1. Introduction

Data Centric Artificial Intelligence (DCAI) has emerged as a crucial approach in improving the performance of AI systems. Unlike the traditional emphasis on designing increasingly complex AI models, DCAI focuses on optimizing the quality of the data used to train these models. Recent studies and implementations have shown that cleaner, more consistent and less noisy datasets can yield performance improvements equivalent to, or even surpass, those achieved by doubling or tripling the size of the dataset [

1]. This paradigm shift underscores the transition from a "big data" mindset to a "good data" philosophy.

The foundation of DCAI lies in the enhancement of various aspects of data preparation and management. Ensuring consistent labeling across output data is one crucial factor. For instance, labeling inconsistencies can introduce noise and degrade model performance, even when sophisticated models are employed. Moreover, addressing important edge cases in the input data ensures that the model learns robustly across a broader spectrum of scenarios. This can significantly reduce biases and blind spots in predictions, particularly in domains like healthcare and finance, where edge cases often carry high stakes.

Appropriately sizing datasets is another key tenet of DCAI. Instead of arbitrarily increasing dataset size, the focus is on selecting data that is representative of the problem space while avoiding redundant or irrelevant information. Tools such as active learning, which identify the most informative data points for labeling, have proven effective in achieving this balance [

2]. Furthermore, DCAI emphasizes the importance of monitoring and addressing data drift, a phenomenon where the statistical properties of input data change over time, potentially leading to model degradation. Techniques such as continuous monitoring and data versioning play a critical role in combating data drift [

3].

Data augmentation is a cornerstone technique in data-centric AI, often employed to address system performance issues or data scarcity. In cases where a system underperforms on certain inputs or where data availability is limited, particularly in high-stakes fields like medicine, data augmentation becomes an essential strategy for improvement. For instance, [

4] provides a comprehensive survey on the use of data-centric foundation models in health, exploring their applications across various domains. Similarly, a review in [

5] focuses on data-centric AI in healthcare, highlighting topics such as virtual and augmented reality applications in medicine, as well as advancements in AI, machine learning, deep learning, digital twins, and big data. The work in [

6] further demonstrates the utility of a data-centric approach by enhancing healthcare fraud classification performance using Medicare data. Meanwhile, [

7] offers a detailed review of datasets utilized in machine learning models for head and neck cancer, and [

8] dissects the concept of the digital twin in healthcare, providing valuable insight into its growing significance.

Expanding on AI’s importance in healthcare, many studies have explored its role in clinical decision-making. For example, [

9] investigates two case studies: maternal-fetal clinical decisions supported by IoT monitoring and deep learning, and COVID-19 predictions leveraging long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. The integration of AI, machine learning, and natural language processing in medical affairs is discussed in [

10], while [

11] addresses challenges faced by healthcare systems during the COVID-19 pandemic and proposes the use of blockchain and AI as solutions.

In addition to these high-level applications, wearable devices have emerged as transformative tools for real-time physiological data collection, fueling advancements in emotion prediction and healthcare monitoring. For instance, [

12] combines heart rate and speech data to predict participants’ emotions through multimodal data fusion. Similarly, [

13] explores the early detection of potential infections using both real and synthetic datasets comprising steps, heart rate, and sleep metrics. In intensive care units, [

14] applies novel deep learning methods to predict heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), showcasing the potential of data-centric approaches in critical care. Meanwhile, [

15] gathers heart rate data from wearable devices and user-reported emotions via a mobile app, utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and LSTMs to predict emotional states.

The SEED dataset is a collection of EEG datasets corresponding to specific emotions. It has several versions. Many studies have been conducted on the older versions of the dataset (SEED [

16], SEED-IV [

17], SEED-V [

18]). In [

19], emotion recognition is performed using a model based on Long Short-Term Memory neural networks. The model can distinguish non-linear relationships among EEG signals from different electrodes and aims to narrow the distribution gap between training and test sets. On the other hand, [

20] proposed a graph-based multi-task self-supervised learning model for emotion recognition. The work is divided into spatial and frequency jigsaw tasks, in addition to contrastive learning tasks, to learn more general representations. The two emotion recognition models, deep canonical correlation analysis and bimodal deep autoencoder, are compared in [

18]. The former demonstrated superior performance across different datasets and showed robustness to noise. In [

21], a regularized graph neural network is developed for EEG-based emotion recognition. The inter-channel relationships in EEG signals are modeled using adjacency matrices, and two regularizers are proposed to address cross-subject EEG variations.

To address the scarcity problem in the EEG data used for emotion recognition, some studies have focused on data augmentation. They demonstrate its effectiveness in improving prediction accuracy. Some use older versions of the SEED dataset [

22,

23], while others rely on different EEG datasets [

24,

25]. In [

22], a dual encoder variational autoencoder-generative adversarial network with spatiotemporal features is used to generate synthetic data. The average accuracy across all subjects increased by

compared to the original dataset. In [

23], the two deep generative models, variational autoencoder and generative adversarial network, are used as well, where full and partial augmentation strategies are applied. They observed that the number of synthetic data points needs to be 10 times less than that of the original data to achieve the best performance. During experiments, the EEG cap can slightly shift for the same person, or the electrodes can be in different positions for different participants due to their different head shapes. Therefore, rotational distortions around the y-axis and z-axis are performed to generate new synthetic data in [

24]. Artificial EEG trials are generated to reduce brain-computer interface calibration time in [

25]. Different combinations and distortions are applied to the original EEG dataset to generate augmented samples. This is done in the time, frequency, or time-frequency domains.

SEED-VII [

26], the dataset used in this study, is a recent addition to the SEED family. Few studies have utilized it to date. In [

27], Fourier-inspired techniques are introduced to separate periodic and aperiodic components of EEG signals for improved feature extraction. In [

28], a ChannelMix-based transformer and convolutional multi-view feature fusion network is proposed to enhance cross-subject emotion recognition by capturing richer spatiotemporal representations.

Despite these advancements, none of the existing studies have addressed the importance of cleaning EEG datasets of noisy data or investigated the impact of such preprocessing on system performance. In parallel, [

29] have investigated performance enhancement strategies for medical data by applying feature engineering methods tailored to neural networks. Their study demonstrates how handcrafted features can improve model performance, especially in data-scarce clinical environments. However, unlike our work, their approach focuses on modifying input features rather than improving data label quality or addressing label noise that is the key elements emphasized in the Data-Centric AI methodology adopted in this work. In [

26], electroencephalogram (EEG) signals were collected from 20 participants as they watched videos designed to elicit various emotions. The study employed the Multimodal Adaptive Emotion Transformer (MAET) model [

30] to predict emotions using EEG and eye movement data. In our work, we build upon the dataset collected in [

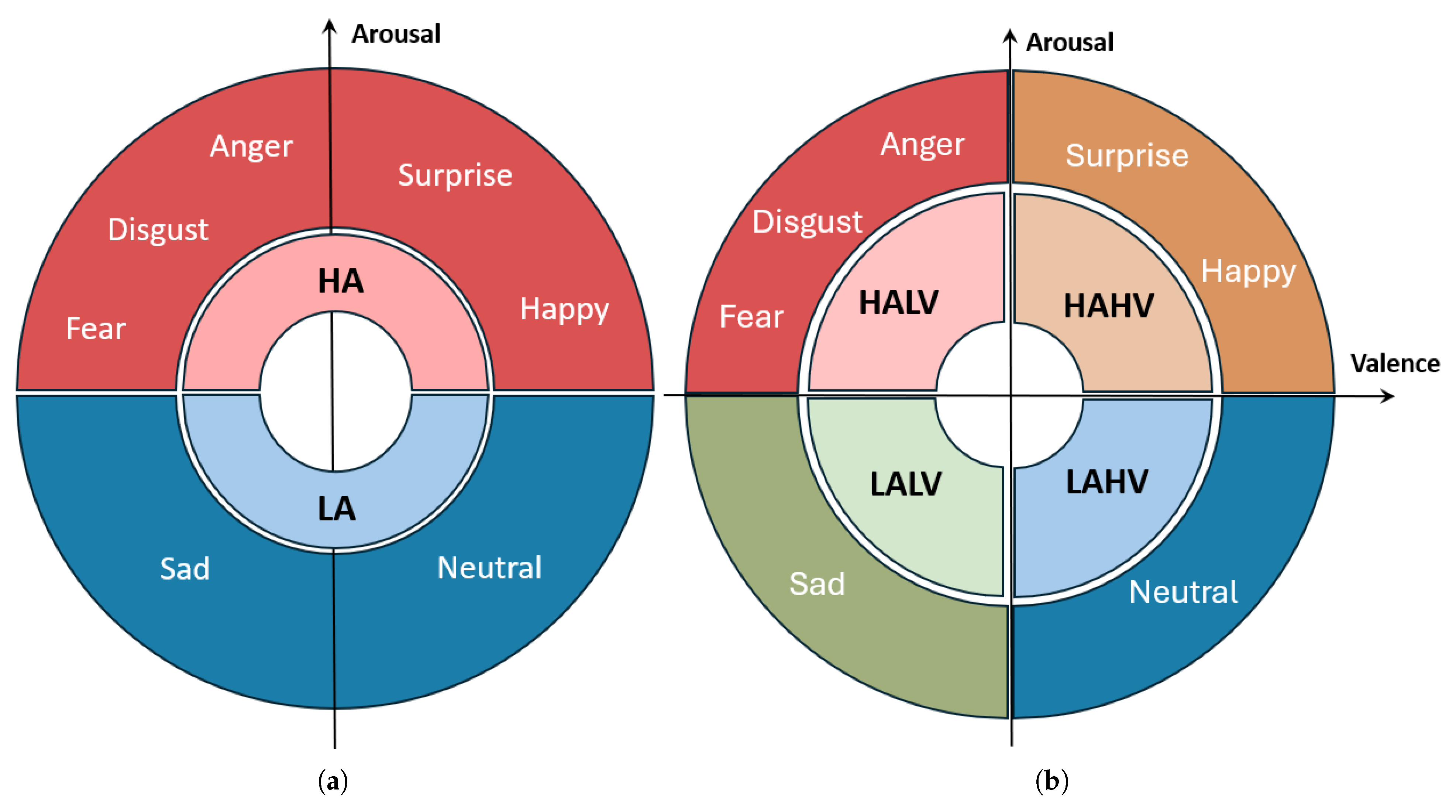

26] by focusing exclusively on EEG data as input. Using a deep learning model, we aim to predict the arousal levels of subjects as well as the four quadrants of emotions based on EEG data. Then, we predict each emotion separately. Furthermore, we demonstrate that employing data cleaning can significantly enhance system performance, making it a critical component of our approach. Then, we show the further improvements in performance that can occur due to data augmentation.

Given this background, the proposed emotion prediction framework has strong potential for real-world deployment in various domains, such as mental health monitoring, adaptive learning environments, user-centered design, and immersive technologies. By incorporating data-centric techniques that emphasize label quality and noise reduction, the system becomes more reliable and better suited for applications where emotional state tracking is critical. These include clinical diagnostics, emotion-aware interfaces, and personalized neurofeedback therapy.

Unlike prior work that applied data augmentation in isolation [

22,

23], this study uniquely combines participant-driven noise filtering with augmentation. By leveraging subjects’ self-reported emotion scores to systematically exclude ambiguous samples, we demonstrate a data-centric strategy that improves reliability while preserving robustness.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the dataset used in this study and explains the emotion categorization framework.

Section 3 discusses the architecture and layers of the deep learning model employed. The experimental results are presented and analyzed in

Section 4 Lastly,

Section 5 concludes the paper, summarizing key findings and outlining future research directions.

4. System Performance

To evaluate the effectiveness of Data Centric AI (DCAI) strategies, we tested the impact of data augmentation and noise reduction on model performance. First, all the original data is being shuffled and divided into K-folds, where the training set is assigned of these folds, while the kth fold is used for testing.

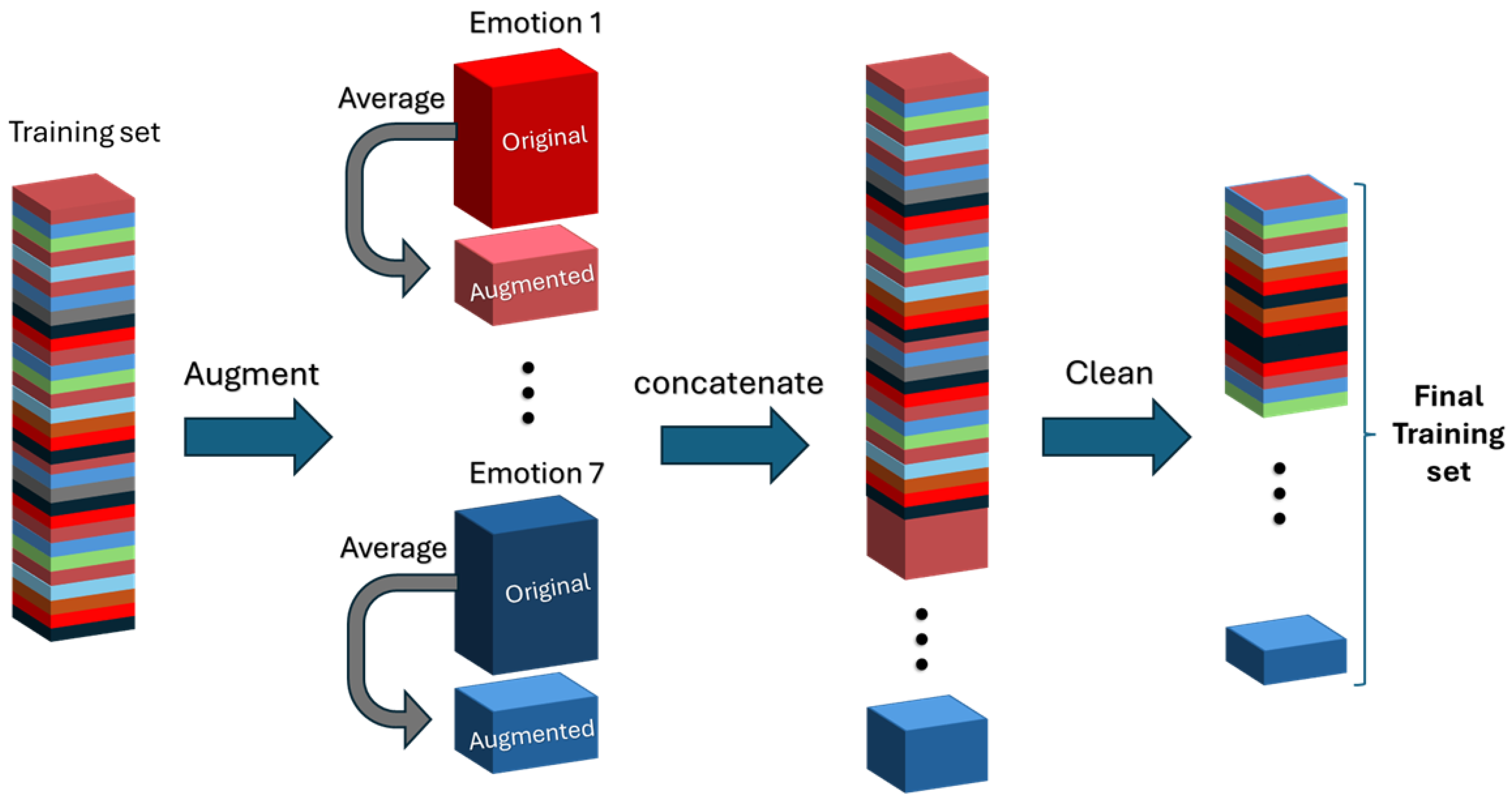

Using the training set, as illustrated in

Figure 2, the data corresponding to each emotion are extracted for the purpose of generating new augmented samples. The augmentation process involves creating synthetic data by averaging two or more existing data entries corresponding to the same emotion. These augmented data points are then added to the training set as new synthetic data. Before training, the dataset is cleaned by removing noisy data entries with emotion scores below a certain threshold.

Figure 2 illustrates this process applied to the training set, where both data augmentation and noise reduction are performed. Meanwhile, only noise reduction is applied to the test set. The test set is excluded from the augmentation process to prevent any information leakage into the training data, thus enhancing the generalizability of the results.

4.1. Data Augmentation and Noise Reduction

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Table 4, show the impact of data cleaning and data augmentation on model performance. The first column of each table indicates the maximum score threshold for removing data points from the dataset. Specifically, data points with this score or lower for an emotion are excluded from the training, and testing sets. For instance, a threshold of 0.2 means all data points with a score of 0.2 or less are removed. If "None" is specified, no data points are excluded, and the full dataset of 1,600 entries is used.

The accuracy and F1 score of the original dataset, without any data augmentation, were calculated as a baseline. As noisy data points are progressively removed (i.e., as the threshold score increases), both the accuracy and F1 score improve. This improvement reflects the data-centric approach of prioritizing data quality, even at the expense of reducing dataset size. For example, when all data points with a score of 0.9 or lower are removed, the dataset size shrinks dramatically from 1,600 to only 200 entries, yet the cleaner dataset enhances model performance.

Noise reduction in this context relies on participant feedback ratings collected during data acquisition. Without such feedback, it would be difficult to identify and filter out unreliable data points. This highlights a critical aspect of dataset construction: beyond labeling data, it is equally important to evaluate the reliability of those labels. Doing so enhances the overall quality of the dataset and improves the generalization of emotion recognition systems.

To address the trade-off between data cleanliness and dataset size, three data augmentation techniques were applied:

Augmentation 1: This technique involves averaging two consecutive data entries for each emotion to create new synthetic entries.

Augmentation 2: This approach generates even more synthetic data by averaging three, four, and five consecutive entries corresponding to the same emotion.

Gaussian: Synthetic data is generated by adding Gaussian noise to the original dataset[

35].

Next, we will study performance of the system, when noise reduction and data augmentation are used, in case of two-halves, four-quadrants, and seven-emotion classifications.

4.2. Impact of Predicting Two-Halves Emotions

Table 2 illustrates the effect of data cleaning and augmentation on predicting the two-halves emotion categories, high-arousal and low-arousal. The baseline case is the top-left entry of the table, which corresponds to using the original dataset without any data cleaning. As more data is cleaned from the original dataset, the system’s performance improves. At the threshold of

, the accuracy increased by

, rising from

to

, while the F1 score improved by

, from

to

.

The augmentation techniques slightly improved the model performance at each threshold compared to using only noise reduction on the original dataset. At lower thresholds (), the performance gains from the augmentation techniques are marginal, with improvements typically under , and thus less impactful. However, at the threshold, Augmentation 2 yields the highest overall performance, with substantial gains of in accuracy and in F1 score compared to the baseline.

These findings show that sufficient data size for each predicted half makes data augmentation have only a small effect on the performance. While it highlights the importance of data cleanliness on the performance of the system. This exemplifies the DCAI philosophy of enhancing model performance through high-quality data.

4.3. Impact of Predicting Four-Quadrant Emotions

To further analyze the impact of DCAI, we extend our study to predicting four-quadrant emotions based on the Russell 2D model. Unlike binary classification (HA vs. LA), this experiment introduces four distinct emotion categories (HAHV, HALV, LALV, and LAHV), requiring the model to distinguish both arousal and valence levels.

Table 3 presents the accuracy and F1 score results for four-quadrant classification using the

Original,

Augmentation 1,

Augmentation 2, and

Gaussian datasets. The key findings are: the accuracy and F1 scores for the four-quadrant classification are lower than those reported in

Table 2 for the binary classification task. This is expected since splitting data into four classes reduces the number of samples per category, making training more challenging. The F1 score is lower than accuracy in all cases. This is due to class imbalance, where LALV (Sad) and LAHV (Neutral) have significantly fewer data points compared to HALV and HAHV. This also means that the scheme achieving the best F1 score may differ from the one achieving the best accuracy at certain threshold values.

According to

Table 3, noise reduction has a clear impact on classification accuracy, as demonstrated by the results on the original dataset compared with the augmentation methods. Accuracy improved by up to 13.83%, while F1 score increased by only 2.07% at the

threshold. Augmentation 1 and Augmentation 2 achieve the highest accuracies when the threshold is below

, though the improvements over noise reduction alone are modest. Augmentation 2 consistently yields the highest F1 scores when the threshold is below

, suggesting that as the number of augmented samples increases, the model becomes more effective at handling class imbalances. At thresholds of

and higher, the Gaussian scheme demonstrates the strongest overall performance. Compared to the baseline, the Gaussian method at a threshold of

achieves the highest accuracy with a increase of

, while Augmentation 2 at a threshold of

yields the highest F1 score with an improvement of

. These results indicate that for unbalanced datasets, noise reduction is highly effective in boosting accuracy, whereas data augmentation plays a more significant role in improving the F1 score.

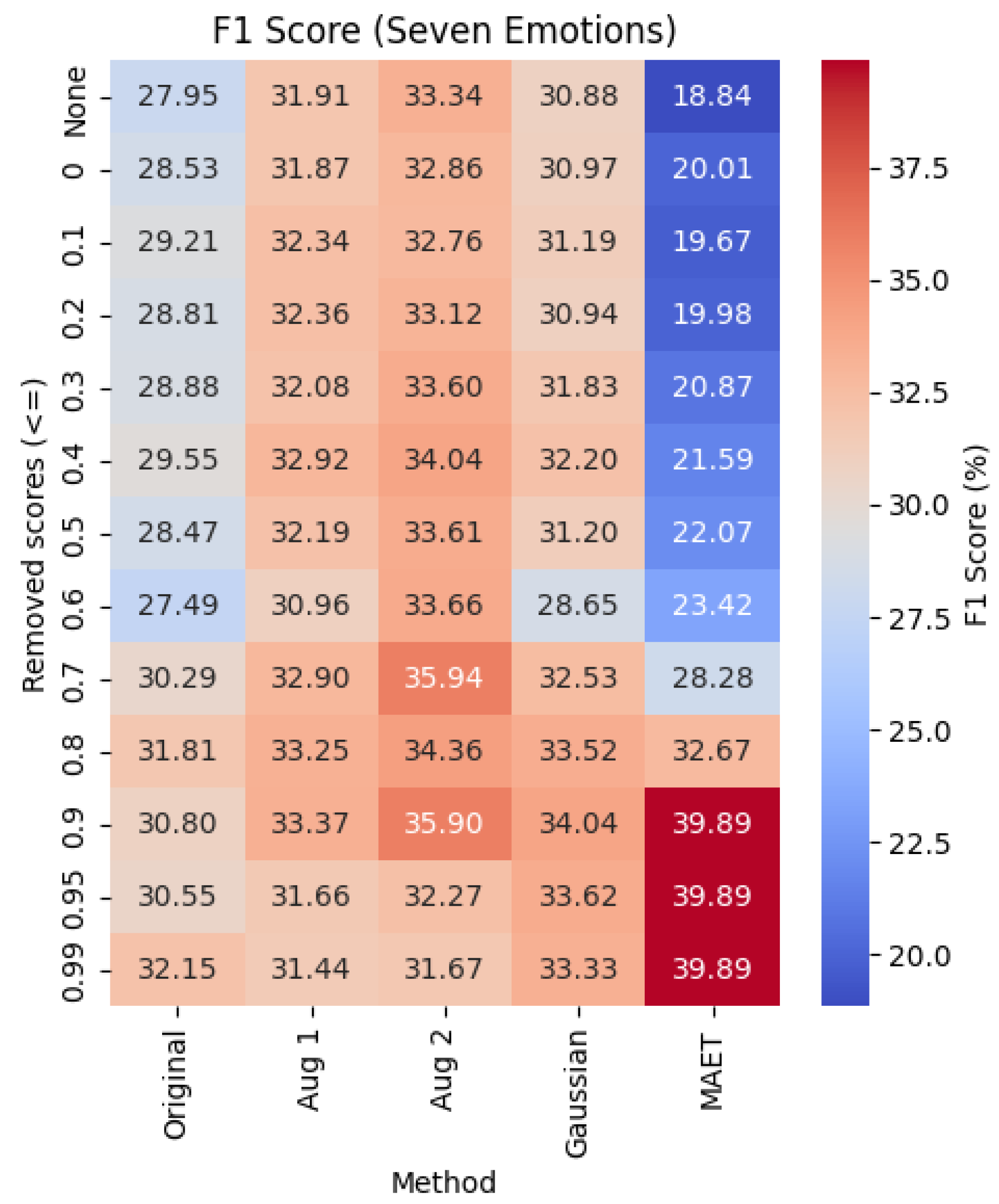

4.4. Impact of Predicting Seven Emotions

To facilitate comparison with prior work, we evaluate system performance by estimating each emotion in the dataset individually. This classification strategy substantially reduces the amount of data available per emotion class, leading to lower accuracy and F1 scores compared to the two-halves and four-quadrant classification approaches.

Table 4 presents the accuracy and F1 scores for the seven-emotion classification task under five different schemes:

Original,

Augmentation 1,

Augmentation 2,

Gaussian, and

MAET. MAET, introduced in [

26], stands for

Multimodal Adaptive Emotion Transformer. For this experiment, the learning rate was set to

, the weight decay to

, and the embedding dimensionality to 64. The results show that noise reduction alone, with a threshold of

, improves prediction accuracy by

, while the F1 score increases by

. Augmentation 2 yields the highest accuracy and F1 scores when the threshold is less than or equal to

, with accuracy gains ranging from

to

. At thresholds of

or higher, MAET demonstrates the best overall performance. These findings highlight the complementary benefits of combining data cleaning with advanced deep learning models. Notably, the superior performance of the MAET model is primarily due to its sophisticated architecture rather than data-centric strategies, emphasizing the importance of model complexity in addition to data quality. The highest performance is observed at a threshold of

or above, with an accuracy increase of

and an F1 score improvement of

over the baseline.

Unlike the four-quadrant classification, the seven-emotion dataset is more balanced, with only the neutral class being underrepresented. This balance contributes to consistent improvements in both accuracy and F1 scores across most thresholds when data augmentation is applied.

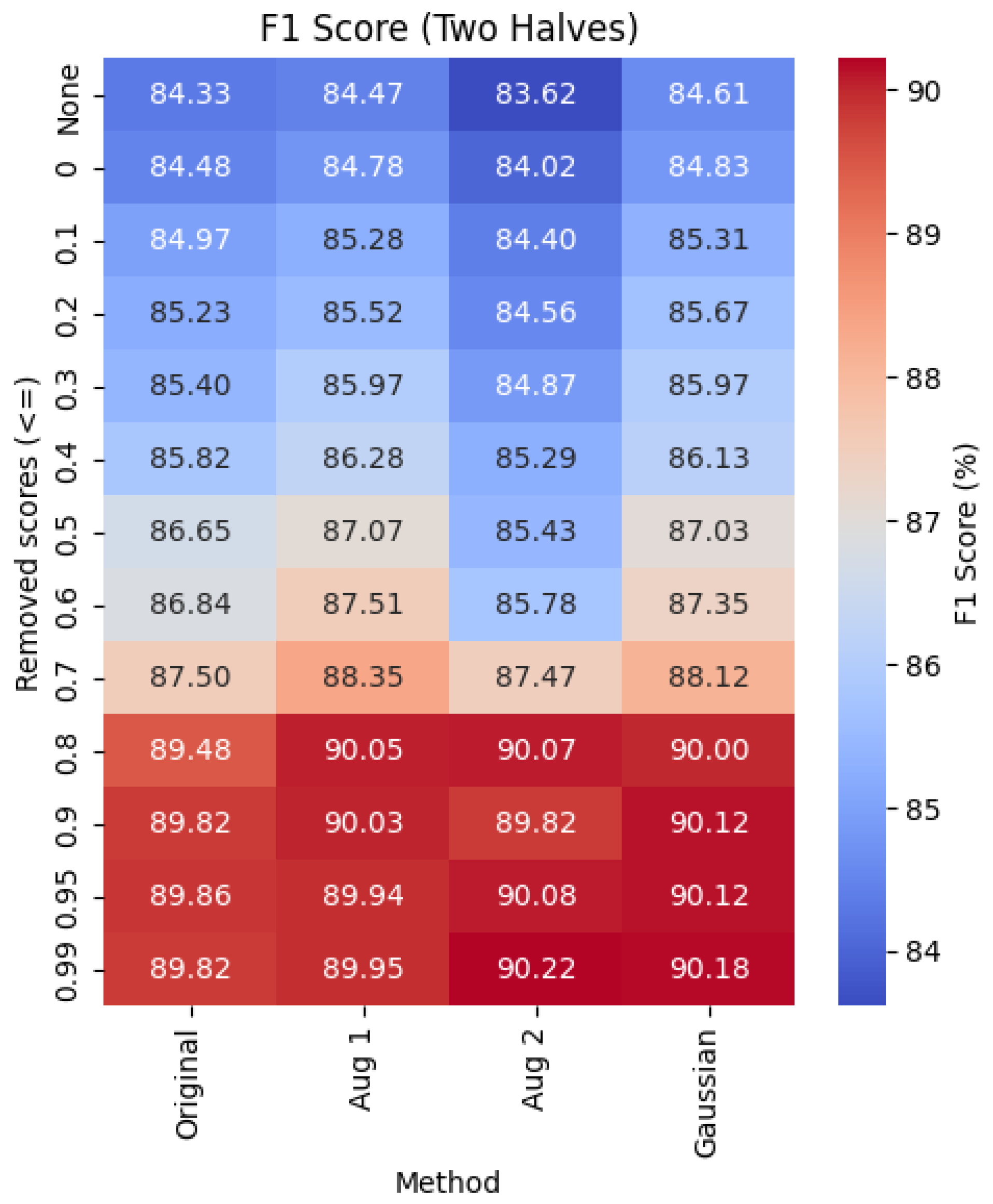

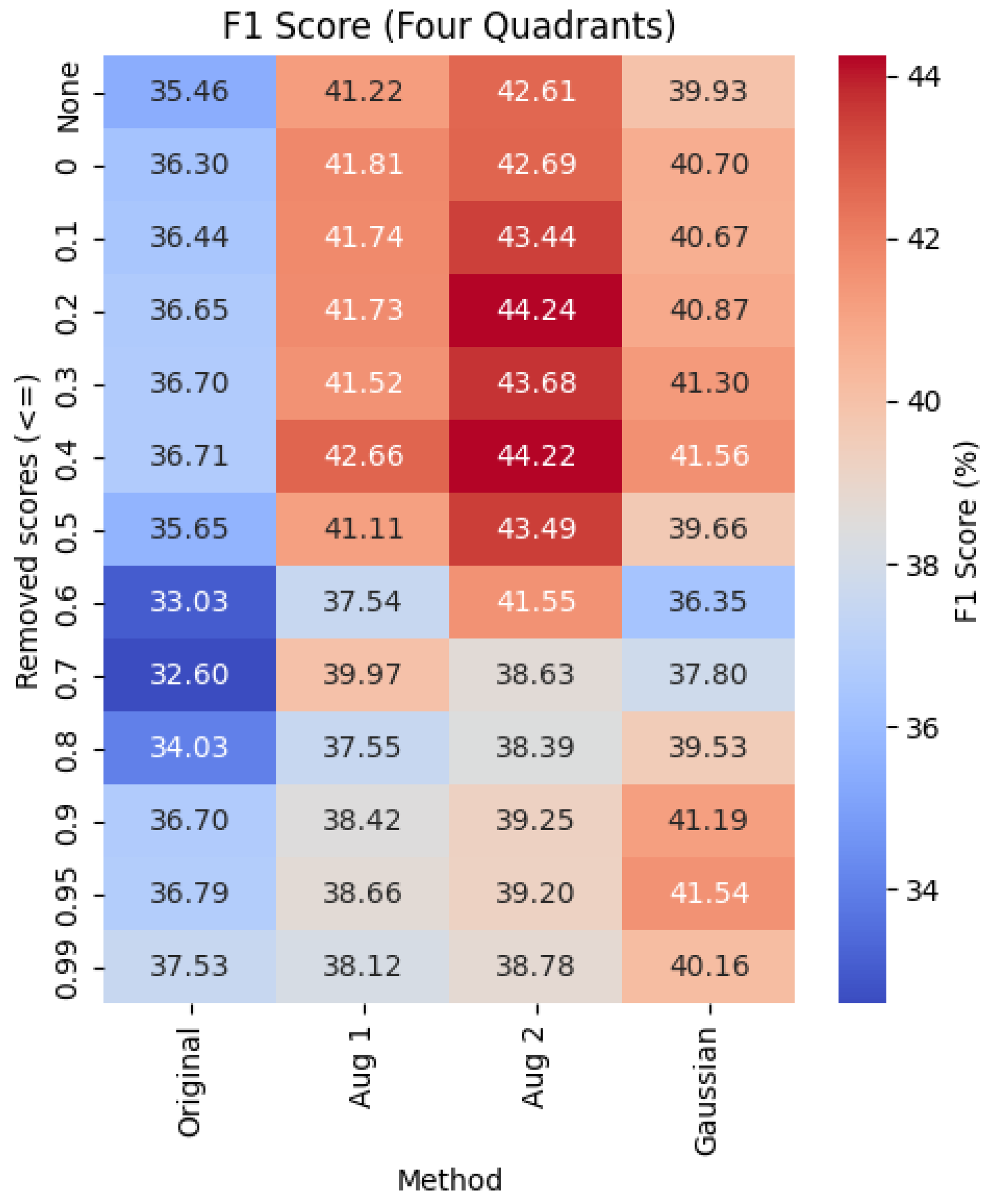

Figure 3,

Figure 4, and

Figure 5 present heatmap visualizations of the F1 scores under different data preprocessing schemes. These heatmaps provide a visual summary that complements the table based analysis by highlighting the best-performing augmentation methods across classification settings. These figures illustrate the impact of our proposed data augmentation strategies:

Augmentation 1,

Augmentation 2, and

Gaussian noise injection across three emotion classification settings: Two Halves, Four Quadrants, and Seven Emotions. The heatmaps reveal how each method performs across a range of noise thresholds, providing a detailed view of the effectiveness of augmentation in improving model performance, particularly in handling class imbalances. These augmentation methods are evaluated alongside three baseline approaches found in the literature: (1) the

Original training setup without any cleaning or augmentation, (2) the

Gaussian noise augmentation applied to the full dataset without cleaning, and (3) the

MAET model [

26], which is included only in the Seven Emotions scenario.

It is important to note that while Gaussian augmentation has been previously explored, applying noise cleaning whether to the Original, Gaussian, or MAET setups, constitutes a novel contribution of this work. Therefore, only the top-row entries (i.e., with "None" in the first column) in

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Table 4 represent methods from the existing literature. All subsequent rows, which incorporate threshold-based data filtering, are part of our proposed DCAI strategy.

Among the proposed augmentation strategies, Augmentation 2 yields the best performance in the Seven Emotions setting. It raises the F1 score from 27.95% (Original, unfiltered) to 35.94% (at threshold 0.7), marking a relative improvement of approximately 28.6%. However, the highest overall F1 score of 39.89% is achieved by the MAET model at a threshold of 0.9, highlighting the potential of combining advanced model architectures with noise-reduced training data.

Similarly, in the Two Halves configuration (

Figure 3), Augmentation 2 achieves the best F1 score of 90.22% at a threshold of 0.99, improving upon the Original setup’s 84.33% by approximately 7.0%

In the Four Quadrant configuration (

Figure 4), Augmentation 2 achieves the highest F1 score of 44.24% (at a 0.2 threshold), improving over the baseline 35.46% by approximately 24.7%.

These results demonstrate that the augmentation pipeline significantly enhances emotion classification performance across a range of model variants and label structures, outperforming both standard training and previously published methods such as MAET.

Table 5 summarizes the best performing F1 scores achieved in different emotion classification setups (Two Halves, Four Quadrants, and Seven Emotions), along with the corresponding data cleaning thresholds. The results show that the proposed augmentation strategies significantly enhance performance.

Specifically, Augmentation 2 achieves F1 score improvements of 7.0% in the two-halves task (at a threshold of 0.99), and 24.7% in the four-quadrant task (at a threshold of 0.2), relative to their respective baselines. In the seven-emotions setting, the best overall F1 score of 39.89% is achieved by the MAET model at a threshold of 0.9, representing a 42.7% improvement over the original baseline. For comparison, the best F1 score from our augmentation strategies in this setting is 35.94% using Augmentation 2 at a threshold of 0.7, yielding a 28.6% gain.

These findings indicate that DCAI-driven techniques, done by data cleaning and augmentation, play a crucial role in improving performance, particularly for fine-grained emotion classification tasks. The increase in data points through augmentation helps address class imbalance, which is essential for predicting emotions with higher granularity.

5. Conclusion

This work presents a data-centric framework for EEG-based emotion recognition, addressing challenges of limited and noisy datasets. The study demonstrates that significant gains in accuracy and F1 score can be achieved by combining participant-driven noise filtering with strategic data augmentation.

Across binary, four-quadrant, and seven-emotion classifications, data cleaning consistently improved performance, with augmentation yielding the largest gains in the seven-emotion setting. The four-quadrant and seven-emotion tasks proved more challenging due to class imbalance, highlighting the importance of targeted augmentation in handling data scarcity and imbalance.

While the MAET model achieved the highest performance in the seven-emotion task, this advantage stemmed from its architectural sophistication rather than data-centric steps, underscoring the complementary role of our approach. The novelty of this work lies not in proposing new architectures, but in showing that systematic noise filtering guided by participant scores, coupled with augmentations, produces consistent, replicable improvements across multiple classification levels.

By demonstrating that high-quality data can rival or even surpass the benefits of architectural complexity, this study offers a practical and reproducible framework for advancing emotion recognition in healthcare applications such as mental health monitoring, adaptive learning, and emotion-aware interfaces. Future work will extend these strategies to multimodal signals and investigate their impact in real-world clinical environments.