Introduction

In the quest to understand the nature of cancer the point of departure has been provided by one of the most fundamental aspects of living organisms, the capacity for regeneration and self-renewal which constitutes also the hallmark of cancer. It was realized that this property is compartmentalized within organisms and linked to germinal structures or cells that have been endowed with these embryonic features that allow preservation of the capacity of regeneration. This idea led Conheim to the first proposal on the origin of cancer in embryonic remains that persist in adult life disconnected from their original sources and which later in life manifest themselves by growing in an aberrant fashion. Later, histological research established that specialized somatic cells in every tissue, initially known as reserve cells and later as normal stem cells, are responsible for replenishing the tissue cell population continually lost by wear and tear or shed after multiple rounds of proliferation and differentiation. The shared property of indefinite self-renewal between the so-called reserve cells and cancer cells with its double physiological and pathological face led to the assumption that cancer growth arises from a failure of tissue stem cells to respond to regulatory signals that maintain normal tissue architecture. In other words, cancer directly originates in tissue stem cells. The modern concept of the cancer stem cell assumes this hierarchical organization ascribing embryonic/stem features to these cells generally disregarding an origin in embryonic rests. However, this feature is often interpreted as precluding the origin of cancer in committed cells.

Regeneration potential is lost as soon as cells leave the stem cell compartment as first confirmed in the hematopoietic system. Even in the transition from long term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSC) to short-term hematopoietic stem cells (ST-HSC) there is some loss of regeneration potential. In the next stages, transit amplifying cells that expand by continuous cell division, lose the capacity of indefinite self-renewal (1) which is restricted to normal stem cells and cancer cells. A similar contention can apply to other tissues. Muscle satellite stem cells have been shown to lose indefinite self-renewal immediately after their first division.”Pax7+ Myf5- stem cells that undergo asymmetric self-renewal divisions on muscle fibres, give rise to a basal Pax7+ Myf5- stem cell daughter and an apical Pax7+ Myf5- satellite cell with a more restricted proliferative potential” (2)

Mammary epithelium exhibits identical behaviour. Mammospheres isolated by short-term stem markers (Lin-, CD24+, CD29hi) give rise to multilineage colonies in culture but over time these colonies lose their ability to self-renew and start to differentiate in vivo (3)

Moreover, regenerating potential is further decreased by cell differentiation which is linked to exit from the niche or stem cell compartment

The self-renewal potential of adult tissue stem cells is lower than that of embryonic stem cells (ESCs), cancer cells or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (derive from fully differentiated somatic cells reprogrammed with Oct-3/4, Sox-2, c-Myc and Kfl4). In somatic adult stem cells, self-renewal is present throughout the life of the organism but lifelong regenerative potential decreases with age and with cell division. Thus, increased stem cell proliferation caused by different agents (the deletion of CKIs, oncogenes, mTORC1 activation, Foxo3a inactivation, Sirt1 deletion in HSCs) is rapidly followed by stem cell exhaustion as demonstrated by competitive repopulation assays. The limit to cell proliferation may be dictated by the concurrent shortening of telomere length which is linked to cell division and coordinated with telomerase expression which may counteract it. In tumorigenesis, telomere shortening’s role is a double edge sword. Sensing of telomere shortening by p53 results in senescence that protects from cancer development. Through senescence, the inherent tendency of telomere shortening to reactivate telomerase or other means of telomere maintenance (ALT), a pre-requisite for cancer development, would be abolished. (4).

The cancer stem cell needs to utilize a mechanism to preserve telomere length or it would be extinguished after some replication rounds. There are differences between iPSCs, ESCs and cancer cells on the one hand and normal stem cells on the other: telomeres of tumour cells are in general shorter than those of normal cells but their length is stabilized, there is no gradual reduction of length with continuous cell division which enables self-renewal. This suggests that a sudden change in telomerase control expression occurs at the moment of transformation. This pattern of telomerase expression of the cancer stem cell is reminiscent of that of reprogrammed fully differentiated cells such as iPSCs which suggests that the cancer stem cell also originates in post-stem cells. This concept is reinforced by the common observation that cancer stem cells usually possess shorter telomeres than normal counterparts which suggests that the cell of origin engaged the differentiation pathway and started the normal process of gradual telomere length reduction undergone by all normal post-stem cells. Of note, the proportion of stem and non-stem cells within different tumour types may vary widely as observed in leukaemia. A larger fraction of the non-stem population undergoing telomere erosion would make it difficult to notice telomere stabilization although this effect might not be discerned if the progeny were separated from the CSC by only a few replication rounds or it is endowed with the mechanism of telomere length preservation of the cancer stem cell

Normal Stem Cells and Oncogenic Pathways

In culture, stem cells are difficult to maintain in the undifferentiated state. Only when they remain anchored to their niche can they be kept in an undifferentiated state. Oncogenes such as Ras can decouple cell cycle control with adhesion to the niche leading to anchorage-independent growth which is one of the earliest events in transformation (5). At the same time, signalling pathways involved in oncogenesis trigger some degree of differentiation and exit from the stem cell compartment. In addition, most oncogenes disturb normal coordination between cell proliferation and cell differentiation which may potentiate telomere shortening/damage. Concomitantly, the DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence preferentially impacts on the telomere region (6). All these facts should make committed cells preferential targets of malignant transformation. Evidently, progenitors that retain telomerase expression can be targets of malignant transformation. However, they do not retain indefinite self-renewal which must be reacquired. This must coincide with a fundamental change in telomerase reactivation marked by telomere length stabilization.

In previous studies we argued that the role of oncogenes in disturbing tissue differentiation, developmental errors and other sources of DNA damage converge on inducing telomere erosion/damage which precedes and triggers malignant transformation, The process is reminiscent of a phenomenon observed in in vitro cell cultures known as crisis where sustained telomere length reduction leads to massive apoptosis and then to the emergence of cells with an immortal phenotype. In order to simplify the discussion, we used the term telomere erosion/shortening to refer to the undoubtedly complex disturbances that telomeres and the telomere complex may undergone as different routes of tumorigenesis may impact the telomere complex in addition to shortening.

In this study, we postulate that malignant transformation entails one or several reprogramming events that reactivate telomerase expression (or ALT). This takes place in the post-stem cell stage where telomerase (or ALT) is subject to a new form of control

Regarding the assumption that the process of transformation entails cell reprogramming and the gain of self-renewal ability by a committed cell, it can be expected that the resulting cancer stem cell would exhibit a phenotype partially overlapping with that of a normal stem cell. In fact, although cancer stem cells are defined and isolated by surface markers shared with normal stem cells, they practically always express differentiation markers that allow for assignment to a particular stage of a cell lineage. A widespread survey of CSCs identified in different cancer types confirms this presumption. The case of leukemia is particularly relevant as the origin of most of them can be traced to a block in differentiation which imparts to the leukemia stem cell the phenotype corresponding to the specific stage of the developmental block. (7).

The origin of malignant transformation in a committed cell could arise after aberrant proliferation which, in the presence of gradual undermining of telomerase activity would result in gradual telomere erosion. The implication is that telomerase (or ALT) should be reactivated during tumor progression, most likely as a late event that marks the acquisition of immortality.

The alternative theory of a direct stem cell of origin implies that tumors initiate from normal stem cells that have a higher mutation burden than somatic cells (disregarding that the differentiated progeny of a stem cell carries the same mutation burden) as a result of age and have not ceased to express telomerase implying that control of telomerase would not change hands.

In former papers we highlighted multiple observations from human clinic and tumor models (8,7,9) in favour of the telomere erosion hypothesis, i.e., the origin of cancer in committed cells. Howver, let us examine the opposite hypothesis of a direct origin of cancer in stem cells.

Presumably, cancers recapitulate phenotypic features of their cell of origin. Therefore, we will focus on cancers commonly occurring in highly proliferative tissues that develop at early differentiation stages as it is expected that they will contain more numerous targets for transformation in a stem cell stage. Consistent with these population being the target for tumorigenesis, the oncogenic pathways that drive these cancers consist of those deregulated pathways that signal physiological differentiation on the same cells placing them in a progenitor rather than stem cell stage.

The Wnt Pathway and Crosstalk Between the Wnt/βcatenin and AKT/mTOR Pathways

The Wnt pathway supports the self-renewal of stem and progenitor cells and is conspicuously expressed in highly regenerating tissues. Β-catenin, the central player in this pathway, is maintained at low level by GSK3β phosphorylation in a destruction complex composed of GSK3β, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Axin, CKI kinase and β-catenin. Signaling by Wnt ligands acting on cell surface receptors of the Frizzle family inactivates GSK3β by phosphorylation at Serine 9 and blocks β-catenin destruction. This results in the accumulation of β-catenin which is then translocated to the nucleus where in conjunction with TCF factors (mainly TCF4 in the intestine) it stimulates transcription of target genes expressed physiologically in the stem cell areas and proliferative compartment of different tissue organs

There is evidence of a cross-talk between the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and the PI3-AKT-mTOR pathway which might underlie some findings that will be discussed later. GSK3β is a critical node of both pathways. On the one hand, it has been shown that GSK3β inhibition and subsequent Wnt/β-catenin activation enhances HSC self-renewal. Concomitantly, GSK3β inhibition stimulates mTORC1 which promotes proliferation and differentiation. By simultaneously stimulating the Wnt pathway (enhancing of HSC self-renewal) with inhibitors of GSK3β CHIR99021 or lithium and inhibiting the mTORC1 pathway with rapamycin, Huang et al. (10) were able to maintain long-term multilineage haematopoiesis in cytokine free cultures treated with both inhibitors. These culture conditions allowed tri-lineage hematopoietic reconstitution and gave rise to mature myeloid cells, contrary to control cells cultured in a standard cytokine cocktail. Transplantation to secondary recipients confirmed the improved preservation of HSC function as assessed by a higher chimerism detected in cells treated with both inhibitors. This implies that Wnt signaling activated in most instances through GSK3β inhibition should drive some differentiation without the artificial inhibition of mTORC1. GSK3β is also inhibited by AKT ( 11) which, in turn, requires the activity of the PI3K/AKT pathway which is antagonized by PTEN. This is why the LT-HSC exhaustion caused by deregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling is recapitulated by hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT pathway as seen after PTEN deletion. Here, we want to stress that mTORC1 activation through GSK·β inhibition associated with Wnt/β-catenin activation stimulates growth and, like c-Myc, promotes exit from the stem cell compartment. Stimulation of mTORC1 that takes place through deregulated Wnt signaling leads to engagement in cell proliferation and differentiation (exit from the stem cell compartment) which leads to stem cell exhaustion that might likely impact on telomere shortening.

Before dealing with intestinal adenoma, it is important to remember that this lesion contains progenitor cells because Myc (an essential target of Wnt/βcatenine pathway) accelerates exit from the stem cell compartment and detachment from the niche. This entails loss of stem cell regenerating potential which is crucial for tumor maintenance that consequently must be obtained from other sources. This has been demonstrated in hematopoietic tissue. Quoting from Wilson et al. “the inability to down-regulate c-Myc resulted in increased differentiation at the expense of self-renewal. C-Myc transduced cells repressed expression of N-cadherin and other cell adhesion molecules such as LFA-1 receptor and αL and β2-integrins accompanied by detachment to the niche and premature differentiation. Functionally, however, repopulation experiments showed that the repopulating ability of c-Myc transduced KLS-HSC cells was severely impaired. However, in addition to increased exit from the stem cell compartment, Myc overexpression can impair normal differentiation.” (12). Similarly, p27 helps to maintain cells in an undifferentiated stage and it has been found that Skp2-dependent degradation of p27 is crucial for progression of adenomas to carcinomas (13)

Adenoma-Carcinoma Sequence

Van de Wetering et al. have extensively characterized the Wnt/β-catenin signature in the intestine. Downstream targets include CD44, BMP4, claudin-1, ENC1 and c-MYC, c-ETS2, EPHB2. Cyclin D1, a previously published TCF-4 target was not affected by dn-TCF-4. P21 was induced independently of p53 and marks the differentiated compartment, p15, p19, p16 not expressed or unaffected Only c-MYC overrode the effect of dnTCF-4 on cell growth. It was established that c-MYC represses p21 and c-MYC and MIZ-1 were bound to p21 promoter (14)

Activating mutations of the Wnt pathway are the only known genetic alterations in early premalignant lesions in the intestine, such as aberrant crypt foci and small polyps (15, 16). In the hereditary syndrome known as hereditary polyposis as well as in more than 85% of colorectal tumors the initiating mutation is a loss of function mutation of APC and the central oncogenic player is the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and its binding to TCF molecules (mainly TCF4, in the intestine). Zhang et al. showed that hTERT is a target of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. They also reported that silencing β-catenin suppressed telomerase activity which was mediated by the suppression of TCF-4 (17).

The immediate consequence of deregulated β-catenin stimulation is the formation of a polyp or adenoma which in time may transform into a fully malignant cancer. Although the rate of conversion from adenoma to cancer is not high it is believed that most colorectal cancers arise from adenomas Therefore, this lesion provides an opportunity to study the main steps involved in conversion to malignancy.

Telomerase activity has been frequently evaluated in colorectal adenomas and its incidence has varied in different studies from 0% to 100%. However, there is ample consensus that telomerase activity increases in parallel with the size of the polyp and malignant potential. A report by Tang (18) that examined telomerase activity in 31 adenomatous polyps and 22 paired cancer-normal mucosa from nonhereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer patients found a linear correlation between polyp progression and telomerase activity. The latter was detected in 18% of normal mucosa specimens, 16% of small (<1cm) polyps, 20% of intermediate (>2cm) polyps and 71% of large polyps and 96% of adenocarcinomas suggesting that progenitors that composed the bulk of adenomas preserve telomerase expression.

A different study by Druliner (19) was aimed to determine whether telomere length and telomere maintenance mechanisms could distinguish cancer associated adenomas from those that are cancer-free. They classified adenomas into two groups: adenomas adjacent to cancer (residual adenomas contiguous with cancer) (CAP) and polyps not associated with cancer or cancer-free polyps (CFP). Further, they identified aggressive CAPs (if a stage I-II cancer recurred or presented a stage IV and aggressive CFPs (if there was a recurrence of the polyp. CAP polyps had shorter telomere length and higher telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) expression compared to CFP polyps. The degree of difference in hTERT expression between the polyps and their normal colon tissue was significant for the CAP cases but not for the CFP cases and this could not be attributed to differences in the normal tissues. The aggressive CAPs exhibited the shortest range of telomere lengths with the polyp tissue exhibiting the shortest of telomere lengths. The researchers also measured telomere lengths of peripheral blood leucocytes (PBLs) and normal colon mucosa. After adjustment for age CAP patients avereged 91.7 bp longer PBL telomere length than CFP patients; the normal colon epithelium hosted significantly longer telomeres than PBL (we suggest that this indicates a relative loss of quiescence in normal stem cells which decreases their regenerative potential and paradoxically their resistance to cancer transformation.

Plentz (20) measured telomere fluorescence intensity in consecutive histological sections stained by hematoxilin-eosin from areas of high grade dysplasia and adenoma. Signal intensity was weaker at the earliest morphologically defined stage of carcinoma-high grade dysplasia with minimally invasive growth suggesting that malignant transformation starts in the cells with the shortest telomeres.

Our interpretation of these findings is that telomere shortening proceeds within adenomas in spite of a correlative increase in telomerase activity, a feedback loop insufficient to reverse telomere attrition, probably because differentiating cells lose gradually the capacity of their precursors stem cells for telomerase expression. At some point that marks the appearance of immortalization either telomerase re-expression or ALT will take place and telomere length becomes stabilized, a mark of malignant conversion. The precedent findings suggest that gradual telomere shortening (not necessarily a definitive length reduction but some level of telomere damage) is the trigger for re-expression of telomerase or ALT and telomere length stabilization.

The signalling pathway that connects progressive telomere shortening or damage to telomerase activation (or ALT) must be different from the mechanism underlying telomerase activation in stem cells. First, in cells entering the differentiation pathway, including progenitors, telomere maintenance is impaired compared to stem cells as suggested by an increased rate of telomere shortening in intestinal adenomas compared to stem cells. This is consistent with a negative impact of exit from the stem compartment and cell differentiation in the capability of telomerase to cope with erosion of telomeres (or impaired coupling of cell proliferation with differentiation caused by oncogenes). Later, a fundamental change in telomere maintenance can explain telomere stabilization. Up until this point the increased response in telomerase activity was unable to counteract continuous telomere shortening. The two faces of this process: accelerated telomere shortening and the appearance of a new mechanism of telomerase control which is permanent and coincides with immortalization strongly suggest that immortalization is facilitated by the process of telomere shortening preceding it and that it does not occur in the stem cell compartment. Instead, it occurs in a cell engaged in tissue turnover and some degree of differentiation before developing a new mechanism for telomere maintenance distinct from that of the stem cell. Both concepts are supported by recent discoveries on telomere reactivation in cancer (to be discussed). First, telomerase expression is controlled differently in malignant versus pre-malignant cells. Second, permanent reactivation of telomerase (or ALT) inherent to cell immortalization emerges simultaneously with other stem cell features, therefore in a non-stem cell. As stated above, interference of oncogenes with cell turnover appears to be a constant finding in tumour development. In a former paper we have shown that a true stem phenotype is extremely rare in cancer (7). Even tumours that reproduce phenotypic features of cells at early stages of development display features of premature differentiation (7). In the intestine, it has been irrefutably established that colon cancer initiating cells are included in the CD133 positive population. By limiting dilution analysis, it was calculated that there was one cancer initiating cell in 263 CD133+ cells, a >200-fold enrichment over the unfractionated population. The CD133- cells did not initiate tumour growth. (21). Prominin was detected throughout the lower half of the intestinal crypt and was not restricted to the rare stem cells sandwiched between Paneth cells. CD133 can be detected in Lgr+ stem cells but also on the more numerous transit amplifying compartment. Thus, it is highly likely that colon cancer initiating cells are early committed precursors rather than stem cells

Hoffmayer (22) showed that Wnt/β-catenin signalling regulates telomerase expression in the intestinal mucosa and mouse ES cells. They have revealed binding sites in the hTERT promoter and transcription start site for different downstream targets of the Wnt/TCF pathway. The complex arrangement of distinct targets of the Wnt/TCF pathway on the hTERT promoter enables for a flexible response of telomerase expression in different contexts or to the occurrence of mutations in these promoter binding sites. This could explain differences in the control in cancer versus adenoma even when minimal changes in the promoter have occurred. Thus, when colon carcinoma cell lines carrying tetracycline inducible constructs coding for dominant negative versions of TCF1 or TCF4 were subjected to tetracycline treatment, significant downregulation of TCF targets expressed in colon carcinomas were observed but hTERT transcript levels were comparable to that of the same tumors lacking the dominant negative constructs. As Ducrest et al. state, “ “these results quite strongly argue that TCF does not play a role, direct or indirect, in controlling hTERT expression in colon carcinomas” (23). In cancer transformation telomerase re-expression is under a new, different type of control relative to normal stem cells.

New discoveries are revealing the bewildering complexity of the mechanisms used by cancer cells to support telomerase reactivation. All of them appear to be specific of cancer cells and linked to the emergence of stemness. Cancer specific hTERT transcription may be due to hTert transcription being under the control of a mutated hTERT promoter or under the control of the wild type promoter which becomes responsible to changes in nearby altered chromatin architecture.

A report from Kim et al. (24) describes a new phenomenon that they named telomere position effect over long distance (TPE-OLD) that explains how telomere length is linked to telomerase expression. In cells with long telomeres chromatin folding governs the formation of a loop placing the sub telomeric region adjacent to the Tert locus. This is associated with repression of Tert expression. Conversely, telomere looping between the hTert locus and subtelomeric 5p which exists in normal cells is greatly reduced during in vitro aging leading to abrogation of Tert repression. These researchers point out that the conception that the hTert gene is not transcribed in normal telomerase silent cells is false. Expression of splice variants takes place but it does not result in full length RNA capable of producing telomerase activity. However, the amount of transcription is higher in the cells with shortest telomeres. They also observed higher level of active telomerase in two human fibroblast strains with short telomeres compared to the same cells with long telomeres. Chromatin looping affects the expression of genes located in the vicinity of Tert locus such as the CLPTM1L gene. CLPTM1L mRNA expression is detected in normal passaged BJ human fibroblasts but its expression increased with progressive telomere erosion. Expression of genes located at intermediate distance between CLPTM1l and telomer locus did not change. Active chromatin marks H3K4me3 and H3K9 acet were found increased across the hTert promoter of aged cells with short telomeres compared with young cells with long telomeres. Same active transcription marks were detected at the promoters of nearby genes such as CLPTM1L.

All these findings suggest that telomere shortening creates permissive conditions that may not be self-sufficient for the production of active telomerase but require cooperation with other factors such as oncogenes. With this idea in mind the researchers tested the knock down of p21 (CDKN1A t) which had previously been shown to de-repress hTERT expression. This resulted in increased number of transcripts including later exons 7/8 (coding for critical residues in the reverse transcriptase domain) and exons 15/16, which are responsive for putative active hTERT and total variants respectively. These variants increased with the knockdown of p21 in old but not young BL cells but they did not detect telomerase activity. However, this suggests that more drastic alteration or further shortening of telomeres could trigger telomerase re-expression

The role played by oncogenes or (epigenetic alterations mediated by oncogenes in cooperation with genomic changes in the proximity of the telomerase promoter) in the reactivation of Tert expression is exemplified by another mechanism of Tert regulation unveiled by Akincilar et al. (25). In CRC patient samples the authors found a significant correlation of JunD and β-catenin expression and hTERT transcription. Since JunD co-localizes with CTCF to regulate chromatin compactness, the authors compared of RNA-seq-data and ATAC-seq between high JunD and low JunD CRC cells and normal colon cells which identified 10 accessible chromatin regions co-enriched with JunD and CTCF that were not present in stem cells. Removal of a distal non-coding region located 140kb upstream of the WT promoter abrogated hTERT expression which demonstrates the influence of chromatin architecture on hTERT expression. Both JunD and CTCF were required for hTERT expression only in cells containing a wild type promoter and their deletion abrogated binding of Sp1 to the WT-hTERT promoter. Afterwards, circularized chromosome conformation capture (4C) sequencing identified a ,5 kb T-INT2 region (referred to as Tert interacting region 2) that regulates expression of WT-hTERT. It was proposed that JunD-CTCF binding relaxes and bends chromatin enabling the interaction between T-INT2 and the WT-hTERT

JunD upregulation of Tert in CRC cells also requires the recruitment of epigenetic factors, including CBP/p300 which are known to unwind chromatin in conjunction with other epigenetic modifiers like CTCF and Sp-1, to form bounds between distinct chromatin regions. A significant correlation was found in CRC patient samples between JunD and β-catenin expression although knocking-down of β-catenin with siRNA reduced hTert expression in HCT116 cells but it did not affect hTert expression in HT29 cells which have low basal β-catenin levels. The INT-2 region is operative in CRC cells where hTert is activated by oncogenic alterations but was not found in normal stem cells or induced pluripotent cells where 4 factors keep the WT-hTERT promoter active. On the other hand, INT-2 does not have a role on the regulation of mutated hTert promoters which are regulated by still another mechanism involving long-range chromatin interaction

Mutations of the hTERT promoter are common in cancer with higher incidence in glioblastoma, melanoma, urothelial, bladder and thyroid cancers and tend to affect older patients. Point mutations of the Tert promoter have been identified in two key positions, C250T and C228T in 19% of cancers. In general, these are single base mutations that create binding sites for members of the ETS transcription factor family (26). Regulation of mutant promoters appear to require long-range chromatin interaction between the mutant promoter and a genomic region located 260kb upstream. This genomic region called T-INT1 contains multiple binding motifs for GA-binding protein (GABP)α/β (members of the ETS transcription family). GABPA dimers on the proximal promoter have been shown to interact with GABP dimers located in a region 260 kb upstream of the TSS site of the hTERT gene to make a stable transcriptional hub (27). The MED12 subunit of the MED complex was identified as a mediator of that interaction. The same report identified other candidate genes for similar long-range interactions that require further validation. T-INT1 appears to be implicated exclusively in the regulation of mutant Tert promoters

Complementation Between Oncogenic Pathways Suggests Parallel Changes on Reprogramming of Stemness and Telomerase Control

As previously shown, adenomas display a crypt/adenoma TCF-dependent gene expression signature. SOX4, LGR5, AXIN2, cMYC and this signature together with tumour cell proliferation is abrogated in vitro by the inhibition of TCF function through the expression of dominant-negative TCF (dnTCF4). Another signalling pathway important for colorectal carcinomas (CCs) is Hedgehog (HH)-GLI. HH-GLI has been shown to be essential for proliferation and survival of primary colorectal carcinoma cell. In this pathway, signalling is normally triggered by secreted HH ligands, most often by Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), that inactivate the 12-transmembrane protein Patched1 (PTCH1). PTCH1 activity inhibits the function of the 7-transmembrane-G-couple-receptor-like protein Smoothened (SMOH) Upon PTCH1 inactivation by HH ligands, SMOH is free to signal intracellularly, involving several kinases and leading to the activation of Gli transcription factors. Gli factors have activator and repressor functions. Gli3 3 encodes the strongest repressor. In the absence of HH ligands GliR is dominant and Gli1 is not transcribed. Upon SMOH activation, the Gli code is switched so that Gli1 is transcribed and Gl3R repressed.

In a panel of tumors directly isolated and processed from patients, Varnat et al. (28) detected the Wnt/TCF signature (LGR5, SOX4, Axin2, cMYC, CD44) in CD133+ cells from early, non-metastatic TNM1,2 CCs compared to normal colon whereas this signature was downregulated on metastatic TNM 3,4 CD133+ and CD133- cells. Instead, the latter displayed elevated expression of the HH-GLI signature. Metastatic CCs also exhibited higher levels of Wnt/TCF inhibitors DKK1 and SFRP1 than non-metastatic CCs. Inhibition of a crypt/adenoma signature by dnTCF4 did not decrease the expression of the HH-Gli1 pathway activity markers and viceversa blockade of endogenous HH-Gli1 repressed Gli1 but it did not inhibit Wnt-TCF suggesting that, in vitro, Wnt-TCF and HH-Gli act in parallel. Analysis of cell lines and primary CCs revealed that exprewession of the Wnt/TCF signature was maintained in cells cultured in vitro whereas repression of this signature and enhanced expression of the HH-GLI and core ES- like signatures were detected in vivo.

In addition, a stem cell-like signature formed by NANOG, OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and BMI1 similar to the reprogramming set involved in inducing iPS cells from differentiated cells was enriched in CD133+ versus CD133- especially when comparing metastatic with non-metastatic cases. The stem-like signature was dependent on the HH-GLI pathway but unaffected by blockade of endogenous Wnt/TCF signaling by dnTCF4.

The finding that β-catenin induced GLI1 activity in a GLI-binding site luciferase reporter assay independent of TCF function suggested a crosstalk between these pathways. KRASv12G, MEK and AKT also enhanced GLI activity on GLI-luciferase reporter assays. Exogenous Gli activity was also repressed by PTen and p53. Interestingly, MEK and AKT inhibitors repressed the epithelial-mesenchymal marker SNAIL1 only in metastatic CCs. On the other hand, β-catenin has been found to upregulate sonic hedhog (Shh) and Patched (PTCH1) as well as IGF signaling on the hair follicle (29).

Repression of the Wnt-TCF crypt/adenoma signature in patient samples and in xenografts versus in vitro culture indicated the possibility that Wnt-TCF signalling might be replaced by other signalling pathways during tumour progression ending in further reprogramming (immortalization emerging in cells within the same population through a secondary oncogenic pathway?).They made use of the two established CC cell lines previously used to demonstrate the key role of TCF function in vitro: Ls174T-dnTCFdox and DLD1-dnTCFdox. These clones display homogeneous dnTCF4 expression only upon doxycycline addition. Ls174T-dnTCFdox transplanted in vivo displayed TCF target inhibition to the same level as in vitro as compared with untreated cell controls but this did not have an impact on tumour growth: tumours resulting from Ls 174T-dnTCF4dox cells or parental Ls174T cells with or without dox treatment showed similar growth curves and tumour appearance. However, the same level of inhibition in vitro leads to complete growth arrest. This lack of tumour growth arrest in spite of inhibition of several targets of Wnt-TCF parallels results commented above (23) and suggests a critical change in tumour growth control probably associated with a separate control of telomerase expression. However, results with DLD1-dnTCF4dox were different. Treatment with dox repressed TCF targets as well as tumour growth both in vivo and in vitro. (telomerase expression control had not changed hands yet?)(28).

Further research suggests again that on the course of cancer progression the initial oncogenic pathways may intersect or overlap with new cancer-driving pathways. This process might entail a secondary event of reprogramming within an established cancer stem cell or within another cell from the tumour population. Findings by Asciutti et al. (30) again show the superimposition of distinct oncogenic pathways on carcinogenesis initiated by the Wnt/TCF pathway. They studied three gastric carcinomas: AGS that harbours a β-catenin activating mutation that prevents its proteasome degradation and MKN-28 and MKN-74, both containing inactivating mutations of APC. Downregulation of TCF signalling by dominant negative TCF4 (dnTCF4) led to reduced expression of TCF targets including c-Myc, BMP-4, Axin-2 and Lef-1 in all three tumours as well as inhibition of tumour cell proliferation in AGS. No inhibition of proliferation was observed in the other two cell lines in spite of a comparable response to dnTCF4 regarding downregulation of TCF targets including c-Myc inhibition and correlated increase in p21 level. Following overnight serum starvation ERK and AKT phosphorylation were detected in AGS and MKN-28 tumour lines while MKN-78 showed minimal if any AKT phosphorylation and very low ERK activation. AGS tumour growth could be inhibited by either dnTCF4 or c-Myc shRNA while neither of them affected MKN-28 tumour growth. Exposure to a MEK inhibitor or aPI3K inhibitor led to a marked inhibition of proliferation of MKN-28 tumour and slight reduction of AGS proliferation

The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Appears to Entail a Secondary Stemness Reprograming Event and a New Change in the Control of Telomerase Reactivation

Superimposition of secondary oncogenic pathways during tumour progression goes hand and hand with some ominous signs such as invasion and metastasis. The onset of metastasis, is usually preceded by invasion of tumour cells into the surrounding soft tissues. The capacity for invasion is rooted on a physiological mechanism used during embryogenesis for tissue remodelling and amply used later in life by cancer cells, called epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). A study by Medici et al. (31) on colon cancer and melanoma cell lines shows an intricate cooperation between the Wnt and TGF-β pathways in the establishment of EMT. Initially, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 induction of Snail and Slug resulted in decreased level of E-cadherin with subsequent release of cytosolic β-catenin. Then, β-catenin-TCF4 upregulated TGF-β3 which promoted synthesis of LEF-1. As Snail and Slug are transcriptor repressors, their induction of TGFβ3 is indirect and mediated by β-catenin-TCF4 binding to the TGF-β3 promoter.

Loss of E-cadherin was accompanied by morphological changes characteristic of EMT. However, DN-LEF-1 prevented invasion associated with EMT.EMT Enhanced transcription of TGFβ3 results in upregulation of LEF-1 which after binding cytoplasmic β-catenin can enforce the acquisition of the mesenchymal phenotype and gene changes associated with EMT: increased vimentin, fibronectin, α-SMA and α-actinin expression.

The authors indicated the possible involvement of the MAPK pathway on the TGFβ1/2 upregulation of E-cadherin repressors Snail and Slug. As well as the possible role played in this and related processes by GSK3β, an important node in the bifurcation of this and other signalling pathways. TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 all signal through PI3K (and downstream target AKT) which induces phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β, thereby releasing β-catenin from its destruction complex and creating a surplus of β-catenin which can associate with LEF-1 that was upregulated by TGFβ3 signalling.

The report by Medici et al. does not address the emergence of stem cell traits or the potential role of telomerase in EMT. This was addressed in a model of gastric cancer by Liu et al. (32)). Wnt-TCF supports self-renewal of gastric mucosa and its deregulation can initiate gastric cancer but EMT, appears to require, in addition, the participation of hTERT as well as the other factors described above. Liu et al. infected the GC cell line BGC-823 (and two more gastric cancer cell lines) with an hTERT retroviral vector and detected increased levels of mesenchymal markers vimentin and Snail and a reduction of E-cadherin. This led also to a significantly increased invasiveness of hTERT-BGC-823 cells compared with control pBabe-BGC-823 cells. Conversely, hTERT inhibition resulted in loss of these mesenchymal markers and diminished invasiveness. hTERT inhibition by siRNA substantially abolished TGFβ1-stimulated Snail and vimentin induction and conversely, hTERT overexpressing cells exhibited much higher levels of Snail and vimentin than control cells. hTERT and TGFβ1 affected β-catenin expression with overexpression of these factors leading to higher β-catenin levels and their inhibition correlating with slight but consistent reduction of β-catenin. In BGC-823 cells transfected with a dominant negative hTERT (mutation D869A) that loses a catalytic function or with C-terminal tagged hTERT that exhibits telomerase activity but is unable to elongate telomeres, increased expression of Snail and vimentin and activation of TCF/LEF reporter were detected.

After injection of hTERT-BGC-823 cells or of pBabe-BGC-823 control cells into the tail vein of nude mice, metastatic colonies were found in the lungs in both cases but those formed by hTERT-BGC-823 were larger and more numerous. hTERT-induced EMT was accompanied by the appearance of stem cell features such as dramatic enhancement of monosphere formation and overexpression of stem cell markers like OCT-4 and CD44, an established gastric CSC marker.

(32). These findings and the aforementioned study of Varnat et al. suggest the need for the simultaneous occurrence of reprogramming (as shown by the onset of stem cell traits) and inducers of EMT such as Snail and vimentin

Upregulation of TGF-β1-mediated upregulation of β-catenin by hTERT and the synergistic effect of TGF-β1 and hTERT in EMT induction demonstrates a positive feedback loop between these factors which may accelerate induction of EMT and acquisition of stemness traits. It is also possible that during cancer progression, interaction of hTERT with new partners leading to increased expression of hTERT, might induce further reprogramming events that could accelerate and worsen the course of the disease

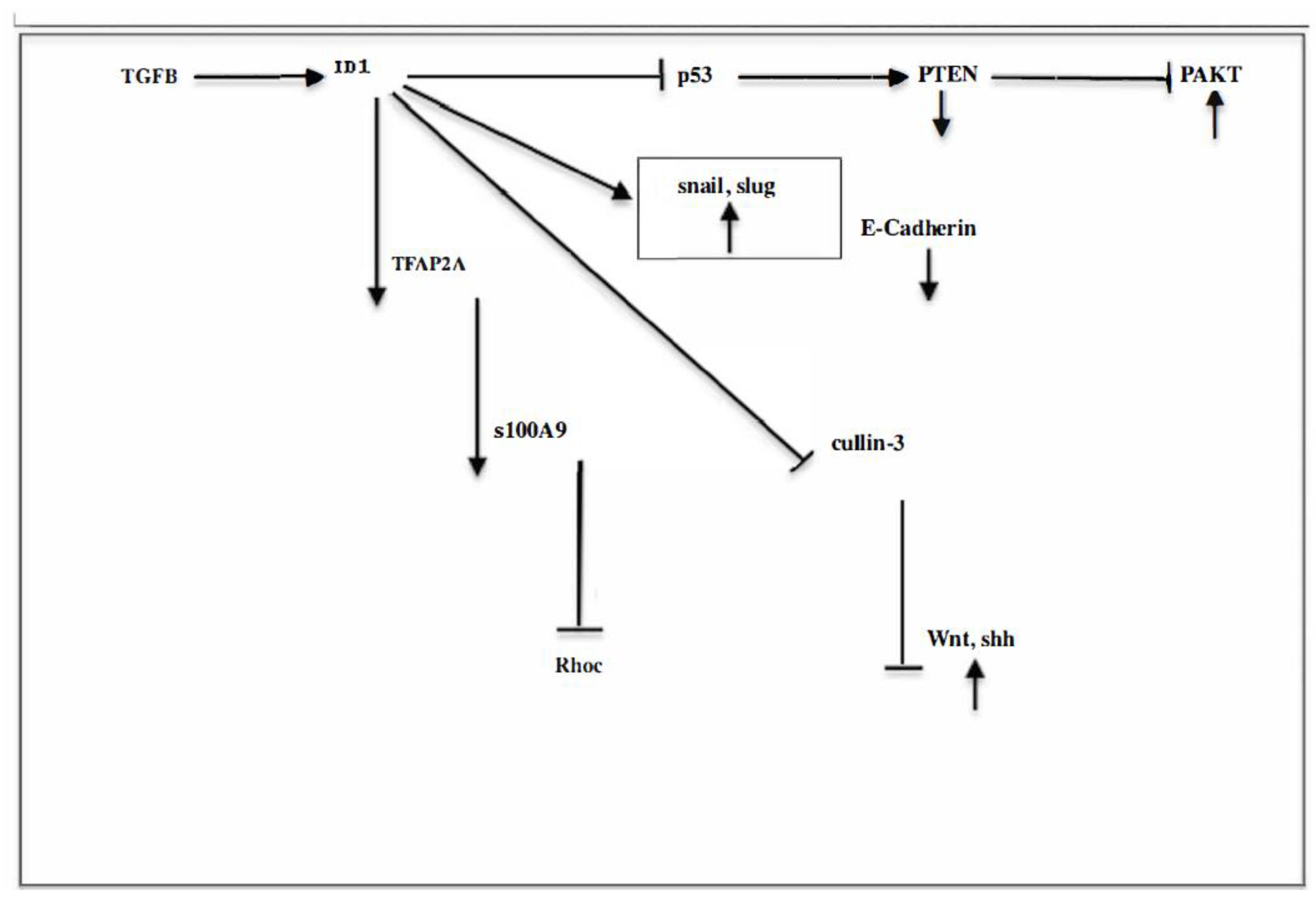

Id1 and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition.

Ids are members of the helix-loop-helix (HLH) group of proteins which can form heterodimers with basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins. Lacking the basic domain necessary for DNA binding, Ids act as dominant negative transcription factors. In hematopoiesis Id1 preserves the undifferentiated state by antagonizing a differentiation step induced by E2A. Id1 null readily commit to myeloid differentiation consistent with de-repression of E2A as inducer of myeloid lineage (33) When bone marrow cells were transduced with an Id1 expressing MSCV retrovirus cells could divide for over 1 year in the presence of stem cell factor. Most cells were myeloblasts with some promyelocytes and myelocytes; these cells could be induced to differentiate with physiological inducers of differentiation. Transplantation of cultured cells to mice induced a myeloproliferative like-disease. However, secondary recipients did not develop leukaemia (7) suggesting that prevention of differentiation by Id1 does not induce transformation

The landscape afforded by in vivo experiments is somewhat different. One of the in vivo studies on Id1 took advantage of a murine mammary epithelial cell line, SCp2, wich can differentiate in vitro recapitulating the main aspects of development and lactation including proliferation and invasion of mammary during late pregnancy as reflected by growth arrest and formation of alveolar structures as well as milk proteins when serum is removed and cells are placed in contact with basement membrane components and given lactogenic hormones (insulin, prolactin and hydrocortisone) Upon constitutive Id1 expression these cells slowly invade the basement membrane and express a 120kd metalloproteinase (MMP) mimicking the capacity of normal mammary cells to secrete MMPs that degrade the ECM during involution. However, despite constitutive Id1 expression SCp2 cells do not grow in soft agar nor form tumors in nude mice. SCp2 cells transfected with the murine Id-1 cDNA driven by the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter (Cp2-Id-1 cells) formed alveolar structures but later (10 days) detached and migrated through the surrounding parenchyma. Among nine human breast tumors examined, only Id-1 expressing cells also expressed the 120-kDa gelatinase. A complete epithelial-mesenchymal transition was not observed as they still retained some epithelial markers. (34)

Expression of activated Ras in mammary epithelium of mice leads to formation of senescent foci containing disorganized epithelial cells. Mice that concurrently harbor deletion of the p19, p53 or p21 tumor suppressor develop rapidly mammary tumors suggesting that these tumor suppressors prevent tumorigenesis by inducing senescence. However, ectopic expression of Id1 co-expressed with activated Ras leads to rapid tumor development which indicates the capacity of Id1 to antagonize apoptosis induced by the tumor suppressor axis p19, p53, p21. In the same study conditional activation of hrasv12 in conjunction with constitutional activation of Id1 led to tumor formation but doxycycline inactivation of the hrasv12 promoter resulted in complete tumor regression within 40 days. This again suggests that Id1 alone, even if constitutively expressed cannot give rise to tumor development. It is true, however, as the same study informs, that overexpression of Id1 in the intestine leads to development of adenomas albeit with long latency and low penetrance. To our knowledge, there is only an example of tumor (leukemia) induced by Id1 alone. Its overexpression in the hematopoietic compartment leads to massive apoptosis, disruption of differentiation and leukemia (35). The finding of massive apoptosis induced by Id1 is surprising as it seems to contradict the anti-apoptotic function usually performed by Id1. The transgenic expression of Id1 in thymocytes was found to change the normal distribution of the thymocyte population at the DN and later stages in a way that is highly compatible with a hematopoietic developmental block, a situation which is a frequent cause of leukemia which suggests a totally different mechanism of tumorigenesis that must be imputed to the developmental block. (36).

In summary, Id1 does not meet the classical definition of an oncogene. No Id1 mutatios have been found although numerous reports have linked Id1 to induction of invasion and metastasis in human cancer through promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Two characteristic features of epithelial cells undergoing EMT are the adoption of a mesenchymal morphology and simultaneous expression of stem cell properties. This fact demonstrates the possibility of spontaneous reprogramming of committed cells to neoplastic stem cells. However, most information on EMT has been obtained with models involving ectopic expression of Id1 in immortalized cell lines although occasionally have involved committed cells. The main final downstream effectors of Id1 in EMT include negative regulators of E-cadherin such as Snail, Twist, fibronectin and vimentin, although various additional targets participate in this process in distinct tissues. Some examples follow

Breast

Mani et al. induced EMT by ectopic expression of Snail or Twist in cells isolated from non-tumorigenic, immortalized mammary epithelial cells (HMLE) sorted into enriched mammary stem cells (CD44hi CD24lo and committed CD44lo CD24hi. The mesenchymal-like cells generated by EMT acquired a CD44hi CD24lo expression pattern-precisely the same phenotype that has been ascribed to neoplastic mammary stem cells. Similarly, induction of an EMT in HMLEs by exposure to TGF-β1 (an inducer of Id-1) resulted in the appearance of mesenchymal-looking cells and the acquisition of the CD44hi CD24lo phenotype. (37). In the words of these authors: “In principle, the behaviour of the HMLE human mammary epithelial cells might be attributable to the introduced genes that were used previously to immortalize these cells, specifically hTERT, which encodes the catalytic subunit of human telomerase holoenzyme, as well as the SV40 early region. For example, these genes might facilitate the reprogramming of the HMLE cells initiated by EMT-inducing transcription factors such as Snail or Twist. However, we observe exact the same responses to Snail or Twist in non-immortalized primary mammary epithelial cells, which indicates that hTERT and SV40 antigens appear to have no effect on the induction of the EMT. In summary, the experiments indicate that committed cells are reprogrammed to stem cells when subjected to EMT.

Other experiments have revealed the wide diversity of downstream targets that may be involved in Id1-induced EMT. Gumireddy et al. (38) working also with breast cancer cell lines and clinical samples showed that Id1 interacts with TFAP2A which binds to the S100A9 promoter enhancing its activity. A consequence of this activation is suppression of RhoC. Therefore, Id1 by binding TFAP2A downregulates RhoC. RhoC appeared to be the main responsible for invasion and metastasis of breast cancer and its downregulation suppressed the migratory and invasive phenotype induced by Id1.

However, different experiments have incriminated the PI3K/AKT pathway as the backbone of EMT. Thus, In breast cell line MCF7 Lee et al. (39) showed that Id-1 activated the Akt pathway by inhibition of PTEN transcription through downregulation of p53. Akt was phosphorylated at Ser473 and glycogen synthase kinase at Ser9 with stabilization and nuclear localization of β-catenin, TCF/LEF, cyclin D1 and Akt-mediated p27 phosphorylation at Thr157 and translocation to cytoplasm. Fong et al. reported that Infection of a non-invasive breast cancer cell line with Id-1 rendered it invasive (40).

A study in lung cancer confirmed that induction of Id1 was mainly mediated by Akt activation. Id1-overexpressing H460 lung cancer cells had elevated expression of cyclin D1 and CDK4 as well as a decreased expression of CDK2, cdc2 and cyclin B1. The expression of phospho-p38MAPK (active form of p38MAPK) was increased in Id1-overexpressing H460 cells and repressed in Id1- knockdown H520 cells. However, when Id1-overexpressing H460 cells were treated with SB203580, an inhibitor of p38MAPK, or wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3K/Akt, they found that only wortmannin had a significant effect on suppressing cell proliferation indicating that Akt was the main effector of Id1 expression. JNK, ERK and STAT3 activities were also analysed (41). Activation induced by Id-1 may extend a step further along the PI3K pathway affecting also the NFκB expression. Li (42) showed that in esophageal cancer cells, stable ectopic expression of Id-1 induced expression of pAKT, glycogen synthase kinase 3β and inhibitor of kappa B, as well as increased nuclear translocation of NFkB subunit p65 and NFkB binding activity. These effects were antagonized by treatment with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. This experiment revealed the involvement of another downstream target of the pathway, NFκB which appears to be responsible for the apoptosis protection of cancer cells. Both, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or the NFkB inhibitor Bay 11-7082 increased the sensitivity of Id1 overexpressing esophageal cancer cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis

The same conclusion can be derived from another study in prostate cancer cells. Id-1 induced nuclear translocation of NFκB along with upregulation of its downstream targets Bcl-xL and ICAM-1 which was accompanied by increased resistance to apoptosis induced by TNFα through inactivation of Bax and caspase 3 (43)

Liver

Direct origin of cancer from primary hepatocytes has been described associated or preceding EMT.. Cirrhotic livers provide a fertile soil for cancer development and some observations implicate fibroblastoid cells derived from hepatocytes as the cells of origin of hepatocarcinoma. TGF-β which is increased in chronic inflammation of the liver can promote this phenotypic change. Primary mouse hepatocytes have been observed to lose their epithelial phenotype in response to TGF-β accompanied by loss of E-cadherin and upregulation of Snail. EMT in the liver appears to be a complex process requiring inputs from several signaling pathways. In primary murine hepatocytes, EMT was associated to focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-Src-dependent activation of the PI3K/Akt and Erk1/2 pathways. On the other hand, EMT appears to be associated in human hepatocarcinoma with metastatic and highly invasive tumors. E-cadherin was reported to be strongly expressed at cell-to-cell contact in a group of non-metastatic HCC patients. Instead, reduced expression of E-cadherin and loss of cell-to-cell contact associates with nuclear translocation of β-catenin and predominates in the group of HCC patients with metastasis (44).

In cervical cancer the T-box transcription factor 3 (TBX3) promotes EMT and its expression correlates with Id1 mRNA and protein levels although it has not yet been confirmed whether TBX3 regulates Id1 directly. Silencing TBX3 reduced cell migration and invasion. However, TBX3 might act also through its ability to downregulate PTEN and suppression of p19-p53 pathway (45). In another study on cervical cancer, Id1-induced activation of the PI3K pathway could be followed, at least, to downstream target NFkBp65 (46).

Caveolin-1 is essential for the role of Id-1 in inducing EMT and cell survival in prostate cancer cells. Apparently, each Id1 and caveolin alone can induce EMT but they have a synergistic effect. In prostate cells, Id1 induced Akt (mediator of PI3K pathway) activation through promoting the binding between Cav-1 and PP2A. Cav-1 regulates signalling of membrane proteins such as epidermal growth factor receptor, Src and H-ras through direct physical interaction. Although Id1 and Cav-1 alone are each able to increase Akt phosphorylation they can act synergistically. Id1 promotes the inhibitory effect of Cav1 on PP2A but this does not result in lowering PP2A level. Id1 does not bind PP2A. Thus, it seems that Id1 promotes the binding activity between Cav-1 and PP2A which may lead to suppression of PP2A activity (47)

Glioblastoma

As first described in breast cancer, in glioblastoma, TGF-b has been shown to increase the CD44high cell population enriched for CICs through the induction of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The CD44high/Id1high population was enriched for GICs and generated tumors reproducing the heterogeneous cell population of the original tumor (48). Other experiments in non-transformed p16-p19 deficient astrocytes have revealed how the context can influence backbone signaling pathways Id1- mediated suppression of Cullin3 conferred stem cell like features and tumorigenicity to Ink4a/Arf-/- astrocytes. The authors identified GLI2 and DVL2 as Cullin3 interacting proteins which are involved in the SHH and Wnt pathways respectively and demonstrated that ID1-mediated suppression of Cullin3 may activate SHH and Wnt signaling by stabilizing GLI2 and DVL2 proteins, respectively. Id1 overexpression markedly increased DVL2 and GLI2 protein stability relative to VEC and ID1+Cullin3 overexpressing cells. However, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that Dvl2 and Gli2 mRNA levels were not significantly changed by ID1 overexpression which indicate that ID1 regulates DVL2 and GLI2 expression at a post-transcriptional level by suppressing Cullin3 expression (49). We will see again this phenomenon in tumorigenesis: the initial extracellular inducers of a tumorigenic signaling pathway cease to be necessary for stimulation of the pathway which becomes autonomous, that is, dependent only in the intracellular donstream targets.

Superimposition of the Wnt and Shh signaling pathways has also been demonstrated in the colon cancer line HCT116. Id1 maintained the stemness of CRC cells through activating the Wnt and Shh signaling pathways Combined inhibition of Wnt pathway with FH535 and Shh with HPI-1 showed greater inhibition than each single inhibitor. Concomitantly, there was significant reduced c-myc expression and c-myc downstream target PLAC8. Taken together, these data demonstrate that Id1 maintains the stemness of CRC cells via the Id1-c-Myc-PLAC8 axis through activating the Wnt/β-catenin and Shh signaling pathways (50).

A few reports have uncovered the participation of EGFR and MAPK in Id1 expression. In non-small-cell lung (NSCL) cancer, Pillai et al. (51) reported that signaling through the nicotine acetylcoline receptor or the EGF receptor upregulated Id1 in an Scr-dependent manner. Nicotine induced the expression of mesenchymal markers fibronectin and vimentin by downregulation of ZBP-89, a zinc finger repressor protein. Ectopic expression of a mutant Ras also resulted in increased Id1 level.

Despite the above reports, it is important to emphasize that EMT occurs as a physiological phenomenon in wound healing. In the early phase of wound healing EMT takes place as demonstrated by a change in keratinocyte morphology that shift to that of interstitial cells with the capacity to migrate and the typical molecular expression pattern of EMT: downregulation of E-cadherin and overexpression of vimentin and N-cadherin. This molecular expression pattern was amplified in the keratinocyte cell line HaCat by addition of TGF-β1. In addition, exogenous TGF-β1 accelerated cutaneous wound healing. It was shown that Foxo3a could revert these changes. Overexpression of Foxo3a suppressed the TGF-β1-induced EMT and the associated β-catenin activation. This key molecule of the Wnt pathway, β-catenin, was increased in cytoplasm and nucleus of HaCat cells by silencing Foxo3a expression and, conversely, the expression of β-catenin was decreased when infecting HaCat cells with lenti-flag- Foxo3a (52). Here a new player, FOXO, enters the game. There are reports showing that Foxo3a can suppress EMT in prostate cancer cells through inhibition of Wnt pathway. Foxo3a inhibits β-catenin both through direct binding and induction of miR-34 expression. β-catenin was shown to participate in Foxo3a-mediated suppression of EMT. In fact, decreased-E-cadherin and increased N-cadherin and fibronectin levels induced by Foxo3a KD and other features of EMT were reversed by silencing β-catenin expression (53). Another member of the Foxo family, FOXC1, has been shown to control stem cells of basal-like breast cancer via non-canonical activation of smoothened-independent Hedgehog signaling (54).

Evidently, EMT is a very complex process about which we have only fragmentary data, as illustrated in

Figure 1

The above observations paint a picture of the crucial role of the crosstalk between the PI3K and Wnt/Shh oncogenic pathways. Some of the reports gathered have described activation of a downstream, converging molecule of these and other pathways, NF-kB, which is found to be involved in stemness and invasiveness. On the other hand, the common occurrence of stemness could be explained if oncogenic signaling extends to other downstream targets of the PI3K pathway such as the FOXO family and specially, Foxo3a, which are known to regulate stemness.

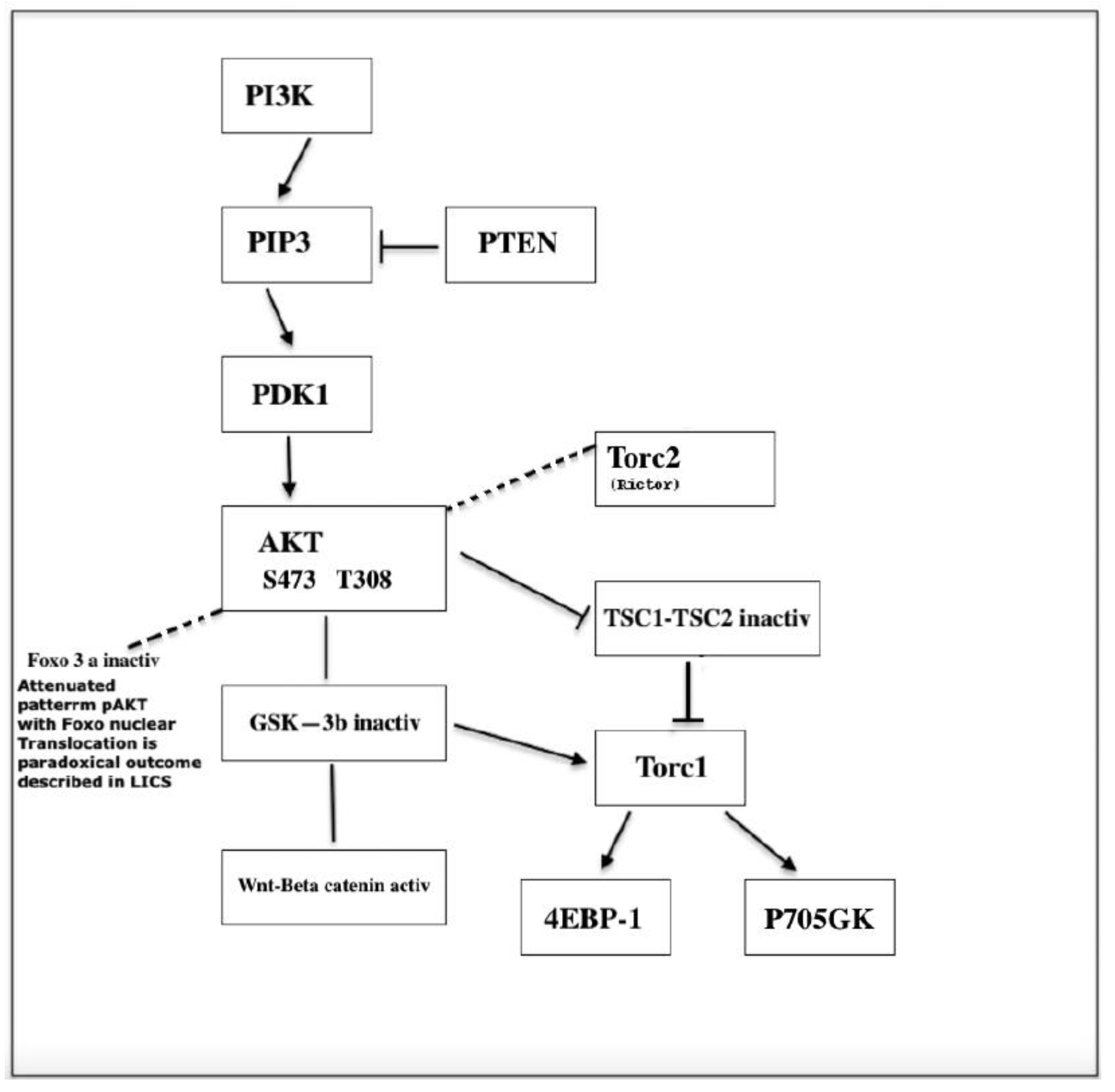

FOXOs and NF-kB Interplay (Figure 2)

The Forkhead box transcription factors family consist of 19 subclasses of Fox genes. They are involved in stemness, cell survival, redox homeostasis and stress resistance. In the absence of growth factor or insulin stimulation, Foxos reside in the nucleus where they activate transcription of cell cycle inhibitors such as p130, p27, p57 and p21 as well as proapptotic genes such as TRAIL, FasL and Bim. Foxo inactivation by PI3K/AKT signaling leads to its nuclear exclusion with enhanced cell proliferation, survival and stress sensitivity. (55). Loss of Foxo in the hematopoietic compartment results in an increase in HSC in cycle accompanied by exit of CD34- LSK cells and concomitant decreased p27 and p57. Stem cell quiescence depends on these cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs). Ablation of CKIs leads to stem cell exhaustion (56). The transition from HSC to myeloid progenitos is accompanied by a 100-fold increase in ROS. This change appears to be regulated by a transcription program that is independent of Foxo. The high ROS level wich is appropriate for the functions of short- lived myeloid cells would be incompatible with HSC homeostasis. (57). Akt is the main kinase that regulates Foxos (Figure 2) although other kinases such as glucocorticoid inducible kinase (SGK), casein kinase (CK1), dual thyrosine phosphorylated regulated kinase 1 (DYRK1) and IKK may phosphorylate Foxos in specific residues and target many other protein substrates including GSK3β, p21 and p27. Phosphorylation of Foxos by JNK appears to be counterregulatory with respect to Akt (57, 58)

Figure 2.

P13K/ AKT signaling.

Figure 2.

P13K/ AKT signaling.

Studies on the role of PI3K pathway in tumorigenesis have revealed two apparently reversible functions of FOXOs associated with the activation and inactivation of AKT. Inactivation of Foxo3a which is always accompanied by cytoplasmic translocation of Foxo3a results in cell proliferation-differentiation. However, despite AKT signaling some cells show nuclear localization of Foxo3a and a pattern of attenuated AKT ( Figure 2). This reverse nuclear translocation opposite to the expected cytoplasmic translocation normally induced by phosphorylated AKT appears to be essential for the emergence of the cancer stem cell and maintenance of leukemia initiating cells whereas suppression of Foxo3a appears essential to maintain survival and proliferation. This double shutling of Foxo3a is observed in AML-AF9 leukemia where LICs have the GMP phenotype but contrary to the bulk tumor cells display an attenuated pattern of AKT activation. Sykes et al. ( 58) activated AKT in HSCs by Pten deletion or myr-AKT constructs transduced to bone marrow cells using the stem cell virus MSCV. Invariably, Pten deletion leads to HSC mobilization and HSC exhaustion followed by tumorigenesis.BM cells transduced with activated AKT (MSCV-IRES-GFP-myr construct) when injected to irradiated syngeneic recipients induce a myeloproliferative disease (MPD) that progresses to either AML or ALL. Despite the MPD, the proportion of GFP+ LSK cells were decreased compared to control, consistent with HSC mobilization and exhaustion of the HSC compartment. Paradoxically, Sykes et al. found that the same AKT construct induced suppression of growth of AML-AF9 leukemia. Suppression of growth was associated with myeloid maturation and myeloid maturation related cell death. Pten deletion, activates AKT and induce self-renewal and exhaustion of HSCs (likely accompanied by exit of the HSC compartment). In the AML-AF9 leukemia model, the expression of phosphorylated AKT followed by HSC exhaustion was accompanied by a conspicuous increased myeloid maturation and myeloid maturation related cell death (myeloid marker CD11b was higher on bone marrow cells injected with the stem cell virus MSCV (MSCV.IRES-GFP-myr-Akt). However, maturation related death induced by myr-Akt occurred in the presence of rapamycin, suggesting that Akt utilizes pathways other than mTOR for activation for myeloid maturation. (58). In fact, Foxo3a inactivation induces cell proliferation and differentiation of HSPCs as well as exhaustion of HSC as revealed in competitive repopulation assays. This has been observed in other tissue stem cells, in addition to HSCs. For instance, Foxo1 and Foxo 3 knockdown led to differentiation of intestinal stem cells into goblet cells and Paneth cells. Foxo 3 is higher in neural stem cells (NSCs) undergoing self-renewal and its ablation led to a decrease in NSC population accompanied by an increase in progenitors and the exhaustion of the NSC pool. (56). A parallelism on the effects of different targets of the PI3K pathway is well known, but a subtle difference may be revealed here: pAKT phosphorylates and inactivates different substrates such as TSC2 and GSK3-β. Interestingly, pAkt Ser473 is dispensable for TSC2 (which activates mTORC1) or GSK3-β inactivation but is required for Foxo3a inactivation (Figure 2). Thus, myeloid maturation and cell death might be attributed to the action of Foxo3a inactivation.. Apparently, growth inhibition in this system must be attributed entirely to maturation related cell death since pAKT only reduces tumor burden and induces apoptosis of the bulk of tumor cells but it does not affect the leukemia initiating cells (LICs). However, in the AML-AF9 leukemia LICs have the phenotype of GMPs but differ from GMPs by a pattern of attenuated Akt activity (reduced pAktThr308 and reduced pAkt Ser473) which is identical to that of normal HSCs and which seems essential to maintenance of self-renewal. In summary, AKT activation induced by MSCV virus improved leukemia by reducing tumor burden but did not have any effect on the AkT inactive stem cell. Since HSCs were pushed into cycle and engaged turnover by Foxo3a inactivation, the attenuated pattern of AKT expression which protects stem cells from exhaustion must have been gained after cells have been pushed out of the HSC stage by Foxo inactivation as indicates the GMP phenotype. The reversal to the AKT pattern associated to active Foxo3a must be concomitant with the triggering of immortalization and cancer transformation through unknown signaling. JNK was shown to be activated in response to Foxo deactivation but its activation resulted in further increased maturation related apoptosis. (58)

Assuming a process of tumorigenesis that involves Foxo deactivation (downstream target of PI3K pathway), which leads to differentiation, the emergence of the LIC after Akt-induced-Foxo inactivation implies an event of de-differentiation-reprogramming occurring in a cell previously engaged in pAkt-induced proliferation-differentiation. For instance, nuclear exclusion (inactivation) of Foxo3a is associated with the first step of hematopoietic differentiation as Foxo3a is present in the nucleus of freshly isolated Foxo3a+/+CD34- KSL cells (HSCs) but appears in the cytoplasm of freshly isolated Foxo3a+/+ CD34+ KSL cells (progenitors). Our proposal is that malignant transformation of a committed cell might be supported by a mechanism of telomerase reactivation more similar to that of iPSCs (triggered in a differentiated cell) rather than the telomere maintenance mechanism of the normal stem cell which is probably exhausted. Some Foxo family members such as FOXF2 can regulate stemness differentially in basal and luminal-like breast cells (59).

A previous report validated these findings and unveiled new aspects of the issue (60). BCR-ABL activates Akt signaling that suppress FOXO transcription factors, chiefly among them, in the hematopoietic system, Foxo3a. It was shown that Foxo3a has an essential role in the maintenance of CML LICs. Nuclear localization of Foxo3a and decreased Akt phosphorylation are enriched in the LIC population and as observed by Sykes et al. in the AML-AF9 model, low Akt phosphorylation in LICs correlated with mTORC1 inactivation. In order to prove the role of Foxo3a in the maintenance of LICs Naka et al. infected immature bone marrow cells from Foxo3a+/+ and Foxo3a-/- mice with a retrovirus carrying MSCV-BCR-ABL-IRES-GFP. The infected cells were transplanted into syngeneic recipients. Both recipient groups developed CML-like MPD demonstrating that FOXO3a is dispensable for the generation of CML-like disease. However, the in vitro colony forming ability of second BMT LICs was decreased by loss of Foxo3a. In a third BMT, mild CML-like disease developed in recipients within one month but Foxo3a deficiency prevented the propagation of CML cells in the peripheral blood and spleen. Foxo 3a+LICs also developed ALL as well as CML which was not observed in recipients of Foxo3a-. Thus, Foxo3a is essential for long-term maintenance of leukemia initiating potential whereas Foxo3a inactivation is a previous step in the initiation of leukemia. An important additional finding was that TGF-β1 signaling controls Akt activation in the nucleus of KLS+ cells but not in nucleus of KLS- (non-LICs) as indicated by phosphorylation of Smad2/3 restricted to nuclei of KLS+ cells. In view of the discussion in precedent paragraphs on the role of TGFβ on epithelial-mesenchymal transition, this finding raises the question of the involvement of EMT in these leukemia models. Moreover, the role of telomerase re-expression must be investigated as suggested by the report mentioned above by Liu et al. (32) where hTERT inhibition by siRNA substantially abolished TGFβ1-stimulated Snail and vimentin induction and conversely, hTERT overexpressing cells exhibited much higher levels of Snail and vimentin than control cells. Other outcomes of Foxo inactivation which are not usually contemplated may assist on the promotion of tumorigenesis such as the non-physiological type of myeloid differentiation induced by Foxo deactivation (57) as interference with hematopoiesis might by itself be a cause of tumor formation as numerous examples of hematopoietic developmental blocks indicate.

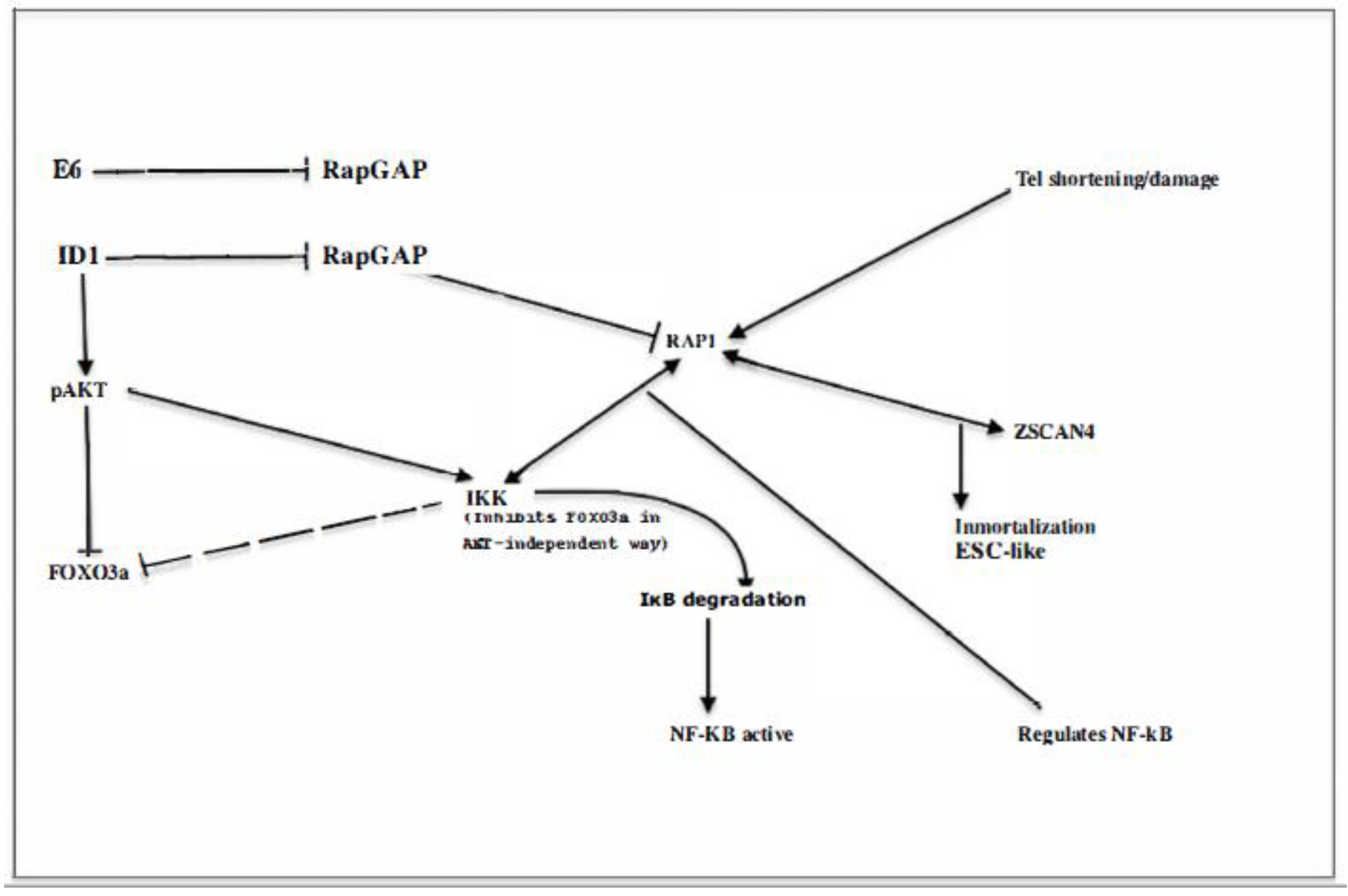

IκB Kinase (IKK

β, or IKK

α to a lesser degree) may induce inactivation and cytoplasmic translocation of Foxo3a independent of pAKT at Ser 644

(61) (Figure 3) and both pAKT or IKK-induced nuclear inactivation of Foxo3a promotes cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Therefore, it is believed that these molecular changes have an important role in the promotion of tumorigenesis. However, deepening the puzzle, the correlation between positive pAKT and IKK and cytoplasmic localization of Foxo3a may occur in normal tissues as well as in tumors

(62). Nevertheless

, the contribution of Foxo3a to leukemic transformation is indisputable as demonstrated by impaired leukemogenesis in Rictor-deleted mice

(7) that cannot phosphorylate Akt Ser473 as illustrated in

Figure 2 and are, therefore, unable to inactivate Foxo, suggesting Foxo`s role in tumorigenesis requires both inactivation in the initial phase within progenitors and its activation in LICs

The NF-κB Transcription Factors and Oncogenesis.

The NF-kB family of transcription factors plays a pivotal role in a multitude of process such as inflammation, cell proliferation, survival, adaptive and innate immunity, EMT and stemness Here we will discuss its role in cancer as one of the final downstream targets of the PI3K pathway

The NF-κB family consists of five members: RelA/p65, RelB, c-Rel, NFκB1/p50 and NF-κB2/p52. P50 and p52 lack a transcactivation domain and are generated by processing from p105 and p100 respectively

NF-κB signaling is primary enacted by the IKK complex (IkKα, IKKβ and IKKγ/Nemo) which phosphorylates inactive IκB proteins located in the cytosol resulting in the nuclear translocation of NF-κB factors and the release and degradation of IκB proteins (Figure 3). Signal transmission to NF-kB transcription targets is channelled according to two different routes designated as the canonical and the alternate pathways.

In the canonical pathway, IKKβ subunit directly phosphorylates NF-kB-associated IκBα (mainly the p50/p65/RelA which is the most abundant dimer) leading to IκBα degradation and p50 /p65 translocation to the nucleus where it regulates transcription of target genes.

The alternate pathway relies on the IKKα homodimer activation in a manner dependent on NF-kB-inducing kinase (NIK). Activated IKKα phosphorylates p100 yielding p52. Then p52, RelB dimer translocates into the nucleus to activate its target genes. Numerous translational modifications modulate the activity of IKK and IκB proteins. The canonical pathway can be activated by a plethora of stimuli, antigen/MHC, cytokines, LPS, IL-1β, TNF-α. Activators of the non-canonical pathway include the TNFR superfamily, CD40 B-cell activating factor (BAFF), TNF-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) etc. Both pathways can interact at several levels (63)

Evidently, NF-kB activation and Foxo3a deactivation, are two possible outcomes of IKK activation that can contribute to promoting tumorigenesis

NF-κB can be Directly Activated Through DNA Damage Signaling

Induction of DNA damage has revealed the existence of an ATM-NEMO-IKK signaling pathway.

Grosjean-Raillard et al. (64) chose 4 AML cell lines to study DNA damage-induced NF-kB activation. increasing reactive oxygen species in KG1 AML cell line which did not exhibit NFkB activation resulted in phosphorylated ATM and phosphorylation of the IKK complex.It was shown that a complex of ATM and NEMO exited the nucleus to phosphorylate cytosolic IKK and p65 was translocated to nucleus. Conversely, ATM inhibition abolished IKK phosphorylation which was followed by apoptosis. The other three AML cell lines displayed constitutive NFkB activation and one of them P39 exhibited also strong constitutive ATM phosphorylation. In this latter line, ATM inhibition abolished IKK phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation. Next these authors compared ATM-NEMO-IKK signaling between CD34+ myeloblasts (hematopoietic progenitors) from healthy controls and patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (high-risk MDS differs from low-risk MDS in that apoptosis is widespread in the second and very rare in the former). Less than 1% of myeloblasts from healthy donors stain positive for phosphorylated ATM whereas a substantial fraction of myeloblasts from either high-risk MDS or AML patients exhibit positive pATM staining. In both, AML MDS myeloblasts pATM inhibition caused inhibition of NFkB (loss of nuclear p65) coupled to inactivation of the IKK complex and redistribution of NEMO from the nucleus to the cytoplasm

NFκB is constitutively activated in the mostf primary AML samples and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) but is not activated in normal HSCs (65) (66). IKK can be phosphorylated and activated by signaling through the PI3K/AKT or ERK/MAPK pathways which leads to Foxo3a inactivation and phosphorylation at S644 (and potentially NF-kB activation). Foxo3a can also be phosphorylated by Akt onT32, S253 and S315 and by ERK on S294, S344 and S425. Each of these phosphorylation events has been reported to stimulate FOXO3a nuclear exclusion, ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation

Reversion of signaling by inhibition of PI3K or AKT has been shown to result in redistribution of Foxo3a from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in numerous models but this was not observed in a study (66) involving primary AML human samples and a leukemic cell line. In a substantial fraction of the samples Foxo3a was excluded from the nucleus (nuclear localization was detected only in 7,5% of AML samples) in spite of Akt phosphorylation on S473 and thus of Foxo3a on T32 and S253. However, treatment with IC87114 which abolished these phosphorylation events did not result in Foxo nuclear translocation. Similarly, suppression of phosphorylation at ERK1/2 by a specific MEK inhibitor failed to induce Foxo nuclear translocation. In contrast, the anti-NEMO peptide that specifically inhibits IKK activity was found to induce Foxo3a nuclear localization in leukemic cells. Furthermore, an IKK-insensitive Foxo3a protein mutated at S644 translocated into the nucleus and activated the transcription of the Fas-L and p21Cip genes. This, in turn, inhibited leukemic cell proliferation and induced apoptosis. These, and the preceding observations may be interpreted to mean that in AML, IKK signaling takes control and replaces former signaling events. Whether this takeover of PI3K signaling by IKK is a general feature or is restricted to AML cells is unknown. The latter option would suggest a direct role of DNA damage in the origin of AML

Sequential Activation of the AKT/ IKK/NF-κB Pathway and Its Role in Cancer Metastasis and Angiogenesis

NF-kB activation via sequential activation of PI3K, AKT, and IKKβ is plainly shown in a report by Agarwal et al. (67). They studied two cell lines (SW480 and RKO) out of five CRC cell lines that displayed constitutive activation of AKT and both NF-κB and β-catenin dependent transcription. Inhibition of transcription of NF-kB targets was demonstrated by WT PTEN, KD AKT or KD IKKβ as well as by siRNA targeting of AKT and IKKα.Either WT PTEN, KD AKT or KD IKKα (a factor of the alternate pathway) inhibited both NF-κB and β-catenin transcription whereas KD IKKβ while inhibiting NF-κB did not have any effect on β-catenin expression in RKO and SW480). It is likely that Foxo3a deactivation would respond in the same way to the silencing of each of these members of the PI3K pathway. However, unfortunately Foxos were not examined in this report

An array-based gene expression analysis of the cell lines with constitutive expression of NF-kB and β-catenin following inhibition by KD IKKα or WT PETEN showed reduced expression of multiple genes implicated in angiogenesis and metastasis. Some of these genes are dependent on either NF-kB or β-catenin or both. IL-8, μPA or VEGF-C are dependent on both. Elevated expression of mRNA for these genes is observed in a substantial fraction of colorectal tumors compared to matched normal mucosa. (two-fold increase in IL-8 expression in about 85% of colon and 75% of rectal tumors whereas μPA was elevated in75% of colon and 79% of rectal tumors)

Other reports suggest, however, a more complex interplay between the intermediate targets of the pathway as some cooperation between intermediate targets rather than a strict linear sequence of activation, could be at play. Nevertheless, activation culminates in the final activation of NF-k via IKK (68).

Thus, returning to the dilemma raised above regarding AML, the independent signaling of IKK from previous steps of the PI3 pathway, suggests that an ATM-NEMO-IKK is exclusively responsible for NF-kB activation in AML, which emphasizes the primary role of DNA damage in AML. Similar reliance of Foxo regulation on IKK independently from other members of the PI3K pathway observed also in AM by Chapuis et al. above (66) ) raised the question of the extent of the coupled and simultaneous regulation of Foxo and NF-kB in tumorigenesis. Synergy between Foxos and NF-kB may blur attribution of effects to any of them in particular.

Tumor invasion through NF-kB activation has been associated with both the canonical and non-canonical pathways. In addition, it can be mediated through sequential activation of the pathway or single activation of a target at the converging downstream end such as any of IKK proteins. This route appears to be available to scaffold proteins, a class of proteins that regulate a signaling node in order to determine the choice of a downstream target. This has been shown for the scaffold protein connector enhancer of KSR (CNK) which facilitates Raf activation in the Ras-Raf-MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK)-ERK. CNK1 can regulate the ERK pathway and the JNK pathway. However, it was shown that CNK1 mediates human breast and cervical cancer by cooperation with the non-canonical NF-kB pathway, independently of ERK and JNK pathways (69)