1. Introduction

Severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) or hyperbilirubinemia is responsible for estimated 114,100 neonatal deaths annually [

1]. A further 75,000 newborns survive yet will suffer from kernicterus spectrum disorder (KSD) for the remainder of their lives [

2] - a chronic condition characterised by motor dysfunction and oculomotor and auditory impairment [

3]. The majority of these incidents occur in lower middle income countries (LMIC) particularly in Sub Saharan Africa, South Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean [

4]. The systematic review and meta – analysis by Slusher et al. [

5] concludes that high income countries experience an incidence rate of SNJ at 3.7 per 10,000 while LMIC’s experience an incidence rate at 244.1 per 10,000. This disparity represents the highly treatable nature of SNJ [

6] if the access to the technology, resources and training is provided [

7]. Current technology available for treatment of SNJ is manufactured in and intended to serve a high-income consumer base where sales margins are highest as shown in

Table 1.

This means the technology is not only cost prohibitive to purchase by LMIC’s but access to repair of these devices is also challenging [

13] leading to the proliferation of ‘medical equipment graveyards’ filled with devices not in service [

14].

One method to overcome this challenge is the design and digital distributed manufacturing of open source medical devices [

15,

16], which was somewhat normalized in response to the COVID19 pandemic [

17]. The best practices for open hardware [

18,

19] involve designing hardware that can be easily replicated in a wide-range of contexts with low cost digital manufacturing tools like open-source RepRap-class 3-D printers [

20,

21], open-source autoinjectors [

22], open-source cell culture incubators [

23] or open-source microscopes [

24]. This model has been shown to produce high-quality medical and scientific hardware for a small fraction of the cost of proprietary products [

25,

26].

Treatment for SNJ is most commonly administered through phototherapy [

27] by exposing the infant to a light source of sufficient intensity (irradiance ≥ 30 µW/cm

2/nm) [

28] and appropriate wavelength (420nm – 500nm) [

29] to break down excess bilirubin in the blood [

30]. Other methods such as exchange transfusion carry additional risks such as infection, blood clots and neonate mortality while producing less effective patient outcomes [

31]. Intravenous immunoglobulin administration pose several concerns given its low efficacy, higher cost and donor requirements [

32]. Phototherapy has been demonstrated to be the preferred method of treatment [

33]. This paper uses the open hardware model to develops a low-cost phototherapy device capable of being manufactured in low resource settings. In conjunction with the open source validated irradiance meter [

34] the pair acts as a complete system to effectively treat severe neonatal jaundice at minimal cost.

To validate the performance of the device, its output wavelength, intensity and coverage will be measured and compared to the standard set by the American Academy of Paediatrics and UNICEF phototherapy technical specifications [

35]. A further cost and performance analysis is made against modern commercial units sold in North America [

36]. It is then validated and tested for practicality through deployment and testing at Kenyetta University, Kenya. The results are presented and discussed in the context of providing low-cost light therapy treatment everywhere in the world.

2. Materials and Methods

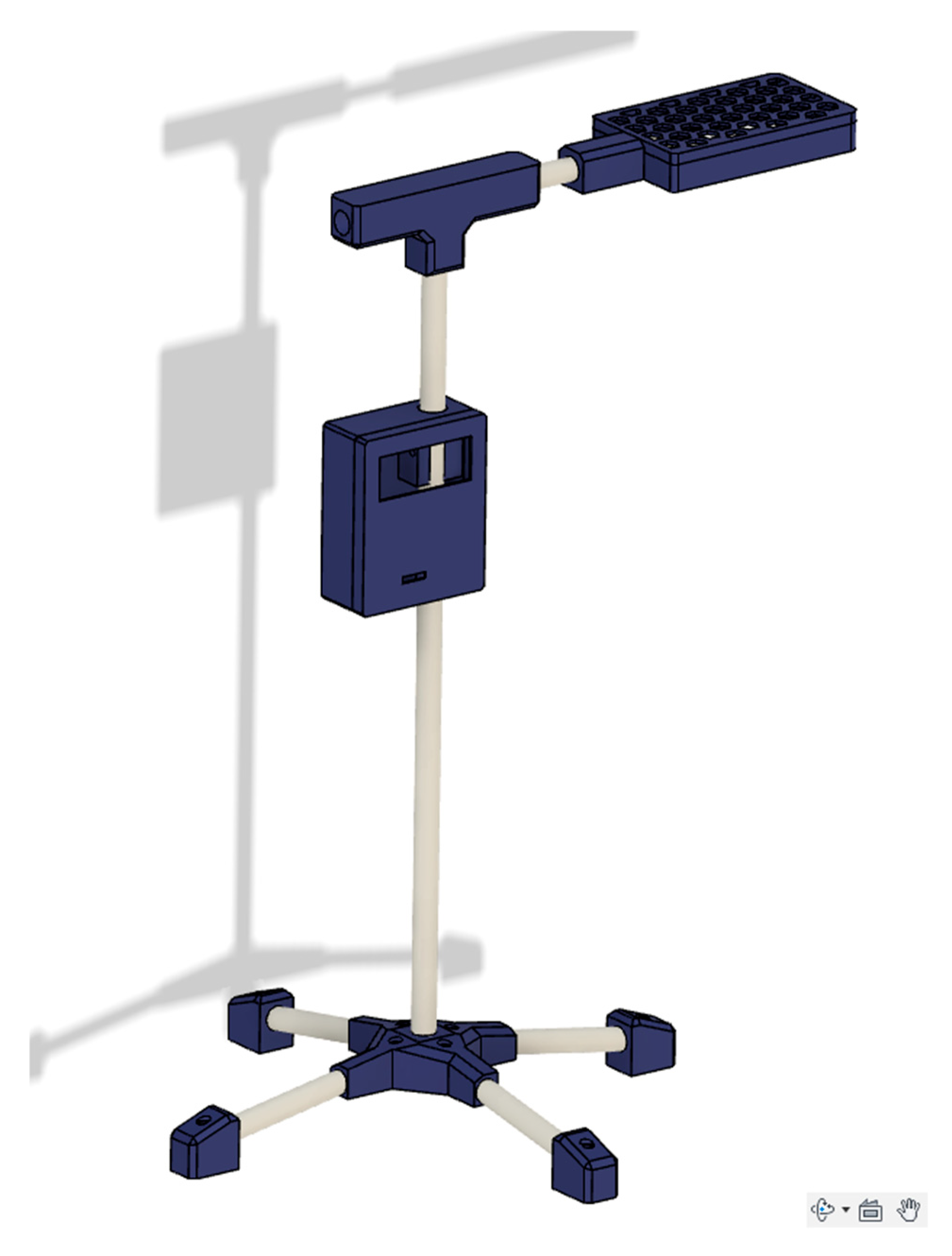

The open-source neonatal light therapy device (NLTD) is shown in

Figure 1 and constructed in three sub-assemblies:

- a)

The structural body including the 3D printed electronic housings, PVC pipes and joints connecting the pipes.

- b)

The microprocessor, power delivery and interface electronics.

- c)

The light source and heat dissipation assembly.

A detailed assembly of the open source NLTD is presented in

Appendix A. To determine the viability of the device, a NLTD was constructed following the directions in

Appendix B and

Appendix C. The calibrated Ocean Insight UV-VIS FLAME spectrometer [

37] was used to determine both the irradiance intensity and peak wavelength within the range of 200 – 800 nm. Multiple readings over a 2 hour time span were taken to verify consistent spectral output. A mapping of the irradiated surface was created by holding the source at distances of 33 cm and 45 cm and measuring irradiance at equally spaced intervals. The mapping of the surface was then plotted for further analysis.

The intensity, wavelength and surface irradiated were then compared to the standard set by the American Academy of Paediatrics for effective phototherapy treatment for SNJ [

27] and commercial products currently in use. The UNICEF phototherapy technical specifications [

35] was used to determine if the device offered all the required functionalities for hospital operation. Finally, a bill of materials (BOM) was developed (

Appendix A) to determine the cost compared to commercial units available in North America. A comparison of cost and performance is then presented in the discussion section.

In addition, an experimental evaluation in a clinical environment on the accuracy and reliability of the irradiance meters, the 3-D-printed light meter [

34] and a commercial reference meter (MTTS) was conducted. The open-source neonatal light therapy device designed for the management of neonatal jaundice. The irradiance of the two light meters with respect to the output of the phototherapy unit was measured (µW/cm²/nm) at varying distances from the top of the light source using both the locally fabricated 3D printed light meter and the commercially available or reference meter. All the measurements were recorded at distance between 10 cm to 60 cm at different intervals i.e., 5cm interval from 10 cm to 30 cm and 10 cm interval from 30cm to 60cm. The primary aim of this experiment was to compare the performance of the prototype (both open-source neonatal light therapy device and the locally fabricated 3-D printed light meter) against the established and commercially available references.

3. Results

3.1. Spectral Analysis

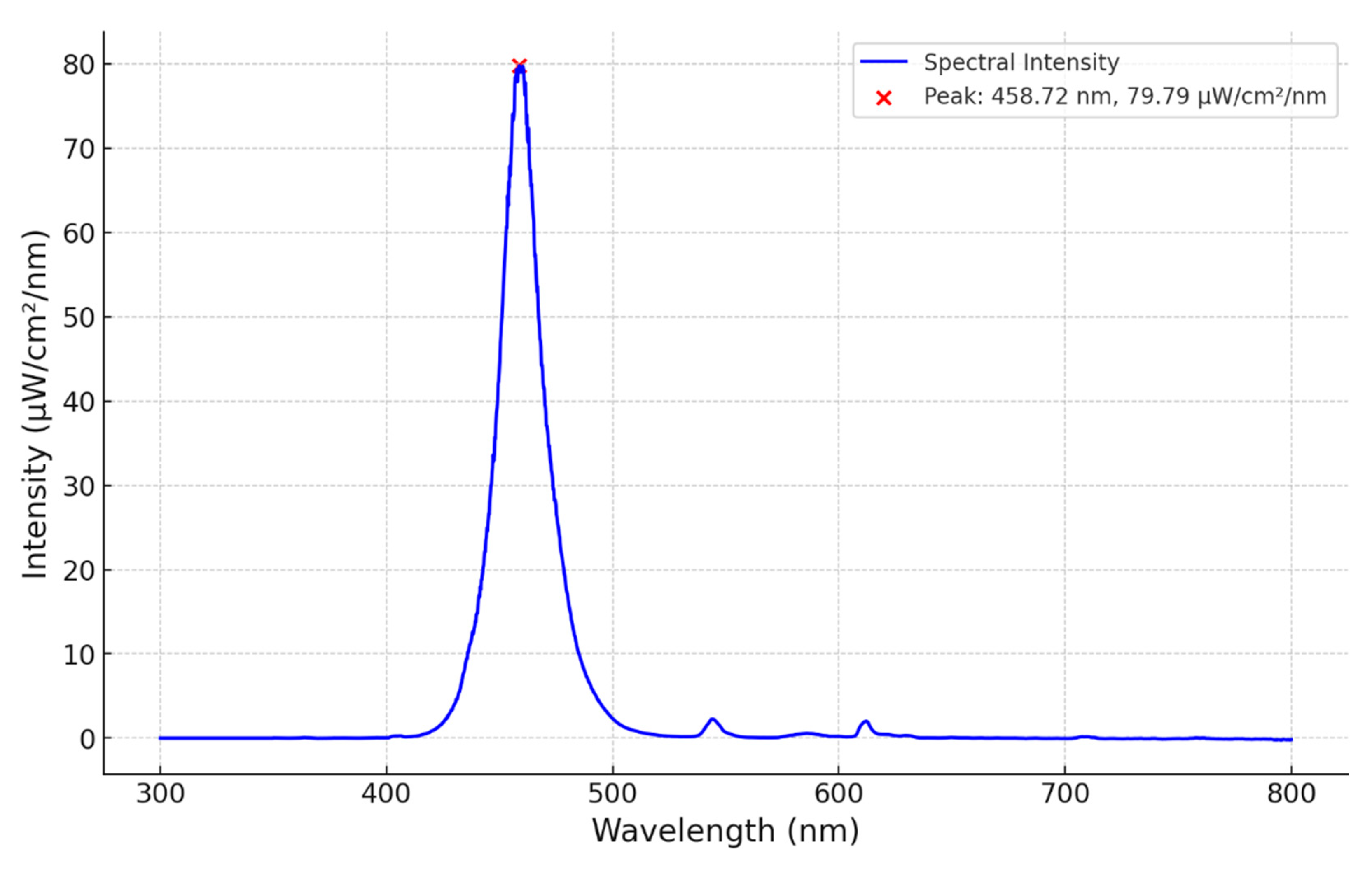

A calibrated spectrometer was placed directly under the neonatal lamp 33 cm from the source. A distinct peak of 80 µW/cm

2/nm at 459 nm is shown in

Figure 2. The total spectrum falls within 420 – 500 nm, with a half power bandwidth of 22 nm making the open source NLTD comparable to that of the LED units in

Table 1. The source spectrum shows no variation in irradiance over a 2-hour period.

3.2. Irradiance Footprint

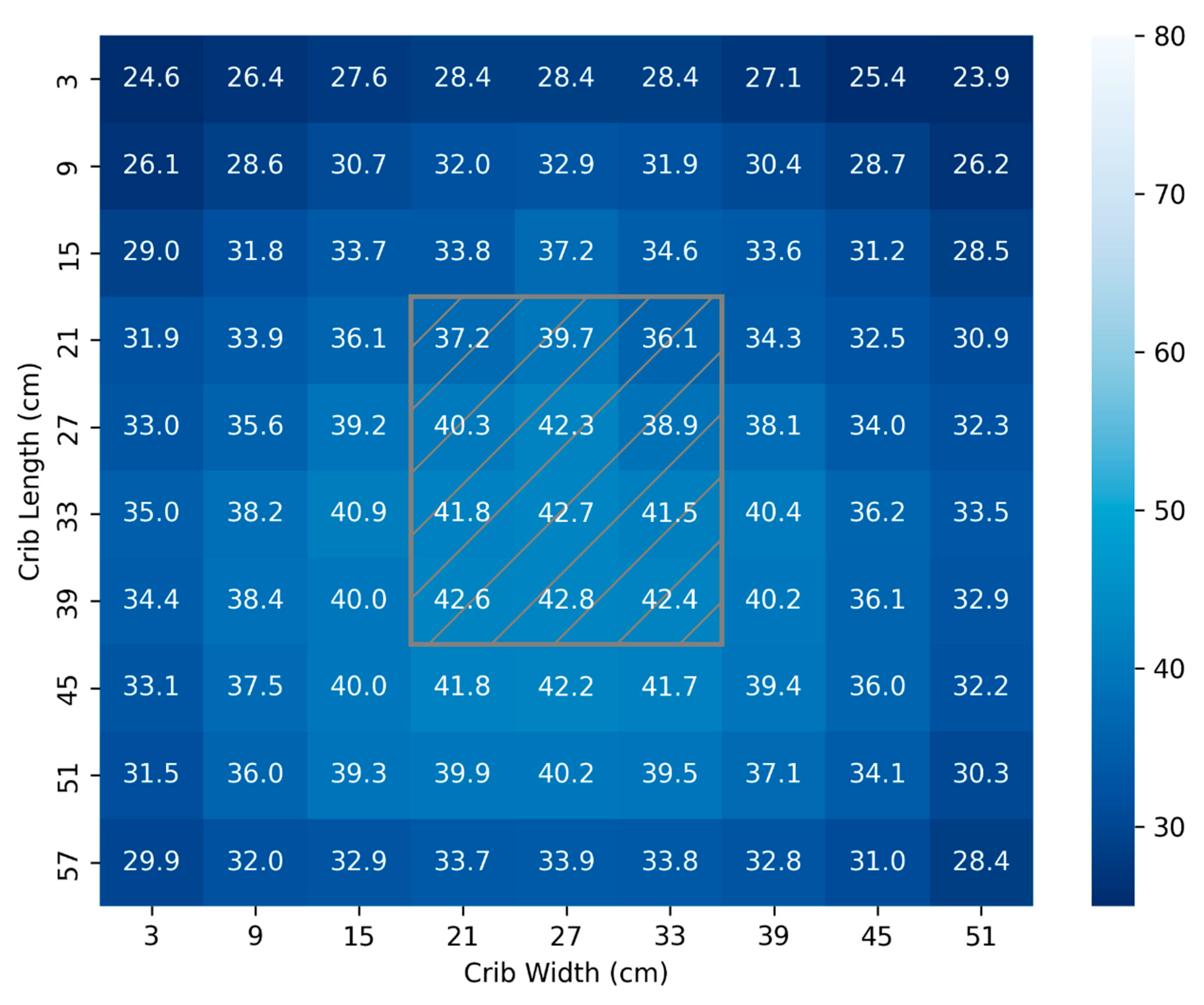

For the 45 cm test, the location of the lamp head is overlayed by the hatched grey box as shown in

Figure 3. It is observed that from 45cm, the distribution of light is relatively uniform and 81% of the surface is exposed to the minimum recommended dose for SNJ of 30 µW/cm

2/nm [

28,

29,

30,

38,

39,

40]. The total surface area mapped is 3240 cm

2. The distribution of light in

Figure 3 produces a mean and standard deviation (34.5 ± 4.3) µW/cm

2/nm.

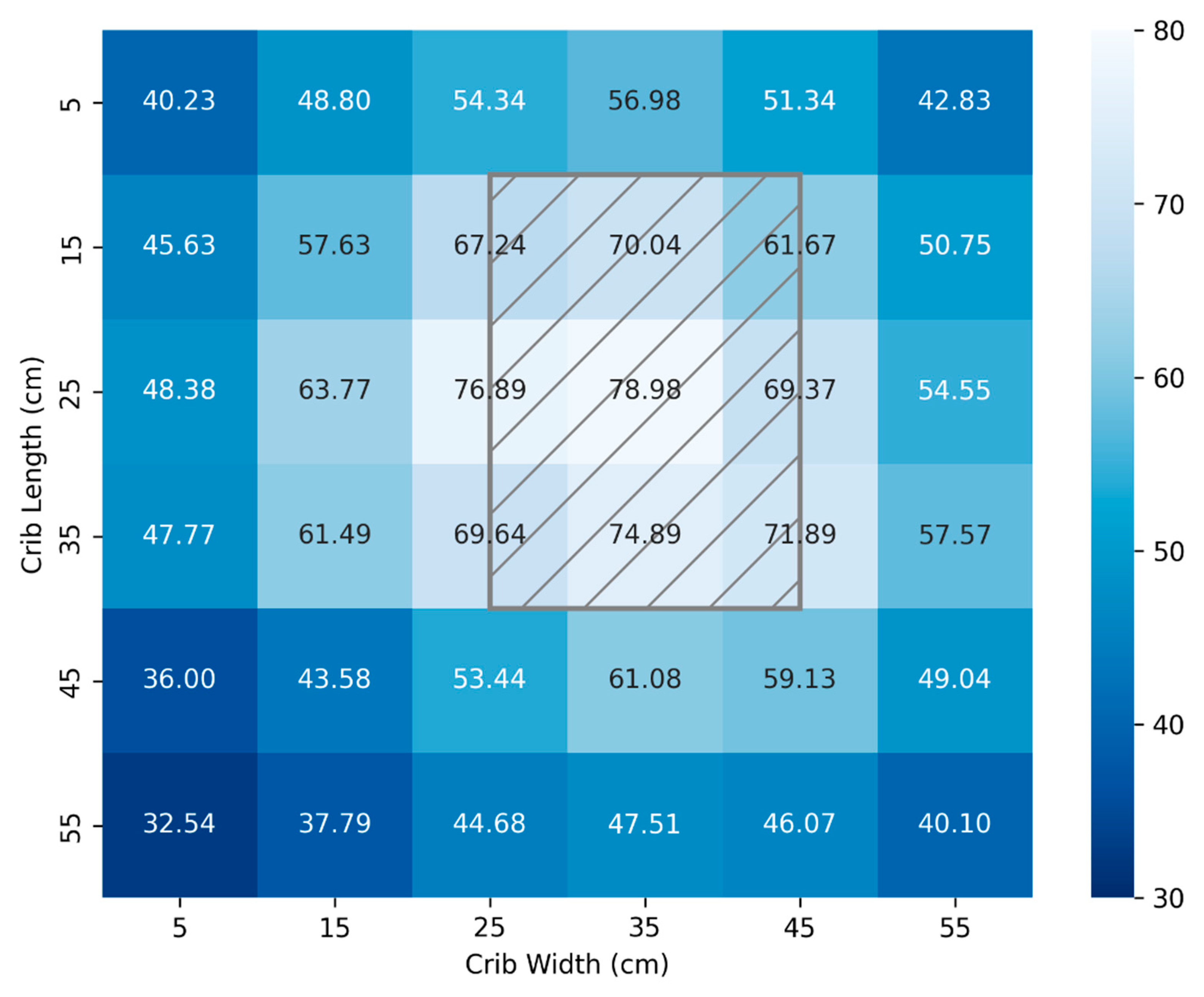

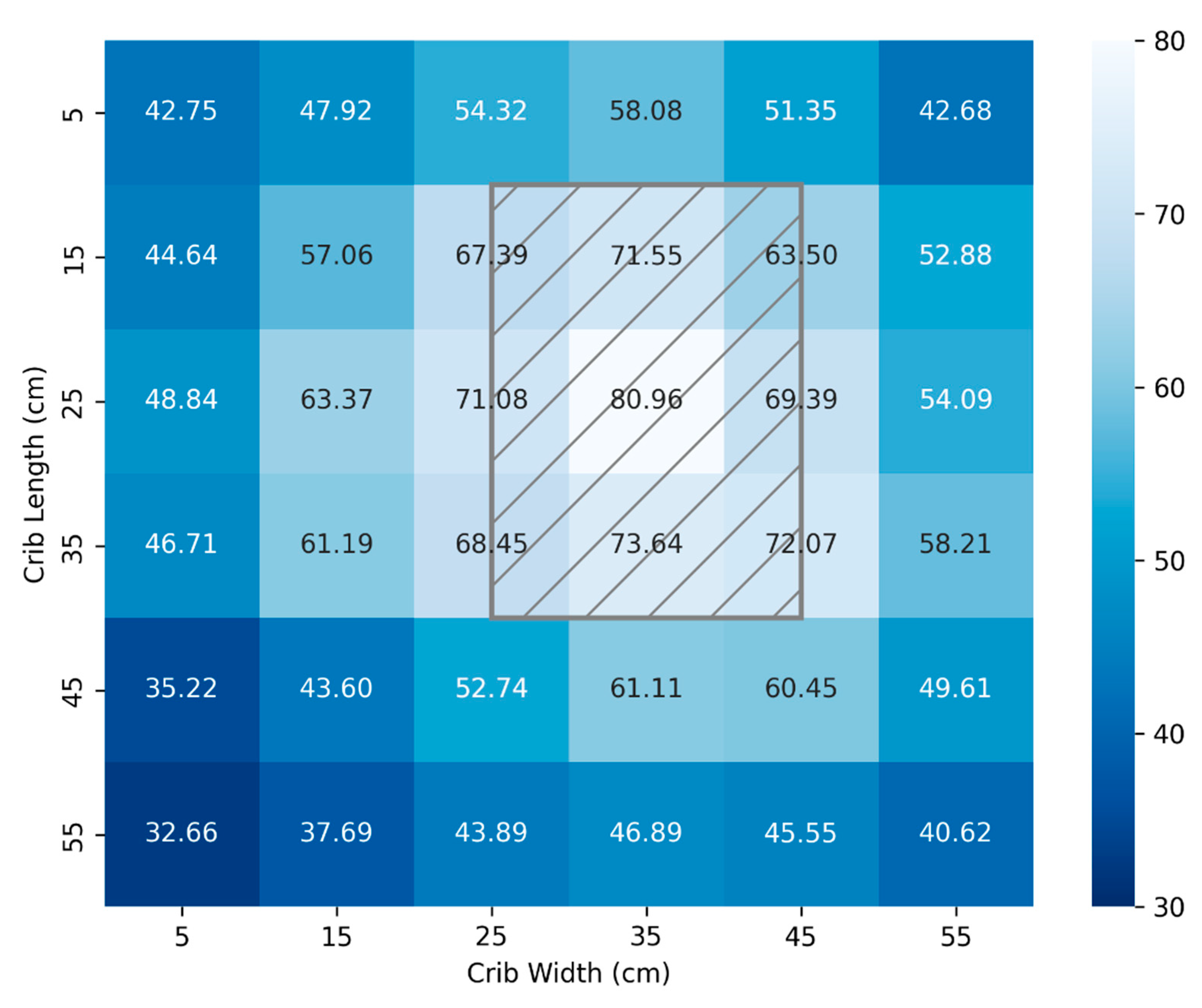

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate mappings using a calibrated spectrometer and the FAST Irradiance meter, respectively. Measurements were taken at 10 cm intervals for a crib area of 3,600cm

2 and a distance from the source of 33 cm. By bringing the lamp closer, a more potent dosage can be administered for the most severe cases at the expense of a less uniform total area. Again, the location of the lamp head above the crib is represented by the hatched grey rectangle.

The light distribution of

Figure 4 produces a mean and standard deviation of (54.8 ± 12.0) µW/cm

2/nm while

Figure 5 produces a mean and standard deviation of (55.1 ± 11.8) µW/cm

2/nm. The absolute average difference in measured values between the calibrated spectrometer and the FAST developed irradiance meter is 0.88 µW/cm

2/nm.

Table 2 summarizes parameters of commercial therapy units originally sourced from the American Academy of Pediatrics technical report on Phototherapy to prevent Severe Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia [

27]. The results from the open-source NLTD is also included in the table and aims to meet or exceed these metrics.

Table 1 in the introduction shows the cost of typical NLTD in use in North America. The products selected for market analysis were chosen based on similarity to that of the FAST NPTD; namely that they are all overhead LED devices. As shown in

Appendix A, the cost of building a FAST NLTD in Canada totals

$130.03 CAD or

$92.93 USD. This is only ten percent of the cost of even the least expensive proprietary commercial option on the market.

The results obtained from the open-source neonatal light therapy device showed close correlation on irradiance values taken by the two light meters as shown in

Table 3. It should be pointed out, however, there was minimal variance recorded across the distances confirming the accuracy and reliability of the locally assembled devices, (both the open-source neonatal light therapy device and the locally fabricated 3D printed light meter) with reference to the established reference devices.

4. Discussion

Phototherapy is the primary treatment for SNJ [

40], utilizing light with an irradiance of at least 30 µW/cm²/nm and a wavelength range of 420–500 nm [

38] to facilitate the breakdown of excess bilirubin in the blood [

39].

High Income countries experience far lower rates of SNJ compared to Lower and Middle income countries (LMIC) mainly due to limited access to necessary equipment [

5]. As a result, populations within LMIC are disproportionately affected by Kernicterus Spectrum Disorder (KSD) [

41], a preventable chronic disease characterized by abnormal motor function, oculomotor impairment and auditory complications [

42]. KSD results from the buildup of bilirubin in the neonate’s blood stream and requires immediate phototherapy treatment to lower the level of bilirubin [

43]. KSD severely limits the abilities and opportunities of those afflicted for the remainder of their lives [

41]. This paper has shown that appropriate and cost-effective phototherapy equipment can be implemented through open-source hardware to effectively treat SNJ in LMIC.

It is first demonstrated through spectroscopic analysis that the FAST NLTD produces a spectrum of peak wavelength 460nm and half power bandwidth of 22nm. This falls within the spectrum which effectively decompose bilirubin within the bloodstream as cited by Porter [

44] and Maisels [

45]. At 45 cm from the source, the distribution of light was calculated to irradiate at a mean and standard distribution of (34.5 ± 4.3) µW/cm

2/nm. This result compares well with commercial products presented in

Table 2 [

27].

The total surface area available for therapy mapped in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 is 3600 cm

2 which significantly exceeds the UNICEF required technical specifications [

35] of minimum effective surface area ≥ 1,220 cm². It also exceeds the footprint area of commercial NLTD referred to in

Table 2 [

27].

If the UNICEF technical specification of minimum effective surface area is used as the benchmark for the crib area required to treat a single infant, then a single open source NLTD can treat 3 neonates simultaneously. The significance of this result cannot be overstated given that many neonatal wards in developing countries may overpopulate the crib due to limited facilities [

46]. The larger effective area provided by the open source NLTD will reduce the risk of overcrowding cribs to meet treatment demand.

The material cost to construct an open source NLTD totals

$93.00 USD (

$130.00 CAD) which represents a 92.3% to 98.7% cost reduction compared to commercial NLTD. In LMIC communities, access to effective treatment of SNJ has been hindered by high costs and technologies that are ill-suited to resource-limited settings [

47]. The open source NLTD significantly lowers the financial barrier to accessing this essential equipment.

A further barrier to effective treatment is the inability to effectively monitor and dose phototherapy treatment [

6]. Is has also been demonstrated in this paper that the FAST irradiance meter [

34] is equally effective at measuring phototherapy dosage as a calibrated spectrometer with an absolute average deviation between the instruments of less than 1 µW/cm

2/nm. The open-source NLTD in conjunction with the FAST irradiance meter establishes a complete open-source system to treat severe neonatal jaundice at a price point significantly lower than that to purchase a commercial set of equipment.

Avenues towards further developments should be investigated. Namely: incorporation of reflective material to increase irradiance homogeneity [

48], an investigation into the thermal characteristics and long term use of the device or hardware improvements to increase power delivery and number of heads per unit. This device meets most of the UNICEF required technical specifications [

35] with the exception of the following: battery operation for power outages less than 10 minutes and white LEDs for examination. These are considered lower priority features which will add cost and do not improve patient outcomes. They are thus reserved for future revisions.

These findings validate the effectiveness of the open-source neonatal light therapy device in delivering accurate, consistent, and reliable irradiance for neonatal jaundice management. This work has also highlights fundamental benefits of the 3D-printed light meter such as low-cost, as well as reliability in comparison to the commercially available irradiance meters. These innovations are not only valuable to resource limited settings but also a game changer in the fight and reduction of neonatal deaths arising from jaundice and therefore a key step towards saving lives especially in low-middle income countries where access to such technologies, phototherapy is limited. Therefore, ensuring affordable, and consistent monitoring, these low cost technologies can play a significant role in improving the quality of care for newborns born or suffering from jaundice.

5. Conclusions

One of the leading causes of severe neonatal jaundice in low- and middle-income countries is lack of cost effective and appropriate technology to prevent the disease. It has been demonstrated that an open-source neonatal light therapy device to treat SNJ can be built at a significantly lower cost while producing treatment metrics equivalent to or exceeding commercial devices available in developed nations. The device, whose material costs are $93.00 USD ($130.00 CAD), was shown to produce irradiance of 80 µW/cm2/nm within the acceptable range of 420 – 500 nm. It was further demonstrated that the unit could produce a uniform distribution of (34.5 ± 4.3) µW/cm2/nm over a surface area exceeding 3,200cm2. By releasing documentation, building instructions and designs in an open-source manner the device may be broadly distributed. In conjunction with the open source irradiance meter, the pair constitute a fully operational unit to treat SNJ in resource limited communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.P..; methodology, J.G., A.W., J.M., and J.M.P validation, J.G., A.W., J.N., G.N., G.M.; formal analysis, J.G., A.W., J.N., G.N., G.M., J.M., and J.M.P.; investigation, J.G., A.W., J.N., G.N., G.M.,; resources, J.M., and J.M.P.; data curation, J.G., A.W.,; writing—original draft preparation, J.G. and J.M.P.; writing—review and editing, J.G., A.W., J.N., G.N., G.M., J.M., and J.M.P.; visualization, J.G.; supervision, J.M., and J.M.P. project administration, J.M., and J.M.P.; funding acquisition, J.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Frugal Biomed Grant and the Thompson Endowment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Neonatal Light Therapy Device Bill of Materials

| Component |

Description |

Quantity |

Cost (CAD) |

| LED |

|

24 |

$6.00 |

| 2"Caster wheels |

|

4 |

$3.08 |

| 1/2" PVC pipe |

|

8 ft |

$14.37 |

| Arduino Nano |

|

1 |

$1.89 |

| LCD |

|

1 |

$1.09 |

| Buck Converter |

|

1 |

$0.37 |

| 12V 24W wall adapter |

|

|

$12.74 |

| PCB |

|

2 |

$24.20 |

| Button |

|

1 |

$1.41 |

| |

|

SUB TOTAL |

$65.15 |

| Shipping, Misc. standard electronics* |

100% of Total |

|

$65.15 |

| |

|

TOTAL |

$130.30 |

Appendix B. Build Documentation

Structural Sub-Assembly

Figure 6.

Structural Sub-Assembly.

Figure 6.

Structural Sub-Assembly.

Figure 6 illustrates the Structural Sub-Assembly consisting of six 12mm (1/2”) polyvinyl-chloride (PVC) pipes with an outer diameter of 21.4mm (0.84”). The approximate lengths of each are shown in

Table 3. It is found that PVC pipe used for pipe C can be made to 80 cm before bending becomes a significant factor. It is recommended that for a unit with a desired height exceeding 130 cm, pipe C should be replaced by a wooden dowel of equivalent diameter.

Table 3.

Pipe Fittings.

| ID |

Description |

Length (cm) |

| A |

Tee to Light Source Housing |

~45 |

| B |

Electronics Housing to Tee |

~45 |

| C |

Base to Electronics Housing |

~70 - 130 |

| D-G |

Four Legs |

~45 |

All remaining components are 3D printed parts. They include the light source housing, the electronics housing, the T- connector, base connector and caster wheel adapters. The model files are found at

https://osf.io/93gnj/ .

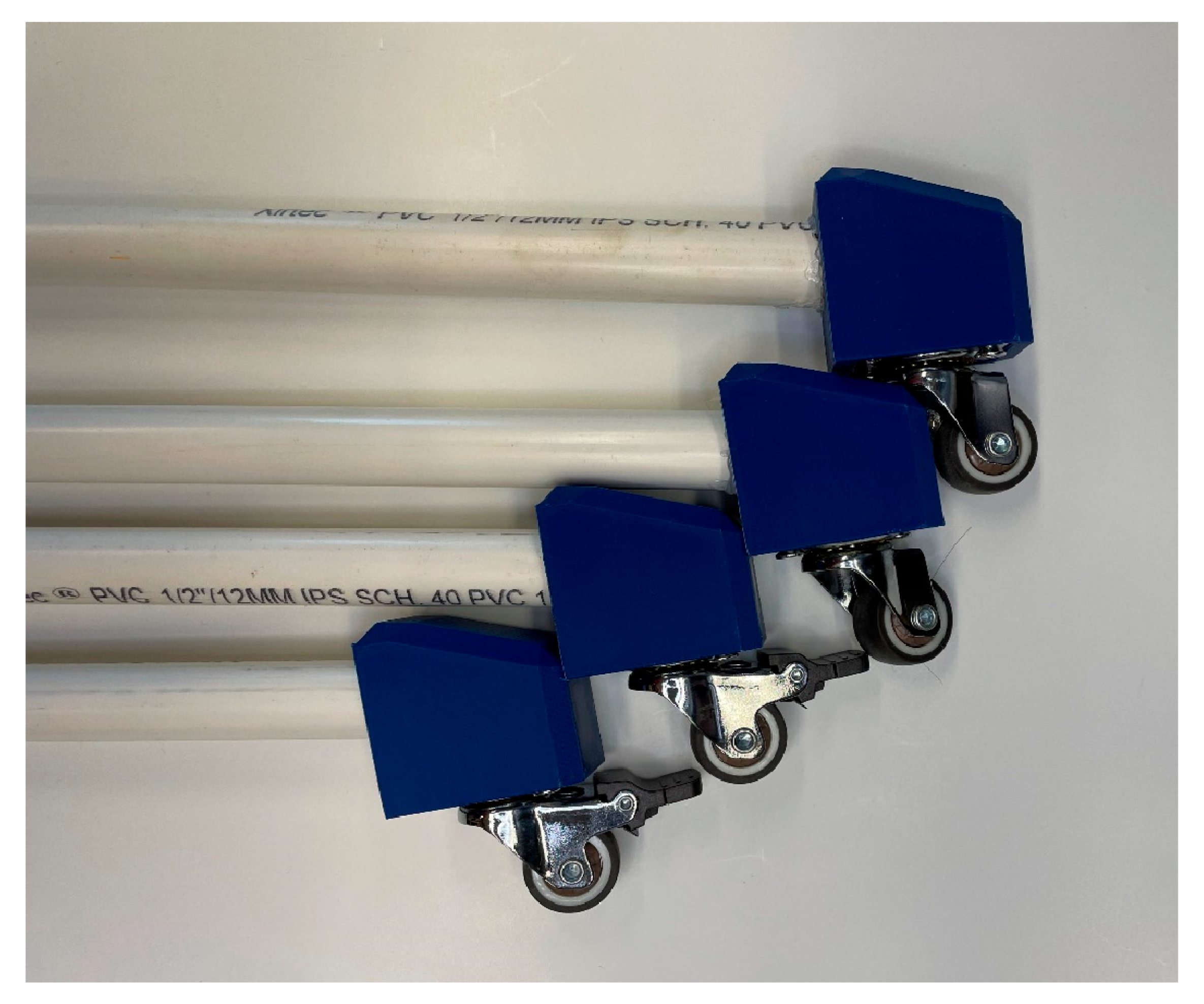

Once the relevant components are printed, each of the caster wheel adapters are secured to the pipes D-G with a nut and bolt (or optionally ABS cement)

Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Caster wheels fitted to feet.

Figure 7.

Caster wheels fitted to feet.

Each foot can then be connected through the base connector as shown in

Figure 8. If only 2 of your casters have breaks it is recommended that they are positioned adjacent to one another to maximize breaking ability. A nut and bolt securing the base through each pipe is recommended. Secure pipe C to the center of the base connector with ABS cement.

Figure 8.

Pipes D-G secured to Base Connector.

Figure 8.

Pipes D-G secured to Base Connector.

A height adjustment mechanism is implemented as shown in

Figure 9 so that irradiance dosing is more easily varied.

Figure 9.

- Height Adjustment Mechanism.

Figure 9.

- Height Adjustment Mechanism.

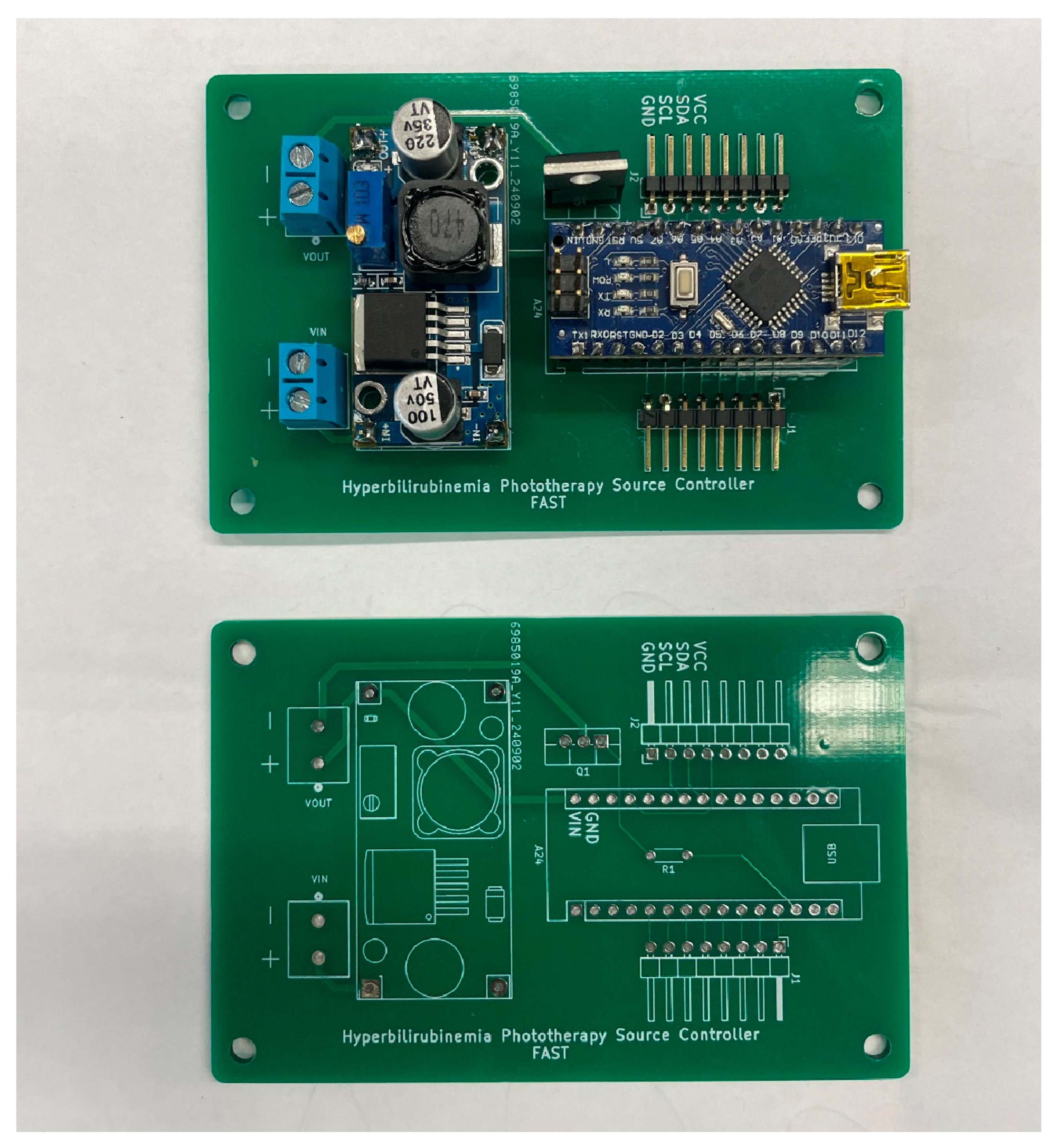

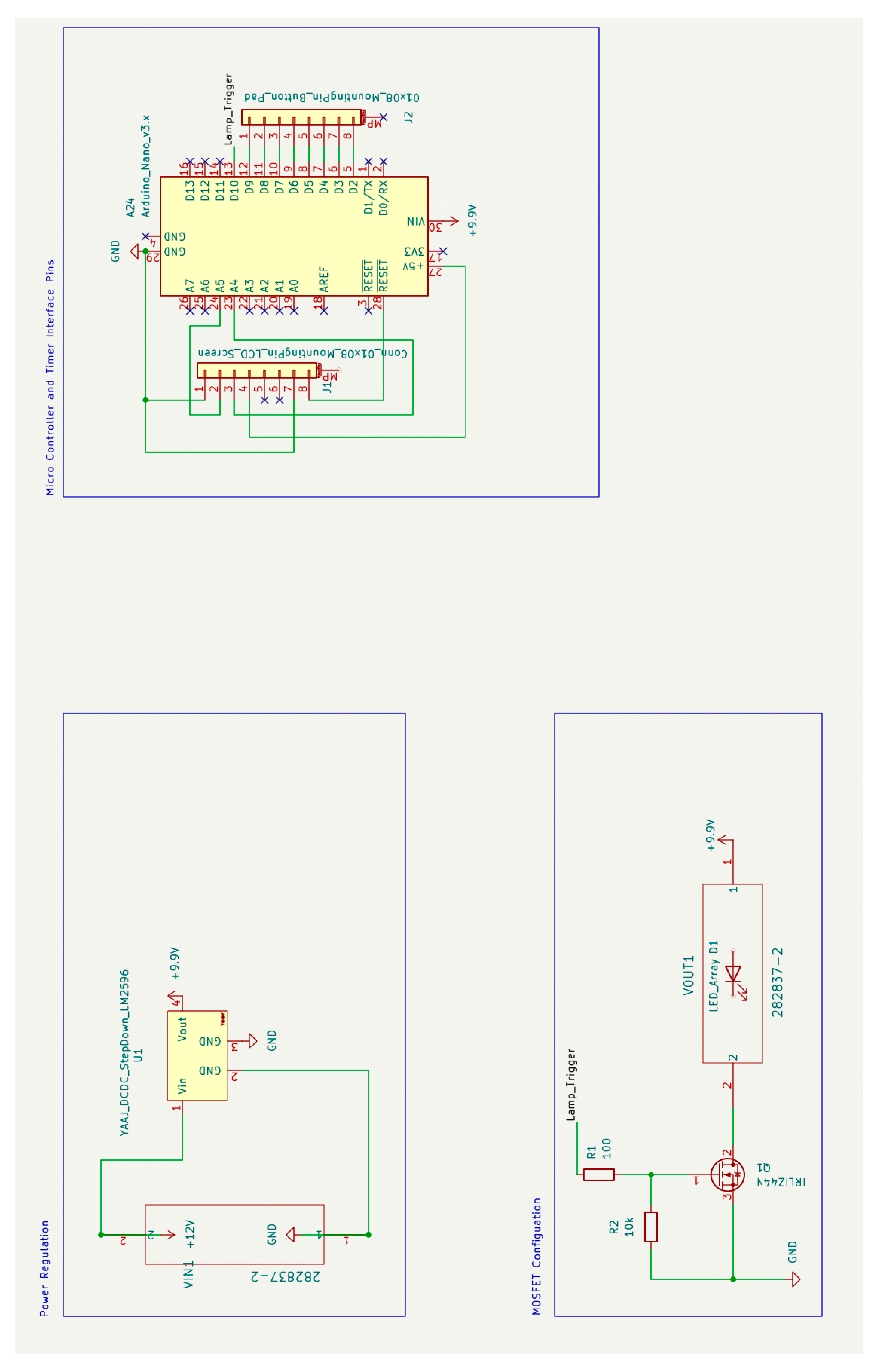

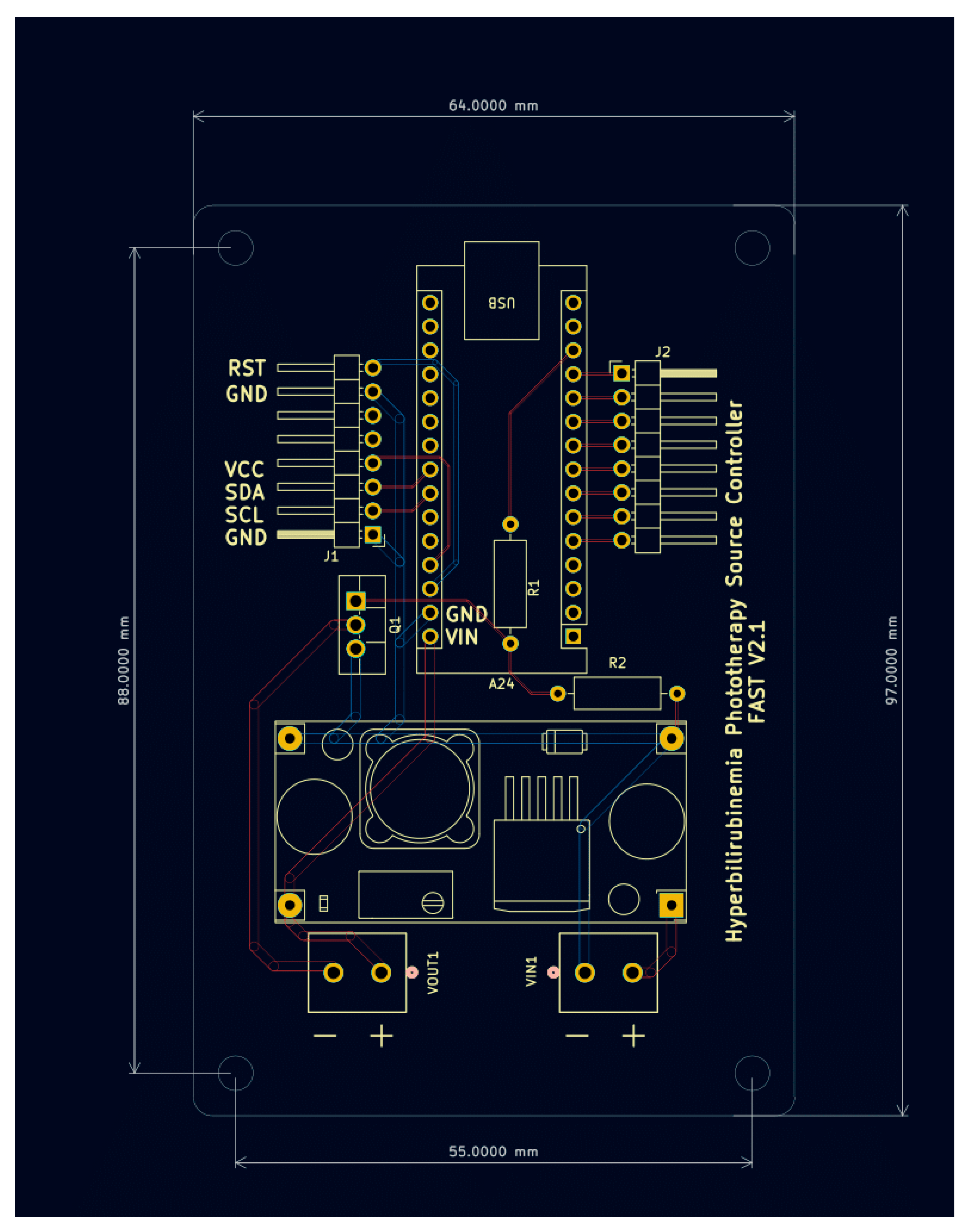

Electronics Sub-Assembly

This sub-assembly consists of power conversion and regulation circuitry, user interface hardware and the system controller. Power is converted from 110V 60Hz AC input from a wall outlet to 12 V DC with a maximum current output of 10A using a standard AC power supply. The 12 V DC line is stepped down through a voltage regulator to a stable 9.9 V using the LM-2596 DC-DC Converter. The output is then routed to provide continuous power to the Arduino nano microcontroller. The output is also connected to the drain side of an N-Channel MOSFET whose gate input is triggered by a pin from the Arduino nano. When the gate is pulled high, current is allowed to flow through the MOSFET and provide power to the lamp source which is further described in the Lamp Source Sub-Assembly. See

Figure 9 for the PCB assembly of the power converter, microcontroller and MOSFET.

Figure 10.

PCB Pre and Post Assembly.

Figure 10.

PCB Pre and Post Assembly.

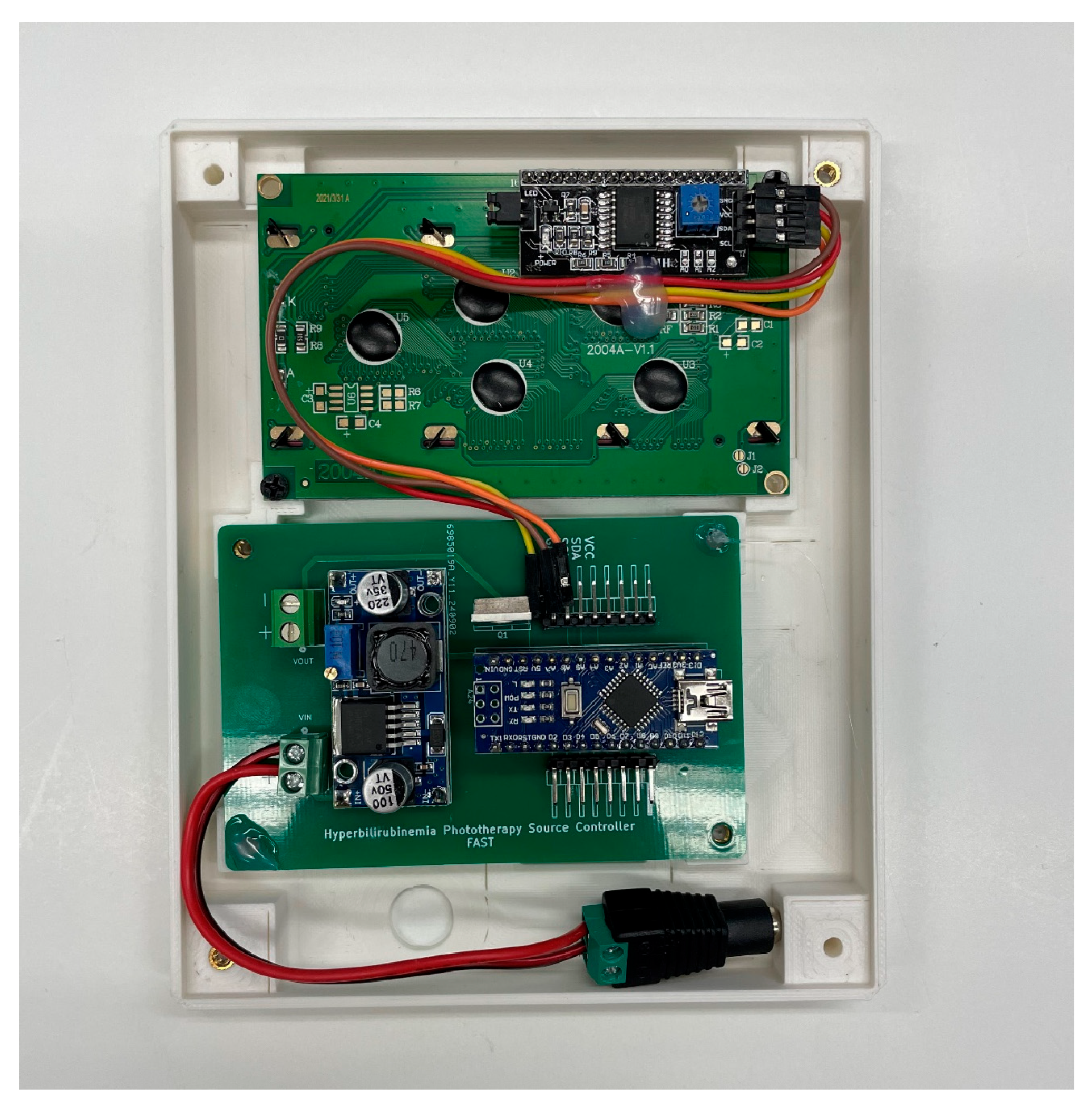

The Arduino is also responsible for monitoring the duration for which the lamp is on. This is accomplished using a timer interface. A number pad is presented to the administrator who can then select the hours and minutes for the lamp to be on. An LCD screen is included to assist with this process and display the remaining time before shutting off.

Figure 10 shows the LCD screen connected to the controller PCB. A detailed description of how to use the interface is provided in

Appendix C.

Figure 11.

- Screen and Controller PCB installed in face of electronics box.

Figure 11.

- Screen and Controller PCB installed in face of electronics box.

The schematic diagram along with the printed circuit board drawing are presented in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 respectively. The files required to order these boards can be found

https://osf.io/93gnj/ .

Figure 12.

Schematic Diagram.

Figure 12.

Schematic Diagram.

Lamp Source Sub-Assembly

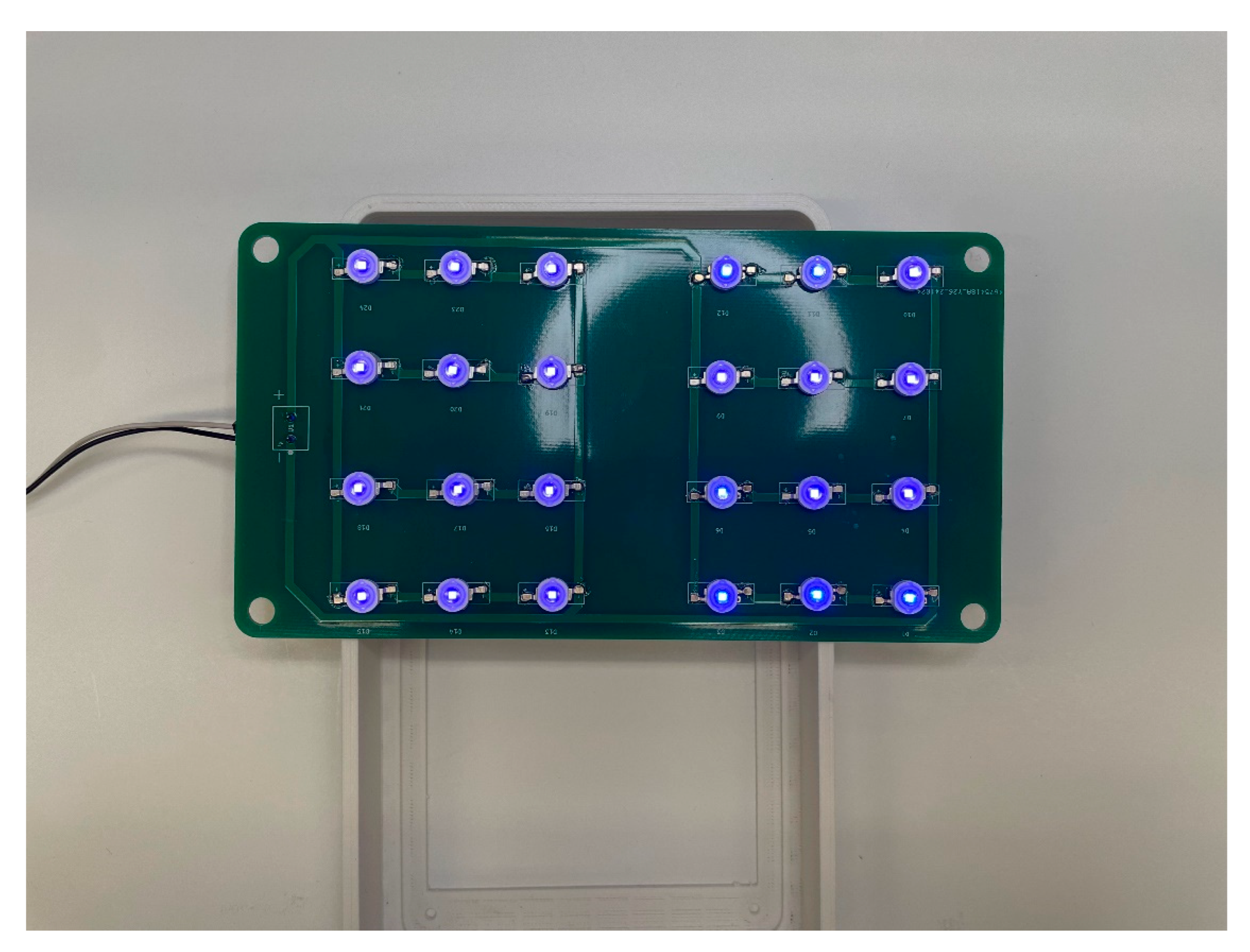

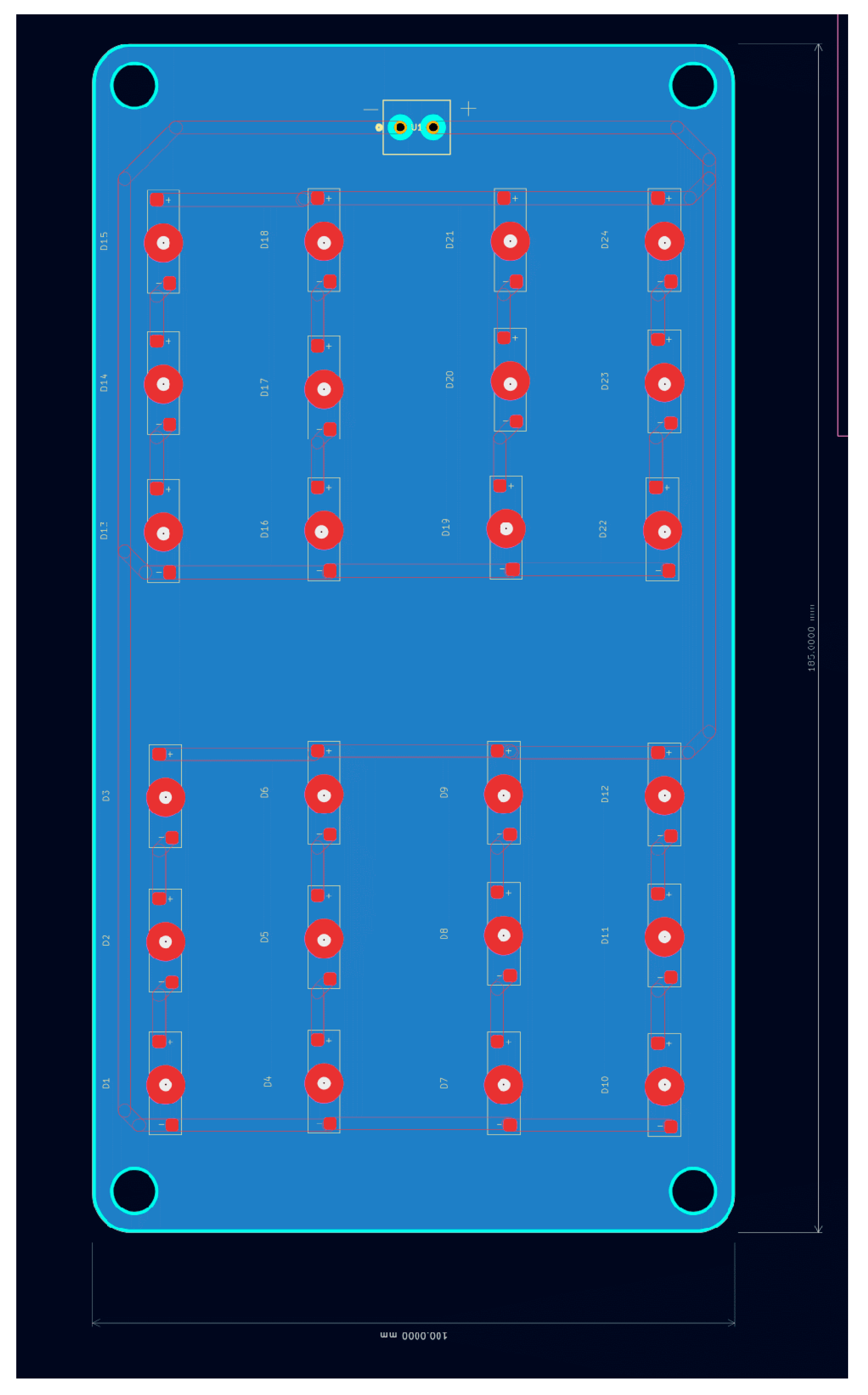

This sub-assembly consists of the light source providing the treatment to the infant and wires providing power. The source consists of an array of 24 LED’s each operating at 3V and maximum constant current of 350mA. The source can draw a total of 12.6 watts and requires a heat sink to prevent overheating during long periods of operations.

The lamp source before and after assembly can be seen in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 respectively. The PCB drawing of the LED Array Circuit is shown in

Figure 16. Before assembly, a small amount of thermal paste is applied to each round pad while solder paste is applied to each adjacent electrical pad. Each LED is then placed on the PCB, oriented by the correct polarity, before a hot air solder station applies heat to secure the LED to the PCB.

Figure 14.

Lamp Source pre Assembly.

Figure 14.

Lamp Source pre Assembly.

Figure 15.

Source Post assembly with minimal test voltage applied.

Figure 15.

Source Post assembly with minimal test voltage applied.

Figure 16.

LED Array PCB.

Figure 16.

LED Array PCB.

Final Assembly

The electronics sub-assembly should be secured to the top of pipe C. Connect a pair of 18-gauge wire to the ‘Vout’ pin header and route the wires up through the top of the electronics sub-assembly box and into pipe B. Pipe B is then inserted into the top of the box. Route the wires through the Tee connector and into pipe A. Finally secure the ends of each wire to their respective terminal in the lamp source assembly. Secure the lamp source sub assembly to pipe A with ABS Cement.

Put the lamp in “Always On” mode using steps outlines in

Appendix C. Measure the voltage across the LED assembly and adjust the voltage output on the DC-DC converter until you read 9.1 - 9.8 volts across the light source. Verify system operates as expected before closing the front of the electronic sub-assembly housing with M3 x 20mm screws. The final Assembly is shown in

Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Device Operation after Final Assembly.

Figure 17.

Device Operation after Final Assembly.

Appendix C. User Interface Guide

When power is supplied, the screen in

Figure 16 will appear. Selecting A will immediately toggle the lamp on, and it will remain on until the blue reset button is triggered.

Figure 18.

Mode Selection Screen.

Figure 18.

Mode Selection Screen.

If B is selected, the unit will be placed into timer mode as shown in

Figure 17. The unit will wait until four digits are pressed representing the hours and minutes it will be set to. The two hour digits are entered first followed by the minute digits. The lamp will immediately turn on once the fourth digit is entered, and the elapsed time will update every second under the ‘Curr. Time’ column as shown in

Figure 18. Once the current time is equal to the set time, the unit will turn off. The blue reset button must be pressed to return to the start screen.

Figure 19.

Timer interface awaiting input.

Figure 19.

Timer interface awaiting input.

Figure 20.

Timer showing elapsed time.

Figure 20.

Timer showing elapsed time.

References

- Bhutani, V.K.; Zipursky, A.; Blencowe, H.; Khanna, R.; Sgro, M.; Ebbesen, F.; Bell, J.; Mori, R.; Slusher, T.M.; Fahmy, N.; et al. Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia and Rhesus Disease of the Newborn: Incidence and Impairment Estimates for 2010 at Regional and Global Levels. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 74, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diala, U.M.; Usman, F.; Appiah, D.; Hassan, L.; Ogundele, T.; Abdullahi, F.; Satrom, K.M.; Bakker, C.J.; Lee, B.W.; Slusher, T.M. Global Prevalence of Severe Neonatal Jaundice among Hospital Admissions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasirer, Y.; Kaplan, M.; Hammerman, C. Kernicterus on the Spectrum. NeoReviews 2023, 24, e329–e342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Kaplan, M.; Hansen, T.W.R. Neonatal Hyperbilirubinaemia: A Global Perspective. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusher, T.M.; Zamora, T.G.; Appiah, D.; Stanke, J.U.; Strand, M.A.; Lee, B.W.; Richardson, S.B.; Keating, E.M.; Siddappa, A.M.; Olusanya, B.O. Burden of Severe Neonatal Jaundice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2017, 1, e000105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrom, K.M.; Farouk, Z.L.; Slusher, T.M. Management Challenges in the Treatment of Severe Hyperbilirubinemia in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Encouraging Advancements, Remaining Gaps, and Future Opportunities. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Ogunlesi, T.A.; Slusher, T.M. Why Is Kernicterus Still a Major Cause of Death and Disability in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries? Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- neoBLUE® LED Phototherapy System. Available online: https://natus.com/sensory/neoblue-led-phototherapy-system/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- neoBLUE® Compact LED Phototherapy System for Newborn Jaundice. Available online: https://natus.com/sensory/neoblue-compact/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Pocket Nurse® Infant Phototherapy Unit for Simulation. Available online: https://emrn.ca/pocket-nurse-infant-phototherapy-unit-for-simulation/ (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Bistos BT-400 Neonatal Blue LED Phototherapy Equipment. Available online: https://medlabamerica.com/products/bistos-bt-400-neonatal-blue-led-phototherapy-equipment (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Bistos BT-550 Infant Warmer w/LCD Display. Available online: https://medlabamerica.com/products/bistos-bt-550-infant-warmer (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Coker, A.; Achi, C.; Idowu, O.; Olayinka, O.; Oturu, K. Remanufacture of Medical Equipment: A Viable Sustainable Strategy for Medical Waste Reduction.

- Ademe, B.W.; Tebeje, B.; Molla, A. Availability and Utilization of Medical Devices in Jimma Zone Hospitals, Southwest Ethiopia: A Case Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, C.; Di Pietro, L.; Ravizza, A.; Lantada, A.D.; Ahluwalia, A.D. Chapter 2 - Open-Source Medical Devices: Healthcare Solutions for Low-, Middle-, and High-Resource Settings. In Clinical Engineering Handbook (Second Edition); Iadanza, E., Ed.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 7–14 ISBN 978-0-12-813467-2.

- Otero, J.; Pearce, J.M.; Gozal, D.; Farré, R. Open-Source Design of Medical Devices. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2024, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Distributed Manufacturing of Open Source Medical Hardware for Pandemics. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2020, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A. Building Open Source Hardware: DIY Manufacturing for Hackers and Makers; Addison-Wesley Professional, 2014; ISBN 978-0-13-337390-5.

- Oberloier, S.; Pearce, J.M. General Design Procedure for Free and Open-Source Hardware for Scientific Equipment. Designs 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Haufe, P.; Sells, E.; Iravani, P.; Olliver, V.; Palmer, C.; Bowyer, A. RepRap – the Replicating Rapid Prototyper. Robotica 2011, 29, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sells, E.; Bailard, S.; Smith, Z.; Bowyer, A.; Olliver, V. RepRap: The Replicating Rapid Prototyper: Maximizing Customizability by Breeding the Means of Production. In Handbook of Research in Mass Customization and Personalization; World Scientific Publishing Company, 2009; pp. 568–580 ISBN 978-981-4280-25-9.

- Selvaraj, A.; Kulkarni, A.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source 3-D Printable Autoinjector: Design, Testing, and Regulatory Limitations. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0288696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newharvest-Incubator-Perfusion/README.Md at Main · IRNAS/Newharvest-Incubator-Perfusion. Available online: https://github.com/IRNAS/newharvest-incubator-perfusion/blob/main/README.md (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Collins, J.T.; Knapper, J.; Stirling, J.; Mduda, J.; Mkindi, C.; Mayagaya, V.; Mwakajinga, G.A.; Nyakyi, P.T.; Sanga, V.L.; Carbery, D.; et al. Robotic Microscopy for Everyone: The OpenFlexure Microscope 2019, 861856.

- Pearce, J.M. Cut Costs with Open-Source Hardware. Nature 2014, 505, 618–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Economic Savings for Scientific Free and Open Source Technology: A Review. HardwareX 2020, 8, e00139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, V.K. the Committee on Fetus and Newborn Phototherapy to Prevent Severe Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant 35 or More Weeks of Gestation. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e1046–e1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, S.; Okada, H.; Kuboi, T.; Kusaka, T. Phototherapy for Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatr. Int. 2017, 59, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansong-Assoku, B.; Shah, S.D.; Adnan, M.; Ankola, P.A. Neonatal Jaundice. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Chawla, D.; Deorari, A. Light-Emitting Diode Phototherapy for Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinaemia in Neonates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Fujioka, K. Can Exchange Transfusion Be Replaced by Double-LED Phototherapy? Open Med. 2021, 16, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.R.; Lu, H.; McClary, J.; Marasch, J.; Nock, M.L.; Ryan, R.M. Evaluation of Intravenous Immunoglobulin Administration for Hyperbilirubinemia in Newborn Infants with Hemolytic Disease. Children 2023, 10, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Phototherapy and Exchange Transfusion in the Management of Nonhemolytic Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia. J. Pediatr. 1975, 87, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givans, J.T.M.; Waswa, A.; Madete, J.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Light Calibration System for Hyperbilirubinemia Phototherapy Treatments 2025, 2025. 08.01.2533 2669.

- Photo Therapy Unit,w/Access. Available online: https://supply.unicef.org/s0002032.html (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Wentworth, S.D. Neonatal Phototherapy–Today’s Lights, Lamps and Devices. Infant 2005, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- SR2. Available online: https://www.oceanoptics.com/spectrometer/sr2/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Wang, J.; Guo, G.; Li, A.; Cai, W.-Q.; Wang, X. Challenges of Phototherapy for Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, T.R.C. Molecular Basis of Hyperbilirubinemia and Phototherapy. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981, 77, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisson, T.R.C. Visible Light Therapy of Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia. In Photochemical and Photobiological Reviews: Volume 1; Smith, K.C., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1976; pp. 241–268. ISBN 978-1-4684-2574-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T.W.R. Kernicterus: An International Perspective. Semin. Neonatol. 2002, 7, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; van Landeghem, F.K.H. Clinicopathological Spectrum of Bilirubin Encephalopathy/Kernicterus. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchowski, K.E. Evaluation and Treatment of Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 89, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.L.; Dennis, B.L. Hyperbilirubinemia in the Term Newborn. Am. Fam. Physician 2002, 65, 599–607. [Google Scholar]

- Maisels, M.J.; McDonagh, A.F. Phototherapy for Neonatal Jaundice. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam C, G.; Ethan M, T.; Hendrik J, V.; Tina M, S. Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia in Low-Income African Countries. Int. J. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusher, T.M.; Zipursky, A.; Bhutani, V.K. A Global Need for Affordable Neonatal Jaundice Technologies. Semin. Perinatol. 2011, 35, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, B.K.; Vreman, H.J.; Faber, K.; Lou, H.; Donaldson, K.M.; Amuabunosi, E.; Ofovwe, G.; Bhutani, V.K.; Olusanya, B.O.; Slusher, T.M. Phototherapy Device Effectiveness in Nigeria: Irradiance Assessment and Potential for Improvement. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2013, 59, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).