1. Introduction

In the age of AI, software developers began to integrate multiple AI-based tools at various stages of the software development life cycle (SDLC) [

1,

2]. These applications include automatic code generation, assistance in writing technical documentation, revision, and error detection. Currently, tools such as GitHub Copilot, Amazon CodeWhisperer, Tabnine, and even ChatGPT represent a new form of collaboration between humans and language models [

3,

4].

As a special case, ChatGPT has proven in recent months to be a versatile tool that can assist developers not only in programming tasks but also in understanding requirements, generating examples, optimizing code, and explaining complex concepts in natural language [

4,

5].

However, despite its growing adoption, there are currently no formal guidelines to guide developers on its optimal use, nor are there universal standards to ensure the quality and ethics of the results obtained by these technologies.

This study aims to analyze the optimal ways to integrate Artificial Intelligence into the software development life cycle, considering both its current capabilities and limitations. The purpose of this reflection is to contribute to the formulation of a strategic and sustainable approach that allows taking full advantage of the potential of AI without compromising the integrity of the software engineering process or the quality of the products generated.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the ability of machines, such as humans, to use algorithms, learn from data, and apply what has been learned in decision-making processes. However, unlike humans, AI-based devices do not require rest and can simultaneously analyze large volumes of information [

6,

7].

Since 20th century, AI has captured the interest of scientists, engineers, and philosophers. The concept first emerged in the theoretical work of Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in 1943 [

8], who proposed a mathematical model of artificial neurons inspired by the behavior of biological neurons. This model, known as the "McCulloch-Pitts logical neuron," uses a network of binary units to represent the logical functions of a neuron, thus laying the foundation for computational thinking and neural networks, which decades later would lead to the development of deep learning.

Seven years later, in 1950, mathematician Alan Turing published his article "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" [

9] in which he proposed that machines could imitate human thought processes. This gave birth to the famous Turing Test as a method for evaluating a system's intelligence. Later, in 1956, John McCarthy and other scientists organized the Dartmouth Workshop [

10], where the term Artificial Intelligence was coined for the first time, and is considered the official starting point of AI as a discipline.

In the early decades, AI focused on the development of expert systems such as Eliza in 1966 [

11], developed by Joseph Weizenbaum, Eliza was one of the first computer programs designed for natural language processing, which allowed conversations with humans, functioning as a psychologist that recognized keywords and, when asked for help, responded with words based on a specific variety of topics; if it did not find a concept, it asked questions related to the dialogue.

In 1997, IBM's Deep Blue [

12] became the first computer system to defeat that year’s world chess champion, Garry Kasparov; Deep Blue victory in a six-round marathon marked a turning point in the field of computing, heralding a future where supercomputers and artificial intelligence could simulate human thought.

[

13] directed by Henry Markram, the Blue Brain Project was born in 2005 with the goal of creating a biologically accurate simulation of the structure and function of the human brain. Over the years following the project's publication, remarkable milestones that advanced our understanding of brain function. The models developed in this project helped better understand the electrical and chemical activity of neurons, synaptic plasticity, and neural coding.

In 2011, IBM made another contribution to Artificial Intelligence, with the use of IBM Watson technology [

14], which was featured in a national television quiz show. The open domain question and answer system beat the top two ranked players in a game of Jeopardy!

By 2014, and for the first time since Turing Test was created, a computer program was able to pass it, convincing 33 % of the jurors that it was a human answering the test [

15]. Eugene Goostman is a chatbot or computer program designed to behave during a conversation like a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy.

2. Materials and Methods

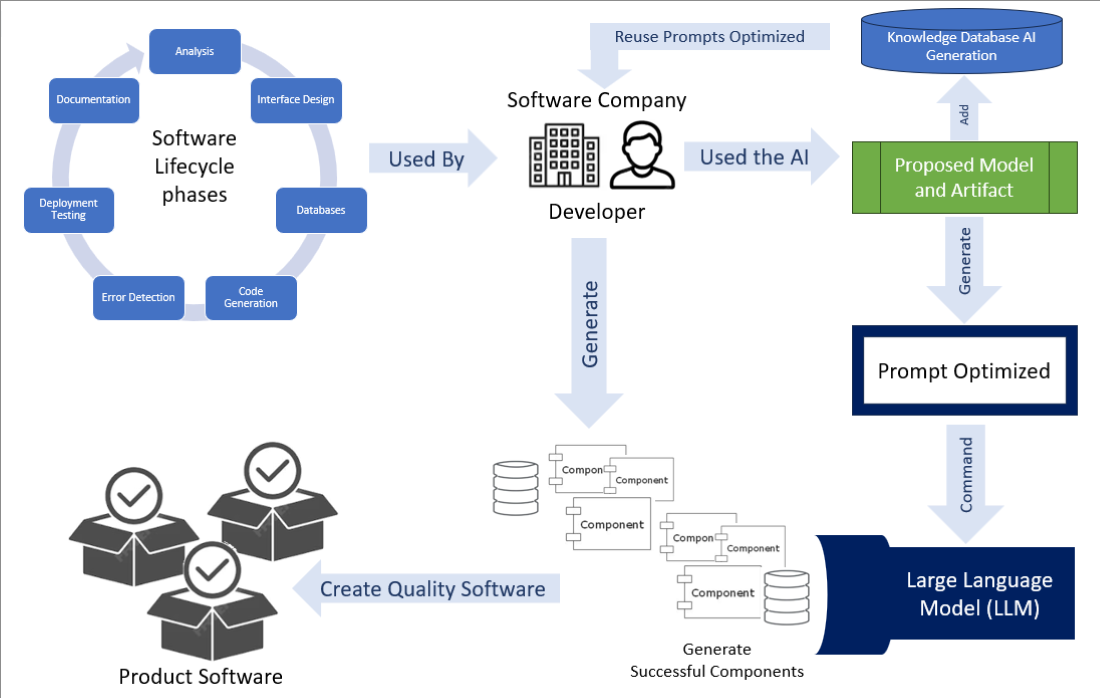

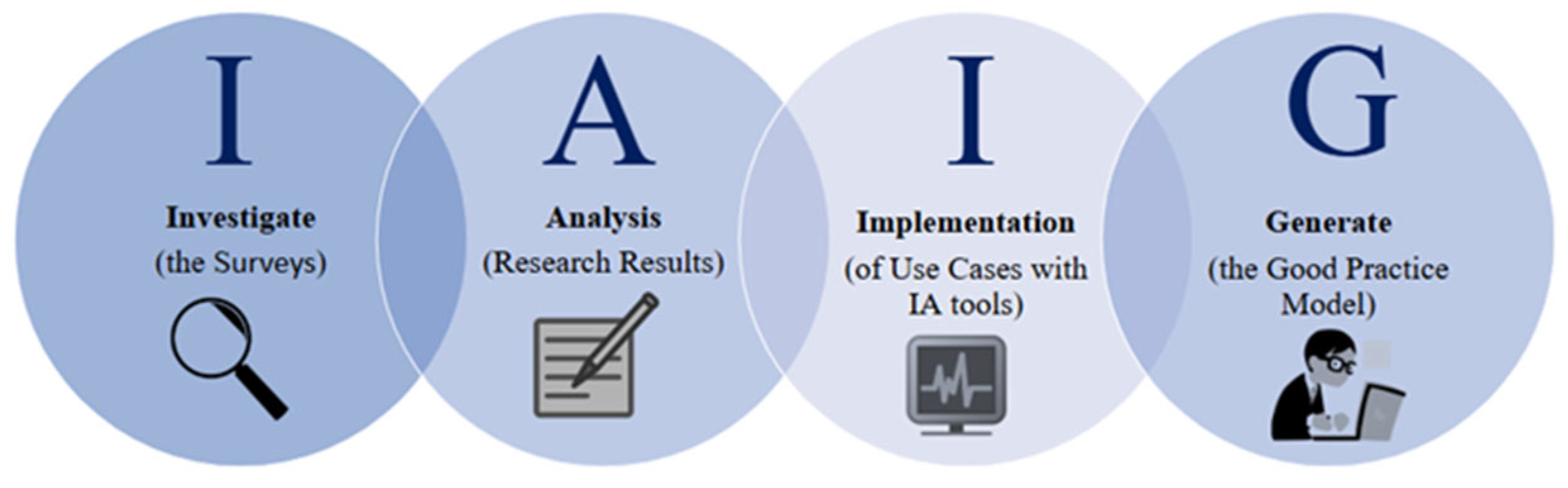

This study was structured into four phases, as shown in

Figure 1. In the Investigate phase, a set of items was designed for the data collection instrument. These items were developed based on the stages of the software development life cycle, as well as the dependent and independent variables of the case study. The Analysis phase allowed us to identify the maximum and minimum values in the collected data, thus facilitating a more precise interpretation of the results.

Subsequently, the Implementation phase consisted of experimenting with the initially identified AI tools. Finally, in the Generate phase, a best practice model was developed for the appropriate use of Artificial Intelligence across the different stages of the software development life cycle.

2.1. Investigate Phase

During the research phase, the most representative stages in the software development process were modeled, based on established theoretical frameworks [

1,

2].

Figure 2 presents a schematic representation of these stages highlighting where AI can have a major impact or is already being actively applied.

Subsequently, the study’s research variables [

20,

21] were established and organized into five thematic categories for analytical purposes: participant profile, technical specialization, use of AI tools, risk perception, and regulatory considerations, as shown in

Table 1.

Finally, the items that made up the results-obtaining [

22,

23] device were written, that is, the applied questionnaire. To ensure coherence and validity, the questions were inspired by instruments previously validated in related research studies [

24,

25]. Each question was carefully designed to be clear and understandable to participants.

The questionnaire included closed-ended and multiple-choice questions [

26], enabling quantitative analysis of the data [

27]. Standardization of the artifact also ensured that each item was directly linked to a specific variable and corresponded to a particular phase of the software development process, thus facilitating subsequent analysis and interpretation.

2.2. Analysis Phase

In the second phase, a data collection instrument (survey) was used. This collection was conducted online through Google Forms [

28,

29], ensuring access to a diverse sample of participants at both national and international levels.

A detailed analysis of the results was subsequently conducted to gain insight into participants’ profiles, perceptions, practices, and concerns regarding the use of AI in the software development life cycle.

The collected data were organized according to the study variables defined in Investigate Phase, allowing the identification of trends and potential implications for both professional practice and future research.

2.2.1. Participant Profile

The instrument was applied to a total of 200 people divided into two groups:

50 programming students from the state of Tabasco, Mexico.

150 active professionals in the software development field, with work experience in various sectors and regions of the country.

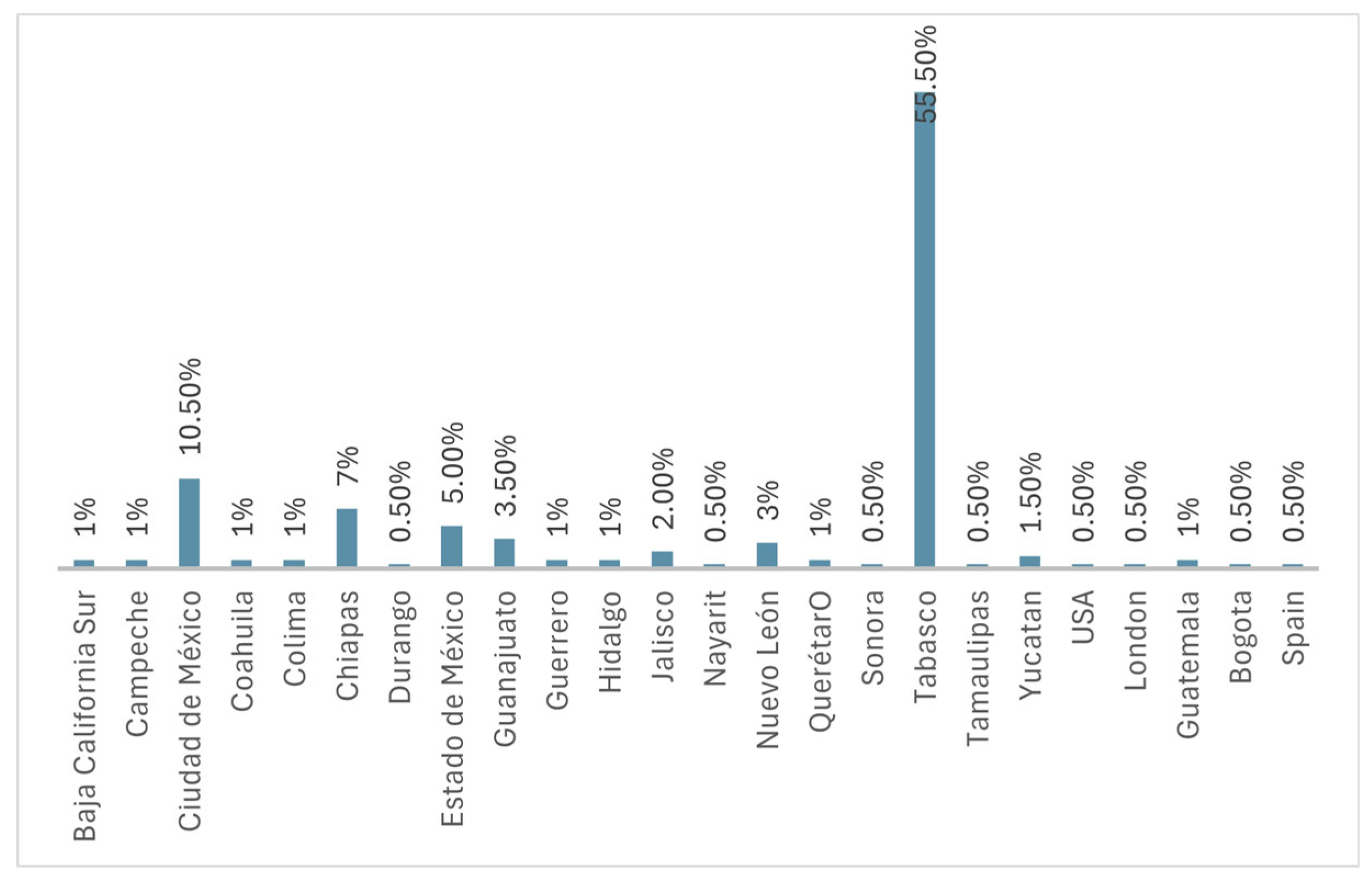

Responses from the second group came from various states, highlighting the state of Tabasco (55.5 %) and Mexico City (10.5 %) having the highest participation (

Figure 3).

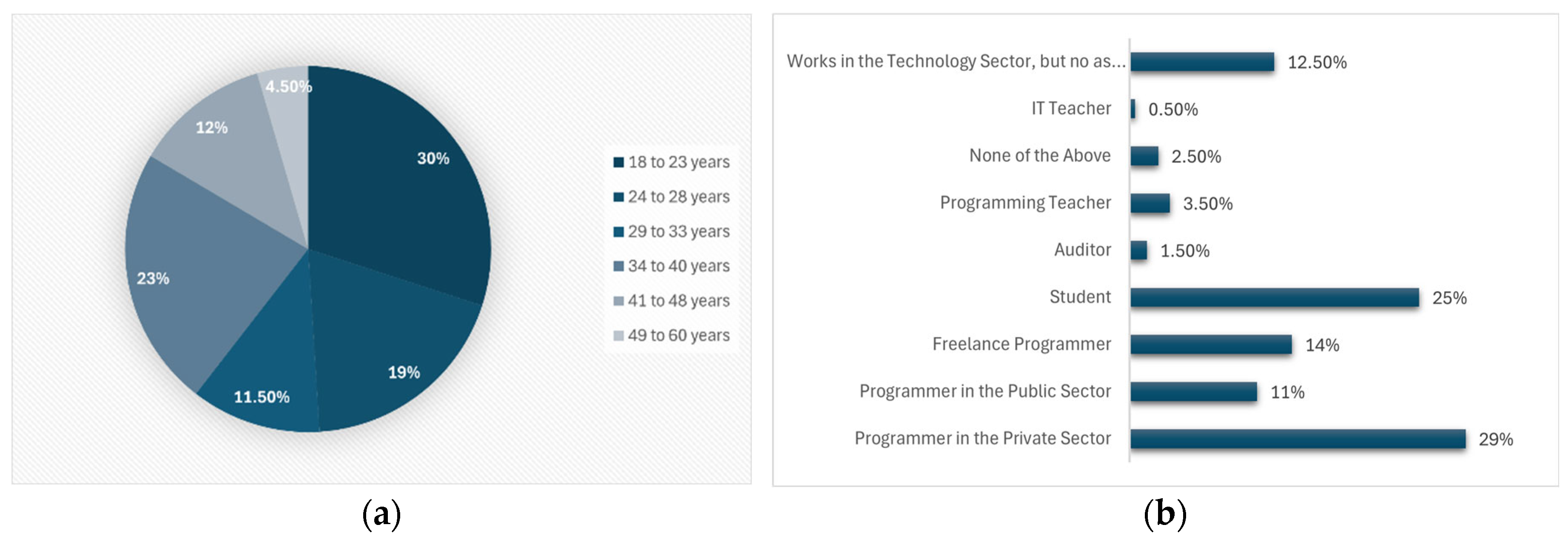

The graphs in

Figure 4 show the age groups and professional status of the people surveyed. The graph (

a) shows that the largest percentage of respondents (30 %) were in the age group of 18 to 23 years, followed by those aged 34 to 40 (23 %) and those aged 24 to 28 (19 %). This suggests that the use of AI tools is particularly prevalent among young adults.

The graphic

(b) in

Figure 4 shows that 29 % of respondents were developers in the private sector, 25 % were programming students, 14 % worked as freelancers, and 11 % were developers in the public sector.

2.2.2. Technical Specialization

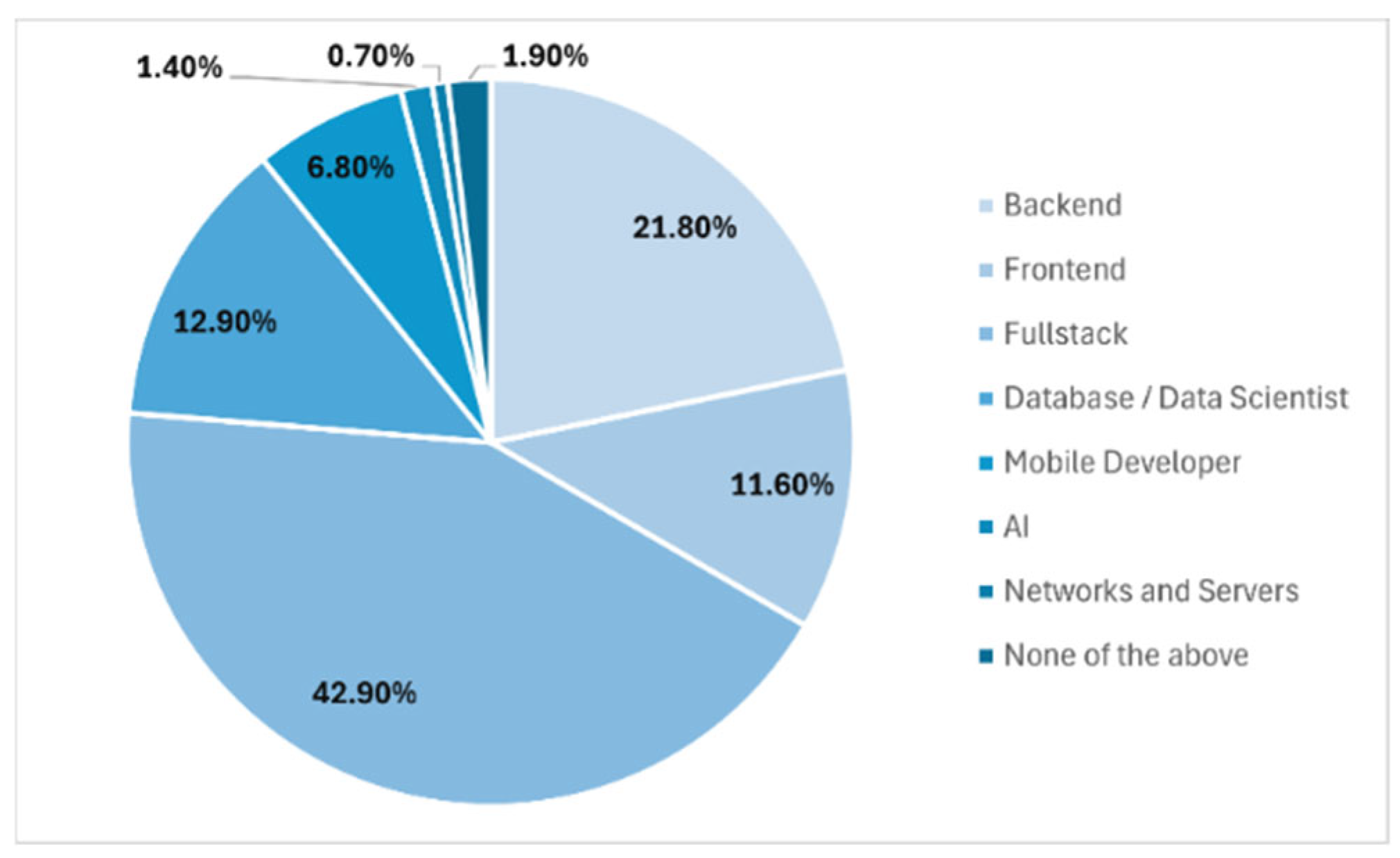

Figure 5 shows us the areas in which the surveyed developers were focused: 42.9 % were Full Stack developers, 21.8 % were backend developers, and 12.9 % specialized in database development and administration.

2.2.3. AI Tools

Below are the results of the survey questions regarding the most commonly used tools in each established development phase. Iti’s important to notice that this section included multiple-choice answers, so that users could select more than one response.

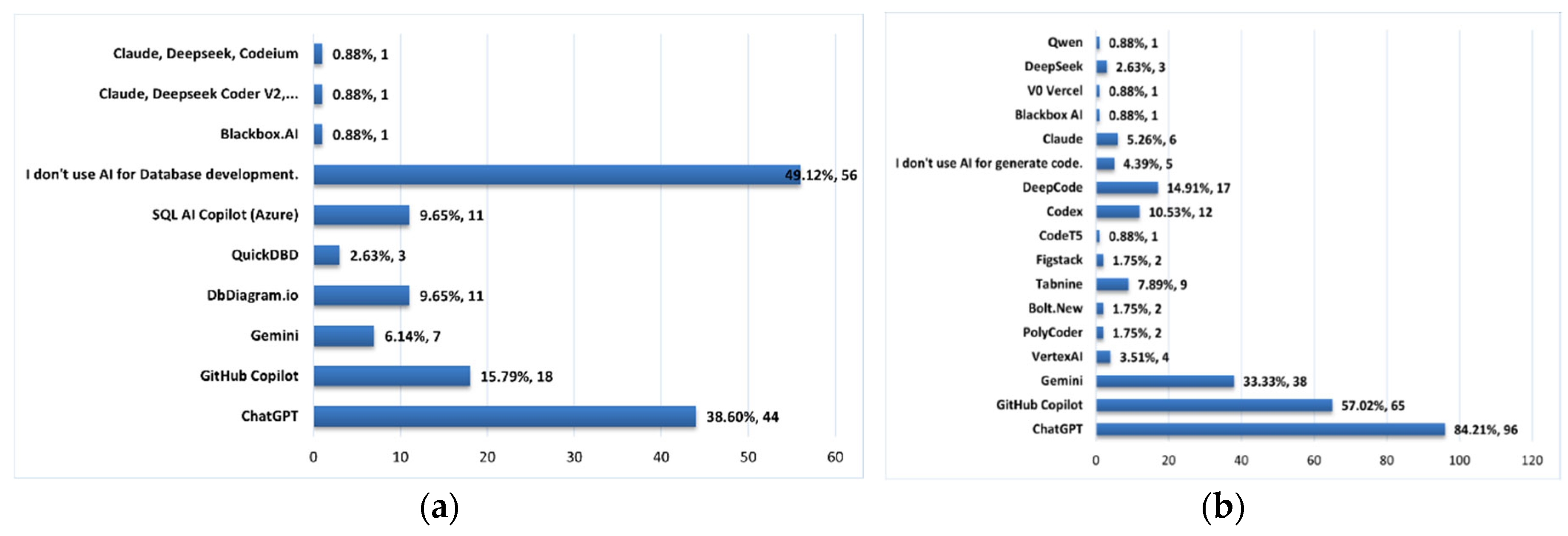

The graph

(a) in

Figure 6 shows that most respondents (49.12%) did not use AI tools for database development. Among those who do, ChatGPT was the most popular (38.6%), followed by GitHub Copilot (15.79%), DbDiagram.io, and SQL AI Copilot (9.65% each). This indicates a growing but still limited use of AI at this stage.

The graphic

(b) in

Figure 6 demonstrates that most respondents (84.21%) have adopted ChatGPT as a tool during the coding phase, followed by GitHub Copilot (57%) and Gemini (33.3%). Only 4.39% indicated they don’t use AI tools for code generation.

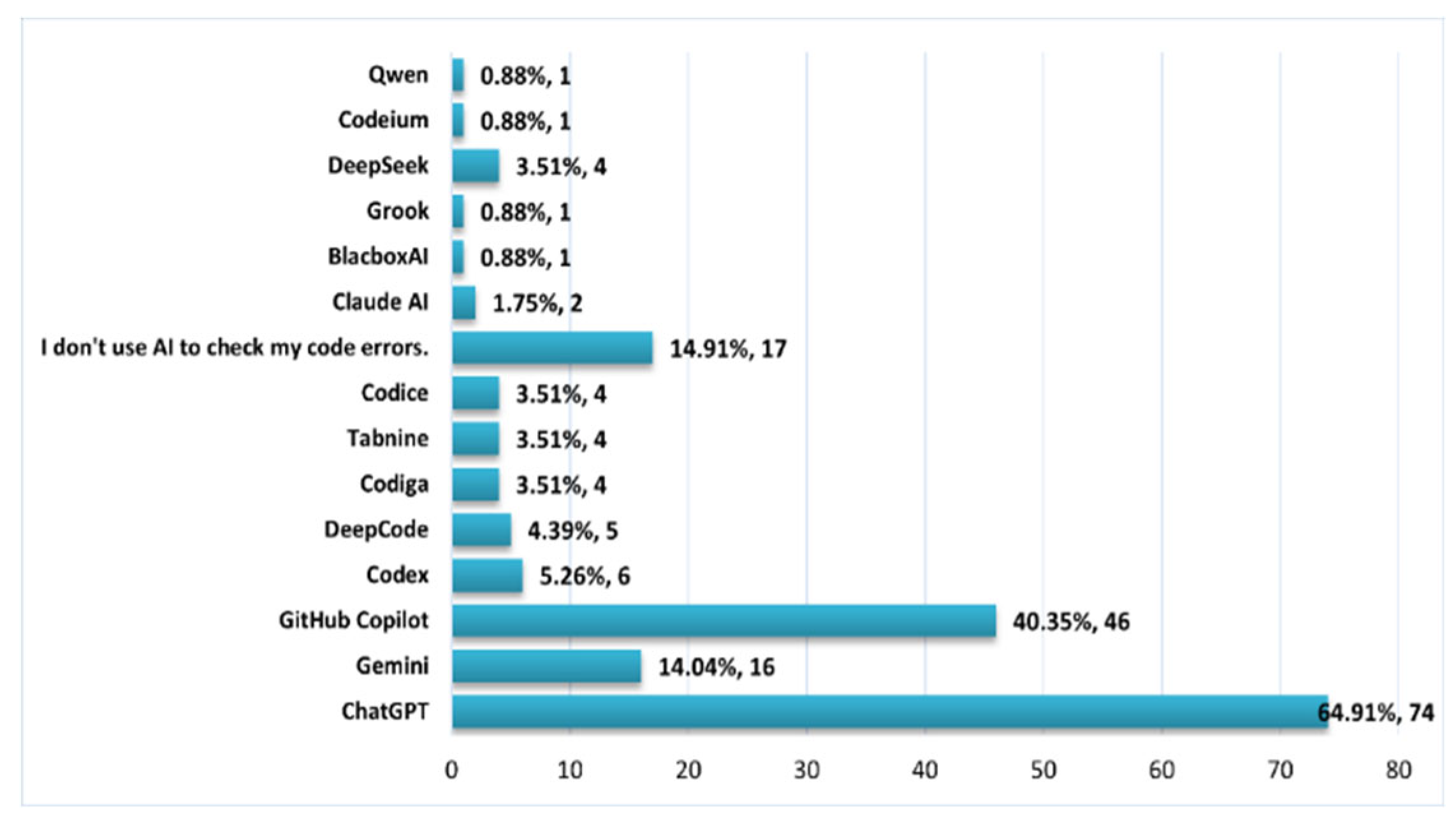

Figure 7 shows the AI tools used during the error detection phase, where 64.91% of respondents use ChatGPT in this phase, followed by GitHub Copilot (40.35%) and Gemini (14%).

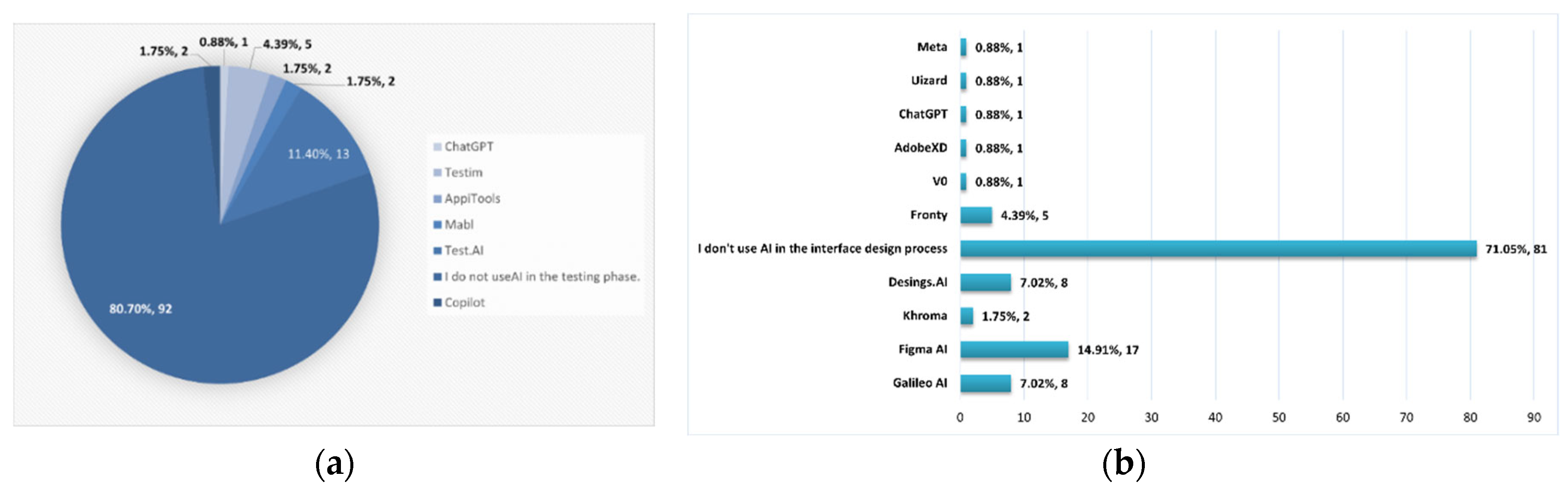

Figure 8 section

(a) shows that during the testing phase, most developers (80.7 %) did not use AI tools. Among those who do, Testa.AI (11.4 %) and Testim (4.39 %) are the most used.

For interface design section

(b) in

Figure 8 shows that, the majority of respondents (71.05 %) don’t use AI tools. However, among those who do, FigmaAI is the most used (14.9 %), followed by Galileo AI and Designs AI (7.02 %).

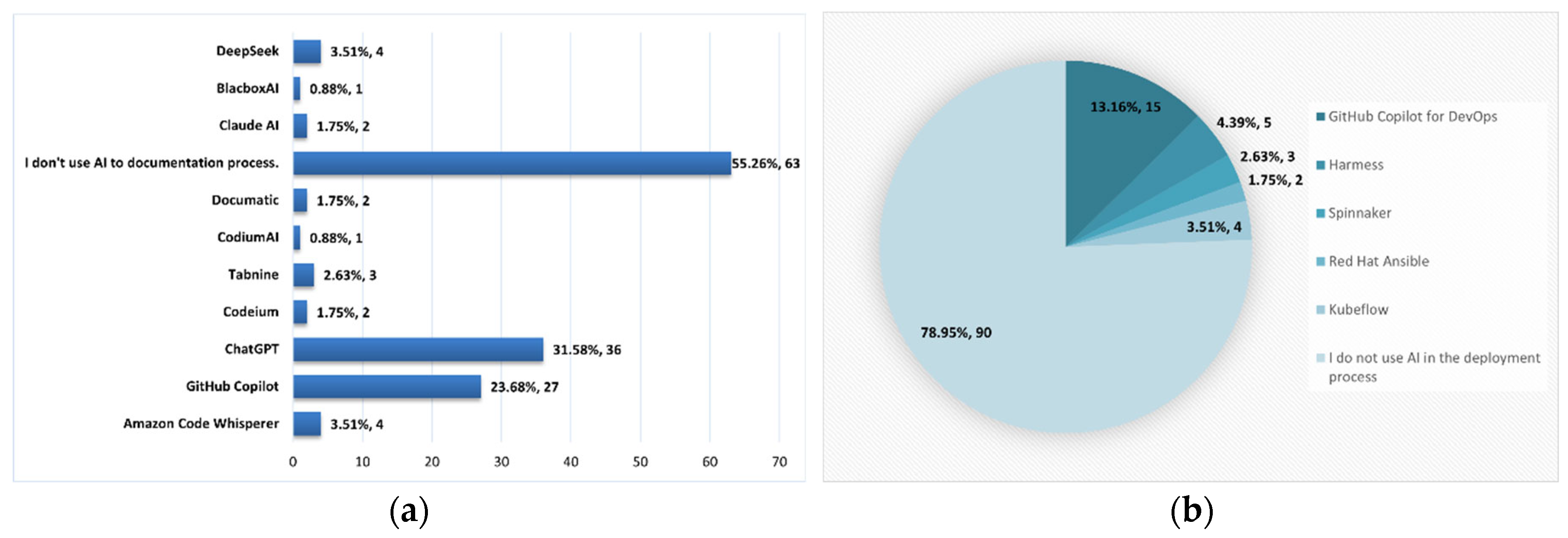

Figure 9 in section (a) shows that for the documentation phase in software development, 55.26 % of respondents don’t use AI tools. On the other hand, 31.58 % indicated to use ChatGPT and 23.68 % use GitHub Copilot.

Section

(b) in

Figure 9 shows that 79.6 % of respondents do not use AI tools during the deployment phase. However, among those who do, 13.16 % have implemented the use of GitHub Copilot for DevOps as a support tool.

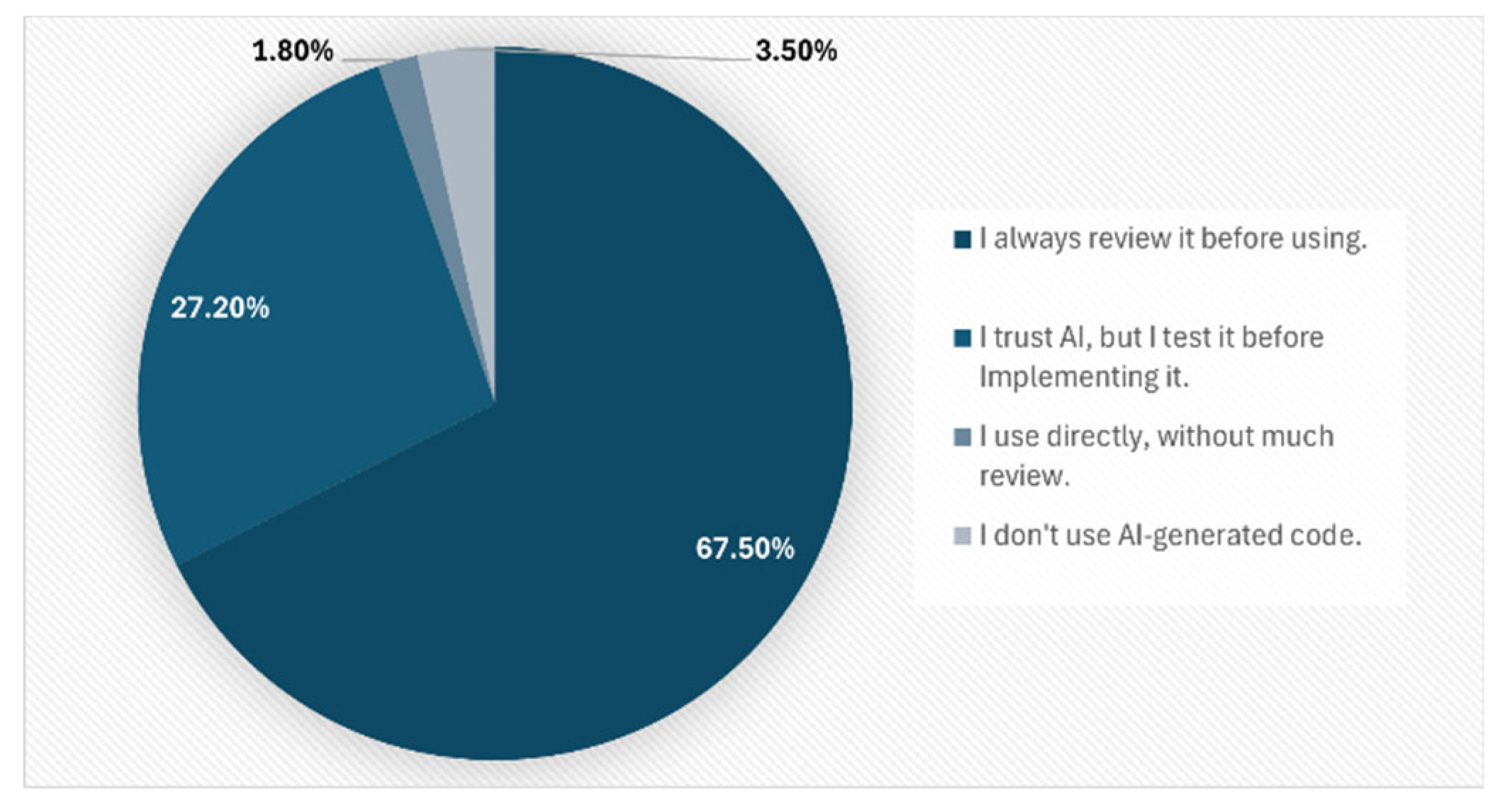

Finally, in

Figure 10 we can observe that regarding AI-generated code requests, 67.5 % of respondents review AI-generated code before using it, while 27.2 % trust the generated code but run tests prior to implementation.

2.2.4. Risk Perception

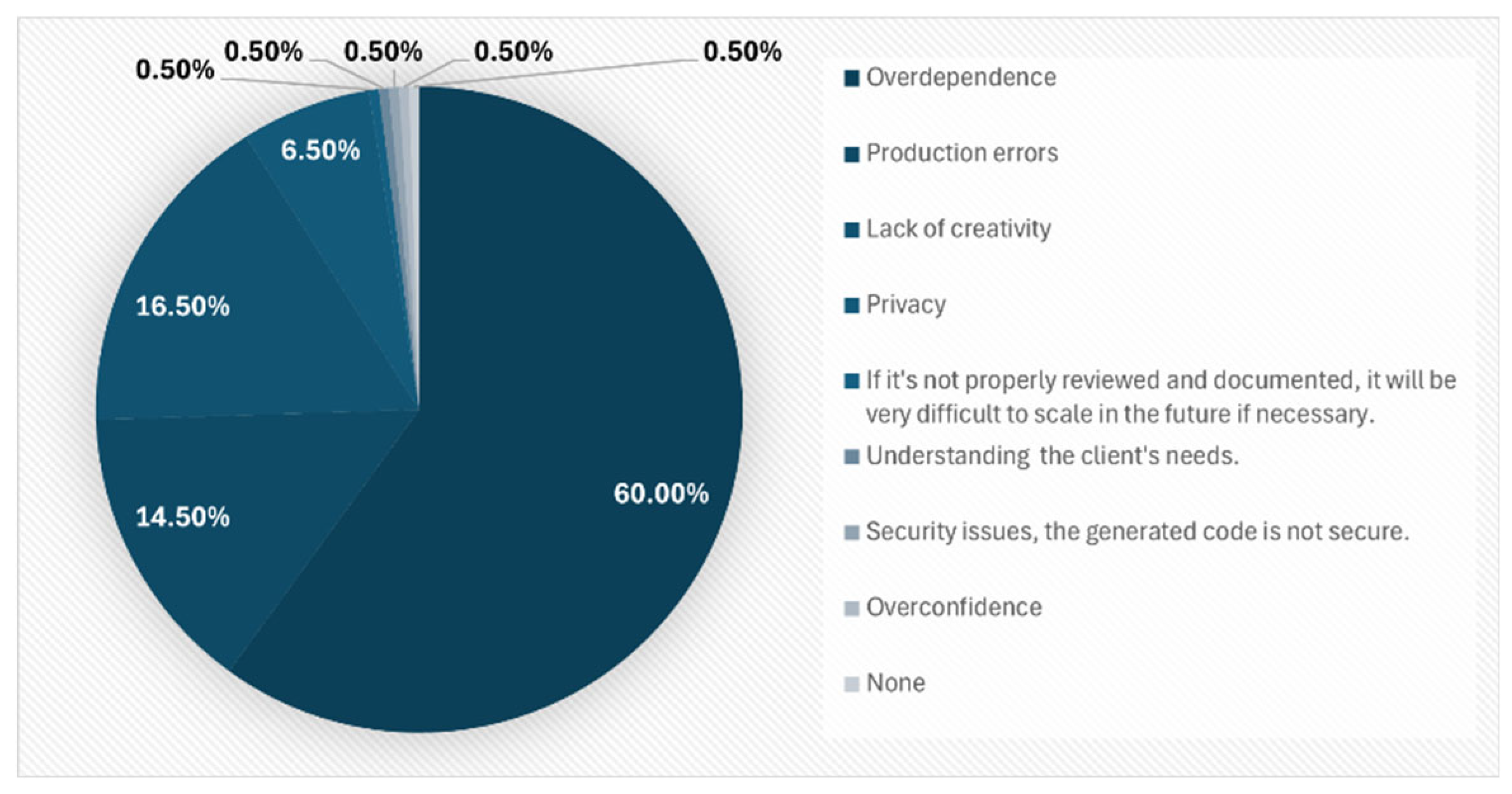

All respondents were asked about the perceived risks of using AI in software development (

Figure 11). The most significant concern (60 %) was the risk of over-dependence on the use of AI. Other mentioned risks included loss of creativity (16.5 %), potential production errors (14.5 %), and privacy issues (5 %).

These results indicate that developers critically reflect on the implications of using AI for software development.

2.2.5. Regulatory Perspective

This section focuses on the ethical implications associated with AI implementation in software development. [

30] It highlights the need for specific ethical considerations in the design, use, and consequences of technologies, particularly in the era of Artificial Intelligence. Data privacy and equitable access are critical issues.

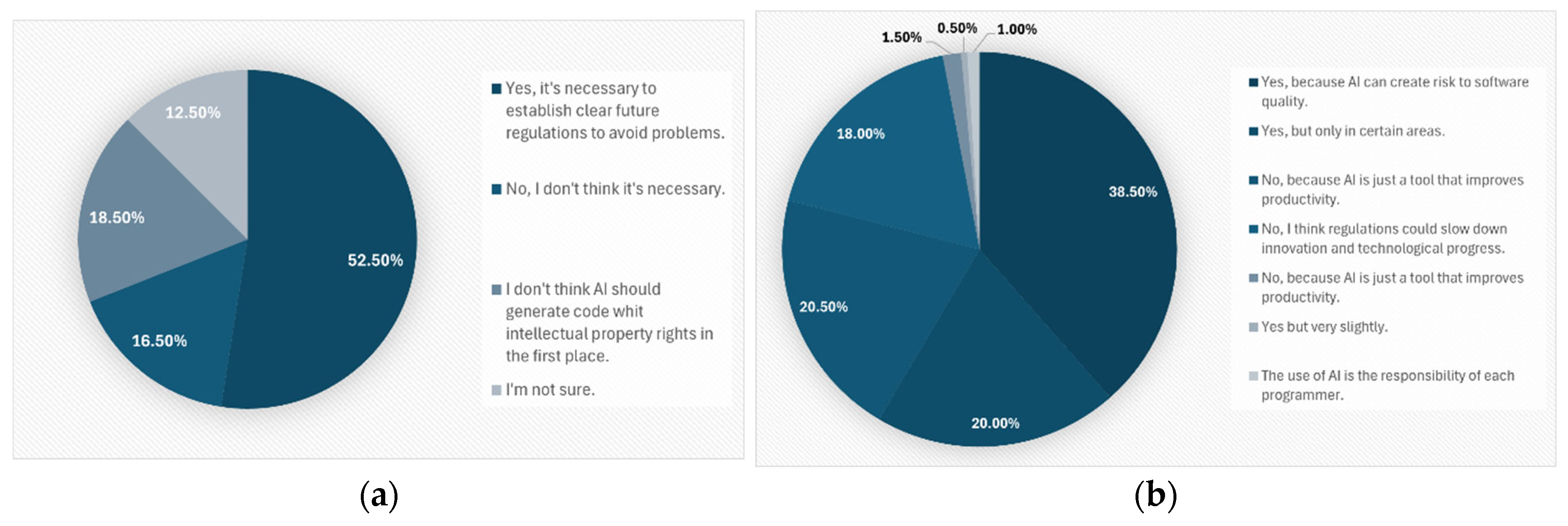

Regarding intellectual property, one question asked respondents whether they believed there should be laws or legislation regulating the ownership of the AI-generated code. More than half of the respondents (52.5 %) agreed that laws or legal definitions should clarify the legal ownership of AI-generated code. Meanwhile, 18.5 % believed that code generated by AI should not have authorship implications, 16.5 % considered copyright regulation unnecessary, and 12.5 % were uncertain about this approach (

Figure 12, section

(a)).

Regarding broader regulations on AI use, 38.5 % of respondents supported AI regulation due to potential risks to software quality, 20 % favored limited regulation, and 20.5 % believe AI tools should be treated like any other development tool (

Figure 12, section

(b)).

The results revealed that the most widely used tool during the development phases included in the data collection artifact was the ChatGPT, particularly in the coding and error detection stages.

However, it’s important to clarify that ChatGPT is not a specialized coding assistant nor a tool created exclusively for development field. ChatGPT is an AI-based language model trained on large volumes of text, including documentation, code, and technical conversations [

31,

32], enabling it to simulate expert interactions in programming and other fields created by OpenAI, which ich also known as generative AI [

33] because of its ability to produce original content.

Since its launch on November 30, 2022, ChatGPT has become the fastest-growing application in history, reaching 100 million active users just two months after its release [

34]. ChatGPT operates using generative pre-trained transformers (GPT), a type of large language model (LLM). It relies on complex Machine Learning algorithms [

35] that compare the user input with its pretrained data. The ChatGPT results were predictions based on the patterns learned the training.

Similarly, the results reflect the need for a regulatory framework for the implementation and use of AI in software development, which takes into account the diverse contexts in which these technologies are adopted.

While a significant portion of respondents supported formal regulation due to potential ethical and software quality risks, it is essential to acknowledge those who advocate for flexible, adaptive, and non-obstructive regulation. Allowing innovation and full exploitation of AI capabilities without unnecessary restrictions.

2.3. Implementation Phase

Based on the findings of this phase, a standardized instrument was designed to optimize the use of AI tools in software development, with a particular focus on the ChatGPT language model.

In the context of AI-assisted software development, the way developers formulate their requests, also known as prompts [

30], is a determining factor for obtaining useful, accurate, and coherent results. Unlike other automated tools, language models such as ChatGPT do not infer user intentions; instead, they interpret the instructions contextually. Consequently, vague, incomplete, or poorly structured prompts may lead to inaccurate or inapplicable responses. By contrast, clear, detailed, and contextualized prompts significantly increase the effectiveness of the language model’s response [

36].

In this regard, a set of recommendations and criteria are presented to improve communication with language models in a standardized artifact, thereby facilitating efficient integration into different stages of software development.

Rather than functioning merely as a documentation format, this tool acts as a strategic asset that helps translate development needs into technically detailed instructions for a language model.

The artifact’s design was based on a user story template [

37,

38], in which the developer explicitly answers a series of key questions:

What am I doing?

What do I need to accomplish with AI?

What attributes or details should the expected solution include?

What environment, technologies, or languages am I using?

What architecture, pattern, or file structure does the solution require?

What exactly should the expected result do?

Table 2.

Generated artifact for the creation of structured prompts.

Table 2.

Generated artifact for the creation of structured prompts.

| ARTIFACT FOR THE PROMPT |

| Artifact ID |

# |

Case Study |

# |

| Author |

Name |

Date |

DD/MM/AAAA |

| General Context |

What am I working on? |

| Phases of SDLC |

Where am I in the development process? |

| Specific Context |

What do I need to perform? |

| Data Source |

Relevant input structure (attributes, variables, data type, etc.). |

| Technology Stack |

Stack of technologies being implemented. |

| Output Format |

Element that I require to generate with the IA according to the development environment used (files, classes, methods, functions, JSON, XML, etc.). |

| Functional Requirement |

Methods to integrate, functions, etc. In this section the user must be very specific as to what is required, explaining in detail what the AI is required to do. |

| Language Model Instruction |

| Concrete and structured formulation of the request to be sent to the linguistic model based on the above attributes, considering a detailed and step-by-step structure for best results. |

This structure made it possible to translate complex needs into understandable, specific, and functional prompts [

5,

39] for the AI in use. Its implementation aims to reduce ambiguity in interactions with AI models while also improving developer productivity and fostering continuous learning when working with intelligent systems. To validate the usefulness of the designed artifact, three real use cases related to common software development tasks were applied.

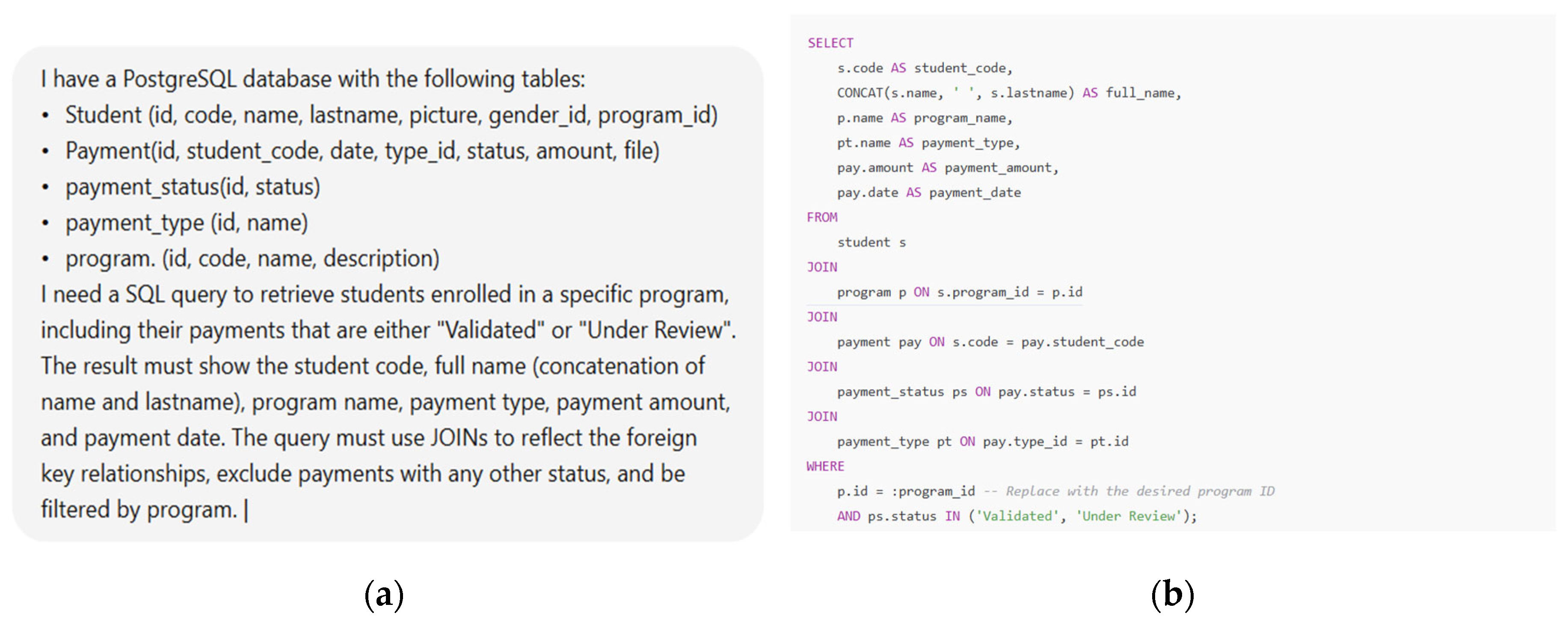

Proof of Concept 1

The first case illustrates how AI can be optimized to generate data queries in a database in PostgreSQL involving specific data from several interrelated tables.This scenario involves an academic system that manages student payments across different educational programs. The objective is to obtain a functional SQL query that retrieves payment information for students, displaying only those payments whose status is "Validated" or "Under Review."

This test aimed to assess the accuracy of the model in handling table relationships, applying conditional filters, and generating an output format aligned with real system requirements.

Table 3.

Artifact for generating SQL queries.

Table 3.

Artifact for generating SQL queries.

| ARTIFACT FOR PROMPT |

| Artifact ID |

001 |

Case Study |

A001 |

| Author |

Juan Pérez |

Date |

06/04/2025 |

| General Context |

I’m developing a database that keeps student payments |

| Phases of SDLC |

Data Base |

| Specific Context |

I need to retrieve students enrolled in a specific academic program, including only payments that are validated or in process. |

| Data Source |

Schema for tables student, payment, payment_status, payment_type and program |

| Technology Stack |

PostgreSQL |

| Output Format |

SQL Query |

| Functional Requirement |

The query must be returned to the student’s code, full name, program name, payment amount and date, only for payments where the status is "validated" or "under reviews". |

| Language Model Instruction |

I have a PostgreSQL database with the following tables:

Student (id, code, name, lastname, picture, gender_id, program_id) Payment (id, student_code, date, type_id, status, amount, file) Payment_status(id, status) Payment_type (id, name) Program (id, code, name, description) I need a SQL query to retrieve students enrolled in a specific program, including their payments that are either "Validated" or "Under Review". The result must show the student code, full name (concatenation of name and lastname), program name, payment type, payment amount, and payment date. The query must use JOINs to reflect the key foreign relationships, exclude payments with any other status, and be filtered by program. |

Proof of Concept 2

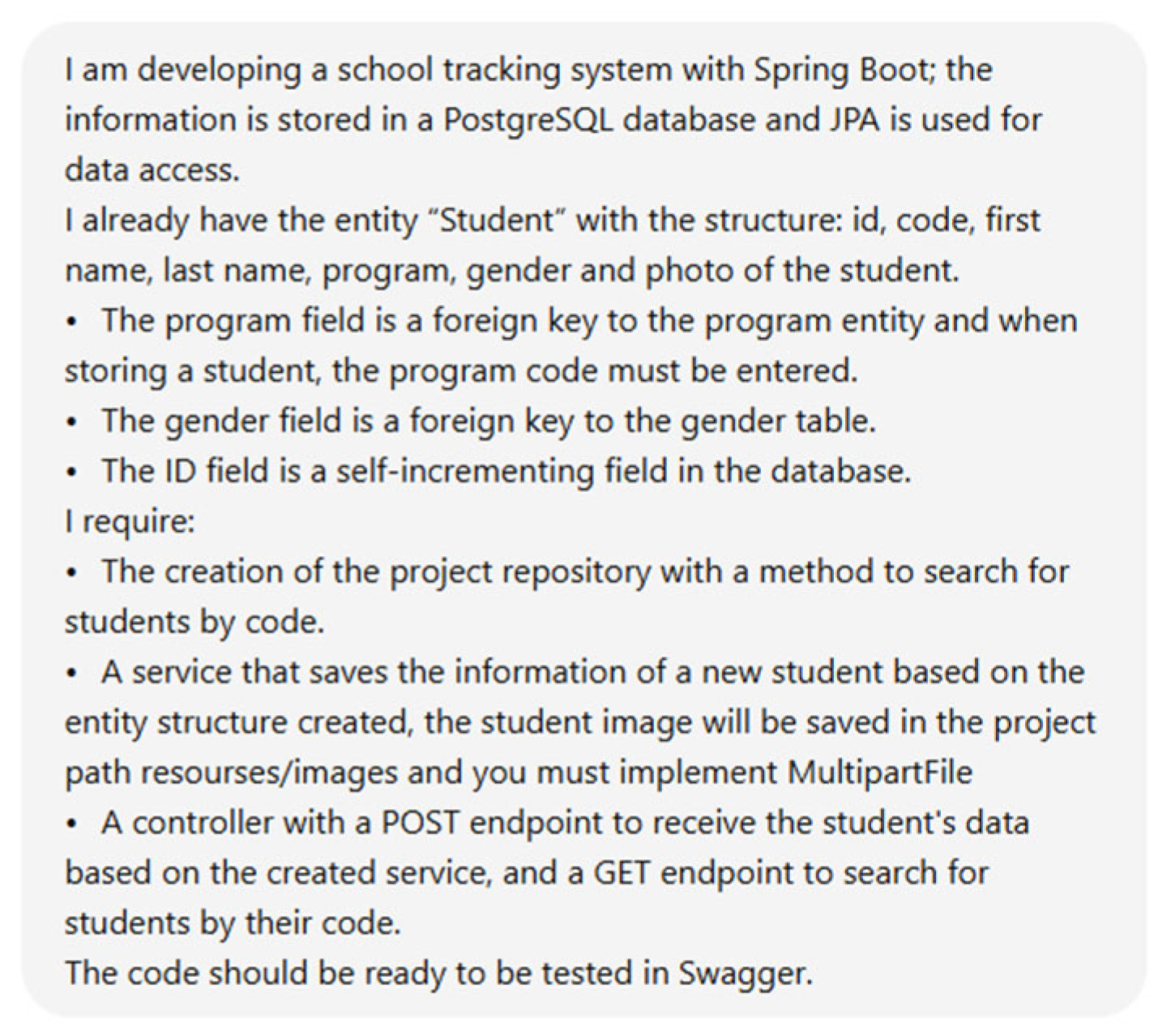

The second functional case was developed for the coding phase, where we sought to solve a common need in backend projects, the registration of a user with file upload in an application developed in SpringBoot.

The general context involved the development of a school tracking system, with data persistence in a PostgreSQL database and access through JPA [

40], where the creation of the necessary code sections to list the registered students and the registration module of a new student following the SpringBoot structure is required. Based on this requirement, the artifact is structured to capture the request in a clear and complete manner, detailing the required structure for each requested file.

Table 4.

Artifact for code generation.

Table 4.

Artifact for code generation.

| ARTIFACT FOR PROMPT |

| Artifact ID |

001 |

Case Study |

A002 |

| Author |

Juan Pérez |

Date |

05/04/2025 |

| General Context |

I am developing a school payment control system with Spring Boot. |

| Phases of SDLC |

Coding / Backend Implementation |

| Specific Context |

I need to implement backend logic to register a new student, save a photo of them, and query students using code. |

| Data Source |

Student Entity whit fields: id, code, first name, last name, program (FK to program Entity, stores program code), gender (FK to gender Entity) and picture saved in resources/images |

| Technology Stack |

Spring Boot as development environment, PostgreSQL as data access technology, JPA and library MultipartFile. |

| Output Format |

Repository, Service and REST Controller classes. |

| Functional Requirement |

Repository with method to find student by code, Service that saves student info and stores uploaded image via MultipartFile, Controller with:

|

| Language Model Instruction |

I am developing a school tracking system with Spring Boot; the information is stored in a PostgreSQL database and JPA is used for data access.

I already have the entity “Student” with the structure: id, code, first name, last name, program, gender and photo of the student.

The program field is a foreign key to the program entity and when storing a student, the program code must be entered. The gender field is a foreign key to the gender table. The ID field is a self-incrementing field in the database. I require:

The creation of the project repository with a method to search for students by code. A service that saves the information of a new student based on the entity structure created, the student image will be saved in the project path resourses/images and you must implement MultipartFile A controller with a POST endpoint to receive the student's data based on the created service, and a GET endpoint to search for students by their code. The code should be ready to be tested in Swagger. |

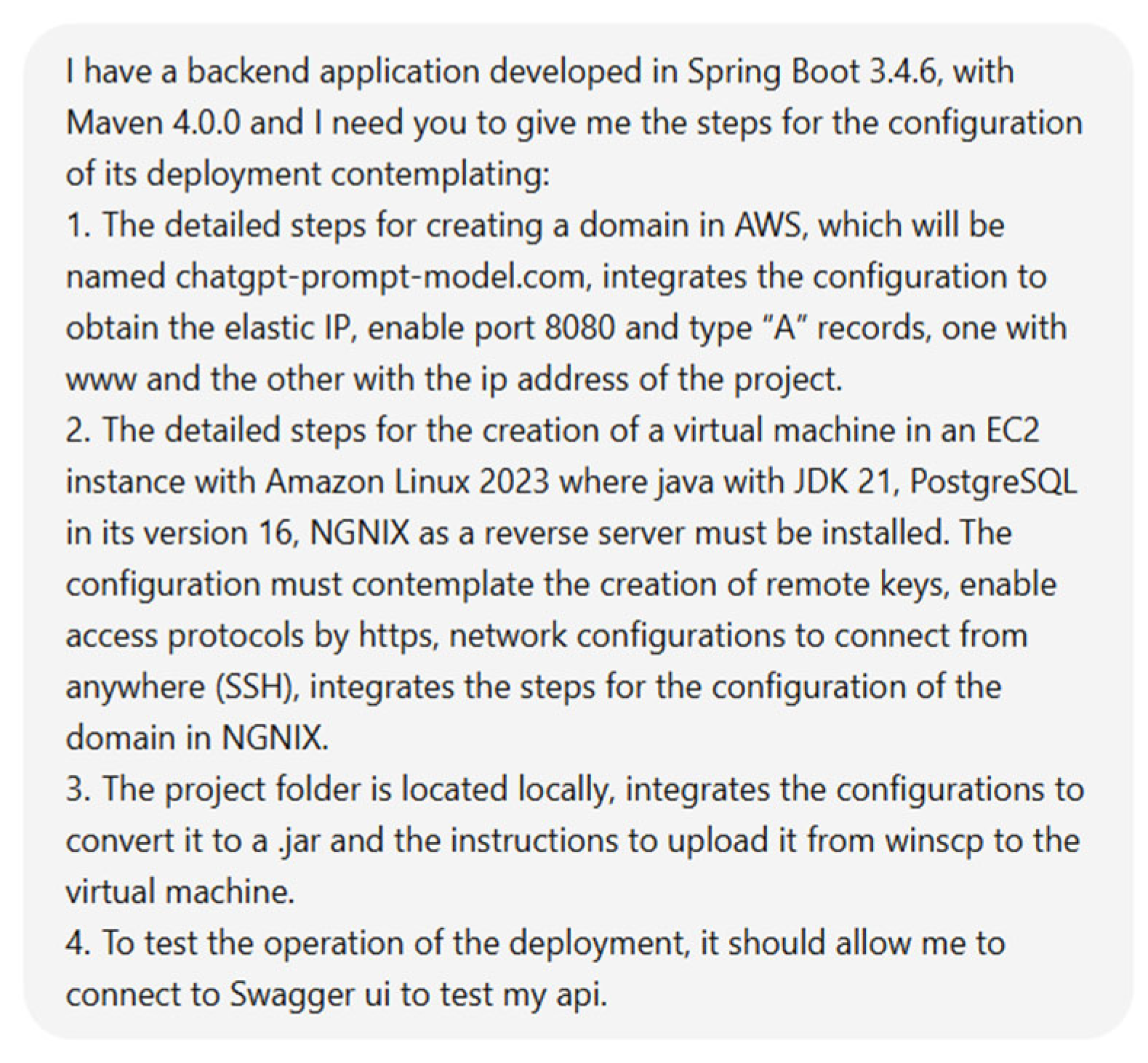

Proof of Concept 3

The third case study focused on evaluating the use of artificial intelligence as a key assistant in the complete configuration and deployment of a backend application developed with SpringBoot on an AWS web server.

This case represents a realistic scenario in which a programmer needs to deploy a project in the cloud, starting from covering everything from domain configuration to production deployment and verification using Swagger.

Table 5.

Artifact for web application deployment.

Table 5.

Artifact for web application deployment.

| ARTIFACT FOR PROMPT |

| Artifact ID |

001 |

Case Study |

A003 |

| Author |

Juan Pérez |

Date |

06/04/2025 |

| General Context |

I have a backend application developed in Spring Boot 3.4.6, with Maven 4.0.0. |

| Phases of SDLC |

Deployment |

| Specific Context |

I need to configure the complete deployment of the application in AWS, from domain configuration to EC2 setup and final Swagger test. |

| Data Source |

The application is a .jar file located in a local folder. Uses PostgreSQL 16 as DB and needs to be deployed behind NGINX in an EC2 instance with Amazon Linux 2023. |

| Technology Stack |

Spring Boot 3.4.6, Maven 4.0.0, Java JDK 21, PostgreSQL 16, AWS EC2, Amazon Linux 2023, NGINX, WinSCP |

| Output Format |

Step-by-step instructions for, AWS domain and DNS configuration, EC2 provisioning, Software installation, Project upload and execution, NGINX reverse proxy Domain linkage and Swagger UI access |

| Functional Requirement |

The system must be deployed successfully and made accessible via a custom domain name (chatgpt-prompt-model.com) through HTTPS and tested via Swagger UI. |

| Language Model Instruction |

I have a backend application developed in Spring Boot 3.4.6, with Maven 4.0.0 and I need you to give me the steps for the configuration of its deployment contemplating:

The detailed steps for creating a domain in AWS, which will be named chatgpt-prompt-model.com, integrates the configuration to obtain the elastic IP, enable port 8080 and type “A” records, one with www and the other with the IP address of the project. The detailed steps for the creation of a virtual machine in an EC2 instance with Amazon Linux 2023 where java with JDK 21, PostgreSQL in its version 16, NGNIX as a reverse server must be installed. The configuration must contemplate the creation of remote keys, enable access protocols by https, network configurations to connect from anywhere (SSH), integrates the steps for the configuration of the domain in NGNIX. The project folder is located locally, integrates the configurations to convert it to a .jar and the instructions to upload it from winscp to the virtual machine. To test the operation of the deployment, it should allow me to connect to Swagger UI to test my API.

|

3. Results

3.1. Genetate Phase

The implementation of the proposed tool provided a comprehensive perspective on the use of artificial intelligence tools, particularly language models such as ChatGPT, within the software development life cycle. Three proofs of concept were developed and executed to evaluate the effective use of artifacts.

Each of these tests focused on a distinct phase of the development process: SQL query generation, backend code implementation, and application deployment in a production environment. The primary objective was to guide users in formulating accurate and complete prompts to optimize the ChatGPT responses in each case. The following sections present a detailed description of each test, including its development, the results obtained, and the technical considerations identified throughout the process.

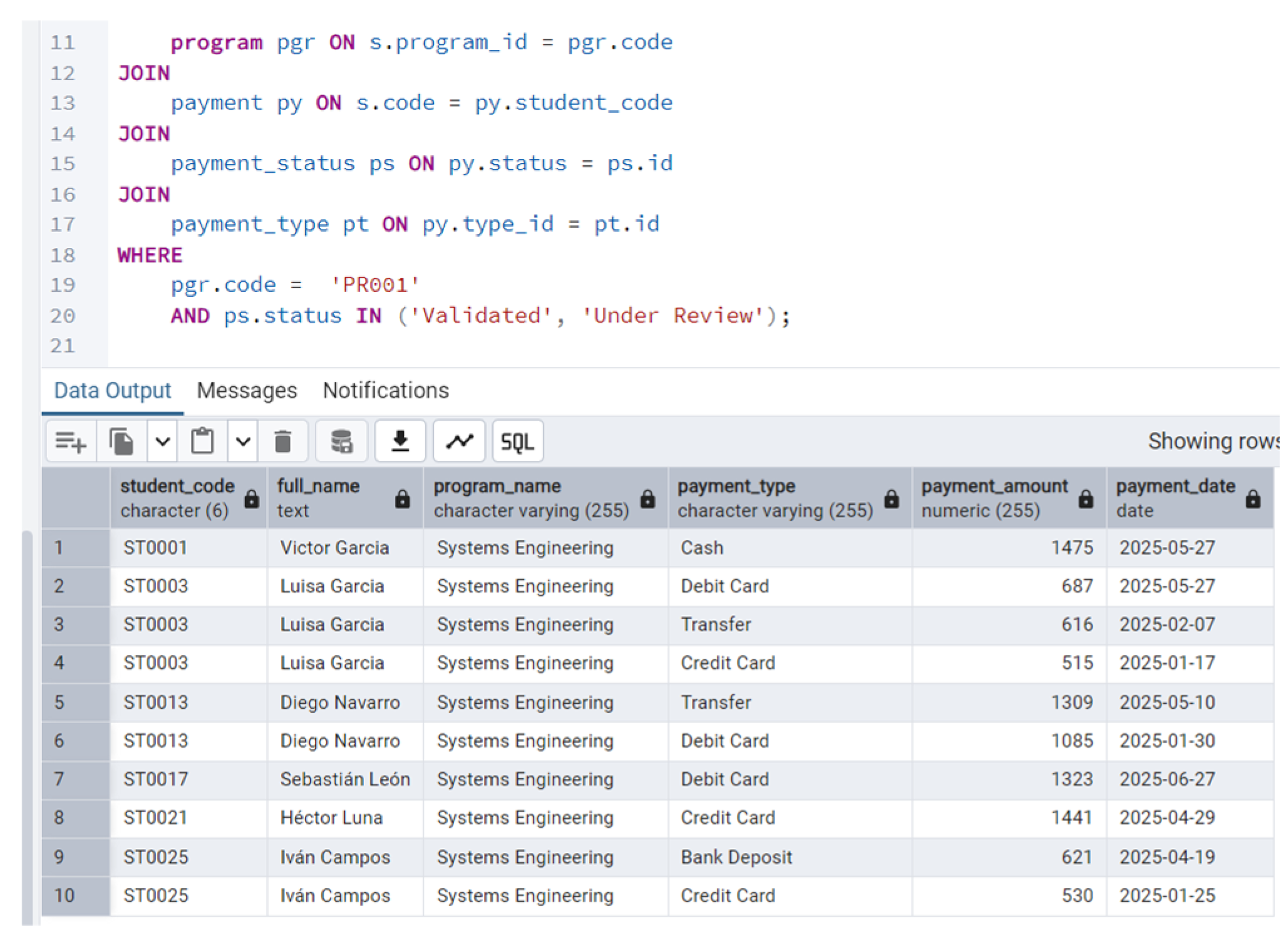

Results of Concept Proof 1

The first proof of concept aimed to evaluate ChatGPT's ability to generate SQL queries based on the functional requirements expressed in natural language. This includes the implementation and validation of the queries generated using the proposed data model (

Table 3).

The proposed scenario involved retrieving information on payments made by students to a school, considering only those with status of “Validated” or “In process.”

The formulated prompt (

Figure 13, section

a) enabled the model to generate a properly structured SQL query, that met the established requirements, respecting the relationship of the tables by implementing JOINS and complying with the specified requirements.

Figure 13 section

b presents the code fragment generated by the model.

The model accurately identified the associations the data model entities and applied filtering criteria to retrieve only transactions corresponding to the specific payment types. Additionally, despite not being explicitly requested, the model concatenated the first and last name fields to construct the student's full name, thereby optimizing the query (

Figure 14).

In terms of syntactic accuracy, logical coherence and clarity of data output, the result is considered satisfactory, demonstrating how a well-structured instruction can fully leverage the capabilities of the AI model in specialized data querying tasks.

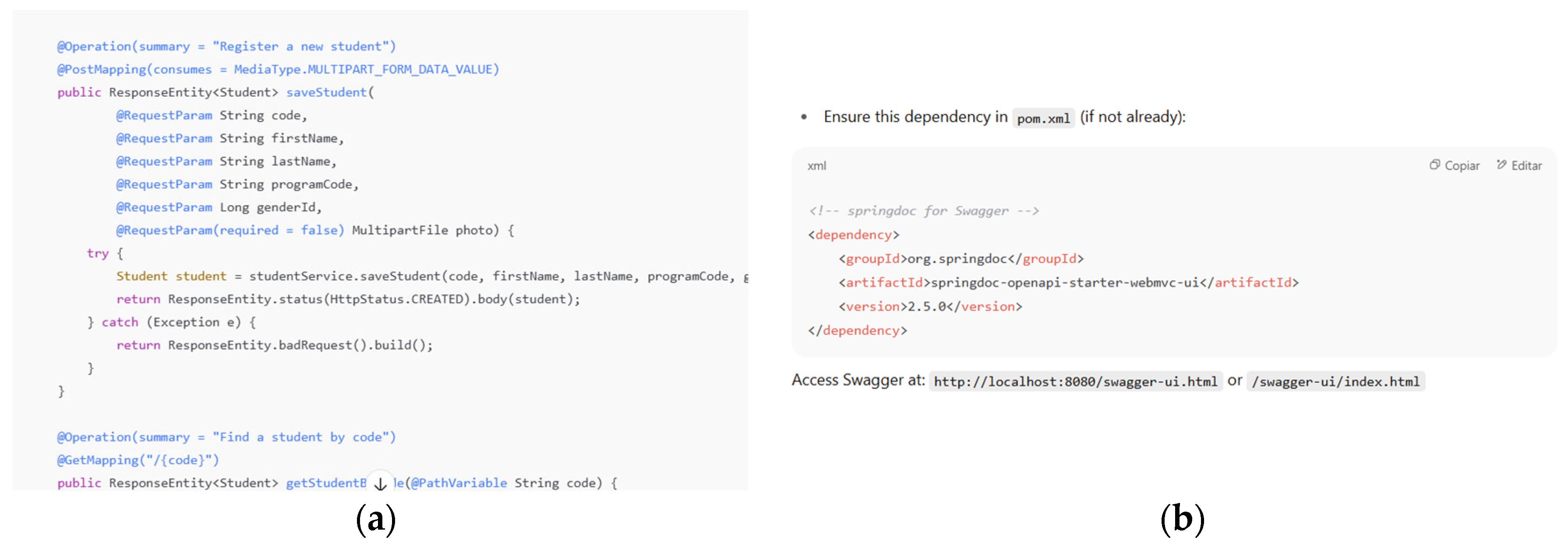

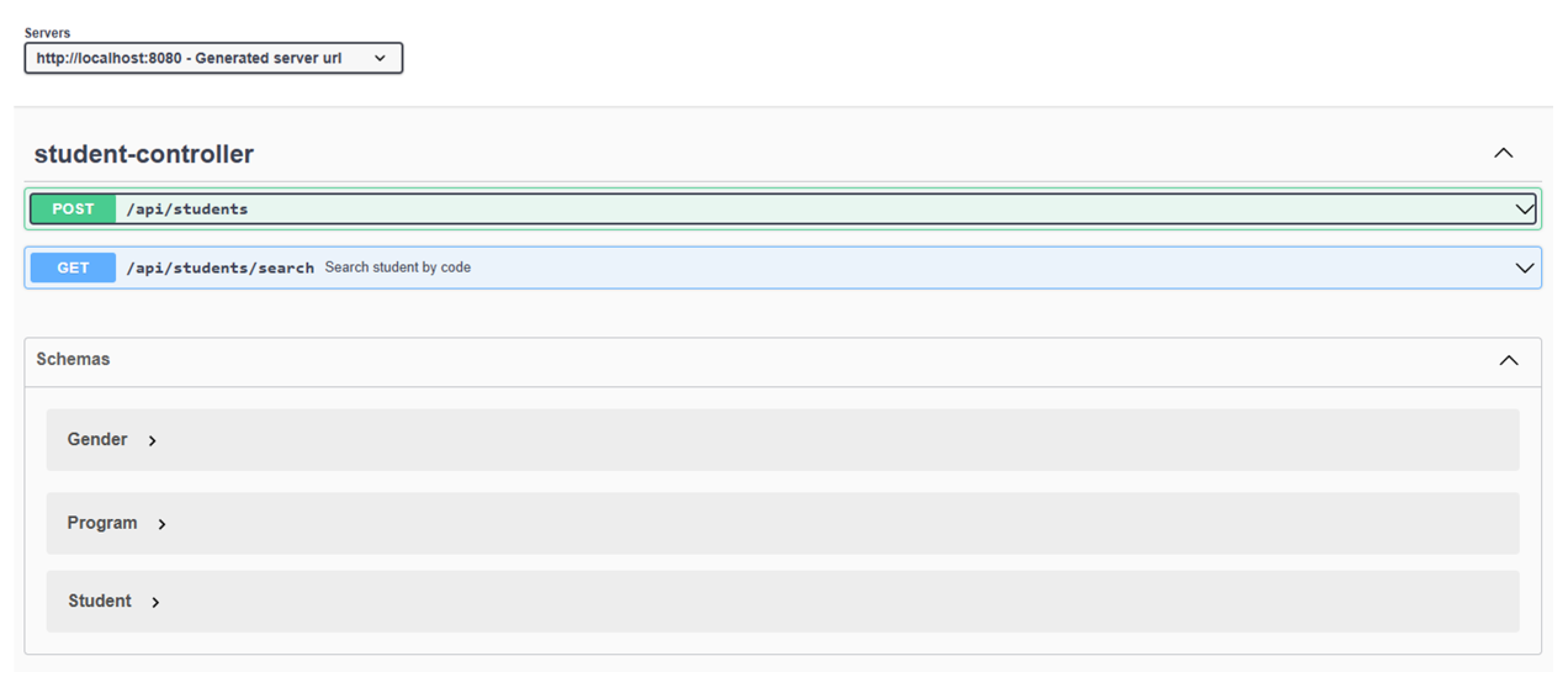

Results of Concept Proof 2

The second proof of concept focuses on evaluating ChatGPT's ability to generate functional backend code, using the Spring Boot framework, adhering to its conventional file structure. The scenario involved developing a module for student registration, which included uploading of a profile image. The required functionality included the implementation of a REST endpoint capable of receiving both the student’s data and an image file, storing the information in a database and saving the file in a local folder, at a specified path.

The clarity of the prompt (Figure 21), designed following best practices, was the key to obtaining an accurate and fully functional response.

Figure 15.

Prompt generated for code phase.

Figure 15.

Prompt generated for code phase.

The generated prompt provided us with the components to generate the Repository, the Service, the Controller, and how to implement Swagger into our project as requested, in a sectioned manner.

The codes can be seen in

Figure 16 and

Figure 17. The generated structure was correct, and the AI understood the structure of the relationships between the tables as provided, so its results were generated with minimal errors.

Similarly, the model shows how to modify the pom.xml file of our SpringBoot project to include the necessary dependency to interact with Swagger.

The request specifies the intention to perform tests using Swagger. For this reason, the model demonstrates how to modify the pom.xml file to include the necessary dependency for interacting with Swagger.

Although the generated code was generally functional (

Figure 18), several important issues were identified during the validation process. For example, the model changed the data type of the gender entity from into long in the structure to save a student, which did not match the original structure of the entity, causing a mapping error. This type of automatic modification is evidence that, although the model can generate robust structures, it is necessary to carefully review the inferences made.

This proof of concept confirms that ChatGPT is a valuable tool for accelerating the development of common backend functionalities, particularly in controlled environments or during the prototyping phase. However, it is always recommended to thoroughly review the generated code, as potential issues such as data typing, variable names, or error handling evidence the need for the developer to maintain an active role during the integration of the generated code.

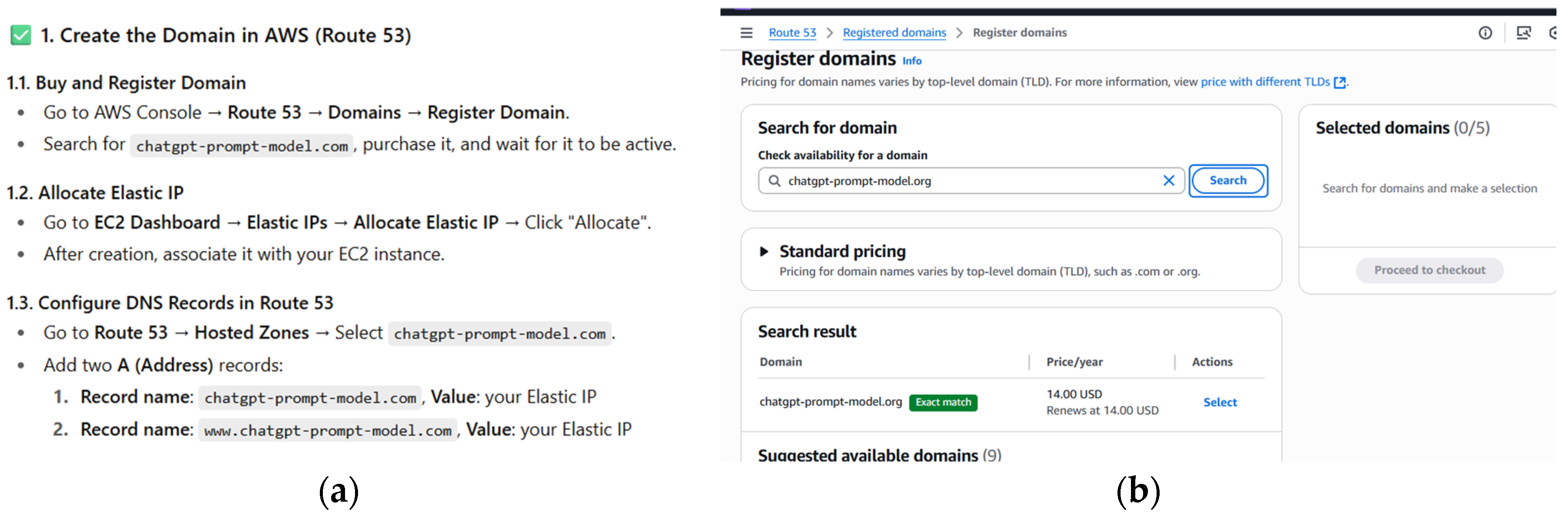

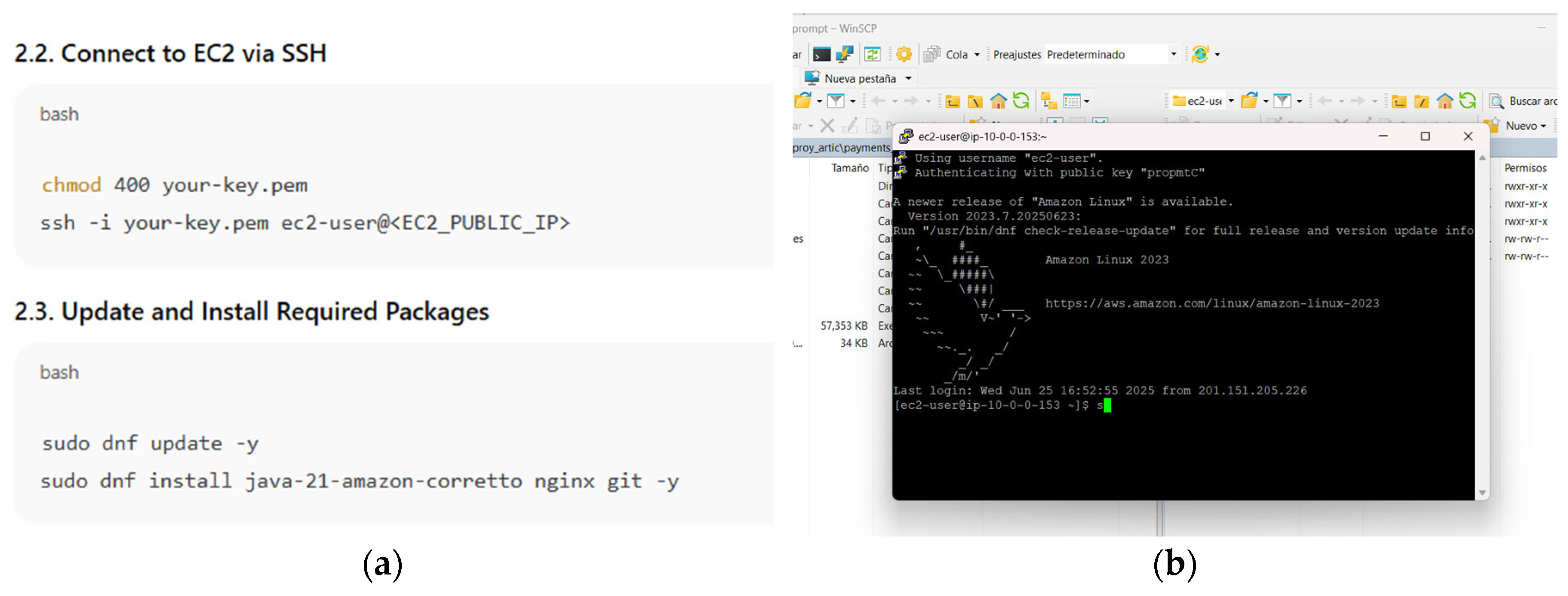

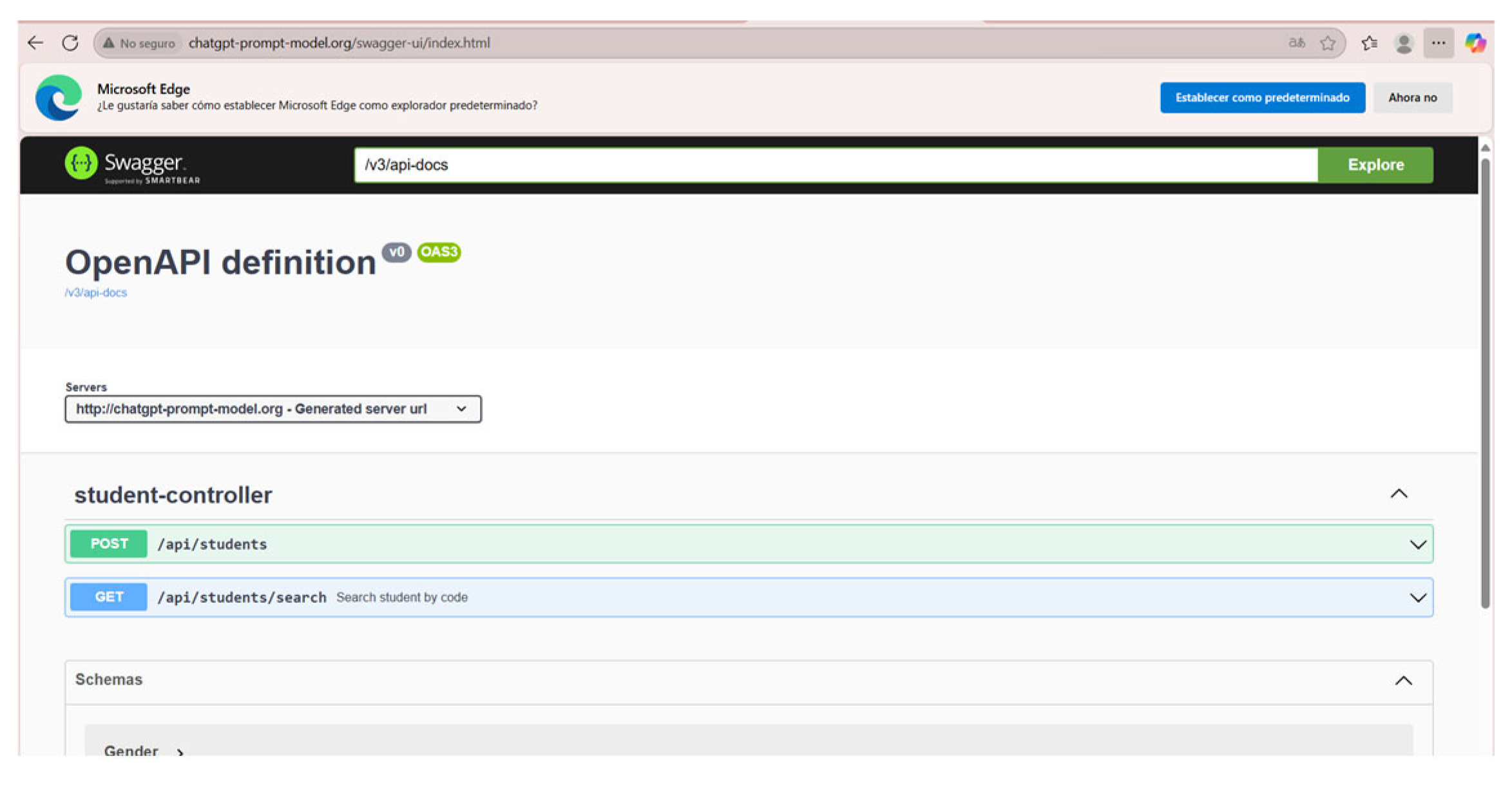

Results of Concept Proof 3

The third proof of concept aimed to assess the effectiveness of ChatGPT in generating accurate and functional instructions to enable the deployment of a backend application developed with Spring Boot on an Amazon EC2 server running Amazon Linux 2023. The objective was to verify whether the model could assist in configuring a production environment from scratch covering tasks such as installing dependencies, configuring services, binding a custom domain, and exposing the system to the network.

The prompt provided (Figure 27) included essential details such as the operating system, the need to use the Spring Boot embedded server (no external container such as Tomcat), and the need to point the custom domain to the server.

Figure 19.

Prompt generated deployment phase.

Figure 19.

Prompt generated deployment phase.

The response generated by the prompt was accurate and followed a clear step-by-step procedure, using updated commands along with security recommendations and best practices independent of the requested points. Part of the generated instructions and results can be seen in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, sections (a) and (b).

The code and commands were successfully tested, enabling the replication of the environment on a real server without critical errors, in the GitHub repository

https://github.com/VaniaMendez/ChatGPTPromptModel you can find the file with the complete results obtained with the prompt and the demo on AWS.

To verify that our backend was deployed correctly, when entering the domain from a web browser, it should display the Swagger testing panel, as shown in

Figure 22.

In conclusion, this proof of concept demonstrated that ChatGPT can serve as a useful knowledge base for application configuration and deployment tasks, offering clear step-by-step guidance that can act as a starting point for developers with intermediate experience. Nevertheless, it is recommended that these instructions be complemented with official documentation, security practices and testing in staging environments before final deployment.

4. Conclusions And Recommendations

This work demonstrates the rapid advancement of language models, such as ChatGPT, in emerging roles within software development tasks, both at the academic level and in professional practice.

Data analysis indicated that approximately 81% of surveyed software developers used the tool in critical stages including coding, logical design, database queries, and technical documentation. ChatGPT is the most widely adopted AI in the current software development landscape. However, 60% of respondents expressed concerns about potential overreliance on AI, and more than 50% highlighted the need for a regulatory framework to accompany the integration of these tools into the software development life cycle, thereby reflecting a collective awareness of their ethical and professional impact.

The graphical analysis of the study variables (

Table 1) revealed that the majority of users were in the 18-23 age group, suggesting a greater openness among younger individuals to adopt these technologies.

Based on these findings, a methodological artifact was developed to guide and facilitate the application of language models throughout the different phases of the software development life cycle. In organizational contexts, this type of resource is often referred to as a knowledge base: it documents and standardizes processes, practices, and lessons learned so that different team members can reuse them. Its use enables the capitalization of tacit knowledge and accelerates procedures, thereby reducing the learning curve for new collaborators.

The artifact was subsequently tested under three real-world scenarios to demonstrate its practical effectiveness:

The first proof of concept focused on generating a multi-table SQL query. ChatGPT produced an accurate and actionable response, proving that it can assist with database tasks, provided that the prompt is well structured and detailed. It allows complex data to be extracted easily, without the need for extensive documentation or manual coding.

The second proof of concept involved generating a backend module for a web application developed with Spring Boot, supporting student registration and image upload. Despite the correct functionality, an error was detected in the data type of the sex field, which changed from int to long. This highlights the persistent margin of error and confirms that developers must carefully review AI-generated code. This case underscores the importance of being specific and clear regarding expected attributes, relationships between tables or variables, and desired behaviors in order to obtain a functional code.

The third proof of concept involved requesting a detailed guide for configuring a custom domain, creating an EC2 instance in Amazon Linux 2023, installing Java 21 and PostgreSQL 16, configure NGINX as a reverse proxy, and enable secure access. It was demonstrated that, if the prompt is not sufficiently specific, ChatGPT may provide vague or unhelpful responses. However, by using the methodological artifact as a reference, it was possible to obtain a detailed and accurate sequence of steps that facilitated the full setup—including the use of WinSCP to upload .jar file and access the Swagger interface. This case highlights that, for infrastructure-related topics, prompt precision is even more critical.

The implementation of this artifact in business environments represents a strategic opportunity to standardize the use of language models in the software development life-cycle. Its structural approach enables development teams to integrate more efficient, systematic, and collaborative processes when interacting with AI tools, reducing common errors in requirement formulation and improving the traceability of technical decisions.

By integrating this artifact into DevOps environments, technical backlogs, documentation processes, or code reviews, companies can not only accelerate productivity but also strengthen the quality and consistency of the generated software, ensuring that the use of artificial intelligence remains transparent, justified, and aligned with their technological objectives.

However, it is important to emphasize that these tools are not recommended for testing tasks, as they present limitations in understanding complex logical contexts, identifying edge cases, or generating reliable automated tests. Therefore, the validation and quality assurance phases should remain the responsibility of developers.

Final Recommendations

Use clear prompts that include technical context and well-defined objectives.

Always validate the results delivered by the model, even for simple tasks.

AI is integrated in phases such as design, coding, and documentation, but not in testing.

We leveraged the benefits of an internal knowledge base built from effective interactions with AI models.

Provide training for development teams on the critical and responsible use of generative tools.

The methodological artifact presented in this work is the first step toward the controlled and effective integration of these models in real-world software development tasks, fostering collaboration between human expertise and intelligent systems within the development workflow.

Finally, it is recommended that the use of ChatGPT and similar models remain a support tool, not a replacement for professional judgment. The most effective way to leverage this technology is to craft detailed, structured, and contextualized prompts, as proposed in the artifact. It is essential to explicitly define what is being done, what is required, what attributes the solution must have, what the technological environment is, and what behavior is expected. These practices not only optimize outcomes but also enable a more ethical, efficient, and professional use of artificial intelligence in the field of software development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Vania Méndez Morales and José Gómez Zea; Data curation, Vania Méndez Morales and Jonathan de la Cruz Álvarez; Formal analysis, José Gómez Zea and Alejandro Hernández Cadena; Funding acquisition, Vania Méndez Morales; Investigation, José Gómez Zea, José Jesús Magaña and Jonathan de la Cruz Álvarez; Methodology, Vania Méndez Morales, José Gómez Zea and José Jesús Magaña; Project administration, Vania Méndez Morales and José Gómez Zea; Resources, José Jesús Magaña, Teresa Javier Baeza and Alejandro Hernández Cadena; Supervision, José Gómez Zea and Alejandro Hernández Cadena; Validation, Vania Méndez Morales, José Gómez Zea, Teresa Javier Baeza and Jonathan de la Cruz Álvarez; Visualization, José Jesús Magaña and Teresa Javier Baeza; Writing – original draft, Vania Méndez Morales; Writing – review & editing, Vania Méndez Morales, José Gómez Zea and José Jesús Magaña.

All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- J. M. Martínez Gómez, M. E. Higuera Marín, Y E. Aguilar Díaz, «Enfoque Metodológico Para El Diseño De Interfaces Durante El Ciclo De Vida De Desarrollo De Software», Gti, Vol. 12, N.º 34, Pp. 59–73, Feb. 2014.

- 2. S, Shylesh, A Study of Software Development Life Cycle Process Models (June 10, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2988291 or http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2988291. [CrossRef]

- P. Maddigan and T. Susnjak, "Chat2VIS: Generating Data Visualizations via Natural Language Using ChatGPT, Codex and GPT-3 Large Language Models," in IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 45181-45193, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Luo, N. Tang, G. Li, J. Tang, C. Chai and X. Qin, "Natural Language to Visualization by Neural Machine Translation," in IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 217-226, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Morales Chan, M. A. (24 de 02 de 2023). Explorando el potencial de Chat GPT: Una clasificación de Prompts efectivos para la enseñanza. http://odoo014.soltecn.com/tesario/handle/123456789/1348.

- Rouhiainen, L. (2018). Inteligencia Artificial, 101 Cosas Que Debes Saber Hoy Sobre Nuestro Futuro. España, España: Editorial Planeta. doi:978-84-17568-08-5.

- H. Abbass, "Editorial: What is Artificial Intelligence?," in IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 94-95, April 2021. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S., Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5, 115–133 (1943). Published: Dicember 1943. [CrossRef]

- Mind, Volume LIX, Issue 236, October 1950, Pages 433–460, Published: 01 October 1950. [CrossRef]

- Radanliev, P. (2024). Artificial intelligence: reflecting on the past and looking towards the next paradigm shift. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Academy, L. I. (2024). The Story of ELIZA: The AI That Fooled the World. Recuperado el 25 de 04 de 2025, de London Intercultural Academy: https://liacademy.co.uk/the-story-of-eliza-the-ai-that-fooled-the-world/.

- BM. (s.f.). DEEP BLUE. Obtenido de IBM: https://www.ibm.com/history/deep-blue.

- Arachchige ASPM. The blue brain project: pioneering the frontier of brain simulation. AIMS Neurosci. 2023 Nov 2;10(4):315-318. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aliaga Gálvez, G. H., & Aznaran Abarca, J. A. (2019). APLICACIÓN MÓVIL PARA DIAGNOSTICAR POSIBLES FALLAS AUTOMOTRICES UTILIZANDO LA HERRAMIENTA IBM WATSON PARA LA EMPRESA VECARS & TRUCKS S.A.C. . Obtenido de UNIVERSIDAD PRIVADA ANTENOR ORREGO: https://repositorio.upao.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12759/5162.

- Porcelli, A. M. (2021). La inteligencia artificial y la robótica: sus dilemas sociales, éticos y jurídicos. Derecho global. Estudios sobre derecho y justicia, VI(16), 49-105. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Tworek, J., Jun, H., Yuan, Q., De Oliveira Pinto, H. P., Kaplan, J., Edwards, H., Burda, Y., Joseph, N., Brockman, G., Ray, A., Puri, R., Krueger, G., Petrov, M., Khlaaf, H., Sastry, G., Mishkin, P., Chan, B., Gray, S., . . . Zaremba, W. (2021, 7 julio). Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.03374.

- Zhang, B., Liang, P., Zhou, X., Ahmad, A., & Waseem, M. (2023). Practices and Challenges of Using GitHub Copilot: An Empirical Study. Proceedings/Proceedings Of The . . . International Conference On Software Engineering And Knowledge Engineering, 2023, 124-129. [CrossRef]

- Song, D., Zhou, Z., Wang, Z., Huang, Y., Chen, S., Kou, B., ... & Zhang, T. (2023). An empirical study of code generation errors made by large language models. In 7th Annual Symposium on Machine Programming.

- Papers, O. D. (22 de 02 de 2022). OECD Framework for the Classification of AI systems. Recuperado el 02 de 05 de 2025, de https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-framework-for-the-classification-of-ai-systems_cb6d9eca-en.html.

- Villasís-Keever, M. Á., & Miranda-Novales, M. G. (2016). El protocolo de investigación IV: las variables de estudio. Deleted Journal, 63(3), 303-310. [CrossRef]

- Oyola-García, Alfredo Enrique. (2021). La variable. Revista del Cuerpo Médico Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo, 14(1), 90-93. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Mendoza, S., & Duana Avila, D. (2020). Técnicas e instrumentos de recolección de datos. Boletín Científico De Las Ciencias Económico Administrativas Del ICEA, 9(17), 51–53. [CrossRef]

- Hamed Taherdoost. Data Collection Methods and Tools for Research; A Step-by-Step Guide to Choose Data Collection Technique for Academic and Business Research Projects. International Journal of Academic Research in Management (IJARM), 2021, 10 (1), pp.10-38. ⟨hal-03741847⟩.

- A. Borgobello, M. P. Pierella, and M.-I. Pozzo, “Ús de qüestionaris en recerca sobre la universitat: anàlisi d’experiències amb una perspectiva situada”, REIRE, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 1–16, Jul. 2019.

- Tom Kwiatkowski, Jennimaria Palomaki, Olivia Redfield, Michael Collins, Ankur Parikh, Chris Alberti, Danielle Epstein, Illia Polosukhin, Jacob Devlin, Kenton Lee, Kristina Toutanova, Llion Jones, Matthew Kelcey, Ming-Wei Chang, Andrew M. Dai, Jakob Uszkoreit, Quoc Le, Slav Petrov; Natural Questions: A Benchmark for Question Answering Research. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2019; 7 453–466. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Murat, P. (2020). Analysis of Multiple-choice versus Open-ended Questions in Language Tests According to Different Cognitive Domain Levels. Novitas - Journal Research on Youth and Language, 14(2), 76-96.

- Fullstory. (03 de December de 2021). What is quantitative data? How to collect, understand, and analyze it. Obtenido de Fullstory BLOG: https://www.fullstory.com/blog/quantitative-data.

- Leyva López, Hermelinda Patricia, Pérez Vera, Monserrat Gabriela, & Pérez Vera, Sandra Mercedes. (2018). Google Forms en la evaluación diagnóstica como apoyo en las actividades docentes. Caso con estudiantes de la Licenciatura en Turismo. RIDE. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 9(17), 84-111. [CrossRef]

- Pillajo Sotalín, Adriana Jovita (2019) Guía Digital Del Uso Del Formulario De Google Forms Para La Evaluación En Básica Superior Quito Uisrael, Maestría En Educación Mención: Gestión Del Aprendizaje Por Tic Quito: Universidad Israel 2019, 127p. PhD. PhD. RENÉ CORTIJO UISRAEL-EC-MASTER-EDU-378-242-2019-012.

- Mora Naranjo, B. M., Aroca Izurieta, C. E., Tiban Leica, L. R., ánchez Morrillo, C. F., & Jiménez Salazar, A. (2023). Ética y Responsabilidad en la Implementación de la Inteligencia Artificial en la Educación. Ciencia Latina. Revista Multidisciplinar, 7(6), 2054 - 2076. [CrossRef]

- Islam Sakib, M. S. (February de 2023). What is ChatGPT? Obtenido de researchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367794587_What_is_ChatGPT.

- Ortiz, P., & Ortiz, P. (2025, 22 mayo). Chat GPT: qué es, para qué sirve y su aplicación en la economía [explicado por Chat GPT]. EDEM Escuela de Empresarios. https://edem.eu/chat-gpt-que-es-para-que-sirve-y-su-aplicacion-en-la-economia-explicado-por-chat-gpt/.

- M. E. Chávez Solís, E. Labrada Martínez, E. Carbajal Degante, E. Pineda Godoy, y Y. Alatristre Martínez, «Inteligencia artificial generativa para fortalecer la educación superior: Generative artificial intelligence to boost higher education», LATAM, vol. 4, n.º 3, pp. 767–784, sep. 2023.

- Belcic, I., & Stryker, C. (2025, 22 mayo). ChatGPT. IBM. https://www.ibm.com/mx-es/think/topics/chatgpt.

- Owusu, P., Raef, A., & Sharaf, E. (2025). Carbonate Seismic Facies Analysis in Reservoir Characterization: A Machine Learning Approach with Integration of Reservoir Mineralogy and Porosity. Geosciences, 15(7), 257. [CrossRef]

- Barney, N. (26 de August de 2024). What is language modeling? Obtenido de TechTarget: https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/language-modeling.

- [36] Menzinsky, A. L., Palacio, J., & Sobrino, M. A. (Agosto de 2022). Historias de Usuario, Ingeniería de Requisitos Ágil. (S. Manager, Ed.) Recuperado el 25 de 04 de 2025, de SafeCreative: https://www.safecreative.org/work/2009135322450?0.

- J. M. Gómez-Zea, J. Ángel Jesús-Magaña, J. de la Cruz-Alvarez, E. Morales-Romero, y E. Sosa-Silva, «Optimización de la documentación en proyectos de software ágiles: Buenas prácticas y artefactos en el marco de trabajo SCRUM», ProgMat, vol. 15, n.º 3, pp. 51–64, nov. 2023.

- K. K. Ruiz Mendoza, «El uso de ChatGPT 4.0 para la elaboración de exámenes: crear el prompt adecuado: The Use of ChatGPT 4.0 for Test Development: Creating the Right Prompt », LATAM, vol. 4, n.º 2, pp. 6142–6157, ago. 2023.

- Bonteanu, A.M.; Tudose, C. Performance Analysis and Improvement for CRUD Operations in Relational Databases from Java Programs Using JPA, Hibernate, Spring Data JPA. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2743. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Defined stages of the study methodology.

Figure 1.

Defined stages of the study methodology.

Figure 2.

Most well-known stages of software development.

Figure 2.

Most well-known stages of software development.

Figure 3.

Geographical location.

Figure 3.

Geographical location.

Figure 4.

(a) Age range of participants; (b) Sector where the participants are located.

Figure 4.

(a) Age range of participants; (b) Sector where the participants are located.

Figure 5.

Developers' area of expertise.

Figure 5.

Developers' area of expertise.

Figure 6.

(a) Most commonly used tools during database schema generation and design; (b) most used tools in the coding phase.

Figure 6.

(a) Most commonly used tools during database schema generation and design; (b) most used tools in the coding phase.

Figure 7.

Most commonly used tools during the error detection phase.

Figure 7.

Most commonly used tools during the error detection phase.

Figure 8.

(a) Most used tools during the testing phase; (b) Most used tools in interface design.

Figure 8.

(a) Most used tools during the testing phase; (b) Most used tools in interface design.

Figure 9.

(a) Most commonly used tools for project documentation; (b) Most commonly used tools in the deployment phase of a system.

Figure 9.

(a) Most commonly used tools for project documentation; (b) Most commonly used tools in the deployment phase of a system.

Figure 10.

Confidence in the results obtained by AI.

Figure 10.

Confidence in the results obtained by AI.

Figure 11.

Perception of the risk of AI implementation.

Figure 11.

Perception of the risk of AI implementation.

Figure 12.

(a) Consideration of intellectual property laws; (b) Consideration of AI use regulations.

Figure 12.

(a) Consideration of intellectual property laws; (b) Consideration of AI use regulations.

Figure 13.

(a)Prompt generated in ChatGPT; (b) Results obtained from the prompt.

Figure 13.

(a)Prompt generated in ChatGPT; (b) Results obtained from the prompt.

Figure 14.

Implementation of results in PostgreSQL Database.

Figure 14.

Implementation of results in PostgreSQL Database.

Figure 16.

(a) Student Repository archive generated by ChatGPT; (b) Student Service archive generated by ChatGPT.

Figure 16.

(a) Student Repository archive generated by ChatGPT; (b) Student Service archive generated by ChatGPT.

Figure 17.

(a) Student Controller generated by ChatGPT; (b) Swagger Implementation.

Figure 17.

(a) Student Controller generated by ChatGPT; (b) Swagger Implementation.

Figure 18.

Backend testing in Swagger.

Figure 18.

Backend testing in Swagger.

Figure 20.

(a) Steps for configuring the domain in AWS; (b) Step 1.1 Registering the domain name.

Figure 20.

(a) Steps for configuring the domain in AWS; (b) Step 1.1 Registering the domain name.

Figure 21.

(a) Steps for configuring the virtual machine; (b)Virtual machine configuration.

Figure 21.

(a) Steps for configuring the virtual machine; (b)Virtual machine configuration.

Figure 22.

Application deployed and tested in Swagger.

Figure 22.

Application deployed and tested in Swagger.

Table 1.

Description of the study variables applied.

Table 1.

Description of the study variables applied.

| CATEGORY |

VARIABLE |

PURPOSE |

| Participant Profile |

Age Group, Geographical Location, Professional Status, Years of Experience |

Characterize the participants based on their background, experience and context. |

| Technical Specialization |

Area of Development |

Analyze how the area of technical focus relates to the use of AI |

| AI Tools |

Frequency and confidence in AI generated Code |

Understand actual practices and validation of AI-generated code. |

| Risk Perception |

Perceived risks associated with AI use |

Identify key ethical, technical, and professional concerns |

| Regulatory Perspective |

Option on intellectual property legislation |

Assess the perceived need for legal frameworks and regulatory guidelines. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).