Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can be a debilitating condition, affects millions worldwide and remains notoriously difficult to manage. Despite decades of research, treatment options largely focus on symptom suppression rather than addressing root causes — and for many patients, long-term relief remains elusive. In recent years, different fasting regimes have emerged as biologically plausible, low-cost interventions with the potential to influence multiple mechanisms implicated in IBS. This paper explores the hypothesis that structured intermittent fasting could improve intestinal homeostasis and reduce symptom burden in IBS.

The Condition, Its Prevalence and Its Comorbidities

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain and changes in stool form and frequency (diarrhea, constipation, or both), as defined by the Rome IV criteria [

1], in the absence of detectable pathology on standard medical testing [

2]. Reliable biomarkers for IBS are lacking [

3]. The global prevalence of IBS is estimated at 9.2%, though this varies widely between countries—even when standardized diagnostic criteria and methods are applied [

4]. Prevalence is consistently higher among women than men [

4].

In addition to gastrointestinal symptoms, IBS is frequently accompanied by comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and sleep disturbances [

5]. It is often unclear whether IBS leads to these conditions or arises as a consequence of them. However, in the case of mood disorders, some evidence suggests that gastrointestinal symptoms may precede psychological symptoms [

6]. Both the GI symptoms and comorbidities contribute to significantly reduced quality of life [

7], and patients have reported a willingness to sacrifice years of life expectancy for effective relief [

8]. The disorder also imposes a substantial economic burden, both through direct healthcare costs and through indirect costs such as reduced work productivity and disability benefits [

8].

Because there is currently no known cure for IBS, treatment strategies typically focus on symptom relief through medications, dietary interventions, or supplements. However, these approaches do not address the underlying pathophysiology and may fail to produce long-term improvement [

6]. Surveys indicate that many IBS patients experience unmet needs and are dissatisfied with the care they receive from the healthcare system [

7,

9]. Given the significant burden IBS places on both individuals and society, there is a clear need to expand the therapeutic toolbox available to patients and clinicians to improve outcomes and reduce long-term costs.

The Multifaceted Pathophysiology of IBS

The pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) remains incompletely understood, but current evidence points to a complex interplay between the gut and the central nervous system. Disruptions in the gut–brain axis contribute to key features of the disorder, including altered gastrointestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and changes in central pain processing [

10].

In a comprehensive review published in The Lancet, Holtmann et al. summarize the diverse pathological features associated with IBS, emphasizing its heterogeneous and multifactorial nature [

6]. Their analysis highlights that, compared with healthy individuals, IBS patients exhibit a range of inflammation-related abnormalities, such as gut microbiota dysbiosis, low-grade mucosal inflammation, increased intestinal permeability, and both local (gut-specific) and systemic (humoral) immune activation. These findings challenge the traditional notion of IBS as a functional disorder rooted solely in gut–brain axis dysregulation and support its reclassification as a disorder with measurable biological alterations [

6].

The Role of Diet in IBS

Although food reactions are not included in the most common diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a majority of patients report that meals exacerbate their symptoms [

11]. In recent years, the role of diet has gained increasing attention both in research and in clinical management of IBS [

12]. However, identifying true individual dietary triggers remains challenging, and many patients continue to experience symptoms despite significant dietary modifications [

13].

Several studies have shown that IBS patients often report intolerances to specific foods, food groups, or food components [

11,

14]. Yet, when these self-reported intolerances are tested under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions, only a small proportion can be reliably reproduced [

15]. This discrepancy may be due to the dose-dependent or delayed nature of food-related symptoms, making it difficult to pinpoint true dietary triggers. As a result, patients may unnecessarily eliminate benign foods - in the worst case a risk factor for disordered eating behavior such as avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder [

16] - while continuing to consume unrecognized triggers.

Despite the well-known limitations of self-reported dietary intake in observational studies, robust evidence exists from controlled human trials for specific dietary triggers of IBS symptoms. For example, fermentable carbohydrates such as fructose and sorbitol [

17], as well as lactulose—a synthetic carbohydrate used medically [

18]—have been shown to reliably provoke gastrointestinal symptoms in individuals with IBS under controlled conditions. In another intervention study, bran intake was associated with symptom worsening in the majority of IBS participants, though a minority reported relief [

19].

While most treatment strategies target the colon, evidence suggests that the small intestine may also play a role. Using confocal laser endomicroscopy, immediate structural and functional changes—along with infiltration of inflammatory cells—have been observed in the duodenal tissue of IBS patients after exposure to common dietary components such as cow’s milk, wheat, yeast, and soy [

20,

21]. These findings highlight the importance of considering small intestinal responses when evaluating dietary influences in IBS.

Limitations to Dietary Symptom Management

Elimination diets, such as the low FODMAP diet or very low-carbohydrate diets, have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating IBS symptoms [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Notably, the recent CARIBS trial showed that dietary interventions resulted in greater symptom improvement than pharmacological treatment [

26]. However, these dietary approaches are highly restrictive, often leading to a limited variety of food options and requiring substantial patient involvement. They may also pose social and practical challenges, making long-term adherence difficult. While adherence can be significantly improved through the support of a dietitian [

27], such professional guidance is not always available or systematically offered to patients within clinical care pathways [

28].

In addition, dietary recommendations for IBS management may conflict with general dietary guidelines, which can create confusion for patients attempting to self-manage their symptoms. For example, many of the fermentable carbohydrates associated with IBS symptoms are also classified as dietary fibers—non-digestible carbohydrates that are typically fermented by the gut microbiota. While a high intake of fiber is widely promoted as beneficial for intestinal health [

29], this general advice may be counterproductive for IBS patients in the absence of individualized dietary guidance.

The temporal relationship between dietary triggers and IBS pathology remains unclear and adds to the complexity of understanding the condition. A central question is whether dietary factors contribute to the development of IBS pathology, thereby leading to symptoms, or whether an underlying IBS pathology increases sensitivity to dietary triggers: the “chicken or egg” dilemma.

Coffee consumption serves as a useful example of this uncertainty. While it is frequently self-reported as a symptom trigger among IBS patients [

12] and has been linked to symptom recurrence upon reintroduction following exclusion [

30], its causal role remains unresolved. To date, no RCT has specifically examined the effect of coffee consumption on IBS symptoms. Only one prospective study has investigated the association, finding that coffee intake was associated with a reduced risk of developing IBS [31). In contrast, cross-sectional studies have yielded inconsistent results, reporting both increased and decreased odds of IBS symptoms associated with coffee consumption [

31].

The Role of the Microbiome in IBS

There is increasing recognition that disturbances in the intestinal microbiome may be both a contributor to and consequence of intestinal inflammation in IBS. While advances in sequencing technologies have generated vast amounts of microbiome data from IBS patients, no universally accepted microbial signature has been identified that can reliably distinguish IBS patients from healthy individuals or serve as a diagnostic biomarker [

32].

Nonetheless, comparative studies have identified recurring microbial features in IBS. These include an increased abundance of Firmicutes, a higher Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio [

32], and elevated levels of Proteobacteria, including potentially pathogenic strains such as Escherichia coli and methanogens [

33]. Conversely, IBS patients often show a reduction in beneficial microbes, particularly Bifidobacterium species and butyrate-producing bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which are crucial for maintaining gut barrier integrity and modulating inflammation [

32,

33,

34].

Machine learning approaches have shown promise in identifying microbial signatures associated with IBS symptom severity, successfully distinguishing patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, as well as differentiating IBS from IBD [

34,

35]. However, inconsistencies between studies, interindividual variability, and differences across IBS subtypes have hindered the development of a unified microbial profile, challenging the notion of a taxonomically defined IBS-related dysbiosis.

The complexity of diet - microbiome - host interactions is still being unraveled, and current understanding remains incomplete. Most microbiome studies rely on fecal sampling, which primarily reflects the microbial composition of the distal colon. While informative, these samples may not accurately capture structural and functional alterations in the small intestine or upper gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, much of the existing research focuses on bacterial taxa, often overlooking the roles of the mycobiome, phageome, and the broader interplay between microbial kingdoms in shaping gut function.

This limited understanding has implications for treatment development. Research into alternative therapies, such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), has yielded mixed results: while some clinical trials report symptom improvement, others have found no consistent benefit, and the long-term efficacy of FMT in IBS remains uncertain [

36]. These findings underscore the need for a more comprehensive ecological perspective that includes host factors and microbial functionality, not just composition, in efforts to restore gut homeostasis.

In a recent paradigm-shifting paper, Lee et al. [

37] argue for moving beyond compositional analysis toward an ecological framework that conceptualizes the gut as a homeostatic ecosystem. Under normal conditions, the host maintains hypoxic environments in the colon that favor obligate anaerobic fermenters. However, disruptions caused by inflammation, antibiotics, or dietary insults can increase luminal oxygen, allowing facultative anaerobes - often associated with disease - to dominate. According to this model, observed shifts in microbial composition may be symptoms of a disrupted environment, rather than the primary cause of dysbiosis. This reframing invites a broader therapeutic perspective: rather than targeting specific microbes, interventions might aim to restore ecological balance and host-microbial homeostasis, offering novel avenues for managing IBS.

This shift in thinking can be exemplified by the intestinal barrier - including the mucus barrier - which serves as the first line of defense by shielding the epithelium from pathogens, mechanical stress, and dietary antigens [

38]. Disruption of the mucus barrier has been implicated in a range of gastrointestinal disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and metabolic conditions [

39]. For example, mice deficient in MUC2 - the primary colonic mucin - exhibit a thinner, more penetrable mucus layer that allows commensal microbes to approach the epithelial surface. These mice are highly vulnerable to intestinal infections, develop spontaneous colitis even in the absence of pathogens, and show increased risk of tumor formation driven by low-grade inflammation and epithelial proliferation [

39]. Dietary factors can significantly influence mucus barrier function, as demonstrated in preclinical studies. Maltodextrin, a processed polysaccharide, has been shown to disrupt gut microbial balance, promote adherence of pathobionts, degrade mucins, and increase intestinal permeability [

40]. Similarly, carboxymethylcellulose, a synthetic emulsifier widely used in processed foods, has been found to deplete commensal bacteria within the mucus layer, thin the mucus barrier, increase inflammatory responses, and promote microbial encroachment in animal models [

41]. Emerging evidence also highlights the importance of the mucus barrier in preventing food allergies and sensitivities [

39]. Hence, seeking to avoid dietary factors that have the potential to compromise host-microbial homeostasis via the mucus lining, could be more useful than dietary interventions seeking to reduce symptoms that occur as a result.

Can Insights from IBD Be Helpful for Understanding IBS?

It has been proposed that IBS may represent a subclinical or low-grade form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), due to considerable overlap in underlying mechanisms [

42]. Supporting this, many patients with IBD experience IBS-like symptoms during remission, suggesting a continuum in symptom expression between the two conditions [

43]. Moreover, both IBS and IBD patients display mucosal biofilms and disruptions in bile acid metabolism to a far greater extent than healthy controls [

44].

Dysbiosis is another hallmark shared between IBS and IBD. Both conditions are associated with reduced gut microbial diversity, loss of beneficial bacterial species (such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bifidobacterium spp.), and increased abundance of potentially pathogenic bacteria, particularly within the phylum Proteobacteria [

34,

45]. These features reflect a common inflammatory component in the microbial ecosystem of both disorders.

Evidence from nutritional interventions also points to shared responses. For instance, FODMAP restriction has been shown to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms in IBD patients during remission, although this symptom improvement does not correspond to changes in inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or fecal calprotectin [

22,

46]. This finding highlights a broader concern in both IBS and IBD: that symptom-targeted treatments may not adequately address underlying pathology [

6].

While no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to date have examined the effects of very low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets on IBD symptoms or disease activity, case reports suggest that ketogenic diets - particularly those based on animal-source foods - may improve outcomes in select patients, potentially by eliminating common dietary triggers [

47]. In animal models of colitis induced with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), ketogenic diets have shown mixed results, further emphasizing the need for human studies [

48,

49].

A variety of dietary strategies have been proposed to alleviate both symptoms and inflammation in IBD [

50]. Among these, intermittent fasting regimens stand out due to their universal accessibility, low cost, and minimal need for clinical supervision. Given the inflammatory features observed in IBS and its pathophysiological similarities with IBD, it is worth exploring whether dietary strategies that reduce inflammation in IBD could also be beneficial for IBS patients.

The Therapeutic Potential of Fasting

Over the past two decades, the body of literature on periodic fasting strategies has grown rapidly. However, this field continues to face challenges due to the lack of standardized protocols and consistent terminology. To address this issue, we adopt the definitions proposed in a recent expert consensus publication on fasting terminology, which aims to guide future research and clinical application [

51].

|

Fasting: any voluntary abstinence from some or all foods or foods and beverages. |

Intermittent fasting (IF): repetitive fasting periods lasting up to 48 hours each,

includes time restricted eating. |

Time restricted eating (TRE): as a dietary regimen with a fasting window of at least

14 h per day in humans, and no limit on energy intake during eating hours. |

|

Fasting mimicking diet: any diet specifically composed to induce the metabolic effects of fasting while allowing for a potentially higher caloric intake, including solid foods. |

Interventions involving various forms of fasting have demonstrated broad health benefits across conditions with distinct etiologies. In humans, fasting has been shown to improve markers of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and systemic inflammation, and has led to meaningful improvements in obesity, hypertension, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis - conditions in which inflammation is part of the clinical picture [

52,

53]. Despite these findings, fasting remains largely unexplored in the context of IBS. To date, we have identified only one study in which a 10-day fasting intervention led to improvements in multiple IBS symptoms compared to a control group [

54]. However, this protocol involved total starvation under medical supervision, limiting its practicality as a self-managed therapeutic strategy for clinicians and patients.

Surprisingly, no published studies have evaluated whether more accessible, structured IF regimens might benefit individuals with IBS. Given the growing evidence of shared inflammatory and microbial features between IBS and IBD discussed previously in this paper, findings from fasting studies in IBD populations may hold relevance for IBS management.

Although research on fasting in IBD remains limited, early results are encouraging. Fasting-mimicking diets have been associated with reduced inflammation and symptom improvement in both human patients and animal models of IBD [

55]. For instance, in a case study involving a female patient with ulcerative colitis, eight weeks of TRE led to a significant reduction in inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and calprotectin [

56]. Additionally, several ongoing or recently completed clinical trials are actively investigating the therapeutic potential of fasting regimens in IBD patients [

57,

58,

59], underscoring increasing scientific interest in this approach.

Based on current evidence and shared disease mechanisms, we hypothesize that increasing time spent in a fasting state could alleviate IBS symptoms by targeting underlying inflammatory and microbial dysregulation. While clinical trials on PF in IBS are still lacking, mechanistic studies suggest that fasting can attenuate gut inflammation - supporting the rationale for exploring structured fasting as a feasible, low-cost, and accessible adjunctive therapy for IBS.Hence, seeking to avoid dietary factors that have the potential to compromise host-microbial homeostasis via the mucus lining, could be more useful than dietary interventions seeking to reduce symptoms that occur as a result.

Underappreciated Need for Renewal in IBS?

The fact that meals induce damage to the epithelium has generally received little attention in IBS management. The intestinal tract is exposed to constant mechanical, chemical, and microbial challenges, necessitating rapid and continuous epithelial renewal, occurring approximately every 3–5 days in the small intestine [

60] and every 5–7 days in the colon [

61]. In both the small intestine and colon stem cells located at the base of the crypts divide to produce transient cells which proliferate, differentiate, and migrate along defined axes. In the small intestine, differentiated cells (including absorptive enterocytes, Goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells, and Paneth cells) migrate upward along the crypt–villus axis, while in the colon—where villi are absent—they migrate toward the luminal surface. In both regions, fully matured cells are ultimately shed into the intestinal lumen via apoptosis [

60,

61]. This highly dynamic turnover is tightly regulated by both endogenous signals and exogenous stimuli from the gut microbiota. Notably, microbial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) enhance proliferation and differentiation of epithelial cells, thereby contributing to epithelial homeostasis [

60]. Thus, the integrity of the intestinal epithelium depends on the orchestrated interaction between stem cells, niche signals, and the gut microbiota.

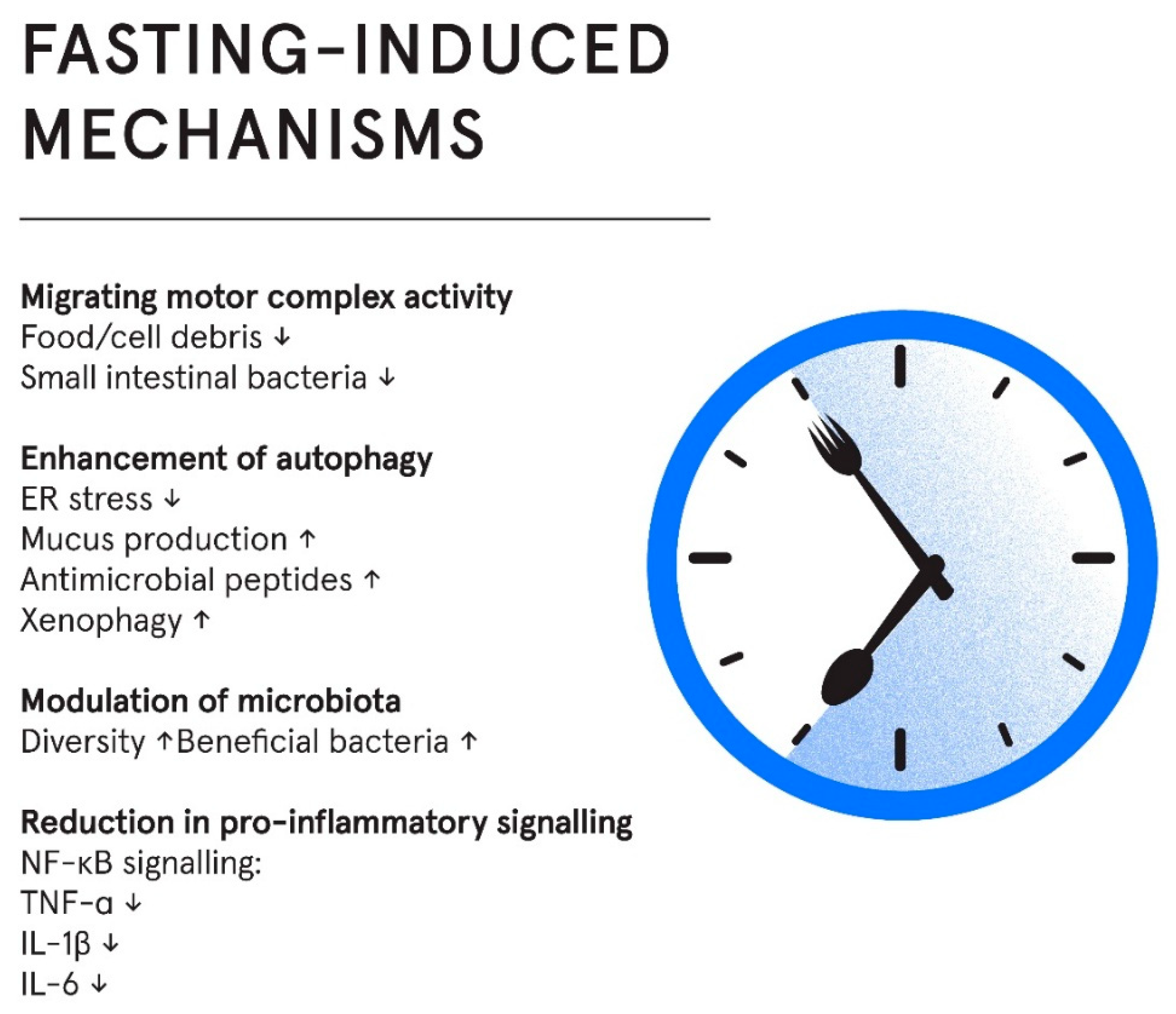

Regenerative processes induced by fasting have received little attention in the field of IBS, but research indicates that periods of fasting that allow for maintenance, repair and renewal could be a missing link in understanding disease pathology. Several mechanisms that influence the homeostatic environment of the gut may be involved, including pro-inflammatory signalling, migrating motor complex activity, modulation of gut microbiota, reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhancement of autophagy, as discussed in the following sections.

Mechanisms by Which IF May Improve Gut Homeostasis in IBS

Figure 1.

Fasting influences multiple interconnected domains, including microbiome composition, gut motility, mucosal inflammation and autophagy. These changes may support epithelial integrity and reduce symptom burden.

Figure 1.

Fasting influences multiple interconnected domains, including microbiome composition, gut motility, mucosal inflammation and autophagy. These changes may support epithelial integrity and reduce symptom burden.

Reduction in Pro-Inflammatory Signaling

Mechanistically, fasting inhibits NF-κB signaling, a central mediator of inflammation, thereby downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines [

62]. Accordingly, IF regimes have reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in both animal and human trials [

62]. However, despite an established mechanistic link between fasting and reduced inflammation, the inclusion of studies on healthy individuals in systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well as the lack of studies on IBS patients, makes results difficult to interpret in the context of IBS pathology.

Migrating Motor Complex Activity

The migrating motor complex (MMC) is a cyclical pattern of electromechanical activity that occurs in the stomach and small intestine during fasting periods [

63]. Commonly referred to as the “housekeeper” of the gut, the MMC plays a vital role in clearing residual food particles, mucus, and bacteria, thereby helping to prevent bacterial overgrowth and intestinal inflammation.

Disruptions in migrating motor complex (MMC) activity have been linked to various gastrointestinal disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Patients with IBS tend to exhibit a shorter duration of postprandial motor activity than healthy individuals, and those with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) often show shorter intervals between MMCs compared to those with constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C). Impaired MMC function is also associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) - a condition commonly seen in IBS - highlighting a broader pattern of dysregulated interdigestive motility in the disorder [

64].

These findings suggest a pattern of dysregulated interdigestive motility in IBS. However, whether the disturbances in MMC activity are a cause or consequence of IBS remains uncertain. Because the MMC is initiated during fasting and suppressed by food intake [

56], fasting protocols may improve MMC activity regulation by prolonging fasting periods, thereby supporting bacterial clearance and contributing to gut homeostasis. Although there is a biological rationale for enhancing MMC function through fasting, direct clinical evidence is warranted to evaluate its therapeutic potential in IBS.

Modulation of Gut Microbiota

Evidence from both human and animal studies indicate that long term fasting induces a state of remodeling and renewal of both the microbial ecosystem and intestinal tissues, with subsequent reduction in pro-inflammatory events and immune responses [

65]. Longer-term fasting also leads to a reduction in microbial density, and a relative increase in microbes capable of utilising host derived nutrients sources (shedded epithelial cells and mucins), such as Akkermansia muciniphila [

65]. Consequently, it has been hypothesised that fasting is a mechanism that enables the host to reset the microbial ecosystem in the gut and to regain control of the microbial activity [

65]. IF, including TRE, has been associated with changes in the gut microbiota composition, richness, and diversity. In human studies, IF has shown potential to increase microbial richness and α-diversity, although results vary between individuals and fasting regimens, results from human studies are heterogeneous and difficult to interpret [

66]. Of interest, beneficial genera such as Akkermansia and Faecalibacterium, have been reported to increase during IF [

66,

67].

Enhancement of Autophagy

Autophagy is a highly conserved, cell-intrinsic recycling mechanism essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, especially in tissues exposed to environmental stressors like the gut. In intestinal epithelial cells, autophagy plays a critical role in sustaining barrier integrity and immune balance. It is activated in response to stressors such as nutrient deprivation, infection, and organelle damage, facilitating the degradation of dysfunctional components and invasive pathogens [

68]. In the gut, autophagy safeguards epithelial function through several key mechanisms. It alleviates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and supports mucus secretion in Goblet cells, while also enabling Paneth cells to release antimicrobial peptides [

69]. These functions are essential for maintaining the mucosal barrier and preventing microbial translocation. Additionally, autophagy facilitates xenophagy - the selective clearance of invading microbes - thereby limiting inflammation and preserving gut immune tolerance.

Disruption of autophagic pathways has been linked to gut inflammatory conditions by impaired secretion, barrier dysfunction, and heightened inflammatory responses in both animal models and human patients [

69]. Importantly, fasting is one of the most potent physiological inducers of autophagy. Evidence indicates that food deprivation robustly activates autophagy in various tissues, including the gut, enhancing the cell’s ability to clear damaged components and preserve homeostasis [

68]. Current research on the relationship between autophagy and IBS is limited, however a mechanistic link between IBS pathology and impaired autophagy was recently demonstrated, as exosomes derived from IBS patients can suppress autophagy in human colon epithelial cells [

70]. Thus, therapeutic strategies aiming to restore autophagy may hold promise in improving IBS-related epithelial dysfunction.

Considerations for the Application of Intermittent Fasting Regimes in IBS Treatment

While further research is needed to fully understand the long-term effects and mechanisms of intermittent fasting in IBS, early findings suggest promising potential for this approach as a safe, accessible, and non-pharmacological strategy both to support symptom management and to address underlying pathology. As fasting regimes in this context are not meant to induce weight loss, participants should be instructed to seek nutrient-dense foods and to eat to satiety with meals in order to prevent nutritional deficiencies and to support metabolic and overall physiological function. Also, as individuals with IBS are at increased risk of disordered eating, any dietary intervention - including intermittent fasting - should be approached with caution and tailored to the patient’s psychological relationship with food. With thoughtful implementation and continued scientific inquiry, intermittent fasting could emerge as a valuable addition to the therapeutic toolkit for IBS.

Author Contributions

Marit Kolby did the research and drafted the manuscript. Asgeir Brevik, Hanna Fjeldheim Dale, Marianne Molin and Jørgen Valeur have critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Funding

This work has not been funded.

Acknowledgments

An ai-based tool was used for textual improvements of this manuscript. Specifically, ChatGPT 4.0 was used to improve structure in written English, and to rephrase selected sections for readability. The AI tool was not used for hypothesis generation or to write original content. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full term |

| IBS |

Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| FMT |

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation |

| IBD |

Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| MMC |

Migrating Motor Complex |

| SIBO |

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth |

| IF |

Intermittent Fasting |

| TRE |

Time-Restricted Eating |

| SCFA(s) |

Short-Chain Fatty Acid(s) |

| ER |

Endoplasmic Reticulum |

References

- Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016-5085(16)00223-7.

- Fikree A, Byrne P. Management of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clin Med. 2021;21(1):44–52.

- Kim JH, Lin E, Pimentel M. Biomarkers of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(1):20–6.

- Oka P, Parr H, Barberio B, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(10):908–17.

- Shiha MG, Aziz I. Review article: Physical and psychological comorbidities associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54 Suppl 1:S12–23.

- Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):133–46.

- El-Salhy M, Johansson M, Klevstul M, Hatlebakk JG. Quality of life, functional impairment and healthcare experiences of patients with irritable bowel syndrome in Norway: an online survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25(1):143.

- Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(9):1023–34.

- IFFGD’s IBS Patients’ Illness Experience and Unmet Needs Survey - IFFGD. https://iffgd.org/news/press-release/2020-iffgd-s-ibs-patients-illness-experience-and-unmet-needs-survey/.

- Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome. The Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1675–88.

- Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, Bengtsson U, mfl. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63(2):108–15.

- Capili B, Anastasi JK, Chang M. Addressing the Role of Food in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Management. J Nurse Pract. 2016;12(5):324–9.

- Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, Whorwell PJ. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53(10):1459–64.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-Reported Food-Related Gastrointestinal Symptoms in IBS Are Common and Associated With More Severe Symptoms and Reduced Quality of Life. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2013;108(5):634.

- Young E, Stoneham MD, Petruckevitch A, Barton J, Rona R. A population study of food intolerance. Lancet Lond Engl. 1994;343(8906):1127–30.

- Murray HB, Doerfler B, Harer KN, Keefer L. Psychological Considerations in the Dietary Management of Patients With DGBI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022.

- Valeur J, Øines E, Helvik Morken M, Juul Holst J, Berstad A. Plasma glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY levels are not altered in symptomatic fructose-sorbitol malabsorption. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(10):1212–8.

- Valeur J, Morken MH, Norin E, Midtvedt T, Berstad A. Carbohydrate intolerance in patients with self-reported food hypersensitivity: Comparison of lactulose and glucose. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(12):1416–23.

- Francis CY, Whorwell PJ. Bran and irritable bowel syndrome: time for reappraisal. Lancet Lond Engl. 1994;344(8914):39–40.

- Fritscher-Ravens A, Schuppan D, Ellrichmann M, Schoch S, Röcken C, Brasch J, Bethge J, Böttner M, Klose J, Milla PJ. Confocal endomicroscopy shows food-associated changes in the intestinal mucosa of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1012-1020.e4.

- Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Florens MV, Viola MF, Jain P, Decraecker L, Appeltans I, Cuende-Estevez M, Fabre N, Van Beek K, Perna E, Balemans D, Stakenborg N, Theofanous S, Bosmans G, Mondelaers SU, Matteoli G, Ibiza Martínez S, Lopez-Lopez C, Jaramillo-Polanco J, Talavera K, Alpizar YA, Feyerabend TB, Rodewald HR, Farre R, Redegeld FA, Si J, Raes J, Breynaert C, Schrijvers R, Bosteels C, Lambrecht BN, Boyd SD, Hoh RA, Cabooter D, Nelis M, Augustijns P, Hendrix S, Strid J, Bisschops R, Reed DE, Vanner SJ, Denadai-Souza A, Wouters MM, Boeckxstaens GE. Local immune response to food antigens drives meal-induced abdominal pain. Nature. 2021;590(7844):151–6.

- Pedersen N, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Wachmann H, Végh Z, Molzen L, Burisch J, Andersen JR, Munkholm P. Low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(18):3356–66.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67-75.e5.

- Algera JP, Demir D, Törnblom H, Nybacka S, Simrén M, Störsrud S. Low FODMAP diet reduces gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome and clinical response could be predicted by symptom severity: A randomized crossover trial. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2022;41(12):2792–800.

- Austin GL, Dalton CB, Hu Y, Morris CB, Hankins J, Weinland SR, Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Drossman DA. A Very Low-carbohydrate Diet Improves Symptoms and Quality of Life in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. juni 2009;7(6):706-708.e1.

- Nybacka S, Törnblom H, Josefsson A, Hreinsson JP, Böhn L, Frändemark Å, mfl. A low FODMAP diet plus traditional dietary advice versus a low-carbohydrate diet versus pharmacological treatment in irritable bowel syndrome (CARIBS): a single-centre, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024.

- Tuck CJ, Reed DE, Muir J, Vanner S. A236 A REAL-WORLD EVALUATION OF THE LOW FODMAP DIET IMPLEMENTATION: POOR COMPLIANCE IS SIGNIFICANTLY IMPROVED BY GUIDANCE FROM A DIETITIAN. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2(Suppl 2):461.

- Scarlata K, Eswaran S, Baker JR, Chey WD. Utilization of Dietitians in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Members of the American College of Gastroenterology. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol ACG. 2022;117(6):923.

- Ioniță-Mîndrican CB, Ziani K, Mititelu M, Oprea E, Neacșu SM, Moroșan E, mfl. Therapeutic Benefits and Dietary Restrictions of Fiber Intake: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients. 2022;14(13):2641.

- Heizer WD, Southern S, McGovern S. The Role of Diet in Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults: A Narrative Review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(7):1204–14.

- Wu S, Yang Z, Yuan C, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang S, Zhu S. Coffee and tea intake with long-term risk of irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2023;52(5):1459–72.

- Shaikh SD, Sun N, Canakis A, Park WY, Weber HC. Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Gut Microbiome: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(7):2558.

- Chong PP, Chin VK, Looi CY, Wong WF, Madhavan P, Yong VC. The Microbiome and Irritable Bowel Syndrome - A Review on the Pathophysiology, Current Research and Future Therapy. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1136.

- Vich Vila A, Imhann F, Collij V, Jankipersadsing SA, Gurry T, Mujagic Z, mfl. Gut microbiota composition and functional changes in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(472):eaap8914.

- Tap J, Derrien M, Törnblom H, Brazeilles R, Cools-Portier S, Doré J, mfl. Identification of an Intestinal Microbiota Signature Associated With Severity of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):111-123.e8.

- Halkjær SI, Lo B, Cold F, Højer Christensen A, Holster S, König J, Brummer RJ, Aroniadis OC, Lahtinen P, Holvoet T, Gluud LL, Petersen AM. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2023. 28;29(20):3185-3202.

- Lee J-Y, Bays DJ, Savage HP, Bäumler AJ. The human gut microbiome in health and disease: time for a new chapter? Infect Immun. 2024. 12;92(11):e0030224.

- Akdis CA. Does the epithelial barrier hypothesis explain the increase in allergy, autoimmunity and other chronic conditions? Nat Rev Immunol. 2021. 21(11):739-751.

- Parrish A, Boudaud M, Kuehn A, Ollert M, Desai MS. Intestinal mucus barrier: a missing piece of the puzzle in food allergy. Trends Mol Med. 2022. 28(1):36-50.

- Laudisi F, Di Fusco D, Dinallo V, Stolfi C, Di Grazia A, Marafini I, Colantoni A, Ortenzi A, Alteri C, Guerrieri F, Mavilio M, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Federici M, MacDonald TT, Monteleone I, Monteleone G.The Food Additive Maltodextrin Promotes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Driven Mucus Depletion and Exacerbates Intestinal Inflammation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7(2):457–73.

- Chassaing B, Koren O, Goodrich JK, Poole AC, Srinivasan S, Ley RE, mfl. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2015;519(7541):92–6.

- Szałwińska P, Włodarczyk J, Spinelli A, Fichna J, Włodarczyk M. IBS-Symptoms in IBD Patients—Manifestation of Concomitant or Different Entities. J Clin Med. 2021;10(1):31.

- Fairbrass KM, Costantino SJ, Gracie DJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. Baumgartner M, Lang M, Holley H, Crepaz D, Hausmann B, Pjevac P, Moser D, Haller F, Hof F, Beer A, Orgler E, Frick A, Khare V, Evstatiev R, Strohmaier S, Primas C, Dolak W, Köcher T, Klavins K, Rath T, Neurath MF, Berry D, Makristathis A, Muttenthaler M, Gasche C.2020;5(12):1053–62.

- Baumgartner M, Lang M, Holley H, Crepaz D, Hausmann B, Pjevac P, Moser D, Haller F, Hof F, Beer A, Orgler E, Frick A, Khare V, Evstatiev R, Strohmaier S, Primas C, Dolak W, Köcher T, Klavins K, Rath T, Neurath MF, Berry D, Makristathis A, Muttenthaler M, Gasche C. Mucosal Biofilms Are an Endoscopic Feature of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1245-1256.e20.

- Casén C, Vebø HC, Sekelja M, Hegge FT, Karlsson MK, Ciemniejewska E, Dzankovic S, Frøyland C, Nestestog R, Engstrand L, Munkholm P, Nielsen OH, Rogler G, Simrén M, Öhman L, Vatn MH, Rudi K. Deviations in human gut microbiota: a novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(1):71–83.

- Cox SR, Lindsay JO, Fromentin S, Stagg AJ, McCarthy NE, Galleron N, Ibraim SB, Roume H, Levenez F, Pons N, Maziers N, Lomer MC, Ehrlich SD, Irving PM, Whelan K. Effects of Low FODMAP Diet on Symptoms, Fecal Microbiome, and Markers of Inflammation in Patients With Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):176-188.e7.

- Norwitz NG, Soto-Mota A. Case report: Carnivore–ketogenic diet for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a case series of 10 patients. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1467475.

- Li S, Zhuge A, Wang K, Lv L, Bian X, Yang L, Xia J, Jiang X, Wu W, Wang S, Wang Q, Li L. Ketogenic diet aggravates colitis, impairs intestinal barrier and alters gut microbiota and metabolism in DSS-induced mice. Food Funct. 2021;12(20):10210–25.

- Kong C, Yan X, Liu Y, Huang L, Zhu Y, He J, Gao R, Kalady MF, Goel A, Qin H, Ma Y. Ketogenic diet alleviates colitis by reduction of colonic group 3 innate lymphoid cells through altering gut microbiome. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):154.

- Gubatan J, Kulkarni CV, Talamantes SM, Temby M, Fardeen T, Sinha SR. Dietary Exposures and Interventions in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Evidence and Emerging Concepts. Nutrients. 2023;15(3):579.

- Koppold DA, Breinlinger C, Hanslian E, Kessler C, Cramer H, Khokhar AR, Peterson CM, Tinsley G, Vernieri C, Bloomer RJ, Boschmann M, Bragazzi NL, Brandhorst S, Gabel K, Goldhamer AC, Grajower MM, Harvie M, Heilbronn L, Horne BD, Karras SN, Langhorst J, Lischka E, Madeo F, Mitchell SJ, Papagiannopoulos-Vatopaidinos IE, Papagiannopoulou M, Pijl H, Ravussin E, Ritzmann-Widderich M, Varady K, Adamidou L, Chihaoui M, de Cabo R, Hassanein M, Lessan N, Longo V, Manoogian ENC, Mattson MP, Muhlestein JB, Panda S, Papadopoulou SK, Rodopaios NE, Stange R, Michalsen A. International consensus on fasting terminology. Cell Metab. 2024;36(8):1779-1794.e4.

- de Cabo R, Mattson MP. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2541–51.

- Longo VD, Mattson MP. Fasting: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Cell Metab. 2014;19(2):181–92.

- Kanazawa M, Fukudo S. Effects of fasting therapy on irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Behav Med. 2006;13(3):214–20.

- Wang R, Lv X, Xu W, Li X, Tang X, Huang H, Yang M, Ma S, Wang N, Niu Y. Effects of the periodic fasting-mimicking diet on health, lifespan, and multiple diseases: a narrative review and clinical implications. Nutr Rev. 2024; nuae003.

- Roco-Videla Á, Villota-Arcos C, Pino-Astorga C, Mendoza-Puga D, Bittner-Ortega M, Corbeaux-Ascui T. Intermittent Fasting and Reduction of Inflammatory Response in a Patient with Ulcerative Colitis. Medicina (Mex). 2023;59(8):1453.

- Weill Medical College of Cornell University. The Impact of Time Restricted Feeding in Crohn’s Disease. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023. Report No.: NCT04271748. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04271748.

- Sinha SR. The Influence of a Fasting Mimicking Diet on Ulcerative Colitis. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023. Report No.: NCT03615690. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03615690.

- Sinha SR. Effects of an Intermittent Reduced Calorie Diet on Crohn’s Disease. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023. Report No.: NCT04147585. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04147585.

- Park JH, Kotani T, Konno T, Setiawan J, Kitamura Y, Imada S, Usui Y, Hatano N, Shinohara M, Saito Y, Murata Y, Matozaki T. Promotion of Intestinal Epithelial Cell Turnover by Commensal Bacteria: Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0156334.

- Barker N. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(1):19–33.

- Haasis E, Bettenburg A, Lorentz A. Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Immune Parameters and Intestinal Inflammation. Nutrients. 2024;16(22):3956.

- Deloose E, Janssen P, Depoortere I, Tack J. The migrating motor complex: control mechanisms and its role in health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(5):271–85.

- Vantrappen G, Janssens J, Hellemans J, Ghoos Y. The interdigestive motor complex of normal subjects and patients with bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine. J Clin Invest. 1977.

- Ducarmon QR, Grundler F, Le Maho Y, Wilhelmi de Toledo F, Zeller G, Habold C, Mesnage R. Remodelling of the intestinal ecosystem during caloric restriction and fasting. Trends Microbiol. 2023.

- Paukkonen I, Törrönen EN, Lok J, Schwab U, El-Nezami H. The impact of intermittent fasting on gut microbiota: a systematic review of human studies. Front Nutr. 2024.

- Pérez-Gerdel T, Camargo M, Alvarado M, Ramírez JD. Impact of Intermittent Fasting on the Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review. Adv Biol. n/a(n/a):2200337.

- Bagherniya M, Butler AE, Barreto GE, Sahebkar A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;47:183–97.

- Telpaz S, Bel S. Autophagy in intestinal epithelial cells prevents gut inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2023.

- Fu R, Liu S, Zhu M, Zhu J, Chen M. Apigenin reduces the suppressive effect of exosomes derived from irritable bowel syndrome patients on the autophagy of human colon epithelial cells by promoting ATG14. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21(1):95.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).