1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization [

1], more than 1 billion people live in areas of active leishmaniasis transmission. Clinically, human infections may present distinct forms of the disease. Cutaneous clinical forms are highly prevalent worldwide. At the same time, visceral leishmaniasis (VL), although more limited, may be fatal [

2], and the urbanization of the transmission may lead to the expansion of the infection in densely populated centers [

3,

4]. Visceral Leishmaniasis in Brazil is due to

Leishmania infantum infection, vectorized by the Phlebotomine (Diptera:

Psychodidae) species

Lutzomyia longipalpis [

5,

6]. Climate changes and active deforestation may increase the risk of transmission of VL [

7,

8]. Domestic dogs are the main reservoirs of VL, although the role of cats in the transmission is unclear [

9]. Brazil contributed to 93% of VL human cases in South America over the past five years, with a mortality rate of 8,2% [

10].

Sand flies transmit distinct pathogens besides

Leishmania, including viruses belonging to species of the Class Bunyaviricetes (International Committee of Taxonomy of Virology, 2025), mainly comprised by the Genus Phlebovirus (Phenuiviridae)[

11], which are major human and veterinary Public Health problems worldwide [

12,

13,

14]. Sand fly-transmitted Bunyavirecetes generally present three genomic segments: Large (L), Medium (M), and Small (S), and the average total genomic size is around 12kb. Segment L codes for the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), the most conserved sequence shared by most members belonging to the Class Bunyavirecetes [

15]. The reassortment of genomic segments may generate a high diversity of Pheboviruses and other segmented RNA viruses [

16].

The co-circulation of Phleboviruses (Phenuiviridae) and

Leishmania in sand flies across several geographical areas and the recent finding of dogs as potential reservoirs of Toscana virus and

L. infantum may indicate a possible epidemiological correlation between phleboviruses and Leishmaniasis [

17,

18,

19,

20].

We developed an RT-PCR-based assay to investigate the occurrence of Bunyaviricetes coinfection in dogs with VL from a transmission area in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In the present paper, we discuss our findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primer Design and Tree Inference

All Segment L sequences were obtained from the NCBI GenBank (

https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore). We selected only sequences of Bunyaviricetes from the Americas that have been isolated in sandflies or are closely related to Bunyaviricetes described in sand flies(

Table 1). All selected sequences were aligned using MEGA12 by the ClustalW algorithm, and conserved regions were selected for primer design. With the aligned sequences, we used TrimAL[

21] to trim regions with gaps using the “gappy” function, followed by tree inference in Iqtree[

22] using a maximum likelihood method with a GTR+G+I model with a bootstrap value of 1000[

23]. The consensus tree was visualized using FigTree (

http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Alignment of the L segment from the isolate and the Pacui from the NCBI database was visualized using Jalview[

24]

Table 1.

List of RNA polymerase sequences of bunyaviricetes used in the phylogenetic tree. All 29 virus sequences used in the tree are listed with their source, locality, and NCBI accession number. Only viruses found in South and Central America are listed.

Table 1.

List of RNA polymerase sequences of bunyaviricetes used in the phylogenetic tree. All 29 virus sequences used in the tree are listed with their source, locality, and NCBI accession number. Only viruses found in South and Central America are listed.

| Name |

Source |

Locality |

Accession number |

| Salobo Virus |

Proechimys guyannensis |

Para, Brazil |

NC_078045 |

| Icoaraci Virus |

Nectomys species |

Belem, Para,Brazil |

NC_055420.1 |

| Joa Virus |

Lutzomyia species |

Altamira, Para, Brazil |

KX611391 |

| Frijoles Virus |

Lutzomyia species |

Panama |

MK330765 |

| Viola Virus |

Lutzomyia sp |

Mato-Grosso,Brazil |

NC_055437 |

| Rio Claro Virus |

Mesocricetus auratus |

Venezuela |

NC_078053 |

| Campana Virus |

Sand fly |

Panama |

NC_078074 |

| Buenaventura virus |

Sand fly |

Valle del Cauca,Colombia |

NC_055389 |

| Capira Virus |

Sand fly |

Panama |

KP272043 |

| Echarte Virus |

Homo sapiens |

Peru |

NC_055339 |

| Maldonado Virus |

Homo sapiens |

Peru |

NC_055344 |

| Ariquemes Virus |

Lutzomyia sp |

Brazil |

HM119404 |

| Itaituba Virus |

Didelphis marsupialis |

Para, Brazil |

NC_055307 |

| Chandiru Virus |

Homo Sapiens |

Belem, Para,Brazil |

HM119407 |

| Morumbi Virus |

Homo Sapiens |

Tucurui, Para, Brazil |

HM119422 |

| Pacui Virus |

Oryzomys sp |

Para, Brazil |

NC_043600 |

| Chilibre Virus |

Lutzomyia sp |

Panama |

NC_077870 |

| Rio Preto da Eva virus |

Phlebotominae sp |

Amazonas, Brazil |

NC_043605 |

| Caimito Virus |

Nyssomyia ylephiletor |

El Aguacate,Panama |

NC_055409 |

| Tapirape Virus |

Oxymycterus sp |

Para, Brazil |

NC_055618 |

| Nique virus |

Sand fly |

Panama |

NC_055314 |

| Oriximina virus |

Lutzomyia sp. |

Oriximina, Para, Brazil |

NC_055303 |

| Tres Almendras virus |

Psychodopygus panamensis |

Panama |

NC_055402 |

| Punta Toro virus |

Homo sapiens |

Panama |

KR912208 |

| Chagres virus |

Homo sapiens |

Panama |

NC_055327 |

| Leticia virus |

Sand fly |

Leticia, Amazonas, Colombia |

NC_078051 |

| Urucuri virus |

Proechimys guyannensis |

Belem, Para, Brazil |

NC_033841 |

| Cacao virus |

Nyssomyia trapidoi |

El Aguacate, Panama |

NC_055325 |

| Uriurana virus |

phlebotomine sand flies |

Tucuruí, Pará, Brazil |

NC_078057 |

2.2. Bone Marrow and Sera from Dogs:

Clinical samples from dogs Bone marrow and sera were obtained from VL-positive dogs detected and managed by the VL Control Program for Zoonosis Control. The samples originated from Vargem Grande, a district belonging to the city of Rio de Janeiro. Both bone marrow and sera samples were conserved in DNA/RNA Shield™ Reagent, Zymo Research. Samples were sorted by tissue type, cataloged, and stored in -80°C until thawed to be used in RNA extraction.

2.3. Viral Isolation and Cultivation

A positive serum sample from the dog “Nala”, which was previously tested positive for the primer group A, was used. A flask containing the BHK-21 cell line was prepared with 70% confluence of cells. 500ul of the serum and 1.5ml of DMEM(Gibco) were used in the adsorption for 2 hours at 37 °C. The flask was shaken every 20 minutes to facilitate virus distribution among the cell layer. After 2 hours, the supernatant was discarded and the flask was filled with 5ML of DMEM(Gibco)+10% fetal bovine serum(Gibco) +Antibiotic (Gibco). The cell cultures were monitored for 6 days, and no cytopathic effects were observed. After 6 days, the 2ml of the supernatant was passed to a new BHK-21 flask, and the process was repeated for three passages. In the fourth passage, cells were tested by RT-PCR for the presence of the virus and revealed to be positive. Two passages after that cytopathic effect was observed with more cytopathic effect. The viral titration was performed as described in [

25]

2.4. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Bone marrow samples were conserved in DNA/RNA Shield Reagent (ZYMO, US), and total RNA was extracted with the RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN, Ge). RNA from sera samples was isolated using the ReliaPrep™ Viral TNA Miniprep System (PROMEGA, US). The Superscript IV enzyme (Thermo Corporation, US) was synthesized in cDNA.

2.5. RT-PCR Assays

We performed semiquantitative RT-PCR to detect the genome of sand fly-borne viral infections in the bone marrow and sera from VL-infected dogs.. The designed primers were based on the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase sequences and further phylogenetic analysis. The sequences used in this study are in

Table 1. We discriminated between groups A and B and designed primers accordingly. All cDNAs were submitted to RT-PCR assays using both pairs of primers in different reactions. All the sequences are:

A F- 5’- TCCAGAGGAAAAAGCCTGCAT-3’

A R- 5’ TGGGATCCATAACTACAAGCCA-3’

B F- 5’ TATCCAGAGGAAAAGCCTGC-3’

B R- 5’ GGGTCCATAACTACAAGCCA- 3’

The amplification conditions were conducted with an annealing temperature of 55 ºC, an extension of 30 seconds, and 40 amplification cycles. The PCR products were separated in a 1,4% agarose gel.

2.6. PCR Products Sequencing

Positive PCR products were purified using the PureLink quick PCR purification kit(Thermo Fisher) following the guidelines for purification of >300bp PCR products and sequenced using the Sanger method. After sequencing, the products were analyzed using Bioedit to trim the sequences and form contigs. The acquired contigs were then searched using Blast-n.

2.7. RNA Virome Sequencing

Total RNA obtained from serum samples was converted into cDNA by reverse transcription and used for library preparation using the Nextera XT kit, followed by DNA sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq platform. To assemble the viral genome segments, adapter trimming and quality filtering of raw reads were implemented using Trimmomatic v.0.39. The filtered reads were submitted to Bowtie2 v2.4.4 [

26] to run a reference alignment against the Syrian hamster genome (Genbank GCA_017639785.1) and remove contaminating sequences. Unmapped reads were then used for de novo assembly using SPAdes v3.15.4 with default parameters [

27], and complete genome segments were subsequently generated by de novo assembling of SPAdes contigs using Geneious assembler at medium sensitivity implemented in Geneious Prime v2024.0.1. The genomic coverages for S, M, and L segments were 638x, 765x, and 486 x, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. The Multiple Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree of the L Segment of Latin American Sand fly-Borne Bunyavirecetes

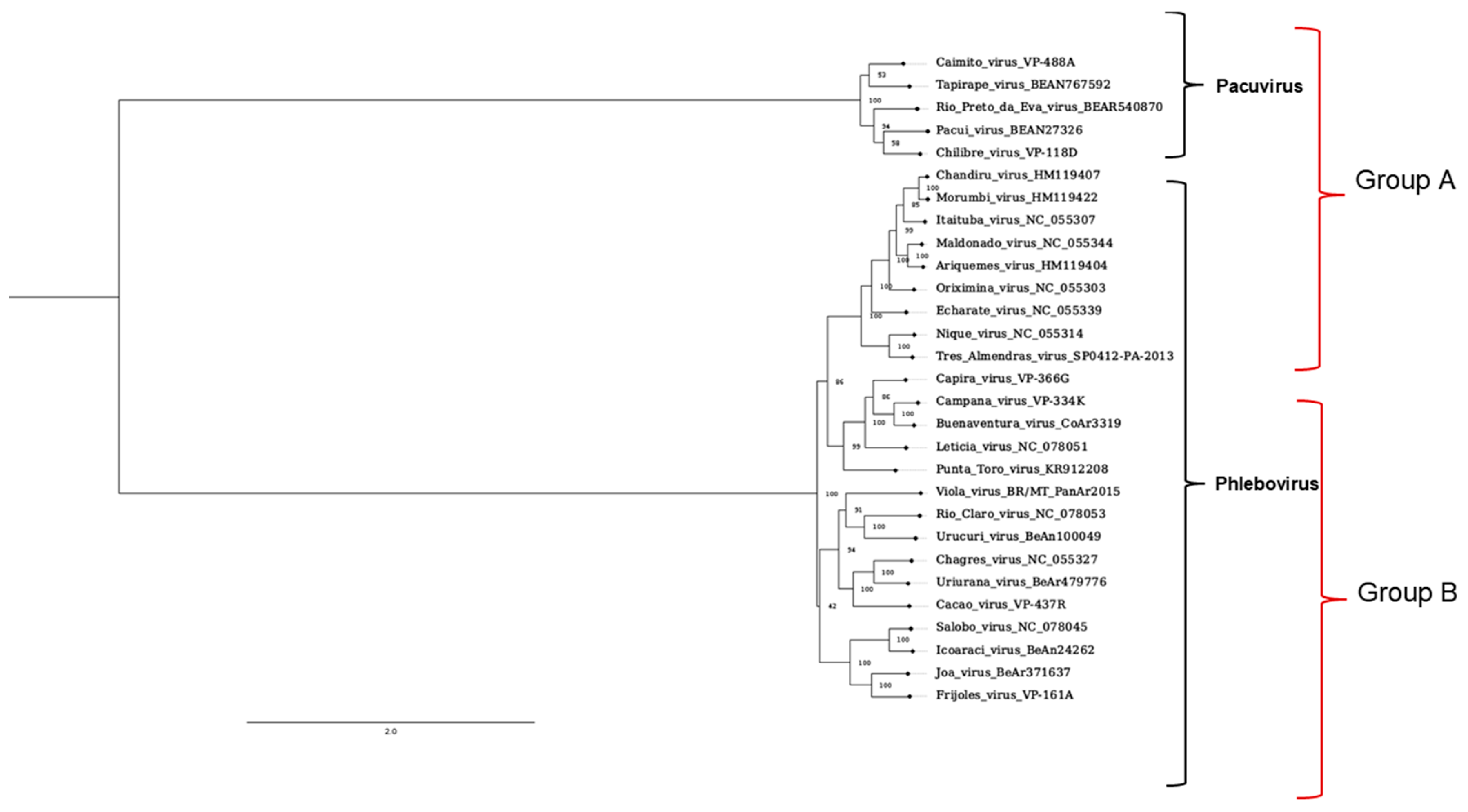

The DNA sequences of Latin-American sand fly-borne Bunyavirecetes were retrieved, and a phylogenetic tree analysis was performed. We observed a conspicuous segregation into two main groups called A and B. Most of the Phlebovirus species were gathered in group B, while the ex-Phlebovirus species, the Pacui group, was found in Group A.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the L segment of phlebotomine-related Bunyaviricetes and primer groups. The tree shows different families inside the Bunyaviricetes Class. All viruses from the Pacuivirus and Phlebovirus families are found on the American continent. The marks on the right side indicate the sequences predicted to be amplified by A or B primers in PCR reactions.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the L segment of phlebotomine-related Bunyaviricetes and primer groups. The tree shows different families inside the Bunyaviricetes Class. All viruses from the Pacuivirus and Phlebovirus families are found on the American continent. The marks on the right side indicate the sequences predicted to be amplified by A or B primers in PCR reactions.

3.2. RT-PCR Assays Distinguish Species of Group A and B

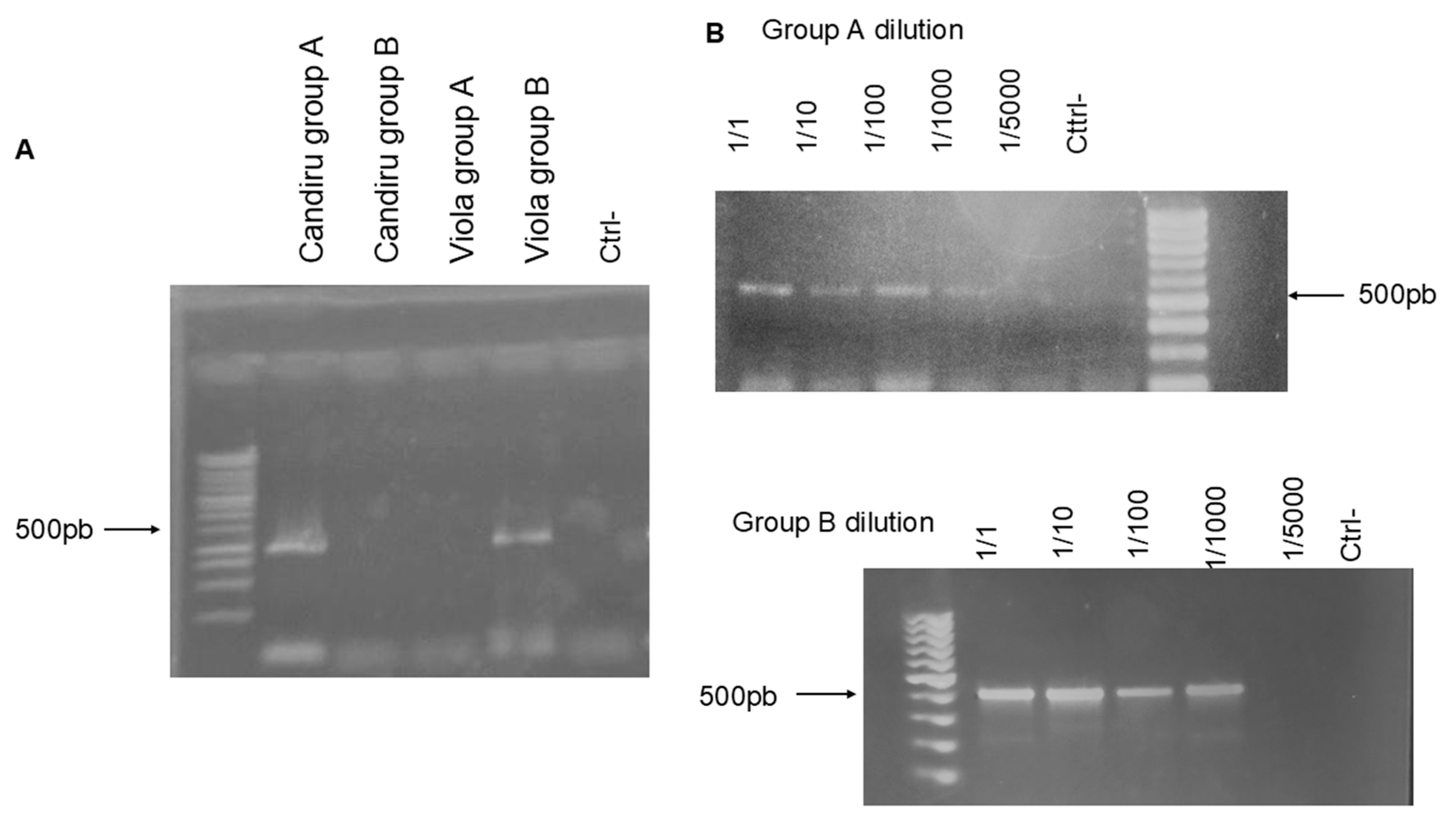

Based on the predicted discrimination of the Bunyaviricetes species displayed in the phylogenetic analysis, we decided to test the specificity of Primers A and B.

Figure 2A shows that the cDNA of a representative of Group A, Chandiru A virus, is amplified explicitly by the set of Primer A, while Primers B only reacted with the cDNA derived of Viola virus, a Phlebovirus from the B group. The serial dilution and amplification of the Chandiru virus (2B) cDNA and Viola virus (2C) showed a positive amplification detection until 1/1000 cDNA dilution.

Figure 2.

Primer specificity testing and cDNA serial dilution tests. A 1,4% agarose gel with PCR products of 2 different viruses, Chandiru virus for the predicted group A and Viola virus for group B, was tested on both A and B primer groups. (A)The gel shows the specificity of the primers being able to detect only viruses from the defined groups ; (B) shows the dilution of the cDNA used in the RT-PCR reaction and the capacity of detection of the primer set.

Figure 2.

Primer specificity testing and cDNA serial dilution tests. A 1,4% agarose gel with PCR products of 2 different viruses, Chandiru virus for the predicted group A and Viola virus for group B, was tested on both A and B primer groups. (A)The gel shows the specificity of the primers being able to detect only viruses from the defined groups ; (B) shows the dilution of the cDNA used in the RT-PCR reaction and the capacity of detection of the primer set.

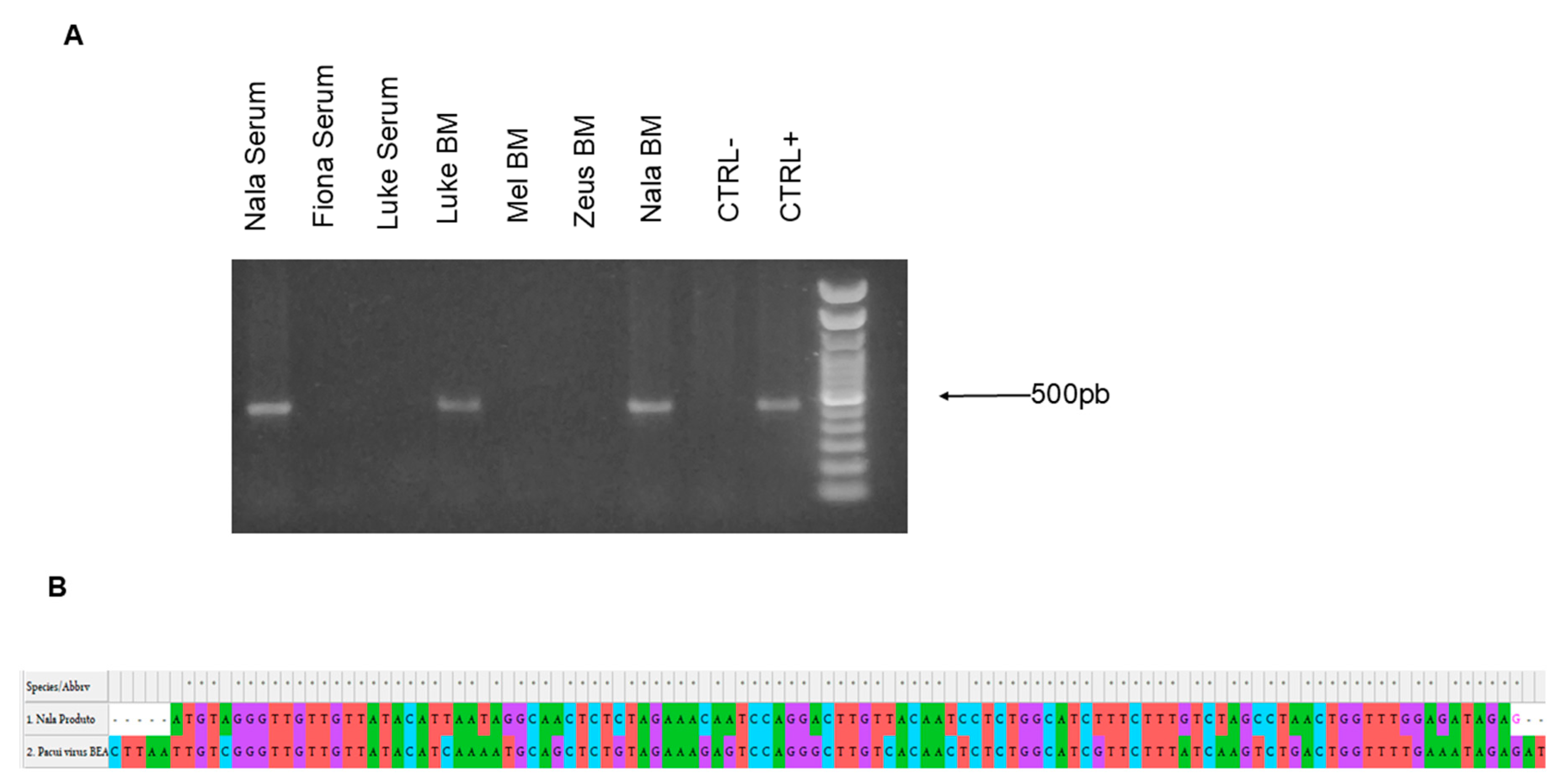

3.3. The RT-PCR-Based Assay Detected the Infection of a Sand Fly-Borne A Group Genome in Clinical Samples of Dogs with VL

We decided to apply the designed RT-PCR assay in clinical samples from dogs with VL. Twenty-five bone marrow (BM) samples or sera were collected and processed for RNA extraction, viral RNA extraction, and cDNA synthesis. The samples from two dogs, Nala and Luke, both from the same region, the West Zone of the City of Rio de Janeiro, were positive with primers A (

Figure 3A). The amplicon sequencing analysis was performed, and the result showed a high identity with the L-segment of Pacuivirus group (Peribunyaviridae) (

Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Agarose gel of positive samples and product blast alignment. (A)Sera or bone marrow (BM) samples from five dogs with VL were processed and submitted to RT-PCR. The samples from serum and BM from Nala and the BM sample from Luke were positive for the primer group A. (B). The partial alignment of the blast search of the PCR product from the serum sample from “Nala” with part of the L segment from Pacui virus.

Figure 3.

Agarose gel of positive samples and product blast alignment. (A)Sera or bone marrow (BM) samples from five dogs with VL were processed and submitted to RT-PCR. The samples from serum and BM from Nala and the BM sample from Luke were positive for the primer group A. (B). The partial alignment of the blast search of the PCR product from the serum sample from “Nala” with part of the L segment from Pacui virus.

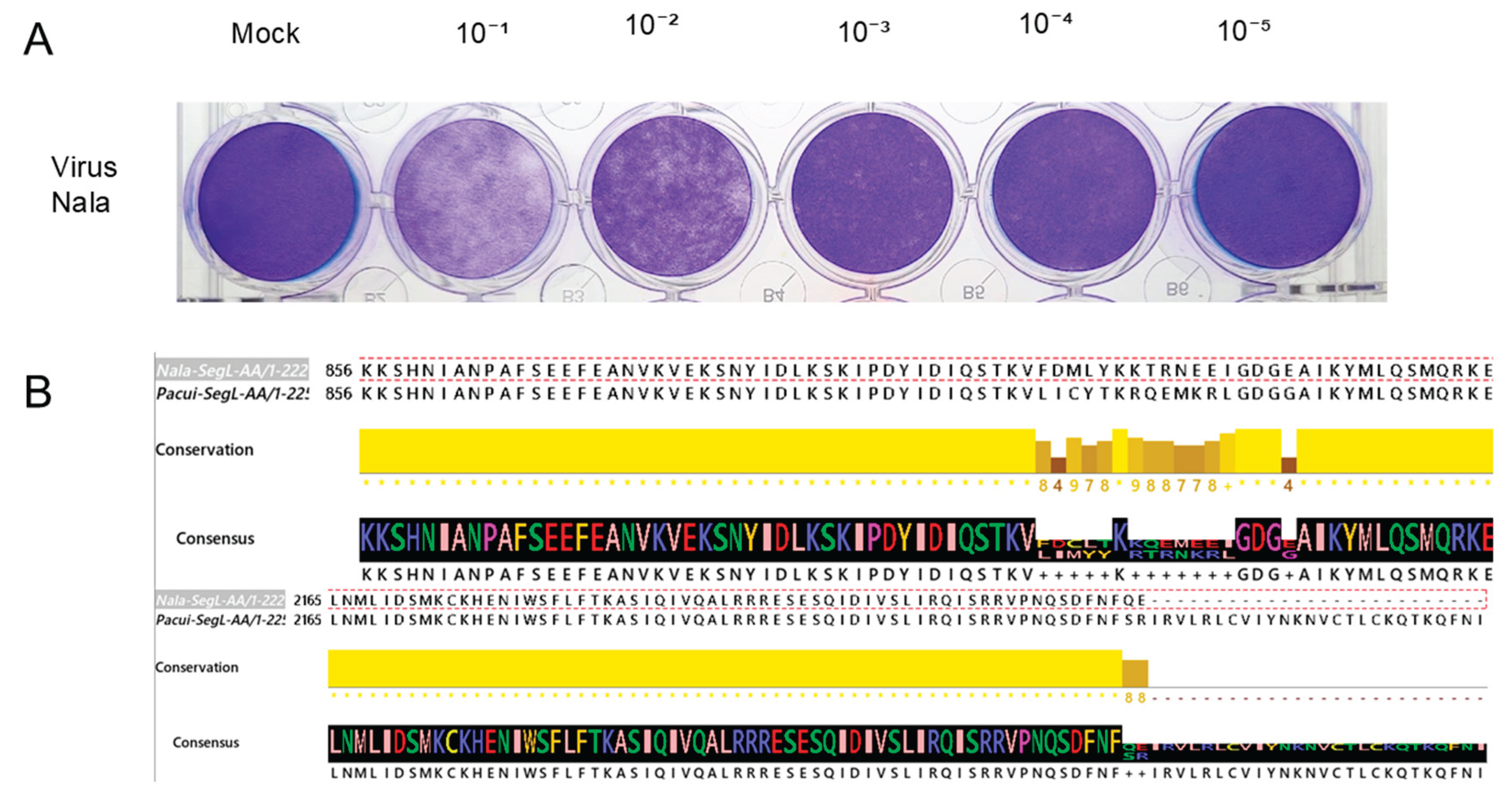

3.4. Cultivation of the Isolated Virus and Genome RNA Sequencing

Of the two positive serum samples from the dogs shown above, we obtained an extra sample from the dog named “Nala” for viral isolation. Around 200 μL was inoculated in BHK-21 cell plates and cultivated for six passages until a cytopathic effect was observed. Plaque assay determined the viral titer (Figure 4. A). All supernatants from cultures were collected and stored at -80°C. The RNA was extracted from the supernatant and sent for RNA sequencing. After sequencing and analyzing the reads using the methodology described in the methods section, the partial sequences for the L and M segments and the whole sequence for the segment S were assembled. The sequences have been deposited in the NCBI database under the accession numbers: Segment L = PV947624, Segment M = PV947625, and Segment S = PV947626. The sequences were compared using the NCBI BlastN algorithm and observed “99.9%”, “99.93%”, and “100%” identity, respectively. More in-depth analysis of the differences between the segments L and M is in progress. The predicted L segment amino acid sequence presents two conspicuous differences(Figure 4.B) when aligned to the Pacui virus sequence in the NCBI database. “Nala” derived L segment sequence displays 12 different amino acid changes depicted in the figure. The end of the predicted protein sequence, aa 2226 and 2227, has amino acid substitutions. Nala`s L sequence ends earlier at the 2227th amino acid, while the Pacui virus extends until 2253 amino acids.

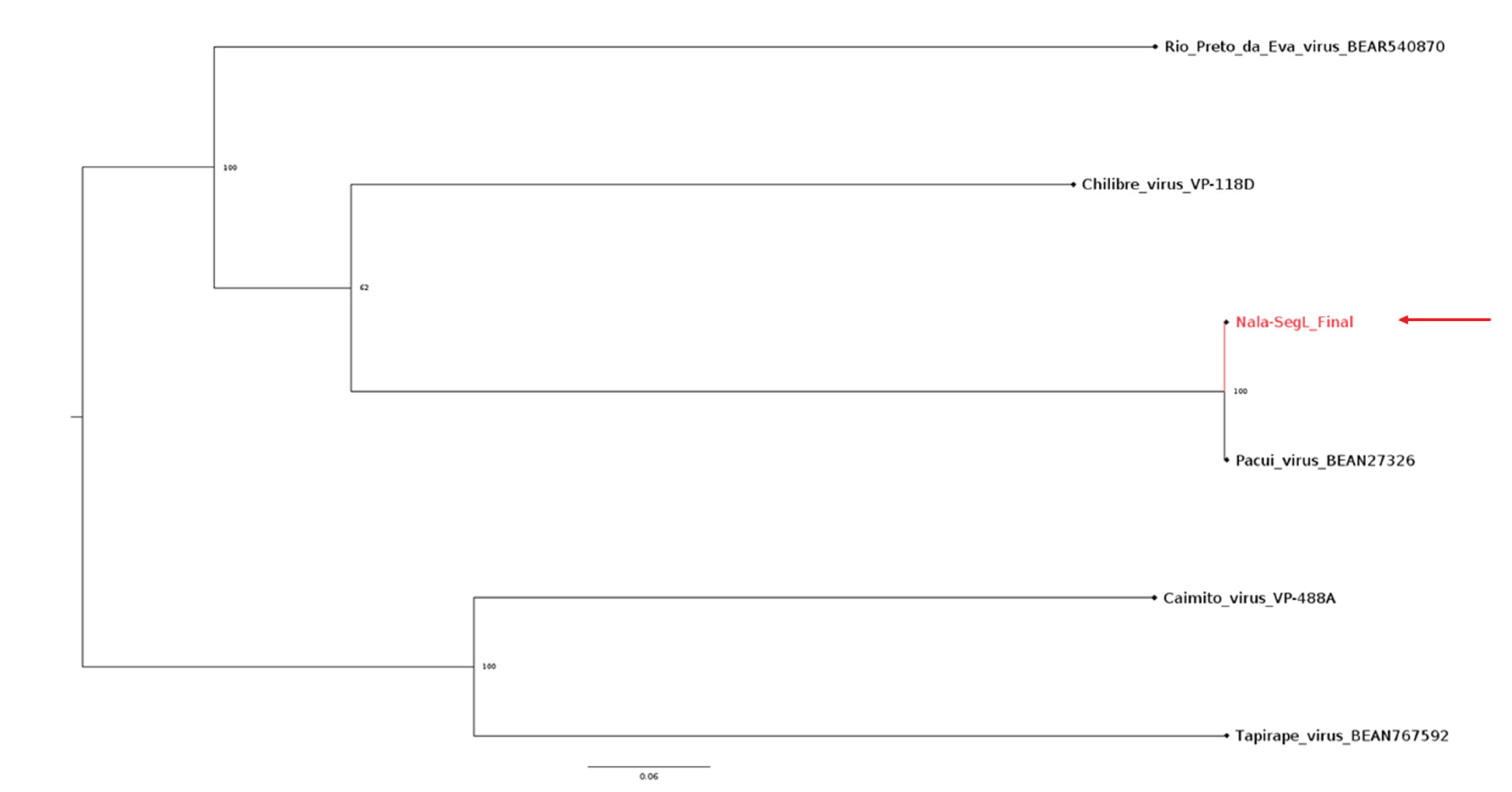

3.5. Phylogeny of the L Segment of Pacuvirus and Nala-Derived Sequences

Due to the similarities between the “Nala” isolate and Pacui found in the NCBI database, we have done an alignment with Pacui and other similar Pacuviruses to generate a phylogenetic tree for the L-segment of Pacuvirus (

Figure 5). As predicted, the phylogenetic analysis confirmed the close relatedness of the Nala isolate with the Pacui virus branch.

Figure 5.

Viral titer and amino-acid comparison. (A) Plaque assay was used in the laboratory to measure the viral titer of the Nala-originated virus. (B)The partial amino acid sequences from the isolate “Nala” virus aligned with part of Pacui’s L segment. The alignment shows two regions with differences in the amino acid sequences. In black are depicted the consensus sequences, and the yellow line indicates the conservation across both sequences.

Figure 5.

Viral titer and amino-acid comparison. (A) Plaque assay was used in the laboratory to measure the viral titer of the Nala-originated virus. (B)The partial amino acid sequences from the isolate “Nala” virus aligned with part of Pacui’s L segment. The alignment shows two regions with differences in the amino acid sequences. In black are depicted the consensus sequences, and the yellow line indicates the conservation across both sequences.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of the segment L of Pacuvirus with the Pacui-like isolate. The tree displays the position of 5 different Pacuvirus and the Pacui-like isolate, Nala, labelled with a red branch and a red arrow. The tree shows the proximity between Pacuvirus and the Nala isolate virus from Rio de Janeiro.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of the segment L of Pacuvirus with the Pacui-like isolate. The tree displays the position of 5 different Pacuvirus and the Pacui-like isolate, Nala, labelled with a red branch and a red arrow. The tree shows the proximity between Pacuvirus and the Nala isolate virus from Rio de Janeiro.

4. Discussion

Studies of viral co-infection in VL are mainly associated with HIV-1, which is related to aggravation and relapses of the parasite infection, posing a challenge for Public Health [

28,

29,

30]. However, arbovirus transmission in VL-endemic areas is present, and studies on possible co-infections are lacking.

We approached the potential co-infection in dogs with VL by arboviruses transmitted by sand flies. Dogs are the main reservoirs of L. infantum, and co-infection may impact the management of the disease and, potentially, the transmission.

There is growing evidence of co-circulation and the co-infection of sand fly species in the Old World by Phleboviruses [

31,

32], which deserves special attention in Public Health. Dogs with L. infantum can be reservoirs for the Toscana virus in natural co-transmission foci [

33], which adds a layer of complexity in epidemiological studies of VL. In Brazil, Viola phlebovirus was found in Lu. longipalpis, the primary vector of

L. infantum [

34], suggests a potential transmission in VL areas.

In vivo, studies indicate that Sicilian Virus infection potentiates the infection and inflammatory response due to

L. major [

35]. Another study demonstrated that the Sicilian virus in mice infected with LRV1-cured

Leishmania guyanensis (LgyLRV1- ) led to increased parasite burden and tissue dissemination [

36]. We reported i

n vivo and in vitro that the co-infection of

L. amazonensis and the Amazonian Phlebovirus Icoaraci (ICOV) increased the parasite load with the modulation of the antiviral response [

37]. Importantly, we showed that

L. amazonensis/ICOV co-infection also led to the increase of the ICOV viral particle production along with the enhanced parasite load, which suggests a mutually beneficial process in the host [

38].

In the present paper, we tackled the detection of sand fly-borne tri-segmented negative RNA virus in VL-infected dogs. To pursue this goal, we had to analyze the genome of American sand fly-borne Bunyaviricetes, considering the high diversity of species described so far. Our analysis showed two main groups, designated A and B, based on the segregation of RdRP sequences. Group B was comprised mainly of Phlebovirus species, including Old World Rift Valley and Toscana virus. Pacuivius species branched in group A. This group belonged to the Phlebovirus Genus but was recently classified as separate. Our RT-PCR assays demonstrated the presence of PACUI virus-related genome in the bone marrow and sera from dogs with VL. Notably, the co-infection originated from a municipality located 140km from the State Capital, Rio de Janeiro, and in the western zone of the Rio de Janeiro urban area, where canine leishmaniasis is prevalent. These findings suggest that Pacui-related virus /

Leishmania silent co-infections occur in peri-urban areas of a densely populated City such as Rio de Janeiro. Pacuivirus was isolated in 1961 in the Amazonian Region and found in

Lu-flaviscuttelata and from different wild rodent species [

39]. Later, the genomes of Pacui and the related virus Rio Preto da Eva were sequenced [

40].

We isolated the virus from the serum of a VL-positive dog, Nala. The whole genome sequencing was conducted and the bioinformatic analysis confirmed de relatedness to Pacui virus. Pacui virus was found in thousands of specimens of

Lu. flaviscutellata and from the rodent Oryzomys sp [

18], located in the north of Brazil, Belém. Neutralizing antibodies were found in other animals in the state of Amapá[

39]. Our finding of Pacui-related in Rio de Janeiro suggests a more extensive distribution of the virus and adaptation to domestic dogs and sand fly species, perhaps

Lu. longipalpis. The extensive circulation of originally described Amazonian Phlebovirus species in other regions outside the Amazon may be illustrated with the Icoaraci virus, also initially described in Belém, North of Brazil. For instance, Icoaraci positive serum was found in non-human primates in Ilheus, Southern Brazil [

41]). These findings highlight the importance of an extensive and consistent survey for sand fly-borne viruses across different regions of Brazil. Moreover, intriguing questions remain to be addressed: Does the VL condition make dogs more susceptible to Pacui or other related sand fly-transmitted viruses? Do co-infected dogs display a high parasite load? What is the role of the viral co-infection in managing the disease?

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data suggest that the RT-PCR assay is functional in detecting Bunyaviricetes infections in tissues and may be applied in epidemiological studies. Further development of the technique is in progress to increase its sensitivity. The complete genome description of Nala-Pacui virus will be presented in another paper.

Author Contributions

DMJA and JVS executed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. MB, EC discussed the results and collected material for analysis. MNL and CRD bioinformatic analysis of genome data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), (E-26/211-20/2021. 267497; (E-26-104/272533).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Renato da Silva Ferreira for the technical assistance.

Availability of data and materials

The nucleic acid sequence of segments L, M, and S of the “Nala” isolate is available in GenBank (Accession numbers: Segment L = PV947624, Segment M = PV947625, and Segment S = PV947626). Gels, alignments, and other data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

UGL

planned and supervised the experiments, wrote the manuscript, and obtained research funding.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable according to item b-ii, 6.1.10 of the Normative Resolution # 55, CONCEA, October 2022.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declares that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| BM |

Bone Marrow (medula óssea) |

| cDNA |

Complementary DNA (DNA complementar) |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FAPERJ |

Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| ICOV |

Icoaraci virus |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin 10 |

| NCBI |

National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| PKR |

Protein Kinase R |

| RdRP |

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| S, M, L |

Small, Medium, Large segments from Bunyaviruses |

| VL |

Visceral Leishmaniasis |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Leishmaniasis [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited 2025 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/leishmaniasis.

- Burza, S.; Croft, S.L.; Boelaert, M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018, 392, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belo, V.S.; Werneck, G.L.; Barbosa, D.S.; Simões, T.C.; Silva, W.B.; Sérgio, S.E.; et al. Factors associated with visceral leishmaniasis in the Americas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013, 7, e2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhay, M.O.; Olliaro, P.L.; Costa, D.L.; Costa, C.H.N. Urban parasitology: visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Trends Parasitol. 2011, 27, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, E.N.; Sobral, H.M.; Sabroza, P.C.; Reis, I.A.; Dias, E.S.; et al. Abundance of Lutzomyia longipalpis in urban households as risk factor of transmission of visceral leishmaniasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016, 111, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, W.S.; Infran, J.O.M.; Oliveira, E.F.; Casaril, E.A.; Barrios, S.P.G.; Oliveira, S.L.L.; et al. Phlebotomine sandfly fauna and association with climatic variables in Central Western Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2022, 59. [Google Scholar]

- ATownsend Peterson Campbell, L.P.; Moo-Llanes, D.A.; Travi, B.; González, C.; María Cristina Ferro et, a.l. Influences of climate change on the potential distribution of Lutzomyia longipalpis sensu lato (Psychodidae: Phlebotominae). International Journal for Parasitology. 2017, 47, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Travi, B.L.; Adler, G.H.; Inmaculada, M.; Cadena, H.; Montoya-Lerma, J. Impact of Habitat Degradation on Phlebotominae (Diptera: Psychodidae) of Tropical Dry Forests in Northern Colombia. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2002, 39, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, A.P.R.; Carvalho TDGde Werneck, G.L. Is There an Association Between Exposure to Cats and Occurrence of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Humans and Dogs? Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2018, 18, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visceral leishmaniasis - PAHO/WHO [Internet]. Pan American Health Organization; [cited 2025 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/leishmaniasis/visceral-leishmaniasis.

- Soomro, S.; Tuangpermsub, S.; Ngamprasertwong, T.; Kaewthamasorn, M. An integrative taxonomic approach reveals two putatively novel species of phlebotomine sand fly (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Thailand. Parasites & Vectors. 2025, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, F.; Zé-Zé, L.; Alves, M.J. Sandfly-Borne Phleboviruses in Portugal: Four and Still Counting. Viruses [Internet]. 2022, 14, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergunay, K.; Ayhan, N.; Charrel, R.N. Novel and emergent sandfly-borne phleboviruses in Asia Minor: a systematic review. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2016, 27, e1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, S.; Noronha, L.E.; Tubbs, H.; Cohnstaedt, L.W.; Wilson, W.C.; Mire, C.; et al. The increasing threat of Rift Valley fever virus globalization: strategic guidance for protection and preparation. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2023, 60, 1197–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, S.S.; Wilson, D.; Feldmann, H.; Hawman, D.W. A Look into Bunyavirales Genomes: Functions of Non-Structural (NS) Proteins. Viruses. 2021, 13, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowen, A.C. It’s in the mix: Reassortment of segmented viral genomes. PLoS Pathogens [Internet]. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro, F.; Anabela Vilares Martins, S.; Reis, T.; Osório, H.C.; Alves, M.J.; et al. Co-Circulation of Leishmania Parasites and Phleboviruses in a Population of Sand Flies Collected in the South of Portugal. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023, 9, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, W.; Dachraoui, K.; Barhoumi, W.; Cherni, S.; Chelbi, I.; Zhioua, E. Co-circulation of Toscana virus and Leishmania infantum in a focus of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis from Central Tunisia. Acta Tropica. 2020, 204, 105342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Elena Remoli Jiménez, M.; Fortuna, C.; Benedetti, E.; Marchi, A.; Genovese, D.; et al. Phleboviruses detection in Phlebotomus perniciosus from a human leishmaniasis focus in South-West Madrid region, Spain. Parasites & Vectors. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Moriconi, M.; Rugna, G.; Calzolari, M.; Bellini, R.; Albieri, A.; Angelini, P.; et al. Phlebotomine sand fly–borne pathogens in the Mediterranean Basin: Human leishmaniasis and phlebovirus infections. Warburg A, editor. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017, 11, e0005660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M. and Barton, G. J. Jalview Version 2 - a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, C.T.; de Carvalho Vivarini, A.; Pereira, R.M.; Lopes, U.G. Production, Quantitation, and Infection of Amazonian Icoaraci Phlebovirus (Bunyaviridae). Bio Protoc. 2021, 11, e4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegnasew Takele, Tadele Mulaw, Emebet Adem, Rebecca Womersley, Myrsini Kaforou, Susanne Ursula Franssen, Michael Levin, Graham Philip Taylor, Ingrid Müller, James Anthony Cotton, Pascale Kropf. Recurrent visceral leishmaniasis relapses in HIV co-infected patients are characterized by less efficient immune responses and higher parasite load. iScience 2023, 26, 105867.

- Leite de Sousa-Gomes, M.; Romero, G.A.S.; Werneck, G.L. Visceral leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS in Brazil: Are we aware enough? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017, 11, e0005772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Machado, C.A.L.; Sevá, A.D.P.; Silva, A.A.F.A.E.; Horta, M.C. Epidemiological profile and lethality of visceral leishmaniasis/human immunodeficiency virus co-infection in an endemic area in Northeast Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2021, 54, e0795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ergunay, K.; Kasap, O.E.; Orsten, S.; Oter, K.; Gunay, F.; Yoldar, A.Z.; Dincer, E.; Alten, B.; Ozkul, A. Phlebovirus and Leishmania detection in sandflies from eastern Thrace and northern Cyprus. Parasit Vectors. 2014, 7, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alkan, C.; Bichaud, L.; de Lamballerie, X.; Alten, B.; Gould, E.A.; Charrel, R.N. Sandfly-borne phleboviruses of Eurasia and Africa: epidemiology, genetic diversity, geographic range, control measures. Antiviral Res. 2013, 100, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafri, I.; Bitam, I. Phlebotomine sandflies and associated pathogens in Algeria: update and comprehensive overview. Vet Ital. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, M.S.; de Lara Pinto, A.Z.; Pinheiro, A.; Rodrigues, J.S.V.; Melo, F.L.; da Silva, L.A.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Dezengrini-Slhessarenko, R. Viola phlebovirus is a novel Phlebotomus fever serogroup member identified in Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis from Brazilian Pantanal. Parasit Vectors. 2018, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martins-Melo, F.R.; Carneiro, M.; Ramos ANJr Heukelbach, J.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Werneck, G.L. The burden of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Brazil, 1990-2016: A subnational analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018, 12, e0006559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rossi, M.; Castiglioni, P.; Hartley, M.A.; Eren, R.O.; Prével, F.; Desponds, C.; Utzschneider, D.T.; Zehn, D.; Cusi, M.G.; Kuhlmann, F.M.; Beverley, S.M.; Ronet, C.; Fasel, N. Type I interferons induced by endogenous or exogenous viral infections promote metastasis and relapse of leishmaniasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017, 114, 4987–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rath, C.T.; Schnellrath, L.C.; Damaso, C.R.; de Arruda, L.B.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C.; Gomes, C.; Laurenti, M.D.; Calegari Silva, T.C.; Vivarini, Á.C.; Fasel, N.; Pereira, R.M.S.; Lopes, U.G. Amazonian Phlebovirus (Bunyaviridae) potentiates the infection of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis: Role of the PKR/IFN1/IL-10 axis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019, 13, e0007500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dos Santos, J.V.; Freixo, P.F.; Vivarini, Á.C.; Medina, J.M.; Caldas, L.A.; Attias, M.; Teixeira, K.L.D.; Silva, T.C.C.; Lopes, U.G. Endoplasmic Stress Affects the Coinfection of Leishmania amazonensis and the Phlebovirus (Bunyaviridae) Icoaraci. Viruses. 2022, 14, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aitken, T.H.; Woodall, J.P.; De Andrade, A.H.; Bensabath, G.; Shope, R.E. Pacui virus, phlebotomine flies, and small mammals in Brazil: an epidemiological study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1975, 24, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, D.S.; Medeiros, D.B.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Martins, L.C.; de Lima, C.P.; de Oliveira, L.F.; de Vasconcelos, J.M.; Da Silva, D.E.; Cardoso, J.F.; da Silva, S.P.; Vianez-Júnior, J.L.; Nunes, M.R.; Vasconcelos, P.F. Pacui Virus, Rio Preto da Eva Virus, and Tapirape Virus, Three Distinct Viruses within the Family Bunyaviridae. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e00923–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almeida, M.A.B.; Santos, E.D.; Cardoso, J.D.C.; Noll, C.A.; Lima, M.M.; Silva, F.A.E.; Ferreira, M.S.; Martins, L.C.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C.; Bicca-Marques, J.C. Detection of antibodies against Icoaraci, Ilhéus, and Saint Louis Encephalitis arboviruses during yellow fever monitoring surveillance in non-human primates (Alouatta caraya) in southern Brazil. J Med Primatol. 2019, 48, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).