1. Introduction

Insect pests may pose a significant threat to agricultural production. The case of the new invasive pest in Africa, the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is not an exception. First reported in Africa in 2016 (Goergen et al., 2016), the fall armyworm (FAW) is a polyphagous migratory insect (Meagher et al., 2004) considered a major pest of maize (Molina-Ochoa et al., 2001) and poses a serious threat to food security of millions of people in Sub-Saharan Africa (Prasanna et al., 2018). In Mozambique, the occurrence of FAW was confirmed in early 2017 when a pheromone-based trap survey was conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security in several districts of the country (MASA, 2017). A report released in September 2018 by FAO of the United Nations office in Mozambique (FAO, 2018) estimates a loss of around 49 thousand tons of maize as a direct consequence of FAW attack since its detection in the country. Due to its economic importance, FAW was officially put on a top priority list of national agricultural pests, prompting the government, research institutions and universities to look for practical solutions in order to reduce yield loss provoked by its attack on maize. In this regard and based on Integrated Pest Management (IPM) assumptions, we decided to investigate how crop diversification affects the dynamics of FAW and to what extent it causes damages on maize in such situations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Locations

We carried out a field survey in 215 farms distributed in 6 different locations of the district of Quelimane, Mozambique, between August 27th and September 03rd, 2018. GPS coordinates and number of farms sampled in each location were recorded as shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Sampling Procedures

Only farms with maize were included in the survey. Twenty plants were randomly selected and checked for symptoms of attack by FAW and presence of larvae. Damages were assessed based on a visual scale ranging from 1 to 5 points as described: 1 = up to 10% of the leaf surface damaged; 2 = between 10 to 25% of the leaf surface damaged; 3 = between 25 to 50% of leaf surface damaged; 4 = between 50 to 75% of leaf surface damaged; 5 = leaf surface area damaged in more than 75%. Crop development stage, number and name of crops intercropped with maize were recorded.

2.3. Data Management

We determined the number and relative frequency of farms in which maize was planted as a sole crop or intercropped. We determined the relative frequency of farms with different number of crops. We then listed the crops found in each farm and determined the number of farms in which a given crop was observed before determining its relative frequency. We determined the relative frequency of farms according to different development stages of maize and we then asked whether different development stages of maize were equally attacked by FAW. Because sampling was carried out in different locations, we asked if regardless of the location of sampling, damages and number of larvae on maize would be similar. Finally we established a relationship between number of crops in the farm and percentage of damaged plants, number of larvae per farm and damage score.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed through R version 3.5.1 (Feather Spray). One-Way Analysis of Variance of data related to percentage of damaged plants and number of larvae per farm per location, per development stage and per number of crops in the farm was carried out. Tukey HSD multiple comparison of means at 95% family-wise confidence level was used. Differences on damages score were determined based on scale of points attributed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cropping Systems and Maize Development Stage

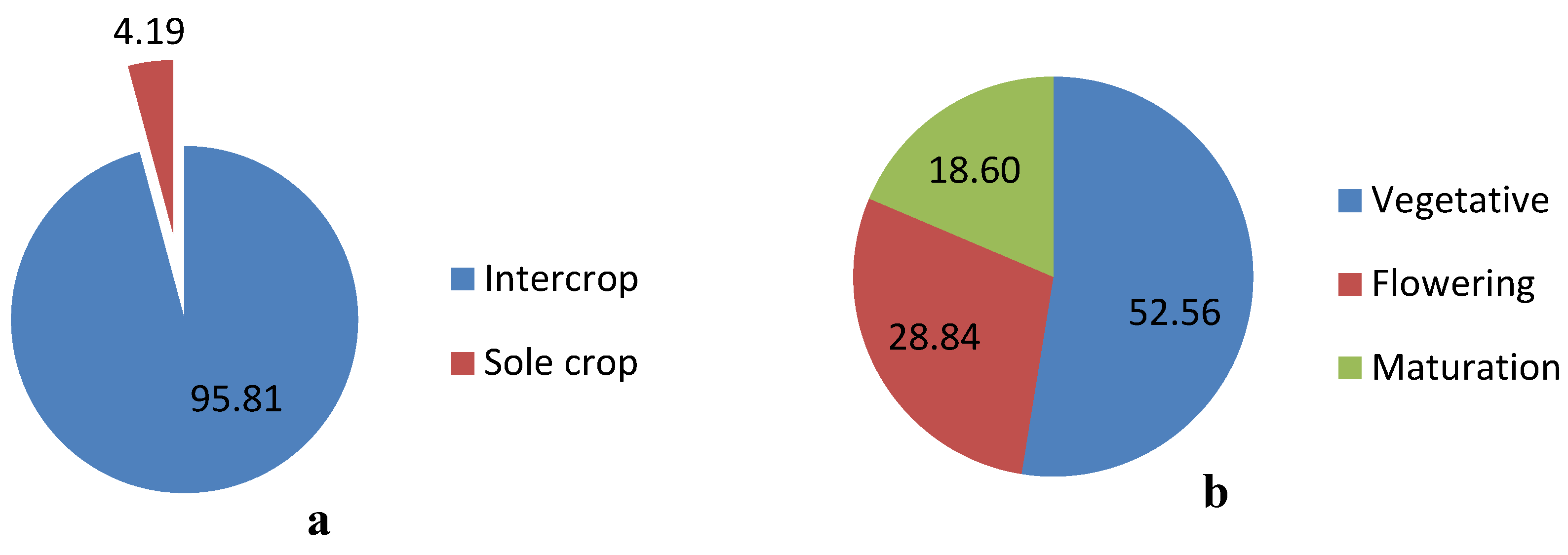

As shown in

Figure 1a, almost every farm (about 96%) was under intercrop. In relation to the development stage, we found that more than half of the farms had maize in its vegetative stage (52.56%) as presented in

Figure 1b.

3.2. Damages and Number of Larvae per Development Stage

Our study shows that while vegetative stage had significantly higher percentage of damaged plants [(Pr>F) < 0.001], no differences were observed between flowering and maturation stages. While no differences were observed between vegetative and flowering stages in relation to the number of larvae, maturation stage had significantly lower number of larvae [(Pr>F) = 0.00411]. Although differences were observed in percentage of damaged plants and number of larvae among different stages, no differences were observed in damage score, as shown in

Table 2.

The fact that the number of larvae was lower in plants on maturation stage than in vegetative and flowering stages may be explained by the fact that in older plants, there are no new and fresh leaves which can be used as food by FAW in comparison to the previous stages. In contrary, vegetative stage shows lower percentage of damaged plants than flowering and maturation stages, as older plants were exposed to FAW attack for a longer period than the young ones.

3.3. Damages and Number of Larvae per Sampling Location

Significant differences were observed in percentage of damaged plants per location [(Pr>F) < 0.001] but there were no differences in the number of larvae per farm among different locations [(Pr>F) = 0.198]. No differences were observed on damage score (score 2) as shown in

Table 3.

3.4. Crops Intercropped with Maize

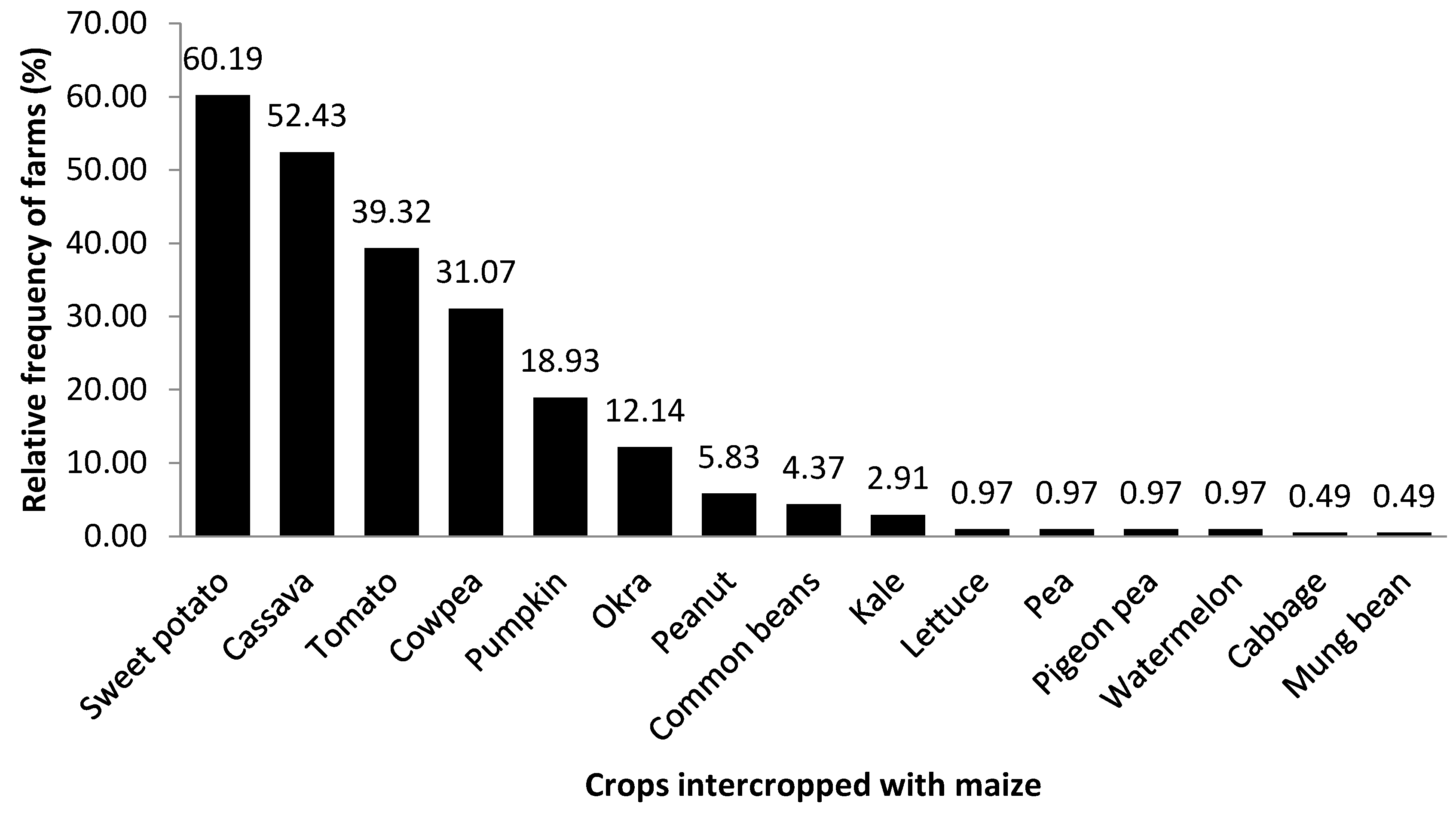

We found 15 different crops being intercropped with maize. We listed such crops in order of their importance in

Figure 2.

We found that sweet potato, cassava, tomato, cowpea, pumpkin and okra, are the most common crops in the period of the year in which our study was carried out. Although there are reports suggesting that FAW can feed on a wide number of different crops including some listed above (Day et al., 2017) we did not find any evidence of such behavior neither it was reported by the farmers, which may be an indication of FAW preference to maize as reported by Prasanna et al.(2018). Furthermore, these crops intercropped with maize seem to be of great importance for food security in Quelimane. Therefore, recommendations for the management of FAW based on its host range should take this knowledge into consideration.

3.2. Number of Crops in the Farm

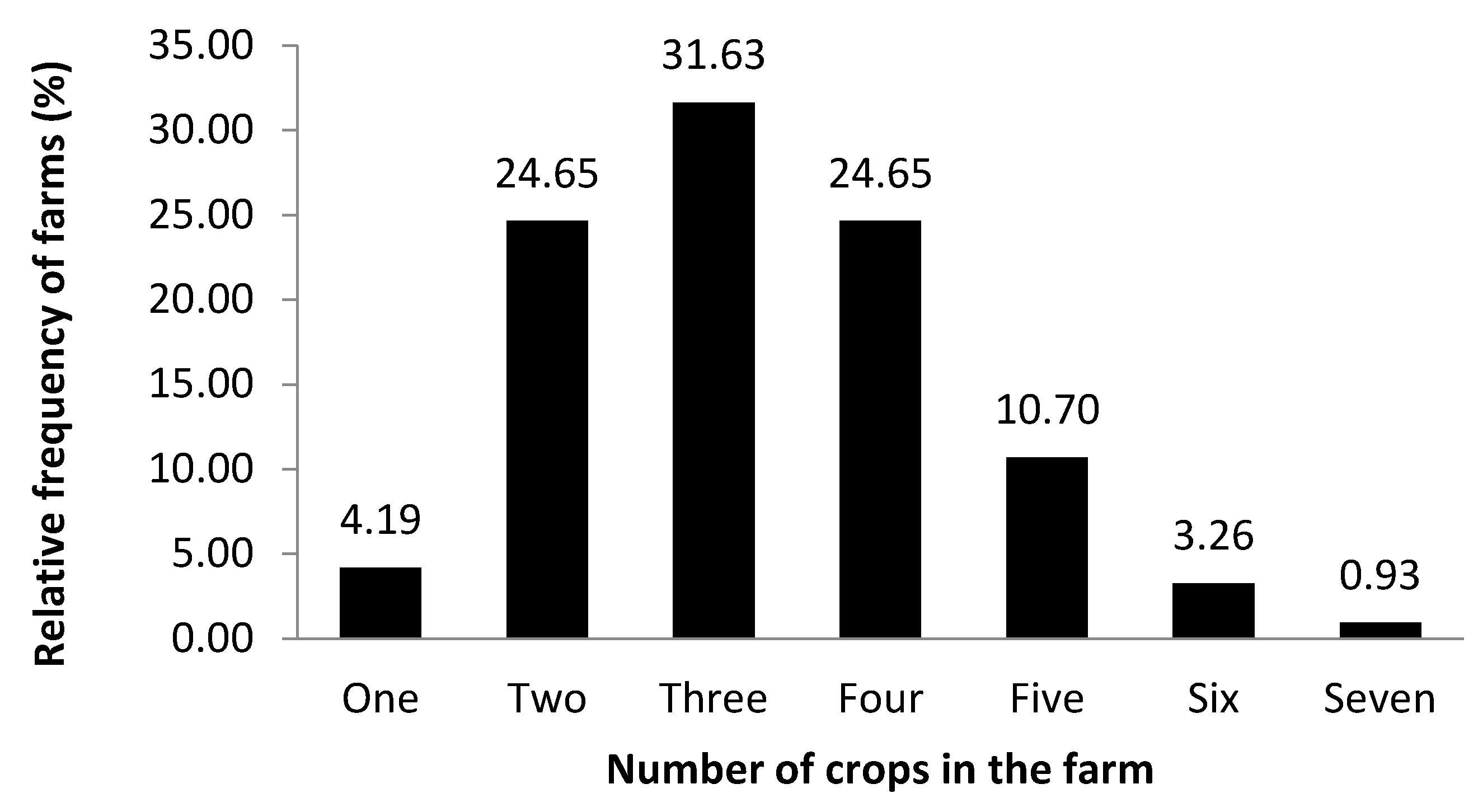

Based on the number of farms under intercrop, we found that most of the farms had between 2 to 5 different crops, with a record number of 7 crops as shown in

Figure 3.

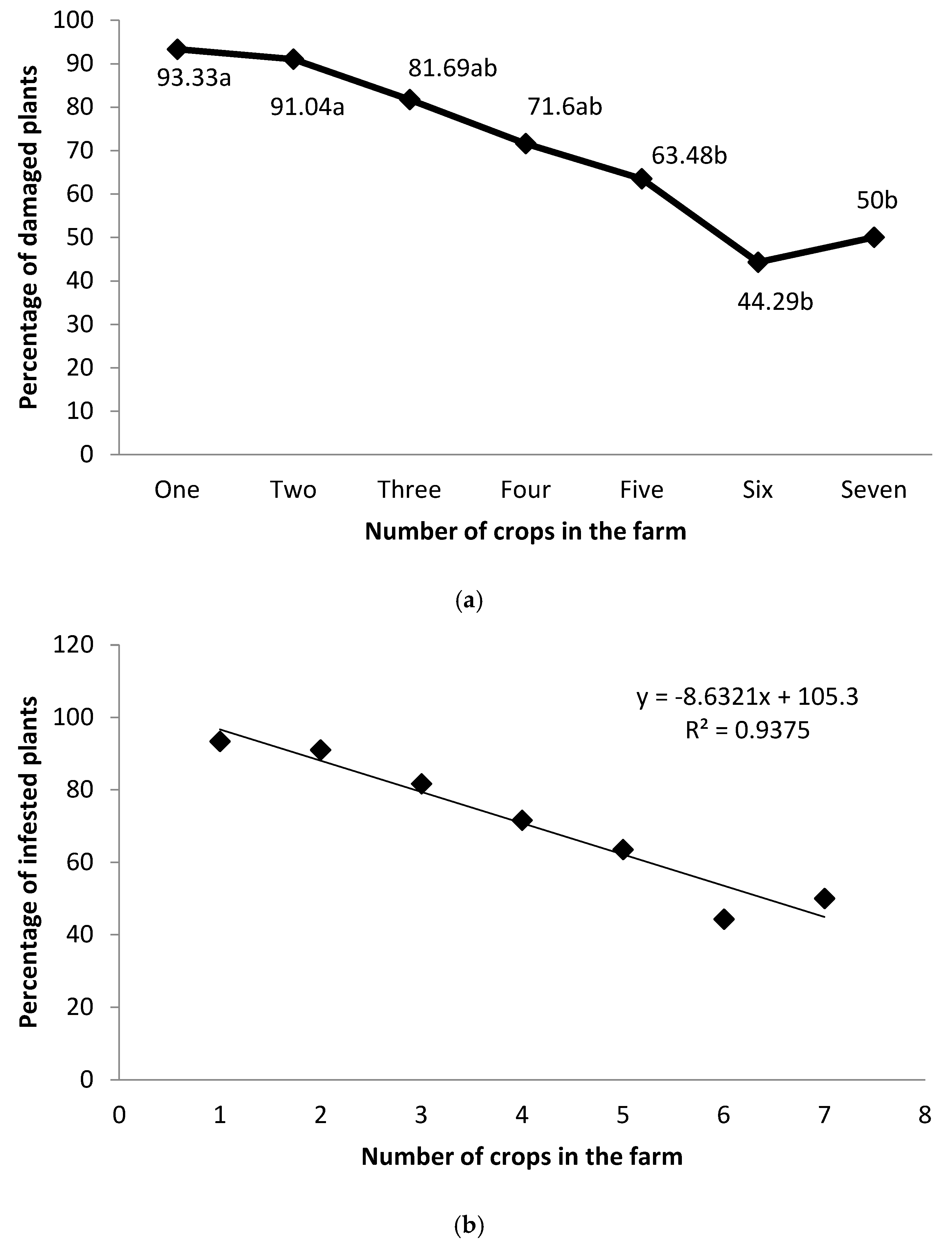

Differences were observed on the percentage of damaged plants per number of crops in the farm [(Pr>F) = 0.00229] as shown in

Figure 4a. Based on regression model provided in

Figure 4b, there is a strong association between the number of crops in the farm and percentage of damaged plants (R

2 = 0.9375). This means that the percentage of damaged plants may be highly influenced by the number of crops present in the farm in an inverse relation as

b is negative.

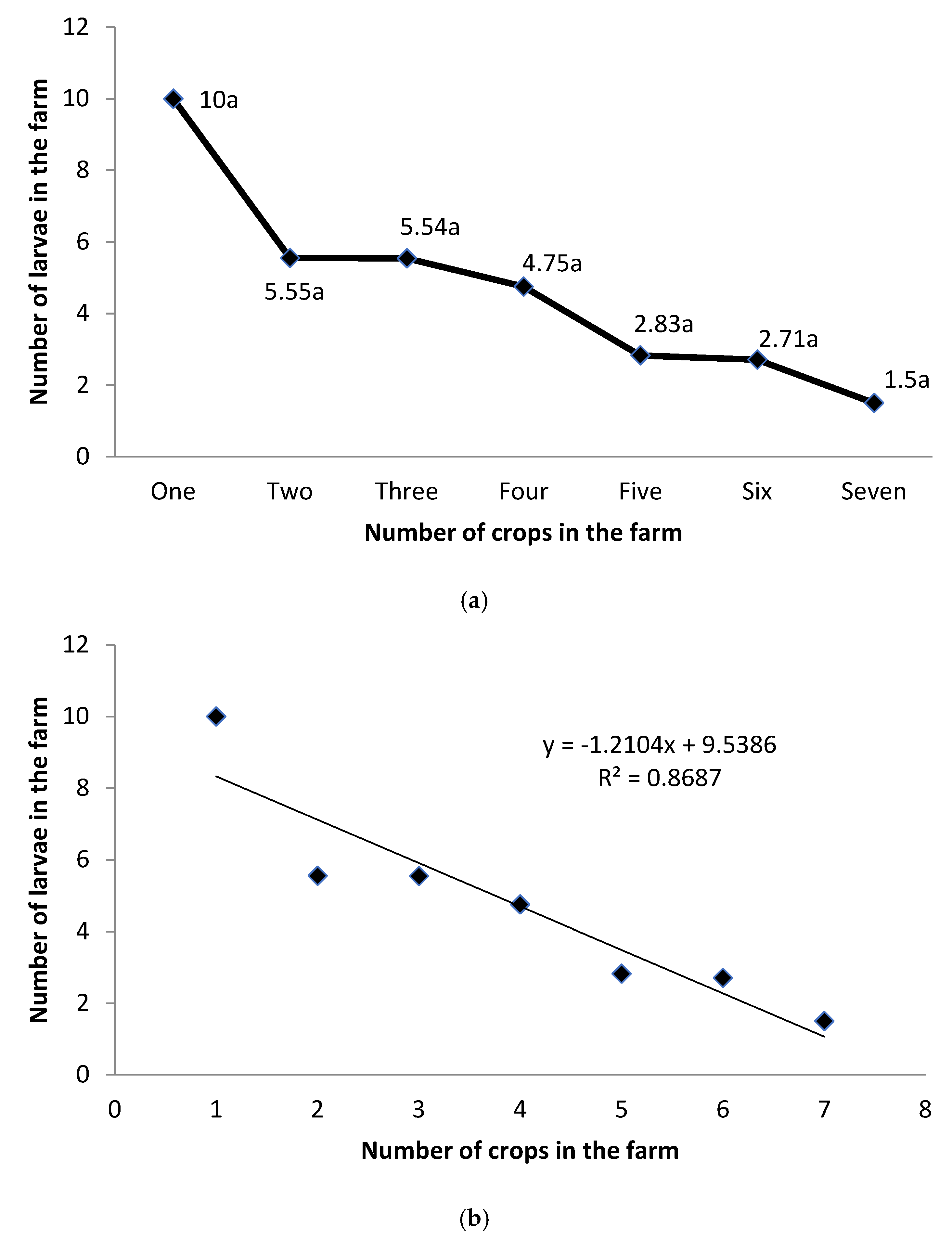

Although no differences were observed in the number of larvae regardless of the number of crops in the farm [Pr(>F) = 0.564] (

Figure 5a), regression analysis (

Figure 5b) shows a strong association between the number of crops and number of larvae in the farm (R

2 = 0.8687) in an inverse relationship as

b is negative.

Our findings on the number of FAW as a function of number of crops in the farm seems to be an indication that maize herbivore-induced plant volatiles are more effective attracting FAW when it is planted as a sole crop than when under intercrop, as the possible interaction of volatiles from different plants can misguide insects for host detection and reduce infestation as suggested by Afrin et al. (2017). Additionally, from the point of view of the insect pest, monocrop is a dense and pure concentration of its basic food resource. A more complex community exhibits more stability and less fluctuations in the numbers of undesirable organisms (Altieri et al., 2009).

In regard to herbivore-induced plant volatiles, Carroll et al. (2006) concluded that the monoterpene linanol and 4,8-dimethyl-1,3,7- nonatriene were the major volatiles induced by FAW herbivory on maize. They observed that FAW preferred damaged plants over undamaged ones. This may also be an indication of strong preference to maize (Meagher et al., 2004).

Although one can use intercrop as stand-alone approach to pest management (Smith and Liburd, 2018), the success of the method depends on a solid knowledge of how distinct crop characteristics and combinations will influence the behavior of pest (Seni, 2018) and arthropod-plant interactions (Smith and Mcsorley, 2000) as one of the benefits of intercropping is to act as pest and disease suppression strategy (Rämert et al., 2002).

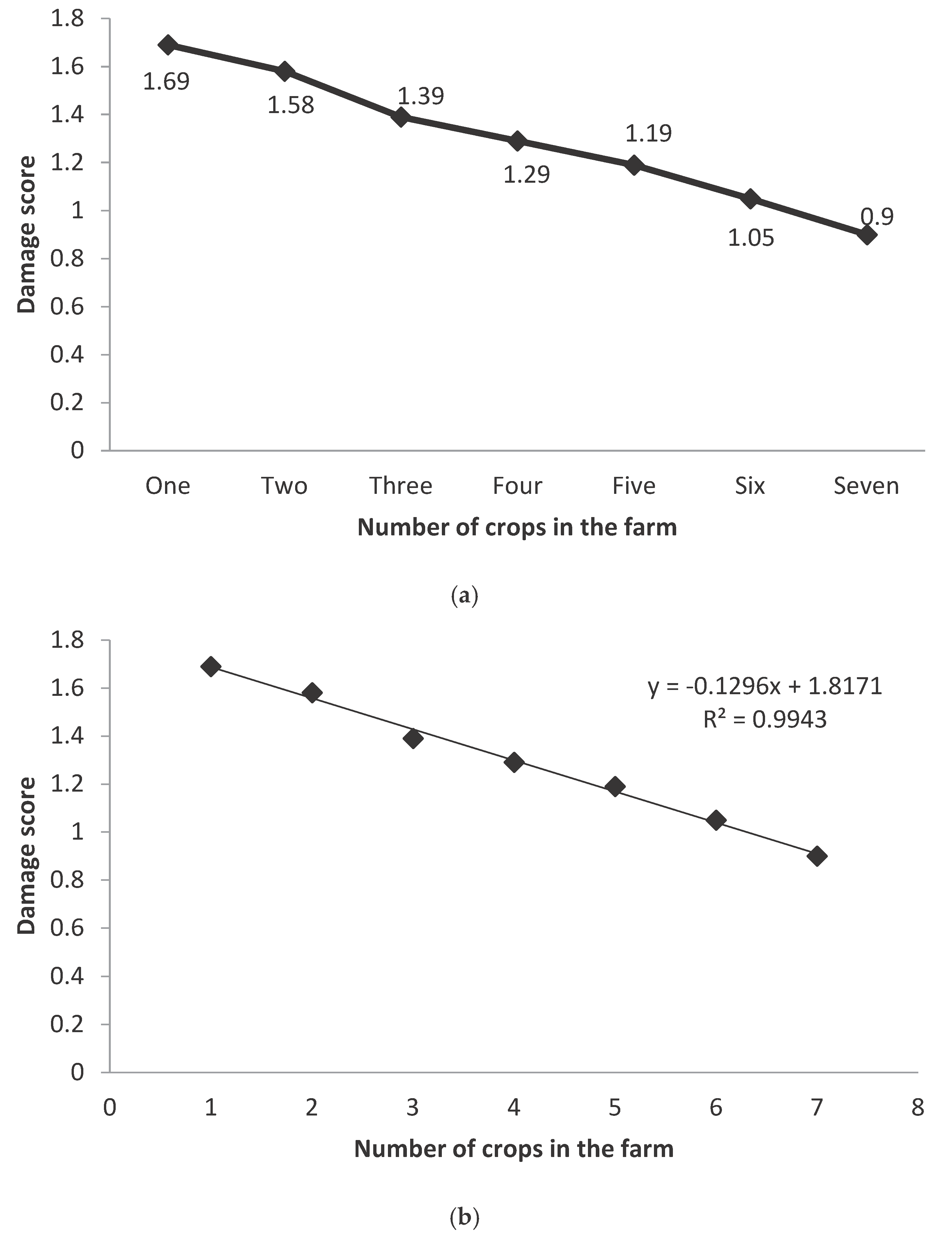

Our study also shows no differences on damage scores up to 6 crops (score 2) but farms with more than 6 different crops had lower damage score (score 1) as shown in

Figure 6a. Regression analysis indicates a highly inverse relationship between recorded damage scores and number of crops in the farm (R

2 = 0.9943) and

b is negative (

Figure 6b).

4. Conclusions

It seems that FAW is well established in Quelimane and farmers are not familiar with the pest as they are not able to identify it. The number of damaged plants increases with the age while the contrary is observed in relation to the number of larvae. Independently of the sampling location, development stage and number of crops in the farm, plants were found to have between 10 and 25% of its leaf surface area damaged by FAW. Although farmers normally do not do intercrop on the basis of pest management approach, the fact that almost every farm was under intercrop, may significantly contribute to the reduction of the pest population density in the farms and this alternative should be better explored. Based in our findings, we concluded that there is an inverse relationship between number of crops in the farms and percentage of damaged plants, number of larvae and damage score. Control measures should be stepped up during vegetative and flowering stages and farmers should avoid planting maize as a sole crop.

Further Research and Challenges

We found that farmers are not familiar with FAW and, as such, they do not apply any method of control against it. Farmers should therefore be trained in identification of different stages of FAW and symptoms of its attack. Because of ecological features of FAW and taking into account health and environmental issues related to pesticide application, if pesticides are to be used, class III and selective pesticides should be recommended, made available and farmers should be properly trained in pesticide management and application through existing agricultural extension services.

We also found dead larvae of FAW in some plants and we observed that there were many ants in those plants. We then decided to check plants with ants and observed that all plants with ants had dead larvae or no larvae at all. We are not sure if larvae died because of the ants or ants were there because of dead larvae. Based on this observation, it would be of scientific interest to check whether ants are killing FAW larvae or there are entomopathogens such as fungi or viruses acting as biocontrol agents. Taking this into account, surveys for the identification of potential natural enemies should be carried out. As an important component of IPM approach, it would also be interesting to conduct field experiments for the screening of genetic resistance of maize varieties grown in Mozambique.

Author Contributions

Albasini Caniço conceived and designed the study; Albasini Caniço, João Tibério and Mhanuel Arijama carried out the study; Albasini Caniço analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through a PhD scholarship for the first author (SFRH/BD/135260/2017) under Programa de Pós-Graduação Ciência para o Desenvolvimento (PGCD), based at Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência in Portugal.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Enga. Vanda Massina from Universidade Pedagógica de Quelimane, Mozambique, for her logistic assistance during the survey, which included transportation and facility to keep field materials. Our gratitude also goes to the farmers of the district of Quelimane for facilitating our field activities.

References

- Afrin, S., Latif, A., Banu, N.M.A., Kabir, M.M.M., Haque, S.S., Emam Ahmed, M.M., Tonu, N.N., Ali, M.P., 2017. Intercropping empower reduces insect pests and increases biodiversity in agro-ecosystem. Agric. Sci. 8, 1120–1134. [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Ponti, L., 2009. Crop diversification strategies for pest regulation in IPM systems, in: Radcliffe, E.B., Hutchinson, W.D., Cancelado, R.E. (Eds.), Integrated Pest Management: Concepts, Tactics, Strategies and Case Studies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 116–130. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.J., Schmelz, E.A., Meagher, R.L., Teal, P.E.A., 2006. Attraction of Spodoptera frugiperda larvae to volatiles from herbivore-damaged maize seedlings. J. Chem Ecol 32, 1911–1924. [CrossRef]

- Day, R., Abrahams, P., Bateman, M., Beale, T., Clottey, V., Cock, M., Colmenarez, Y., Corniani, N., Early, R., Godwin, J., Gomez, J., Moreno, P.G., Murphy, S.T., Oppong-Mensah, B., Phiri, N., Pratt, C., Silvestri, S., Witt, Arne, 2017. Fall armyworm: Impacts and implications for Africa. Outlooks Pest Manag. 28, 196–201. [CrossRef]

- FAO, 2018. Lagarta do Funil do Milho : FAO adverte para medidas sustentáveis para conter a praga [WWW Document]. URL http://www.fao.org/mozambique/news/detail/pt/c/1151631/.

- Goergen, G., Kumar, P.L., Sankung, S.B., Togola, A., Tamò, M., 2016. First report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm spodoptera frugiperda (J E Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in West and Central Africa. PLoS One 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- MASA, 2017. Situação actual da lagarta do funil de milho, spodoptera frugiperda, em Moçambique. Maputo.

- Meagher, A.R.L., Nagoshi, R.N., Stuhl, C., Mitchell, E.R., 2004. Larval development of fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different cover crop plants. Florida Entomol. 87, 454–460.

- Molina-Ochoa, J., Hamm, J.J., Lezama-Gutiérrez, R., López-Edwards, M., González-Ramírez, M., Pescador-Rubio, A., 2001. A Survey of fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) parasitoids in the mexican states of Michoacán, Colima, Jalisco, and Tamaulipas, The Florida Entomologist. [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, B.M., Huesing, J.E., Eddy, R., Peschke, V.M. (Eds.), 2018. Fall armyworm in Africa: a guide for integrated pest management, First Edit. ed. USAID and CIMMYT, Mexico.

- Rämert, B., Lennartsson, M., Davies, G., 2002. The use of mixed species cropping to manage pests and diseases – theory and practice, in: UK Organic Research 2002: Proceedings of the COR Conference. Aberystwyth, pp. 207–210.

- Seni, A. 2018. Role of intercropping practices in farming system for insect pest management. Acta Sci. Agric. 2, 8–11.

- Smith, H.A., Liburd, O.E., 2018. Intercropping, Crop Diversity and Pest Management. University of Florida-IFAS Extension.

- Smith, H.A., Mcsorley, R., 2000. Intercropping and pest panagement: A review of major concepts. Am. Entomol. 46, 154–161.

- R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).