Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Study of the Physicochemical and Technological Properties of PPI

2.3. Obtaining Biochar from Walnut Shell

2.4. Study of the Physicochemical and Technological Properties of WS Biochar

2.5. Study of the Sorption Capacity of WS Biochar to Iodine

2.6. Production of WS Biochar Based Fertilizer Under Laboratory Conditions

2.7. Plants Planting

2.8. Sample Preparation of Plant Specimens

2.9. Determination of Ascorbic Acid Concentration, Polyphenols in Plants

2.10. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of Samples (AOA)

2.11. Determination of the Total Iodine Content

2.12. Statistical Analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

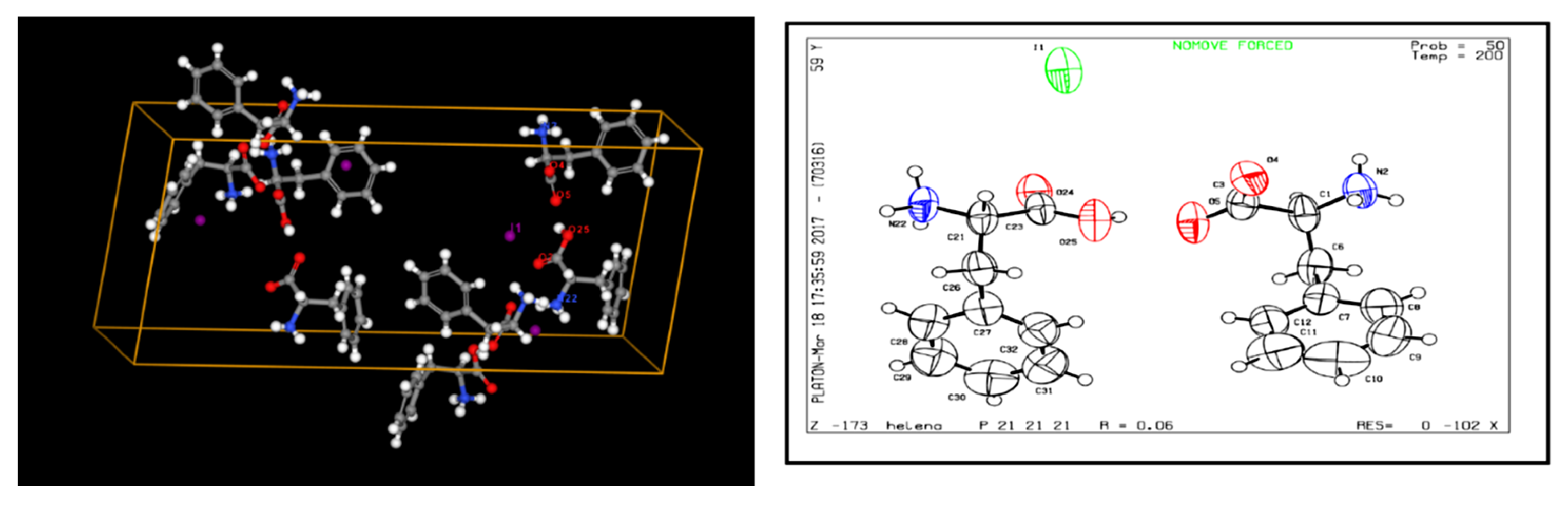

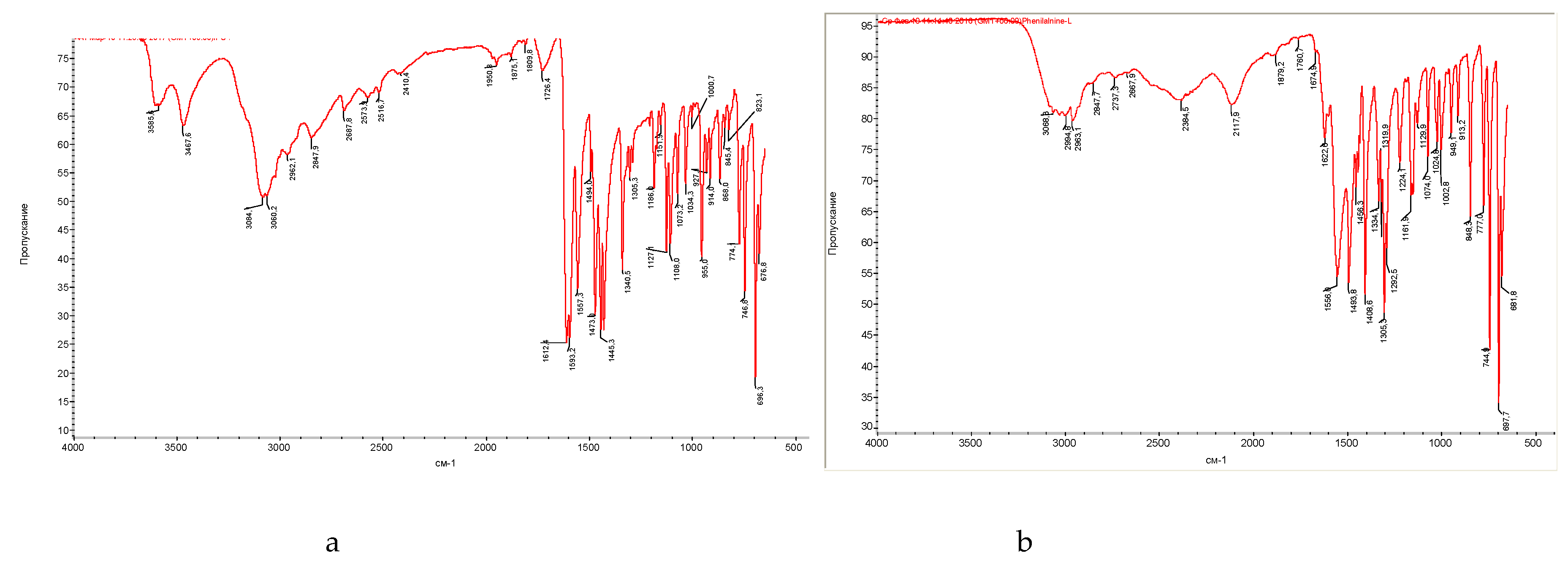

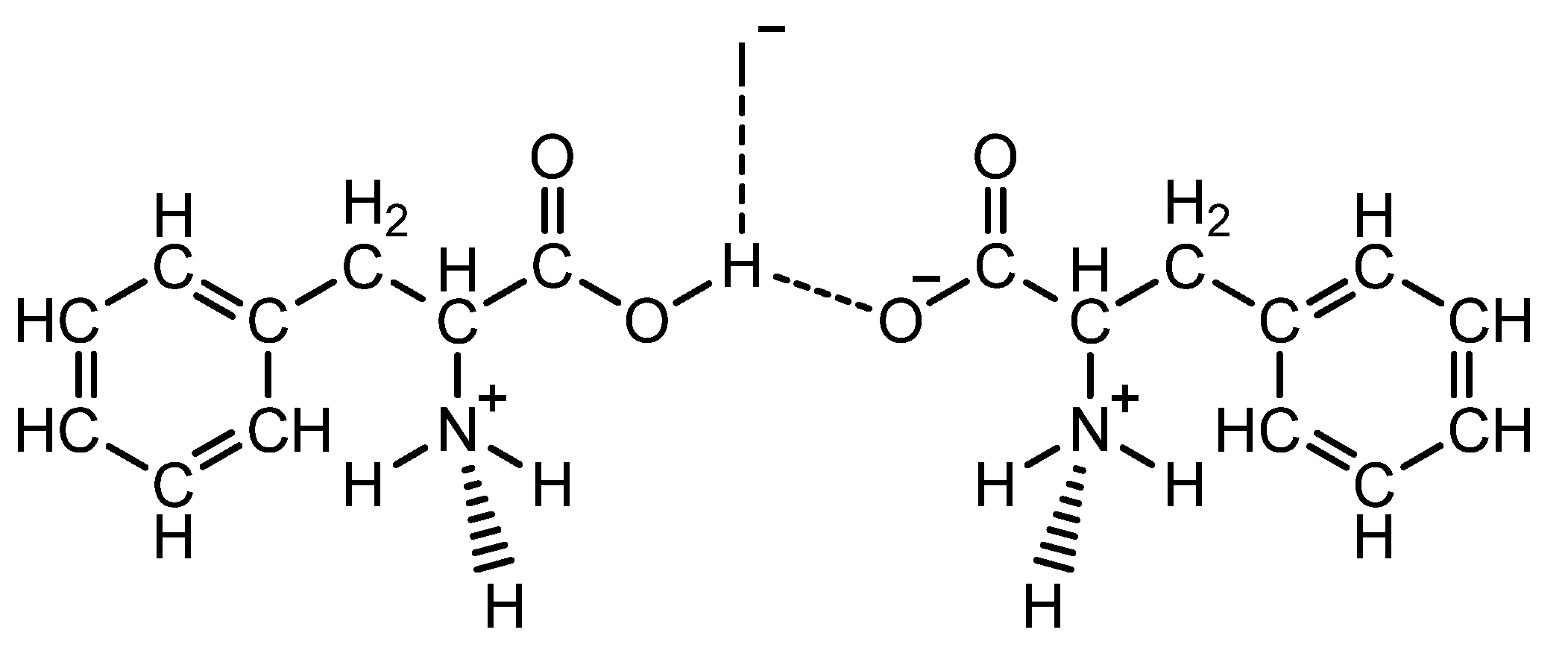

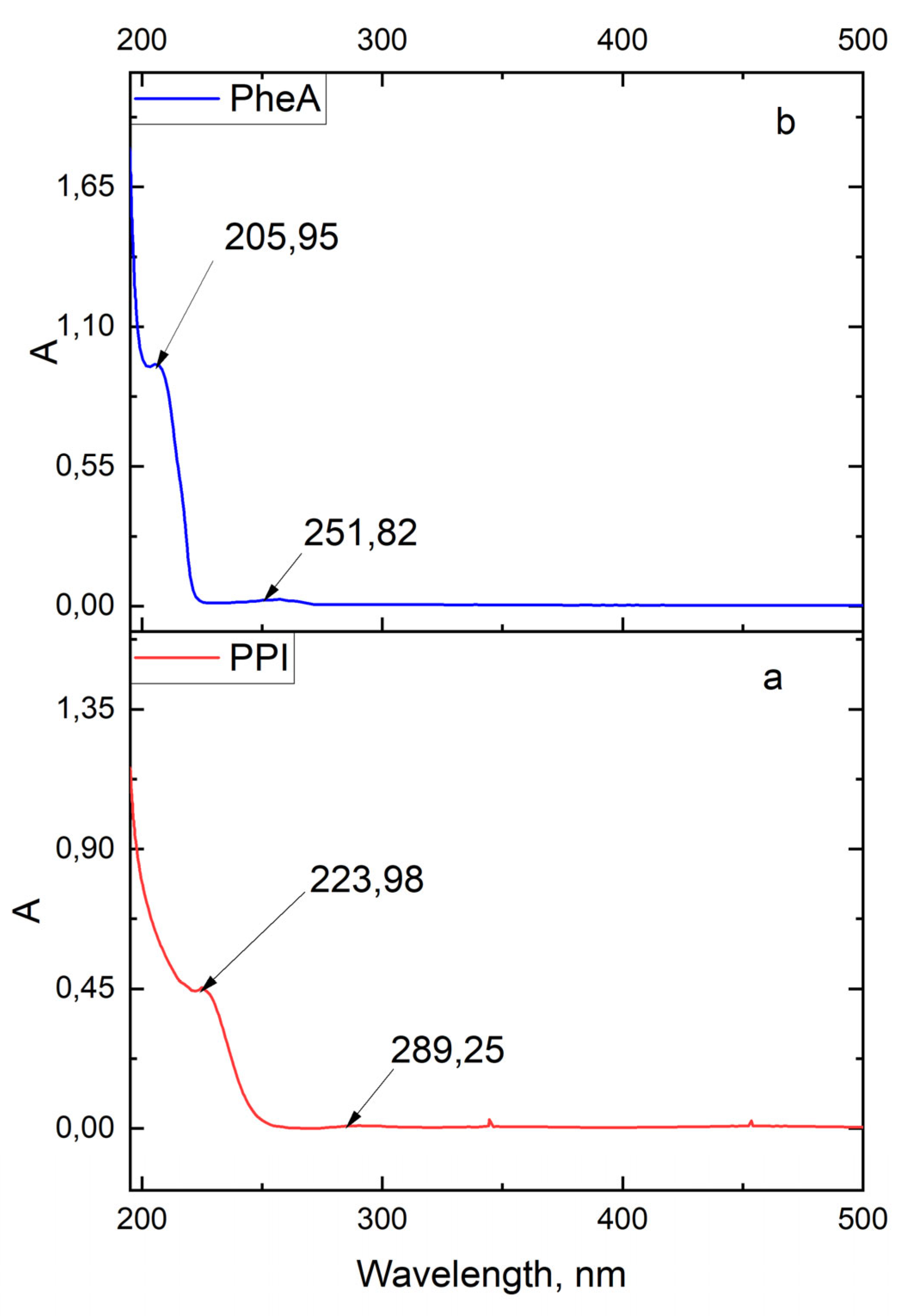

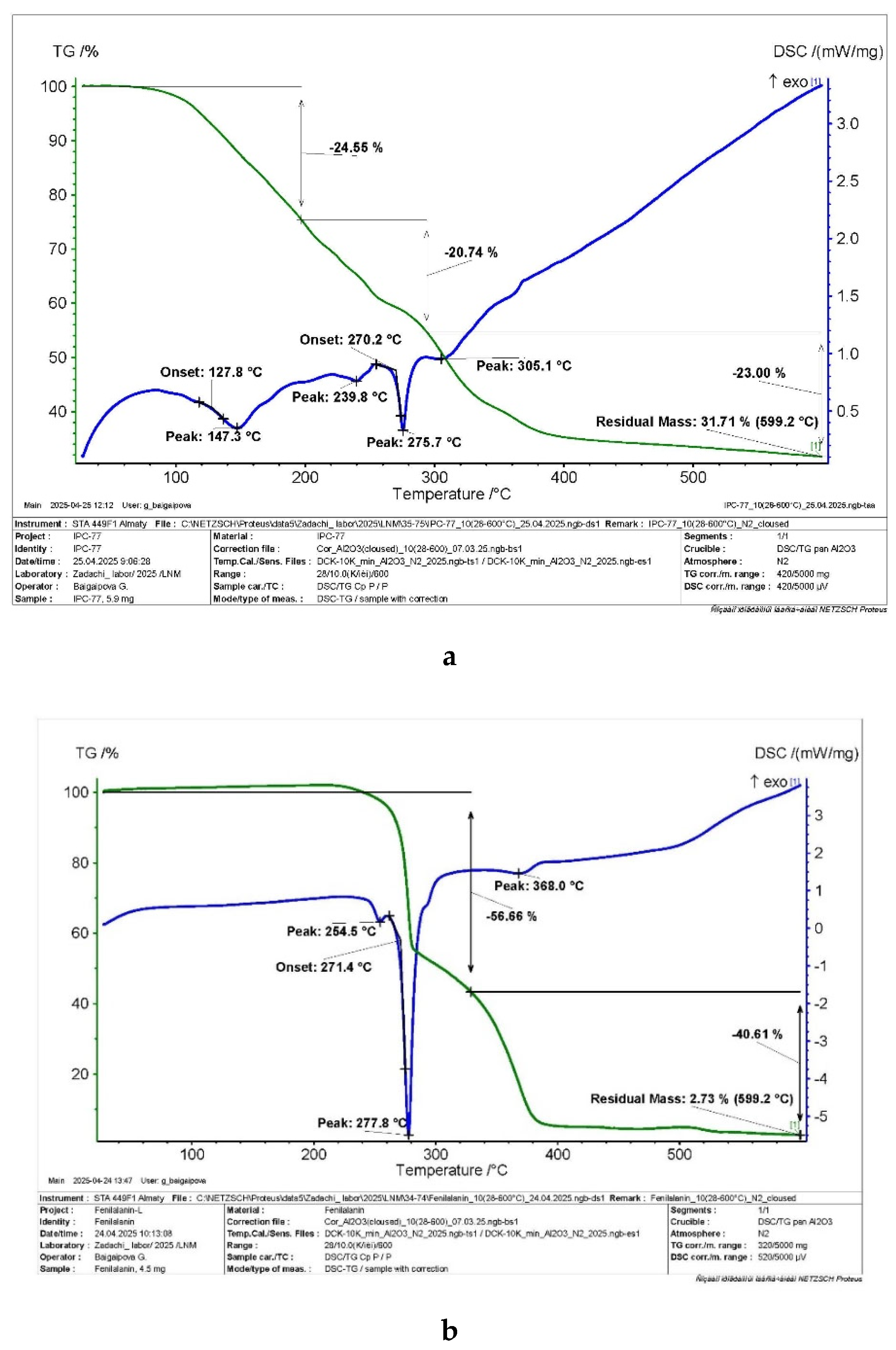

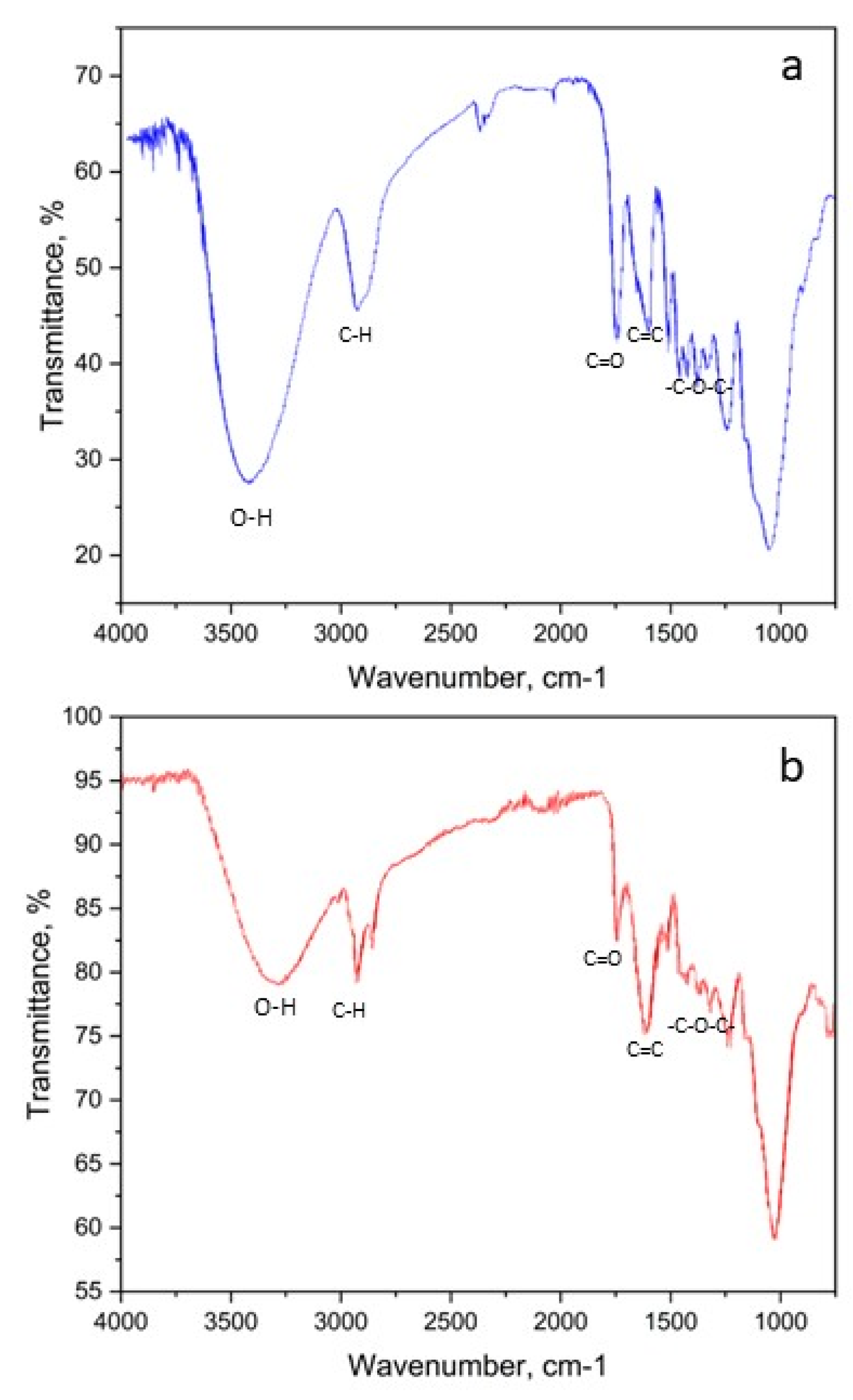

3.1. Determination of Physico-Chemical Parameters of PPI

| Band number | Phenylalanine band, cm-1 |

Acetone band, cm-1 |

PPI band, cm-1 |

Band description |

| 1 | - | - | 3585,6 | 3602-3544, ν -ОН, (intramolecular hydrogen bonds) |

| 2 | - | - | 3467,6 | 3470-3410, ν – NH2 |

| 3 | 3068,3 | - | - | ν ─N-H |

| 4 | - | - | 3084,1 | 3100-3070, ─NH3+ |

| 5 | - | - | 3060,2 | 3080-3030, ν ─СH (aromatic) |

| 6 | 2994,8 | 3015,0 | - | ν ─CH2, ─CH3 |

| 7 | 2963,1 | 2966,0 | 2962,1 | 2988-2949, νs –CН2 |

| 8 | - | 2942,0 | - | |

| 9 | 2847,7 | - | 2847,9 | 3300-2500, ν –ОН, ν ─NH+, ─NH2+, ─NH3+ |

| 10 | - | - | 2687,8 |

2700-2250, ν – NH+, - NH2+ |

| 11 | - | - | 2573,9 | |

| 12 | - | - | 2516,7 | |

| 13 | 2384,5 | - | - | ν ─С-NH+ |

| 14 | 2117,9 | - | - | |

| 15 | - | - | 1950,3 |

2000-1650, overtones of aromatic groups |

| 16 | - | - | 1875,1 | |

| 17 | - | - | 1809,8 | |

| 18 | - | 1730,0 | 1726,4 | 1730-1710, ν ─C=O |

| 19 | 1622,6 | - | - | ν ─C-NH3+ |

| 20 | - | - | 1612,4 |

1640-1530, ν ─C=O |

| 21 | - | - | 1593,2 | |

| 22 | 1556,0 | - | 1557,3 | |

| 23 | 1493,8 | - | 1494,0 | 1520-1490, δs NH3+, ν ─COO- |

| 24 | - | - | 1473,0 | 1525-1475, aromatic ring oscillation |

| 25 | 1456,3 | 1456,0 | 1445,3 | 1465-1440, aromatic ring oscillation, δ ─CH2, ─CH3 |

| 26 | - | 1434,0 | - | δ ─CH2, ─CH3 |

| 27 | 1408,6 | - | - | ν ─COO-…HOOC─ (dimers) |

| 28 | - | 1365,0 | 1340,5 | 1350-1280, ν – С-N, δ– CH-C=O |

| 29 | 1334,1 | - | - |

ν С6Н5─СН2─СН─NH (aromatic amines) |

| 30 | 1319,9 | - | - | |

| 31 | 1305,3 | - | 1305,3 | 1335-1300, fluctuations of ionic carboxyl in amino acids |

| 32 | 1292,5 | - | - | 1350-1280, ν – С-N |

| 33 | 1224,1 | 1227,0 | - |

δ ─CH2, ─CH3 |

| 34 | - | 1215,0 | - | |

| 35 | 1161,9 | - | 1186,0 |

1200-1100, ν ─C-N─ |

| 36 | 1129,9 | 1090,0 | 1127,1 | |

| 37 | - | - | 1108,0 | |

| 38 | 1074,0 | - | 1073,2 | 1110-1070, δ -СН in aromatic |

| 39 | 1024,8 | - | 1034,3 | 1070-1000, δ -СН in aromatic |

| 40 | 1002,8 | - | - | ν C6H5─ |

| 41 | 949,1 | - | 955,0 | 1000-960, δ -СН in aromatic |

| 42 | - | - | 927,1 |

955-890, δ – ОН |

| 43 | 913,2 | - | 914,0 | |

| 44 | - | 892,0 | 868,0 | 900-860, δ ─CH (in aromatic) |

| 45 | 848,3 | - | 845,4 | 900-650, δ – NН, ν ─C-N─ |

| 46 | 777,0 | 765,0 | 774,1 |

900-650, δ ─C-H |

| 47 | 744,9 | - | 746,8 | |

| 48 | 697,7 | 697,0 | 696,3 | |

| 49 | 681,8 | 530,0 | 676,8 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bulkdensity, g/cm3 | 0.73 |

| Particlesize, μm | 2.8-3.1 |

| Solubility | Soluble in water, DMSO, slightly soluble in ethanol, acetone and cyclohexane. |

| pH of aqueous solutions | 3.0-3.2 |

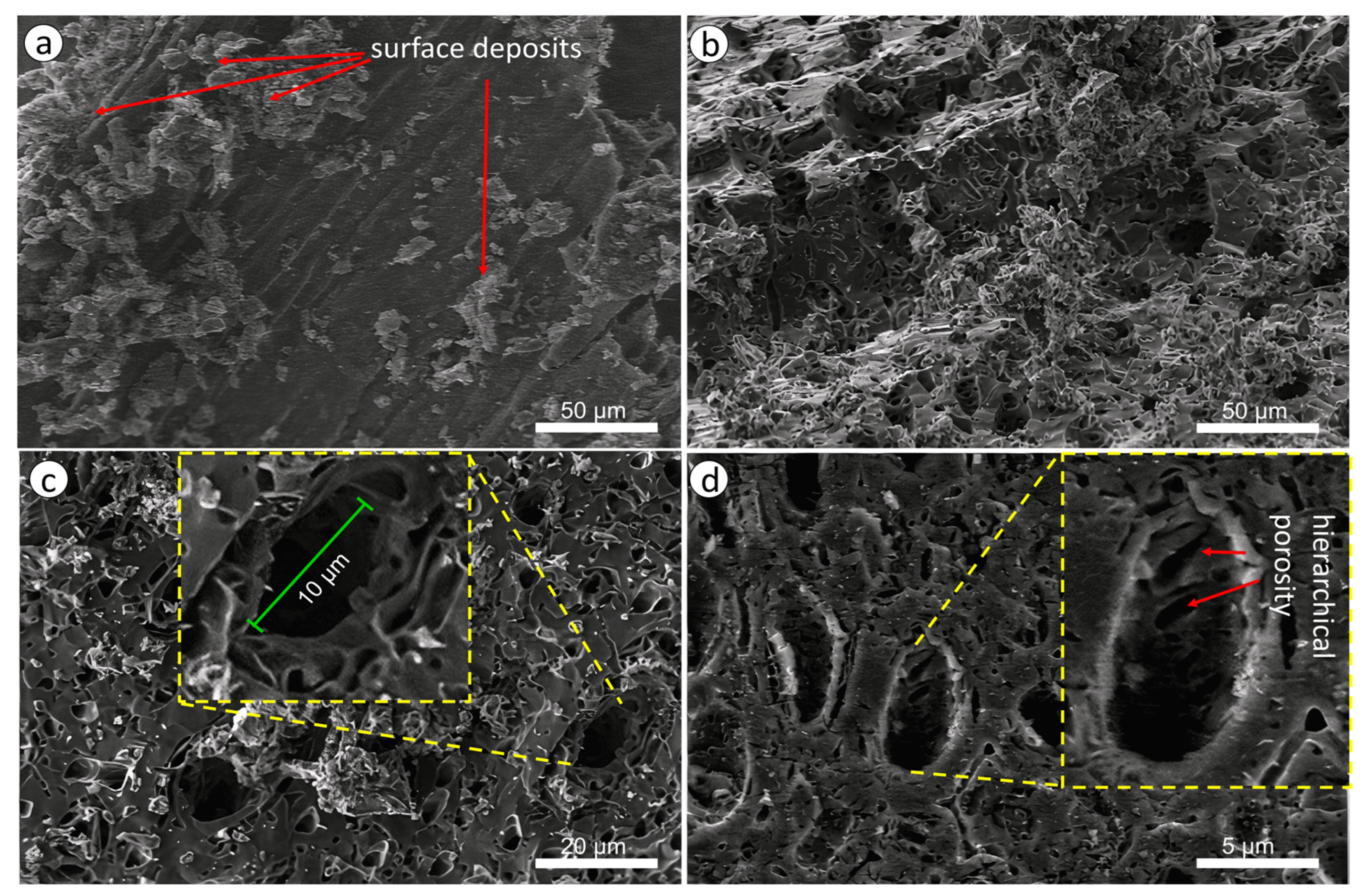

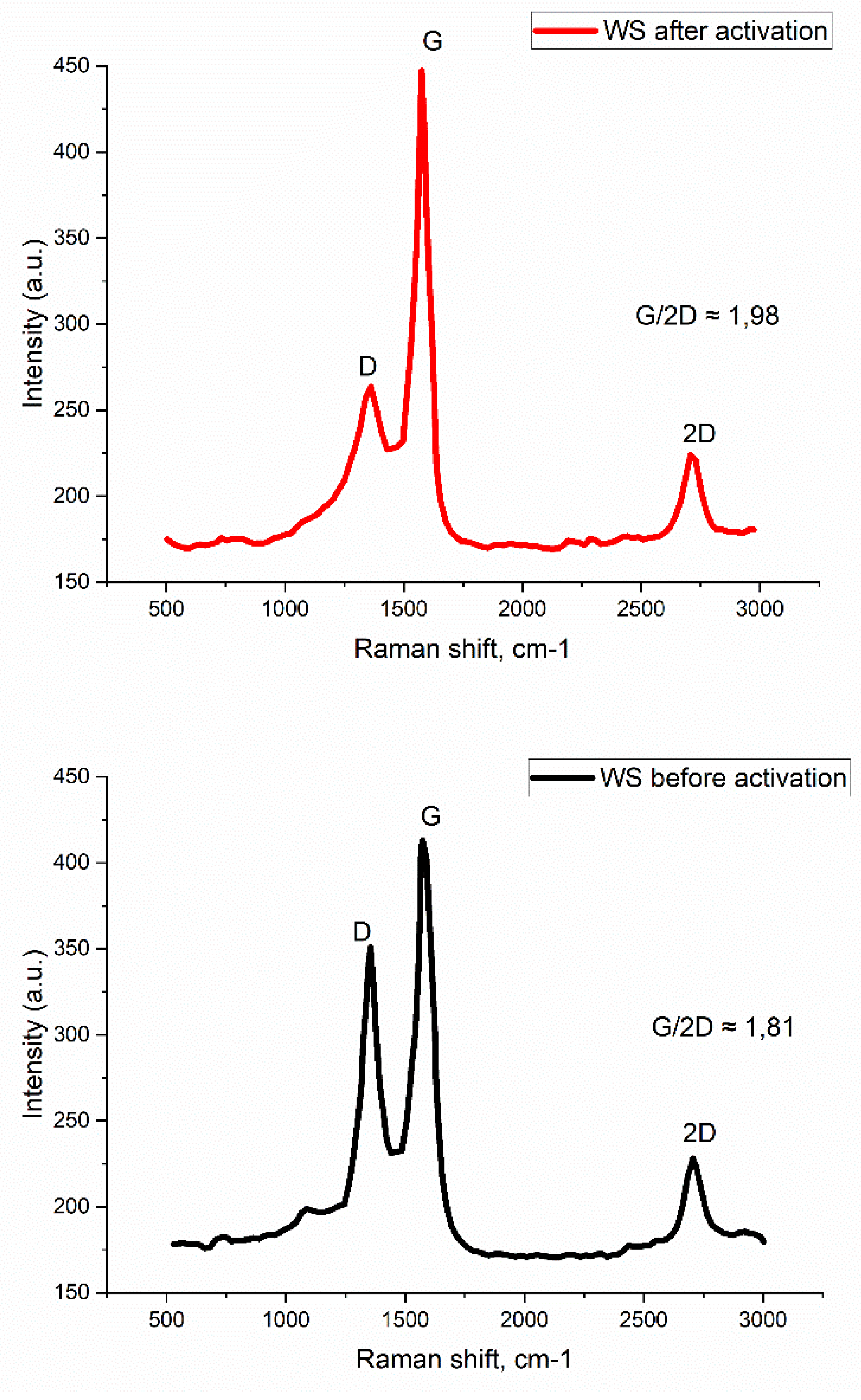

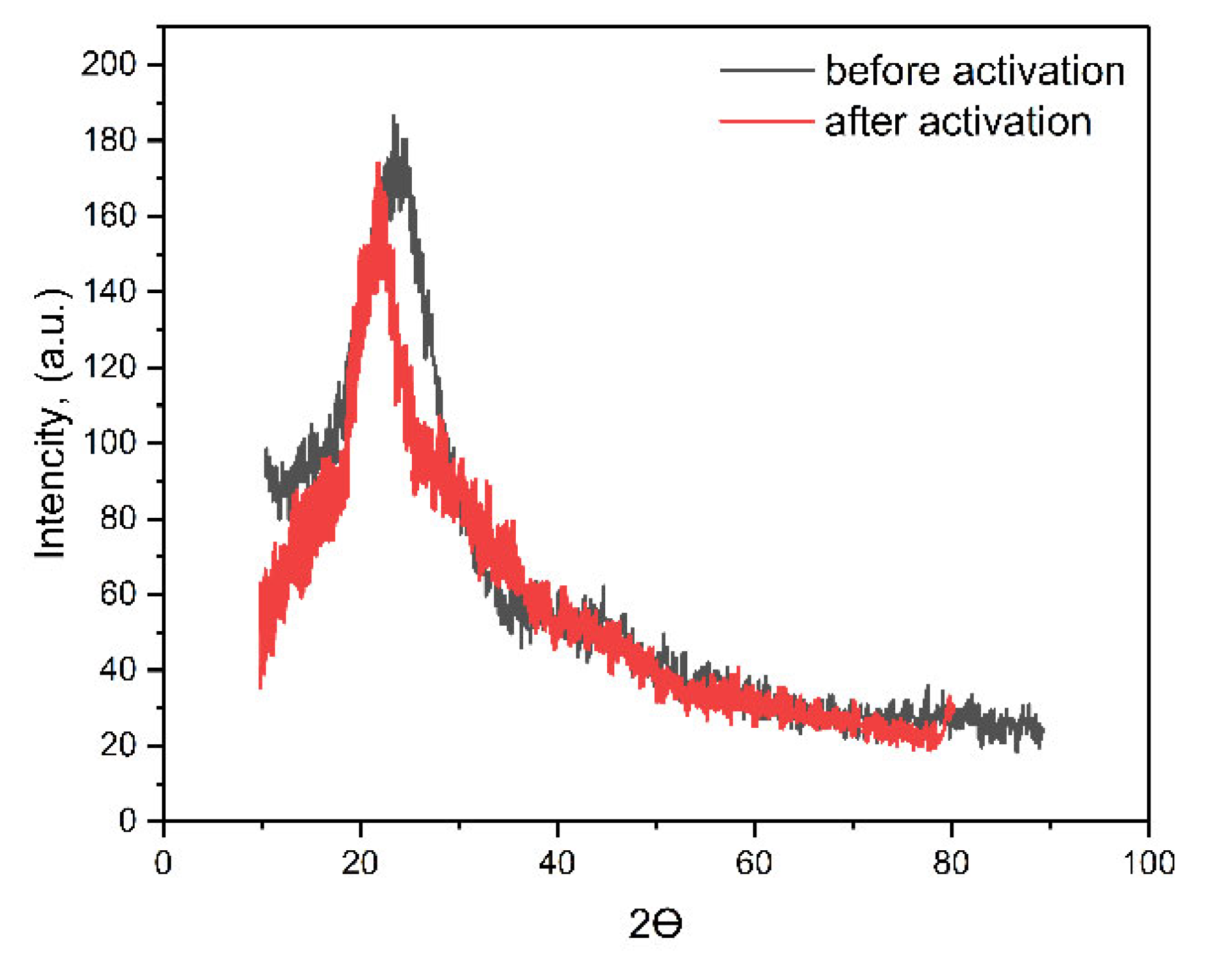

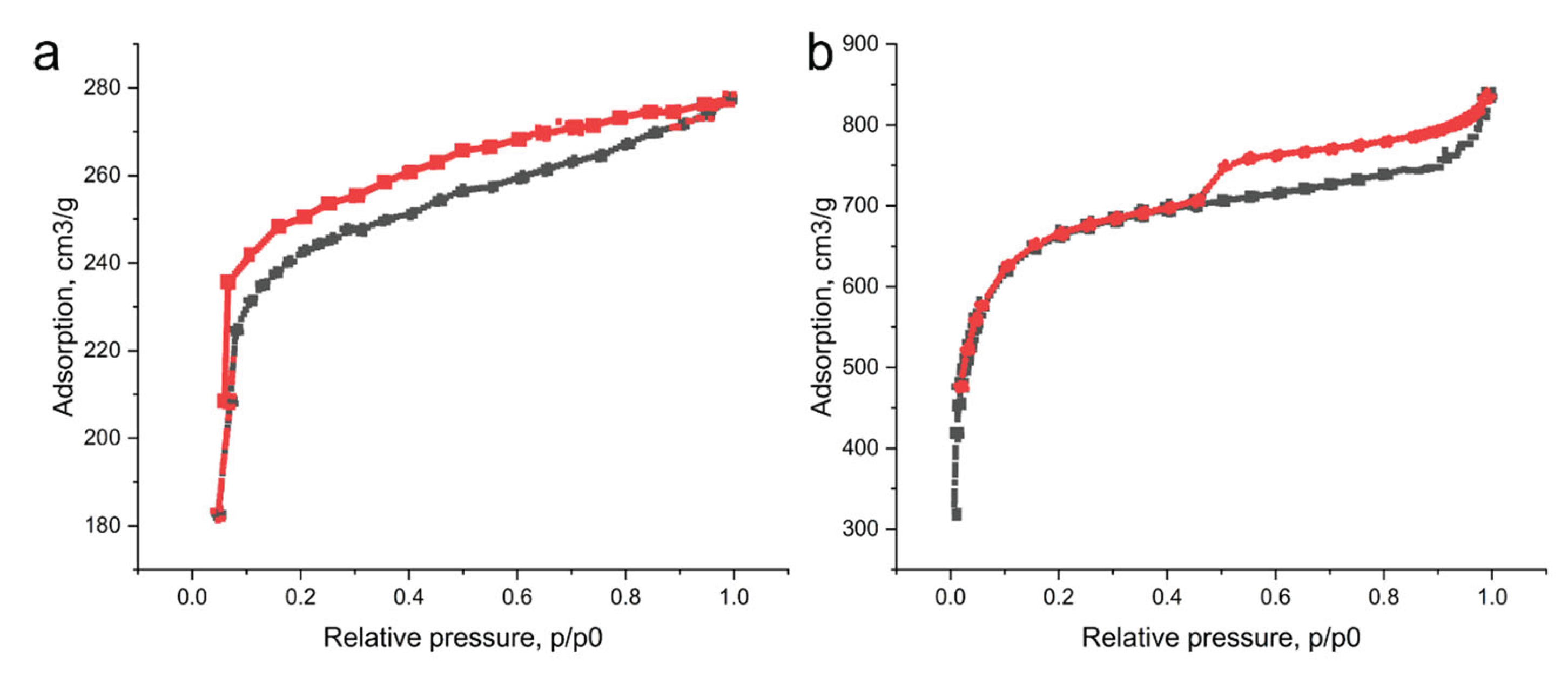

3.2. Investigation of the Characteristics of Biochar from Walnut Shells

| Biochar sample | Specific surface area according to BET, m2/g |

Volume of micropores, cm3/g |

Mesopore volume, cm3/g |

Iodine number, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS before activation | 269.4±25.8 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.06±0.01 | 283.8±17.6 |

| WS after activation by KOH | 878.3±65.4 | 0.67±0.06 | 0.27±0.02 | 712.3±48.6 |

3.3. Study of the Effect of Fertilizers on the Physiological Properties of Plants

| Plant processing option | Plant height, cm | Weight of leaves, g/plant | Weight of roots, g/plant | Dry residue of plant, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 28.33±1.55a | 65.04±7.51a* | 7.12±0.42a | 13.15±0,92a |

| Pure biochar | 27.58±1.36a | 74.56±7.33b | 6.94±0.35a | 11.82±1,07a |

| KI | 28.86±0,89a | 77.72±7.42b | 7.31±0.30a | 13.27±1,33a |

| BIOF | 28.63±1.43a | 86.55±8.13c | 8.25±0.41b | 12.35±1,78a |

3.4. The Effect of BIOF on the Content of Iodine and Organic Nitrogen in a Plant

| Plant processing option | Iodine, mg/kg of d.w. |

Organic Nitrogen mg/kg of d.w. |

||

| leaves | roots | leaves | roots | |

| Control | - | - | 34.88±2.75a | 18.63±1.64a |

| Pure biochar | - | - | 35.25±2.66a | 17.32±1.81a |

| KI | 7.11±0.72a | 9.27±0.83a | 39.74±3.41a | 22.05±1.39b |

| BIOF | 11.86±1.13b | 13.23±1.19b | 57.37±3.82b | 36.63±2.07c |

3.5. The Effect of BIOF on the Antioxidant Activity of Plants

| Plant processing option | Ascorbic acid, mg/100 g d.w. (dry weight) |

AOA, mg GA/g d.w. |

Polyphenols, mg GA/g d.w. |

| Control | 23.31±2.43a* | 29.64±3.14a | 18.62±1.54a |

| Pure biochar | 25.17±2.32a | 30.25±3.03a | 20.07±1.37a |

| KI | 23.97±2.84a | 42.04±3.32b | 21.15±1.25ab |

| BIOF | 36.46±2.74b | 44.48±4.18b | 23.79±1.84b |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPI | 1-carboxy-2-phenylethan-1-aminium iodide 2-azaniumyl-3-phenylpropanoate |

| BIOF | The granulated composition PPI + biochar |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| WS | Walnut shell |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction analysis |

| AOA | Antioxidant activity |

References

- Ilin, A. I. (2017). Experimental Crystal Structure Determination (CCDC 1036670). Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Paretskaya, A.N. N.A. Paretskaya, A.N. Sabitov, R.A. Islamov, R.A. Tamazyan, S.Zh. Tokmoldin, A.I. Ilin, K.S. Martirosyan (2017). Phenylalanine – Iodine Complex and its Structure. News of The National Academy of Sciences of The Republic of Kazakhstan, Physico-Mathematical Series, ISSN 1991-346Х, Volume 2, Number 312 (2017), pp. 5 – 9.

- Grzanka, M.; Smoleń, S.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Grzanka, D. (2022). Synthesis of Organic Iodine Compounds in Sweetcorn under the Influence of Exogenous Foliar Application of Iodine and Vanadium. Molecules 27, 1822. [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Macías J, Leija-Martínez P, González-Morales S, Juárez-Maldonado A, Benavides-Mendoza A. Use of Iodine to Biofortify and Promote Growth and Stress Tolerance in Crops. Front Plant Sci. 2016 Aug 23;7:1146. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adam Radkowski, Iwona Radkowska (2018). Influence of foliar fertilization with amino acid preparations on morphological traits and seed yield of timothy, Plant Soil Environ., 64(5):209-213. [CrossRef]

- GOST EN 1236-2013. Fertilizers. Method for determining bulk density without compaction. Interstate Standard (GOST) Мoscow, Russia, p.7, 2013. Available online: https://files.stroyinf.ru/Data/563/56357.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Wolthuis, E. , Pruiksma, A. B., & Heerema, R. P. (1960). Determination of solubility: A laboratory experiment. Journal of Chemical Education, 37(3), 137. [CrossRef]

- Doszhanov E.O., Sabitov A.N., Mansurov Z.A., Doszhanov O.M., Zhandosov Zh.M., Rakhymzhan N. Method of obtaining sorbent from vegetable raw materials. Utility Model Patent No. 8681, 12/01/2023.

- M. Naderi, S. M. Naderi, S. Tarleton edition, “Surface Area: Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), ” Progress in Filtration and Separation, Academic Press, pp. 585-608, 2015. ISBN 9780123847461. [CrossRef]

- GОST 33618-2015. Activated carbon. Standard method for determination of iodine value. Interstate standard. Мoscow, Russia, p.8, 2016. Available online: https://files.stroyinf.ru/Data2/1/4293756/4293756365.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Sabitov Aitugan Nurbolatovich; Doszhanov Yerlan Ospanovich; Turganbai Seitzhan; Nurbolatuly Didar. RK patent for utility model No. 8791. A method for obtaining granular fertilizer based on pyrocarbon. IPC C05G 3/00 C05D 9/02. Published on 01/19/2024, Bulletin No. 3.

- GОST 31640-2012. Feeds. Methods for determination of dry matter content. Interstate standard. Мoscow, Russia, p. 11, 2012. Available online: https://files.stroyinf.ru/Data2/1/4293787/4293787414.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kharchenko, V. A., Moldovan, A. I., Golubkina, N. A., Gins, M. S., & Shafigullin, D. R. (2020). Comparative evaluation of several biologically active compounds content in Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. and Anthriscus cerefolium (L.) Hoffm. Vegetables of Russia, (5), 81-87. [CrossRef]

- N.A. Golubkina, H.G. N.A. Golubkina, H.G. Kekina, A.V. Molchanova, M.S. Antoshkina, S.M. Nadezhkin and A.V. Soldatenko (2020). Plant antioxidants and methods for their determination. Infra-M, vol. 1, p. 181. [CrossRef]

- Doszhanov, Y. , Atamanov, M., Jandosov, J., Saurykova, K., Bassygarayev, Z., Orazbayev, A.,... & Sabitov, A. (2024). Preparation of Granular Organic Iodine and Selenium Complex Fertilizer Based on Biochar for Biofortification of Parsley. Scientifica, 2024(1), 6601899. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, E. and Natarajan, S. (2007), XRD, thermal and FTIR studies on gel grown DL-Phenylalanine crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol., 42: 617-620. [CrossRef]

- Tomar, D. , Chaudhary, S., & Jena, K. C. (2019). Self-assembly of l-phenylalanine amino acid: electrostatic induced hindrance of fibril formation. RSC advances, 9(22), 12596-12605. [CrossRef]

- Max, J. J. , & Chapados, C. (2004). Infrared spectroscopy of acetone–water liquid mixtures. II. Molecular model. The Journal of chemical physics, 120(14), 6625-6641. [CrossRef]

- Tong, A. , Tang, X., Zhang, F., & Wang, B. (2020). Study on the shift of ultraviolet spectra in aqueous solution with variations of the solution concentration. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 234, 118259. [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, P. , Mohan, U., Borpuzari, M. P., Boruah, A., & Baruah, S. K. (2019). UV-Visible spectroscopy and density functional study of solvent effect on halogen bonded charge-transfer complex of 2-Chloropyridine and iodine monochloride. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 12(8), 4522-4532. [CrossRef]

- ChemicalBook. (2025). Dimethyl sulfoxide – Product chemical properties. Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com/ProductChemicalPropertiesCB9773699_EN.htm 22. (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Moon, C. Y., Kim, Y. S., Lee, E. C., Jin, Y. G., & Chang, K. J. (2002). Mechanism for oxidative etching in carbon nanotubes. Physical Review B, 65(15), 155401. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. , Teng, J., Ding, L., Tang, X., Huang, J., Liu, S.,... & Li, J. (2025). Establishing structure-property relationships grounded in oxidation strategy engineering to unravel the triggering mechanism of Na+ filling in Hard Carbon closed pore. Electrochimica Acta, 146970. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C. G., Everett, D. H., & Nuttall, S. (1989). Adsorption hysteresis in porous materials. Pure and Applied chemistry, 61(11), 1845-1852. [CrossRef]

- Halka, M. , Klimek-Chodacka, M., Smoleń, S., Baranski, R., Ledwożyw-Smoleń, I. and Sady, W. (2018), Organic iodine supply affects tomato plants differently than inorganic iodine. Physiol Plantarum, 164: 290-306. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Cao, H., Wang, M., Zou, Z., Zhou, P., Wang, X., & Jin, J. (2023). A review of iodine in plants with biofortification: Uptake, accumulation, transportation, function, and toxicity. Science of The Total Environment, 878, 163203. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y. , Chen, Y., Ma, C., Qin, J., Nguyen, T. H. N., Liu, D.,... & Luo, Z. B. (2018). Phenylalanine as a nitrogen source induces root growth and nitrogen-use efficiency in Populus× canescens. Tree physiology, 38(1), 66-82. [CrossRef]

- Grey, C.B. , Cowan, D.P., Langton, S.D. et al. (1997). Systemic Application of L-Phenylalanine Increases Plant Resistance to Vertebrate Herbivory. J Chem Ecol 23, 1463–1470. [CrossRef]

- Dobosy, P., Vetési, V., Sandil, S., Endrédi, A., Kröpfl, K., Óvári, M., ... & Záray, G. (2020). Effect of irrigation water containing iodine on plant physiological processes and elemental concentrations of cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivated in different soils. Agronomy, 10(5), 720. [CrossRef]

- Kiferle, C., Martinelli, M., Salzano, A. M., Gonzali, S., Beltrami, S., Salvadori, P. A., ... & Perata, P. (2021). Evidences for a nutritional role of iodine in plants. Frontiers in plant science, 12, 616868. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, H. , Cai, A., Wu, D., Liang, G., Xiao, J., Xu, M.,... & Zhang, W. (2021). Effects of biochar application on crop productivity, soil carbon sequestration, and global warming potential controlled by biochar C: N ratio and soil pH: A global meta-analysis. Soil and Tillage Research, 213, 105125. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. , Irshad, S., Mehmood, K., Hasnain, Z., Nawaz, M., Rais, A.,... & Ibrar, D. (2024). Biochar production and characteristics, its impacts on soil health, crop production, and yield enhancement: A review. Plants, 13(2), 166. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Wu, D., Liu, X., Huang, Y., Cai, A., Xu, H., ... & Zhang, W. (2024). A global dataset of biochar application effects on crop yield, soil properties, and greenhouse gas emissions. Scientific Data, 11(1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Ndede, E. O., Kurebito, S., Idowu, O., Tokunari, T., & Jindo, K. (2022). The potential of biochar to enhance the water retention properties of sandy agricultural soils. Agronomy, 12(2), 311. [CrossRef]

- Lustosa Carvalho, M. , Tuzzin de Moraes, M., Cerri, C. E. P., & Cherubin, M. R. (2020). Biochar amendment enhances water retention in a tropical sandy soil. Agriculture, 10(3), 62. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. , Kaushik, R., Pandit, M. K., & Lee, Y. H. (2025). Biochar-induced microbial shifts: advancing soil sustainability. Sustainability, 17(4), 1748. [CrossRef]

- Kracmarova-Farren, M. , Alexova, E., Kodatova, A., Mercl, F., Szakova, J., Tlustos, P.,... & Stiborova, H. (2024). Biochar-induced changes in soil microbial communities: a comparison of two feedstocks and pyrolysis temperatures. Environmental Microbiome, 19(1), 87. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F. L., Santos, J. M., Mota, J. C., Costa, M. C., Araujo, A. S., Garcia, K. G., ... & Pereira, A. P. D. A. (2024). Potential of biochar to restoration of microbial biomass and enzymatic activity in a highly degraded semiarid soil. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 26065. [CrossRef]

- Vanapalli, K. R. , Samal, B., Dubey, B. K., & Bhattacharya, J. (2021). Biochar for sustainable agriculture: prospects and implications. In Advances in chemical pollution, environmental management and protection (Vol. 7, pp. 221-262). Elsevier. ISSN 2468-9289, ISBN 9780128201787. [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M., Feizienė, D., Tilvikienė, V., Akhtar, K., Stulpinaitė, U., & Iqbal, R. (2021). Biochar role in the sustainability of agriculture and environment. Sustainability, 13(3), 1330. [CrossRef]

- Cezar, J. V. D. C. , Morais, E. G. D., Lima, J. D. S., Benevenute, P. A. N., & Guilherme, L. R. G. (2024). Iodine-enriched urea reduces volatilization and improves nitrogen uptake in maize plants. Nitrogen, 5(4), 891-902. [CrossRef]

- Smolen, S. , Sady, W., Rozek, S., Ledwozyw-Smolen, I., & Strzetelski, P. (2011). Preliminary evaluation of the influence of iodine and nitrogen fertilization on the effectiveness of iodine biofortification and mineral composition of carrot storage roots. Journal of Elementology, 16(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y-G., Huang, Y-Z., Hu, Y., & Liu, Y-X. (2003). Iodine uptake by spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) plants grown in solution culture: effects of iodine species and solution concentrations. Environment International, 29, 33-37.

- Tiyogi Nath, T. N. , Priyankar Raha, P. R., & Amitava Rakshit, A. R. (2010). 9: Sorption and desorption behaviour of iodine in alluvial soils of Varanasi, India, Agricultura 7, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby, O. A. (2025). Iodine application induces the antioxidant defense system, alleviates salt stress, reduces nitrate content, and increases the nutritional value of lettuce plants. Functional Plant Biology, 52(6). Jun;52:FP24273. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, B. , Rios, J.J., Cervilla, L.M., Sánchez-Rodrigez, E., Ruiz, J.M. and Romero, L. (2008), Iodine biofortification and antioxidant capacity of lettuce: potential benefits for cultivation and human health. Annals of Applied Biology, 152: 289-299. [CrossRef]

- Krzepiłko, A., Święciło, A., & Zych-Wężyk, I. (2021). The antioxidant properties and biological quality of radish seedlings biofortified with iodine. Agronomy, 11(10), 2011. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).