Submitted:

09 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

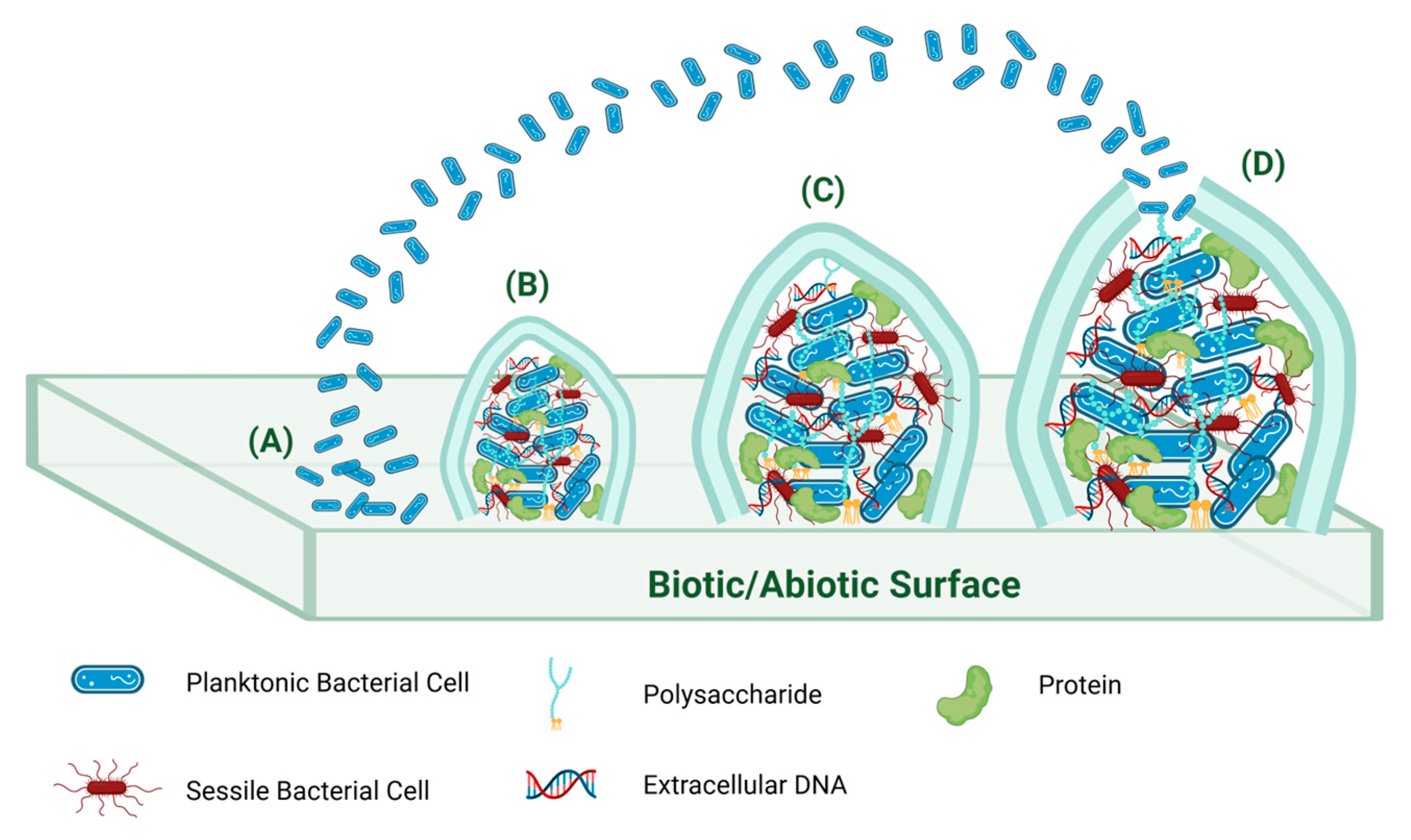

3. Bacterial Biofilm

4. Natural Products for the Antibiotic Pipeline

5. Seaweed-Derived Microorganisms

5.1. Antibacterial Metabolites from Seaweed Endophytes and Other Marine-Derived Fungi

5.2. Antibiofilm Compounds from Marine-Derived, Endophytic and Other Fungi

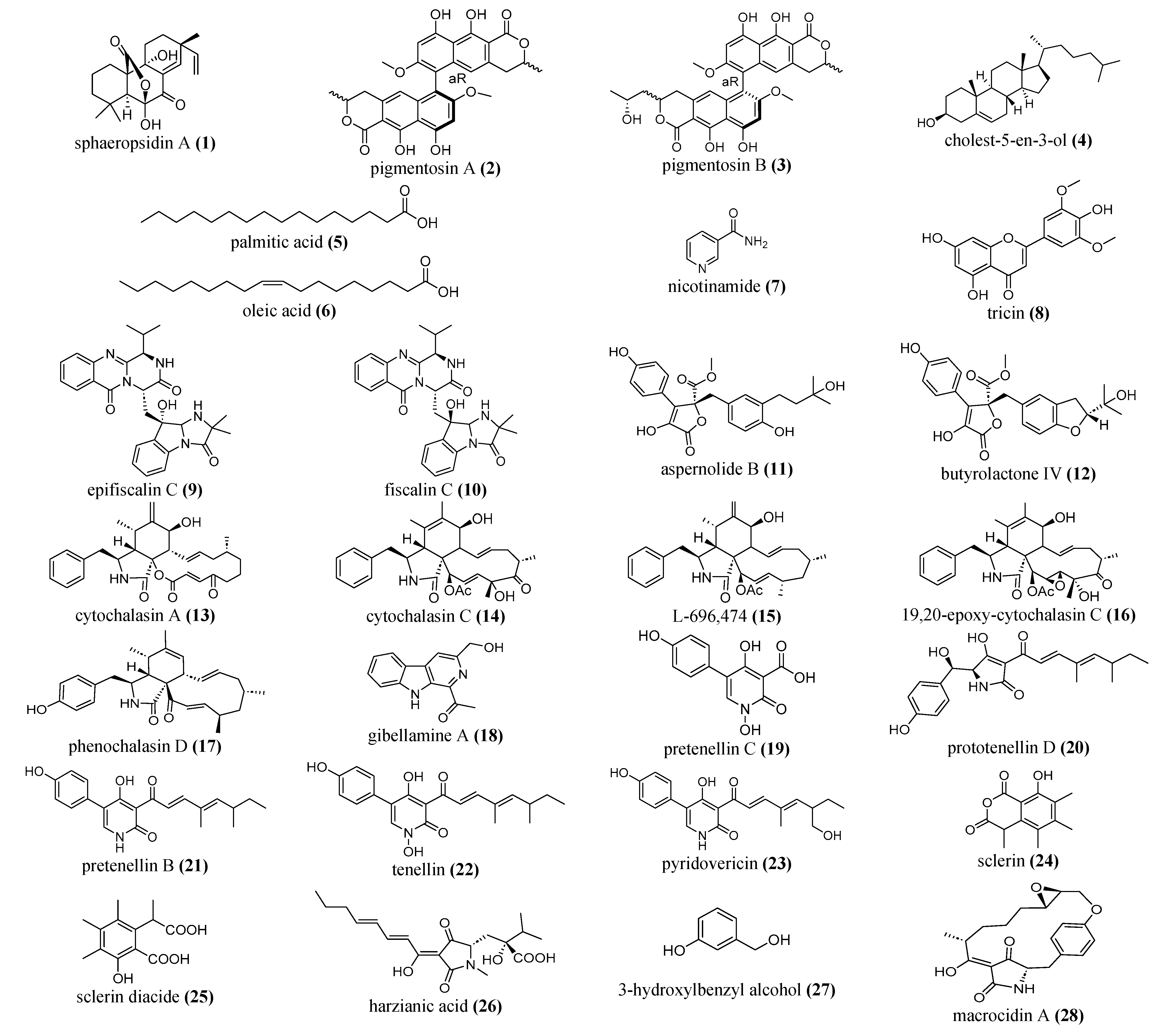

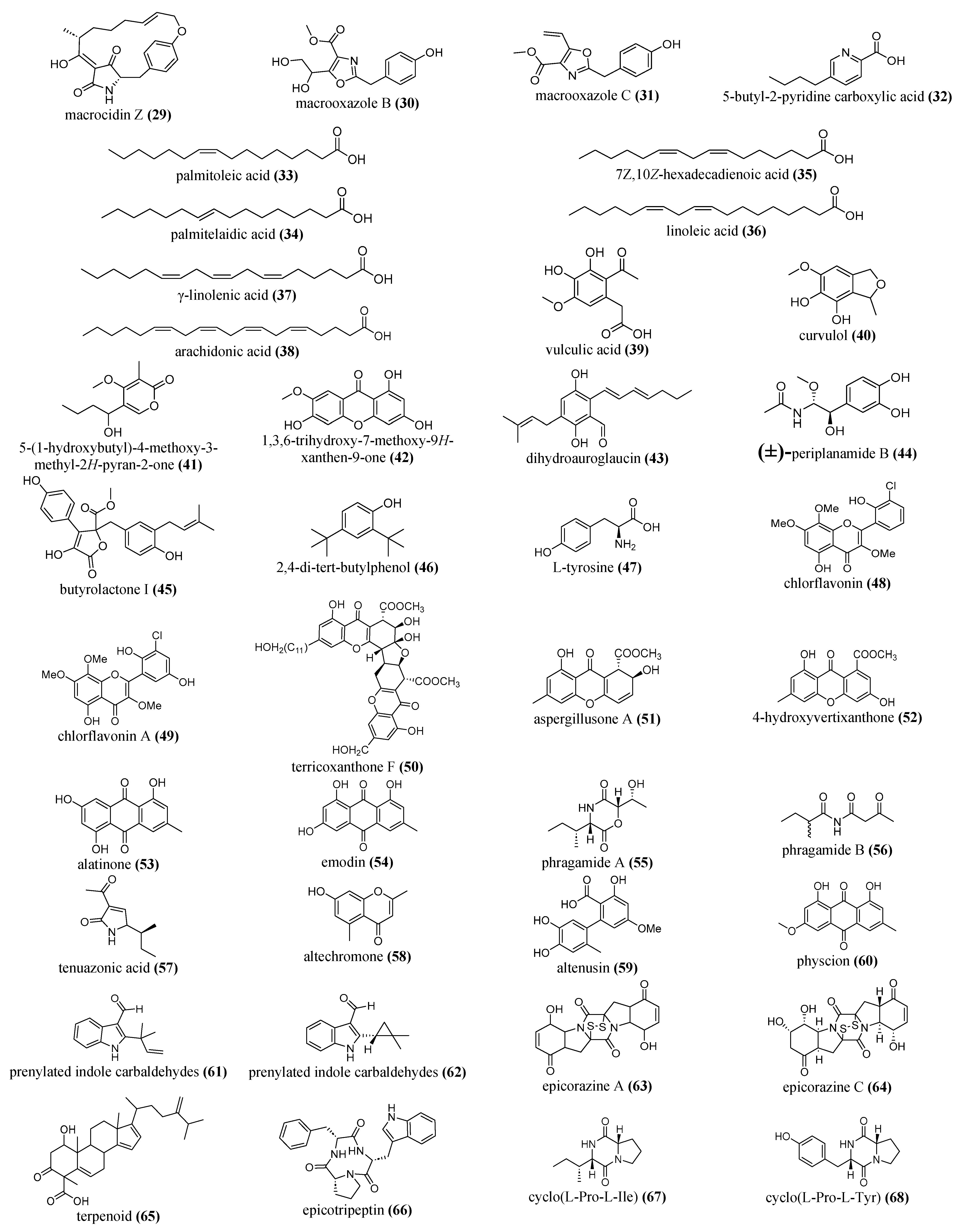

5.2.1. Terpenoids and Steroids

5.2.2. Alkaloids and Peptides

5.2.3. Flavonoids, Phenolics and Polyketide Compounds

|

Bioactive compounds |

Fungal species |

Fungal source |

Antibiofilm activity |

Test Bacteria used | Reference |

| Non marine and non-endophytic fungal source | |||||

| sphaeropsidin A (1) |

Diplodia. corticola |

fungal phytotoxin |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Reference MRSA strains: 60% at 3. 12 μg/mL. MRSA clinical: 53% at 1/4 MIC (1.56 μg/mL) Preformed biofilms: (adhesion) Reference P. aeruginosa strains: 50% at a 1/4 MIC: 3.12 μg/mL. clinical P. aeruginosa: 62% at a 1/4 MIC: 3.12 μg/mL. |

MRSA ATCC 43300 reference strains MRSA 1118-116 P. aeruginosa PAO1 as reference strains extended-spectrum beta- lactamase (ESBL) producing P. aeruginosa 0418-925 P. aeruginosa 0418-925. |

[116] |

| pigmentosin A (2) and pigmentosin B (3) | Gibellula sp. | spider |

Biofilm formation inhibition: MIC values: 1.9 and 15.6 μg/mL |

S. aureus DSM1104 |

[131] |

| astucin composed of 92 amino acid residues. | Aspergillus tubingensis | soil |

Biofilm formation inhibition: 99.9%: MBIC: 2 μg/mL against S. aureus MBIC: 8 μg/mL against MRSA |

S. aureus & MRSA |

[128] |

| cholest-5-en-3-ol (4), palmitic acid (5), oleic acid (6), nicotinamide (7), tricin (8) |

Sarocladium kiliense SDA20 | soil |

Biofilm formation inhibition: B. subtilis: Compound 4: 78 %, Compound 5: 71 %, Compound 6: 52% S. aureus: Compounds 4 and 5: 59 %, Compound 8: low inhibition activity around 35%. E coli: Compound 4: 59% Compound 6: 53% Compound 7: 40% Compound 8: ca. 42% P. aeruginosa: No activity |

S. aureus B. subtilis P. aeruginosa E. coli |

[111] |

| epifiscalin C (9), fiscalin C (10), aspernolide B (11), and butyrolactone IV (12) |

fungal extract | NA |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compounds 9, 10, and 11: Above 60%: 16 μg/mL. Compound 12: Above 50%: 64 μg/mL |

MRSA (ATCC 43300) | [132] |

| cytochalasin A (13), cytochalasin C (14), L-696,474 (15), 19,20-epoxy-cytochalasin C (16), and phenochalasin D (17) |

Hypoxylon fragiforme |

Harz mountains |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 13: 91%: 16 μg/mL, Compound 14: 42%: 256 μg/mL, Compound 15: 44%: 16 μg/mL Compounds 16 and 17: 20 to 40%. |

S. aureus DSM 1104 |

[124] |

| gibellamine A (18) |

Gibellula gamsii strain BCC47868 |

spider |

Biofilm formation inhibition: MIC value of 62.5 μg/mL It significantly inhibited biofilm formation. |

S. aureus DSM1104 (ATCC 25923) |

[133] |

| pretenellin C (19) prototenellin D (20), pretenellin B (21), tenellin (22) and pyridovericin (23) |

Entomopatho-genic fungus Beauveria neobassiana |

Coleoptera |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 19: 46 ± 9% at 31.3 µg/mL Compound 20: 53 ± 7% at 7.8 µg/mL Compound 21: 37 ± 7% at 7.8 µg/mL Compound 22: 36 ± 13% at 7.8 µg/mL. Compound 23: 48 ± 5 % at 62.5 µg/mL. |

S. aureus DSM 346 |

[134] |

| sclerin (24) and its diacid (25) |

Hypoxylon fragiforme |

Harz mountains |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 24 86% at 256 μg/mL Compound 25 80% at 256 μg/mL |

S. aureus DSM 1104 |

[125] |

| harzianic acid (26) |

Trichoderma harzianum, two strains E45 and ET45 |

soil |

Biofilm formation inhibition: at 16 μg/mL: Significant inhibition of biofilm formation in both MRSP and MSSP Pre-formed biofilms: at 32 and 64 μg/mL: Statistically significant disaggregation of pre-formed biofilm produced by MSSP. |

Staphylo- coccus pseudinter- medius (S. pseudinter- medius) methicillin-resistant (MRSP) methicillin-susceptible (MSSP) strains. |

[135] |

| Exopolysaccharide (EPS) | Fomitopsis meliae AGDP-2 | mushrooms |

Biofilm formation inhibition: at 10,000 µg/mL: P. aeruginosa: 86.01% S. typhi: 17.64% |

P. aeruginosa Salmonella typhi (S. typhi) ATCC 6539 |

[136] |

| 3-hydroxyl-benzyl alcohol (27) |

Aspergillus nidulans strain KZR-132 |

forest soil |

Biofilm formation inhibition: at 18.75 μg/mL: S. aureus MTCC 96: 89.2% S. aureus MLS16 MTCC 2940: 88.2 % S. aureus ATCC 6538P: 85.6% B. subtilis MTCC 121: 80% M. luteus MTCC 2470: 90.2% Act. viscosus ATCC 15987: 80.6% C. violaceum: 88% at 37.5 μg/mL: E. coli: 75% K. planticola: 70.9% P. aeruginosa: 65.5% |

S. aureus MTCC 96, S. aureus MLS16 MTCC 2940, S. aureus ATCC 6538P, B. subtilis MTCC 121, M. luteus MTCC 2470, Act. viscosus ATCC 15987 C. violaceum E. coli, K. planticola P. aeruginosa |

[122] |

| macrocidin A (28), macrocidin Z (29), macrooxazole B (30), macrooxazole C (31) |

Phoma macrostoma DAOMC 175,940 |

Circium arvense |

Biofilm formation inhibition: at 250 µg/mL: Compound 30: 65%, Compound 31: 75% Compound 28: 79% Compound 29: 76% Pre-formed biofilms: at 250 µg/mL: Compound 28: 75% Compound 29: 73% |

S. aureus DSM 1104 |

[120] |

| 5-butyl-2-pyridine carboxylic acid (32) |

Aspergillus fumigatus nHF-01 |

NA |

Biofilm formation inhibition: 22.30%: 4 µg/mL against B. cereus 129 µg/mL against E. coli |

Bacillus cereus (B. cereus) MTCC 1272, E. coli MTCC 723, E. coli ATCC DH5α, |

[137] |

| palmitoleic acid (33), palmitelaidic acid (34), 7Z,10Z-hexadecadienoic acid (35), linoleic acid (36), γ-linolenic acid (37), arachidonic acid (38) |

Hypoxylon fragiforme |

Harz mountains |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 33: Sub-MIC: at 64 µg/mL: 54 ± 2% against S. aureus at 120 µg/mL: 49 ± 2% against S. aureus Compound 34: Sub-MIC: at 256 µg/mL: 25 ± 4% against E. coli at 16 µg/mL: 21± 4 % against S. aureus Compound 35: Sub-MIC: at 128 µg/mL: 62 ± 8% against E. coli at 8 µg/mL: 60± 9 % against S. aureus at 8 µg/mL: 22± 14 % against S. epidermidis at 128 µg/mL: 38 ± 12 % against S. mutans Compound 36: Sub-MIC: at 16 µg/mL: 35 ± 15 % against B. cereus at 8 µg/mL: 54 ± 4 % against S. aureus Compound 37: at 4 µg/mL: 58 ± 1 % against S. aureus at 128 µg/mL: 44 ± 19 % against S. epidermidis Compound 38: Sub-MIC: at 64 µg/mL: 36 ± 2 % against B. cereus 35 ± 11 % against S. aureus |

B. cereus DSM 626, E. coli MT102, P. aeruginosa PA14, S. aureus DSM 1104, S. epidermidis ATCC 35984, S. mutans UA59 |

[126] |

| extracellular protein |

Aspergillus oryzae | NA |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Significantly inhibited at 1/4 MIC (75 μg/mL) and 1/2 MIC (150 μg/mL). |

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) ESBL |

[138] |

| 2) Endophytic Fungal Metabolites | |||||

| vulculic acid (39), curvulol (40) | Chaetosphaeronema achilleae | Taxus baccata |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Both compounds: 100% at 256 μg/mL. |

S. aureus | [139] |

| 5-(1-hydroxybutyl)-4-methoxy-3- methyl-2H-pyran-2-one (41) | Colletotrichum acutatum | Angelica sinensis | NA |

S. aureus K. pneumonia |

[140] |

| fractions (AF1 and AF2) |

Alternaria destruens (AKL-3) |

Calotropis gigantea |

Biofilm formation inhibition: AF1: 22.5 μg/mL: P. aeruginosa: (58.15%) E. coli (around 49%) S. enterica (around 42%). AF2: 22.5 μg/mL: S. enterica (23.2%). Pre-formed biofilms inhibition: AF1: 22.5 μg/mL: P. aeruginosa (35.58%) E. coli (21.84%) AF2: 22.5 μg/mL: P. aeruginosa 19.2% |

P. aeruginosa E. coli Salmonella enterica (S. enterica) |

[141] |

| 1,3,6-trihydroxy-7-methoxy-9H-xanthen -9-one (42) |

Penicillium citrinum-314 |

Halocnemum strobilaceum |

Biofilm formation inhibition: 100 %: MBIC value of 62.5 μg/mL. |

P. aeruginosa | [142] |

| dihydroauroglaucin (43) |

Aspergillus amstelodami (MK215708) |

Ammi majus L. Fruits |

Biofilm formation inhibition: S. aureus and E. coli: MBIC = 7.81 μg/mL S.mutans: MBIC = 15.63 μg/mL P. aeruginosa: MBIC = 31.25 μg/mL |

S. aureus E. coli S. mutans P. aeruginosa |

[143] |

|

(±)-periplanamide B (44), butyrolactone I (45) |

Aspergillus terreus AH1 |

Ipomoea carnea |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 44: S. aureus 90.65%: B. subtilis 85.09% E. coli 63.144% Compound 45: P. aeruginosa. 71.81% |

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) S. aureus (ATCC 6538-P), E. coli (ATCC 25955) B. subtilis (ATCC 6633) |

[144] |

| 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (46) |

Daldinia eschscholtzii (TP2-6) |

Tridax procumbens |

Biofilm formation inhibition: 49% at 80 μg/mL |

P. aeruginosa PAO1 | [123] |

| L-tyrosine (47) | Rhizopus oryzae AUMC14899 | Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) |

Biofilm formation inhibition: PA-02: 83% (3 μg/mL) SA-04: 87% (7.5 μg/mL) |

P. aeruginosa PA-02, S. aureus SA-04 |

[127] |

| chlorflavonin (48) and chlorflavonin A (49) |

Aspergillus candidus T1219W1 |

Pittosporum mannii Hook f. |

Biofilm formation inhibition: S. aureus: MBEC50: 256 μg/mL Compound 48: 72.15% Compound 49: 75.32% E. coli MBEC50: 128 μg/mL Compound 48: 80.12% Compound 49: 81.22% |

S. aureus E. coli |

[121] |

| terricoxanthone F (50), aspergillusone A (51), 4-hydroxy vertixanthone (52) alatinone (53) emodin (54) |

Neurospora terricola HDF-Br-2 |

vulnerable

conifer Pseudotsuga gaussenii |

Biofilm formation inhibition: (MBIC) Compounds 50 and 51: 128 μg/mL Compounds 52 and 53: 32 μg/mL Compound 54: 16 μg/mL Pre-formed biofilms: (MBIC) Compound 50: 256 μg/mL. Compounds 51, 52 and 53: 128 μg/mL Compound 54: 32 μg/mL |

S. aureus | [145] |

| Mixture of fatty acids | Arthrographis kalrae |

Coriandrum sativum |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Minimal biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) of 31.3 μg/mL completely inhibited S. mutans biofilm |

S. mutans ATCC 25175 |

[146] |

| 3) Marine fungal metabolites | |||||

| phragamides A (55) and B (56), tenuazonic acid (57) and altechromone (58) altenusin (59) |

A. alternata 13A |

Phragmites australis |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Gram-positive strains: 70 to 80% Gram-negative strains: 40 to 60%. Compound 59 exhibited moderate biofilm formation inhibition only against B. subtilis. |

S. aureus B. subtilis E. coli P. areuginosa |

[90] |

| emodin (54) and physcion (60), and two prenylated indole carbaldehydes (61) and (62) |

Eurotium chevalieri KUFA 0006 | Rhizophora mucronata |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compounds 54, 60, 61 and 62 showed inhibition of biofilm production in S. aureus ATCC 25923 significantly (*p<0.05). Compound 61: at 64 μg/mL. nearly 80% reduction of S. aureus. |

S. aureus ATCC 25923 E. coli ATCC 25922 |

[88] |

| epicorazines A (63) and C (64) as well as a new terpenoid (65) |

Epicoccum nigrum |

Phaeurus antarcticus (seaweed) |

Biofilm formation inhibition: MBEC: Compound 63: 50 μg/mL Compound 64: 25 μg/mL Compound 65: 25 μg/mL Post- biofilms Inhibition: Compound 65: 100 μg/mL. |

MRSA | [83] |

| epicotripeptin (66) cyclo(L-Pro-L-Ile) (67), cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr) (68) |

Epicoccum nigrum M13 (marine endophytes) |

Thalassia hemprichii leaves seagrass |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 66: Gram-positive strains (55 to 70% inhibition) Gram-negative strains (20 to 30% inhibition) Compounds 67 and 68: moderate inhibition of biofilm formation in both Gram-positive strains but were not active against the tested Gram-negative strains. |

S. aureus B. subtilis E. coli P. areuginosa |

[90] |

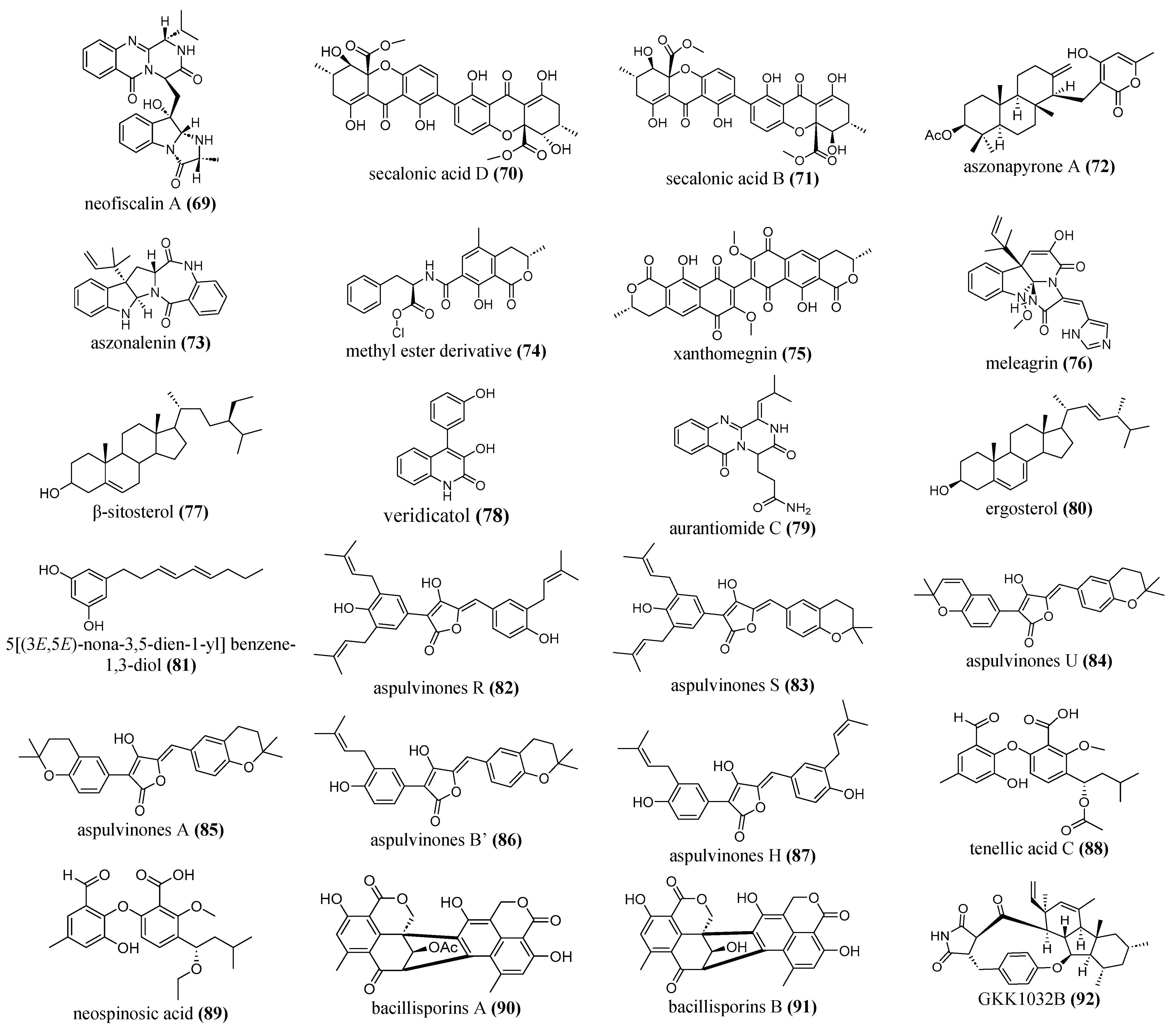

| neofiscalin A (69) |

Neosartorya siamensis (KUFA 0017) |

marine sponge |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 69 against: MRSA: 96 μg/mL VRE: 80 μg/mL at a concentration of 200 μg/mL, it was able to reduce the metabolic activity of the biofilms by 50%. |

MRSA Vancomycin -resistant E. faecalis (VRE) |

[147] |

| secalonic acid B (70) and D (71) | Penicillium sp. SCSGAF 0023 CCTCCM 2012507 | marine |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Both Inhibited by >90% at 6.25 μg/mL |

S. aureus |

[39] |

| aszonapyrone A (72), aszonalenin (73), methyl ester derivative (74), xanthomegnin (75) |

Neosartory siamensis Neosartorya takakii Aspergillus elegans |

marine |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 72: S. aureus ATCC 29213 at 9 μg/mL: 72% S. aureus 272123 6.25 μg/mL: 94% Compound 73: S. aureus ATCC 29213 at 100 μg/mL: 63% S. aureus 272123 at 6.25 μg/mL: 93% Compound 74: S. aureus ATCC 29213 at 10 μg/mL: 88% S. aureus 272123 at 25 μg/mL: 98% Compound 75: S. aureus ATCC 29213 at 100 μg/mL: 96% S. aureus 272123 at 50 μg/mL: (84%) |

S.aureus ATCC 29213 S. aureus 272123 |

[115] |

|

meleagrin (76) |

Emericella dentata Nq45 |

marine |

Biofilm formation inhibition: 250 μg/mL: 87.1% |

S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

[148] |

| β-sitosterol (77), veridicatol (78), aurantiomide C (79), ergosterol (80) |

Penicillium sp. MMA | marine |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 77: B. subtilis 28% S. aureus 64% Compound 78: B. subtilis 35% Compounds 78, 79, 80: E. coli from 40 -55% |

S. aureus E. coli B. subtilis |

[113] |

| 5[(3E,5E)-nona-3,5-dien-1-yl]benzene-1,3-diol (81) | Aspergillus stellatus KUFA 2017 | marine sponge Mycale sp. |

Biofilm formation inhibition: 100 % at E. faecalis: MIC (16 μg/mL) S. aureus: 2xMIC (32 μg/mL). |

S. aureus ATCC 29213, E. faecalis ATCC 29212 |

[92] |

| Fraction AW1011 |

Aspergillus welwitschiae FMPV 28 |

marine sponge

Taedania sp. |

Biofilm formation inhibition: remarkable decrease in biofilm formation, in a dose-dependent antibiofilm activity. |

S. aureus ATCC 25904 |

[149] |

| Extracellular thermostable antibacterial peptide designated as MFAP9 |

Aspergillus fumigatus BTMF9 |

marine |

Biofilm formation inhibition: - > 85% against all test bacteria. |

B. cereus (NCIM 2155), Bacillus circulans (B. circulans) (NCIM 2107), Bacillus coagulans (NCIM 2030), Bacillus pumilus (NCIM 2189) S. aureus (NCIM 2127) |

[150] |

| aspulvinones R (82), S (83), and U (84) aspulvinones A (85), B’ (86), H (87) |

Aspergillus flavipes KUFA1152 |

marine sponge

Mycale sp |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 87: at MIC (32μg/ mL) and 2xMIC for both strains Compound 86 at ½ MIC (16 μg/ mL). Compounds 82 and 83, all concentrations tested 2xMIC (16μg/ mL), MIC (8 μg/ mL), ½ MIC (4 μg/ mL), including ¼ MIC (2μg/ mL) Mixture of 84 and 85 E. faecalis at MIC (32μg/ mL) and 2xMIC (64 μg/ mL). |

E. faecalis ATCC 29212 S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

[85] |

| tenellic acid C (88), neospinosic acid (89) |

Neosartorya spinosa KUFA 1047 |

marine sponge |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 88: at 64 μg/ mL: E. coli (11.61± 0.09%) E. faecalis (24.11 ± 0.1%) S. aureus (15.54 ± 0.1%) Compound 89: at 64 μg/ mL: E. coli (16.11 ± 0.19%) S. aureus (44 ± 0.06 %) |

E. coli ATCC 25922 E. faecalis ATCC 29212 S. aureus ATCC 29213 |

[86] |

| bacillisporins A (90) and B (91) |

Talaromyces pinophilus KUFA 1767 |

marine sponge |

Biofilm formation inhibition: Compound 90: at 8 μg/ mL (2xMIC): 99.92 ± 0.03% 4 μg/ mL (MIC): 99.81 ± 0.17% Compound 91: at 16 μg/ mL (2xMIC): 99.87 ± 0.05% 8 μg/ mL (MIC): 99.71 ± 0.13% |

S. aureus ATCC 29213 | [93] |

| GKK1032B (92) | Penicillium erubescens KUFA0220 |

marine sponge

Neopetrosia sp |

Biofilm formation inhibition: at: 8 μg/ mL (MIC) and 16 μg/ mL (2xMIC) displayed significant activities. |

E. faecalis ATCC29212 | [89] |

6. Future Directions

6.1. Inducing the Production of Fungal Metabolites

6.2. Metabolomic Approach

6.3. Detecting Antibiofim Compounds

7. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| QS | Quorum sensing system |

| AI | Auto inducer |

| SNP | Sodium nitroprusside |

| NPs | Natural products |

| EtOAc | Ethyl acetate |

| sp | species |

| BGC | Biosynthetic gene cluster |

| Mr | Molecular weight |

| KDa | KiloDaltons |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| LC | Liquid chromatography |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MBEC | Minimum biofilm eradication bacteria |

| MBIC | Minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PLS-DA | Partial Least Square-Discriminant Analysis |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal Partial Least Square-Discriminant Analysis |

References

- Talebi Bezmin Abadi, A.; Rizvanov, A. A.; Haertlé, T.; Blatt, N. L. , World Health Organization report: current crisis of antibiotic resistance. BioNanoScience 2019, 9, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W. H. , Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report: 2021. 2021.

- Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Schiffer, C. A. , Introduction: drug resistance. Chemical reviews 2021, 121, 3235–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. J.; Ikuta, K. S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G. R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E. , Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R. E.; Hatfield, K. M.; Wolford, H.; Samore, M. H.; Scott, R. D.; Reddy, S. C.; Olubajo, B.; Paul, P.; Jernigan, J. A.; Baggs, J. National estimates of healthcare costs associated with multidrug-resistant bacterial infections among hospitalized patients in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 72, (Supplement_1), S17-S26.

- Blair, J. M.; Webber, M. A.; Baylay, A. J.; Ogbolu, D. O.; Piddock, L. J. , Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nature reviews microbiology 2015, 13, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Chmiel, R.; Marek, A.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wieczorek, K.; Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Osek, J. , Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—A review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Bakhshi, B.; Najar-Peerayeh, S. , Significant contribution of the CmeABC Efflux pump in high-level resistance to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli clinical isolates. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials 2021, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, L. A.; Dermody, T. S. , Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Archives of internal medicine 1991, 151, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. , Understanding bacterial biofilms: From definition to treatment strategies. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Moser, C.; Wang, H.-Z.; Høiby, N.; Song, Z.-J. , Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. International journal of oral science 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M. H.; Idris, A. L.; Fan, X.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Jin, X.; Qiu, J.; Guan, X.; Huang, T. , Beyond risk: bacterial biofilms and their regulating approaches. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestby, L. K.; Grønseth, T.; Simm, R.; Nesse, L. L. , Bacterial biofilm and its role in the pathogenesis of disease. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wuertz, S. , Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019, 17, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S. K.; Chowdhury, I.; Singh, R. , Understanding the mechanism of bacterial biofilms resistance to antimicrobial agents. The open microbiology journal 2017, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, D.; Leung, V.; Lévesque, C. M. , Bacterial biofilm: structure, function, and antimicrobial resistance. Endodontic Topics 2010, 22, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G. M. , The role of bacterial biofilm in antibiotic resistance and food contamination. International journal of microbiology 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraud, N.; J Kelso, M.; A Rice, S.; Kjelleberg, S. , Nitric oxide: a key mediator of biofilm dispersal with applications in infectious diseases. Current pharmaceutical design 2015, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, R. P.; Carcedo-Forés, M.; Camacho-Bolós, P.; García-Aljaro, C.; Angulo-Preckler, C.; Avila, C.; Lluch, J. R.; Garreta, A. G. , Experimental evidence of antimicrobial activity in Antarctic seaweeds: ecological role and antibiotic potential. Polar Biology 2022, 45, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrela, A. B.; Abraham, W.-R. , Fungal metabolites for the control of biofilm infections. Agriculture 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.-S.; Deyrup, S. T.; Shim, S. H. , Endophyte-produced antimicrobials: a review of potential lead compounds with a focus on quorum-sensing disruptors. Phytochemistry Reviews 2021, 20, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyohannes, G.; Nyerere, A.; Bii, C.; Sbhatu, D. B. Challenges of intervention, treatment, and antibiotic resistance of biofilm-forming microorganisms. Heliyon 2019, 5, (8).

- Hall, C. W.; Mah, T.-F. , Molecular mechanisms of biofilm-based antibiotic resistance and tolerance in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS microbiology reviews 2017, 41, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, E. K.; Call, D. R.; Beyenal, H. , Differential protection from tobramycin by extracellular polymeric substances from Acinetobacter baumannii and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2014, 58, 4755–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Ray, P.; Das, A.; Sharma, M. , Penetration of antibiotics through Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2010, 65, 1955–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackman, G.; Cos, P.; Maes, L.; Nelis, H. J.; Coenye, T. , Quorum sensing inhibitors increase the susceptibility of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2011, 55, 2655–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirioni, O.; Mocchegiani, F.; Cacciatore, I.; Vecchiet, J.; Silvestri, C.; Baldassarre, L.; Ucciferri, C.; Orsetti, E.; Castelli, P.; Provinciali, M. , Quorum sensing inhibitor FS3-coated vascular graft enhances daptomycin efficacy in a rat model of staphylococcal infection. Peptides 2013, 40, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayton, Q. E.; Nguyen, H. K.; Broberg, C. A.; Ocampo, J.; Nagy, S. G.; Schoenfisch, M. H. , Biofilm Dispersal, Reduced Viscoelasticity, and Antibiotic Sensitization via Nitric Oxide-Releasing Biopolymers. ACS Infectious Diseases 2023, 9, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraud, N.; Hassett, D. J.; Hwang, S.-H.; Rice, S. A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Webb, J. S. , Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of bacteriology 2006, 188, 7344–7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G. M.; Newman, D. J.; Snader, K. M. , Natural products in drug discovery and development. Journal of natural products 1997, 60, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A. G.; Zotchev, S. B.; Dirsch, V. M.; Supuran, C. T. , Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, C. A.; Marcovici, I.; Soica, C.; Mioc, M.; Coricovac, D.; Iurciuc, S.; Cretu, O. M.; Pinzaru, I. , Plant-derived anticancer compounds as new perspectives in drug discovery and alternative therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeek, A.; Abdallah, E. M. Phytochemical compounds as antibacterial agents a mini review. Saudi Arabia Glob J Pharmaceu Sci 2019, 53, (4).

- Barbieri, R.; Coppo, E.; Marchese, A.; Daglia, M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Nabavi, S. F.; Nabavi, S. M. , Phytochemicals for human disease: An update on plant-derived compounds antibacterial activity. Microbiological research 2017, 196, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; J Saavedra, M.; Simoes, M. , Insights on antimicrobial resistance, biofilms and the use of phytochemicals as new antimicrobial agents. Current medicinal chemistry 2015, 22, 2590–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Ge, X.; Xua, H.; Ma, K.; Zhang, W.; Zan, Y.; Efferth, T.; Xue, Z.; Hua, X. , Phytochemicals with activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytomedicine 2022, 100, 154073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artini, M.; Papa, R.; Barbato, G.; Scoarughi, G.; Cellini, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Bombardelli, E.; Selan, L. Bacterial biofilm formation inhibitory activity revealed for plant derived natural compounds. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 2012, 20, 920-926.

- Doshi, G.; Aggarwal, G.; Martis, E.; Shanbhag, P. , Novel antibiotics from marine sources. International journal of Pharmaceutical sciences and Nanotechnology 2011, 4, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Nong, X.-H.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Xu, X.-Y.; Amin, M.; Qi, S.-H. , Screening of anti-biofilm compounds from marine-derived fungi and the effects of secalonic acid D on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. 2017.

- Yu, X.; Li, L.; Sun, S.; Chang, A.; Dai, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H. , A cyclic dipeptide from marine fungus Penicillium chrysogenum DXY-1 exhibits anti-quorum sensing activity. ACS omega 2021, 6, 7693–7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, P.; Devadatha, B.; Sarma, V. V.; Ranganathan, S.; Ampasala, D. R.; Siddhardha, B. , Anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm activities of Blastobotrys parvus PPR3 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbial Pathogenesis 2020, 138, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladkova, T. G.; Martinov, B. L.; Gospodinova, D. N. , Anti-biofilm agents from marine biota. Journal of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy 2023, 58, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, S.; Trif, M.; Rusu, A.; Šimat, V.; Čagalj, M.; Alak, G.; Meral, R.; Özogul, Y.; Polat, A.; Özogul, F. , Recent advances in industrial applications of seaweeds. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2023, 63, 4979–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, G. P.; Tavares, W. R.; Sousa, P. M.; Pagès, A. K.; Seca, A. M.; Pinto, D. C. , Seaweed secondary metabolites with beneficial health effects: An overview of successes in in vivo studies and clinical trials. Marine drugs 2019, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuya, P.; Aruna, P.; Sridhar, S.; Kumar, J. S.; Babu, S. Antibacterial activity and qualitative phytochemical analysis of selected seaweeds from Gulf of Mannar region. Journal of Experimental Sciences 2010, 1, (8).

- Lu, W.-J.; Lin, H.-J.; Hsu, P.-H.; Lai, M.; Chiu, J.-Y.; Lin, H.-T. V. Brown and red seaweeds serve as potential efflux pump inhibitors for drug-resistant Escherichia coli. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2019, 2019.

- Rima, M.; Trognon, J.; Latapie, L.; Chbani, A.; Roques, C.; El Garah, F. , Seaweed extracts: A promising source of antibiofilm agents with distinct mechanisms of action against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, C. A.; Minkah, P. A. B.; Agana, T. A.; Moyo, P.; Tetteh, M.; Junior, I. O. D.; Amankwah, K. B.; Somuah, S. O.; Ofori, M.; Maharaj, V. J. , Natural Products as Antibiofilm Agents. 2022.

- Jun, J.-Y.; Jung, M.-J.; Jeong, I.-H.; Yamazaki, K.; Kawai, Y.; Kim, B.-M. , Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of sulfated polysaccharides from marine algae against dental plaque bacteria. Marine drugs 2018, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, W.; Chu, W. , Antimicrobial and anti-quorum sensing activities of phlorotannins from seaweed (Hizikia fusiforme). Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10, 586750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaa, F.; Wijesinghe, P.; Thiripuranathar, G.; Uzair, B.; Iqbal, H.; Khan, B. A.; Menaa, B. , Ecological and industrial implications of dynamic seaweed-associated microbiota interactions. Marine drugs 2020, 18, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picon, A.; Del Olmo, A.; Nuñez, M. , Bacterial diversity in six species of fresh edible seaweeds submitted to high pressure processing and long-term refrigerated storage. Food Microbiology 2021, 94, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genilloud, O.; Pelaez, F.; Gonzalez, I.; Diez, M. Diversity of actinomycetes and fungi on seaweeds from the Iberian coasts. Microbiologia (Madrid, Spain) 1994, 10, 413-422.

- Francis, M.; Webb, V.; Zuccarello, G. , Marine yeast biodiversity on seaweeds in New Zealand waters. New Zealand Journal of Botany 2016, 54, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asharaf, S.; Chakraborty, K.; Chakraborty, R. D. , Seaweed-associated heterotrophic bacteria: are they future novel sources of antimicrobial agents against drug-resistant pathogens? Archives of Microbiology 2022, 204, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potin, P. , Intimate associations between epiphytes, endophytes, and parasites of seaweeds. In Seaweed biology: novel insights into ecophysiology, ecology and utilization, Springer: 2012; pp 203-234.

- Kumar, J.; Singh, D.; Ghosh, P.; Kumar, A. Endophytic and epiphytic modes of microbial interactions and benefits. Plant-Microbe Interactions in Agro-Ecological Perspectives: Volume 1: Fundamental Mechanisms, Methods and Functions 2017, 227-253.

- Silver, W. L.; Brown, S.; Lugo, A. E. In Biodiversity and biogeochemical cycles, Biodiversity and ecosystem processes in tropical forests, 1996; Springer: pp 49-67.

- Chen, J.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Qu, T.; Sun, T.; Liang, S.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X. , Composition and functional diversity of epiphytic bacterial and fungal communities on marine macrophytes in an intertidal zone. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 839465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Saini, K. C.; Mallick, A.; Bast, F. , Seaweed-associated epiphytic bacteria: diversity, ecological and economic implications. Aquatic Botany 2023, 103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuexin, M.; Tian, S.; Haiyan, W.; Yan, W.; Ying, Z. , Antimicrobial activity in the epiphytic fungi on sea weed species in intertidal zone of Dalian. Journal of Dalian Fisheries College 2004, 19, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, M. L.; Toranzo, A. E.; Barja, J. L. , Antibiotic activity of epiphytic bacteria isolated from intertidal seaweeds. Microbial Ecology 1985, 11, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwy, F. M.; Arifah, F. N. , The potentiality of endophytes bacterial in red algae as anti-microbial agents in aquaculture: A review. 2021.

- Mishra, S.; Sharma, S. , Metabolomic insights into endophyte-derived bioactive compounds. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 835931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrani, A.; Ahmad, A.; Djide, M. N.; Natsir, H. Toxicological evaluation and antibacterial activity of crude protein extract from endophytic bacteria associated with Algae Eucheuma spinosum. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1341, 032006.

- Kandou, F. E. F.; Mangindaan, R. E. P.; Rompas, R. M.; Simbala, H. I. Molecular identification and antibacterial activity of marine-endophytic fungi isolated from sea fan Annella sp. from Bunaken waters, Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation 2021, 14, 317-327.

- Felício, R. d.; Pavão, G. B.; Oliveira, A. L. L. d.; Erbert, C.; Conti, R.; Pupo, M. T.; Furtado, N. A.; Ferreira, E. G.; Costa-Lotufo, L. V.; Young, M. C. M. , Antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activities exhibited by endophytic fungi from the Brazilian marine red alga Bostrychia tenella (Ceramiales). Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2015, 25, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, D.; Ananda, N.; Artasasta, M. A.; Ruslan, R.; Fadriyanti, O.; Tallei, T. E. , Antimicrobial activity screening of endophytic fungi extracts isolated from brown algae Padina sp. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2019, 9, 009-013. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2019, 9, 009–013. [Google Scholar]

- Flewelling, A. J.; Johnson, J. A.; Gray, C. A. , Isolation and bioassay screening of fungal endophytes from North Atlantic marine macroalgae. Botanica Marina 2013, 56, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, R.; Chandrika, M.; Rao, H. Y.; Kamalraj, S.; Jayabaskaran, C.; Pugazhendhi, A. , Molecular profiling of marine endophytic fungi from green algae: Assessment of antibacterial and anticancer activities. Process Biochemistry 2020, 96, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrado, R.; Gomes, T. C.; Roque, G. S. C.; De Souza, A. O. , Overview of bioactive fungal secondary metabolites: Cytotoxic and antimicrobial compounds. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, A. B.; Singh, B. P.; Paul, A. T. , Plant-associated endophytic fungi and its secondary metabolites against drug-resistant pathogenic microbes. In Antimicrobial Resistance, Springer: 2022; pp 253-288.

- Jha, P.; Kaur, T.; Panja, A.; Paul, S.; Kumar, V.; Malik, T. , Endophytic fungi: Hidden treasure chest of antimicrobial metabolites interrelationship of endophytes and metabolites. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1227830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rajhi, A. M.; Mashraqi, A.; Al Abboud, M. A.; Shater, A.-R. M.; Al Jaouni, S. K.; Selim, S.; Abdelghany, T. M. , Screening of bioactive compounds from endophytic marine-derived fungi in Saudi Arabia: Antimicrobial and anticancer potential. Life 2022, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Bondkly, E. A. M.; El-Bondkly, A. A. M.; El-Bondkly, A. A. M. Marine endophytic fungal metabolites: A whole new world of pharmaceutical therapy exploration. Heliyon 2021, 7, (3).

- Elsebai, M. F.; Kehraus, S.; Lindequist, U.; Sasse, F.; Shaaban, S.; Gütschow, M.; Josten, M.; Sahl, H.-G.; König, G. M. Antimicrobial phenalenone derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Coniothyrium cereale. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2011, 9, 802-808.

- Suzuki, T.; Ariefta, N. R.; Koseki, T.; Furuno, H.; Kwon, E.; Momma, H.; Harneti, D.; Maharani, R.; Supratman, U.; Kimura, K.-i. New polyketides, paralactonic acids A–E produced by Paraconiothyrium sp. SW-B-1, an endophytic fungus associated with a seaweed, Chondrus ocellatus Holmes. Fitoterapia 2019, 132, 75-81.

- Osterhage, C.; Kaminsky, R.; König, G. M.; Wright, A. D. , Ascosalipyrrolidinone a, an antimicrobial alkaloid, from the obligate marine fungus Ascochyta s alicorniae. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2000, 65, 6412–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-H.; Miao, F.-P.; Li, X.-D.; Yin, X.-L.; Ji, N.-Y. , A new sesquiterpene from an endophytic Aspergillus versicolor strain. Natural Product Communications 2012, 7, 1934578X1200700702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-y.; Li, C.-y.; Lin, Y.-c.; Peng, G.-t.; She, Z.-g.; Zhou, S.-n. Lactones from a brown alga endophytic fungus (No. ZZF36) from the South China Sea and their antimicrobial activities. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2006, 16, 4205-4208.

- Youssef, F. S.; Ashour, M. L.; Singab, A. N. B.; Wink, M. , A comprehensive review of bioactive peptides from marine fungi and their biological significance. Marine drugs 2019, 17, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopel, M.; Abraham, W.-R.; Henriques, A. T.; Macedo, A. J. Dipeptide cis-cyclo (Leucyl-Tyrosyl) produced by sponge associated Penicillium sp. F37 inhibits biofilm formation of the pathogenic Staphylococcus epidermidis. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2013, 23, 624-626.

- Santos, G. S. d. Phaeurus antarcticus and its endophytic fungi: chemical diversity of a hidden pharmacy underneath the Antarctic Ocean. Universidade de São Paulo, 2022.

- Jaber, S. A. M. F.; Young, L.; Black, K.; Tate, R.; Edrada-Ebel, R. In Implementing Metabolomics Tools to Optimise the Production of Anti-Biofilm Metabolites of Endophytic Fungi from Scottish Seaweed, 10th European Marine Natural Products Conference, 2019.

- Machado, F. P.; Kumla, D.; Pereira, J. A.; Sousa, E.; Dethoup, T.; Freitas-Silva, J.; Costa, P. M.; Mistry, S.; Silva, A. M.; Kijjoa, A. , Prenylated phenylbutyrolactones from cultures of a marine sponge-associated fungus Aspergillus flavipes KUFA1152. Phytochemistry 2021, 185, 112709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá, J. D.; Pereira, J. A.; Dethoup, T.; Cidade, H.; Sousa, M. E.; Rodrigues, I. C.; Costa, P. M.; Mistry, S.; Silva, A. M.; Kijjoa, A. , Anthraquinones, diphenyl ethers, and their derivatives from the culture of the marine sponge-associated fungus Neosartorya spinosa KUFA 1047. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomchit, A.; Calderin, J. D.; Jaidee, W.; Watla-Iad, K.; Brooks, S. Napthoquinones from Neocosmospora sp.—Antibiotic activity against acidovorax citrulli, the causative agent of bacterial fruit blotch in watermelon and melon. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 370.

- Zin, W. W. M.; Buttachon, S.; Dethoup, T.; Pereira, J. A.; Gales, L.; Inácio, Â.; Costa, P. M.; Lee, M.; Sekeroglu, N.; Silva, A. M. , Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of the metabolites isolated from the culture of the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus Eurotium chevalieri KUFA 0006. Phytochemistry 2017, 141, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumla, D.; Pereira, J. A.; Dethoup, T.; Gales, L.; Freitas-Silva, J.; Costa, P. M.; Lee, M.; Silva, A. M.; Sekeroglu, N.; Pinto, M. M. , Chromone derivatives and other constituents from cultures of the marine sponge-associated fungus Penicillium erubescens KUFA0220 and their antibacterial activity. Marine drugs 2018, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qader, M. M.; Hamed, A. A.; Soldatou, S.; Abdelraof, M.; Elawady, M. E.; Hassane, A. S.; Belbahri, L.; Ebel, R.; Rateb, M. E. , Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of the fungal metabolites isolated from the marine endophytes Epicoccum nigrum M13 and Alternaria alternata 13A. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelgawad, M. A.; Hamed, A. A.; Nayl, A. A.; Badawy, M. S. E.; Ghoneim, M. M.; Sayed, A. M.; Hassan, H. M.; Gamaleldin, N. M. , The chemical profiling, docking study, and antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of the endophytic fungi Aspergillus sp. AP5. Molecules 2022, 27, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F. P.; Rodrigues, I. C.; Gales, L.; Pereira, J. A.; Costa, P. M.; Dethoup, T.; Mistry, S.; Silva, A. M.; Vasconcelos, V.; Kijjoa, A. , New Alkylpyridinium Anthraquinone, Isocoumarin, C-Glucosyl Resorcinol Derivative and Prenylated Pyranoxanthones from the Culture of a Marine Sponge-Associated Fungus, Aspergillus stellatus KUFA 2017. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F. P.; Rodrigues, I. C.; Georgopolou, A.; Gales, L.; Pereira, J. A.; Costa, P. M.; Mistry, S.; Hafez Ghoran, S.; Silva, A. M.; Dethoup, T. , New hybrid phenalenone dimer, highly conjugated dihydroxylated C28 steroid and azaphilone from the culture extract of a marine sponge-associated fungus, Talaromyces pinophilus KUFA 1767. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrada-Ebel, R.; Michael, A.; Alsaleh, F.; Zaharuddin, H. , Penicillium, and Fusarium for the Antibiotic Pipeline. In Fungi Bioactive Metabolites: Integration of Pharmaceutical Applications, Deshmukh, S. K.; Takahashi, J. A., Ed.; Saxena, S., Eds. Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, S. H.; El-Maraghy, S. S.; Abdel-Mallek, A. Y.; Abdel-Rahman, M. A.; Hassanein, E. H.; Al-Bedak, O. A.; El-Aziz, F. E.-Z. A. A. , The antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and wound healing properties of ethyl acetate crude extract of an endophytic fungus Paecilomyces sp.(AUMC 15510) in earthworm model. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 19239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengzhuang, W.; Wu, H.; Ciofu, O.; Song, Z.; Høiby, N. , Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of colistin and imipenem on mucoid and nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2011, 55, 4469–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owlia, P.; Nosrati, R.; Alaghehbandan, R.; Lari, A. R. Antimicrobial susceptibility differences among mucoid and non-mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. GMS hygiene and infection control 2014, 9, (2).

- Kapoor, P.; Murphy, P. Combination antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, representing common and rare cystic fibrosis strains from different Irish clinics. Heliyon 2018, 4, (3).

- Attia, E. Z.; Khalifa, B. A.; Shaban, G. M.; Abdelraheem, W. M.; Mustafa, M.; Abdelmohsen, U. R.; Mo'men, H. , Discovering the chemical profile, antimicrobial and antibiofilm potentials of the endophytic fungus Penicillium chrysogenum isolated from Artemisia judaica L. assisted with docking studies. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 151, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong Chin, J. M.; Puchooa, D.; Bahorun, T.; Jeewon, R. , Antimicrobial properties of marine fungi from sponges and brown algae of Mauritius. Mycology 2021, 12, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, K. R.; Heidelbach, S.; Zeuner, E. J.; Riisgaard-Jensen, M.; Nielsen, M. E.; Vestergaard, S. Z.; Bekker, N. S.; Skovmark, J.; Olesen, C. K.; Thomsen, K. H. , The effects of different potato dextrose agar media on secondary metabolite production in Fusarium. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2021, 347, 109171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charria-Girón, E.; Espinosa, M. C.; Zapata-Montoya, A.; Méndez, M. J.; Caicedo, J. P.; Dávalos, A. F.; Ferro, B. E.; Vasco-Palacios, A. M.; Caicedo, N. H. , Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of crude extracts obtained from cultivation of native endophytic fungi belonging to a tropical montane rainforest in Colombia. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, S. A. M. F. Metabolomic profiling of antibiofilm compounds from fungal endophytes derived from Scottish seaweeds. http://purl.org/coar/resource_type/c_db06, University of Strathclyde, 2021.

- Doreswamy, K.; Shenoy, P.; Bhaskar, S.; Kini, R. K.; Sekhar, S. Woodfordia fruticosa (Linn.) Kurz’s fungal endophyte Mucor souzae’s secondary metabolites, kaempferol and quercetin, bestow biological activities. Journal of Applied Biology and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 44-53.

- Bajpai, R.; Yusuf, M. A.; Upreti, D. K.; Gupta, V. K.; Singh, B. N. , Endolichenic fungus, Aspergillus quandricinctus of Usnea longissima inhibits quorum sensing and biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbial pathogenesis 2020, 140, 103933. [Google Scholar]

- İrez, E. İ.; Doğru, N. H.; Demir, N. Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr. extracts as sources of an antioxidant, antimicrobial and antibiofilm agents. Biologica Nyssana 2021, 12, (1).

- Kaur, N.; Arora, D. S. , Prospecting the antimicrobial and antibiofilm potential of Chaetomium globosum an endophytic fungus from Moringa oleifera. AMB Express 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Arora, D. S.; Kalia, N.; Kaur, M. , Antibiofilm, antiproliferative, antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of an endophytic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus from Moringa oleifera. Molecular biology reports 2020, 47, 2901–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, D. J.; Palombo, E. A.; Moulton, S. E.; Duggan, P. J.; Zaferanloo, B. , Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Endophytic Alternaria sp. Isolated from Eremophila longifolia. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, M.; Meena, H.; Meena, C.; Kushveer, J.; Busi, S.; Murali, A.; Sarma, V. , Anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm potential of Alternaria alternata, a foliar endophyte of Carica papaya, evidenced by QS assays and in-silico analysis. Fungal biology 2018, 122, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, D. M.; Atalla, S. M.; Hamed, A. A.; El-Khrisy, E.-D. A. Investigation of secondary metabolites and its bioactivity from Sarocladium kiliense SDA20 using shrimp shell wastes. Pharmacognosy Journal 2020, 12, (3).

- Njateng, G. S. S.; Du, Z.; Gatsing, D.; Mouokeu, R. S.; Liu, Y.; Zang, H.-X.; Gu, J.; Luo, X.; Kuiate, J.-R. , Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of crude extract, fractions and compounds from the stem bark of Polyscias fulva Hiern (Araliaceae). BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulis, A. G.; Hamed, A. A.; El-Awady, M. E.; Mohamed, A. R.; Eliwa, E. M.; Asker, M. M.; Shaaban, M. Diverse bioactive metabolites from Penicillium sp. MMA derived from the red sea: structure identification and biological activity studies. Archives of Microbiology 2020, 202, 1985-1996.

- Chikowe, G. R.; Mpala, L. N.; Cock, I. E. Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steud. Leaf Extracts Lack Anti-bacterial Activity and are Non-toxic in vitro. Pharmacognosy Communications 2023, 13, (4).

- Durães, F.; Szemerédi, N.; Kumla, D.; Pinto, M.; Kijjoa, A.; Spengler, G.; Sousa, E. , Metabolites from marine-derived fungi as potential antimicrobial adjuvants. Marine drugs 2021, 19, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscetto, E.; Masi, M.; Esposito, M.; Di Lecce, R.; Delicato, A.; Maddau, L.; Calabrò, V.; Evidente, A.; Catania, M. R. , Anti-biofilm activity of the fungal phytotoxin sphaeropsidin A against clinical isolates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Toxins 2020, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xin, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, F.; Niu, C.; Liu, S. , Terpenoids from Marine Sources: A Promising Avenue for New Antimicrobial Drugs. Marine Drugs 2024, 22, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, P. H.; Barbosa, D. P.; da Silva, D. L.; Ribeiro, Ê. A.; Santana, A. E.; Santos, B. V.; Barbosa-Filho, J. M.; Quintans, J. S.; Barreto, R. S.; Quintans-Júnior, L. J. , Indole alkaloids from marine sources as potential leads against infectious diseases. BioMed research international 2014, 2014, 375423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethupathy, S.; Sathiyamoorthi, E.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J. , Antibiofilm and antivirulence properties of indoles against Serratia marcescens. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 584812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemkuignou, B. M.; Treiber, L.; Zeng, H.; Schrey, H.; Schobert, R.; Stadler, M. Macrooxazoles a–d, new 2, 5-disubstituted oxazole-4-carboxylic acid derivatives from the plant pathogenic fungus Phoma macrostoma. Molecules 2020, 25, (23).

- Talle Juidzou, G.; Gisèle Mouafo Anoumedem, E.; Kehdinga Sema, D.; Flaure Tsague Tankeu, V.; Bosco Leutcha, P.; Yetendje Chimi, L.; Paul Dzoyem, J.; Kouam Fogue, S.; Sewald, N.; Choudhary, M. I. , A New Unsaturated Aliphatic Anhydride from Aspergillus candidus T 12 19W1, an Endophytic Fungus, from Pittosporum mannii Hook f. Journal of Chemistry 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C. G.; Mongolla, P.; Pombala, S.; Bandi, S.; Babu, K.; Ramakrishna, K. , Biological evaluation of 3-hydroxybenzyl alcohol, an extrolite produced by Aspergillus nidulans strain KZR-132. Journal of applied microbiology 2017, 122, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Kushveer, J. S.; Khan, M. I. K.; Pagal, S.; Meena, C. K.; Murali, A.; Dhayalan, A.; Venkateswara Sarma, V. , 2, 4-Di-tert-butylphenol isolated from an endophytic fungus, Daldinia eschscholtzii, reduces virulence and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuyama, K. T.; Wendt, L.; Surup, F.; Kretz, R.; Chepkirui, C.; Wittstein, K.; Boonlarppradab, C.; Wongkanoun, S.; Luangsa-Ard, J.; Stadler, M. , Cytochalasans act as inhibitors of biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuyama, K. T.; Chepkirui, C.; Wendt, L.; Fortkamp, D.; Stadler, M.; Abraham, W.-R. , Bioactive compounds produced by Hypoxylon fragiforme against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuyama, K. T.; Rohde, M.; Molinari, G.; Stadler, M.; Abraham, W.-R. , Unsaturated fatty acids control biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus and other gram-positive bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zawawy, N. A.; Ali, S. S.; Nouh, H. S. , Exploring the potential of Rhizopus oryzae AUMC14899 as a novel endophytic fungus for the production of l-tyrosine and its biomedical applications. Microbial Cell Factories 2023, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, A.; Örtücü, S.; Taşkin, M. , Screening and characterization of a novel Antibiofilm polypeptide derived from filamentous Fungi. Journal Of Proteomics 2021, 233, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E. G.; Ramakrishna, S.; Vikineswary, S.; Das, D.; Bahkali, A. H.; Guo, S.-Y.; Pang, K.-L. , How do fungi survive in the sea and respond to climate change? Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, T. R.; Santos, G. S. d.; Armstrong, L.; Colepicolo, P.; Debonsi, H. M. , Antitumor potential of seaweed derived-endophytic fungi. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helaly, S. E.; Kuephadungphan, W.; Phainuphong, P.; Ibrahim, M. A.; Tasanathai, K.; Mongkolsamrit, S.; Luangsa-Ard, J. J.; Phongpaichit, S.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Stadler, M. , Pigmentosins from Gibellula sp. as antibiofilm agents and a new glycosylated asperfuran from Cordyceps javanica. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2019, 15, 2968–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, O. P.; García-Contreras, R.; Aguayo-Ortiz, R.; Figueroa, M. , Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of fungal metabolites on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 43300) mediated by SarA and AgrA. Biofouling 2023, 39, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuephadungphan, W.; Macabeo, A. P. G.; Luangsa-Ard, J. J.; Tasanathai, K.; Thanakitpipattana, D.; Phongpaichit, S.; Yuyama, K.; Stadler, M. , Studies on the biologically active secondary metabolites of the new spider parasitic fungus Gibellula gamsii. Mycological Progress 2019, 18, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshe, R.; Charria-Girón, E.; Khonsanit, A.; Luangsa-Ard, J. J.; Khalid, S. J.; Schrey, H.; Ebada, S. S.; Stadler, M. , Bioprospection of Tenellins Produced by the Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria neobassiana. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, A.; Nocera, F. P.; Tafuri, S.; Ciani, F.; Staropoli, A.; Comite, E.; Bottiglieri, A.; Gioia, L.; Lorito, M.; Woo, S. L. , Antimicrobial activity of harzianic acid against Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Natural Product Research 2021, 35, 5440–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, D.; Bhatt, A.; Gupte, A. , Evaluation of Bioactive Attributes and Emulsification Potential of Exopolysaccharide Produced by a Brown-rot Fungus Fomitopsis meliae AGDP-2. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2023, 195, 2974–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, V.; Ghosh, N. N.; Mitra, P. K.; Mandal, S.; Mandal, V. , Production and characterization of a broad-spectrum antimicrobial 5-butyl-2-pyridine carboxylic acid from Aspergillus fumigatus nHF-01. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachma, L. N.; Fitri, L. E.; Prawiro, S. R.; Mardining Raras, T. Y. , Aspergillus oryzae attenuates quorum sensing-associated virulence factors and biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. F1000Research 2022, 11, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmani, A.; Teponno, R. B.; Helaly, S. E.; Arzanlou, M.; Stadler, M. , Cytotoxic, anti-biofilm and antimicrobial polyketides from the plant associated fungus Chaetosphaeronema achilleae. Fitoterapia 2019, 139, 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehia, R. S. , Multi-function of a new bioactive secondary metabolite derived from endophytic fungus Colletotrichum acutatum of Angelica sinensis. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2023, 33, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Sharma, P.; Kaur, R.; Kaur, S.; Kaur, A. , Assessment of alpha glucosidase inhibitors produced from endophytic fungus Alternaria destruens as antimicrobial and antibiofilm agents. Molecular Biology Reports 2020, 47, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Razek, M. M.; Moussa, A. Y.; El-Shanawany, M. A.; Singab, A. N. B. A New Phenolic Alkaloid from Halocnemum strobilaceum endophytes: antimicrobial, antioxidant and biofilm Inhibitory activities. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2020, 17, e2000496.

- Fathallah, N.; Raafat, M. M.; Issa, M. Y.; Abdel-Aziz, M. M.; Bishr, M.; Abdelkawy, M. A.; Salama, O. Bio-guided fractionation of prenylated benzaldehyde derivatives as potent antimicrobial and antibiofilm from Ammi majus L. fruits-associated Aspergillus amstelodami. Molecules 2019, 24, 4118.

- Elkhouly, H. I.; Sidkey, N. M.; Ghareeb, M. A.; El Hosainy, A. M.; Hamed, A. A. , Bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic Aspergillus terreus AH1 isolated from Ipomoea carnea growing in Egypt. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 64, 7611–7620. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-W.; Wu, X.-Y.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Huang, Z.-Q.; Lei, X.-S.; Yang, G.-X.; Li, J.; Xiong, J.; Hu, J.-F. , Terricoxanthones A–E, unprecedented dihydropyran-containing dimeric xanthones from the endophytic fungus Neurospora terricola HDF-Br-2 associated with the vulnerable conifer Pseudotsuga gaussenii. Phytochemistry 2024, 219, 113963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, M. M.; M. Emam, T.; Raafat, M. M., Hindering of cariogenic streptococcus mutans biofilm by fatty acid array derived from an endophytic arthrographis kalrae strain. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, L. J.; Buttachon, S.; Dethoup, T.; Martins, R.; Vasconcelos, V.; Kijjoa, A.; Martins da Costa, P. , Neofiscalin A and fiscalin C are potential novel indole alkaloid alternatives for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-positive bacterial infections. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2016, 363, fnw150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.; Abdel-Razek, A. S.; Araby, M.; Abu-Elghait, M.; El-Hosari, D. G.; Frese, M.; Soliman, H. S.; Stammler, H. G.; Sewald, N.; Shaaban, M. , Meleagrin from marine fungus Emericella dentata Nq45: crystal structure and diverse biological activity studies. Natural product research 2021, 35, 3830–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loges, L. A.; Silva, D. B.; Paulino, G. V.; Landell, M. F.; Macedo, A. J. , Polyketides from marine-derived Aspergillus welwitschiae inhibit Staphylococcus aureus virulence factors and potentiate vancomycin antibacterial activity in vivo. Microbial pathogenesis 2020, 143, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R. M. K.; Pannippara, M. A.; Kesav, S.; Mathew, A.; Bhat, S. G.; Aa, M. H.; Elyas, K. , MFAP9: Characterization of an extracellular thermostable antibacterial peptide from marine fungus with biofilm eradication potential. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2021, 194, 113808. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Fujioka, T.; Yoshimi, A.; Kumagai, T.; Umemura, M.; Abe, K.; Machida, M.; Kawai, K. , Discovery of a gene cluster for the biosynthesis of novel cyclic peptide compound, KK-1, in Curvularia clavata. Frontiers in Fungal Biology 2023, 3, 1081179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munusamy, M.; Ching, K. C.; Yang, L. K.; Crasta, S.; Gakuubi, M. M.; Chee, Z. Y.; Wibowo, M.; Leong, C. Y.; Kanagasundaram, Y.; Ng, S. B. , Chemical elicitation as an avenue for discovery of bioactive compounds from fungal endophytes. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10, 1024854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gakuubi, M. M.; Ching, K. C.; Munusamy, M.; Wibowo, M.; Liang, Z.-X.; Kanagasundaram, Y.; Ng, S. B. , Enhancing the discovery of bioactive secondary metabolites from fungal endophytes using chemical elicitation and variation of fermentation media. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 898976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderMolen, K. M.; Raja, H. A.; El-Elimat, T.; Oberlies, N. H. , Evaluation of culture media for the production of secondary metabolites in a natural products screening program. Amb Express 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinta, D. Y.; Juliandi, M. D.; Widyastuti, W.; Sonata, H.; Saryono, S. , Microbial inhibition test and optimization of temperature, aeration fermentation of endophytic Fusarium sp LBKURCC 41 from Dahlia tuber (Dahlia variabilis). Bali Medical Journal 2023, 12, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Sun, K.; Zhu, W. , Effects of high salt stress on secondary metabolite production in the marine-derived fungus Spicaria elegans. Marine drugs 2011, 9, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, W.-C.; Shi, X.; Zheng, H.-Z.; Zheng, Z.-H.; Lu, X.-H.; Xing, Y.; Ji, K.; Liu, M.; Dong, Y.-S. , Inducing secondary metabolite production of Aspergillus sydowii through microbial co-culture with Bacillus subtilis. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caudal, F.; Tapissier-Bontemps, N.; Edrada-Ebel, R. A. Impact of Co-Culture on the Metabolism of Marine Microorganisms. Mar Drugs 2022, 20, (2).

- Azzollini, A.; Boggia, L.; Boccard, J.; Sgorbini, B.; Allard, P.-M.; Rubiolo, P.; Rudaz, S.; Wolfender, J.-L. , Dynamics of metabolite induction in fungal co-cultures by metabolomics at both volatile and non-volatile levels. Frontiers in microbiology 2018, 9, 326597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Mochamad Afendi, F.; Altaf-Ul-Amin, M.; Takahashi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Kanaya, S. Metabolomics of medicinal plants: the importance of multivariate analysis of analytical chemistry data. Current Computer-Aided Drug Design 2010, 6, 179-196.

- Lajis, N.; Maulidiani, M.; Abas, F.; Ismail, I. , Metabolomics approach in pharmacognosy. In Pharmacognosy, Elsevier: 2017; pp 597-616.

- Naz, S.; Vallejo, M.; García, A.; Barbas, C. , Method validation strategies involved in non-targeted metabolomics. Journal of Chromatography A 2014, 1353, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, M.; Caterino, M.; Ruoppolo, M. , Targeted metabolomics. In Metabolomics Perspectives, Elsevier: 2022; pp 219-236.

- Nagarajan, K.; Ibrahim, B.; Ahmad Bawadikji, A.; Lim, J.-W.; Tong, W.-Y.; Leong, C.-R.; Khaw, K. Y.; Tan, W.-N. , Recent developments in metabolomics studies of endophytic fungi. Journal of Fungi 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfike, A. F.; Tate, R.; Abbott, G.; Young, L.; Viegelmann, C.; Schumacher, M.; Diederich, M.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Metabolomic Tools to Assess the Chemistry and Bioactivity of Endophytic Aspergillus Strain. Chem Biodivers 2017, 14, (10).

- Tawfike, A. F.; Romli, M.; Clements, C.; Abbott, G.; Young, L.; Schumacher, M.; Diederich, M.; Farag, M.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Isolation of anticancer and anti-trypanosome secondary metabolites from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus flocculus via bioactivity guided isolation and MS based metabolomics. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2019, 1106-1107, 71-83.

- Tawfike, A. F.; Viegelmann, C.; Edrada-Ebel, R. , Metabolomics and dereplication strategies in natural products. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 1055, 227–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mazlan, N. W.; Tate, R.; Yusoff, Y. M.; Clements, C.; Edrada-Ebel, R. , Metabolomics-Guided Isolation of Anti-Trypanosomal Compounds from Endophytic Fungi of the Mangrove plant Avicennia Lanata. Curr Med Chem 2020, 27, 1815–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Nwagwu, E.; Young, L.; Kumar, P.; Shinde, P. B.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Targeted Isolation of Antibiofilm Compounds from Halophytic Endophyte Bacillus velezensis 7NPB-3B Using LC-HR-MS-Based Metabolomics. Microorganisms 2024, 12, (2).

- Alhadrami, H. A.; Sayed, A. M.; El-Gendy, A. O.; Shamikh, Y. I.; Gaber, Y.; Bakeer, W.; Sheirf, N. H.; Attia, E. Z.; Shaban, G. M.; Khalifa, B. A. , A metabolomic approach to target antimalarial metabolites in the Artemisia annua fungal endophytes. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccenti, E.; Hoefsloot, H. C.; Smilde, A. K.; Westerhuis, J. A.; Hendriks, M. M. , Reflections on univariate and multivariate analysis of metabolomics data. Metabolomics 2014, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Thomas, N.; Ramezanpour, M.; Psaltis, A. J.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Thierry, B.; Wormald, P.-J.; Prestidge, C. A.; Vreugde, S. , Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by quatsomes in low concentrations. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2020, 245, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, E.; Nelis, H. J.; Coenye, T. , Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. Journal of microbiological methods 2008, 72, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, K. K.; Menor, S. A.; Pettit, R. K. , Microplate Alamar blue assay for susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Medical mycology 2007, 45, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, V. G.; Săndulescu, O. Communication is the key: biofilms, quorum sensing, formation and prevention. Discoveries 2019, 7, (3).

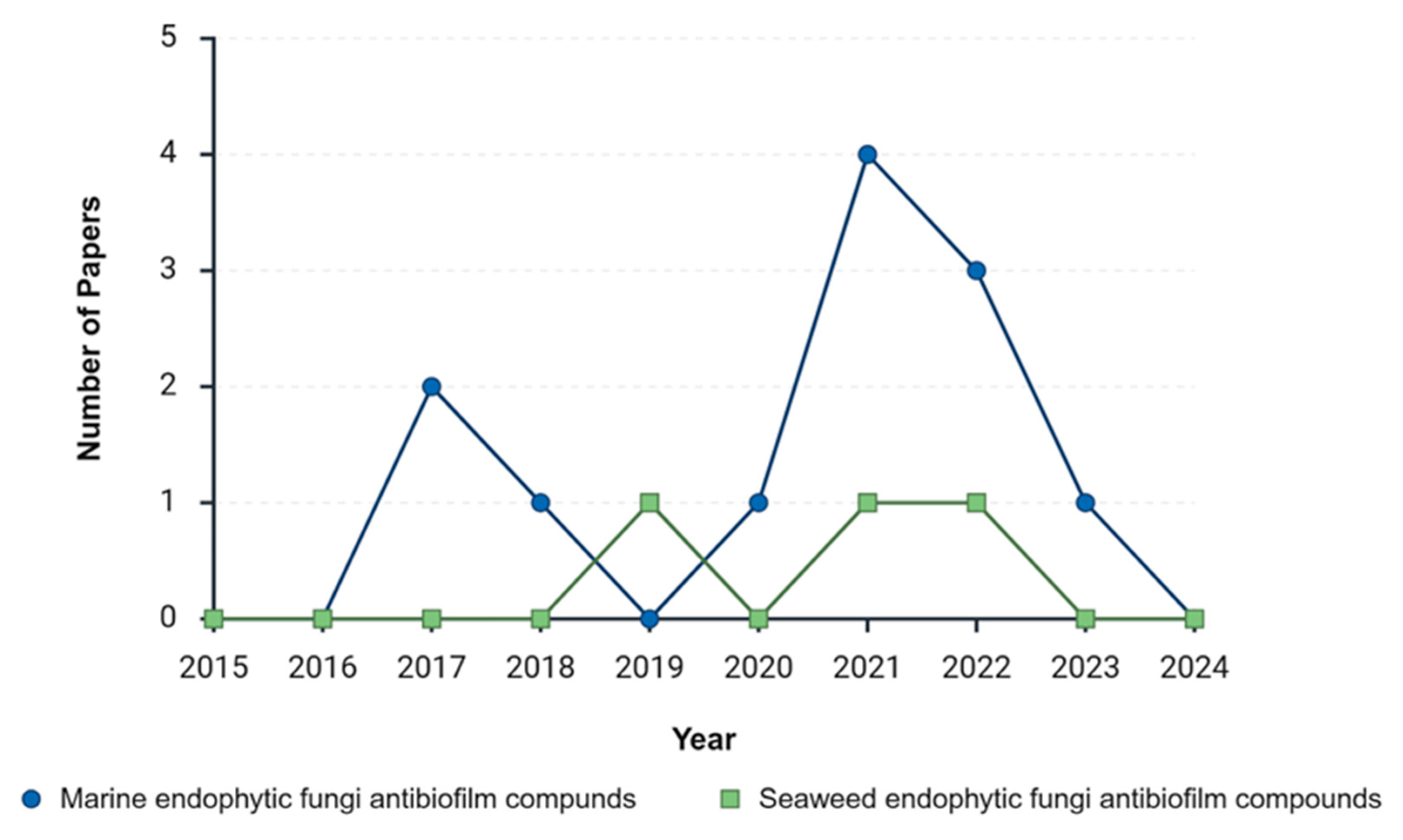

| Year | Marine endophytic fungi antibiofilm compounds | Seaweed endophytic fungi antibiofilm compounds | ||

| Before Exclusion | After Exclusion | Before Exclusion | After Exclusion | |

| 2015 | 46 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 2016 | 53 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 2017 | 83 | 2 | 30 | 0 |

| 2018 | 138 | 1 | 22 | 0 |

| 2019 | 182 | 0 | 56 | 1 |

| 2020 | 249 | 1 | 73 | 0 |

| 2021 | 447 | 4 | 140 | 1 |

| 2022 | 544 | 3 | 181 | 1 |

| 2023 | 846 | 1 | 246 | 0 |

| 2024 | 764 | 0 | 233 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).