1. Introduction

Understanding the nature of non-suicidal self-injury and its prevalence among the adolescent population is the aim of this scoping review, which is part of a large research project initiated following the observation of the increase in psychopathological onset of various kinds affecting this segment of the population following the emergence of COVID-19 [

1].

The aim is to frame the phenomenon of self-harm from a holistic perspective to understand its situational nature and consider how it offers itself, in the patient's experience, as a 'relief' from psychological suffering. All this to avoid early and therefore erroneous diagnoses of borderline personality disorder (BPD), a psychopathological picture generally characterized by emotional dysregulation and self-injurious acts [

2,

3].

The epistemological background of the present review is the integrated Gestalt psychotherapeutic model according to which the symptom is configured as a behavior aimed at achieving a homeostatic balance in the presence of an emotional tension to which one is unable to respond adequately, either due to a lack of affordances (

literally 'invitation to use', i.e.

the physical quality of an object that suggests to a human being the appropriate actions to manipulate it) [

4] in the environment to which one is exposed, or due to factors of another nature, such as genetic ones.

1.1. Non Suicidal Self Injury (NSSI) and Self-Mutilation (SM)

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition [

5], NSSI behaviour is defined as '

a series of intentionally self-injurious acts against one's own body conducted for at least 5 days in the past year'. NSSI is included in Section III of the manual where all diagnostic entities that require further study and investigation are listed. Non-suicidal self- injury, therefore, means all those non-lethal injuries inflicted on the body, either superficially or significantly, without suicidal intent. Excluded are socially accepted behaviours such as piercings, tattoos, play piercing and scarification, religious rituals or accidental and indirect harm due to substance abuse and behavioural addictions such as, for example, eating disorders; while cigarette burns, cuts and self-mutilation (SM) such as pinching, scratching and biting are to be included. The most widespread self-injury practice is cutting: cutting, wounding and incising the skin, especially of the legs and arms, through the use of razor blades, pocket knives, used cans and sharp knives. Although it is not one of the most common self-harm practices, a study published in 2002 [

6] on a school sample of adolescents found that about 14% of the students reported having experienced self-mutilation behavior at some time, with the female gender being more frequent.

1.2. Emotional Regulation and Coping Strategies

Emotional regulation, according to Mauss, Bunge and Gross [

7] is defined as "the individual's voluntary and automatic attempts to influence the emotions he or she feels, even while experiencing them, by modulating the experiential and expressive dimension". Thus, the possibility exists that the regulation of emotional experiences can have a dual nature: intentional or unintentional. The studies of Gross and colleagues highlight two distinct categories of the regulatory process of emotional experiences:

- -

Cognitive emotion regulation

voluntary and intentional regulation involving several cognitive processes. Gross identifies five regulatory strategies that intervene at different stages of the emotion process:

The subject avoids situations and/or contacts that may act as a stimulus for the genesis of painful emotions.

“problem-centred coping” [

8], i.e. a modification of the environment to reduce the emotional impact of the situation.

Directing attention to some elements of the situation while neglecting others.

"emotion-centred coping" [

8] i.e. re-evaluating what the subject thinks about the situation and the demand of the environment to alter its emotional significance.

acting directly on the emotion while it is in progress through certain modalities such as suppression, inhibition, use of medication, sharing.

The first three strategies intervene during the phase in which the emotional experience is being constructed, while the last two intervene after the generative process, acting on the components of the emotion.

- -

Automatic emotion regulation:

it is triggered by the simple registration of a sensory input; it can be defined as a modification of one's emotions in the absence of an intentional decision and without directing controlled and conscious attention to it [

9].

Thanks to studies conducted on emotional regulation in children, Nancy Eisenberg et al. [

10], propose a model of emotional regulation that emphasizes its close correlation with the ability to control - adaptively - the emotional process. Thus, it is possible to make a further distinction between two types of emotion control:

effortful control, i.e. the ability to inhibit a dominant response it or replace it with another type of less dominant response through the inhibition of behavior in order to react more adaptively; reactive control, i.e. an unintentional and inflexible control, guided by impulses and automatic responses.

The relationship between control and regulation, according to the author, takes the form of a continuum at the ends of which we find reactive hyper-control on the one hand, reactive hypo control on the other and, in the middle, actual regulation influenced by high or low levels of voluntary control.

1.3. Attachment Theory and Emotional Regulation

According to attachment theory [

11] the child is initially in a form of dependency on the caregiver for the satisfaction of basic needs, but also for the regulation of affectivity. Over time, children learn to develop their own regulatory skills through certain actions of the parent or caregiver of reference such as validating and encouraging emotional expression and communication of their moods, as well as showing and exemplifying strategies for coping with unpleasant emotional experiences [

12]. At this crucial time in the life cycle, the parent has the task of presenting the external world to the child in a more digestible form, so that the child learns tools for adapting to and coping with the challenges posed by the external environment [

13].

To study the attachment models proposed by Bowlby, Mary Answorth set up the Strange situation experiment [

14], defining various types of bonding:

- -

Secure: the child relies on the care of the attachment figure and feels safe to explore the environment even in dangerous situations, showing contentment when the mother returns

- -

Insecure avoidant: the child does not rely on the care of the attachment figure, who probably showed

- -

little willingness to accept the needs, feels distress at the mother's departure, but will tend to avoid her when she returns. Usually, this attachment develops in the case of a caregiver who is refusing and unwilling to accept the child's needs.

- -

Insecure anxious - ambivalent: the child is strongly distressed by the mother's departure and shows anger and hostility when she returns, generally this attachment develops in the case of a caregiver who is unwilling to accept the child's needs in an inconstant manner.

The attachment style develops in the child from that which in turn the caregiver developed in childhood; therefore, the parent will show the child his or her ability, adaptive or maladaptive, to cope with situations of emotional distress [

15].

Insecure attachment styles are predictors of difficulties in managing emotions, such as avoidance of distressful situations or over-regulation of one's own internal states, typical of insecure avoidant attachment.

2. The Adolescent Brain Between Cutting and Emotional Regulation

To fully understand the phenomenon of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and its prevalence among adolescents, it is necessary to consider the characteristics of brain development typical of this age group, which help to explain NSSI as an emotional regulation strategy. Brain development tends spontaneously towards an increase in the level of integration whereby, progressively, an ever-higher degree of specialisation of the different brain areas is achieved with the construction of increasingly efficient neural networks. As a function of these processes, information processing becomes more specialized and powerful.

Brain changes in this period of life focus on areas of the prefrontal cortex and other frontal regions, which are involved in advanced cognitive functions as well as in the integration, synthesis and regulation of behavior. These changes do not proceed in an augmentative form but in a reorganizational and integrative mode, which will never again be repeated in life with the intensity it has in this period [

16]. And it is precisely the increased possibility of integration at the level of the cortex that enables the emergence and subsequent evolution of a wide range of abilities, such as cognitive control (reducing impulsivity through the development of awareness of the consequences of one's actions), emotional regulation and the definition of the personal and social self [

17].

The prefrontal region acts as a real junction between the cortex and the limbic and brainstem subcortical areas; moreover, it integrates inputs from the various regions of the body (enteroception) with those from outside (exteroception). The prefrontal cortex therefore acts as an important center for integrating and coordinating information and energy from different sources.

In turn, the limbic system, a subcortical area, plays a prominent role in detecting elements in the environment that are worthy of attention, potential sources of gratification or threat. The action of the system alone would determine instinctive and automatic responses. The primary function of the libido system is to generate an emotion that, when well-integrated with the prefrontal cortex to which it is connected, determines the appropriate response to what is happening in the environment.

The brain functions in a 'state-dependent' mode, which means that it is strongly influenced by the context: environmental situations and emotional state can interfere with or favors integration functions [

18]. Integration state is the key element; its lack does not allow the development and performance of complex functions such as self-awareness, empathy, emotional balance, and competence in modulating intense emotions or disruptive experiences, interfering with decision- making processes [

19,

20] and thus increasing susceptibility to violent reactive behavior, such as NSSI. What happens is that the areas of the brain below the cerebral cortex are activated without the 'calming' action of the prefrontal cortex having a chance to be introduced.

2.1. The Influence of Attachment on Neurobiological Development

Extending the view backwards, it is necessary to link the discourse to the earlier phase of development, because brain formation starts from intrauterine life and continues intensively in the early years. In this phase, in continuity with what was stated earlier, the environment massively directs the growth and functioning of the central nervous system. This environment is primarily configured by the presence, or absence, of a caregiver attentive and responsive to the infant's needs; its action has the function of modulating precisely the development of the prefrontal and limbic areas (including the amygdala, the danger signal center and the activation/regulation of fear) through the quality of attachment and the experience of relational security [

21].

If an insecure or disorganized attachment mode persists in adolescence, this leads to hyperfunctioning of the amygdala in response to danger signals, resulting in difficulties in inhibition and conscious emotional regulation. This limits the integrated processing of bodily sensations and emotions, which leaves the adolescent in a state of disconnection or confusion with respect to his or her own feelings [

22].

3. The NSSI in a Gestalt Perspective

Among the different epistemological frameworks from which the phenomenon of NSSI can be read, the present literature review is situated within Gestalt psychotherapy, which offers a reading of psychopathological experiences by operating a synthesis of bodily, experiential and phenomenological models [

23]. The Gestalt view of psychopathology is not to be understood as the presence/absence and duration of a specific symptom pattern, but as a creative act of the organism in relation and in response to its environment. According to this approach, every symptomatic behavior, even the most dysfunctional and malaise-generating, must be understood as a creative function of the organism [

24] which in this way seeks to maintain homeostatic equilibrium in relation to an environment perceived as unsustainable or lacking adequate affordances. From this point of view, it is therefore clear that it is possible to understand the symptom as the best creative adaptation [note] that the person was able to find in reference to a need that remained unsatisfied or an emotional need that could not otherwise be integrated.

The emergence of this form of the phenomenon becomes understandable by grasping how the person, with his or her experiential experience, is in constant exchange and contact with the environment, which modifies and is modified by this encounter [

25]. Fritz Perls, one of the main and greatest authors of Gestalt psychotherapy, in his writings "

Ego, Hunger, Aggression" [

26] and "

Theory and Practice of Gestalt Therapy" [

27], describes a theory of the encounter with the world that would take place in a place called "contact boundary" identified in our sensory organ par excellence: the skin. For Fritz Perls and for the subsequent Gestalt authors and theorists, the experience takes on a cyclic form, properly defined contact cycle[note], which starts from drives and needs felt in the body and through the body nourished, while neurosis is described as the maladaptive if creative attempt to interrupt this experience for the defence of the organism, to the detriment of the nourishment of the latter. According to this view of Perls the symptom is "

the best possible compromise that the organism has managed to construct" at the contact boundary [

27].

According to this perspective, self-harm would constitute the only form of adaptation that the individual, especially the adolescent, is able to create to manage an intolerable emotional experience and the interruption of contact with such an emotional experience would take place through the deflection from emotional pain to physical pain. In some cases, the self-injurious experience is recounted as the attempt to interrupt the egotistical experience by tearing the thickening at the contact boundary to return to feeling through the injury inflicted on the body.

In the Gestalt view, the NSSI is understood in its meaning as a 'salvific symptom' [

28], that is, as a creative act of the organism which, not finding functional ways of self-regulation, produces this survival strategy. It is therefore to be understood as an attempt to reconstruct contact with the environment, the body and experience, protecting the individual from the perceived risk of dissolving into emotional suffering or internal fragmentation. Goodman [

27] refers to it as a 'protective block' that both hinders and protects at the same time from full contact with the experience one fears.

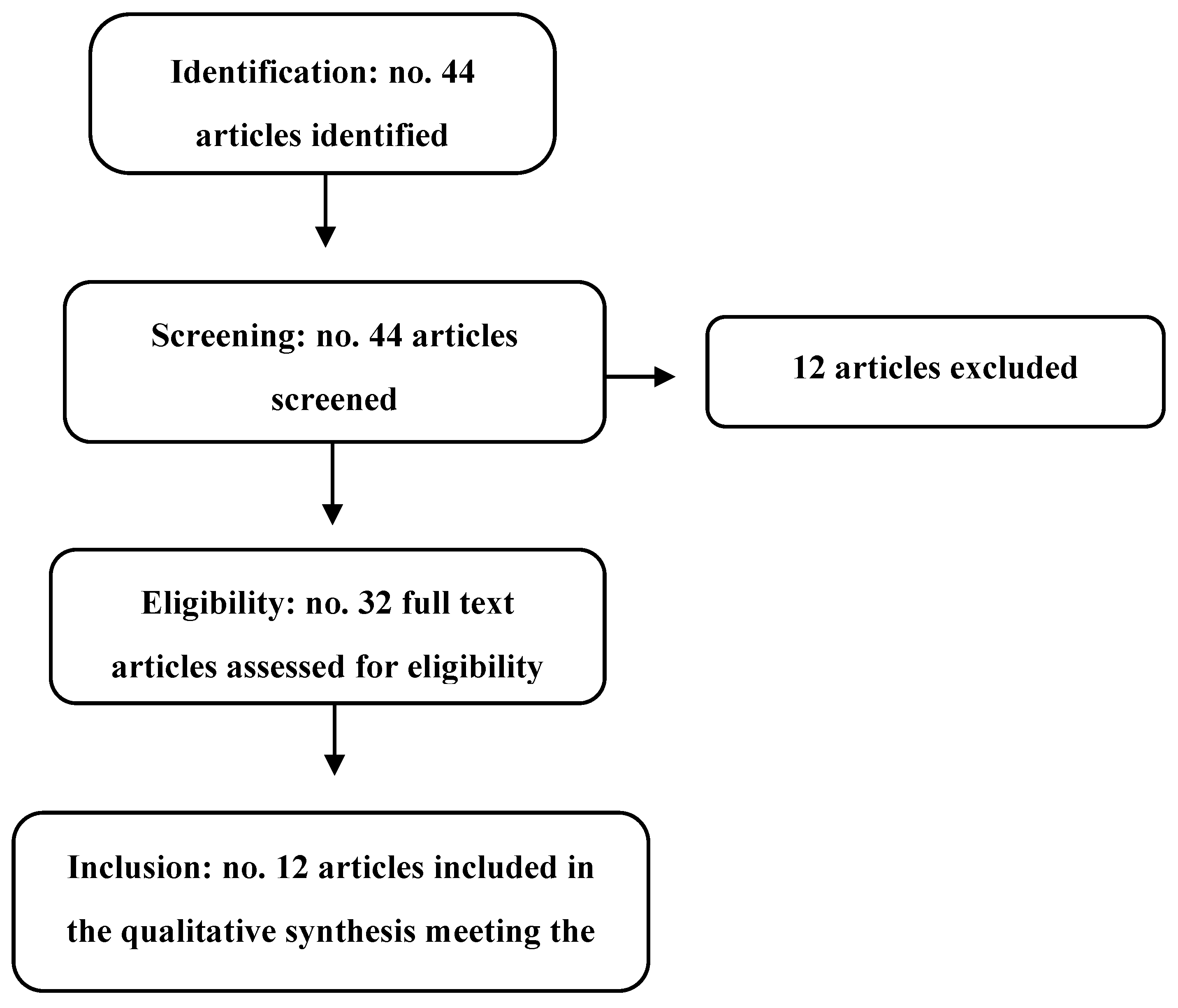

4. Methodology and Inclusion Criteria for Selected Articles

In order to demarcate the field of study relating to the topic under consideration by analyzing the most recent studies in the international scientific literature, as well as to identify possible research directions, a scoping review was conducted in accordance with the standards of the PRISMA protocol (Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [

29], consisting of a checklist of 27 items.

The main sources from which the information and resources useful for the research were taken are the following electronic databases: Google Scholar; PubMed. From these, articles pertaining to the most recent scientific research for the years 2013 to 2023 were selected. The search keywords were adolescents; self-injurious behavior; self-injury; emotion regulation; attachment theory; coping style; attachment bond (

Table 1).

The language of the selected articles was predominantly English and, following the reading of the abstract, 44 articles were selected as fit for purpose. Among the materials displayed by the search engine, dissertations and reviews were excluded, while among those initially selected, studies investigating the topic of NNSI in connection with specific psychopathological frameworks or investigating the phenomenon within a specific theoretical framework of a psychotherapeutic orientation were subsequently excluded.

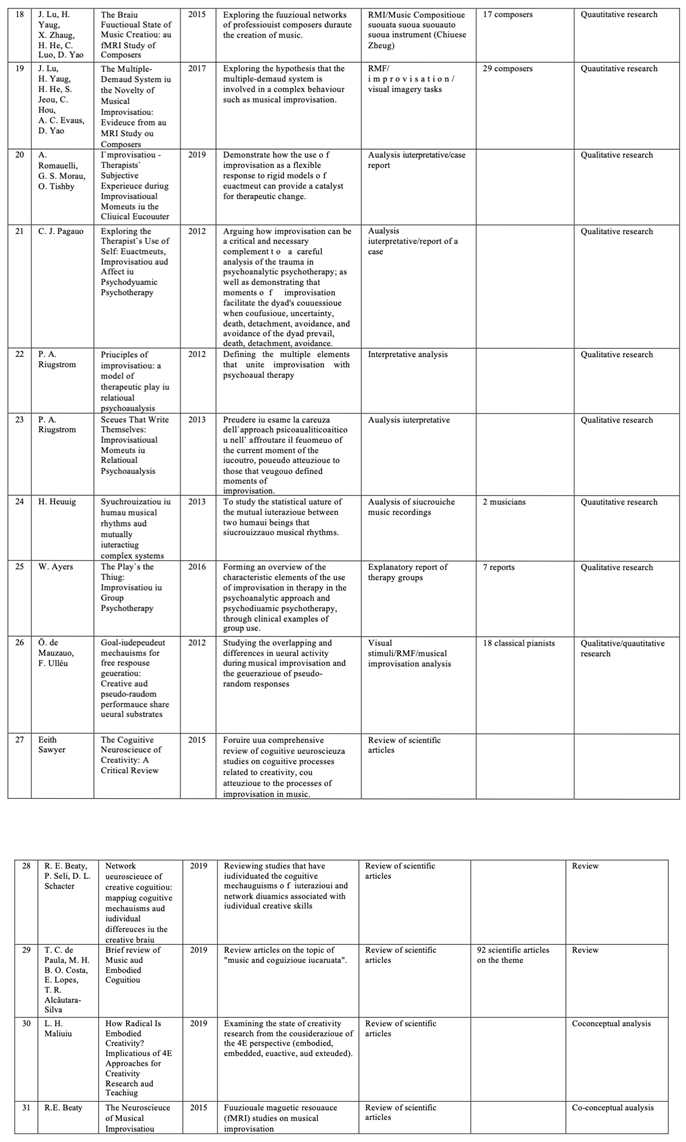

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Criterion |

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

| Year of publication |

2013 - 2023 |

Previous year 2013 |

| Language |

English |

Italian |

| Article type |

Original studies, opinion articles |

Dissertations, reviews |

| Focus of the study |

Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior in adolescence; correlations between NSSI and emotional regulation; correlation between emotional regulation and attachment style; investigation of attachment styles and coping strategies such as NSSI. |

NSSI in relation to specific psychopathological pictures; NSSI in adolescence according to specific psychotherapeutic models. |

| Reference sample |

Adolescents |

Children, adults, elderly |

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the article selection and screening process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the article selection and screening process.

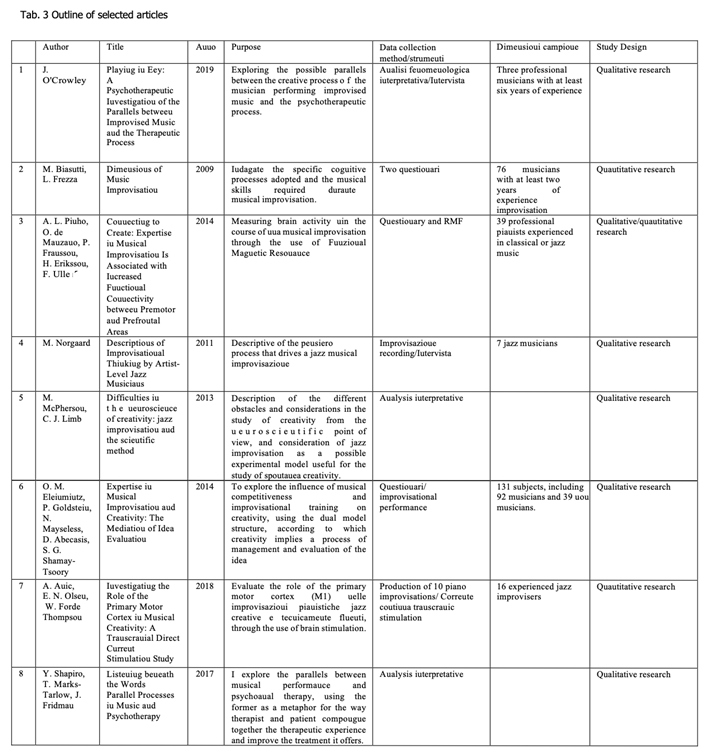

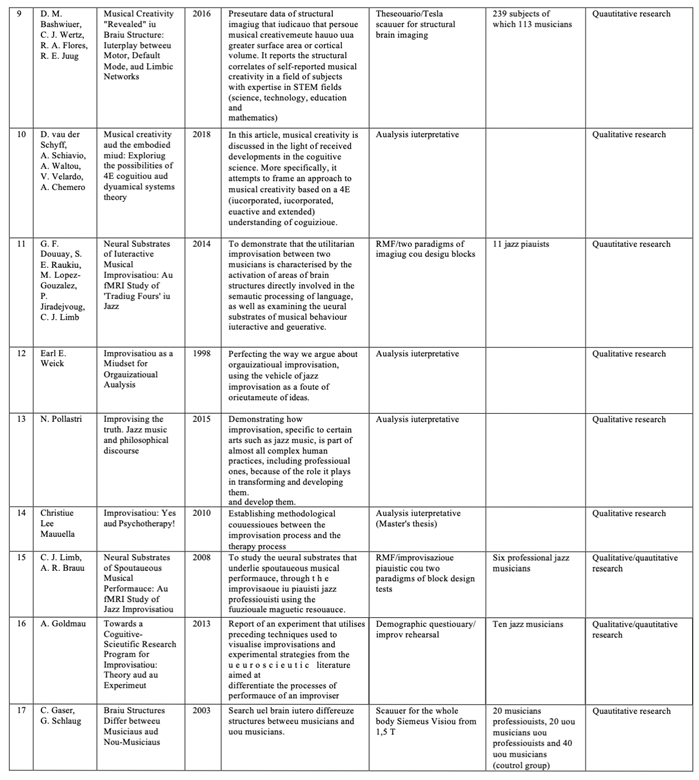

5. Summary and Discussion of Results

Following an analysis of the materials selected from the literature, it was possible to deduce the existence of a strong association between deficits in emotional regulation and self-injurious behavior [in Tab 3, n.10, 13]. In a study on a sample of 436 adolescents [in Table 3, n.1], focusing on two aspects of emotional regulation: difficulty in coping with unpleasant emotions and difficulty in recognizing emotional experiences through listening to enterceptive sensations, the psycho-regulatory function of self-harm became clear. The results of the study, in fact, indicate that NSSI acts as a moderator of the relationship between difficulties in emotional regulation and suicidal ideation, highlighting a possible risk-amplifying effect. The use of NSSI as an emotional regulation strategy was also found to be important in another study [in Table 3, no. 3] carried out on a sample of 272 students, of whom 48 stated that they had used cutting to achieve psychological well-being. This study related family functioning to emotional regulation as predictors of increased involvement in NSSI, finding a positive correlation between poor family functioning and increased risk of self- harm and identifying emotional regulation as a moderator of this relationship. The results of this study therefore indicate that an essential role in adolescents' choice of self-harm strategies is played by living in problematic family environments and adopting maladaptive emotional regulation strategies.

Furthermore, some data support the hypothesis that in experiential conditions characterized by prolonged psychological stress, resorting to self-injury is a coping strategy on the part of the adolescent. This consideration emerged from the analysis of a study [in Table 3, no. 2] that identified the massive recourse to such behavior during the COVID - 19 pandemic emergency, a situation of extreme and prolonged emotional distress. The results obtained from this research show how prolonged conditions of stress characterized by the impossibility of control, which faithfully reproduce the situation experienced during the pandemic, lead to the experience of complex emotional experiences that are not completely acceptable, together with the adolescent's perception of the impossibility of modifying these same emotions. In addition to difficulties in emotional regulation, other motives contributing to the use of this maladaptive coping strategy were found to be self-punishment, sensation seeking, and feeling generation.

With reference to the hypothesis that attachment bonds may play a role in the incidence of the phenomenon as protective factors or as risk factors, a study included in the review [in Tab. 3, n.8] shows that a qualitatively poor attachment with caregivers is strongly correlated with self-injurious behavior. This is because negative emotions, resulting from the dysfunctional relationship with caregivers, may mediate the connection between attachment bonding and NSSI: those who reported using NSSI behaviors have anxious attachment and use suppression in emotional expression. Also, a good attachment bond in qualitative terms, as several studies show [in Table 3, n.5, 7], is a protective factor against the onset of NSSI behavior. In this study in particular it emerged that the mediation model offered by attachment differs depending on the figure considered: that relating to the father is based on the emotional coping style, while that relating to the mother is associated with emotional experiences and consequently it activates different mechanisms in triggering self-injurious behavior, in line with the hypothesis of the specificity of attachment.

A study that contrasts this assumption [in Table 3, n.6] in favors of the hypothesis supporting the correlation between attachment style and increased vulnerability to self-injurious practices against a background of poor emotional coping skills, shows that the direct link in this correlation is not supported by sufficient evidence. The study shows that the link between attachment and self-injury is mediated by coping strategies and that secure attachment can act positively - indirectly - as it enables the development of problem-focused coping skills; that paternal attachment has a specific influence because it relates to the perception of one's own problem-solving abilities and that an insecure paternal attachment being to a lower estimation of one's own coping abilities may favors involvement in NSSI practices; and finally that an insecure attachment style facilitates access to self- injurious practices because it hinders the development of good emotional regulation.

Conclusions

The present literature review has shown that adolescents' recourse to NSSI practice can be understood as an attempt to contain emotional distress, in situations of substantial difficulties in affective regulation and coping strategies. In particular, the major risk factors are constituted by the difficulty in tolerating negative emotions and limited access to functional regulatory strategies, reinforced by environmental conditions characterized by vulnerability such as those resulting from insecure attachments, low family support and prolonged stress (such as that experienced during the pandemic).

Although the non-suicidal nature of self-harm may suggest that this behavior is not very dangerous, data in the scientific literature show that it is a phenomenon of great relevance, both clinically and socially.

These data are corroborated by the Gestalt view that conceives the symptom as a phenomenon with meaning and as a salvific act, aimed at the psychological and emotional survival of the individual, to be understood as a creative attempt to reorganize the self. Self-harm can thus be understood as an act that, however dysfunctional, constitutes the best possible strategy for maintaining a balance and contact with the self, when other modes of regulation have become inaccessible.

Finally, it is necessary not to forget all that neuroscience has established about brain development. In adolescence while the subcortical areas responsible for emotional reactivity are mature and active, there is incomplete maturation of those areas (prefrontal) designated for regulation, problem solving and action planning. This disparity in neurological maturation makes adolescents physiologically prone to impulsive behavior, including self-injurious behavior, especially when dysfunctional environmental and relational factors present themselves as activators against which there are no effective emotional regulation strategies.

All this evidence indicates the need to overcome a merely symptomatological view of the phenomenon, to embrace a bio-psycho-social and phenomenological perspective that considers the adolescent in his relational, family, school and community context [

30]. The future perspectives towards which to evolve, in therapeutic practice, indicate a direction of an ecological and systemic type in which the bodily, relational and experiential dimensions are integrated, involving a broad vision, calling into question the development of a complex methodology that envisages the integration in the intervention procedures of the system within which the adolescent acts, operates and constructs his own meanings and horizons of meaning.

Authors' contribution

SD and LLM conducted the literature screening process, selected relevant articles for review, and wrote the article; VC and CS supervised the analysis and selection of relevant articles from the literature; EM select relevant articles, supervised the writing of the article and ensured the accuracy of the references; and RS served as the scientific supervisor of the selection process, analysis of relevant articles, and writing of the final scientific article.

Funding

No research funding was requested or received.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This manuscripts not involving human participants, human data or human tissue.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- Cipponeri, S.; Maltese, V.; Mazzara, M.; Lucido, R.A.; Catania, V. Dietary Habits and the COVID-19 Emergency. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2020, 2, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Monticone, I.; Arcangeletti, M. The integrated psychotherapeutic treatment of borderline disorder in adolescence: narration of a clinical case. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2022, 4, 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Guerriera, C.; Cantone, D. The current clinic in child and adolescent psychoanalysis: questions and heuristic hypotheses. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2019, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. The Psychology of Everyday Things; New York: Basic Books, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed., text rev.; American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.; Heath, N. A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2002, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss IBMauss, I.B.; Bunge, S.A.; Gross, J.J. Automatic emotion regulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2007, 1, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Drummond, S. Lazarus and Folkman's psychological stress and coping theory. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice; 2017; pp. 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L. Changing emotion with emotion. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2025, 7, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L. Emotion-related self-regulation: Conceptual issues, correlates, and developmental relations. In Handbook of affective sciences; Davidson, R.L., Scherer, K.R., Goldsmith, H.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. The nature of the child's tie to his mother. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 1958, 39, 350–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iennaco, D.; Mosca, L.L.; Longobardi, T.; Nascivera, N.; Di Sarno, A.D.; Moretto, E.; Messina, M. Personality: neuroscience, psychopathology and psychotherapy: current view and future perspectives in research studies. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2019, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, M.; De Falco, R.; Amore, G.; Capparelli, T.; Dell'Orco, S.; Giannetti, C. . & Annunziato, T. The effect of decision-making styles and parental anxiety on the perception of childhood fears: a pilot study. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2021, 3, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Bell, S.M. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a Strange Situation. Child Development 1970, 41, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Leva, G.; Nascivera, N.; Di Sarno, A.D. Parenting practices of parents of students in a High School in the province of Salerno. An exploratory research. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2022, 4, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L.D.; Doneda, M.; Dalgo, E. "The" adolescent brain: the age of opportunity; Code, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.J. The adolescent mind; Raffaello Cortina Publisher, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leva, A. Being in the world "between" psychotherapy and neuroscience. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2023, 5, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Orco, S.; Messina, M.; Di Leva, A.; di Ronza, G.; Letterese, M.; Romitelli, T.; Costa, V. Decision-making in patients undergoing dialysis treatment: a research hypothesis on the Disjunction Effect. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2020, 2, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, M.; Dell'Orco, S.; Annunziato, T.; Giannetti, C.; Alfano, Y.M.; Guastaferro, M.; Iennaco, D. Anatomy of an irrational choice: Towards a new hypothesis study on decision making and the dysfunction effect. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2019, 1, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Scognamiglio, C. Preventive and therapeutic interventions in the perinatal period: An intervention model from an integrated gestalt perspective. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2020, 2, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sarno, A.D.; Costa, V.; Di Gennaro, R.; Di Leva, G.; Fabbricino, I.; Iennaco, D. . & Mosca, L. L. At the roots of the sense of self: Proposals for a study of the emergence of body awareness in early childhood. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2019, 1, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Francesetti, G. The phenomenal field: The origin of the self and the world. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2024, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zinker, J. Creative processes in Gestalt Psychotherapy. F. Angeli. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rainauli, A. Through the eyes of Gestalt therapy: The emergence of existential experience on the contact boundary. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2025, 7, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Perls, F.S. Ego, hunger and aggression: A revision of Freud's theory and method; Gestalt Journal Press, 1947; (Original work published in 1942). [Google Scholar]

- Perls, F.S.; Hefferline, R.F.; Goodman, P. Gestalt therapy: Excitement and growth in the human personality; Julian Press, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Francesetti, G.; Gecele, M.; Roubal, J. Gestalt psychotherapy in clinical practice. From psychopathology to the aesthetics of contact. Milan: FrancoAngeli. ISBN 978-88-204-2072-7, pp. 816;€ 55, 00. Gestalt Notebooks, 2014; 27. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; Clark, J.; Clarke, M.; Cook, D.; D'Amico, R.; Deeks, J.J.; Devereaux, P.J.; Dickersin, K.; Egger, M.; Ernst, E.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Grimshaw, J.; Guyatt, G.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Kleijnen, J.; Lang, T.; Magrini, N.; McNamee, D.; Moja, L.; Mulrow, C.; Napoli, M.; Oxman, A.; Pham, B.; Rennie, D.; Sampson, M.; Schulz, K.F.; Shekelle, P.G.; Tovey, D.; Tugwell, P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glorioso, A.; D'Anna, E.; Montalto, M.; Sperandeo, R.; Diamare, S. The Conscious Creative Embodied Aesthetic Experience® method: from a bio-psycho-social perspective. Phenomena Journal-International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy 2024, 6, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).