Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

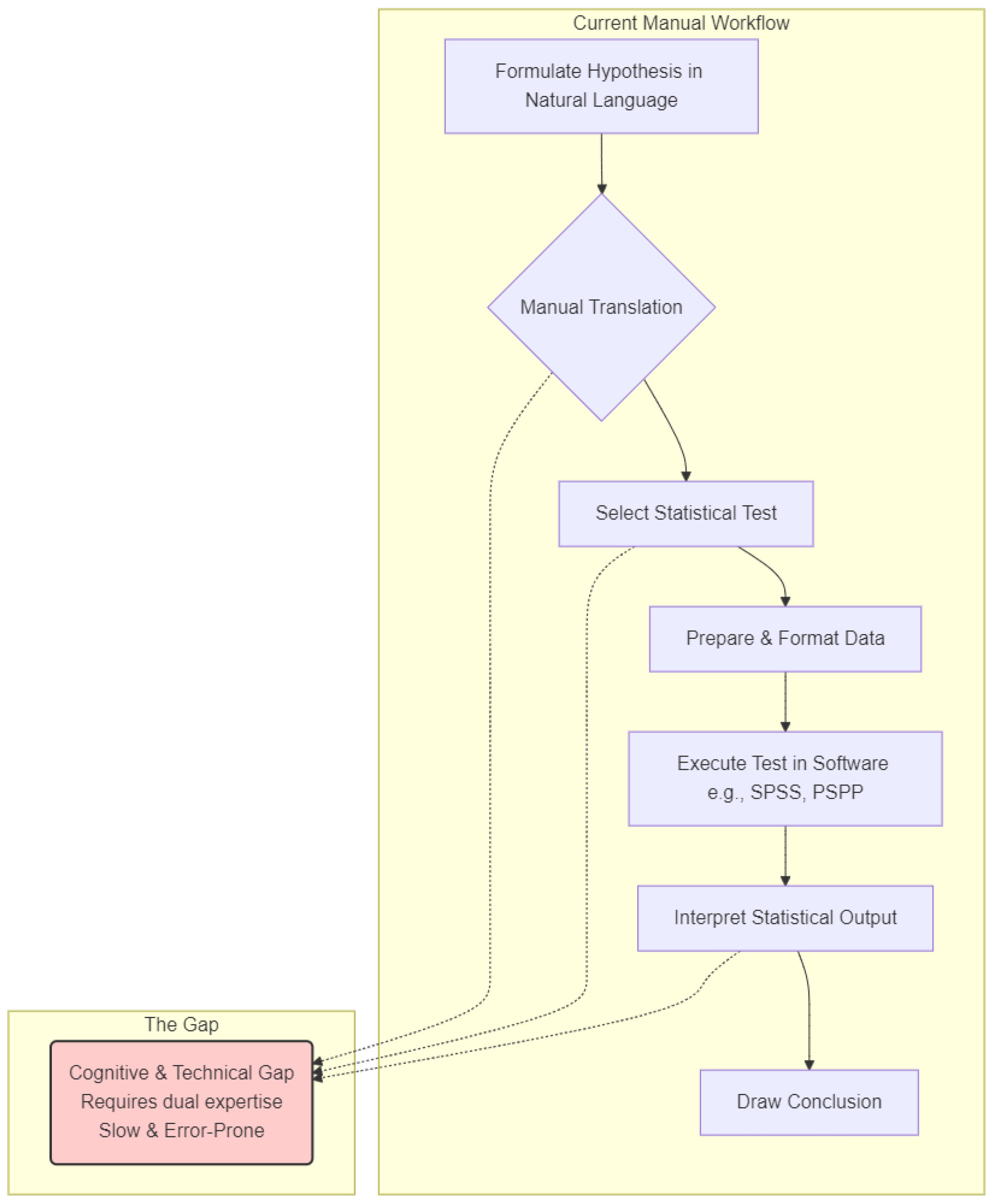

2. Problem Statement and Research Gap

- 2.1.

- Cognitive Load and Expertise Bottleneck: Researchers must possess dual expertise in their own domain and in statistical methodology to correctly select and apply tests.

- 2.2.

- Scalability Issues: The manual process is slow and laborious, making large-scale exploratory research, where hundreds of hypotheses might be evaluated, impractical.

- 2.3.

- Reproducibility Challenges: The manual selection of tests can introduce subjective biases and errors, hindering the reproducibility of findings.

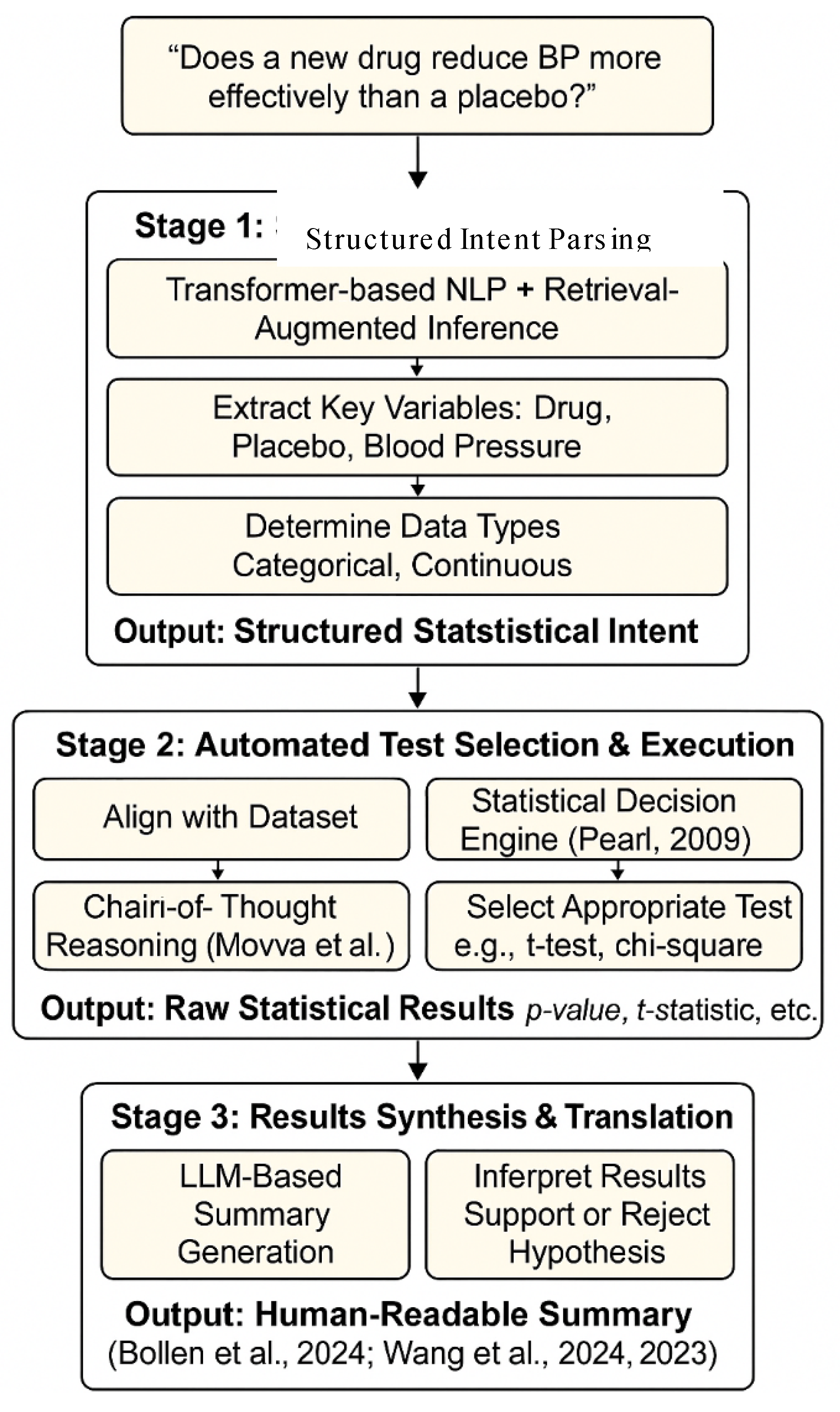

3. Proposed Framework

- 3.1.

- Stage 1: Structured Intent Parsing: The system ingests a user’s hypothesis (e.g., “Does a new drug reduce blood pressure more effectively than a placebo?”). Using retrieval-augmented and transformer-based NLP techniques, it parses this sentence into a structured statistical intent. This involves identifying key components: the variables of interest (drug, placebo, blood pressure), the relationship being tested (causal, correlational), and the nature of the data (An et al., 2024; Devlin et al., 2019).

- 3.2.

- Stage 2: Automated Test Selection and Execution: The structured intent is then used to programmatically align with a provided dataset. A rule-based statistical decision engine, informed by principles of causal inference and statistical theory (Pearl, 2009), automatically selects the most appropriate statistical test. For example, it would identify the blood pressure comparison as requiring an independent samples t-test. This stage leverages modern chain-of-thought reasoning principles to ensure the selection is logical and defensible (Movva et al., 2025). The system then executes the test using standard computational libraries.

- 3.3.

- Stage 3: Results Synthesis and Translation: Finally, the framework translates the raw statistical output (e.g., p-value, t-statistic, effect size) into a human-readable narrative. It generates a summary that explains whether the hypothesis was supported, interprets the meaning of the results in the context of the original question, and notes any relevant statistical details, effectively replicating the summary an expert analyst would provide (Bollen et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023).

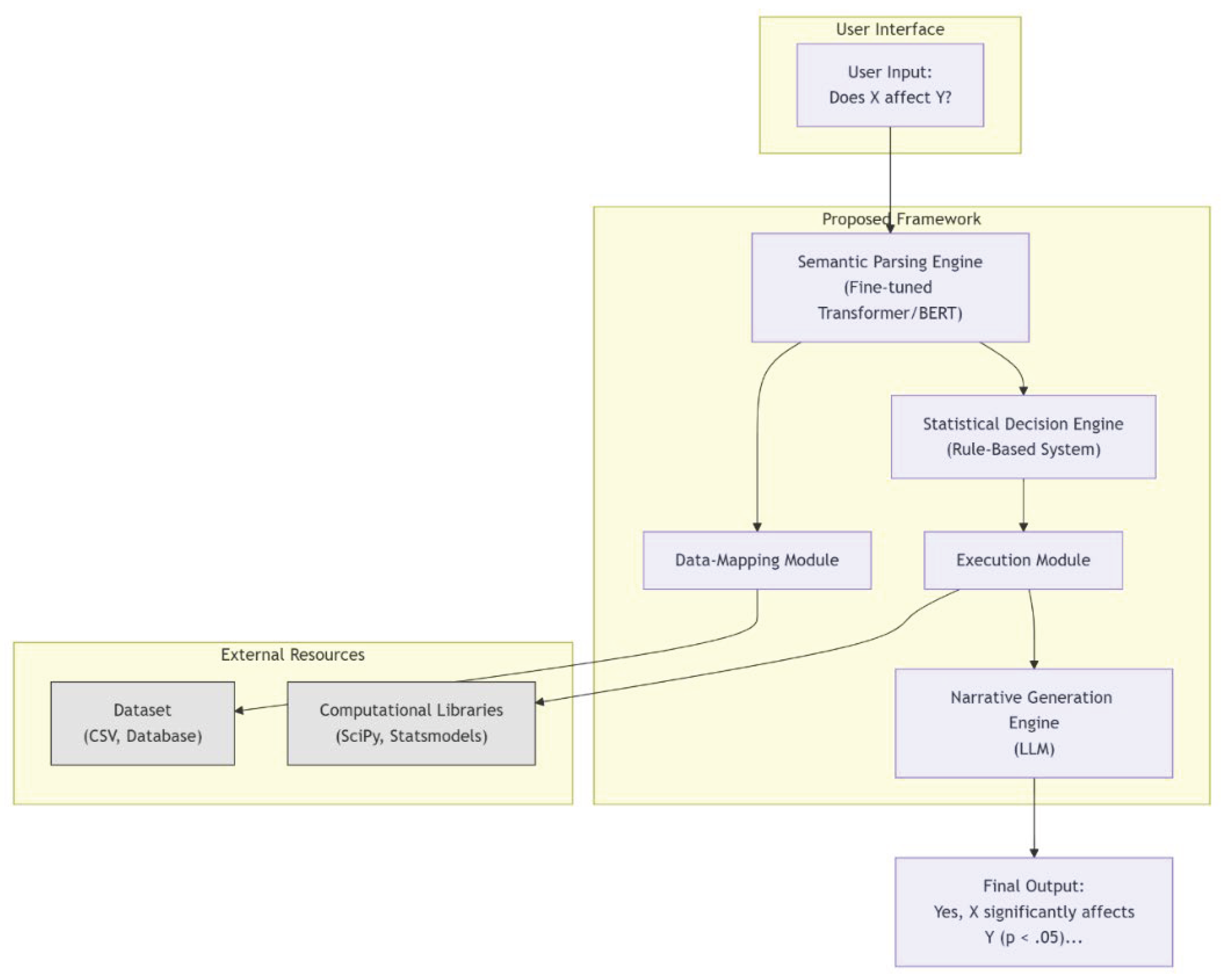

4. Methodology and Architecture Overview

- 4.1.

- Natural Language Interface: A user-facing input layer where hypotheses are submitted.

- 4.2.

- Semantic Parsing Engine: At its core, this engine will utilize a fine-tuned transformer model (e.g., a derivative of BERT) to perform Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Relation Extraction. It will be trained to identify statistical entities (variables, populations) and the relationships between them.

- 4.3.

- Data-Mapping Module: This component will take the parsed entities and map them to the corresponding columns or variables within a structured dataset (e.g., a CSV file or database table).

- 4.4.

- Statistical Decision Engine: This will be a knowledge-based system containing a ruleset derived from statistical theory. The rules will map the characteristics of the parsed intent (e.g., two-group comparison, continuous outcome) to a specific statistical procedure (e.g., scipy.stats.ttest_ind). The engine’s logic will be explicitly designed to handle different types of hypotheses, including those involving causality (Pearl, 2009).

- 4.5.

- Execution Module: This module interfaces with established Python libraries like statsmodels and SciPy to perform the actual calculations.

- 4.6.

- Narrative Generation Engine: An LLM (leveraging the few-shot learning paradigm described by Brown et al., 2020) will be prompted with a template that includes the statistical results. This will enable it to generate a fluent, context-aware summary of the findings.

5. Validation Plan and Future Work

6. Conclusion

References

- Huang, K., Jin, Y., Li, R., Li, M. Y., Candès, E., & Leskovec, J. (2025). Automated hypothesis validation with agentic sequential falsifications. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Movva, R., Peng, K., Garg, N., Kleinberg, J., & Pierson, E. (2025). Sparse autoencoders for hypothesis generation. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wu, J., & Yue, Y. (2025). Robust hypothesis generation: LLM-automated language bias for inductive logic programming. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Liu, Y., Gong, M., Li, J., & He, Y. (2025). A survey on hypothesis generation for scientific discovery in LLMs. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- An, K., Si, S., Hu, H., Zhao, Y., & Liang, P. (2024). Rethinking semantic parsing for large language models: Enhancing LLM performance with semantic hints. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, J., Eftekhar, M., Nelson, D. R., & Eckles, D. (2024). Automating psychological hypothesis generation with AI. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Zelikman, E., Poesia, G., Chi, E. H., & Liang, P. (2023). Hypothesis search: Inductive reasoning with language models. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Dror, R., Peled-Cohen, L., Shlomov, S., & Reichart, R. (2024). Statistical significance testing for natural language processing. Springer. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics.

- Free Software Foundation. (2023). GNU PSPP (Version 2.0.1) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.gnu.org/software/pspp/.

- Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Proceedings of NAACL-HLT 2019, 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., ... & Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901. [CrossRef]

- Chalkidis, I., Fergadiotis, M., Malakasiotis, P., Aletras, N., & Androutsopoulos, I. (2021). Legal-BERT: The muppets straight out of law school. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Findings, 2898–2904. [CrossRef]

- Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2023). Speech and language processing (3rd ed.). Draft manuscript. Stanford University. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/.

- Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., ... & Duchesnay, É. (2011). Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12, 2825–2830. Available online: http://www.jmlr.org/papers/v12/pedregosa11a.html.

- Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, reasoning and inference (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).