1. Introduction

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is a well-established surgical procedure for treating unicompartmental osteoarthritis (OA), offering a less invasive alternative to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with generally favorable outcomes. [

1,

2,

3,

4] However, a certain proportion of UKA patients experience persistent postoperative pain and discomfort, even in the absence of clear radiographic abnormalities or mechanical complications. [

5,

6,

7] Among all revision cases, the proportion of revisions performed due to unexplained pain was higher after UKA (23%) than TKA (9%), raising concerns about factors influencing postoperative pain perception. [

5]

Recent research has explored the role of central sensitization (CS) in persistent pain following joint arthroplasty. [

8,

9,

10] CS is a condition characterized by an exaggerated pain response due to alterations in central nervous system processing. [

8,

9,

10] It is mediated by neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine and leads to increased sensitivity to pain stimuli, lowered pain thresholds, and prolonged pain perception even after the initial source of pain has been resolved. [

8,

9,

10] Patients with CS often report widespread pain, hyperalgesia, and allodynia, which can significantly affect their recovery following orthopedic procedures. [

8,

9,

10]

Previous studies have established a link between CS and poor outcomes following TKA. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] Patients with high preoperative pain levels and low pain thresholds are more likely than others to experience severe postoperative pain and dissatisfaction, despite successful surgical intervention. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] However, the role of CS in UKA remains relatively underexplored. Given that UKA is a less invasive procedure that preserves the surrounding soft tissues, it might be assumed that patients would experience less postoperative pain than TKA patients. [

3] Persistent pain in a subset of UKA patients suggests that factors beyond structural abnormalities could be contributing to suboptimal outcomes. [

7]

Understanding the association between CS and postoperative pain in UKA patients is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Identifying patients with preoperative CS could allow for the implementation of targeted perioperative strategies to mitigate its effects. This study elucidates the relationship between preoperative CS and postoperative pain and dissatisfaction following UKA.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a retrospective cohort design to evaluate the effects of CS on postoperative outcomes following UKA. The study was conducted at a single tertiary medical center, and all procedures were performed by a single experienced orthopedic surgeon to minimize variability in surgical technique. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation.

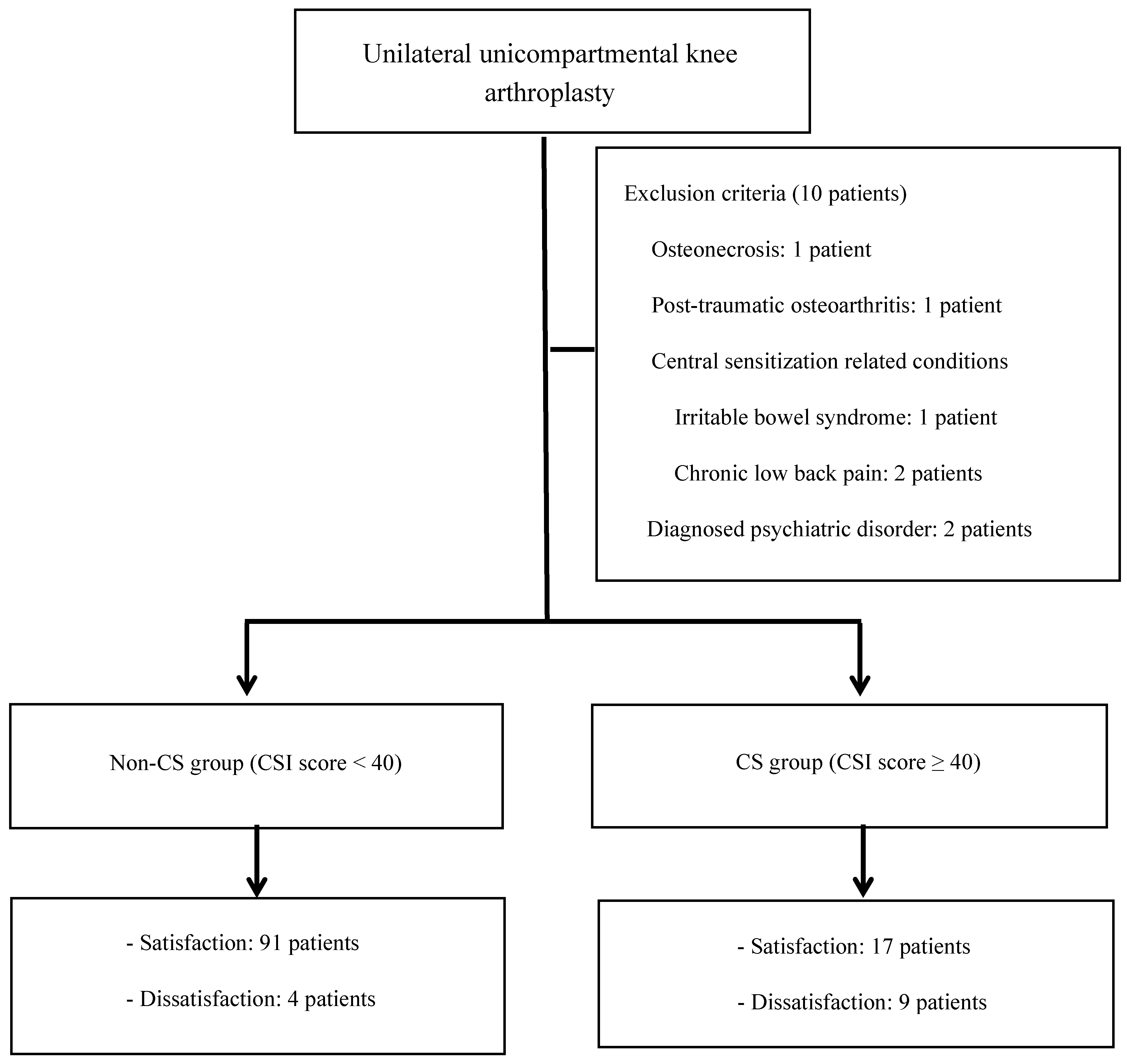

Data from 131 patients who underwent unilateral UKA between 2014 and 2022 were initially included in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) isolated medial compartment OA with an intact anterior cruciate ligament, 2) correctable varus deformity (less than 10 degrees), 3) minimum two-year follow-up period, and 4) no history of prior knee surgery on the affected side. Patients were excluded if they had: inflammatory arthritis (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), osteonecrosis affecting the knee joint (1 patient), post-traumatic OA (1 patient), a history of knee infection, a documented history of CS-related conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (1 patient) and chronic low back pain (2 patients), prior use of centrally acting agents or a diagnosed psychiatric disorder that could influence CS (2 patients), incomplete clinical outcome data (2 patients), or a subsequent operation on either knee during the follow-up period (1 patient). Following the application of those criteria, 10 patients were excluded from the study, resulting in a final cohort of 121 patients (

Figure 1). Patient demographics and baseline characteristics, including body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and preoperative functional status, were collected through medical records and patient-reported questionnaires.

CS; Central Sensitization, CSI: Central Sensitization Inventory.

The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI) is commonly used to assess CS and offers significant practical benefits in clinical settings. [

17,

18] The CSI is a validated self-reported questionnaire designed to evaluate symptoms associated with CS. Unlike quantitative sensory testing (QST), which objectively measures sensory responses to external stimuli, the CSI focuses on subjective symptom assessment. [

17,

18]

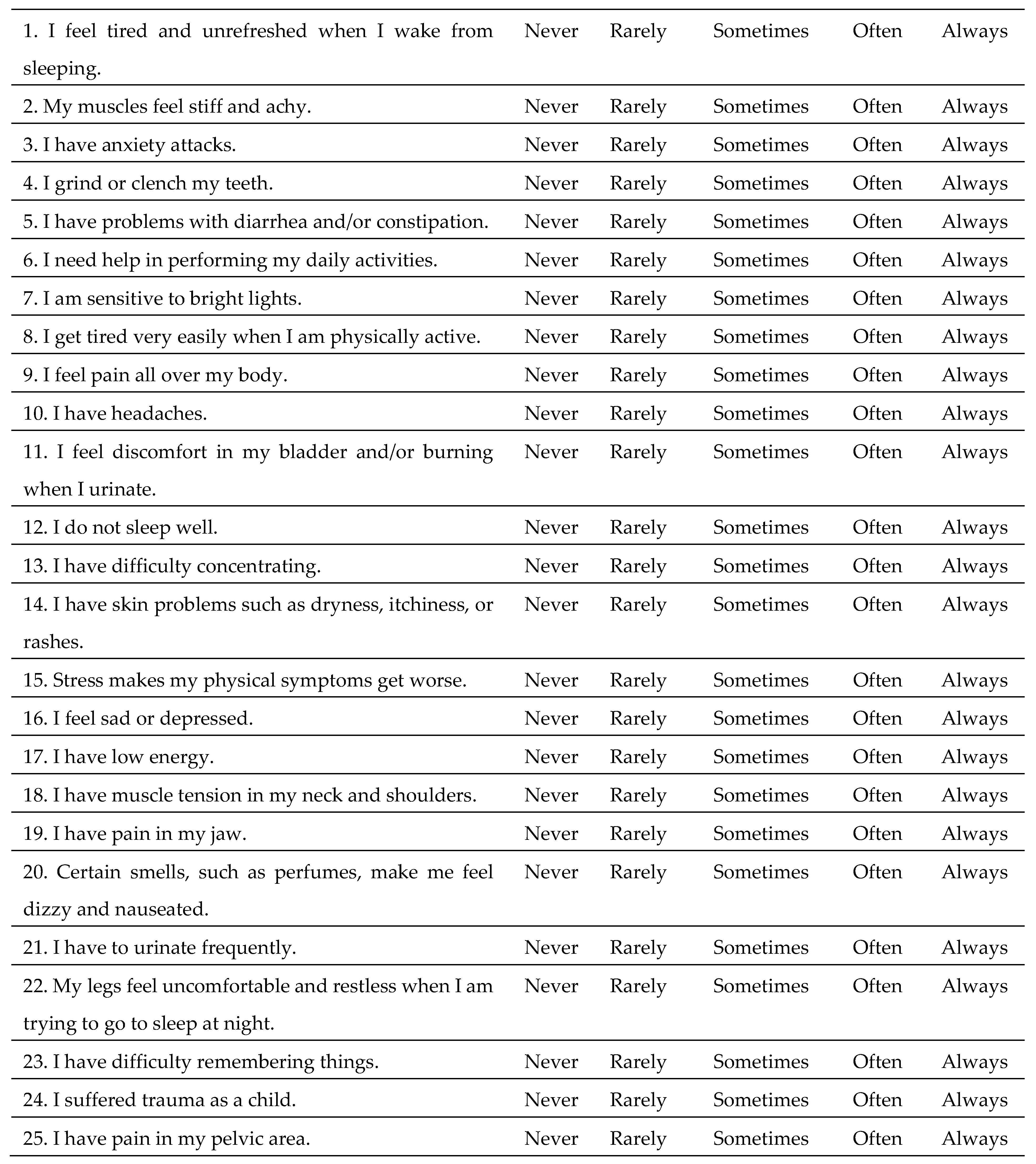

The CSI questionnaire consists of 25 items that capture a broad spectrum of somatic and emotional symptoms frequently observed in individuals with CS. [

17,

18] These include headaches, fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive difficulties, and psychological distress, as well as heightened pain sensitivity that can interfere with daily life. The CSI specifically evaluates the presence of unrefreshing sleep, muscle stiffness and pain, anxiety attacks, bruxism, gastrointestinal disturbances (diarrhea/constipation), difficulty daily activities, light sensitivity, physical fatigue, widespread pain, urinary discomfort, poor sleep quality, concentration issues, skin problems, stress-related physical symptoms, depression, low energy, muscle tension in the neck and shoulders, jaw pain, dizziness or nausea triggered by certain smells, frequent urination, restless legs, memory impairment, childhood trauma, and pelvic pain. [

17,

18]

Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always), with a total possible score of 0 to 100. According to Neblett et al. [

18], a score of 40 or higher suggests the presence of CS. The CSI is easy to administer, takes less than 10 minutes to complete, and does not require specialized equipment. Additionally, because it incorporates non-painful and hypothetical scenarios, it avoids ethical concerns associated with other assessment methods. These advantages make the CSI a highly useful tool for evaluating the severity of CS-related symptoms. It is widely recognized as a reliable and validated measure for quantifying CS symptom severity [

17,

18] (

Figure 2).

All UKA procedures were performed by a single surgeon using a standardized minimally invasive approach. The same cemented, mobile-bearing (MB) UKA system (Microplasty Oxford MB UKA, Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA) was used in all cases to ensure consistency across patients. All operations were performed under general anesthesia through the mini-medial parapatellar approach. A pneumatic tourniquet that inflated to 300 mmHg was applied. The medial meniscus was resected, and the osteophytes of the medial femoral condyle and tibial plateau were carefully removed. With the Microplasty Oxford MB UKA system, the femoral gap-sizing spoons and G-clamp were used to assess the femoral component size, tibial cutting depth, and orientation. After determining the size of the medial femoral condyle (MFC) and evaluating the gap between the femur and tibia using a series of femoral sizing spoons, the most suitable spoon was selected and positioned on the MFC. After securing the gap-sizing spoon to the tibial resection guide with the G-clamp, the guide was aligned parallel to the long axis of the tibia in both the coronal and sagittal planes. The tibia was then resected, and an intramedullary (IM) rod with a distal linking feature was inserted into the femoral canal until fully seated. With the IM link engaged, the femoral drill guide was positioned on the tibial cut surface to determine the femoral component position. A posterior femoral condylar cut was done along the femoral cutting guide. Subsequently, distal femoral milling was carefully performed to balance the flexion and extension gaps without ligament release. Cement fixation was used for all femoral and tibial components. A compressive bandage was applied postoperatively. Patients were allowed full weight-bearing on postoperative day 1 with the assistance of a walker, and a structured physical therapy program was initiated to optimize range of motion and quadriceps strengthening. The same preemptive multimodal analgesic regimen was applied to all patients. Postoperatively, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia, programmed to deliver 1 mL of a 100-mL solution containing 2000 μg of fentanyl, was used. Once the patients restarted oral intake, they received 10 mg of oxycodone every 12 hours for one week, along with 200 mg of celecoxib, 37.5 mg of tramadol, and 650 mg of acetaminophen every 12 hours for six weeks. Subsequent visits were scheduled at two weeks, six weeks, three months, six months, and one year, with yearly visits thereafter.

Postoperative outcomes were assessed at baseline and two years using validated patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). Pain, stiffness, and function were evaluated using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), a well-established tool for assessing clinically relevant outcomes in patients undergoing treatment for OA of the hip or knee. [

19] Additionally, joint awareness during daily activities was measured using the Forgotten Joint Score (FJS), which has been validated as a key indicator of successful joint arthroplasty. [

20] To assess patient satisfaction, the new Knee Society Satisfaction (KSS) score, a five-item questionnaire designed to evaluate satisfaction with daily activities, was used. Patients were categorized as satisfied (total score 21–40) or dissatisfied (0–20), following the scoring system developed by Noble et al. [

21] In addition to PROMs, postoperative complications—infection, implant loosening, and the need for revision surgery—were systematically recorded to provide a comprehensive evaluation of surgical outcomes.

3. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean and standard deviation. Data were compared between the non-CS group (preoperative CSI score < 40) and the CS group (preoperative CSI score ≥ 40). Continuous variables were analyzed using independent t-tests, and categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests. Patient demographics and surgical characteristics were collected as dependent variables to identify risk factors for patient dissatisfaction. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate associated factors, using a backward elimination approach to retain significant predictors of postoperative dissatisfaction following UKA. Odds ratios were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® for Windows v21.0, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

4. Results

The final cohort comprised 121 patients who underwent UKA and met the inclusion criteria. Patients were stratified into two groups based on their preoperative CSI scores: 95 patients (78.5%) had CSI scores below 40 (non-CS group), and 26 patients (21.5%) had CSI scores of 40 or higher (CS group). The two groups did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics or surgical factors, except for CSI scores (

Table 1).

Preoperative WOMAC subscores differed significantly between the groups (p < 0.05). Before surgery, WOMAC pain, function, and total scores were significantly worse in the CS group than the non-CS group, indicating worse baseline symptoms (all p < 0.05).

In both groups, all WOMAC subscores (pain, function, and total scores) showed significant improvements postoperatively, compared with the preoperative values (all p < 0.05) (

Table 2). However, the mean postoperative WOMAC pain score was still higher in the CS group than the non-CS group (7.8 vs. 1.8, respectively, p < 0.001) 2 years postoperatively. Similarly, the postoperative total WOMAC score was significantly higher in the CS group than the non-CS group (30.5 vs. 12.8, respectively, p < 0.001). The improvement in preoperative to postoperative WOMAC subscores (pain, function, and total) was significantly greater in the non-CS group than the CS group (all p < 0.05) (

Table 2).

The FJS, which evaluates joint awareness during daily activities, was significantly lower in the CS group than in the non-CS group (64.4 vs. 72.7, respectively, p = 0.005). This finding suggests that patients with CS were more likely than those without CS to be aware of their knee joint postoperatively (

Table 3).

The new KSS score was 33.1 in the non-CS group and 25.5 in the CS group (p < 0.001). Among non-CS group patients, 91 (95.8%) were satisfied with their UKAs, whereas only 17 (65.4%) patients in the CS group reported satisfaction with the surgery (p < 0.001). Satisfaction in the CS group was thus significantly lower than in the non-CS group, not only for light daily activities such as sitting, lying in bed, and getting out of bed, but also for physically demanding tasks such as household chores and recreational or leisure activities (all p < 0.05) (

Table 4).

The multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that patients with a CSI score ≥ 40 had an 11.349-fold increased likelihood of dissatisfaction after UKA (95% CI: 2.315 – 55.626, p = 0.003), compared with patients with a CSI score < 40. The associations remained statistically significant after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists grade, preoperative flexion contracture and further flexion, preoperative hip-knee-ankle angle, and preoperative WOMAC total scores. No patient in either group experienced complications requiring additional surgery or revision during the follow-up period.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the significant role that CS plays in postoperative pain and dissatisfaction following UKA. Patients with preoperative CS, identified as a CSI score of 40 or higher, demonstrated significantly worse postoperative pain scores, increased joint awareness, and inferior functional outcomes compared with those without CS. These results provide valuable insights into the influence of preoperative pain processing mechanisms on surgical recovery and patient satisfaction.

Patients with preoperative CS experienced significantly worse postoperative pain and functional outcomes than those without CS, despite the theoretical advantages of UKA over TKA, such as a smaller incision, preservation of most soft tissues, and less bone resection. [

3] Our findings reveal that the CS group reported notably higher pain scores two years postoperatively. No previous studies investigated the effects of preoperative CS on UKA outcomes. However, numerous studies have examined the relationship between preoperative CS and clinical outcomes following TKA [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

22,

23], and the evidence suggests that patients with preoperative CS are at greater risk than those without CS for chronic postoperative pain. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

22,

23] Martinez et al. [

23] found that TKA patients with heat hyperalgesia reported greater pain both before and after surgery and required higher doses of postoperative morphine. Similarly, Lundblad et al. [

22] followed 69 patients for 18 months after TKA and noted that persistent pain was more prevalent among those with high preoperative pain levels and a lower pain threshold—both indicative of CS-related mechanisms. In another study, Kim et al. [

13] reported that patients with a high CSI score (≥40) experienced more intense postoperative pain and required greater analgesic use during the first three months postoperatively. Their study also demonstrated that higher CSI scores were associated with more severe preoperative pain, persistent postoperative pain, and lower satisfaction with pain relief three months after surgery. Interestingly, although UKA is designed to preserve native ligaments and provide more natural knee kinematics, patients with CS did not appear to benefit from those advantages [

3]. Instead, they continued to experience significant pain and functional limitations. This suggests that in CS patients, abnormalities in pain processing play a more important role in postoperative recovery than the specific surgical technique used. These findings further support the hypothesis that postoperative pain perception is not solely dictated by structural changes but is also influenced by alterations in central nervous system pain processing.

Preoperative CS not only contributes to persistent pain following surgery but also significantly affects functional outcomes and overall patient satisfaction. In our study, the CS group exhibited poorer WOMAC function and total scores than the non-CS group at the two-year follow-up visit. Additionally, the FJS scores were notably lower in the CS group, indicating a greater level of functional impairment. These findings align with previous studies of TKA. [

12,

14] Kim et al. [

12] reported that the CS group showed significantly inferior preoperative and postoperative WOMAC function and total scores than the non-CS group. Similarly, Koh et al. [

14] found that the CS group experienced worse quality of life and greater functional disability than the non-CS group after TKA. In addition, one of the most striking findings of our study is the significant effect of CS on patient satisfaction following UKA. Whereas 88% of patients in the non-CS group reported being satisfied with their surgical outcomes, only 62% of those in the CS group expressed satisfaction (p < 0.01). Sasaki et al. [

16] demonstrated that preoperative CS was also negatively associated with postoperative EQ-5D scores in TKA patients. Moreover, Koh et al. [

14], using the same new KSS score as in our study, showed that patients in the CS group were significantly more dissatisfied than those in the non-CS group. Further supporting this, our multivariate regression analysis identified CS as a significant predictor of dissatisfaction. The preoperative CSI score (adjust odds ratio = 11.349, p = 0.003) was independently associated with lower satisfaction rates. These findings underscore the critical need to address CS preoperatively because doing so could significantly enhance patient satisfaction following UKA.

CS is strongly associated with poor clinical outcomes following UKA for several reasons. First, patients with CS often have higher preoperative expectations than those without CS. Specifically, they anticipate greater pain relief and psychological well-being after surgery. [

24] Although high expectations can sometimes contribute to favorable postoperative outcomes [

25], excessively high expectations are closely linked to dissatisfaction and poor clinical results. [

26] Second, the heightened pain sensitivity of CS patients negatively affects their postoperative outcomes. [

27] Individuals with CS experience increased pain perception, often presenting with hyperalgesia and allodynia as characteristic symptoms. [

10] This heightened sensitivity can play a crucial role in difficulties with post-surgical pain and recovery, further contributing to suboptimal clinical results. [

27] Third, CS patients tend to have higher minimal clinically important difference (MCID) thresholds than non-CS patients. As a result, their overall postoperative outcomes tend to be worse, and the likelihood of achieving the MCID is significantly lower. [

12] For those reasons, patients with CS are more prone than those without CS to experience persistent pain and inferior outcomes following UKA.

This study has several strengths, including a well-defined patient cohort, a standardized surgical technique performed by a single surgeon, and the use of validated outcome measures such as the WOMAC and FJS. These factors minimize variability and enhance the reliability of our findings. However, there are also limitations to consider. First, most of the patients who underwent UKAs were female (108 of 131, 89%). Although this demographic trend is well-documented in the Korean population, the underlying reasons remain unclear. [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] Second, although the data were collected prospectively, this study was conducted as a retrospective review using a single-institution database. As a result, inherent limitations such as selection bias might have influenced the findings. Third, various tools exist for assessing patient satisfaction after surgery. [

35] In this study, we used the new KSS system, a validated tool designed to minimize the evaluation burden. [

21] Although the KSS is widely accepted, incorporating additional assessment methods could provide a more comprehensive evaluation of patient satisfaction. Fourth, the follow-up period was limited to two years, and patient satisfaction was assessed only at the two-year postoperative mark. Longer-term studies are needed to better understand how postoperative satisfaction and its relationship with CS evolve over time. Fifth, the study might be underpowered, increasing the risk of type II errors and potentially limiting the ability to detect all relevant associations. Larger prospective studies with a broader and more diverse patient population are needed to strengthen these findings. Sixth, we used the CSI as the primary tool for assessing CS. Although the CSI is a validated and widely used screening measure [

17,

18], it is based on self-reported data and might not fully capture the neurophysiological aspects of CS. Future studies incorporating QST or functional neuroimaging could provide a more comprehensive understanding of CS in patients undergoing UKA. [

36] Additionally, all surgeries were performed at a single institution by a single surgeon, which might limit the generalizability of the findings to other surgical settings. A multicenter study would help validate these results across different patient populations. Despite those limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between CS and both pain and dissatisfaction following UKA.

6. Conclusions

This study underscores the importance of recognizing CS as a critical determinant of postoperative pain and dissatisfaction following UKA. Patients with high CSI scores experience greater pain, increased joint awareness, and overall poorer outcomes despite technically successful surgeries. Patients with CS should be closely monitored postoperatively and provided with appropriate pain management strategies to optimize their surgical outcomes. Future research should focus on refining these strategies and exploring innovative approaches to pain modulation in this patient population.

Author Contributions

Dr In had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Kim, In.; Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Kim,Choi; Drafting of the manuscript: Kim, In; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Administrative, technical, or material support: Kim, Choi; Supervision: In.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00215891) and Research Fund of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital , The Catholic University of Korea. (ZC25CISI0102)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (KC22RISI0506).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data published in this research are available on request from the corresponding author (YI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Digennaro, V.; Ferri, R.; Panciera, A.; Bordini, B.; Cecchin, D.; Benvenuti, L.; Traina, F.; Faldini, C. Coronal plane alignment of the knee (CPAK) classification and its impact on medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: exposing a unexpected external shift of limb mechanical axis in case of prearthritic constitutional valgus alignment: a retrospective radiographic study. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 14. [CrossRef]

- Koshino, T.; Sato, K.; Umemoto, Y.; Akamatsu, Y.; Kumagai, K.; Saito, T. Clinical results of unicompartmental arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis using a tibial component with screw fixation. Int Orthop 2015, 39, 1085-1091. [CrossRef]

- Vasso, M.; Antoniadis, A.; Helmy, N. Update on unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Current indications and failure modes. EFORT Open Rev 2018, 3, 442-448. [CrossRef]

- Vasso, M.; Del Regno, C.; Perisano, C.; D’Amelio, A.; Corona, K.; Schiavone Panni, A. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is effective: ten year results. Int Orthop 2015, 39, 2341-2346. [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.N.; Petheram, T.; Avery, P.J.; Gregg, P.J.; Deehan, D.J. Revision for unexplained pain following unicompartmental and total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012, 94, e126. [CrossRef]

- Calkins, T.E.; Hannon, C.P.; Fillingham, Y.A.; Culvern, C.C.; Berger, R.A.; Della Valle, C.J. Fixed-Bearing Medial Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty in Patients Younger Than 55 Years of Age at 4-19 Years of Follow-Up: A Concise Follow-Up of a Previous Report. J Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 917-921. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.M.; Burnett, R.A.; Serino, J.; Gerlinger, T.L. Painful Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: Etiology, Diagnosis and Management. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2024, 12, 546-557. [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J.; Hassett, A.L. The role of centralised pain in osteoarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017, 35 Suppl 107, 79-84.

- Nijs, J.; Leysen, L.; Vanlauwe, J.; Logghe, T.; Ickmans, K.; Polli, A.; Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; Huysmans, E. Treatment of central sensitization in patients with chronic pain: time for change? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2019, 20, 1961-1970. [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2-s15. [CrossRef]

- Dave, A.J.; Selzer, F.; Losina, E.; Usiskin, I.; Collins, J.E.; Lee, Y.C.; Band, P.; Dalury, D.F.; Iorio, R.; Kindsfater, K.; et al. The association of pre-operative body pain diagram scores with pain outcomes following total knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017, 25, 667-675. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Seo, J.Y.; In, Y. Minimal Clinically Important Differences for Patient-Reported Outcomes After TKA Depend on Central Sensitization. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021, 103, 1374-1382. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Yoon, K.B.; Yoon, D.M.; Yoo, J.H.; Ahn, K.R. Influence of Centrally Mediated Symptoms on Postoperative Pain in Osteoarthritis Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Observational Evaluation. Pain Pract 2015, 15, E46-53. [CrossRef]

- Koh, I.J.; Kang, B.M.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, K.Y.; Sohn, S.; In, Y. How Does Preoperative Central Sensitization Affect Quality of Life Following Total Knee Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty 2020, 35, 2044-2049. [CrossRef]

- Lape, E.C.; Selzer, F.; Collins, J.E.; Losina, E.; Katz, J.N. Stability of Measures of Pain Catastrophizing and Widespread Pain Following Total Knee Replacement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020, 72, 1096-1103. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, E.; Kasai, T.; Araki, R.; Sasaki, T.; Wakai, Y.; Akaishi, K.; Chiba, D.; Kimura, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tsuda, E.; et al. Central Sensitization and Postoperative Improvement of Quality of Life in Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Prospective Observational Study. Prog Rehabil Med 2022, 7, 20220009. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T.G.; Neblett, R.; Cohen, H.; Howard, K.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Williams, M.J.; Perez, Y.; Gatchel, R.J. The development and psychometric validation of the central sensitization inventory. Pain Pract 2012, 12, 276-285. [CrossRef]

- Neblett, R.; Cohen, H.; Choi, Y.; Hartzell, M.M.; Williams, M.; Mayer, T.G.; Gatchel, R.J. The Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI): establishing clinically significant values for identifying central sensitivity syndromes in an outpatient chronic pain sample. J Pain 2013, 14, 438-445. [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, N.; Buchanan, W.W.; Goldsmith, C.H.; Campbell, J.; Stitt, L.W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988, 15, 1833-1840.

- Behrend, H.; Giesinger, K.; Giesinger, J.M.; Kuster, M.S. The "forgotten joint" as the ultimate goal in joint arthroplasty: validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure. J Arthroplasty 2012, 27, 430-436.e431. [CrossRef]

- Noble, P.C.; Scuderi, G.R.; Brekke, A.C.; Sikorskii, A.; Benjamin, J.B.; Lonner, J.H.; Chadha, P.; Daylamani, D.A.; Scott, W.N.; Bourne, R.B. Development of a new Knee Society scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012, 470, 20-32. [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, H.; Kreicbergs, A.; Jansson, K.A. Prediction of persistent pain after total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008, 90, 166-171. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V.; Fletcher, D.; Bouhassira, D.; Sessler, D.I.; Chauvin, M. The evolution of primary hyperalgesia in orthopedic surgery: quantitative sensory testing and clinical evaluation before and after total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2007, 105, 815-821. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Ju, G.I.; In, Y. Centrally sensitized patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty have higher expectations than do non-centrally sensitized patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022, 30, 1257-1265. [CrossRef]

- Flood, A.B.; Lorence, D.P.; Ding, J.; McPherson, K.; Black, N.A. The role of expectations in patients’ reports of post-operative outcomes and improvement following therapy. Med Care 1993, 31, 1043-1056. [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C.A.; Reid, M.C.; Duculan, R.; Girardi, F.P. Improvement in Pain After Lumbar Spine Surgery: The Role of Preoperative Expectations of Pain Relief. Clin J Pain 2017, 33, 93-98. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Sung, Y.G.; Park, D.C.; Yoon, E.J.; In, Y. Influence of increased pain sensitivity on patient-reported outcomes following total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022, 30, 782-790. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Choi, C.H. Evaluation of Appropriateness of the Reimbursement Criteria of Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service for Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg 2023, 15, 241-248. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.I.; Kim, J.H.; Min, K. Does the clinical and radiologic outcomes following total knee arthroplasty using a new design cobalt-chrome tibial plate or predecessor different? Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 34. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Ro, D.H.; Lee, M.C.; Han, H.S. Can individual functional improvements be predicted in osteoarthritic patients after total knee arthroplasty? Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 31. [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Kim, K.H.; Ko, S.; Jo, C.; Han, H.S.; Lee, M.C.; Ro, D.H. Total Knee Arthroplasty: Is It Safe? A Single-Center Study of 4,124 Patients in South Korea. Clin Orthop Surg 2023, 15, 935-941. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; Kim, G.W.; Lee, C.Y.; Song, E.K.; Seon, J.K. No Difference in Clinical Outcomes and Survivorship for Robotic, Navigational, and Conventional Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty with a Minimum Follow-up of 10 Years. Clin Orthop Surg 2023, 15, 82-91. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Hiranaka, T.; Okamoto, K.; Fujishiro, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kensuke, A.; Kitazawa, D.; Kotoura, K. Is simultaneous bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty better than simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty? Knee Surg Relat Res 2023, 35, 12. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chang, M.J.; Kim, T.W.; D’Lima, D.D.; Kim, H.; Han, H.S. Serial changes in patient-reported outcome measures and satisfaction rate during long-term follow-up after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Relat Res 2024, 36, 43. [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.E.; Feller, J.A. Comparison of the short form-12 (SF-12) health status questionnaire with the SF-36 in patients with knee osteoarthritis who have replacement surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016, 24, 2620-2626. [CrossRef]

- Wylde, V.; Palmer, S.; Learmonth, I.D.; Dieppe, P. The association between pre-operative pain sensitisation and chronic pain after knee replacement: an exploratory study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013, 21, 1253-1256. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).