Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

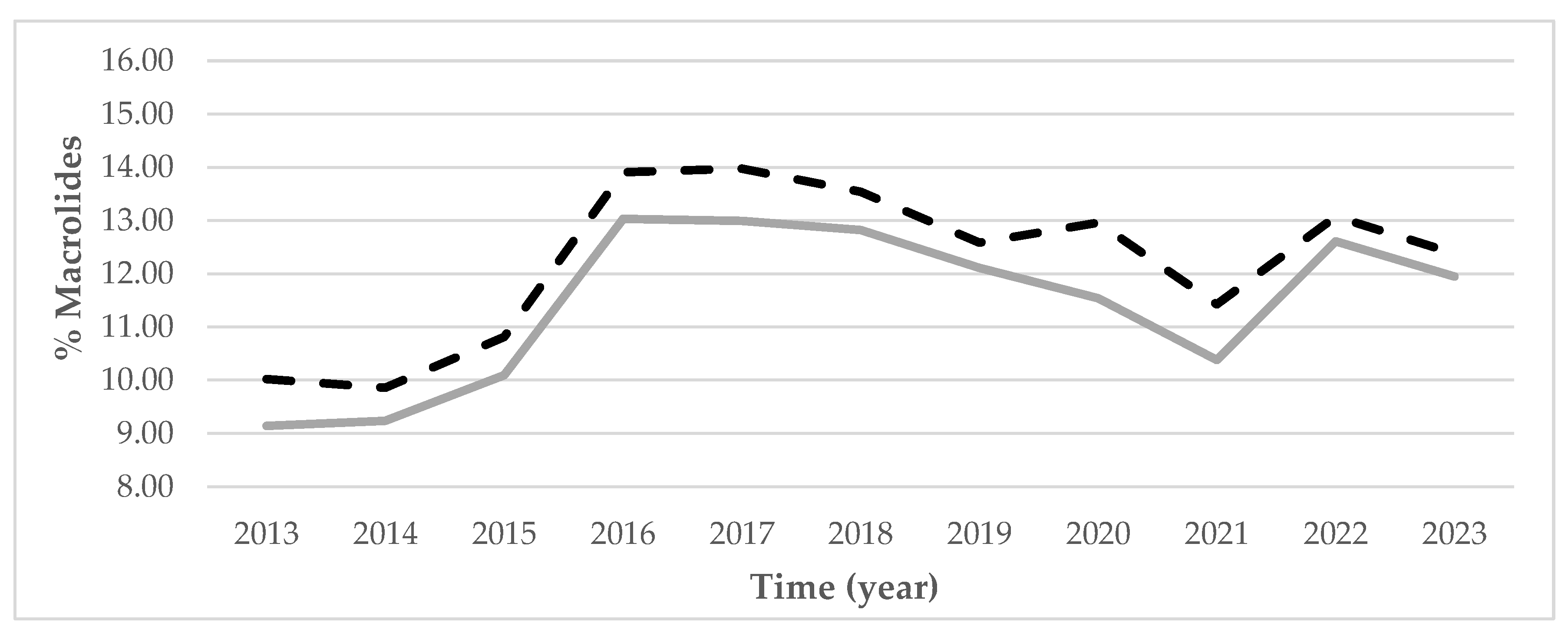

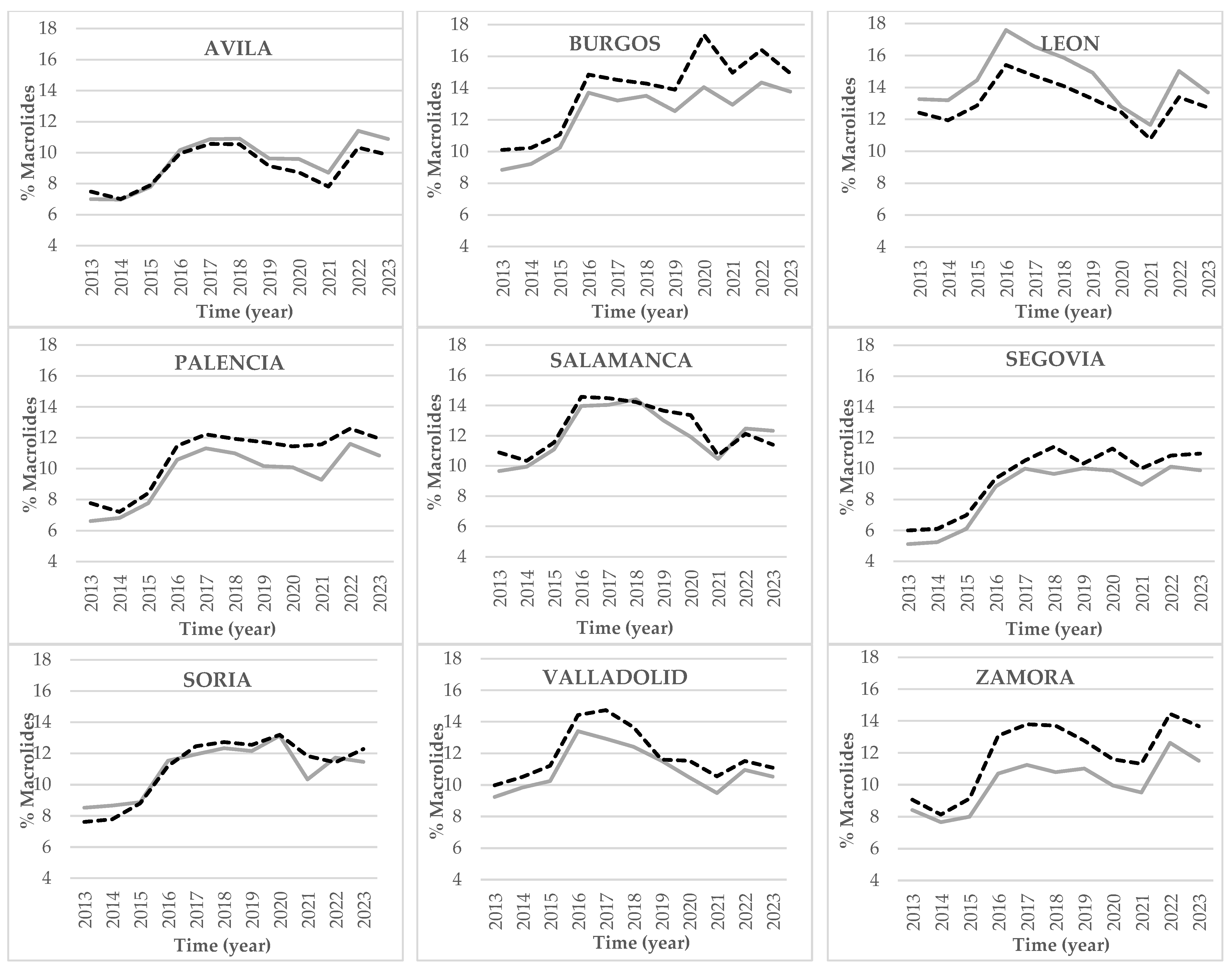

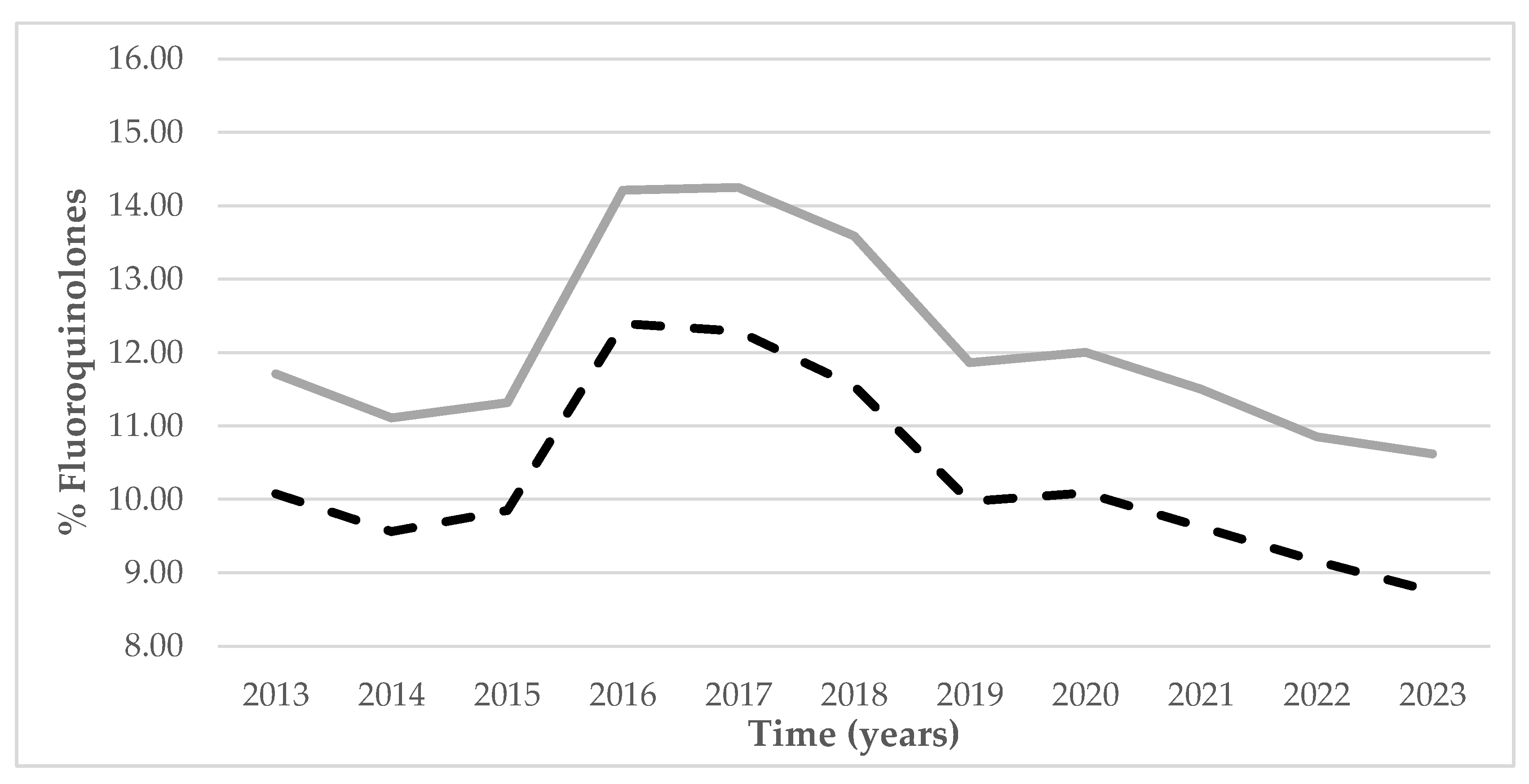

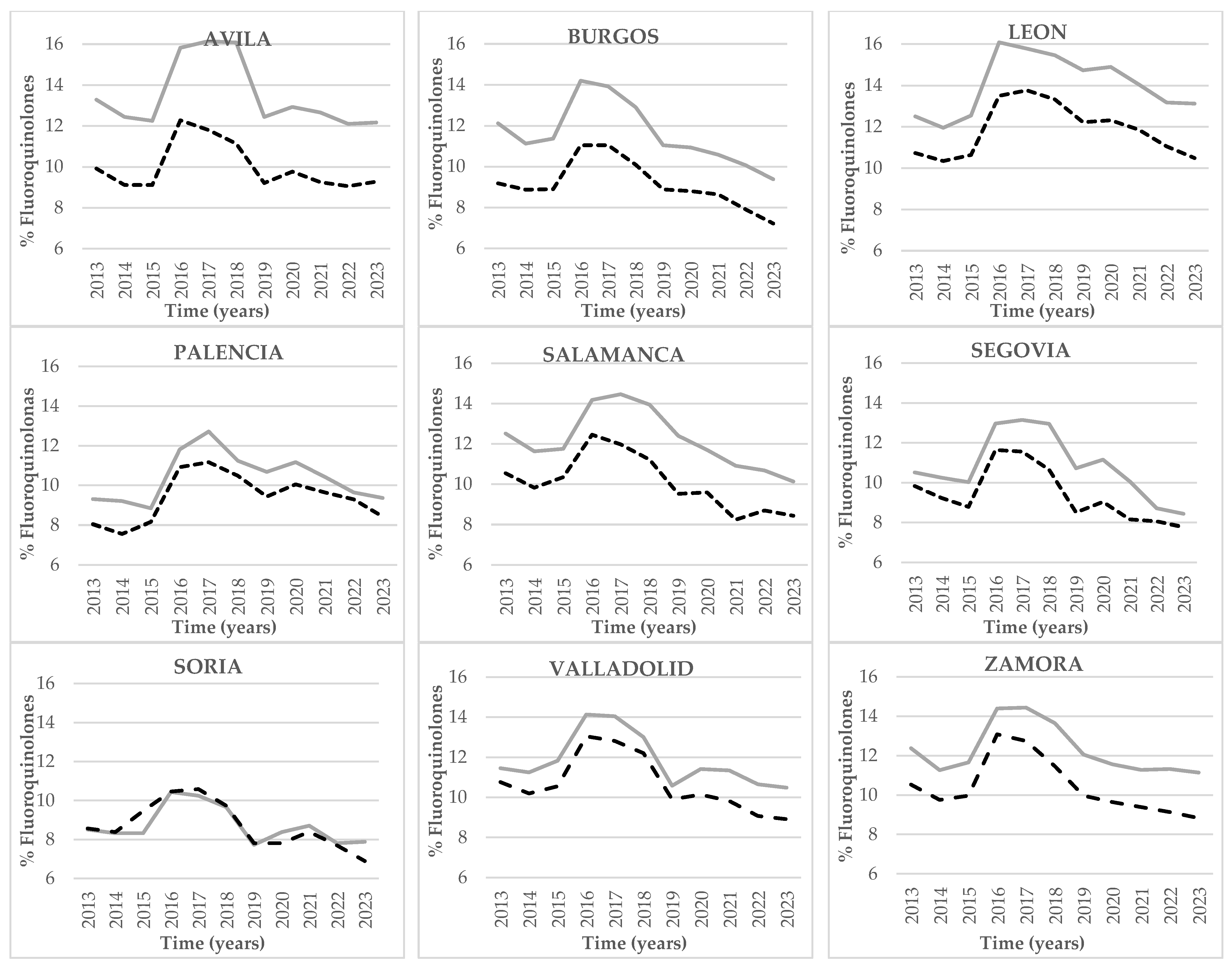

Background/Objectives: According to the World Health Organization, bacterial resistance is one of the main threats to public health and could within a short time become the principal cause of death. This study proposes to study antibiotic prescription rates at Basic Health Centres (BHC) within Castile and Leon over the period 2013-2023, and to determine which sociodemographic variables might influence the prescription of antibiotics. Methods: A descriptive, observational, ecological study was conducted on the basis of data provided by Concylia (Pharmaceutical information system-Castile & Leon Health Service). Comparable variables (time of prescription and type of Health Centre) and variables of results (Defined Daily Dose per 1000 health-center card-holders per day and qualitative antibiotic selection variables) were analyzed. Results: During the first years under analysis, prescriptions increased, followed by a reduction at the start of 2015 that continued up until 2021, after which a new increase was recorded and they once again reached values in 2023 that were comparable to those observed in 2019. Throughout all of Castile and Leon, there were more prescriptions within urban areas; but when analyzed by provinces, prescriptions were mainly higher in rural areas within most provinces. The percentage of macrolides was higher in urban areas, whereas the percentage of fluoroquinolones was higher in rural areas. Conclusions: The variation was repeated throughout the period under study in a similar way in all the provinces of Castile and Leon and at a national level. Differences were observed in prescriptions between the provinces of the autonomous region. Higher prescriptions rates were observed in the rural areas of most provinces.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

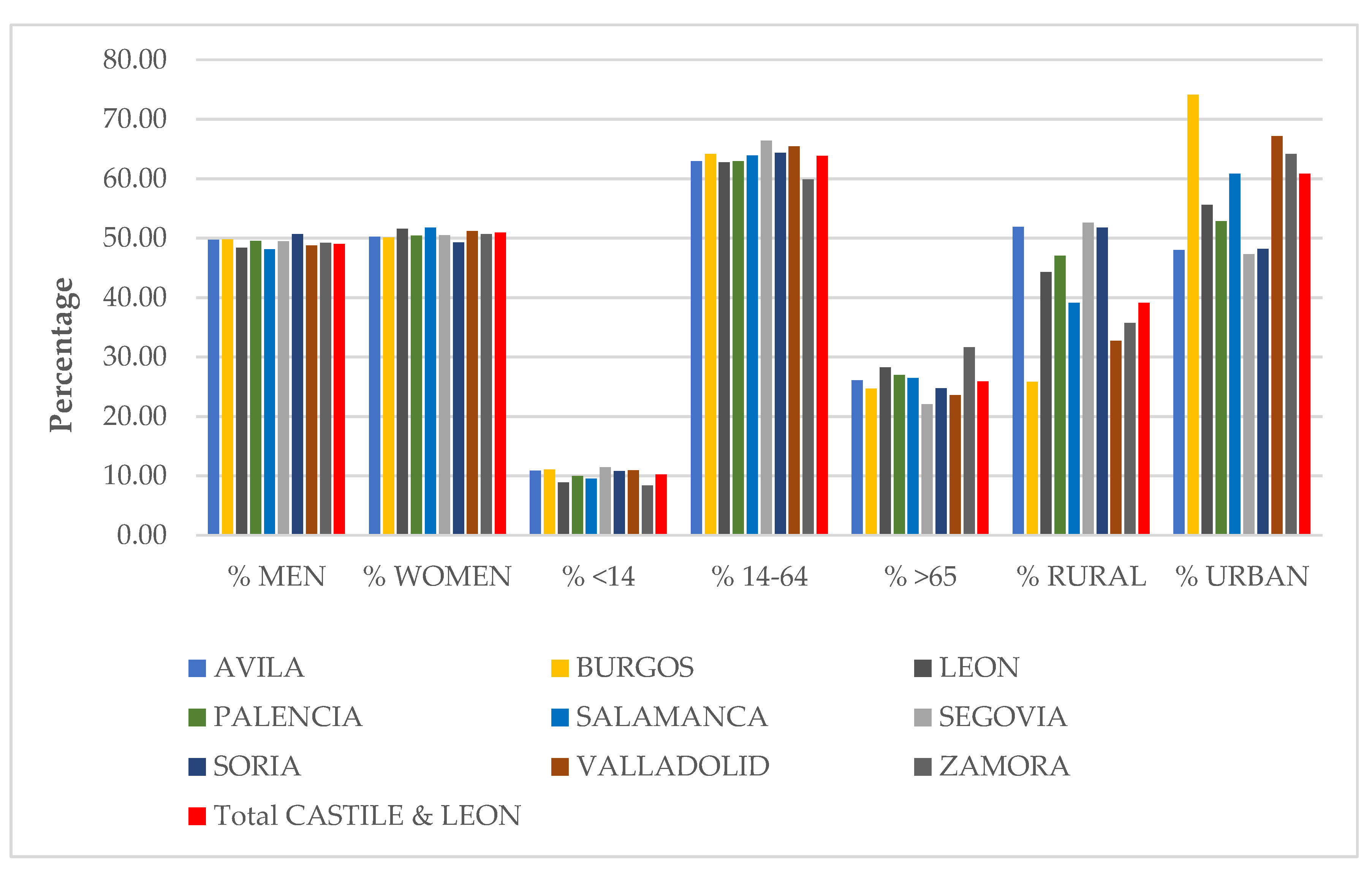

2.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Population Holding a Health-Care Card in Castile and Leon (Figure 1)

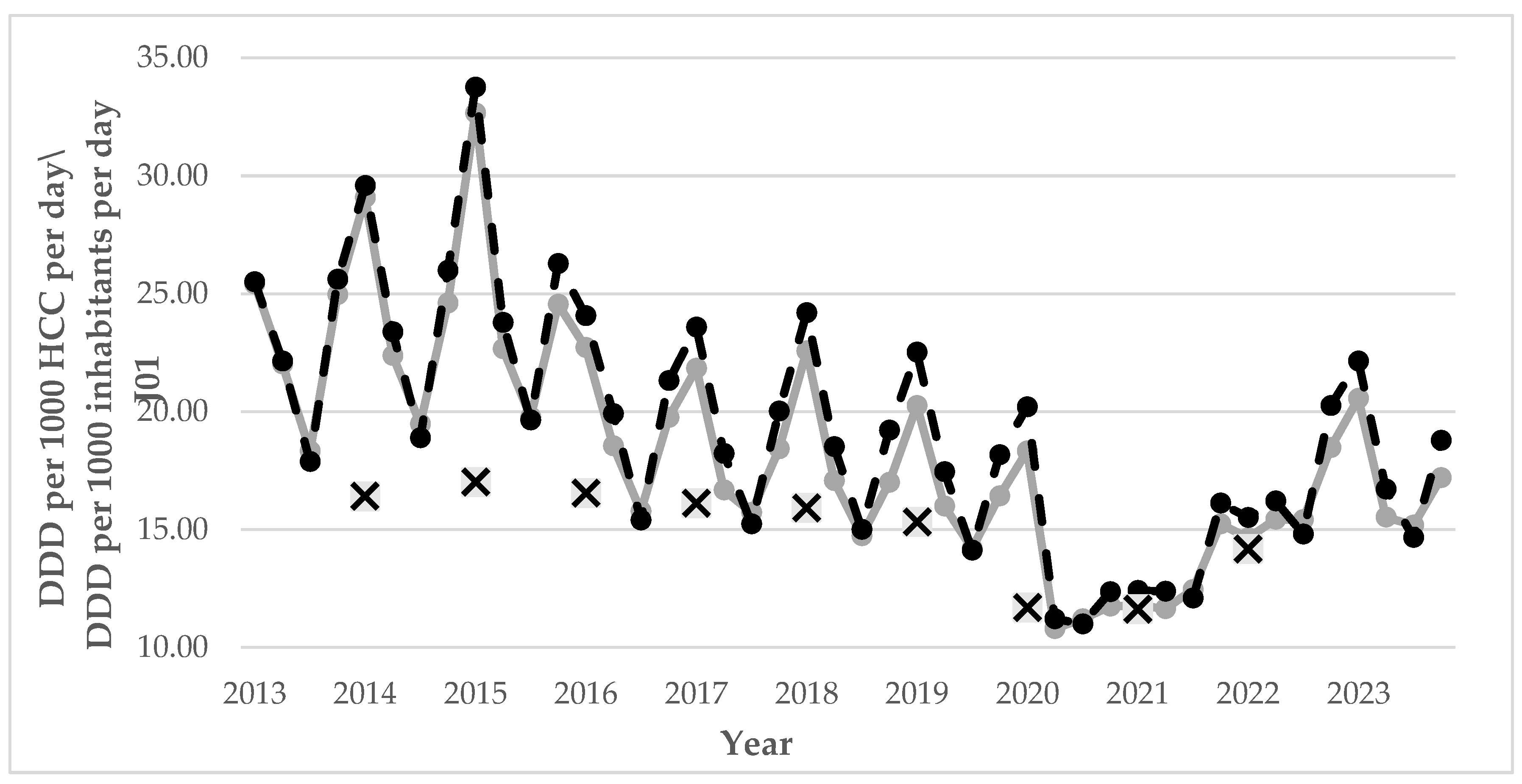

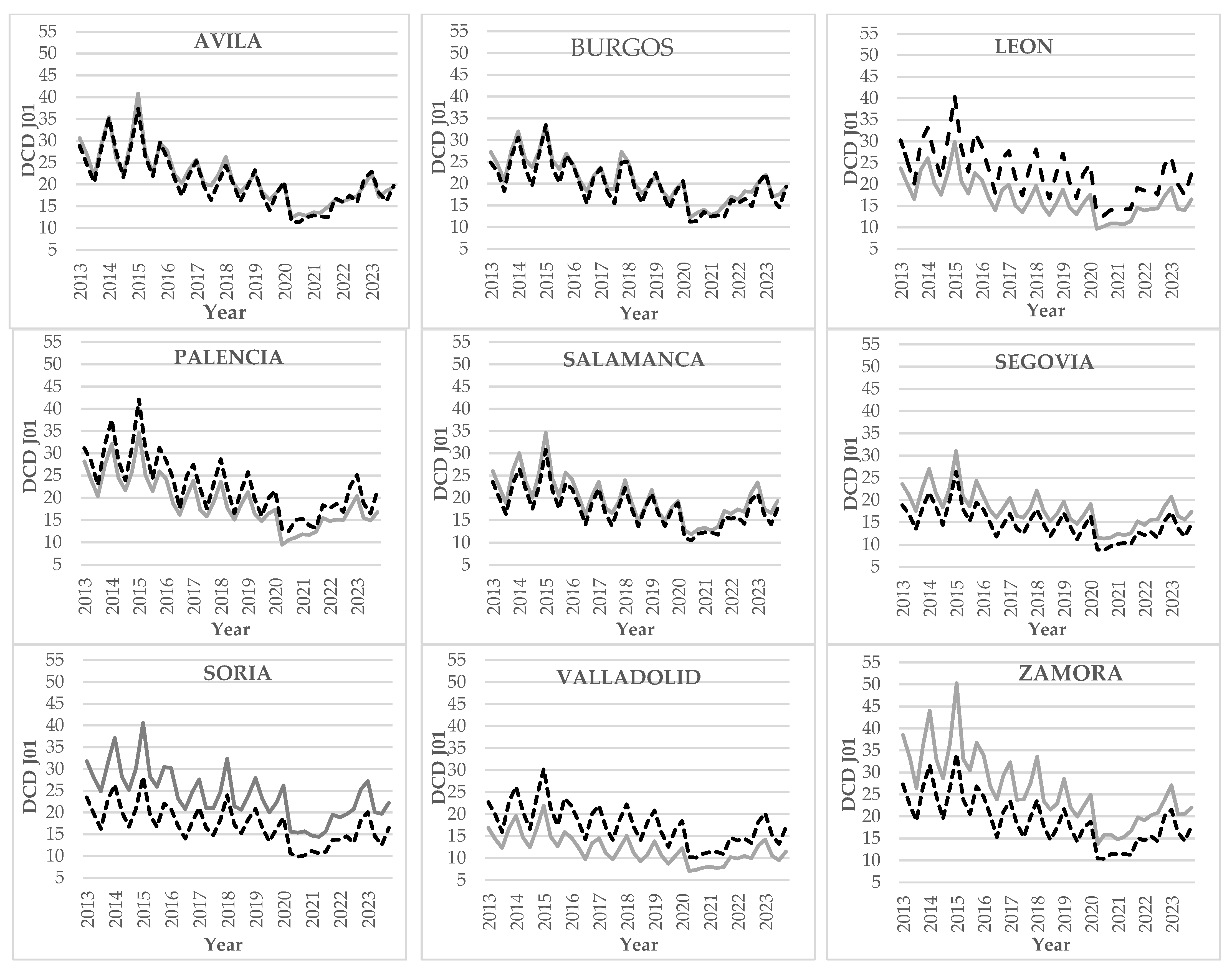

2.2. Prescriptions of Anti-Microbials for Systemic Use (J01).

2.3. Prescription Rates of Pharmacological Therapeutic subgroups

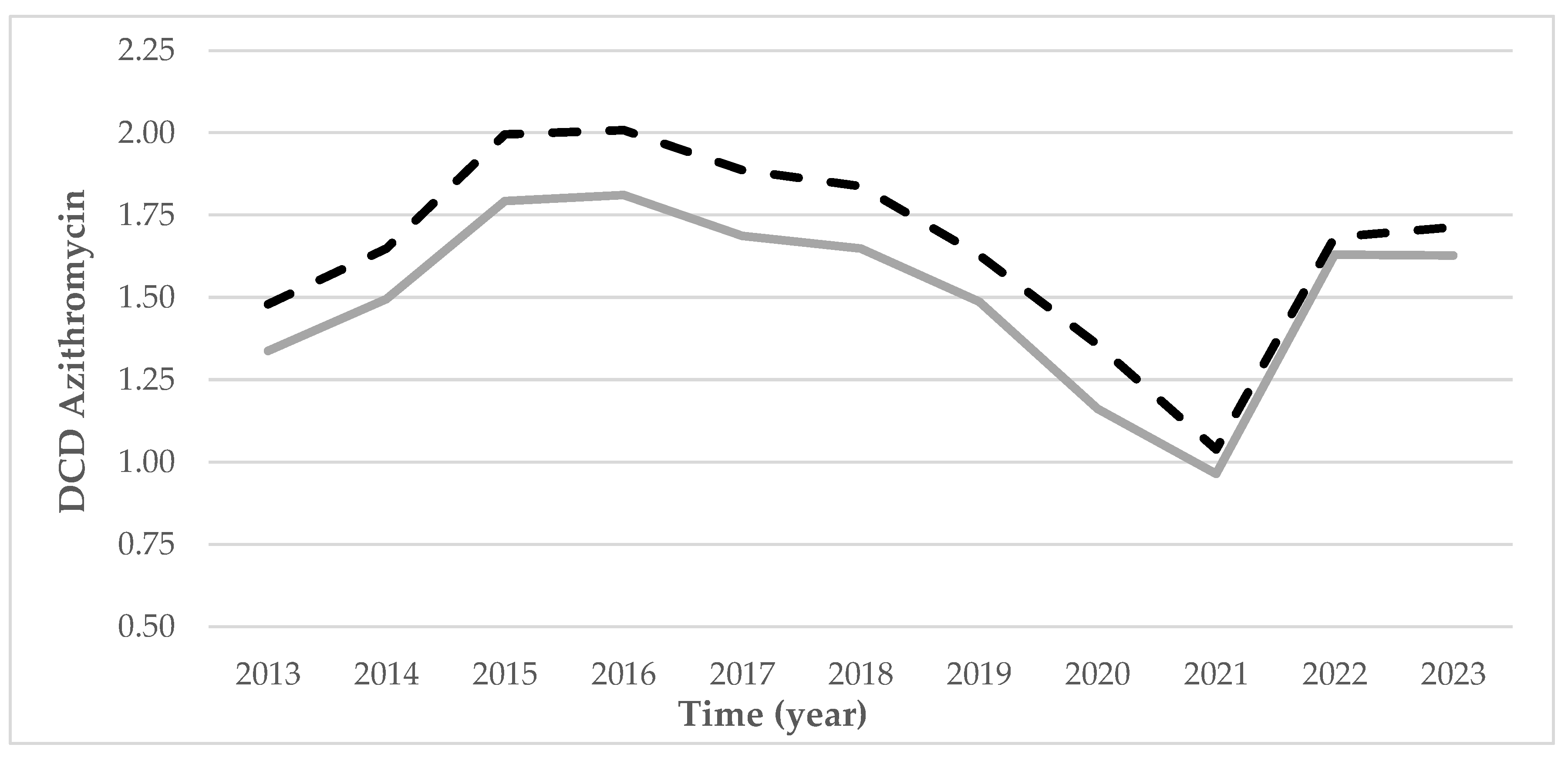

2.4. Prescription Rates of Azithromycin

2.5. Qualitative Indicators (Choice of Antibiotic)

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations of the Study and Future Lines of Work

4. Materials and Methods

- -

- -

- Percentage DDDs of fluoroquinolones (J01MA). Fluoroquinolones are used to treat respiratory and urinary infections, although they are not included in front line antibiotic treatment in Primary Health Care. In view of the failure of frontline antibiotics, their use must be reduced to very specific cases, due to the high levels of antibiotic resistance [20,21]. The following formula was used for its calculation:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Anti-Microbial Resistance |

| ATC | Anatomic, Therapeutic, Chemical |

| BHC | Basic Health Centres |

| DCD | DDDs per 1000 HCC per day |

| DDDs | Defined Daily Doses |

| HCC | Health-Care Card |

| J01 | Anti-microbials for systemic use |

| PRAN | Plan Nacional frente a la Resistencia a los Antibióticos [National Plan to combat Antibiotic Resistance]. |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| 1 | DCD: DDDs per 1000 HCC per day. |

References

- Werner, G.; Abu Sin, M. ‘Antimicrobial Resistance Is Invisible. I Am Not.’ Eurosurveillance 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho Silvas LA Resistencia Bacteriana, Una Crisis Actual. Rev Esp Salud Publica 2023, 97, 1–10.

- Aslam, B.; Khurshid, M.; Arshad, M.I.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.; Yasmeen, N.; Shah, T.; Chaudhry, T.H.; Rasool, M.H.; Shahid, A.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. The Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios Plan Estratégico 2022-2024 Del Plan Nacional Frente a La Resistencia a Los Antibióticos (PRAN); 2022.

- Sánchez-Herrero, H.; Solaz-García, Á.; Pinilla-González, A.; Martínez-Sánchez, E.V.; Santágueda-Balader, P.; Cernada-Badía, M. Características Epidemiológicas Del Uso de Antimicrobianos En Atención Primaria En España: Un Estudio a Nivel Nacional. Rev Esp Quimioter 2025, 38, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Índice de Envejecimiento. INE . Available online: https://ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=1418 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Álvarez, M.; Eiros, J.M.; Pastor, E.; Sierra, E. Consumo de Antibióticos de Uso Sistémico En La Comunidad de Castilla y León. Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN 2011, 37, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcilla Vázquez, C.; Ríos Laorden, J.; Lloret Callejo, Á.; Tejada Cifuentes, F.; Tirado Peláez, M.J.; Párraga-Martínez, I. Evolución de Prescripción Antibiótica En Atención Primaria Según Indicadores Del PRAN (Plan Nacional Frente a La Resistencia a Los Antibióticos). An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2025, 102, 503840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Consumo y Bienestar Social Plan Nacional Frente a Las Resistencias Antibióticos (PRAN). Programas de Optimización de Uso de Antibióticos (PROA); 2017;

- Llor, C. Uso Prudente de Antibióticos y Propuestas de Mejora Desde La Atención Primaria. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2010, 28, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Urrusuno, R.; Flores-Dorado, M.; Vilches-Arenas, A.; Serrano-Martino, C.; Corral-Baena, S.; Montero-Balosa, M.C. Adecuación de La Prescripción de Antibióticos En Un Área de Atención Primaria: Estudio Descriptivo Transversal. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2014, 32, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios Consumos Antibióticos Sector Comunitario Por Comunidades Autónomas | PRAN. Available online: https://www.resistenciaantibioticos.es/es/lineas-de-accion/vigilancia/mapas-de-consumo/consumo-antibioticos-humana/consumos-antibioticos-extrahospitalarios-por-comunidades (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Antibiotic Use in the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2021, 27, 646–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Base de datos de usuarios y tarjeta sanitaria de Sacyl Población de Tarjeta Sanitaria. Available online: https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/transparencia/es/transparencia/sanidad-cifras/informes-estadisticos/ordenacion-alfabetica/poblacion-tarjeta-sanitaria (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) Plan Estratégico y de Acción Para Reducir El Riesgo de Selección y Diseminación de La Resistencia a Los Antibióticos; 2014.

- Nicieza García, M.L.; Pérez Solís, P.; Gómez de Oña, C.; Suárez Gil, P.; Rolle Sóñora, V.; Suárez Mier, B. Consumo de Antibióticos En Atención Primaria En Población Adulta de Asturias Durante El Periodo 2014-2020. Aten Primaria 2022, 54, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.; Ochoa, C.; Brezmes, M.F.; López-Urrutia, L.; Rivas, N. Correlación Entre La Prescripción de Antibióticos y El Descenso de Las Resistencias a Antimicrobianos En El Área de Salud de Zamora. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2009, 27, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios Plan Nacional Frente a La Resistencia a Los Antibióticos (PRAN) 2025-2027. Available online: https://resistenciaantibioticos.es/es/publicaciones/plan-nacional-frente-la-resistencia-los-antibioticos-pran-2025-2027 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Dirección Técnica de Asistencia Farmacéutica Gerencia Regional de Salud Indicadores de Prescripción de Antibióticos; 2018.

- Rosa Albañil, J.C.J.M. a C.R.F.U.C. de la F.A.G.I.G.J.M.I.R.M. Indicadores de Uso de Antibióticos En Atención Primaria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García Ortiz, A. Prescripción de Antibióticos En Atención Primaria. Available online: https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/portalmedicamento/en/terapeutica/ojo-markov/prescripcion-antibioticos-atencion-primaria (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- World Heath Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Ripoll Lozano, M.Á.; Jiménez Arce, J.I.; Pedraza Dueñas, A. Variabilidad En La Prescripción de Antibióticos En La Provincia de Ávila. Revista Española de Quimioterapia 2007, 20, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Miguélez Ferreiro, S.; Moreno Sánchez, E.; Gutiérrez de Antonio, M.; Hernando Real, S. Antibiotic Prescribing and Changes in Antimicrobial Resistances in the Health Area of Segovia (Spain) during the Period between 2007 and 2011. Revista Española de Quimioterapia, ISSN-e 0214-3429, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2014 2014, 27, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- García, E.P.; Eiros Bouza, J.M.; Mayo Iscar, A. Análisis de La Variabilidad Geográfica Del Consumo de Antibióticos de Uso Sistémico En La Provincia de Valladolid. Medicina General 2002, 45, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Fernández, M.E.; Bachiller Luque, M.R.; Vázquez Fernández, M.J.; Pastor García, E.; Eiros Bouza, J.M. Variability in Antibiotic Prescription in the Pediatric Population of Castile and Leon (Spain) from 2001 to 2005 in Relation to Urban or Rural Setting. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2007, 67, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle-Miguel, L.; Riaño, G.M.; Carbajo, A.I.I.; Álvarez, M.A.A.; Martínez, C.V.; Sánchez, G.S. Variabilidad Entre Áreas Sanitarias En El Consumo Extrahospitalario de Antibióticos de Uso Sistémico En La Población Pediátrica Del Principado de Asturias, España (2005-2018). Revista Española de Quimioterapia 2021, 34, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalina Serna, M.; Ribes, E.; Real, J.; Galván, L.; Gascó, E.; Godoy, P. Alta Exposición a Antibióticos En La Población y Sus Diferencias Por Género y Edad. Aten Primaria 2011, 43, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malo, S.; José Rabanaque, M.; Feja, C.; Jesús Lallana, M.; Aguilar, I.; Bjerrum, L. High Antibiotic Consumption: A Characterization of Heavy Users in Spain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2014, 115, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serna, M.C.; Real, J.; Ribes, E.; Marsal, J.R.; Godoy, P.; Galván, L. Factors Determining Antibiotic Prescription in Primary Care. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2011, 29, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallana-Alvarez, M.J.; Feja-Solana, C.; Armesto-Gómez, J.; Bjerrum, L.; Rabanaque-Hernández, M.J. Outpatient Antibiotic Prescription in Aragón and the Differences by Gender and Age. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2012, 30, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarría-Santamera, A.; Prado-Galbarro, J.; Ramallo-Farina, Y.; Quintana-Díaz, M.; Martínez-Virto, A.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Utilización de Los Servicios de Urgencias En Zonas Rurales y Urbanas. Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN 2015, 41, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle-Miguel, L.; Iglesias Carbajo, A.I.; Modroño Riaño, G.; Pérez Méndez, C.; García García, E.; Rodríguez Nebreda, S.; Solís Sánchez, G. Evolution of Antibiotic Consumption in Pediatric Outpatients of Asturias, Spain (2005–2018). An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2021, 95, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Cancela, O.; Souto-Lopez, L.; Vazquez-Lago, J.M.; Lopez, A.; Figueiras, A. Factors Determining Antibiotic Use in the General Population: A Qualitative Study in Spain. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0246506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nova, I.P. Enfermería Se Incorpora al Plan Nacional de Resistencia a Antibióticos. Redacción Médica, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, S.S. e I. Los Sistemas Sanitarios En Los Países de La Unión Europea. Características e Indicadores de Salud 2019; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology ATC Classification Index with DDDs: Structure and Principles. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/atc/ structure_and_principles/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Marcilla Vázquez, C.; Ríos Laorden, J.; Lloret Callejo, Á.; Tejada Cifuentes, F.; Tirado Peláez, M.J.; Párraga-Martínez, I. Evolución de Prescripción Antibiótica En Atención Primaria Según Indicadores Del PRAN (Plan Nacional Frente a La Resistencia a Los Antibióticos). An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2025, 102, 503840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Lobato, E.; Caro-Patón Carmona, T. Evidencia Disponible de Los Fármacos Utilizados En Pacientes Con COVID-19 (II): Hidroxicloroquina y Azitromicina Available online:. Available online: https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/portalmedicamento/es/terapeutica/ojo-markov/evidencia-disponible-farmacos-utilizados-pacientes-c-15a028 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Echeverría-Esnal, D.; Martin-Ontiyuelo, C.; Navarrete-Rouco, M.E.; De-Antonio Cuscó, M.; Ferrández, O.; Horcajada, J.P.; Grau, S. Azithromycin in the Treatment of COVID-19: A Review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2021, 19, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejeria de Cultura y Bienestar Social Decreto 32/1988 de 18 de febrero, por el que se establece la delimitación territorial de las Zonas básicas de salud en el territorio de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León; España, 1988;

| J01A | J01C | J01D | J01E | J01F | J01G | J01M | J01X | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVILA | R | 0.71 (±0.07) | 12.60 (±4.10) | 2.07 (±0.27) | 0.61 (±0.07) | 2.05 (±0.38) | 0.017 (±0.003) | 2.91 (±0.78) | 0,49 (±0,05) |

| U | 0.95 (±0.09) | 12.80 (±4.10) | 1.86 (±0.31) | 0.51 (±0.04) | 1.91 (±0.40) | 0.014 (±0.008) | 2.06 (±0.53) | 0,48 (±0,02) | |

| % DIF R-U | -25,76 | -1.57 | 11.10 | 20.26 | 7.17 | 28.13 | 41.03 | 3.42 | |

| BURGOS | R | 0.53(±0.05) | 11.84 (±3.80) | 2.24 (±0.31) | 0.40 (±0.09) | 2.55 (±0.32) | 0.004 (±0.003) | 2.41 (±0.63) | 0,59 (±0,06) |

| U | 0.73(±0.05) | 11.21 (±3.60) | 2.08 (±0.24) | 0.36 (±0.06) | 2.67 (±0.28) | 0.002 (±0.001) | 1.78 (±0.45) | 0,53 (±0,03) | |

| % DIF R-U | -27,24 | 5.57 | 7.52 | 11.69 | -4.56 | 82.15 | 35.00 | 12.81 | |

| LEON | R | 0.58 (±0.02) | 8.72 (±2.84) | 1.80 (±0.32) | 0.46 (±0.04) | 2.50 (±0.58) | 0.004 (±0.003) | 2.34 (±0.41) | 0,45 (±0,33) |

| U | 0.79 (±0.06) | 12.40 (±3.86) | 2.47 (±0.49) | 0.52 (±0.06) | 3.05 (±0.68) | 0.004 (±0.002) | 2.65 (±0.51) | 0,62 (±0,05) | |

| % DIF R-U | -38,95 | -29.59 | -26.90 | -10.50 | -18.18 | -9.52 | -12.04 | -26.57 | |

| PALENCIA | R | 0.68 (±0.06) | 12.11 (±4.48) | 1.49 (±0.32) | 0.33 (±0.03) | 1.86 (±0.32) | 0.003 (±0.001) | 1.95 (±0.44) | 0,54 (±0,06) |

| U | 0.85 (±0.07) | 14.31 (±5.10) | 1.77 (±0.33) | 0.40 (±0.06) | 2.53 (±0.37) | 0.005 (±0.002) | 2.09 (±0.42) | 0,64 (±0,07) | |

| % DIF R-U | -19,29 | -15.39 | -15.64 | -16.93 | -26.29 | -36.29 | -6.51 | -16.09 | |

| SALAMANCA | R | 0.48 (±0.05) | 10.73 (±3.38) | 2.47 (±0.46) | 0.51 (±0.10) | 2.39 (±0.44) | 0.007 (±0.001) | 2.40 (±0.56) | 0,52 (±0,09) |

| U | 0.59 (±0.07) | 9.73 (±2.92) | 2.27 (±0.33) | 0.61 (±0.09) | 2.26 (±0.41) | 0.006 (±0.002) | 1.81 (±0.47) | 0,59 (±0,06) | |

| % DIF R-U | -17,94 | 10.25 | 9.14 | -15.75 | 6.06 | 18.59 | 32.46 | -11.76 | |

| SEGOVIA | R | 0.77 (±0.05) | 10.95 (±3.15) | 1.90 (±0.16) | 0.34 (±0.06) | 1.57 (±0.26) | 0.004 (±0.002) | 1.94 (±0.45) | 0,42 (±0,05) |

| U | 0.78 (±0.10) | 8.90 (±2.49) | 1.56 (±0.12) | 0.28 (±0.06) | 1.42 (±0.22) | 0.002 (±0.002) | 1.39 (±0.34) | 0,36 (±0,03) | |

| % DIF R-U | -1,03 | 23.04 | 21.69 | 21.92 | 10.97 | 94.96 | 39.81 | 15.53 | |

| SORIA | R | 0.62 (±0.06) | 13.24 (±4.07) | 4.14 (±0.48) | 0.40 (±0.08) | 2.62 (±0.35) | 0.018 (±0.004) | 2.14 (±0.51) | 0,72 (±0,03) |

| U | 0.69 (±0.05) | 8.87 (±2.66) | 3.14 (±0.53) | 0.36 (±0.07) | 1.88 (±0.30) | 0.015 (±0.003) | 1.54 (±0.44) | 0,55 (±0,05) | |

| % DIF R-U | -10,22 | 49.24 | 31.94 | 11.50 | 39.60 | 21.34 | 39.05 | 31.06 | |

| VALLADOLID | R | 0.49 (±0.08) | 7.06 (±2.26) | 1.05 (±0.19) | 0.26 (±0.04) | 1.41 (±0.29) | 0.003 (±0.001) | 1.44 (±0.36) | 0,36 (±0,05) |

| U | 1.02 (±0.08) | 9.73 (±2.96) | 1.59 (±0.29) | 0.41 (±0.06) | 2.21 (±0.49) | 0.003 (±0.001) | 1.87 (±0.49) | 0,52 (±0,05) | |

| % DIF R-U | -52,08 | -27.40 | -33.94 | -37.76 | -36.40 | 11.27 | -23.28 | -30.61 | |

| ZAMORA | R | 0.70 (±0.07) | 14.86 (±5.72) | 3.31 (±0.43) | 0.70 (±0.17) | 2.67 (±0.49) | 0.008 (±0.004) | 3.24 (±0.94) | 0,59 (±0,05) |

| U | 0.74 (±0.07) | 10.81 (±3.92) | 2.18 (±0.23) | 0.47 (±0.07) | 2.28 (±0.42) | 0.010 (±0.007) | 2.01 (±0.59) | 0,48 (±0,02) | |

| % DIF R-U | -5,81 | 37.46 | 51.68 | 47.10 | 16.85 | -22.28 | 61.13 | 22.60 | |

| CASTILE & LEON | R | 0.57 (±0.03) | 10.41 (±3.40) | 2.02 (±0.26) | 0.43 (±0.05) | 2.14 (±0.37) | 0.006 (±0.001) | 2.22 (±0.51) | 0,49 (±0,04) |

| U | 0.81 (±0.05) | 10.90 (±3.44) | 2.04 (±0.28) | 0.45 (±0.06) | 2.41 (±0.40) | 0.005 (±0.002) | 1.98 (±0.48) | 0,54 (±0,03) | |

| % DIF R-U | -29,87 | -4.45 | -0.96 | -4.23 | -11.24 | 27.69 | 11.99 | -9.99 | |

| DCD RURAL | DCD URBAN | % DIF R-U | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ÁVILA | 1.419 (± 0.295) | 1.194 (± 0.280) | 18.768 |

| BURGOS | 1.934 (± 0.263) | 1.961 (±0.251) | -1.371 |

| LEÓN | 1.942 (± 0.425) | 2.354 (± 0.499) | -17.502 |

| PALENCIA | 1.149 (± 0.239) | 1.432 (± 0.268) | -19.782 |

| SALAMANCA | 1.757 (± 0.342) | 1.508 (± 0.294) | 16.485 |

| SEGOVIA | 0.879 (± 0.176) | 0.714 (± 0.141) | 23.135 |

| SORIA | 1.801 (± 0.275) | 1.235 (± 0.222) | 45.823 |

| VALLADOLID | 0.909 (± 0.181) | 1.439 (± 0.320) | -36.823 |

| ZAMORA | 1.830 (± 0.334) | 1.618 (± 0.359) | 13.040 |

| CASTILE & LEON | 1.513 (± 0.264) | 1.661 (±0.289) | -8.937 |

| Year | AV | BU | LE | PA | SA | SE | SO | VA | ZA | CYL | C&L PRAN | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 26.28 | 23.43 | 23.91 | 26.73 | 21.68 | 19.09 | 24.87 | 18.55 | 27.31 | 22.66 | ||

| 2014 | 28.24 | 25.47 | 25.12 | 28.16 | 23.11 | 20.50 | 25.60 | 19.80 | 29.00 | 24.13 | 18.94 | 16.42 |

| 2015 | 29.31 | 26.13 | 27.18 | 29.43 | 24.38 | 21.72 | 26.49 | 20.80 | 30.23 | 25.36 | 19.99 | 17.01 |

| 2016 | 22.53 | 20.39 | 21.14 | 21.85 | 19.00 | 16.58 | 21.10 | 16.57 | 23.16 | 19.71 | 19.86 | 16.54 |

| 2017 | 21.16 | 19.60 | 19.60 | 20.80 | 18.17 | 16.22 | 20.62 | 15.89 | 21.86 | 18.75 | 19.18 | 16.10 |

| 2018 | 20.63 | 19.90 | 19.21 | 20.44 | 18.12 | 16.35 | 21.62 | 15.75 | 20.80 | 18.59 | 19.11 | 15.91 |

| 2019 | 18.53 | 18.30 | 18.88 | 18.75 | 17.28 | 15.36 | 20.05 | 14.54 | 19.58 | 17.45 | 18.08 | 15.31 |

| 2020 | 14.27 | 14.32 | 14.27 | 13.87 | 13.47 | 12.18 | 15.31 | 11.13 | 14.40 | 13.36 | 13.80 | 11.68 |

| 2021 | 14.18 | 13.71 | 13.86 | 14.02 | 13.45 | 12.03 | 13.89 | 10.88 | 13.82 | 13.04 | 13.36 | 11.61 |

| 2022 | 17.60 | 17.11 | 17.69 | 17.34 | 16.84 | 14.55 | 18.08 | 13.61 | 17.84 | 16.39 | 16.70 | 14.17 |

| 2023 | 19.24 | 18.24 | 19.07 | 18.70 | 17.90 | 15.94 | 19.13 | 14.71 | 19.21 | 17.62 | n.a. | 15.26 |

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 109,89 | 112,63 | 114,69 | 116,33 | 118,36 | 120,56 | 123 | 125,82 | 129,16 | 133,64 | 137,33 |

| Castile & Leon | 179,36 | 182,94 | 185,38 | 188 | 191,2 | 194,49 | 198,29 | 202,26 | 205,66 | 212,89 | 217,18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).