Introduction

After a decade living in the Vale of Winscombe in the Western Mendips without ever encountering breeding Spotted Flycatchers Muscicapa Striata, I assumed they had vanished locally, mirroring their disappearance from much of their former range across southwest England and the UK as a whole. Then, in 2024, I came upon a small breeding population in nearby woodland. That discovery transformed my assumptions and spurred me to look more closely in my ‘local patch’ through spring and summer 2025. To my surprise, I discovered multiple breeding sites. These findings suggest that, despite decades of decline, the Vale of Winscombe, and likely the wider western Mendips, serve as an important refuge for this vulnerable species, offering some hope for its recovery in the region.

Methods

Study Area Overview

The natural qualities of a place are inseparable from its setting. Before sharing my observations on Spotted Flycatchers, I’ll begin with an overview of the Vale of Winscombe - its landscapes, habitats, and the birdlife that thrives there. This broader picture helps show not only the relative richness of the area but also the potential it holds for wildlife.

Spotted Flycatcher Status

I also provide an overview of the Spotted Flycatcher’s ecology and conservation status. This background establishes the wider context for interpreting local observations and patterns.

Spotted Flycatcher Desk Records

I gathered historic records of Spotted Flycatchers in the Vale of Winscombe and surrounding areas from The Somerset Atlas of Breeding and Wintering Birds 2007–2012 (Ballance et al., 2014). I obtained additional information through consultation with the Somerset and Avon county bird recorders, Brian Gibbs and Rupert Higgins, respectively, as the Vale lies across both recording areas. I also searched for online records of breeding Spotted Flycatchers. I have excluded from this account casual records of birds that may have been on migration.

Spotted Flycatcher Field Survey

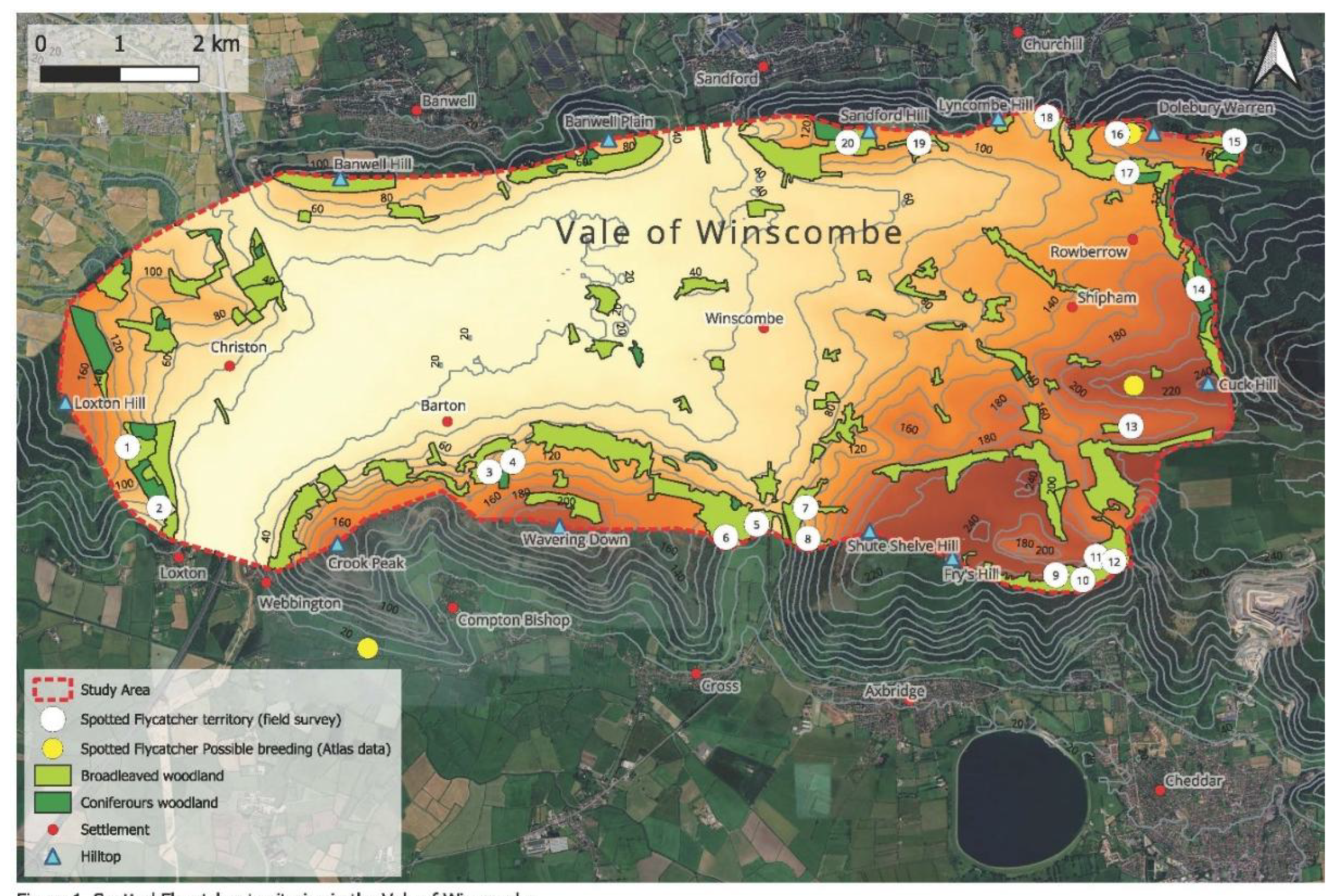

The Vale of Winscombe study area is shown in

Figure 1. The results presented here are not the outcome of a systematic survey of the entire Vale or of stratified random sampling. Instead, they reflect observations made during regular walks throughout spring and summer 2025, largely along public rights of way and across open access land. At times I deliberately visited sites I considered likely to hold Spotted Flycatchers, but my broader explorations provided coverage of the wide range of habitats present. Many locations were visited on multiple occasions.

Records of breeding Spotted Flycatchers were classified into three categories:

Confirmed. Family observed (pair with recently fledged young) and/or two or more registrations from the same location.

Probable. Pair observed in suitable breeding habitat.

Possible. Single bird observed or heard singing in suitable habitat.

Given the timing of the observations and the behaviour of the birds involved, none of the records were considered to relate to passage migrants.

Figure 1.

Spotted Flycatcher territoriese in the value of Winscomble.

Figure 1.

Spotted Flycatcher territoriese in the value of Winscomble.

Study Area Overview

The Mendip Hills divide naturally into western and eastern sections, with the transition marked less by a sharp boundary than by a gradual change in landscape character. For convenience, I take the line of the A39 between Wells and Chewton Mendip as a rough dividing point.

The western Mendips - most of which fall within the Mendip Hills National Landscape (formerly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) - are dominated by a broad, gently undulating plateau, occasionally cut by steep rocky gorges. To the west of Black Down and Rowberrow Forest, however, this plateau opens out dramatically into a wide, low-lying basin around 7.3 km long and 2.5 km across, known as the Vale of Winscombe (

Figure 1 &

Plate 1). Shirley Toulson, in

The Mendip Hills: A Threatened Landscape (1984), described it as

“one of the most pleasant and sheltered valleys of the Mendip.”

Today, the Vale is a patchwork of mixed farmland, recently planted orchards, and small scattered woodlands, framed by some of the Mendips’ most distinctive hills and ridgelines:

South. Crook Peak (191 m), Wavering Down (210 m), Shute Shelve Hill (233 m), and Fry’s Hill (230 m).

East. Dolebury Warren (182 m) and Cuck Hill (249 m).

North. Banwell Hill (119 m), Banwell Plain (96 m), Sandford Hill (132 m), and Lyncombe Hill (127 m).

West. Loxton Hill (176 m) (eastern section of Bleadon Hill).

The southern ridgelines are especially significant for their biodiversity. Crook Peak to Shute Shelve Hill forms part of the Mendip Limestone Grasslands Special Area of Conservation (SAC), while Cheddar Woods falls within the Mendip Woodlands SAC. Together with several Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), these protect a rich mix of calcareous grasslands, ancient and secondary semi-natural broadleaved woodland, and fragments of dry dwarf-shrub heath. Dolebury Warren, on the Vale’s northeastern edge, is itself designated a SSSI for its calcareous grassland and associated habitats. Several of these areas now also form part of the newly established Mendip National Nature Reserve (NNR), a large ‘super reserve’ linking key grassland and woodland sites from Brean Down to Wells.

For the purposes of this study, I have defined my study area broadly to match the Vale’s watershed, with slight extensions to include nearby records of Spotted Flycatchers. In total, this encompasses roughly 27 km², about 40% of which lies above 100 m elevation.

Birdlife of Vale of Winscombe

The hills that frame the Vale hold the greatest interest for birdlife. Their mosaic of scrub and extensively managed grasslands supports a diverse community of characteristic species, including Linnet (Red List & Species of Principal Importance [RL & SPI]), Garden Warbler, Willow Warbler (Amber List [AL]), Lesser Whitethroat, Whitethroat (AL), Skylark (RL), Meadow Pipit (AL), Tree Pipit (RL & SPI), and Stonechat. There is even a small but seemingly established population of Dartford Warblers (AL) on Crook Peak and Wavering Down.

Woodland around the Vale still holds a scattering of scarcer species. Small numbers of Marsh Tit (RL & SPI) remain, while I have occasionally encountered Redstart (AL) during the breeding season at the upper end of the Vale, particularly in the woods surrounding Dolebury Warren and the Perch. Somerset Wildlife Trust also reports Redstart from Rose Wood, and the species breeds more reliably just east of the Vale, around Charterhouse and Middledown.

Plate 1.

The Vale of Winscombe, with extensive cattle grazing on the southern slopes of Sandford Hill in the foreground. Wavering Down and Crook Peak are visible in the far distance. (Photo credit: Lincoln Garland).

Plate 1.

The Vale of Winscombe, with extensive cattle grazing on the southern slopes of Sandford Hill in the foreground. Wavering Down and Crook Peak are visible in the far distance. (Photo credit: Lincoln Garland).

The valley floor is less notable, yet its tree-lined, species-rich hedgerows provide important habitat for a range of common birds and seemingly healthy numbers of Bullfinch (AL & SPI) (Garland, 2020). Max Bog, a nationally important SSSI and a rare example of calcicolous lowland mire, adds another layer of diversity. Here, a few Reed Warblers and Reed Buntings (AL & SPI) appear to breed, and they may also occur along the Lox Yeo stream and drainage rhynes at the lower end of the Vale, where the landscape begins to resemble the adjoining Somerset Levels.

Among raptors, Peregrine Falcons (Schedule 1 [S1]) likely breed at three sites in surrounding quarries, while Barn Owls (S1) can be seen quartering hay meadows on the edge of Winscombe village. Red Kites (S1), though common elsewhere in Britain, have only recently established themselves in the western Mendips, but are now becoming a regular and welcome sight.

Yet, while the Vale’s birdlife appears rich, it is important to recognise the danger of shifting baseline syndrome or “pre-baseline amnesia” - the gradual acceptance of degraded ecosystems as the new norm (Tree, 2018). Looking back to Theodore Compton’s 1892 account of the Vale of Winscombe, the difference is striking. Species once recorded here included Cirl Bunting, Corncrake, Cuckoo, Lapwing, Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Nightingale, Nightjar, Red-backed Shrike, Redstart, Wryneck, and of course, the Spotted Flycatcher. The absence of nearly all these birds today underlines how easily ‘common’ can slip into ‘scarce’ if current national declines continue.

Finally, the southern ridgelines of Wavering Down and Crook Peak act as magnets for migrants in spring. Wheatears and Ring Ouzels still pass through in good numbers and both species historically bred in the Mendips. Breeding Wheatears remained common in the western Mendips until the early 20th century, while Ring Ouzels were reported breeding at the time near Priddy Mineries (Ballance, 2006). These seasonal movements offer a glimpse of the Vale’s former avian richness, and a reminder of how much has already been lost.

In this context, the discovery that Spotted Flycatchers continue to breed in the Vale is especially significant. Not only does it connect today’s landscape to its historical birdlife, but it also hints at the potential for recovery if the right conditions can be sustained.

Spotted Flycatcher – A Synopsis

The Spotted Flycatcher is one of only two Old World flycatchers to breed in the UK, the other being the similarly scarce Pied Flycatcher. Modest in appearance, it is a slim, grey-brown bird with a pale, streaked breast and crown, and is known for its distinctive fly-catching behaviour (

Plate 2). Late arrivals among our migrants, Spotted Flycatchers often do not reach the UK until late May or even June. Nesting usually takes place in exposed hollows, branch forks, or against walls and tree trunks, often screened by ivy, honeysuckle, or other climbing plants. Despite their late start, many pairs manage to rear two broods in a single season.

Conservation Status of the Spotted Flycatcher

I confess, I haven't always been obsessed with wildlife. If I were, I might have paid more attention as a child to the Spotted Flycatchers my mother tells me bred annually in our Worcestershire garden in the 1970s and early '80s. My old ID books confirm they were then still commonly encountered in urban parks, gardens, and the wider countryside. Looking further back in time to the early the twentieth century, A History of the Birds of Somerset documents numerous accounts highlighting their remarkable abundance in the region (Ballance, 2006). They were, for example, described as “almost colonial” near to Brent Knoll just southwest of the Vale of Winscombe.

But those days are long gone, and the statistics are stark. The Spotted Flycatcher has been on a steep downward trajectory since at least the mid-1960s, declining by 93% in the UK between 1967 and 2023, and is now rarely encountered (BTO, 2025). Consequently, the species is Red-listed as a Bird of Conservation Concern and designated a Species of Principal Importance under the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006.

Several factors underpin this decline:

Loss of insect prey. Widespread reductions in flying insect populations, driven by habitat degradation and agricultural intensification, have curtailed essential food supplies for adults and nestlings.

Pressures on migration and wintering grounds. Habitat loss and deteriorating conditions cause additional pressures during migration and wintering in sub-Saharan Africa; Spotted Flycatchers undertake journeys of up to 7,000 km to wintering areas as far south as Namibia (BTO, 2025).

Climate mismatch. Unlike many migrants, Spotted Flycatchers have not significantly advanced their arrival dates. As a result, they risk missing the seasonal peaks in insect abundance that now occur earlier due to climate change (Eden, 2025).

Spotted Flycatcher Results

Historical Records

The Somerset Atlas data contains no Confirmed or Probable Spotted Flycatcher breeding records from within the Vale of Winscombe. Three tetrads (2 × 2 km squares) are flagged as Possible breeding sites, though these also overlap areas outside of the Vale. Two of these lie on the eastern margins, covering Dolebury Warren and Rowberrow Warren, while the third covers woodlands near Compton Bishop and Webbington, just overlapping the Vale’s southwestern boundary. The nearest Confirmed breeding records are 1–2 km to the southeast, in the vicinity of Black Down and Cheddar Gorge. Consultation with the Somerset and Avon bird recorders verifies that, since the publication of the Atlas, there have been no Confirmed breeding records from within the Vale itself.

To the southwest of the study area the Somerset Ornithological Society Forum adds a Probable breeding record near Compton Bishop–Webbington and a long-term local resident there recalls Spotted Flycatchers nesting in his garden wall until relatively recently.

Field Survey Results

Distribution & Habitat Associations

During spring and summer 2025, I recorded 20 Spotted Flycatcher territories across the Vale: 13 Confirmed breeding sites, five Probable, and two Possible (

Table 1,

Figure 1). Each territory cluster likely represents a small sub-population, with others possible in under-surveyed areas.

Most records came from the surrounding hillsides at an average elevation of 139m compared to the Vale’s mean of 89m. While the species is not restricted to higher ground, the greater extent of woodland at these elevations appears to be the determining factor. Woodland covers 14% of the Vale as a whole (above the England average of 10%) but increases to 20% above 100m.

Of the 20 sites, ten fell within areas of statutory protection (SAC, SSSI and/or NNR), six within non-statutory Sites of Nature Conservation Interest (SNCI), and one in Forestry Commission woodland that includes a conservation remit. Only three sites lacked significant conservation designation.

Six main clusters were identified. The most important were the King’s–Rose woodlands, Cheddar Wood, and Dolebury Warren, each with four territories. Loxton Wood, the Barton Woods complex, and the Sandford–Mapleton woodlands each held two territories. Together with two additional records along the eastern margins, these form a broad arc of occupied sites to the northeast, east, south, and southwest of the Vale. Despite repeated visits, no Spotted Flycatchers were detected in the northwest, even though there were seemingly suitable woodland sites south of Banwell and north of Christon. Several other unsurveyed woodlands may still hold birds.

Spotted Flycatchers were consistently linked to woodland margins, rides, and glades adjoining species-rich grasslands or extensively grazed pasture. These ecotones create complex mosaics of trees, scrub, and open grassland that are particularly rich in aerial insects, their principal prey. Low-density livestock grazing appears to add further value by maintaining a varied sward thereby boosting insect numbers, while the livestock themselves and their dung attracts additional flies.

Importance of Mosaic Habitats

The strong association of Spotted Flycatchers with woodland edges and adjoining grasslands reflects a deeper ecological story. Recent interest in ‘rewilding’ has reignited debate over what Britain’s ‘natural’ landscape looked like after the last Ice Age. For much of the 20th century, ecologists assumed that closed-canopy forest represented the inevitable climax vegetation - the so-called ‘wildwood.’ Increasingly, however, this view has been challenged.

Growing evidence points instead to a more dynamic, open wood-pasture system, shaped by the grazing and browsing of large herbivores. Such landscapes would have been a shifting patchwork of grassland, scrub, and scattered veteran trees rather than continuous, closed forest.

Many of the Vale sites that now support Spotted Flycatchers echo this ancient pattern (

Plate 3). Their semi-open character not only supplies abundant foraging opportunities for flycatchers but also supports exceptional biodiversity more broadly, precisely because so many species evolved under and remain adapted to these conditions.

Why have Spotted Flycatchers been Under-recorded?

Timed tetrad visits, such as those used for the Somerset Atlas, almost inevitably under-record scarce, thinly distributed species. Limited survey effort and low densities mean that many local populations may go undetected.

Still, I often wonder how I personally overlooked Spotted Flycatchers in the Vale for more than a decade, despite repeatedly walking the same routes where they now reveal themselves so clearly. Was this a matter of recent population change, or simply my own blind spot? The truth likely lies between the two. Although the long-term trajectory is steep decline, there was a modest 4% increase in England between 2023 and 2024 (BTO/JNCC/RSPB, 2024), with perhaps a small corresponding rise in Somerset and Avon (B. Gibbs & R. Higgins, pers. comm.).

Plate 3.

A cluster of Spotted Flycatchers was found in and around Dolebury Warren; the site includes a wood pasture landscape including a mosaic of free-standing trees, scattered scrub, and flower-rich, cattle-grazed grassland. (Photo credit: Lincoln Garland).

Plate 3.

A cluster of Spotted Flycatchers was found in and around Dolebury Warren; the site includes a wood pasture landscape including a mosaic of free-standing trees, scattered scrub, and flower-rich, cattle-grazed grassland. (Photo credit: Lincoln Garland).

Equally, my own fieldcraft has evolved. I had unfairly dismissed the Spotted Flycatcher as an unremarkable looking ‘little brown job’ (LBJ) with barely a song. Careful observation over spring and summer 2025 overturned that perception. Once familiar with their behaviour, they became conspicuously easy to spot, perched upright on exposed branches, flicking their tails, before bursting into short, agile sallies to snatch insects in mid-air, often returning to the same launch-point. Their pale breast flashes in flight, and even their thin, high ‘tzee, tzee’ calls stand out in late summer, when most other songbirds fall silent.

With this awareness, I began to see them in habitats that had seemed empty before. Given the abundance of similar mosaic landscapes across the Mendips further to the west, many of them protected sites, it is highly likely that more local populations are yet to be discovered. Indeed, small-scale monitoring elsewhere in Britain is already revealing previously overlooked clusters (Catrin Eden, pers. comm.).

That said, it is important to remain cautious. These new discoveries, though heartening, do not represent a recovery. Numbers remain a fraction of their historic abundance. The presence of Spotted Flycatchers in the Vale is therefore less a sign of resurgence than a reminder of what still survives and of what we risk losing without continued care.

Conclusions

The recent discoveries in the Vale of Winscombe offer a rare glimmer of hope for the beleaguered Spotted Flycatcher, a species I had long assumed to be absent from the area, in line with its steep national decline. After more than a decade without a single encounter, a lone breeding pair in 2024 was soon followed by the remarkable revelation of multiple territories in 2025. This discovery suggests that the Vale, and quite possibly the wider Mendip Hills, serve as an important refuge, and perhaps even a source for future recovery at both local and regional scales.

Their persistence along the Vale’s hillsides is no accident. The mosaic of woodland margins, species-rich grasslands, scattered scrub, and veteran trees creates exactly the semi-open conditions that Spotted Flycatchers require. These landscapes, modern-day echoes of ancient wood-pasture systems, supply a wealth of aerial insects for foraging and plentiful perches for their characteristic sallying flights.

Nationally, the species remains Red-listed and a Species of Principal Importance, threatened by habitat loss, agricultural intensification, and climate change. Yet the clusters identified in the Vale show that where the right habitat mosaics survive, particularly within protected areas and low-intensity farmland, Spotted Flycatchers can still endure. The likelihood of further, as-yet-undetected populations in other Mendip sites only reinforces the need for ongoing monitoring and careful stewardship of these semi-open ecosystems.

The Vale of Winscombe thus stands not just as a local stronghold, but as a reminder that targeted conservation and sensitive land management can create the conditions for recovery. In a landscape where Spotted Flycatchers seemed lost, their discovery signals both resilience and possibility - if we choose to act on it.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Nick Gates, Brian Gibbs, Jim Hardcastle, Rupert Higgins, Chris Howard, Laura Howard, Trevor Riddle, and Mike Wells.

References

- Ballance, D. (2006). A History of the Birds of Somerset. Isabelline, Penryn.

- Ballance, D. et al. (2014). Somerset Atlas of Breeding and Wintering Birds 2007-2012. Somerset Ornithological Society.

- BTO (2025). Bird Trends 2024: Trends in Numbers, Breeding Success and Survival for UK Breeding Birds. www.bto.org/birdtrends.

- BTO/JNCC/RSPB (2024). The Breeding Bird Survey 2024 incorporating the Waterways Breeding Bird Survey: Population trends of the UK’s breeding birds. BTO, Thetford.

- Compton, T. (1893). A Mendip Valley: Its inhabitants and surroundings, being an enlarged and illustrated ed. of Winscombe sketches. Eddington & Cadbury.

- Eden, C. (2025). Scarcely spotted flycatcher, Bird Guides. Warners Group Publications. https://www.birdguides.com/articles/species-profiles/scarcely-spotted-flycatcher/.

- Garland, L. (2020). Birdlife along the Strawberry Line (Vale of Winscombe section). Nature in Avon, 80, 2-16.

- Toulson, S. (1983). The Mendip Hills: A Threatened Landscape. Victor Gollancz, London.

- Tree, I. (2018). Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm. Pan Macmillan, London.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).