Introduction

The human musculoskeletal system, the largest system in the human body, is prone to various types of pain [

1]. Musculoskeletal pain affects 80% of the population [

2]. Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) is a common musculoskeletal disorder with an 85% one-time prevalence [

3,

4]. It has a significant economic toll, with costs reaching US

$522 million in Canada and US

$57.51 million in the USA from 2002 to 2005 [

5]. In Saudi Arabia, approximately 69% of the population experience symptoms of MPS at some points in their lives [

6].

The most widely accepted definition of MPS, established by Simons and Travell in 1983, is regional pain linked to myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) [

7]. MTrPs are commonly found in the upper back, with 38%–65% located in the trapezius muscle [

8]. These MTrPs are postulated to arise from trauma or overuse, leading to local energy crises and motor endplate dysfunction, which result in continuous muscle contraction and local hypoxia [

9]. MTrPs exhibit distinctive characteristics, such as tender points, palpable taut bands, referred pain, local twitch response and/or restricted range of motion [

10].

Physiotherapy treatments such as manual therapy [

11], therapeutic exercises [

12] and dry needling [

11,

13] have alleviated pain and functional disability in patients with MTrPS. Dry needling was developed by Karel Lewit in 1979 [

14,

15] and has two primary forms in terms of depth: superficial and deep [

16]. Superficial dry needling involves inserting the needle into the skin at a depth of 5–10 mm without making it reach the MTrPs, whereas deep dry needling involves deep skin penetration into the muscle to target the MTrPs [

17,

18]. Each of these dry-needling techniques has a different suggested mechanism for its effect on MTrPs [

10,

17].

Several clinical studies have compared the effectiveness of deep dry needling with that of superficial dry needling in patients with neck pain [

19,

20,

21,

22]. These studies obtained contradictory results. A systematic review with a meta-analysis by Griswold et al. (2019) compared the effectiveness of deep dry needling with that of superficial dry needling or acupuncture in treating painful spinal disorders. The review included 12 quasi-experimental and randomised clinical trials (RCTs). Of these, only two studies [

21,

22] compared the effectiveness of deep dry needling with that of superficial dry needling on upper-trapezius MTrPs, and their results were contradictory [

18]. To our knowledge, the systematic review by Griswold et al. (2019) has been the only one that compared the effectiveness of deep dry needling with that of superficial dry needling in patients with MTrPs. However, clinical trials have emerged after the publication of this systematic review. Thus, the current systematic review was conducted to compare the effects of deep and superficial dry needling on pain and functional-disability reduction in adults with neck pain demonstrating MTrPs.

2. Materials and Methods

Protocol Registration

This review was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on September 19, 2024 (CRD42024587994). It followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [

23].

Eligibility Criteria

RCTs involving adult patients with neck pain and upper-trapezius MTrPs that compared the effects of deep and superficial dry needling and used pain intensity and functional disability as primary outcome measures were included in the current systematic review. Only studies published in the English language were considered. Studies that included individuals with radiculopathy, whiplash injury or post-surgery or who used analgesic medications or had been treated with other physiotherapy interventions were excluded.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed by a health sciences librarian and reviewed by the primary investigator (AA). Two independent reviewers (AAL and AS) simultaneously searched the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, Google Scholar, Dimensions and OpenAlex databases from inception to September 22, 2024. The keywords included ‘neck pain’, ‘cervical pain’, ‘superficial dry needling’, ‘deep dry needling’, ‘trigger points’ and ‘MPS’. The Boolean ‘AND’ operator was employed to combine subjects, while the ‘OR’ operator was used to link headers. The Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist was followed to develop an electronic search strategy for the literature [

24]. The reference lists of studies were also searched manually for additional relevant studies. Details of the search strategy are attached in appendix A.

Study Selection

The studies identified during the search were imported into the Zotero 7.0.7 reference manager software (Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University, Virginia, USA). After eliminating duplicates using Zotero’s ‘Duplicate Items’ and manual review in the Excel sheet, AAL and AS screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility. They then independently screened the full-text articles. If there were discrepancies between the results obtained by the two reviewers, a third reviewer (AA) was consulted.

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of the selected studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool for randomised trials, which included five domains: randomisation process, deviation from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement and selection of reported results. Studies were classified as either having a low risk of bias (1), having some risk-of-bias concerns (2) or having a high risk of bias (3) according to the established criteria [

25].

Data Extraction and Synthesis

AAL and AS independently extracted the following data from each eligible study: author(s), year of publication, participants’ characteristics, diagnostic criteria, interventions, number of sessions, follow-ups, outcome measures and main findings.

Evidence synthesis was performed according to the best-evidence synthesis principles outlined by Slavin, 1995 [

26]. Owing to the clinical variability among the included studies in needle insertion depth, session frequency, follow-up lengths and outcome measurement tools, quantitative synthesis of data through meta-analysis was impracticable. The results were summarised descriptively, emphasising the identification of trends and patterns regarding the efficacy of deep and superficial dry needling in patients with neck pain. Increased emphasis was placed on studies with a low risk of bias and a more rigorous methodology. The synthesis emphasised the clinical importance of the interventions when applicable, using both qualitative patterns and quantitative results from high-quality studies.

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS) (version 29.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for data analysis. The inter-rater agreements between the reviewers for article screening and risk-of-bias assessment were calculated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) and the percentage of agreement, respectively. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient values are classified as no (≤ 0), none-to-little (0.01–0.20), reasonable (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80) and almost perfect agreement (0.81–1.00). A 95% confidence interval (CI) for κ was established to evaluate the accuracy of the agreement estimate. Mean differences (MD’s) and 95% CIs were reported, if applicable, to estimate the improvements in outcome measures.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

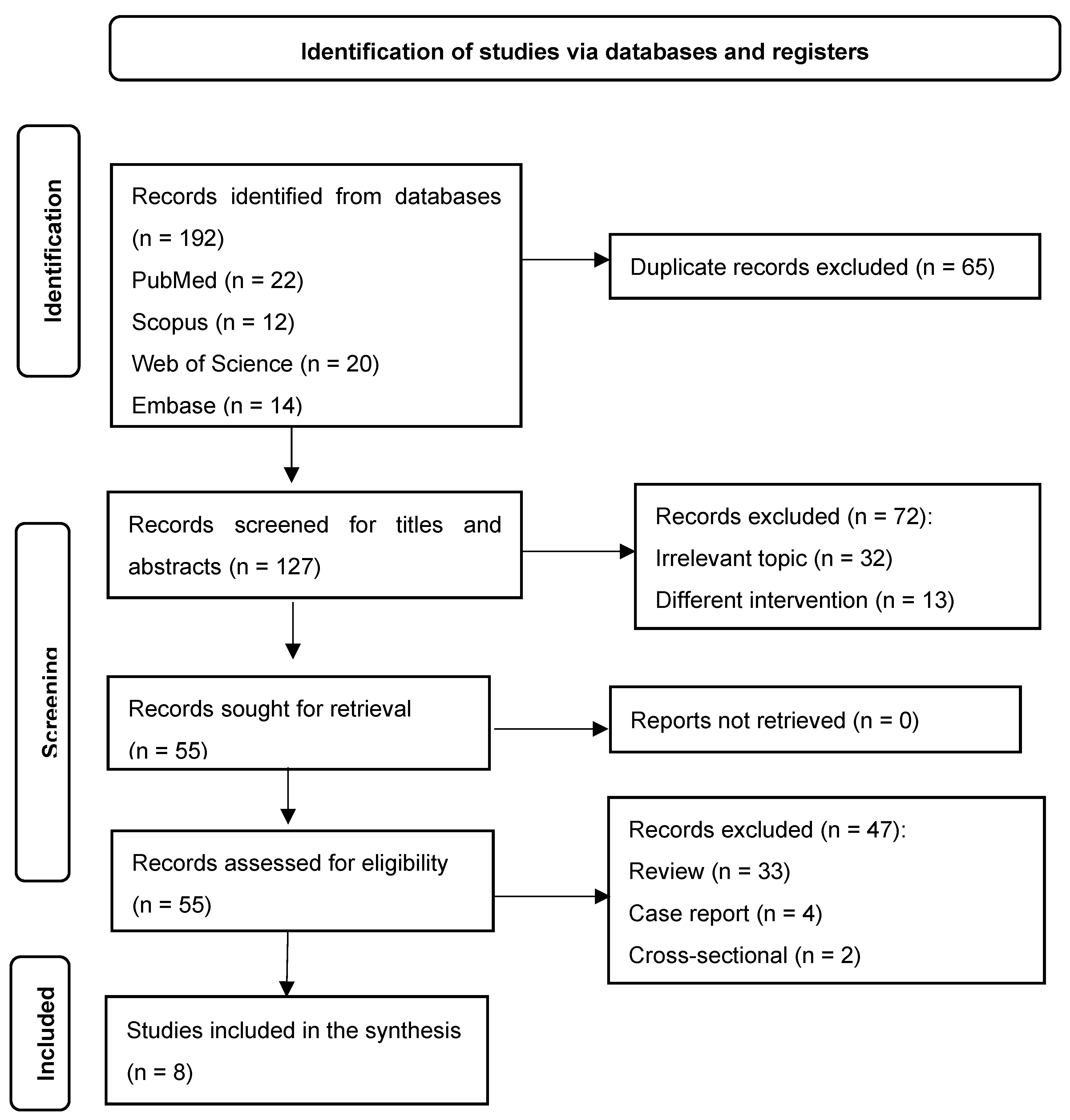

Of the 192 identified records, 127 were screened (

Figure 1). Eight studies were critically appraised in this review. Of these studies, seven [

19,

20,

22,

27,

28,

29,

30] were identified via databases, and one [

21] was identified via manual research. The inter-rater agreement for screening was perfect (κ = 1.00; 95% CI 1.00, 1.00;

Table 1). There were no discrepancies between the two reviewers, indicating that there were no instances in which one reviewer included an article while the other excluded it. The percentage of agreement for screening the title and abstract was 100% (8/8 studies).

Table 1.

Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers for article screening.

Table 1.

Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers for article screening.

| Measure |

Value |

| Total number of articles screened |

127 |

| Articles included by both reviewers |

55 (43.3%) |

| Articles excluded by both reviewers |

72 (56.7%) |

| Articles with disagreements |

0 (0%) |

| Percentage of agreement |

100% |

| Cohen’s kappa (κ) |

1.00 |

| 95% confidence interval for kappa |

1.00–1.00 |

| Statistical significance (p-value) |

< 0.001 |

Table 2.

Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers for risk-of-bias assessment.

Table 2.

Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers for risk-of-bias assessment.

| Domain |

Percentage of agreement (%) |

Cohen’s kappa (κ) |

95% Confidence interval (CI) |

P-value |

| Domain 1 |

87.5% |

0.73 |

0.28–1.00 |

0.009 |

| Domain 2 |

100% |

1.00 |

1.00–1.00 |

0.005 |

| Domain 3 |

100% |

1.00 |

1.00–1.00 |

0.005 |

| Domain 4 |

100% |

1.00 |

1.00–1.00 |

0.000 |

| Domain 5 |

87.5% |

0.75 |

0.30–1.00 |

0.028 |

| Overall |

87.5% |

0.78 |

0.646–1.00 |

0.002 |

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 3 summarises the data extracted from the eight studies included in the current systematic review [

19,

20,

21,

22,

27,

28,

29,

30]. A total of 525 participants were recruited. All studies compared the effects of deep and superficial dry needling. Six of the studies measured both pain intensity and functional disability [

19,

20,

22,

28,

29,

30] and two studies measured only pain intensity using outcome measures such as the visual analogue scale (VAS) and conditional pain modulation (CPM) [

21,

27]. Pressure pain threshold (PPT) was measured in three studies [

27,

29,

30], four-point pain intensity rating scale in one study [

22], self-reported pain (NRS-101) in one study[

29], conditioned pain modulation (CPM) in one study [

27], and headache index (HI) and trigger point tenderness in one study [

22] . The Neck Disability Index (NDI) was measuered in three studdies [

19,

20,

28] and Functional Rating Index (FRI) in one study [

22]. Other outcome measures including cervical range of motion (CROM) that was measured in four studies [

19,

22,

28,

30], maximal isometric muscle force (Fmax) and rate of force development (RFD) in one study [

29], surface electromyography (sEMG) in one study [

20], cervical motor control (CMC) in one study [

28] and ultrasonic evaluation in one study [

21]. The characteristics of interventions using deep or superficial dry needling varied among the studies (see table 3 below). Thus, the results of these studies could not be pooled in a meta-analysis due to heterogeneity.

3.3. Risk of Bias

Two of the eight RCTs [

27,

28] had a low risk of bias. Four RCTs [

20,

21,

29,

30] were rated as having some risk-of-bias concerns because of a lack of randomisation or selection of reported outcomes. Two trials [

19,

22] had a high risk of bias due to a lack of randomisation, bias due to deviation from intended treatments and bias in outcome measurement. A common strength across all eight RCTs was the low risk of bias due to missing outcome data and outcome measurements. Six RCTs [

19,

20,

21,

22,

29,

30] had either some risk-of-bias concerns or a high risk of bias due to randomisation (

Table 4).

3.4. Intervention Protocol

Variability was observed in both the deep and superficial dry-needling techniques in the trials. For deep dry needling, Sedighi et al., 2017 [

22] described the procedure only as deep needling for trigger points and kept the needle inserted into the skin for 15 min before removal. Ezzati et al., 2018 [

19] and Sarrafzadeh et al., 2018 [

21] used 50-mm-long and 0.25-mm-diameter needles, inserting them into the skin 8 times, rapidly moving them back and forth without making them exit the skin and then keeping them in situ for 5 min. Chys et al., 2023 [

27], Hoseininejad et al., 2023 [

20] and Navarro et al., 2022 [

30] used 40-mm-long and 0.2- to 0.25-mm-diameter needles and performed 8–10 in-and-out movements. Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2019 [

28] used 25 mm × 0.25 mm needles for 8–10 in-and-out movements, whereas Myburgh et al., 2012 [

29] used a 25-mm-long needle and repeatedly inserted it into the skin and rotated it clockwise for 90 s. To sum up, for deep dry needling, a 0.2- to 0.25-mm-diameter needle was used, which was inserted into the skin up to a depth of 25–50 mm for 1.5–15 min and either kept inserted during the entire session or inserted and removed 8–10 times.

For superficial needling, Navarro et al., 2022 [

30] described subcutaneous needle insertion and performed three needle rotations with 3-min intervals. Sedighi et al., 2017 [

22] inserted the needle subcutaneously and kept it in place for 15 min before removal. Ezzati et al., 2018 [

19] and Sarrafzadeh et al., 2018 [

21] inserted a 0.25-mm-diameter needle into the skin up to a depth of 5 mm (distance of the needle from the plastic tube) and rapidly moved it back and forth 8 times, without making it exit the skin, and then kept it in situ for 5 min. Myburgh et al., 2012 [

29] repeatedly inserted a 5- to 10-mm-long and 0.25-mm-diameter needle into the skin superficially and rotated it clockwise for 90 s. Hoseininejad et al., 2023 [

20] inserted a 0.2-mm-diameter needle into the skin up to a depth of 13 mm and kept it in place for 2–3 min. Chys et al., 2023 [

27] inserted the needle subcutaneously and performed in-and-out movements 10 times. Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2019 [

28] employed a superficial needle insertion technique using a 0.25-mm-diameter needle at a depth of 15 mm, swiftly moving the needle in and out 10 times. In summary, superficial dry needling using a 0.2- to 0.25-mm-diameter needle was performed up to a depth of 5–15 mm for 1.5–15 min, either keeping the needle underneath the skin for the entire session or inserting and removing it 10 times.

3.5. Intervention Duration

Six of the eight studies applied only one session of deep or superficial dry needling, with variations in follow-up duration: immediately [

27], 1 day [

29], 1 week [

20,

22,

30] and 1 month [

28]. Only two studies [

19,

21] applied three sessions of deep or superficial dry needling for 2 weeks.

3.6. Effect on Pain Severity

Two RCTs [

19,

20] found that pain intensity as measured by VAS was reduced significantly after both deep (MD = 2.2/10 and 2.64/10) and superficial dry needling (MD = 1.8/10 and 2.36/10), without significant differences between the two treatments (p > 0.05). In Sarrafzadeh et al., 2018 [

21] study, deep dry needling resulted in a greater decrease in VAS (MD = 3.98/10, 95% CI = 3.58–4.38) compared to superficial dry needling (MD = 2.0/10, 95% CI = 1.65–2.35). In Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2019 [

28] study, superficial dry needling resulted in a higher reduction in VAS (MD = 2.2/10) compared to deep dry needling (MD = 0.8/10). In their trials, Myburgh et al., 2012 [

29] and Navarro et al., 2022 [

30] used PPT to measure pain intensity and found that deep dry needling significantly reduced PPT (MD = -33.99 kPa and 0.43 kg/cm²) compared to superficial dry needling (MD = 3.49 kPa and 0.12 kg/cm²). In another trial by Chys et al., 2023 [

27], both deep and superficial dry needling improved PPT (MD = 1.03 N/cm

2 and 1.15 N/cm

2, respectively), with no significant differences between the two techniques (p > 0.05). Myburgh et al., 2012 [

29] used NRS-101 and observed a higher reduction in deep dry needling (MD = 2.18 points, 95% CI = 1.07–3.29) than in superficial dry needling (MD = 0.80 points, 95% CI = 0.48–1.12). Chys et al., 2023 [

27] found improvement in the relative CPM (at the quadriceps) in deep dry needling (MD = 13.52%, 95% CI = 0.46–26.59), but not in superficial dry needling (MD = 1.81%, 95% CI = -10.62–14.23), although there was no improvement in the absolute CPM (at the trapezius muscle) in both dry-needling approaches (p > 0.05). Sedighi et al., 2017 [

22] used trigger point tenderness and HI and observed reductions after deep dry needling (trigger point tenderness: MD = 1.49◦, 95% CI = 0.94–2.04; HI: MD = 8.07, 95% CI = 5.18–10.96) and superficial dry needling (trigger point tenderness: MD = 1.29º, 95% CI = 0.72–1.86; HI: MD = 8.20, 95% CI = 5.49–10.91), with no differences between the two techniques (p > 0.05).

3.7. Effect on Functional Disability

In two RCTs [

20,

28], functional disability was alleviated, as demonstrated by NDI, in both deep dry needling (MD = 5.2 points and 6.4 points) and superficial dry needling (MD = 7.2 points and 5.18 points). In another trial [

19], however, there was greater improvement in NDI with deep dry needling (MD = 8 points) than with superficial dry needling (MD = 2 points). Sedighi et al., 2017 [

22] used FRI and reported that both deep and superficial dry needling improved function, but higher improvement was observed in the deep-dry-needling group (MD = 28.7%, 95% CI = 20.43–36.89) than in the superficial-dry-needling group (MD = 16.4%, 95% CI = 10.86–21.94).

3.8. Effects on Other Outcome Measures

Two RCTs [

22,

30] evaluated CROM and found that it improved in both deep and superficial dry needling, but higher improvement was observed in the deep-dry-needling group. However, in both studies, the exact MD and 95% CI were not provided. Myburgh et al., 2012 [

29] used RFD and Fmax in their trial and found that both deep and superficial dry needling did not affect these outcomes (p > 0.05). Hoseininejad et al., 2023 [

20] used sEMG and found that deep dry needling increased muscle activity (MD = 9.88 root mean square [RMS]) compared to superficial dry needling (MD = 1.04 RMS). Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2019 [

28] measured CMC by testing the cervical joint position error and found that both deep and superficial dry needling improved CMC (MD = 2.1 cm and 1.8 cm, respectively), with no statistically significant differences between the two techniques (p > 0.05). Sarrafzadeh et al., 2018 [

21] used diagnostic ultrasound to measure the upper-trapezius-muscle thickness at rest, fair and normal contraction and reported that both deep and superficial dry needling enhanced muscle thickness (rest MD = 0.55 mm and 0.10 mm, respectively; fair MD = 0.49 mm and 0.12 mm; normal MD = 0.59 mm and 0.09 mm), with no significant differences between the two techniques (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the selected studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the selected studies.

| Authors |

Sample size |

Diagnostic criteria |

Interventions |

No. of sessions |

Follow-ups |

Outcome measures |

Main results |

|

Chys et al., 2023 [27] |

54 (DDN: 26, SDN: 28) |

Palpable tight band, local pain on pressure and referred pain |

DDN vs. SDN in the upper trapezius |

1 session |

Immediately post-treatment |

PPT

CPM |

There were no significant differences between DDN and SDN for PPT at local or distant sites. DDN significantly improved the relative CPM efficiency. |

|

Ezzati et al., 2018 [19] |

50 (DDN: 25, SDN: 25) |

Palpable tight band, local pain on pressure and recognised pain |

DDN vs. SDN in the upper trapezius |

3 sessions |

15 days |

VAS

NDI

ROM |

Both groups improved, but DDN showed greater gains in ROM and NDI over follow-up. |

|

Hoseininejad et al., 2023 [20] |

50 (DDN: 25, SDN: 25) |

Neck/shoulder pain with at least one active trigger point in the upper trapezius persisting for 3 months |

DDN vs. SDN in the upper trapezius |

1 session |

1 week |

VAS

NDI

sEMG

|

Both groups improved in VAS and NDI, but only DDN significantly increased sEMG. |

|

Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2019 [28] |

34 (DDN: 17, control: 17) |

Palpable tight band with local and familiar pain, and restricted ROM during full extension |

Trigger point DDN vs. sham dry needling |

1 session |

1 month |

CMC

VAS

ROM

NDI |

DDN improved pain, ROM and motor control, but there were no significant differences compared to sham DDN. |

|

Myburgh et al., 2012 [29] |

77 (symptomatic/ asymptomatic) |

Symptomatic group: significant MTrP and self-reported pain ≥ 3 on NRS-101. Asymptomatic group: no MTrP or pain (0). |

DDN vs. SDN in the upper trapezius |

1 session |

28 h post-treatment |

PPT

NRS-101

F-max

RFD |

Both groups reduced pain, but PPT decreased across all participants. There were no significant differences in F-max or RFD. |

|

Navarro et al., 2022 [30] |

180 (DDN: 60, SDN: 60, placebo: 60) |

Presence of latent MTrPs in the upper trapezius |

DDN vs. SDN vs. placebo |

1 session |

1 week |

PPT

ACROM |

Both DDN and SDN improved PPT and ROM over time, but DDN showed better ipsilateral rotation improvement at 7 days. |

|

Sarrafzadeh et al., 2018 [21] |

50 (DDN: 25, SDN: 25) |

Palpable tight band, local pain on pressure and recognition of pain by the participants |

DDN vs. SDN in the upper trapezius |

3 sessions |

15 days |

VAS

Ultrasonic evaluation |

Both DDN and SDN reduced pain and increased muscle thickness, but DDN was superior in pain reduction. |

Sedighi et al., 2017 [22]

|

30 (DDN: 15, SDN: 15) |

Unilateral neck pain spreading to the frontotemporal area, worsened by movement, restricted ROM and C1–C3 tenderness |

DDN vs. SDN in the suboccipital/upper trapezius |

1 session |

1 week |

HI

Pain intensity

TrP tenderness

ROM

FRI |

Both groups reduced HI and tenderness, but DDN showed superior improvements in ROM and FRI. |

4. Discussion

The purpose of the current systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of superficial and deep dry needling of MTrPs in reducing pain intensity and improving functional disability in patients with neck pain. MTrP formation occurs when a muscle is overloaded or subjected to repetitive strain. Sustained contraction can lead to inadequate blood flow (ischemia) in the muscle fibres, creating an ‘energy crisis’, where the muscle tissue cannot receive enough oxygen and nutrients to meet its metabolic demands. This energy crisis triggers the excessive release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in continuous muscle contraction (Barbero et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). The sustained contraction further perpetuates the cycle by compressing blood vessels, worsening ischemia and leading to the accumulation of metabolic by-products, such as lactic acid. Ultimately, this ongoing cycle results in localised pain, muscle stiffness and the formation of a myofascial trigger point [

7,

9]. This is the most widely accepted explanation of MTrP formation because it has been supported by evidence from several studies using different diagnostic modalities, such as ultrasonography, EMG and micro dialysis [

7,

31,

32,

33]. The mechanism behind the effects of deep dry needling is believed to be related to its ability to reach the MTrP, where it reduces end plate noise [

34,

35]. Additionally, the observed decrease in acetylcholine levels may lead to increased muscle blood flow and oxygenation and reduced sarcomere contracture [

34,

35]. Thus, the key factor in using deep dry needling is the mechanical stimulation of the trigger point. This stimulation leads to improvements in fibre structure, reductions in local stiffness, enhanced blood circulation, production of muscle actin and enhancement of the repair of fascia in damaged areas [

36].

The mechanism of action of superficial dry needling is postulated as stimulating Aδ nerve fibres, with the consequent release of opioid peptides from enkephalinergic inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn. These peptides then inhibit the intradorsal horn transmission of nociceptive information conveyed to the spinal cord via group IV sensory afferents from the MTrP [

17]. Thus, in superficial dry needling, mechanical stimulation is minimal and limited to just beneath the skin’s surface, not reaching the MTrP. As a result, superficial dry needling seems to have relatively low effectiveness [

21].

Our review included eight RCTs with a risk of bias ranging between low [

27,

28], with some concerns [

20,

21,

29,

30] and high [

19,

22]. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of the therapist was not feasible in the included studies, potentially introducing bias into the results. Overall, the synthesised evidence suggests that both the superficial and deep dry-needling approaches may be effective in providing short-term reductions in pain associated with MTrPs in patients with neck pain. Most of the RCTs in the current review demonstrated no difference in pain effect between deep and superficial dry needling. Our findings are similar to those of previous RCTs on other body parts, such as the lumbar spine [

37] and knee [

38], which found no significant differences between the two dry-needling approaches. However, two RCTs with some risk-of-bias concerns [

21,

29] demonstrated a statistically significant pain reduction with deep dry needling compared to superficial dry needling. Notably, the reported pain reductions in these studies (1.4 points for NRS-101 and 2.0 points for VAS) exceeded the established minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) for neck pain (1.3 for NRS-101 and 0.8 for VAS) [

39,

40], indicating potential clinical relevance. A previous systematic review examining the effects of dry needling (superficial and deep) on pain and functional-disability in people with spinal pain indicated that deep dry needling was statistically superior to superficial dry needling in reducing pain, although this difference may not be clinically meaningful [

18]. On the other hand, an RCT with a low risk of bias showed a higher pain reduction with superficial dry needling than with deep dry needling (MCID = 1.4 points) [

28]. Our findings are also similar to those of a study that compared superficial dry needling and stretching exercises with stretching exercises only or no treatment [

41]. However, to our knowledge, no other previous studies have compared superficial and deep dry needling in any musculoskeletal condition.

Regarding disability, our review also suggested that superficial or deep dry needling may be helpful in improving function. Nevertheless, only two RCTs with a high risk of bias [

19,

22] indicated that deep dry needling was superior to superficial dry needling in reducing disability, with reported improvements of 6 points for NDI and 12.26% for FRI. These reported disability reductions surpassed the previously established MCIDs for NDI (5 points) [

42,

43] and FRI (11%–12%) [

44,

45]. Our findings are also similar to a couple of previous studies that found no significant difference between deep and superficial dry needling for functional disability in people with different levels of spinal pain [

18,

46].

The variability in the application of superficial and deep dry needling among the included studies, particularly in terms of needling application, depth of needle insertion and the length of the needle used, was quite significant. However, the depth of needle insertion was more consistent among the studies for deep dry needling than superficial dry needling. Thus, there was no consensus on the optimal treatment parameters, such as needling application, length of needles used, depth of needle insertion (particularly in the superficial-dry-needling procedure), number of treatment sessions and follow-up duration.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of the current systematic review is that it followed the PRISMA protocol and every step of the guidelines recommended previously [

47]. Moreover, statistical analysis was performed and principles of best-evidence synthesis using effect size were used to determine the clinical significance of the results, taking into consideration that meta-analysis was not plausible in the current review. However, the limitations of the current review were acknowledged. First, the search was restricted to English-language studies, meaning that relevant studies in other languages could have been missed. In addition, a meta-analysis was not conducted due to the heterogeneity of the included trials. However, qualitative analysis with effect size was applied to strengthen the evidence conclusions, as stated above.

For the clinical implications of the current study’s findings, at least a single session of deep or superficial dry needling seems to be effective for short-term pain and functional-disability reduction associated with MTrPs in patients with neck pain. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because most of the included RCTs were classified as having some risk-of-bias concerns or having a high risk of bias.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that at least a single session of either deep or superficial dry needling will result in a short-term meaningful reduction of pain and functional disability associated with MTrPs in patients with neck pain. However, these findings should be treated with caution due to the heterogeneity of the treatment protocols and the high risk of bias in most of the included RCTs. For deep dry needling, we recommend the use of a 25- to 50-mm-long and 0.25-mm-diameter needle for 8–10 fast in-and-out movements. For superficial dry needling, it may be ideal to use a 5- to 15-mm-long and 0.25-mm-diameter needle for 8–10 fast in-and-out movements and then to keep it inserted for up to 15 min. These recommendations warrant further research to standardise the dry-needling treatment protocol in terms of the number of sessions, treatment duration and application technique.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AA, AS and AAL; methodology, AA and AAL; software, AAL; validation, AS, AA and AS; formal analysis, AAL and AS; investigation AAL and AS.; resources, AA; data curation, AA, AAL and AS; writing—original draft preparation, AAL; writing—review and editing, AA and AS; visualization, AAL and AA; supervision, AA; project administration, AA; no funding acquisition was needed for this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MPS |

Myofascial pain syndrome |

| MTrPs |

Myofascial trigger points |

| RCTs |

Randomised controlled trials |

| MCIDs |

Minimal clinically important differences |

Appendix A: Search Strategy

| Database |

Date of search |

Search strategy |

Results |

| PubMed |

22/09/2024 |

(("Neck Pain"[Mesh] OR "Cervical Pain"[Mesh]) AND ("Dry Needling"[Mesh] OR "deep dry needling" OR "Superficial dry needling")) AND ("Trigger Points"[Mesh] OR "Myofascial Pain Syndromes"[Mesh]) |

22

|

| Web of Science |

22/09/2024 |

TS=("Neck pain" OR "Cervical pain") AND TS=("deep dry needling" OR "Superficial dry needling") AND TS=("Trigger point*" OR "Myofascial pain syndrome") |

20 |

| Scopus |

22/09/2024 |

(TITLE-ABS-KEY ("Neck pain" OR "Cervical pain")) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("deep dry needling" OR "Superficial dry needling")) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("Trigger point*" OR "Myofascial pain syndrome")) |

12 |

| Embase |

22/09/2024 |

('neck pain' OR 'cervical pain':ab,ti,kw) AND ('deep dry needling' OR 'superficial dry needling':ab,ti,kw) AND ('trigger point*' OR 'myofascial pain syndrome':ab,ti,kw) |

14 |

| Google Scholar |

22/09/2024 |

intitle:("Neck pain" OR "Cervical pain") AND intitle:("deep dry needling" OR "Superficial dry needling") AND intitle:("Trigger point*" OR "Myofascial pain syndrome") |

51 |

| Dimensions |

22/09/2024 |

("Neck pain" OR "Cervical pain") AND ("deep dry needling" OR "Superficial dry needling") AND ("Trigger point*" OR "Myofascial pain syndrome") |

10 |

| OpenAlex |

22/09/2024 |

("Neck pain" OR "Cervical pain") AND ("deep dry needling" OR "Superficial dry needling") AND ("Trigger point*" OR "Myofascial pain syndrome") |

63 |

References

- Ailliet L, Rubinstein SM, De Vet HCW, Van Tulder MW, Terwee CB. Reliability, responsiveness and interpretability of the neck disability index-Dutch version in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ansari NN, Komesh S, Naghdi S, Fakhari Z, Alaei P. Responsiveness of Minimal Clinically Important Change for the Persian Functional Rating Index in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain.

- Baldry P. Superficial versus deep dry needling. Acupunct Med. 2002;20(2-3):78-81. Available from: http://aim.bmj.com/content/20/2-3/78.full.pdf.

- Ball A, Perreault T, Fernández-De-las-Peñas C, Agnone M, Spennato J. Ultrasound Confirmation of the Multiple Loci Hypothesis of the Myofascial Trigger Point and the Diagnostic Importance of Specificity in the Elicitation of the Local Twitch Response. Diagnostics. 2022;12(2). [CrossRef]

- Ballyns JJ, Turo D, Otto P, Shah JP, Hammond J, Gebreab T, et al. Office-based elastographic technique for quantifying mechanical properties of skeletal muscle. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(8):1209-19. [CrossRef]

- Barbero M, Schneebeli A, Koetsier E, Maino P. Myofascial pain syndrome and trigger points: Evaluation and treatment in patients with musculoskeletal pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2019;13(3):270-6. [CrossRef]

- Bennett R. Myofascial pain syndromes and their evaluation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):427-45. [CrossRef]

- Berger A, Dukes E, Martin S, Edelsberg J, Oster G. Characteristics and healthcare costs of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(9):1498-508. [CrossRef]

- Bourgaize S, Newton G, Kumbhare D, Srbely J. A comparison of the clinical manifestation and pathophysiology of myofascial pain syndrome and fibromyalgia: Implications for differential diagnosis and management. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2018;62(1):26-41.

- Ceccherelli F, Rigoni MT, Gagliardi G, Ruzzante L. Comparison of superficial and deep acupuncture in the treatment of lumbar myofascial pain: A double-blind randomized controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(3):149-53. [CrossRef]

- Chansirinukor W. Thai version of the Functional Rating Index for patients with back and neck pain: Part II responsiveness and head-to-head comparisons. Physiother Res Int. 2018 Apr;1-6. [CrossRef]

- Chys M, Bontinck J, Voogt L, Sendarrubias GMG, Cagnie B, Meeus M, De Meulemeester K. Immediate effects of dry needling on pain sensitivity and pain modulation in patients with chronic idiopathic neck pain: a single-blinded randomized clinical trial. Braz J Phys Ther. 2023;27(1):100481. [CrossRef]

- Cohen SP, Hooten WM. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ. 2017;358:j3221. [CrossRef]

- Dunning J, Butts R, Mourad F, Young I, Flannagan S, Perreault T. Dry needling: a literature review with implications for clinical practice guidelines. Phys Ther Rev. 2014;19(4):252-65. [CrossRef]

- Espejo-Antúnez L, Tejeda JFH, Albornoz-Cabello M, Rodríguez-Mansilla J, de la Cruz-Torres B, Ribeiro F, Silva AG. Dry needling in the management of myofascial trigger points: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2017;33:46-57. [CrossRef]

- Ezzati K, Sarrafzadeh J, Ebrahimi Takamjani I, Khani S. The Efficacy of Superficial and Deep Dry Needling Techniques on Functional Parameters in Subjects With Upper Trapezius Myofascial Pain Syndrome. Caspian J Neurol Sci. 2018;4(15):152-8. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Dommerholt J. International consensus on diagnostic criteria and clinical considerations of myofascial trigger points: A delphi study. Pain Med. 2018;19(1):142-50. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas C, Nijs J. Trigger point dry needling for the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: Current perspectives within a pain neuroscience paradigm. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1899-911. [CrossRef]

- Griswold D, Wilhelm M, Donaldson M, Learman K, Cleland J. The effectiveness of superficial versus deep dry needling or acupuncture for reducing pain and disability in individuals with spine-related painful conditions: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2019;27(3):128-40. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [CrossRef]

- Hoseininejad Z, Mohammadi HK, Azadeh H, Taheri N. Comparison of immediate and delayed effects of superficial and deep dry needling in patients with upper trapezius myofascial trigger points. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2023;33:106-11. [CrossRef]

- Ja AC, Jd C, Psycho WJM. Psychometric Properties of the Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in Patients With Mechanical. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(January). [CrossRef]

- Kalichman L, Vulfsons S. Dry needling in the management of musculoskeletal pain. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(5):640-6. [CrossRef]

- Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ, Cramer H. Clinically meaningful differences in pain, disability and quality of life for chronic nonspecific neck pain—A reanalysis of 4 randomized controlled trials of cupping therapy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:342-7.

- Legge D. A history of dry needling. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2014;22(3):301-7. [CrossRef]

- Lew J, Kim J. Comparison of dry needling and trigger point manual therapy in patients with neck and upper back myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Man Manip Ther. 2021;29(3):136-46. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez A, Sáez-Olmo E, Pecos-Martín D, Calvo-Lobo C. Effects of dry needling in the sternocleidomastoid muscle on cervical motor control in patients with neck pain: a randomised clinical trial. Acupunct Med. 2019;37(3):151-63. [CrossRef]

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-6. [CrossRef]

- Mi CH, Qi XY, Ding YW, Zhou J, Dao JW, Wei DX. Recent advances of medical polyhydroxyalkanoates in musculoskeletal system. Biomater Transl. 2023;4(4):234-47. [CrossRef]

- Moral OM Del. Dry needling treatments for myofascial trigger points. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2010;18(4):411-6. [CrossRef]

- Muka T, Glisic M, Milic J, Verhoog S, Bohlius J, Bramer W, Chowdhury R, Franco OH, Library M, Muka T. A 24-step guide on how to design, conduct, and successfully publish a systematic review & meta-analysis in medical research. 2019;1-25.

- Myburgh C, Hartvigsen J, Aagaard P, Holsgaard-Larsen A. Skeletal muscle contractility, self-reported pain and tissue sensitivity in females with neck/shoulder pain and upper Trapezius myofascial trigger points-a randomized intervention study. Chiropr Man Therap. 2012;20. [CrossRef]

- Näslund J, Näslund UB, Odenbring S, Lundeberg T. Sensory stimulation (acupuncture) for the treatment of idiopathic anterior knee pain. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34(5):231-8. [CrossRef]

- Navarro SM, Medina SD, Rico JMB, Ortiz MIR, Gracia MTP. Analysis and comparison of pain pressure threshold and active cervical range of motion after superficial and deep dry needling techniques of the upper trapezius muscle. Acupunct Med. 2022;40(1):13-23. [CrossRef]

- Pal U, Kumar L, Mehta G, Singh N, Singh G, Singh M, Yadav H. Trends in management of myofacial pain. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2014;5(2):109. [CrossRef]

- Pool JJM, Ostelo RWJG, Hoving JL. Disability Index and the Numerical Rating Scale for Patients With Neck Pain.

- Sabeh AM, Bedaiwi SA, Felemban OM, Mawardi HH. Myofascial Pain Syndrome and Its Relation to Trigger Points, Facial Form, Muscular Hypertrophy, Deflection, Joint Loading, Body Mass Index, Age and Educational Status. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2020;10(6):786-93. [CrossRef]

- Sachiko F, Motohiro I, Miwa N, Megumi I. Difference between therapeutic effects of deep and superficial acupuncture needle insertion for low back pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2011;7(1):37-45.

- Sánchez-Infante J, Navarro-Santana MJ, Bravo-Sánchez A, Jiménez-Diaz F, Abián-Vicén J. Is dry needling applied by physical therapists effective for pain in musculoskeletal conditions? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2021;101(3):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Sarrafzadeh J, Khani S, Ezzati K, Takamjani IE. Effects of Superficial and Deep Dry Needling on Pain and Muscle Thickness in Subject with Upper Trapezius Muscle Myofascial Pain Syndrome. J Pain Relief. 2018;7(03):4-9. [CrossRef]

- Sedighi A, Nakhostin Ansari N, Naghdi S. Comparison of acute effects of superficial and deep dry needling into trigger points of suboccipital and upper trapezius muscles in patients with cervicogenic headache. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(4):810-4. [CrossRef]

- Shah JP, Danoff JV, Desai MJ, Parikh S, Nakamura LY, Phillips TM, Gerber LH. Biochemicals Associated With Pain and Inflammation are Elevated in Sites Near to and Remote From Active Myofascial Trigger Points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):16-23. [CrossRef]

- Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: An intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(1):9-18. [CrossRef]

- Tsai CT, Hsieh LF, Kuan TS, Kao MJ, Chou LW, Hong CZ. Remote effects of dry needling on the irritability of the myofascial trigger point in the upper trapezius muscle. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(2):133-40. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Du NY, Chen C, Wang T, Wang LJ, Shi XL, Li SM, Guo CQ. Acupotomy Alleviates Energy Crisis at Rat Myofascial Trigger Points. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:5129562. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Pavón MJ, Cavero-Redondo I, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Fernández-Rodríguez R, Reina-Gutierrez S, Álvarez-Bueno C. Effect of physical exercise programs on myofascial trigger points–related dysfunctions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2020;21(11):2986-96.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Edwards J, Knowles N. Superficial dry needling and active stretching in the treatment of myofascial pain--a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2003 Sep;21(3):80-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).