Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

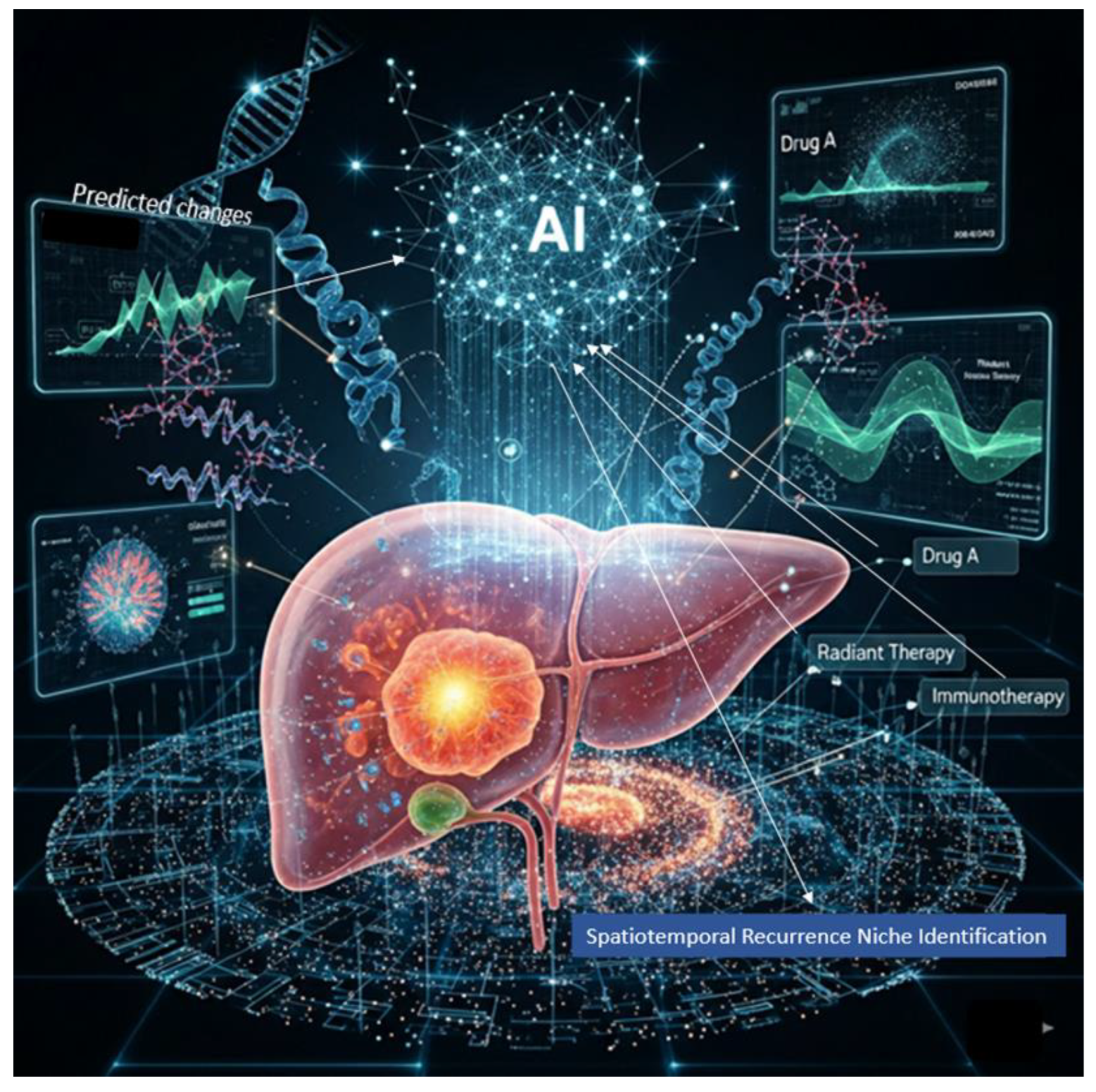

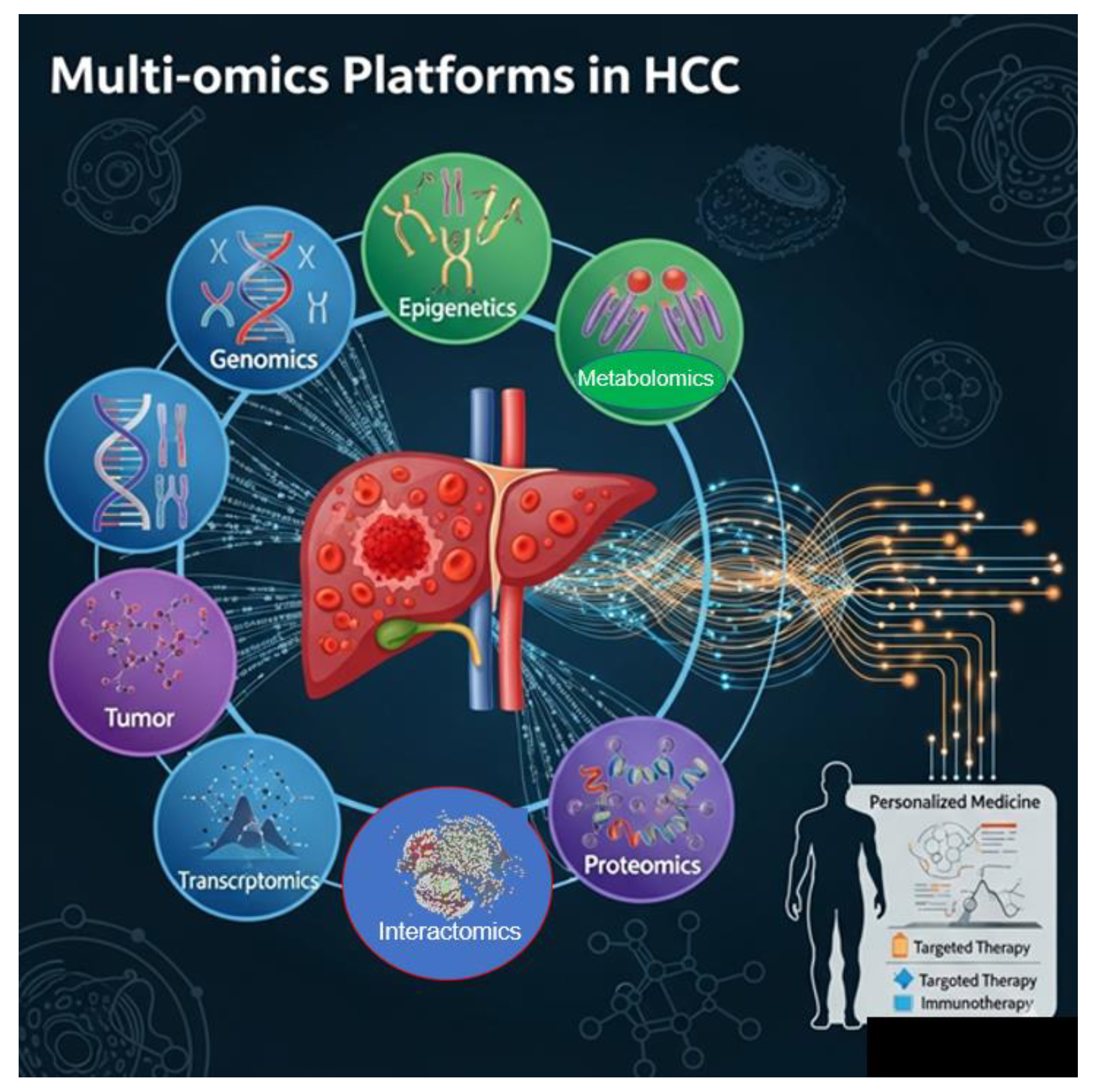

This review examines the transformative potential of dynamic genomics and systems biology in modern healthcare, focusing on their roles in precision oncology for liver cancer (Hepatocellular Carcinoma, HCC). It provides an integrated overview of how multi-omics technologies combine to help understand the complex biological landscape of tumors, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, interactomics, metabolomics, and spatial transcriptomics. These advancements enable detailed patient stratification based on molecular, spatial, and functional tumor features, supporting personalized treatment strategies. The review emphasizes the significance of regulatory networks and cell-specific pathways in influencing tumor behavior and immune interactions. By mapping these networks with multi-omics data, clinicians can expect resistance mechanisms, identify the best therapeutic targets, and customize interventions. The approach shifts from traditional one-size-fits-all methods to dynamic, adaptable treatment plans guided by real-time monitoring, including liquid biopsies and wearable biosensors. A practical case study illustrates how a patient with HCC benefits from a personalized therapy plan involving epigenetic therapy, checkpoint inhibitors, and continuous multi-omics monitoring. This highlights the move toward healthcare that anticipates problems, considers the entire body, and adapts quickly to changes in a tumor. Looking ahead, the review discusses innovations such as cloud-based genomic ecosystems, federated learning for data privacy, and AI-driven interpretations that analyze complex multi-layered data. These advancements aim to improve decision-making, enhance clinical results, and change the disease management model, from reactive to predictive and preventative. The review also covers some important ongoing or completed clinical trials targeting HCC that use advanced molecular and immunological techniques. Overall, the review advocates adopting a systems-level, technological, and spatial approach to cancer treatment, stressing the importance of integrating data-driven insights into clinical workflows to advance personalized medicine.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.1. Information dictates which genes activate or deactivate in response to environmental stimuli, regulating biological processes. Proteins represent the dynamic aspect, which is vital for maintaining homeostasis and regulating gene expression [4].

- 1.2. Molecular Interaction - Biological functions result from the combined activity of multiple biomolecules, rather than from a single molecule. Physical interactions between biomolecules, which are sequences of elementary acts, or “bits” of communication, allow data to be exchanged through sequential molecular processes and can be viewed as elementary information events.

- 1.3. Functional Modules - A complex interactive network transmits the functional information, which comes from elementary actions, through digital communication, processes it, and generates specific biological functions, which is the processing product [5]. Relational activity creates emergent properties that characterize specific informational and functional modules (or subgraphs) within a biological system [6]. Therefore, biological function arises from the joint processing of information via elementary events, which can be both long-lasting (e.g., protein complexes) and momentary.

- 1.4. Interactive networks - Elementary interactions between molecules form complex networks that process information, generating particular biological functions.

- 1.5. Cellular Interaction - Cells communicate through chemical signals, which are forms of information that regulate cellular functions. This communication through signaling pathways, transmits information through molecules like hormones, neurotransmitters, and cytokines. These signaling events coordinate activities among cells and tissues, ensuring appropriate responses to environmental changes or developmental signals. Cellular and metabolic relationships are interconnected, enabling informed decisions at the tissue or organ level [7].

- 1.6. Complex systems - Interactions among proteins, genes, and metabolites form complex networks (interaction networks or graphs) that are essential for organism functioning through information distribution. Biological complexity emerges from combining information at different levels (molecular, cellular, ecological), leading to new properties [8].

- 1.7. Biotechnology and research - Understanding biological information facilitates genetic engineering and developing innovative therapies. Analyzing biological informational data is crucial for medical and environmental research [9].

2. The Role of DNA

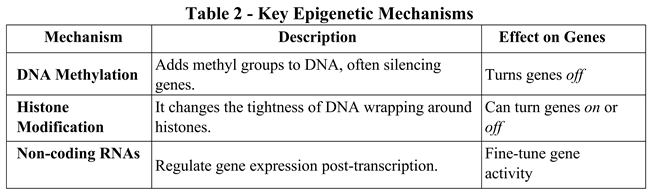

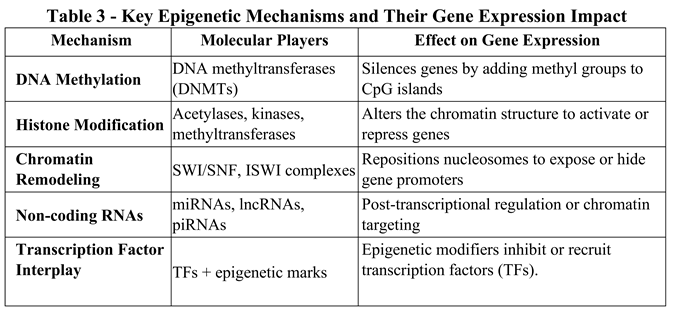

2.1. What Do They Mean?

2.2. The Core Mechanisms That Drive Gene Expression

2.3. Regulatory Mechanisms

2.4. Additional Gene Expression Mechanisms

2.5. The RNA Editing

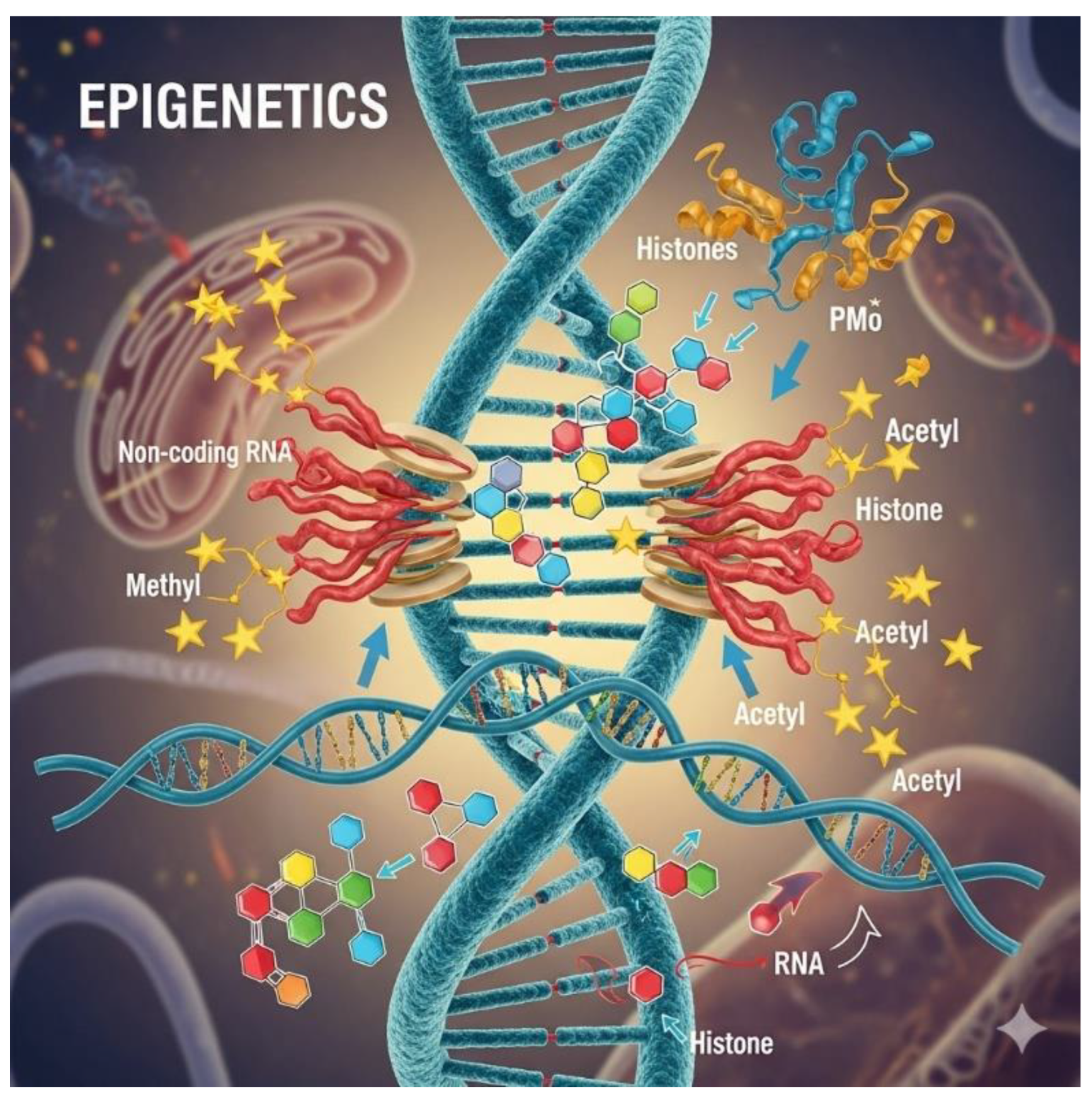

3. Epigenetic Effects and “The Why”

3.1. Real-Life Examples

- Cell differentiation: All cells share the same DNA, but epigenetics determines whether a cell becomes a neuron, a muscle cell, or a skin cell [62].

- Environmental influences: Exposure to pollution or poor nutrition can increase DNA methylation, potentially silencing protective genes [63].

- Mental health: Stress and trauma can change epigenetic markers, impacting genes related to mood and cognition [64].

3.2. A Closer Look at Dynamic Relationships

3.3. Environmental and Developmental Influences on the Epigenome

3.4. Epigenetic Mechanisms Driving Aging

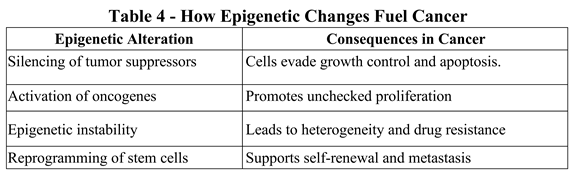

3.5. Key Epigenetic Mechanisms Driving Cancer

4. Therapeutic Implications

4.1. Case Study: Epigenetics in Colorectal Cancer

5. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Cancer Detection

- sEPT9 DNA methylation, used in blood tests to detect early-stage colorectal cancer [126].

- gSTP1 hypermethylation in prostate cancer helps distinguish malignant from benign tumors [127].

- miRNA signatures: Unique patterns of microRNAs in the blood can indicate breast, lung, or pancreatic cancer [128].

5.1. The Future: Precision Epigenomics

6. From Epigenetics to Proteins: The Molecular Cascade.

6.1. Real-World Implications in Molecular Processes

6.2. When Epigenetics and Proteomics Collide

7. The Near Future: Digital Twins And Virtual Trials

7.1. Digital Twins

7.1.1. How Does the Virtual Digital Twin System in Healthcare Work?

7.1.2. Development, Discovery, and Planning Activities

7.1.3. Future Challenges and Considerations

- Privacy and Data Security: Ensuring the secure handling of large amounts of sensitive patient data is a significant concern [156].

- Integration: Integrating digital twin platforms with existing healthcare systems and workflows is complex [157].

- Cost: The initial investment in technology, infrastructure, and data management can be substantial [158].

- Technical complexity: developing accurate, reliable, scalable digital twin models requires advanced technical expertise [159].

- Regulation: Establishing an appropriate regulatory framework for digital twin technologies is challenging [160].

7.2. Virtual Trials

7.2.1. How Do Virtual Clinical Trials Work?

7.2.2. Benefits of Virtual Clinical Trials

- Greater patient access and diversity: By removing the need to travel to clinical sites, virtual trials allow patients in rural areas or with mobility challenges to take part, broadening the participant pool and enhancing diversity [165].

- Enhanced convenience and engagement: Participants can complete study activities at home, saving time and minimizing disruption to daily routines [165].

- Cost and time savings: Virtual models can cut overhead costs associated with traditional sites and speed up recruitment and study timelines [167].

- Continuous data collection: Real-time information from wearable devices offers researchers more detailed and frequent insights into participant health and study results [168].

7.2.3. Challenges of Virtual Clinical Trials

7.2.4. The future of Virtual Clinical Trials

- Hybrid models: Many trials now combine virtual components with traditional onsite visits to capitalize on the advantages of both approaches [170].

- Increased adoption: The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the widespread adoption and standardization of virtual trial models in the life sciences sector [170].

- Transformative shift: Virtual clinical trials mark a significant change toward more patient-centered, accessible, and efficient research [171].

8. The “Who”, Cellular and Tissue Specificity

9. Precision Oncology Reimagined

9.1. The Key Trends Already Shaping The Future Are:

9.2. Regulatory Networks: The Logic of Cellular Decision-Making

10. Systems Biology: The Whole Is Greater Than the Sum

- Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics

- Spatial data and temporal dynamics

- Environmental and therapeutic inputs

- Predict therapy response pathways

- Identify compensatory pathways that influence resistance

- Design combination therapies tailored to system-level vulnerabilities

10.1. The Which”: Patient Stratification Through Network Insight

10.2. Dynamic Decision Tree: Network-Informed Stratification in HCC

10.3. Tumor Molecular Profile: Root Node

- -

- If the Wnt pathway is active, → Consider Wnt inhibitors; immunotherapy is likely ineffective [219].

- -

- If TGFβ signaling is dominant, → Add TGFβ blockade to restore immune infiltration [220].

- -

- If the interferon response is suppressed → Evaluate viral etiology (HBV/HCV) and consider TCRT cell therapy [221].

- If the immune interactome is disrupted (e.g., low CD8–MHC-I interaction) → predict immune escape [223]; consider priming strategies.

- If the angiogenic interactome is active (e.g., VEGF hub centrality) → add antiangiogenic agents [224].

- If the fibrotic interactome is dense → consider stromal remodeling agents (e.g., FAP-targeted therapies) [225.

- If we predict adaptive resistance → Preemptively adjust drug combinations [226].

- If we forecast immune cell exhaustion → Add IL-2 agonists or checkpoint boosters [227].

- If we detect metabolic reprogramming → Tailor diet or add metabolic inhibitors [228].

- Anti-PD-1 + TGF-β inhibitor for immune-excluded tumors [229].

- Wnt inhibitor + metabolic modulator for CTNNB1-mutant HCC [230].

- TCR-T cell therapy + antiviral for HBV-HCC with high viral antigen load [231].

11. A Case Study of a Middle-Aged Patient with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

- We observe hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes such as CDKN2A and RASSF1A, indicating aggressive tumor behavior [242].

- Histone modification patterns show a loss of H3K27me3, suggesting active oncogene expression [243].

- Non-coding RNA signatures reveal elevated levels of miR-21, suppressing apoptosis and promoting cell proliferation [244].

- Overexpression of AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) and GPC3 (glypican-3) confirms hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [245].

- Increased levels of VEGF and PD-L1 suggest processes related to angiogenesis and immune evasion [246].

- Unique protein signatures indicate pathways involved in drug resistance.

- Tracking epigenetic changes helps identify recurrence early [248].

- Proteomic alterations inform drug dosing and combination strategies. This approach transforms patient care from reactive to proactive and precise, enhancing survival rates and quality of life.

11.1. Cell and Tissue Specificity in Liver Cancer

-

Malignant Hepatocytes

- They are the primary tumor cells in HCC.

- They display altered gene expression patterns, often driven by mutations and epigenetic changes.

- In HBV-related HCC, viral integration into hepatocyte DNA can activate oncogenes [250].

- Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs)

- 3.

- T Cells and B Cells

- 4.

- Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs)

- 5.

- Endothelial Cells

11.2. The Importance of Tissue Specificity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

- Cell-Type Composition

- 2.

- Spatial Organization

- 3.

- Gene Expression Profiles

- 4.

- Microenvironment Dynamics

11.4. Clinical Relevance in Liver Cancer.

11.5. Spatial Transcriptomics in Liver Cancer

- Reveals distinct cellular neighborhoods: tumor clusters, immune niches, and stromal zones.

- Identifies PROM1+ and CD47+ cancer stem cell niches linked to metastasis and immune evasion [259].

- Maps tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) and their proximity to tumor cells, influencing immune infiltration and therapy response.

- Detects spatial gradients of gene expression from non-tumor to tumor regions, illustrating how the tumor capsule affects transcriptome diversity.

11.6. Multi-Omics in Clinical Trials

- Predictive biomarkers: multi-omics helps identify which patients will respond to checkpoint inhibitors or TCR-mediated T-cell therapy.

- Cellular immunotherapy: Clinical trials evaluate engineered T cells, DC vaccines, and macrophage modulation based on the patient’s immune profile.

11.7. The Future: AI-Driven Precision Oncology.

11.8. Multi-Omics Platforms in HCC

11.9. Tailored Solutions Are Only One Element of the Total Scope

12. Advanced International Trials on HCC

References

- Tkačik, G., & Bialek, W. (2016). Information processing in living systems. Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics, 7(1), 89-117.

- Godfrey-Smith, P. (2007). Information in biology. The Cambridge Guide to the Philosophy of Biology, ed. David L. Hull and Michael Ruse, 103-119.

- Portin, P., & Wilkins, A. (2017). The evolving definition of the term “gene”. Genetics, 205(4), 1353-1364.

- Rué, P., & Martinez Arias, A. (2015). Cell dynamics and gene expression control in tissue homeostasis and development. Molecular systems biology, 11(2), 792.

- Cevallos, Y., Molina, L., Santillán, A., De Rango, F., Rushdi, A., & Alonso, J. B. (2017). A digital communication analysis of gene expression of proteins in biological systems: A layered network model view. Cognitive Computation, 9(1), 43-67.

- Emmert-Streib, F., & Dehmer, M. (2011). Networks for systems biology: conceptual connection of data and function. IET systems biology, 5(3), 185-207.

- Su, J., Song, Y., Zhu, Z., Huang, X., Fan, J., Qiao, J., & Mao, F. (2024). Cell–cell communication: new insights and clinical implications. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 9(1), 196.

- Wolf, Y. I., Katsnelson, M. I., & Koonin, E. V. (2018). Physical foundations of biological complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), E8678-E8687.

- Iyengar, G. V. (2024). Elemental Analysis of Biological Systems: Biological, Medical, Environmental, Compositional, and Methodological Aspects, Volume I. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group). [CrossRef]

- Gaiseanu, F. (2021). Evolution and development of the information concept in biological systems: From empirical description to informational modeling of the living structures. Philosophy Study, 11(7), 501-516.

- Kellis, M., Wold, B., Snyder, M. P., Bernstein, B. E., Kundaje, A., Marinov, G. K., ... & Hardison, R. C. (2014). Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(17), 6131-6138.

- Heng, H. H., Liu, G., Stevens, J. B., Bremer, S. W., Ye, K. J., Abdallah, B. Y., ... & Ye, C. J. (2011). Decoding the genome beyond sequencing: the new phase of genomic research. Genomics, 98(4), 242-252.

- Segal, E., Shapira, M., Regev, A., Pe'er, D., Botstein, D., Koller, D., & Friedman, N. (2003). Module networks: identifying regulatory modules and their condition-specific regulators from gene expression data. Nature genetics, 34(2), 166-176.

- Turner, B. M. (2009). Epigenetic responses to environmental change and their evolutionary implications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1534), 3403-3418.

- Buccitelli, C., & Selbach, M. (2020). mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21(10), 630-644.

- Shen-Orr, S. S., Tibshirani, R., Khatri, P., Bodian, D. L., Staedtler, F., Perry, N. M., ... & Butte, A. J. (2010). Cell type–specific gene expression differences in complex tissues. Nature methods, 7(4), 287-289.

- Kolodziejczyk, A. A., Kim, J. K., Svensson, V., Marioni, J. C., & Teichmann, S. A. (2015). The technology and biology of single-cell RNA sequencing. Molecular cell, 58(4), 610-620.

- Barrett, L. W., Fletcher, S., & Wilton, S. D. (2012). Regulation of eukaryotic gene expression by the untranslated gene regions and other non-coding elements. Cellular and molecular life sciences, 69(21), 3613-3634.

- Ma’ayan, A. (2011). Introduction to network analysis in systems biology. Science signaling, 4(190), tr5-tr5.

- Stuart, T., & Satija, R. (2019). Integrative single-cell analysis. Nature reviews genetics, 20(5), 257-272.

- Buratowski, S. (1994). The basics of basal transcription by RNA polymerase II. Cell, 77(1), 1-3.

- Henras, A. K., Plisson-Chastang, C., O'Donohue, M. F., Chakraborty, A., & Gleizes, P. E. (2015). An overview of pre-ribosomal RNA processing in eukaryotes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA, 6(2), 225-242.

- Celotto, A. M., & Graveley, B. R. (2001). Alternative splicing of the Drosophila Dscam pre-mRNA is both temporally and spatially regulated. Genetics, 159(2), 599-608.

- Meyuhas, O., Avni, D., & Shama, S. (1996). Translational control of ribosomal protein mRNAs in eukaryotes. Cold spring harbor monograph series, 30, 363-388.

- Ramazi, S., & Zahiri, J. (2021). Post-translational modifications in proteins: resources, tools and prediction methods. Database, 2021, baab012.

- Steiner, D. F., Park, S. Y., Støy, J., Philipson, L. H., & Bell, G. I. (2009). A brief perspective on insulin production. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 11, 189-196.

- Vaissière, T., Sawan, C., & Herceg, Z. (2008). Epigenetic interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 659(1-2), 40-48.

- Baylin, S. B. (2005). DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer. Nature clinical practice Oncology, 2(Suppl 1), S4-S11.

- Belotserkovskii, B. P., Mirkin, S. M., & Hanawalt, P. C. (2013). DNA sequences that interfere with transcription: implications for genome function and stability. Chemical reviews, 113(11), 8620-8637.

- Liang, S., Moghimi, B., Yang, T. P., Strouboulis, J., & Bungert, J. (2008). Locus control region mediated regulation of adult β-globin gene expression. Journal of cellular biochemistry, 105(1), 9-16.

- Chitwood, D. H., & Timmermans, M. C. (2010). Small RNAs are on the move. Nature, 467(7314), 415-419.

- Buscaglia, L. E. B., & Li, Y. (2011). Apoptosis and the target genes of microRNA-21. Chinese journal of cancer, 30(6), 371.

- Mary Brittoa, S., Jayarajanb, D. (2023). Unravelling the Molecular Symphony: Investigating Gene Expression at the Biochemical Level. Eur. Chem. Bull. 2023,12(Special Issue 8),2799-2810. ISSN 2063-5346.

- Clapier, C. R., & Cairns, B. R. (2009). The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annual review of biochemistry, 78(1), 273-304.

- Roberts, C. W., & Orkin, S. H. (2004). The SWI/SNF complex, chromatin and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 4(2), 133-142.

- Chen, K., Zhao, B. S., & He, C. (2016). Nucleic acid modifications in regulation of gene expression. Cell chemical biology, 23(1), 74-85.

- Youness, A., Miquel, C. H., & Guéry, J. C. (2021). Escape from X chromosome inactivation and the female predominance in autoimmune diseases. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(3), 1114.

- Zhao, P., & Malik, S. (2022). The phosphorylation to acetylation/methylation cascade in transcriptional regulation: how kinases regulate transcriptional activities of DNA/histone-modifying enzymes. Cell & Bioscience, 12(1), 83.

- Buccitelli, C., & Selbach, M. (2020). mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21(10), 630-644.

- Breaker, R. R. (2018). Riboswitches and translation control. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 10(11), a032797.

- Kadauke, S., & Blobel, G. A. (2009). Chromatin loops in gene regulation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1789(1), 17-25.

- Ak, P., & Levine, A. J. (2010). p53 and NF-κB: different strategies for responding to stress lead to a functional antagonism. The FASEB Journal, 24(10), 3643-3652.

- Lu, N., & Malemud, C. J. (2019). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase: a regulator of cell growth, inflammation, chondrocyte and bone cell receptor-mediated gene expression. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(15), 3792.

- Cowan, K. J., & Storey, K. B. (2003). Mitogen-activated protein kinases: new signaling pathways functioning in cellular responses to environmental stress. Journal of Experimental Biology, 206(7), 1107-1115.

- Sanchez-Diaz, P., & Penalva, L. O. (2006). Post-transcription meets post-genomic: the saga of RNA binding proteins in a new era. RNA biology, 3(3), 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Okada, S., & Sakurai, M. (2021). Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in neurological development and disease. RNA biology, 18(7), 999-1013.

- Rees, H. A., & Liu, D. R. (2018). Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nature reviews genetics, 19(12), 770-788.

- Ontiveros, R. J., Stoute, J., & Liu, K. F. (2019). The chemical diversity of RNA modifications. Biochemical Journal, 476(8), 1227-1245.

- Zhang, D., Zhu, L., Gao, Y., Wang, Y., & Li, P. (2024). RNA editing enzymes: structure, biological functions and applications. Cell & Bioscience, 14(1), 34. [CrossRef]

- Picardi, E., Manzari, C., Mastropasqua, F., Aiello, I., D’Erchia, A. M., & Pesole, G. (2015). Profiling RNA editing in human tissues: towards the inosinome Atlas. Scientific reports, 5(1), 14941.

- Kung, C. P., Maggi Jr, L. B., & Weber, J. D. (2018). The role of RNA editing in cancer development and metabolic disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 9, 762.

- Doudna, J. A. (2020). The promise and challenge of therapeutic genome editing. Nature, 578(7794), 229-236.

- Cox, D. B., Gootenberg, J. S., Abudayyeh, O. O., Franklin, B., Kellner, M. J., Joung, J., & Zhang, F. (2017). RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science, 358(6366), 1019-1027.

- Eisenberg, E. (2020). Proteome diversification by RNA editing. RNA Editing: Methods and Protocols, 229-251.

- Hwang, T., Park, C. K., Leung, A. K., Gao, Y., Hyde, T. M., Kleinman, J. E., ... & Weinberger, D. R. (2016). Dynamic regulation of RNA editing in human brain development and disease. Nature neuroscience, 19(8), 1093-1099.

- Reik, W. (2007). Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development. Nature, 447(7143), 425-432.

- Jaenisch, R., & Bird, A. (2003). Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nature genetics, 33(3), 245-254.

- Carlberg, C., & Molnár, F. (2016). Mechanisms of gene regulation (pp. 57-73). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Abdul, Q. A., Yu, B. P., Chung, H. Y., Jung, H. A., & Choi, J. S. (2017). Epigenetic modifications of gene expression by lifestyle and environment. Archives of pharmacal research, 40(11), 1219-1237. [CrossRef]

- Boyko, A., & Kovalchuk, I. (2011). Genome instability and epigenetic modification, heritable responses to environmental stress?. Current opinion in plant biology, 14(3), 260-266.

- Heine, S. J. (2017). DNA is not destiny: The remarkable, completely misunderstood relationship between you and your genes. WW Norton & Company.

- Huang, B., Jiang, C., & Zhang, R. (2014). Epigenetics: the language of the cell?. Epigenomics, 6(1), 73-88.

- Li, S., Chen, M., Li, Y., & Tollefsbol, T. O. (2019). Prenatal epigenetics diets play protective roles against environmental pollution. Clinical epigenetics, 11(1), 82. [CrossRef]

- Argentieri, M. A., Nagarajan, S., Seddighzadeh, B., Baccarelli, A. A., & Shields, A. E. (2017). Epigenetic pathways in human disease: the impact of DNA methylation on stress-related pathogenesis and current challenges in biomarker development. EBioMedicine, 18, 327-350. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K., & Fournier, D. (2017). Histone code and higher-order chromatin folding: a hypothesis. Genomics and computational biology, 3(2), e41.

- Guillemette, B., Drogaris, P., Lin, H. H. S., Armstrong, H., Hiragami-Hamada, K., Imhof, A., ... & Festenstein, R. J. (2011). H3 lysine 4 is acetylated at active gene promoters and is regulated by H3 lysine 4 methylation. PLoS genetics, 7(3), e1001354. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y., Morgunova, E., Jolma, A., Kaasinen, E., Sahu, B., Khund-Sayeed, S., ... & Taipale, J. (2017). Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science, 356(6337), eaaj2239.

- Tirado-Magallanes, R., Rebbani, K., Lim, R., Pradhan, S., & Benoukraf, T. (2016). Whole genome DNA methylation: beyond genes silencing. Oncotarget, 8(3), 5629.

- Auerkari, E. I. (2006). Methylation of tumor suppressor genes p16 (INK4a), p27 (Kip1) and E-cadherin in carcinogenesis. Oral oncology, 42(1), 4-12. [CrossRef]

- Clapier, C. R., & Cairns, B. R. (2009). The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annual review of biochemistry, 78(1), 273-304.

- Loda, A., & Heard, E. (2019). Xist RNA in action: Past, present, and future. PLoS genetics, 15(9), e1008333.

- Dalmay, T. (2013). Mechanism of miRNA-mediated repression of mRNA translation. Essays in biochemistry, 54, 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Kan, R. L., Chen, J., & Sallam, T. (2022). Crosstalk between epitranscriptomic and epigenetic mechanisms in gene regulation. Trends in Genetics, 38(2), 182-193.

- Tiffon, C. (2018). The impact of nutrition and environmental epigenetics on human health and disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(11), 3425.

- Tiffon, C. (2018). The impact of nutrition and environmental epigenetics on human health and disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 19(11), 3425. [CrossRef]

- Reul, J. M. (2014). Making memories of stressful events: a journey along epigenetic, gene transcription, and signaling pathways. Frontiers in psychiatry, 5, 5.

- Bommarito, P. A., Martin, E., & Fry, R. C. (2017). Effects of prenatal exposure to endocrine disruptors and toxic metals on the fetal epigenome. Epigenomics, 9(3), 333-350.

- Booth, L. N., & Brunet, A. (2016). The aging epigenome. Molecular cell, 62(5), 728-744.

- Skinner, M. K. (2011). Environmental epigenetic transgenerational inheritance and somatic epigenetic mitotic stability. Epigenetics, 6(7), 838. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Salas, P., Cox, S. E., Prentice, A. M., Hennig, B. J., & Moore, S. E. (2012). Maternal nutritional status, C1 metabolism and offspring DNA methylation: a review of current evidence in human subjects. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 71(1), 154-165.

- Schneider, R., & Grosschedl, R. (2007). Dynamics and interplay of nuclear architecture, genome organization, and gene expression. Genes & development, 21(23), 3027-3043.

- Li, X., Liu, C., Lei, Z., Chen, H., & Wang, L. (2024). Phase-separated chromatin compartments: Orchestrating gene expression through condensation. Cell insight, 3(6), 100213.

- Ashwin, S. S., Maeshima, K., & Sasai, M. (2020). Heterogeneous fluid-like movements of chromatin and their implications to transcription. Biophysical Reviews, 12(2), 461-468. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Li, Z., Wu, Z., & Lu, H. (2023). Phase separation in gene transcription control: Phase separation in gene transcription control. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica, 55(7), 1052.

- Hu, Y., Shen, F., Yang, X., Han, T., Long, Z., Wen, J., ... & Guo, Q. (2023). Single-cell sequencing technology applied to epigenetics for the study of tumor heterogeneity. Clinical Epigenetics, 15(1), 161.

- Kamies, R., & Martinez-Jimenez, C. P. (2020). Advances of single-cell genomics and epigenomics in human disease: where are we now?. Mammalian Genome, 31(5), 170-180.

- Wang, K., Liu, H., Hu, Q. et al. Epigenetic regulation of aging: implications for interventions of aging and diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 374 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bertucci-Richter, E.M., Parrott, B.B. The rate of epigenetic drift scales with maximum lifespan across mammals. Nat Commun 14, 7731 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo S. Epigenetic alterations in aging. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2010 Aug;109(2):586-97. Epub 2010 May 6. PMID: 20448029; PMCID: PMC2928596. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Tian, X., Luo, J. et al. Molecular mechanisms of aging and anti-aging strategies. Cell Commun Signal 22, 285 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Pinel, C., Green, S., & Svendsen, M. N. (2023). Slowing down decay: biological clocks in personalized medicine. Frontiers in Sociology, 8, 1111071. [CrossRef]

- Szyf, M. (2012). The early-life social environment and DNA methylation. Clinical genetics, 81(4), 341-349.

- Di Giorgio, E., Paluvai, H., Dalla, E., Ranzino, L., Renzini, A., Moresi, V., ... & Brancolini, C. (2021). HDAC4 degradation during senescence unleashes an epigenetic program driven by AP-1/p300 at selected enhancers and super-enhancers. Genome Biology, 22(1), 129. [CrossRef]

- Reifsnyder, P. C., Flurkey, K., Doty, R., Calcutt, N. A., Koza, R. A., & Harrison, D. E. (2022). Rapamycin/metformin co-treatment normalizes insulin sensitivity and reduces complications of metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetic mice. Aging Cell, 21(9), e13666.

- Nir Eynon, Macsue Jacques, Kirsten Seale et al. DNA Methylation Ageing Atlas Across 17 Human Tissues, 07 August 2025, PREPRINT (Version 1, Under Review at Nature Portfolio) available at Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Dandoti, S. (2021). Mechanisms adopted by cancer cells to escape apoptosis–A review. Biocell, 45(4), 863.

- von Manstein, V., Min Yang, C., Richter, D., Delis, N., Vafaizadeh, V., & Groner, B. (2013). Resistance of cancer cells to targeted therapies through the activation of compensating signaling loops. Current signal transduction therapy, 8(3), 193-202. [CrossRef]

- Garinis, G. A., Patrinos, G. P., Spanakis, N. E., & Menounos, P. G. (2002). DNA hypermethylation: when tumour suppressor genes go silent. Human genetics, 111(2), 115-127.

- Hoffmann, M. J., & Schulz, W. A. (2005). Causes and consequences of DNA hypomethylation in human cancer. Biochemistry and cell biology, 83(3), 296-321.

- Wiles, E. T., & Selker, E. U. (2017). H3K27 methylation: a promiscuous repressive chromatin mark. Current opinion in genetics & development, 43, 31-37. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X., Wang, X., Guo, X., Ji, J., Lou, G., Zhao, J., ... & Yu, S. (2019). MicroRNA-124: an emerging therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer medicine, 8(12), 5638-5650.

- Chen, Y., Fu, L. L., Wen, X., Liu, B., Huang, J., Wang, J. H., & Wei, Y. Q. (2014). Oncogenic and tumor suppressive roles of microRNAs in apoptosis and autophagy. Apoptosis, 19(8), 1177-1189.

- Long, Y., Wang, X., Youmans, D. T., & Cech, T. R. (2017). How do lncRNAs regulate transcription?. Science advances, 3(9), eaao2110.

- Singh, A., Modak, S. B., Chaturvedi, M. M., & Purohit, J. S. (2023). SWI/SNF chromatin remodelers: structural, functional and mechanistic implications. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics, 81(2), 167-187.

- Singh, A., Modak, S. B., Chaturvedi, M. M., & Purohit, J. S. (2023). SWI/SNF chromatin remodelers: structural, functional and mechanistic implications. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics, 81(2), 167-187.

- Pathak, A., Tomar, S., & Pathak, S. (2023). Epigenetics and cancer: a comprehensive review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology, 8(1), 75-89. [CrossRef]

- You JS, Jones PA. Cancer genetics and epigenetics: two sides of the same coin? Cancer Cell. 2012 Jul 10;22(1):9-20. PMID: 22789535; PMCID: PMC3396881. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T., Yang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021). Predictive biomarkers and potential drug combinations of epi-drugs in cancer therapy. Clinical Epigenetics, 13(1), 113.

- Hong, S. N. (2018). Genetic and epigenetic alterations of colorectal cancer. Intestinal research, 16(3), 327.

- Niv, Y. (2007). Microsatellite instability and MLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal cancer. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 13(12), 1767. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W. K., Li, Y. H., Bai, X. S., & Lin, G. L. (2022). The cell cycle-associated protein CDKN2A may promotes colorectal cancer cell metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 834235.

- Chen, H. P., Zhao, Y. T., & Zhao, T. C. (2015). Histone deacetylases and mechanisms of regulation of gene expression. Critical Reviews™ in Oncogenesis, 20(1-2). [CrossRef]

- Füllgrabe, J., Kavanagh, E., & Joseph, B. (2011). Histone onco-modifications. Oncogene, 30(31), 3391-3403.

- Chrun, E. S., Modolo, F., & Daniel, F. I. (2017). Histone modifications: A review about the presence of this epigenetic phenomenon in carcinogenesis. Pathology-Research and Practice, 213(11), 1329-1339.

- Slaby, O., Svoboda, M., Fabian, P., Smerdova, T., Knoflickova, D., Bednarikova, M., ... & Vyzula, R. (2008). Altered expression of miR-21, miR-31, miR-143 and miR-145 is related to clinicopathologic features of colorectal cancer. Oncology, 72(5-6), 397-402. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gomez, A., Rodríguez-Ubreva, J., & Ballestar, E. (2018). Epigenetic interplay between immune, stromal and cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment. Clinical Immunology, 196, 64-71.

- Yang, J., Xu, J., Wang, W., Zhang, B., Yu, X., & Shi, S. (2023). Epigenetic regulation in the tumor microenvironment: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 8(1), 210. [CrossRef]

- Segditsas, S., & Tomlinson, I. (2006). Colorectal cancer and genetic alterations in the Wnt pathway. Oncogene, 25(57), 7531-7537.

- Wilting, R. H., & Dannenberg, J. H. (2012). Epigenetic mechanisms in tumorigenesis, tumor cell heterogeneity and drug resistance. Drug Resistance Updates, 15(1-2), 21-38. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Ma, T., & Yu, B. (2023). Targeting epigenetic regulators to overcome drug resistance in cancers. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 8(1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S., & Anupriya. (2019). Drugs targeting epigenetic modifications and plausible therapeutic strategies against colorectal cancer. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 10, 588. [CrossRef]

- Sahafnejad, Z., Ramazi, S., & Allahverdi, A. (2023). An update of epigenetic drugs for the treatment of cancers and brain diseases: a comprehensive review. Genes, 14(4), 873. [CrossRef]

- Zoratto, F., Rossi, L., Verrico, M., Papa, A., Basso, E., Zullo, A., ... & Tomao, S. (2014). Focus on genetic and epigenetic events of colorectal cancer pathogenesis: implications for molecular diagnosis. Tumor Biology, 35(7), 6195-6206. [CrossRef]

- Rasool, M., Malik, A., Naseer, M. I., Manan, A., Ansari, S. A., Begum, I., ... & Gan, S. H. (2015). The role of epigenetics in personalized medicine: challenges and opportunities. BMC medical genomics, 8(Suppl 1), S5. [CrossRef]

- La Thangue, N. B., & Kerr, D. J. (2011). Predictive biomarkers: a paradigm shift towards personalized cancer medicine. Nature reviews Clinical oncology, 8(10), 587-596.

- Rituraj, Pal, R. S., Wahlang, J., Pal, Y., Chaitanya, M. V. N. L., & Saxena, S. (2025). Precision oncology: transforming cancer care through personalized medicine. Medical Oncology, 42(7), 246. [CrossRef]

- Payne, S. R. (2010). From discovery to the clinic: the novel DNA methylation biomarker m SEPT9 for the detection of colorectal cancer in blood. Epigenomics, 2(4), 575-585.

- Henrique, R., & Jerónimo, C. (2004). Molecular detection of prostate cancer: a role for GSTP1 hypermethylation. European urology, 46(5), 660-669. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, N. A., Dehlendorff, C., Jensen, B. V., Bjerregaard, J. K., Nielsen, K. R., Bojesen, S. E., ... & Johansen, J. S. (2014). MicroRNA biomarkers in whole blood for detection of pancreatic cancer. Jama, 311(4), 392-404.

- Liao, C., Chen, X., & Fu, Y. (2023). Salivary analysis: An emerging paradigm for non-invasive healthcare diagnosis and monitoring. Interdisciplinary Medicine, 1(3), e20230009.

- Hamamoto, R., Komatsu, M., Takasawa, K., Asada, K., & Kaneko, S. (2019). Epigenetics analysis and integrated analysis of multiomics data, including epigenetic data, using artificial intelligence in the era of precision medicine. Biomolecules, 10(1), 62.

- Wen, X., Pu, H., Liu, Q., Guo, Z., & Luo, D. (2022). Circulating tumor DNA, a novel biomarker of tumor progression and its favorable detection techniques. Cancers, 14(24), 6025.

- Goell, J. H., & Hilton, I. B. (2021). CRISPR/Cas-based epigenome editing: advances, applications, and clinical utility. Trends in Biotechnology, 39(7), 678-691.

- Corella, D., & Ordovas, J. M. (2017). Basic concepts in molecular biology related to genetics and epigenetics. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition), 70(9), 744-753. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Hu, Y., & Wang, Z. (2024). Regulation of alternative splicing: Functional interplay with epigenetic modifications and its implication to cancer. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA, 15(1), e1815.

- Cantone, I., & Fisher, A. G. (2013). Epigenetic programming and reprogramming during development. Nature structural & molecular biology, 20(3), 282-289.

- Weng, M. K., Natarajan, K., Scholz, D., Ivanova, V. N., Sachinidis, A., Hengstler, J. G., ... & Leist, M. (2014). Lineage-specific regulation of epigenetic modifier genes in human liver and brain. PLoS One, 9(7), e102035.

- Robusti, G., Vai, A., Bonaldi, T., & Noberini, R. (2022). Investigating pathological epigenetic aberrations by epi-proteomics. Clinical Epigenetics, 14(1), 145. [CrossRef]

- Lahtz, C., & Pfeifer, G. P. (2011). Epigenetic changes of DNA repair genes in cancer. Journal of molecular cell biology, 3(1), 51-58.

- Constantin, N., Sina, A. A. I., Korbie, D., & Trau, M. (2022). Opportunities for early cancer detection: the rise of ctDNA methylation-based pan-cancer screening technologies. Epigenomes, 6(1), 6. [CrossRef]

- Myte, R., Sundkvist, A., Van Guelpen, B., & Harlid, S. (2019). Circulating levels of inflammatory markers and DNA methylation, an analysis of repeated samples from a population based cohort. Epigenetics, 14(7), 649-659.

- Suhre, K., & Zaghlool, S. (2021). Connecting the epigenome, metabolome and proteome for a deeper understanding of disease. Journal of internal medicine, 290(3), 527-548. [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. S. (2015). The developing genome: An introduction to behavioral epigenetics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992234-5.

- Aebersold, R., & Mann, M. (2016). Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature, 537(7620), 347-355.

- Noberini, R., Sigismondo, G., & Bonaldi, T. (2016). The contribution of mass spectrometry-based proteomics to understanding epigenetics. Epigenomics, 8(3), 429-445.

- Mohr, A. E., Ortega-Santos, C. P., Whisner, C. M., Klein-Seetharaman, J., & Jasbi, P. (2024). Navigating challenges and opportunities in multi-omics integration for personalized healthcare. Biomedicines, 12(7), 1496.

- Ali, H. (2023). Artificial intelligence in multi-omics data integration: Advancing precision medicine, biomarker discovery and genomic-driven disease interventions. Int J Sci Res Arch, 8(1), 1012-30.

- Mao, Y., Shangguan, D., Huang, Q., Xiao, L., Cao, D., Zhou, H., & Wang, Y. K. (2025). Emerging artificial intelligence-driven precision therapies in tumor drug resistance: recent advances, opportunities, and challenges. Molecular Cancer, 24(1), 123.

- An, G. (2022). Specialty grand challenge: What it will take to cross the valley of death: Translational systems biology,“true” precision medicine, medical digital twins, artificial intelligence and in silico clinical trials. Frontiers in Systems Biology, 2, 901159.

- Łukaniszyn, M., Majka, Ł., Grochowicz, B., Mikołajewski, D., & Kawala-Sterniuk, A. (2024). Digital twins generated by artificial intelligence in personalized healthcare. Applied Sciences, 14(20), 9404.

- Sun, T., He, X., & Li, Z. (2023). Digital twin in healthcare: Recent updates and challenges. Digital health, 9, 20552076221149651. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S. M., Ishrat, M., & Khan, W. (2025). Digital Twins in Healthcare: Revolutionizing Patient Care and Medical Operations. In Digital Twins for Smart Cities and Urban Planning (pp. 69-89). CRC Press.

- Vallée, A. (2024). Envisioning the future of personalized medicine: role and realities of digital twins. Journal of medical Internet research, 26, e50204. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., & Jiang, Z. (2024). Decision support for personalized therapy in implantable medical devices: A digital twin approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 243, 122883. [CrossRef]

- Abd Elaziz, M., Al-qaness, M. A., Dahou, A., Al-Betar, M. A., Mohamed, M. M., El-Shinawi, M., ... & Ewees, A. A. (2024). Digital twins in healthcare: Applications, technologies, simulations, and future trends. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 14(6), e1559.

- Abouelmehdi, K., Beni-Hessane, A., & Khaloufi, H. (2018). Big healthcare data: preserving security and privacy. Journal of big data, 5(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Roopa, M. S., & Venugopal, K. R. (2025). Digital Twins for Cyber-Physical Healthcare Systems: Architecture, Requirements, Systematic Analysis and Future Prospects. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Moro-Visconti, R., & Quirici, M. C. (2020). Digital technology and efficiency gains in healthcare infrastructural investments. Healthcare Research and Public Safety Journal, 2(1), 1-8.

- Jia, W., Wang, W., & Zhang, Z. (2022). From simple digital twin to complex digital twin Part I: A novel modeling method for multi-scale and multi-scenario digital twin. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 53, 101706. [CrossRef]

- Zoltick, M. M., & Maisel, J. B. (2023). Societal impacts: Legal, regulatory and ethical considerations for the digital twin. In The digital twin (pp. 1167-1200). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Rosa, C., Marsch, L. A., Winstanley, E. L., Brunner, M., & Campbell, A. N. (2021). Using digital technologies in clinical trials: current and future applications. Contemporary clinical trials, 100, 106219.

- Gomase, V. S., Ghatule, A. P., Sharma, R., Sardana, S., & Dhamane, S. P. (2025). Cloud Computing Facilitating Data Storage, Collaboration, and Analysis in Global Healthcare Clinical Trials. Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials.

- Reddy, K. J. (2025). Integrating Technology into Clinical Practice. In Innovations in Neurocognitive Rehabilitation: Harnessing Technology for Effective Therapy (pp. 329-350). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Pritchett, J. C., Patt, D., Thanarajasingam, G., Schuster, A., & Snyder, C. (2023). Patient-reported outcomes, digital health, and the quest to improve health equity. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, 43, e390678.

- Cummings, S. R. (2021). Clinical trials without clinical sites. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(5), 680-684.

- Yamada, O., Chiu, S. W., Takata, M., Abe, M., Shoji, M., Kyotani, E., ... & Yamaguchi, T. (2021). Clinical trial monitoring effectiveness: remote risk-based monitoring versus on-site monitoring with 100% source data verification. Clinical trials, 18(2), 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Arman, M. (2023). The advantages of online recruitment and selection: A systematic review of cost and time efficiency. Business Management and Strategy, 14(2), 220-240. [CrossRef]

- Azodo, I., Williams, R., Sheikh, A., & Cresswell, K. (2020). Opportunities and challenges surrounding the use of data from wearable sensor devices in health care: qualitative interview study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(10), e19542.

- Apostolaros, M., Babaian, D., Corneli, A., Forrest, A., Hamre, G., Hewett, J., ... & Randall, P. (2020). Legal, regulatory, and practical issues to consider when adopting decentralized clinical trials: recommendations from the clinical trials transformation initiative. Therapeutic innovation & regulatory science, 54(4), 779-787.

- Bhat, A., Su, W. C., Cleffi, C., & Srinivasan, S. (2021). A hybrid clinical trial delivery model in the COVID-19 era. Physical Therapy, 101(8), pzab116. [CrossRef]

- Yaakov, R. A., Güler, Ö., Mayhugh, T., & Serena, T. E. (2021). Enhancing patient centricity and advancing innovation in clinical research with virtual randomized clinical trials (vRCTs). Diagnostics, 11(2), 151.

- Arendt, D., Musser, J. M., Baker, C. V., Bergman, A., Cepko, C., Erwin, D. H., ... & Wagner, G. P. (2016). The origin and evolution of cell types. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17(12), 744-757.

- Perelis, M., Marcheva, B., Moynihan Ramsey, K., Schipma, M. J., Hutchison, A. L., Taguchi, A., ... & Bass, J. (2015). Pancreatic β cell enhancers regulate rhythmic transcription of genes controlling insulin secretion. Science, 350(6261), aac4250.

- Kouadjo, K. E., Nishida, Y., Cadrin-Girard, J. F., Yoshioka, M., & St-Amand, J. (2007). Housekeeping and tissue-specific genes in mouse tissues. BMC genomics, 8(1), 127.

- Hekselman, I., & Yeger-Lotem, E. (2020). Mechanisms of tissue and cell-type specificity in heritable traits and diseases. Nature Reviews Genetics, 21(3), 137-150.

- Gao, Y., Peng, L., & Zhao, C. (2024). MYH7 in cardiomyopathy and skeletal muscle myopathy. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 479(2), 393-417.

- Dobbelstein, M., & Moll, U. (2014). Targeting tumour-supportive cellular machineries in anticancer drug development. Nature reviews Drug discovery, 13(3), 179-196. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A., Biegert, G., Adamec, J., & Helikar, T. (2017). Identification of potential tissue-specific cancer biomarkers and development of cancer versus normal genomic classifiers. Oncotarget, 8(49), 85692. [CrossRef]

- Ståhl, P. L., Salmén, F., Vickovic, S., Lundmark, A., Navarro, J. F., Magnusson, J., ... & Frisén, J. (2016). Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science, 353(6294), 78-82.

- Cheung, P., Vallania, F., Warsinske, H. C., Donato, M., Schaffert, S., Chang, S. E., ... & Kuo, A. J. (2018). Single-cell chromatin modification profiling reveals increased epigenetic variations with aging. Cell, 173(6), 1385-1397.

- Wilbrey-Clark, A., Roberts, K., & Teichmann, S. A. (2020). Cell Atlas technologies and insights into tissue architecture. Biochemical Journal, 477(8), 1427-1442.

- Zuo, C., Zhu, J., Zou, J., & Chen, L. (2025). Unravelling tumour spatiotemporal heterogeneity using spatial multimodal data. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 15(5), e70331. [CrossRef]

- Pettini, F., Visibelli, A., Cicaloni, V., Iovinelli, D., & Spiga, O. (2021). Multi-omics model applied to cancer genetics. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(11), 5751.

- Fountzilas, E., Pearce, T., Baysal, M. A., Chakraborty, A., & Tsimberidou, A. M. (2025). Convergence of evolving artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques in precision oncology. NPJ Digital Medicine, 8(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Huss, R., Raffler, J., & Märkl, B. (2023). Artificial intelligence and digital biomarker in precision pathology guiding immune therapy selection and precision oncology. Cancer Reports, 6(7), e1796. [CrossRef]

- Gardy, J. L., & Loman, N. J. (2018). Towards a genomics-informed, real-time, global pathogen surveillance system. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(1), 9-20.

- Leung, M. K., Delong, A., Alipanahi, B., & Frey, B. J. (2015). Machine learning in genomic medicine: a review of computational problems and data sets. Proceedings of the IEEE, 104(1), 176-197.

- Heidrich, I., Deitert, B., Werner, S., & Pantel, K. (2023). Liquid biopsy for monitoring of tumor dormancy and early detection of disease recurrence in solid tumors. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 42(1), 161-182.

- Alagarswamy, K., Shi, W., Boini, A., Messaoudi, N., Grasso, V., Cattabiani, T., ... & Gumbs, A. (2024). Should AI-Powered Whole-Genome Sequencing Be Used Routinely for Personalized Decision Support in Surgical Oncology, A Scoping Review. BioMedInformatics, 4(3), 1757-1772.

- Huang, P. J., Chang, J. H., Lin, H. H., Li, Y. X., Lee, C. C., Su, C. T., ... & Tang, P. (2020). DeepVariant-on-Spark: Small-Scale Genome Analysis Using a Cloud-Based Computing Framework. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2020(1), 7231205. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T. C., Tian, T. F., & Tseng, Y. J. (2013). 3Omics: a web-based systems biology tool for analysis, integration and visualization of human transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic data. BMC systems biology, 7(1), 64.

- Langmead, B., & Nellore, A. (2018). Cloud computing for genomic data analysis and collaboration. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(4), 208-219.

- Ali, M., Naeem, F., Tariq, M., & Kaddoum, G. (2022). Federated learning for privacy preservation in smart healthcare systems: A comprehensive survey. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics, 27(2), 778-789. [CrossRef]

- Suura, S. R. (2025). Integrating Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Big Data with Genetic Testing and Genomic Medicine to Enable Earlier, Personalized Health Interventions. Deep Science Publishing.

- Schlitt, T., & Brazma, A. (2007). Current approaches to gene regulatory network modelling. BMC bioinformatics, 8(Suppl 6), S9.

- Singh, S., Gouri, V., & Samant, M. (2023). TGF-β in correlation with tumor progression, immunosuppression and targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Medical Oncology, 40(11), 335. [CrossRef]

- Gatherer, D. (2010). So what do we really mean when we say that systems biology is holistic?. BMC systems biology, 4(1), 22.

- O’Connor, T. (2020). Emergent properties. Available from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/properties-emergent/?utm_source=chatgpt.com).

- Tavassoly, I., Goldfarb, J., & Iyengar, R. (2018). Systems biology primer: the basic methods and approaches. Essays in biochemistry, 62(4), 487-500.

- Ma'ayan, A. (2017). Complex systems biology. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 14(134), 20170391.

- Panditrao, G., Bhowmick, R., Meena, C., & Sarkar, R. R. (2022). Emerging landscape of molecular interaction networks: Opportunities, challenges and prospects. Journal of Biosciences, 47(2), 24. [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, C., & Timmis, J. (2018). GVCs and centrality: Mapping key hubs, spokes and the periphery.

- Ávila, A. Á. (2023). Characterization of the anti-leukemic properties of anti-CD3 antibodies in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (Doctoral dissertation, Université Paris Cité).

- Mamun, M. A., Mannoor, K., Cao, J., Qadri, F., & Song, X. (2020). SOX2 in cancer stemness: tumor malignancy and therapeutic potentials. Journal of molecular cell biology, 12(2), 85-98. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Lee, V. H., Ng, M. K., Yan, H., & Bijlsma, M. F. (2019). Molecular subtyping of cancer: current status and moving toward clinical applications. Briefings in bioinformatics, 20(2), 572-584.

- Shen, Q., He, Y., Qian, J., & Wang, X. (2022). Identifying tumor immunity-associated molecular features in liver hepatocellular carcinoma by multi-omics analysis. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 9, 960457.

- Ljungberg, J. K., Kling, J. C., Tran, T. T., & Blumenthal, A. (2019). Functions of the WNT signaling network in shaping host responses to infection. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 2521.

- Przedborski, M., Smalley, M., Thiyagarajan, S., Goldman, A., & Kohandel, M. (2021). Systems biology informed neural networks (SBINN) predict response and novel combinations for PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Communications biology, 4(1), 877.

- Wrinch, D. (1947). The native protein. Science, 106(2743), 73-76.

- Smejkal, G. B. (2013). The meaning of ‘native’. Expert Review of Proteomics, 10(5), 407-409.

- Mastropietro, A. (2024). Toward explainable biomedical deep learning. Training and Explaining Neural Networks in Bioinformatics and Medicinal Chemistry. Doctoral Thesis in Data Science. Available at UNIROMA1: https://iris.uniroma1.it/retrieve/cc782790-8122-4446-8c9f-7bf3827ab4da/Tesi_dottorato_Mastropietro.pdf.

- Karunakaran, K. B. (2024). Interactome-based framework to translate disease genetic data into biological and clinical insights (Doctoral dissertation, University of Reading).

- Petti, M., & Farina, L. (2023). Network medicine for patients' stratification: From single-layer to multi-omics. WIREs Mechanisms of Disease, 15(6), e1623.

- Yavuz, B. R., Jang, H., & Nussinov, R. (2024). Anticancer Target Combinations: Network-Informed Signaling-Based Approach to Discovery. bioRxiv, 2024-10.

- Mukherjee, A., Abraham, S., Singh, A., Balaji, S., & Mukunthan, K. S. (2025). From data to cure: A comprehensive exploration of multi-omics data analysis for targeted therapies. Molecular biotechnology, 67(4), 1269-1289. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, S., Gaujoux, S., Launay, P., Baudry, C., Chokri, I., Ragazzon, B., ... & Tissier, F. (2011). Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation in adrenocortical adenomas is frequently due to somatic CTNNB1-activating mutations, which are associated with larger and nonsecreting tumors: a study in cortisol-secreting and-nonsecreting tumors. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(2), E419-E426.

- Assoun, S., Theou-Anton, N., Nguenang, M., Cazes, A., Danel, C., Abbar, B., ... & Zalcman, G. (2019). Association of TP53 mutations with response and longer survival under immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung cancer, 132, 65-71. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, H., Lee, E., Lopez-Darwin, S. L., & Kang, Y. (2025). Deciphering normal and cancer stem cell niches by spatial transcriptomics: opportunities and challenges. Genes & Development, 39(1-2), 64-85.

- Takeuchi, Y., Tanegashima, T., Sato, E., Irie, T., Sai, A., Itahashi, K., ... & Nishikawa, H. (2021). Highly immunogenic cancer cells require activation of the WNT pathway for immunological escape. Science immunology, 6(65), eabc6424. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., Yi, M., Jiao, Y., Chu, Q., & Wu, K. (2019). Blocking TGF-β signaling to enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor. OncoTargets and therapy, 9527-9538.

- Randall, R. E., & Goodbourn, S. (2008). Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. Journal of general virology, 89(1), 1-47.

- Chen, S., Fragoza, R., Klei, L., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Roeder, K., ... & Yu, H. (2018). An interactome perturbation framework prioritizes damaging missense mutations for developmental disorders. Nature genetics, 50(7), 1032-1040.

- Li, X., Ruan, Z., Yang, S., Yang, Q., Li, J., & Hu, M. (2024). Bioinformatic-Experimental Screening Uncovers Multiple Targets for Increase of MHC-I Expression through Activating the Interferon Response in Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(19), 10546.

- Lungu, C. N., Mangalagiu, I. I., Romila, A., Nechita, A., Putz, M. V., & Mehedinti, M. C. (2025). Molecular Mediated Angiogenesis and Vasculogenesis Networks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(13), 6316. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Liu, Q., Jing, X., Wang, Y., Jia, X., Yang, X., & Chen, K. (2025). Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Heterogeneity, Cancer Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm, 6(7), e70292.

- Ho, D. (2020). Artificial intelligence in cancer therapy. Science, 367(6481), 982-983.

- Yong, C. S., Telarovic, I., Gregor, L., Raeber, M. E., Pruschy, M., & Boyman, O. (2024). IL-2 immunotherapy rescues irradiation-induced T cell exhaustion in vivo. bioRxiv, 2024-01.

- Faubert, B., Solmonson, A., & DeBerardinis, R. J. (2020). Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science, 368(6487), eaaw5473.

- Karami, Z., Mortezaee, K., & Majidpoor, J. (2023). Dual anti-PD-(L) 1/TGF-β inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy–updated. International Immunopharmacology, 122, 110648.

- Matsumoto, S., & Kikuchi, A. (2024). Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in liver biology and tumorigenesis. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal, 60(5), 466-481. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F., Zhao, J., Tan, A. T., Hu, W., Wang, S. Y., Jin, J., ... & Wang, F. S. (2021). Immunotherapy of HBV-related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with short-term HBV-specific TCR expressed T cells: results of dose escalation, phase I trial. Hepatology international, 15(6), 1402-1412.

- Zhan, Z. H., Hong, J., Li, J. Y., Wang, C., He, L., Xu, Z., & Zhang, J. (2025). Artificial intelligence-based methods for protein structure prediction: a survey. Artificial Intelligence Review, 58(10), 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Jastrzębski, M. K. (2024). Computational Methods to Target Protein-Protein Interactions. In Protein-Protein Docking: Methods and Protocols (pp. 327-343). New York, NY: Springer US.

- Anderson, J. B., & Johnnesson, R. (2006). Understanding information transmission. John Wiley & Sons.

- Morgan, S. J., Pullon, S. R., Macdonald, L. M., McKinlay, E. M., & Gray, B. V. (2017). Case study observational research: A framework for conducting case study research where observation data are the focus. Qualitative health research, 27(7), 1060-1068. [CrossRef]

- Uher, J. (2022). Functions of units, scales and quantitative data: Fundamental differences in numerical traceability between sciences. Quality & Quantity, 56(4), 2519-2548. [CrossRef]

- Barba, L. A. (2018). Terminologies for reproducible research. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03311.

- Hepburn, B., & Andersen, H. (2015). Scientific method. Available at Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-method/?utm_source=webtekno).

- Colonna, G. (2025). Protein biophysics: current limitations and prospects. AIMS Biophysics, 12(3), 333-374.

- Sharma A, Colonna G. System-Wide Pollution of Biomedical Data: Consequence of the Search for Hub Genes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Without Spatiotemporal Consideration. Mol Diagn Ther. 2021 Jan;25(1):9-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-020-00505-3. Epub 2021 Jan 21. Erratum in: Mol Diagn Ther. 2021 May;25(3):387. PMID: 33475988; PMCID: PMC7847983. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Colonna G. Correction to: System-Wide Pollution of Biomedical Data: Consequence of the Search for Hub Genes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Without Spatiotemporal Consideration. Mol Diagn Ther. 2021 May;25(3):387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-021-00527-5. Epub 2021 May 5. Erratum for: Mol Diagn Ther. 2021 Jan;25(1):9-27. PMID: 33950420; PMCID: PMC8276865. [CrossRef]

- Arya, A. K., Bhadada, S. K., Singh, P., Sachdeva, N., Saikia, U. N., Dahiya, D., ... & Rao, S. D. (2017). Promoter hypermethylation inactivates CDKN2A, CDKN2B and RASSF1A genes in sporadic parathyroid adenomas. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3123.

- Nagaraja, S., Quezada, M. A., Gillespie, S. M., Arzt, M., Lennon, J. J., Woo, P. J., ... & Monje, M. (2019). Histone variant and cell context determine H3K27M reprogramming of the enhancer landscape and oncogenic state. Molecular cell, 76(6), 965-980. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Ng, R., Chen, X., Steer, C. J., & Song, G. (2016). MicroRNA-21 is a potential link between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma via modulation of the HBP1-p53-Srebp1c pathway. Gut, 65(11), 1850-1860.

- Xu, C., Yan, Z., Zhou, L., & Wang, Y. (2013). A comparison of glypican-3 with alpha-fetoprotein as a serum marker for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology, 139(8), 1417-1424.

- Hack, S. P., Zhu, A. X., & Wang, Y. (2020). Augmenting anticancer immunity through combined targeting of angiogenic and PD-1/PD-L1 pathways: challenges and opportunities. Frontiers in immunology, 11, 598877.

- Mund, C., Brueckner, B., & Lyko, F. (2006). Reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes by DNA methyltransferase inhibitors: basic concepts and clinical applications. Epigenetics, 1(1), 8-14.

- Thomas, M. L., & Marcato, P. (2018). Epigenetic modifications as biomarkers of tumor development, therapy response, and recurrence across the cancer care continuum. Cancers, 10(4), 101.

- Li, X., Ramadori, P., Pfister, D., Seehawer, M., Zender, L., & Heikenwalder, M. (2021). The immunological and metabolic landscape in primary and metastatic liver cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 21(9), 541-557. [CrossRef]

- Michalak, T. I. (2023). The initial hepatitis B virus-hepatocyte genomic integrations and their role in hepatocellular oncogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(19), 14849. [CrossRef]

- Gui, M., Huang, S., Li, S., Chen, Y., Cheng, F., Liu, Y., ... & Zhou, G. (2024). Integrative single-cell transcriptomic analyses reveal the cellular ontological and functional heterogeneities of primary and metastatic liver tumors. Journal of Translational Medicine, 22(1), 206.

- Ye, B., Liu, X., Li, X., Kong, H., Tian, L., & Chen, Y. (2015). T-cell exhaustion in chronic hepatitis B infection: current knowledge and clinical significance. Cell death & disease, 6(3), e1694-e1694. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Lyu, T., Cao, Y., & Feng, H. (2021). Role of TCF-1 in differentiation, exhaustion, and memory of CD8+ T cells: A review. The FASEB Journal, 35(5), e21549.

- Akkız, H. (2023). Emerging role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in progression and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(4), 3941. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Ramadori, P., Pfister, D., Seehawer, M., Zender, L., & Heikenwalder, M. (2021). The immunological and metabolic landscape in primary and metastatic liver cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 21(9), 541-557.

- Yuan, Y., Wu, D., Li, J., Huang, D., Zhao, Y., Gao, T., ... & Tang, Y. (2023). Mechanisms of tumor-associated macrophages affecting the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1217400.

- Sükei, T., Palma, E., & Urbani, L. (2021). Interplay between cellular and non-cellular components of the tumour microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers, 13(21), 5586. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A., Xiong, M., Tang, B., Jiang, A., Shen, J., Liu, Z., ... & Luo, P. (2025). Decoding the hepatic fibrosis-hepatocellular carcinoma axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Hepatology International, 1-28.

- Saw, P. E., Liu, Q., Wong, P. P., & Song, E. (2024). Cancer stem cell mimicry for immune evasion and therapeutic resistance. Cell Stem Cell, 31(8), 1101-1112.

- Andrews, L. P., Butler, S. C., Cui, J., Cillo, A. R., Cardello, C., Liu, C., ... & Vignali, D. A. (2024). LAG-3 and PD-1 synergize on CD8+ T cells to drive T cell exhaustion and hinder autocrine IFN-γ-dependent anti-tumor immunity. Cell, 187(16), 4355-4372. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X. Y., Wu, K. M., & He, X. X. (2021). Advances in drug development for hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical trials and potential therapeutic targets. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 40(1), 172. [CrossRef]

- Hedrich, V., Breitenecker, K., Djerlek, L., Ortmayr, G., & Mikulits, W. (2021). Intrinsic and extrinsic control of hepatocellular carcinoma by TAM receptors. Cancers, 13(21), 5448.

- Lindblad, K. E., Ruiz de Galarreta, M., & Lujambio, A. (2021). Tumor-intrinsic mechanisms regulating immune exclusion in liver cancers. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 642958.

- Bhange, M., & Telange, D. (2025). Convergence of nanotechnology and artificial intelligence in the fight against liver cancer: a comprehensive review. Discover Oncology, 16(1), 77. [CrossRef]

- Bhange, M., & Telange, D. (2025). Convergence of nanotechnology and artificial intelligence in the fight against liver cancer: a comprehensive review. Discover Oncology, 16(1), 77.

- Calderaro, J., Žigutytė, L., Truhn, D., Jaffe, A., & Kather, J. N. (2024). Artificial intelligence in liver cancer, new tools for research and patient management. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 21(8), 585-599. [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M., Dallio, M., Napolitano, C., Basile, C., Di Nardo, F., Vaia, P., ... & Federico, A. (2025). Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Human Cancer: Is It Time to Update the Diagnostic and Predictive Models in Managing Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)?. Diagnostics, 15(3), 252. [CrossRef]

- Mansur, A., Vrionis, A., Charles, J. P., Hancel, K., Panagides, J. C., Moloudi, F., ... & Daye, D. (2023). The role of artificial intelligence in the detection and implementation of biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma: outlook and opportunities. Cancers, 15(11), 2928.

- Ahmed, E. A., El-Derany, M. O., Anwar, A. M., Saied, E. M., & Magdeldin, S. (2022). Metabolomics and lipidomics screening reveal reprogrammed signaling pathways toward cancer development in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(1), 210. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Yan, C., Zhu, J., Chen, X., Fu, Q., Zhang, H., ... & Fang, W. (2020). Anti–PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy employed in treating hepatitis B virus infection–related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a literature review. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 1037.

- Tiwari, A., Mishra, S., & Kuo, T. R. (2025). Current AI technologies in cancer diagnostics and treatment. Molecular Cancer, 24(1), 159. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R., Li, J., Lin, X., Yang, Y., Liu, B., Lan, T., ... & Wu, B. (2023). Peripheral immune characteristics of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Frontiers in Immunology, 14, 1079495. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N., & Kaushik, P. (2025). Integration of AI in healthcare systems, A discussion of the challenges and opportunities of integrating AI in healthcare systems for disease detection and diagnosis. AI in Disease Detection: Advancements and Applications, 239-263.

- Ferraro, S., Biganzoli, E. M., Castaldi, S., & Plebani, M. (2022). Health technology assessment to assess value of biomarkers in the decision-making process. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM), 60(5), 647-654. [CrossRef]

- Horgan, D., Ciliberto, G., Conte, P., Baldwin, D., Seijo, L., Montuenga, L. M., ... & Curigliano, G. (2020). Bringing greater accuracy to europe’s healthcare systems: The unexploited potential of biomarker testing in oncology. Biomedicine hub, 5(3), 1-42. [CrossRef]

- Graig, L. A., Phillips, J. K., Moses, H. L., Committee on Policy Issues in the Clinical Development and Use of Biomarkers for Molecularly Targeted Therapies, & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Supportive Policy Environment for Biomarker Tests for Molecularly Targeted Therapies. In Biomarker Tests for Molecularly Targeted Therapies: Key to Unlocking Precision Medicine. National Academies Press (US).

- Van Poppel, H., Roobol, M. J., Chapple, C. R., Catto, J. W., N’Dow, J., Sønksen, J., ... & Wirth, M. (2021). Prostate-specific antigen testing as part of a risk-adapted early detection strategy for prostate cancer: European Association of Urology position and recommendations for 2021. European Urology, 80(6), 703-711. [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M., Oanh, B. T., Chen, C. J., Ngat, D. T., George, J., Kim, D. Y., ... & Sarno, R. (2025). Roadmap for HCC Surveillance and Management in the Asia Pacific. Cancers, 17(12), 1928. [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, E., & Lee, H. M. (2024). Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2024: the multidisciplinary paradigm in an evolving treatment landscape. Cancers, 16(3), 666. [CrossRef]

- Albini, A., Trapani, D., Bertolini, F., Noonan, D. M., Orecchia, R., & Corso, G. (2025). From combination early detection to multicancer testing: shifting cancer care toward proactive prevention and interception. Cancer Prevention Research, OF1-OF20. [CrossRef]

| Type | Mechanisms | Example |

|---|---|---|

| A-to-I Editing | Adenosine is converted to inosine by ADAR enzymes. Inosine is read as guanosine during translation. | Common in the brain; affects neurotransmitter receptors. |

| C-to-U Editing | Cytidine is deaminated to uridine by cytidine deaminases. | Alters the ApoB gene in the intestine, producing a shorter protein. |

| U Insertion/Deletion | Uridines are inserted or deleted, often in mitochondrial RNA. | Found in trypanosomes (parasitic protozoa). |

| Therapy Type | Mechanism | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | Block DNA methylation | Azacitidine for leukemia |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Loosen chromatin to reactivate genes | Vorinostat for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma |

| miRNA Modulators | Restore normal miRNA levels | Experimental in lung and breast cancers |

| Combination Therapies | Pair epi-drugs with chemo or immunotherapy | Enhances response and reduces resistance |

| Area | Epigenetic Role | Proteomic Role | Personalized Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Therapy | Identifies silenced tumor suppressors | Tracks oncogenic protein activity | Matches patients to targeted treatments. |

|

Autoimmune Disorders |

Reveals immune gene dysregulation | Measures inflammatory protein levels | Adjusts immunosuppressive regimens |

| Mental Health | Links stress to gene expression changes | Detects neurotransmitter-related proteins | Guides psychiatric drug selection |

| Cardiovascular Risk | Shows methylation of lipid metabolism genes | Profiles heart-related enzymes and markers | Predicts heart attack risk and drug response |

| Feature | Impact on Liver Cancer Progression |

|---|---|

| Cell-type composition | Determines immune response and therapy resistance |

| Spatial organization | Influences drug delivery and metastatic potential |

| Gene expression profiles | Guide biomarker discovery and targeted therapies |

| Microenvironment dynamics | Shape tumor evolution and immune escape |

| Omics Type | What It Measures | Example in HCC Trials |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA mutations | TP53, CTNNB1 mutations |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression | miR-21, TCF7+ T cells |

| Proteomics | Protein levels | AFP, VEGF, PD-L1 |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, histone modifications | RASSF1A methylation |

| Metabolomics | Metabolic changes | Lipid metabolism shifts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).