1. Introduction

Choosing a career path is one of the most significant decisions a student may face. For young women, especially from low socioeconomic or marginalised backgrounds, this pathway often feels like a solitary passage navigating through turbulent waters. While vivid dreams accompany this journey, it is also loomed over by social expectations and systemic bias. To assist her, we propose SAIL-Y, a recommender system designed to support female students by guiding them towards more fruitful interdisciplinary connections within the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and attributing socioeconomic sensitivity to the recommendations.

Educational counselling utilising learning analytics and artificial intelligence has seen considerable adoption; however, most recommender systems seem to omit the long-standing gender inequalities in career paths. The shortcomings of SAIL-Y’s flexible intelligent recommendation strategies lacked socioeconomic context interlaced with Colombia’s Saber 11 exam data. These strategies—merging collaborative filtering, which predicts outcomes based on like peers’ actions, and data augmentation, where the model’s equilibrium is unbalanced by portraying females too low, forcing a more just system upon training the model—are far-reaching.

The term SAIL-Y functions as an acronym and captures the essence of navigating one’s educational journey. It represents each student as a sailor lost at sea searching for a com-pass. Simultaneously, the system serves as both the ship and the sailor’s guide. SAIL-Y can sense the gales of capability while navigating clear of the fog of social inequality. Within a boundless ocean of possible professions, SAIL-Y provides directed paths for fe-male students toward high-potential careers in which they have long been underrepresented. This paper proposes and analyses several recommendation strategies within the SAIL-Y framework, comparing their accuracy and impact on gender representation. We use a national dataset of over one 300,000 students to evaluate how each method improves the visibility of STEM careers for female users. In doing so, we offer both a technical contribution to educational recommender systems and a concrete step toward greater equity in academic opportunities.

The main contributions of this work are summarised as follows:

SAIL-Y, a novel socioeconomic-aware recommendation framework that integrates standardised test data with gender-focused bootstrapping techniques and collaborative filtering, explicitly designed to promote STEM career paths among underrepresented fe-male students.

A multi-strategy recommendation architecture, where one-layer leverages collaborative patterns among similar students, and another incorporates bias-controlled sampling to address historical imbalances in academic preferences.

Extensive experiments using a large-scale Colombian educational dataset (based on Saber 11 and Saber Pro results), demonstrating that SAIL-Y consistently outperforms baseline models in both recommendation accuracy and fairness—particularly in scenarios involving underrepresented groups and cold-start users.

2. Related Works

2.1. Recommendation Systems in Selecting a University Major

Choosing a university major is a complex and life-defining decision for students, one that involves aligning academic strengths, personal interests, and long-term career prospects. The task of aiding students has been made easier by the development of various recommender systems, which use a student’s test scores, personality traits, learning outcomes, and present and future job markets to personalise academic guidance.

The core of the recommender is centred on personalisation, which is done through collaborative filtering, machine learning, fuzzy logic, or any other hybrid approach. These frameworks aim to recommend degree courses to students based on an analysis of their academic profile and past behaviour, with the goal of maximising satisfaction and success. Some studies indicate that such systems outperform standard advising; some models reportedly achieved up to 98% accuracy in appropriate major assignments [

1,

2,

3]. Aside from personal preferences, situational characteristics are now also considered when generating recommendations. These include demographic criteria, regional job market conditions, and even vocational testing, making the recommendations more thoughtful and plausible than ever before [

4,

5,

6]. For example, systems that consider market trends are more likely to suggest certain majors known to have higher employment rates, thus supporting academic decisions to be made in tune with economic realities.

A remarkable trend in the literature is the creation of hybrid and ontology-based systems, including expert knowledge, machine learning, structured reasoning, and enhancing a system’s accuracy and interpretability [

7]. These systems tend to perform well in cold-start environments, demonstrating high user satisfaction. For instance, some user satisfaction hybrid frameworks report more than 95% user satisfaction, indicating students find these systems beneficial and aligned to their academic and career pathways [

2].

Another critical concern is the usability and user experience. These systems are intuitive and informative, with students reporting a stronger sense of agency and assurance in their educational choices post-interaction [

8]. Additionally, recommender systems have been proven to mitigate the chances of students major-switching or dropping out by aiding students in choosing fields that align with their strengths and expectations early on [

9].

2.2. Gender Bias and Fairness in Educational Recommender Systems

Educational recommender systems are becoming increasingly prevalent, raising concerns regarding fairness and gender bias. This is particularly relevant in their ethical use and practical implementation. Such systems are likely to reinforce or worsen gender inequalities among women in higher education and the workforce, especially in STEM fields.

Sources and manifestations of gender bias are of two types - algorithmic and human. For example, an algorithm may strongly suggest underappreciated STEM fields and over-represent archetypal roles in women’s professions to women due to societal values. This includes formulating recommendations based on historical data and supporting feminised occupations. Students are also biased towards accepting only endorsements that match stereotypes while shunning those assumed to breach social expectations or normed values. Although algorithms are designed to be neutral of bias, human bias will still prevail [

10,

11,

12].

Some technical approaches are provided to alleviate gender bias challenges. Some of them are adversarial learning, where models are trained to remove gender signals from the data, sample weighting, which corrects for unequal group representation, and fairness-through-unawareness, which excludes sensitive attributes like gender [

13,

14]. It is quite interesting that such methods often manage to improve fairness features without significant accuracy loss.

Beyond the algorithms, the overall framework of the system also matters. The Gender4STEM project developed personalised systems that foster equitable teaching suggestions by recommending based on detailed user models [

15]. Users’ trust and acceptance is further enhanced by explainable AI, which has made fairness decisions render trust through transparency.

To assess fairness, researchers apply a different set of evaluation criteria such as group performance gaps, Absolute Between-ROC Area (ABROCA), and disparity ratio of the gendered groups [

14]. These help make it possible to examine the possible impacts of recommendations and evaluate whether the intended interventions are fair from a demographic perspective.

The most significant remaining hurdle is user acceptance, even with sophisticated debiasing methods. Users had rather accept recommendations which align with their biases—regardless of whether these biases are socially constructed—thus undermining the effectiveness of technically fair systems [

16]. Moreover, in any given context, applying problem-solving strategies in one culture or education system may not only fail to work in another but may work against the intended goals [

17]. Other scholars stressed that gender has to be broadened to include race, disability, and other forms of marginalization to expand the fairness criteria [

18].

2.3. Systems Promoting Female Participation in STEM

The participation gap of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) fields continues to persist even with advances in education and research infrastructure over the past several decades. Several studies recognise the presence of personal, environmental, and behavioural factors that act as disincentives to pursue STEM careers lasting from university to early adult life for many budding women scientists. In response, multiple systematic and programmatic frameworks have been instituted to stimulate sustained interest and participation of women and girls in STEM disciplines.

Among personal factors, low self-esteem, reduced self-efficacy, and a poor STEM self-image are some of the most critical barriers. Environmentally and systemically driven obstacles are often far more pronounced. Gendered professional stereotypes, absence of supportive learning communities, and scant female role models constitute major parts of what is termed the environment and strongly affect the perception of and exposure to STEM careers by young girls [

19,

20]. Prevailing social attitudes in the context of enduring inflexible patriarchal systems also severely constrain women’s options to pursue careers in more technical fields. Other behavioural factors like insufficient professional direction, self-driven motivation, and opportunities for hands-on work experience also add to the low enrolment and persistence in offered programmes[

21,

22].

Different approaches identify systems and educational models aimed at alleviating these inequalities. For instance, Hands-on activities, mainly when conducted by female instructors or involve programming for pre-university students, have been shown to promote interest and self-efficacy in STEM to greater levels than traditional methods[

23,

24].

Inclusive learning environments allow for release from the oppression of engagement that female students, particularly when they are in the company of male students, encounter in dominant male spaces due to smaller class sizes and active learning [

21]. Therefore, the function of role models and the visibility of leaders also matter. Young women’s motivation to pursue STEM degrees increases when provided with female leaders who exhibit communal and approachable leadership styles, which empower their sense of belonging [

22].

In STEM education, the perception of professional identity and financial independence is broader for women, both students and educators, when integrated with teaching entrepreneurship education [

25]. These strategies benefit greatly from the application of feminist and ecological frameworks which acknowledge and adapt to the multiple layers of influence on educational pathways of students who are female and design appropriate frameworks for intervention [

20].

Previous research shows that multi-level approaches incorporating family support, role modelling, and inclusive pedagogy are more effective than single-component interventions. Successful systems understand that scaffolding STEM identity in young women must be reinforced throughout educational and sociocultural stages. In addition, policy changes that focus on gender-sensitive curriculum design, institutional support frameworks, and women’s representation within STEM fields are necessary for sustainable transformation [

26].

3. Methodology

The SAIL-Y framework is designed as a multi-layered recommendation system that promotes equitable access to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) careers for female students. By combining data-driven personalization, bias-controlled data augmentation, and fairness-aware evaluation, SAIL-Y aims not only to improve predictive accuracy but also to mitigate gender disparities in academic guidance.

3.1. Dataset

We use a large-scale dataset composed of records from the Colombian Saber 11 standardised exam, collected between 2010 and 2021.

Each student u is represented by a feature vector that concatenates: (i) academic performance (e.g., Saber 11 scores in mathematics, natural sciences, critical reading, English, and citizen competencies), (ii) demographics (gender, region, school type), and (iii) socioeconomic indicators (urban/rural, socioeconomic stratum, parental education). This structured representation allows the model to compare students holistically rather than only on grades.

Notation summary:

U: set of students (users). I: set of university majors (items).

: student feature vector. : subvector of socioeconomic attributes.

: the k nearest neighbors of u according to cosine similarity.

indicator equal to 1 if neighbor v selected major i in ground truth, and 0 otherwise.

3.2. Recommender Framework

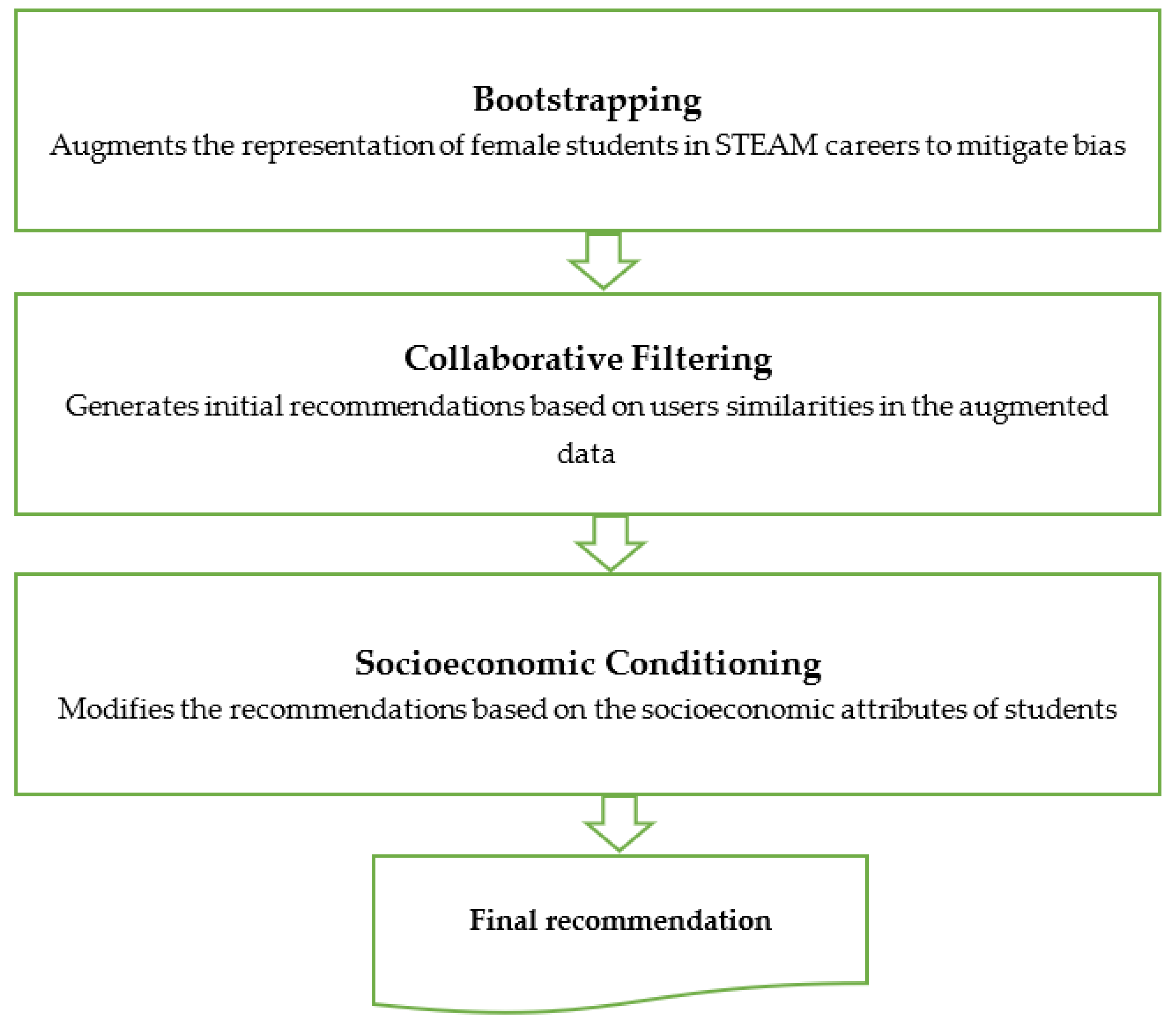

Figure 1 provides an overview of the sequential structure of the SAIL-Y recommendation system. The framework is composed of three key modules. First, the bootstrapping stage increases the presence of female students in STEM careers within the training data to address historical bias. Then, collaborative filtering generates preliminary career recommendations based on user similarity in the augmented dataset. Finally, the socioeconomic conditioning module adjusts these recommendations by incorporating the student’s socioeconomic context. This layered architecture ensures that the system balances accuracy with fairness and contextual sensitivity, leading to more equitable and realistic career suggestions.

(a) Collaborative Filtering Layer

User-based collaborative filtering is applied in this component. It clusters students with comparable academic and socioeconomic backgrounds, recommending majors based on the decisions of their closest peers. This approach captures behavioural similarity. It works well in simulating hidden preferences.

We quantify similarity between two students u and v using cosine similarity:

where

it is the vector of user characteristics, composed of results in the Saber 11 standardized tests and socioeconomic attributes.

The prediction for user

and degree

It is calculated as:

where

is 1 if neighbour

choose the degree

, and 0 otherwise.

(b) Bootstrapped Bias Correction Layer

To counter the imbalance issue of underrepresented female role models in STEM fields, we employ bootstrapped bias correction. This is done by oversampling to artificially augment the profiles of female students who had chosen STEM fields, thus shifting the educational bias of the model towards a more just representation without deleting any original data. Historical data typically underrepresents women choosing STEM majors, which biases any learner trained on it. To counter this, we employ stratified oversampling that increases the presence of female-STEM trajectories during training.

Let D be the original training set, and let

’s define:

Lambda (λ) is the oversampling factor.

Thus, the balanced set is:

This procedure increases the influence of successful trajectories of women in STEM careers without removing original data.

(c) Socioeconomic Conditioning Module

Even with personalization and debiasing, recommendations can overlook structural barriers (e.g., rurality, parental education). We therefore learn a context-aware adjustment that modulates each major’s score according to the student’s socioeconomic profile.

Learned adjustment. For each major i, we developed a logistic model over socioeconomic attributes

to obtain an accessibility/feasibility score:

Interpretation. quantifies how feasible or context-aligned major i is for student u given s_u. Higher indicates that, historically, students with similar contexts have had greater exposure or access to i.

Combining signals. The final score for major i blends the CF signal with the socioeconomic adjustment:

3.3. Experimental Setup

Let U denote the set of users and I the set of possible careers. For each user , the recommender system generates a ranked list of k recommended careers , and the ground truth selection is denoted.

The dataset was split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) subsets using stratified sampling based on gender. All models were trained using the training subset, hyperparameters were tuned on the validation set, and final evaluations were conducted on the test set.

3.4. Experiments

This section presents the experimental evaluation of SAIL-Y, our proposed gender-aware academic recommender system. We aim to answer the following research questions (RQ):

- -

RQ1: How does SAILY perform in terms of recommendation accuracy and fairness compared to standard models?

- -

RQ2: What is the contribution of each component—bootstrapping, collaborative filtering, and socioeconomic conditioning—to overall performance?

- -

RQ3: How sensitive is the system to variations in sampling strategies and neighborhood size?

- -

RQ4: To what extent is SAILY interpretable in its recommendations, particularly in understanding its biasaware behaviour?

3.4.1. Benchmark Methods

We benchmark SAIL-Y against the following baselines:

- -

Random: A naive recommender that assigns majors uniformly at random.

- -

PopularityBased: Recommends the most frequently chosen majors across all students.

- -

Collaborative Filtering (CF): Standard userbased collaborative filtering using nearest neighbors.

- -

ContentBased Filtering: Recommends majors based on closest match to students’ academic profiles.

- -

CF + Bootstrapping: CF trained on a bootstrapped dataset where female STEM choices are oversampled.

- -

SAILY (Full Model): Combines CF, bootstrapping, and socioeconomic conditioning

3.4.2. Performance Metrics

The evaluation metrics used in this study are standard in recommender systems literature [

27,

28]. Fairness metrics such as Disparate Impact Ratio [

29] and adaptations like the Gender Fairness Ratio are inspired by recent advances in fair recommendation systems [

30].

Precision@k: Precision@k measures the proportion of relevant items in the top-k recommendations:

Recall@k: measures the proportion of relevant items that are successfully recommended:

Coverage: indicates the system’s ability to recommend diverse items:

Gender Fairness Ratio (GFR): compares the rate of STEM recommendations between genders.

Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR): adapted from fairness literature, is defined as:

3.4.3. Implementation Settings

All models were implemented in R, using the, caret, and statsmodels packages. Bootstrapping was performed using stratified oversampling with ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1 for female STEM:non-STEM entries. Career similarity was computed using cosine distance, and the top-5 recommendations (k=5) were retained for evaluation.

4. Results

4.1. Performance Analysis (RQ1)

To assess the impact of SAILY on increasing the likelihood of women selecting STEAM careers, we evaluated the overall performance of the system across key metrics including Precision@5, Recall@5, and the Gender Fairness Ratio (GFR).

Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of multiple recommendation models, showing a clear progression in both performance and fairness metrics as the system evolves. The baseline Collaborative Filtering (CF) model yields a Precision@5 of 0.243 and a Gender Fairness Ratio (GFR) of 0.68, indicating notable gender disparity in recommendations. As enhancements are added—such as bootstrapping and bias correction—the GFR improves. The full implementation of the SAILY system achieves the highest scores across all metrics, with a Precision@5 of 0.269, Recall@5 of 0.437, GFR of 1.13, and Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR) of 1.21. These results demonstrate not only an improvement in recommendation accuracy but also a substantial increase in gender fairness. The GFR exceeding 1.0 implies that women receive more STEAM career recommendations than men, directly supporting the system’s goal of mitigating underrepresentation. This evidence strongly supports the conclusion that SAILY is effective in increasing the likelihood of STEAM career recommendations for women, thus answering RQ1 affirmatively.

The results show that SAIL-Y achieves the highest accuracy and substantially improves gender fairness in STEM recommendations. Notably, the DIR above 1.0 indicates that female users receive more STEM-oriented recommendations than males—a desirable outcome for a gender-aware system.

The full SAIL-Y model achieves the highest overall precision and recall, while simultaneously increasing gender fairness. The improvement in DIR>1 confirms that the model effectively shifts the distribution of STEM recommendations toward female students, correcting historical underrepresentation.

Specifically, the SAIL-Y Full improves accuracy by 10% over traditional collaborative filtering and raises the gender equity ratio (DIR) to 1.21, meaning that for every man who receives a STEM recommendation, 1.21 women also receive it. In other words, SAIL-Y helps women see more careers in areas like engineering or technology among their most likely choices, something that classic systems don’t achieve.

4.2. Stepwise Study (RQ2)

To understand each module’s contribution, we conducted a stepwise study, removing one component at a time from the full SAIL-Y pipeline.

Table 2 reports the results.

Therefore, removing the bootstrapping component resulted in decreased fairness and performance: Precision@5 dropped to 0.246, Recall@5 to 0.406, and fairness metrics GFR and DIR fell to 0.74 and 0.79, respectively. This indicates that bootstrapping plays a critical role in enhancing both accuracy and fairness. Excluding socioeconomic conditioning, while retaining bootstrapping and collaborative filtering, led to slightly higher accuracy (Precision@5 = 0.254; Recall@5 = 0.417) but diminished fairness (GFR = 0.94; DIR = 0.95), suggesting that this component is particularly important for promoting equitable recommendations. The full SAIL-Y model outperforms all other variants across every metric—achieving 0.269 Precision@5, 0.437 Recall@5, 1.13 GFR, and 1.21 DIR—demonstrating the synergistic benefit of integrating all three components. These results confirm that each module—bootstrapping, collaborative filtering, and socioeconomic conditioning—adds distinct and complementary value to the system’s overall performance and fairness, thereby providing a robust response to RQ2.

4.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis (RQ3)

To address RQ3, we conducted a parameter sensitivity analysis to examine how key hyperparameters affect the balance between fairness and accuracy in the SAIL-Y system. Specifically, we varied three components:

- -

Oversampling ratios (female STEM:nonSTEM): {1:1, 2:1, 3:1}

- -

TopN recommendation sizes: k = {3, 5, 10}

- -

Neighborhood sizes in CF: knearest neighbors = {10, 20, 50}

The results reveal that an oversampling ratio of 2:1 provides the most effective trade-off between fairness and accuracy. Although a 3:1 ratio further improves fairness metrics, it introduces signs of overfitting, suggesting diminishing returns beyond moderate oversampling. Similarly, a top-k value of 5 strikes the optimal balance between recommendation relevance and breadth, in line with findings from the educational recommender systems literature.

In the collaborative filtering layer, a neighborhood size of 20 yields the most stable performance. Smaller neighborhoods (e.g., k = 10) result in sparsity-related issues, while larger ones (e.g., k = 50) introduce noise and reduce personalization. These findings underscore the importance of moderate debiasing and context-aware calibration, which collectively support the system’s ability to enhance fairness without sacrificing recommendation quality.

4.4. Interpretability (RQ4)

One of the fundamental objectives of the SAIL-Y system is not only to provide accurate recommendations, but also to ensure that these recommendations can be clearly explained, especially in sensitive educational contexts such as vocational guidance. To illustrate this aspect, we conducted a detailed case study with a student selected from the test set.

Student Profile

She is a 17-year-old girl, living in a rural area and coming from a family with low levels of education (neither of the parents finished high school). Despite her context, the student obtained outstanding results in mathematics and natural sciences in the Saber 11 exam, which indicates a high potential to perform in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) areas.

Stage 1: Collaborative filtering

Initially, the system compares this student with other students with similar academic and demographic profiles. This process, known as collaborative filtering, allows us to identify patterns of career choice in similar students. However, in the original dataset, many high-performing students from rural areas tend to select traditional careers such as accounting or administration. For this reason, the first recommendation generated by the system was precisely Business Administration, since it was the most common option among its “educational neighbours”.

Stage 2: Bootstrapping (bias correction)

This is where the equity component of the system comes into play. Through a technique called “bootstrapping”, the SAIL-Y system over-represents positive cases of women who, despite their context, decided to study STEM careers. This allows the student to have access to a new set of references: other girls like her who opted for less traditional paths. The result is that the recommendation changes significantly: Electronic Engineering comes to occupy the first place as a suggestion.

Stage 3: Socioeconomic adjustment

But SAIL-Y doesn’t stop there. At this stage, the system revises the recommendation again, this time considering aspects of the student’s socioeconomic environment: her stratum, whether she lives in a rural or urban area, and the educational level of her parents. Based on this information, the recommendation is adjusted looking for an option that, in addition to being in accordance with their academic profile, is viable and accessible given their conditions.

In this case, the system considers Biology to represent an equally scientific path but with a lower barrier to entry for a rural student since it can offer more alternatives for access to public programs, scholarships, or agreements with nearby institutions.

Thus, the final recommendation, after going through the three layers of analysis, the system suggests to the student the following order of careers: 1.Biology, 2. Electronics Engineering, 3. Mathematics.

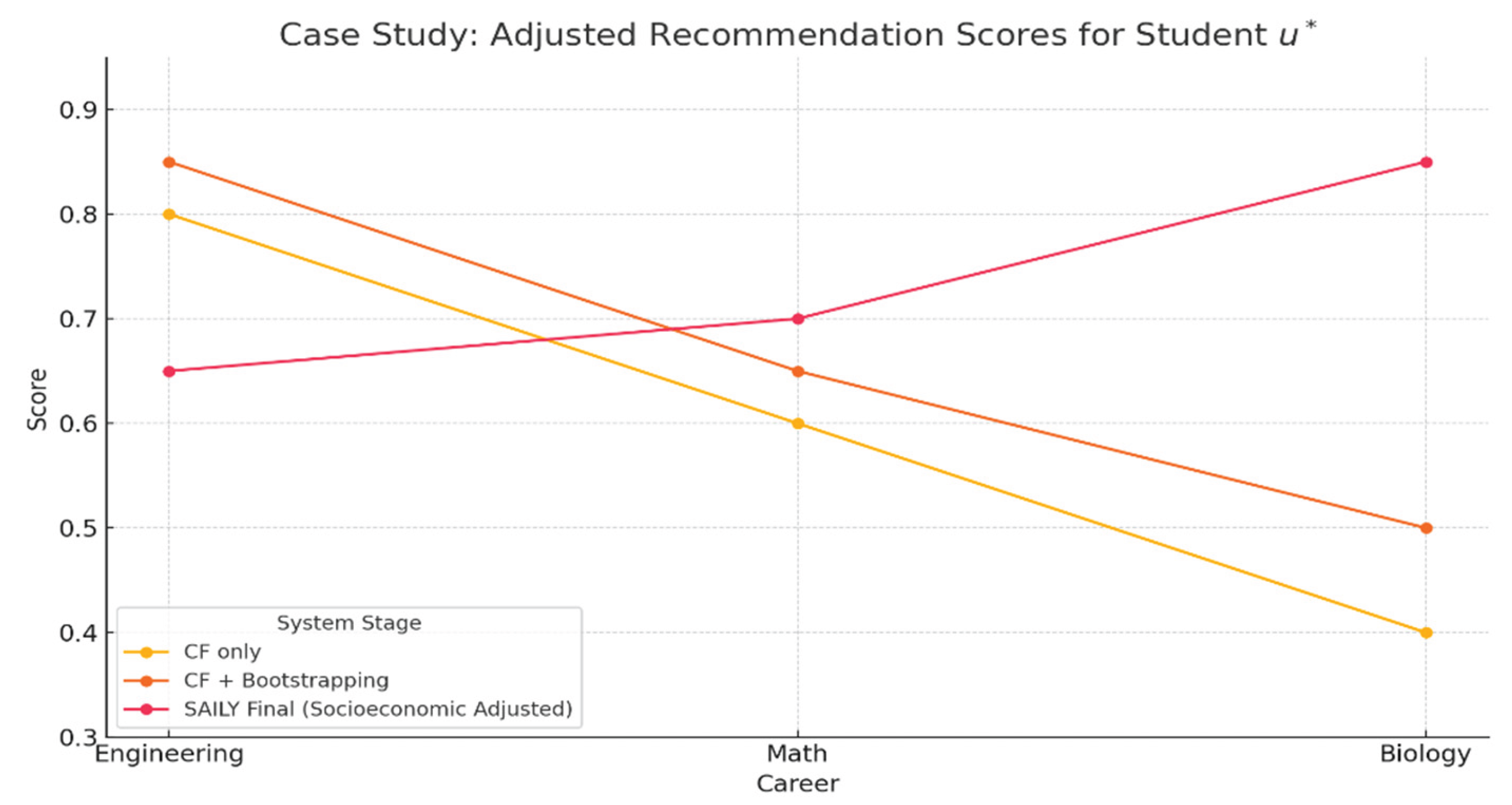

Figure 2, illustrates the evolution of recommendation scores for the case study student u∗u^*u∗ across the three stages of the SAIL-Y system. Initially, under collaborative filtering alone (“CF only”), the highest score is assigned to Engineering, followed by Math and Biology, reflecting historical patterns among students with similar academic performance and socio-demographic background. After applying the bootstrapping module (“CF + Bootstrapping”), which increases the visibility of successful women in STEM fields, Engineering becomes even more strongly recommended, indicating that this module amplifies equity-aware signals in the training data. However, once the socioeconomic conditioning module is applied (“SAIL-Y Final”), Biology emerges as the top recommendation. This shift demonstrates the system’s sensitivity to contextual barriers and opportunities: although Engineering aligns with academic potential, Biology may represent a more feasible and accessible career path given the student’s rural background and low parental education. The figure thus highlights the cumulative and corrective effect of each SAIL-Y module in shaping not only accurate but socially responsible recommendations.

5. Discussion

The development and evaluation of SAIL-Y address a critical gap in educational recommender systems: the need for fair, gender-conscious guidance in university major selection. In this section, we contextualize our findings by comparing SAIL-Y’s methodological design, data usage, and fairness outcomes with prior work and explicitly responding to the research questions.

RQ1 – Does the system increase the likelihood of recommending STEM programs to women?

Most conventional academic recommenders rely on personalization based on exam scores, interests, and educational history, employing collaborative filtering, fuzzy logic, or content-based filtering techniques [

1,

3,

9]. While these models often achieve high accuracy—some reporting up to 98% precision in university degree recommendations [

5]—they frequently reproduce historical biases. For example, collaborative filtering tends to reinforce gender-stereotypical choices, underrepresenting women in STEM [

10].

In contrast, SAIL-Y significantly improves the representation of women in STEM recommendations, as evidenced by its Gender Fairness Ratio (GFR = 1.13) and Disparate Impact Ratio (DIR = 1.21), while also increasing predictive accuracy (Precision@5 = 0.269; Recall@5 = 0.437). These results directly address RQ1 and demonstrate that the system meets its intended fairness goals without compromising user relevance.

RQ2 – What is the contribution of each component—bootstrapping, collaborative filtering, and socioeconomic conditioning—to overall performance?

SAIL-Y’s layered architecture explicitly integrates equity-enhancing mechanisms. A bootstrapped oversampling layer increases the proportion of women choosing STEM majors in the training data, while the socioeconomic-aware conditioning module introduces structural context such as school type, income bracket, and parental education.

To evaluate the contribution of each component, we conducted an ablation study. Removing bootstrapping or conditioning reduced both accuracy and fairness metrics (e.g., GFR dropped from 1.13 to 0.74 without bootstrapping, and DIR fell from 1.21 to 0.79), confirming that each module is essential. This directly responds to RQ2: both the bootstrapping and the conditioning layers are synergistic in enhancing system performance and fairness. Recent research has explored approaches to mitigating gender bias in recommending educational materials using adversarial learning, fairness-through-unawareness, and sam-ple reweighting [

11,

14]. These methods have shown that fairness-enhancing interventions and bias mitigation are possible without sacrificing predictive accuracy. SAIL-Y is aligned with this research but introduces a more interpretable and simpler approach, based on bootstrapped oversampling, that allows for more straightforward implementation on large public datasets and is more appropriate for low-resource educational contexts.

Additionally, unlike some fairness-aware systems that focus on algorithmic neutrality, SAIL-Y employs constructive bias: deliberately increasing the chances that women are recommended for STEM fields to counter persistent underrepresentation. This bias em-bodies feminist rationale and social identity theories that call for structural changes rather than neutral models [

20].

RQ3 – How sensitive is the system to parameter tuning (e.g., oversampling ratio, top-N recommendation size, neighbourhood size)?

The model’s performance was further examined under different configurations. We tested various oversampling ratios (1:1, 2:1, 3:1), top-k values (3, 5, 10), and neighbourhood sizes (10, 20, 50) in the collaborative filtering layer.

Findings show that an oversampling ratio of 2:1 offers the best trade-off between fairness and overfitting. Similarly, a top-k value of 5 balances recommendation diversity and relevance, while a neighbourhood size of 20 provides stable and interpretable predictions. These results support RQ3, confirming that moderate parameter tuning is sufficient to maintain robustness and enhance fairness.

RQ4 – Does the fairness-enhancing approach compromise system performance?

Some fairness-aware systems emphasize algorithmic neutrality, which may reduce accuracy. In contrast, SAIL-Y intentionally introduces constructive bias by increasing the likelihood that women receive STEM recommendations. This strategy draws on feminist and social identity theories, advocating for structural correction rather than neutrality [

20].

Our results show that this constructive bias does not degrade performance. On the contrary, incorporating fairness-aware mechanisms improves both fairness and accuracy compared to baseline models. This finding addresses RQ4, confirming that it is possible to enhance fairness without incurring a trade-off in predictive performance.

Overall, SAIL-Y explores social and technical dimensions from recent literature on recommender systems, educational fairness, and gender inclusivity in STEM. It is designed to transform the status quo and foster more equitable outcomes through its layered architecture, design prioritising fairness, and personalised responses based on specific con-texts

6. Conclusions

This paper introduced SAIL-Y, a gender-sensitive recommendation framework designed to increase the representation of women in STEM programs. Using real-world educational data and fairness-aware mechanisms, the system demonstrated strong performance across key evaluation metrics.

In direct response to the research questions:

RQ1: SAIL-Y outperforms baseline models in recommending STEM careers to women, achieving higher accuracy and fairness scores.

RQ2: The contribution analysis confirms that both bootstrapping and socioeconomic conditioning play critical roles in enhancing fairness without degrading performance.

RQ3: Parameter sensitivity analysis reveals that moderate oversampling and calibrated neighbourhood sizes offer the best fairness–accuracy trade-offs.

RQ4: The final model achieves improved gender fairness while preserving the quality of recommendations, indicating that fairness and performance are not mutually exclusive.

The findings contribute to the growing field of algorithmic fairness in education and demonstrate the feasibility of embedding equity-aware design into recommender systems. Future work may explore extending SAIL-Y to other underrepresented groups and educational contexts.

The results demonstrated increased predictive accuracy with SAIL-Y and marked improvements in equity-focused fairness metrics such as the Gender Fairness Ratio and Disparate Impact Ratio. This supports previously stated recommendations made by fairness-aware recommendation systems that precision/recall optimised models advocated incorporating bias mitigation strategies. Unlike most systems, SAIL-Y embeds equity aims in the design phase rather than post-hoc adjustments which situates SAIL-Y within holistic frameworks of gender inclusion in STEM education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.J.D.-D. and R.H.-N.; methodology, E.J.D.-D. and R.H.-N.; software, E.J.D.-D.; validation, E.J.D.-D. and R.H.-N.; formal analysis, E.J.D.-D.; data curation, E.J.D.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.D.-D. and R.H.-N.; writing—review and editing, E.J.D.-D. and R.H.-N.; visualisation, E.J.D.-D.; supervision, R.H.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are openly available in the Data repository at DOI: 10.17632/vnmf6n8987.1

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Somyürek, S.; Aksoy, N. Navigating Academia: Designing and Evaluating a Multidimensional Recommendation System for University and Major Selection. Psychology in the Schools 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoud, C.; Moussa, S.M.; Obeid, C.; Khoury, H.E.; Champin, P.-A. A Comparative Analysis of Different Recommender Systems for University Major and Career Domain Guidance. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 28, 8733–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.; Alzhrani, N.; Algethami, H. Fuzzy-Based Recommendation System for University Major Selection. 22 July 2024; 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, N.; Abed, M.; Soui, M. SBS Feature Selection and AdaBoost Classifier for Specialization/Major Recommendation for Undergraduate Students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 17867–17887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, Y.; Salman, Y.; Hasasneh, A. A Recommendation System for Selecting the Appropriate Undergraduate Program at Higher Education Institutions Using Graduate Student Data. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahoz-Domínguez, E.J.; Hijón-Neira, R. Recommender System for University Degree Selection: A Socioeconomic and Standardised Test Data Approach. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.A.; Nguyen, H.-H.; Nguyen, D.-L.; Le, M.-D. A Course Recommendation Model for Students Based on Learning Outcome. Educ Inf Technol 2021, 26, 5389–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, G.; Sathiya Devi, S. Hybrid Recommendation System Based on Collaborative and Content-Based Filtering. Cybernetics and Systems 2023, 54, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, C.; Lahoud, I.; Khoury, H.E.; Champin, P.-A. Ontology-Based Recommender System in Higher Education. Companion Proceedings of the The Web Conference 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, K.; Bian, A.; Islam, R.; Keya, K.; Foulds, J.R.; Pan, S. When Biased Humans Meet Debiased AI: A Case Study in College Major Recommendation. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems 2023, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Xu, B.; Zhao, N. Mitigating Sensitive Data Exposure with Adversarial Learning for Fairness Recommendation Systems. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 18097–18111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Hawn, A. Algorithmic Bias in Education. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 2021, 32, 1052–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, J. Debiasing Education Algorithms. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, W.; Xia, F.; Pan, S. A Survey on Fairness-Aware Recommender Systems. Inf. Fusion 2023, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens-Volland, A.G.; Gratz, P.; Baudet, A.; Deladiennée, L.; Gallais, M.; Naudet, Y. Personalized Recommender System for Improving Gender-Fairness in Teaching. 2019 14th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization (SMAP); 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, E. Gender-Biased Evaluation or Actual Differences? Fairness in the Evaluation of Faculty Teaching. Higher Education 2021, 83, 1315–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, M.E.; Maher, Z.; Ross, H.M. Addressing Gender-Related Implicit Bias in Surgical Resident Physician Education: A Set of Guidelines. Journal of surgical education 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorre, A.B.; Rekabsaz, N.; Parada-Cabaleiro, E.; Brandl, S.; Lesota, O.; Schedl, M. Investigating Gender Fairness of Recommendation Algorithms in the Music Domain. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasekan, O.; Pena, M.T.G.; Odebode, A.; Mabica, A.P.; Mabasso, R.A.; Mogbadunade, O. Fostering Sustainable Female Participation in STEM Through Ecological Systems Theory: A Comparative Study in Three African Countries. Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msambwa, M.M.; Daniel, K.; Cai, L.; Antony, F. A Systematic Review Using Feminist Perspectives on the Factors Affecting Girls’ Participation in STEM Subjects. Science & Education 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballen, C.; Aguillon, S.; Awwad, A.; Bjune, A.; Challou, D.; Drake, A.G.; Driessen, M.; El-Lozy, A.; Ferry, V.E.; Goldberg, E.; et al. Smaller Classes Promote Equitable Student Participation in STEM. BioScience 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rios, K. Exploring the Effects of Promoting Feminine Leaders on Women’s Interest in STEM. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2022, 14, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, S.H.C.; Caicedo, V.V.O.; Marrugo-Salas, L.; Contreras-Ortiz, M.S. A Model for the Development of Programming Courses to Promote the Participation of Young Women in STEM. Ninth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM’21); 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Suarez, D.; Curiel-Enriquez, I.M.; Turner-Escalante, J.E.; Ocampo-Bahena, D.H. Building an Inclusive STEM Future: Engineering Students Empower Over 1200 Students by Designing Innovative Workshops Fostering Women’s Participation in Engineering. 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON); 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, M.; Shekhar, P. Developing a Conceptual Framework: Women STEM Faculty’s Participation in Entrepreneurship Education Programs. Research in Science Education 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, N.A.; Rottinghaus, P.J.; Casanova, T.; Borgen, F.; Betz, N. Expanding Women’s Participation in STEM. Journal of Career Assessment 2017, 25, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Introduction to Recommender Systems Handbook. In Recommender systems handbook; Springer, 2011; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Herlocker, J.L.; Konstan, J.A.; Terveen, L.G.; Riedl, J.T. Evaluating Collaborative Filtering Recommender Systems. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2004, 22, 5–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Friedler, S.A.; Moeller, J.; Scheidegger, C.; Venkatasubramanian, S. Certifying and Removing Disparate Impact. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, August 10, 2015; pp. 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand, M.D.; Tian, M.; Azpiazu, I.M.; Ekstrand, J.D.; Anuyah, O.; McNeill, D.; Pera, M.S. All The Cool Kids, How Do They Fit In?: Popularity and Demographic Biases in Recommender Evaluation and Effectiveness. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, January 21 2018; PMLR; pp. 172–186. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).