Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Emergency Department Admission

2.2. Geriatrics Department

2.3. Long-Term Care Department

- Angiology evaluation

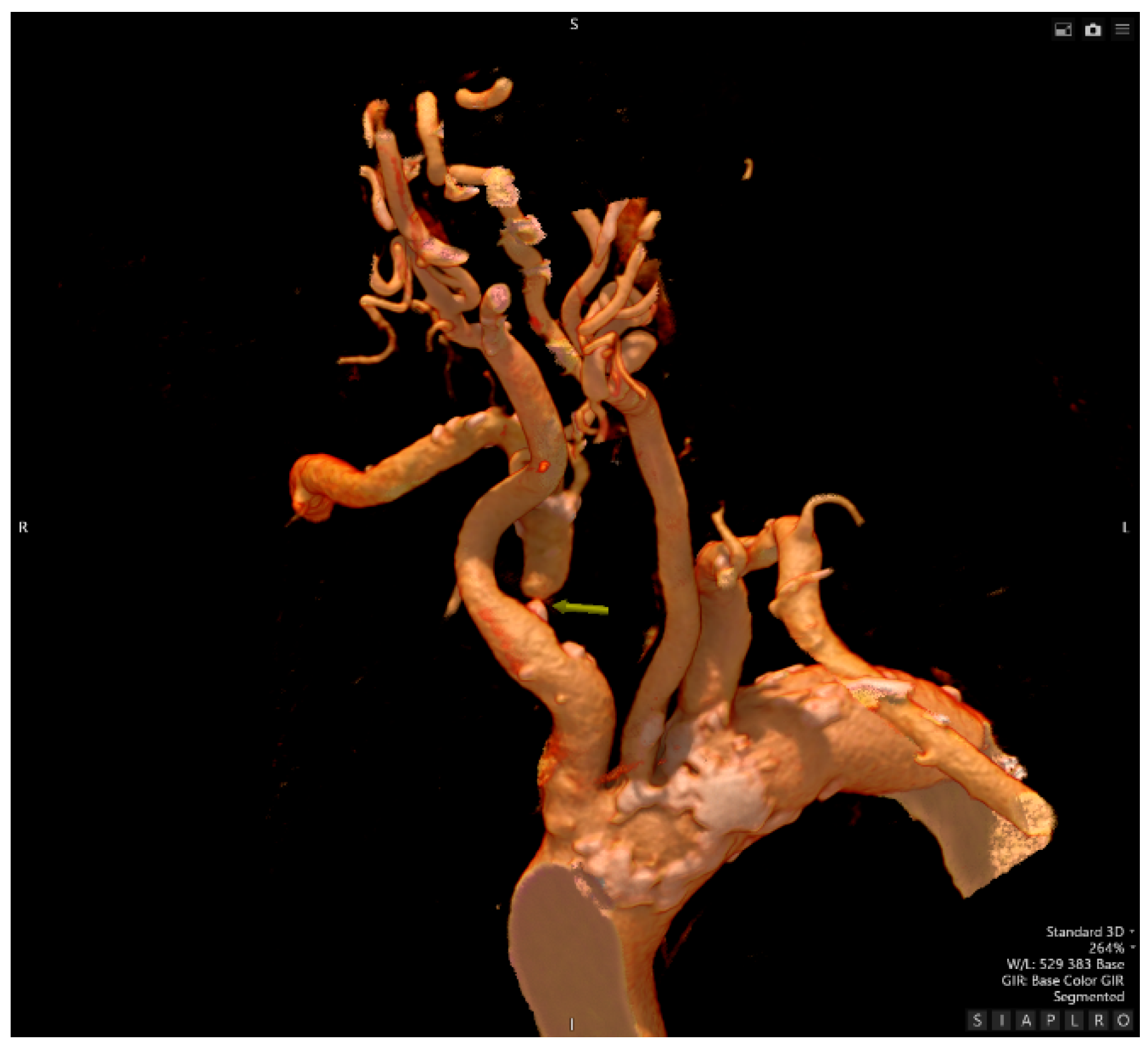

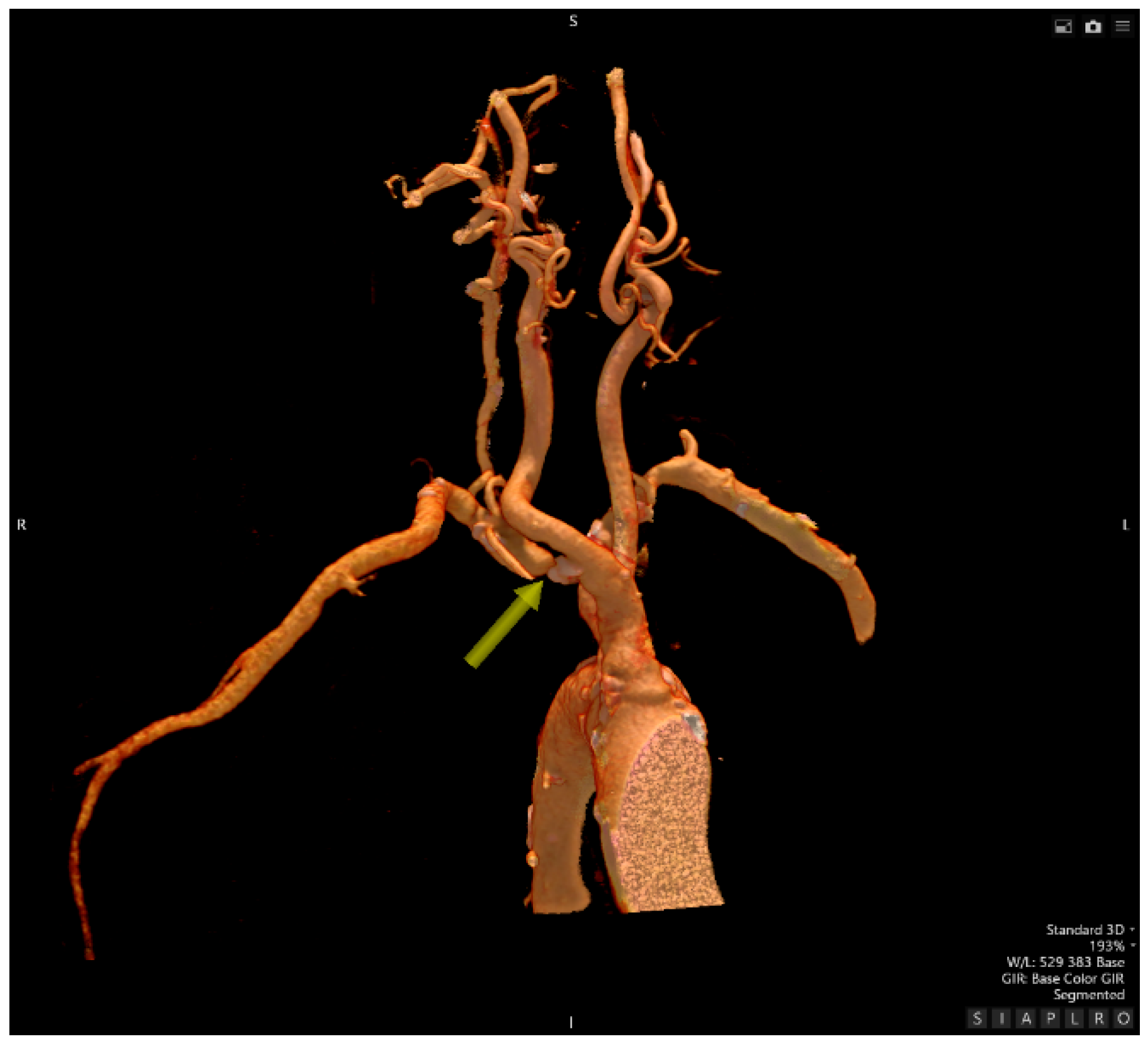

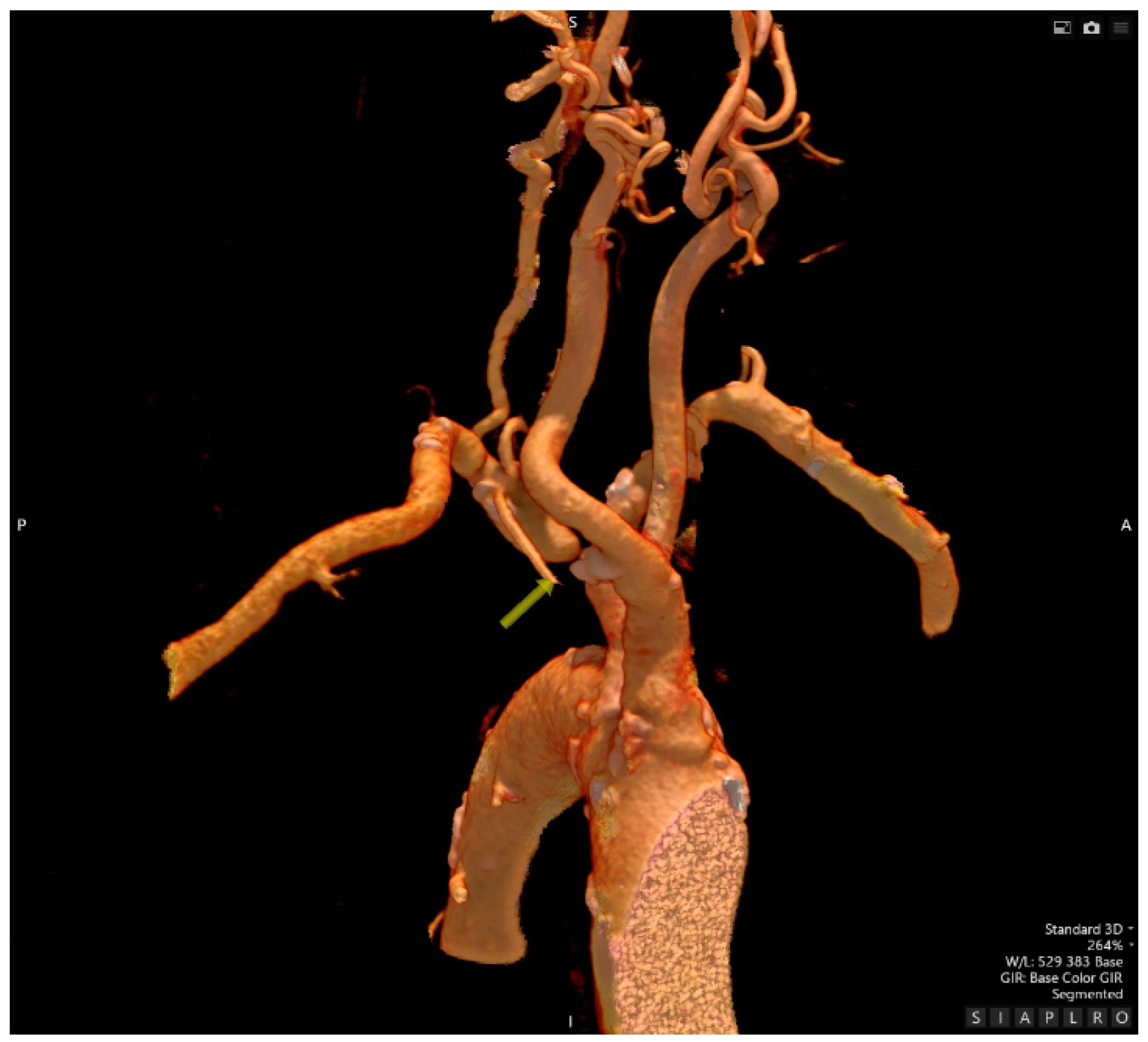

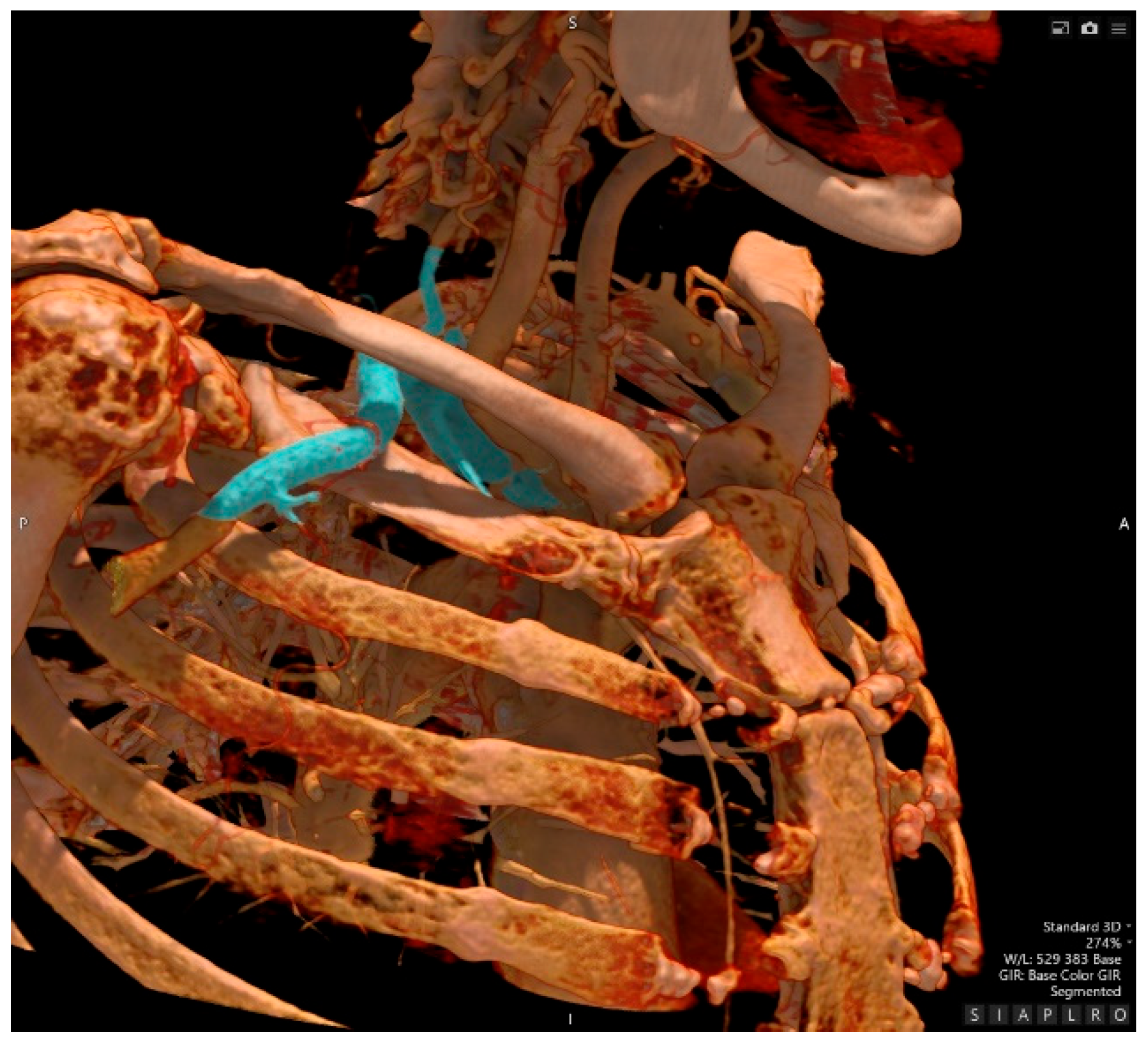

- Computed Tomography Angiography

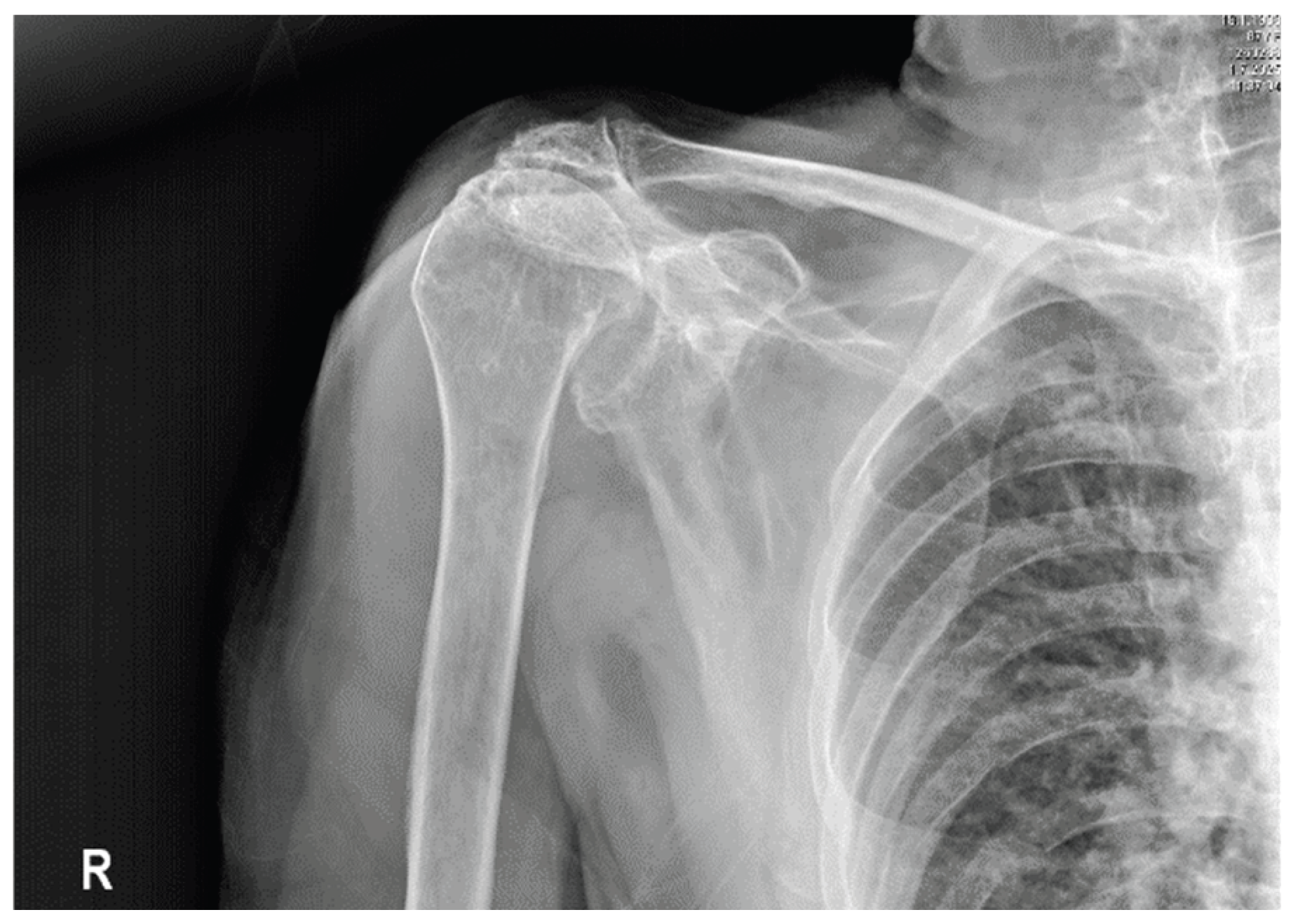

- Traumatology evaluation

- Neurology evaluation

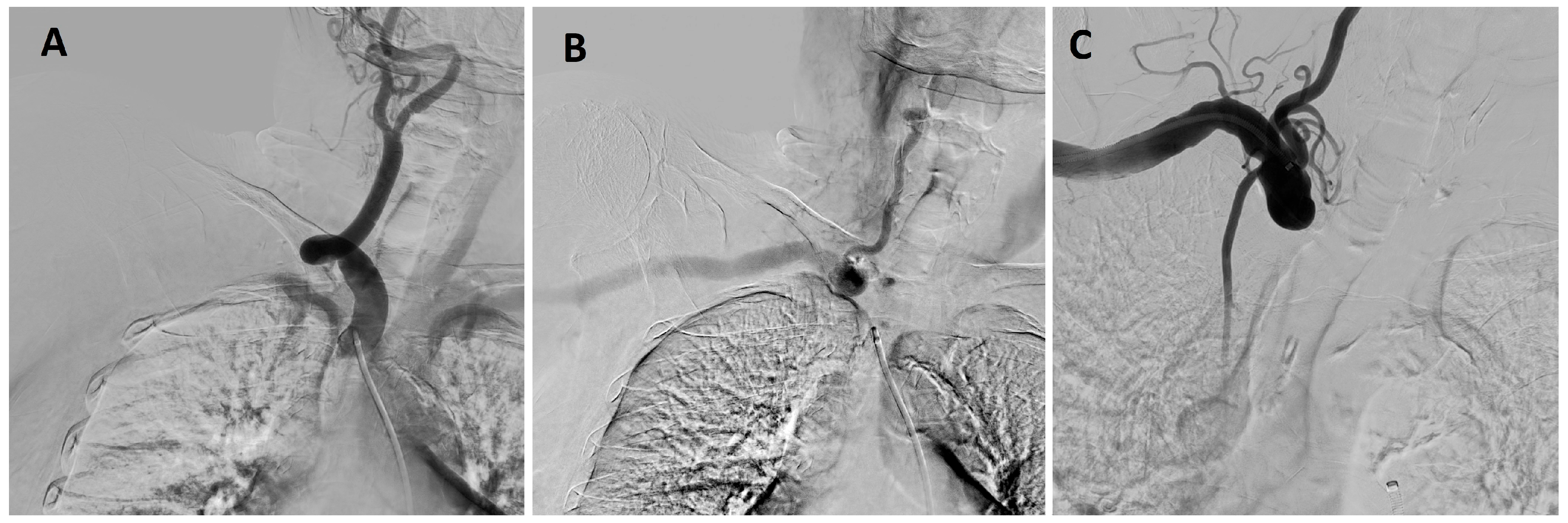

- Interventional Radiology – an attempt at recanalization of the right subclavian artery

- Neurosurgery evaluation

- Barthel index

- In-depth analysis of previous medical records

| 05/2012 | Department of Geriatrics - unstable angina |

| 08/2012 | National Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases - coronarography |

| 10/2012 | Oncological Institute - postmenopausal metrorrhagia |

| 12/2012 | Oncological Institute - uterine adenocarcinoma |

| 09/2015 | Department of Geriatrics - ISMN-related collapse |

| 2017 | Brought to the ER due to the ISMN-related collapse/short-term hospitalisation |

| 2018 | Brought to the ER due to the ISMN-related collapse/short-term hospitalisation |

| 2019 | Brought to the ER due to the ISMN-related collapse/short-term hospitalisation |

| 2020 | Brought to the ER due to the ISMN-related collapse/short-term hospitalisation |

| 2021 | Brought to the ER due to the ISMN-related collapse/short-term hospitalisation |

| 2023 | Brought to the ER due to the ISMN-related collapse/short-term hospitalisation |

| 06/2012 | Internal medicine outpatient |

| 07/2012 | Internal medicine outpatient |

| 07/2012 | Preoperative evaluation (Internal medicine) |

| 10/2012 | Preoperative evaluation (Internal medicine) |

| 11/2012 | Preoperative evaluation (Dept. of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care) |

| 01/2013 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 02/2013 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 06/2013 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 12/2013 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 06/2014 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 12/2014 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 06/2015 | Geriatrics outpatient |

| 01/2016 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 01/2017 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 09/2017 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 03/2018 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 10/2018 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 05/2019 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 01/2020 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 10/2020 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 07/2021 | Cardiology outpatient |

| 03/2023 | Cardiology outpatient |

- Outcomes & further care

3. Discussion

3.1. Impact of SAO and SSS on Cognitive Impairment

3.2. Subclavian Steal Syndrome / Subclavian Artery Occlusion and Hypertension

3.3. Methodology of Blood Pressure Monitoring in the Age Group ≥ 65 years

3.4. Lesson Learnt - Experience Gained from Case Study

- Always consider vascular causes in older patients with unexplained dizziness, syncope, or labile hypertension.

- Routine bilateral blood pressure measurement should be standard in both primary care and hospital settings for the aging population. This case emphasizes that bilateral blood pressure measurement should be a routine part of assessing older patients with labile hypertension, recurrent dizziness, or collapse episodes. Such a simple step can provide an important clue to subclavian artery occlusion.

- Musculoskeletal disorders, such as omarthrosis, can conceal severe vascular conditions, necessitating an interdisciplinary approach to diagnosis. Clinicians should be aware that common issues like degenerative joint disease might coexist with or hide life-threatening vascular problems. An interdisciplinary approach combined with careful physical examination is vital to prevent misdiagnosis.

- In frail, older patients with multiple comorbidities, conservative management can be an acceptable treatment option if the diagnosis is accurate and symptoms are well controlled.

- Overall, this case emphasizes the importance of combining clinical vigilance with straightforward bedside diagnostic techniques to enhance patient outcomes in geriatrics.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme |

| ACI | Internal Carotid Artery |

| C7 ACI | 7th Segment of the Internal Carotid Artery |

| CTA | Computed Tomography Angiography |

| DSA | Digital Subtraction Angiography |

| ISMN | Isosorbide mononitrate |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes |

| rCBF | Regional Cerebral Blood Flow |

| SAO | Subclavian artery occlusion |

| SPS3 | Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes study |

| SSS | Subclavian Steal Syndrome |

| UIATS | The Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score |

| VaD | Vascular Dementia |

| VRT | Volume Rendering Technique |

References

- English, J.A.; Carell, E.S.; Guidera, S.A.; Tripp, H.F. Angiographic prevalence and clinical predictors of left subclavian stenosis in patients undergoing diagnostic cardiac catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2001, 54, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, G.R.; Mahrer, P.; Aharonian, V.; Mansukhani, P.; Bruss, J. Prevalence of Subclavian Artery Stenosis in Patients with Peripheral Vascular Disease. Angiology 2001, 52, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lopez, J.A.; Werner, A.; Martinez, R.; Torruella, L.J.; Ray, L.I.; Diethrich, E.B. Stenting for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the subclavian artery. Ann Vasc Surg 1999, 13, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brountzos, E.N.; Petersen, B.; Binkert, C.; Panagiotou, I.; Kaufman, J.A. Primary stenting of subclavian and innominate artery occlusive disease: a single-center experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2004, 27, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennerici, M.; Rautenberg, W.; Mohr, S. Stroke risk from symptomless extracranial arterial disease. Lancet 1982, ii, 1180–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, K.T.; Zide, R.S.; Persson, A.V.; Jewell, E.R. Natural history of subclavian steal syndrome. Am Surg 1988, 54, 643–644. [Google Scholar]

- Khurshid, F.; Khurshid, A. Unraveling the complexity: a comprehensive guide to subclavian steal syndrome. Journal of Shifa Tameer-E-Millat University 2024, 6, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieter, R.; Darki, A.; Nanjundappa, A.; López, J. Subclavian steal syndrome successfully treated with a novel application of embolic capture angioplasty. International Journal of Angiology 2012, 21, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragičević, D.; Škorić, M.; Kolić, K.; Titlić, M. A case of acquired right-sided subclavian steal syndrome successfully treated with stenting using a brachial approach. Case Reports in Clinical Medicine 2014, 03, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, S. Subclavian fusiform aneurysm causing partial subclavian steal syndrome. Case report. Medical Ultrasonography 2014, 16, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Pham, R.; Coffey, N.; Kazimuddin, M.; Singh, A. Coronary subclavian steal syndrome with neurological symptoms after coronary artery bypass grafting. Cureus 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, R.; Gornik, H.; Gilbert, L.; Whitelaw, S.; Shishehbor, M. Bilateral subclavian steal syndrome. Case Reports in Cardiology 2011, 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arı, H.; Arı, S.; Camcı, S.; Karakuş, A.; Melek, M. Quantitative assessment of the effect of subclavian steal syndrome on left anterior descending artery flow. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi Arsivi-Archives of the Turkish Society of Cardiology 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibounig, T.; Simons, T.; Launonen, A.; Paavola, M. Glenohumeral osteoarthritis: an overview of etiology and diagnostics. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2020, 110, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, C.R.; Brookham, R.L.; Chopp, J.N. The working shoulder: Assessing demands, identifying risks, and promoting healthy occupational performance. Physical Therapy Reviews 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, C.; Oo, W.M.; et al. Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2025, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Tian, X.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Yuan, B.; Zhai, K.H.; Wang, C.W.; Yue, J.Y.; Zhang, L.J.; Li, Q.; Yan, H.Q.; et al. Executive dysfunction in patients with cerebral hypoperfusion after cerebral angiostenosis/occlusion. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica 2013, 53, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavente, O.R.; White, C.L.; Pearce, L.; Pergola, P.; Roldan, A.; Benavente, M.F.; Coffey, C.; McClure, L.A.; Szychowski, J.M.; Conwit, R.; et al. The Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) study. International Journal of Stroke 2011, 6, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.S.; Chiu, M.J.; Wu, Y.W.; Huang, C.C.; Chao, C.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, H.J.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Lin, L.C.; et al. Neurocognitive improvement after carotid artery stenting in patients with chronic internal carotid artery occlusion and cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2011, 42, 2850–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, V.J.; Yu, E.; Radhakrishnan, H.; Can, A.; Climov, M.; Leahy, C.; Ayata, C.; Eikermann-Haerter, K. Micro-heterogeneity of flow in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion revealed by longitudinal Doppler optical coherence tomography and angiography. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2015, 35, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Niizuma, K.; Rashad, S.; Sumiyoshi, A.; Ryoke, R.; Endo, H.; Endo, T.; Sato, K.; Kawashima, R.; Tominaga, T. A refined model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion resulting in cognitive impairment and a low mortality rate in rats. Journal of Neurosurgery 2019, 131, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.R.; Lee, S.R.; Han, J.S.; Woo, S.K.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, D.H.; Kwon, K.J.; Han, S.H.; Shin, C.Y.; Lee, J.; et al. Synergistic memory impairment through the interaction of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and amyloid toxicity in a rat model. Stroke 2011, 42, 2595–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaria, R. Vascular basis for brain degeneration: faltering controls and risk factors for dementia. Nutrition Reviews 2010, 68, S74–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, Z.; Fan, X. Research progress on the relationship between vascular aging and hypertension. Proceedings of Anticancer Research 2021, 5, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buford, T.W. Hypertension and aging. Ageing Research Reviews 2016, 26, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionakis, N. Hypertension in the elderly. World Journal of Cardiology 2012, 4, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afari, M.; Wylie, J.; Carrozza, J. Refractory hypotension as an initial presentation of bilateral subclavian artery stenosis. Case Reports in Cardiology 2016, 2016, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatmawati, S.; Watik, K.; Abdillah, A. The reduction of blood pressure in elderly people with hypertension through morning walk therapy. Journal of Nursing Practice 2024, 7, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwa, P.; Gorczyca−Michta, I.; Kluk, M.; Dziubek, K.; Wożakowska−Kapłon, B. Variability of circadian blood pressure profile during 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in hypertensive patients. Kardiologia Polska 2014, 72, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Águila, F.; Torres, C.; Extremera, B.; Alonso, J. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in the Elderly. International Journal of Hypertension 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, E.; Oparil, S. Management of hypertension in the elderly. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2012, 9, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).