1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused a global pandemic, and its causative agent has been identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [

1]. Although the current pandemic has subsided, the potential for viral mutations and localized resurgences remains, which highlights the need for long-term strategies to prepare for the emergence of new viruses [

2]. SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Coronaviridae, subfamily Orthocoronavirinae, genus Betacoronavirus, and subgenus Sarbecovirus. This virus possesses a genome of approximately 30 kb, containing 14 open reading frames (ORFs). Approximately two-thirds of the genome encodes 16 non-structural proteins (NSP1–NSP16), while the remaining portion encodes 9 accessory proteins and 4 structural proteins [

3,

4,

5]. The replication of SARS-CoV-2 begins with the translation of ORF1a and ORF1b following virus entry into the host cell. These genes are translated into a large polyprotein, which is subsequently cleaved by viral proteases into individual non-structural proteins (NSPs). Of these, NSP12 functions as an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and plays a central role in the replication and transcription of the viral genome [

6]. NSP12 consists of 932 amino acids and comprises three domains: an N-terminal nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase (NiRAN) domain, an interface domain, and a C-terminal RdRp domain [

5]. The interface domain connects NiRAN and RdRp domains, and the RdRp domain contains a catalytic center with an SDD motif (residues 759–761). Notably, the RdRp of SARS-CoV-2 also features a conserved GDD motif (residues 823–825), which is commonly found in other viral RdRps, such as hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5b and poliovirus 3D pol, and is essential for catalytic activity [

7].

Since the emergence of the original wild-type SARS-CoV-2, successive variants such as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta appeared, followed by the global dominance of Omicron variants belonging to the BA lineage. Among the Omicron subvariants, JN.1 was designated as a variant of interest (VOI) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in late 2023. More recently, additional sublineages such as KP.3, XEC, LP.8.1, NB.1.8.1, and XFG have continued to emerge [

8,

9,

10]. Through these mutations, SARS-CoV-2 can acquire genetic changes that enhance infectivity, immune evasion, and viral load, which may in turn reduce the effectiveness of existing treatments and vaccines [

11,

12,

13]. The NSP12 protein, a key enzyme in viral replication, harbors the P323L mutation, which has been consistently observed since the emergence of the Alpha variant. Additionally, the G671S mutation has been reported in variants such as Delta, BA.2, and XBB. In the case of JN.1, only the G671S mutation has been identified, whereas Omicron BA.2 possesses both P323L and G671S mutations [

14], which have been reported to increase viral replication and transmissibility [

15], highlighting the importance of developing novel target molecules that act effectively across diverse variants.

RNA aptamers are short single-stranded nucleic acids that form stable secondary structures and exhibit high binding affinity and specificity toward their target molecules [

16,

17]. Compared to antibodies, RNA aptamers offer advantages as therapeutic agents due to their lower production costs, smaller molecular sizes, and low immunogenicity [

18]. In particular, high-affinity aptamers can be selected through the SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment) process, which involves iterative rounds of selection conducted entirely in vitro [

19,

20,

21].

In this study, we aimed to identify RNA aptamers targeting NSP12, a key replication enzyme of SARS-CoV-2, and to evaluate their binding characteristics and polymerase inhibitory activities. The RNA aptamers selected in this study were composed of 2′-hydroxyl nucleotides or 2′-fluoro pyrimidines. SELEX was performed using purified NSP12 protein derived from the Omicron variant, and high-specificity aptamer candidates were obtained through iterative selection rounds. Binding to NSP12 was confirmed by RNA–protein pull-down assays, and binding affinity was quantitatively assessed through Kd value analysis. In addition, primer extension assays demonstrated the ability of the aptamers to inhibit polymerase activity, and competition assays further validated their binding specificity. Furthermore, comparative analysis across multiple NSP12 variants—including wild-type, Alpha, Delta, and Omicron—revealed that the selected aptamers exhibited consistent binding and inhibitory activity across most variants.

The two classes of RNA aptamers identified were composed of 2′-hydroxyl nucleotides or 2′-fluoro pyrimidines, specifically bound to SARS-CoV-2 NSP12. These aptamers demonstrated high-affinity binding and effectively inhibited NSP12 activity regardless of variant type, suggesting their potential as foundational candidates for the development of broad-spectrum anti-viral agents.

2. Results

2.1. Expression and Purification of NSP12(P323L/G671S) and RNA Aptamer Selection by SELEX

SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 protein is typically expressed in an insoluble form in

E. coli. To improve its solubility, we used an N-terminal His–SUMO-tagged expression vector (Addgene plasmid #169188), which has been reported to enhance protein folding and solubility [

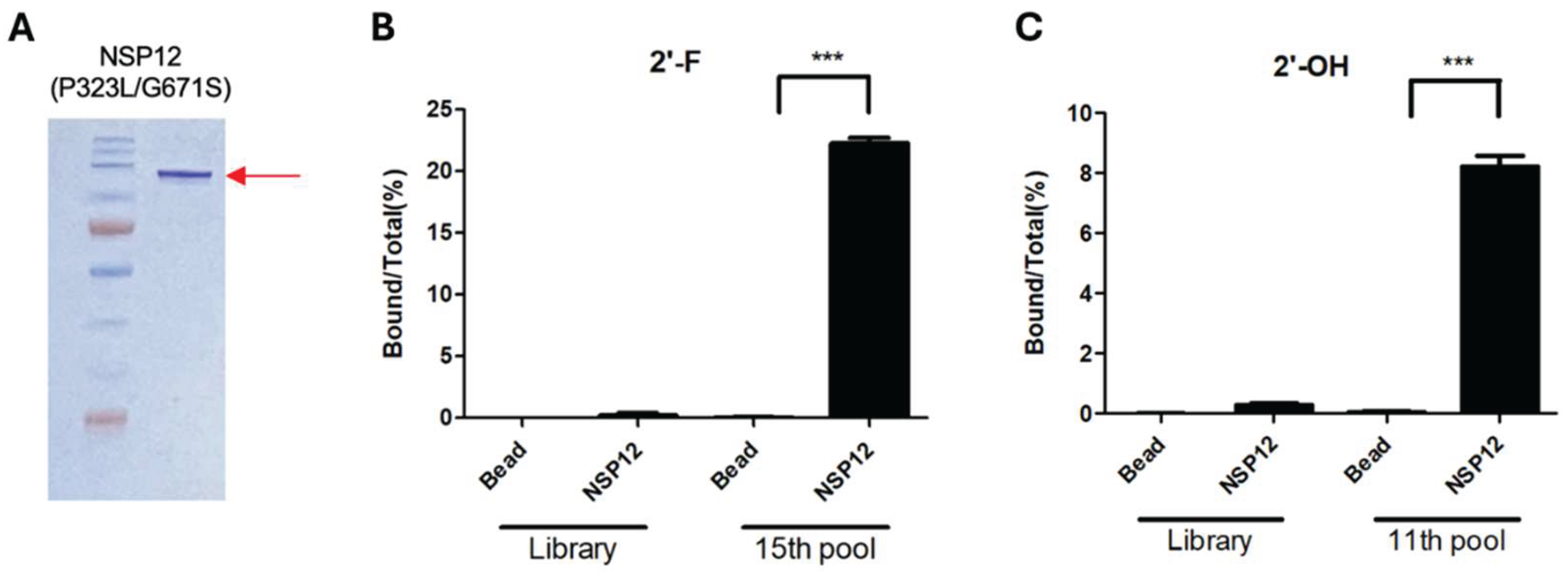

22]. An induction test was performed to optimize expression and the best yield was obtained with 0.4 mM IPTG at 16 °C for 16 h. Large-scale expression was conducted using these conditions, and the eluted protein showed a distinct ~125 kDa band on SDS-PAGE (

Figure 1A), which corresponded to the expected size of NSP12 including the His–SUMO tag. The protein used in this study was derived from the Omicron variant, and thus, harbored P323L and G671S mutation. For this reason, we referred to it as NSP12(P323L/G671S). The purified protein was quantified using the Bradford assay and utilized in SELEX and binding assays.

The purified NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein was used to select RNA aptamers by SELEX. The selection was performed using an RNA library containing a 40-nucleotide randomized region; nonspecific binders were eliminated by pre-clearing with Ni-NTA magnetic beads before incubation with the target protein. RNA species bound specifically to NSP12(P323L/G671S) were recovered, reverse-transcribed, PCR-amplified, and transcribed in vitro to generate RNA pools for subsequent rounds. To enhance aptamer diversity and assess potential for downstream applications, either unmodified 2′-hydroxyl (2′-OH) RNAs or chemically stabilized 2′-fluoro pyrimidine (2′-F) RNAs was independently subjected to SELEX. Selection stringency was increased in later rounds by introducing competitor yeast tRNA and reducing the target protein concentration. This strategy enabled the enrichment of high-affinity aptamers with improved specificity and stability for NSP12(P323L/G671S).

RT-PCR–based confirmation assays were performed to evaluate the binding enrichment of the selected RNA pools. For the 2′-F RNA pool, binding was assessed by comparing it with the initial RNA library and the pool RNAs obtained after 15 rounds of SELEX. The 15th-round pool exhibited ~22% binding to NSP12(P323L/G671S), which was significantly higher than the background binding of the initial library and the bead-only control (

Figure 1B), indicating successful enrichment of high-affinity binders. A similar analysis was conducted for the 2′-OH RNA pools obtained after 11 SELEX rounds. These showed ~8% binding to NSP12 (

Figure 1C), confirming that target-specific aptamers were also enriched in this pool.

(A) NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein containing a SUMO tag was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) and purified by affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE analysis showed a prominent band at approximately 125 kDa (red arrow), consistent with the expected molecular weight of SUMO-tagged NSP12. (B) Binding of the 15th-round 2′-fluoro-modified (2′-F) RNA aptamer pools to NSP12(P323L/G671S). The initial library and bead-only groups served as negative controls. (C) Binding of the 11th-round 2′-hydroxyl (2′-OH) RNA aptamer pools to NSP12(P323L/G671S). Results are means ± SDs. ***p < 0.001 (by the two-tailed Student’s t-test).

2.2. Grouping and Comparative Binding Evaluation of SELEX-Enriched Aptamers

To identify individual aptamer sequences, RT-PCR was performed using the 15th-round 2′-F RNA pools or the 11th-round 2′-OH RNA pools as templates, and this was followed by T-blunt cloning and sequencing. Sequences derived from the 2′-F and 2′-OH pools are designated the "CV-F" and "CV-OH" groups, respectively, and serial identifiers (e.g., CV-F1, CV-OH1) are assigned for clarity.

Sequence analysis revealed five sequence groups in the 2′-F pools and four groups in the 2′-OH pools (

Table 1), based on sequence similarity and predicted secondary structure. Representative aptamers from each group, vis. CV-F1 to CV-F5 and CV-OH1 to CV-OH4 were selected for binding analysis.

Aptamer groups were classified based on sequence similarity and predicted secondary structure. The number of identical clones in each group is indicated in parentheses. Within each group, a representative sequence is shown, and identical regions are represented by dashes (–). Nucleotide differences from the representative sequence are highlighted in red.

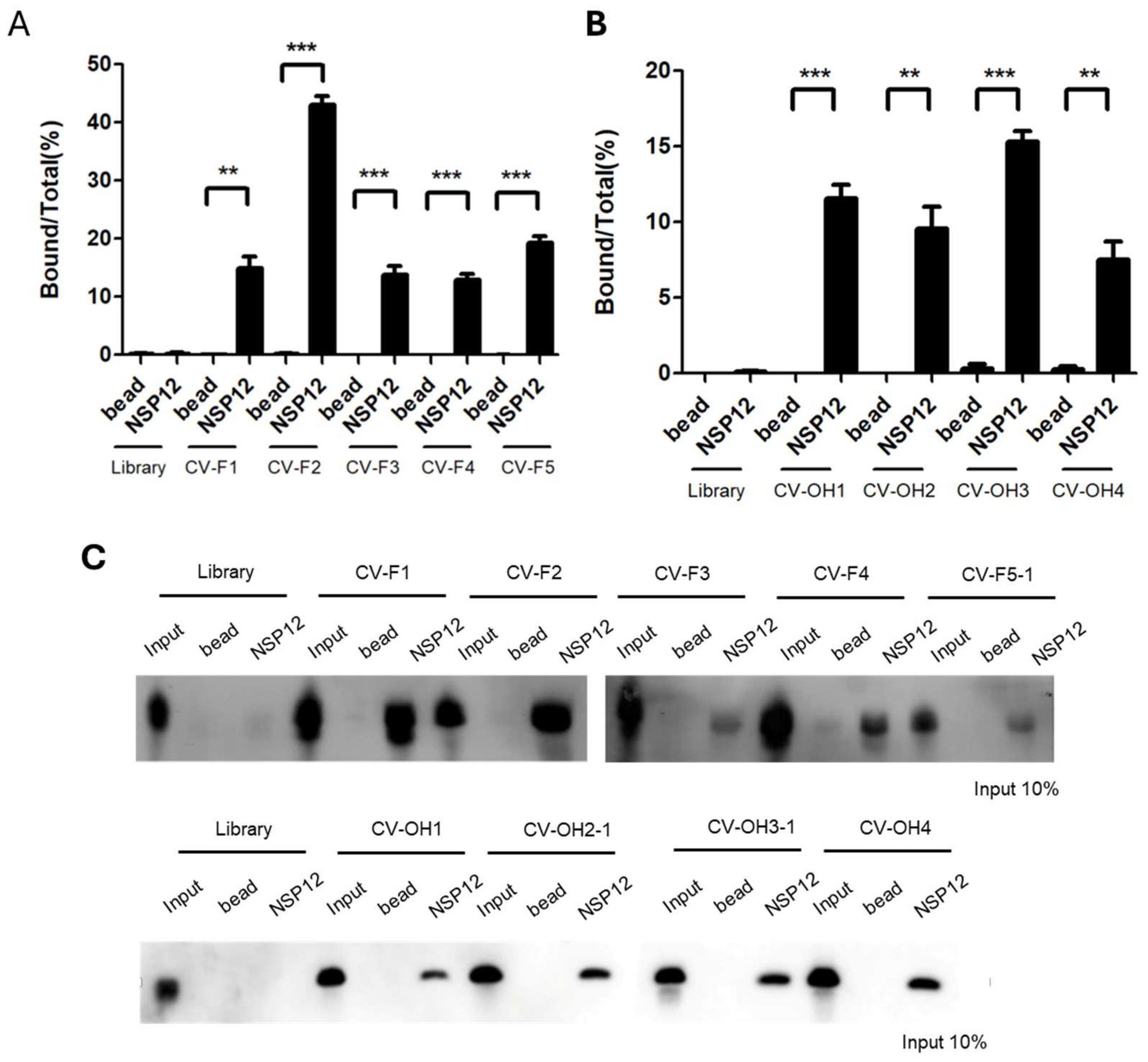

Binding affinity to NSP12(P323L/G671S) was assessed by qRT-PCR quantification and RNA–protein pull-down assays. Of the 2′-F aptamers, CV-F2 had the highest binding activity with a bound/total RNA ratio of ~40% (

Figure 2A). CV-F1, CV-F3, CV-F4, and CV-F5-1 showed relatively weaker binding. For the 2′-OH aptamers, qRT-PCR analysis revealed moderate binding across all candidates and CV-OH3-1 exhibited the highest affinity (~17%) (

Figure 2B). These results were corroborated by pull-down assays, which showed CV-F2 and CV-F1 had strong binding ability, and the other 2’-F aptamer clones and all 2’-OH RNA aptamer clones tested had moderate binding ability (

Figure 2C).

Together, these results indicate that CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 possess the strongest binding affinities within their respective groups, and therefore, these two aptamers were selected for further functional studies.

(A)qRT-PCR–based quantification of 2′-F RNA aptamers. Among the candidates, CV-F2 showed highest binding to NSP12(P323L/G671S) (~40%). (B) qRT-PCR–based quantification of 2′-OH RNA aptamers. CV-OH3 showed the highest binding (~17%). (C) RNA–protein pull-down assay. Three lanes were applied: The input lanes represent 10% of the total RNA used in each reaction, which was directly loaded onto gel without binding or washing steps. This lane served as an internal control to validate RNA detection and allow for quantitative comparisons. The bead lanes included magnetic beads without NSP12 protein and servied as negative controls to assess nonspecific binding. The NSP12 lanes included RNA aptamers that were incubated with the SARS-CoV-2 NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein to evaluate specific binding. (Upper panel) Results of 2′-F aptamers. Strong binding signals were observed for CV-F2 and CV-F1, whereas weaker signals were observed for CV-F3 to CV-F5-1. (Lower panel) Results of 2′-OH aptamers. Moderate binding signals were observed for all aptamer clones. Results represent means ± SDs (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

2.3. Affinity and Specific Binding of Selected RNA Aptamers

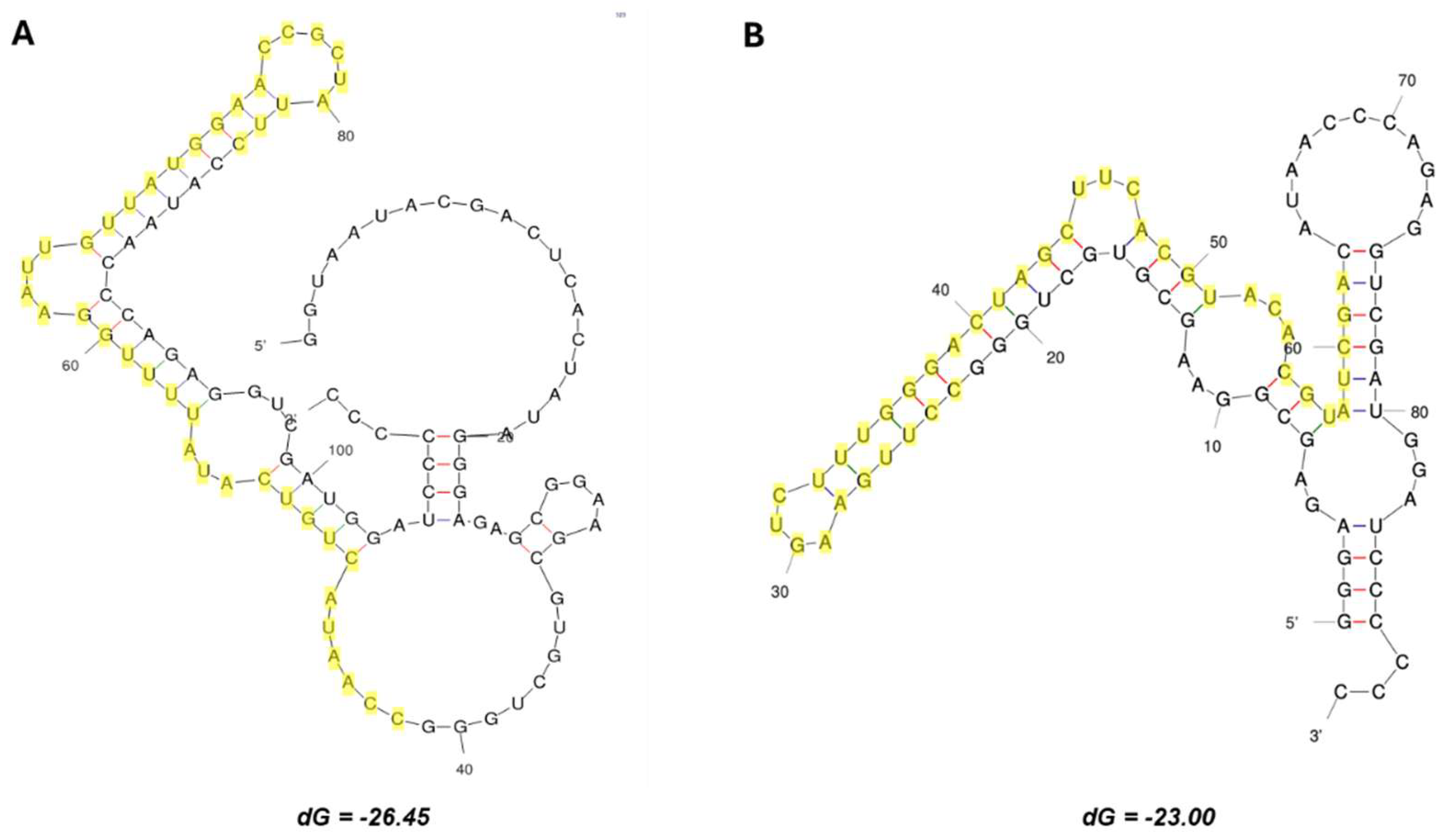

The predicted secondary structures of the representative aptamers CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 are shown in

Figure 3. Minimum free energy predictions using the mfold web server (

https://www.unafold.org/mfold/applications/rna-folding-form.php) indicated each aptamer forms a distinct stem–loop structure. The regions highlighted in yellow indicate sequences enriched during SELEX, which we presume play a critical role in NSP12 binding.

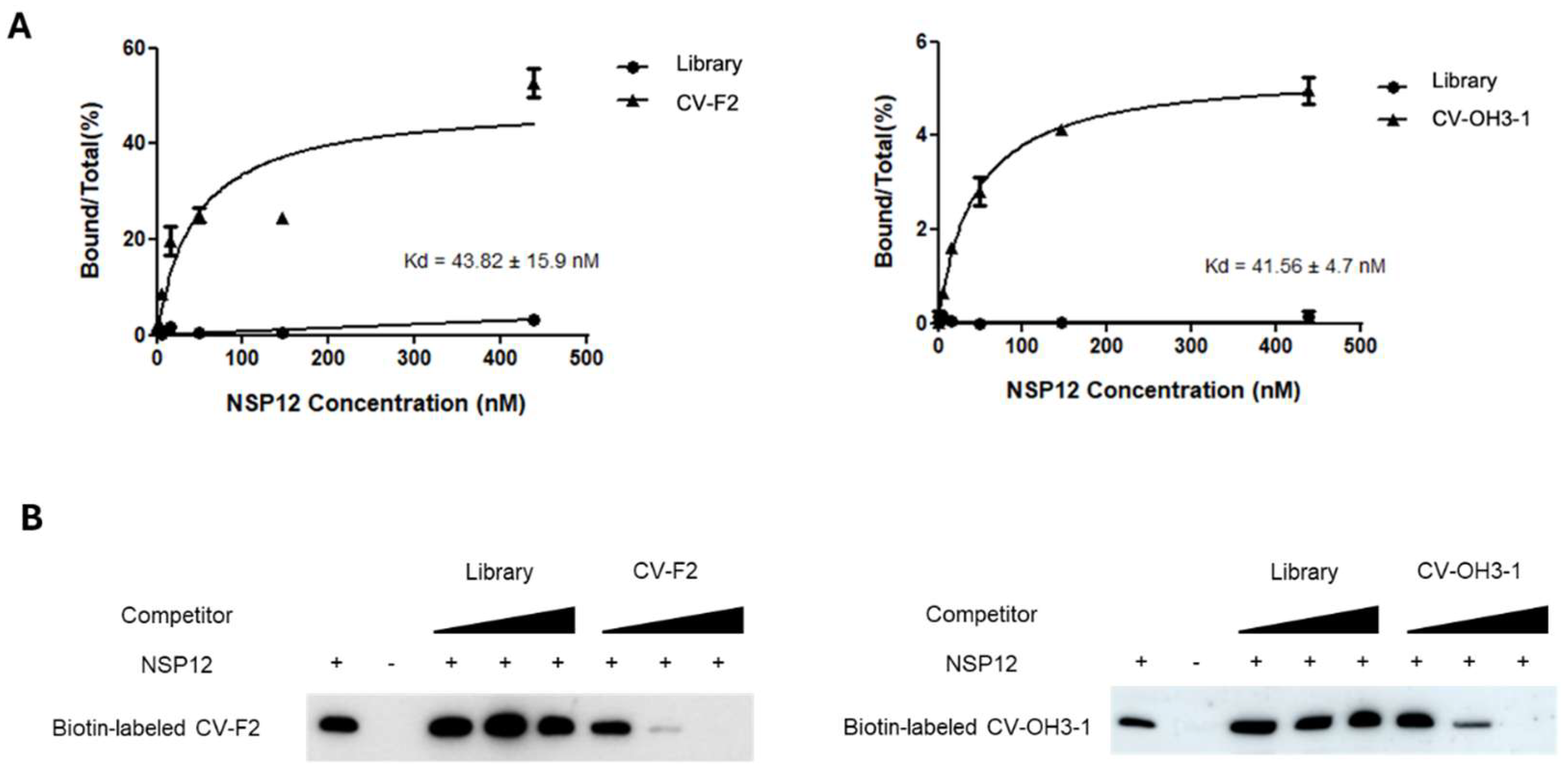

qPCR-based Kd analysis was used to quantitatively evaluate the binding affinity of the selected aptamers for SARS-CoV-2 NSP12(P323L/G671S) (

Figure 4A). Experiments were conducted at a constant aptamer concentration and gradually increasing concentrations of NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein. After each binding reaction, the amount of RNA bound to beads was quantified by qPCR. Relative binding ratios were then calculated and used to generate binding curves.

As a result, the 2′-F aptamer CV-F2 exhibited a binding affinity with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 43.82 ± 15.9 nM for NSP12(P323L/G671S), while the 2′-OH aptamer CV-OH3-1 had a Kd value of 41.56 ± 4.7 nM (

Figure 4A), indicating both aptamers possess high binding affinity in the nanomolar range for NSP12(P323L/G671S).

In contrast, the RNA library used as a negative control did not generate a specific binding curve despite increasing protein concentrations, and thus, no Kd value could be determined. This observation suggests that the library RNA binds nonspecifically to NSP12 or has very low binding affinity.

To evaluate aptamer binding specificity, a competition assay was conducted using an RNA–protein pull-down approach (

Figure 4B). In this experiment, biotin-labeled aptamers were incubated with NSP12(P323L/G671S) and unlabeled aptamers of the same sequence or the nonspecific RNA (library RNA). Changes in the amount of pulled-down biotin-labeled aptamer were then determined (

Figure 4B). The addition of the unlabeled library RNA did not affect the band intensity of the pulled-down aptamers. However, when unlabeled aptamers of the same sequence were used as competitors, the band intensity of the biotin-labeled aptamers gradually and dose-dependently decreased.

These results indicate that CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 have high affinity and specificity for SARS-CoV-2 NSP12(P323L/G671S) and are promising candidates for the development of anti-viral therapeutics.

(A)Binding curves of CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 to NSP12(P323L/G671S) as determined using a qRT-PCR–based assay. Aptamers were incubated with increasing concentrations of NSP12 protein, and bound fractions were quantified. CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 exhibited high binding affinity with dissociation constants (Kd) of 43.82 ± 15.9 nM and 41.56 ± 4.7 nM, respectively. The RNA library control showed negligible binding.

(B) RNA–protein pull-down competition assay using biotin-labeled aptamers. Increasing concentrations of unlabeled competitor RNAs (the same aptamer or non-specific library RNA) were added to assess binding specificity. The bindings of biotin-labeled CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 were effectively inhibited by their unlabeled counterparts but not by library RNA, indicating specific interactions with NSP12.

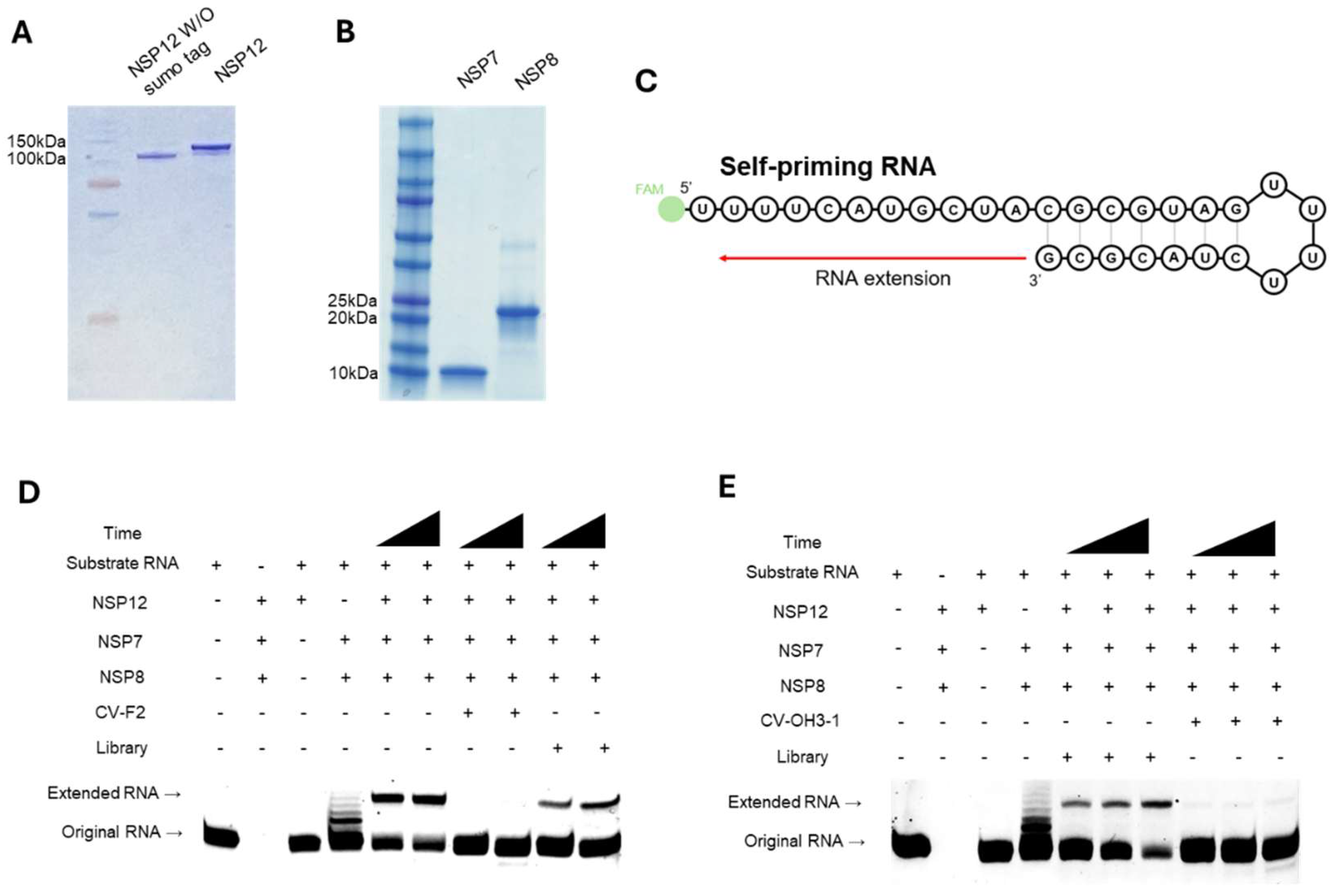

2.4. Inhibition of NSP12(P323L/G671S) Replication Activity by Selected RNA Aptamers

A primer extension assay was used to evaluate the inhibitory effect of the selected aptamer candidates on the polymerase activity of NSP12(P323L/G671S). For this assay, we used the purified RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) complex of SARS-CoV-2, containing NSP12, NSP7, and NSP8. Notably, NSP12 protein, from which the SUMO tag had been removed, was employed (

Figure 5A). Purified NSP7 and NSP8 proteins were also confirmed by SDS-PAGE (

Figure 5B). The polymerization reaction was performed using a self-priming FAM-labeled RNA template (

Figure 5C), and the extension reaction was monitored to assess polymerase activity.

The ability of CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 to inhibit polymerase activity was examined. In the presence of either of these aptamers, the intensity of the extended RNA band was markedly reduced, indicating that they inhibited NSP12 activity and interfered with the RNA extension reaction (Figs. 5D and 5E). In contrast, under the same conditions, the library RNA did not have an inhibitory effect. These results suggest that CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 aptamers specifically bind to NSP12 and effectively inhibit the functional activity of the replication complex and the RNA replication mechanism of SARS-CoV-2.

(A)SDS-PAGE analysis of purified NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein with or without the SUMO tag. A single band around 100 kDa indicateed successful purification. A molecular weight marker was loaded in the leftmost lane. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of NSP7 and NSP8 cofactors, showing distinct bands at ~10 kDa and ~20 kDa, respectively. (C) Schematic of the self-priming RNA substrate used for the primer extension assay. The RNA substrate included a 5′ FAM label and forms a stem-loop structure that enables self-priming from the 3′ end. Polymerase activity results in RNA extension toward the 5′ end of the substrate, generating a longer RNA product. (D and E) Primer extension assays were used to evaluate the inhibitory effects of selected RNA aptamers on the polymerase activity of SARS-CoV-2 NSP12(P323L/G671S). Reactions were performed using the self-priming RNA substrate in the presence of NSP12, NSP7, and NSP8 proteins. (D) CV-F2 (2′-F RNA aptamer) and (E) CV-OH3-1 (2′-OH RNA aptamer) both resulted in a marked reduction of the extended RNA product, indicating polymerase inhibition. In contrast, incubation with the initial aptamer libraries did not affect polymerase activity. Components in each gel lane are indicated above each image.

2.5. Binding to NSP12 Variants and Inhibition of Their Replication Activity by the Selected RNA Aptamers

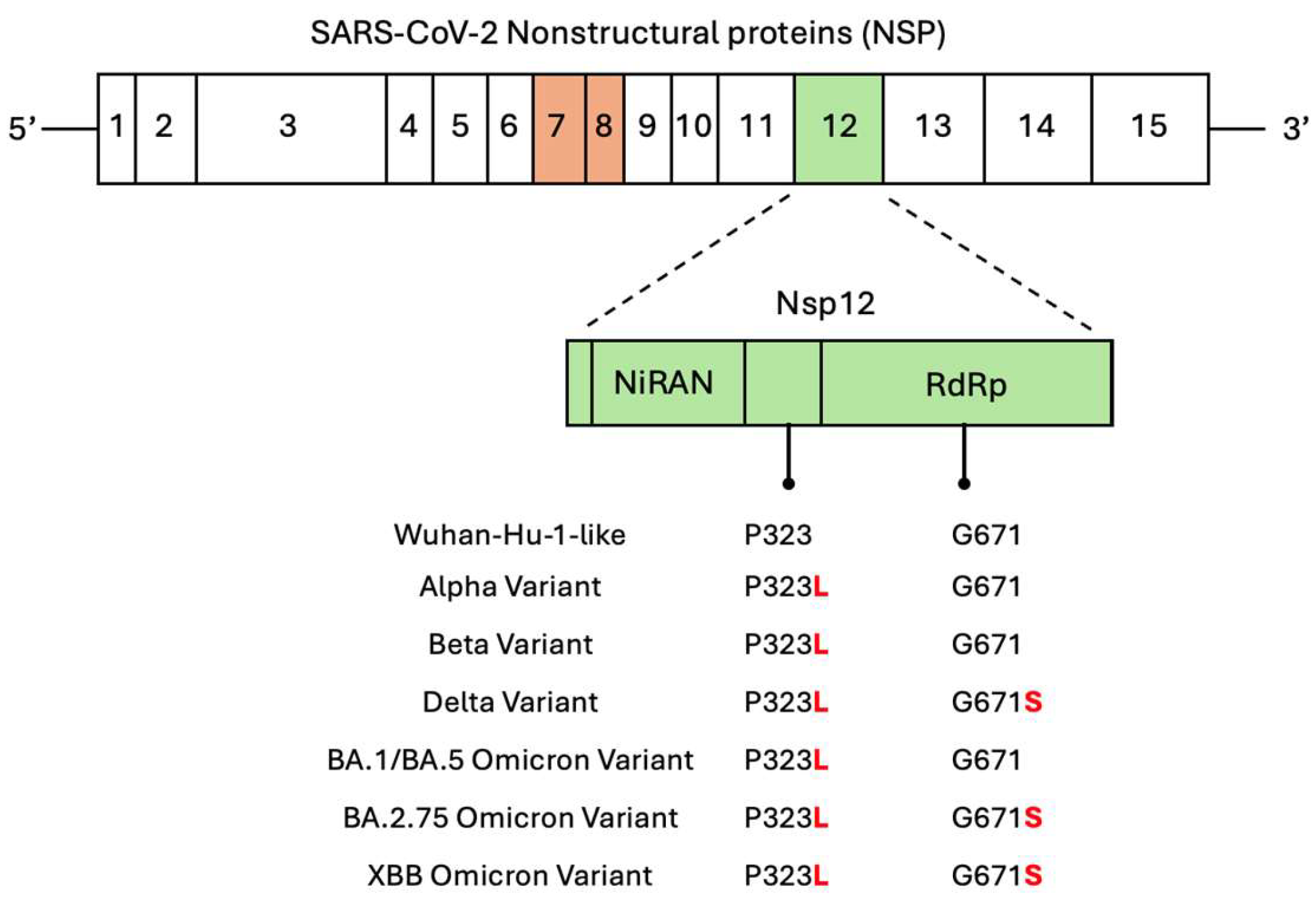

To evaluate the applicability of the selected aptamers across SARS-CoV-2 variants, we investigated their binding affinities and inhibitory activities against NSP12 proteins carrying key mutations. NSP12 is a highly conserved viral replicase with NiRAN and RdRp domains, but amino acid substitutions at positions P323 and G671 have been frequently reported among major SARS-CoV-2 variants (

Figure 6). On the other hand, the P323L mutation is present in early variants, including Alpha, Beta, and Delta, while the G671S mutation is commonly found in later variants, including Delta, BA.2, and XBB lineages. The Omicron-type NSP12 used in our SELEX process contained both P323L and G671S mutations, and thus reflected a prevalent mutation pattern.

Scheme 2. non-structural proteins (NSPs), which also shows NSP12, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which contains an N-terminal NiRAN domain and a C-terminal RdRp domain. Furthermore, the amino acid residues P323 and G671, located in the NiRAN and RdRp domains, respectively, are known mutation hotspots. The mutation profiles of representative SARS-CoV-2 variants are shown below. The P323L substitution is conserved across all listed variants, while G671S is found in Delta, BA.2.75, and XBB Omicron variants.

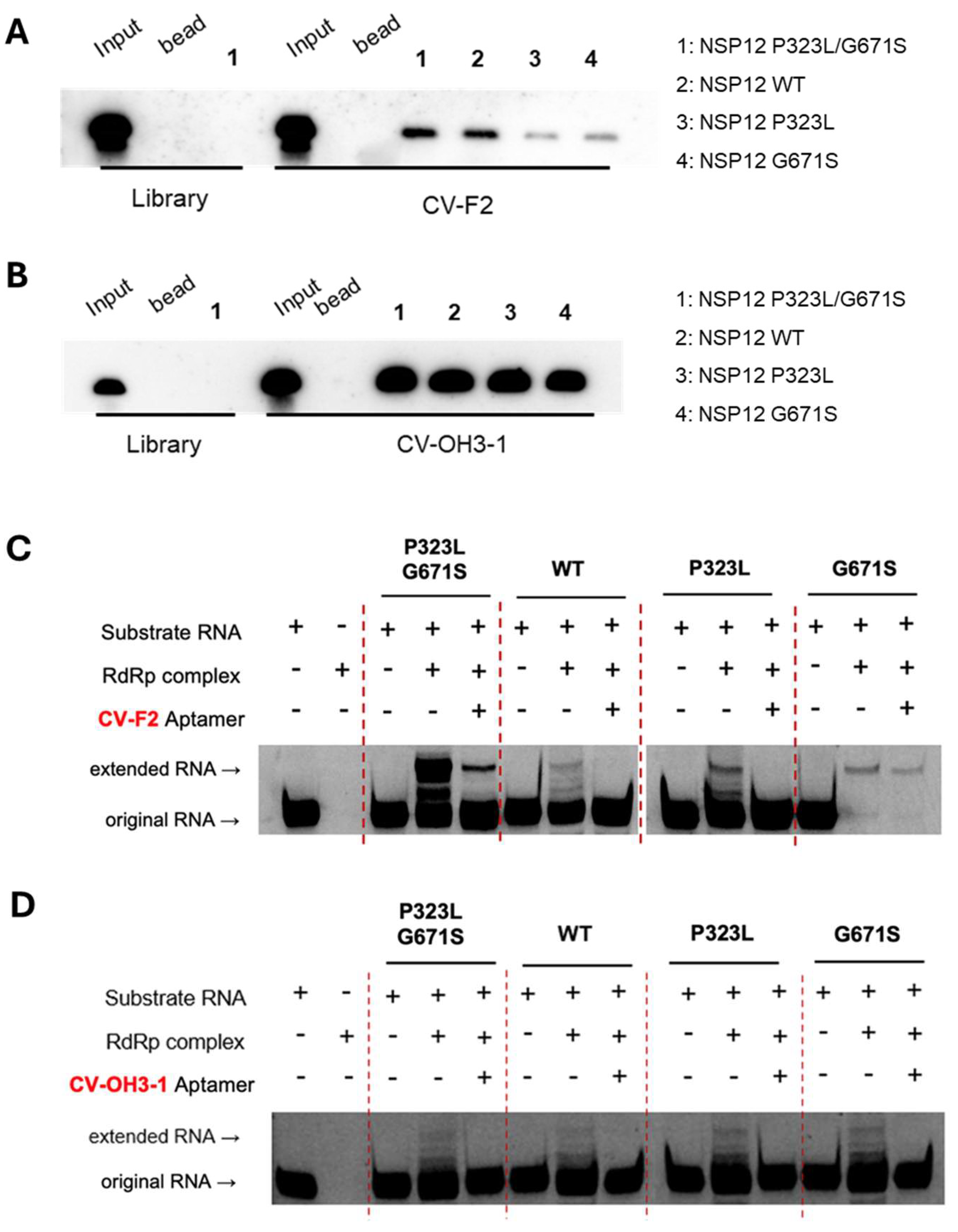

Given the high mutation rate of RNA viruses and the potential impact of such substitutions on aptamer–target interactions, we investigated whether the selected aptamers retain functionality across multiple NSP12 variants. To this end, we generated recombinant NSP12 proteins representing the wild-type, single mutants (P323L or G671S), or the double mutant (P323L/G671S). RNA–protein pull-down assays revealed that both CV-F2 (the 2′-F aptamer) and CV-OH3-1 (the 2′-OH aptamer) specifically bound to all NSP12 variants tested, including the wild-type and the mutant forms (Figures 7A and 7B).

We also evaluated the inhibitory effects of the aptamers using primer extension assays. CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 both effectively suppressed the RNA polymerase activity of NSP12 complex reconstituted with NSP7 and NSP8 cofactors, and this inhibition was consistently observed across the wild-type and P323L, G671S, and P323L/G671S forms of NSP12 (Figures 7C and 7D). In contrast, the initial aptamer libraries did not exhibit inhibition under the same conditions.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the selected aptamers maintain strong binding affinity and robust inhibitory activity regardless of variant-associated NSP12 mutations, and highlight their potential as broad-spectrum anti-viral agents targeting the viral RNA polymerase complex across diverse SARS-CoV-2 lineages.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of the binding ability and replication inhibition activity of RNA aptamers against various SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 variants.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of the binding ability and replication inhibition activity of RNA aptamers against various SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 variants.

(A and B) RNA–protein pull-down assays were conducted to examine the binding of biotin-labeled CV-F2 (A) and CV-OH3-1 (B) aptamers to NSP12 proteins carrying different mutations (WT, P323L, G671S, or P323L/G671S). Magnetic beads were used to isolate RNA–protein complexes, which were detected by streptavidin-based chemiluminescence. The initial RNA library was included as a negative control. (C and D) Primer extension assays were conducted to assess whether CV-F2 (C) and CV-OH3-1 (D) aptamers could inhibit the polymerase activity of the RdRp complex (NSP12 + NSP7 + NSP8). Using a self-priming RNA substrate, each aptamer significantly reduced the production of the extended RNA product across all NSP12 variants, including the WT and single and double mutants, indicating both possessed variant-independent inhibitory activity.

3. Discussion

In this study, we identified and functionally validated high-affinity RNA aptamers that bind to and inhibit the activity of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) NSP12 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Notably, the SELEX process was performed using a mutant form of NSP12 (P323L/G671S) as the target, with the goal of developing anti-viral aptamers that retain efficacy against emerging viral variants.

The aptamers CV-F2 (2′-F modified RNA) and CV-OH3-1 (2′-OH RNA), identified by SELEX, exhibited nanomolar (nM) range dissociation constants (Kd), indicating strong and specific binding affinity for SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 protein. RNA–protein pull-down assays and competition experiments demonstrated that both aptamers showed significantly higher binding specificity than the initial RNA library. Notably, binding was competitively inhibited only by the addition of the same unlabeled aptamer sequence, which supported the notion that the interaction between the aptamer and NSP12 is based on selective structural complementarity.

Functional analysis using a primer extension assay confirmed that CV-F2 and CV-OH3-1 effectively inhibited the polymerase activity of NSP12 protein. Importantly, this inhibitory effect was consistently observed not only with the P323L/G671S double mutant NSP12 used during SELEX, but also with the wild-type NSP12 and each of the single mutants (P323L and G671S). This finding highlights the broad applicability of the aptamers and suggests they are not limited to specific mutations but are effective against various NSP12 variants that may arise in different SARS-CoV-2 strains. As an RNA virus, SARS-CoV-2 exhibits a high mutation rate, and in particular, the P323L mutation in NSP12 protein has been consistently maintained across major variants of concern, including the Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron variants [

23,

24]. Moreover, the G671S mutation has been detected at very high frequencies, for example, at ~97.8% in Delta variants and at ~99% in the Omicron XBB subvariant [

25]. Comprehensive sequence analyses have shown that the P323L mutation in NSP12 occurs with a frequency of approximately 88.2%, while G671S is present in about 15.6% of sequences [

25]. These mutations have been shown to enhance the stability and enzymatic activity of RdRp complex, thereby increasing the efficiency of viral replication and transmission [

15,

26]. This study demonstrates that the aptamer-based approach can effectively respond to the mutational diversity of SARS-CoV-2.

Conventional therapeutic strategies against SARS-CoV-2 have primarily relied on antibodies or small molecules; for example, remdesivir is a representative small-molecule RdRp inhibitor. However, cases have been reported in which immunocompromised patients developed drug-resistant mutations, such as E802D, in the nsp12 gene during remdesivir treatment [

27]. Additionally, the emergence of NSP12 mutations has been flagged as a potential concern for resistance against RdRp-targeting small molecules, including remdesivir and molnupiravir [

28,

29]. In contrast, aptamers offer several advantages, including structural flexibility, low immunogenicity, ease of synthesis, and chemical stability, making them promising next-generation therapeutic candidates capable of adapting to rapidly evolving viruses [

30,

31].

The aptamers identified in this study exhibited high-affinity binding to and effective inhibition of the purified RdRp complex (NSP12/NSP7/NSP8) in vitro, suggesting potential utility for precisely modulating and analying the viral replication process. Furthermore, chemical modifications, such as 2′-fluoro are known to enhance in vivo stability, and thereby further increase the therapeutic potential of aptamers [

32,

33,

34].

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the antiviral activities of the aptamers have not been validated in cellular or animal models, and thus further studies are required to assess their efficacy and stability under actual infection conditions. Second, structural information on the binding interface between the aptamers and the target protein is lacking, which means future structural biological approaches, such as cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), should be explored to provide a more precise understanding and means of optimizing the binding mechanism. Lastly, strategies for enhancing cellular uptake and in vivo delivery of the aptamers, such as conjugation with drug delivery platforms like dendrimers or lipid nanoparticles, should also be considered

In summary, this study successfully identifies highly specific aptamers targeting the SARS-CoV-2 NSP12 (P323L/G671S) protein and demonstrates that they retain strong binding affinity and polymerase inhibitory activity across various NSP12 variants. These findings highlight the potential of aptamers as novel anti-viral platforms against SARS-CoV-2 and its emerging variants.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. NSP12 protein purification

The pK27Sumo_His-SUMO-nsp12 (SARS-CoV-2) expression vector (Addgene plasmid #169188; Addgene, Watertown, MA) was transformed into E. coli BL21 competent cells. Transformed cells were cultured in 1 L of LB medium containing 10 µg/mL kanamycin and induced with 0.4 mM IPTG at 16°C for 16 h. After harvesting by centrifugation (4,000 rpm, 4°C), cell pellets were stored at –80°C overnight. For purification, pellets were resuspended in His-SUMO lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40, 30 mM imidazole), and treated with lysozyme (100 mg/mL) at 4°C for 3 h. Cells were then lysed by sonication and centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 4°C, 1 h). Supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 3 h at 4°C with rotation and loaded onto a polypropylene column. The column was washed twice with His-SUMO buffer, and eluted sequentially with 100 mM, 200 mM, and 400 mM imidazole-containing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% NP-40). Eluted fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel. Collected fractions were pooled and dialyzed using a 10,000 MWCO membrane (Cellu-Sep, Dohgil Biotech, Seoul, Republic of Korea) in His-SUMO dialysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 10% glycerol, 0.02% NP-40, 1 mM DTT) at 4°C overnight, and then dialyzed again for 3 h in fresh buffer. The final purified protein was stored at –80°C.

4.2. NSP7and NSP8 protein purification

The pQE-(NSP12)-pcI-ts,ind+-(NSP7-NSP8) vector (Plasmid #160540) was obtained from Addgene, and PCR was performed using this vector as a template to amplify the NSP7 and NSP8 genes individually. The 5′ primer (5’-ATGTCTAAGATGAGTGATGT-3’) and the 3′ primer (5’-TCATTGCAGGGTTGCGC-3’) were used to amplify NSP7, and the 5′ primer (5’-ATGGCTATAGCATCTGAATT-3’) and 3′ primer (5’-TTACTGCAGTTTTACGGCCG-3’) were used to amplify NSP8. Each PCR reaction contained 10 pmol of the forward primer, 10 pmol of the reverse primer, and 2× CloneAmp HiFi polymerase mix (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). The PCR conditions were as follows: 98°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C for 10 seconds, repeated for 35 cycles. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into pET-28a(+) vector. For protein expression, the resulting recombinant vectors were transformed into BL21 competent cells. Protein expression was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG at 37°C for 4 h. After induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at –80°C overnight. Pellets were lysed by resuspending them in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2.5 mM DTT), adding lysozyme (100 mg/mL), and incubating at 4°C with rotation. Cell disruption was performed by sonication, and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation. The supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen) and loaded onto a polypropylene column. After washing with buffer containing 50 mM imidazole, proteins were eluted stepwise using 100, 200, and 400 mM imidazole-containing buffers. Elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10%) to confirm purity. For buffer exchange, proteins were dialyzed overnight at 4°C using dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) and then for an additional 3 h in fresh buffer. Final protein samples were stored at –80°C.

4.3. In vitro transcription and purification of 2’-OH and 2-F RNA libraries

Two types of RNA libraries were prepared for SELEX: a 2′-hydroxyl (2′-OH) RNA library and a 2′-fluoro (2′-F) modified RNA library. Both were transcribed from a randomized N40 DNA library generated by PCR. To synthesize the 2′-OH RNA library, in vitro transcription was performed using 1 µg of DNA template, 10× transcription buffer, 75 mM of each of ATP, UTP, GTP, and CTP, and T7 enzyme mix (MEGAscript™ T7 Transcription Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h and then treated with DNase I at 37 °C for 15 min to remove residual DNA. For the 2′-F RNA library, transcription was performed using 1 µg of DNA template, 5 mM of each of 2′-OH ATP and 2′-OH GTP, and 5 mM of each of 2′-F CTP and 2′-F UTP, along with 10× transcription buffer, 10 mM DTT, and 1 µL of T7 RNA polymerase (Durascribe® T7 Transcription Kit, LGC Biosearch Technologies, Novato, CA). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h and then subjected to DNase I treatment at 37 °C for 30 min. After transcription, RNA products were purified by phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The RNA pellet was resuspended in 10 µL of DEPC-treated water, mixed with 2× RNA loading dye, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and cooled on ice for 5 min. Samples were resolved by electrophoresis on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea at 180 V for 1 h. Target-sized RNA bands were visualized under UV light, excised, and incubated in 500 µL of DEPC-treated water at 37 °C for 3 h to elute the RNA. The eluate was subjected to phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, and the final RNA was resuspended in 20 µL of DEPC-treated water. RNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. The sequence of the RNA library was 5’-GGGAGAGCGGAAGCGUGCUGGGCC-N40-CAUAACCCAGAGGUCGAUGG AUCCCC-3’, where N40 represents equimolar incorporation of each base at each position.

4.4. SELEX procedure

For each selection round, 300 pmol of RNA library was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and immediately cooled on ice for 5 min. Separately, 20 µL of HisPur Ni-NTA magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific) were washed three times with 400 µL of SELEX binding buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM DTT, 1% BSA) supplemented with RNase inhibitor (Labo Pass, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The beads were then resuspended in 200 µL of SELEX buffer and incubated with the denatured RNA at room temperature for 20 min to remove RNA sequences with nonspecific affinity for the beads. After incubation, the RNA–bead mixture was centrifuged and placed on a magnetic rack to collect the supernatant, which contained unbound RNA. This supernatant was incubated with 150 pmol of recombinant NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein at room temperature for 20 min to allow specific RNA–protein complex formation. The complexes were captured by incubation with fresh Ni-NTA beads for 20 min, which werte then washed twice with 400 µL of SELEX buffer to remove unbound RNA. After the final wash, 200 µL of DEPC-treated water was added to elute bound RNA, which was was purified by phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, then resuspended in 10 µL of DEPC-treated water. Reverse transcription was performed using 5× reverse transcription buffer, 10 mM dNTPs, 10 pmol of the SEL 3′ primer (5’-GGGGGGATCCATCGACCTCTGGGTTATG-3’), 200 units of reverse transcriptase (OneScript® Plus Reverse Transcriptase, Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada), and RNase inhibitor. The reaction mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 50 min, then at 95 °C for 5 min to deactivate emzymes. The resulting cDNA was amplified by PCR using DNA polymerase (FIREPol® DNA Polymerase, Solis BioDyne, Tartu, Estonia) with SEL 5′ (5’-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCGGAAGCGTGCTGGG-3) and SEL 3′ primers. PCR conditions were: 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, for 20 cycles. Amplified DNA was transcribed in vitro for the next iterative selection rounds.

4.5. qRT-PCR-Based binding assay for NSP12(P323L/G671S)

To evaluate the binding activity of enriched RNA pools, 60 fmol of RNA from each of the following pools was used: the 15th-round 2′-F RNA, the 11th-round 2′-OH RNA, and the initial RNA library. Each RNA sample was incubated with 12 pmol of NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein at room temperature. After incubation, 20 µL of Ni-NTA magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific) was added, and the mixture was gently mixed at room temperature for 20 min. The beads were then collected using a magnetic rack and washed twice with 400 µL of SELEX buffer to remove unbound RNAs. Bound RNAs were then eluted with 200 µL of DEPC-treated water, phenol extracted, precipitated with ethanol. The recovered RNA was resuspended in 10 µL of DEPC-treated water and used for reverse transcription. Reverse transcription was performed using 5× RT buffer, 10 mM dNTPs, 10 pmol of SEL 3′ primer, OneScript Plus reverse transcriptase (Applied Biological Materials Inc.), and 0.3 µL of RNase inhibitor. The reaction was incubated at 42 °C for 50 min, followed by enzyme inactivation at 95 °C for 5 min and cooling at 4 °C for 10 min. Real-time PCR was conducted using 25 µL of SensiFAST SYBR Hi-ROX premix (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH) and 10 pmol of each of SEL 5′ and SEL 3′ primers. The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 1 s and 60 °C for 20 s. The amount of RNA bound to NSP12 was quantified using amplification curves. Absolute RNA concentrations were calculated by interpolating Ct values from a standard curve generated using serial dilutions of the RNA library.

4.6. RNA-protein pull-down assay

A total of 60 fmol of RNA was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, rapidly cooled on ice for 5 min, and incubated with 6 pmol of NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein, 2 µg of yeast tRNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.3 µL of RNase inhibitor, and 200 µL of SELEX buffer at room temperature for 20 min. The reaction mixture was then incubated with pre-washed Ni-NTA magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific) for an additional 20 min at room temperature with gentle tapping. Beads were collected using a magnetic rack after brief centrifugation (13,000 rpm), and non-specifically bound RNAs were removed by washing twice with 400 µL of SELEX buffer. Bound RNA was eluted by adding 20 µL of DEPC-treated water and 16 µL of phenol, vortexing, and centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The aqueous phase (16 µL) was collected, mixed with an equal volume of 2× RNA loading dye, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and cooled on ice for 5 min. Samples were resolved on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea at 180 V for 1 h. The gel was then transferred onto a 0.45 µm nylon membrane (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) at 200 mA for 1 h in 0.25× TBE buffer at 4 °C and UV cross-linked. For detection, the membrane was incubated in NorthernMax blocking buffer (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 40 °C for 1 h, then hybridized overnight at 40 °C with 10 pmol of a biotin-labeled probe (5’-GGGGGGATCCATCGACCTCT GGGTTATG-3’) synthesized by Bioneer (Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The membrane was then washed for 6x 5 min with Ambion washing buffer, incubated for 30 min with streptavidin-HRP (Novex, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in blocking buffer, and rewashed six times. Detection was performed using ECL solution (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA), and signals were visualized using an Amersham™ ImageQuant™ 800 imaging system (Cytiva).

4.7. Competition assay

To generate 5′-biotin-labeled RNA aptamers, biotinylation was performed by in vitro transcription using DNA templates obtained by PCR. For 2′-F RNA aptamers, 1 µg of PCR-amplified DNA was transcribed in a 20 µL reaction mixture containing 5 mM each of 2′-OH ATP, 2′-F UTP, and 2′-F CTP with 2 mM 2′-OH GTP and 10 mM 5′-biotin-GMP in 10× transcription buffer containing 10 mM DTT and 1 µL of T7 RNA polymerase (DuraScribe® T7 Transcription Kit, LGC Biosearch Technologies). The reaction mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. For 2′-OH RNA aptamers, 1 µg of PCR-amplified DNA was transcribed in a reaction mixtue containing 75 mM of ATP, UTP, and CTP, and 37.5 mM GTP, 10 mM 5′-biotin-GMP, and T7 enzyme mix (MEGAscript™ T7 Transcription Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mixture was then incubated in a 37 °C water bath for 3 h. For the competition assay, 60 fmol of biotin-labeled RNA aptamer was incubated with 6 pmol of NSP12(P323L/G671S), 2 µg of yeast tRNA, 200 µL of SELEX buffer, and unlabeled competitor RNA (either the same aptamer RNA or a non-specific RNA library) at molar excesses of 2×, 20×, and 200×. Binding reactions were performed at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequent steps, including pull-down, washing, and detection, were conducted as described in

Section 4.6.

4.8. Dissociation constant(Kd) analysis

To determine the dissociation constant (Kd), a series of NSP12(P323L/G671S) protein concentrations (0.6 nM, 1.8 nM, 5.4 nM, 16.2 nM, 48.6 nM, 145.8 nM, and 437.4 nM) were prepared and incubated with an aptamer. Subsequent procedures were performed as described in

Section 4.5. The amount of RNA bound to NSP12(P323L/G671S) was quantified by real-time PCR, and the Kd value was calculated using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

4.9. Primer extension assay

Self-priming substrate RNA (5’-[FAM]UUUUCAUGCUACGCGUAGUUUUCUACGCG-3’) was synthesized by Bioneer and designed based on the sequence described in a previous study [

35]. To prepare the substrate RNA, 100 pmol RNA and 10× annealing buffer (0.5 M KCl, 0.2 M HEPES) were mixed and adjusted to 10 μL with DEPC-treated distilled water. The mixture was denatured at 75 °C for 5 minutes and then annealed by cooling slowly to 4 °C over an hour. To form RdRp complex, 50 pmol of NSP12(P323L/G671S), 150 pmol of NSP7, and 150 pmol of NSP8 were incubated together for 1 hour at 4 °C. Subsequently, 10 pmol of annealed substrate RNA, the pre-formed RdRp complex, 5× extension buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM DTT), and 50 pmol of RNA aptamer were combined and incubated for 5 minutes at 37 °C. Nucleotides were then added to a final concentration of 50 mM UTP, CTP, and GTP with 100 mM ATP and incubated for an hour at 37 °C. Total RNA was then extracted using phenol/chloroform, and RNA samples were mixed with 2× RNA loading dye, denatured for 5 minutes at 95 °C, cooled on ice at 4 °C, and then loaded onto a 20% denaturing PAGE gel (1× TBE, 8 M urea). Electrophoresis was performed at 180 V for 2.5 hours, and the gel was visualized using an Amersham™ ImageQuant™ 800 imager (Cytiva).

4.10. Mutagenesis

To generate the NSP12 double mutant (P323L/G671S), site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a commercial mutagenesis service provided by CosmoGenetech (Seoul, South Korea). To obtain the single mutants of NSP12 (P323L or G671S) for subsequent experiments, site-directed mutagenesis was performed. For each reaction, 20 ng of NSP12 wild-type (WT) construct was used as the template along with 10 pmol of P323L forward (5’-AGCACCGTTTTTCCGCTTACCAGCTTTGGTCCG-3’) and reverse primers (5’-CGGACCAAAGCTGGTAAGCGGAAAAACGGTGCT-3’), or G671S forward (5’-ATGGTTATGTGTGGTAGTAGCCTGTATGTTAAA-3’) and reverse primers (5’-TTTAACATACAGGCTACTACCACACATAACCAT-3’). PCR amplification was carried out using 2× CloneAmp HiFi DNA polymerase (Takara Bio) under the following conditions: 98°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, for 35 cycles. The resulting PCR products were treated with 20 units of DpnI restriction enzyme (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) for an hour at 37°C. The digested products were then transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells, and plasmids were isolated using a mini-prep and verified by Sanger sequencing.

4.11. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism 5.0). Results are presented as the means ± SDs of three independent experiments, and statiscal significance was accepted for p-value < 0.05.