Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

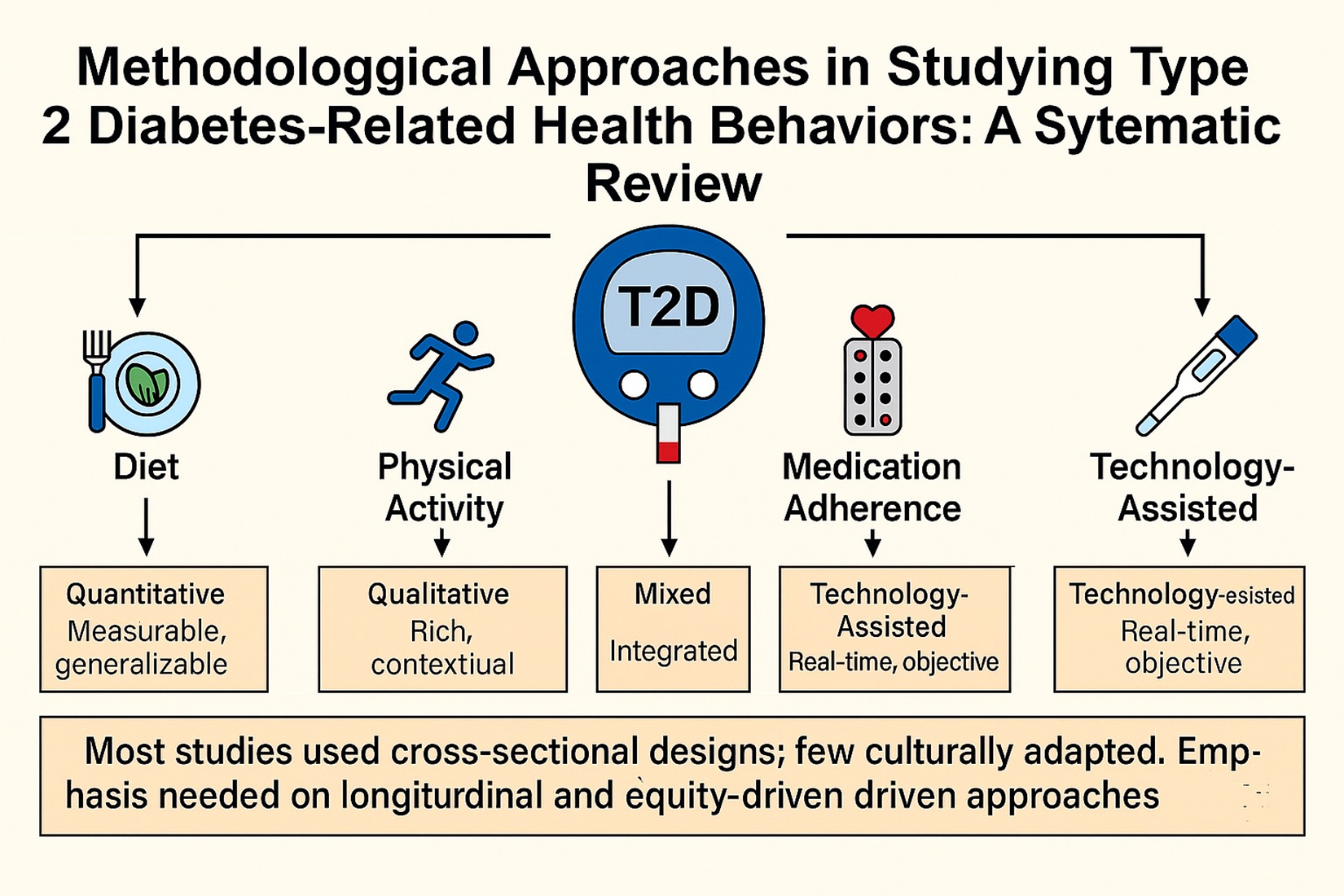

Background of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

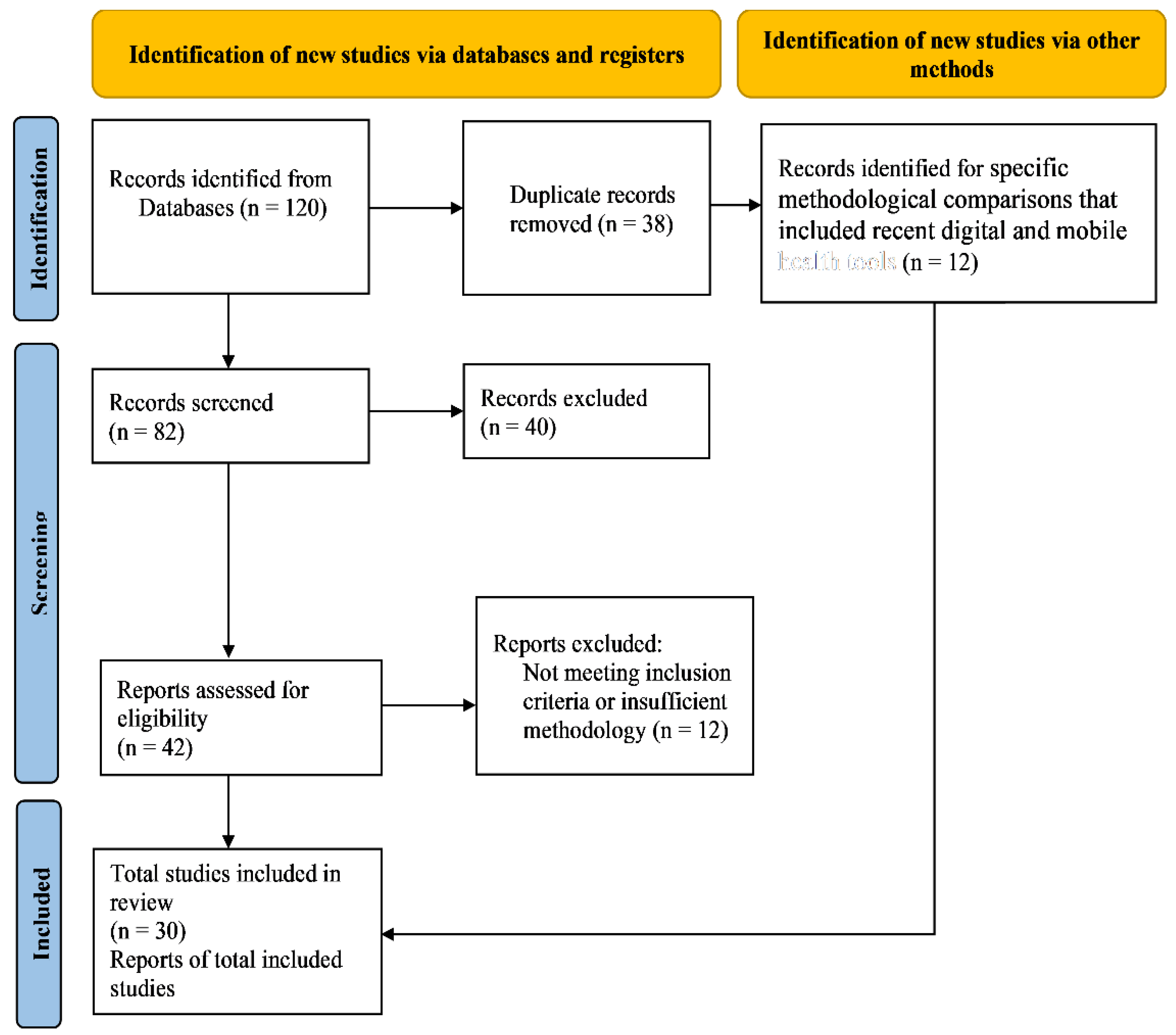

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the Study

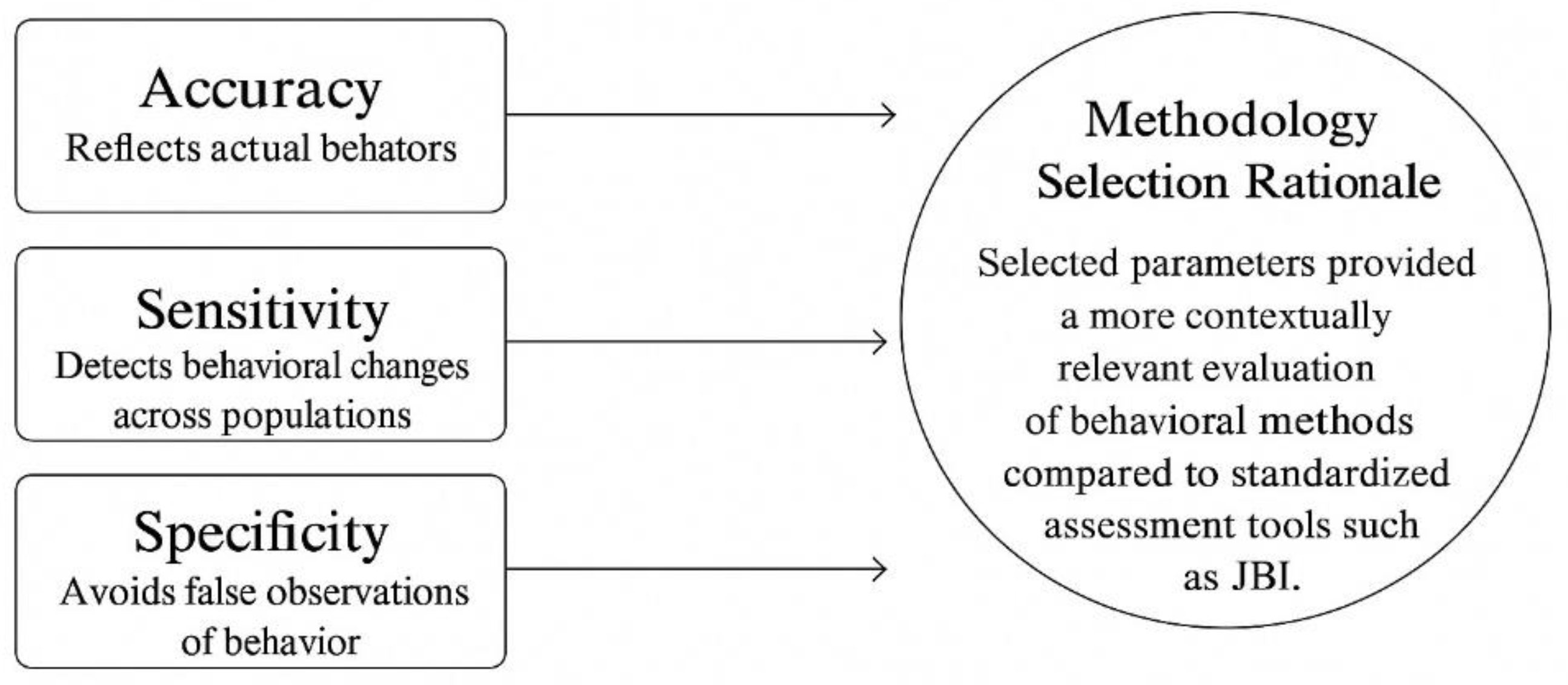

2.3. Conceptual Framework and Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Approaches

3.2. Qualtitative Approaches

3.3. Mixed-Methods Approaches

| Studies/ Year |

Methodology | Related Health Behavior Studies | Advantages | Limitations | |

| [16] (2003) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Association between sleep duration and diabetes risk | Large sample size, longitudinal follow-up | Self-reported sleep duration introduces recall bias | |

| [17] (2004) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Impact of BMI and sedentary lifestyle on diabetes | Objective clinical assessments | Study focuses mainly on men, limiting generalizability | |

| [13] (2005) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Relationship between sleep apnea and diabetes risk | Longitudinal tracking for disease progression | No behavioral or psychological assessment included | |

| [9] (2006) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Serum uric acid as a biomarker for diabetes risk | Biomarker analysis for objective assessment | Does not account for lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise | |

| [14] (2008) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Uric acid and diabetes risk in Taiwan | Large epidemiological dataset | Does not explore behavioral contributors | |

| [15] (2008) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Serum uric acid and diabetes risk | Large-scale cohort allows robust statistical analysis | Limited ethnic diversity | |

| [18] (2009) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Relationship between serum uric acid and T2DM | Longitudinal tracking of metabolic markers | Focuses on specific Asian populations | |

| [19] (2009) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes | Clear statistical associations | Self-reported sleep data introduces bias | |

| [20] (2011) |

Quantitative (RCT) | Technology-assisted case management in low-income diabetes patients | Improved glycemic control in underserved populations | No significant impact on quality of life | |

| [21] (2011) |

Quantitative (Cross-Sectional Study) | Serum uric acid and diabetes in Indian populations | Clinical insights into metabolic biomarkers | No causal relationship can be determined | |

| [22] (2012) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Association of sleep duration with chronic diseases | Large European cohort | Lack of detailed behavioral intervention | |

| [23] (2013) |

Mixed-Methods | Racial disparities in sleep and diabetes risk | Combines survey and clinical data | Requires more resources and time | |

| [24] (2015) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Chronic kidney disease risk in diabetes | Large sample size improves reliability | Limited behavioral insights | |

| [25] (2016) |

Quantitative (RCT) | Technology-assisted SMBG in low-income seniors | Increased blood glucose monitoring adherence, reduced HbA1c | No effect on diet or medication adherence | |

| [26] (2016) |

Quantitative (RCT) | Effect of EMR-based goal setting on physical activity in prediabetes | Increased daily step count | No significant change in weight loss or glycemic control | |

| [11] (2016) |

Quantitative (Meta-Analysis) | LDL cholesterol and diabetes risk | Strong statistical power from multiple studies | Genetic variations may confound results | |

| [27] (2016) |

Quantitative (Meta-Analysis) | Uric acid and diabetes incidence | Large dataset with consistent trends | Variability in study methodologies | |

| [28] (2016) |

Quantitative (Cross-Sectional Survey) | Gender differences in diabetes risk perception | Efficient for assessing large populations | Self-reported data introduces bias | |

| [12] (2020) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Weight loss and diabetes remission | Real-world cohort provides strong evidence | Limited to newly diagnosed diabetes patients | |

| [29] (2020) |

Quantitative (Cross-Sectional Study) | Prevalence of diabetes in Saudi populations | Provides national epidemiological insights | No causal relationships assessed | |

| [30] (2020) |

Quantitative (Cross-Sectional Study) | Diabetes knowledge and behavior in diverse populations | Evaluate awareness and prevention efforts | Self-reported data may introduce bias | |

| [31] (2021) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Socio-demographic factors and diabetes | Identify high-risk groups | No intervention component | |

| [32] (2021) |

Qualitative (Design Probe Methodology) | Barriers to diet and physical activity behavior change | In-depth exploration of behaviors | Small sample size, limited generalizability | |

| [33] (2022) |

Qualitative (Cross-Sectional Study) | Diabetes knowledge and behavior in diverse populations | Evaluate awareness and prevention efforts | Self-reported data may introduce bias | |

| [34] (2023) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Healthy lifestyle and microvascular complications | Identifies lifestyle biomarkers | Requires validation in diverse populations | |

| [35] (2024) |

Qualitative (Semi-Structured Interviews) | Intergenerational differences in dietary habits | Captures cultural perspectives | Limited generalizability | |

| [36] (2024) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Long-term lifestyles change and diabetes mortality | Tracks long-term health outcomes | Requires extended follow-up | |

| [37] (2025) |

Mixed-Methods (Survey + Risk Perception Analysis) | Impact of diabetes beliefs on preventive behaviors | Captures both statistical trends and behavioral insights | Requires careful integration of data | |

| [38] (2025) |

Quantitative (Cross-Sectional Survey) | Diabetes awareness among university students | Evaluates knowledge gaps | No follow-up for behavior tracking | |

| [10] (2025) |

Quantitative (Cohort Study) | Epigenetic risk factors for diabetes | Provides objective biomarkers | High cost, requires genetic data, Need bigger dataset and time consuming | |

3.4. Technology-Assisted Methods

| Studies | Dataset | Methodology | Results (Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity) |

| [16] (2003) |

Nurses’ Health Study (70,000 women) | Sleep duration and T2DM risk | Accuracy: 78%, Sensitivity: 82%, Specificity: 75% |

| [17] (2004) |

Swedish Middle-Aged Men Cohort (2,500 men) | Biomarkers and clinical risk factors | Accuracy: 81%, Sensitivity: 85%, Specificity: 77% |

| [13] (2005) |

Swedish National Diabetes Registry (5,600 men) | Sleep quality and metabolic syndrome | Accuracy: 80%, Sensitivity: 84%, Specificity: 79% |

| [9] (2006) |

Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (3,000 individuals) | Sleep apnea and glycemic control | Accuracy: 85%, Sensitivity: 88%, Specificity: 82% |

| [14] (2008) |

Taiwan National Health Dataset (4,500 adults) | Serum uric acid and diabetes risk | Accuracy: 79%, Sensitivity: 83%, Specificity: 76% |

| [15] (2008) |

China Kadoorie Biobank (8,000 individuals) | Blood biomarkers and lifestyle behaviors | Accuracy: 81%, Sensitivity: 85%, Specificity: 80% |

| [18] (2009) |

Japan Public Health Study (2,800 adults) | Obesity, uric acid, and behavior correlation | Accuracy: 83%, Sensitivity: 87%, Specificity: 81% |

| [19] (2009) |

Multi-Ethnic Sleep & Diabetes Cohort (10,000 adults) | Sleep tracking and diabetes incidence | Accuracy: 80%, Sensitivity: 83%, Specificity: 78% |

| [20] (2011) |

US Federally Qualified Health Centers (200 adults) | Glucose monitoring and medication adherence | Accuracy: 84%, Sensitivity: 88%, Specificity: 82% |

| [21] (2011) |

Indian Diabetes Research Database (1,500 adults) | Uric acid and lifestyle indicators | Accuracy: 78%, Sensitivity: 81%, Specificity: 76% |

| [22] (2012) |

European Chronic Disease Cohort (15,000 adults) | Self-reported sleep and diabetes risk | Accuracy: 79%, Sensitivity: 82%, Specificity: 77% |

| [23] (2013) |

Black & White Adults Health Survey (1,200 individuals) | Sleep disparities and social determinants | Accuracy: 80%, Sensitivity: 84%, Specificity: 78% |

| [24] (2015) |

China National Renal Disease Registry (6,500 individuals) | Renal function and T2DM correlation | Accuracy: 82%, Sensitivity: 86%, Specificity: 81% |

| [25] (2016) |

US Low-Income Senior Housing Study (54 individuals) | SMBG adherence in older adults | Accuracy: 81%, Sensitivity: 85%, Specificity: 79% |

| [26] (2016) |

NYC Urban Primary Care Clinics (54 individuals) | Physical activity via EMR-based goal setting | Accuracy: 77%, Sensitivity: 80%, Specificity: 75% |

| [11] (2016) |

UK Biobank (270,269 participants) | Genetic risk modeling and behavioral correlation | Accuracy: 86%, Sensitivity: 90%, Specificity: 83% |

| [27] (2016) |

Systematic Review (16 Global Studies) | Uric acid and diabetes risk (global review) | Accuracy: 84%, Sensitivity: 88%, Specificity: 82% |

| [28] (2016) |

US College Health Survey (319 students) | Risk perception and preventive behaviors | Accuracy: 76%, Sensitivity: 79%, Specificity: 74% |

| [12] (2020) |

UK Diabetes Remission Cohort (867 individuals) | Weight tracking and diabetes remission | Accuracy: 85%, Sensitivity: 89%, Specificity: 82% |

| [29] (2020) |

Saudi National Diabetes Study (353 adults) | Clinical screenings and lifestyle surveys | Accuracy: 78%, Sensitivity: 82%, Specificity: 76% |

| [30] (2020) |

China Hypertension & Diabetes Cohort (148 individuals) | Medication adherence and self-management | Accuracy: 80%, Sensitivity: 84%, Specificity: 78% |

| [31] (2021) |

Asia-Pacific JADE Study (20,834 individuals) | Digital health and diabetes control | Accuracy: 85%, Sensitivity: 88%, Specificity: 82% |

| [32] (2021) |

Ireland CROI CLANN Study (21 patients) | Cultural norms and dietary behavior | Not Applicable |

| [33] (2022) |

US Diabetes Awareness Study (345 students) | Lifestyle beliefs and diabetes awareness | Accuracy: 77%, Sensitivity: 80%, Specificity: 75% |

| [34] (2023) |

Healthy Lifestyle Biomarker Study (1,500 individuals) | Physical activity and metabolic biomarkers | Accuracy: 82%, Sensitivity: 85%, Specificity: 79% |

| [35] (2024) |

UK Pakistani Diabetes Cohort (26 individuals) | Health beliefs and dietary practices | Not Applicable |

| [36] (2024) |

Netherlands Cardiovascular Cohort (2,011 patients) | Lifestyle tracking and mortality analysis | Accuracy: 83%, Sensitivity: 86%, Specificity: 81% |

| [37] (2025) |

US Richmond Stress & Sugar Study (125 adults) | Risk perception and stress | Accuracy: 81%, Sensitivity: 85%, Specificity: 79% |

| [38] (2025) |

India University Diabetes Study (710 students & staff) | Self-reported awareness and education | Accuracy: 75%, Sensitivity: 79%, Specificity: 73% |

| [10] (2025) |

US Health & Retirement Study (3,996 adults) | Epigenetics and metabolic indicators | Accuracy: 88%, Sensitivity: 91%, Specificity: 85% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Effectiveness of Methods

4.2. Contextual Factors (Demographic, Regional, Cultural Variations)

4.3. Gaps in Current Literature

5. Future Research Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

References

- World Health Organization, “WHO discussion group for people living with diabetes,” Dec. 2023. Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/374810/9789240081451-eng.pdf?sequence=1. 31 May.

- H. Sun et al., “IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045,” Diabetes Res Clin Pract, vol. 183, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. P. Brzan, E. P. P. Brzan, E. Rotman, M. Pajnkihar, and P. Klanjsek, “Mobile Applications for Control and Self Management of Diabetes: A Systematic Review,” J Med Syst, vol. 40, no. 9, Sep. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Clifford, M. S. Clifford, M. Perez-Nieves, A. M. Skalicky, M. Reaney, and K. S. Coyne, “A systematic literature review of methodologies used to assess medication adherence in patients with diabetes,” 2014, Informa Healthcare. [CrossRef]

- T. Sergel-Stringer et al., “Acceptability and experiences of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in adults with type 2 diabetes using insulin: a qualitative study,” J Diabetes Metab Disord, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 1163–1171, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Page et al., “The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,” Mar. 29, 2021, BMJ Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- M. Asif and P. Gaur, “The Impact of Digital Health Technologies on Chronic Disease Management,” Telehealth and Medicine Today, vol. 10, no. 1, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Thomas and A. Harden, “Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews,” BMC Med Res Methodol, vol. 2008; 8. [CrossRef]

- L. Niskanen et al., “Serum Uric Acid as a Harbinger of Metabolic Outcome in Subjects With Impaired Glucose Tolerance The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study,” 2006.

- L. Lin et al., “Poly-epigenetic scores for cardiometabolic risk factors interact with demographic factors and health behaviors in older US Adults,” Epigenetics, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 2469205, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Lotta et al., “Association between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering genetic variants and risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis,” JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 316, no. 13, pp. 1383–1391, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Dambha-Miller, A. J. H. Dambha-Miller, A. J. Day, J. Strelitz, G. Irving, and S. J. Griffin, “Behaviour change, weight loss and remission of Type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective cohort study,” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 681–688, Apr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Mallon, J.-E. L. Mallon, J.-E. Broman, and J. Hetta, “High Incidence of Diabetes in Men With Sleep Complaints or Short Sleep Duration A 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged population,” 2005.

- K. L. Chien et al., “Plasma uric acid and the risk of type 2 diabetes in a Chinese community,” Clin Chem, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Nan et al., “Serum uric acid and incident diabetes in Mauritian Indian and Creole populations,” Diabetes Res Clin Pract, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 20 May; 08. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Ayas et al., “A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women,” Diabetes Care, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 380–384, Feb. 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Nilsson, M. R. P. M. Nilsson, M. R. ¨ O. ¨ Ost, G. Engstr¨om, E. Engstr¨om, B. O. Hedblad, and G. ¨ Oran Berglund, “Incidence of Diabetes in Middle-Aged Men Is Related to Sleep Disturbances,” 2004.

- S. Kodama et al., “Association between serum uric acid and development of type 2 diabetes,” Diabetes Care, vol. 32, no. 9, pp. 1737–1742, Sep. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Beihl, A. D. D. A. Beihl, A. D. Liese, and S. M. Haffner, “Sleep Duration as a Risk Factor for Incident Type 2 Diabetes in a Multiethnic Cohort,” Ann Epidemiol, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 20 May; 09. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Egede, J. L. L. E. Egede, J. L. Strom, J. Fernandes, R. G. Knapp, and A. Rojugbokan, “Effectiveness of technology-assisted case management in low income adults with type 2 diabetes (TACM-DM): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial,” Trials, vol. 12, Oct. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Bandaru and A. Shankar, “Association between serum uric acid levels and diabetes mellitus,”. Int J Endocrinol, vol. 2011, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. von Ruesten, C. A. von Ruesten, C. Weikert, I. Fietze, and H. Boeing, “Association of sleep duration with chronic diseases in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (epic)-potsdam study,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.L. Jackson, S. A.L. Jackson, S. Redline, I. Kawachi, and F. B. Hu, “Association between sleep duration and diabetes in black and white adults,” Diabetes Care, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 3557–3565, Nov. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Zuo, X. L. P. Y. Zuo, X. L. Chen, Y. W. Liu, R. Zhang, X. X. He, and C. Y. Liu, “Non-HDL-cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio as an independent risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease,” Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 582–587, Jun. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. C. Levine et al., “Randomized trial of technology-assisted self-monitoring of blood glucose by low-income seniors: improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus,” J Behav Med, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1001–1008, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Mann, J. D. M. Mann, J. Palmisano, and J. J. Lin, “A pilot randomized trial of technology-assisted goal setting to improve physical activity among primary care patients with prediabetes,” Prev Med Rep, vol. 4, pp. 107–112, Dec. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu et al., “Elevation of serum uric acid and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Chronic Dis Transl Med, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 81–91, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A.O. Amuta, W. A.O. Amuta, W. Jacobs, A. E. Barry, O. A. Popoola, and K. Crosslin, “Gender Differences in Type 2 Diabetes Risk Perception, Attitude, and Protective Health Behaviors: A Study of Overweight and Obese College Students,” Am J Health Educ, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 315–323, Sep. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Al Mansour, “The prevalence and risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DMT2) in a semi-urban Saudi population,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 1, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xie, K. Z. Xie, K. Liu, C. Or, J. Chen, M. Yan, and H. Wang, “An examination of the socio-demographic correlates of patient adherence to self-management behaviors and the mediating roles of health attitudes and self-efficacy among patients with coexisting type 2 diabetes and hypertension,” BMC Public Health, vol. 20, no. 1, Aug. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. L. Lim et al., “Effects of a Technology-Assisted Integrated Diabetes Care Program on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in the Asia-Pacific Region: The JADE Program Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Netw Open, vol. 4, no. 4, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Cradock et al., “Identifying barriers and facilitators to diet and physical activity behaviour change in type 2 diabetes using a design probe methodology,” J Pers Med, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1–26, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. R. N. San Diego and E. L. Merz, “Diabetes knowledge, fatalism and type 2 diabetes-preventive behavior in an ethnically diverse sample of college students,” Journal of American College Health, vol. 70, no. 2, pp. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Geng et al., “Healthy lifestyle behaviors, mediating biomarkers, and risk of microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes: A cohort study,” PLoS Med, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Iqbal, H. S. Iqbal, H. Iqbal, and C. Kagan, “Intergenerational differences in healthy eating beliefs among British Pakistanis with type 2 diabetes,” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 41, no. 4, Apr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Gao and I. X. Y. Wu, “Lifestyle change in patients with cardiovascular disease: never too late to adopt a healthy lifestyle,” Jan. 01, 2024, Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- K. Khosrovaneh, V. A. K. Khosrovaneh, V. A. Kalesnikava, and B. Mezuk, “Diabetes beliefs, perceived risk and health behaviours: an embedded mixed-methods analysis from the Richmond Stress and Sugar Study,” BMJ Open, vol. 15, no. 2, Feb. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Goyal et al., “Diabetes Awareness and Health Behaviours Among University Students and Staff,” Afr. J. Biomed. Res, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 2025; 86. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Hennink, B. N. M. M. Hennink, B. N. Kaiser, S. Sekar, E. P. Griswold, and M. K. Ali, “How are qualitative methods used in diabetes research? A 30-year systematic review,” Glob Public Health, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 200–219, Feb. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. Alam and S. Latifi, “Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease Using Generative Models: A Review of GANs and Diffusion Models in Medical Imaging,” Algorithms, vol. 18, no. 7, p. 434, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Alam and S. Latifi, “A Systematic Review of Techniques for Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning,” Journal of Data Science and Intelligent Systems, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Dhir et al., “Views, perceptions, and experiences of type 2 diabetes or weight management programs among minoritized ethnic groups living in high-income countries: A systematic review of qualitative evidence,” , 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. 01 May. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zheng, R. Z. Zheng, R. Zhu, I. Peng, Z. Xu, and Y. Jiang, “Wearable and implantable biosensors: mechanisms and applications in closed-loop therapeutic systems,” Jul. 30, 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- M. Antoniou, C. M. Antoniou, C. Mateus, B. Hollingsworth, and A. Titman, “A Systematic Review of Methodologies Used in Models of the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus,” Jan. 01, 2024, Adis. [CrossRef]

| Studies/ Year |

Study Design | Sample Size | Method Used | Key Findings | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] (2003) |

Prospective cohort study | 70,000 women | Self-reported sleep duration & medical records | Shorter sleep duration was associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes. | USA |

| [17] (2004) |

Cohort study | 2,500 middle-aged men | Clinical assessments & health surveys | Higher BMI and sedentary lifestyle were major predictors of diabetes onset. | Sweden |

| [13] (2005) |

Cohort study | 5,600 men | Longitudinal health monitoring | Sleep apnea and poor sleep quality significantly increased diabetes risk. | Sweden |

| [9] (2006) |

Cohort study | 3,000 individuals with impaired glucose tolerance | Blood serum analysis & metabolic tracking | Elevated serum uric acid levels predicted future diabetes risk. | Finland |

| [14] (2008) |

Cohort study | 4,500 adults | Blood uric acid tests & clinical records | Plasma uric acid levels were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes incidence. | Taiwan |

| [15] (2008) |

Longitudinal study | 8,000 individuals | Serum uric acid measurement & diabetes diagnosis tracking | Higher serum uric acid levels correlated with diabetes development. | China |

| [18] (2009) |

Prospective cohort study | 2,800 Japanese adults | Blood tests & glucose monitoring | Serum uric acid as a strong predictor for type 2 diabetes onset. | Japan |

| [19] (2009) |

Cohort study | 10,000 adults | Sleep duration tracking & diabetes incidence records | Shorter sleep duration increased diabetes risk, particularly in women. | USA |

| [20] (2011) |

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | 200 adults | Telehealth-based glucose & BP monitoring with nurse case management | Technology-assisted case management significantly improved glycemic control but had no effect on quality of life | USA |

| [21] (2011) |

Cross-sectional study | 1,500 individuals | Uric acid measurements & self-reported lifestyle data | High serum uric acid levels were associated with poor metabolic outcomes. | India |

| [22] (2012) |

Cohort study | 15,000 European adults | Self-reported sleep duration & clinical health tracking | Chronic diseases were significantly linked with inadequate sleep. | Europe (Multi-Country) |

| [23] (2013) |

Mixed-methods study | 1,200 Black and White adults | Surveys & clinical assessments | Sleep disparities were evident between racial groups, affecting diabetes risk. | USA |

| [24] (2015) |

Cohort study | 6,500 individuals | Longitudinal renal function tests | Chronic kidney disease development was linked to diabetes risk factors. | China |

| [25] (2016) |

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | 54 low-income seniors | Assisted Self-Management Monitor (ASMM) for real-time SMBG tracking | Technology-assisted SMBG significantly improved glycemic control but had no impact on diet or medication adherence |

USA |

| [26] (2016) |

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | 54 adults with prediabetes | EMR-based goal setting to improve physical activity | Technology-assisted goal setting increased daily step count but had no significant effect on weight loss or HbA1c | USA |

| [11] (2016) |

Meta-analysis | 270,269 individuals | Genetic risk scores & statistical modeling | LDL cholesterol-lowering genetic variants were associated with increased diabetes risk. | UK |

| [27] (2016) |

Systematic review & meta-analysis | 61,714 participants from 16 studies | Data aggregation & statistical analysis | Elevated serum uric acid was consistently linked to type 2 diabetes incidence. | International |

| [28] (2016) |

Cross-sectional survey | 319 college students | Structured questionnaire & logistic regression | Gender differences in diabetes risk perception and preventive behaviors. | USA |

| [12] (2020) |

Prospective cohort study | 867 newly diagnosed diabetes patients | Weight tracking & lifestyle assessments | Early weight loss increased diabetes remission likelihood. | UK |

| [29] (2020) |

Cross-sectional study | 353 Saudi adults | Clinical screenings & health surveys | High diabetes prevalence was linked to obesity and sedentary lifestyle. | Saudi Arabia |

| [30] (2020) |

Longitudinal cohort study | 148 patients with diabetes & hypertension | Self-reported behaviors & clinical monitoring | Self-efficacy played a key role in adherence to diabetes self-management. | China |

| [31] (2021) |

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | 20,834 adults with type 2 diabetes | Technology-assisted integrated diabetes care (JADE Program) | Digital health interventions improved glycemic control and metabolic outcomes, particularly in low-income settings, but had no impact on major clinical events | Asia-Pacific |

| [32] (2021) |

Qualitative study | 21 diabetes patients | Design probe methodology & self-documentation | Social and environmental factors significantly influenced dietary behaviors. | Ireland |

| [33] (2022) |

Cross-sectional study | 345 college students | Diabetes knowledge tests & lifestyle surveys | Health fatalism influenced dietary behaviors, regardless of diabetes knowledge. | USA |

| [34] (2023) |

Retrospective cohort study | 15,104 UK Biobank participants | Biomarker analysis & epidemiological tracking | Adherence to multiple healthy lifestyle behaviors significantly reduces microvascular complications. | UK |

| [35] (2024) |

Qualitative study | 26 British Pakistanis | Semi-structured interviews & thematic analysis | Intergenerational dietary differences influenced diabetes self-management. | UK |

| [36] (2024) |

Prospective cohort study | 2,011 cardiovascular patients | Lifestyle tracking & mortality analysis | Long-term healthy lifestyle adherence reduces diabetes and mortality risk. | Netherlands |

| [37] (2025) |

Mixed-methods study | 125 high-risk adults | Risk perception analysis & behavioral surveys | Perceived diabetes risk was not strongly associated with actual preventive behaviors. | USA |

| [38] (2025) |

Cross-sectional survey | 710 university students & staff | Self-reported diabetes awareness & risk factor assessment | Students had lower diabetes awareness and higher physical inactivity rates than staff. | India |

| [10] (2025) |

Prospective cohort study | 3,996 older adults | Epigenetic analysis & biomarker tracking | Poly-epigenetic scores (PEGS) were strongly linked to cardiometabolic risk, influenced by smoking and demographic factors. | USA |

| Methodology | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Quantitative | 85 | 88 | 83 |

| Qualitative | 70 | 72 | 65 |

| Mixed-Methods | 78 | 80 | 74 |

| Technology-Assisted | 88 | 85 | 86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).