Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Works

1.3. Motivation and Contributions

- We propose a prior information extraction method by leveraging LoS and echo sensing. In this method, the LoS sensing technology is employed to acquire the prominent LoS characteristics in UAV communication scenarios. Furthermore, based on echo sensing signals, this method incorporates radar signal processing technology to extract channel prior information. By integrating both LoS and echo sensing, we derive enhanced prior information to assist and refine CE.

- Based on the extracted LoS and echo sensing prior information, we propose a LoS and echo sensing-aided CE method for CA-enabled UAV-assisted OFDM systems. This method utilizes the sensed LoS component as a reference for setting detection threshold in CE, while incorporating echo-based sensing information to suppress noise and interference from false paths. By jointly leveraging LoS and echo sensing, an adaptive threshold for detecting transmission paths is designed, which is beneficial for enhancing CE accuracy.

- By leveraging the LoS path characteristics, we propose a path sharing-based channel reconstruction scheme. In this scheme, the PCC assists in reconstructing the channels of SCCs. This scheme exploits the shared transmission paths between the PCC and SCCs by utilizing Doppler-domain information to aid the reconstruction of the LoS path for SCCs. Furthermore, this reconstruction scheme is extended to NLoS paths, forming a three-stage channel reconstruction framework for SCCs. Consequently, the pilot overhead required for CE of SCCs is effectively reduced, thereby increasing the overall data transmission rate of CA systems.

1.4. Outline and Notation

2. System Model

2.1. CA-OFDM Communication Model

2.2. Echo Sensing Model

3. LoS and Echo Sensing-aided CE

3.1. Sensing Information Extraction

3.1.1. LoS Sensing

3.1.2. Echo Sensing Information Extraction

3.2. CE Enhancement for PCC

3.2.1. Sensing-based Prior Information Derivation

3.2.2. Sensing-aided CE for PCC

3.3. Sensing and Path-Sharing-aided Channel Reconstruction for SCCs

3.3.1. LoS path-based Reconstruction

3.3.2. NLoS path-based Reconstruction

3.3.3. Iterative Channel Reconstruction and Enhancement for SCCs

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

4.1. Parameter Settings

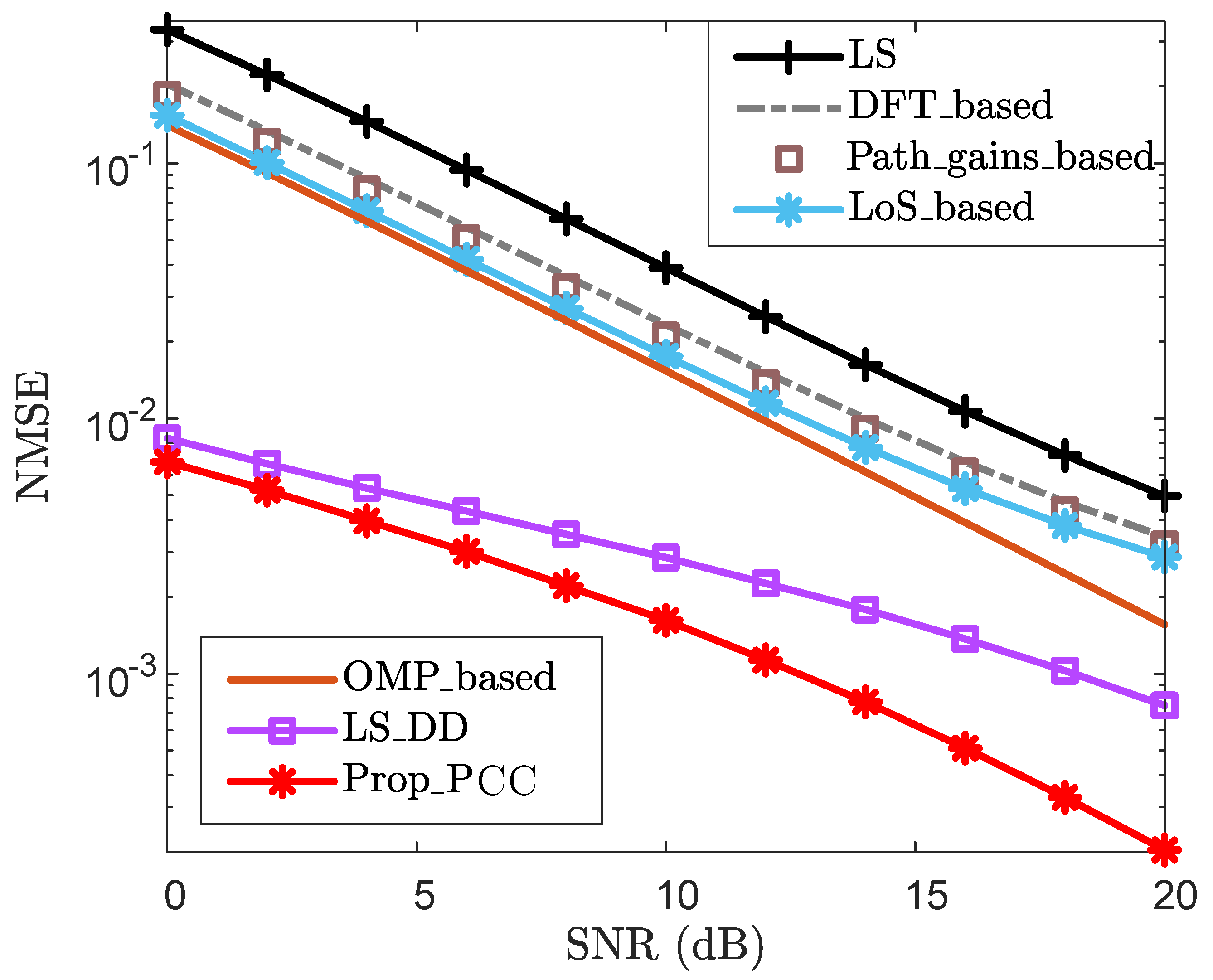

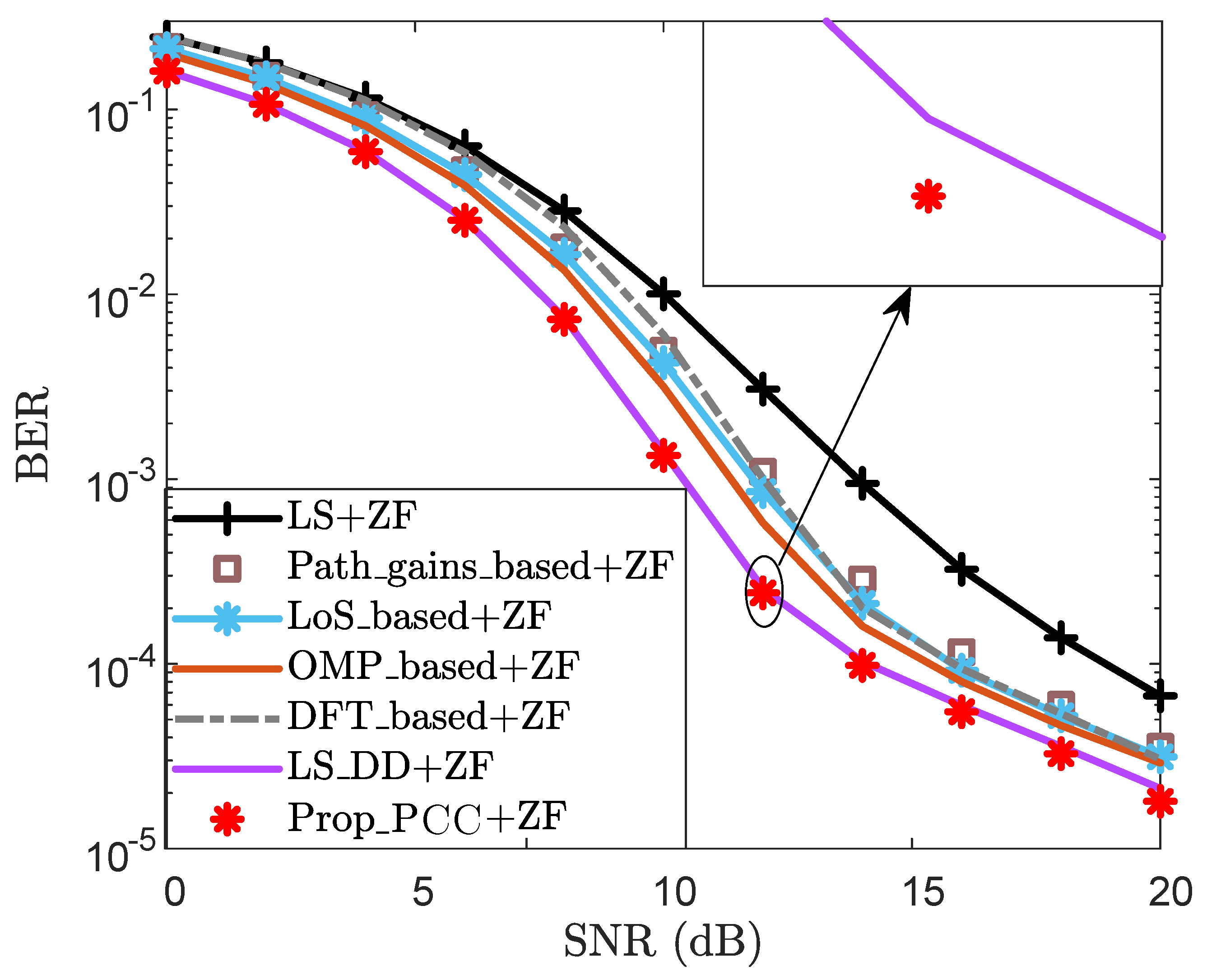

- LS: Classic least squares with linear interpolation;

- DFT_based: LS with DFT enhancement;

- OMP_based: Classic CS-based CE scheme;

- LoS_based: LoS sensing-based CE enhancement scheme in [16];

- LS_DD: LS enhancement with sensing-aided scheme in DD domain in [31];

- Path_gains_based: Path gain-based CE enhancement scheme in [32];

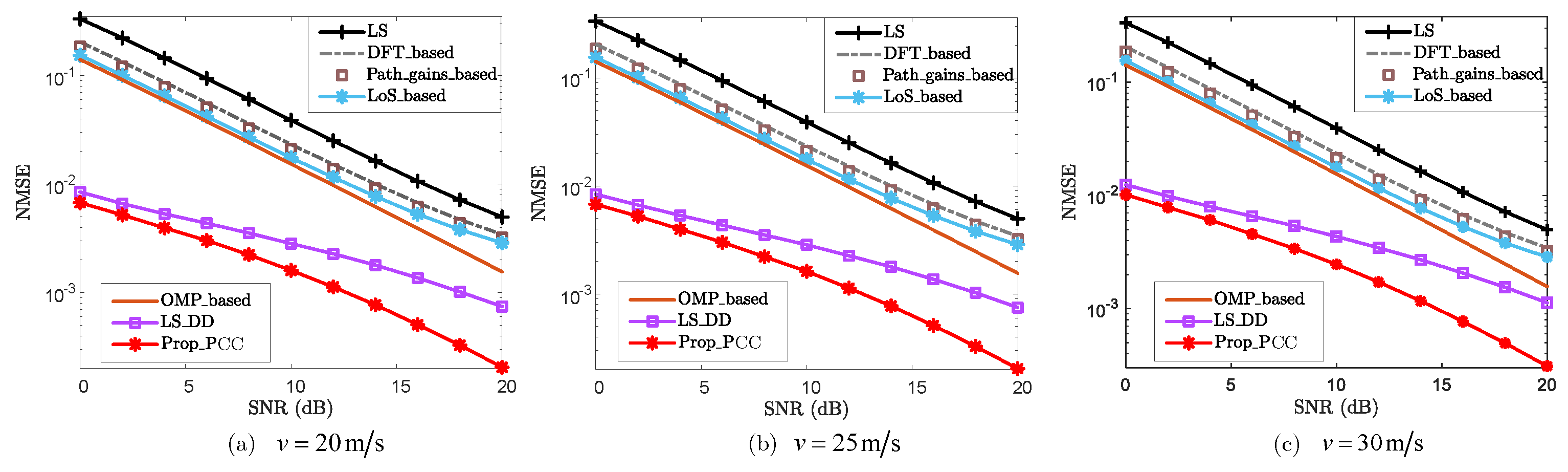

- Prop_PCC: Proposed CE enhancement scheme for PCC;

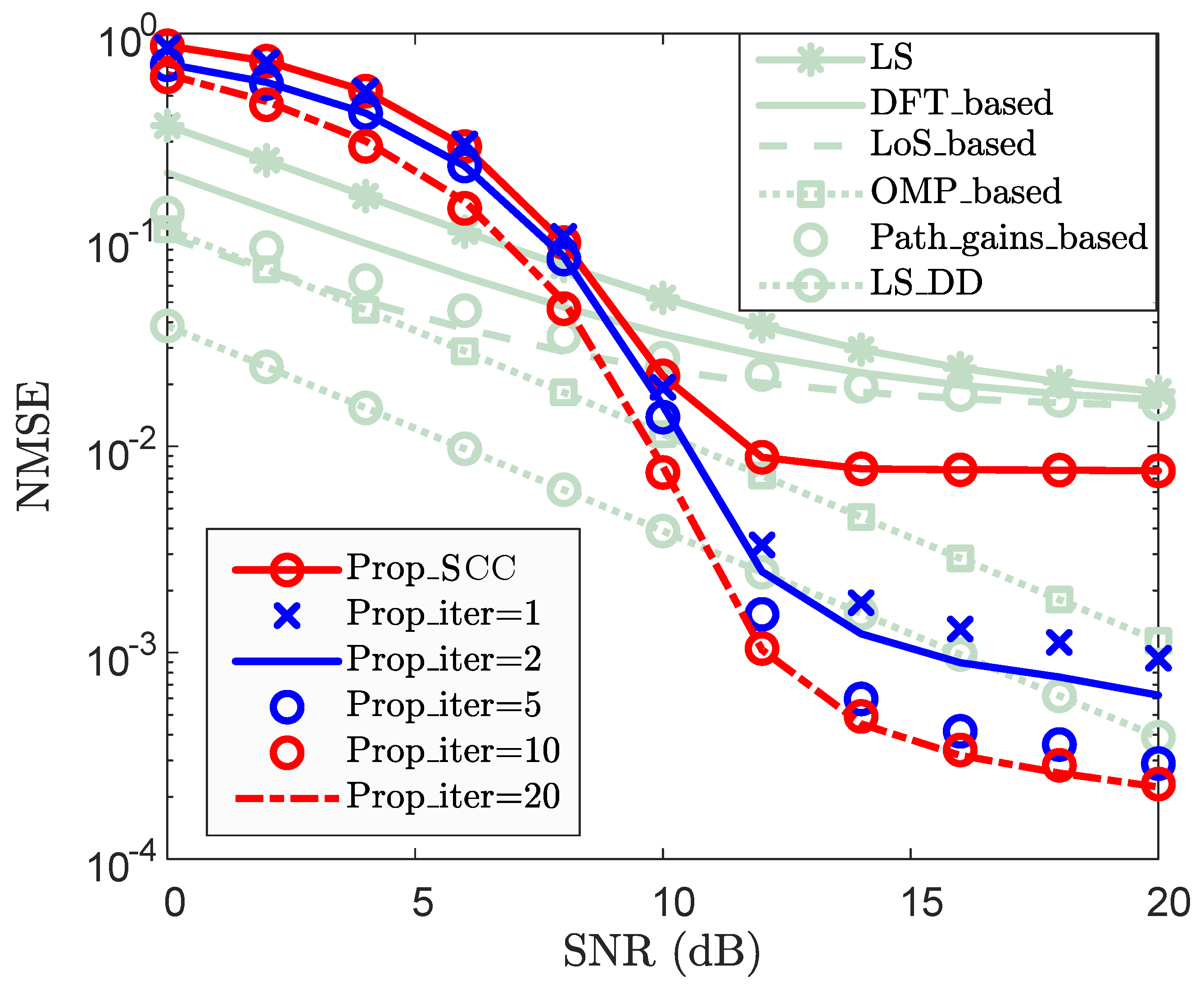

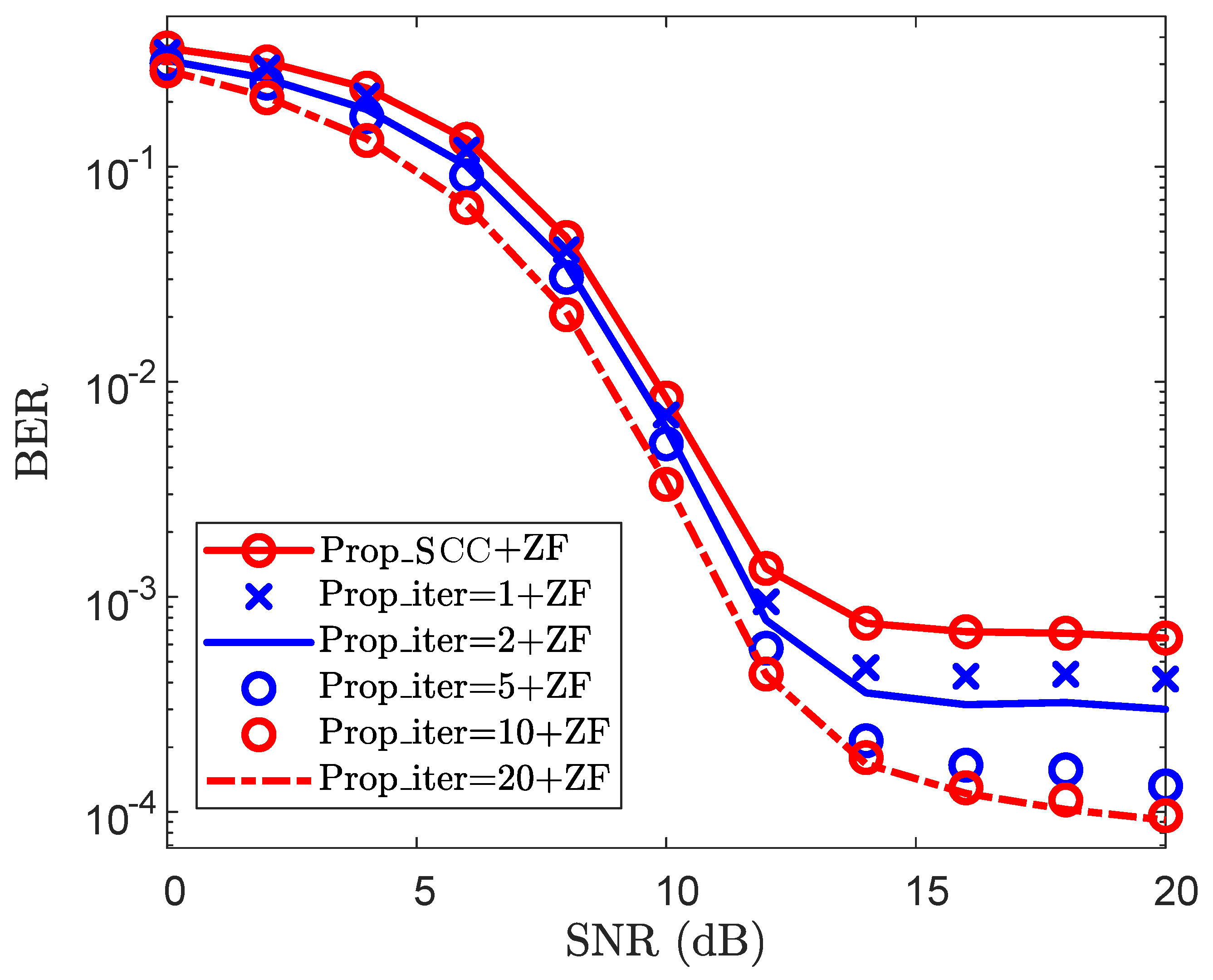

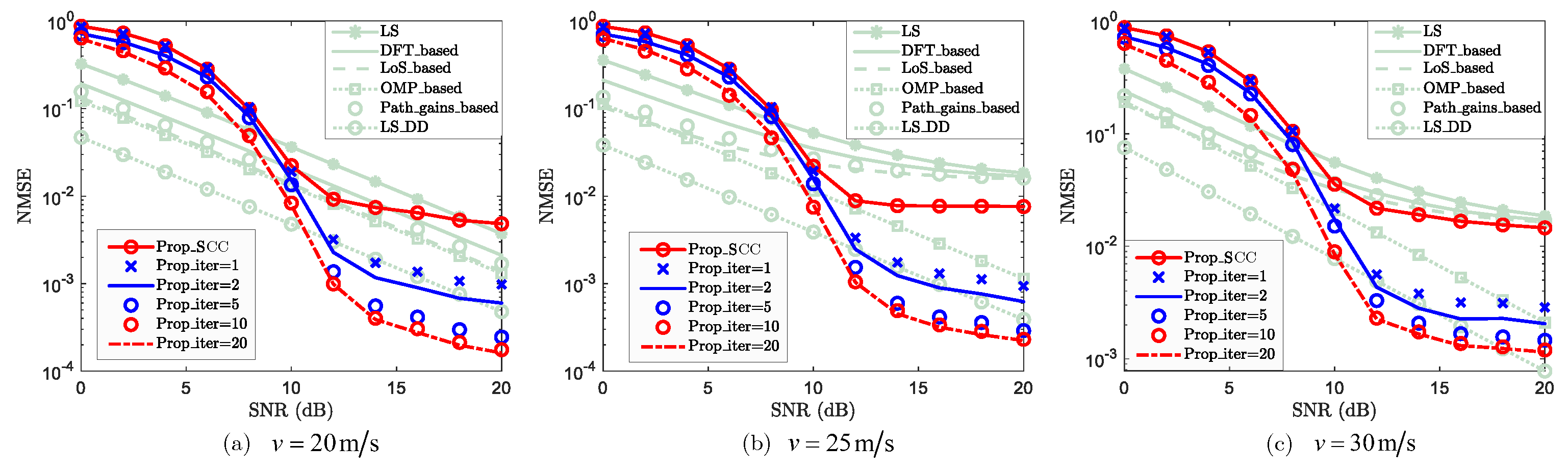

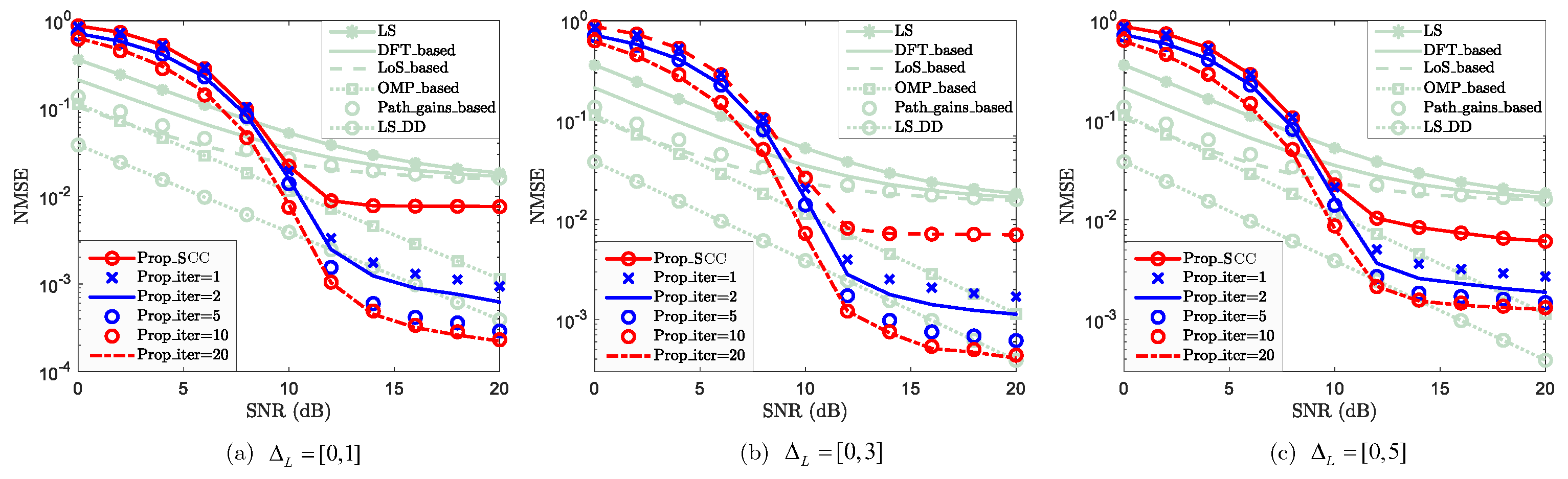

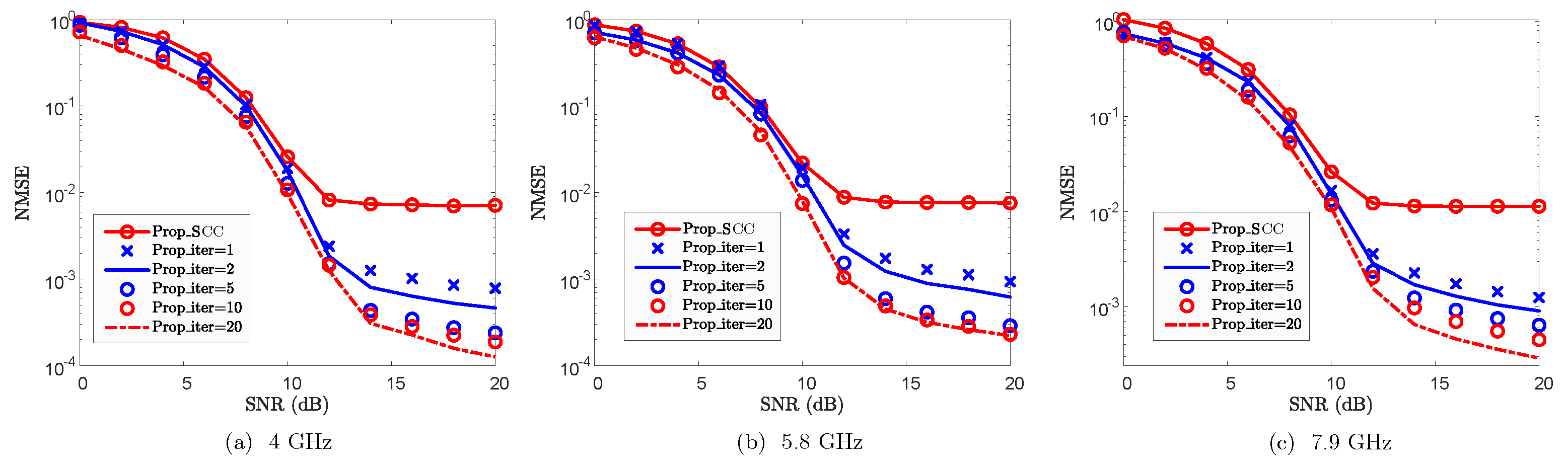

- Prop_SCC: Proposed channel reconstruction scheme for SCC;

- Prop_iter: Proposed iterative Channel Reconstruction and Enhancement for SCC;

4.2. Computational Complexity Analysis

4.3. Effectiveness Analysis

4.4. Robustness Analysis

4.4.1. Robustness Against Velocity v

4.4.2. Robustness Against Path-number Difference

4.4.3. Robustness Against Carrier Frequency of SCC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Y. Jiang, X. Li, G. Zhu, H. Li, J. Deng, K. Han, C. Shen, Q. Shi, and R. Zhang, “Integrated Sensing and Communication for Low Altitude Economy: Opportunities and Challenges,” IEEE Commun. Mag., pp. 1–7, early access, 2025.

- K. He, Q. Zhou, Z. Lian, Y. Shen, J. Gao, and Z. Shuai, “Spatiotemporal Precise Routing Strategy for Multi-UAV-Based Power Line Inspection With Integrated Satellite-Terrestrial Network,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 8418–8429, Dec. 2024.

- S. Meng, S. Wu, J. Zhang, J. Cheng, H. Zhou, and Q. Zhang, “Semantics-Empowered Space-Air-Ground-Sea Integrated Network: New Paradigm, Frameworks, and Challenges,” IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 140–183, Feb. 2025.

- G. Geraci, A. Garcia-Rodriguez, M. M. Azari, A. Lozano, M. Mezzavilla, S. Chatzinotas, Y. Chen, S. Rangan, and M. D. Renzo, “What Will the Future of UAV Cellular Communications Be? A Flight From 5G to 6G,” IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 1304–1335, 3rd Quart., 2022.

- Kumari, S.; Srinivas, K.K.; Kumar, P. Channel and Carrier Frequency Offset Equalization for OFDM Based UAV Communications Using Deep Learning. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2021, 25, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Lin, Z. Zhang, X. Pan, X. Luo, and Y. Cheng, “Joint Channel Estimation and Symbol Detection for UAV-Assisted Systems Using Tensor Framework,” in Proc. IEEE 22nd Int. Conf. Commun. Technol. (ICCT), Nanjing, China, Nov. 2022, pp. 1025–1030.

- S. Chen, C. Liu, and L. Huang, “Estimation of Pilot-assisted OFDM Channel Based on Multi-Resolution Deep Neural Networks,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Unmanned Syst. (ICUS), Guangzhou, China, Oct. 2022, pp. 764–769.

- He, B.; Ji, X.; Li, G.; Cheng, B. Key Technologies and Applications of UAVs in Underground Space: A Review. IEEE Trans. Cognit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 1026–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S. Single-Input Multiple-Output (SIMO) Cascode Low-Noise Amplifier with Switchable Degeneration Inductor for Carrier Aggregation. Sensors 2024, 24, 6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), “Feasibility study for further enhancements for E-UTRA (LTE Advanced),” 3GPP, Sophia Antipolis, France, Tech. Rep. 36.912 version 9.1.0 Release 9, Sep. 2009.

- G. Yuan, X. Zhang, W. Wang, and Y. Yang, “Carrier aggregation for LTE-advanced mobile communication systems,” IEEE Commun. Mag., vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 88–93, Feb. 2010.

- H. Liu, Z. Wei, J. Piao, H. Wu, X. Li, and Z. Feng, “Carrier Aggregation Enabled MIMO-OFDM Integrated Sensing and Communication,” IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun., vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 4532–4548, Jun. 2025.

- W. Lu, P. Si, Y. Gao, H. Han, Z. Liu, Y. Wu, and Y. Gong, “Trajectory and Resource Optimization in OFDM-Based UAV-Powered IoT Network,” IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1259–1270, Sep. 2021.

- Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, F.; Jia, W.; Zhang, W. Gridless Compressed Sensing Based Channel Estimation for UAV Wideband Communications With Beam Squint. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 10265–10277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Vlachos, C. Mavrokefalidis, K. Berberidis, and G. C. Alexandropoulos, “Improving Wideband Massive MIMO Channel Estimation with UAV State-Space Information,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., pp. 1–14, early access, 2025.

- Qing, C.; Liu, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, X.; Du, P. LoS Sensing-Based Channel Estimation in UAV-Assisted OFDM Systems. IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Zhu, Y. Han, L. Wang, L. Xu, Y. Zhang, and A. Fei, “Pilot Optimization for OFDM-Based ISAC Signal in Emergency IoT Networks,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 11, no. 18, pp. 29 600–29 614, Sep. 2024.

- Wang, J.; Chen, S. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Secrecy Rate Optimization for Simultaneously Transmitting and Reflecting Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface-Assisted Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Integrated Sensing and Communication Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. Song, Y. Zeng, Y. Yang, Z. Ren, G. Cheng, X. Xu, J. Xu, S. Jin, and R. Zhang, “An Overview of Cellular ISAC for Low-Altitude UAV: New Opportunities and Challenges,” IEEE Commun. Mag., pp. 1–8, early access, 2025.

- J. Mu, R. Zhang, Y. Cui, N. Gao, and X. Jing, “UAV Meets Integrated Sensing and Communication: Challenges and Future Directions,” IEEE Commun. Mag., vol. 61, no. 5, pp. 62–67, May 2023.

- W. Yuan, Z. Wei, S. Li, J. Yuan, and D. W. K. Ng, “Integrated Sensing and Communication-Assisted Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Transmission for Vehicular Networks,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process., vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 1515–1528, Nov. 2021.

- Y. Liu, I. Al-Nahhal, O. A. Dobre, and F. Wang, “Deep-Learning Channel Estimation for IRS-Assisted Integrated Sensing and Communication System,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 6181–6193, May 2023.

- Z. Huang, K. Wang, A. Liu, Y. Cai, R. Du, and T. X. Han, “Joint Pilot Optimization, Target Detection and Channel Estimation for Integrated Sensing and Communication Systems,” IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun., vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 10 351–10 365, Dec. 2022.

- Liu, Y.; Al-Nahhal, I.; Dobre, O.A.; Wang, F.; Shin, H. Extreme Learning Machine-Based Channel Estimation in IRS-Assisted Multi-User ISAC System. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 6993–7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhao, A. Tang, and X. Wang, “Reference Signal Design and Power Optimization for Energy-Efficient 5G V2X Integrated Sensing and Communications,” IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 379–392, Mar. 2023.

- X. Chen, Z. Feng, J. Andrew Zhang, Z. Wei, X. Yuan, and P. Zhang, “Sensing-Aided Uplink Channel Estimation for Joint Communication and Sensing,” IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 441–445, Mar. 2023.

- K. Xu, X. Xia, C. Li, C. Wei, W. Xie, and Y. Shi, “Channel Feature Projection Clustering Based Joint Channel and DoA Estimation for ISAC Massive MIMO OFDM System,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 3678–3689, Mar. 2024.

- X. Yang, H. Li, Q. Guo, J. A. Zhang, X. Huang, and Z. Cheng, “Sensing Aided Uplink Transmission in OTFS ISAC With Joint Parameter Association, Channel Estimation and Signal Detection,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 73, no. 6, pp. 9109–9114, Jun. 2024.

- K. Chen and C. Qi, “Joint Sparse Bayesian Learning for Channel Estimation in ISAC,” IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 1825–1829, Aug. 2024.

- Y. Li, F. Liu, Z. Du, W. Yuan, Q. Shi, and C. Masouros, “Frame Structure and Protocol Design for Sensing-Assisted NR-V2X Communications,” IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput., vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 11 045–11 060, Dec. 2024.

- C. Qing, W. Hu, Z. Liu, G. Ling, X. Cai, and P. Du, “Sensing-Aided Channel Estimation in OFDM Systems by Leveraging Communication Echoes,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 11, no. 23, pp. 38 023–38 039, Dec. 2024.

- B. Su and M.-Y. Wang, “Joint Channel Estimation Methods in Carrier Aggregation OFDM Systems,” in Proc. IEEE 79th Veh. Technol. Conf. (VTC Spring), Seoul, Korea (South), May 2014, pp. 1–5.

- C. G. Tsinos, F. Foukalas, T. Khattab, and L. Lai, “On Channel Selection for Carrier Aggregation Systems,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 808–818, Feb. 2018.

- R. M. Rao, V. Marojevic, and J. H. Reed, “Adaptive Pilot Patterns for CA-OFDM Systems in Nonstationary Wireless Channels,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 1231–1244, Feb. 2018.

- T. Xu and I. Darwazeh, “Transmission Experiment of Bandwidth Compressed Carrier Aggregation in a Realistic Fading Channel,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 4087–4097, May 2017.

- Z. Wei, H. Liu, X. Yang, W. Jiang, H. Wu, X. Li, and Z. Feng, “Carrier Aggregation Enabled Integrated Sensing and Communication Signal Design and Processing,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 3580–3596, Mar. 2024.

- Y. Li, X. Bian, and M. Li, “Denoising generalization performance of channel estimation in multipath time-varying OFDM systems,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 6, p. 3102, Mar. 2023.

- X. Yang, D. Zhai, R. Zhang, L. Liu, J. Du, and V. C. M. Leung, “A Geometry-Based Stochastic Channel Model for UAV-to-Ground Integrated Sensing and Communication Scenarios,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 5307–5320, Apr. 2025.

- M. Mirabella, P. D. Viesti, A. Davoli, and G. M. Vitetta, “An Approximate Maximum Likelihood Method for the Joint Estimation of Range and Doppler of Multiple Targets in OFDM-Based Radar Systems,” IEEE Trans. Commun., Aug. 2023.

- R. Xie, D. Hu, K. Luo, and T. Jiang, “Performance Analysis of Joint Range-Velocity Estimator With 2D-MUSIC in OFDM Radar,” IEEE Trans. Signal Process., vol. 69, pp. 4787–4800, Sep. 2021.

- Chu, P.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, J. Dual-Pulse Repeated Frequency Waveform Design of Time-Division Integrated Sensing and Communication Based on a 5G New Radio Communication System. Sensors 2023, 23, 9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Meng, Q. Wu, J. Xu, W. Chen, Z. Feng, R. Schober, and A. L. Swindlehurst, “UAV-Enabled Integrated Sensing and Communication: Opportunities and Challenges,” IEEE Wireless Commun., vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 97–104, Apr. 2024.

- P. Karpovich and T. P. Zielinski, “Integrated Sensing and Communication Using Random Padded OTFS with Reduced Interferences,” Sensors, vol. 25, no. 15, p. 4816, Aug. 2025.

- S. Lu, W. Yi, W. Liu, G. Cui, L. Kong, and X. Yang, “Data-Dependent Clustering-CFAR Detector in Heterogeneous Environment,” IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst., vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 476–485, Feb. 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).