1. Introduction

Non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC), primarily squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC), represent the most common types of skin malignancy globally [

1,

2], with around 80% affecting the head and neck region [

3]. Although early diagnosis generally leads to good oncological outcomes, lesions on the face pose additional challenges, extending beyond cosmetic concerns to impact physical function, mental health, and overall quality of life. Although dermatologists frequently manage minor excisions and local flaps, more complex cases require surgical excision and reconstruction by plastic surgeons. While achieving clear oncological margins remains the primary goal, successful reconstruction demands a comprehensive, patient-centered approach that also addresses functional restoration, psychological resilience, and sustained quality of life [

4].

Reconstructive options following excision include direct suturing (DS), skin grafts, flap surgery (FS), or free flaps. In reconstructive plastic surgery, FS are often preferred for defect closure—when primary closure are inadequate—due to their reliable vascular supply and robust tissue viability. However, they may also present challenges such as excessive bulk, color mismatch, and noticeable scarring [

5]. While surgical success has traditionally been measured through complication rates and aesthetic outcomes, an increasing pa-tient-oriented movement highlights the need to consider how reconstructive choices impact patients—encompassing physical comfort, emotional adaptation, and social integration [

6].

Scar assessment are key in post-reconstructive evaluation, but discrepancies between clinical assessments and patient-reported outcomes persist. While surgeons may focus on objective measures such as scar texture and symmetry, patients prioritize factors such as discomfort, tightness, and self-consciousness in social settings [

7].

This study investigates the patient reported outcomes one year after removal of NMSC of the face and closure with DS or FS. We wish to investigate the impact on quality of life after facial surgery, as there are limited literature available in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

The study investigates patient-reported satisfaction with facial appearance and quality of life one year after facial non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) surgery, assessed with FACE-Q Skin Cancer questionnaire, a validated com-prehensive patient-reported outcome instrument specifically designed to measure outcomes in patients undergoing facial aesthetic and reconstructive procedures and evaluating quality of life and satisfaction of patients that have undergone treatment for skin cancer on the face [

8]. The questionnaire consists of seven different components: cancer worry, appearance, appearance-related distress, appraisal of scars, satisfaction, information and sun protection behavior. Each module can be used independently, and scores are calculated based on patient responses through conversion tables to transform raw scores into standardized 0-100 scales, facilitating comparison and interpretation. Higher scores generally indicate greater levels of worry, distress or adverse effects or higher satisfaction and better outcomes de-pending on the module. By incorporating the FACE-Q questionnaire into this study, we can systematically evaluate and compare the subjective experiences of patients [

9,

10].

The study are conducted as a single-center prospective cohort study at the Department of Plastic and Breast Surgery, Zealand University Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Registry of Region Zealand, Denmark (protocol code 098-2020; approval date 22 October 2020). The department are a high-volume center specializing in skin cancer treatment and reconstructive surgery. The study included patients undergoing facial NMSC excision and reconstruction between June 1, 2021, and June 20, 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Inclusion criteria required patients to have a histopathological confirmed BCC or SCC in the facial regions; temple, forehead, periorbital area, cheeks, nose, lips/perioral area, and chin, provided that the lesion was not recurrent. The follow-up period was one year +/- one month. Patients underwent either NMSC removal closed with DS or reconstructed with FS.

Before NMSC removal of the face, informed consent was obtained. Demographic data and surgical details were recorded for all participants. Data on postoperative complications occurring within 30 days were extracted from the medical records, either as patient-reported outcomes or as findings documented during ambulatory follow-up—whether as part of routine postoperative care or upon patient request for additional clinical evaluation. At one-year follow-up, all patients were contacted by phone to evaluate long-term outcomes through the FACE-Q Skin Cancer module assessing patient-reported satisfaction and quality of life.

Patient data, including demographics, surgical details, and complications, were recorded in Sundhedsplatformen (Epic) and subsequently transferred to a prefabricated REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database. Standardized definitions and measurement parameters were used to ensure data consistency. Data from the FACE-Q questionnaire was entered into REDCap completing data collection for analysis in one database. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to patient privacy.

Statistical analysis was conducted using R-Studio. Logistic regression was used to evaluate associations between cat-egorical and numerical predictors with categorical outcomes. Chi-square tests were applied to analyze categorical variables. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Patient Demographics

This prospective study evaluated 225 Danish patients, who were categorized according to surgical treatment: DS, n = 141 and FS, n = 40 and other, n=44. The 181 patients that underwent DS and FS were included in the study. At one year follow-up 38 patients from the DS group and 14 from the FS group completed the FACE-Q questionnaire and were included in the final study population, reasons for non-participation at follow-up were documented (Appendix 1).

Patient age was 72.72 [IQR: 67.2-79.1] for DS and 73.17 [IQR: 64.7-80.7] for FS. A table of patient demographics are shown in table 1a. Patient comorbidities are shown in table 1b.

Table 1.

a: Patient demographics.

Table 1.

a: Patient demographics.

| Group |

Mean Age, years (SD), [IQR] |

Mean BMI |

Sex, male |

Sex, female |

| Flap Surgery |

73.17 (SD=8.89) [67.2-79.1] |

25.98 (SD=4.02) |

50.0% |

50.0% |

| Simple Excision |

72.72 (SD=11.89) [64.7-80.7] |

29.61 (SD=5.34) |

46.8% |

53.2% |

Table 1.

b: Patient comorbidities.

Table 1.

b: Patient comorbidities.

| Group |

Flap Surgery |

Direct suture |

P-value |

| Medical conditions1 |

10 (71.4%) |

25 (65.8%) |

0.707 |

| Smoking Status |

|

|

0.474 |

| Never smoked |

4 (28.6%) |

13 (34.2%) |

|

| Former smoker |

2 (14.3%) |

8 (21.1%) |

|

| Current smoker |

1 (7.1%) |

2 (5.3%) |

|

| Unknown |

7 (50.0%) |

14 (36.8%) |

|

| Comorbidities |

|

|

|

| Hypertension |

7 (50.0%) |

17 (44.7%) |

0.477 |

| Heart Disease |

4 (28.6%) |

5 (13.2%) |

0.241 |

| Diabetes |

1 (7.1%) |

5 (13.2%) |

0.576 |

| Melanoma |

3 (21.4%) |

7 (18.4%) |

1.000 |

| Other Cancers |

4 (28.6%) |

7 (18.4%) |

0.506 |

| NMSC Type |

|

|

0.051 |

| BCC |

14 (100%) |

34 (89.5%) |

|

| SCC |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (10.5%) |

|

| Both BCC and SCC |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

Medical conditions contain those requiring the use of blood thinners, glucocorticoids, NSAIDs, and/or antihypertensives.

Tumor Size

Tumor sizes were a median of 9.5 mm [IQR:5.00-12.00] in the DS group and a median of 9.0 mm [IQR:5.00-12.00] in the FS group (p = 0.945).

Complications

Postoperative complications were more frequently observed among patients treated with flap surgery compared to those treated with direct suture, although none of the differences reached statistical significance. Postoperative complications are shown in

Table 2 below.

Facial Distribution of Surgery

Flap surgeries were primarily performed on the nose, accounting for most FS cases; n=11 (78.6%), whereas DS procedures were more evenly distributed across facial regions; n=14(36.8%) in the cheek region; n=6 (15.8%) in the forehead and perioral area and n=7 (18.4%) in the temporal region.

The distribution of surgical sites by procedure type are presented in

Table 3.

Table 4.

FACE-Q scores.

| FACE-Q aspect |

FS raw score |

FS conversion |

DS raw score |

DS conversion |

P-value |

| SATISFACTION WITH FACIAL APPEARANCE |

30.14 |

71 |

32.13 |

78 |

0.358 |

| APPRAISAL OF SCARS |

27.86 |

71 |

30.68 |

91 |

0.011* |

APPEARANCE-RELATED

DISTRESS |

12.14 |

23 |

10.18 |

14 |

0.058 |

| CANCER WORRY |

21.14 |

42 |

15.68 |

25 |

0.005** |

| SUN PROTECTION BEHAVIOR |

15.79 |

x |

13.37 |

x |

0.069 |

Association Between Cancer Worry and Scar Satisfaction

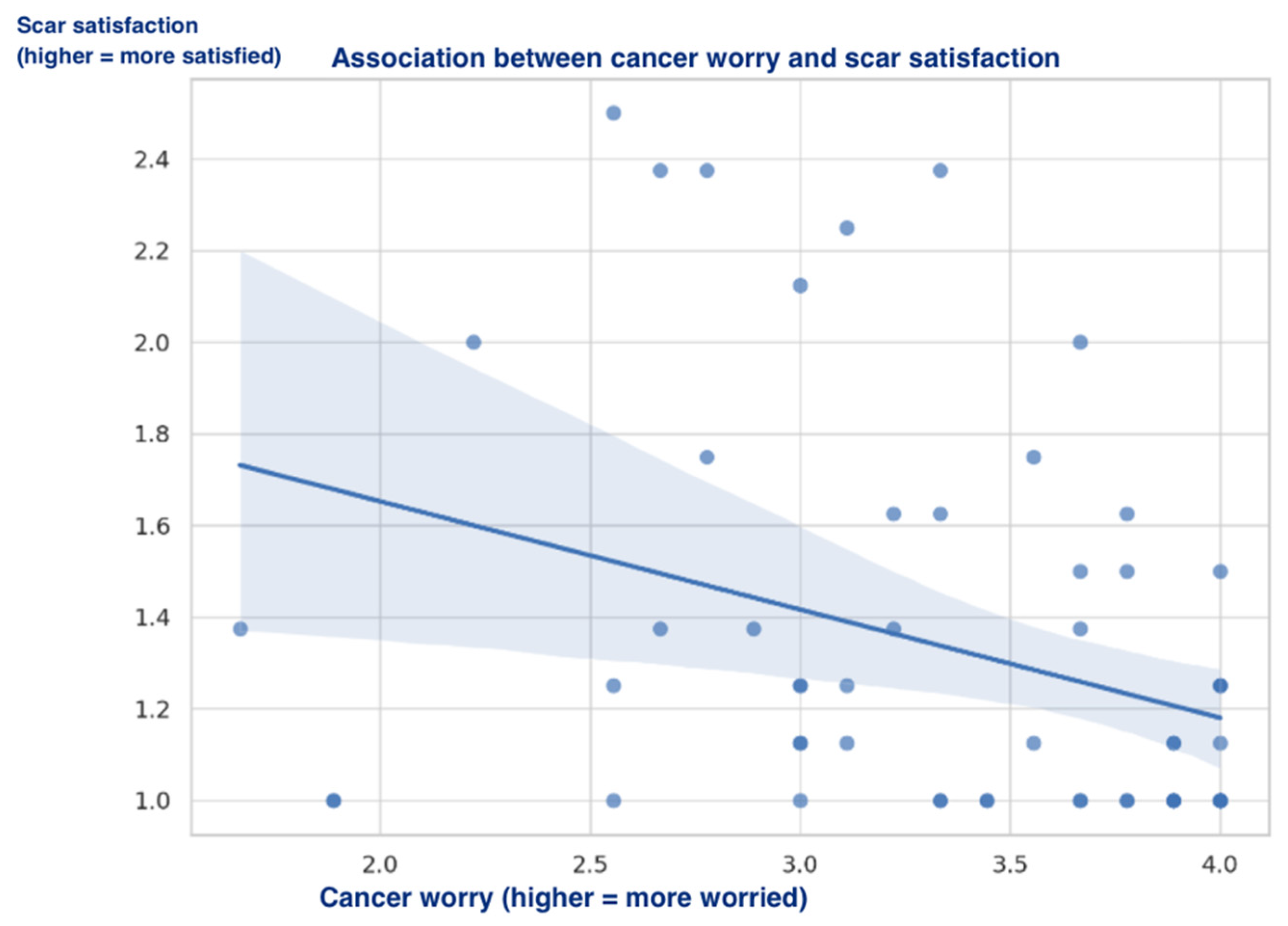

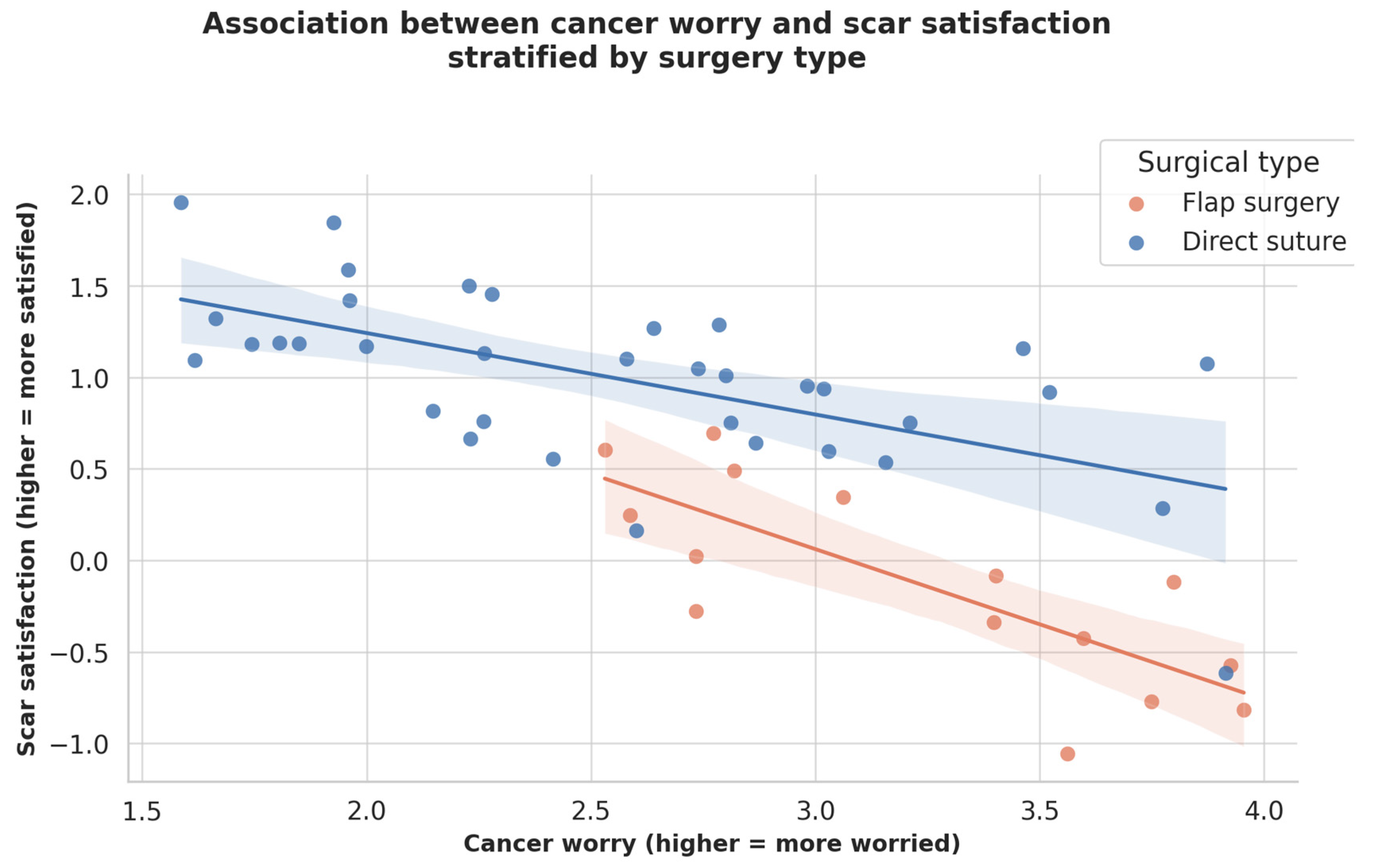

Using FACE-Q Skin Cancer modules, the study investigates the relationship between cancer-related worry and scar satisfaction among patients surgically treated for NMSC. A subtle negative correlation was found (Pearson’s r = –0.34, p < 0.01), indicating that lower cancer worry was associated with higher satisfaction with the surgical scar, the regression are plotted in figure 1. Cancer worry explained approximately 11.2% of the variance in scar satisfaction (R² = 0.112). When stratified by surgical technique, the correlation was stronger among patients treated with flap reconstruction (r = –0.56, R² = 0.517, p = 0.107) than those treated with direct closure (r = –0.35, R² = 0.085, p = 0.038).

Figure 1.

Association between cancer worry and scar satisfaction.

Figure 1.

Association between cancer worry and scar satisfaction.

Figure 2.

Association between cancer worry and scar satisfaction stratified by surgery type.

Figure 2.

Association between cancer worry and scar satisfaction stratified by surgery type.

Stratified Patient Satisfaction by Anatomical Location and Treatment Type

Scar satisfaction was assessed using the FACE-Q across different facial regions and surgical techniques.

Flap surgeries were primarily performed on the nose (n =11), while direct suture (DS) was most commonly used on the cheeks (n = 14), forehead (n = 6), and temporal region (n = 7).

In the nasal region, the median scar satisfaction scores were 8.5 (IQR: 8.0–9.0) for flap surgery (FS) and 8.5 (IQR: 8.0–8.5) for DS (based on three patients in the DS group).

For the cheek region, the DS group reported a median of 10.0 (IQR: 9.0–10.0), and the single FS case reported a score of 9.0 (IQR: 9.0–9.0).

In the forehead region, FS (n = 2) reported a satisfaction score of 10.0 (IQR: 10.0–10.0), while DS showed a median of 9.0 (IQR: 8.5–9.5).

No subgroup statistical analyses were performed due to limited sample sizes.

Detailed localizations are presented in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

This study highlights scar perception, psychological well-being, and cancer-related anxiety in patient-reported outcomes following NMSC removal of the face and defect closure using DS or reconstruction utilizing FS. These findings underscore how different surgical treatments impact patients' subjective experiences.

Scar Perception and Satisfaction

One of the statistically significant findings were that patients who underwent DS were significantly more satisfied with their scars compared to those who had FS despite no statistically significant tumor size difference between the two groups. This suggests that the additional scars needed for FS, in cases where DS are not a viable surgical option, leaves the patients with lower scar satisfaction.

The study was unable to stratify satisfaction across all anatomical regions, as some locations were treated with only one surgical method. DS was the only procedure performed in following locations: perioral, periorbital, temporal and chin.

Although flap surgery is often required for nasal reconstruction due to anatomical complexity, the slightly lower satisfaction scores in this region suggest that anatomical location itself may have a stronger influence on patient-perceived outcomes than the technique applied. Satisfaction across the cheek region and forehead remained high regardless of method, though the small number of FS cases in these regions limits the generalizability of the findings.

Another aspect of scar perception involves preoperative expectations and psychological adaptation. For instance, studies in other reconstructive settings—such as breast flap reconstruction—have shown that patients who expected a more complex surgical process tended to report greater acceptance of visible scarring afterward [

11]. Conversely, DS patients may have had lower aesthetic ex-pectations, yet still reported better scar outcomes, likely due to less invasive procedures and shorter healing times. Prior research suggests that age-related differences in body image perception could also contribute to this, as older patients tend to exhibit greater psychological resilience and lower aesthetic dissatisfaction [

12].

Clinical Implications

FS patients may benefit from additional counseling and expectation management to mitigate distress related to appearance changes and cancer-related anxiety. However, it should be acknowledged that extensive preoperative information may in some cases increase worry, as patients may focus more on potential risks and complications. Balancing adequate information with reassurance are therefore essential, and future studies should explore how communication strategies influence psychological outcomes in this patient group.

Psychosocial interventions, including preoperative discussions on expected outcomes and psychological follow-ups, may be valuable in reducing cancer worry and improving overall postoperative well-being.

By recognizing that surgical success are not solely defined by clinical outcomes but also by psychological and social well-being, healthcare providers can develop more comprehensive, patient-centered strategies that improve long-term quality of life.

Limitations and Future Directions

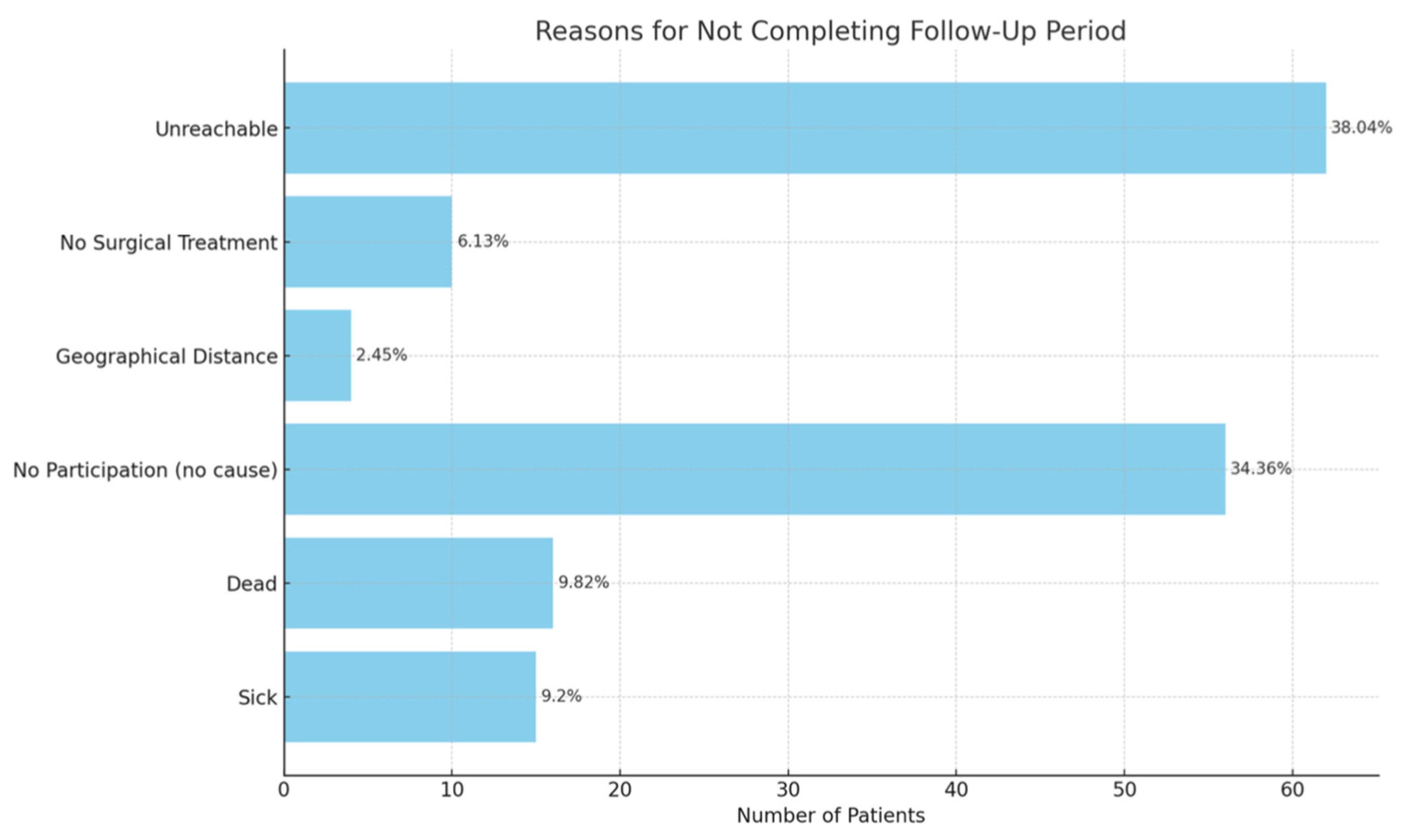

A major limitation of this study is the high attrition rate: only 52 out of 181 enrolled patients completed the FACE-Q questionnaire at the one-year follow-up. This substantial loss to follow-up reduces statistical power and may introduce response bias, as responders may not fully represent the overall study population—for example, individuals with higher resources or greater satisfaction with their surgical outcome may be more likely to complete follow-up []. Patients who did not respond may differ systematically from those who did, potentially skewing the results toward those with more positive or more negative experiences. The reasons for non-participation were heterogeneous (see Appendix 1), but the overall dropout rate limits the generalizability and robustness of the findings. Future studies should prioritize strategies to enhance follow-up compliance, including reminder systems or integration with routine outpatient visits.

Although this study provides valuable insights into patient-reported outcomes following facial skin cancer reconstruction, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size of FS patients may limit the generalizability of findings, and future research with larger, multi-center cohorts are warranted. Additionally, while FACE-Q provides a comprehensive assessment of patient satisfaction, a longer follow-up period could better capture long-term psychological adaptation and aesthetic perception changes.

Future studies should also explore the role of demographic factors, including sex, age, and baseline psychological status, in shaping patient perceptions of surgical outcomes. Furthermore, objective clinical evaluations of scar healing could complement pa-tient-reported measures to provide a more holistic understanding of surgical success.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated patient reported outcomes after NMSC removal of the face and DS or reconstruction with FS. Flap surgery following NMSC excision are associated with lower patient-reported satisfaction compared to DS. Our findings indicate that the need to go up the reconstructive ladder does influence patient-reported outcomes: FS was associated with significantly lower scar satisfaction and higher levels of cancer-related worry. However, when stratified by anatomical location, satisfaction appeared more closely linked to the surgical site—particularly the nasal re-gion—than to the reconstructive method itself.

Furthermore, a moderate negative correlation between scar satisfaction and cancer worry suggests that aesthetic outcomes are not merely cosmetic concerns, but closely intertwined with patients’ psychological well-being and quality of life. These results underline the importance of adopting a holistic, patient-centered approach—one that integrates technical outcomes with emotional recovery, expectation management, and long-term psychosocial support..

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.T.P., F.P.W.M. and C.H.K.; Methodology, H.T.P., C.H.K., N.M.B. and C.L.R.; Validation, C.H.K. and F.P.W.M.; Formal analysis, N.M.B. and C.L.R.; Investigation, C.L.R. and N.M.B.; Data curation, N.M.B., C.H.K. and C.L.R.; Visualization, N.M.B. and C.L.R.; Writing—original draft, C.L.R.; Writing—review & editing, F.P.W.M., H.T.P. and C.L.R.; Supervision, H.T.P. and F.P.W.M.; Project administration, C.L.R.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Region Zealand Research Registry, Denmark (protocol code 098-2020; approval date 22 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication was obtained where applicable (e.g., for identifiable images or clinical details).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to patient privacy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nursing and administrative staff at Zealand University Hospital for assistance during patient inclusion and follow-up.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AI Use Disclosure

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used large language model tools for drafting/formatting assistance. The final text was reviewed and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content.

Appendix A

Table A1.

STROBE Checklist.

Table A1.

STROBE Checklist.

| Item |

Recommendation (abridged) |

Where in manuscript |

Compliance |

| 1a |

Indicate the study design in the title or abstract |

Title/Abstract (states 'prospective cohort') |

Yes |

| 1b |

Provide an informative and balanced abstract |

Abstract |

Yes |

| 2 |

Explain scientific background and rationale |

Introduction |

Yes |

| 3 |

State specific objectives/prespecified hypotheses |

Introduction (Objectives) |

Yes |

| 4 |

Present key elements of study design early in paper |

Materials and Methods (Study design) |

Yes |

| 5 |

Describe setting, locations, and relevant dates |

Materials and Methods (Setting, dates) |

Yes |

| 6a |

Give eligibility criteria and methods of follow-up |

Materials and Methods (Participants) |

Yes |

| 6b |

For matched studies, give matching criteria |

Not applicable (unmatched cohort) |

N/A |

| 7 |

Clearly define outcomes, exposures, predictors, confounders |

Materials and Methods (Variables) |

Yes |

| 8 |

Data sources/measurement for each variable and comparability |

Materials and Methods (Data sources/measurement) |

Yes |

| 9 |

Describe efforts to address potential sources of bias |

Materials and Methods (Bias) |

Yes |

| 10 |

Explain how the study size was arrived at |

Materials and Methods (Study size) |

Yes |

| 11 |

Explain handling of quantitative variables |

Materials and Methods (Quantitative variables) |

Yes |

| 12a |

Describe all statistical methods incl. confounding control |

Materials and Methods (Statistical methods) |

Yes |

| 12b |

Methods for subgroup/interaction analyses |

Materials and Methods (Statistical methods: subgroup/interaction) |

Yes |

| 12c |

How missing data were addressed |

Materials and Methods (Statistical methods: missing data) |

Yes |

| 12d |

How loss to follow-up was addressed |

Materials and Methods (Follow-up/attrition) |

Yes |

| 12e |

Sensitivity analyses |

Materials and Methods (Sensitivity analyses) |

Yes |

| 13a |

Report numbers at each stage (eligible, included, follow-up, analysed) |

Results (Participants) |

Yes |

| 13b |

Give reasons for non-participation |

Results (Participants); Table A1 (Reasons for non-participation) |

Yes |

| 13c |

Consider a flow diagram |

Results (Participant flow); Flow diagram (Figure A1, if provided) |

Yes |

| 14a |

Give characteristics of study participants |

Results (Descriptive data); Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5

|

Yes |

| 14b |

Indicate number with missing data for each variable |

Results (Descriptive data); Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5

|

Yes |

| 14c |

Summarise follow-up time |

Results (Participants/Follow-up) |

Yes |

| 15 |

Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time |

Results (Outcome data); Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 Figure 1, Figure 2, figure 1 |

Yes |

| 16a |

Give unadjusted and adjusted estimates with precision; specify confounders |

Results (Main results); Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5

|

Yes |

| 16b |

Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized |

Materials and Methods/Results (Variables & Main results) |

Yes |

| 16c |

Translate estimates of relative risk into absolute risk if relevant |

Results/Discussion (Interpretation of absolute effects) |

Yes |

| 17 |

Report other analyses done (subgroups, interactions, sensitivity) |

Results (Other analyses) |

Yes |

| 18 |

Summarise key results with reference to objectives |

Discussion (Key results) |

Yes |

| 19 |

Discuss limitations and potential bias/imprecision |

Discussion (Limitations) |

Yes |

| 20 |

Provide a cautious overall interpretation of results |

Discussion (Interpretation) |

Yes |

| 21 |

Discuss generalisability (external validity) of results |

Discussion (Generalisability) |

Yes |

| 22 |

Give the source of funding and the role of the funders |

Back matter (Funding) |

Yes |

References

- Lomas, A., Leonardi-Bee, J., & Bath-Hextall, F. (2012). A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. British Journal of Dermatology, 166(5), 1069-1080. [CrossRef]

- Badash, I., Shauly, O., Lui, C.G., Gould, D.J., & Patel, K.M. (2019). Nonmelanoma Facial Skin Cancer: A Review of Diagnostic Strategies, Surgical Treatment, and Reconstructive Techniques. Clinical Medicine Insights: Ear, Nose & Throat, 12, 117955061986527. [CrossRef]

- Ciuciulete, A.R., Stepan, A.E., Andreiana, B.C., & Simionescu, C.E. (2022). Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: Statistical Associations between Clinical Parameters. Current Health Sciences Journal, 48(1), 110-115. [CrossRef]

- Wu L, Tang S, Jiang J, Li K. Construction of a predictive model for the effectiveness of plastic surgery and repair in patients with facial basal cell carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2024 Dec 15;14(12):5798-5811. PMID: 39803642; PMCID: PMC11711530. [CrossRef]

- Helmy, Y., Taha, A.M., Khallaf, A.E., & Al-Sheikh, A. (2017). Survival and aesthetic outcome of local flaps used for reconstruction of face defects after excision of skin malignancies: Multi-institutional experience of 175 cases. [CrossRef]

- Cordova LZ, Hunter-Smith DJ, Rozen WM. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) following mastectomy with breast reconstruction or without reconstruction: a systematic review. Gland Surg. 2019 Aug;8(4):441-451. PMID: 31538070; PMCID: PMC6723012. [CrossRef]

- van der Wal MB, Tuinebreijer WE, Bloemen MC, Verhaegen PD, Middelkoop E, van Zuijlen PP. Rasch analysis of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) in burn scars. Qual Life Res. 2012 Feb;21(1):13-23. Epub 2011 May 20. PMID: 21598065; PMCID: PMC3254877. [CrossRef]

- Lee EH, Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Nehal KS, Pusic AL. FACE-Q Skin Cancer Module for measuring patient-reported outcomes following facial skin cancer surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Jul;179(1):88-94. Epub 2018 May 23. PMID: 29654700; PMCID: PMC6115303. [CrossRef]

- Ottenhof, M.J., Dobbs, T.D., Veldhuizen, I., Harrison, C.J., Marges, M., Lee, E.H., Hoogbergen, M.M., van der Hulst, R.R.W.J., Pusic, A.L., & Sidey-Gibbons, C.J. (2024). FACE-Q for Measuring Patient-reported Outcomes after Facial Skin Cancer Surgery: Cross-cultural Validation. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery - Global Open, 12(4), e5771. [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A.F., Cano, S.J., Schwitzer, J.A., Scott, A.M., & Pusic, A.L. (2015). FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: development and validation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 135(2), 375-386. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Nab Z, Grunfeld EA. Satisfaction with outcome and attitudes towards scarring among women undergoing breast reconstructive surgery. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 May;66(2):243-9. Epub 2007 Mar 6. PMID: 17337153. [CrossRef]

- Milton A, Hambleton A, Roberts A, Davenport T, Flego A, Burns J, Hickie I: Body Image Distress and Its Associations From an International Sample of Men and Women Across the Adult Life Span: Web-Based Survey Study, JMIR Form Res 2021;5(11):e25329. [CrossRef]

- Kouwenberg, C. (2021). Psychological Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Breast Cancer Surgery. [Doctoral Thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam]. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam (EUR).

- Hammermüller, C., Hinz, A., Dietz, A. et al. Depression, anxiety, fatigue, and quality of life in a large sample of patients suffering from head and neck cancer in comparison with the general population. BMC Cancer 21, 94 (2021).

- Zebolsky AL, Patel N, Heaton CM, Park AM, Seth R, Knott PD. Patient-Reported Aesthetic and Psychosocial Outcomes After Microvascular Reconstruction for Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021 Dec 1;147(12):1035-1044. PMID: 34292310; PMCID: PMC8299365. [CrossRef]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Sep;17(9):643-53. Epub 2007 Jun 6. PMID: 17553702. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

| Complication |

Flap Surgery |

Direct Suture |

P-value |

| Infection |

1 (7.1%) |

1 (2.6%) |

0.470 |

| Cellulitis |

1 (7.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0.269 |

| Minor hematoma |

2 (14.3%) |

1 (2.6%) |

0.173 |

| Necrosis |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1.000 |

| Wound dehiscence |

1 (7.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0.269 |

| Major complications |

3 (21.4%) |

1 (2.6%) |

0.055 |

Table 3.

| Anatomical_location |

Direct Suturing |

Flap Surgery |

| Cheeks |

14 (36.8%) |

1 (7.1%) |

| Chin |

1 (2.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Forehead |

6 (15.8%) |

2 (14.3%) |

| Lips/Perioral Area |

6 (15.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Nose |

3 (7.9%) |

11 (78.6%) |

| Periorbital Area |

1 (2.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

| Temple |

7 (18.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

Table 5.

| Anatomical Location |

n (FS) |

Median (IQR) Satisfaction (FS) |

n (DS) |

Median (IQR) Satisfaction (DS) |

| Cheek |

1 |

9.0 (9.0–9.0) |

14 |

10.0 (9.0–10.0) |

| Forehead |

2 |

10.0 (10.0–10.0) |

6 |

9.0 (8.5–9.5) |

| Nose |

11 |

8.5 (8.0–9.0) |

3 |

8.5 (8.0–8.5) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).