1. Introduction

Although there is a general agreement that physical activity and sports are a fundamental component of health and quality of life in modern societies, not all populations have equal access to them [

26]. People with disabilities constitute a significant proportion of global population, with 3.8 million men and women with disabilities in Spain, representing almost 9% of the national population [

17]. This group experiences disparities, including higher rates of health problems [

20], as well as lower use of preventive health services [

27]. The World Health Organization [

36] recognizes that health encompasses all aspects of a person's life experiences and is inherently multifactorial, arguing that disability should not be equated with illness and that people living with disabilities can enjoy good health and experience a high quality of life [

10].

The benefits associated of physical sporting activity have been explained on numerous occasions, as it contributes to strengthening the sense of belonging, promotes empathy, fosters mutual respect, and favors tolerance and the acceptance of established norms [

15], as well as improving the resilience participants [

7,

12,

13]. Similarly, as Campos et al. [

4] point out, the benefits impact not only the participants, but also the wider society involved. Beyond its recreational and competitive function, sport plays a fundamental role in overcoming social barriers, and has a significant social impact [

24]. Thus, its impact transcends the individual, becoming a transformative element of social and cultural dynamics [

11,

25]. Therefore, it plays a key role in the transforming identities, promoting a new vision of this concept and facilitating the empowerment of individuals, while preventing attitudes that perpetuate discrimination and exclusion [

8].

The importance of sports practice has also been recognised internationally and nationally through decisive legislative frameworks. At the international level, for example, the United Nations General Assembly, recognized the right of persons with disabilities to equal access to participation in games and recreational and sporting activities (Article 30) [

21]. At the national level, various references can be found, such as the former Sports Law [

19], which already established that sport is, among other things, a corrective factor for social imbalances, contributing to the development of equality among citizens and creating habits that facilitate social integration. Another reference is the "The White Paper on Sport for People with Disabilities" [

9], which highlights the important role of sports practice for persons with disabilities and emphasises the need for specific and inclusive groups. Therefore, sport for persons with disabilities has become a fundamental tool for promoting social inclusion and equal opportunities, as well as fostering the comprehensive development of society [

25].

Despite the wide variety of benefits mentioned and the support provided by existing legislative frameworks, significant shortcomings persist that hinder access to sports practice for people with disabilities [

33]. International literature on physical sporting activity highlights a number of barriers related to the presence of negative attitudes in the environment [

30], a lack of support from coaches and other professional profiles in the sports context [

33], participation in sports that are not appropriate for the type of disability of the practitioner, or the failure to modify of certain sports [

36], as well as the lack of training for professionals [

2]. Due to the lack of adequate infrastructure that addresses for access of persons with disabilities to sport, this has been addressed in the current Law [

3], of 30 December, on Sport, which plays a crucial role in recognizing this. The right of all persons to access the practice of physical activity and sport, with a specific mention of the promotion of inclusive sport, specifically in article 6.6, which states the duty of federations to promote the development of sports practice for persons with disabilities, including the holding of inclusive sports activities. The Law introduces specific measures to promote equal opportunities and gender equality, as well as the integration of athletes with disabilities into common organizational structures, such as sports federations. This reinforces the need for structural legislative changes in Spanish sport that support the real participation of persons with disabilities in the sports field. In this regard, scientific evidence identifies facilitators for the inclusion of persons with disabilities in sport, such as professional support [

14], adaptation of equipment [

36], and specific training [

23].

Although there are precedents for integration processes in other countries, there is a lack of consensus regarding the model or process that should be adopted to promote the integration of people with disabilities within the context of sports federations [30; 12; 19].

In Norway, the Olympic and Paralympic Committees have been integrated into a single entity alongside the Norwegian Sports Confederation, enabling full inclusion and coordinated governance [2; 30]. In Canada, legislation introduced in 2000 and 2006 has aimed to integrate sports federations and eliminate participation barriers. However, integration remains partial and largely symbolic, particularly within high-performance sports [

19,

30]. In the UK, most sports are under a single federation covering Olympic and Paralympic disciplines, while separate disability specific and multisport federations coexist, reflecting partial integration (30). In the Netherlands, the Olympic and Paralympic Committees and the Dutch Sports Federation have formed a single coordinated organization since 2008, promoting inclusive national sports governance [

30]. In the USA, the US Olympic Committee has incorporated the Paralympic athletes since 2012. The Critical Change Factors Model [

12] identifies the key factors required to transition from marginalization to legitimization within an inclusive sports paradigm.

Despite the existence of legislation and policies promoting the integration of sports for people with disabilities, few studies have examined how this integration occurs within the Spanish sports federations. Furthermore, the barriers and facilitators that influence the implementation of inclusive practices have yet to be documented, hindering the evidence-based decision-making in federations' sports policy. While [

24] work involved identifying existing models and developing an initial protocol based on a qualitative analysis conducted with stakeholders in the federative environment. However, this proposal was developed without considering the current legal framework.

Consequently, this study contributes to understanding the current situation of Spanish sports federations with regard to the integration and development of sports for people with disabilities. It also serves to further our understanding of the process of integration of sports for people with disabilities in Spanish single-sport federations, which are key agents in the promotion of sports for people with disabilities. According to the current Spanish Sports Law (39/2022), federations are essential platforms to promote the inclusion of people with disabilities through sports. The study hypothesizes that the level of integration of sports for people with disabilities varies among Spanish single-sport federations. The specific research questions are:

1. How are the Spanish national single-sport federations integrating sports for people with disabilities?

2. How do these integration initiatives align with international federative trends and Sports Law 39/2022?

Therefore, the present study aims to understand the current situation of Spanish sports federations in relation to the integration and development of sports for people with disabilities in Spain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The Spanish National Sports Council (CSD) [

5] recognizes a total of 66 Spanish sports federations, including those dedicated to sports for persons with disabilities. These are classified according to the four categories defined by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) [

18]: federations of Paralympic sports managed by International Federations (IFs) (sports that the IPC has transferred to International Federations and that have been integrated in Spain following international integration), sports disciplines created by IFs (these disciplines did not originally depend on the IPC, but International Federations have developed them specifically for persons with disabilities), Disability IFs (federations specialized in persons with disabilities that continue to manage and organize the corresponding sports independently), and sports directly managed by the IPC and National Paralympic Committees (NPCs) (disciplines where the IPC acts as the international federation responsible for overseeing them, in collaboration with national Paralympic committees).

The aim was to ensure that the methodological design provided a comprehensive representation of the federated sports landscape in Spain, taking into account the particularities and specificities of each federation. In order to provide a complete and representative overview of the national sports scene, the inclusion criteria for the sample were as follows:

1- Federations that met the following requirements were included:

Federations that were officially recognized by the CSD.

Federations that were operational during the study period, excluding those that were inactive or in the process of dissolution.

2- Spanish Sports Federations are considered to be organizations officially recognized by the CSD that regulate and manage all sports disciplines at the national level. They include Single-Sport National Federations (Federaciones Nacionales Unideportivas - FU) and specific federations for sports for persons with disabilities, as well as Multi-Sport Federations (Federaciones Multideportivas - MU).

3- All FUs were included, regardless of whether they organized sports for persons with disabilities in general, and Paralympic sports in particular, in order to reflect a comprehensive perspective of sport, including its inclusive aspect.

4- Likewise, federations of diverse nature were included, regardless of their size, number of affiliates, or relevance to ensure that the entire spectrum of federated sport in Spain was represented.

Each federation was prospected from the CSD official list. All the data extractions regarding inclusive sport was registered in an Excel document. The approach allowed to capture and analyze the whole information in the web federations.

2.2. Instruments

The information was gathered through a systematic survey of the various digital resources available and accessible on the official websites of the different sports federations in the first semester of 2023. Microsoft Excel v.16 was used to collect data and the subsequent analysis.

2.3. Procedure

An exploratory and descriptive cross-sectional study [

31] was conducted [

1], with the objective of understanding the current situation of the 61 Spanish Sports Federations with regard to the integration and the promotion of sport for people with disabilities. This study combined quantitative and qualitative data collection from public sources from all the Spanish sports federations, enabling a detailed analysis of the accessible information.

Data collection was carried out on January 3rd, 2023, and continued until March 7th, 2023, working Monday through Friday with a total of 61 single-sport federations, at a pace of approximately six federations per week, and reviewing around two federations per day. A series of predefined aspects were reviewed through the systematic surveying of digital resources found on the websites of various Spanish National Sports Federations (FU). More specifically, data collection began with the recording of the federation’s full name, acronym, and the sports and specific disciplines it encompasses and governs, respectively. Particular attention was given to identifying any disciplines directly related to sports for people with disabilities. Additionally, reference was made to the corresponding International Federation, given its potential implications for future integration processes.

Once the initial identification had been completed, a systematic, step-by-step review protocol was followed for each federation. First, an Excel template designed for this purpose was opened, which included all the predefined categories for data collection. Next, the official website of each federation was visited via the Spanish Sports Council’s (Consejo Superior de Deportes) portal.

The first step was to examine the organisational structure to see if it included any reference to sport for people with disabilities. Specifically, the organigram was checked for disability-related units, commissions, or committees, and for specific tabs or sections dedicated to adapted, Paralympic, or inclusive sports. Any such information found was systematically recorded in the Excel template, including a direct link to the relevant webpage.

The statutes were subsequently reviewed to verify whether sport for people with disabilities, adapted sport or inclusive sport was formally recognised. Where such references were found, the corresponding section and a direct link to the statutes were recorded. The same procedure was applied to the regulations to identify whether there were any specific regulations for disability sport or if they were integrated into the general regulatory framework.

Next, the website was searched for programmes, projects or initiatives related to sport for disabled people. If any were found, they were documented and the corresponding links were added to the template. Financial information was then examined by reviewing the federation’s annual reports, usually from the previous three years, to identify whether specific budget lines had been allocated to disability-related activities. If so, the amount and link were recorded.

Finally, the website was revisited to identify any news articles, graphics or audiovisual resources related to disability. These were also recorded in the Excel template. This systematic procedure was repeated for all 61 federations to ensure the consistency, comparability and completeness of the data in the Excel database.

The analysis phase was carried out between 7 March and 4 April 2023, during which the Excel information matrix was completed and the characteristics of each federation were examined. Each variable was then coded based on its nature. Categorical variables reflected the presence or absence of a feature (e.g. mention of inclusive sport, specialised personnel or a specific budget) and were coded as 'Yes' (1) or 'No' (0).

Numerical variables represented measurable quantities, such as the number of athletes with disabilities holding a licence. This approach enabled appropriate analysis according to the variable type.

It has to be point out that of the 61 sports federations studied, specific data were not found on the websites of 19 of them. For this reason, they are not included in the count of

Figure 2. Recording this limitation maintains the consistency of the results presented in the study and helps to explain why some federations in the data collection. The federations without accessible information are as follows: basketball (FEB), fencing (RFEE), football (RFEF), weightlifting (FEDEALTER), hockey (RFEH), swimming (RFEN), skating (RFEP), modern pentathlon (FEPM), volleyball (RFEVB), aeronautics (RFAE), billiards (RFEB), bowling (FEBOLOS), hunting (FECAZA), pigeon racing (REAFEDE), speleology (FEE), powerboating (RFEM), polo (RFPOLO), squash (RFES), and clay pigeon shooting (RFETAV).

Due to the lack of information regarding the situation of sports federations, and more specifically in relation to the integration of sports for people with disabilities, as highlighted by Hernández-Beltrán et al. [

16], attention was focused on the elements consistent across all federations. These elements are considered fundamental to the proper management and development of the sports they represent (see

Figure 1).

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and categorical coding were used in the present study. This included identifying the presence or absence of inclusive practices, comparing types of federations, and identifying elements related to sports for people with disabilities, among other things. The qualitative findings were summarised in narrative form to highlight trends or gaps, and the quantitative results were expressed as percentages or frequencies.

3. Results

The results of the present research demonstrate the level of integration and development of Spanish sports federations in relation to sport for persons with disabilities (see

Figure 2).

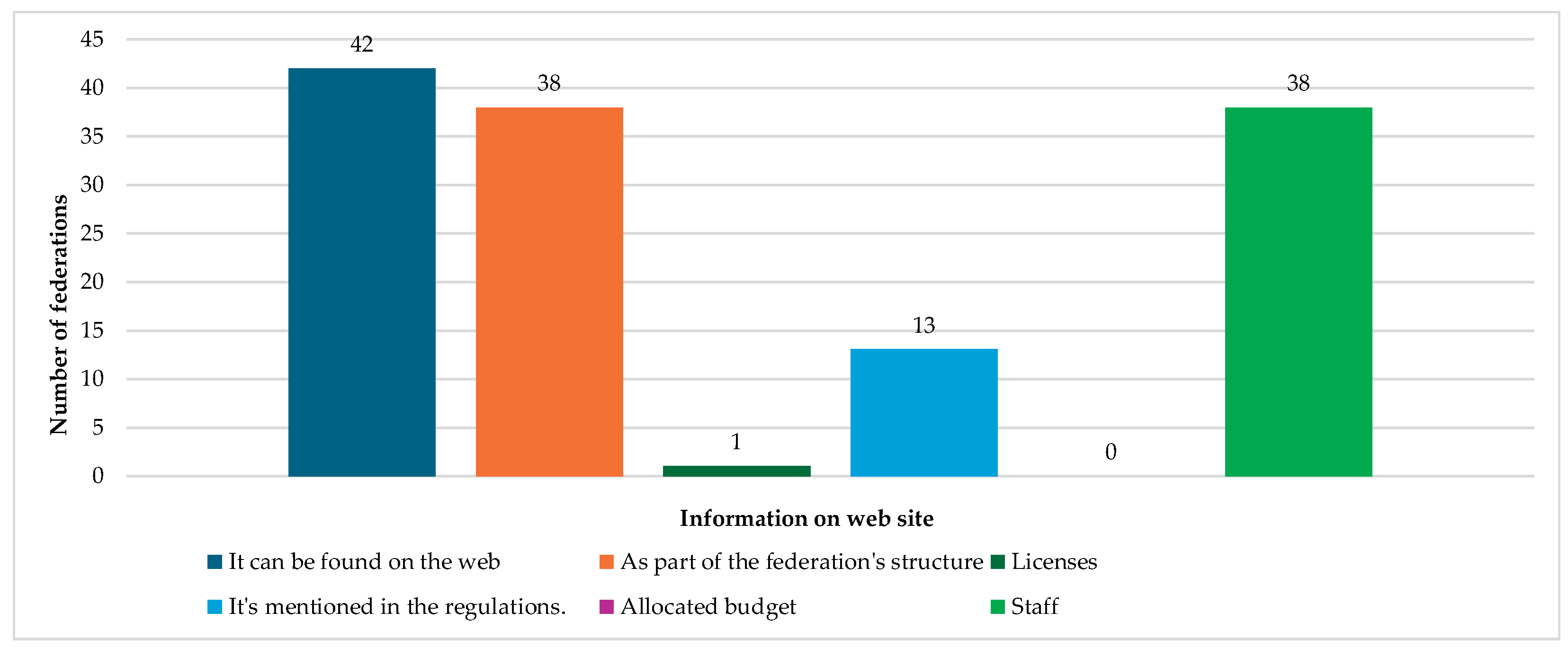

Figure 2.

Web content on sports for people with disabilities across different Spanish sports federations.

Figure 2.

Web content on sports for people with disabilities across different Spanish sports federations.

The analysis of the situation of Spanish Sports Federations in relation to the integration of sports for people with disabilities has yielded the information detailed below. Most federations have initiatives related to the integration of disabled people in sport: of the 61 sports federations, 21 have Paralympic categories. It is also observed that 42 of them present themselves as inclusive entities. In 38 cases, sports for people with disabilities form part of the structure; the cycling federation (RFEC) is the only one that discloses the number of licences held by athletes with disabilities. Thirteen of the federative regulations specifically address sports for people with disabilities or inclusive sports. None of the websites consulted provide information on the budgets allocated to athletes with disabilities. Specialised personnel related to sports for people with disabilities can be found in 38 cases. Nineteen of the 61 federations recognised by the CSD (Spanish National Sports Council), not counting the five federations for people with disabilities, do not present any digital content related to the subject of the study.

In other words, 42 of the federations have an online presence to varying degrees. In general, this includes information about their structure. The 38 federations that have assigned personnel have individuals ranging from representatives of the Adapted/Inclusive Sport committees or departments and the technical director of Adapted Sport to specialist technicians, classifiers, the technical coordinator, the head of medical services, the head of the refereeing area and the development director, as well as assistant personnel.

However, we found a lack of specific information about athletes with disabilities and their inclusion in the regulations, as well as a complete absence of information regarding specific budget allocations for adapted sports. There is room for improvement in terms of support and transparency regarding sports for people with disabilities within the sports federations. Knowing the number of licensed athletes with disabilities and accessing specific budgets for adapted and inclusive sports would provide greater insight into the impact of integration processes within each federation.

Among the results (see

Figure 2), it is found that a total of 61 studied SFs (Sports Federations), 69% of the federations (42) had established specific adapted or inclusive sports committees. This was largely motivated by the guidelines of the Law (Law 39/2022, of 30 December 30) and, in cases where integration processes for disability had already begun prior to this, it was the result of movements made in this regard by their international reference federations. In 62% (38) of the federations, adapted, Paralympic, or inclusive sports appeared in the federation's structure or they have specialized personnel. However, only a third 21% (13) of the sports federations' statutes or regulations mentioned sports for people with disabilities. Meanwhile, specific adapted, Paralympic or inclusive sports programmes have been identified in 54% (34) of the federations, according to the projects presented on their websites.

4. Discussion

This study aims to understand the current situation of Spanish sports federations regarding the integration and development of sports for people with disabilities in Spain. Despite precedents in other countries, there is no consensus on the most effective way to integrate disabled people into sports federations [30; 12; 19]. Furthermore, despite supportive policies existing, few studies have examined the implementation of sports integration for disabled people within Spanish sports federations. The only study to date to address this issue was carried out by Martinez-Ferrer (2016), who developed a protocol through qualitative analysis of stakeholders in sports federations. However, this proposal was created without considering the current legal framework. Thus, the present study addresses this knowledge gap by providing data to guide federations in enhancing inclusion and promoting equitable participation in sport. The results obtained are discussed below, highlighting the individual situation of each Spanish federation and revealing that not all implement actions regarding the integration of sports modalities for people with disabilities.

The results of the present study indicate that, despite legal frameworks and institutional guidelines, visibility, accountability and data availability regarding sport for people with disabilities remain limited. The study findings show that the integration of people with disabilities into Spanish sports federations is partial and uneven, with some areas in need of improvement, such as resource allocation and inclusion policies. This study highlights the need for sports federations to increase transparency, collect and report accurate data on participation in adapted sports, and implement inclusion measures to ensure effective integration processes.

In this instance, 42 of the national federations are carrying out actions related to the integration of sports for people with disabilities. The Cycling Federation is leading the list with the most and best initiatives, followed by the Triathlon, Judo, Canoeing, Table Tennis, Archery and Sailing Federations, and then the Karate Federation. Analysis of the results reveals existing actions, such as the creation of Sports Commissions for People with Disabilities (Article 46.5 of the Sports Law), representatives of sports for people with disabilities appearing in the federative organisational chart (Articles 6.4 and 47.3), and the integration of specific sports modalities of the different sports (Article 6.3). Some federations have launched specific programmes for sports development (Article 5.4) and for technical personnel (Article 38.4), taking advantage of public administration funding (Article 6.8) through subsidies from the National Sports Council. These programmes ensure the quality of their intervention when working with athletes with disabilities. Of all the federations, 42 have initiated integration-related activities, while 19 federations do not present any such activities on their digital platforms. Key strategies identified include creating Inclusive Sport Commissions, integrating representatives of sports for people with disabilities into the board structure, and developing specific adapted or Paralympic sports programmes. For example, the Cycling Federation reports on the number of athlete licences held by disabled people, and federations such as Triathlon, Judo, Table Tennis, Canoeing, Archery and Karate demonstrate the active implementation of inclusion initiatives.

Nevertheless, significant gaps remain. Only 14 federations include explicit references to sports for people with disabilities in their statutes or regulations, and none provide information on the budget allocated to these sports. These findings suggest that, although integration initiatives exist, they are limited in terms of content and transparency. The presence of specialised personnel in sports for people with disabilities was identified as a facilitating factor in 38 federations, while the lack of accessible data on athletes and budgets reflects an incomplete integration process.

In contrast, federations that have started to integrate people with disabilities into their structures are usually in line with Sports Law 39/2022, especially Article 6, which promotes the inclusion of people with disabilities within the federative structure and the establishment of a federative commission dedicated to this goal. A clear example of this is the initiatives proposed by the Spanish Karate Federation, which has promoted the integration of para-karate within the framework of specific aid from the National Sports Council. It is worth noting that legislation has sometimes promoted the modification of federation statutes or regulations, and it is through updating these that structural changes affecting the guidelines of different national sports federations have occurred, as has happened with the Sailing and Archery federations. Some federations have launched specific programmes for sports development (Article 5.4) and for technical personnel (Article 38.4), taking advantage of public administration funding (Article 6.8) and subsidies from the National Sports Council. These programmes ensure the quality of their work with athletes with disabilities.

Nevertheless, significant gaps remain. The creation of Inclusive Sports Commissions reflects international trends where federations establish governance structures to promote sport for people with disabilities and inclusive sport, following the recommendations of international sports federations. However, implementation is sometimes inconsistent, as some commissions exist nominally but without functional responsibilities, indicating superficial alignment with mandatory legislation rather than real and comprehensive integration.

According to the results obtained, the elements for which hardly any information is available on the digital platforms of the different federations are:: i) the budget dedicated to sports for people with disabilities and/or inclusive sports (no federation shows this information); ii) the number of licenses held by athletes with disabilities (only the Cycling federation reports on this on its platform), iii) the lack of mention of sports for people with disabilities in the regulations or federative rules (it is only mentioned in 14 of the 61 federations). The establishment of numerous Inclusive Sports Commissions in many federations may have been influenced by the availability of subsidies. In recent years, the National Sports Council has presented a comprehensive aid proposal Inclusive Sports, derived from the Inclusive Sports Master Plan [

5]. This aid is intended to facilitate the integration of sports for people with disabilities into federations, develop specialized training, organize inclusive competitions, promote and disseminate sports for people with disabilities, hire specific personnel, and identify talent and develop disabled athletes before they turn professional— serving as a facilitating element for legal compliance.

However, in many cases, the establishment of these commissions has not resulted in them being given the function for which they were created. Many federations have these commissions only in name, having not yet provided them with content or real work. Despite compliance with the updated Article 49 of the Spanish Constitution [

6], the application of Article 30 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [

21], and support from the Sustainable Development Goals [

33], there was no prior legislative reference requiring single-sport federations to meet any of these requirements. Therefore, cases in which some federations have spearheaded and led their own initiatives with a specific idea of sports inclusion have been more due to philosophical issues and a sense of responsibility in their capacity to improve the quality of life of people with disabilities than to any mandatory nature. In recent years, various actions have been carried out to integrate sports for people with disabilities, with varied results depending on the tradition and presence of these sports in the Paralympic Games, or on the need for financial support, the provision of resources, coordination between administrations and federations, and the training of professionals in specific aspects of sports for people with disabilities, all of which are key elements for success in federative integration [

9].

The level of integration varies among the federations depending on different variables, such as inclusive sports activities, information in the statutes or regulations, a specific budget and the availability of specialised personnel. Consequently, federations with higher levels of these facilitating factors are expected to be at a more advanced phase of integration.

The findings support the hypothesis that federations with higher levels of facilitating factors achieve more advanced integration. Federations that provide specialised personnel (trained in disability issues related to sport), integrate sport for people with disabilities into their organisational structures, and implement specific programmes demonstrate more consistent and visible integration efforts. By contrast, federations lacking these factors tend to show minimal or no integration, with no evidence of trained personnel or budget.

For example, federations with active inclusive programs and specialized personnel, as Cycling, Karate or Triathlon, show advanced integration stages, whereas those federations with limited visibility of resources, remain in the initial stages. The presence of the facilitating factors and integration progress confirms de value of the hypotheses.

The complexity and challenges surrounding federative integration processes in sport are not without difficulty. This coincides with Rimmer's contribution that the lack of legislation on federative integration is one of the weak points preventing its achievement. In this sense, the current Sports Law aims to guarantee the mandatory nature of integration processes for the different state sports federations, outlining the steps to achieve this. However, the mere existence of this legislation is insufficient for this to be achieved, as Ocete [

22] states that strategies should aim to create inclusive sports environments that allow people with disabilities to choose the sport and level at which they wish to participate, independently of their location, age, or gender.

Also, [

28] acknowledged the necessity of enhancing community inclusion within sports clubs. Furthermore, strategies are needed to motivate people with disabilities to participate in sports activities, ensure their continued participation, and facilitate their progression in sports. While the identified indicators have provided clear information on organisations carrying out disability integration, they have been insufficient as they only offer information from the sports federations' websites. A more specific study of each federative entity is therefore necessary. Likewise, five of the federations currently depend on other organisations for specific disciplines for people with disabilities, despite these being adapted modalities of the same sport. Examples include wheelchair basketball, fencing, powerlifting, swimming and sitting volleyball. Therefore, when investigating single-sport federations, no information has appeared in this regard. Therefore, we agree with Hernández-Beltrán et al. [

16] that it is necessary to continue investigating this topic to understand trends in federated sports, and more specifically, sports for people with disabilities within sports federations.

Managerial implications

The results of this research could have a direct transfer to other national and international federations, providing a framework for an inclusion proposal. The findings could serve as a guide to help sports federations that have not yet taken the step to lay the groundwork for an inclusion proposal, based on real-world examples that have already been implemented, and could facilitate those that have begun the integration process. Listed below are a series of proposed practical applications that could help integrate people with disabilities into sports, through sports federations, ensuring compliance with current legislation:

1- Create a training proposal for the main stakeholders of sports federations on disability, focusing on the effective integration of people with disabilities into the specific sports of each federation.

2- Review and update the statutes and regulations of sports federations to include specific provisions related to the inclusion of people with disabilities, establish policies and procedures for the integration of athletes, and gather any effective guidelines to advance towards real integration within the federations.

3- Allocate a specific budget to developing adapted sports modalities, acquiring specific adapted equipment if necessary, and improving accessibility to any sports facilities dependent on or linked to the federation.

4- Create and/or activate inclusive Sports Committees and allow people with disabilities to be included on the boards or committees of the federations to comply with current regulations regarding representation on governing bodies, as mandated by law.5- Organize and develop initiatives, events, and activities to promote inclusive and adapted sports within the framework of each federation."