1. Introduction

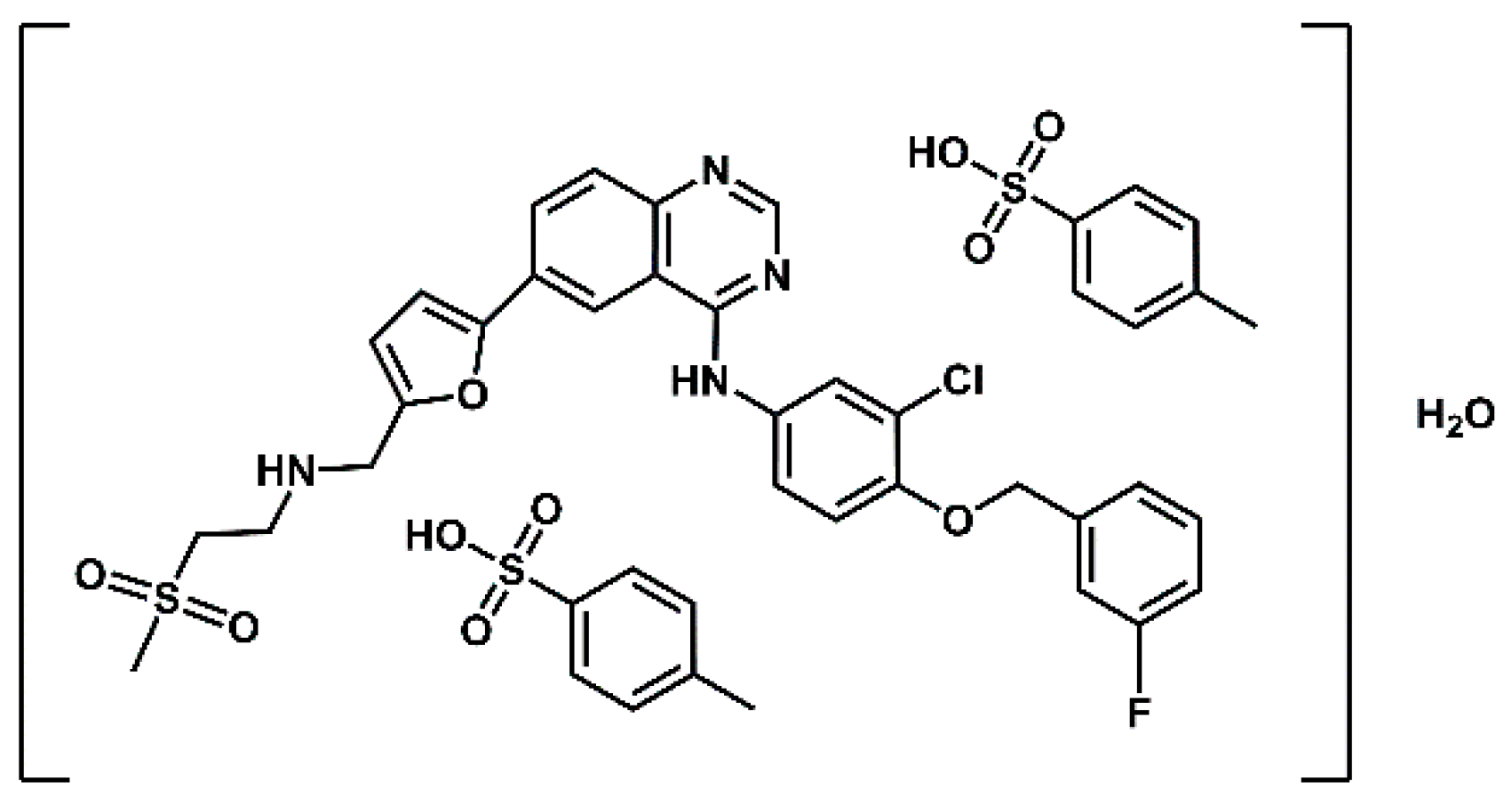

Lapatinib (GW572016) is a small molecule developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) that belongs to the class of kinase inhibitors. Its structure is based on a 4-anilinoquinazoline core, which serves as the principal hinge-binding motif responsible for interaction with kinase domains. Lapatinib is a targeted therapeutic agent indicated for the treatment of advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer [

1,

2] in patients who have previously received standard chemotherapeutic regiments [

3,

4]. Lapatinib is the active substance of the drug Tykerb ( marketed as Tyverb in Europe), formulated and administered as lapatinib ditosylate monohydrate (

Figure 1). It is a selective dual tyrosine kinease inhibitor, targeting both the

Epidermal

Growth

Factor

Receptor (EGFR) and the

Human

Epidermal Growth Factor

Receptor 2 (HER-2) [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The predominant elimination pathway of lapatinib is via the faces, accounting for more than 90% of the administered dose, while renal excretion plays only a minor role [

9]. Lapatinib in combination with capecitabine (Capecitabine Glenmark) received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007, based on the results of a phase III clinical trial [

10,

11]) and from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2008 for the treatment of patients with advanced and/or metastatic HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer who have experienced disease progression following prior treatment with anthracyclines, taxanes, and trastuzumab [

12]. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the combination of lapatinib and trastuzumab has a synergistic effect on HER-2 overexpressing breast cancer cells, significantly enhancing apoptosis [

13]. Further investigations using the HER-2-positive SKBR3 breast cancer cell line have shown that the combination of lapatinib and radiotherapy may augment the efficacy of radiotherapy. Specifically, pretreatment with lapatinib increased radiation-induced cell death in HER-2-positive breast cancer cells, while no radiosensitizing effect was not observed in HER-2-negative breast cancer cells or in normal human astrocytes [

14].

In addition to blocking HER receptors, Lapatinib has the ability to inhibit truncated variants of HER2, known as p95HER2 receptors, which lack the extracellular binding domain recognized by trastuzumab but retain active kinase function [

12,

15]. This property provides lapatinib with therapeutic potential in trastuzumab-resistant tumors. Furthermore, lapatinib has been reported to interfere with signalling cascades activated by the Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor (IGF-1R). Inhibition of this pathway may contribute to the immediate suppression of cancer cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis, further broadening the drug’s antitumor activity [

16].

Accurate assessment of HER-2 expression plays an essential role in cancer diagnosis and treatment. HER-2 overexpression serves as a clinically relevant biomarker functioning both as a prognostic factor—providing information about the likely course of the disease—and as a predictive factor—indicating the likelihood of response to targeted therapy. Determining HER-2 status enables effective patient stratification for HER2-directed therapies, including trastuzumab (Herceptin), a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, and lapatinib (Tykerb), a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor [

17]. Currently, several methods are employed to assess the level of HER-2 overexpression. The most widely used is immunohistochemistry (IHC), which is inexpensive, broadly accessible, and relatively simple to perform. However, its accuracy is limited, as the evaluation depends on the subjective assessment of staining intensity, which can complicate interpretation [

18,

19]. A more precise, though costlier, approach is fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which enables quantification of HER-2 gene copy number and provides a reliable assessment of gene amplification status [

18,

19,

20,

21]. An alternative method, chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH), allows for the visualization of specific DNA or RNA sequences within cells or tissues using a standard bright-field microscope. This makes CISH a practical substitute for FISH, which requires access to specialized fluorescence microscopy equipment [

20,

21]. All of these techniques rely on the acquisition and analysis of biopsy samples.

A promising competitive non-invasive alternative to biopsy-based methods for the visualization and quantification of Her-2 receptor overexpression in heterogeneous tumours, compared to the methods mentioned above, is the use of diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals containing lapatinib as a targeting vector. Depending on the radionuclide employed, radiopharmaceutical can be either diagnostic (containing radionuclides that emit gamma or beta plus radiation suitable for imaging) or therapeutic, incorporating radionuclides that emit alpha, beta minus particles, or Auger electrons selectively destroy cells overexpressing the appropriate/target receptor.

There are numerous reports in the literature on radiopharmaceuticals acting on HER family receptors [

22,

23,

24] and the publications cited in them]. HER-2-targeted radiopharmaceuticals [

23,

25] discussed in ref. [

23] are

monoclonal antibodies (trastuzumab and pertuzumab),

antibody fragments (Fab and F(ab’)

2 antibody fragments of trastuzumab and pertuzumab),

nanobodies (2Rs15d, NM-02 and NM-302),

affibodies (ZHER2:342 and its derivatives: ABY-002, ABY-025, ABH2, HPark2, GE-226, ADAPT6) and

peptides (KCCYSL, MEGPSKCCYSLALASH, GTKSKCCYSLRRSS, CGGGLTVSPWY, CSSSLTVSPWY, SSSLTVPWY, FCGDFYACYMDV, YLFFVFER and its retro-inversion analogue, KLRLEWNR and A9 containing a fragment of trastuzumab (Fab)) labelled with different radionuclides (Tc-99m, In-111, I-123, I-124, F-18, N-13, C-11, Cu-64, Ga-68 and Zr-89). HER-3-targeted radiopharmaceuticals [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] discussed in ref. [

24] are

monoclonal antibodies (Mab#58, GSK2849330, lumretuzumab (RG7116, RO5479599), mAb3481, duligotuzumab (MEHD7945A)),

nanobody MSB0010853 (binding to two different HER-3 epitopes),

affibodies (Z

08698 and Z

08699, (HE)

3-Z

08698),

peptides (CLPTKFRSC, HER3P1) and the small

molecule AZD8931, labeled with different diagnostic radionuclides (Tc-99m, In-111, Ga-68, Co-55, Co-57, Zr-89, C-11). HER-3-targeted cancer therapy may be an alternative to the anti-EGFR and anti-HER-2 resistance therapies [

23]

The aim of this review is to compile and discuss current literature on the chemical and biological aspects of radiopreparations based on the lapatinib molecule with particular emphasis on their potential application in the diagnosis and therapy of cancers characterized by HER-2 overexpression.

3. Radionuclide-Labelled Lapatinib Agent

The use of radioactively labeled kinase inhibitors provides the unique opportunity in oncology, neurology and neuro-oncology to quantify kinase density in tumors, assess brain penetration and measure kinase levels in normal and pathological brain tissue. While numerous studies (both original research and reviews) have reported on ligands targeting HER family receptors labeled with various radionuclides [

22,

23], far fewer publications focus on radiolabelled protein kinase inhibitors [

24,

35], and even more limited are studies specifically investigating radiolabelled lapatinib, highlighting a gap in the current literature [

35,

36,

37,

38,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

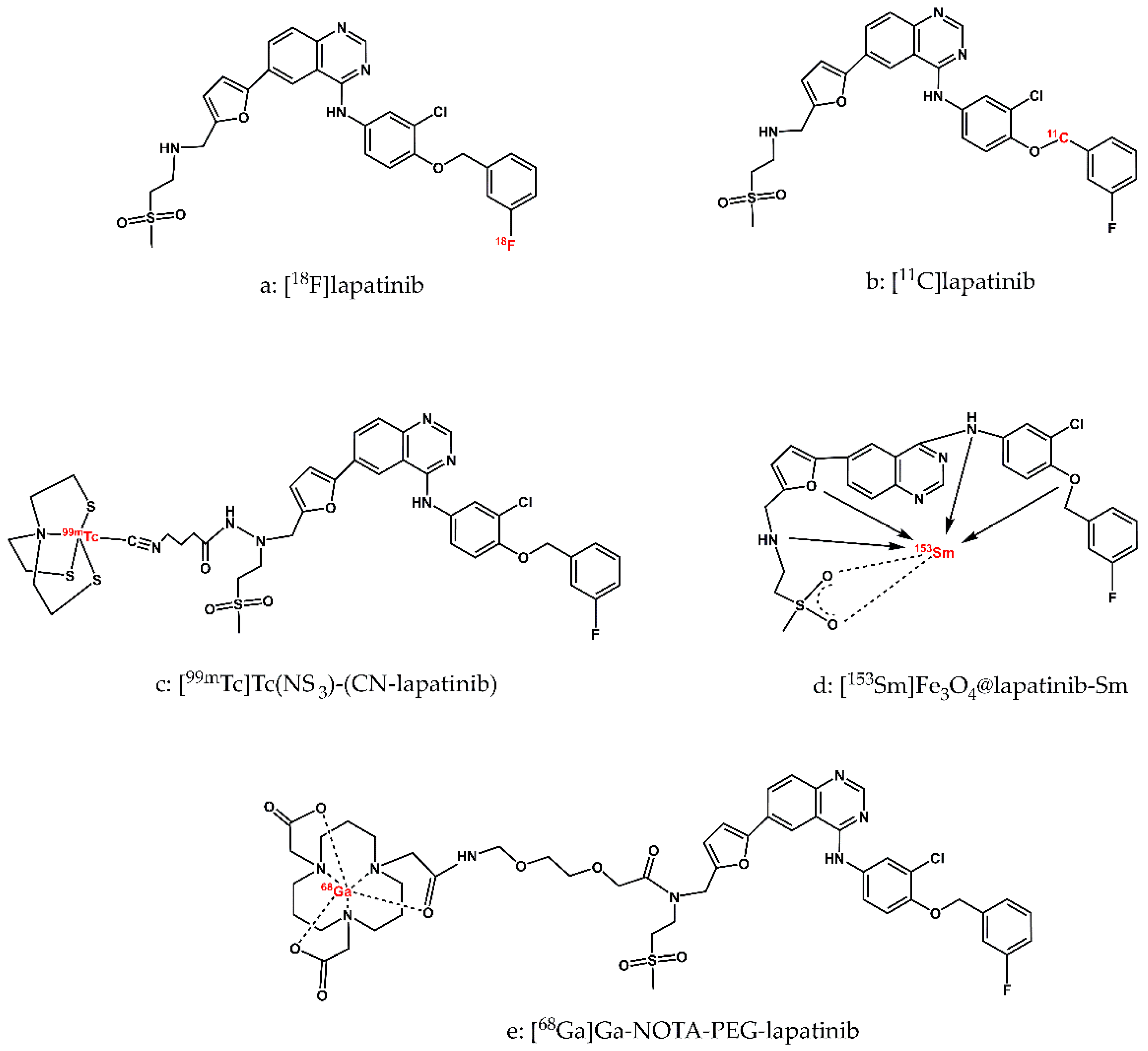

The first potential radiopharmaceuticals based on lapatinib were radiopreparations labelled with non-metallic, ‘organic’, short-lived diagnostic radionuclides F-18 and C-11 as well as long-lived therapeutic radionuclide C-14. The short half-lives of F-18 (110 min) and C-11 (20 min) require the development of rapid and efficient synthetic methods for these radiopreparations. However, the obtained radiopreparations [

18F]lapatinib and [

11C]lapatinib (

Figure 2-a, b) retain the exact chemical structure of the parent molecule, lapatinib. This structural fidelity ensures that PET imaging studies using these radiolabeled derivatives accurately reflect the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and biological behavior of lapatinib in vivo.

The multi-step, manual radiosynthesis of F-18-labeled lapatinib ([

18F]lapatinib,

Figure 2-a) was described in detail by Basuli and colleagues in 2011 [

36]. The radiotracer was obtained with a radiochemical purity exceeding 98%. The synthesis was sufficiently short to allow production of [

18F]lapatinib in quantities adequate for PET imaging, as well as for physicochemical and biological studies of the radiopreparation. However, the authors did not report any further physicochemical or biological evaluation of the synthesized radiocompound, leaving its

in vivo behaviour and suitability for imaging uncharacterized.

Several years later, Nunes et al. developed and described in detail a novel, also multi-step procedure for the routine preparation of

[18F]lapatinib for clinical trials [

37]. This method employed a pinacolyl arylboronate precursor and copper-mediated nucleophilic

18F-fluorination reaction. This synthesis proved to be simpler, but the final radiochemical yield was low.

The synthesis of C-11-labeled lapatinib (

[11C]lapatinib,

Figure 2-b) was reported by Saleem et al. [

38]. The radiotracer was obtained with a useful radiochemical yield (RCY) and sufficiently high specific activity (SA).

In vivo studies have shown that [

11C]lapatinib is stable and accumulates differentially in healthy brain tissue and brain metastasis, thereby enabling the visualization of brain tumours. The authors also verified the hypothesis put forward several years earlier by Gril et al. [

39] that lapatinib may prevent breast cancer metastases to the brain if treatment is initiated at an early enough stage of the disease. They also investigated whether pretreatment with therapeutic doses of lapatinib could enhance brain uptake of [

11C]lapatinib. However, PET studies demonstrated that therapeutic doses of lapatinib did not increase brain penetration of the radiopharmaceutical, suggesting that prophylactic administration of lapatinib to prevent brain metastases in breast cancer patients may not be effective. In conclusion, lapatinib may play a role in the treatment of established brain metastases, but not in their prevention.

In vitro and in vivo biological studies of lapatinib labelled with the therapeutic carbon radionuclide C-14 using

[14C]lapatinib were reported by Taskar et al. [

40]. Generally, oral administration lapatinib was shown to distribute efficiently to multiple organs. However, due to the protective effect (efflux transport mechanism) of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), brain uptake of lapatinib was limited to less than 10% of the plasma levels. In case of brain metastases, the blood-tumour barrier (BTB) is partially compromised, which further results in variable passage of lapatinib across the BTB. The authors investigated the ability of lapatinib to reach therapeutic concentrations of the drug in the central nervous system (CNS). The radiocompound was administered either orally (100 mg/kg) or intravenously (10 mg/kg) to mice with MDA-MD-231-BR-HER2 breast cancer brain metastases. Orally, the radiopreparation was administered in a vehicle formulation consisting of 0.5% hydroxypropylmethylcellulose with 0.1% Tween 80 in water, and in the case of intravenous administration, the radiopreparation was administered in a DMSO solution diluted to 30% with 0.9% NaCl. [

14C]lapatinib circulated for 2 or 12 hours following oral administration and for 30 minutes following intravenous administration. The authors found that the radiopreparation was completely stable during this period – more than 98% of the radioactive tracer remained intact, and that no resistance to the drug lapatinib was observed in tumor cells isolated from brains treated with lapatinib. After the circulatory period, the animals were sacrificed and the brain, blood and plasma samples, as well as selected other tissues (e.g. liver, lungs, heart, kidneys) were collected to measure the accumulated radioactivity. The authors found that lapatinib concentrations in brain metastases following oral administration were on average 7-fold greater than in healthy brain after 2 hours and 9 times higher after 12 hours. In the case of intravenous administration of the radiopreparation, the accumulation of radiotracer in brain metastases was on average 3.2-fold greater compared to the normal brain. Based on the experimental results, the authors concluded that: (i) the concentration of

14C-lapatinib in brain metastases, as opposed to the normal brain, was generally clearly elevated, highly variable and highly heterogeneous; (ii) there were no differences in the distribution of lapatinib between the center of the metastasis and its periphery; (iii) in sites distant from the metastases, the concentrations of the radioactive agent were low and homogeneous; (iv) for all brain metastases studied, [

14C]lapatinib uptake varied both within and between lesions; (v) in the great majority of brain metastases studied (>80%), average

14Clapatinib concentration was <10-20% of that in peripheral metastases; (vi) only in a small group of brain metastases studied (about 17%) did lapatinib concentrations in the brain approach those in peripheral tumors (for effective therapy, the distribution of lapatinib should be comparable to the distribution in systemic metastases); (vii) BTB permeability is responsible for the limited accumulation of radiopharmaceuticals in brain metastases.

In summary, the results of the work performed by Taskar’s research group indicated that the distribution of lapatinib to metastases in the central nervous system is limited and insufficient, primarily due to the permeability of the BTB.

One of the first reports on lapatinib labelled with the metallic radionuclides is the publication by Gniazdowska et al. [

41]. The authors designed the synthesis of the

[99mTc]Tc(NS3)(CN-lapatinib) radioconjugate (

Figure 2-c) and performed studies on the physicochemical and biological properties of the obtained radiopreparation from the point of view of its use as a diagnostic radiopharmaceutical for imaging the overexpression of the HER-2 receptor. The diagnostic radionuclide cation Tc-99m was complexed by the tetradentate tripodal chelator (tris(2-mercaptoethyl)-amine; 2,2’,2’’-nitrilotriethanethiol, NS

3) and the monodentate isocyanobutyric acid (CN, as a bifunctional coupling agent, CN-BFCA), forming a complex with a trigonal bipyramidal structure. To verify the obtainment of the radioconjugate [

99mTc]Tc(NS

3)(CN-lapatinib) synthesized on the n.c.a. scale, a non-radioactive ‘cold’ reference compound Re(NS

3)(CN-lapatinib) was synthesized on the milligram scale and examined using various analytical methods (EA, NMR, MS). The [

99mTc]Tc(NS

3)(CN-lapatinib) radioconjugate was obtained with high yield > 97%, high purity > 98%, and with specific activity within the range 25÷30 GBq/mmol. Stability studies performed in the presence of a 1000-fold molar excess of histidine and cysteine and in human serum showed that the radioconjugate does not undergo ligand exchange reactions or enzymatic biodegradation. The lipophilicity value of [

99mTc]Tc(NS

3)(CN-lapatinib) determined in n-octanol/PBS buffer, pH 7.4, was 1.24 ± 0.04. In biological studies using a human ovarian cancer cell line (SKOV-3), the authors determined a B

max value of 2.4 ± 0.3 nM, corresponding to an approximate number of 2.4 x 10

6 binding sites per cell, a dissociation constant K

d of 3.5 ± 0.4 nM, and an IC

50 value of 41.2 ± 0.4 nM. An in vivo multi-organ biodistribution study in an animal model showed that clearance of the [

99mTc]Tc(NS

3)(CN-lapatinib) radioconjugate occurs via the hepatic and renal pathways to a comparable extent. In conclusion, the authors emphasized that the [

99mTc]Tc(NS

3)(CN-lapatinib) radioconjugate can be easily synthesized in hospital laboratories from previously prepared lyophilized kit formulations and that this radiopreparation can be considered a promising diagnostic radiopharmaceutical for patients suffering from Her-2 breast cancer and a useful tool for patient stratification for the purpose of so-called personalized therapy.

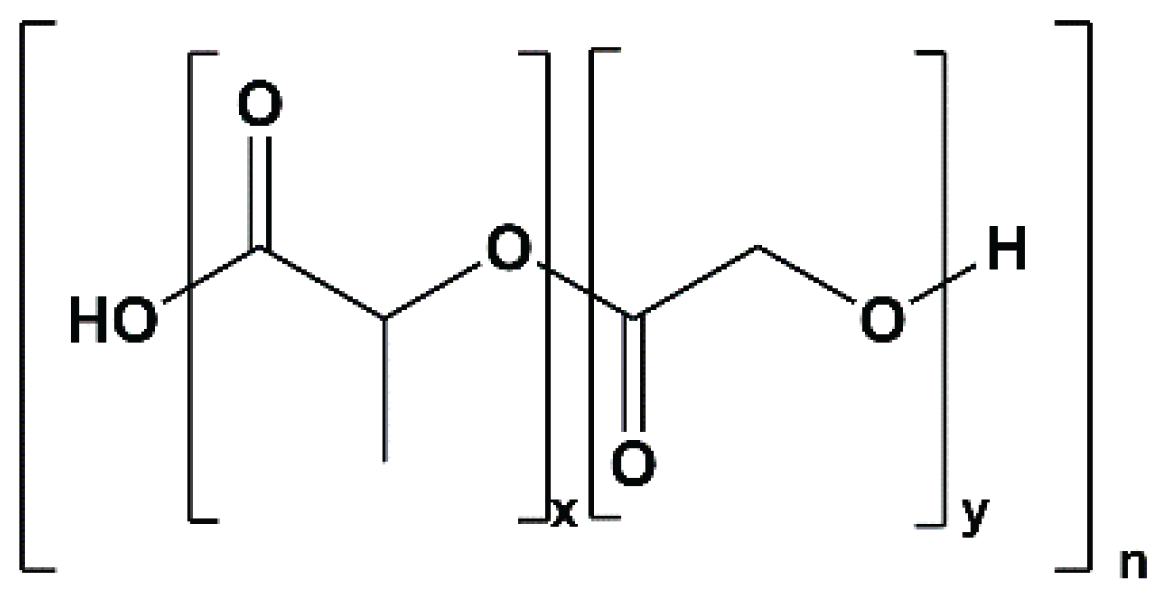

Nearly a decade later, Gokulu et al. [

42] reported technetium-99m labelling of lapatinib and its derivative – a poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) encapsulated lapatinib formulation. Until this study, no reports had desribed imaging using a radioactively labelled encapsulated lapatinib derivative. The novel radiopreparations

[99mTc]Tc-lapatinib and

[99mTc]Tc-lapatinib-PLGA were obtained by the so-called direct labelling method, involving reduction of sodium pertechnetate ([

99mTc]NaTcO

4 eluted from a

99Mo/

99mTc generator) with SnCl

2 as a reducing agent. To characterize the newly obtained radioconjugates, the authors relied solely on thin-layer radiochromatography (TLRC), which was applied for quality control, assessment of radiolabeling efficiency, and stability testing. The chromatographic separation was carried out using an n-butanol/double-distilled water/acetic acid mixture (4:2:1) as the mobile phase. After obtaining the radioconjugates, the authors tested their in vitro bioaffinity using MDA-MB-231 (human breast), HeLa (cervical) and MDAH-2774 (endometrioid ovarian cancers) cell lines. The experiments showed that the radiochemical efficiency of lapatinib and its derivative lapatinib-PLGA labelling was 98.14 ± 1.12% and 97.68 ± 0.93%, respectively. Both [

99mTc]Tc-lapatinib and [

99mTc]Tc-lapatinib-PLGA radioconjugates were reported to be more than 90% stable for 4 hours, with lipophilicity (logP) values −2.79 ± 0.01 and −1.09 ± 0.03, respectively, determined in n-octanol/pH 7 buffer systems. The bioaffinity of obtained [

99mTc]Tc-lapatinib and [

99mTc]Tc-lapatinib-PLGA radiopreparations was tested in vitro using MDA-MB-231, HeLa, and MDAH cell lines by determining the time-dependent cellular uptake of radiocompounds in the cell lines. Both radiopreparations showed higher uptake in HeLa and MDAH cells (approximately 15%), whereas in the MDA-MB-231 cell line, uptake remained low and comparable to that of free [

99mTc]Tc (around 5%).

As the authors of this review, we feel obliged to draw the reader’s attention to numerous experimental shortcomings in the work of Gokulu et al lub: (i) the TLRC analyses used to demonstrate the preparation of [

99mTc]Tc-lapatinib and [

99mTc]Tc-lapatinib-PLGA radioconjugates are completely unreliable (Figure 5 in the article: “TLRC chromatograms of [

99mTc]NaTcO

4, [

99mTc]TcO

2 should be here instead of [

99mTc]TcO

4, [

99mTc]Tc-LPT and [

99mTc]Tc-LPT-PLGA)”. The TLRC chromatograms of [

99mTc]NaTcO

4 and [

99mTc]Tc-LPT are almost identical (the analyses were performed under analogous conditions), so, on what basis do the authors believe that these are two different compounds? (ii) direct labelling with Tc-99m, without additional coligands, cannot account for the dramatic reduction in lipophilicity from logP 5.1 (or 6.17, as reported by the authors) to −2.8; (iii) the reported trend in logP value between [

99mTc]Tc-LPT and [

99mTc]Tc-LPT-PLGA radiopreparations is unlikely – encapsulation of lapatinib in a PLGA nanoparticle structure (

Figure 3) containing many oxygen atoms (each with 2 lone electron pairs) would be expected to increase hydrophilicity (i.e., reduce logP), not increase lipophilicity (logP of −2.8 to −1.09) as claimed; (iv) no explanation was provided regarding the mode of stable coordination of the

99mTc cation within the lapatinib nanoformulation (LPT-PLGA); (v) it is unclear whether stability studies were performed on purified radioconjugates or directly on crude reaction mixtures, which raises concerns about the reliability of the reported stability data.

The significant shortcomings mentioned above make the experimental results presented in this article unreliable, which will be discussed in more detail in the conclusions section.

Almost simultaneously, two further reports on lapatinib labelling with the metallic radionuclides Sm-153 [

43] and Ga-68 [

44] appeared in the literature.

Pham et al. presented and optimized the synthesis of

[153Sm]Fe3O4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles, described a series of analytical techniques used to characterize the physicochemical properties of both the synthesized Fe

3O

4@lapatinib nanoparticles and the new radiopreparation. Additionally, they evaluated the in vivo biocompatibility and systemic toxicity of the radiocinjugate in a mouse model [

43]. [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles consisted of an Fe

3O

4 core connected by hydrogen bonds to the surrounding lapatinib layer and Sm-153 radionuclides as a result of the formation of a complex between

153Sm

+3 cation and lapatinib (

Figure 2-d). The use of gamma-emitting radionuclide

153Sm enables the use of the radiopreparation for imaging by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and radiation dose assessment, while beta-minus radiation provides a targeted therapeutic effect on cancer cells. The size of [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles measured by DLS in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was in the range of 10 nm to 100 nm (with an average value of 27.4 nm), which makes it suitable for the construction of targeted drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. The radiochemical purity of [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles (measured by gamma spectroscopy) was 100% for the gamma-emitting radionuclide. Stability studies of radiolabelled nanoparticles were conducted in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (0.02 M, pH 7.4) and human serum, as well as sterility assessment were performed using FTM (liquid thioglycolate medium) and SCDM (soybean casein digestion medium) over a 14-day observation period. The results showed that the radiopreparation maintained stability and sterility throughout the study, fully meets the requirements for radiopharmaceuticals. The authors investigated in vivo the acute toxicity of [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles (in the dose range from 20 to 100 mCi/kg) in animal model (mice) using a single-dose toxicity test method and selected a dose of 20 mCi/kg as an effective and completely safe dose for further experiments on mice. At higher doses, temporary changes in some blood parameters began to occur immediately after nanoparticle injection, but most of these parameters returned to baseline levels within a 14-day observation period. The biodistribution of [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles was investigated in BT474 (HER2+) xenograft female mice (BALB/c). At selected time points (up to 48 hours post-injection), the authors determined the accumulation of radiolabelled nanoparticles in selected organs, including blood, heart, lungs, liver, stomach, spleen, kidneys, urinary bladder, and intestines. The results indicated that 0.5 hours after injection the radiolabelled nanoparticles were predominantly localized in the liver. Over time, nanoparticle accumulation increased in the blood, liver, stomach, spleen, kidneys, urinary bladder, and intestines, while accumulation in the heart and lungs gradually decreased. After 48 hours, the overall accumulation of [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles decreased in most organs, likely due to a combination of radioactive decay of

153Sm and progressive excretion of the radiopreparation from the body. The significant accumulation in the kidneys and urinary bladder may indicate that [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm nanoparticles are excreted primarily through the urinary tract. The authors noted a rapid increase in the tumor/blood accumulation ratio of studied radiolabeled nanoparticles after 48 hours, which may be due to its higher affinity for tumor cells and increased specificity of [

153Sm]Fe

3O

4@lapatinib-Sm in the tumor microenvironment, which may be the basis for designing targeted anti-cancer therapies using this radiotracer.

Recently, Gong et al. published a report describing, among other aspects, the labelling of lapatinib with the radionuclide Ga-68 [

44]. In this study, the authors present the potential of a multimodal approach to cancer imaging that combines PET and near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging at the same time. The PET probe was lapatinib labelled with the radionuclide Ga-68, while the NIR probe was the NIR LP-S fluorescent agent, also based on lapatinib. According to the authors, this synchronized dual-probing strategy, based on the same targeting molecule with high affinity for HER-2-overexpressing cells, may provide an effective diagnostic tool for detecting HER-2-positive breast cancer or preoperative PET imaging, as well as for fluorescence-guided tumour surgery. The study included a detailed characterization of the physicochemical and biological properties of both the radiopharmaceutical probe [

68Ga]Ga-NOTA-lapatinib and the fluorescent probe NIRF LP-S underscoring the potential of this multimodal approach in future clinical applications.

Before designing the radiopharmaceutical probe [

68Ga]Ga-NOTA-lapatinib, the authors performed a series of preliminary studies. Based on the assumption that the attachment of a PEG linker to the NOTA group would not significantly interfere with receptor interactions, they performed molecular docking analyses using the crystallographic structures of the EGFR (PDB-ID 4G5J) and HER-2 (PDB-ID 3PP0). The docking studies evaluated the interactions of both lapatinib and the NOTA-lapatinib conjugate within the ATP-binding pockets of the receptors. The calculated binding energies of lapatinib and the NOTA-lapatinib conjugate with EGFR receptor were -9.2 kcal/mol and -9.0 kcal/mol, respectively, and with the HER-2 receptor -10.64 kcal/mol and -10.05 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating that the structural modification did not substantially impair binding affinity. The

[68Ga]Ga-NOTA-PEG-lapatinib radioconjugate synthesized by the authors consisted of a lapatinib molecule conjugated with polyethylene glycol (PEG2, which increased aqueous solubility) and the chelator NOTA, which formed a complex with the

68Ga radionuclide (

Figure 2-e). Labelling of the NOTA-PEG-lapatinib conjugate with Ga-68 and purification of the resulting radioconjugate were completed in less than 30 minutes, and the radiochemical purity of the radiopreparation was greater than 95%. (as confirmed by TLC and/or HPLC) The cytotoxicity of lapatinib, the NOTA-lapatinib conjugate, and the LP-S probe was assessed using the L02 cell line and the MTT assay. The results confirmed low biological toxicity and high biological safety of the [

68Ga]Ga-NOTA-lapatinib radioconjugate. In addition, the biological stability of the radiopharmaceutical was demonstrated by HER-2 immunostaining of HepG2 tumors in HepG2 tumor-bearing mice following administration of the radiotracer. The H&E results showed that no organ damage occurred after injection of [

68Ga]Ga-NOTA-PEG-lapatinib (and also LP-S), confirming the biological safety of the radiopharmaceutical probe (and the fluorescent probe also). Cellular studies of [

68Ga]Ga-NOTA-PEG-lapatinib radioconjugate conducted using HepG2 and K562 cell lines (characterized by varying levels of HER-2 expression) demonstrated rapid uptake of the radiotracer by HepG2 cells with minimal uptake observed in K562 cells. These results confirm the high receptor affinity and selectivity of the radiotracer for HER-2-overexpressing cells. Biodistribution studies of the [

68Ga]Ga-NOTA-PEG-lapatinib radioconjugate were performed in mice bearing HepG2 and K562 tumours. Accumulation of the radioconjugate in all examined organs was significantly higher in the HepG2-bearing group compare with the K562-bearing group, consistent with the different levels of HER2 expression. However, the tissue uptake data (%ID/g), determined 1 hour after administration, revealed substantial non-specific accumulation of the radioconjugate in the liver and intestines. In addition, lapatinib is characterized by a relatively long circulation time in blood of 14.2 hours, which means that the radiopreparation reaches the maximum concentration approximately 4 hours post-injection. This pharmacokinetic profile is suboptimal for imaging with

68Ga, whose physical half-life is only 68 minutes, which is already almost four half-lives of the radionuclide at the time lapatinib reaches its maximum concentration in the blood. The authors acknowledged these limitations and proposed two potential improvements: the incorporation of a longer PEG fragment to decrease the lipophilicity of the radioconjugate and the use of a radionuclide with a longer half-life to better match the pharmacokinetics of lapatinib.