1. Introduction

The production of data in bioarchaeology continues to expand due to advances in scientific analysis, including ancient DNA sequencing, palaeopathology, isotopic profiling, and osteological assessment. However, this rapid increase in data volume is paralleled by the finite and often destructive nature of the samples from which it is derived. This paradox underscores the urgent need for data to be reused and repurposed, aligning with the principles of FAIR data management—making datasets Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable.

Despite this imperative, much of the valuable information in bioarchaeology remains embedded within grey literature, particularly in PDF-format reports published by commercial and academic archaeological units. While PDFs provide a stable and widely compatible medium for dissemination, they are ill-suited to structured data extraction and machine-readable processing. The result is that valuable datasets remain locked in static documents, limiting their utility for research and public engagement.

This paper investigates the feasibility of using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Named Entity Recognition (NER) techniques to address these challenges. Specifically, it introduces the Osteoarchaeological and Palaeopathological Entity Search (OPES), a prototype system designed to extract domain-specific terms from grey literature PDFs archived by the Archaeology Data Service (ADS). In contrast to recent work that utilises high-powered transformer models or large language models (LLMs), OPES is built using lightweight, interpretable methods. This approach reflects a conscious decision to balance computational performance with ethical and environmental considerations, particularly in digital heritage research, where transparency and sustainability are often prioritised over raw technical power.

This paper also introduces and applies a comprehensive evaluation framework to assess OPES across five key success criteria. Drawing on feedback from domain experts, students, and public members, the evaluation provides nuanced insight into the effectiveness and limitations of this approach. In doing so, the paper contributes a practical tool for osteoarchaeological data access and outlines a replicable model for the ethical development and assessment of NLP systems in the heritage sector.

1.1. Bioarchaeology and Data Complexity

Bioarchaeology brings together a range of analytical specialisms, including osteology, palaeopathology, ancient DNA (aDNA), stable isotope analysis, and proteomics. Each sub-discipline contributes diverse data types, such as skeletal pathologies, isotopic ratios, and genomic sequences. These datasets are often particular and temporally or spatially contextualised. With continued advancement in molecular and imaging techniques, the volume of bioarchaeological data is expanding exponentially [

1,

2].

This data growth presents both opportunity and risk. On one hand, the data has increasing potential to contribute to broader archaeological and anthropological narratives. On the other, the destructive nature of bioarchaeological sampling and the finite availability of remains means the datasets generated must be as reusable and accessible as possible. Applying FAIR data principles offers one pathway towards addressing this tension by encouraging open, structured, and sustainable data practices.

1.2. Assessing FAIRness in Bioarchaeology

The FAIR principles advocate for data to be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [

3]. Achieving FAIRness requires consideration of several elements, including file formats, persistent identifiers, ontologies, and controlled vocabularies, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

A Needs Analysis was conducted to assess FAIR’s current bioarchaeological data practices [

4]. This study revealed that bioarchaeological data management is often inconsistent and lacks standardisation (see

Figure 2). Data is processed and deposited in varied formats, stored in different locations, and governed by differing levels of access and copyright. Adopting FAIR-supporting elements such as ORCiDs, structured metadata, and systematic documentation is uneven across sub-disciplines.

The study identified palaeopathology, zooarchaeology, and osteoarchaeology areas needing improved data reusability strategies. Given the predominance of PDF-based written reports in these fields, applying NLP and NER offers a valuable means of enhancing data discoverability and reuse. Prior work on zooarchaeological datasets has already demonstrated the potential of these technologies [

5].

1.3. Natural Language Processing and the Role of NER

Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Named Entity Recognition (NER) have increasingly been adopted in archaeology and heritage informatics to address unstructured data challenges. Early initiatives such as Archaeotools [

6], STAR [

7], and STELLAR [

8] illustrated the potential of semantic search and ontology mapping. Later projects like SENESCHAL and ARIADNE incorporated linked open data, controlled vocabularies, and rule-based text mining to enable more structured data interactions. More recent work has demonstrated the application of BERT-based models for archaeological text retrieval [

24] and explored domain-specific NER approaches for historical documents [

25,

26].

Developing a Zooarchaeological Entity Search [

5] demonstrated the viability of domain-specific NER systems in archaeology. This earlier work informed the development of OPES, adopting similar approaches to the osteoarchaeological and palaeopathological domains.

Recent work has shown promising results with BERT-based models for archaeological text retrieval, with Brandsen et al. [

24] reporting F1-scores of 0.91 for location entities and 0.87 for artifact entities in Dutch archaeological reports. However, their approach required substantial computational resources and showed limitations in handling domain-specific terminology. Similarly, historical document NER systems [

25,

26] have achieved high performance (F1-scores >0.90) but typically focus on well-defined entity types like person names and dates, rather than the complex bioarchaeological terminology addressed by OPES.

Comparative analysis reveals that while OPES achieves lower raw performance metrics (F1=0.818) than transformer-based systems, it offers several advantages: (1) interpretable decision-making processes allowing domain expert refinement, (2) minimal computational requirements enabling deployment in resource-constrained environments, and (3) faster inference times suitable for real-time search applications. The trade-off between accuracy and sustainability represents a conscious design choice aligned with responsible AI principles [

23].

In the current landscape, more powerful transformer-based LLMs such as BERT [

9], BioBERT [

10], SciBERT [

11], and GPT-4 [

12] have significantly advanced information extraction capabilities. These models have enabled improvements in zero-shot classification, contextual entity linking, and semantic search within large unstructured corpora [

13]. However, despite these technical advancements, they raise serious ethical, environmental, and epistemological concerns. High computational costs [

14], the opacity of model outputs [

15], and the risk of perpetuating biases [

16] make their uncritical deployment problematic, particularly in domains like heritage and archaeology that demand transparency, sustainability, and domain-sensitive accuracy.

Recent scholarship in digital humanities and archaeological informatics echoes this caution, advocating for more environmentally aware and ethically informed applications of AI [

17,

18]. Tools like OPES prioritising interpretability and methodological rigour, even at the cost of raw performance, align with these emerging priorities. By drawing on transparent, efficient methods and grounding its design in human-centred evaluation, OPES offers a scalable and responsible approach to improving access to grey literature. At the same time, it creates a foundation for future integration with LLM-powered enhancements while maintaining methodological accountability.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodological approach taken in designing, developing, and evaluating the OPES tool. Unlike current approaches that rely on transformer-based architectures or large-scale language models, OPES was developed using lightweight, modular NLP and NER systems. The decision to adopt these methods was shaped by practical and ethical considerations, particularly the need for computational efficiency, transparency, and replicability in resource-limited heritage research contexts.

2.1. Document Selection

A representative corpus was selected from the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) archive to train and evaluate the OPES prototype. Reports from the Crossrail excavations were chosen due to their richness in osteological content and consistent formatting. These documents were pre-screened for relevant terminology associated with human remains, such as anatomical references (e.g. “humerus,” “molar”) and disease indicators (e.g. “rickets”). Five reports were selected to serve as the Gold Standard dataset.

2.2. Annotation Process

The annotation process took place in three phases:

Initial Annotation: Using a word processor, the researcher manually annotated the selected documents. Each osteoarchaeological or palaeopathological term referring to the human body was tagged with a unique identifier derived from the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). MeSH was selected for its extensive vocabulary coverage, though limitations include inconsistencies with British English terminology and a lack of archaeological disease classifications.

Expert Annotation: A domain expert independently reviewed and re-annotated the same five documents to verify accuracy. Different colours were used to distinguish term types, with a consistent colour key maintained to ensure comparability. A “super-annotator” subsequently reviewed both annotation sets, resolving all discrepancies—44 in total—to create a consistent, verified dataset. Overall, 2,582 annotations covering 252 distinct terms were made, although 28 terms were only observed once, limiting their training utility. These low-frequency terms were excluded from the final model training.

Structured Annotation in GATE: The final, reconciled annotations were transferred into XML format and imported into the GATE Developer environment. Using MeSH identifiers, these annotations were applied to the documents within GATE to produce the final Gold Standard training set used in model development.

This hybrid manual-expert-supervised approach ensured domain accuracy and data consistency, offering a high-quality foundation for model training.

2.3. Model Training and Rationale

Rather than using high-resource models such as BERT or GPT-style transformers, OPES was trained using a custom NER model developed in Keras with Theano as the backend. Performance metrics on the test set showed:

Precision: 0.913;

Recall: 0.868;

F1-Score: 0.889;

While these frameworks are considered legacy in the context of modern AI, they were selected due to their low computational overhead, flexibility in fine-tuning, and reproducibility without reliance on cloud infrastructure. These factors made them especially suitable for deployment in heritage contexts where access to powerful hardware or proprietary APIs may be limited. Moreover, avoiding LLMs aligns with emerging critiques regarding AI sustainability and opacity [

14,

16].

2.4. Evaluation Framework

The effectiveness of the OPES tool and the underlying NLP and NER algorithms was evaluated through a user survey. Following the approach outlined by Albert and Tullis [

19], participants—including osteoarchaeological experts, archaeology students, and members of the general public—were asked to rate the system using a 7-point Likert scale.

In this scale:

The tool was considered to partially meet its success criteria if the mean and modal scores exceeded 3.5 (the midpoint) and to fully meet the criteria if scores exceeded 5.25 (three-quarters of the scale). Scores below 3.5 indicated a failure to meet expectations.

3. Results

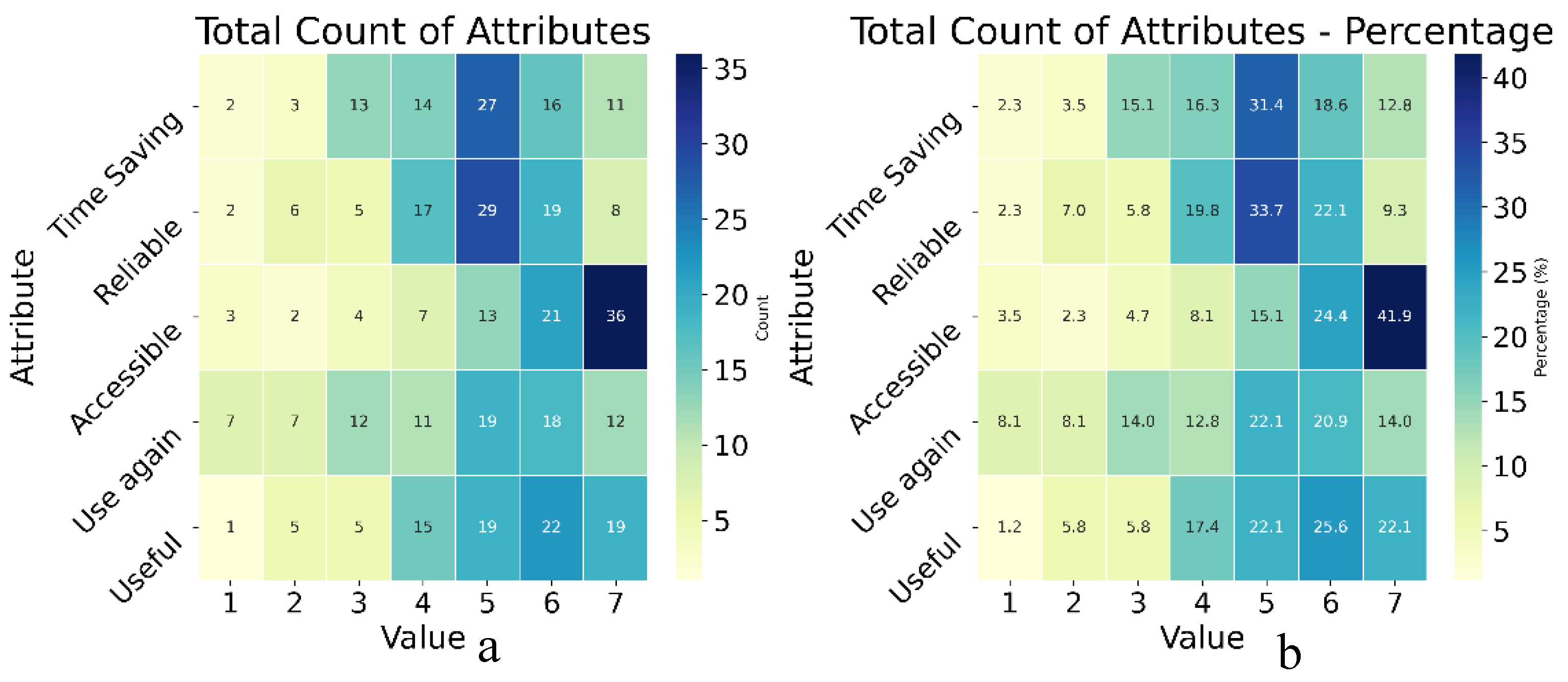

Eighty-six participants contributed to evaluating the OPES tool, which aligned with the success criteria outlined earlier (see

Figure 3). The sample included most archaeology students, followed by domain experts and members of the general public.

Participants responded using a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more tremendous perceived success of each criterion. These criteria included usefulness, time-saving, accessibility, likelihood of future use, and reliability. The results are in Appendix 1.

3.1. Combined Results

When considering all participant groups collectively, the OPES tool was rated positively across most success metrics. The highest scoring criterion was accessibility, with a mean score exceeding 5.25 and a modal score of 7 (

Figure 1), indicating widespread agreement that the tool was easy to use and navigate. Usefulness and reliability also received favourable evaluations, with both criteria surpassing the 3.5 midpoint on the Likert scale, suggesting that most users found the tool informative and sufficiently accurate. Meanwhile, time-saving potential and willingness to use it again produced more variable responses. Although both were rated above the neutral threshold, they did not reach the levels of endorsement seen for accessibility or usefulness.

These aggregate results suggest that OPES successfully meets its goal of increasing access to grey literature and demonstrates general acceptability across user demographics. Nonetheless, further insights can be gleaned by examining the results of individual user groups.

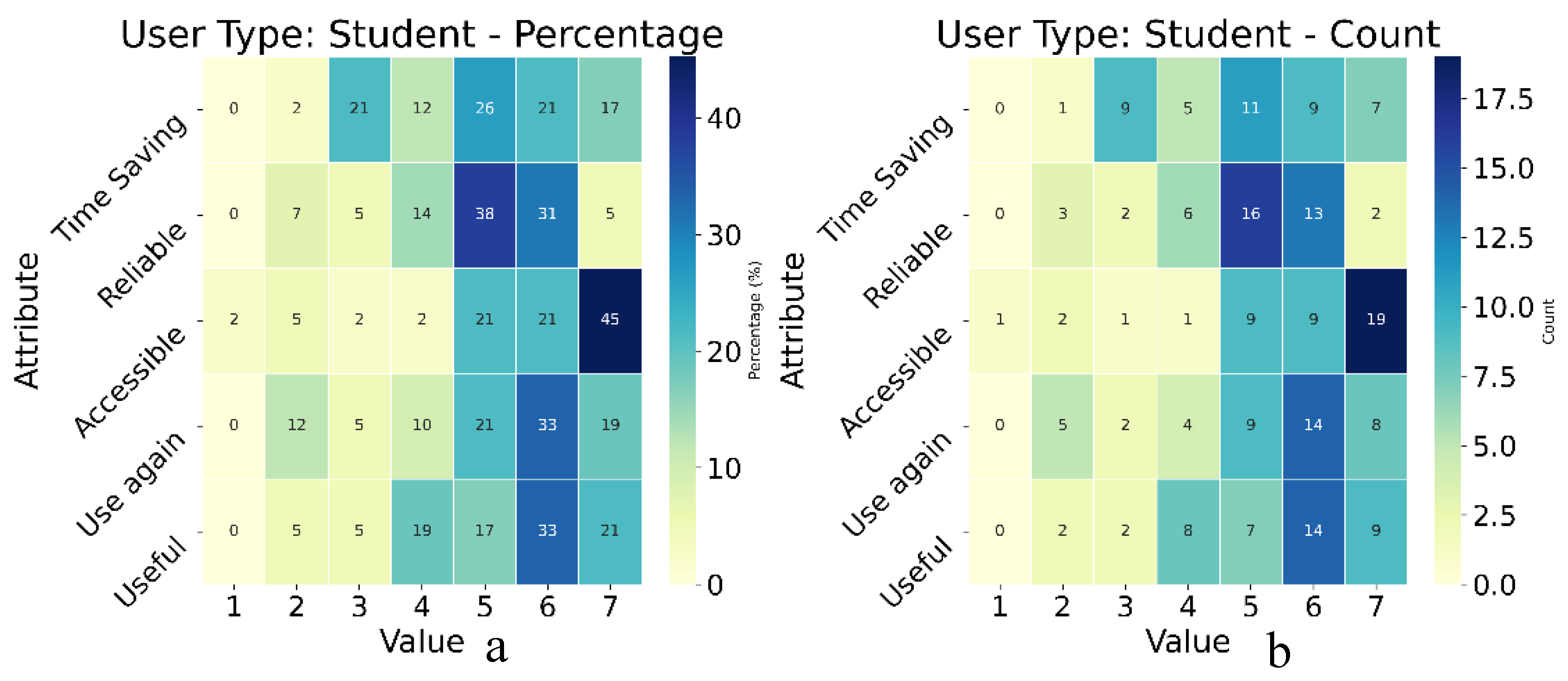

3.2. Students

Among the participant groups, archaeology students were the most enthusiastic in assessing the OPES tool. They awarded high ratings for both accessibility and usefulness, with scores that fully met the success criteria thresholds (

Figure 2). This suggests that students found the tool particularly supportive for learning and research. The remaining three criteria—reliability, time-saving, and willingness to use again—were also rated positively, each receiving average scores comfortably above the neutral midpoint. These results imply that OPES has strong potential to be integrated into academic settings, where students may benefit from its ability to surface relevant osteoarchaeological content without requiring exhaustive manual searches.

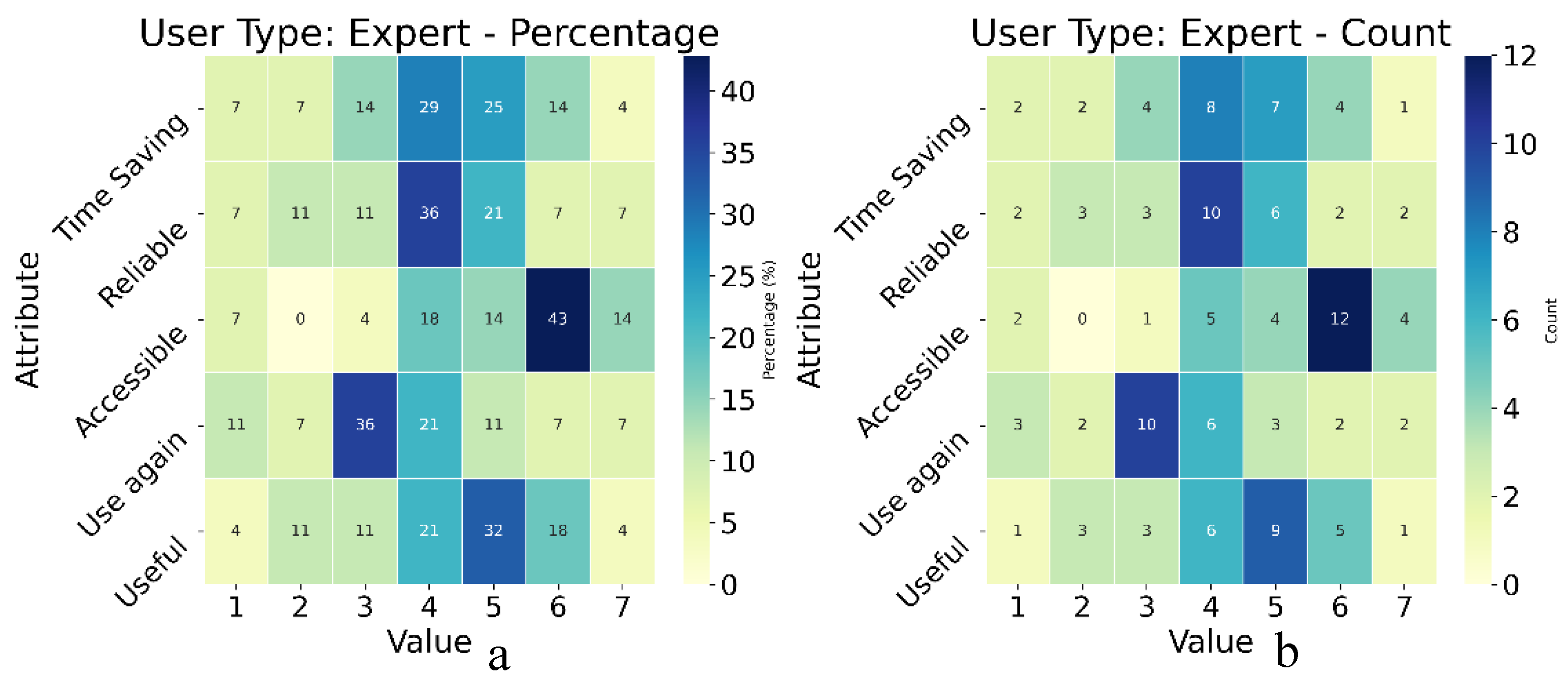

3.3. Experts

In contrast, domain experts provided more reserved and critical evaluations of the OPES tool (

Figure 3). While the criteria for usefulness, accessibility, and reliability were each partially met, they scored lower compared to the other two user groups. Experts were particularly sceptical regarding the willingness to use the again criterion, which received the lowest modal score (3) of all participant subsets, narrowly missing the threshold for partial success. This feedback may reflect higher expectations for precision, terminological nuance, and integration with established research methodologies. Though not dismissive of the tool’s potential, the expert evaluations suggest a need for refinement, especially in tailoring output to match the specific needs of professional archaeologists.

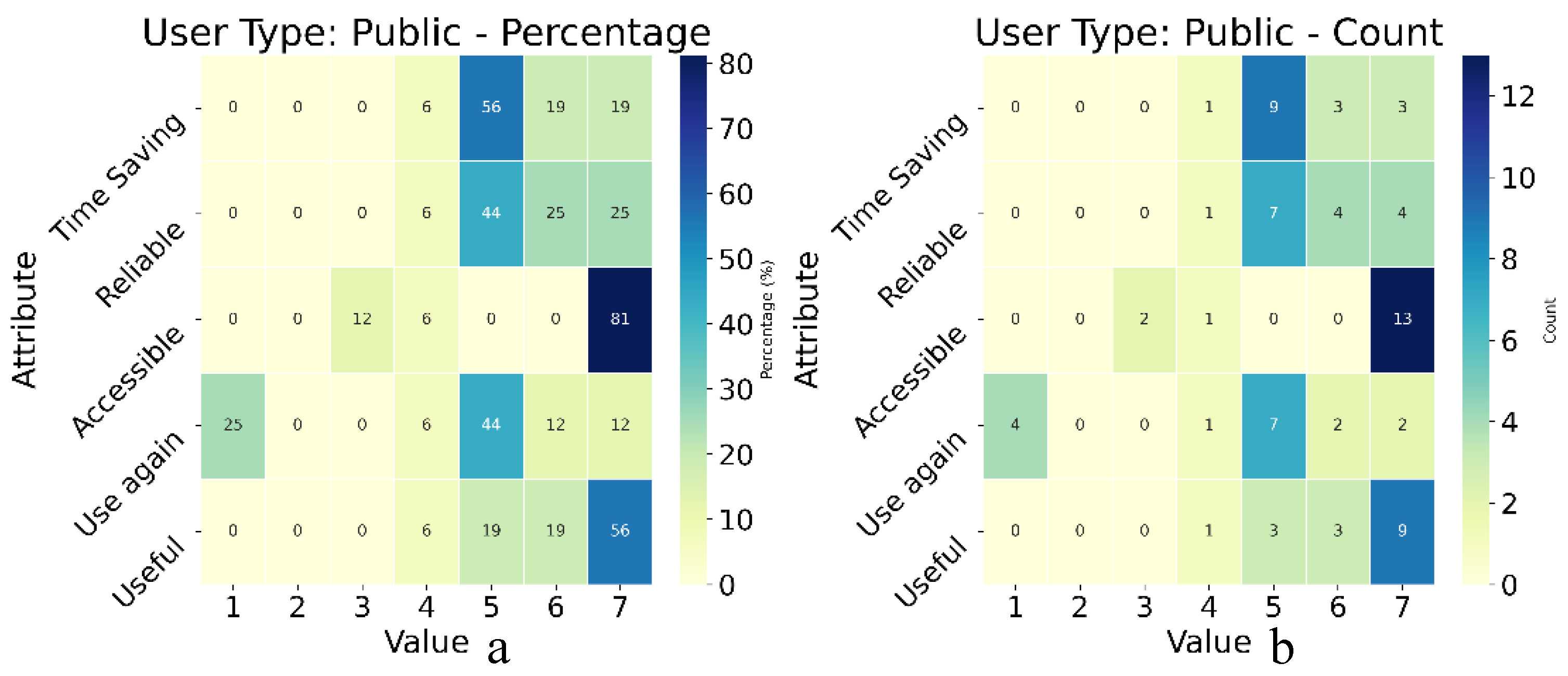

3.4. Public

The public participants, those without formal academic qualifications in archaeology, responded positively overall (

Figure 4). Their scores for accessibility and usefulness were comparable to those provided by students, indicating that OPES was intuitive and informative even for non-specialist users. While their willingness to use again score was lower than that of students, it remained higher than that of experts, perhaps reflecting a more casual interest in archaeological content rather than a sustained research need. The public’s favourable response highlights the potential for NLP and NER tools like OPES to foster broader engagement with heritage data and democratise access to archaeological information.

These findings show that OPES was at least partially successful in meeting all five evaluation criteria across the three groups. Its strongest attributes lie in making grey literature more accessible and easily navigable, especially for students and the general public. These outcomes suggest significant promise for lightweight, ethically designed NLP tools in educational and outreach contexts while pointing toward improvement areas in expert-facing implementations.

4. Discussion

The evaluation of the OPES tool offers a window into both the promise and limitations of applying lightweight Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Named Entity Recognition (NER) methods within digital archaeology. With increasing reliance on data-intensive research methods, particularly those powered by Large Language Models (LLMs), it is critical to examine how evaluation metrics and stakeholder responses should evolve to meet new technological benchmarks [

20,

21]. Recent developments in AI for cultural heritage have highlighted both opportunities and challenges in this rapidly evolving field [

18,

22].

4.1. Reliability

Reliability is a cornerstone of information extraction and semantic indexing. The OPES tool was only partially successful in this category in this study. While students and the public found the tool adequately reliable, experts were more critical—likely reflecting their familiarity with nuanced terminology and expectations for domain specificity.

While LLMs like BioBERT and GPT-4 offer significantly higher performance in entity recognition [

10,

12], they often obscure how results are derived, making error analysis more difficult. In contrast, OPES’s interpretable model architecture provides more precise diagnostic feedback, enabling domain experts to assess and refine output logic. While trading off some accuracy, this interpretability aligns with recent calls for more transparent and auditable AI in cultural heritage applications [

17].

4.2. Usefulness

The usefulness of OPES was broadly affirmed, especially by students and members of the public. The tool’s ability to extract key osteoarchaeological and palaeopathological terms was valued for its potential in teaching and public engagement. These results suggest that even with older techniques, tailored domain models can significantly enhance access to heritage data.

Experts were more ambivalent, reflecting an emerging challenge: as LLMs redefine performance standards, professional expectations will likely continue to rise. Usefulness must now be evaluated in terms of functionality and in relation to evolving standards of automation, semantic precision, and contextual sensitivity.

4.3. Time-Saving Potential

Participants rated OPES moderately on its time-saving potential. Again, students and public users saw more benefit than experts, perhaps due to differences in workflow integration. The variance in scores suggests that while OPES reduced the need for manual document review, the extracted data may not have always met expert standards for completeness or consistency.

Recent advances in few-shot and zero-shot learning with LLMs promise to address some issues by enabling more accurate and context-aware extraction from unstructured documents [

23]. However, these benefits come at significant energy and infrastructure costs. In contrast, tools like OPES offer a lean alternative for targeted applications, especially in educational settings or when dealing with large corpora of grey literature where high recall is more valuable than perfect precision.

4.4. Willingness to Use Again

This criterion emerged as the most challenging for OPES, particularly among experts. Although students and public users expressed moderate interest in future use, expert ratings suggest the tool did not yet meet expectations for repeat engagement. The lower scores here likely stem from concerns about reliability and integration rather than a rejection of the concept. These findings underscore the importance of iterative design: tools must adapt to meet the evolving needs of their users, and evaluation must consider not only immediate functionality but also longer-term engagement and trust.

4.5. Accessibility

Accessibility was OPES’s strongest performance area, with high scores across all user groups. The interface and functionality were well-received, confirming that lightweight NLP tools can serve as powerful enablers of access to archaeological information. As projects like Pelagios, ARIADNEplus, and Heritage Connector have shown, enhancing access to cultural datasets is one of AI’s most impactful roles in the heritage sector [

24,

25].

That said, accessibility must also now contend with the expanding reach of conversational agents, chat-based search, and multi-modal LLMs that offer seemingly seamless user experiences. OPES’s success in this area affirms the value of minimalist design and focused functionality, particularly for academic and public sector deployments where simplicity and clarity are often more helpful than feature-saturated platforms.

The analysis suggests that while OPES may not match LLMs in computational sophistication, it provides an important ethical and sustainable alternative, which successfully meets archaeological researchers needs at multiple levels. It also reinforces the ongoing importance of carefully defined evaluation metrics in determining “success” in the evolving landscape of AI for heritage.

4.6. Implications for Heritage AI

The evaluation of the OPES prototype highlights key tensions between technological capability, ethical responsibility, and practical usability in deploying AI systems for cultural heritage. While the landscape of natural language processing is rapidly shifting towards high-performance models such as GPT-4, BioBERT, and other transformer-based architectures [

10,

23], the findings of this study suggest that lightweight, interpretable models still have an important role to play—particularly when viewed through the lens of sustainability, reproducibility, and accessibility.

The relatively high scores OPES received from students and the public illustrate the tool’s value in opening up grey literature for non-specialist use. This is especially significant in archaeological contexts, where much data remains siloed in difficult-to-access PDF reports. While LLMs may offer more advanced functionality, their workflow integration often requires significant infrastructure, licensing arrangements, and technical support [

15]. In contrast, OPES demonstrates that a leaner model can still yield meaningful improvements in data findability and reusability while remaining transparent, portable, and affordable.

The findings also underscore the continued importance of human-centred evaluation in heritage AI. As expectations rise in step with AI performance, evaluation frameworks must evolve accordingly to assess accuracy and interrogate user trust, accessibility, sustainability, and alignment with domain values [

17,

20]. The methodology used here—combining qualitative and quantitative feedback from diverse participant groups—offers a replicable model for this kind of robust and inclusive evaluation.

Finally, this study contributes to ongoing discussions around digital archaeologists’ and heritage scientists’ environmental and ethical responsibilities. As research communities increasingly recognise the carbon and social costs of large-scale AI [

14,

16], tools like OPES provide an important counterpoint: demonstrating that progress in digital archaeology does not always require cutting-edge infrastructure but can be driven by thoughtful design, user responsiveness, and methodological transparency. This aligns with current initiatives exploring sustainable AI approaches in archaeological research [

18,

26].

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates whether lightweight, interpretable Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Named Entity Recognition (NER) methods could enhance the reusability and accessibility of osteoarchaeological and palaeopathological data embedded within grey literature. In doing so, it introduced OPES (Osteoarchaeological and Palaeopathological Entity Search) as both a technical prototype and an ethical intervention—responding not only to the practical limitations of PDF-based heritage reports but also to the broader call for sustainable, responsible AI in archaeology.

The results indicate that OPES successfully meets its primary goals of improving findability and accessibility, especially among students and public users. Although its reliability and time-saving performance were more modest—particularly when assessed by domain experts—these findings reflect the broader challenges of designing tools that serve specialist and generalist communities. Significantly, OPES’s transparent, user-centred design was viewed positively, reaffirming the value of simplicity, explainability, and methodological rigour in heritage informatics.

Importantly, this study positions OPES within the broader discourse on ethical AI and environmental sustainability. As Large Language Models (LLMs) increasingly shape expectations around automation, accuracy, and functionality, there is a growing need to re-evaluate what constitutes successful digital innovation—particularly in fields like archaeology, where data preservation, interpretive nuance, and reproducibility are central concerns. In contrast to opaque and energy-intensive AI systems, OPES demonstrates how modest technical approaches can yield meaningful and scalable results when thoughtfully designed and rigorously evaluated.

The framework used to evaluate OPES also contributes to heritage AI. By combining qualitative insights and quantitative metrics across diverse user groups, the study provides a replicable model for assessing AI tools in a way that respects the specific needs and values of the heritage sector. Such evaluation strategies will become increasingly important as tools are deployed in complex socio-technical environments where success cannot be reduced to accuracy scores alone.

Looking forward, OPES offers a proof of concept and a platform for future development. Its modular design could be extended with selectively applied LLM components, enhanced with richer ontologies, or embedded into wider digital infrastructures such as ADS or ARIADNE. However, any such advances must remain grounded in this project’s principles: transparency, inclusivity, and responsiveness to community needs.

In sum, OPES is a practical and principled response to the challenge of unlocking grey literature in bioarchaeology. It shows that when paired with ethical awareness and robust evaluation, small, targeted interventions can contribute significantly to the FAIR data agenda and help build a more equitable and sustainable digital archaeology

Funding

This research was funded by AHRC, grant number AH/W002469/1 and the APC was funded by the aforementioned.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPES |

Osteoarchaeological and Palaeopathological Entity Search |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| NER |

Named Entity Recognition |

| FAIR |

Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable |

| ADS |

Archaeology Data Service |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| MeSH |

Medical Subject Headings |

| aDNA |

Ancient DNA |

Appendix A

| Do you think of yourself as an: |

Do you think this tool is time saving? |

Are the results reliable? |

How accessible was this tool to use? |

Would you like to use this tool again? |

How useful is this tool for research for archaeologists? |

|

| Non-archaeologists |

6 |

7 |

7 |

1 |

7 |

|

| Non-archaeologists |

7 |

5 |

7 |

1 |

5 |

|

| Non-archaeologists |

5 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Non-archaeologists |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Student |

6 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

4 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Student |

3 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

|

| Non-archaeologists |

5 |

5 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

6 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Student |

3 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

|

| Student |

7 |

3 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

7 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

6 |

|

| Student |

3 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

|

| Student |

6 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

|

| Expert |

6 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Student |

5 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

2 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

|

| Student |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

| Student |

5 |

4 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

5 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

|

| Student |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

5 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

|

| Student |

4 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

|

| Student |

6 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Student |

5 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

|

| Expert |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

1 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

|

| Expert |

3 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

|

| |

| |

| Expert |

5 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

|

| Student |

5 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

6 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

3 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

|

| Student |

6 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

|

| Student |

5 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Expert |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Student |

5 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

|

| Student |

3 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

|

| Student |

7 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Expert |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

|

| Student |

5 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

|

| Student |

5 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

5 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

|

| Student |

7 |

5 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Student |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

6 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

| Expert |

5 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

5 |

|

| Student |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

|

| Student |

6 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

|

| Student |

4 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

|

| Expert |

6 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Expert |

2 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

|

| Student |

4 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

4 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

5 |

5 |

3 |

6 |

4 |

|

| Expert |

2 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

|

| Expert |

6 |

5 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

|

| Expert |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

| Student |

3 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

|

| Expert |

5 |

4 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

|

| Expert |

4 |

4 |

6 |

3 |

5 |

|

| Expert |

6 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

|

| Student |

3 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

|

| Expert |

5 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

|

| Expert |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

| Student |

6 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

|

| Student |

6 |

5 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

4 |

5 |

7 |

5 |

4 |

|

| Expert |

5 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

|

| Expert |

3 |

4 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

|

| Student |

7 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Student |

7 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

| Expert |

5 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

| Student |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

Non-

archaeologists |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

References

- Britton, K.; Richards, M.P. Introducing Archaeological Science. In Archaeological Science: An Introduction; Richards, M.P., Britton, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, J.; Welker, F.; Demarchi, B.; Speller, C.; Warinner, C.; Collins, M.J. A guide to ancient protein studies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonino da Silva Santos, L.O.; Bonino, L.; Pariente, T.J.; Kuhn, T. FAIR Data Points Supporting Big Data Interoperability. In Enterprise Interoperability VII; Popplewell, K., Thoben, K.D., Knothe, T., Poler, R., Eds.; STE Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lien-Talks, A. How FAIR Is Bioarchaeological Data: With a Particular Emphasis on Making Archaeological Science Data Reusable. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2024, 7, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talboom, L. Improving the Discoverability of Zooarchaeological Data with the Help of NLP. Master’s Thesis, University of York, York, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, S.; Richards, J.D.; Ciravegna, F.; Waller, S.; Chapman, S.; Zhang, Z. The Archaeotools Project. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2009, 367, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudhope, D.; Binding, C.; Jeffrey, S.; May, K.; Vlachidis, A. A STELLAR Role for Knowledge Organization Systems in Digital Archaeology. Bull. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 37, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, L. Lines of Sight: Modelling straight-line travel in ancient Mediterranean sailing. Internet Archaeol. 2011, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltagy, I.; Lo, K.; Cohan, A. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 3615–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Kovaleva, O.; Rumshisky, A. A Primer in BERTology: What We Know About How BERT Works. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 842–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubell, E.; Ganesh, A.; McCallum, A. Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 3645–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Mitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event, Canada, 3–10 March 2021; pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ignazio, C.; Klein, L.F. Data Feminism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci, M.; Khoroshiltseva, M.; Pontil, M.; Traviglia, A.; Del Bue, A.; James, S. Artificial Intelligence for Digital Heritage Innovation: Setting up a R&D Agenda for Europe. Heritage 2024, 7, 1028–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, W.; Tullis, T. Measuring the User Experience: Collecting, Analyzing, and Presenting Usability Metrics, 2nd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- van Dis, E.A.M.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; Bockting, C.L.H.; Schoevers, R.A. ChatGPT: Five Priorities for Research. Nature 2023, 614, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Z.; Lin, H.; Lu, Z. Evolution and emerging trends of named entity recognition: Bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2023. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0297874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donciu, C.M.; Foschini, L.; Martoglia, R. A novel NLP-driven approach for enriching artefact descriptions, provenance, and entities in cultural heritage. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 2587–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, E.; Terras, M.; Nyhan, J. The Heritage Connector: A machine learning framework for building linked open data from museum collections. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2021, 36, ii23–ii43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghini, C.; Barker, E.; Binding, C.; Tudhope, D. ARIADNE: A Research Infrastructure for Archaeology. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2017, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workshop: Big Data and Archaeology: Towards an AI Solution. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Big Data and Archaeology, Mainz, Germany, 6–7 June 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).