1. Introduction

Probiotics are living microorganisms that provide health benefits to the host when consumed in sufficient amounts [

1]. Among probiotics, the species

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG is particularly notable. This strain forms a biofilm that strengthens the protection of the intestinal mucosa and produces various soluble compounds that promote intestinal health while reducing apoptosis of intestinal cells [

2]. However, in its free form, this microorganism may be vulnerable to reduced cell viability during storage and transit through the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [

3,

4].

The use of a matrix with a potentially prebiotic effect, i.e. a substrate that provides health benefits to the host by selecting desirable microorganisms, can promote a product with even better properties: a symbiotic beverage [

5,

6]. In this context, honey from Africanized bees (

Apis mellifera) has been reported to promote a potential prebiotic effect [

7]. Recently, our research showed that the bee honey from the unique semiarid biome called Caatinga improved the resistance of the probiotic yeast

Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 for long-term refrigerated storage and the tolerance to the stressors in the course of static

in vitro GIT simulation [

8].

Bees collect nectar from plants, secretions from living plant tissues or excretions from insects that feed on sap and transform them through interaction with their own specialized enzymes and store them in the honeycomb, where the mixture undergoes dehydration and maturation until it becomes honey [

9]. Therefore, the plant composition is fundamental to the characteristics of honey, which can be an exclusive natural product with nutraceutical properties that are different from other bee honeys due to its geographical origin with unique morphoclimatic characteristics and biological diversity [

10]. Caatinga is a unique biome of the Northeast region of Brazil characterized by exhaustive hydric stress and a xerophytic vegetation [

11]. This means that various types of stress constantly challenge plants in that biome, requiring them to produce a series of molecules that ensure their survival and persistence, such as phenolic derivatives of different types [

12,

13]. Many of these molecules that are present in nectar must be concentrated during honey production, leading not only to their accumulation but also conferring antioxidant activity to it [

8]. In general, the honey produced in that region is classified as multifloral, given that, even under those difficult conditions, the Caatinga biome presents a great diversity of honey plants [

14]. Samples of this honey were analyzed, specifically from the "Sertão do Pajeú" mesoregion (Pajeú hinterland), in the state of Pernambuco. The results revealed the quantity of phenolic compounds associated with high antioxidant activity, in addition to conferring physiological benefits to cells of the probiotic yeast

S. boulardii CNCM I-745, as mentioned above [

8].

Still within this biome and mesoregion, two plants hold great popular prominence due to their ethnobotanical characteristics. Mastic tree or “Aroeira-do-campo” (

Myracrodruon urundeuva Fr. Allem.) is spread throughout the Caatinga biome of the Northeast region of Brazil, being widely used in local folk medicine from its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties to the treatment of urinary and gynaecological disorders [

15]. The aqueous extracts of its leaves contain high antioxidant activity and has been proposed for the formulation of cosmetics for skin whitening and photoprotectants [

16]. Mesquite tree or “Algaroba” (

Prosopis juliflora) is a plant of Andean origin that was introduced into the Brazilian hinterland in the 1940s. Even though it is still considered an invasive plant, its prodigious adaptation to the Caatinga ecosystem makes it very important for the economy, food preparation, management of degraded areas, preparation of cosmetic products and folk medicine in the region [

17]. Mesquite flour is rich in bioactive polyphenolics that exhibit high antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity [

18].

These plants bloom before most other Caatinga plants, such as Algaroba in July and August, just after the end of the rainy season in the Sertão do Pajeú [

19]. While Algaroba honey is darker and has a high crystallization rate, Aroeira-do-Campo honey is lighter and has a lower crystallization rate. Therefore, honeys predominantly from one of these plants are typically produced in that region and are easily identified. However, there is no information on the physicochemical characteristics of these honeys or their prebiotic potential.

In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the prebiotic potential of honeys from the predominant flowering season of the Sertão do Pajeú region compared to mixed honey from the same region using the probiotic bacterium Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG. However, this analysis was preceded by a physicochemical evaluation of these honeys, generating unprecedented data in the literature on honey from these plants. Another relevant point of the present study was that the bacterial cells cultivated in the presence of these honeys were tested for GI tolerance not only in static simulation but also in dynamic simulation, which much more closely approximates the physioanatomical conditions of the human digestive system. These tests were performed immediately after preparation of the beverages and at different points during long-term storage, to simulate the shelf life of the potential probiotic product. The results presented and discussed below reveal the great prebiotic potential of each of these honeys with biotechnological applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Origin of Bee Honeys

The three samples of fresh bee honeys produced by

Apis mellifera were obtained from the microregion of Pajeú hinterland, Pernambuco, Brazil (Caatinga Biome) located between 07º 16’ 2” and 08º 56’ 01” south latitude, and 36º 59’ 0” and 38º 57’ 45” west longitude. Two of these honeys are of multifloral origin with predominance of aroeira-do-campo and algaroba. The third honey was of a multifloral origin of the same region without predominance, mixed honey. The samples were collected directly from the hives during 2022 and stored at room temperature (25 ±2

oC) until the experimental analyses. The honey samples used were the same as those used by Pinto-Neto et al. [

20] (

Table 1) and analyzed according to subtopic 2.2.

2.2. Physicochemical and Microbiological Parameters of Bee Honey

The bee honeys were analyzed according to the methodologies presented in Pinto-Neto et al. [

8] and are shown in

Table 1. Coloration was measured according to the Pfund color scale. The methods standardized by the Instituto Adolfo Lutz [

21] were used to determine moisture, ash content, diastatic activity, free acidity, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) content, the Lugol reaction and the Lund reaction. The pH value was measured with a potentiometer. The soluble solids content was obtained with a portable refractometer and the results were expressed in ºBrix. Density was determined using a 5 mL glass pycnometer previously calibrated with distilled water. Water activity was measured at 25 ºC using the AquaLab 4TE water activity analyzer. Carbohydrates were determined using High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). The total protein content was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method described by Smith et al. [

22].

The viscosity profiles of the bee honey samples were assessed using a controlled-stress rheometer (DHR-1, TA Instruments) equipped with TRIOS software (TA Instruments) at 20 °C. Measurements were performed with a cone and plate geometry (60 mm diameter, 2.006° cone angle, 64 µm gap). Prior to analysis, the samples were heated to 50 °C, homogenized, and allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. Flow tests were conducted in duplicate across shear rates ranging from 1 to 500 s⁻¹. Texture analysis was performed with a TA.HD Plus Texture Analyser (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, United Kingdom) featuring a 5 kg load cell. Samples were placed in cylindrical containers (50 mm in diameter, 75 mm in height) with a sample height of 35 mm. For the penetration test, a P/10 probe was used, operating at a pre-test speed of 0.5 mm/s, test speed of 2 mm/s, and post-test speed of 2 mm/s. The trigger force was set at 0.5 g, and the probe penetrated 20 mm into the sample. Firmness (maximum penetration force) and consistency (work of penetration, represented by the area under the curve up to the maximum force) were calculated automatically using Exponent software. In the back-extrusion test, a 45 mm diameter disc was utilized. The pre-test and test speeds were set to 1 mm/s, while the post-test speed was 2 mm/s. The trigger force was fixed at 0.5 g, and the disc penetrated 35 mm into the sample. The parameters measured included firmness, consistency, cohesiveness (maximum negative force), and viscosity index (or "work of cohesion," defined as the area under the negative region of the curve, reflecting resistance to withdrawal). These values were also calculated automatically using Exponent software version 6 for Windows (Stable Micro Systems).

Antioxidant activity was assessed using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) reduction potential evaluation methods described by Benzie & Strain [

23] and the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP). To measure electrical conductivity, 10 g of the sample was diluted in 75 mL of distilled water and analyzed with a conductivity meter (Bel Engineering, model - W12D). For total phenols, the Folin-Ciocalteu method was applied [

24]. The flavonoid content was determined according to the methodologies described by Araújo et al. [

12] and the flavonol content was determined according to the methods described by Woisky and Salatino [

25] and Bencherif et al. [

26]. The microbiological integrity of bee honeys was determined for Coliforms and

Escherichia coli [

27] and

Salmonella [

28]. The results are presented as the average of at least two technical replicates.

2.3. Probiotic Bacteria and Cultivation Conditions

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG was grown in 25 mL of MRS broth at 37 ºC for 24 h to prepare stocks in 30% (v/v) glycerol refrigerated at -20 ºC. For each experiment, 2 mL of the frozen culture was used to inoculate 25 mL of MRS broth. The cells were cultivated at 37 ºC for 24 h. Then, a volume of 2.5 mL of this culture was used to inoculate 22.5 mL of fresh MRS broth and the cells were cultivated again under the same conditions. The total culture volume of 25 mL was centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were washed twice with 0.9% (w/v) saline solution and resuspended in 5 mL of 0.9% (w/v) saline solution to produce the beverage inoculum. An aliquot was used for dilution, placed on a solid MRS and the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 ºC. The colonies were counted to determine the initial viability of the cell population by the concentration of colony forming units (CFU) and subjected to flow cytometry.

2.4. Experimental Design of the Formulated Bee Honey Beverages

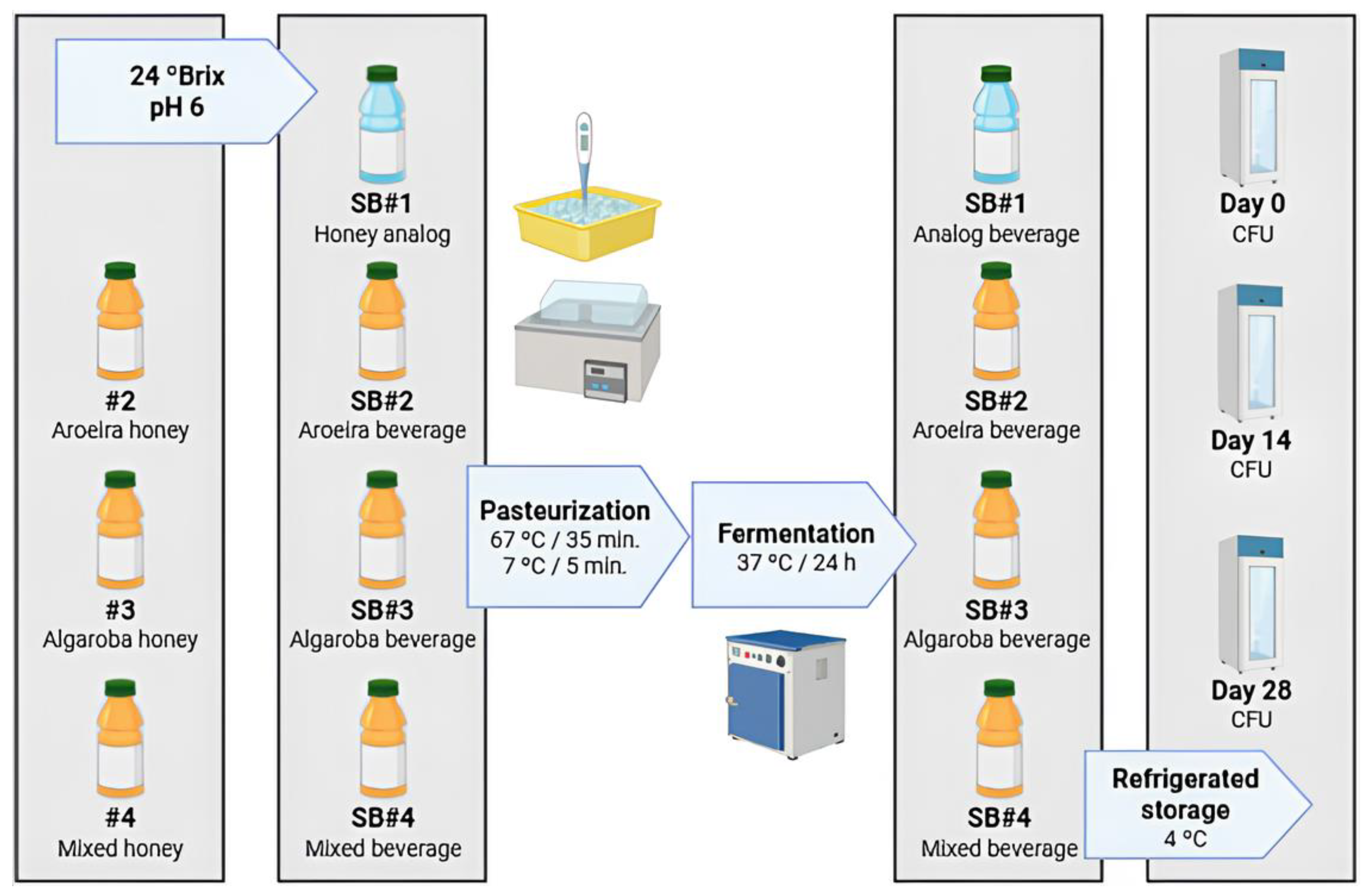

The four fermented synbiotic beverage conditions containing the different bee honeys were made according to the following scheme (

Figure 1). The honeys from the different floras (#2: aroeira-do-campo; #3: algaroba: #4: mixed) were diluted to 24 ºBrix and the solutions were adjusted to pH 6 with 1 M NaOH. For the control condition (#1: honey analog), a bee honey analog was used with the carbon sources matched in proportions like those found in fresh honey for the sugars: fructose, glucose and sucrose. All the formulations were then pasteurized at 67 ºC (±2 ºC) for 35 minutes and cooled by thermal shock in an ice bath at 7 ºC (±2 ºC) for 5 min. All the formulated conditions were inoculated with 3 mL of the seeding inoculum (10 % v/v) and incubated for fermentation at 37 ºC for 24 h. Samples were taken before the fermentation stage and after 24 h of fermentation. The beverages made in biological duplicates were then immediately packaged for storage under refrigeration at 4 ºC and sent for analysis of

in vitro GIT simulations and storage time, both for 0, 14 and 28 days.

2.5. Measuring the Metabolic Activity of the Probiotic

2.5.1. Carbohydrates (Sucrose, Fructose and Glucose) and Lactic Acid

The quantification of carbohydrate (sucrose, glucose, and fructose) and lactic acid was carried out by HPLC, using a Shimadzu device (model LC 2060C) equipped with a quaternary gradient pump, an automatic injector, a refractive index (RID-20A) and diode array detectors. The isocratic chromatographic separation was performed on a Bio-Rad Aminex® HPX-87H ion exchange column (300 x 7.8 mm, 9 µm). The mobile phase was 5 mM Sulphuric acid, the flow rate was set to 0.5 mL/min, the column temperature to 25 °C and the injection volume to 20 µL. The samples were diluted with deionized water and filtered through 0.22 µm PES filters. The metabolites were identified by their relative elution times and quantified using the calibration curves prepared with commercial standards. The results are presented as the average of two biological replicates and respective standard deviation.

2.5.2. Phenylethyl Alcohol Ester

The samples were prepared by liquid-liquid extraction using diethyl ether (50% v/v), pre-chilled to -20°C, containing octanol (1 μg/mL) as the internal standard. The extraction was performed by vortexing for 1 min, followed by centrifugation at 10 000 rpm for 5 min to separate the phases. The upper organic phase, containing the extracted compounds, was collected for GC-MS analysis. The samples were analyzed using GC-MS (SCION SQ1/436 GC), equipped with an Rxi-5Sil MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness). The initial oven temperature was set to 40 °C and held for 5 min, followed by a first temperature ramp of 10 °C/min up to 100°C, and a second ramp of 34.5 °C/min up to 250 °C, where it was held for 1 min. The injector and detector temperatures were set to 250 °C [

29,

30]. Compound identification was performed based on fragmentation pattern interpretation, supported by the NIST/EPA/NIH 2020 mass spectral libraries (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The relative abundance of the compounds was calculated based on peak areas in the total ion chromatogram (TIC). The results are reported as the mean values of two biological replicates.

2.6. In Vitro Simulation Tests of the GIT

The beverage samples containing the different bee honeys were subjected to two

in vitro GIT simulation systems. A static system according to the harmonized INFOGEST 2.0 protocol [

31] and a dynamic system more realistic to human physioanatomical conditions based on the standardized conditions found in the international consensus for static [

32] and semi-dynamic systems [

33] was used for the best performing sample in the static simulation. In this way, the first method was used to analyze the samples as soon as they were formulated and during their storage time under refrigeration, and the second method was used for more reliable confirmation of the samples as soon as they were formulated.

2.6.1. Static Simulation of the GIT Under Refrigerated Storage

The viability and cell vitality of

L. rhamnosus GG to gastrointestinal digestion conditions were assessed using the INFOGEST 2.0 harmonized

in vitro digestion method [

31], which exposes the compound to conditions simulating the mouth, stomach and small intestine with the appropriate electrolyte solutions, enzymes, pH and digestion time. In short, at the oral phase, the sample was mixed with 1x simulated salivary fluid solution (SSF) (KCl 15.1 mmol/L, KH

2PO

4 3.7 mmol/L, NaHCO

3 13.6 mmol/L, MgCl

2⋅(H

2O)

6 0.15 mmol/L, (NH

4)

2⋅CO

3 0.06 mmol/L and HCl 1.1 mmol/L), 1.5 mmol/L CaCl

2⋅(H

2O)

2 and purified water in a ratio of 1:1. The mixture was incubated at 37 ºC in a shaking bath (B. Braun Biotech model Certomat WR, Melsungen, Germany) under horizontal agitation (120 rpm) during 2 min. The gastric phase consisted in the addiction of 1x simulated gastric fluid (SGF) (KCl 6.9 mmol/L, KH

2PO

4 0.9 mmol/L, NaHCO

3 25 mmol/L, NaCl 47.2 mmol/L, MgCl

2⋅(H

2O)

6 0.12 mmol/L, (NH

4)

2⋅CO

3 0.5 mmol/L and HCl 15.6 mmol/L), porcine pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich P7012; final concentration 2000 U/mL) and 0.15 mmol/L CaCl

2⋅(H

2O)

2. The pH was adjusted to 3.0 by adding HCl 1 M and the mixture was incubated at 37 ºC for 2 h under agitation at 120 rpm. The intestinal phase was simulated by the addition of simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) (KCl 6.8 mmol/L, KH

2PO

4 0.8 mmol/L, NaHCO

3 85 mmol/L, NaCl 38.4 mmol/L, MgCl

2⋅(H

2O)

6 0.33 mmol/L and HCl 8.4 mmol/L), porcine pancreatin (Sigma-Aldrich P7545; final concentration 100 (p-Toluene-sulfonyl-L-arginine methyl ester/TAME) U/mL), 10 mmol/L bile solution and 0.6 mmol/L CaCl

2⋅(H

2O)

2. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using NaOH 1 M and the mixture was incubated at 37 ºC for 2 h under agitation (120 rpm). Samples were collected before the simulation and after the gastric and enteric phases and sent for plating to count CFUs and submitted to flow cytometry according to the methodologies described below. The experiment was carried out in biological duplicate.

2.6.2. Dynamic Simulation of the GIT

The viability and cell vitality of

L. rhamnosus GG to gastrointestinal digestion conditions also were analyzed based on standardized conditions outlined in international consensus for static [

32] and semi-dynamic [

33]

in vitro digestion protocols using individual reactors within a gastrointestinal system (Dynamic

In Vitro GastroIntestinal Simulator/DIVGIS), as described by [

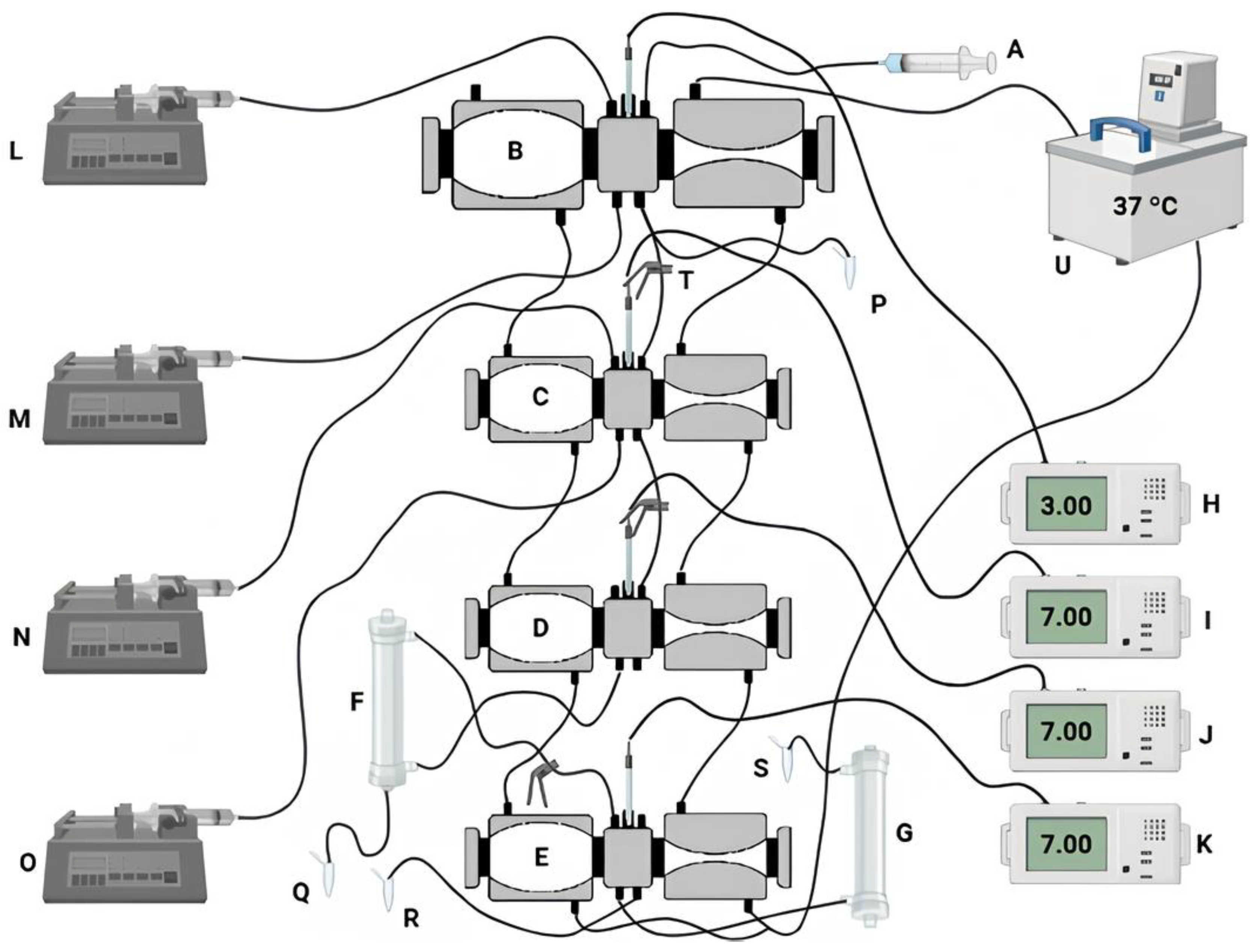

34]. The DIVGIS (

Figure 2) is composed of four compartments (stomach, duodenum, jejunum and ileum) that replicate the primary conditions of human gastrointestinal digestion. Each compartment consists of two interconnected acrylic reactors with flexible walls (stomacher bags) connected by silicone tubing. Peristaltic movements were simulated through the alternating compression and relaxation of the flexible walls, achieved by circulating water at 37°C through each reactor. Gastric and intestinal secretions were freshly prepared and continuously introduced into the reactors using syringe pumps set to specific flow rates. The jejunum and ileum compartments were linked to hollow fiber membranes (Repligen Minikros, S02-S05U-05-P; Breda) to mimic nutrient absorption in the small intestine. These membranes separated the fluids into three distinct fractions: jejunal filtrate, ileal filtrate, and non-ileal filtrate [

35]. The digestion parameters were assessed following the method outlined by Fernandes et al. [

36].

A volume of 50 mL of the sample that showed the best performance in the

in vitro static simulation of the GIT was used in biological duplicate under the following conditions. The oral phase was carried out in a static digestion bath at 37 ºC, by adding simulated salivary fluid (SSF) (KCl 15.1 mmol/L, KH

2PO

4 3.7 mmol/L, NaHCO

3 13.6 mmol/L, MgCl

2(H

2O)

6 0.15 mmol/L, (NH

4)

2CO

3 0.06 mmol/L, CaCl

2(H

2O)

2 1.5 mmol/L) and stirring at 120 rpm for 2 min [

31]. After the oral phase, the sample was introduced into the system via the gastric compartment and simulated gastric fluid (SGF) (KCl 6.9 mmol/L, KH

2PO

4 0.9 mmol/L, NaHCO

3 25 mmol/L, NaCl 47. 2 mmol/L, MgCl

2(H

2O)

6 0.12 mmol/L, (NH

4)

2CO

3 0.5 mmol/L, CaCl

2(H

2O)

2 0.15 mmol/L) and pepsin (2000 U/mL) and lipase (120 U/mL) were secreted continuously at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Constant volumes were transferred to the duodenum compartment at predefined regular times and then simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) (KCl 6.8 mmol/L, KH

2PO

4 0, 8 mmol/L, NaHCO

3 85 mmol/L, NaCl 38.4 mmol/L, MgCl

2(H

2O)

6 0.33 mmol/L, CaCl

2(H

2O)

2 0.6 mmol/L), bile salts and pancreatin solution were secreted continuously at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. At a predefined time, a constant volume of chyme was transferred to the subsequent compartment. The pH was continuously adjusted with HCl (1 mol/L) or NaOH (1 mol/L) to reach pH 2.0 or 7.0 in the gastric and intestinal phases, respectively. The digestion experiments lasted approximately 4 h. During

in vitro digestion, samples were collected directly from the lumen of the different compartments, immediately after passing through the stomach and from the jejunal and ileal filtrates and the non-filterate. All the samples were kept in an ice bath during the digestion process. The samples collected from the jejunum and ileum filtrates were used to determine anti-inflammatory activity. The non-filtered portions were then analyzed for colony-forming units (CFU) and flow cytometry to measure cell viability, cell vitality and survival during passage through GIT.

2.7. Measuring the Viability and Survival of the Probiotic

All samples collected were diluted with sterile saline 0.9% (w/v) and plated in MRS Broth. The plates were incubated at 37 ºC for 48 h and the colonies were counted to determine the Colony Forming Units (CFU). Probiotic viability was expressed as CFU/mL. Samples of bee honey beverages stored for 30 days under refrigeration were evaluated for cell viability and survival of probiotic cells under conditions simulating the GIT as described above. Therefore, cell viability was determined at the beginning of the experiment, after acid stress from the gastric tract to the static system, and after the end of the simulation. The number of surviving cells was calculated according to equations 1 and 2:

where S is the percentage of cell survival (%), N

0 is the total viable count (CFU/mL) before exposure to simulated gastrointestinal conditions, N

2 is the total viable count (CFU/mL) after 2 h gastric trait exposure and N

4 is the total viable count (CFU/mL) after enteric trait exposure.

2.8. Measuring Probiotic Cell Membrane Integrity

The membrane integrity of L. rhamnosus GG cells was assessed before the fermentation process, after the formulation of the beverage and during in vitro dynamic simulations of the GIT. Cell suspensions of L. rhamnosus GG were incubated with propidium iodide (1 μg/mL) for 5 min at 25 °C for subsequent reading by flow cytometry.

Bacterial samples stained with propidium iodide (PI) were analyzed using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, USA). Signal acquisition was optimized by applying a primary threshold on forward scatter (FSC-H) and a secondary threshold on fluorescence channel FL1-H to reduce background noise while preserving bacterial events. The gating strategy for distinguishing viable from non-viable populations was adapted to be based on PI fluorescence emission detected in channel FL3-A (670 nm long-pass filter), following methodologies previously described [

37,

38].

2.9. In vitro Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The anti-inflammatory test was carried out following Osman et al. [

39] and Bakka et al. [

40] with some modifications based on Chakou et al. [

41], to test its ability to inhibit the thermal denaturation of Bovin Serum Albumin (BSA). Bee honey, its fractions absorbed in the jejunum and ileum compartments and ibuprofen (positive control) were prepared at concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1% (w/v). The reaction mixture contained 0.45 mL of 0.5% BSA (w/v), 0.05 mL of sample concentrations or ibuprofen, except for the negative control. The sample was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min and then heated to 70 °C for 10 min. After cooling, 2.5 mL of phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) was added to the reaction mixture before measuring A

660. The inhibition of albumin denaturation was calculated using Equation 3. The tests were carried out in biological duplicate.

where D is A

660 of the test sample and C is A

660 of negative control (reading without inhibitor).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The results of the metabolite concentrations and the survival of the bacteria were performed in duplicate and examined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Turkey test using GraphPad Prism 8 with a significance level of 5% (p≤0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physico-Chemical and Microbiological Characteristics of Bee Honeys

The physicochemical characteristics of honey samples, as discussed in Pinto-Neto et al. [

20], including Brix, moisture content, density, and pH, reflected their maturity. Negative results in the Lugol test confirmed the absence of starch and dextrins, while positive outcomes in the Lund reaction indicated the presence and structural integrity of albuminoids (

Table 1). Although pH is not formally included in the parameters set by Brazilian legislation, the measured values align with findings from previous studies and are known to influence honey’s texture, stability, shelf life, and the formation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) [

42,

43,

44]. All samples showed 5-HMF concentrations below the Brazilian regulatory limit of 60 mg/kg, with the exception of honey predominantly derived from aroeira-do-campo blossom [

45,

46,

47]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission recommends a maximum of 40 mg/kg for 5-HMF, though it allows up to 80 mg/kg in honeys produced in tropical climates. Considering the Caatinga biome’s semi-arid conditions, the elevated 5-HMF levels in this sample may be climatologically justified. Honeys rich in algaroba and mixed flowers sources exhibited reduced diastase activity, falling below the Göthe scale value of 8 recommended by Brazilian standards. However, regulations also permit a minimum diastase value of 3, provided that 5-HMF levels remain under 15 mg/kg (

Table 1) [

46].

Table 1.

Physicochemical and microbiological parameters of bee honeys produced by different flower predominances in the Caatinga biome of the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. All replicates had standard deviations p≤0.05.

Table 1.

Physicochemical and microbiological parameters of bee honeys produced by different flower predominances in the Caatinga biome of the state of Pernambuco, Brazil. All replicates had standard deviations p≤0.05.

| Parameters |

Aroeira-do-campo |

Algaroba |

Mixed |

| Colour (Pfund) |

Light Ambar |

Dark amber |

Dark amber |

| Water activity (Aw) |

0,61 ± 0.00 |

0,56 ± 0.02 |

0,59 ± 0.01 |

| Humidity (%) |

14.01 ± 0.80 |

19.56 ± 0.52 |

19.71 ± 0.15 |

| Soluble solids (°Brix) |

85.00 ± 0.00 |

83.00 ± 0.00 |

81.50 ± 0.00 |

| Density (g/cm3) |

1.42 ± 0.06 |

1.42 ± 0.00 |

1.42 ± 0.00 |

| pH |

3.92 ± 0.05 |

3.61 ± 0.07 |

3.78 ± 0.00 |

| Free acidity (mEq/kg of honey) |

56.00 ± 0.01 |

34.50 ± 0.10 |

22.50 ± 0.06 |

| Lactonic acidity (mEq/kg of honey) |

11.00 ± 0.02 |

08.50 ± 0.00 |

25.00 ± 0.20 |

| Total acidity (mEq/kg of honey) |

67.00 ± 0.04 |

43.00 ± 0.02 |

47.50 ± 0.00 |

| Electric conductivity (µS/cm) |

436.25 ± 2.06 |

997.50 ± 0.71 |

270.50 ± 0.71 |

| Ashes (%) |

0.21 ± 0.02 |

0.57 ± 0.02 |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

| Firmness (g) |

57.74 ± 2.75 |

51,97 ± 0.13 |

66.95 ± 1.42 |

| Consistency (g/sec) |

646.61 ± 27.09 |

585.50 ± 3.18 |

753.78 ± 17.15 |

| Cohesiveness (g) |

-29.52 ± 2.98 |

-26.34 ± 0.59 |

-40.50 ± 2.28 |

| Work of cohesion (g/sec) |

-238.99 ± 25.55 |

-204.36 ± 7.19 |

-396.23 ± 17.79 |

| Viscosity (Pa/s) |

14.67 ± 0.37 |

18.46 ± 0.64 |

17.66 ± 0.50 |

| Hydroxymethyl furfural (mg/kg of honey) |

3.04 ± 0.09 |

9.45 ± 0.01 |

8.28 ± 0.11 |

| Diastase activity (Gothe units/g of honey) |

19.17 ± 0.73 |

4.10 ± 0.40 |

3.50 ± 0.20 |

| Glucose (g/100 g of honey) |

26.32 ± 0.23 |

29.83 ± 0.75 |

31.54 ± 0.16 |

| Fructose (g/100 g of honey) |

41.42 ± 0.56 |

32.41 ± 1.04 |

32.92 ± 0.65 |

| Apparent sucrose (g/100 g of honey) |

9.48 ± 0.68 |

9.82 ± 0.33 |

10.33 ± 0.11 |

| Total sugars (g/100 g of honey) |

85.90 ± 0.51 |

72.05 ± 1.45 |

74.79 ± 0.69 |

| Total proteins (g/100 g of honey) |

0.29 ± 0.03 |

0.22 ± 0.01 |

0.22 ± 0.02 |

| Antioxidant activity (FRAP method) (µM FeSO4/mL) |

403.92 ± 0.00 |

145.43 ± 1.62 |

301.38 ± 1.21 |

| Antioxidant activity (DPPH method) (%) |

52.7 ± 3.05 |

44.18 ± 2.32 |

39.32 ± 2.27 |

| Flavonoids (mg Rutin/100 g of honey) |

74.3 ± 0.00 |

102.6 ± 0.00 |

69.4 ± 0.00 |

| Flavonols (mg Quercetin/100 g of honey) |

54.3 ± 0.00 |

75.0 ± 0.00 |

59.5 ± 0.00 |

| Total phenolic (mg Tannic Acid/100 g of honey) |

185.72 ± 2.9 |

256.40 ± 0.64 |

191.31 ± 2.16 |

| Lund reaction |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

| Lugol reaction |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

| Coliforms (CFU/g) |

<10 |

<10 |

<10 |

|

Escherichia coli (CFU/g) |

<10 |

<10 |

<10 |

| Salmonella |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

The total acidity values of the honey samples were generally close to the 50 mEq/kg threshold established by Brazilian legislation for

A. mellifera honey, with the exception of the sample dominated by aroeira-do-campo blossom [

45,

46,

47]. This deviation may be attributed to the botanical origin and the region’s high annual temperatures, especially considering that this honey also exhibited acceptable levels of 5-HMF, satisfactory diastase activity, and contaminant concentrations below Mercosur limits. Ash content across samples remained below the maximum permissible level [

46]. Since mineral presence is closely linked to electrical conductivity, the higher conductivity observed in honey predominantly from algaroba blossom is consistent with its mineral composition. Glucose and fructose concentrations were within the legally defined ranges [

45,

46,

47,

48]. However, sucrose levels exceeded the limits recommended by the Codex Alimentarius and EC (5 g/100 g) and Brazilian legislation (6 g/100 g) [

46]. The total sugar content correlated well with the measured °Brix values. Among the samples, honey from mixed floral sources demonstrated the greatest firmness (66.95 ± 1.42 g), consistency (753.78 ± 17.15 g/s), cohesiveness (-40.50 ± 2.28 g), and work of cohesion (-396.23 ± 17.79 g/s), suggesting a more viscous, cohesive, and structured profile compared to the others

(Table 1). Conversely, the honey derived mainly from mastic blossom exhibited the lowest value for these textural parameters and, correspondingly, the lowest viscosity. Interestingly, despite being the least viscous sample, it also showed the lowest moisture content, a surprising finding, as lower viscosity is typically associated with higher humidity [

49].

The antioxidant activity and total phenolic concentration of mixed honey detected in this study (

Table 1) were within the range of values presented for other mixed honey samples analyzed from the same region, with values intermediate between those of predominantly floral honeys [

8]. We demonstrated that honeys from the Pajeú hinterland, of mixed botanical origin, with 378 µM FeSO4/mL of FRAP antioxidant activity, protected yeast cells from GIT stress and prolonged their viability for extended storage [

8]. Here, as demonstrated below, we found that phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity were decisive in terms of cell longevity compared to the control condition. These results were discussed in light of the literature that relates the antioxidant activity of honey to its phenolic composition, which protects cells from oxidative stress and increases chronological longevity [

50,

51]. However, unlike our previous work with yeast, we did not observe a significant difference (p≤0.05) between the total phenolic composition and antioxidant activities of honeys from different botanical origins in terms of promoting stress tolerance in bacteria.

The results revealed that not all physicochemical properties conformed to the thresholds defined by current Brazilian standards for bee honey. This likely reflects a regulatory framework that does not fully encompass the environmental and botanical heterogeneity found across Brazil. Existing legislation, influenced by international norms, may overlook the unique characteristics of honeys produced in ecologically complex and climatically extreme regions, such as the biome studied here, known for its high endemism and environmental stressors. Our research group has therefore emphasized the importance of incorporating localized data into future policy updates, aiming to establish more inclusive and context-sensitive quality criteria for honeys originating from tropical and semi-arid zones [

8].

3.2. The Metabolism of Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus GG During Fermentation and Storage Under Refrigeration

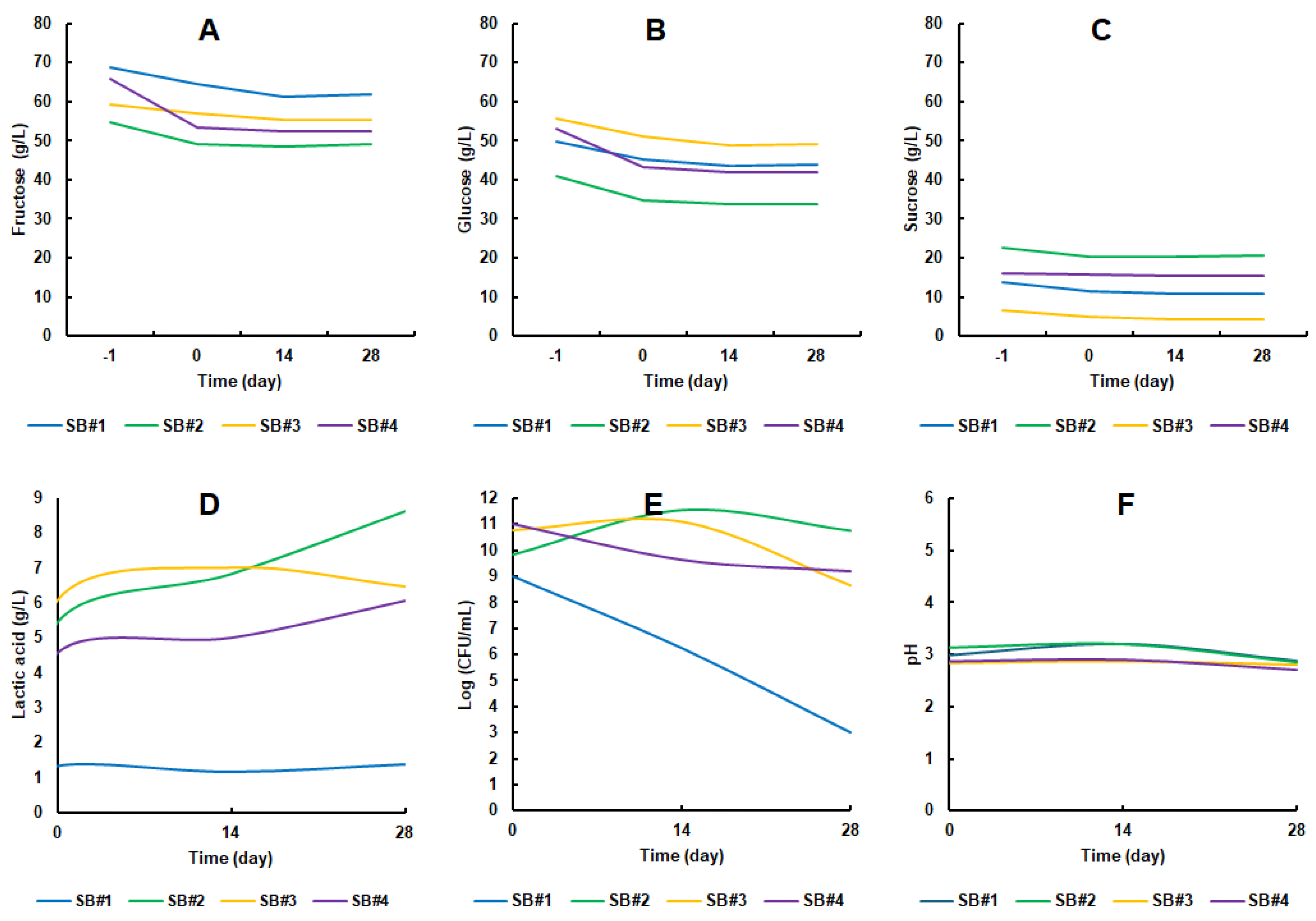

In the bee honey musts of the beverages inoculated with

L. rhamnosus GG, which initiated fermentation at time -1, distinct concentrations of sugars were detected. Across all formulations, fructose (

Figure 3A) consistently appeared in greater amounts than glucose (

Figure 3B), which, in turn, was more abundant than sucrose (

Figure 3C). This distribution mirrors the typical sugar composition of raw bee honey. As reported by Mongi and Ruhembe [

52], Tanzanian bee honeys are predominantly composed of fructose (ranging from 39.5 to 42 g/100 g of honey), followed by glucose (32.0 to 33.7 g/100 g of honey) and sucrose (5.1 to 7.1 g/100 g of honey). Importantly, none of the sugars were fully depleted during fermentation or subsequent cold storage. Nevertheless, the considerable residual sugar content, averaging 109.86 ± 4.83 g/L, does not necessarily pose a limitation. This is especially true in the Brazilian context, where there is a well-established cultural preference for sweet beverages, such as the widely consumed sugarcane juice, which typically contains even higher sugar concentrations [

53]. Moreover, synbiotic beverages based on bee honey may offer potential health benefits. According to Pinto Neto et al. [

54], such formulations could contribute positively to the management of metabolic conditions, including insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Also, according to Mandha et al. [

55], the sweet sensory perception can be masked by the acidity promoted by lactic acid, thus increasing the

drinkability of the beverage.

The lactic acid content at the beginning of the storage period in the beverages containing bee honey was in the range of 4.5 to 6 g/L (SB#2 to SB#4), while in the honey analog (SB#1) this value did not exceed 1.5 g/L. SB#3 and SB#4 reached a peak close to 6 g/L of lactic acid, while SB#2 and distanced itself significantly, reaching almost 9 g/L on day 28 of storage. On the other hand, the control condition SB#1 maintained its production range throughout the storage period (

Figure 3D). This range of lactic acid concentration can also be found in other fermented beverages. [

56] obtained 30.45 ± 1.63 g/L of lactic acid in cow's milk-based kefir, 5.65 ± 0.47 g/L in soy-based kefir, 13.67 ± 1.55 g/L in colostrum-based kefir and 3.51 ± 0.19 in honey-based kefir. The presence of lactic acid is important because it provides a pleasant taste and inhibits the development of undesirable or pathogenic microorganisms [

57].

The cell population of

L. rhamnosus GG started at between 9 and 11 Log CFU/mL and remained stable over 28 days of storage for the formulations containing bee honey (

Figure 3E). The cell viability of SB#3, among the formulations with bee honey, was the one with the worst longevity profile for the probiotic bacteria cells, dropping from 10.79 ± 0.56 Log CFU/mL to 8.67 ± 0.58 Log CFU/mL (

Figure 3E). These results corroborate another study not yet published by our research group, but for a probiotic yeast strain. Surprisingly, cell viability in the SB#1 reference condition dropped dramatically during the 28 days of refrigerated storage, making clear the potential prebiotic effect of bee honeys from the Caatinga Biome on the cell longevity of

L. rhamnosus GG. The cell viability of the probiotic bacteria in the SB#1 formulation fell from 8.98 ± 0.84 Log CFU/mL to 3.00 ± 0.00 Log CFU/mL (

Figure 3E). In other words, there was a decrease of approximately 67 % in cell viability in the control condition. The pH of the medium fell to around 3.0 in all the beverages over the 28 days of storage (

Figure 3F). This pH range observed is slightly below the pH 4.0 range for synbiotic beverages containing

L. rhamnosus [

58] and those formulated by Fiorda et al. [

56], which also maintained an average pH of 4.0.

Phenylethyl alcohol ester was detected was detected only in SB#2 after 14 days of storage. These average values were in the 1 to 2 % range among the more than 35 volatile organic compounds detected (values not shown in figure). Phenylethyl alcohol ester is a volatile substance with a rose-like odor, widely used in food, fragrances and cosmetics and can be produced microbiologically by yeasts [

59]. It is a compound widely associated with floral and sweet notes in the aroma of honey, as well as being important in differentiating honey based on its botanical and geographical origin [

60]. In other words, it is a desirable component for adding sensory and therefore commercial value to a functional beverage.

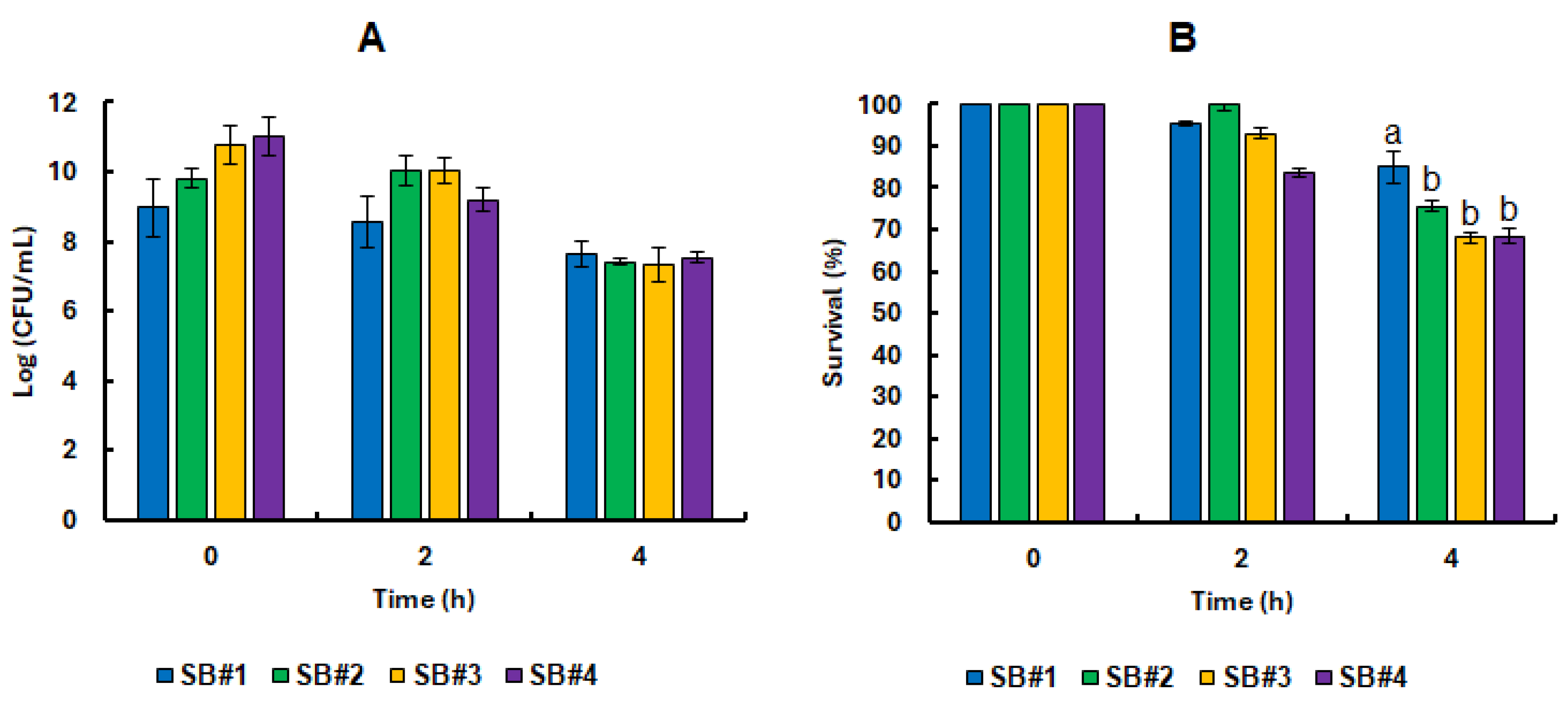

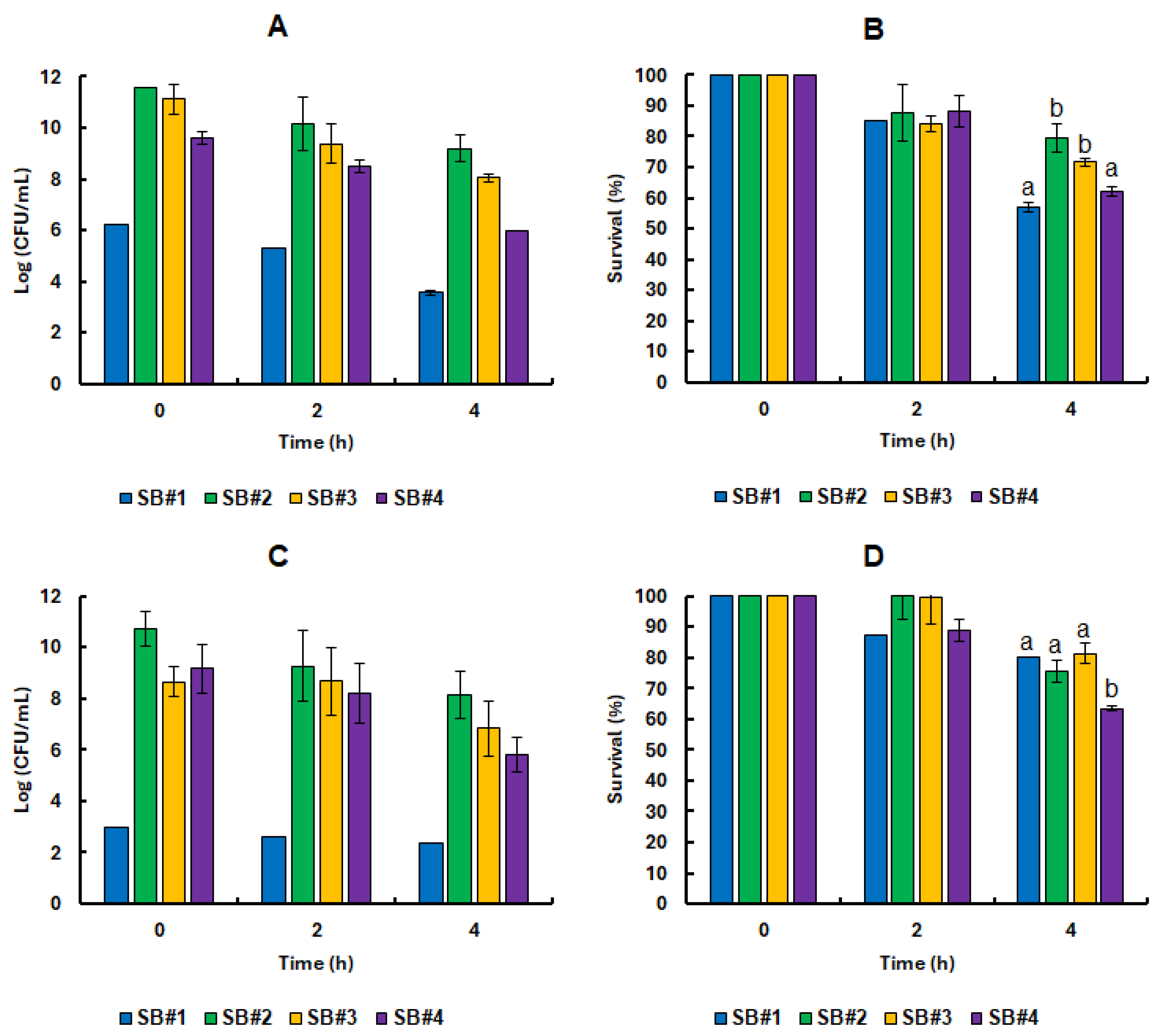

3.3. Survival of the Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus GG Cell in Synbiotic Beverages Under GIT Static Simulation

Samples from the four synbiotic beverages were collected immediately after fermentation at 0 and subjected to

in vitro static gastrointestinal tract (GIT) simulation. At the start of the experiment, the beverages exhibited high microbial loads, ranging from 9 to 11 Log CFU/mL. Remarkably, these probiotic populations demonstrated strong resilience, maintaining activity even after two hours under simulated gastric conditions marked by intense acidic stress (

Figure 4). On average, cell viability reached 9.75 ± 0.48 Log CFU/mL (

Figure 4A), corresponding to a survival rate of 92.17 ± 8.29% (

Figure 4B) across all formulations containing bee honey. Notably, the SB#2 beverage stood out as the only formulation to sustain 100% probiotic cell survival following exposure to the simulated gastric environment. This impressive tolerance persisted despite the combined challenge of pepsin activity and acidic pH. In physiological conditions, hydrochloric acid is secreted by the oxyntic glands in the stomach at concentrations reaching 160 mmol/L, reducing gastric pH to around 0.8. This extreme acidity activates pepsin, an enzyme that cleaves peptide bonds in dietary proteins, facilitating the release of free amino acids into circulation [

61]. At the same time, the low pH serves as a critical antimicrobial barrier. The influx of protons into microbial cells causes intracellular acidification, which disrupts vital cellular functions by damaging proteins and nucleic acids, and forces a metabolic shift from growth to survival, draining energy reserves and halting proliferation [

62,

63,

64].

At the end of the static GIT conditions, the number of viable cells decreased to an average of 7.42 ± 0.10 Log CFU/mL (

Figure 4A), representing an average survival rate of 70.64 ± 4.25 % (

Figure 4B) for the beverages containing bee honey. In this last phase, the bacterial cells face high concentrations of bile salts and pancreatic and hydrolytic enzymes, which severely affect the plasma membrane. In addition, alkaline stress can damage cells by inactivating transporters of vital compounds [

63]. In addition, pH equal to or greater than neutrality also reduces the ionization of enzyme cofactor metals such as iron and copper [

63]. The results obtained in this work were much higher than those observed for

L. rhamnosus ATCC 7469 pre-exposed to guava or passion fruit juice from the Caatinga, which recorded a survival range of less than 50% even in their best formulations [

58,

65]. This difference may be related to the GIT simulation methodology applied in both studies and the composition of the beverages themselves. Our study used the INFOGEST 2.0 standardized in vitro protocol for static simulation. This is an international consensus of more than 35 countries and multidisciplinary experts who have established a standard mechanistic methodology for static GIT simulation systems that most closely approximates human physioanatomical conditions and is easy to reproduce [

31]. In addition, the beverages in this study use bee honey as a potentially prebiotic matrix, while the comparative studies used commercial citrus pectin or pectin extracted from passion fruit from the Caatinga.

Remarkably, high levels of cell survival were observed at the end of the gastrointestinal simulation even in the SB#1 control formulation, which did not contain honey (

Figure 4B). This finding suggests that the presence of bee honey was not, in itself, a decisive factor for the survival of

L. rhamnosus GG in the freshly developed beverage matrix. Nonetheless, as will be discussed further below, prolonged pre-exposure to natural bee honey, as well as its complex physicochemical characteristics, which vary according to predominant floral sources, has been shown to play a more significant role in modulating the behavior of probiotic bacteria. These elements contribute meaningfully to the prebiotic potential of the formulations, highlighting a nuanced interaction between ingredient composition and microbial resilience.

3.4. Impact of Bee Honeys from Different Blooms on the Tolerance of Probiotic Bacteria in Refrigerated Stock and Under Static Simulation of the GIT

The continued presence of bee honey in all synbiotic formulations did not appear to significantly enhance the tolerance of

L. rhamnosus GG to static

in vitro gastrointestinal conditions after extended refrigeration storage (

Figure 5). On the other hand, the cell viability of the probiotic bacteria was always higher in the formulations containing bee honey, even when they were all subjected to the same cell proliferation treatment. More importantly, the presence of bee honeys significantly increased the shelf life of the beverages (

Figure 4E), to the point where the SB#1 formulation reached 3.00 ± 0.00 Log CFU/mL on day 28 of refrigerated storage and 2.40 ± 0.00 Log CFU/mL after static

in vitro simulation of the GIT. In this sense, it is also important to note that, for the health-promoting effect of a probiotic beverage, a minimum of 6 to 7 Log CFU/mL of viable cells is required at the time of consumption [

66].

Our recent publication also reported this cell longevity during refrigerated storage induced by bee honey in yeast cells [

8]. This indicates that the shelf life of this product may be longer when in contact with the honey mixture. Machado et al. [

67] and Caldeira et al. [

68] also observed a positive effect on yogurts fermented with

Lactobacillus acidophilus La-05 and added with honey from native bees in the Caatinga biome. In addition, Melo et al. [

69] showed that different botanical origins of native bee honeys also promote the differential growth of probiotic strains and suggest that the prebiotic potential observed in honeys must be related to the use of phenolic compounds in the metabolic pathways of the probiotics tested. This suggestion is in line with the reports of Pinto-Neto et al. [

8] and Pinto-Neto et al. [

20].

These phenolic derivatives are reported to protect cells against oxidative damage [

7,

70,

71]. Dimitriu et al. [

72] proposed a relationship between the antioxidant and prebiotic activities of honey used in the daily diet precisely because they are readily absorbed by the microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract of animals, protecting microbial cells. Although our results did not show a significant difference in the prebiotic effect of the honeys tested in static

in vitro simulations of the GIT, it was shown that bee honey is still a good carrier of probiotic bacteria by supporting more than 8 Log CFU/mL of live cells in all formulations containing bee honey until the end of the storage time. Coelho et al. [

73] also showed that the strains

Lactobacillus satsumensis LPBF1,

Leuconostoc mesenteroides LPBF2 and

Saccharomyes cerevisiae LPBF3 isolated from honey kefir, when exposed to simulated gastric and intestinal conditions for 4 hours, had cell counts close to 7 Log CFU/mL. This arouses curiosity to test other strains of yeasts and bacteria that our research group has been isolating from the honey of native bees from the Caatinga Biome and from industrial processes that withstand great stress challenges, for which they must have been adapted, such as the industrial fermentation of fuel ethanol.

A major difference observed for this probiotic bacterium compared to the same experimental conditions performed for the probiotic yeast

Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in Pinto-Neto et al. [

20] was that the bacterium was much less tolerant during refrigerated storage. While the yeast started with a cell viability of approximately 8 Log CFU/mL and remained so throughout the analyzed period, the bacterium started with approximately 9 Log CFU/mL and ended with approximately 3 Log CFU/mL for the same analysis period. This may be related to the lower cellular complexity and stress response in bacteria compared to the cellular apparatus of yeast. Furthermore, yeast was more affected by the different botanical origins of honey during the gastrointestinal tract simulation compared to bacteria, which in this study showed almost no preference.

3.5. Nature’s Shield: The Protective Role of Bee Honey on Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus GG Under Lifelike GIT Conditions

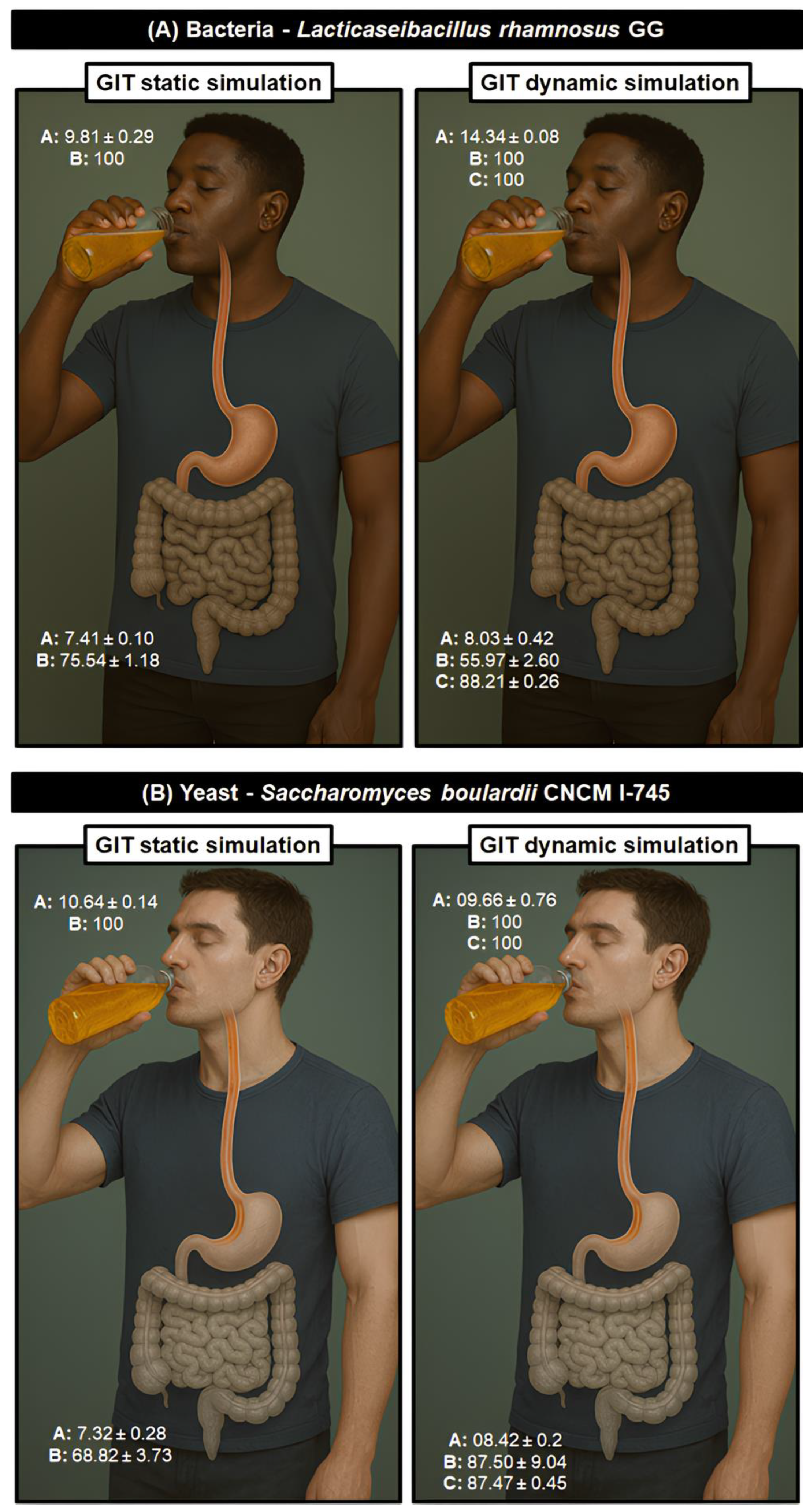

It was recently established that honey produced by

A. mellifera bees from the Caatinga Biome has both prebiotic effect on the probiotic yeast

S. boulardii CNCM I-745 and also enhances its tolerance to GIT [

8]. We have now seen a similar behavior regarding the tolerance of the probiotic bacterium

L. rhamnosus GG during refrigerated storage. The SB#2 formulation, with a predominant botanical origin of aroeira-do-campo showed the best results in longevity. It was chosen to further a dynamic

in vitro GIT simulation test with samples for storage time 0, to reinforce the prebiotic potential of this matrix in more realistic physio-anatomical conditions, simulating the human GIT. In addition to cell proliferation during the storage time, this formulation allowed for at least 17 % more viable cells than the other formulations during the final storage time (

Figure 3E). To this end, in addition to the two GIT simulation methodologies adopted, the estimation of cell viability was also analyzed by flow cytometry for the dynamic

in vitro GIT simulation tests. The results show that the tolerance of

L. rhamnosus GG cells immersed in the prebiotic effect of bee honey with a predominance of mastic blossom shows a significantly lower survival rate when subjected to the most realistic human physioanatomical conditions (static simulation: 75.54 ± 1.18 %; dynamic simulation: 55.97 ± 2.60 %) (

Figure 6A). However, the survival values observed by flow cytometry enumeration were significantly higher than those observed by the classic microbiological method of quantification, with an average of 87.74 ± 0.24% survival, compared to 88.21 ± 0.26 % (

Figure 6A). This observed difference may be related to the number of viable cells that no longer have the ability to reproduce and are, therefore, not considered in the classic microbiological method [

74]. In any case, in both tests, the beverages reached the minimum limits of 6 to 7 Log CFU/mL of viable cells at the time of consumption [

66]. In addition, viable cells that have lost their ability to reproduce can still produce post-biotics capable of promoting health benefits for consumers.

We compared the performance of

L. rhamnosus GG in this study with our previous work with

S. boulardii CNCM I-745 in Pinto-Neto et al. [

20]. In contrast to what was observed here,

S. boulardii CNCM I-745 was much more tolerant to the dynamic simulation of the gastrointestinal tract, showing a survival rate of approximately 87% in both CFU and flow cytometry methods. On the other hand,

L. rhamnosus GG maintained around 56% of survival in CFU and approximately 86% survival in flow cytometry. This implies that, under the conditions adopted, the probiotic yeast was more tolerant to the adverse conditions of the dynamic simulation of the gastrointestinal tract when compared to the probiotic bacteria. Furthermore, more than surviving, the yeast is better able to reproduce and remain alive.

The DIVGIS is a dynamic

in vitro system that is more realistic to the physio-anatomical conditions of the human GIT than the static simulation test. The system allows the collection of a fraction of what would go into the bloodstream absorbed by the jejunum and ileum (

Figure 2). These absorption-simulated samples were tested for the potential anti-inflammatory activities of the bee honey synbiotic beverage. Nevertheless, those samples showed less than 4% of anti-inflammatory activity, much lower than the 71% observed for ibuprofen used as positive control. Therefore, the benefit of the synbiotic beverage appears to be limited to the honey's prebiotic activity on the probiotic lactic acid bacteria tested. This is already a considerable benefit, given that increased bacterial cell viability should contribute to gut microbiota homeostasis or combat enteric dysbiosis.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study clearly show the potential prebiotic properties of honeys from Africanized bees produced in the semi-arid region of the Pernambuco hinterland (Caatinga Biome). Bee honey with predominance aroeira-do-campo nectar showed the results in terms of tolerance of probiotic cells over the long-term storage period. At last, this work may contribute to the development of stable, dairy-free functional products derived from honey, while simultaneously promoting the sustainable use of natural resources from the Caatinga Biome. Such advances have the potential to strengthen local value chains and support communities that are socially and economically vulnerable. Looking ahead, our research group aims to explore the prebiotic potential of other honeys native to the Caatinga and to evaluate their effects against a broader range of microbial strains, including assessments in in vivo gastrointestinal models.

Author Contributions

WPPN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. RFSG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. LL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. MCTM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. RMMR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. LA: Formal analysis; Investigation. AMB: Formal analysis; Investigation. NKSS: Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – review & editing. ACP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AAV: Investigation, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. RBS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MAMJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This research was granted by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Pernambuco (FACEPE) through the Program Arranjos Produtivos Locais (APL) grant number APQ-0434-2.12/20 and the program Locus de Inovação 02/2022 grant number APQ-0161-9.26/22. This work also was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the scope of the strategic funding of UIDB/04469/2020 unit, and by LABBELS – Associate Laboratory in Biotechnology, Bioengineering and Microelectromechanical Systems, LA/P/0029/2020.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

W. P. P. N. acknowledge FACEPE for his doctoral scholarship and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for his sandwich doctoral internship. W. P. P. N. also acknowledges Alessandra Silva Araújo for kindly providing a strain of the probiotic bacterium Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG for the experimental trials. A. C. P. acknowledges FCT for her Assistant Research contract obtained under the scope of Scientific Stimulus Employment with reference 2023.06513.CEECIND. Author(s) also used ChatGPT v4.5 to create visual elements to compose some of the figures in the work and assume(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- FAO/WHO Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; London, UK, 2002.

- Song, H.; Zhang, J.; Qu, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, P.; Zhang, G.; Shang, D. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Microcapsules Inhibit Escherichia Coli Biofilm Formation in Coculture. Biotechnol Lett 2019, 41, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.A.A.; Carvalho, R. de S.F.; Magalhães, N.S.S.; Madruga, M.S.; Athayde, A.J.A.A.; Araújo Portela, I.; Eduardo Barão, C.; Colombo Pimentel, T.; Magnani, M.; Christina Montenegro Stamford, T. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus Acidophilus La-05 and Incorporation in Vegan Milks: Physicochemical Characteristics and Survival during Storage, Exposure to Stress Conditions, and Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Research International 2020, 135, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurso, L. Thirty Years of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG: A Review. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2019, 53, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert Consensus Document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, K.R.; Fernandes, K.E.; Shanahan, E.; Wilson, I.; Blair, S.E.; Carter, D.A.; Cokcetin, N.N. The Potential of Honey as a Prebiotic Food to Re-Engineer the Gut Microbiome Toward a Healthy State. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Neto, W. de P.; Silva, R.K.; Lima, B. de S.; Acioli, G.F. de S.; Paixão, G.A. da; Muniz, B.C.; Silva, P.K.N. da; Costa, R.M.P.B.; Silva, F.S.B. da; Melo, H.F. de; et al. Bee Honey of the Pajeú Hinterland, Pernambuco, Brazil: Physicochemical Characterization and Biological Activity. Food Bioscience 2024, 60, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Standard for Honey CXS 12-1981: Codex Alimentarius: International Food Standards; 2019.

- Miguel, M.; Antunes, M.; Faleiro, M. Honey as a Complementary Medicine. Integr Med�Insights 2017, 12, 1178633717702869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, I.R.; Silva, J.M.C. da; Tabarelli, M.; Lacher Jr., T.E. Changing the Course of Biodiversity Conservation in the Caatinga of Northeastern Brazil. 2005, 19.

- Araújo, T.A. de S.; Alencar, N.L.; de Amorim, E.L.C.; de Albuquerque, U.P. A New Approach to Study Medicinal Plants with Tannins and Flavonoids Contents from the Local Knowledge. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2008, 120, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, M.P.M.M.; Oliveira, T.K.B.; Ó, N.P.R. do; Sarmento, D.A.; Gadelha, N.C. Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Aroeira) e suas propriedades na Medicina Popular. Revista Verde de Agroecologia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável 2015, 10, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.P.; van den Berg, C.; Santos, F.D.A.R.D. Pollen Analysis of Honeys from Caatinga Vegetation of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Grana 2010, 49, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, F.R.; Silva, M.A.P. da Uso, conhecimento e conservação de Myracrodruon urundeuva: uma revisão sistemática. Research, Society and Development 2020, 9, e2329118851–e2329118851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diógenes, É.S.G.; Silva, A.L.C. da; Neto, F.C. das C.; Silveira, E.R.; Leal, L.K.A.M.; Nicolete, R.; Araújo, T.G. de Evaluation of the Skin Whitening and Antioxidant Activity of Myracrodruon urundeuva Extract (Aroeira-Do-Sertão). Nat Prod Res 2024, 38, 3663–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lemos, A.B.S.; Chaves, G.; Ribeiro, P.P.C.; da Silva Chaves Damasceno, K.S.F. Prosopis Juliflora: Nutritional Value, Bioactive Activity, and Potential Application in Human Nutrition. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2023, 103, 5659–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Galán, A.; Corrêa, A.D.; Patto de Abreu, C. maria; Piccolo Barcelos, M. de F. Caracterización química de la harina del fruto de Prosopis spp. procedente de Bolivia y Brasil. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición 2008, 58, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, F. de C.; Pagotto, M.A.; Aragão, J.R.V.; Roig, F.A.; Ribeiro, A. de S.; Lisi, C.S. The Hydrological Performance of Prosopis Juliflora (Sw.) Growth as an Invasive Alien Tree Species in the Semiarid Tropics of Northeastern Brazil. Biol Invasions 2019, 21, 2561–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Neto, W. de P.; Loureiro, L.; Gonçalves, R.F.S.; Marques, M.C.T.; Rodrigues, R.M.M.; Abrunhosa, L.; de Barros, A.M.; Shinohara, N.K.S.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Vicente, A.A.; et al. Potential Prebiotic Effect of Caatinga Bee Honeys from the Pajeú Hinterland (Pernambuco, Brazil) on Synbiotic Alcoholic Beverages Fermented by Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745. Fermentation 2025, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Adolfo Lutz Métodos Físico-Químicos Para Análise de Alimentos; 1st digital ed.; Instituto Adolfo Lutz: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008.

- Smith, P.K.; Krohn, R.I.; Hermanson, G.T.; Mallia, A.K.; Gartner, F.H.; Provenzano, M.D.; Fujimoto, E.K.; Goeke, N.M.; Olson, B.J.; Klenk, D.C. Measurement of Protein Using Bicinchoninic Acid. Analytical Biochemistry 1985, 150, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Analytical Biochemistry 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orujei, Y.; Shabani, L.; Sharifi-Tehrani, M. Induction of Glycyrrhizin and Total Phenolic Compound Production in Licorice by Using Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Russ J Plant Physiol 2013, 60, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woisky, R.G.; and Salatino, A. Analysis of Propolis: Some Parameters and Procedures for Chemical Quality Control. Journal of Apicultural Research 1998, 37, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencherif, K.; Djaballah, Z.; Brahimi, F.; Boutekrabt, A.; Dalpè, Y.; Lounès-Hadj Sahraoui, A. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Affect Total Phenolic Content and Antimicrobial Activity of Tamarix Gallica in Natural Semi-Arid Algerian Areas. South African Journal of Botany 2019, 125, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2002.

- AOAC International Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005.

- Vidal, E.E.; de Billerbeck, G.M.; Simões, D.A.; Schuler, A.; François, J.M.; de Morais, M.A. Influence of Nitrogen Supply on the Production of Higher Alcohols/Esters and Expression of Flavour-Related Genes in Cachaça Fermentation. Food Chemistry 2013, 138, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, E.E.; de Morais Jr, M.A.; François, J.M.; de Billerbeck, G.M. Biosynthesis of Higher Alcohol Flavour Compounds by the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Impact of Oxygen Availability and Responses to Glucose Pulse in Minimal Growth Medium with Leucine as Sole Nitrogen Source. Yeast 2015, 32, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static in Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A Standardised Static in Vitro Digestion Method Suitable for Food – an International Consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet-Cabero, A.-I.; Egger, L.; Portmann, R.; Ménard, O.; Marze, S.; Minekus, M.; Feunteun, S.L.; Sarkar, A.; Grundy, M.M.-L.; Carrière, F.; et al. A Standardised Semi-Dynamic in Vitro Digestion Method Suitable for Food – an International Consensus. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 1702–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.C.; Coimbra, M.A.; Vicente, A.A. In Vitro Behaviour of Curcumin Nanoemulsions Stabilized by Biopolymer Emulsifiers – Effect of Interfacial Composition. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 52, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.C.; Gonçalves, R.F.; Madalena, D.A.; Vicente, A.A. Towards the Understanding of the Behavior of Bio-Based Nanostructures during in Vitro Digestion. Current Opinion in Food Science 2017, 15, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.-M.; Madalena, D.A.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Influence of the Addition of Different Ingredients on the Bioaccessibility of Glucose Released from Rice during Dynamic in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2021, 72, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günerken, E.; D’Hondt, E.; Eppink, M.; Elst, K.; Wijffels, R. Flow Cytometry to Estimate the Cell Disruption Yield and Biomass Release of Chlorella Sp. during Bead Milling. Algal Research 2017, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, L.; Machado, L.; Geada, P.; Vasconcelos, V.; Vicente, A.A. Evaluation of Efficiency of Disruption Methods for Coelastrella Sp. in Order to Obtain High Yields of Biochemical Compounds Release. Algal Research 2023, 73, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.I.; Sidik, N.J.; Awal, A.; Adam, N.A.M.; Rezali, N.I. In Vitro Xanthine Oxidase and Albumin Denaturation Inhibition Assay of Barringtonia racemosa L. and Total Phenolic Content Analysis for Potential Anti-Inflammatory Use in Gouty Arthritis. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol 2016, 5, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakka, C.; Smara, O.; Hadjadj, M.; Dendougui, H.; Mahdjar, S.; Benzid, A. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Pistacia atlantica Desf. Extracts. Asian Journal of Research in Chemistry 2019, 12, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakou, F.Z.; Boual, Z.; Hadj, M.D.O.E.; Belkhalfa, H.; Bachari, K.; El Alaoui-Talibi, Z.; El Modafar, C.; Hadjkacem, F.; Fendri, I.; Abdelkafi, S.; et al. Pharmacological Investigations in Traditional Utilization of Alhagi maurorum Medik. in Saharan algeria: In Vitro Study of Anti-Inflammatory and Antihyperglycemic Activities of Water-Soluble Polysaccharides Extracted from the Seeds. Plants 2021, 10, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, L. da C.; Azeredo, M.A.A.; de Souza, S.R.; Dutra, V.M.L. Protein Contents and Physicochemical Properties in Honey Samples of Apis Mellifera of Different Floral Origins. Food Chemistry 2003, 80, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, S.M.; Zaluski, R.; Pereira Lima, G.P.; Mazzafera, P.; de Oliveira Orsi, R. Characterization of Coffea arabica Monofloral Honey from Espírito Santo, Brazil. Food Chemistry 2016, 203, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.Y.; Miao, X. Pathway of 5-Hydroxymethyl-2-Furaldehyde Formation in Honey. J Food Sci Technol 2019, 56, 2417–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Community (EC) Council Directive 2001/110/EC of 20 December 2001 Relating to Honey; 2002.

- Brasil Regulamento Técnico de Identidade e Qualidade Do Mel; 2000.

- Codex Alimentarius Revised Codex Standard for Honey; 2022.

- Terrab, A.; Recamales, A.F.; Hernanz, D.; Heredia, F.J. Characterisation of Spanish Thyme Honeys by Their Physicochemical Characteristics and Mineral Contents. Food Chemistry 2004, 88, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafa, K.D.; Sundramurthy, V.P.; Subramanian, N. Rheological and Thermal Properties of Honey Produced in Algeria and Ethiopia: A Review. International Journal of Food Properties 2021, 24, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevia, M.; Rasines, S.; Cantero, L.; Sancho, M.T.; Fernández-Muiño, M.A.; Osés, S.M. Chemical Extraction and Gastrointestinal Digestion of Honey: Influence on Its Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Foods 2021, 10, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alugoju, P.; Janardhanshetty, S.S.; Subaramanian, S.; Periyasamy, L.; Dyavaiah, M. Quercetin Protects Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pep4 Mutant from Oxidative and Apoptotic Stress and Extends Chronological Lifespan. Curr Microbiol 2018, 75, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongi, R.J.; Ruhembe, C.C. Sugar Profile and Sensory Properties of Honey from Different Geographical Zones and Botanical Origins in Tanzania. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Lima, C.; Miranda, R.; Seraglio, S.; Barbosa, E.; Souza, A.; Cardoso, D. Sensorial Quality of Sugarcane Juice with the Addition of Fruits Pulp from the Semi-Arid. Research, Society and Development 2020, 9, 200973745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Neto, W. de P.; Costa de Lucena, T.M.; Alves da Paixão, G.; Shinohara, N.K.S.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Vicente, A.A.; de Souza, R.B.; de Morais Junior, M.A. Symbiotic Honey Beverages: A Matrix Which Tells a Story of Survival and Protection of Human Health from a Gastronomic and Industrial Perspective. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 2025, 40, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandha, J.; Shumoy, H.; Devaere, J.; Schouteten, J.J.; Gellynck, X.; de Winne, A.; Matemu, A.O.; Raes, K. Effect of Lactic Acid Fermentation of Watermelon Juice on Its Sensory Acceptability and Volatile Compounds. Food Chemistry 2021, 358, 129809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorda, F.A.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Medeiros, A.P.; Rakshit, S.K.; Soccol, C.R. Development of Kefir-Based Probiotic Beverages with DNA Protection and Antioxidant Activities Using Soybean Hydrolyzed Extract, Colostrum and Honey. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2016, 68, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.T.; de, M. Pereira, G.V.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Microbial Communities and Chemical Changes during Fermentation of Sugary Brazilian Kefir. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 26, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.; Santos, E.; Azoubel, P.; Ribeiro, E. Increased Survival of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus ATCC 7469 in Guava Juices with Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions during Refrigerated Storage. Food Bioscience 2019, 32, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.D.; Romeiro, T.C.O. da S.; Flores, A.V.; Severiano, R.L. Germinação e biometria de frutos e sementes de Prosopis juliflora (Sw) D.C. Ciência Florestal 2018, 28, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.A.; Kılıç-Büyükkurt, Ö.; Aboul Fotouh, M.M.; Selli, S. Aroma Active Compounds of Honey: Analysis with GC-MS, GC-O, and Molecular Sensory Techniques. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 134, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Integrated Upper Gastrointestinal Response to Food Intake. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 640–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, N.; Liu, L. Microbial Response to Acid Stress: Mechanisms and Applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, A.A.; Pinto-Neto, W. de P.; da Paixão, G.A.; Santos, D. da S.; De Morais, M.A.; De Souza, R.B. Journey of the Probiotic Bacteria: Survival of the Fittest. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orij, R.; Brul, S.; Smits, G.J. Intracellular pH Is a Tightly Controlled Signal in Yeast. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2011, 1810, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Andrade, R.; Gouveia, E. Utilization of the Pectin and Pulp of the Passion Fruit from Caatinga as Probiotic Food Carriers. Food Bioscience 2017, 20, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasika, D.M.; Vidanarachchi, J.K.; Rocha, R.S.; Balthazar, C.F.; Cruz, A.G.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Ranadheera, C.S. Plant-Based Milk Substitutes as Emerging Probiotic Carriers. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 38, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, T.A.D.G.; de Oliveira, M.E.G.; Campos, M.I.F.; de Assis, P.O.A.; de Souza, E.L.; Madruga, M.S.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Pintado, M.M.E.; Queiroga, R. de C.R. do E. Impact of Honey on Quality Characteristics of Goat Yogurt Containing Probiotic Lactobacillus Acidophilus. LWT 2017, 80, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, L.A.; Alves, É.E.; Ribeiro, A. de M.F.; Rocha Júnior, V.R.; Antunes, A.B.; Reis, A.F. dos; Gomes, J. da C.; Carvalho, M.H.R. de; Martinez, R.I.E. Viability of Probiotic Bacteria in Bioyogurt with the Addition of Honey from Jataí and Africanized Bees. Pesq. agropec. bras. 2018, 53, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, F.H.C.; Menezes, F.N.D.D.; de Sousa, J.M.B.; dos Santos Lima, M.; da Silva Campelo Borges, G.; de Souza, E.L.; Magnani, M. Prebiotic Activity of Monofloral Honeys Produced by Stingless Bees in the Semi-Arid Region of Brazilian Northeastern toward Lactobacillus Acidophilus LA-05 and Bifidobacterium Lactis BB-12. Food Research International 2020, 128, 108809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril-Sánchez, A.L.; Quintero-Salazar, B.; Dublán-García, O.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B. Phenolic Compounds in Honey and Their Relationship with Antioxidant Activity, Botanical Origin, and Color. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dżugan, M.; Tomczyk, M.; Sowa, P.; Grabek-Lejko, D. Antioxidant Activity as Biomarker of Honey Variety. Molecules 2018, 23, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu, L.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Preda, D.; Moraru, I.; Băbeanu, N.E.; Oancea, F. The Antioxidant and Prebiotic Activities of Mixtures Honey/Biomimetic NaDES and Polyphenols Show Differences between Honeysuckle and Raspberry Extracts. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, B. de O.; Fiorda-Mello, F.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Rakshit, S.K.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Soccol, C.R. In Vitro Probiotic Properties and DNA Protection Activity of Yeast and Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from A Honey-Based Kefir Beverage. Foods 2019, 8, 485. [CrossRef]

- Chiron, C.; Tompkins, T.A.; Burguière, P. Flow Cytometry: A Versatile Technology for Specific Quantification and Viability Assessment of Micro-Organisms in Multistrain Probiotic Products. J Appl Microbiol 2018, 124, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).