1. Introduction

In recent decades, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as one of the most transformative technologies in science and technology. From mastering games once thought to be uniquely human intellectual domains [

1,

2], to revolutionizing protein structure prediction [

3], AI has shown unprecedented capabilities in solving complex problems. In mathematics, where progress is often slow and dependent on deep intuition, researchers are beginning to explore how AI can act not as a replacement, but as a collaborator. For example, DeepMind has demonstrated that AI can guide mathematical intuition to uncover novel insights in representation theory and knot theory [

4]. This suggests that AI is not merely a computational tool but a partner in creative discovery.

The intersection of AI and mathematics is not restricted to pure theoretical advances. In physics, AI-based approaches have enabled breakthroughs in solving long-standing problems such as the quantum many-body problem [

8]. Similarly, large-scale reasoning systems like Minerva [

5] and symbolic-deduction models such as AlphaGeometry [

6,

7] have shown that language models can tackle complex quantitative reasoning and even Olympiad-level geometry. These successes illustrate that AI can support both the routine and the deeply creative aspects of mathematical and scientific inquiry.

Despite these advances, many mathematicians remain skeptical about the role of AI in their discipline. Mathematics is often perceived as a field grounded in rigor, proof, and absolute certainty—qualities that seem at odds with probabilistic AI systems. Communities like MathOverflow and Stack Overflow have expressed caution in permitting AI-generated content, establishing explicit policies restricting the use of generative AI tools in order to preserve standards of quality and originality [

9,

10]. While these concerns are understandable, they risk overlooking the potential of AI as an amplifier of human creativity rather than as a threat to intellectual integrity.

An additional layer of resistance has emerged from the use of AI-detection software in academic contexts. Systems such as Turnitin’s AI detector, while designed to prevent academic dishonesty, are prone to false positives and have been criticized for producing unreliable results [

11]. Institutions such as Vanderbilt University have gone so far as to disable these detectors, recognizing that they may discourage legitimate uses of AI for learning and research [

12]. For mathematicians and other researchers, such restrictive practices can hinder technological growth and innovation, as most active scholars already possess the background necessary to critically use AI tools and integrate them into their workflows.

Therefore, a paradox emerges: while AI has already proven its ability to make meaningful contributions to mathematics and related sciences, cultural and institutional barriers prevent many mathematicians from embracing it fully. This paper explores why mathematicians have been hesitant to adopt AI, and argues that rejecting AI tools or attempting to police their use through unreliable detection methods risks stifling the very innovation that has historically driven mathematical progress.

2. Why Mathematicians Resist AI

Despite the remarkable progress of artificial intelligence in mathematics and related sciences, many mathematicians remain hesitant to adopt these tools in their own work. This skepticism can be traced to three main factors: epistemological, sociological, and pedagogical.

2.1. Epistemological Concerns

Mathematics is fundamentally grounded in rigor, logical deduction, and proof. In contrast, modern AI systems such as large language models and neural networks operate probabilistically, producing outputs that may appear convincing but lack formal guarantees of correctness. Unlike the structured approach of theorem proving, AI models often generate “hallucinations”—false or misleading statements presented with high confidence. For mathematicians, this gap between certainty and approximation is problematic, since even a single flawed step can invalidate an entire argument. As a result, many view AI as unreliable for producing results that meet the strict epistemic standards of mathematics.

2.2. Sociological and Community Norms

Another reason for resistance lies in the norms of the mathematical community. Platforms such as MathOverflow and Stack Overflow explicitly discourage or forbid the posting of AI-generated answers [

9,

10]. These policies reflect the widespread concern that AI may generate incorrect or low-quality responses that dilute the value of carefully reasoned contributions. Moreover, mathematicians value originality and intellectual integrity; reliance on AI without critical oversight is often perceived as undermining these principles.

2.3. Pedagogical and Educational Risks

AI also raises concerns in educational contexts. When used by students or non-experts, AI tools often provide incomplete, superficial, or outright wrong solutions to mathematical problems. Unlike experienced researchers, who can validate AI outputs using established methods such as numerical checks, literature reviews, or alternative derivations, students may accept AI answers uncritically. This mismatch in expertise creates a risk: instead of fostering understanding, AI could reinforce misconceptions and weaken the development of rigorous problem-solving skills. For this reason, many mathematicians argue that AI should be reserved for expert use, where it can serve as a catalyst for discovery rather than a shortcut to answers.

In sum, resistance to AI in mathematics is not a rejection of technology per se, but rather a reflection of the discipline’s unique epistemological standards, community norms, and educational responsibilities. These concerns form the backdrop against which opportunities for responsible AI integration must be considered.

In order to ground these discussions in a concrete example, we now turn to a case study involving a deceptively simple problem on partial harmonic sums. We demonstrate how the same question, when posed by non-experts and by professional mathematicians, elicits drastically different outcomes from AI systems. This sets the stage for analyzing both the limitations and potential of AI in mathematics.

2.4. Case Study: The Impact of Context on AI Responses

To illustrate why mathematicians resist uncritical use of AI, consider the following example involving the sequence

This is a finite segment of the harmonic series, closely related to harmonic numbers. The problem is deceptively simple to state, yet subtle in structure. In fact, this very question has been discussed on MathOverflow [

13]. We contrast two scenarios in which the same mathematical query is posed to an AI system.

2.4.1. Case A: Query Without Context (Non-Mathematician)

A non-expert may pose the question to an AI in a vague form, such as:

“Is there an elegant positive recursive formula for ?”

Without additional context or constraints, an AI model often produces a superficial or even incorrect answer. It might suggest that no such formula exists, or offer a spurious recursion derived from heuristic manipulations. In particular, the AI is prone to hallucinations—statements presented with confidence but lacking logical or mathematical justification. The result is unhelpful for a learner, who may accept it uncritically.

This reflects the danger of AI in educational contexts: non-experts lack the background knowledge required to check, validate, or refine the AI output. The tool becomes a source of confusion rather than clarification.

2.4.2. Case B: Expert-Guided Query (Mathematician)

By contrast, consider how a professional mathematician might frame the same problem, as in the MathOverflow post [

13]:

“I am working with the expression . This can be written in terms of harmonic numbers as . Since the harmonic numbers satisfy a simple recursion , I am looking for a comparable recursion for . Ideally, should be expressed in terms of plus new positive contributions. Is there such a formula, and what is the asymptotic behavior of as ?”

Given this context, an AI system—especially when combined with the expert’s ability to validate and extend its output—produces a rigorous and meaningful answer. Indeed, one obtains the exact recurrence:

which can be interpreted as a discrete harmonic dynamical system. While the recurrence is not a simple “positive-only” extension, it is exact and useful.

Furthermore, by invoking the Euler–Maclaurin expansion for harmonic numbers, the asymptotic growth is shown to be logarithmic:

with explicit two-sided bounds available. This not only answers the original question, but also situates the result within the broader framework of analytic number theory and dynamical systems.

2.4.3. Discussion

The contrast between Case A and Case B highlights a central theme of this paper: AI is not inherently useful or harmful in mathematics, but its effectiveness depends critically on the expertise of the user. Non-experts may receive misleading results, while trained mathematicians can leverage AI as a powerful assistant for exploration, computation, and verification. This duality explains both the community’s skepticism toward uncritical AI use and the opportunities it presents for expert-driven research.

3. Case Study: Narrow AI Replies vs. Expert-Guided Answers

To make concrete the contrast we have been describing, we present two answers to the same mathematical question about

one typical of a context-free AI reply (Case A) and one produced under expert guidance (Case B). The original MathOverflow thread discussing this question is instructive and is cited below [

13].

3.1. Case A: A Narrow (and Potentially Wrong) AI-Style Response

Mock AI Reply (Non-Expert Prompt)

“There is no simple recursive formula for . Asymptotically , so the sequence grows like the natural logarithm. Therefore no simple additive recursion exists — the best one can say is .”

Why This Reply Is Misleading or Wrong

Over-simplification of asymptotics. Claiming as if it were an exact identity is false; in fact converges to zero slowly and the explicit first-order correction is of order with a specific coefficient (see Case B). Presenting only “” without the next-order term misrepresents the true behaviour and removes information essential for rigorous work.

Vague recurrence statement. Saying “no simple additive recursion exists” without demonstrating the structural obstruction (the dropped index k when passing to ) is unhelpful. A precise exact recurrence does exist (it involves a negative term and a new block-sum); the AI’s claim is therefore incomplete.

Lack of checks or references. The mock reply gives no identities, no harmonic-number representation, no numerical checks, and no references (e.g., the harmonic-number identity ). Non-expert users may accept such a terse answer and thereby be misled.

This pattern—succinct-sounding but underspecified output—is typical when AI models are given vague prompts without context, constraints, or a request for derivation and verification.

3.2. Case B: The Expert-Guided Answer (as Provided by an Expert / AI

with Mathematical Context)

Below we insert the professional answer supplied earlier (verbatim), followed by a short technical clarification.

The exact recursive formula for is the following interesting harmonic discrete dynamical system:

There is no simpler closed-form recursive relationship because the summation term involves terms that do not simplify to an elementary expression. This is due to the quadratic growth of the upper limit in the definition of . For practical computation, this recurrence can be used, but it requires summing terms per step, at least or obtaining strong bounds.

Upper Bounds on the Growth of

Recall that the sequence is defined by

Using harmonic numbers, we have the exact identity

where is the n-th harmonic number. From the Euler–Maclaurin expansion,

we obtain

Simplifying gives, for large k,

Expanding the logarithm,

which shows that the growth of is essentially logarithmic.

Using sharp bounds for harmonic numbers,

we deduce the following explicit upper bound:

which is extremely tight for all . For a simpler but looser bound, we also have

Minor Technical Clarification

The expert answer above is essentially correct and captures the key exact recurrence and the block structure. A small refinement in the asymptotic expansion is to display the natural centering around the dropped index: using

one finds

which is equivalent to the form

up to re-expansion of the correction terms. The important point is that the first-order correction is explicit and of order

, so the coarse statement “

” is true but incomplete for rigorous work.

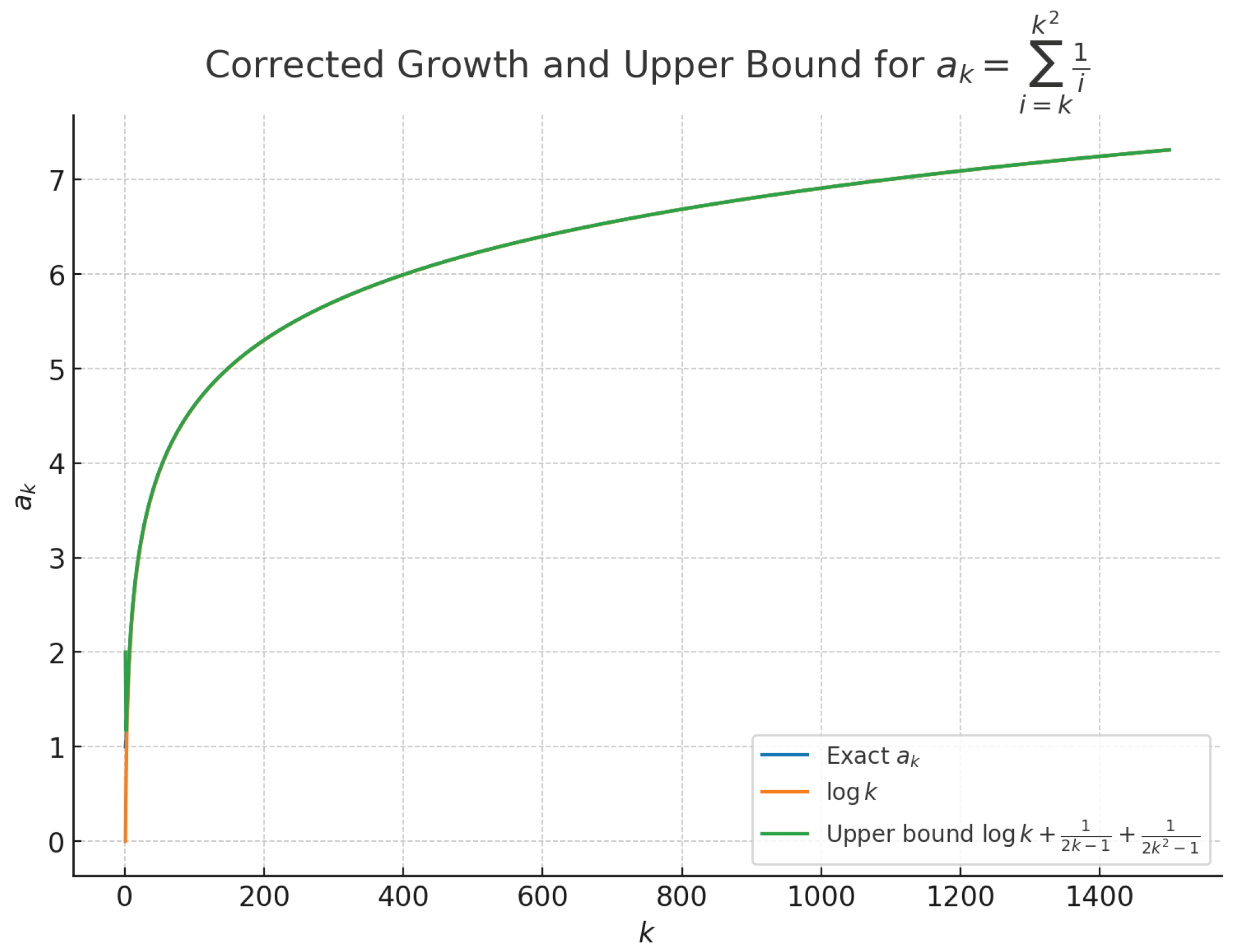

3.2.0.5. Numerical/Graphical Confirmation

The figure below (from the MathOverflow thread) visually confirms the logarithmic growth and the near-fit of the explicit upper bound.

3.3. Summary of the Two Cases

Case A (non-expert prompt): produces short, imprecise, and possibly incorrect answers (e.g. asserting or making vague negative claims) because the AI lacks context and the user lacks expertise to demand derivations and checks.

Case B (expert-guided prompt): yields an exact, verifiable recurrence and an accurate asymptotic expansion; the AI output—when steered by an expert to produce derivations, references, and numerical checks—turns into a useful research assistant.

The MathOverflow discussion referenced here is a good example of an expert community providing the context and verification needed to assess and refine such replies [

13].

The numerical table (

Table 1) and the accompanying plot (

Figure 1) together confirm the analytical observation: the sequence

grows logarithmically and stays remarkably close to

, with only a small positive bias that diminishes as

k increases. This reinforces the point that when AI is guided by expert-level context—through harmonic numbers, Euler–Maclaurin expansion, and bounding arguments—it can deliver convincing and mathematically rigorous results. In contrast, without such framing, the same problem elicits incomplete or misleading responses, highlighting the essential role of human expertise in directing AI effectively.

4. The Perils of AI Detection in Academic Research

A growing body of evidence highlights that automated AI-detection systems, while marketed as safeguards against academic dishonesty, pose significant risks to research integrity and the progress of scholarship itself. False positives, where genuinely human-written work is flagged as machine-generated, have already been documented in peer-reviewed studies and investigative journalism. Giray [

14] shows that false accusations of “AI plagiarism” not only harm individual scholars but also create a chilling effect on the dissemination of research. This danger is magnified for early-career researchers, whose academic reputations are particularly fragile.

Empirical studies further confirm the unreliability of detection tools. Elkhatat et al. [

16] demonstrate that commonly used classifiers cannot reliably distinguish between human and AI-generated text, while Tufts et al. [

17] provide systematic evidence of widespread inaccuracies even for state-of-the-art models. Alarmingly, Dixon and Clements [

19] argue that such failures dilute the efficacy of detection to the point of undermining academic integrity, shifting suspicion onto innocent researchers rather than deterring misconduct.

The risks are not merely technical but also social and ethical. A Stanford University study reported by *The Markup* [

15] revealed that international students are disproportionately targeted by false accusations, illustrating the bias these tools can amplify. In practice, the use of unreliable detection does not protect research but instead stigmatizes vulnerable groups and discourages innovation.

Forward-looking perspectives reinforce this conclusion. Akbar et al. [

18] argue that the solution to AI-assisted writing in education and research is not adversarial detection, but rather the design of AI-resilient assessments that emphasize transparency and critical thinking. In this view, adversarial detection regimes do not defend the values of science; they erode them. If adopted at scale, such policies risk creating an academic environment where suspicion replaces trust, and where the growth of notable research-especially in emerging fields where AI is already indispensable-is actively hindered.

In summary, while the impulse to regulate AI in research is understandable, the evidence suggests that detection-based approaches are both technically flawed and ethically dangerous. Rather than serving as a safeguard, they constitute a threat to academic freedom, equity, and the healthy integration of AI into the future of knowledge production.

5. Towards Responsible Integration of AI in Mathematics

Having shown why mathematicians are cautious and why adversarial detection is problematic, we now propose a constructive path forward. The goal is to enable mathematicians to harness AI’s productivity and exploratory power while preserving the discipline’s standards of rigor, reproducibility, and equity. Our recommendations are organized around three pillars: expert-guided use, educational design and training, and institutional policy that emphasizes transparency rather than policing.

5.1. Expert-Guided AI Use in Research

Mathematicians should treat AI as a tool for exploration and computation rather than an oracle. Practical practices include:

Always request derivations and explicit reasoning steps when using LLMs for mathematical tasks; follow up with independent numerical checks or symbolic verification (e.g., using a CAS or a formal proof assistant).

Require that any claim originating from an AI suggestion be accompanied by a short verification trace: (i) the transformation of the prompt, (ii) the intermediate computations or references used, and (iii) numerical checks for representative instances.

Use modular, reproducible workflows (versioned code, notebooks, or small scripts) so other researchers can replay and audit AI-assisted steps.

These practices align with publishing norms that call for clear documentation of methods and tool usage; several journals and professional bodies now explicitly require disclosure of AI assistance in the Methods or Acknowledgments sections and prohibit attributing authorship to AI systems [

14,

19].

5.2. Educational Opportunities and Assessment Design

Rather than banning AI tools for students, institutions should teach students how to use them critically. Pedagogical measures include:

These approaches reduce the incentives for cheating while turning AI into a scaffold for learning instead of a shortcut.

5.3. Institutional Policy: Disclosure, Verification, and No-Oracle Rules

Policies should focus on transparency and verification, not on unreliable stylistic detection. Concretely we recommend:

Mandatory disclosure. Authors and students should declare the use of AI tools in a short statement (Methods / Acknowledgments for papers; a cover note for student work). This practice is increasingly recommended by major publishers and editorial bodies [

14,

19].

Prohibit AI authorship. Since AI systems cannot take responsibility, they must not be listed as authors; this is the prevailing position of leading journals and ethics committees [

14].

Do not use detector scores as sole evidence. Given well-documented false positives and biases in detectors, institutions should not base disciplinary actions on detector outputs alone; instead use human review, process-based inspection (version history, logs, notebooks), and direct verification [

14,

16,

17,

19].

Protect confidential research. Researchers should not input unreleased or sensitive manuscript content into public LLM interfaces; this concern is highlighted by institutional warnings and guidelines on AI use [

15].

Support training and infrastructure. Universities should provide access to vetted AI services (on-premise or privacy-respecting APIs), reproducible compute environments, and training for faculty and students on responsible AI use [

18].

5.4. Why This Matters: Logical Justification

The case against aggressive detection is not merely pragmatic but logical:

Detectors are unreliable. Empirical work shows that detectors have unacceptably high false-positive rates in many realistic settings (including bias against non-native speakers), so they cannot be used as definitive evidence of misconduct [

15,

16,

17].

Policing inhibits innovation. If researchers fear that using AI—even responsibly and with disclosure—will trigger reputational harm or rejection, they will avoid experimenting with tools that could accelerate discovery. This is especially damaging in mathematics, where computational exploration often suggests conjectures and heuristics that lead to proofs.

Proof is the final arbiter. In mathematics correctness is determined by proof and verification, not by the provenance of a draft. Institutional practice should therefore privilege verification workflows (proofs, checks, reproducible computations) over stylistic authorship attributions.

5.5. Practical Checklist for Journals and Departments

For immediate adoption, we suggest this short checklist:

Require an AI usage statement in submissions and student portfolios. (What was used and for which step?)

Require reproducible artefacts: code, notebooks, seeds, and small test inputs for any AI-assisted computation.

Use detector tools only as triage aids (e.g., to flag items for manual review), never as sole evidence for adjudication.

Provide mechanisms for appeal and human review when detectors are used.

Train faculty and students in AI literacy and verification techniques (numerical checks, CAS validation, formal tools).

Adopting these measures will preserve the epistemic standards of mathematics while allowing researchers to benefit from AI-driven exploration, faster computation, and broadened collaboration. In the absence of such policies, blanket bans or detector-driven enforcement will simply transfer the costs of innovation from those who experiment responsibly onto the broader research community.

6. Case Studies and the Necessity of Professional AI Use

While earlier sections outlined responsible practices and institutional policies, it is equally important to consider the consequences of banning AI entirely in scientific and mathematical communities. Blanket prohibitions against AI usage constitute a form of scientific suppression, which hinders exploration, innovation, and productivity. In fields such as mathematics, physics, astronomy, and beyond, AI acts as a professional tool that can accelerate discovery, much like a microscope or a supercomputer.

However, unrestricted use of AI without proper guidance is dangerous. This is analogous to handing a two-year-old a live flame: the potential for benefit exists, but so does the risk of harm. In mathematical research, misuse could lead to false conjectures, unreproducible results, or misinterpretation of computational outputs [

16,

17,

19].

For large, reputable communities—such as professional journals or platforms like MathOverflow—AI usage should not be prohibited. Instead, it should be formally recognized in the community’s code of conduct. Such forums accept submissions from both professional and early-stage researchers who have sufficient mathematical knowledge to contribute meaningfully. Incorporating AI use into the rules allows members to leverage tools responsibly while maintaining the platform’s quality and reliability [

9,

10].

To operationalize this, community moderators should:

Supervise questions and answers where AI tools have been used.

Evaluate AI-assisted contributions for correctness, completeness, and alignment with the community’s standards.

Revise or provide feedback on contributions that do not meet quality standards, rather than removing them outright.

Encourage responsible AI usage by promoting best practices and reproducible workflows [

14,

15].

By implementing these measures, AI can become a professional ally in knowledge creation rather than a prohibited shortcut. Properly guided AI usage preserves the epistemic standards of mathematics and other sciences, facilitates collaboration, and ensures that contributions remain credible and verifiable. In contrast, forbidding AI risks making scientific platforms less useful, discouraging experimentation, and ultimately slowing the pace of discovery.

7. Conclusion: Embracing AI as a Professional Scientific Tool

The integration of AI into mathematics and related scientific disciplines is no longer optional—it is inevitable. Our analysis demonstrates that prohibiting AI usage is counterproductive and, in effect, a scientific disservice. Detectors are unreliable, blanket bans suppress innovation, and preventing researchers from responsibly using AI risks slowing discovery in fields that rely on computation, modeling, and exploration [

16,

17,

19].

Instead, AI should be treated as a professional tool, akin to a telescope, microscope, or supercomputer. Its use must be guided by expertise, clear verification practices, and community standards. Researchers must remain accountable for results, verifying all AI-assisted outputs and documenting workflows transparently [

14,

15,

18].

For large scientific communities and reputable platforms, such as journals or MathOverflow, incorporating AI into codes of conduct is essential. Moderation should focus on quality, verification, and feedback rather than strict prohibition, ensuring that AI contributions are professional, accurate, and beneficial to the broader research community [

9,

10].

Ultimately, the responsible integration of AI offers unprecedented opportunities for mathematical discovery, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and educational enrichment. By embracing AI as a professional ally, while enforcing rigorous verification and ethical practices, the scientific community can harness its full potential without compromising rigor, integrity, or equity.

In short, responsible AI use is not merely a convenience; it is a scientific imperative. Preventing researchers from leveraging these tools is a form of intellectual suppression, whereas guided, professional AI usage empowers innovation, maintains epistemic standards, and prepares the next generation of scholars to navigate an AI-enhanced scientific landscape.

8. Future Research Directions: AI as a Catalyst for Mathematical Discovery

The work presented in this paper lays the foundation for responsible AI integration in mathematics, but it also opens exciting avenues for future research. One promising direction is the systematic use of AI to **tackle open conjectures** in number theory and related fields.

8.1. AI-Guided Exploration of Conjectures

Traditionally, open problems are considered beyond the reach of current techniques. However, AI offers a **new computational paradigm** to explore patterns, test lemmas, and generate candidate strategies for proofs. Future research can focus on:

Developing AI-driven frameworks to **systematically test conjectures** by generating and verifying instances, computing numerical evidence, and suggesting possible generalizations.

Combining symbolic reasoning, formal proof assistants, and large language models to **propose candidate theorems** and check their logical coherence before human verification.

Leveraging AI to identify **heuristics or patterns** that might remain invisible to traditional approaches, thus accelerating the pathway from conjecture to proof.

8.2. Expanding Number Theory Techniques with AI

Despite the richness of current number-theoretic methods, many mathematicians remain hesitant to treat AI as a tool for advancing the field. Future work should explore:

Creating AI-assisted methods to discover, refine, and organize lemmas, corollaries, and proof strategies in number theory.

Establishing reproducible pipelines where AI suggestions are **verified, iterated, and incorporated** into formal proofs, ensuring logical rigor without fatal gaps.

Designing experiments to **benchmark AI’s impact** on long-standing open problems, demonstrating its ability to accelerate discovery while preserving mathematical correctness.

8.3. Bridging Human Expertise and AI Capabilities

The ultimate goal is not to replace mathematicians but to **amplify their intuition and productivity**. By integrating AI as a co-explorer:

Researchers can explore vast combinatorial or number-theoretic spaces that are otherwise infeasible manually.

AI can serve as a testbed for conjectures, providing preliminary evidence, counterexamples, or structured guidance for further investigation.

This symbiotic approach allows the community to advance knowledge faster, transforming “currently open” problems into tractable challenges within a rigorously controlled framework.

In conclusion, future research should embrace AI not merely as a computational assistant but as a strategic partner in mathematical discovery, enabling the rigorous exploration of open conjectures, the development of new techniques, and the accelerated evolution of number theory and related domains.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to advancing our understanding and contribution to the Hughes-Keating-O’Connell (OKH) conjecture, which has been significantly approached through the development of new techniques and the integration of AI tools. We acknowledge the foundational work presented in Zeraoulia, R.,

On the Hughes–Keating–O’Connell Conjecture: Quantified Negative Moment Bounds for via Entropy–Sieve Methods Revisited, Preprints 2025, 2025090489.

https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202509.0489.v1, which inspired and guided aspects of the present research. [

20] The author also thank all colleagues and collaborators who provided valuable discussions and insights, contributing to the responsible and innovative use of AI in mathematical exploration.

References

- Silver, A. Huang, C. J. Maddison, et al., “Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search,” Nature, 529:484–489, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Silver, T. Hubert, J. Schrittwieser, et al., “A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play,” Science, 362(6419):1140–1144, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Jumper, R. Evans, A. Pritzel, et al., “Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold,” Nature, 596:583–589, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Davies, P. Veličković, L. Buesing, et al., “Advancing mathematics by guiding human intuition with AI,” Nature, 600:70–74, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Lewkowycz, A. Andreassen, D. Dohan, et al., “Solving Quantitative Reasoning Problems with Language Models,” arXiv:2206.14858, 2022. arXiv:2206.14858.

- T. Trinh, H. Le, A. Jain, et al., “Solving Olympiad Geometry Without Human Demonstrations,” arXiv:2404.06405, 2024. arXiv:2404.06405.

- T. Trinh, H. Le, A. Jain, et al., “AlphaGeometry-II: Large Language Model Guided Symbolic Deduction for Geometry Theorem Proving,” arXiv:2502.03544, 2025. arXiv:2502.03544.

- G. Carleo and M. Troyer, “Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks,” Science, 355(6325):602–606, 2017. [CrossRef]

- MathOverflow Help Center, “What is this site’s policy on content generated by generative artificial intelligence tools?” https://mathoverflow.net/help/gen-ai-policy.

- Stack Overflow Help Center, “What is this site’s policy on content generated by generative AI tools?” https://stackoverflow.com/help/ai-policy.

- Turnitin Blog, “Understanding false positives within our AI writing detection capabilities,” Mar 16, 2023. https://www.turnitin.com/blog/understanding-false-positives-within-our-ai-writing-detection-capabilities.

- Vanderbilt University, “Guidance on AI Detection and Why We’re Disabling Turnitin’s AI Detector,” Aug 16, 2023. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/brightspace/2023/08/16/guidance-on-ai-detection-and-why-were-disabling-turnitins-ai-detector/.

- MathOverflow. “Is there an elegant recursive formula for ak=∑i=kk21i?” MathOverflow, 2024. https://mathoverflow.net/q/499543.

- L. Giray, “The Problem with False Positives: AI Detection Unfairly Accuses Scholars of AI Plagiarism,” The Serials Librarian, vol. 88, no. 1, pp. 27–34, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Stanford University study (reported by The Markup), “AI Detection Tools Falsely Accuse International Students of Cheating,” The Markup, Aug 14, 2023. https://themarkup.org/machine-learning/2023/08/14/ai-detection-tools-falsely-accuse-international-students-of-cheating.

- A. M. Elkhatat, K. Elsaid, and S. Almeer, “Evaluating the efficacy of AI content detection tools in differentiating between human and AI-generated text,” International Journal for Educational Integrity, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tufts, X. Zhao, L. Li, et al., “A Practical Examination of AI-Generated Text Detectors for Large Language Models,” arXiv:2412.05139 [cs.CL], 2024. arXiv:2412.05139.

- M. S. Akbar, et al., “Beyond Detection: Designing AI-Resilient Assessments with Automated Feedback Tool to Foster Critical Thinking,” arXiv:2503.23622 [cs.EDU], 2025. arXiv:2503.23622.

- H. Dixon and R. Clements, “The failures of LLM-generated text detection: false positives dilute the efficacy of AI detection,” Center for AI and Data Ethics, University of San Francisco, 2024. https://www.usfca.edu/sites/default/files/2024-05/ai_detection_case_study.pdf.

- R. Zeraoulia, “On the Hughes–Keating–O’Connell Conjecture: Quantified Negative Moment Bounds for ζ′(ρ) via Entropy–Sieve Methods Revisited,” Preprints 2025, 2025090489. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).