Introduction

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic pain disorder that can occur after extremity trauma, surgery, or de novo. CRPS is characterized by a variety of symptoms that include increased/disproportionate pain (hyperalgesia, allodynia), inflammation, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction.[

1] Diagnosis is based on the Budapest Criteria, and includes: 1) continuing pain disproportionate to the original injury, 2) at least one symptom in three of four categories (sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor, trophic), 3) at least one sign in two of the aforementioned categories, and 4) no other diagnosis better explains the presentation.[

2] Over time, patients present with a red, hot, and swollen limb which gradually transitions to a cold, blue, and clammy appearance. These distinct presentations are colloquially known as the acute/warm and chronic/cold phases.

Post-surgical CRPS is the second most common inciting factor after trauma.[

3] The majority of the literature details post-surgical CRPS after orthopedic surgery, such as carpal tunnel release,[

4,

5] fasciectomy for Dupuytren contracture,[

6] or foot and ankle surgery,[

7] with incidences up to 10.4%.[

5,

6,

7,

8] However, very little is known about CRPS following total knee arthroplasty (TKA). There are few reports of the condition in the literature and its true incidence remains unknown. Still, up to 20% of TKA patients experience chronic post-surgical pain with incidences of neuropathic pain reported up to 14% at 5 years.[

9,

10] Given the prevalence of chronic and neuropathic pain in these patients, along with the diagnostic difficulty of distinguishing CRPS from postoperative inflammation, CRPS may be underdiagnosed in this population.

This gap in knowledge has clinical implications in treating and diagnosing CRPS after TKA. As the US population ages and more patients undergo knee replacement, providers will need to be able to distinguish CRPS from postoperative inflammation and other causes of neuropathic pain. Therefore, there aim of this systematic review is to describe the incidence of CRPS after TKA and detail the presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of the condition in this specific population.

Methods

Search Strategy

This study was reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines (PRISMA-2020; PRISMA-NMA).[

11,

12] The protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251012765). The following Boolean phrases: ((Total knee arthroplasty) OR (TKA) OR (knee) OR (knee replacement)) AND ((((Complex regional pain syndrome) OR (reflex sympathetic dystrophy)) OR (Sudeck's atrophy)) OR (causalgia)) were applied to PubMed, Embase, Ovid/MEDLINE, and CENTRAL Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials between February 12 and March 25, 2025. We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished data. No time limit was applied.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies’ titles, abstracts, and main texts were sequentially assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria by SB and CE. Assessment was performed individually, and any disagreements were arbitrated between the two authors. Inclusion criteria were studies that reported on CRPS as a complication of primary TKA for the treatment of osteoarthritis. No limitation was made to minimum follow-up time and non-English articles were included in order to increase study power. No limit was set to the year of publication. Case reports were included due to the limited number of available studies. Exclusion criteria included: CRPS development in a knee but unrelated to TKA surgery, CRPS in a native knee, CRPS after revision TKA, CRPS development in a partial/unicompartmental TKA, reviews, meta-analyses, surgical technique reports, expert opinions, letters to editors, biomechanical reports, abstracts from scientific meetings, or unpublished reports. One study was excluded due to use of duplicate patient population.[

13]

Data Collection

All data was collected individually by SB and CE. Data sets were cross referenced between authors and any disagreements were arbitrated between the two authors. All cohort studies were individually assessed by SB and CE for methodological quality and risk of bias with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).[

14] All case reports were individually assessed for compliance to CARE guideline’s checklist of 30 requirements.[

15] GRADE criteria was used to assess certainty in the body of evidence for an outcome.[

16] Patient demographics, study details, symptoms, physical exam findings, diagnostic modalities, treatments, and outcomes were entered into Excel (2003, Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Results are reported as average with standard deviation or pooled proportional incidence. When extracting data for incorporation into supplemental tables, explicit mention of a finding was interpreted as a positive result. Explicit mention of no finding was interpreted as a negative result. Lack of mention was tabulated as no response (“ / ”). When calculating incidence for findings, explicit mention of a finding was interpreted as a positive result. Explicit mention of no finding or lack of mention was interpreted as a negative result.

Results

Study Characteristics and Demographics

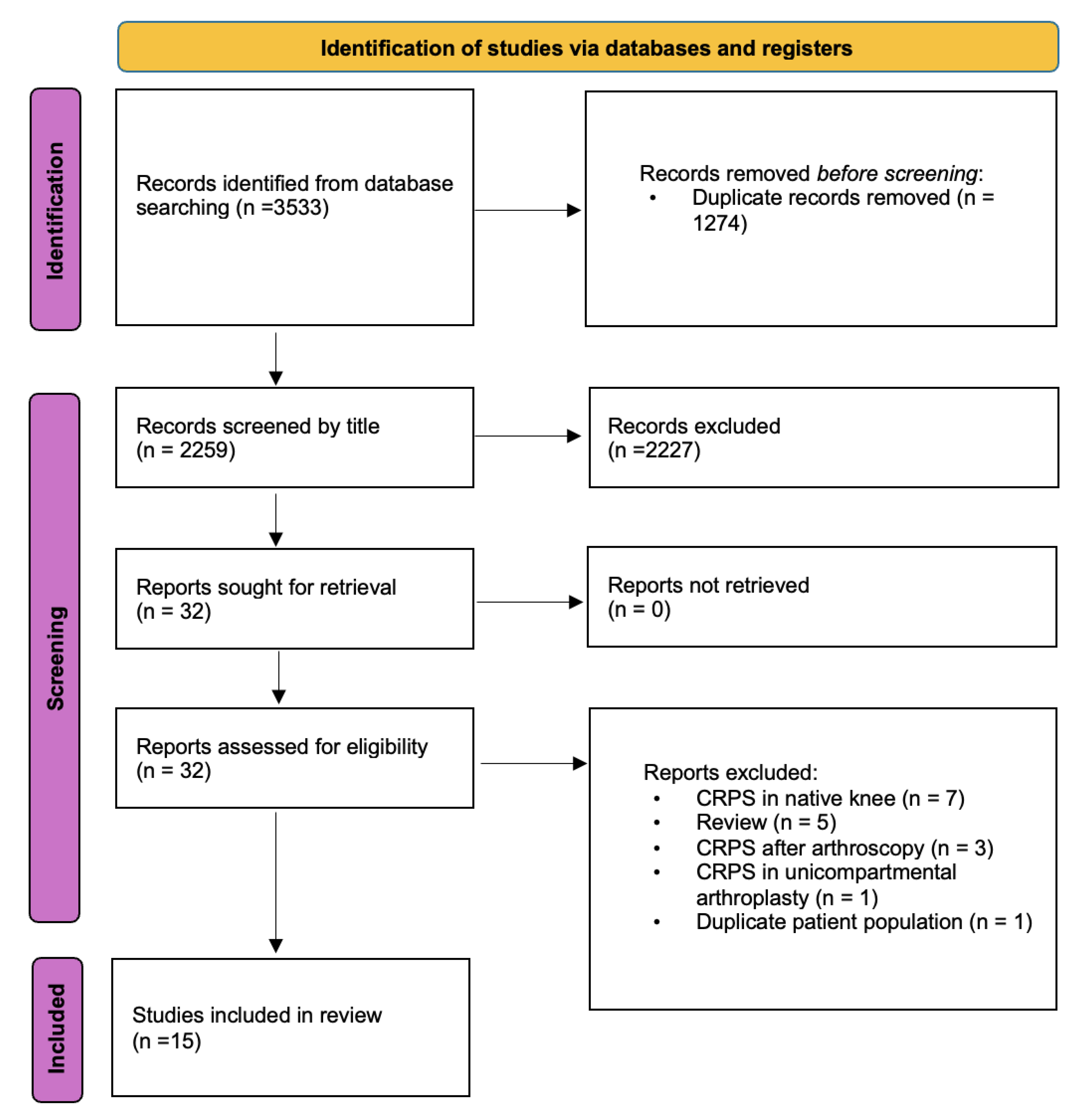

The methods and results of the study selection process are shown in

Figure 1. In total, 32 potential studies were assessed for eligibility, of which 15 articles published between 1985 and 2022 were included.[

13,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] These 15 studies consisted of 6 case reports, 2 case series, 4 prospective cohorts, and 3 retrospective cohort studies. Study characteristics and assessment are shown in

Table 1.[

13,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] The average Newcastle-Ottawa score for cohort studies was 8.7 out of 9. The average compliance to CARE guidelines was 28.5/30. The 15 studies totaled 125 CRPS TKAs with a mean age of 64

7 years and female-to-male ratio of 2:1.1. Mean follow up was 16.9

15.9 months and ranged from 1 to 120 months. The incidence of CRPS-affected TKAs was 2.8% (95% CI: 2.25% - 3.45%), after excluding all case reports and Cameron and O’Brien et al who did not report on total number of TKAs.[

20,

25] All studies described CRPS in the absence of nerve injury (CRPS-I) with the exception of Rommel et. al. who described CRPS-II secondary to injury of the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve.[

26]

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome.

Table 1.

Study evaluations and demographics. †Bruehl 2022 compared incidence at 6 weeks and 6 months; 6 months is shown here. ‡Patient sex calculated from Bruehl’s statement that “nearly 2/3 patients were female.” §Jacques et al follow up reported as 12 months minimum. (/) represents lack of reported value. NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. CARE, Case Report guidelines. TKA, total knee arthroplasty. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. IASP, international association for the study of pain.

Table 1.

Study evaluations and demographics. †Bruehl 2022 compared incidence at 6 weeks and 6 months; 6 months is shown here. ‡Patient sex calculated from Bruehl’s statement that “nearly 2/3 patients were female.” §Jacques et al follow up reported as 12 months minimum. (/) represents lack of reported value. NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. CARE, Case Report guidelines. TKA, total knee arthroplasty. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. IASP, international association for the study of pain.

| Author |

OCEBM Level of Evidence |

NOS Score |

CARE Score |

Number of TKAs |

Number of CRPS TKAs |

M/F |

Age (years) |

Incidence |

Diagnostic Criteria |

Follow up (months) |

| Bruehl 2022 |

Prospective cohort (III) |

9 |

/ |

110.0 |

14.0 |

F (9:5) ‡

|

/ |

12.7%†

|

2012 IASP |

6 |

| Burns 2006 |

Retrospective cohort (III) |

9 |

/ |

1280.0 |

8.0 |

F (6:2) |

68.0 |

0.6% |

2012 IASP |

46 (16-74) |

| Harden 2003 |

Prospective cohort (III) |

9 |

/ |

77.0 |

7.0 |

/ |

/ |

9.1% |

2012 IASP |

6 |

| Jacques 2021 |

Prospective cohort (III) |

9 |

/ |

469.0 |

46.0 |

/ |

/ |

9.8% |

Budapest Criteria + three-phase bone scintigraphy |

12§

|

| Kosy 2018 |

Prospective cohort (III) |

9 |

/ |

100.0 |

0.0 |

/ |

/ |

0.0% |

Budapest Criteria |

3 |

| Nielsen 1985 |

Retrospective cohort (III) |

8 |

/ |

247.0 |

3.0 |

/ |

/ |

1.2% |

/ |

24 |

| O'Brien 1995 |

Retrospective cohort (III) |

8 |

/ |

/ |

7.0 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

Pain + vasomotor + sympathetic block |

24 |

| Katz 1986 |

Case series (IV) |

/ |

28/30 |

662.0 |

5.0 |

F (4:1) |

57 (44-69) |

0.8% |

Pain + delayed functional recovery + knee stiffness + sympathetic block |

35 (18-45) |

| Braverman 1998 |

Case report (IV) |

/ |

29/30 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

F |

75.0 |

/ |

Pain + edema + vasomotor + knee stiffness |

1 |

| Cameron 1994 |

Case series (IV) |

/ |

29/30 |

/ |

29.0 |

F (17:12) |

63 (44-88) |

/ |

Pain + absence of overt sepsis or implant loosening |

/ |

| Rommel 2009 |

Case report (IV) |

/ |

26/30 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

F |

96.0 |

/ |

Pain + sensory impairment |

/ |

| Royeca 2019 |

Case report (IV) |

/ |

29/30 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

F |

69.0 |

/ |

Pain + altered cutaneous sensation + knee stiffness + absence of any mechanical issues with TKA |

5 |

| Sagoo 2021 |

Case report (IV) |

/ |

29/30 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

M |

38.0 |

/ |

Pain + autonomic changes + discoloration + edema + sympathetic block |

120 |

| Söylev 2016 |

Case report (IV) |

/ |

29/30 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

F |

67.0 |

/ |

Budapest Criteria |

12 |

| Urits 2019 |

Case report (IV) |

/ |

29/30 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

M |

71.0 |

/ |

Pain + preserved strength + absence of orthopedic aberrancy |

7 |

| TOTAL |

|

8.7 (avg) |

28.5 (avg) |

2951.0 |

125.0 |

F (20:11) |

647 (avg)

|

2.8% (avg) |

|

16.915.9 (avg)

|

Symptoms

A total of 11 studies totaling 69 CRPS TKAs were available for evaluation of patient symptoms.[

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] Symptom incidence is depicted in

Table 2 and expanded in

Supplemental Table S1. Average time from surgery to CRPS diagnosis was 7

3.4 months (95% CI: 6.28 – 7.72) (n=86). Hyperalgesia and allodynia were the most commonly reported symptom with an overall incidence of 62% (43/69) (95% CI: 50.9% - 73.8%) and 59% (41/69) (95% CI: 47.8% - 71.0%), respectively. The majority of pain was described by patients as ‘burning’, ‘numbness’, and ‘sharp’ sensation localized to the knee but not following any dermatome or myotome.[

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] There was no pattern to pain location; reports ranged from anterior,[

30,

31] to posterolateral,[

27] anterolateral,[

26] global, [

31] or involvement of the ankle or upper extremities.[

28,

29] Vasomotor symptoms, including skin temperature and color changes, were present in 37% (26/69) (95% CI: 26.2% - 49.1%) and 11% (8/69) (95% CI: 4.0% - 19.1%) of all CRPS TKAs. Sudomotor symptoms, including edema and sweating, were explicitly mentioned in 17% (95% CI: 8.4% - 26.3%) and 1.4% (95% CI: 0.0% - 11.3%) of all CRPS TKAs, respectively. Lastly, motor symptoms (defined as weakness, stiffness, or limitation of range of motion (ROM)) were seen in 32% (22/69) (95% CI: 20.9% - 42.9%) of cases while trophic changes were seen in 5.7% (4/69) (95% CI: 0.3% - 11.3%) of cases.

Table 2.

Symptoms and physical exam findings. Cumulative incidence is defined as number of positive findings divided by total number of CRPS TKA. Relative incidence is defined as number of positive findings divided by number of CRPS TKA that mention that finding (positive or negative). Motor symptoms reported as positive for either limited ROM or weakness. Trophic changes reported positive for hair or nail changes. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. TKA, total knee arthroplasty. ROM, range of motion.

Table 2.

Symptoms and physical exam findings. Cumulative incidence is defined as number of positive findings divided by total number of CRPS TKA. Relative incidence is defined as number of positive findings divided by number of CRPS TKA that mention that finding (positive or negative). Motor symptoms reported as positive for either limited ROM or weakness. Trophic changes reported positive for hair or nail changes. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. TKA, total knee arthroplasty. ROM, range of motion.

| |

Symptoms |

Physical Exam Findings |

| Category |

Symptom |

Incidence (cumulative) |

Incidence (relative) |

Finding |

Incidence (cumulative) |

Incidence (relative) |

| Pain |

Hyperalgesia |

62% (43/69) |

62% (43/69) |

|

|

|

| |

Allodynia |

59% (41/69) |

61% (41/67) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vasomotor |

Skin Temp |

37% (26/69) |

44% (26/59) |

Skin Temp |

50% (20/40) |

76.9% (20/26) |

| |

Color |

11% (8/69) |

26% (8/31) |

Color |

17.5% (7/40) |

22.6% (7/31) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sudomotor |

Edema |

17% (12/69) |

92% (12/13) |

Edema |

72.5% (29/40) |

85.3% (29/34) |

| |

Diaphoresis |

1.4% (1/69) |

1.8% (1/55) |

Diaphoresis |

0% (0/40) |

0% (0/21) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Motor |

Stiffness |

32% (22/69) |

96% (22/23) |

Change in ROM |

62.5% (25/40) |

78.1% (25/32) |

| |

|

|

|

Weakness |

22.5% (9/40) |

52.9% (9/17) |

| Trophic |

Trophic |

5.7% (4/69) |

7% (4/57) |

Trophic |

7.5% (3/40) |

15% (3/20) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Physical Exam Findings

Ten studies totaling 40 CRPS TKAs (32%) were available for evaluation of physical exam findings. [

17,

18,

19,

21,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] Edema was the most frequently reported finding (72.5%, 29/40), followed by knee stiffness/decreased ROM (62.5%, 25/40), and skin temperature changes (50%, 20/40).

(Table 2, Supplemental Table S2) Weakness was reported in 22.5% (9/40) of cases, compared to skin color changes 17.5% (7/40), and trophic changes 7.5% (3/40). Sweating was never described on physical exam. The average pre-operative ROM was 8.3°

3.4° extension (95% CI: 6.3° – 10.3°) to 109.8°

4° flexion (95% CI: 107.4° – 112.2°) (n=11). The average ROM at time of CRPS diagnosis was 3.5°

4.5° extension (95% CI: 1.3° – 5.7°) to 66.4°

16.2° flexion (95% CI: 58.5° – 74.3°) (n=16).

| Outcome |

Frequency |

Definition |

| Excellent |

25% (12/48) |

- -

“Complete and permanent relief of symptoms” (n=9, Cameron et al 1994) - -

Hungerford knee score > 90/100 (n=1, Katz et al 1989) - -

Completely asymptomatic (n=1, Soylev et al 2016) - -

“Complete resolution of symptoms and wean from opioids” (n=1, Urits et al 2019) |

| Good |

31% (15/48) |

- -

Mean KSS score reported within “good” reference range based on Munoz 2022 validation of KSS (n=8, Burns et al 2006) - -

“Complete and permanent relief of CRPS symptoms [but] continued patellofemoral aching with stairs” (n=3, Cameron et al 1994) - -

“Complete and permanent relief of CRPS symptoms [but] somewhat lax knee” (n=1, Cameron et al 1994) - -

Hungerford knee score 8089/100 (n=1, Katz et al 1989) - -

Hungerford knee score 8089/100 (n=1, Katz et al 1989) - -

“Significant relief of symptoms” (n=1, Rommel et al 2009) |

| Fair |

27% (13/48) |

- -

“Complete or partial relief that was not permanent” (n=12, Cameron et al 1994) - -

“Intermittent symptoms well managed with spinal cord stimulator and pain medications” (n=1, Sagoo et al 2021) |

| Poor |

17%

(8/48) |

- -

“Continued moderate pain with weightbearing” and active flexion of 80° (n=1, Braverman et al 1998) - -

“No relief at all” with sympathetic blocks, block could not be performed, final ROM flexion 80° (n=4, Cameron et al 1994) - -

Hungerford knee score < 70 (n=2, Katz et al 1989) - -

“Slight improvement in pain, continued to struggle with CRPS, regretted TKA” (n=1, Royeca et al 2019) |

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

Nine studies totaling 48 CRPS TKAs (38%) were available for evaluation of diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes.[

17,

19,

20,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]

(Supplemental Table S3). 7 CRPS TKA patients underwent diagnostic lumbar sympathetic block.[

17,

30,

31] Two cases utilized a bone scan, both of which revealed non-specific increased periprosthetic uptake.[

17,

28] Plain radiography identified periprosthetic osteopenia in one case,[

17] although several others showed no radiographic changes.[

26,

27,

29,

30,

31]

With regard to treatment, the most commonly employed modality was sympathetic block (75%, 36/48), followed by physical therapy (33%, 16/48), pharmacotherapy (27%, 13/48), and manipulation under anesthesia (25%, 12/48). A small minority of papers described use of sympathectomy or spinal stimulator (2%, 2/48).[

28,

30,

31] The average ROM at final follow-up was 3.4°

3.4° extension (95% CI: 1.5° – 5.3°) to 93.2°

7.9° flexion (95% CI: 88.7° – 97.7°) (n=12). A total of twelve patients underwent manipulation under anesthesia (MUA). We calculated an average increase in flexion of 29

(95% CI: 25.0

- 33.0

) after MUA (n=6). Outcomes varied from continued CRPS symptoms to complete resolution. A total of 33% (95% CI: 20.0% - 46.7%) (16/48) of patients were asymptomatic at final follow up.[

20,

29,

30,

31] The remainder of cases ranged from significant reduction of symptom, intermittent symptoms, moderate pain when weightbearing, to continued chronic pain and regret of TKA.

(Table 3)

Table 3.

Prognosis of CRPS after TKA. Excellent was defined as complete resolution of CRPS symptoms or qualifying knee score. Good was defined as significant improvement or qualifying knee score. Fair was defined as continued symptoms with partial improvement. Poor was defined as continuance of symptoms with minimal improvement and/or flexion < 90°, or qualifying knee score. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Table 3.

Prognosis of CRPS after TKA. Excellent was defined as complete resolution of CRPS symptoms or qualifying knee score. Good was defined as significant improvement or qualifying knee score. Fair was defined as continued symptoms with partial improvement. Poor was defined as continuance of symptoms with minimal improvement and/or flexion < 90°, or qualifying knee score. CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome. TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

| Outcome |

Frequency |

Definition |

| Excellent |

25% (12/48) |

- -

“Complete and permanent relief of symptoms” (n=9, Cameron et al 1994) - -

Hungerford knee score > 90/100 (n=1, Katz et al 1989) - -

Completely asymptomatic (n=1, Soylev et al 2016) - -

“Complete resolution of symptoms and wean from opioids” (n=1, Urits et al 2019) |

| Good |

31% (15/48) |

- -

Mean KSS score reported within “good” reference range based on Munoz 2022 validation of KSS (n=8, Burns et al 2006) - -

“Complete and permanent relief of CRPS symptoms [but] continued patellofemoral aching with stairs” (n=3, Cameron et al 1994) - -

“Complete and permanent relief of CRPS symptoms [but] somewhat lax knee” (n=1, Cameron et al 1994) - -

Hungerford knee score 8089/100 (n=1, Katz et al 1989) - -

Hungerford knee score 8089/100 (n=1, Katz et al 1989) - -

“Significant relief of symptoms” (n=1, Rommel et al 2009) |

| Fair |

27% (13/48) |

- -

“Complete or partial relief that was not permanent” (n=12, Cameron et al 1994) - -

“Intermittent symptoms well managed with spinal cord stimulator and pain medications” (n=1, Sagoo et al 2021) |

| Poor |

17%

(8/48) |

- -

“Continued moderate pain with weightbearing” and active flexion of 80° (n=1, Braverman et al 1998) - -

“No relief at all” with sympathetic blocks, block could not be performed, final ROM flexion 80° (n=4, Cameron et al 1994) - -

Hungerford knee score < 70 (n=2, Katz et al 1989) - -

“Slight improvement in pain, continued to struggle with CRPS, regretted TKA” (n=1, Royeca et al 2019) |

Discussion

CRPS is a rare and poorly understood cause of neuropathic pain after TKA. In this review the incidence of CRPS after TKA was 2.8%. We suggest the archetypical CRPS-TKA patient presents with disproportionate and unexplainable knee pain, describing burning and numbness sensation with stiffness, edema, and temperature asymmetry on exam. To our knowledge, this is the only systematic review of CRPS after TKA and the first to detail the incidence of the condition as well as extrapolate individual signs and symptoms and detail the efficacy of various treatments.

Incidence

The pooled incidence of CRPS after TKA was 2.8%. In comparison, other studies in this review reported incidences from 0.6% to 12%.[

18,

19] This variability may stem from a historical tendency to ascribe unexplained postoperative pain to CRPS. In 2007 the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Orlando Criteria was replaced by the more stringent Budapest Criteria that required multiple signs and symptoms with exclusion of other causes.[

32] As such, Kosy et al found that the incidence of CRPS after TKA declined from 8% to 0% with adoption of the Budapest Criteria.[

23] In this review, several studies diagnosed CRPS purely on presence of pain and lack of mechanical failure or infection.[

20,

26,

30]

(Table 1) CRPS incidence may also be time-dependent. The Budapest Criteria has no time component and many CRPS symptoms overlap with those of postoperative inflammation. As such, some studies have shown that the incidence of CRPS after TKA declines from 6 weeks to 6 months postoperatively.[

18]

,[

21] During this period, similar rates of edema and temperature asymmetry are observed between CRPS and non-CRPS TKA patients.[

21]

Despite significant variability, our calculated incidence is still lower than that for carpal tunnel (8.3% - 10.4%)[

5,

6] and foot/ankle surgery (4.4%).[

7] However, despite its lower reported incidence, TKA may intrinsically carry a higher risk for CRPS development due to multiple factors. TKA involves extensive bone and soft tissue destruction, often with PCL sacrifice, resulting in greater inflammatory and nociceptor load.[

33,

34] Additionally, the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve is typically cut during TKA, and postoperative mobility is significantly reduced. Furthermore, a majority of TKA patients are post-menopausal women,[

35] a demographic already at increased risk for CRPS. Given that immobilization, soft tissue and bone trauma, nerve injury, and female sex are all independent risk factors for CRPS, the true incidence in the TKA population may be underestimated.[

36]

Diagnosis

CRPS may be underdiagnosed after TKA due to diagnostic difficulty and overlapping symptoms with post-operative inflammation and other conditions

(Table 4). From this review, persistent edema was the most characteristic sign of CRPS. Harden et al. found the most distinguishing signs to be edema, color changes, and hyperalgesia/allodynia by 6 months,[

21] while Bruehl et al.’s reported edema, temperature changes, and motor changes.[

18] Compared to non-CRPS TKAs with persistent pain, CRPS patients also self-report greater levels of depression and anxiety at one and six months postoperatively, respectively.[

21]

Diagnostic sympathetic block can be a useful adjunct to clinical signs and symptoms.[

37] From this review, 7 CRPS TKA patients underwent diagnostic sympathetic block. All 7 patients had a positive diagnostic result, defined as transient relief of symptoms with rise in skin temperature. Katz et. al.’s patients underwent sympathetic block at 7 months from surgery and 2 months from time of CRPS suspicion.[

31]

There is limited need for radiography or scintigraphy. CRPS can exhibit radiological subchondral osteopenia in the patella.[

37]

,[

38,

39] However, these findings are inconsistent and can be difficult to interpret after TKA.[

13] As such, only one case demonstrated periprosthetic osteopenia,[

17] with many others showing no radiographic changes.[

26,

27,

29,

30,

31] Several studies have reported 80% sensitivity and 72% specificity of scintigraphy for CRPS of the knee.[

40]

,[

41] Katz et. al. reported only 61% of CRPS TKAs had positive bone scans.[

13] However, interpretation remains difficult due to concurrent TKA prosthesis uptake.[

31] Lastly, thermography is often employed as a supplementary test to support the clinical diagnosis of CRPS due to its relatively high sensitivity (76%) and specificity (93%).[

37,

42] However, no studies in this review used thermography.

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis of CRPS after TKA.

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis of CRPS after TKA.

| Differential Diagnosis for TKA Complicated with CRPS |

| Intraarticular Causes |

Extraarticular Causes |

|

|

Treatment

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary focus on preventing symptom progression, limiting pain, and preventing knee stiffness.[

32,

43] Physical therapy (PT) is considered first line to help patients overcome their fear of pain and movement, while controlling edema, reestablishing voluntary motor control, and preventing postoperative stiffness. Soylev and Braverman found success with therapy focused on desensitization.[

29]

,[

17] Burns et al. found success by having the patient temporarily cease PT to focus on knee extension for 2-4 months to prevent flexion contracture, after which they resumed formal PT and focused on flexion.[

19] Royeca et. al.’s patient was unable to tolerate physical therapy due to pain.[

27] As such, analgesic support is often needed to aid in PT compliance, with several papers using NSAIDs, opioids, or epidural catheters.[

44]

Manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) may be indicated in patients who fail physical therapy and/or develop residual knee stiffness. CRPS patients require MUA more often than non-CRPS patients.[

19] In this review, 23% (11/48) of patients required MUA, although this number is likely low given the skewed contribution from Cameron et. al.[

20] MUA appears to have favorable outcomes in the CRPS TKA. We calculated an average increase in flexion of 29

(n=6) after MUA. In comparison, non-CRPS patients tend to gain an average of 32

flexion.[

45] However, several factors should be considered. First, multiple manipulations may be required. A total of 80% of Katz et. al.’s MUA patients required multiple manipulations.[

31] Second, special considerations should be given to timing, as delaying MUA past three months can preclude adequate ROM.[

45] In this review, 3 CRPS TKAs underwent MUA within the first month after surgery. Another was manipulated at 3 and 5 months. However, the benefit of MUA should be weighed against the risks of pain exacerbation and CRPS relapse. To circumvent this problem, several studies used epidural catheters for pain control or waited for a quiescent phase of CRPS to perform MUA. [

19,

39]

Sympathetic blockade had variable results. A total of 42% (15/36) of patients in this review continued to describe symptoms and functional limitations after therapeutic block. Sympathetic block timing is important. Katz et al reported favorable results with blocks performed within one year of symptom onset.[

13] In this review, 5 patients received blocks within the first 2 months of surgery while 29 received blocks every 4-6 weeks until relief was obtained. The large majority of patients in this review also required multiple blocks. Five patients required 3 blocks, while the majority of Cameron et al’s 29 cases required 3 blocks, with average of 1.8 blocks needed for complete relief.[

20] Another study of CRPS in the knee reported an average of 9 blocks were required per patient.[

25]

There are several last resort measures for patients with refractory CRPS. Katz et al. described two patients who found success with lumbar sympathectomy.[

31] Another study found 65% (15/23) of patients with CRPS of the knee had at least 75% relief of pain.[

13] Neurostimulation is another option, as Urits et al. described complete pain resolution with use of a spinal cord stimulator.[

30] Sagoo et al. also reported use of a spinal cord stimulator after a series of lumbar sympathetic blocks; at long term follow up they reported well managed, but intermittent, CRPS symptoms.[

28] Furthermore, dorsal root ganglion and peripheral nerve stimulation are other options that have found success in CRPS.[

46] Lastly, ketamine infusions have shown promise in managing refractory CRPS pain.[

47] However, these treatments have not been described in the literature for CRPS after TKA and further studies will be needed to determine their effectiveness in this population.

The limitations of this review are low level of evidence of included studies with a predominance of case series/studies. There is also a risk of bias due to missing results. For example, certain diagnostic and treatment modalities are likely underreported (e.g. physical therapy) due to underlying assumptions regarding the standard therapeutic/diagnostic workup for a persistently painful TKA. Other limitations include lack of consistent reporting of symptoms and physical exam findings, and inconsistences in follow up and reporting. Bias is also likely present due to heterogeneity in study design and diagnostic criteria, as well as a probable tendency of case-based reports to overrepresent severe or atypical presentations. As such, each outcome received a GRADE rating of ‘very low’ certainty in evidence with the exception of incidence which received a rating of ‘low’. Further high quality and long-term studies will be needed to help elucidate the impact of certain therapies on outcomes.

Conclusions

This review highlights the limited but emerging body of evidence for CRPS after knee replacement. Pooled data among included studies demonstrate an incidence of 2.8%, lower than that reported after other operations. Given TKA is associated with many risk factors for post-surgical CRPS, this study highlights CRPS may be an underrecognized cause of persistent neuropathic pain after TKA. Persistent edema, color and temperature changes, and sensory disturbances are the most distinguishing features of CRPS in this patient population. There is some evidence for the therapeutic use of manipulation under anesthesia and sympathetic blocks, although higher-level studies will be needed to guide diagnosis and treatment in this unique patient population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Eldufani, J.; Elahmer, N.; Blaise, G. A medical mystery of complex regional pain syndrome. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, N.R.; Bruehl, S.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; Birklein, F.; Marinus, J.; Maihofner, C.; Lubenow, T.; Buvanendran, A.; Mackey, S.; Graciosa, J.; et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the "Budapest Criteria") for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain 2010, 150, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.; Maihöfner, C. Signs and Symptoms in 1,043 Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J Pain 2018, 19, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, K.; Trunzter, J.; Wu, E.; Barnes, J.; Eppler, S.L.; Kamal, R.N. National Trends in the Diagnosis of CRPS after Open and Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release. J Wrist Surg 2019, 8, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, V.V.; de Oliveira, S.B.; Fernandes, M.o.C.; Saraiva, R. Incidence of regional pain syndrome after carpal tunnel release. Is there a correlation with the anesthetic technique? Rev Bras Anestesiol 2011, 61, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, M.; Schulz, S.; Kasdan, M.; Wilhelmi, B.J. The Incidence of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome in Simultaneous Surgical Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Dupuytren Contracture. Hand (N Y) 2018, 13, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewhorn, M.J.; Leung, A.H.; Gillespie, A.; Moir, J.S.; Miller, R. Incidence of complex regional pain syndrome after foot and ankle surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg 2014, 53, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichmüller, K.; Rose, N.; Dreiling, J.; Schwarzkopf, D.; Meißner, W.; Rittner, H.L.; Kindl, G. Incidence and treatment of complex regional pain syndrome after surgery: analysis of claims data from Germany. Pain Rep 2024, 9, e1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, H.; Boljanovic, D.; Wright, S.; Murnaghan, J.; Holtby, R. Association between Neuropathic Pain and Reported Disability after Total Knee Arthroplasty. Physiother Can 2015, 67, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beswick, A.D.; Wylde, V.; Gooberman-Hill, R.; Blom, A.; Dieppe, P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Salanti, G.; Caldwell, D.M.; Chaimani, A.; Schmid, C.H.; Cameron, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Straus, S.; Thorlund, K.; Jansen, J.P.; et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015, 162, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, M.M.; Hungerford, D.S. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy affecting the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987, 69, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O'Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2021.

- Gagnier, J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D. The CARE Guidelines: Consensus-based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline Development. the CARE Group.

- ACIP GRADE Handbook for Developing Evidence-based Recommendations Center for Disease Control, 2024.

- Braverman, D.L.; Kern, H.B.; Nagler, W. Recurrent spontaneous hemarthrosis associated with reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998, 79, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruehl, S.; Billings, F.T.; Anderson, S.; Polkowski, G.; Shinar, A.; Schildcrout, J.; Shi, Y.; Milne, G.; Dematteo, A.; Mishra, P.; et al. Preoperative Predictors of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Outcomes in the 6 Months Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Pain 2022, 23, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.W.; Parker, D.A.; Coolican, M.R.; Rajaratnam, K. Complex regional pain syndrome complicating total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2006, 14, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, H.U.; Park, Y.S.; Krestow, M. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy following total knee replacement. Contemp Orthop 1994, 29, 279–281. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, N.R.; Bruehl, S.; Stanos, S.; Brander, V.; Chung, O.Y.; Saltz, S.; Adams, A.; Stulberg, D.S. Prospective examination of pain-related and psychological predictors of CRPS-like phenomena following total knee arthroplasty: a preliminary study. Pain 2003, 106, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, H.; Jérôme, V.; Antoine, C.; Lucile, S.; Valérie, D.; Amandine, L.; Theofylaktos, K.; Olivier, B. Prospective randomized study of the vitamin C effect on pain and complex pain regional syndrome after total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2021, 45, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosy, J.D.; Middleton, S.W.F.; Bradley, B.M.; Stroud, R.M.; Phillips, J.R.A.; Toms, A.D. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome after Total Knee Arthroplasty is Rare and Misdiagnosis Potentially Hazardous-Prospective Study of the New Diagnostic Criteria in 100 Patients with No Cases Identified. J Knee Surg 2018, 31, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Hvid, I.; Sneppen, O. Total condylar knee arthroplasty. A report of 2-year follow-up on 247 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (1978) 1985, 104, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, S.J.; Ngeow, J.; Gibney, M.A.; Warren, R.F.; Fealy, S. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the knee. Causes, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Sports Med 1995, 23, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rommel, O.; Finger, L.; Bös, E.; Eichbaum, A.; Jäger, G. [Neuropathic pain following lesions of the infrapatellar branch of the femoral nerve : an important differential diagnosis in anterior knee pain]. Schmerz 2009, 23, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royeca, J.M.; Cunningham, C.M.; Pandit, H.; King, S.W. Complex regional pain syndrome as a result of total knee arthroplasty: A case report and review of literature. Case Rep Womens Health 2019, 23, e00136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagoo, N.S.; Sharma, R.; Alaraj, S.; Sharma, I.K.; Bruntz, A.J.; Bajaj, G.S. Metal Hypersensitivity and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome After Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söylev, G.; Boya, H. A rare complication of total knee arthroplasty: Type l complex regional pain syndrome of the foot and ankle. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2016, 50, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urits, I.; Osman, M.; Orhurhu, V.; Viswanath, O.; Kaye, A.D.; Simopoulos, T.; Yazdi, C. A Case Study of Combined Perception-Based and Perception-Free Spinal Cord Stimulator Therapy for the Management of Persistent Pain after a Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain Ther 2019, 8, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.M.; Hungerford, D.S.; Krackow, K.A.; Lennox, D.W. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy as a cause of poor results after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1986, 1, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.S.; Noor, N.; Urits, I.; Paladini, A.; Sadhu, M.S.; Gibb, C.; Carlson, T.; Myrcik, D.; Varrassi, G.; Viswanath, O. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther 2021, 10, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, T.; Iwasaki, K.; Matsuoka, M.; Morioka, Y.; Matsubara, S.; Kondo, E.; Iwasaki, N. The alterations in nerve growth factor concentration in plasma and synovial fluid before and after total knee arthroplasty. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.Z.; Bolognesi, M.P.; Bhavsar, N.A.; Penrose, C.T.; Horn, M.E. Chronic Pain Prevalence and Factors Associated With High Impact Chronic Pain following Total Joint Arthroplasty: An Observational Study. J Pain 2022, 23, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, M.I. Sex differences in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2007, 15 Suppl 1, S22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, T.; Shipton, E.A.; Williman, J.; Mulder, R.T. Potential risk factors for the onset of complex regional pain syndrome type 1: a systematic literature review. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2015, 2015, 956539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, G.S.; Hussein, R.; Khanduja, V.; Ordman, A.J. Complex regional pain syndrome with special emphasis on the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007, 89, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.J.; Hurwitz, S.R. Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome of the lower extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2002, 10, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, D.E.; DeLee, J.C. Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy of the Knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1994, 2, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.W.; Paeng, J.C.; Nahm, F.S.; Kim, S.G.; Zehra, T.; Oh, S.W.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, K.W.; Chung, J.K.; Lee, M.C.; et al. Diagnostic performance of three-phase bone scan for complex regional pain syndrome type 1 with optimally modified image criteria. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011, 45, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringer, R.; Wertli, M.; Bachmann, L.M.; Buck, F.M.; Brunner, F. Concordance of qualitative bone scintigraphy results with presence of clinical complex regional pain syndrome 1: meta-analysis of test accuracy studies. Eur J Pain 2012, 16, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasner, G.; Schattschneider, J.; Baron, R. Skin temperature side differences--a diagnostic tool for CRPS? Pain 2002, 98, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S.; Kellett, S.; McCullough, R.; Tapper, A.; Tyler, C.; Viner, M.; Palmer, S. Body Perception Disturbance and Pain Reduction in Longstanding Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Following a Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Program. Pain Med 2019, 20, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.E.; DeLee, J.C.; Ramamurthy, S. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy of the knee. Treatment using continuous epidural anesthesia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989, 71, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Razick, D.; Seibel, A.; Asad, S.; Shekhar, A.; Shelton, T. Outcomes of Early Versus Delayed Manipulation Under Anesthesia for Stiffness Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Arthroplasty 2024, 10.1016/j.arth.2024.05.059, doi:10.1016/j.arth.2024.05.059.

- Chmiela, M.A.; Hendrickson, M.; Hale, J.; Liang, C.; Telefus, P.; Sagir, A.; Stanton-Hicks, M. Direct Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A 30-Year Review. Neuromodulation 2021, 24, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitneni, A.; Patil, A.; Dalal, S.; Ghorayeb, J.H.; Pham, Y.N.; Grigoropoulos, G. Use of Ketamine Infusions for Treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e18910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).