Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

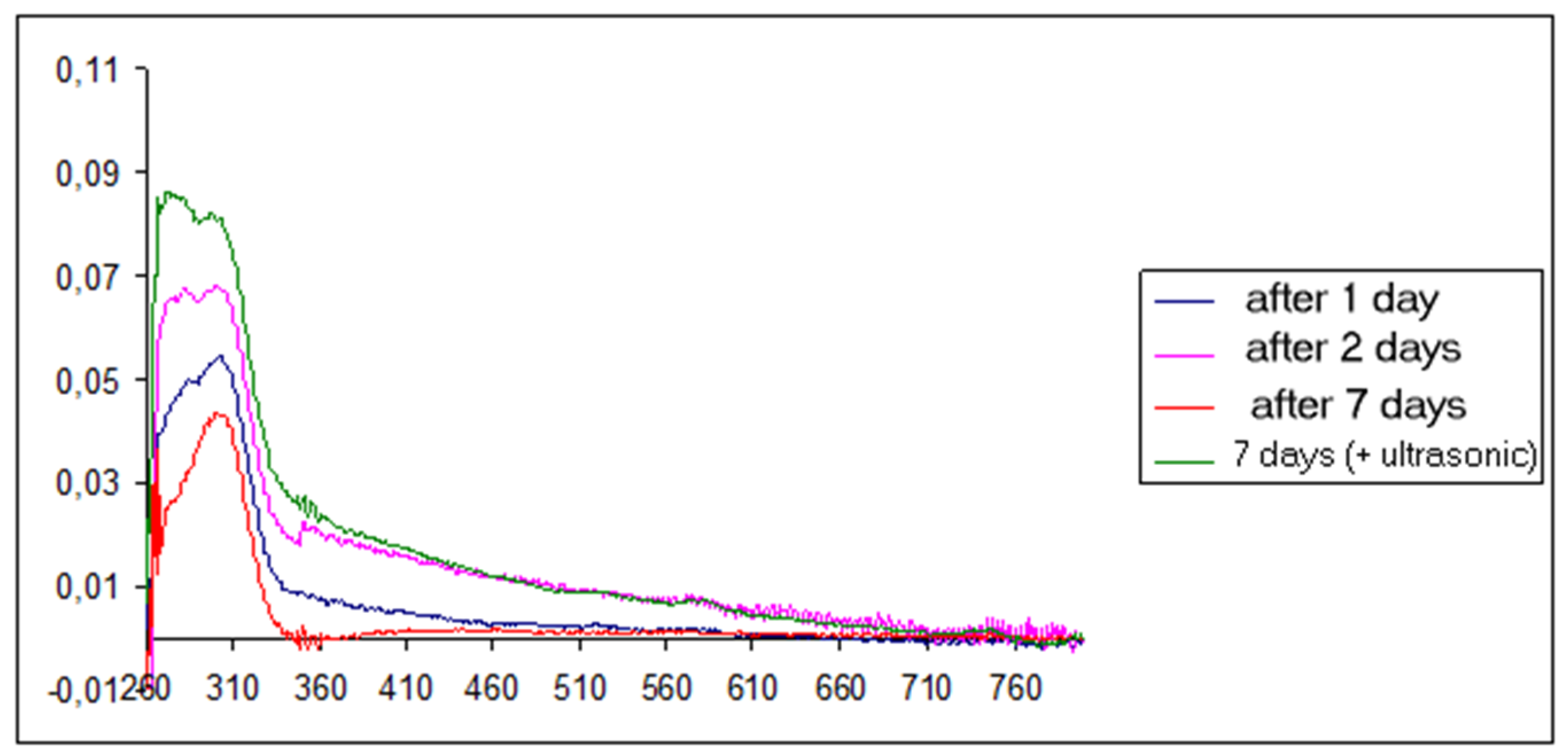

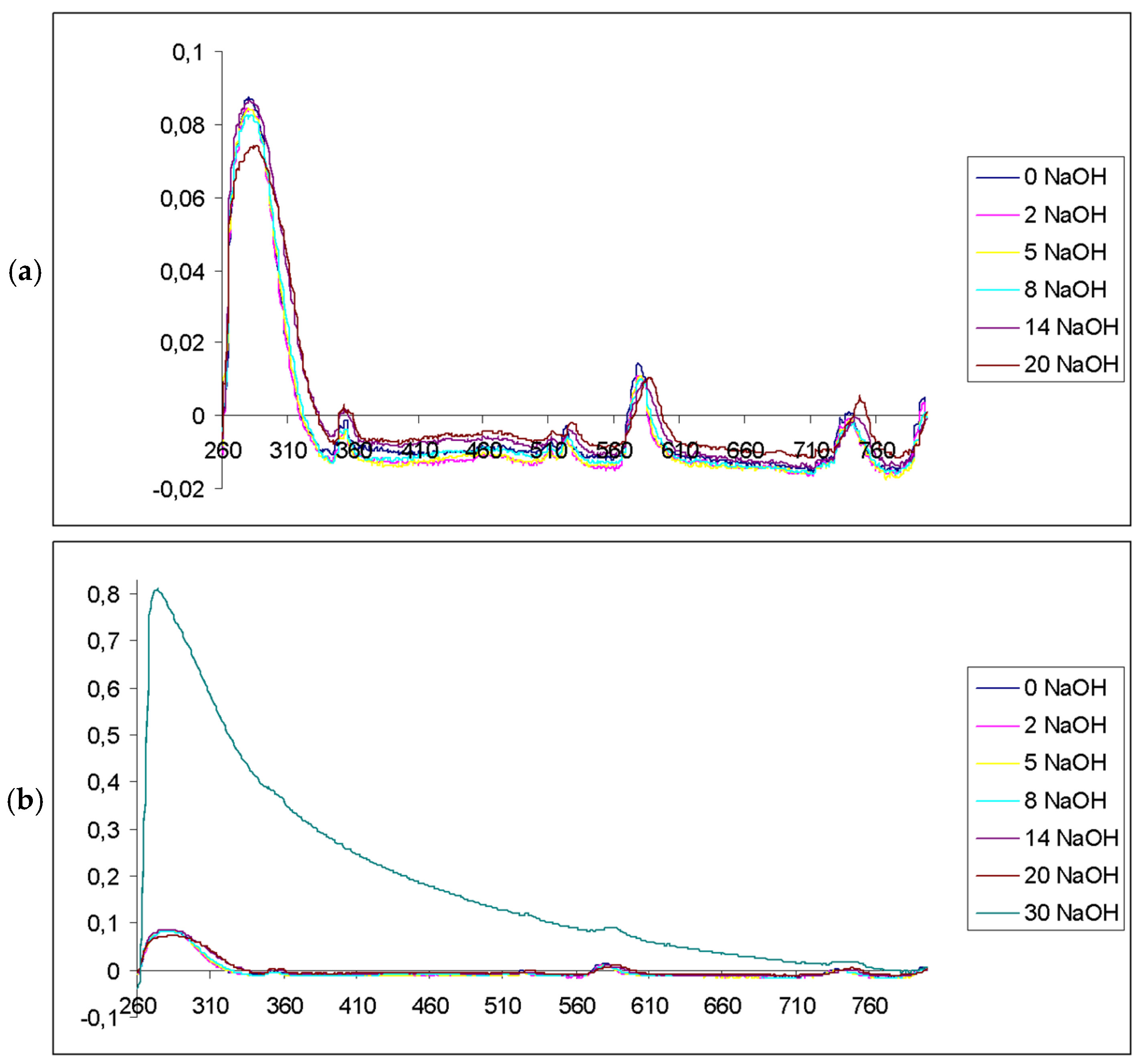

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Nd2O3 | Neodymium oxide |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| TOPO | Trioctylphosphine oxide |

| QDs | Quantum dots |

| LEDs | Light-emitting diodes |

| SNO | Sudbury Neutrino Observatory |

| PSS | Polystyrene sulfonate |

| PAH | Polyallylamine hydrochloride |

| pDA | Polydopamine |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| LBL | Layer-by-layer |

| SERS | Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| XRD | X-ray powder diffraction |

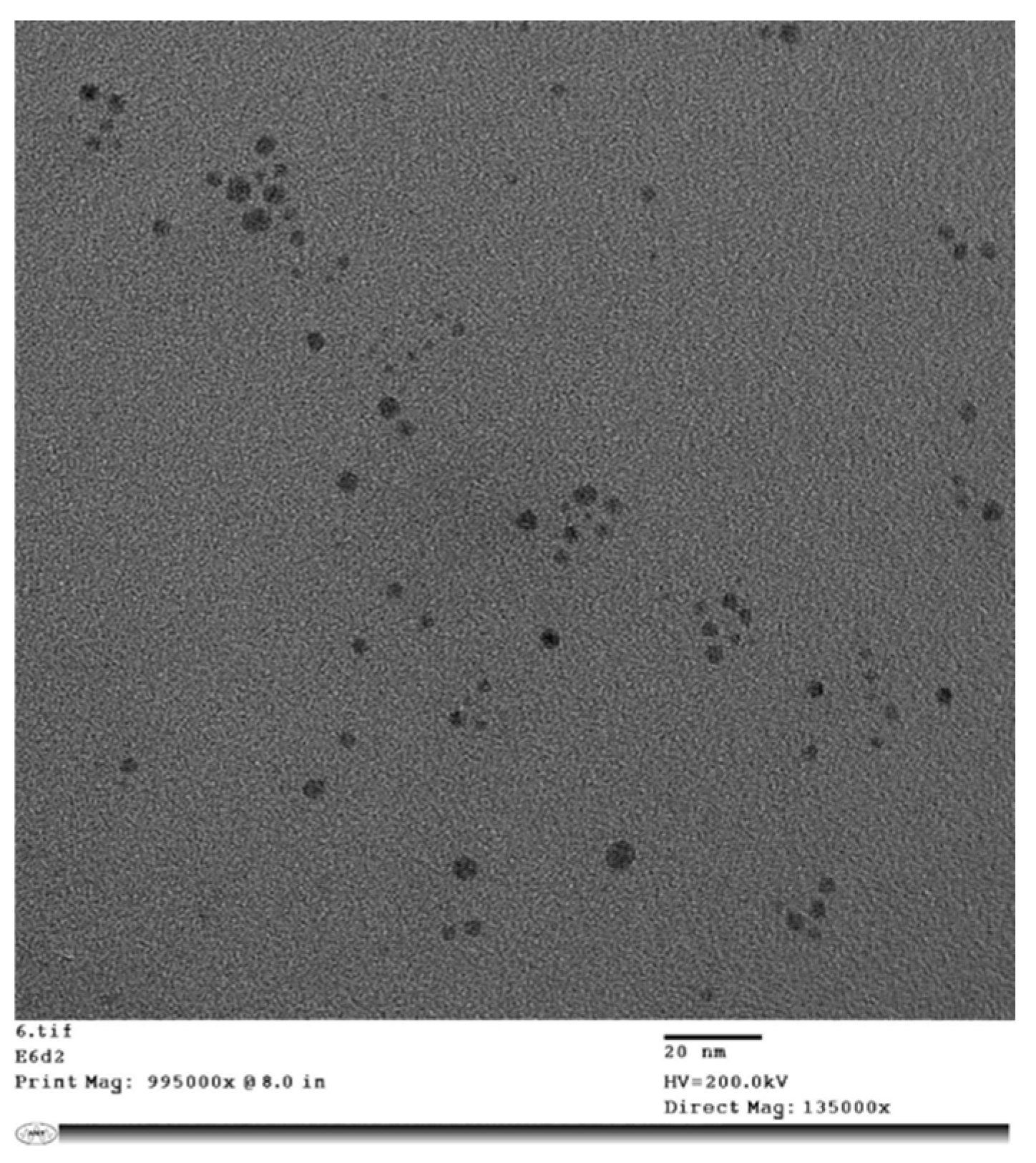

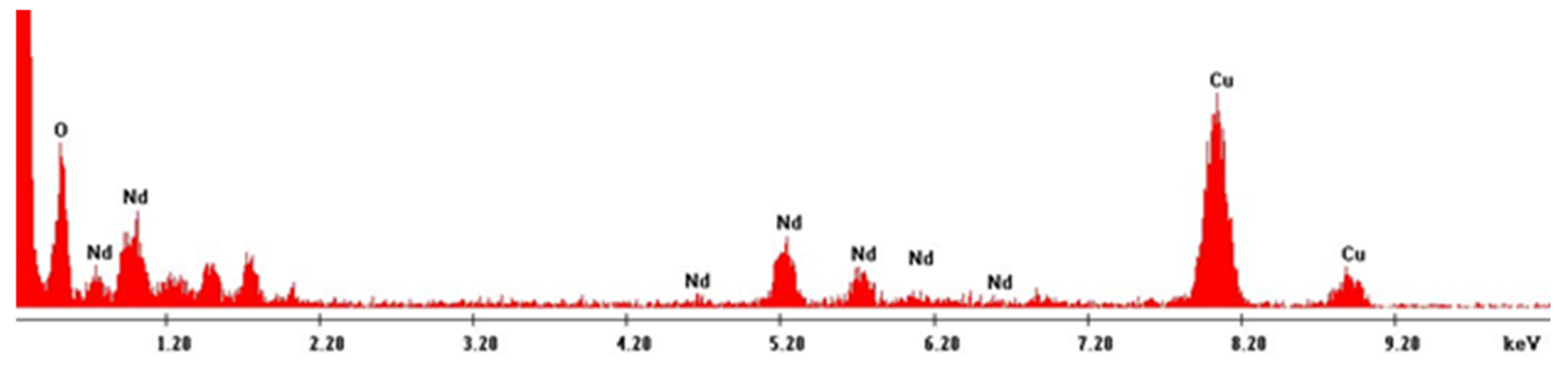

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| EDX | X-ray energy dispersive analysis |

| ICP | Inductively coupled plasma |

| IR | Infrared |

References

- Saleem, M.I.; Yang, S.; Sulaman, M.; Hu, J.; Chandrasekar, P.V.; Shi, Y.; Zhi, R.; Batool, A.; Zou, B. All-Solution-Processed UV-IR Broadband Trilayer Photodetectors with CsPbBr3 Colloidal Nanocrystals as Carriers-Extracting Layer. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 165502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevim Ünlütürk, S.; Taşcıoğlu, D.; Özçelik, S. Colloidal Quantum Dots as Solution-Based Nanomaterials for Infrared Technologies. Nanotechnology 2025, 36, 082001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Guan, X.; Hu, L.; Kim, J.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, H.; Wu, T. Inorganic Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Versatile Nanomaterial Platform for Electronic Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, J.; Lamba, R.; Yukta, Y.; Yadav, R.; Kumar, R.; Pani, B.; Singh, B. Advancements in Semiconductor Quantum Dots: Expanding Frontiers in Optoelectronics, Analytical Sensing, Biomedicine, and Catalysis. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 10330–10389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phafat, B.; Bhattacharya, S. Quantum Dots as Theranostic Agents: Recent Advancements, SurfaceModifications, and Future Applications. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gour, A.; Ramteke, S.; Jain, N.K. Pharmaceutical Applications of Quantum Dots. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, F.; Shi, L.; Zhao, S.; Wan, M.; Zhang, X. Carbon Quantum Dots: Properties, Preparation, and Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Raina, D.; Rishipathak, D.; Babu, K.R.; Khurana, R.; Gupta, Y.; Garg, K.; Rehan, F.; Gupta, S.M. Quantum Dots in the Biomedical World: A Smart Advanced Nanocarrier for Multiple Venues Application. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 2022, 355, 2200299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Nie, J.; Guo, Y.; Ouyang, X. Lead Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots Based Liquid Scintillator for X-Ray Detection. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 205201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efros, A.L.; Brus, L.E. Nanocrystal Quantum Dots: From Discovery to Modern Development. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 6192–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delage, M.-È.; Lecavalier, M.-È.; Larivière, D.; Allen, C.N.; Beaulieu, L. Preliminary Investigation of a Luminescent Colloidal Quantum Dots-Based Liquid Scintillator. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 847, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle Catherine L, Scates Dawn M, Fronk Ryan G, Demmer Rick L, Ghosh Priyarshini Scintillation Compositions And Related Hydrogels For Neutron And Gamma Radiation Detection, And Related Detection Systems And Methods 2025.

- Shimizu, I.; Chen, M. Double Beta Decay Experiments With Loaded Liquid Scintillator. Front. Phys. 2019, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C. The SNO+ Experiment JINST 2021, 16, P08059.

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2015. NobelPrize.org 2025.

- Dorris, A.; Sicard, C.; Chen, M.C.; McDonald, A.B.; Barrett, C.J. Stabilization of Neodymium Oxide Nanoparticles via Soft Adsorption of Charged Polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 3357–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Z.; Lin, J. Surface-Functionalized NdVO4:Gd3+ Nanoplates as Active Agents for Near-Infrared-Light-Triggered and Multimodal-Imaging-Guided Photothermal Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.O.; Alcaraz, P.; Witte, R.S. Nanodroplet With Layer-By-Layer Assembly. US Patent App. 17/778,733, 2022.

- Singh, H.; Hatton, T.A. Permanently Linked, Rigid, Magnetic Chains. US Patent 7,332,101, 2008.

- Singh, H; Hatton, T.A. Permanently Linked Magnetic Chains. US Patent 8,827,612, 2006.

- Su, X.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Han, T.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, N.; Kang, M.; Fu, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, D.; et al. Aggregation-Induced Emission-Active Poly(Phenyleneethynylene)s for Fluorescence and Raman Dual-Modal Imaging and Drug-Resistant Bacteria Killing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivapalan, S.T.; DeVetter, B.M.; Yang, T.K.; Schulmerich, M.V.; Bhargava, R.; Murphy, C.J. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy of Polyelectrolyte-Wrapped Gold Nanoparticles in Colloidal Suspension. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 10677–10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.; Fries, T.; Gahn, A.; Kummer, F.; Herr, U.; Tidecks, R.; Samwer, K. Chemical Vapor Synthesis and Luminescence Properties of Nanocrystalline Cubic Y2O3:Eu. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 86, 3129–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomellini, M.; Gozzi, D.; Latini, A. Nanodusting of RENi5 Intermetallic Grains through Nucleation and Growth of Carbon Nanotubes (RE ⋮ Rare-Earth). J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 3266–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, G.; Amans, D.; Dujardin, C.; Masenelli-Varlot, K. Facile and Rapid Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Nanoparticles via Pulsed Laser Ablation in Liquid. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 445605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilers, H.; Tissue, B.M. Laser Spectroscopy of Nanocrystalline Eu2O3 and Eu3+:Y2O3. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 251, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Studenikin, S.A.; Cocivera, M. Blue, Green and Red Cathodoluminescence of Y2O3 Phosphor Films Prepared by Spray Pyrolysis. J. Lumin. 2001, 93, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.C.; Roh, H.S.; Park, S.B. Preparation of Y2O3:Eu Phosphor Particles of Filled Morphology at High Precursor Concentrations by Spray Pyrolysis. Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.C.; Roh, H.S.; Park, S.B.; Park, H.D. [No Title Found]. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2002, 21, 1027–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosev, D.; Guo, B.; Kennedy, I.M. Photoluminescence of as an Indication of Crystal Structure and Particle Size in Nanoparticles Synthesized by Flame Spray Pyrolysis. J. Aerosol Sci. 2006, 37, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Dong, N.; Yin, M.; Zhang, W.; Lou, L.; Xia, S. Visible Upconversion in Rare Earth Ion-Doped Gd2O3 Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 19205–19209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ju, X.; Wu, Z.Y.; Liu, T.; Hu, T.D.; Xie, Y.N.; Zhang, Z.L. Structural Characteristics of Cerium Oxide Nanocrystals Prepared by the Microemulsion Method. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 4192–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaaoudi, H.; Fang, Z.; Barralet, J.E.; Wright, A.J.; Butler, I.S.; Kozinski, J.A. Synthesis, Characterization and Properties of Erbium-Based Nanofibres and Nanorods. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 445606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaaoudi, H.; Fang, Z.; Butler, I.S.; Kozinski, J.A. Synthesis of Erbium Hydroxide Microflowers and Nanostructures in Subcritical Water. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 185606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield, G.; Keron, H.A.; Dobson, P.J.; Hutchison, J.L. Synthesis and Properties of Sub-50-Nm Europium Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999, 215, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakefield, G.; Keron, H.A.; Dobson, P.J.; Hutchison, J.L. Structural and Optical Properties of Terbium Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1999, 60, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, Y. Particle Processing Technology. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2014, 15, 010201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasp, J.; Eichholz, R.; Glass For Radiation And/or Particle Detectors US Patent App. 18/475,925, 2024.

- Fischer, D.K.; Rodrigues De Fraga, K.; Scheeren, C.W. Ionic Liquid/TiO2 Nanoparticles Doped with Non-Expensive Metals: New Active Catalyst for Phenol Photodegradation. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 2473–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghmandfard, A.; Madaah Hosseini, H.R. A Facile, Two-Step Synthesis and Characterization of Fe3O4–LCysteine–Graphene Quantum Dots as a Multifunctional Nanocomposite. Appl. Nanosci. 2021, 11, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidhu, A.K.; Verma, N.; Kaushal, P. Role of Biogenic Capping Agents in the Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Therapeutic Potential. Front. Nanotechnol. 2022, 3, 801620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, R.; Zia, M.; Naz, S.; Aisida, S.O.; Ain, N.U.; Ao, Q. Role of Capping Agents in the Application of Nanoparticles in Biomedicine and Environmental Remediation: Recent Trends and Future Prospects. J. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, U.; Fojtik, A.; Weller, H.; Henglein, A. Photochemistry of Semiconductor Colloids. Preparation of Extremely Small ZnO Particles, Fluorescence Phenomena and Size Quantization Effects. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1985, 122, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Fendler, J.H. Langmuir−Blodgett Film Formation from Fluorescence-Activated, Surfactant-Capped, Size-Selected CdS Nanoparticles Spread on Water Surfaces. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrebtov, A.I.; Danilov, V.V.; Kulagina, A.S.; Reznik, R.R.; Skurlov, I.D.; Litvin, A.P.; Safin, F.M.; Gridchin, V.O.; Shevchuk, D.S.; Shmakov, S.V.; et al. Influence of TOPO and TOPO-CdSe/ZnS Quantum Dots on Luminescence Photodynamics of InP/InAsP/InPHeterostructure Nanowires. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.B.; Norris, D.J.; Bawendi, M.G. Synthesis and Characterization of Nearly Monodisperse CdE (E = Sulfur, Selenium, Tellurium) Semiconductor Nanocrystallites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8706–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. Preparation and Characterization of ZrO2 Nanoparticles Capped by Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO). J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater Sci Ed 2011, 26, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, W.; Fang, B.; Zhang, S.; Lu, X.; Ding, J. Optimization Hydrothermal Synthesis Conditions for Nano-sized (Na0.5 Bi0.495 Nd0.005 )TiO3 Particles by an Orthogonal Experiment and Their Luminescence Performance. Luminescence 2021, 36, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, M.; Sapkota, K.P.; Shrestha, S. Effect of pH, Amount of Metal Precursor, and Reduction Time on The Optical Properties and Size of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Aqueous Extract of Rhizomes of Acorus Calamus. J. Nepal Chem. Soc. 2024, 44, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, M.F.; Fen, Y.W.; Zaid, M.H.M.; Omar, N.A.S.; Khaidir, R.E.M. Sintering Temperature Effect on Structural and Optical Properties of Heat Treated Coconut Husk Ash Derived SiO2 Mixed with ZnO Nanoparticles. Materials 2020, 13, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayarambabu, N.; Velupla, S.; Akshaykranth, A.; Anitha, N.; Rao, T.V. Bambusa Arundinacea Leaves Extract-Derived Ag NPs: Evaluation of the Photocatalytic, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Anticancer Activities. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, R.; Mamun, M.S.A.; Islam, S.; Khatun, N.; Hakim, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Dhar, P.K.; Barai, H.R. Phytochemical-Assisted Synthesis of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Catalytic Activity. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, L.; Sun, C.; Dou, J.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, L. Tunable Transparency and NIR-Shielding Properties of Nanocrystalline Sodium Tungsten Bronzes. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasp, J.; Eichholz, R. Glass For Radiation And/Or Particle Detectors. US Patent App. 18/475,925, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).