1. Introduction

Cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) has become one of the fastest-growing components of digital trade in recent years. According to the WTO and OECD [

1], digital trade, including CBEC transactions, has continued to expand rapidly, driven by greater global connectivity and digital platforms. In China, official customs data show that the total value of CBEC imports and exports reached RMB 2.38 trillion in 2023, representing a 15.6 percent year-on-year increase [

2]. Cosmetics are among the leading product categories in CBEC retail imports, accounting for more than 40 percent of transactions in some surveys [

3]. As cosmetics are high-value and experience-oriented products closely related to health and appearance, authenticity and safety concerns are particularly salient. Thus, consumer trust has become a decisive factor for the sustainable development of CBEC platforms in this sector.

Despite rapid expansion, CBEC faces persistent challenges in fostering consumer confidence. Counterfeit products, inconsistent quality, unreliable logistics, and inadequate post-purchase protection frequently undermine trust, exposing consumers to heightened uncertainty [

4,

5]. Compared with domestic e-commerce, cross-border transactions exacerbate information asymmetry because of geographic distance and complex global supply chains, which amplify consumers’ perceived risk [

4]. High levels of perceived risk have been shown to suppress consumer engagement and reduce purchase intention across e-commerce platforms [

6,

7]. Addressing these risks through effective trust-building mechanisms is therefore both a managerial necessity and an important avenue of academic inquiry. Perceived risk has long been identified as a key determinant of consumer behavior in digital commerce. Without the ability to physically inspect products, consumers rely on signals and cues to assess authenticity and credibility. High perceived risk amplifies concerns over financial loss, product performance, and security, which suppresses purchase intention [

6,

8,

9]. In CBEC contexts, these concerns are even more pronounced, as consumers also face uncertainties related to customs clearance, delivery reliability, and dispute resolution [

4,

7]. This makes perceived risk particularly salient in shaping trust and purchase intention in cross-border settings.

To address these challenges, CBEC platforms have increasingly adopted authenticity signals to mitigate consumer concerns. Traditional mechanisms include platform self-operation labels, verified customer reviews, and risk-bearing commitments such as “fake one, pay ten” or unconditional return guarantees (Zhang & Pertheban, 2023) [

10]. Grounded in signaling theory (Spence, 1973), these cues reduce information asymmetry and enable consumers to infer product authenticity and seller credibility. Empirical research confirms that platform-backed endorsements, certification labels, and compensation guarantees enhance consumer trust and stimulate purchase intention [

11,

12]. Similarly, customer reviews function as vital social proof, where review volume, valence, and credibility significantly influence consumer decisions [

13,

14]; Nevertheless, the reliability of these traditional signals has been questioned: reviews may be fabricated or manipulated [

15], self-operation is costly and difficult to scale, and compensation policies are often inconsistently enforced [

16,

17]. Recent advances in blockchain technology provide new opportunities for authenticity signaling. Blockchain enables immutable, transparent, and verifiable records of product origins and supply chain processes [

18]. In high-risk industries such as luxury goods, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics, blockchain-based traceability has been shown to enhance consumer trust and willingness to pay [

19,

20]. Unlike traditional signals that depend on institutional authority, blockchain creates decentralized, technology-driven trust validated through transparent records and smart contracts [

21,

22]. Nevertheless, its signaling effectiveness is not guaranteed. Consumers often lack familiarity with blockchain applications, and the reliability of data inputs remains problematic—if false or incomplete information is entered, blockchain cannot ensure authenticity (“garbage in, garbage out”) [

23,

24]. Moreover, concerns about privacy and the trade-off between transparency and data protection further limit consumer acceptance [

25].

Although signaling theory has been widely applied in e-commerce research, important gaps remain. First, prior studies focus predominantly on traditional signals such as platform certification, customer reviews, and refund policies [

26,

27], often without rigorous theoretical grounding on how these mechanisms mitigate uncertainty in online exchange environments [

28]. Second, while mediating mechanisms such as perceived quality and perceived value have been explored [

29], the role of perceived risk—arguably more critical in high–uncertainty cross-border contexts—remains underexamined. Third, most prior research relies on surveys rather than controlled experiments, leaving how signals jointly operate unanswered. Finally, although some recent studies have examined the role of external cues in shaping CBEC purchase decisions [

30] Little is known about how consumers integrate blockchain cues with traditional signals in sensitive product categories such as cosmetics.

This study addresses these gaps by employing a between-subjects experimental design grounded in signaling theory to compare four authenticity signals commonly used in CBEC: blockchain traceability labels, platform self-operation, customer reviews, and compensation guarantees. It examines both the direct effects of these signals on purchase intention and the indirect effects mediated by perceived risk. The contributions of this study are threefold. First, it advances signaling theory by systematically comparing blockchain-based and traditional signals within a unified framework. Second, it empirically demonstrates the mediating role of perceived risk in cross-border contexts, offering a more nuanced understanding of trust formation. Third, it offers practical guidance for CBEC managers on designing multi-signal trust strategies that effectively balance technology-driven and traditional mechanisms to mitigate consumer risk and enhance purchase intention.

2. Theoretical Background and Related Work

2.1. Signaling Theory and Its Role in E-Commerce

Signaling theory, originally introduced by Spence [

31], provides a powerful framework for understanding how observable cues help reduce information asymmetry in markets. In contexts where buyers cannot directly evaluate product attributes before purchase, sellers rely on signals to communicate credibility, authenticity, and quality. Effective signals are typically characterized as being costly or difficult to imitate, which ensures their reliability in shaping buyer perceptions.

Within e-commerce research, scholars have frequently drawn on signaling theory to analyze how online sellers and platforms use mechanisms such as certifications, reviews, and guarantees to reduce consumer uncertainty and perceived risk [

32]. Empirical evidence confirms that trust signals significantly influence consumers’ perceptions and behaviors: verified reviews and platform labels enhance product credibility, while compensation policies serve as explicit assurances against potential loss (Kim & Peterson, 2017; Stouthuysen et al., 2018) [

26,

27]. For example, Chevalier and Mayzlin [

13] demonstrated how online reviews act as powerful word-of-mouth signals that affect consumer purchase decisions, providing an early foundation for the study of user-generated cues in digital marketplaces.

More recently, the emergence of blockchain as a transparency-enhancing technology introduces new signals that differ fundamentally from conventional cues, relying on technological validation rather than institutional enforcement. This shift opens fertile ground for extending signaling theory by comparing how traditional and technology-based signals function in high-risk environments such as CBEC [

33].

2.2. Traditional Authenticity Signals

In CBEC, traditional authenticity signals remain central to building consumer trust, especially when buyers lack familiarity with the seller or product. One prominent institutional signal is platform endorsement, such as self-operation labels or official store badges (e.g., “Tmall Global Supermarket”). These signals represent the platform’s certification of legitimacy and operational reliability, thereby strengthening brand credibility and reducing uncertainty [

34,

35,

36]. Studies also show that such endorsements not only reduce cognitive perceptions of risk but also foster emotional attachment and willingness to pay a premium [

37].

A second type of signal is risk-bearing commitments, such as “tenfold compensation for counterfeits” policies or unconditional return guarantees. By explicitly addressing consumer concerns over product quality and post-purchase protection, these commitments provide psychological assurance and encourage transactions in high-uncertainty contexts [

38,

39]. These measures have been found to improve consumer satisfaction, foster loyalty, and increase the probability of repeat purchases (Li & Liu, 2021; Liu & Chen, 2022) [

12,

40].

The third key form of authenticity signal is customer reviews, which function as user-generated content and provide social proof of product credibility. Review volume, quality, and emotional valence have been shown to influence consumer trust and purchase intention [

14,

41,

42]. However, in CBEC contexts, the prevalence of fake or manipulated reviews raises consumer skepticism and weakens their signaling value. Recent empirical evidence from Tmall Global further demonstrates that while external cues such as reviews significantly shape purchase decisions, their effectiveness diminishes when credibility is questioned [

30]. Recent cases of fabricated reviews on leading platforms further challenge their reliability as trust signals, creating an urgent need to re-examine whether consumer reviews still act as effective trust cues in cross-border markets.

Although these traditional signals play a vital role, they may not fully overcome the authenticity challenges in CBEC. They are vulnerable to manipulation, costly to maintain, or inconsistently enforced, and thus may fail to provide sufficient reassurance for consumers in high-risk categories such as cosmetics. This limitation underscores the importance of exploring how emerging technology-driven signals, particularly blockchain, can complement or substitute traditional mechanisms.

2.3. Blockchain as an Emerging Signal

Blockchain technology has been increasingly explored as a technology-driven authenticity signal in CBEC. Its core properties—immutability, transparency, and traceability—make it uniquely suited to contexts where consumers are concerned about counterfeit products, supply chain integrity, and data credibility. From a signaling perspective, blockchain generates tamper-proof and auditable records of product origin, production, and distribution, which serve as high-cost and hard-to-fake signals of authenticity[

43,

44]. Unlike platform-based signals that rely on institutional authority, blockchain provides decentralized verification, thereby enhancing credibility through technical validation [

45,

46].

Its efficacy has been shown across several sectors. Blockchain makes farm-to-table traceability possible in the food industry, boosting customer trust in quality and safety [

19,

20]. By enabling customers to independently confirm the authenticity of premium items, it aids in the fight against counterfeiting [

47,

48]. By protecting transaction data and guaranteeing compliance, it keeps fake medications out of the supply chain in the pharmaceutical industry [

49]. These uses imply that blockchain can function both directly by increasing the legitimacy of technology and indirectly by lowering perceived risk.

Despite these advantages, several barriers hinder its signaling effectiveness. Its technical complexity may limit consumer understanding of how it ensures authenticity [

47]. Moreover, blockchain cannot guarantee data accuracy if the inputs themselves are flawed—

garbage in, garbage out remains a critical limitation [

23,

33]. Consumer skepticism may also arise if blockchain-based features are poorly communicated [

48]. Furthermore, low awareness, limited exposure, and privacy concerns restrict its widespread adoption [

25,

52]. These challenges indicate that blockchain cannot yet function as a stand-alone solution but may be most effective when combined with traditional authenticity signals. This highlights the importance of investigating multi-signal strategies in CBEC, particularly in sensitive sectors such as cosmetics. Recent empirical studies also highlight blockchain’s role in strengthening consumer trust and purchase intentions in CBEC contexts, while pointing out variations in consumer sensitivity and retailer adoption strategies [

49,

50,

51].

2.4. Research Gaps

Although signaling theory has been widely applied in e-commerce, several important gaps remain in the context of CBEC. First, most studies focus on traditional authenticity signals such as platform labels, customer reviews, and refund policies [

26,

27], with limited systematic comparison to blockchain-based mechanisms, despite recent calls to examine technology-driven signals in greater depth [

49]. Second, prior research has mainly examined signals in isolation, neglecting how multiple signals may interact or produce substitution and complementarity effects. This omission is noteworthy given emerging evidence that external cues in CBEC, such as reviews and platform information, jointly shape consumer decision-making [

30]. Third, while mediating mechanisms such as perceived quality and perceived value have been investigated [

29], the role of perceived risk—arguably more critical in high-uncertainty CBEC contexts—has not been systematically validated, despite recent meta-analytical and review evidence emphasizing its decisive role in suppressing purchase [

52]. Finally, most existing studies rely on survey-based methods, whereas controlled experiments that allow for causal inference remain scarce, particularly in high-risk categories such as cosmetics.

3. Research Hypotheses and Theoretical Model

Building on signaling theory and prior studies of consumer behavior in CBEC, this study investigates how four authenticity signals, namely blockchain traceability, platform self-operation, customer reviews, and compensation guarantees, shape purchase intention. We specifically look at how they affect consumer decision-making directly as well as indirectly through perceived risk, a technique that is especially important in high-uncertainty CBEC situations like cosmetics.

3.1. Direct Effects of Authenticity Signals on Purchase Intention

Authenticity signals are central mechanisms in reducing information asymmetry between sellers and consumers [

31]. In CBEC, consumers often face uncertainty regarding product authenticity, quality, and transaction safety due to the geographical and institutional distance of overseas sellers. Prior research highlights that signals which are observable, credible, and difficult to imitate can directly enhance consumer confidence and increase their purchase likelihood [

18,

53].

H1.

Authenticity signals have a significant direct effect on consumers’ purchase intention.

Blockchain Traceability

Blockchain offers transparent, unchangeable records of product origin, logistics, and distribution, introducing a technology-based authenticity signal. Blockchain applications in supply chains have been demonstrated to increase authenticity perceptions, decrease fraud, and improve traceability [

19,

33]. Blockchain is anticipated to immediately boost purchase intention for CBEC cosmetics by allowing customers to confirm product history using tamper-proof data. H1a. Purchase intention is positively impacted by blockchain traceability.

Strong platform endorsement and operational control are shown in institutional signals such as platform self-operation (e.g., “Tmall Global Supermarket”). Better after-sales support, more stringent product procurement, and a decreased danger of counterfeit products are all linked to self-operated businesses [

10]. Customers are therefore more likely to view self-operation as a reliable assurance of product quality, which raises their propensity to buy. H1b. Purchase intention is positively impacted by platform self-operation.

Consumer evaluations reduce uncertainty in online transactions by serving as social evidence, indicating shared product experiences. Positive reviews have been shown to boost consumers’ readiness to buy and to build credibility [

58]. Nevertheless, reviews may be viewed as less trustworthy in CBEC environments because of manipulation concerns, which might reduce their impact [

59]. It is nevertheless anticipated that favorable evaluations would directly influence purchasing intention in spite of this restriction.

H1c. Purchase intention directly benefits from customer feedback.

Compensation mechanisms such as the “fake one, pay ten” policy provide explicit institutional risk-sharing, signaling sellers’ confidence in product authenticity. Such guarantees not only reduce consumers’ perceived financial loss but also strengthen their confidence in making a purchase [

38,

39]. Accordingly, compensation commitments are hypothesized to positively influence purchase intention in CBEC cosmetics.

H1d. Purchase intention is positively impacted by compensation guarantees.

3.2. Mediating Role of Perceived Risk

Perceived risk is widely recognized as a critical mechanism through which authenticity signals influence consumer behavior) [

54]. In CBEC contexts, uncertainty regarding authenticity, logistics reliability, and transaction safety is heightened compared to domestic e-commerce [

8]. By reducing perceived risk, authenticity signals can indirectly enhance consumers’ willingness to purchase, making perceived risk a key mediating variable in this study.

H2.

Perceived risk mediates the relationship between authenticity signals and purchase intention.

Blockchain technology reduces consumers’ uncertainty by providing verifiable and tamper-proof supply chain data. Prior research demonstrates that blockchain enhances transparency, traceability, and accountability, thereby reducing fraud risks and alleviating consumer concerns about counterfeit goods [

19,

33]. In CBEC cosmetics, blockchain-driven traceability is expected to lower perceived risk, which in turn increases purchase intention.

H2a

Perceived risk mediates the relationship between blockchain traceability and purchase intention

Platform self-operation serves as an institutional guarantee that the seller adheres to rigorous sourcing, distribution, and after-sales standards. Prior studies show that institutional assurances reduce uncertainty and transaction risks, thus encouraging consumers to engage in online purchases [

10,

39]. In CBEC, self-operated platforms can reduce consumer concerns about counterfeit or substandard cosmetics, indirectly promoting purchase intention via risk reduction.

H2b.

Perceived risk mediates the relationship between platform self-operation and purchase intention.

By supplying firsthand information from other buyers, customer reviews act as social proof in online markets and minimize uncertainty by delivering experienced insights from other buyers [

58]. In many e-commerce contexts, reviews have been shown to lower perceived risk; however, in CBEC, they may be less helpful due to customer skepticism over authenticity and potential manipulation [

59]. Positive assessments, however, can nonetheless reduce risk and, when regarded as trustworthy, indirectly increase purchase intention.

H2c. It is perceived risk that mediates the relationship between customer reviews and intention to buy.

Compensation commitments, such as the “fake one, pay ten” policy, provide consumers with explicit financial assurance against counterfeit products. These mechanisms transfer risk from consumers to sellers or platforms, thus directly lowering perceived financial and psychological risks [

38]. In CBEC cosmetics, compensation guarantees are expected to significantly reduce perceived risk and thereby increase consumers’ likelihood of purchasing.

H2d.

Perceived risk mediates the relationship between compensation guarantees and purchase intention.

3.3. Moderating Effects of Signal Interactions

While authenticity signals can individually influence consumers’ perceptions and behaviors, their effectiveness may not be constant across contexts. Recent research in signaling theory emphasizes that signals may interact, and the presence of multiple signals can either amplify or diminish their impact. In CBEC settings, where multiple authenticity cues often coexist, it is essential to examine how blockchain interacts with traditional signals (platform self-operation, customer reviews, and compensation guarantees) in shaping consumer perceptions and purchase decisions. Accordingly, this study introduces moderation hypotheses to capture these conditional effects.

H3.

The effects of blockchain traceability on perceived risk and purchase intention are moderated by the presence of traditional authenticity signals.

Institutional signals such as platform self-operation are perceived as high-credibility guarantees. When blockchain traceability is combined with self-operation, the incremental value of blockchain may be attenuated, as consumers already rely on the institutional trust provided by the platform. Conversely, in the absence of self-operation, blockchain may become more salient as a substitute mechanism to mitigate uncertainty.

H3a. The impact of blockchain traceability on perceived risk and purchase intention is stronger in non-self-operated platforms compared to self-operated platforms.

Customer reviews provide social proof, but their credibility is often questioned in CBEC contexts due to concerns over manipulation. When positive reviews are absent, blockchain traceability becomes a critical assurance mechanism. However, when abundant positive reviews are present, consumers may rely more on peer feedback, thereby weakening the incremental role of blockchain.

H3b. The impact of blockchain traceability on perceived risk and purchase intention is stronger when customer reviews are absent than when reviews are present.

Compensation Guarantees as a Moderator

Compensation commitments act as explicit financial safeguards, directly reducing consumer risk perceptions. In the absence of compensation guarantees, blockchain may serve as the primary mechanism for authenticity assurance. However, when compensation guarantees are available, the marginal effect of blockchain is likely reduced, as risk is already mitigated by the guarantee.

H3c. The impact of blockchain traceability on perceived risk and purchase intention is stronger when compensation guarantees are absent than when they are present.

3.4. Theoretical Model

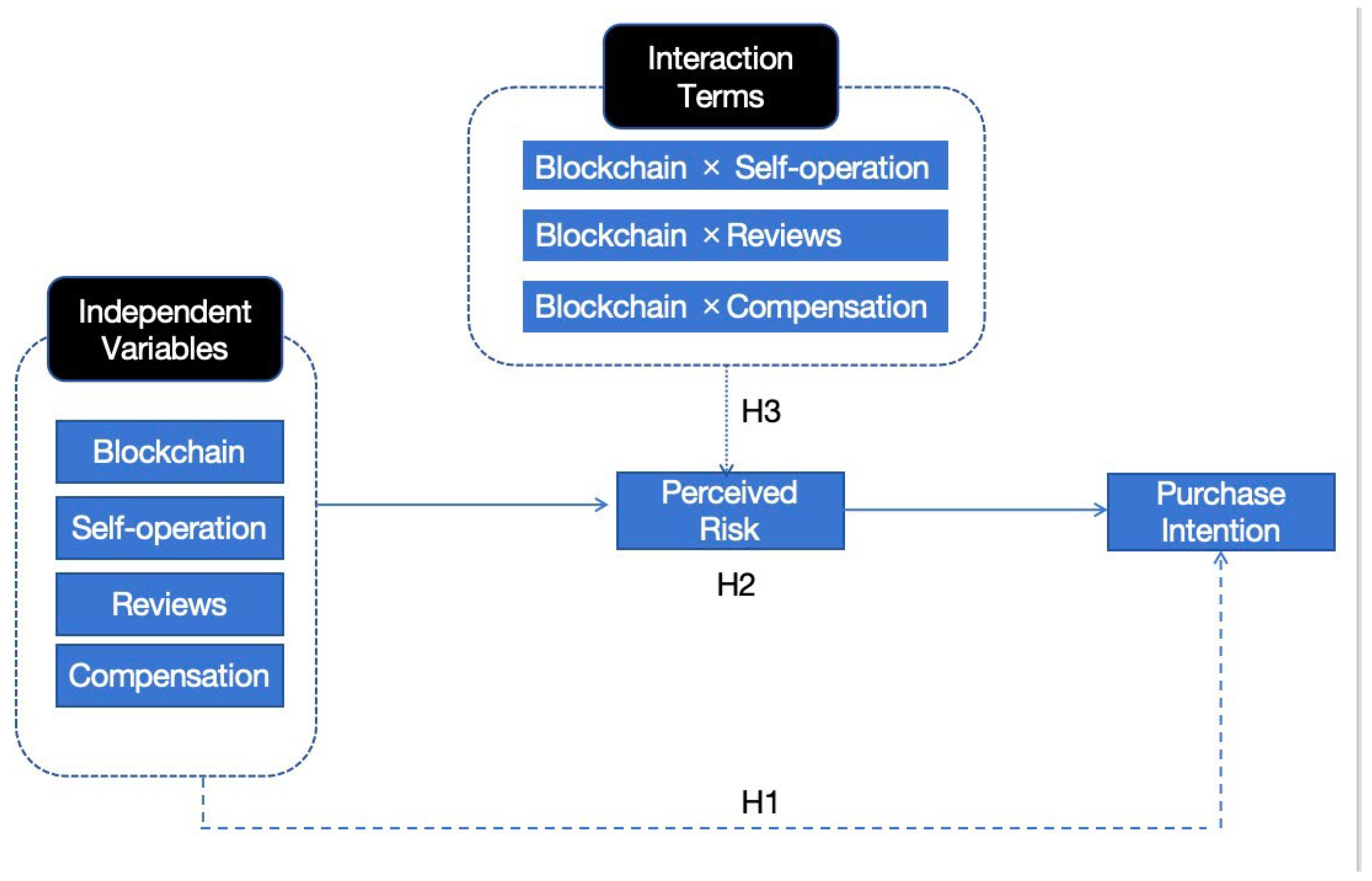

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model that is proposed. As independent variables, four authenticity signals are used: compensation promises, platform self-operation, blockchain traceability, and user reviews. In addition to being a direct result of these signals, perceived risk also acts as a mediator between them and the dependent variable, purchase intention. Thus, (1) the direct effects of authenticity signals on purchase intention, (2) the direct effects of authenticity signals on perceived risk, (3) the mediating role of perceived risk between authenticity signals and purchase intention, and (4) the moderating role of traditional signals in influencing the efficacy of blockchain traceability can all be empirically tested thanks to the framework.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Experimental Design and Stimuli

This study employed an orthogonal experimental design to examine the effects of four authenticity signals, namely blockchain traceability labels, platform self-operation, customer reviews, and compensation guarantees, on perceived risk and purchase intention in the CBEC cosmetics context. Each factor was manipulated at two levels (present versus absent).

Figure 2 illustrates an example of the CBEC product page stimulus (Scenario 1, all signals present), with manipulated elements annotated in English. Only participants assigned to Scenario 1 viewed this version, while others saw versions corresponding to their assigned scenario.

The stimuli were simulated CBEC product pages for imported cosmetics. All pages adopted a standardized layout, with variations applied to the authenticity signals: (1) blockchain traceability was presented through a QR code and descriptive text; (2) platform self-operation was indicated by an official “Tmall Supermarket”-style label; (3) positive customer reviews appeared in a dedicated review section; and (4) the compensation guarantee (“fake one, pay ten”) was displayed as a badge. Each page was displayed for 45 seconds to ensure that participants had sufficient time to recognize and process the relevant information.

The orthogonal array reduced the number of scenarios from 16 to 8, which improved design efficiency and minimized unnecessary participant burden at the study level. The design matrix is shown in

Table 1.

To ensure the validity of manipulations, a preliminary expert validation was conducted with three scholars specializing in e-commerce and consumer behavior. The experts confirmed that the four authenticity signals were realistic, clearly identifiable, and suitable for the CBEC cosmetics context. Based on their feedback, minor wording adjustments were made to the blockchain and compensation guarantee descriptions for clarity. The 45-second exposure time was determined through preliminary pretests. Although 30 seconds was sufficient for basic page browsing, extending the duration to 45 seconds provided participants with more time to fully process the signals while avoiding unnecessary fatigue. This duration, therefore, represents a balanced compromise between adequate information processing and participant efficiency.

4.2. Participants and Sampling

Participants were recruited through the Jianshu online crowdsourcing platform. To ensure homogeneity and internal validity, the following eligibility criteria were applied:

Platform credit score ≥ 80;

Historical task acceptance rate ≥ 80%;

Female respondents;

Age between 26 and 30 years;

Prior CBEC shopping experience.

The selection of young female consumers was based on the sampling options available on the Jianshu crowdsourcing platform, which allows researchers to predefine respondents’ demographic attributes such as gender and age. Among the available age groups, women aged 26–30 were chosen because they represent a core consumer segment in the cosmetics market and are most relevant to the study context. Before participation, Participants needed to respond to a preliminary screening item: “Have you previously bought products via CBEC platforms?” Only those answering “Yes” were included.

A total of 320 questionnaires were distributed evenly across the eight scenarios using random assignment (40 per scenario). After data cleaning, which excluded respondents failing the manipulation check or reporting no CBEC shopping experience, 274 valid responses were retained, yielding an effective response rate of 85.6%. According to Krejcie and Morgan [

55], their sample size determination formula indicates that a sample of approximately 384 is required for large populations. In addition, SEM literature generally recommends a sample size between 200 and 400 to ensure robust estimation and model stability [

56,

57].

4.3. Measures

Perceived risk and purchase intention were operationalized using established scales adapted to the CBEC cosmetics context. All constructs were assessed on seven-point Likert-type scales, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”. The measurement items were adapted from validated scales in prior studies. A pilot test with 30 respondents confirmed reliability (Cronbach’s α > 0.80) and item clarity.

Table 2.

Measurement items, conceptual definitions, and literature sources.

Table 2.

Measurement items, conceptual definitions, and literature sources.

| Code |

Item Statement |

Conceptual Meaning |

Source |

| PR1 |

Purchasing this imported cosmetic product on this CBEC platform involves significant risk. |

Significant perceived risk |

[58]; |

| PR2 |

I am concerned that this purchase may result in a negative outcome. |

Concern about negative consequences |

[58] |

| PR3 |

There is a high chance I could lose money or receive a counterfeit product. |

High potential for loss |

[59] |

| PI1 |

I am likely to purchase this cosmetic product on the cross-border e-commerce platform. |

Likelihood to purchase |

[60] |

| PI2 |

I would consider buying this product at the presented price. |

Consideration at given price |

[61] |

| PI3 |

The probability that I would buy this imported cosmetic product is high. |

Purchase probability |

[61] |

Perceived risk was defined as consumers’ subjective evaluation of uncertainty, authenticity, and potential financial loss in CBEC cosmetics purchases. Purchase intention was defined as consumers’ likelihood and willingness to purchase the presented product.

4.4. Data Collection

An online questionnaire that aligned with the experimental tasks helped capture the data. Participants were given one of the eight scenarios at random and were given a page of a product for their consideration for 45 seconds. Subsequently, the participants completed a questionnaire, which was randomized in order to reduce order effects. Manipulation checks were used to assess recognition of the four signals. Respondents who misidentified more than one signal were eliminated, as well as those who were unsure.

Of 320 completed responses, 274 were considered valid after the data cleaning process. The remaining sample size fulfilled the statistical power and SEM requirements, which confirmed the strength of the analysis. All processes followed ethical requirements set by the institutions and received clearance from the university’s ethics committee. In addition, participants were provided with an informed consent document that detailed their ability to withdraw from participation at any stage without incurring any negative consequences. In addition, participants were assured that their identities would not be collected, which would ensure their anonymity and confidentiality.

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Bias

We first tested whether a single shared method could account for the covariation among indicators. A one-factor CFA did not adequately fit the data (χ2 (104) = 445.216, RMSEA = 0.109, CFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.925, SRMR = 0.039), whereas separating indicators into perceived risk and purchase intention yielded excellent fit (χ2 (13) = 21.290, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.992, SRMR = 0.018). The difference test strongly preferred the two-factor solution (Δχ2 (91) = 423.926, p < 0.001); thus, material CMB is unlikely.

Table 3.

Common method bias test results.

Table 3.

Common method bias test results.

| Model Type |

χ2 (df) |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

CFI |

TLI |

Δχ2 (Δdf) |

| One-factor model |

445.216 (104), p < .001 |

0.109 |

0.039 |

0.935 |

0.925 |

Baseline |

| Two-factor model |

21.290 (13), p = 0.067 |

0.048 |

0.018 |

0.995 |

0.992 |

Δχ2(91) = 423.926, p < .001 |

5.2. Descriptive Statistics

Of the 320 questionnaires distributed, 302 valid responses were collected (response rate = 94.4%). After excluding participants who failed the signal recognition check or lacked CBEC shopping experience, 274 valid responses remained for analysis, yielding an effective rate of 85.6%. All respondents were female, aged 26–30, and had prior CBEC shopping experience, which aligns with the study’s targeted demographic group. Regarding monthly income, most participants reported earnings between CNY 4000 and 7999 (72.2%), and more than 60% indicated purchasing imported cosmetics at least 7 times per year. These characteristics confirm that the sample represents the primary consumer group of interest in China’s CBEC cosmetics sector.

Table 4.

Sample characteristics (N = 274).

Table 4.

Sample characteristics (N = 274).

| Variable |

Categories |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| Monthly Income (CNY) |

4000–5999 |

102 |

37.2 |

| |

6000–7999 |

96 |

35.0 |

| |

8000–9999 |

52 |

19.0 |

| |

≥10,000 |

24 |

8.8 |

| Annual Cosmetics Purchases |

1–2 times |

28 |

10.2 |

| |

3–6 times |

74 |

27.0 |

| |

7–12 times |

108 |

39.4 |

| |

>12 |

64 |

23.4 |

5.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

We first asked whether the indicators adequately capture their latent constructs (measurement) before testing relations among constructs (structural) [

62]. Following established guidelines, we first assessed the measurement model before proceeding to the structural analysis [

63,

64]. This evaluation included composite reliability, examinations of convergent and discriminant validity, and a review of overall model fit indices.

5.3.1. Composite Reliability and Convergent Validity

To evaluate the adequacy of the measurement model, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in Mplus (Version 8.3) using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. Reliability was examined through Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), while convergent validity was assessed by inspecting standardized factor loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE). This multi-criteria assessment ensured that the constructs demonstrated both internal consistency and convergent validity, thereby meeting the prerequisites for subsequent structural equation modeling (SEM).

Following widely accepted benchmarks, standardized factor loadings should ideally be

≥ 0.70 [

63], though values

≥ 0.50 are considered acceptable in exploratory contexts [

65]. Cronbach’s α values

≥ 0.70 are typically regarded as the minimum threshold for adequate reliability [

66]. Similarly, composite reliability (CR) values

≥ 0.70 indicate satisfactory internal consistency [

62], while an AVE

≥ 0.50 suggests that the construct captures more than half of the variance of its observed indicators [

67]. These criteria are frequently cited in the SEM literature and provide the foundation for judging measurement model adequacy [

64,

68].

Table 5 reports standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.851 to 0.939, all above the commonly suggested cut-off. Both constructs achieved Cronbach’s alpha values higher than 0.90, with composite reliability (CR) also surpassing 0.90 and average variance extracted (AVE) above 0.80. Taken together, these indicators provide strong evidence that the measurement scales demonstrate high internal consistency, robust reliability, and satisfactory convergent validity.

As reported in

Table 5, the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.851 to 0.939, which are well above the recommended cut-off, providing strong support for item reliability. Both constructs achieved Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.90, reflecting excellent internal consistency. Composite reliability (CR) values also exceeded 0.90, further confirming the robustness of the scales. In addition, the AVE values were all above 0.80, clearly surpassing the 0.50 benchmark and demonstrating that the constructs explain the majority of the variance in their respective indicators.

Taken together, these results provide compelling evidence that the measurement scales demonstrate high internal consistency, robust reliability, and satisfactory convergent validity. The consistently strong performance across all metrics aligns with the recommended thresholds in prior methodological studies [

67,

68], thereby confirming that the constructs are well-specified and suitable for subsequent structural modeling.

5.3.2. Discriminant Validity

We define discriminant validity as the degree to which constructs within a model remain conceptually and empirically distinct [

68] To assess this property, we employed two established techniques.. First, following the Fornell–Larcker criterion, we compared the square root of each construct’s average variance extracted (AVE) with its correlations with other constructs [

69]. As reported in

Table 6, the AVE square roots for Perceived Risk (0.906) and Purchase Intention (0.928) were both higher than their inter-construct correlation (−0.775), thereby confirming discriminant validity.

Second, we used the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) [

70]. The HTMT value between Perceived Risk and Purchase Intention was 0.834, which is lower than the conservative threshold of 0.85 [

71,

72]. To ensure completeness, we also examined collinearity statistics, which showed no multicollinearity (Tolerance > 0.10; VIF < 5).

Table 6.

Discriminant validity.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity.

| Construct |

CR |

AVE |

Perceived Risk |

Purchase Intention |

| Perceived Risk |

0.935 |

0.821 |

0.906 |

−0.775 |

| Purchase Intention |

0.923 |

0.861 |

−0.775 |

0.928 |

Table 7.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio.

Table 7.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio.

| Construct pair |

HTMT |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| Perceived Risk ↔ Purchase Intention |

0.834 |

0.658 |

1.519 |

5.3.3. Model Fit Indices

The adequacy of the overall measurement model was further examined through a set of widely recognized fit indices, using Mplus (Version 8.3) with data from 274 valid responses. Evaluating multiple indices rather than a single statistic is essential, as each provides complementary insights into how well the model reproduces the observed covariance matrix [

73].

The chi-square (χ

2) statistic is the most traditional indicator of model fit, though it is known to be highly sensitive to sample size. For this reason, researchers typically report the χ

2/df ratio instead of relying solely on the raw χ

2 value. A ratio of less than 3 is generally taken as evidence of good fit, while values under 5 may still be considered acceptable in large-sample contexts [

73].

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) evaluates the improvement of the hypothesized model relative to a null model where all variables are assumed to be uncorrelated. CFI values above 0.90 are usually interpreted as acceptable, with values greater than 0.95 indicating an excellent fit. Alongside this, the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), sometimes referred to as the Non-Normed Fit Index, adjusts for model complexity and the number of estimated parameters. Like the CFI, TLI values above 0.90 represent adequate fit, and values beyond 0.95 reflect a very good model specification.

The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) provides an absolute measure of approximate fit by penalizing model complexity and taking sample size into account. RMSEA values below 0.05 are indicative of a close fit, values between 0.05 and 0.08 reflect reasonable error of approximation, and values greater than 0.10 suggest poor model fit [

74].

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) complements the above indices by capturing the standardized difference between the observed and predicted correlations. Because it is based on residuals, the SRMR is particularly useful for detecting localized areas of misfit. Values below 0.08 are generally considered acceptable [

75].

As presented in

Table 8, the proposed model satisfied all recommended benchmarks: χ

2 = 97.044, χ

2/df = 2.488, CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.074, and SRMR = 0.057. Collectively, these indices demonstrate that the measurement model provides an adequate to excellent fit with the observed data. This confirmation of model adequacy establishes a strong empirical basis for proceeding with the structural equation modeling and hypothesis testing.

5.4. Structural Model Analysis

5.4.1. Direct Effects

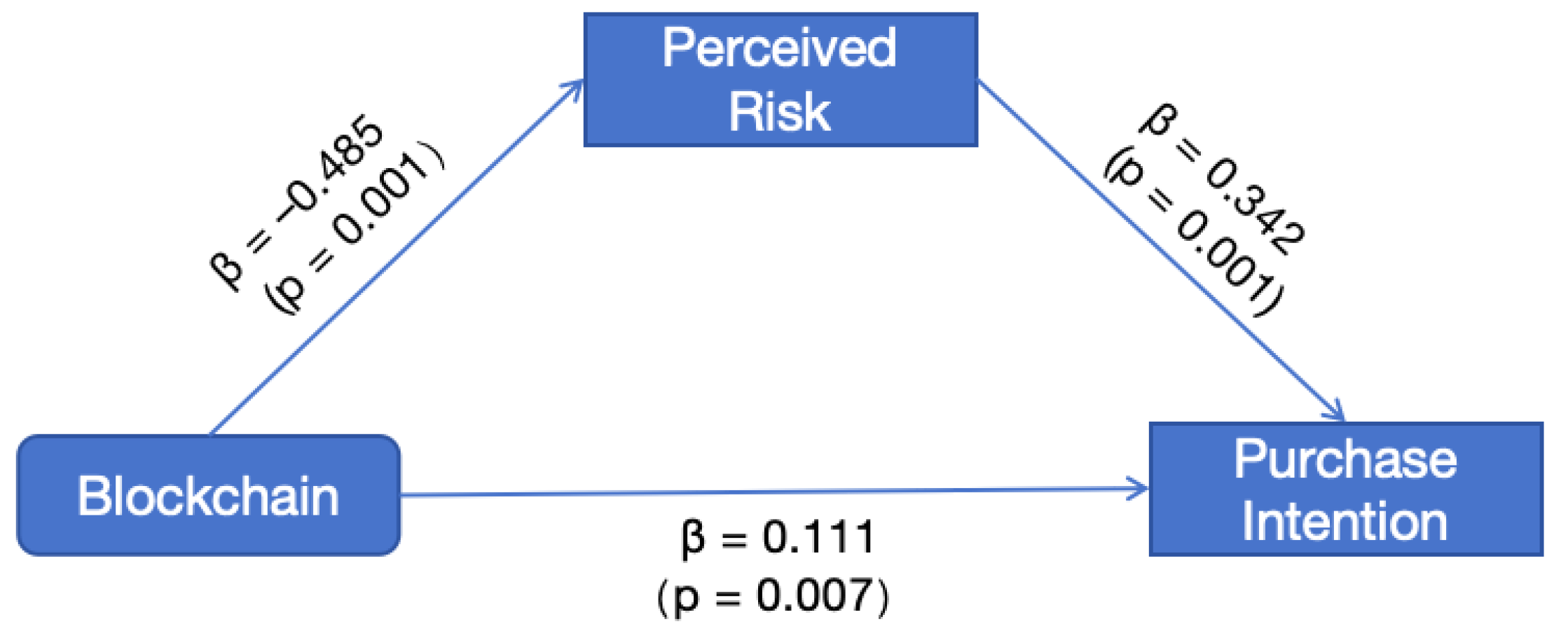

Table 8 summarizes the SEM path analysis, which shows that the associations between authenticity signals and purchase intention differ across types. Specifically, blockchain traceability had a positive and significant influence on purchase intention (β = 0.111, p = 0.007), indicating that technology-driven transparency mechanisms can increase consumers’ willingness to buy in CBEC cosmetics.

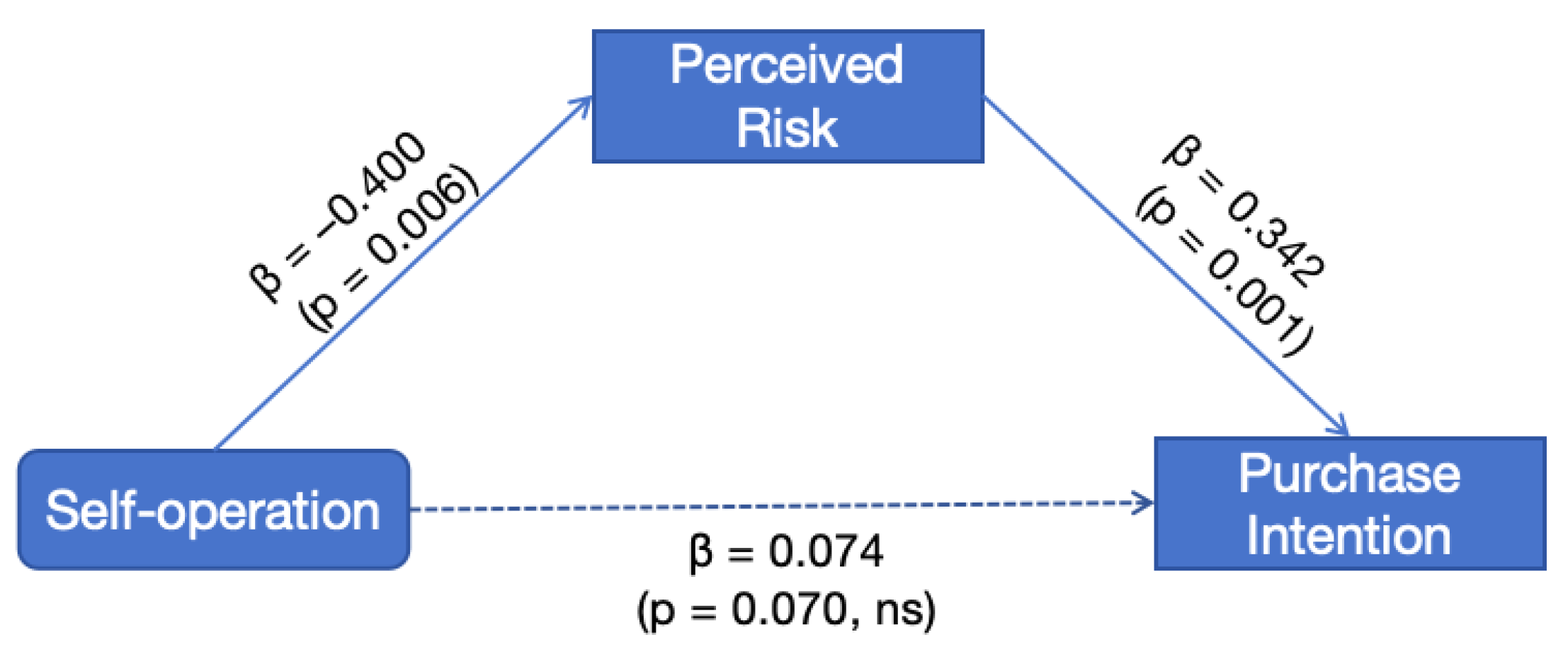

By contrast, the effect of platform self-operation on purchase intention was not statistically significant (β = 0.074, p = 0.070). Although self-operation signals may provide institutional assurance, their direct influence on consumers’ purchase decisions was not evident in this study.

Likewise, customer reviews did not produce a significant direct impact on purchase intention (β = 0.022, p = 0.594). This suggests that while reviews can serve as social proof in many e-commerce settings, their effectiveness in CBEC cosmetics may be weakened by concerns about review authenticity.

Compensation guarantees likewise showed no significant influence on purchase intention (β = 0.036, p = 0.405). Although such guarantees represent institutional mechanisms of risk transfer, their presence alone does not appear sufficient to directly motivate consumer purchase behavior in this context.

5.4.2. Mediation Effect Testing

Based on the conceptual framework, perceived risk was tested as a mediating variable linking authenticity signals to purchase intention. Following established procedures [

76,

77], direct, indirect, and total effects were examined. Indirect effects were estimated as the product of the path coefficients (a × b) from authenticity signals to purchase intention via perceived risk. To improve estimation accuracy, the bootstrap resampling method (5000 iterations) was employed to generate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. A confidence interval excluding zero indicated a statistically significant mediation effect [

78,

79].

As presented in

Table 9, blockchain traceability exhibited a significant indirect effect on purchase intention through perceived risk (β = 0.166, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.204, 0.805]), supporting H3a. This indicates that blockchain enhances purchase intention primarily by lowering consumer risk perceptions.

Platform self-operation also demonstrated a significant mediating pathway (β = 0.138, p = 0.006, 95% CI [0.126, 0.699]), lending support to H3b. This suggests that institutional assurances reduce consumer uncertainty, which subsequently promotes purchase intention.

By contrast, customer reviews did not show a statistically significant mediation effect (β = 0.067, p = 0.213, 95% CI [−0.123, 0.525]), failing to support H3c. The result reflects growing consumer skepticism regarding review authenticity in CBEC contexts.

Finally, compensation guarantees revealed a significant indirect effect on purchase intention (β = 0.156, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.175, 0.767]), confirming H3d. This finding highlights that explicit institutional commitments to bear risk can effectively reduce perceived risk and increase consumer purchase intention.

Table 10.

Mediation test results: perceived risk as a mediator between authenticity signals and purchase intention.

Table 10.

Mediation test results: perceived risk as a mediator between authenticity signals and purchase intention.

| Hypothesis |

Indirect Path |

β (StdYX) |

UnStd. |

S.E. |

Z |

p-Value |

95% CI LL |

95% CI UL |

Result |

| H2a |

Blockchain → Risk → PI |

0.166 |

0.485 |

0.152 |

3.192 |

0.001 |

0.204 |

0.805 |

Supported |

| H2b |

Self-operation → Risk → PI |

0.138 |

0.400 |

0.145 |

2.755 |

0.006 |

0.126 |

0.699 |

Supported |

| H2c |

Review → Risk → PI |

0.067 |

0.204 |

0.164 |

1.245 |

0.213 |

-0.123 |

0.525 |

Not supported |

| H2d |

Compensation → Risk → PI |

0.156 |

0.454 |

0.151 |

3.007 |

0.003 |

0.175 |

0.767 |

Supported |

Perceived risk was examined as a mediating variable linking authenticity signals to purchase intention. Direct, indirect, and total effects were calculated following established procedures [

76,

77]. Indirect effects were computed as the product of the path coefficients (a × b), and significance was assessed using 5000 bootstrap resamples with bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals excluding zero indicated a statistically significant mediation effect [

78,

79].

Blockchain Traceability.

The indirect effect of blockchain on purchase intention through perceived risk was significant (β = 0.166, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.204, 0.805]). This confirms that blockchain reduces perceived risk, which in turn enhances purchase intention. Given the significant indirect effect alongside its positive direct effect, the results indicate

partial mediation, supporting H3a. The final model for blockchain traceability is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Self-operation also demonstrated a significant indirect pathway via perceived risk (β = 0.138, p = 0.006, 95% CI [0.126, 0.699]). The presence of both direct and indirect effects indicates

partial mediation, supporting H3b. This finding highlights that platform-backed operational assurances reduce risk perceptions and indirectly foster purchase intention. The final model for platform self-operation is presented in

Figure 4.

By contrast, customer reviews did not show a significant mediation effect through perceived risk (β = 0.067, p = 0.213, 95% CI [−0.123, 0.525]). The confidence interval including zero indicates a non-significant result, failing to support H3c. This suggests that in CBEC cosmetics, consumer skepticism about review authenticity weakens their risk-reducing role. The final model for customer reviews is shown in

Figure 5.

Compensation commitments yielded a significant indirect effect on purchase intention through perceived risk (β = 0.156, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.175, 0.767]). The results confirm

partial mediation, supporting H3d, and highlight the importance of institutional assurances in mitigating risk and increasing consumer confidence. The final model for compensation guarantee is displayed in

Figure 6.

5.4.3. Moderation Analysis: Boundary Conditions of Blockchain Effectiveness

To further test the boundary conditions of blockchain’s effectiveness, moderation analyses were conducted with platform self-operation, customer reviews, and compensation guarantees as moderators. The conditional indirect effects are reported in

Table 11, and the corresponding visualizations are presented in

Figure 7.

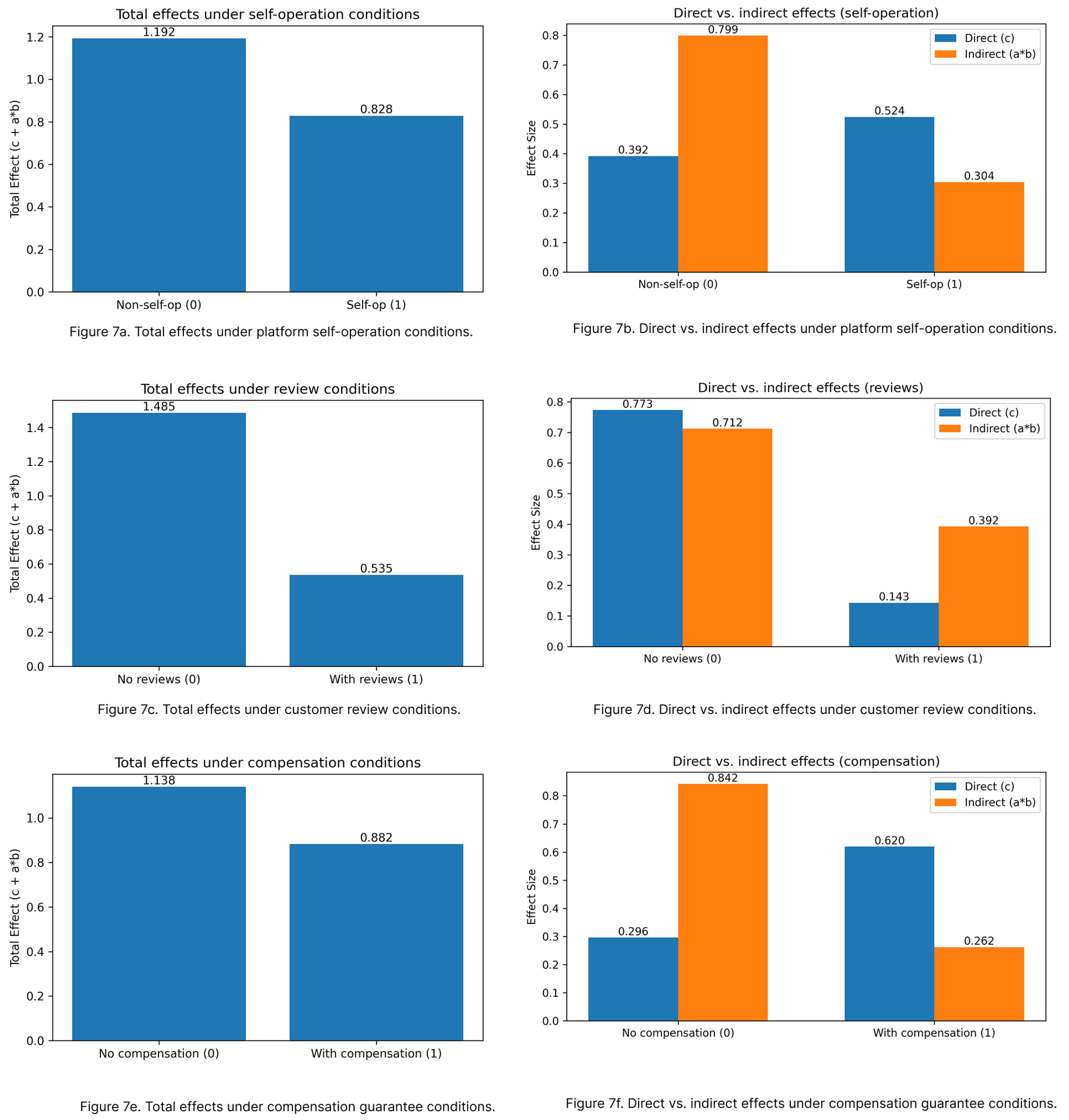

(a) H4a: Self-operation

As shown in

Table 11, blockchain exerted a stronger impact on non-self-operated platforms, significantly reducing risk (a = –0.885, p < .001) and enhancing purchase intention (total effect = 1.192, p < .001). On self-operated platforms, the effect was weaker, retaining only a partial direct pathway (c = 0.524, p < .05). These differences are further illustrated in

Figure 7a,b, which present the total and decomposed effects, respectively.

(b) H4b: Reviews

Table 11 also shows that in the absence of positive reviews, blockchain played a critical role in reducing risk and increasing purchase intention (total effect = 1.485, p < .001). However, when reviews were present, the marginal contribution of blockchain decreased and the total effect was substantially reduced (0.535, p < .05). The patterns are visualized in

Figure 7c,d, highlighting the diminished effect under review-rich conditions.

(c) H4c: Compensation

Similarly, blockchain demonstrated the strongest influence when no compensation guarantee was provided (total effect = 1.138, p < .001). With a “counterfeit compensation” commitment, blockchain’s effect weakened, leaving only a partial direct pathway (total effect = 0.882, p < .01). These findings are illustrated in

Figure 7e,f.

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

This research aimed to examine how the four authenticity signals of blockchain traceability, self-operated platforms, customer reviews, and compensation commitments influence purchase intention within the CBEC Cosmetics industry, while perceived risk is the potential mediating factor.

First, purchase intention is significantly influenced by blockchain traceability (β = 0.111, p < .01), which lends support to H1a. However, no significant direct effects were established for self-operated platforms, customer reviews, and compensation guarantees (H1b, H1c, H1d).

Second, perceived risk is significantly diminished by blockchain self-operation and compensation guarantees, while customer reviews have no effect. Third, mediation analyses demonstrated that perceived risk was the mediating factor for the effects of purchase intention for blockchain self-operation and compensation guarantees. Notably, purchase intention is influenced by blockchain traceability through direct and indirect pathways. This highlights its role as a signaling mechanism.

Lastly, the moderation analysis showed that the efficacy of blockchain depends on the situation. In low-trust settings, such as non-self-operated platforms, without user reviews, and without reimbursement assurances, its influence was greatest (total effect = 1.192, 1.485, and 1.138; all p < .001). While some direct impacts remained large, blockchain traceability’s marginal contribution diminished in the presence of traditional assurance measures. All things considered, our results show that blockchain traceability is an effective authenticity indicator in CBEC. It serves as both a technological mechanism and a tool for fostering trust, and its impact is greatest in situations when trust is lacking.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

These findings extend signaling theory in several ways. First, they demonstrate that not all authenticity signals operate through the same mechanisms. Blockchain functions as both a direct and indirect signal, whereas self-operation and compensation guarantees work indirectly by lowering risk perceptions. This diverges from earlier literature that typically regarded signals as uniformly indirect mechanisms for reducing uncertainty [

53]. In addition, our results suggest that signaling theory can be enriched by incorporating insights from transaction cost economics. By reducing monitoring and verification costs, blockchain may serve not only as a signal but also as an institutional mechanism that lowers the overall cost of market exchange. This dual role highlights the need to expand the boundary of signaling theory from purely communicative functions to include efficiency-enhancing roles in digital markets.

Second, the results highlight the centrality of perceived risk as a mediating mechanism in CBEC. While prior studies emphasized perceived quality or trust [

29].Our findings show that in high-risk categories such as cosmetics, reducing risk is a more immediate determinant of purchase intention. In particular, our results differ from Treiblmaier and Garaus [

29], who reported a full mediation model in the food supply chain: blockchain enhanced purchase intention only indirectly through perceived quality, with no significant direct effect. By contrast, our study identifies a partial mediation structure in CBEC cosmetics, where blockchain not only reduces perceived risk to indirectly increase purchase intention but also exerts a direct effect. This contrast underscores the importance of product category context: in food, consumers prioritize quality assurance, whereas in cosmetics, concerns about counterfeits and product safety render risk reduction the dominant pathway. Further extending this logic, in luxury goods, blockchain may act as a credibility enhancer tied to exclusivity, while in pharmaceuticals it may function as a safeguard against life-threatening risks. This product-specific heterogeneity demonstrates that signaling theory must be contextualized within category-specific consumer priorities, which opens new avenues for comparative studies across industries.

Third, the insignificance of customer reviews raises theoretical questions about the erosion of UGC as a trust signal. Whereas earlier work identified reviews as strong predictors of purchase behavior [

14,

41]. Our findings suggest that their signaling value may be contextually limited in cross-border settings, where skepticism regarding authenticity is high. This points to the possibility of a broader theoretical shift: signals originating from consumers (UGC) may be losing their relative strength compared with institutionally validated signals such as blockchain. In an era where fake reviews and manipulated ratings are pervasive, authenticity signals backed by technological or contractual enforcement may become the dominant drivers of trust. Future signaling theory research should therefore consider the dynamic evolution of signal credibility, recognizing that the effectiveness of signals may change over time depending on technological, institutional, and cultural developments.

Finally, the moderation results contribute to signaling theory by revealing substitution effects between blockchain and traditional signals. When institutional (self-operation), contractual (compensation), or social (reviews) assurances are absent, blockchain operates as a “safeguard signal,” compensating for the lack of alternative credibility cues. Conversely, when these signals are present, blockchain’s marginal impact declines, consistent with Spence’s [

31] proposition that the value of a signal depends on the existing signaling environment. This highlights the importance of studying signal interactions rather than treating signals as isolated factors. Overall, our study refines signaling theory by showing both the heterogeneity and interdependence of authenticity signals in CBEC. Beyond CBEC, this suggests a broader implication: signaling environments are not static but relational, where the value of one signal is contingent on the presence and credibility of others. Integrating insights from institutional theory, one could argue that the legitimacy of blockchain as a signal is co-constructed with institutional endorsements and market norms. Thus, signaling theory should evolve toward a more systemic perspective that accounts for interdependencies across multiple institutional and technological signals.

6.3. Managerial Implications

For practitioners, several insights emerge from this study.First, blockchain traceability should be prioritized as a high-impact authenticity mechanism, particularly in low-trust environments. By integrating supply chain data and QR code verification, CBEC platforms can provide consumers with tamper-proof assurance, directly enhancing purchase confidence. Managers in other sensitive industries—such as pharmaceuticals, infant formula, and luxury fashion—can also draw lessons from this finding, as these categories face similar counterfeit risks. By adapting blockchain traceability to their specific contexts, firms can address consumer anxieties and create differentiated value propositions.

Second, platform self-operation and compensation guarantees remain valuable but act mainly as risk-reduction tools. Managers should treat them as complementary to blockchain rather than as stand-alone signals. For instance, blockchain is particularly critical for third-party sellers or when platforms cannot guarantee quality control. In practice, hybrid models combining contractual assurances with blockchain-based verification may be most effective. For example, Amazon’s “A-to-Z Guarantee” shows how compensation policies can enhance trust, but coupling such guarantees with blockchain-verified product data would further strengthen credibility. This hybrid approach can help platforms strike a balance between cost efficiency and consumer trust.

Third, platforms should reconsider their reliance on customer reviews. Without credible authentication, reviews no longer reduce risk. Innovations such as blockchain-verified reviews or AI-based detection systems could help restore their signaling effectiveness. Managers should also consider designing consumer education campaigns that highlight the differences between verified and unverified reviews, thereby empowering consumers to make more informed judgments. By actively shaping the information environment, platforms can reposition reviews as a supportive, rather than primary, signal.

Fourth, the moderation results suggest that signal strategies must be context-specific. Blockchain investment yields the greatest returns in situations where traditional credibility mechanisms are weak or absent (e.g., third-party sellers without guarantees). In contrast, when multiple assurance signals already exist, blockchain should be framed as an enhancing signal rather than the primary driver of trust. This implies that resource allocation decisions should be context-driven: platforms with strong brand reputations may focus less on blockchain, while emerging players or third-party marketplaces should make blockchain central to their trust-building strategies. Managers therefore need to evaluate not only the absolute value of signals but also their marginal contributions given the existing signaling environment.

Fifth, platform-level practices provide further illustration. For example, Tmall Global often combines blockchain with its self-operation channel, highlighting blockchain’s role as a core signal when both self-owned and third-party sellers coexist. JD Worldwide, by contrast, relies less on blockchain due to its strong reputation and logistics system, showing that blockchain functions more as an enhancing signal. Pinduoduo Global, which emphasizes compensation commitments rather than blockchain, demonstrates how different platforms rely on different trust mechanisms depending on brand image and market positioning. These comparisons reinforce the notion that authenticity signals are not universal substitutes but must be strategically matched to platform credibility and consumer expectations. This also highlights the managerial importance of competitive benchmarking: platforms should continuously monitor how rivals deploy different combinations of signals and adjust their own strategies to maintain competitive advantage.Finally, our divergence from [

29] further suggests that the way blockchain is presented matters. Their study, focusing on food products, found that QR-code-only designs directly enhanced purchase intentions, especially when brand familiarity was low. By contrast, our QR code + textual explanation format produced weaker direct effects in cosmetics, indicating that consumers may respond differently depending on the signal form and product category. For managers, this implies that blockchain’s effectiveness can be maximized only when its presentation is simple, interactive, and aligned with consumer priorities. Future applications may explore gamification, immersive visualization, or integration into mobile shopping apps to increase consumer engagement. Additionally, regulators and industry associations should encourage the adoption of standardized blockchain traceability protocols across CBEC platforms, as harmonization can reduce consumer confusion and increase sector-wide trust.

In summary, for emerging or less-known brands, blockchain-based traceability can serve as a credibility-building tool to compete with established players. For regulators and industry associations, encouraging the adoption of blockchain standards in CBEC could help institutionalize authenticity assurance, thereby improving consumer trust in the sector as a whole. Ultimately, managerial strategies should not treat blockchain as a universal solution but as part of a portfolio of authenticity signals that must be tailored to specific contexts, product categories, and consumer expectations.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has limitations that open avenues for further inquiry. First, the sample was restricted to female consumers aged 26–30 with CBEC shopping experience, limiting generalizability. Future research should test more diverse demographics and cross-cultural samples. Second, the study relied on experimental scenarios and self-reported purchase intentions. Field experiments or transaction-level data could provide stronger evidence of real consumer behavior. Third, although four major signals were examined, other factors such as brand reputation, third-party certifications, or logistics performance were not included. Future studies could explore interactions between blockchain and these alternative signals. Finally, the moderation findings highlight the need for further exploration of signal substitution and complementarity. Future research could adopt multi-group analysis to examine whether blockchain’s role differs across platform types, product categories, or cultural contexts. Longitudinal designs may also clarify whether the erosion of review credibility is temporary or structural.

7. Conclusion

This study investigates how four authenticity signals—blockchain traceability, platform self-operation, customer reviews, and compensation commitments—shape purchase intention in CBEC cosmetics, with perceived risk as a mediating mechanism and traditional signals as contextual moderators. The results show that blockchain is the only signal with a significant direct impact on purchase intention and also exerts an indirect effect via perceived risk. By contrast, platform self-operation and compensation commitments influence purchase intention indirectly through reducing perceived risk, while customer reviews show limited effectiveness in this high-risk category.

Moderation analyses further reveal that blockchain’s effectiveness is context-dependent. Its impact is strongest when institutional and social assurances are weak or absent (e.g., non-self-operated platforms, no reviews, no compensation guarantees), but its marginal contribution declines when such traditional assurances are already in place. This pattern points to substitution rather than simple complementarity among signals.

Theoretically, these findings refine signaling theory by demonstrating the heterogeneity of authenticity signals (direct vs. indirect pathways), establishing perceived risk as a central mediator in CBEC cosmetics, and highlighting that a signal’s value depends on the broader signaling environment. Practically, managers should treat blockchain as the anchor of authenticity strategies in low-trust settings, but position it as an enhancing (not primary) signal when strong institutional safeguards already exist. Platforms should also invest in simple, interactive blockchain presentations and explore mechanisms to restore the credibility of reviews (e.g., verification and detection technologies).

While limitations relating to sample composition and experimental design remain, they open avenues for future work using more diverse populations, field or transactional data, and additional signals (e.g., brand reputation, third-party certifications). Longitudinal designs can also assess whether the waning signaling value of reviews is temporary or structural across product categories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiaoling Liu; methodology, Xiaoling Liu; formal analysis, Xiaoling Liu; investigation, Xiaoling Liu; data curation, Xiaoling Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaoling Liu; writing—review and editing, Ahmad Yahya Dawod; supervision, Ahmad Yahya Dawod. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare

References

- World Trade Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Digital Trade 2023. Geneva: WTO & OECD; 2023.

- People’s Daily Online. China’s cross-border e-commerce imports and exports hit 2.38 trillion yuan in 2023 [Internet]. 2024. Available from: http://en.people.cn/n3/2024/0124/c90000-20126122.html.

- Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute. The Expansion of Cross-border E-commerce in China [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.mitsui.com/mgssi/en/report/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2021/12/22/2111c_takahashi_e.pdf.

- Giuffrida, M.; Jiang, H.; Mangiaracina, R. Investigating the relationships between uncertainty types and risk management strategies in cross-border e-commerce logistics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 1406–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yeon, C. Blockchain-Based Traceability for Anti-Counterfeit in Cross-Border E-Commerce Transactions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phamthi, V.A.; Nagy, Á.; Ngo, T.M. The influence of perceived risk on purchase intention in e-commerce—Systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S. The influence of consumer perception on purchase intention: Evidence from cross-border E-commerce platforms. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.M.; Shi, B. Consumer patronage and risk perceptions in Internet shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Oliveira, T.; Popovič, A. Understanding the Internet banking adoption: A unified theory of acceptance and use of technology and perceived risk application. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Pertheban TR. Exploring the Factors Affecting Consumer Trust in Cross-Border E-Commerce: A Comparative Study. Acad J Bus Manag. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Liu H. The effect of guarantee mechanisms on consumer trust in cross-border e-commerce. J Retail Consum Serv. 2021, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier JA, Mayzlin D. The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. J Mark Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y, Yoo J. The effects of eWOM volume and valence on consumer decision-making: The moderating role of brand familiarity. Asia Pac J Mark Logist. 2021, 33, 1331–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, M. Reviews, reputation, and revenue: The case of Yelp.com. 2016. (Harvard Business School NOM Unit Working).

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Tractinsky, N.; Saarinen, L. Consumer Trust in an Internet Store: A Cross-Cultural Validation. J. Comput. Commun. 2006, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M. The Impact of Blockchain Technology on E-commerce Product Development: Case Studies of Walmart and LVMH. Adv. Econ. Manag. Politi- Sci. 2024, 109, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore M, Tseng ML, Chiu ASF. Blockchain applications in supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2023, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Hastig, G.M.; Sodhi, M.S. Blockchain for Supply Chain Traceability: Business Requirements and Critical Success Factors. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2019, 29, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Fonts, A.; Prenafeta-Boldύ, F.X. The rise of blockchain technology in agriculture and food supply chains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Ngo, T.V.N.; Thanh, T.D.; Tran, N.M. Blockchain technology and consumers’ organic food consumption: a moderated mediation model of blockchain-based trust and perceived blockchain-related information transparency. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2024, 19, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun H, Zhang J, Zhao X. The role of blockchain in combating counterfeit luxury products. Decis Sci. 2021, 52, 1069–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Rejeb A, Keogh JG, Treiblmaier H, Rejeb K. Blockchain technology in the food industry: A review of potentials and challenges. Int J Prod Res. 2020, 58, 2142–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Treiblmaier, H. Toward More Rigorous Blockchain Research: Recommendations for Writing Blockchain Case Studies. Front. Blockchain 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Liu, R.; Shan, Z. Is Blockchain a Silver Bullet for Supply Chain Management? Technical Challenges and Research Opportunities. Decis. Sci. 2019, 51, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Peterson, R.A. A Meta-analysis of Online Trust Relationships in E-commerce. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouthuysen, K.; Teunis, I.; Reusen, E.; Slabbinck, H. Initial trust and intentions to buy: The effect of vendor-specific guarantees, customer reviews and the role of online shopping experience☆. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 27, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou; Liang; Xue Understanding and Mitigating Uncertainty in Online Exchange Relationships: A Principal-Agent Perspective. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 105. [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H.; Garaus, M. Using blockchain to signal quality in the food supply chain: The impact on consumer purchase intentions and the moderating effect of brand familiarity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Deng, Z.; Guo, J.; Abbas, A.F. The effects of external cues on cross-border e-commerce product sales: An application of the elaboration likelihood model. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0293462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. Q J Econ. 1973, 87, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2010, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H. Toward More Rigorous Blockchain Research: Recommendations for Writing Blockchain Case Studies. Front. Blockchain 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim RB, Yan C. Effects of Brand Experience, Brand Image and Brand Trust on Brand Building Process: the Case of Chinese Millennial Generation Consumers. J Int Stud. 2019, 12, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kurnia, P.; Lepar, P.S.; Sitio, R.P. Marketing Communication Tools, Emotional Connection, and Brand Choice: Evidence from Healthy Food Industry. Int. J. Digit. Entrep. Bus. 2023, 4, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L.; Guèvremont, A.; Girardin, F.; Grohmann, B. Brand authenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 25, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Liapati, G.; Kouletsis, G.; Koniordos, M. The impact of brand authenticity on brand attachment in the food industry. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer FR, Schurr PH, Oh S. Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships. J Mark. 1987, 51, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Tractinsky, N.; Saarinen, L. Consumer Trust in an Internet Store: A Cross-Cultural Validation. J. Comput. Commun. 2006, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, N. Dynamic Pricing with Money-Back Guarantees. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 31, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, A.R.; Alversia, Y. The Influence of Online Review on Consumers’ Purchase Intention. GATR J. Manag. Mark. Rev. 2019, 4, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, U. The Effect of Online Review on Online Purchase Intention. Res. A Res. J. Cult. Soc. 2021, 5, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chod, J.; Trichakis, N.; Tsoukalas, G.; Aspegren, H.; Weber, M. On the Financing Benefits of Supply Chain Transparency and Blockchain Adoption. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 4378–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimun; Sufyan The Role of Blockchain Technology in Securing Supply Chain Information Systems. J. Informatic, Educ. Manag. (JIEM) 2024, 6, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Dann D, Peukert C, Martin C, Weinhardt C, Hawlitschek F. Blockchain and Trust in the Platform Economy: The Case of Peer-to-Peer Sharing. 2020; 1459–1473.

- Yavaprabhas K, Pournader M, Seuring S. Blockchain as the “Trust-Building Machine” for Supply Chain Management. Ann Oper Res. 2022, 327, 49–88. [Google Scholar]

- Boissieu E, d. , Kondrateva G, Baudier P, Ammi C. The Use of Blockchain in the Luxury Industry: Supply Chains and the Traceability of Goods. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2021, 34, 1318–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Duan, Y.; Sarkis, J. Supply chain carbon transparency to consumers via blockchain: does the truth hurt? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 35, 833–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhu, Q. Blockchain empowerment: enhancing consumer trust and outreach through supply chain transparency. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 63, 5358–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yao, A.; Li, W.; Wei, Q. Blockchain technology empowers the cross-border dual-channel supply chain: Introduction strategy, tax differences, optimal decisions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, M.; Zhong, F. How retailers can gain more profitability driven by digital technology: Live streaming promotion and blockchain technology traceability? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S. Purchasing in the digital age: A meta-analytical perspective on trust, risk, security, and e-WOM in e-commerce. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2010, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V. Consumer perceived risk: conceptualisations and models. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. Nonconvergence, Improper Solutions, and Starting Values in Lisrel Maximum Likelihood Estimation. Psychometrika 1985, 50, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2011.

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer Acceptance of Electronic Commerce: Integrating Trust and Risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer Acceptance of Electronic Commerce: Integrating Trust and Risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlanova, T.; Benbunan-Fich, R.; Lang, G. The role of external and internal signals in E-commerce. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 87, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Krishnan, R.; Baker, J.; Borin, N. The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on consumers' evaluations and purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate Data Analysis. 8th ed. Cengage Learning; 2019.

- Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J Mark Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, JC. Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J Mark Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Balla, J.R.; Grayson, D. Is More Ever Too Much? The Number of Indicators per Factor in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1998, 33, 181–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: a comparison of four procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]