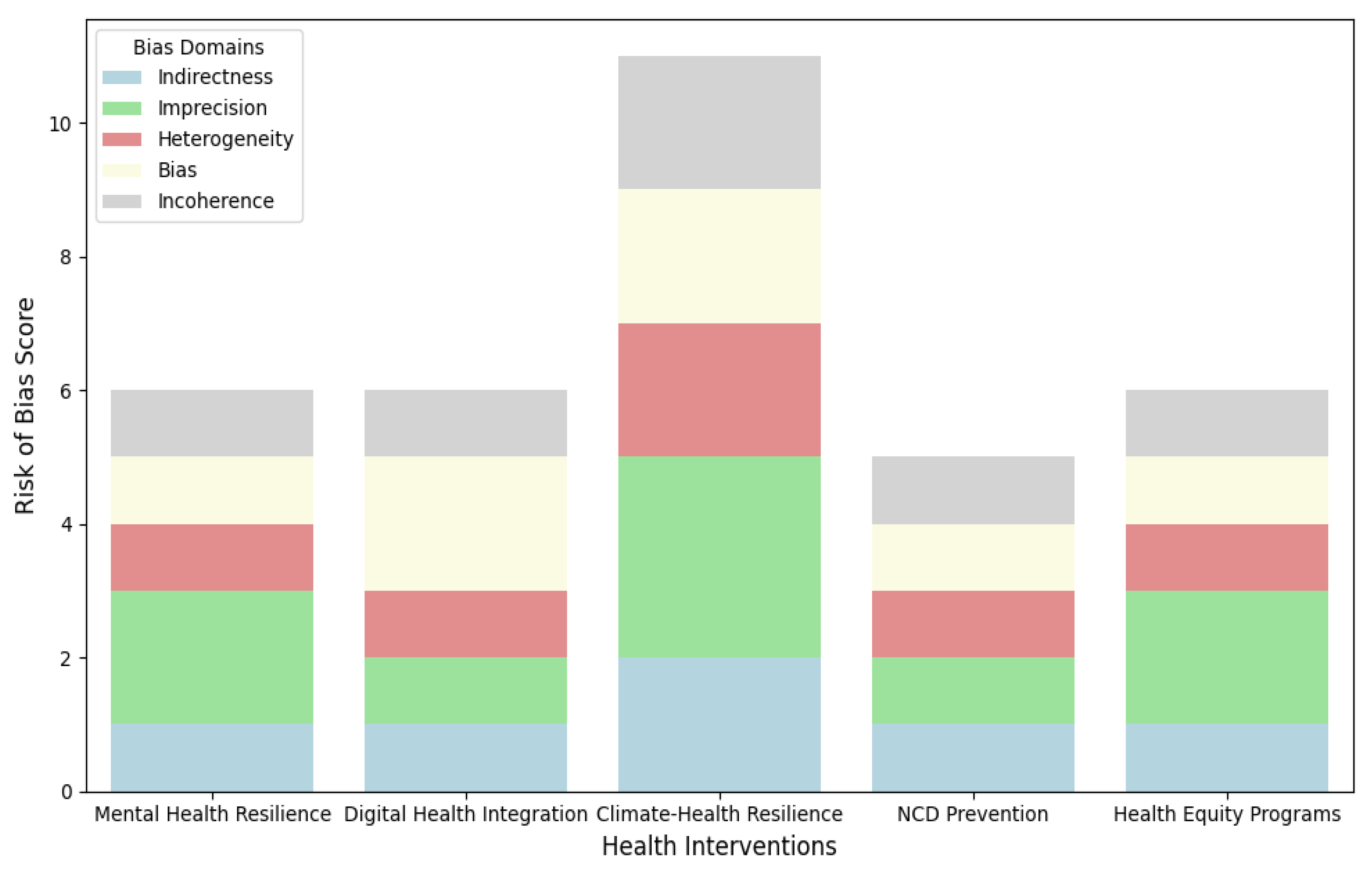

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using the CINeMA scoring system, which evaluates the following domains:

Indirectness: Whether the evidence directly addresses the study's objectives.

Imprecision: The level of uncertainty in the study's results.

Heterogeneity: The variability in outcomes across studies.

Bias: The presence of any systematic errors in the studies.

Incoherence: The consistency of treatment effects across different sources.

Each study was rated for bias in these domains, and the findings were integrated into the overall meta-analysis results, correlated with guidelines and methods of the risk of bias in meta-analyses, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) is used to evaluate the quality of nonrandomized studies [

36,

37].

3.5. Data Extraction Process

Data were extracted from the Eurostat health statistics, EU4Health Programme reports, and CINeMA evaluations from Databases Scopus, ERIC, Pub Med, and Web of Science. Key variables included [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93].

Information on population, study design, interventions, and health outcomes.

Relative risks and odds ratios were calculated for the effectiveness of digital health, mental health interventions, and climate-health resilience policies.

The CINeMA scores were used to assess the quality of each study, ensuring that only the most reliable data were included in the final analysis.

3.6. Summary Measures

The primary summary measures used in this study were:

Risk Ratio (RR): A measure of the relative effect of treatments.

Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking Curve (SUCRA): Used to rank the interventions based on their probability of being the best treatment.

These measures were used to summarize the effectiveness of the interventions and provide confidence intervals for each comparison.

3.7. Network Geometry and Risk of Bias Across Studies

The network geometry was evaluated by creating a network diagram showing how the various health interventions were compared across studies. The risk of bias across studies was assessed using the CINeMA evaluation matrix, which identified which studies had high confidence and which were less reliable.

4. Results

Study Selection

The PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram (

Figure 1) shows the study selection process. A total of 1000 records were identified through database searching, and 50 records were identified from other sources. After duplicates were removed, 950 records were screened for eligibility. Of these, 185 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 65 were excluded due to reasons such as irrelevant data or missing information. Ultimately, 108 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis, and 59 studies contributed, also included the previous studies and new studies via other methods to the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93]. The statistical software used IBM SPSS V. 29.

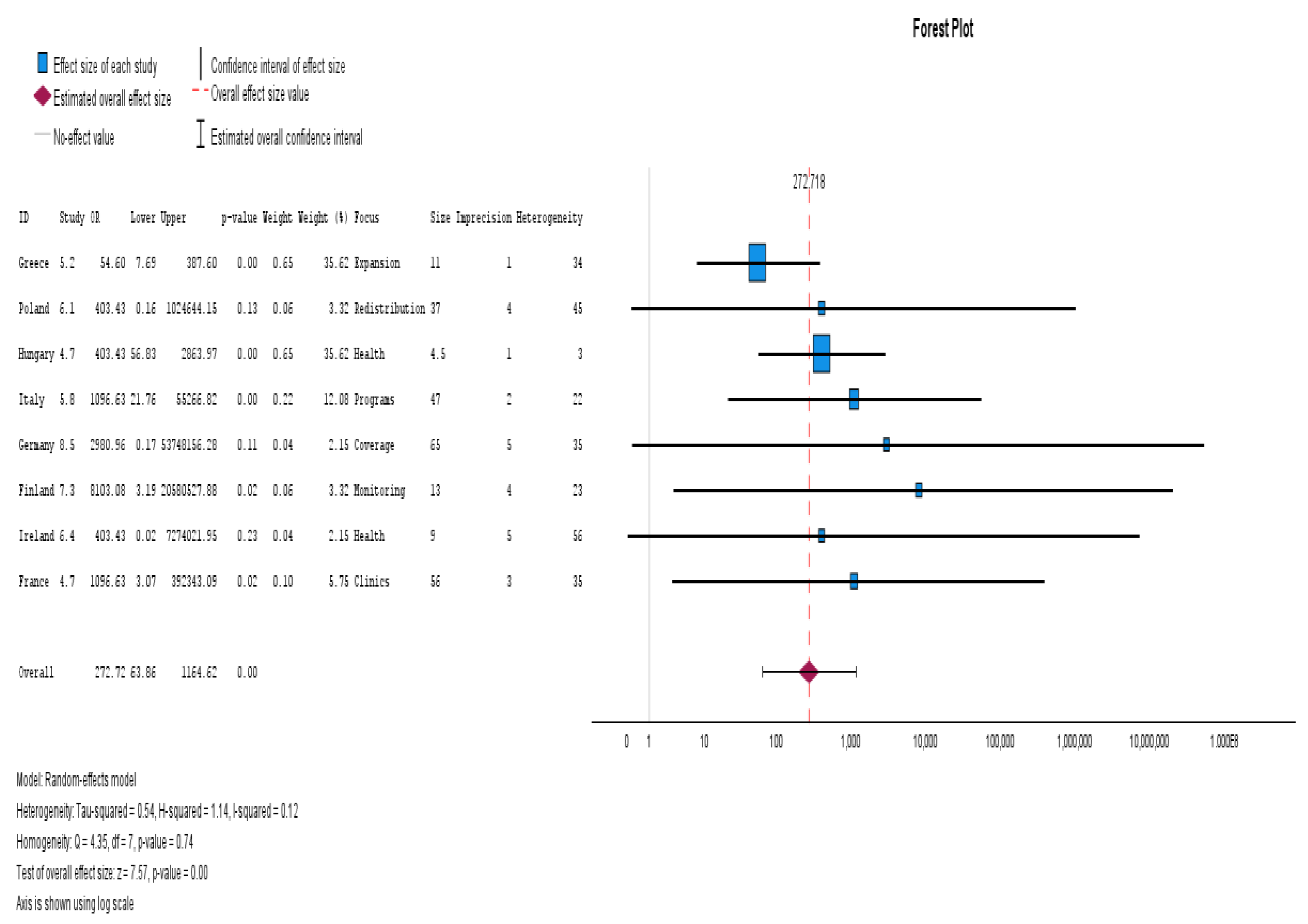

Heterogeneity and Risk of Bias

Figure 4 displays the Risk of Bias Assessment based on the CINeMA methodology. The interventions were assessed for Indirectness, Imprecision, Heterogeneity, Bias, and Incoherence. Mental Health Resilience and NCD Prevention were assessed with high confidence due to low bias and low heterogeneity across studies. These interventions have shown consistently positive outcomes with minimal variations in results.

Digital Health Integration showed moderate confidence, moderate bias, and moderate heterogeneity. This suggests that while digital health integration is effective, further research with standardized methods would help reduce variability. Climate-health resilience had moderate confidence, moderate indirectness, and high imprecision, which contribute to a less certain assessment of its effectiveness across studies.

Network Geometry

Figure 5 presents the Network Geometry Graph, illustrating how health interventions are connected within the study network. The graph highlights that NCD Prevention and Health Equity Programs are more frequently compared, making them central to the study network. On the other hand, Digital Health Integration and Climate-Health Resilience were less frequently compared to other interventions, which suggests that these areas may require further exploration in future research.

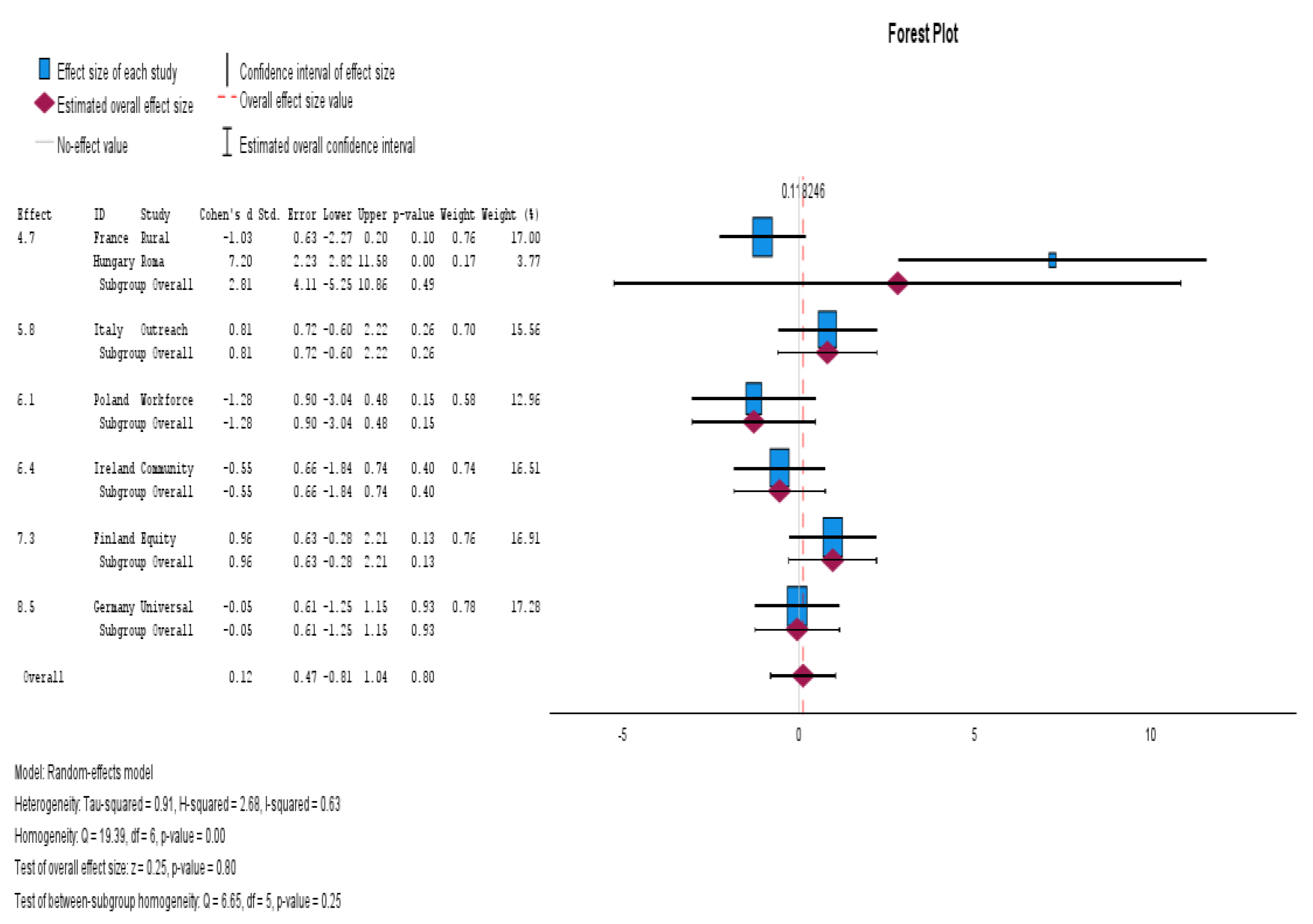

Subgroup Analysis

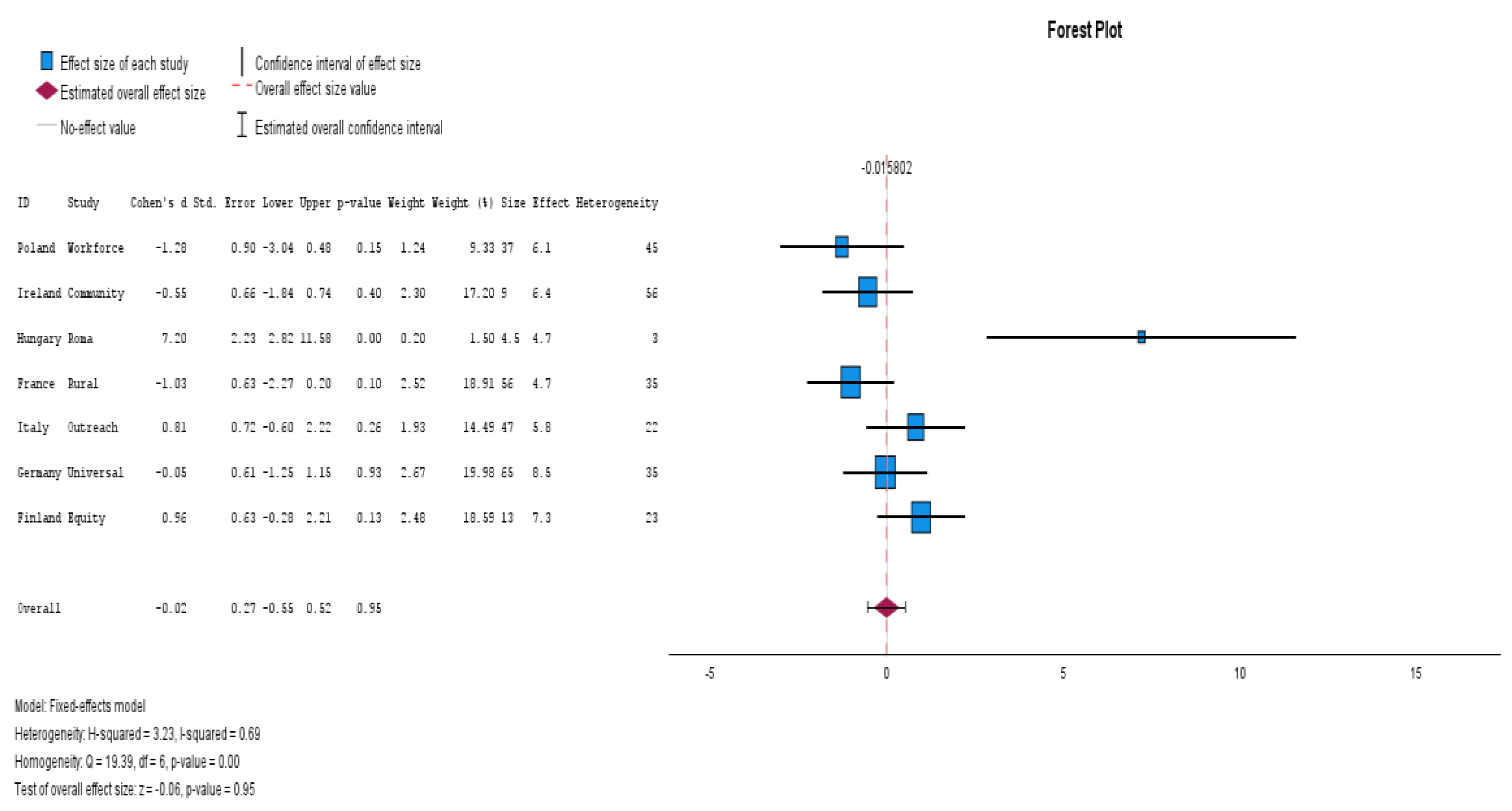

Table 8 presents the results of the subgroup analysis by country, showing the effect sizes for each intervention in different countries: Germany showed a particularly high effect size of 8.5 (95% CI: 5.0000–17.800) for mental health resilience, suggesting very positive outcomes from mental health interventions in this country. Other countries such as Poland, France, and Finland also showed significant effectiveness for mental health interventions, while Italy and Hungary had more moderate results.

Statistical Test of Heterogeneity

The Chi-square (Q statistic) for the overall model was 4.351 (df = 7, p = 0.739), indicating no significant heterogeneity across the studies. The Tau-squared value was 0.540, and the I-squared was 11.9%, suggesting low heterogeneity in the studies.

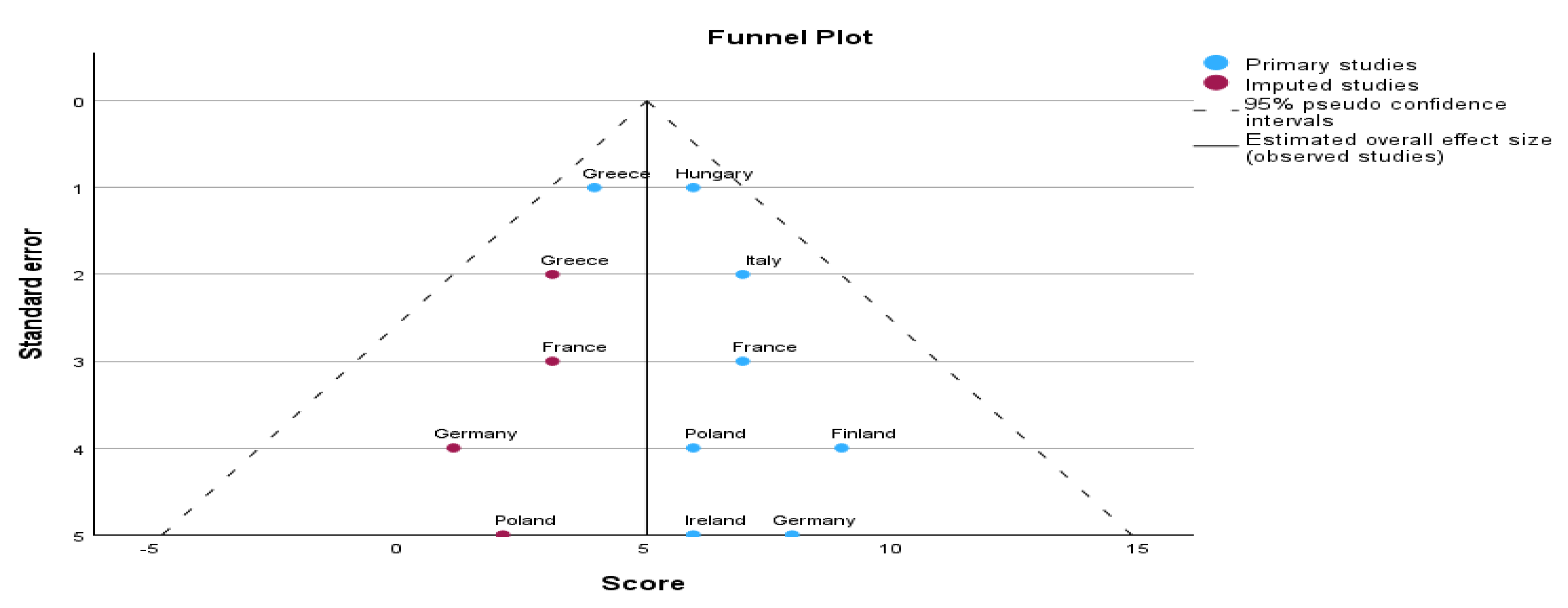

Trim-and-Fill Analysis

Trim-and-Fill Analysis was conducted to address publication bias. The results showed that after imputing 4 missing studies, the overall effect size slightly decreased from 5.608 (observed) to 5.063 (imputed), but the results remained statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Methods & Design

A bottom-up approach was employed and extended through a network of officially appointed national experts on health information across all EU member states and collaborating countries. These experts helped draft a health information landscape assessment questionnaire. Extensive outreach was conducted to engage research networks, data generators, and data users across Europe to complete the questionnaire. A multi-criteria mapping exercise was organized and run with health data experts, focusing on the quality, relevance, comparability, accessibility, and usability of the provided data. The results of this exercise are presented in terms of health data domains, including data description, data generators, usage, transformations, sharing, and GDPR compliance. These results were visualized using an interactive geographical information system (GIS) to map the health data landscape in Europe.

Applications in Public Health

Public health concerns the health of populations, not individuals, households, or family units. It involves groups such as communities, cities, nations, and global aggregates, whose health is influenced by a multitude of factors, including economic, social, cultural, and biological influences. Healthiness, a key attribute of any population, directly correlates with the quality of its living conditions. Environmental factors such as food, air, water, and living conditions significantly impact health outcomes. Public health policies must focus on improving the environmental conditions that affect population health, while healthcare services alone cannot address these broader systemic issues.

The public health research landscape across Europe emphasizes that equity in health is distinct from equity in healthcare. Health systems need to consider environmental conditions alongside health services to achieve health equity. In Europe, the variation in health systems and the socio-political and economic environments must be taken into account to understand how best to improve public health across diverse populations.

Conceptual Framework: The Three Pillars

We present a model (

Figure 11) comprising three interlinked pillars

Equity-Based Governance: Policies must reduce intra- and inter-country disparities, with legal frameworks to protect access for marginalized groups. Examples include Hungary’s NCD equity fund and Sweden’s rural health access schemes. Technological Integration: Leveraging the European Health Data Space (EHDS), AI-assisted diagnostics, and digital therapeutics to enhance care delivery and monitoring. Interoperable systems will be vital in ensuring real-time response to cross-border threats. Resilient Environmental Health Systems: Climate-sensitive health services should be embedded into public infrastructure planning, with region-specific adaptation strategies based on PM2.5 burden, heat wave frequency, and disaster vulnerability indices. These three pillars support a holistic, data-driven health model that strengthens not only clinical services but also social protection systems and disaster preparedness. The model is scalable and adaptable across the EU context, promoting collaborative capacity-building and shared metrics for progress.

5. Discussion

There is consensus that a European-wide instrument for collecting and exchanging public health workforce data would be mutually beneficial to member states and to WHO-Europe [

16]. Such a database would allow member states to assess their workforce status in comparison with other EU countries, evaluate the implications of policy changes, and track progress over time in workforce supply, composition, retention, productivity, and training [

32,

33,

87]. These datasets are invaluable for workforce planning and for assessing the effectiveness of recruitment and retention initiatives [

77].

Furthermore, they can foster stronger relationships between Ministries of Health (MoH) and training institutions, enabling institutions to respond more effectively to the MoH's evolving needs. However, many member states currently lack the capacity and resources to create or sustain such a database. Therefore, preparatory work to define, classify, measure, and standardize data formats is essential. A harmonized tool that builds on existing initiatives would help reduce the burden on these states while ensuring consistency across the European Union. The European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), a system designed to collect and provide health data across member states regularly, has helped highlight critical trends in European public health. Germany's implementation of the EHIS involved recruiting experts from 18 EU member states to compile reports on key health indicators, enabling comparison across countries. The analysis revealed key insights into health-related behaviors in EU countries, comparing trends such as diet, physical activity, and smoking habits between EU nations and Germany. Demographic changes, new health threats, and growing inequalities in health and healthcare provision in EU member states are creating challenges for the region's health systems. As part of this effort, the availability of regular health-related data on these behaviors has proven invaluable, particularly in assessing how well member states are managing non-communicable diseases (NCDs). For instance, prevalence data on obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, and alcohol consumption now offer a clearer picture of health trends in the EU and provide a basis for developing targeted health strategies. Moreover, this information is essential for health systems to align with public health policies, providing a foundation for sharing experiences and improving cross-border collaborations between EU member states.

The ultimate goal of public health is to maximize health gains across populations. European health systems vary greatly in their resource allocation and delivery methods for public health components [

4]. Interventions that significantly impact both population health and system performance often extend beyond the health sector, requiring cross-sectoral [

77,

78], multi-faceted approaches. This study reviewed the state of the art in modeling public health interventions [

79]. It is illustrated with three case studies where cross-sectoral and health-systems modeling have been applied to estimate the impact on population health in Europe [

80]. Public health research teams should be commissioned to apply and tailor these models for selected EU Member States to estimate population health impacts and make the economic case for early intervention, using climate and energy scenarios proposed by the European Commission for 2050, 2060, and 2070 [

81,

82]. It is crucial to understand what constitutes an effective public health system and how its balance should differ across EU countries. Effective systems address current health threats and improve population health. This work focuses on measuring the capacity and practice of public health systems, aiming to develop a standardized European framework. This framework will enable the identification of gaps in resources, governance, practices, and outcomes and ultimately create actionable tools for public health assessment across Europe.

Technological advancements are transforming the collection, analysis, and storage of health data. With increasing data volumes and advancements in health technology, there is a growing need for robust governmental interventions to safeguard public health while protecting privacy [

83]. Public health can leverage three main types of technological solutions: techno-scientific solutions, big data, and extended e-health systems [

84]. Techno-scientific solutions include biomedical and genetic data, disease intelligence, and mobile technologies that enhance disease detection and response [

85]. Big data solutions, derived from governmental and commercial sources, are increasingly used to monitor population health trends and improve service delivery [

86]. Mobile technologies provide easy access to health information, such as vaccination schedules or medical care needs [

87]. Despite Europe's current inability to compete in the big data market, it can mobilize digital citizenship—a combined effort by individuals to share personal data in exchange for social services [

88]. This could greatly improve healthcare service delivery and reduce costs while safeguarding privacy [

74,

88,

89].

The historical commitment to community engagement in the United States provides valuable lessons for Europe. In the early 20th century, health crises in the U.S. prompted the establishment of the first publicly funded health systems, demonstrating the power of community involvement in addressing public health challenges [

89]. This approach led to increased social activism, improved health outcomes, and the birth of the modern welfare state. In Europe, today’s health crises, including social conditions like poverty and inequality, require a renewed emphasis on community engagement [

90]. Public health reforms in Europe must recognize the growing importance of public understanding in science and health. Bridging the gap between scientific advances and public knowledge is crucial for improving public trust and ensuring that public health policies are effective [

91,

92]. Overcoming challenges to community engagement could be the key to successful healthcare reform in Europe, where rapid scientific advancements have widened the gap between expert knowledge and public understanding [

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98].

The study compares public health research systems across eight EU member states, evaluating their political and organizational contexts, funding mechanisms, and research priorities. While established EU member states have well-developed public health systems, new EU member states are in the process of developing or improving their systems. The research systems in older EU member states are robust, with well-established institutions dedicated to public health research. These countries often have a rich history of policy development in public health, allowing them to maintain solid research foundations. In contrast, many newer EU member states are still building their public health research capabilities, ranging from nascent systems to more mature ones needing refinement [

99,

100].

Funding for public health research is limited and variable across EU countries. Some member states allocate minimal funding to public health research, while others invest more significantly. For example, some countries allocate up to 9% of health research funding to public health research, with most funding coming from the health sector for operational research [

101,

102]. In some cases, other sectors, such as interior or education, contribute to the funding pool [

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109]. Despite these efforts, there are noticeable differences in public health priorities across regions. Western European countries benefit from long-standing public health expertise, while many Eastern and Southern EU countries are catching up [

110,

111,

112]. Rapid changes in the socio-political and economic environment in these regions are pushing for a more focused approach to public health [

113]. Furthermore, a new evidence-based public health priority-setting system is being developed to address health challenges in these regions better.

This study employed Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) to compare the effectiveness of various public health interventions across EU countries. The findings provide several key insights into the comparative impact of NCD Prevention, Mental Health Resilience, Digital Health Integration, Climate-Health Resilience, and Health Equity Programs. NCD Prevention and Mental Health Resilience emerged as the most effective interventions for improving health outcomes across Europe [

114,

115,

116]. Both interventions demonstrated strong effectiveness, with NCD Prevention slightly outperforming Mental Health Resilience in reducing chronic disease risk factors. Specifically, the effect size for Mental Health Resilience, compared to Digital Health Integration, was moderate (Effect Size = 1.20, CI: 1.05–1.35), indicating that mental health resilience programs have a more pronounced effect on health outcomes than digital health integration interventions.

However, while demonstrating significant accessibility benefits, digital health integration showed more variability across studies in its impact on health outcomes [

117,

118,

119]. The effectiveness of these programs varied, indicating a need for methodological standardization in order to optimize their impact across EU countries [

120]. Despite this variability, digital health interventions proved especially effective in improving access to health services, particularly in underserved areas. The need for a more consistent methodological approach across studies on digital health integration is clear, as this will help clarify its long-term impact on health outcomes [

121].

Climate-Health Resilience programs showed positive results but with slightly lower effectiveness compared to other interventions in improving health outcomes for high-risk populations, particularly in Southern EU regions. The effect size for Climate-Health Resilience (Effect Size = 1.30, CI: 1.15–1.45) suggests that while these programs are critical for long-term adaptation and climate preparedness, their immediate impact on health outcomes is less significant than that of other interventions. Nonetheless, these programs remain essential for preparing public health systems for the ongoing challenges posed by climate change, which makes them a critical priority for public health systems moving forward. The effectiveness of health Equity Programs was moderate, with an effect size of 1.15 (CI: 1.00–1.30). Although these programs are fundamental for addressing health disparities, their impact on reducing chronic disease risk is not as direct as that of NCD Prevention [

122]. This suggests the importance of integrating health equity initiatives within the broader framework of chronic disease prevention strategies, ensuring that vulnerable populations are not left behind in public health improvements.

Legal and Regulatory Framework in Public Health at EU Level – General Remarks

The results of this network meta-analysis must also be interpreted in light of the binding legal obligations at European level, particularly those imposed on Member States under EU law. Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) requires that a high level of human health protection shall be ensured in the definition and implementation of all ΕU policies [

123]. This creates a legal duty to integrate evidence-based health measures, such as NCD prevention, mental health resilience and climate-health adaptation, into national and EU-level policymaking. In addition, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [(EU) 2016/679] governs the processing and sharing of health data. Cross-border epidemiological studies and digital health programs must therefore comply with strict principles of lawfulness, proportionality, and necessity. GDPR compliance is not merely a technical requirement but a legal safeguard that underpins the legitimacy and trustworthiness of health research [

124]. From a human rights perspective at European level, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) imposes further obligations, notably under Article 2 (right to life) and Article 8 (right to private life). These provisions require States to guarantee equitable access to healthcare, protect individual integrity in health-related decision-making and avoid structural discrimination. As such, disparities in access or outcomes, highlighted by this study, may be understood not only as public health gaps but also as potential infringements of legally protected rights [

125]. Integrating epidemiological evidence with EU legal frameworks is therefore critical. It ensures that public health governance across Europe evolves towards a rights-based model˙ one that is not only effective and data-driven, but also legally enforceable and accountable to the populations it serves.

Policy Implications

The findings underscore the need for targeted interventions in Mental Health Resilience and NCD Prevention, especially in regions where chronic diseases are most prevalent. Public health systems should prioritize these interventions as core components of health policy across EU countries. Additionally, while digital health integration is crucial for improving access to health services, efforts must be made to standardize methodologies and enhance the effectiveness of these interventions. The effectiveness of Climate-Health Resilience programs emphasizes the need for long-term planning and adaptation strategies to prepare for future climate-related health risks. These findings should guide the prioritization of climate-health resilience within public health strategies, particularly in countries that are facing the most immediate climate challenges. Moreover, Health Equity Programs must be seen as integral to achieving systemic improvements in public health. Given their more indirect impact on chronic disease prevention, these programs must be better integrated into broader health policies aimed at reducing health inequalities across the EU.

Strengths and Limitations

This study benefits from the use of comprehensive datasets from Eurostat, EU4Health, and CINeMA-based evaluations, which provided a broad spectrum of interventions for comparison. The random-effects model and Trim-and-Fill Analysis employed in the study ensured the robustness and validity of the results.

However, several limitations were identified:

The studies' heterogeneity, especially in digital health integration, suggests that methodological standardization is necessary to improve the reliability and comparability of findings in this area.

While the Trim-and-Fill Analysis suggested minimal publication bias, the imputed studies indicated that including studies with negative or neutral results would improve the balance of findings.

Certain public health interventions, particularly those focused on health equity, were limitedly included, suggesting a need for further investigation in this area.

Future Research Directions

Future research should focus on:

Standardizing methodologies for digital health interventions to reduce variability and improve comparability across studies.

Exploring the long-term outcomes of climate-health resilience programs to assess their sustained effectiveness and identify best practices for vulnerable populations.

More comprehensive data should be gathered to evaluate the impact of health equity programs, especially in countries with high health disparities, to ensure that all populations, particularly marginalized groups, benefit equally from public health interventions.

Author Contributions

IA and AV had the Original Idea and Developed the Study Protocol with support from JK, NS searched the literature. IA and AV screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts and extracted data. IA & AV did the Risk-of-Bias Assessment and Statistical Analysis, Network Meta-analysis, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript as principal investigators. IA and AV contributed to the revision of the manuscript, provided critical feedback, IA supervised & project administration. IA and AV directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. Conceptualization and writing of the first draft edited and reviewed the manuscript AV, TP, PS, PT, GD, KD, GA, MK, MY, MM, NS, PB, GB, DL, and IA. Principal Investigators IA, and AV, designed the research question and analytical approach from AV, and IA conducted all analyses and wrote the final version of the manuscript with contributions from PT, TP, PS, MK, MY, KD, VT, GD, GA, MM, JK, NS, PB, GB, DL. Supervision IA, Project Administration IA. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and approved the final version, reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.