Submitted:

14 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

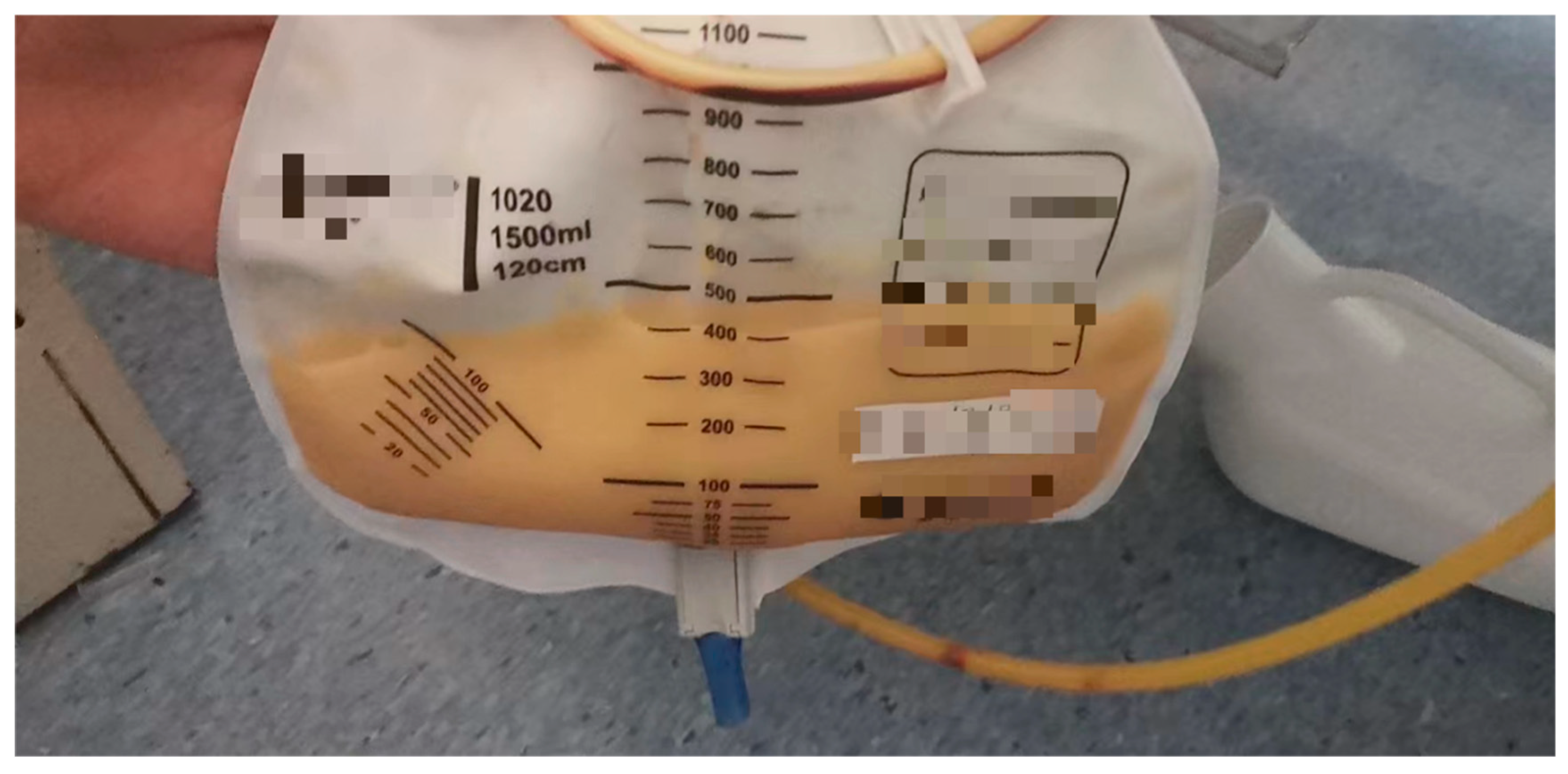

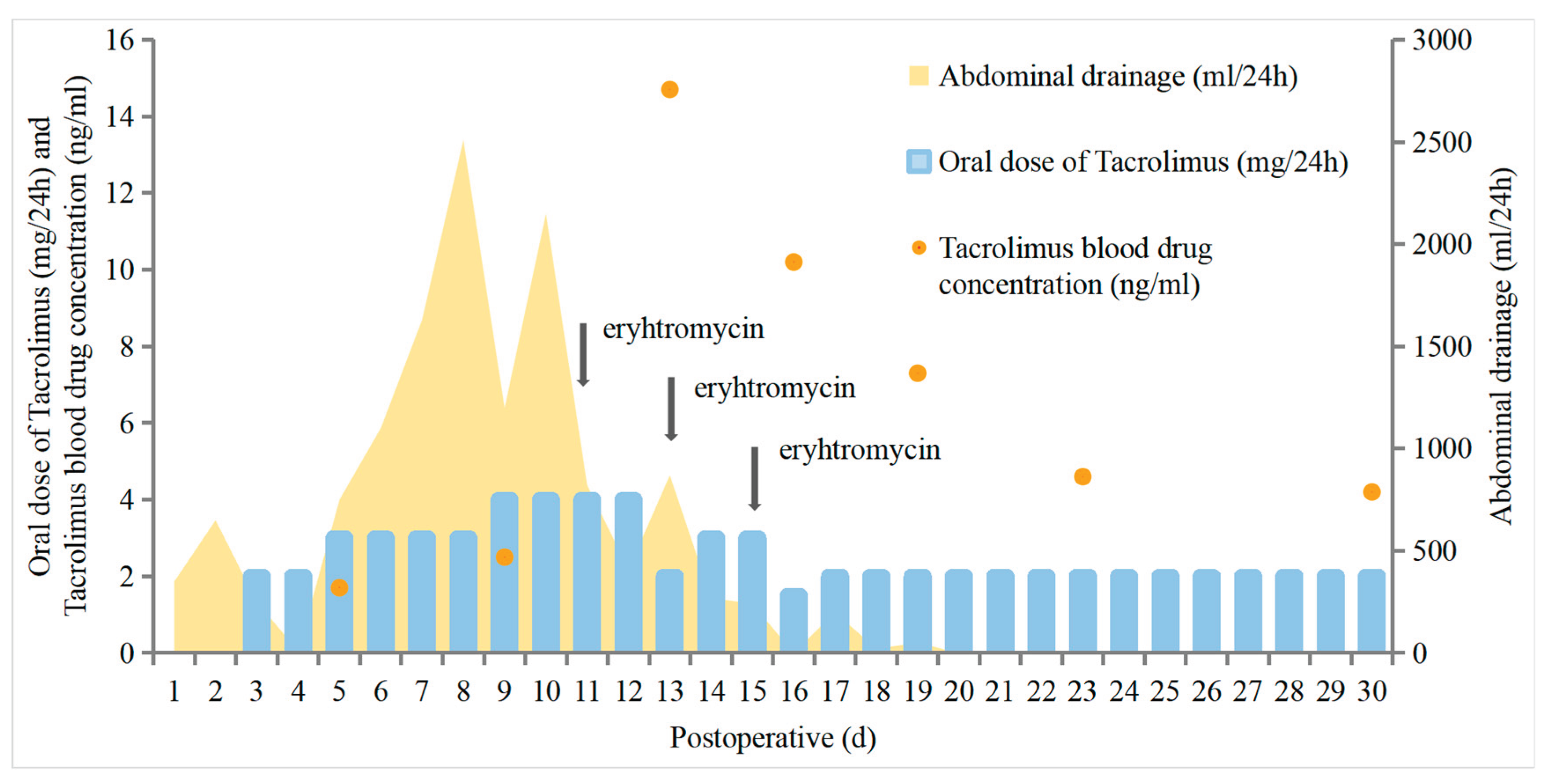

2. Case Presentation

Follow-up

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Authorship contribution statement

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, J.G.; Spiess, P.E.; Kamat, A.M.; Wood, C.G.; Hernandez, M.; Pettaway, C.A.; Dinney, C.P.; Pisters, L.L. Chylous Ascites After Post-Chemotherapy Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection: Review of the M. D. Anderson Experience. J. Urol. 2006, 176, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijichi, H.; Soejima, Y.; Taketomi, A.; Yoshizumi, T.; Uchiyama, H.; Harada, N.; Yonemura, Y.; Maehara, Y. Successful management of chylous ascites after living donor liver transplantation with somatostatin. Liver Int. 2007, 28, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Vaziri, H.; Gautam, A.; Ballesteros, E.; Karimeddini, D.; Wu, G.Y. Chylous Ascites: A Review of Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizaola, B.; Bonder, A.; Trivedi, H.D.; Tapper, E.B.; Cardenas, A. Review article: the diagnostic approach and current management of chylous ascites. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Akbulut, S.; Isik, B.; Ara, C.; Ozdemir, F.; Aydin, C.; Kayaalp, C.; Yilmaz, S. Chylous ascites after liver transplantation: Incidence and risk factors. Liver Transplant. 2012, 18, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler E, Bloyd C, Wlodarczyk S. Chylous Ascites. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 May;35(5):1586–7.

- Saucedo-Crespo, H.; Roach, E.; Sakpal, S.V.; Auvenshine, C.; Steers, J. Spontaneous Chylous Ascites After Liver Transplantation Secondary to Everolimus: A Case Report. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takuwa, T.; Yoshida, J.; Ono, S.; Hishida, T.; Nishimura, M.; Aokage, K.; Nagai, K. Low-fat diet management strategy for chylothorax after pulmonary resection and lymph node dissection for primary lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013, 146, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkataramanan R, Swaminathan A, Prasad T, Jain A, Zuckerman S, Warty V, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995 Dec;29(6):404–30.

- Iwasaki, K. Metabolism of Tacrolimus (FK506) and Recent Topics in Clinical Pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2007, 22, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetsugu, K.; Ikesue, H.; Miyamoto, T.; Shiratsuchi, M.; Yamamoto-Taguchi, N.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Matsukawa, K.; Uchida, M.; Watanabe, H.; Akashi, K.; et al. Analysis of the variable factors influencing tacrolimus blood concentration during the switch from continuous intravenous infusion to oral administration after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int. J. Hematol. 2016, 105, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Staatz, C.; E Tett, S. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Tacrolimus in Solid Organ Transplantation. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Jiang, F.; Zhou, R.; Jin, W.; Li, Y.; Duan, W.; Xu, L.; Yang, H. Clinical Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Co-Administration of Wuzhi Capsule and Tacrolimus in Adult Chinese Patients with Myasthenia Gravis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, ume 17, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Busafi, S.A.; Ghali, P.; Deschênes, M.; Wong, P. Chylous Ascites: Evaluation and Management. ISRN Hepatol. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, T.; Kobori, G.; Ito, K.; Nakagawa, H.; Takahashi, T.; Takaoka, N.; Somiya, S.; Nagahama, K.; Ito, M.; Megumi, Y.; et al. Complications and their management following retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in conjunction with retroperitoneal laparoscopic radical nephroureterectomy. Int. J. Urol. 2022, 29, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; He, L.; Cao, T.; Hu, C.; Liu, X. Managing Chyle Leakage Following Right Retroperitoneoscopic Adrenalectomy: A Case Study. Am. J. Case Rep. 2024, 26, e945469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Zhang, Z. Nano Carbon Tracer in the Repairing of Congenital Abdominal Chylorus Leakage. Indian J. Pediatr. 2023, 91, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, W. Post-esophagectomy chylothorax refractory to mass ligation of thoracic duct above diaphragm: a case report. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, T.; Yanagi, Y.; Hayashida, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Yoshimaru, K.; Taguchi, T. The incidence of chylous ascites after liver transplantation and the proposal of a diagnostic and management protocol. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, C.-C.; Lin, X.-S.; Yao, Z.-H.; Liu, Q.-H.; Zhu, L.; Lin, D.-J.; Wan, Y.-Y. Erythromycin poudrage versus erythromycin slurry in the treatment of refractory spontaneous pneumothorax. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassoulis, G.; Sichletidis, L.; Spyratos, D.; Chloros, D.; Zarogoulidis, K.; Kontakiotis, T.; Bagalas, V.; Porpodis, K.; Manika, K.; Patakas, D. Efficacy and Safety of Erythromycin as Sclerosing Agent in Patients With Recurrent Malignant Pleural Effusion. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 31, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Chen, Z.; Shen, X.; Xie, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Refractory thrombocytopenia could be a rare initial presentation of Noonan syndrome in newborn infants: a case report and literature review. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Q.-W.; Lin, Z.-Y.; Hu, X.-T.; Zhao, Q.-F. Treatment of persistent congenital chylothoraxwith intrapleural injection of sapylin in infants. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2016, 32, 1305–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Staatz, C.; E Tett, S. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Tacrolimus in Solid Organ Transplantation. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 623–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharanon, V.M. (.; Muangkasem, A.; Inprasit, N.M.(.; Chantharit, P.B.(. Patient With Probable Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis and Idiopathic Bilateral Chylothorax With Chylopericardium May Experience Unachievable Therapeutic Voriconazole Serum Levels. Ther. Drug Monit. 2025, 47, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow FS, Piekoszewski W, Jusko WJ. Effect of hematocrit and albumin concentration on hepatic clearance of tacrolimus (FK506) during rabbit liver perfusion. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997 May;25(5):610–6.

- Yoshikawa, N.; Takeshima, H.; Sekine, M.; Akizuki, K.; Hidaka, T.; Shimoda, K.; Ikeda, R. Relationship between CYP3A5 Polymorphism and Tacrolimus Blood Concentration Changes in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients during Continuous Infusion. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Nakanishi, K.; Yoshioka, T.; Tsutsui, Y.; Maeda, A.; Kondo, H.; Sako, K. Oral tacrolimus oil formulations for enhanced lymphatic delivery and efficient inhibition of T-cell’s interleukin-2 production. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 100, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Du, Y.; He, J.; Ge, J.; Wang, M.; Sun, R.; Zhu, H.; Ge, W. Distribution evaluation of tacrolimus in the ascitic fluid of liver transplant recipients with liver cirrhosis by a sensitive ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 45, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, P.; Bernier-Latmani, J.; Petrova, T.V.; Liu, M. Transport functions of intestinal lymphatic vessels. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignat, C. Clinically Significant Drug Interactions with New Immunosuppressive Agents. Drug Saf. 1997, 16, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, L.-H.; Wu, T.-H.; Tsai, T.-C.; Lee, W.-C. Coadministration of Erythromycin to Increase Tacrolimus Concentrations in Liver Transplant Recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).