1. Introduction

Oral health issues, including dental caries, periodontal diseases, and tooth loss, are not only major public health concerns but also have far-reaching effects on overall well-being and oral health-related quality of life [

1,

2]. Untreated dental caries continues to pose a substantial public health burden in various regions worldwide, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean, where over two billion individuals, including a significant proportion of 12-year-olds, are affected [

3]. Despite global efforts to curb this issue, the most recent findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study reveal that the worldwide prevalence of untreated dental caries has only declined by a marginal 4% over the last decade. This rate of reduction is notably slower than the more pronounced decrease observed over the preceding 30 years[

4].The modest decline has been largely attributed to increased awareness, often fostered through targeted oral health screening initiatives.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, similar challenges persist. [

5] reported that, although the prevalence of dental caries in their study population did not significantly exceed national or regional averages possibly due to local dietary patterns critical oral health concerns remained. A substantial number of carious lesions were left untreated, and this was due to lack of access to dental services. The consequences of neglected dental caries in early childhood have negative consequences which encompassing pain, impaired mastication, sleep disturbances and missing out school attendance. Children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds are especially susceptible to such conditions, as highlighted by[

6] and [

7].

If not addressed promptly, dental caries may adversely impact a child’s physical growth, cognitive development, systemic health, and general quality of life. While typically not life-threatening, untreated caries can progress to serious complications, such as abscess formation, cellulitis, premature tooth loss, and, in extreme cases, hospitalization or the administration of general anesthesia[

5].

In the South African context, data from the National Oral Health Policy and Strategy (NOHPS) 2024–2035 indicates that approximately 60% of six-year-old children exhibit dental decay in their primary teeth, with 55% of these cases remaining untreated. [

8] further established a statistically significant correlation between age and the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index, suggesting an age-related increase in the prevalence of untreated caries. Although dental caries is highly preventable through effective oral hygiene practices and improved dietary habits [

9], it remains a pressing concern, especially among children. This underscores the urgent need for comprehensive oral health education and routine screening within school systems.

Furthermore, untreated dental caries is a widespread issue throughout South Africa’s nine provinces. In Gauteng province, for example, prevalence rates reach 37% among children aged 4–5 and rise to 50% among six-year-olds (NOHPS, 2024–2035). Although overall caries prevalence in South Africa appears moderate in comparison to global data, [

10] found that over 89% of affected children had untreated caries. Alarmingly, approximately 70% of dental caries in children aged 6, 12, and 15 remain unaddressed, with serious implications for their daily functioning. These include interference with eating, sleeping, school attendance, and, in severe cases, infection and the need for tooth extractions [

11] .

Given these challenges, prioritizing early oral health screening and preventive education are essential. Providing children with foundational dental care knowledge and practices during their formative years will instill lifelong oral hygiene habits, thereby mitigating the incidence and impact of oral diseases that are largely preventable. Promoting oral health literacy and preventive care among school-aged children is equally essential to improving long-term oral health outcomes and aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 3, which advocates good health and well-being for individuals across all age groups. Therefore, the study identified a need to conduct screening among the primary school children to identify, treat or referral to such oral disease at initial stages to avoid those complications that might occur if left untreated as part of practicing good health for individuals.

2. Research Methods and Design

2.1. Study Design

The study used a quasi-experiment design with pre-test, intervention, and post-test phases undertaken to assess the oral health status of school children within selected primary schools around Ga-Rankuwa in the Tshwane District, South Africa. Dental screening was conducted by dental professionals examining children's mouths and teeth at school and letting parents know about their child's oral condition and treatment needs. For children requiring treatment, personalized referral letters were given to children for them to attend dental appointments. The dental screening was supplemented with oral health motivation using oral health education material and also demonstration on brushing procedures as part of intervention. Quantitative data in descriptive approach was collected using screening forms.

2.2. Setting

For this study, research activities were carried out in primary schools situated in Ga-Rankuwa, a township within the City of Tshwane, located in the Gauteng Province, South Africa. The City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality comprises three distinct school districts: Tshwane West, Tshwane North, and Tshwane South.

2.3. Study Population, Sample Size and Sampling

The study used purposive sampling techniques to select schools around Tshwane west district circuit. The selected five (5) schools were those serviced by Sefako Makgato Health Science University (SMU) oral health during outreach program. Each school among all five selected schools contribute equally according to the number of registered school children from grades 3 to 7. In each selected school, classes were stratified by grades, and simple random sampling was used to choose one class per grade. Children within the selected classes form part of the study considering their willingness to participate. Approximately 390 primary school children were randomly selected and participated willingly in the study.

2.4. Data Collection

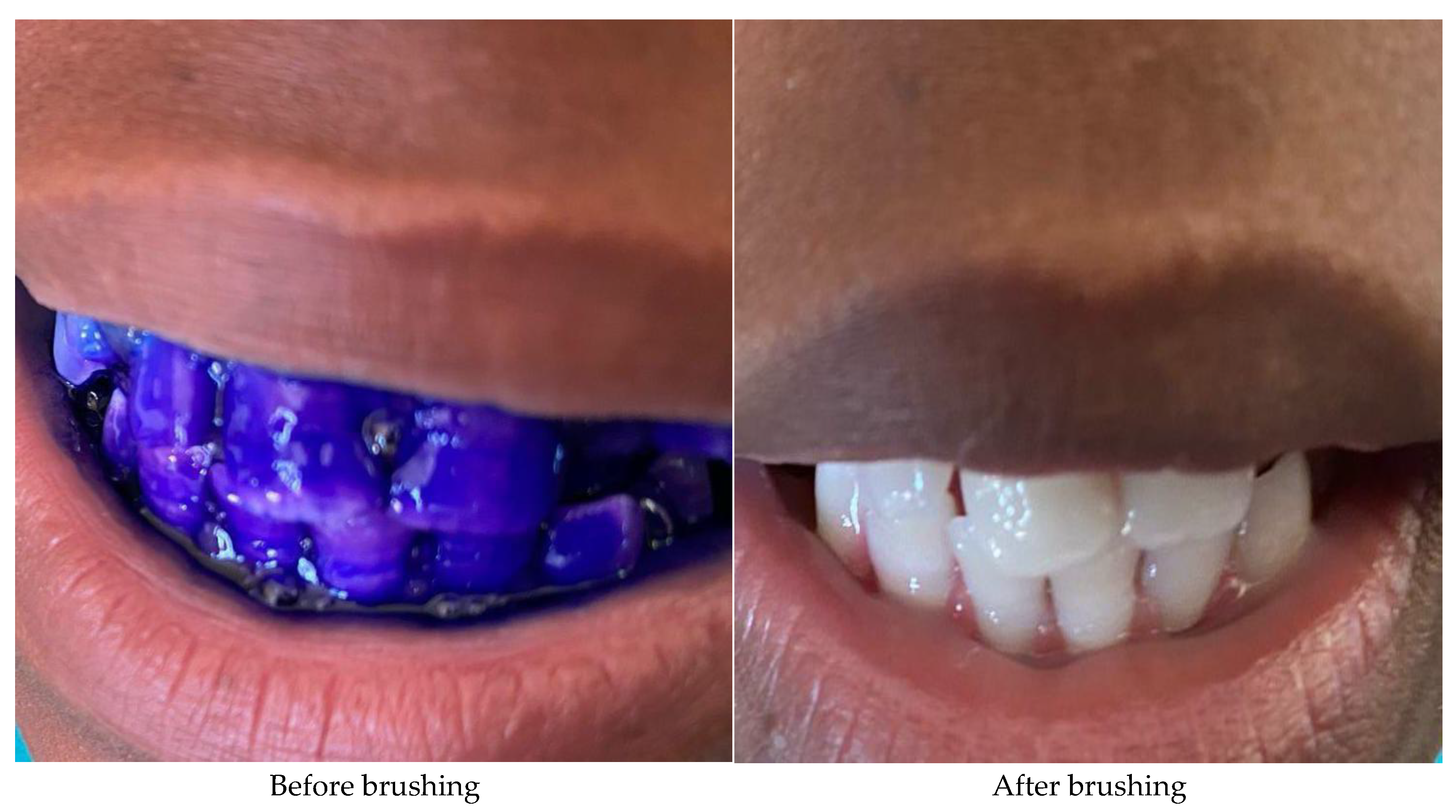

Data was collected using a dental screening form which was completed by dental health practitioners assessing the oral health status of school children within selected primary schools. Dental screening was conducted in different classrooms, whiles children are sitting on a chair and under direct light using dental probes and mirrors for children. The caries assessment was done with DMFT/ dmft calculated accordingly and plaque index score were also recorded in each school children who participated in the study. During the intervention phase, age-appropriate oral health education materials were disseminated teaching children good oral health practices and data was also collected through demonstration and observation of brushing procedures.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data was captured on the MS Excel spreadsheet, cleaned , coded and analysed using IBM SPSS software, with descriptive and inferential statistical methods and various statistical tests. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed to assess the oral health status of school children within selected primary schools before and after the intervention.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The University of Limpopo Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (TREC/123/2024: PG).Additionally, permission to conduct the study was given by the Basic Department of Education, Gauteng Province, Tshwane West Circuit Management, and principals of the five selected primary schools. The study required parental informed permission and child assent before beginning. The principle of beneficence was followed, guaranteeing that no harm is caused to participants during the research. The participants, were fully informed about the purpose of the study, assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and told that anyone could drop out at any time, had given informed. Alphabetical codes were used to identify the questionnaire data.

3. Results

3.1. Dental Health Outcomes of Children

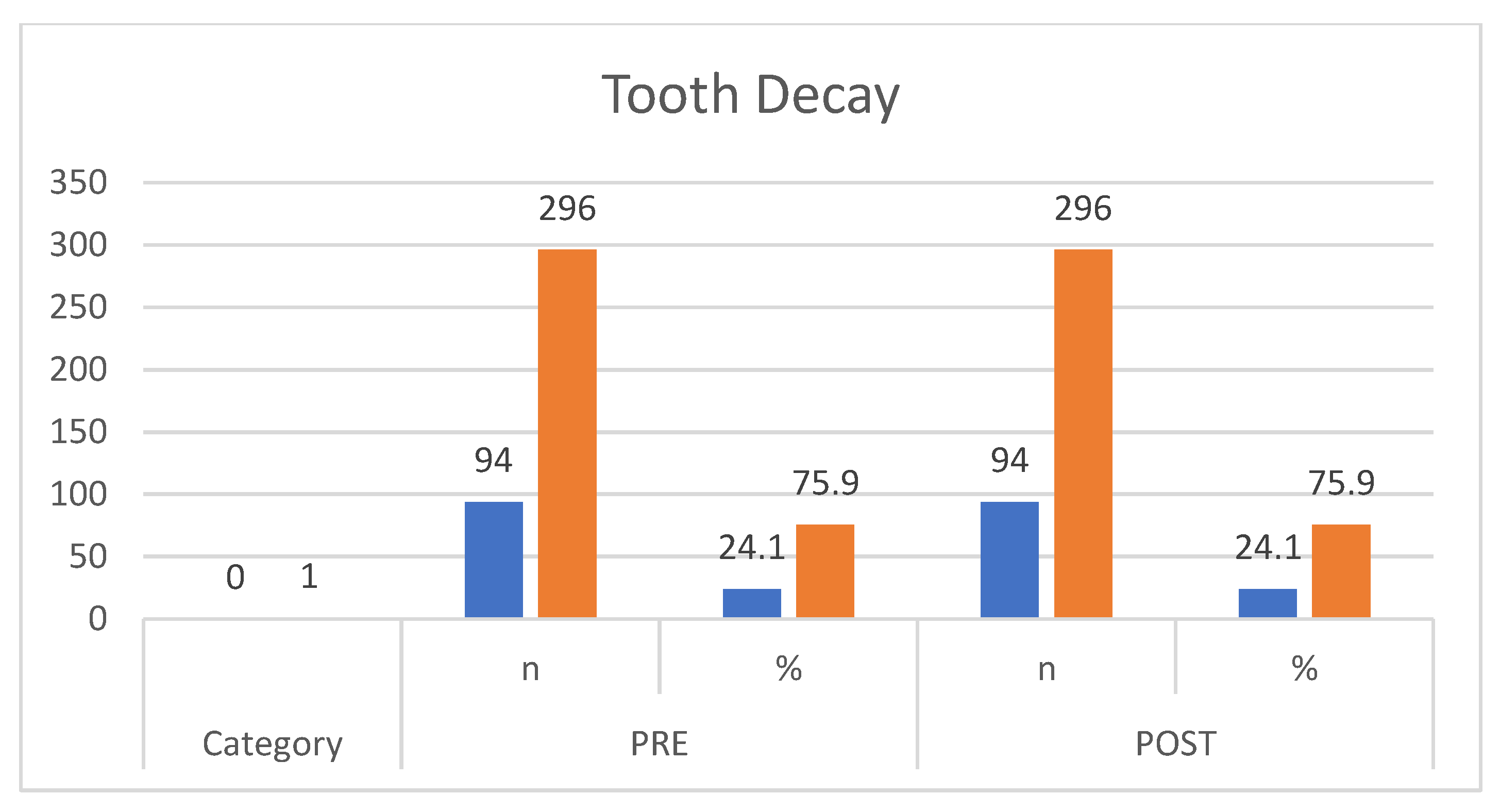

Figure 1 shows the proportion of children with tooth decay. Prior to screening, 75.9% of participants exhibited dental caries, while only 24.1% showed no signs of decay. Following the intervention, these proportions remained unchanged.

3.2. Plaque Index Scores

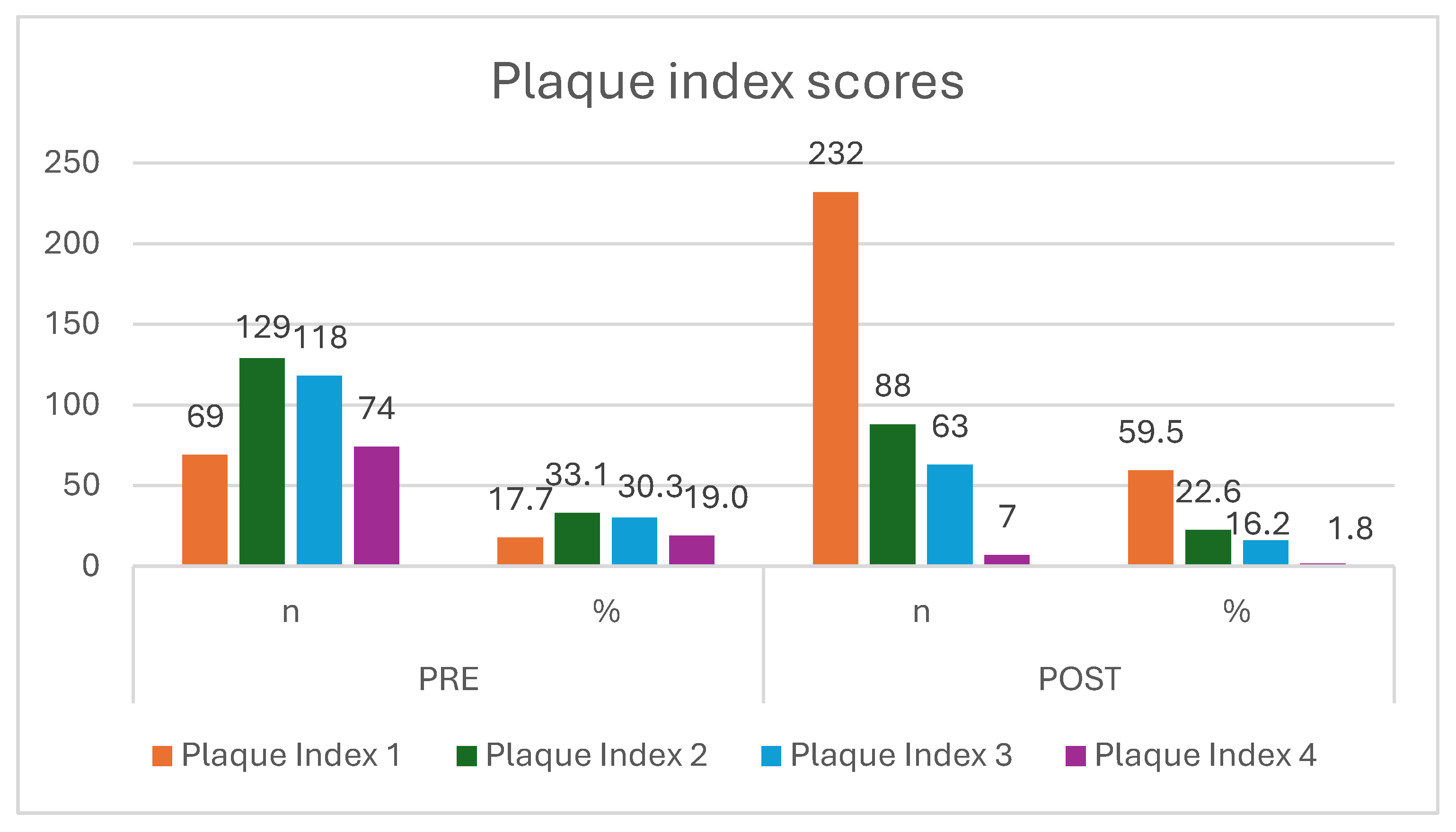

The plaque index scores of participants are reported at the

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The participants’ oral hygiene care improved after reported high plaque score (n=74;19.0%) pre intervention which decreases (n=7;1.8%) post intervention. The improvement also displayed on those with optimum oral hygiene (n=69;17.7%) pre intervention as compared to post intervention (n=232;59.5%). Nevertheless, those with poor oral hygiene as indicated on

Figure 3 with 100% plaques score were 30.3% pre intervention as compared to reduced post intervention (n=63;16.2%).

3.3. Decayed Missing Filling Teeth- DMFT/ dmft Score

Table 1 shows zero recorded of dmft /DMFT score pre (63.1%) and post (76.9%) intervention on dmft and pre (50.8%) post (59.2%) intervention and on DMFT during dental screening for children. The proportion of dmft in primary teeth recorded (37.3%) pre intervention higher than post intervention (23.2%). Additionally, the record of DMFT in permanent teeth pre intervention (49.2%) compared to the post intervention (40.8%). However, there are no observable changes in the treatment during pre and post intervention (75.9%). Though, the demand increased for extractions (31.3%) and the need for preventative measures also increased post intervention (74.7%). The referral pre intervention (75.9%) as compared to post intervention (39.2%).

4. Discussion

Oral health, though crucial to overall well-being, is often overlooked in public health. Dental issues, especially in children, can lead to long-term health and developmental challenges if not addressed early [

1,

2]. School-based screenings aim to identify problems early, yet their impact remains mixed. While they may improve awareness and hygiene behaviors [

12,

13] , this study found no reduction in caries prevalence 75.9% of children had decay both before and after intervention likely due to the absence of clinical treatment. However, evidence suggests that incorporating hands-on, skills-based education may help reduce caries and plaque[

14]. Lasting improvements require comprehensive strategies that include not only education and screening but also treatment and follow-up[

15,

16] This study addressed that gap by providing referrals, though its short duration may have limited measurable outcomes, reflecting a common challenge in brief interventions.

4.1. Effectiveness of Screening: A Case for Early Detection

The study revealed that 75.9% of children had dental caries both before and after the screening, reflecting a persistent lack of access to treatment. Globally, untreated dental caries remains a major health concern, especially among children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who face greater vulnerability [

3,

6,

7,

15]. The long-term effects ranging from pain and infection to impaired growth and development are well documented[

4,

8] .

While early screening has reduced total tooth loss by enabling timely referrals and preventive care like fluoride application[

17] its effectiveness is questioned when not coupled with direct treatment. Identifying problems without addressing them often leads to worsening conditions, as emphasized by[

18,

19]. Still, screenings provide valuable data for planning and can guide preventive efforts, especially when integrated with supervised brushing and hygiene education[

20,

21]. In this study, increased demand for extractions (31.3%) and preventive care (47.7%) post-screening suggests improved awareness. However, the preference for extractions may reflect barriers such as cost, transport, or limited-service availability often leading families to opt for quicker solutions[

22] With most public services focusing on extractions due to resource constraints [

23], there's an urgent need to rebalance priorities toward prevention and oral health promotion. Continued research and inclusive policies can help shift the focus from curative care to long-term oral health improvement.

4.2. Screening Improves Oral Hygiene Practices in Children

The study recorded a significant drop in high plaque scores from 19.0% to 1.8% among children with poor oral hygiene (70–100% plaque index), indicating that school-based interventions can lead to immediate improvements in hygiene practices[

24]However, the decline in children classified with good oral hygiene from 33.1% to 22.6% raises concerns about the sustainability of these gains without continued support. Parental involvement, especially through practices like Parental Supervised Brushing (PSB), is critical to reinforce healthy routines. Yet, PSB often faces obstacles due to behavioral resistance and inconsistent home environments[

25]. While schools can initiate behavioral change, long-term success relies more on parental guidance and intrinsic motivation[

26] .Access to dental services also depends on socioeconomic factors, with higher parental education and awareness linked to more frequent dental visits for children[

27,

28]. In underserved areas, awareness alone may not lead to action due to cost and access barriers[

29]. Without integration into broader social support systems from parents and other role players , initial improvements never last for longer. Regarding oral hygiene, parents are not just a good role model in terms of timing, frequency and duration of tooth brushing but they should have knowledge and manage to demonstrate completely and effectively brushing should be done[

30,

31]. Therefore, lasting oral health outcomes require a dual approach to school-based education supported by consistent parental engagement at home.

4.3. Plaque Control as Measure of Oral Hygiene Practices

A noticeable improvement in oral hygiene practices was observed following the implementation of oral health education and supervised toothbrushing sessions. Prior to the intervention, a significant portion of participants exhibited moderate plaque levels, with 19.0% falling into this category. Post-intervention, this figure declined dramatically to just 1.8%. Similarly, individuals classified as having mild plague score increased from 17.7% before the intervention to 59.5% post intervention. Further analysis revealed that participants with extensive plaque score as indicated by a 100% plaque score decreased from 30.3% before the intervention to 16.2% after the intervention. These outcomes reflect a substantial enhancement in oral hygiene standards among participants, attributable to the educational and brushing sessions as part of the practical measures introduced during the intervention phase.

The results reflect a significant enhancement of the participants' oral hygiene following the intervention, contrary to the study conducted by[

16] which reported the improvement in oral hygiene status and dental caries, but no reduction in plaque levels. However, these findings align with existing literature emphasizing the efficacy of educational interventions including brushing up on improving oral hygiene and reducing plaque levels[

32].Similar study demonstrated a significant reduction of plaques using a Green Vermillion Index (GVI) from 3.52 to 2.64 one week after an educational program, with the lowest value of 1.44 observed at three months, although the population differs as the study involves adolescents while the current study was focused on middle childhood. In addition, a slight increase to 2.52 was noted at six months, underscoring the necessity for ongoing educational efforts to sustain oral health improvements[

32] Furthermore, there is a need for continues assessment even after educational intervention is still a priority for the oral health practices and behaviours to change into a habit.

4.4. DMFT/dmft Scores: Indications of Systemic Gaps in Oral Health Care

The study revealed that a notable number of children recorded a dmft/DMFT score of zero, with post-intervention improvements observed dmft zero scores increased from 63.1% to 76.9%, and DMFT zero scores rose from 50.8% to 59.2%. Cases of dental caries in both primary and permanent teeth declined (dmft > 0 from 37.3% to 23.2%; DMFT > 0 from 49.2% to 40.8%). While this indicates some positive shift, the higher prevalence compared to[

4,

11] findings underscore persistent challenges, especially in the absence of treatment pathways[

18,

19]. External factors such as reduced access to preventive care with poor oral hygiene and regional disparities in water fluoride levels[

8], may have further influenced outcomes. These findings reinforce the call for stronger prevention focused systems rather than curative-dominated services.

Although referrals declined post-intervention (from 75.9% to 39.2%), the importance of linking screening to functional dental care remains critical. Early preventive visits have been shown to reduce the need for operative procedures and studies in South Africa[

22] urge a re-evaluation of oral health strategies to reduce extractions and improve child oral health, school attendance, and overall well-being with the similar sentiment that the Gauteng Department of Health Ministry must reevaluate current oral health programs to improve health service which will reduce the prevalence of dental caries and large quantity of extractions performed.

4.5. Limited Impact of Screening on Treatment Access

The consistent 75.9% treatment rate before and after screening highlights that identification alone does not improve access to care. Access factors include social, economic and political causes such as workforce shortages, limited facilities, and caregiver hesitancy continue to restrict treatment uptake, particularly in underserved communities, leading to negative outcomes and inequality oral health services[

33]. Critics argue that without financial subsidies, mobile dental clinics, or policy-driven interventions, screenings are merely observational rather than transformative[

34]. [

35]expressed that social determinants’ discrepancies such as family condition and culture, health demands, affordability and availability of services, can affect dental health access and equality which contributes to the impact on oral health outcomes. Therefore, addressing these factors can improve access to dental services and can pave the way for achieving universal health coverage. These social determinants result in underservices of poorly and disadvantaged communities causing lack of access to dental services. Consequently, the reduced access resulted in shift of treatment to more curative measures than preventive effects, which then affect OHRQoL outcomes because people suffer from pain, functional and psychological impact[

11,

20] . Similarly , low education contributes to lowering the odds of dental services access irrespective of oral health behaviour and status [

36]. A more effective strategy would involve coupling screening with accessible treatment, preventive services like school-based fluoride programs, and stronger parental involvement[

14] . Advocates argue that screening raises awareness and facilitates early intervention, while critics highlight its inherent limitations in producing tangible health improvements without integrated treatment pathways. Only through such comprehensive measures can school-based dental programs translate awareness into measurable improvements in children's oral health.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

The initiative emphasized collaboration drawing support from educators, healthcare professionals, and parents to ensure that the program was both practical and sustainable. Outcomes will be measured not only through changes in dental health indicators, such as plaque scores, but also through observable improvements in school children’s engagement and awareness and improvement of oral health practices for children. Despite its immediate success, one of the notable limitations of the study is the relatively short follow-up period. Without longer-term data, it is difficult to determine whether the observed improvements in behavior and oral health status can be maintained over time.

4.7. Implications

The findings from the study carry important implications for how oral health promotion and screening is approached within South African primary schools, particularly in under-resourced districts like Tshwane. By implementing a structured, context-sensitive educational intervention, the research not only highlighted existing gaps in oral hygiene practices but also demonstrated the potential for schools to act as meaningful platforms for preventive health care. The following important aspects were also addressed:

Repositioning Schools as Platforms for Preventive Health: The study reinforces the idea that schools are not merely sites of academic instruction but also crucial environments for health promotion. By embedding oral health education and dental screening into the everyday routines of primary school learners, the intervention demonstrated how early-life educational spaces can serve as powerful agents for establishing lifelong health habits.

Addressing Health Inequities Through School-Based Access: The study underscored how school-based interventions can help counterbalance inequities in access to oral healthcare, particularly in underserved communities like those within parts of Tshwane. In areas where clinics may be distant or financially inaccessible, the school offers a uniquely reachable and inclusive venue for care.

5. Conclusions

The results illustrate that the implementation of school-based oral health education and dental screening initiatives led to a marked reduction in high plaque levels among participating children. Although the intervention did not yield measurable changes in the status of existing tooth decay, notable progress was evident in the form of improved plaque control. These outcomes suggest a positive shift in daily oral hygiene behaviors and awareness. Nonetheless, the consistent rate of untreated cases, coupled with a growing demand for extractions and preventive services, points to persisting challenges in accessing follow-up clinical care. The sustainability of these gains appears closely linked to ongoing parental engagement and complementary support within the home environment. Overall, the findings emphasize the value of combining educational, preventive, and community-based efforts to strengthen oral health outcomes and ensure long-term benefits for school-aged children.

Author Contributions

E Musekene conceptualized the manuscript and wrote the manuscript under the guidance of supervisor T Netshapapame and co-supervisor Prof DT Goon who extensively reviewed the manuscript for improvement as part of the supervision.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

There are no any other conflict interests.

References

- Yactayo-Alburquerque MT, Alen-Méndez ML, Azañedo D, Comandé D, Hernández-Vásquez A. Impact of oral diseases on oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review of studies conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2021;16(6):e0252578. [CrossRef]

- Duangthip D, Chu CH. Challenges in oral hygiene and oral health policy. Front Oral Health. 2020; 1: 575428. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio FC, Bönecker M, Paiva SM, Martignon S, Ricomini Filho AP, Pozos-Guillen A, et al. Dental caries prevalence, prospects, and challenges for Latin America and Caribbean countries: a summary and final recommendations from a Regional Consensus. 2021;35:e056. [CrossRef]

- Collaborators G 2017 OD, Bernabe E, Marcenes W, Hernandez CR, Bailey J, Abreu LG, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. 2020;99(4):362–73. [CrossRef]

- Olatosi OO, Oyapero A, Ashaolu JF, Abe A, Boyede GO. Dental caries and oral health: an ignored health barrier to learning in Nigerian slums: a cross sectional survey. 2022;7(13). [CrossRef]

- Teshome A, Muche A, Girma B. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors in East Africa, 2000–2020: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2021;9:645091. [CrossRef]

- Onyejaka NK, Olatosi OO, Ndukwe NA, Amobi EO, Okoye LO, Nwamba NP. Prevalence and associated factors of dental caries among primary school children in South-East Nigeria. 2021;24(9):1300–6. [CrossRef]

- Radebe M, Singh S. Investigating dental caries rates amongst sentenced prisoners in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. 2020;75(3):137–41. [CrossRef]

- Kitsaras G, Goodwin M, Kelly MP, Pretty IA. Bedtime oral hygiene behaviours, dietary habits and children’s dental health. 2021;8(5):416. [CrossRef]

- Molete, M. Children’s oral health in South Africa: Time for action. 2018;12(4):133. [CrossRef]

- Chikte U, Pontes CC, Karangwa I, Kimmie-Dhansay F, Erasmus R, Kengne AP, et al. Dental caries in a South African adult population: findings from the Cape Town Vascular and Metabolic Health Study. 2020;70(3):176–82. [CrossRef]

- Karamehmedovic E, Petersen PE, Agdal ML, Virtanen JI. Improving oral health of children in four Balkan countries: A qualitative study among health professionals. 2023;3:1068384. [CrossRef]

- Sajid M, Javeed M, Jamil M, Munawar M, Kouser R. Assessment of oral health status and oral health education programmed in community living in rural area of Jahangirabaad of Multan. 2020;1(2). [CrossRef]

- Akera P, Kennedy SE, Lingam R, Obwolo MJ, Schutte AE, Richmond R. Effectiveness of primary school-based interventions in improving oral health of children in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022;22(1):264. [CrossRef]

- Tsai E, Walker B, Wu SC. Can oral cancer screening reduce late-stage diagnosis, treatment delay and mortality? A population-based study in Taiwan. 2024;14(12):e086588. [CrossRef]

- Wen P, Chen MX, Zhong YJ, Dong QQ, Wong HM. Global burden and inequality of dental caries, 1990 to 2019. 2022;101(4):392–9. [CrossRef]

- Qin X, Zi H, Zeng X. Changes in the global burden of untreated dental caries from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. 2022;8(9). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. alternative to the pharmacological approach. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacological Research, 166, 105511. [CrossRef]

- Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, et al. Screening and interventions to prevent dental caries in children younger than 5 years: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. 2021;326(21):2172–8. [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam LF, Vettore MV, Bayani A, Bayat AH, Ahounbar E, Hemmat M, et al. The Association of Oral Health Status, demographic characteristics and socioeconomic determinants with Oral health-related quality of life among children: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. 2020;20(1):489. [CrossRef]

- Babaei M, Freeland-Graves J, Sachdev PK, Wright GJ. Influence of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of added sugars consumption on periodontal status in low-income women. 2022;46(1):219. [CrossRef]

- Bhayat A, Madiba TK, Nkambule NR. A three-year audit of dental services at primary health care facilities in gauteng, south africa: 2017 to 2019. 2020;10(4):452–7. [CrossRef]

- Molete M, Stewart A, Bosire E, Igumbor J. The policy implementation gap of school oral health programmes in Tshwane, South Africa: a qualitative case study. 2020;20:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Petersen PE, Baez RJ, Ogawa H. Global application of oral disease prevention and health promotion as measured 10 years after the 2007 World Health Assembly statement on oral health. 2020;48(4):338–48. [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari E, Gray-Burrows KA, Vinall-Collier KA, Edwebi S, Marshman Z, McEachan RR, et al. Home-based toothbrushing interventions for parents of young children to reduce dental caries: A systematic review. 2021;31(1):37–79. [CrossRef]

- Shitie A, Addis R, Tilahun A, Negash W. Prevalence of dental caries and its associated factors among primary school children in Ethiopia. 2021;2021(1):6637196. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Chen W, Lin L, Ma H, Huang F. The prevalence of dental caries and its associated factors among preschool children in Huizhou, China: a cross-sectional study. 2024;5:1461959. [CrossRef]

- Salama F, Alwohaibi A, Alabdullatif A, Alnasser A, Hafiz Z. Knowledge, behaviours and beliefs of parents regarding the oral health of their children. 2020;21(2):103–9. [CrossRef]

- Ellakany P, Madi M, Fouda SM, Ibrahim M, AlHumaid J. The effect of parental education and socioeconomic status on dental caries among Saudi children. 2021;18(22):11862. [CrossRef]

- Deinzer R, Shankar-Subramanian S, Ritsert A, Ebel S, Wöstmann B, Margraf-Stiksrud J, et al. Good role models? Tooth brushing capabilities of parents: a video observation study. 2021;21:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Berzinski M, Morawska A, Mitchell AE, Baker S. Parenting and child behaviour as predictors of toothbrushing difficulties in young children. 2020;30(1):75–84. [CrossRef]

- Gurav KM, Shetty V, Vinay V, Bhor K, Jain C, Divekar P. Effectiveness of oral health educational methods among school children aged 5–16 years in improving their oral health status: a meta-analysis. 2022;15(3):338. [CrossRef]

- Ngatemi PT, Kasihani NN. Independence of Brushing Teeth to Free-Plaque Score in Preschool Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. 2021;15(3):3722–7. [CrossRef]

- Soldo M, Matijević J, Malčić Ivanišević A, Čuković-Bagić I, Marks L, Nikolov Borić D, et al. Impact of oral hygiene instructions on plaque index in adolescents. 2020;28(2):103–7. [CrossRef]

- Watt, RG. Oral health inequalities—Developments in research, policy and practice over the last 50 years. 2023;51(4):595–9. [CrossRef]

- Bala R, Sargaiyan V, Rathi SA, Mankar SS, Jaiswal AK, Mankar SA. Mobile dental clinic for oral health services to underserved rural Indian communities. 2023;19(13):1383.

- Ghanbarzadegan A, Balasubramanian M, Luzzi L, Brennan D, Bastani P. Inequality in dental services: a scoping review on the role of access toward achieving universal health coverage in oral health. 2021;21(1):404. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarzadegan A, Mittinty M, Brennan DS, Jamieson LM. The effect of education on dental service utilization patterns in different sectors: A multiple mediation analysis. 2023;51(6):1093–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).