Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

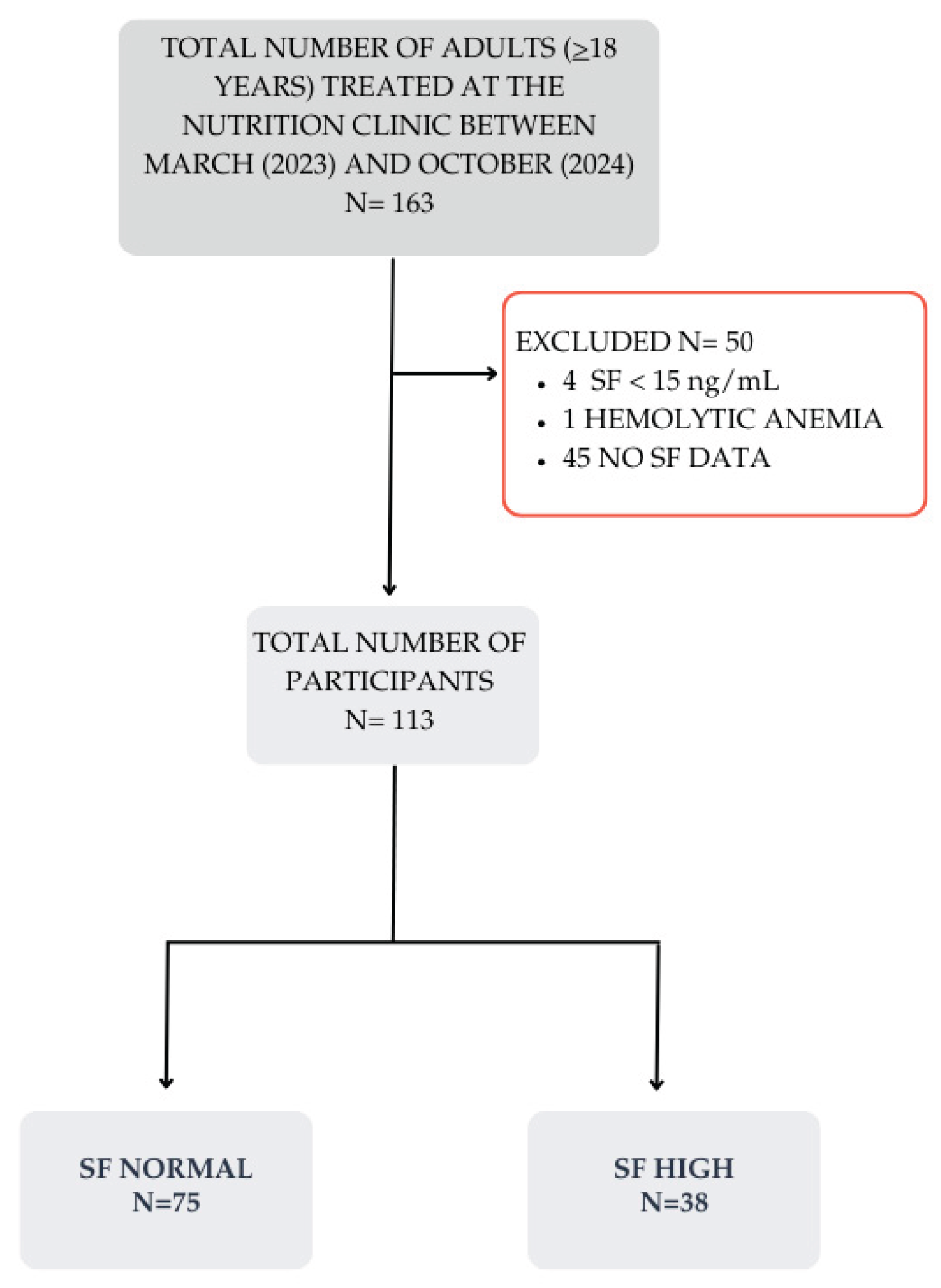

2. Materials and Methods

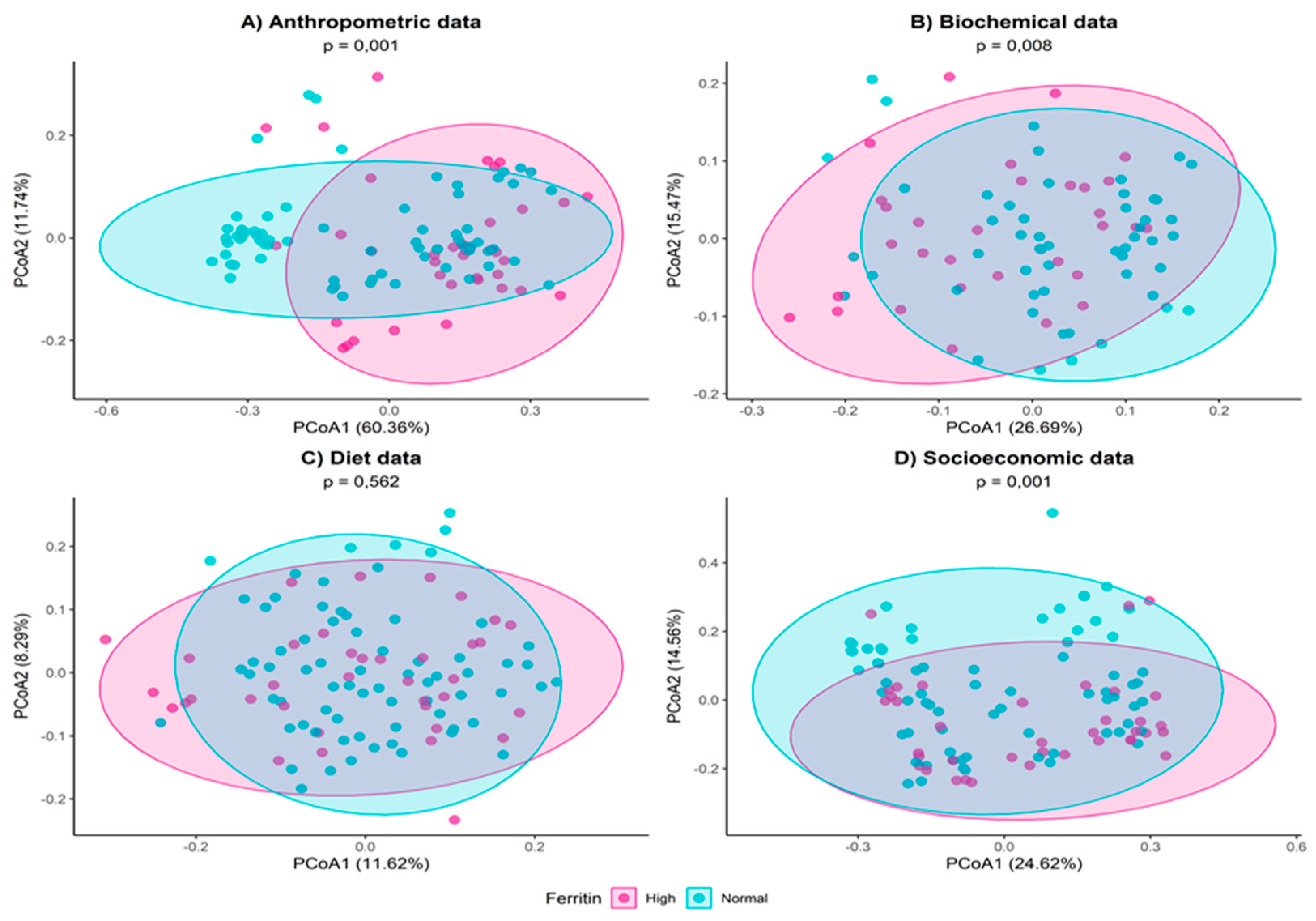

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Variable | Category | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | - | 117.5 (107.2–127) | 132 (113.2–140.2) | 0.952b |

| DBP (mmHg) | - | 74.5 (68.2–80.8) | 81 (68.5–86.8) | 0.394b |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | - | 77 (72–89) | 87 (80.2–97) | 0.127b |

| TG (mg/dL) |

- | 86 (61.5–117) | 114.5 (88.2–190.2) | 0.788b |

| TyG | - | 4.4 (4.2–4.6) | 4.6 (4.5–4.9) | 0.927b |

| TC (mg/dL) | - | 170.8 (147–192.5) | 185 (156.2–203) | 0.788b |

| HDL (mg/dL) | - | 45 (41–48) | 40 (38–44.8) | 0.909b |

| LDL (mg/dL) | - | 105.4 (81.9–124.7) | 105.7 (90.2–128.2) | 0.927b |

| AST (U/L) | - | 27 (21–34) | 29 (22–38) | 0.679b |

| ALT (U/L) | - | 20 (15–25.8) | 26 (20–35.6) | 0.630b |

| FIB4 | - | 0.7 (0.5–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.315b |

| UA (mg/dl) | - | 4.2 (3.2–4.9) | 4.8 (3.6–6.1) | 0.648b |

| ESR (mm) | - | 15 (10–24.8) | 12 (10–16) | 0.206b |

| Platelets (mil/mm3) | - | 235 (209–283) | 249 (221–266) | 0.436b |

| Leukocytes (mm3) | - | 6400 (5550–7800) | 6400 (5599.8–8950) | 0.788b |

| Rod neutrophils (mm3) | - | 57 (40–72) | 61 (0–75) | 0.836b |

| Eosinophils(mm3) | - | 144 (104–226.5) | 137 (69.2–191.2) | 0.648b |

| Segmented neutrophils (mm3) | - | 3510 (3000–4298) | 3650 (2669–4929) | 0.788b |

| Monocytes (mm3) | - | 300 (220–388) | 312 (252–456) | 0.527b |

| Lymphocytes (mm3) | - | 2280 (1912–2668.5) | 2171.,5 (2018–2606.8) | 0.927b |

| HSI | - | 34.2 (30.9–38.6) | 39.9 (35.5–45.4) | 0.788b |

| Variable | Category | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cookies, cakes | Never or rarely | 15 (20.8%) | 7 (18.4%) | 0.744a |

| Monthly | 12 (16.7%) | 4 (10.5%) | ||

| Weekly | 34 (47.2%) | 19 (50%) | ||

| Daily | 11 (15.3%) | 8 (21.1%) | ||

| Masses | Never or rarely | 5 (6.9%) | 4 (10.5%) | 0.534b |

| Monthly | 9 (12.5%) | 5 (13.2%) | ||

| Weekly | 55 (76.4%) | 25 (65.8%) | ||

| Daily | 3 (4.2%) | 4 (10.5%) | ||

| Whole grains | Never or rarely | 32 (44.4%) | 13 (34.2%) | 0.257b |

| Monthly | 3 (4.2%) | 3 (7.9%) | ||

| Weekly | 26 (36.1%) | 11 (28.9%) | ||

| Daily | 11 (15.3%) | 11 (28.9%) | ||

| Candy | Never or rarely | 12 (16.7%) | 6 (16.2%) | 0.091b |

| Monthly | 5 (6.9%) | 6 (16.2%) | ||

| Weekly | 31 (43.1%) | 20 (54.1%) | ||

| Daily | 24 (33.3%) | 5 (13.5%) | ||

| Butter, bacon, lard, lard | Never or rarely | 29 (40.8%) | 11 (29.7%) | 0.212b |

| Monthly | 3 (4.2%) | 3 (8.1%) | ||

| Weekly | 17 (23.9%) | 15 (40.5%) | ||

| Daily | 22 (31%) | 8 (21.6%) | ||

| Margarine, mayonnaise | Never or rarely | 34 (47.2%) | 14 (37.8%) | 0.428b |

| Monthly | 3 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Weekly | 20 (27.8%) | 13 (35.1%) | ||

| Daily | 15 (20.8%) | 10 (27%) | ||

| Snacks | Never or rarely | 13 (18.1%) | 7 (18.9%) | 0.426b |

| Monthly | 29 (40.3%) | 9 (24.3%) | ||

| Weekly | 28 (38.9%) | 19 (51.4%) | ||

| Daily | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Preserved food | Never or rarely | 46 (63.9%) | 21 (56.8%) | 0.8b |

| Monthly | 13 (18.1%) | 6 (16.2%) | ||

| Weekly | 12 (16.7%) | 9 (24.3%) | ||

| Daily | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | ||

| Fried foods | Never or rarely | 28 (38.9%) | 11 (29.7%) | 0.675b |

| Monthly | 10 (13.9%) | 8 (21.6%) | ||

| Weekly | 29 (40.3%) | 16 (43.2%) | ||

| Daily | 5 (6.9%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Vegetables | Never or rarely | 4 (5.6%) | 2 (5.4%) | 0.663b |

| Monthly | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | ||

| Weekly | 25 (34.7%) | 17 (45.9%) | ||

| Daily | 42 (58.3%) | 17 (45.9%) | ||

| Beans | Never or rarely | 3 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.287b |

| Monthly | 2 (2.8%) | 3 (7.9%) | ||

| Weekly | 23 (31.9%) | 15 (39.5%) | ||

| Daily | 44 (61.1%) | 20 (52.6%) | ||

| Leafy greens | Never or rarely | 3 (4.2%) | 2 (5.4%) | 1b |

| Monthly | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Weekly | 20 (27,8%) | 11 (29.7%) | ||

| Daily | 48 (66.7%) | 24 (64.9%) | ||

| Tubers | Never or rarely | 3 (4.2%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.702b |

| Monthly | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Weekly | 55 (76.4%) | 25 (67.6%) | ||

| Daily | 12 (16.7%) | 9 (24.3%) | ||

| Fruits | Never or rarely | 1 (1.4%) | 3 (8.1%) | 0.376b |

| Monthly | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | ||

| Weekly | 21 (29.2%) | 9 (24.3%) | ||

| Daily | 49 (68.1%) | 24 (64.9%) | ||

| Soft drinks, juices | Never or rarely | 28 (38.9%) | 18 (48.6%) | 0.557b |

| Monthly | 6 (8.3%) | 1 (2.7%) | ||

| Weekly | 30 (41.7%) | 13 (35.1%) | ||

| Daily | 8 (11.1%) | 5 (13.5%) | ||

| Sweetener | Never or rarely | 66 (91.7%) | 33 (89.2%) | 1b |

| Weekly | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.7%) | ||

| Daily | 5 (6.9%) | 3 (8.1%) | ||

| Diet e light | Never or rarely | 69 (95.8%) | 31 (83.8%) | 0.073b |

| Monthly | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Weekly | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Daily | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Ready-made seasonings | Never or rarely | 53 (73.6%) | 28 (75.7%) | 0.681b |

| Monthly | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Weekly | 6 (8.3%) | 3 (8.1%) | ||

| Daily | 12 (16.7%) | 4 (10.8%) | ||

| Sugar | Never or rarely | 21 (29.2%) | 15 (40.5%) | 0.024b |

| Monthly | 0 (0%) | 3 (8.1%)# | ||

| Weekly | 18 (25%) | 4 (10.8%) | ||

| Daily | 33 (45.8%) | 15 (40.5%) | ||

| Oilseeds | Never or rarely | 36 (50%) | 16 (43.2%) | 0.857a |

| Monthly | 9 (12.5%) | 6 (16.2%) | ||

| Weekly | 16 (22.2%) | 10 (27%) | ||

| Daily | 11 (15.3%) | 5 (13.5%) |

References

- Alshwaiyat, N.; Ahmad, A.; Wan Hassan, W. M. R.; Al-Jamal, H. Association between obesity and iron deficiency (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Valko, M. Importance of iron chelation in free radical-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 3460–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nairz, M.; Weiss, G. Iron in health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2020, 75, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knovich, M. A.; Storey, J. A.; Coffman, L. G.; Torti, S. V.; Torti, F. M. Ferritin for the clinician. Blood Rev. 2009, 23, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandnes, M.; Ulvik, R.J.; Vorland, M.; Reikvam, H. Hyperferritinemia-A Clinical Overview. J Clin Med. 2021, 7, 10–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Bian, N.; Wang, J.; Chang, X.; An, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu. J. Serum Ferritin Levels Are Associated with Adipose Tissue Dysfunction-Related Indices in Obese Adults. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2023, 201, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ma, L. Iron metabolism and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Ó.; Ramos, A.S.; Gomes, L.T.S.; Gomes, M.S.; Moreira, A.C. New Perspectives on Circulating Ferritin: Its Role in Health and Disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T. Macrophages and Iron Metabolism. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.A.; Gutierrez, L.; Weiss, A.; Leichtmann-Bardoogo, Y.; Zhang, D. L.; Crooks, D. R.; Sougrat, R.; Morgenstern, A.; Galy, B.; Hentze, M. W.; Lazaro, F. J.; Rouault, T. A.; Meyron-Holtz, E. G. Serum ferritin is derived primarily from macrophages through a nonclassical secretory pathway. Blood. 2010, 116, 1574–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, L.; Corradini, E.; Adams, L.A.; Aigner, E.; Alqahtani, S.; Arrese, M.; et al. Consensus Statement on the definition and classification of metabolic hyperferritinaemia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, T.; Gilardi, F.; Desvergne, B. From chronic overnutrition to metaflammation and insulin resistance: adipose tissue and liver contributions. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 3061–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Domínguez, Á.; Visiedo-Garcí, F. M.; Domínguez-Riscart, J.; González-Domínguez, R.; Mateos, R. M.; Lechuga-Sancho, A. M. Iron Metabolism in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D. E.; Eckel, R. H.; Cohen, R.V.; Wilding, J. P. H.; Bown, W. A.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M. V, Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P. N.; Sarin, S. K.; Anstee, Q. M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. R.; Shah, Y. M. Iron homeostasis in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2013, 3, 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, J. C.; Shatzel, J. J. The hematologic consequences of obesity. Eur J Haematol. 2021, 106, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica. 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, Y.; Kubota, N.; Yamauchi, T.; Kadowaki, T. Role of Insulin Resistance in MAFLD. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jehn, M.; Clark, J. M, Guallar, E. Serum ferritin and risk of the metabolic syndrome in U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27, 2422–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J. S.; Lin, S. M.; Huang, T. C.; Chao, J.C.; Chen, Y. C.; Pan, W. H.; Bai, C. H. Serum ferritin and risk of the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013, 22, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.; Shen, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.; Fang, X.; Duan, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; An, P.; Shao, T.; Chung, R. T.; Zheng, S.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Hepatic transferrin plays a role in systemic iron homeostasis and liver ferroptosis. Blood. 2020, 136, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Q. , Li, Y., Chen, L. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Sig Transduct Target Ther. [CrossRef]

- Mo, M.; Pan. L.; Deng, L.; Liang. M.; Xia, N.; Liang, Y. Iron Overload Induces Hepatic Ferroptosis and Insulin Resistance by Inhibiting the Jak2/stat3/slc7a11 Signaling Pathway. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2024, 82, 2079–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandnes, M.; Ulvik, R.J.; Vorland, M.; Reikvam, H. Hyperferritinemia-A Clinical Overview. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, R.; Yang, S.; Ma, X.; Yu, C. Association between serum ferritin level and the various stages of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. U.; Cho, H. J. Body iron, serum ferritin, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Korean J Hepatol, 2012, 18, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guideline on Use of Ferritin Concentrations to Assess Iron Status in Individuals and Populations; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ABEP. Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet]; Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa: São Paulo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, W. K. S.; et al. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial – 2020. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2021, 116, 516–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrim, H. P.; Parise, E. R.; Figueiredo-Mendes, C.; Galizzi-Filho, J.; Porta, G.; Oliveira, C. P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease Brazilian society of hepatology consensus. Arq Gastroenterol. 2016, 53, 118–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, D. C.; Gomes, C. S.; Almeida Alves, F. T.; Vasconcelos de Oliveira, P. P.; de Freitas, P. C.; Andreazzi, M. O uso de cigarro, narguilé, cigarro eletrônico e outros indicadores do tabaco entre escolares brasileiros: dados da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar 2019. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2022, 25, e220014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C. C.; Chumlea, W. C.; Roche, A. F. Weight. In Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual; Lohman, T. G., Roche, A. F., Martorell, R., Eds.; Human Kinetics Books: Champaign, IL, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 2000, 894, 1–253.

- Callaway, C. W. Anthropometric Measurements. In Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual; Lohman, T. G., Roche, A. F., Martorell, R., Eds.; Human Kinetics Books: Champaign, IL, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Biodynamics Corporation. Manual de Instrução do Monitor de Composição Corporal Biodynamics Modelo 450, Version v.5.1, International; TBW: São Paulo, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman, T. G. Advances in Body Composition Assessment: Current Issues in Exercise Science; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, W. T.; Levy, R. I.; Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, without Use of the Preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Romero, F.; Villalobos-Molina, R.; Jiménez-Flores, J. R.; Simental-Mendía, L. E.; Méndez-Cruz, R.; Murguía-Romero, M.; Rodríguez-Morán, L. Fasting Triglycerides and Glucose Index as a Diagnostic Test for Insulin Resistance in Young Adults. Arch. Med. Res. 2016, 47, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, L. E.; Guerrero-Romero, F. The Correct Formula for the Triglycerides and Glucose Index. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2020, 179, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, A.; Plebani, M.; Peng, M.; Lee, Y. K.; McCafferty, R.; Machin, S. J.; et al. ICSH Recommendations for Modified and Alternate Methods Measuring the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2017, 39, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF). The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome; IDF Communications: Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Précoma, D. B.; Oliveira, G. M. M.; Simão, A. F.; Dutra, O. P.; Coelho, O. R.; Izar, M. C. O.; et al. Updated Cardiovascular Prevention Guideline of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology - 2019. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019, 113, 787–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetteland, P.; Roger, M.; Solberg, H. E.; Iversen, O. H. Population-Based Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rates in 3,910 Subjectively Healthy Norwegian Adults: A Statistical Study Based on Men and Women from the Oslo Area. J. Intern. Med. 1996, 240, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, D.; Nabil, S.; Abdulrazek, A. A.; Abdelnaby, A.; Lotfy, S. The C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio as an Early Diagnostic Marker of Neonatal Sepsis in Preterm Neonates: A Case-Control Study. Pediatr. Sci. J. 2024, 4, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Kim, D.; Kim, H. J.; Lee, C. H.; Yang, J. I.; Kim, W.; et al. Hepatic Steatosis Index: A Simple Screening Tool Reflecting Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2010, 42, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. G.; Lydecker, A.; Murray, K.; Tetri, B. N.; Contos, M. J.; Sanyal, A. J.; et al. Use of the FIB-4 Index for Non-Invasive Evaluation of Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 7–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares (POF 2008-2009): tabela de medidas referidas para os alimentos consumidos no Brasil; Rio de Janeiro, 2011. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv50000.pdf (accessed , 2023). 20 May.

- Pinheiro, A. B. V.; Lacerda, E. M.; Benzecry, E. H.; et al. Tabela para Avaliação Alimentar em Medidas Caseiras, 5th ed.; Atheneu: São Paulo, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos (TBCA); Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Food Research Center (FoRC): São Paulo, 2023. Available online: http://www.fcf.usp.br/tbca (accessed on day month year).

- Monsen, E. R.; Hallberg, L.; Layrisse, M.; Hegsted, M. D.; Cook, J. D.; Mertz, W.; Finch, C. A. Estimation of Available Dietary Iron. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1978, 31(1), 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datz, C.; Müller, E.; Aigner, E. Iron overload and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Minerva Endocrinol. 2016, 42, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Yao, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, H. The relationship of hyperferritinemia to metabolism and chronic complications in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huenur, J. F.; Parodi Cruzat, M.; Aravena González, C.; Eymin Lago, G.; Triantafilo Cerda, N.; Walkowiak Navas, S.; Valenzuela Suárez, A.; Corsi Sotelo, O. Hyperferritinemia in a Chilean Academic Healthcare Network: A Retrospective Study. Rev. Méd. Chile 2023, 151, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun, Y. Association Between Race and Blood Ferritin Level of Whole Blood Donors. Cureus. 2025, 17, e82926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Yao, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, H. The Relationship of Hyperferritinemia to Metabolism and Chronic Complications in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Xu, Z.; Liang, R.; Xie, S. Association Between Dietary Inflammatory Index and Triglyceride Glucose-Body Mass Index with Iron Deficiency in Reproductive Age Women: Evidence from NHANES 2005–2018. Int. J. Women's Health 2025, 17, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, S.; Mensink, G. B.; Beitz, R. Determinants of Diet Quality. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiza, H. A.; Casavale, K. O.; Guenther, P. M.; Davis, C. A. Diet Quality of Americans Differs by Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Income, and Education Level. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, N.; Kirchhoff, M. Relationship Between Serum Ferritin, Alcohol Intake, and Social Status in 2235 Danish Men and Women. Ann. Hematol. 1996, 72, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppe, T.; Doneda, D.; Siebert, M.; Paskulin, L.; Camargo, M.; Tirelli, K. M.; Vairo, F.; Daudt, L.; Schwartz, I. V. The Prognostic Value of the Serum Ferritin in a Southern Brazilian Cohort of Individuals with Gaucher Disease. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016, 39, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. K.; Ryoo, J. H.; Kim, M. G.; Shin, J. Y. Association of Serum Ferritin and the Development of Metabolic Syndrome in Middle-Aged Korean Men: A 5-Year Follow-Up Study. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2521–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias-Vázquez, L.; Arija, V.; Aranda, N.; et al. Factors Associated with Serum Ferritin Levels and Iron Excess: Results from the EPIC-EurGast Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P. J.; Ley, S. H.; Bhupathiraju, S. N.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. D. Associations of Dietary, Lifestyle, and Sociodemographic Factors with Iron Status in Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study in the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Ortegón, M. F.; Ensaldo-Carrasco, E.; Shi, T.; McLachlan, S.; Fernández-Real, J. M.; Wild, S. H. Ferritin, Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Atherosclerosis 2018, 275, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J. Iron Metabolism and Ferroptosis in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Complications: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B. R.; Friedmann Angeli, J. P.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A. I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S. J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S. K.; Kagan, V. E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, H.; Ebata, Y.; Sakabe, T.; Hama, S.; Kogure, K.; Shiota, G. High-Fat, High-Fructose Diet Induces Hepatic Iron Overload via a Hepcidin-Independent Mechanism Prior to the Onset of Liver Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Metabolism 2013, 62, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. C. C.; Huang, Y. F.; Wang, J. D. Hyperferritinemia and Hyperuricemia May Be Associated with Liver Function Abnormality in Obese Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, A. J.; Ford, E. S.; Kennedy, T. P.; Hoidal, J. R. The Association Between Serum Ferritin and Uric Acid in Humans. Free Radic. Res. 2005, 39, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, R.; Pisano, G.; Fargion, S. Role of Serum Uric Acid and Ferritin in the Development and Progression of NAFLD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.; Kim, K. M.; Jin, M. H.; Yoon, J. H. Synergistic Impact of Serum Uric Acid and Ferritin on MAFLD Risk: A Comprehensive Cohort Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, J. F.; Medina, W. L.; Moreto, F.; Burini, R. C. Influência da Adiposidade Sobre o Risco Inflamatório em Pacientes com Glicemia de Jejum Alterada. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 22, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriles, K. E.; Zubair, M.; Azer, S. A. Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) Test. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- He, A.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, L.; Yip, K. C.; Chen, J.; Yan, R.; Li, R. Association Between Serum Iron and Liver Transaminases Based on a Large Adult Women Population. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priego-Parra, B. A.; Triana-Romero, A.; Martínez-Pérez, G. P.; Reyes-Díaz, S. A.; Ordaz-Álvarez, H. R.; Bernal-Reyes, R.; et al. Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI): A Valuable Biomarker in Subjects with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD). Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R. A.; Kowdley, K. V. Serum Ferritin as a Biomarker for NAFLD: Ready for Prime Time? Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armandi, A.; Sanavia, T.; Younes, R.; Caviglia, G. P.; Rosso, C.; Govaere, O.; et al. Serum Ferritin Levels Can Predict Long-Term Outcomes in Individuals with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Gut 2024, 73, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Petta, S.; Manuguerra, R.; Luong, T. V.; Cabibi, D.; Corradini, E.; Craxì, A.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.; Pietrangelo, A. Evaluating the Association of Serum Ferritin and Hepatic Iron with Disease Severity in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, A. Iron and the Liver. Liver Int. 2016, 36, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Rahimi, F.; Boschetti, S.; Devecchi, A.; De Francesco, A.; Mancino, M. V.; Toppino, M.; Morino, M.; Fanni, G.; Ponzo, V.; Bo, S. Pre-operative Micronutrient Deficiencies in Individuals with Severe Obesity Candidates for Bariatric Surgery. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, S.; Hamza, I.; Bartnikas, T. B. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron and Heme Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 42, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskin, E.; Cianciosi, D.; Gulec, S.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Iron Absorption: Factors, Limitations, and Improvement Methods. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20441–20456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, I.; Parker, H. M.; Rangan, A.; Prvan, T.; Cook, R. L.; Donges, C. E.; Steinbeck, K. S.; O’Dwyer, N. J.; Cheng, H. L.; Franklin, J. L.; O’Connor, H. T. Association between Haem and Non-Haem Iron Intake and Serum Ferritin in Healthy Young Women. Nutrients 2018, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teucher, B.; Olivares, M.; Cori, H. Enhancers of Iron Absorption: Ascorbic Acid and Other Organic Acids. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2004, 74, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weschenfelder, C.; Berryman, C. E.; Hennigar, S. R. Dietary Iron Intake and Obesity-Related Diseases. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2025, 25, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Iron and the Intestinal Microbiome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2025, 1480, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenhorst, C. E.; Dawson, B.; Cox, G. R.; Laarakkers, C. M.; Swinkels, D. W.; Peeling, P. Acute Dietary Carbohydrate Manipulation and the Subsequent Inflammatory and Hepcidin Responses to Exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 2521–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, N.; Ishibashi, A.; Iwata, A.; Yatsutani, H.; Badenhorst, C.; Goto, K. Influence of an Energy Deficient and Low Carbohydrate Acute Dietary Manipulation on Iron Regulation in Young Females. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D. S.; Ebbeling, C. B. The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity: Beyond “Calories In, Calories Out.” JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1098–1103. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B. F.; Clegg, D. J. The Sexual Dimorphism of Obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 402, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Manual de Atenção à Mulher no Climatério/Menopausa; Editora do Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Raina, S. K. Limitations of 24-Hour Recall Method: Micronutrient Intake and the Presence of the Metabolic Syndrome. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörwald, K.; Aigner, E.; Bergsten, P.; Brunner, S. M.; Forslund, A.; Kullberg, J.; Ahlström, H.; Manell, H.; Roomp, K.; Schütz, S.; Zsoldos, F.; Renner, W.; Furthner, D.; Maruszczak, K.; Zandanell, S.; Weghuber, D.; Mangge, H. Serum Ferritin Correlates With Liver Fat in Male Adolescents With Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020, 18, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguree, S.; Reddy, M. B. Inflammatory Markers and Hepcidin are Elevated but Serum Iron is Lower in Obese Women of Reproductive Age. Nutrients 2021, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serum Biochemistry | Classification | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SF | Normal (15 a 150 ng/mL for female and 15 a 200 ng/mL for male) Hight SF (>150 ng/mL for female and >200 ng/mL for male). |

WHO [30]. |

| Glucose | Normal (<100 mg/dL); High (>100 mg/dL), for both sexes. |

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [45]. |

| TG | Normal (<150 mg/dL); High (>150 mg/dL), for both sexes. |

IDF [45]. |

| TC | Normal (<190 mg/dL); High (>190 mg/dL), for both sexes. |

Précoma et al. [46]. |

| HDL | Normal (female>50 mg/dL and male>40 mg/dL); Decreased (<50 mg/dL female and <40 mg/dL male). |

IDF [45]. |

| LDL | Normal (<130 mg/dL); High (>130 mg/dL), for both sexes. |

Précoma et al. [46]. |

| TyG | >4.55 to female and >4.68 to male were indicative of IR. | Guerrero-Romero et al. [42]. |

| ESR | Normal (female < 20 mm and High >20 mm); Normal (male < 10 mm and High >10 mm). |

Wetteland et al. [47]. |

| CRP | < 5mg/dL (Negative); >5 mg/dL (Positive). |

Khedr et al. [48]. |

| UA | Decreased (<1.5 mg/dL); Normal (1.5 to 6 mg/dL); High (>6 mg/dL), for both sexes. |

Laboratory |

| Hypertension | No (SBP: <130 mmHg and DBP <85 mmHg; Yes (SBP: > 130 mmHg and DBP > 85 mmHg) or in hypertension treatment, for both sexes. |

IDF [45]. |

| AST and ALT | Decreased (<10U/L); Normal (10 a 37 U/L); High (>37 U/L), for both sexes. |

Laboratory. |

| HSI | Yes (>36) No (<36) |

Lee et al. [49]. |

| FIB-4 | No risk of fibrosis (escore <1.3); Risk of fibrosis (>1.3), for both sexes. |

Shah et al. [50]. |

| Variable | Category | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 67 (89.3%)# | 20 (52.6%) | < 0.0001a |

| Male | 8 (10.7%) | 18 (47.4%)# | ||

| Age | - | 31 (23–41.5) | 41 (31.2–49.8) | 0.315c |

| Marital Status | Single | 40 (53.3%)# | 8 (21.1%) | 0.012b |

| Married/Stable Union | 28 (37.4%) | 25 (65.7%)# | ||

| Divorced | 4 (5.3%) | 3 (7.9%) | ||

| Widower | 3 (4%) | 2 (5.3%) | ||

| Education | Incomplete Elementay Education | 6 (8%) | 6 (15.8%) | 0.009b |

| Complete Elementay Education | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Incomplete High School | 2 (2.7%) | 1 (2.6%) | ||

| Complete High School | 15 (20%) | 16 (42.1%)# | ||

| Incomplete Higher Education | 27 (36%)# | 2 (5.3%) | ||

| Complete Higher Education | 19 (25.3%) | 11 (28.9%) | ||

| Posgraduate | 5 (6.7%) | 2 (5.3%) | ||

| Family Income Class | AB | 14 (26.3%) | 10 (18.9%) | 0.387a |

| C | 43 (60.5%) | 23 (58.1%) | ||

| DE | 17 (13.2%) | 5 (23%) | ||

| Smoker | No | 69 (92%) | 35 (92.1%) | 0.984a |

| Yes | 6 (8%) | 3 (7.9%) | ||

| Alcohol Consuption | No | 41 (54.7%) | 20 (52.6%) | 0.838a |

| Yes | 34 (45.3%) | 18 (47.4%) | ||

| Classification of Alcohol Consuption | Not Excessive | 68 (90.7%) | 37 (97.4%) | 0.189a |

| Excessive | 7 (9.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | ||

| Physical Activity | No | 27 (36%) | 16 (42.1%) | 0.528a |

| Yes | 48 (64%) | 22 (57.9%) | ||

| Minutes per week | - | 150 (0–300) | 120 (0–281.2) | 0.661c |

| Active | No | 36 (48%) | 22 (57.9%) | 0.320a |

| Yes | 39 (52%) | 16 (42.1%) |

| Variable | Category | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | Underweight | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.003b |

| Normal-weight | 31 (41.3%)# | 5 (13.2%) | ||

| Overweight | 20 (26.7%) | 12 (31.6%) | ||

| Obesity | 21 (28%) | 21 (55.3%)# | ||

| WC | No Risk | 37 (49.3%)# | 8 (21.1%) | 0.004a |

| With Risk | 38 (50.7%) | 30 (78.9%)# | ||

| WHR | No Risk | 57 (77%) | 28 (73.7%) | 0.874a |

| With Risk | 17 (23%) | 10 (26.3%) | ||

| BF% | Acceptable | 40 (54.8%)# | 9 (24.3%) | 0.002a |

| High | 33 (45.2%) | 28 (75.7%)# | ||

| LM% | - | 70±8.1 | 68,4±6.8 | 0.301c |

| Variable | Category | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Normal | 67 (91.8%)# | 29 (76.3%) | 0.023a |

| High | 6 (8.2%) | 9 (23.7%)# | ||

| TG |

Normal | 65 (86.7%)# | 24 (63.2%) | 0.003a |

| High | 10 (13.3%) | 14 (36.8%)# | ||

| TC | Normal | 54 (70.1%) | 21 (58.3%) | 0.216a |

| High | 23 (29.9%) | 15 (41.7%) | ||

| HDL |

Normal | 13 (17.3%) | 9 (23.7%) | 0.420a |

| Decreased | 62 (82.7%) | 29 (76.3%) | ||

| LDL |

Normal | 58 (77.3%) | 28 (73.7%) | 0.667a |

| High | 17 (22.7%) | 10 (26.3%) | ||

| IR |

No | 52 (71.2%)# | 19 (50%) | 0.027a |

| Yes | 21 (28.8%) | 19 (50%)# | ||

| CRP | Negative | 40 (66.7%) | 24 (68.6%) | 0.849a |

| Positive | 20 (33.3%) | 11 (31.4%) | ||

| ESR | Normal | 31 (53.4%) | 20 (57.1%) | 0.729a |

| High | 27 (46.6%) | 15 (42.9%) | ||

| Hypertension | Yes | 16 (21.3%) | 19 (50%)# | 0.001a |

| No | 59 (78.7%)# | 19 (50%) | ||

| MS | No | 59 (78.7%)# | 18 (47.4%) | 0.001a |

| Yes | 16 (21.3%) | 20 (52.6%)# |

| Variable | Category | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA | Decreased | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.016b |

| Normal | 60 (88.2%)# | 27 (71%) | ||

| High | 7 (10.3%) | 11 (29%)# | ||

| AST |

Normal | 58 (82.8%) | 27 (73%) | 0.228a |

| High | 12 (17.2%) | 10 (27%) | ||

| ALT | Decreased | 1 (1,4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.008b |

| Normal | 66 (94.3%)# | 29 (78.4%) | ||

| High | 3 (4.3%) | 8 (21.6%)# | ||

| FIB4 | No Risk fibrosis | 56 (83,6%) | 30 (83.3%) | 0.974a |

| With Risk fibrosis | 11 (16,4%) | 6 (16,7%) | ||

| HSI >36 | No | 39 (55.7%)# | 12 (32.4%) | 0,022a |

| Yes | 31 (44.3%) | 25 (67.6%)# |

| Variable | SF Normal | SF High | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 1692 (1315–1995) | 1718 (1076.2–2411.2) | 0.412a |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 189.5 (146.7–278.5) | 212.2 (129.9–287.1) | 0.024a |

| Protein (g) | 68.6 (52.3–97.2) | 79.5 (60.7–107) | 0.788a |

| Lipids (g) | 55.7 (40–74.8) | 64.3 (36–88.1) | 0.164a |

| SFA (g) | 17.8 (11.8–25) | 18.2 (12.6–28) | 0.315a |

| MUFA (g) | 15.6 (11.2–22.9) | 18.4 (11.4–24.7) | 0.412a |

| PUFA (g) | 12.3 (9.2–17.6) | 12.9 (9.3–18.4) | 0.927a |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 261.9 (167.8–426.9) | 270.1 (178.3–477.3) | 0.527a |

| Fibers (g) | 18.3 (10.9–25.4) | 22.7 (15.8–30.4) | 0.073a |

| Per capita oil (ml) | 10 (6.6–15) | 10 (6.1–15) | 0.97a |

| Per capita lard (g) | 5.5 (2.6–14.7) | 5.6 (4.2–8.3) | 0.558a |

| Total vitamin C (mg) | 49.2 (20.4–119) | 57,1 (25.5–137.3) | 0.648a |

| Total meet (g) | 120 (60–217.5) | 150 (100.5–200) | 0.927a |

| Total iron (mg) | 10,9 (7.5–14.4) | 10.1 (6.5–13.1) | 0.164a |

| Total heme iron (mg) | 0,9 (0.3–1.8) | 0.8 (0.3–1.9) | 0.788a |

| Total non-heme iron (mg) | 9.3 (6.8–12.5) | 9.2 (5.6–12.6) | 0.164a |

| Total iron absorbed (mg) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.315a |

| Source | value | Pr > Qui² | OR [IC 95 %] * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -2.46 | < 0.0001 | |

| Sex-Female | 0.00 | ||

| Sex-Male | 2.82 | < 0.0001 | 16.82 [4.48-63.1] |

| BF% - Acceptable | 0.00 | ||

| BF% - Elevated | 2.02 | 0.004 | 7.5 [1.94-29.03] |

| HSI <36 – No | 0.00 | ||

| HSI >36 – Yes | -0.43 | 0.47 | 0.65 [0.20-2.11] |

| MS-No | 0.00 | ||

| MS-Yes | 0.55 | 0.29 | 1.74 [0.62-4.84] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).